![[Image of the book's cover unavailable.]](images/cover.jpg)

Title: Picturesque Spain: Architecture, landscape, life of the people.

Author: Kurt Hielscher

Release date: March 30, 2021 [eBook #64959]

Language: English

|

Alphabetical List of Names and Places Illustrations Some typographical errors have been corrected. (etext transcriber's note) |

PICTURESQUE SPAIN

ARCHITECTURE * LANDSCAPE

LIFE OF THE PEOPLE

BY

KURT HIELSCHER

T. FISHER UNWIN LTD

LONDON : : ADELPHI TERRACE

{iv}

{v}

MOST HUMBLY DEDICATED

TO

HIS MAJESTY KING ALFONSO XIII.

OF

SPAIN

Spain is one great open-air museum containing the cultural wealth of the most varied epochs and peoples. On the walls of the Altamira cave is blazoned that much admired steer painted thousands of years ago by men of the Ice Age. In Barcelona stand the fantastic buildings of neo-Castilian present-day art. Celts, Iberians, Romans, Carthaginians, Moors and Goths have fought and struggled for supremacy in Spain. Of all this the stones tell us to-day. They are the chronicles. They relate of bitter strife; of the culture and art aspirations belonging to times gone by. Much has vanished into dust and ruin. That which has survived time’s fretting tooth serves as a giant bridge to lead us back to the past.

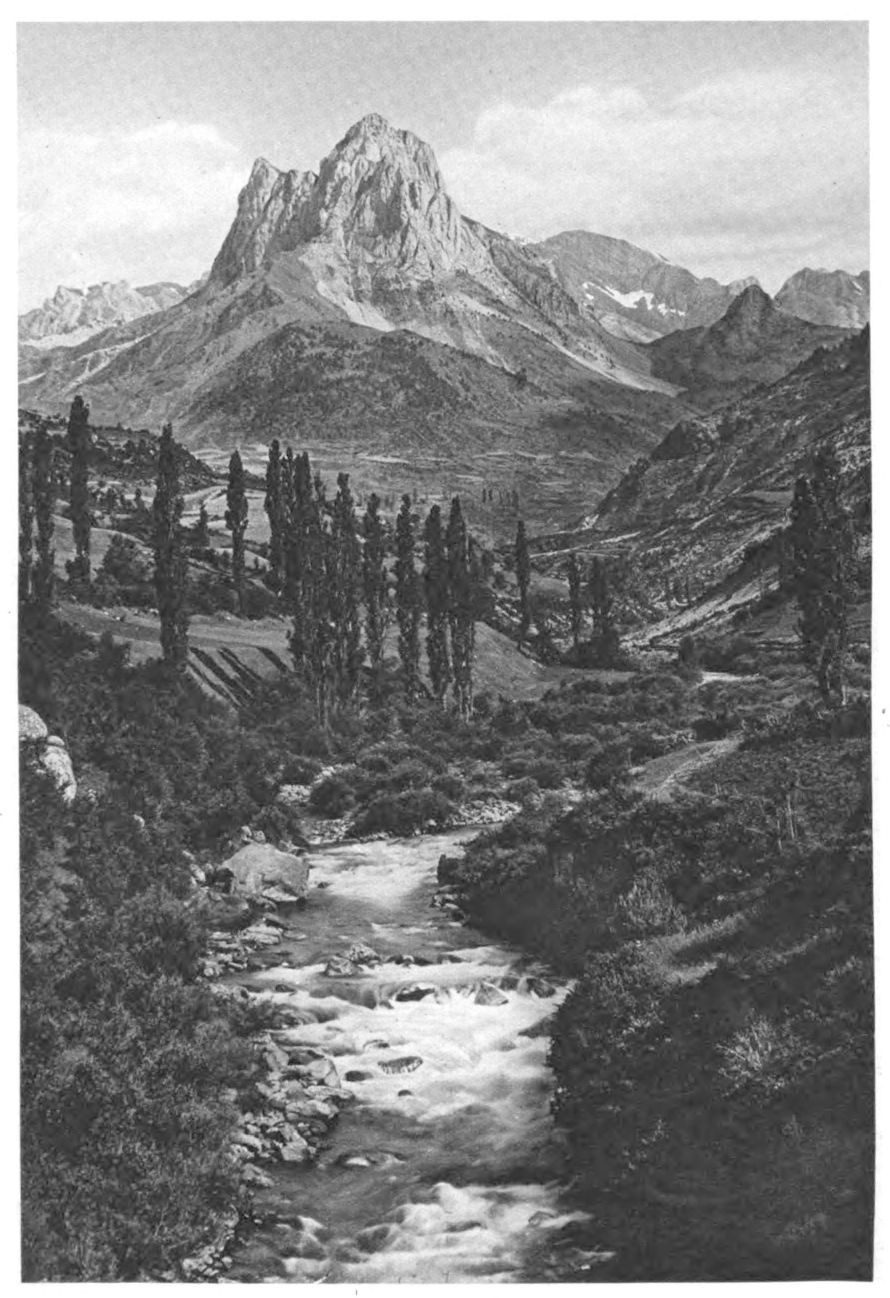

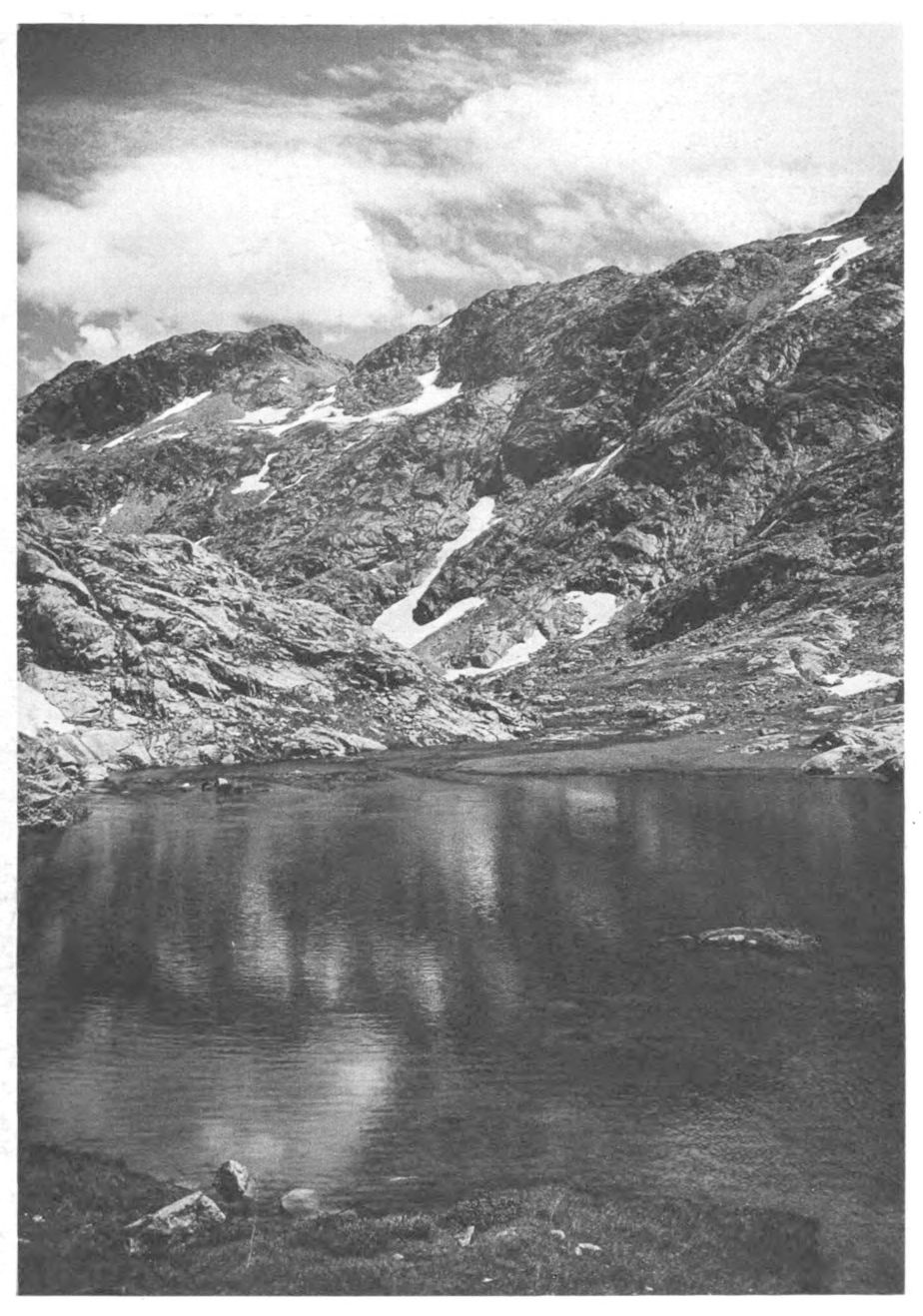

Fate was kind enough to let me spend five years in Spain. Caught there by the war while engaged in studies, I was cut off from home. I made use of my involuntary stay to become acquainted with the country in its furthermost corners. I roved to and fro from the pinnacles of the Pyrenees to the shores of Tarifa, from the palm forest of Elché to the forgotten Hurdes inhabitants of Estremadura.

On all my lonely wanderings I was accompanied by my faithful camera: we covered over 45000 kilometres together in Spain. We kept our eyes open diligently. I say we, for in addition to mine was a precious glass eye in the shape of the Zeiss lens. Whereas my eyes only made me the intellectual recipient of what we saw, that of my travelling companion made it a pictorial permanency. I took over 2000 photographs during our peregrinations. This volume only presents a small selection. It was not easy to make the final choice. Many a picture had to be omitted to which I was attached, either for its peculiarity or its character.

I went at no one’s instigation through Spain but that of my own in search of the beautiful. I was not guided by any constraining professional principles. Beautiful art treasures, geographical peculiarities, enchanting landscapes, interesting customs that attracted my attention were retained by my camera. I followed the same lines in making my selections for publication.

I entitle this volume “Picturesque Spain”. Much will be unknown to many. I begin however with a spot famous throughout the world.—And yet I was bound to. Like the pilgrim who is drawn to the fabled Fontana Trevi once he has drunk of its waters, so too was I drawn again and again to Granada in my wanderings. I believe too that I have succeeded in presenting the Alhambra from one or two different points of view. Who indeed could exhaust this well of beauty?

Nor could I pass heedlessly by Cordoba, Seville and Toledo, for these towns are starting points.—Finger-posts to unknown Spain. Without these monuments of ancient times, those parts of Spain situate far from the high-roads remain an almost insolvable riddle.

My pictures must speak for me. Those who know how to ask them will find that they tell much. For this reason I shall limit myself to but a few initiatory words. They serve to connect the known with the unknown; to throw light on the paths along which I journeyed in Spain.{viii}

⚪

Granada! Thy name is music; a joyous chord of beauty! To pass the spring within thy gateways is to walk the heights of life.

Spring has cast a shower of blossoms over the town and woven a delicate green carpet around the Alhambra. How many many centuries has it not worshipped thus yearly at the feet of the castle? Long ago passionate Moorish women decorated their raven hair there with rosy almond blossoms.—It is long since that the glory of those days has departed. Perhaps this is why the castle walls look down so sadly at the beauty of this blissful vernal soil.

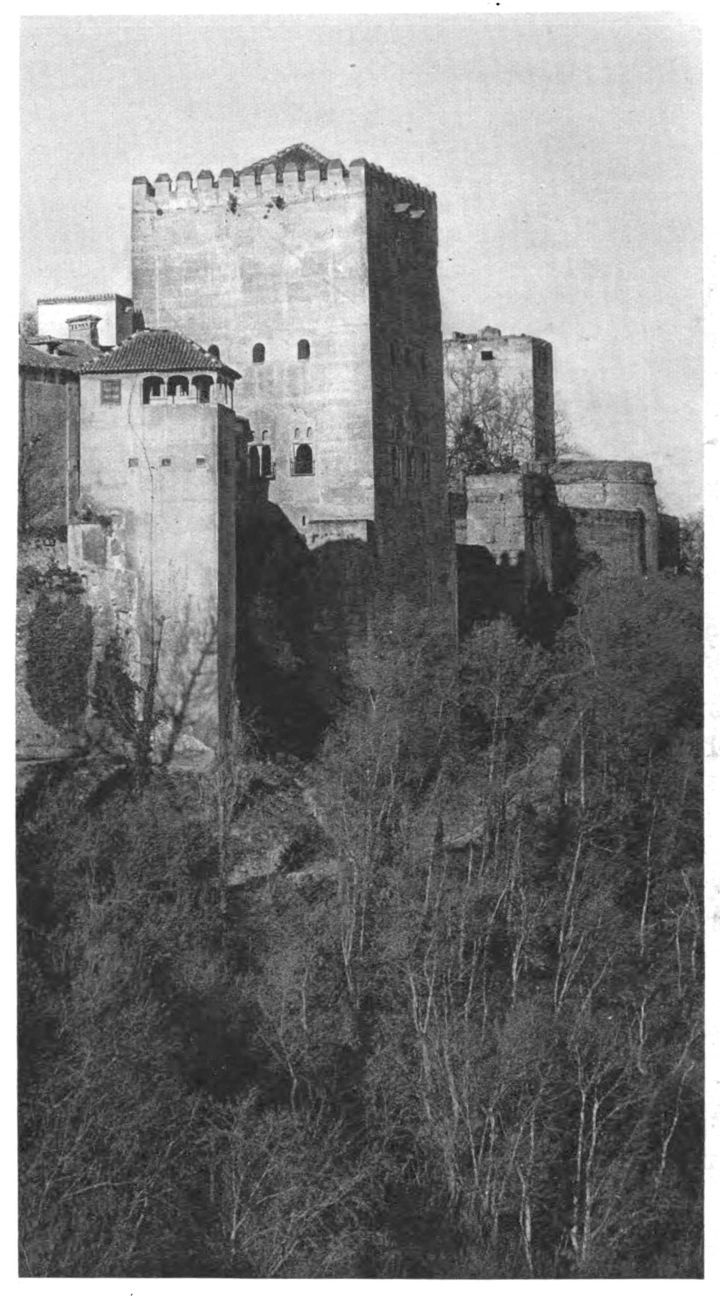

Bidding defiance in the grandeur of their strength the towers of the Alhambra arise. Their fiery red lights skywards like the flames on giant altars.[A]

Is it possible that these massive cyclopean walls should hide a fairy-land?

Impatiently we climb the castle mount. Reaching an old stone gateway ornamented with pomegranates, the noise of the streets is left behind as we enter a yew grove whose ancient giant stems are ivy-grown; blue myrtle covers the ground, the lights gleam golden through the foliage, the wind murmurs among the branches, nightingales sing in the boscage, swallows dart twittering over the tree tops, water hurries babbling down the hilly slope.

All this seems like a miracle in Spain so poor in forests. It is as though another world had opened its gates.

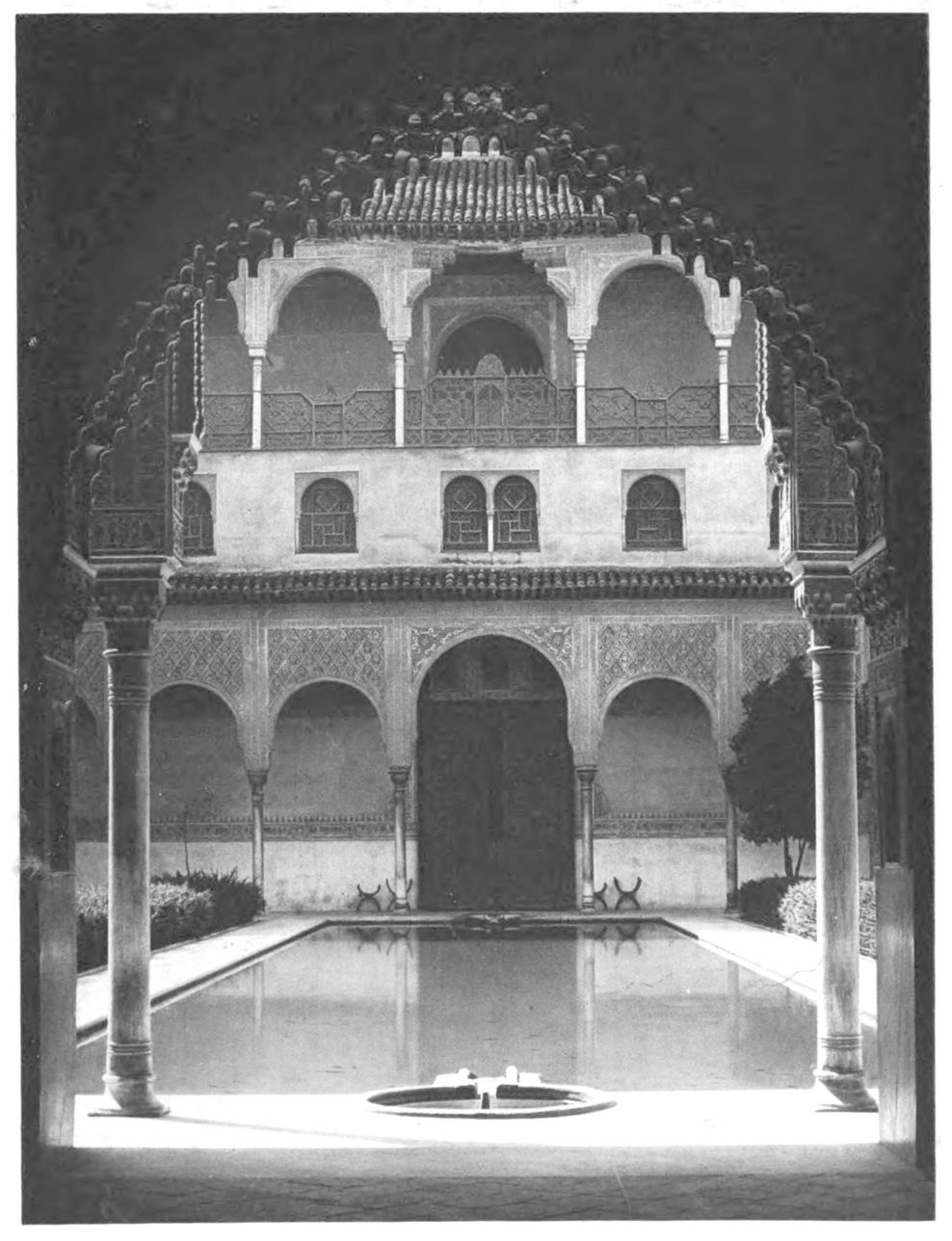

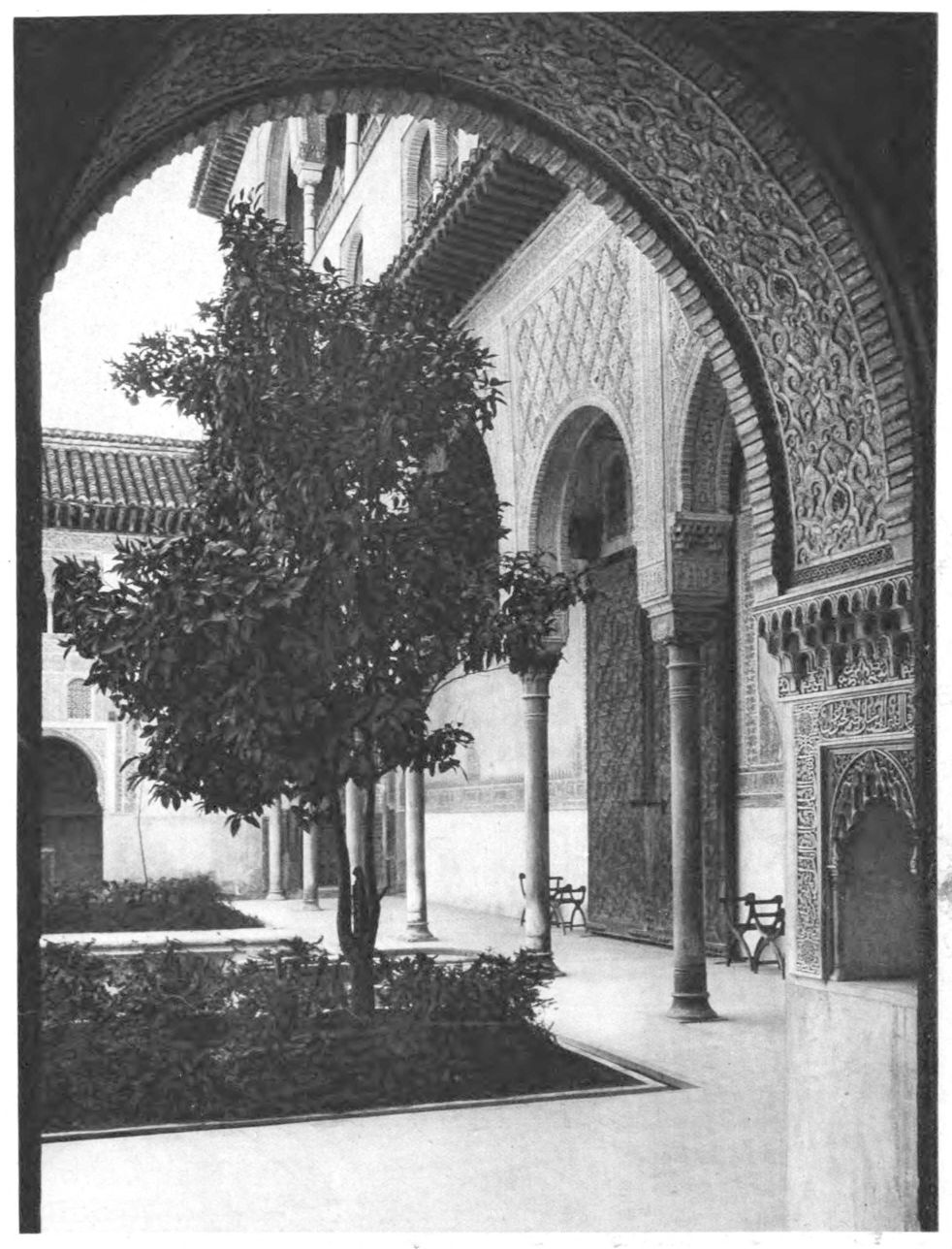

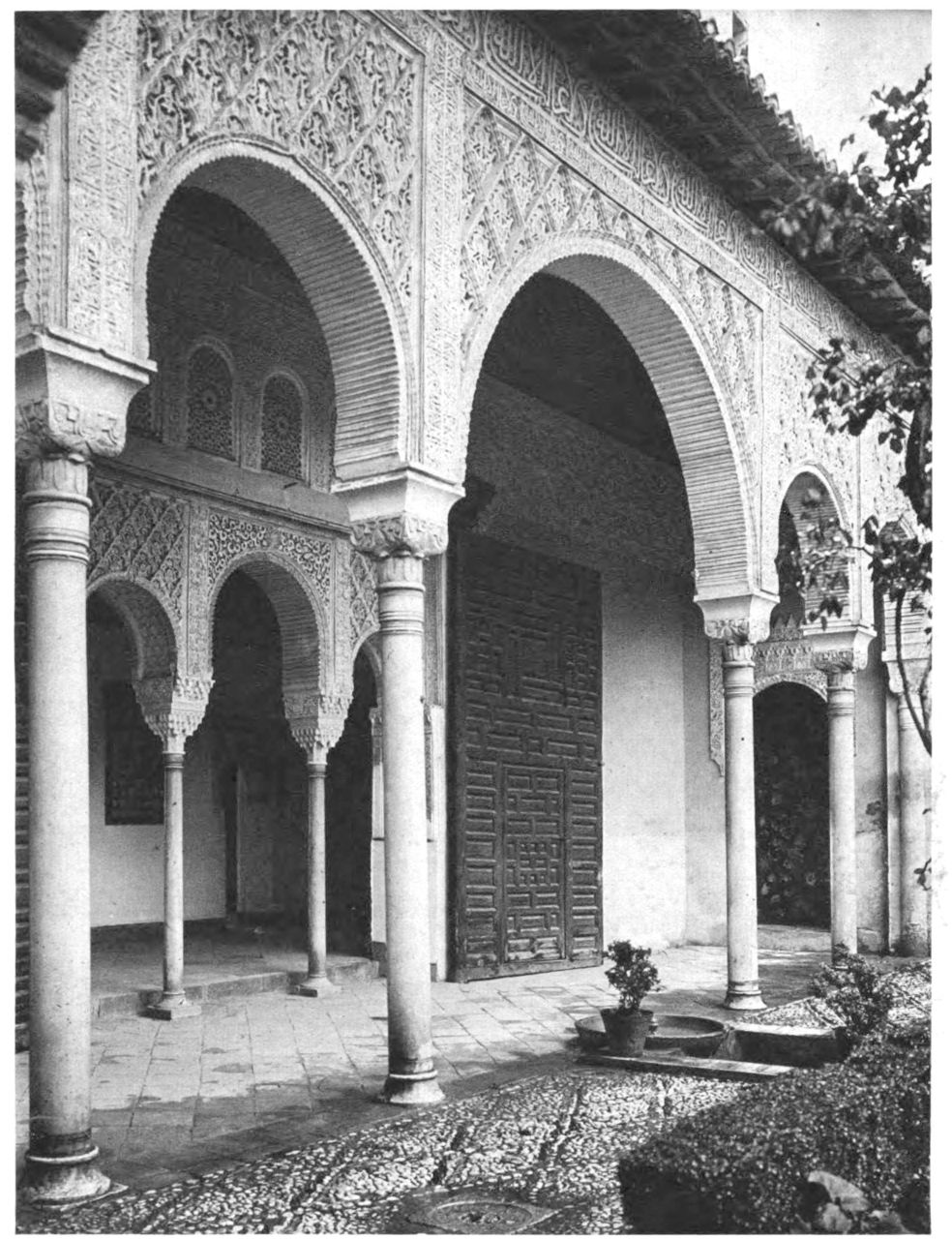

The great Gate of Judgment is passed, and an inconspicuous door leads to the Court of the Myrtles. Here one feels surrounded by the spirit of the Orient. Delicate jasper and alabaster columns support the airy arches which are swung like lace veils from arcade to arcade. The emerald-green waters of the fountain gaze dreamily skywards and at all the bright beauty of the scene.

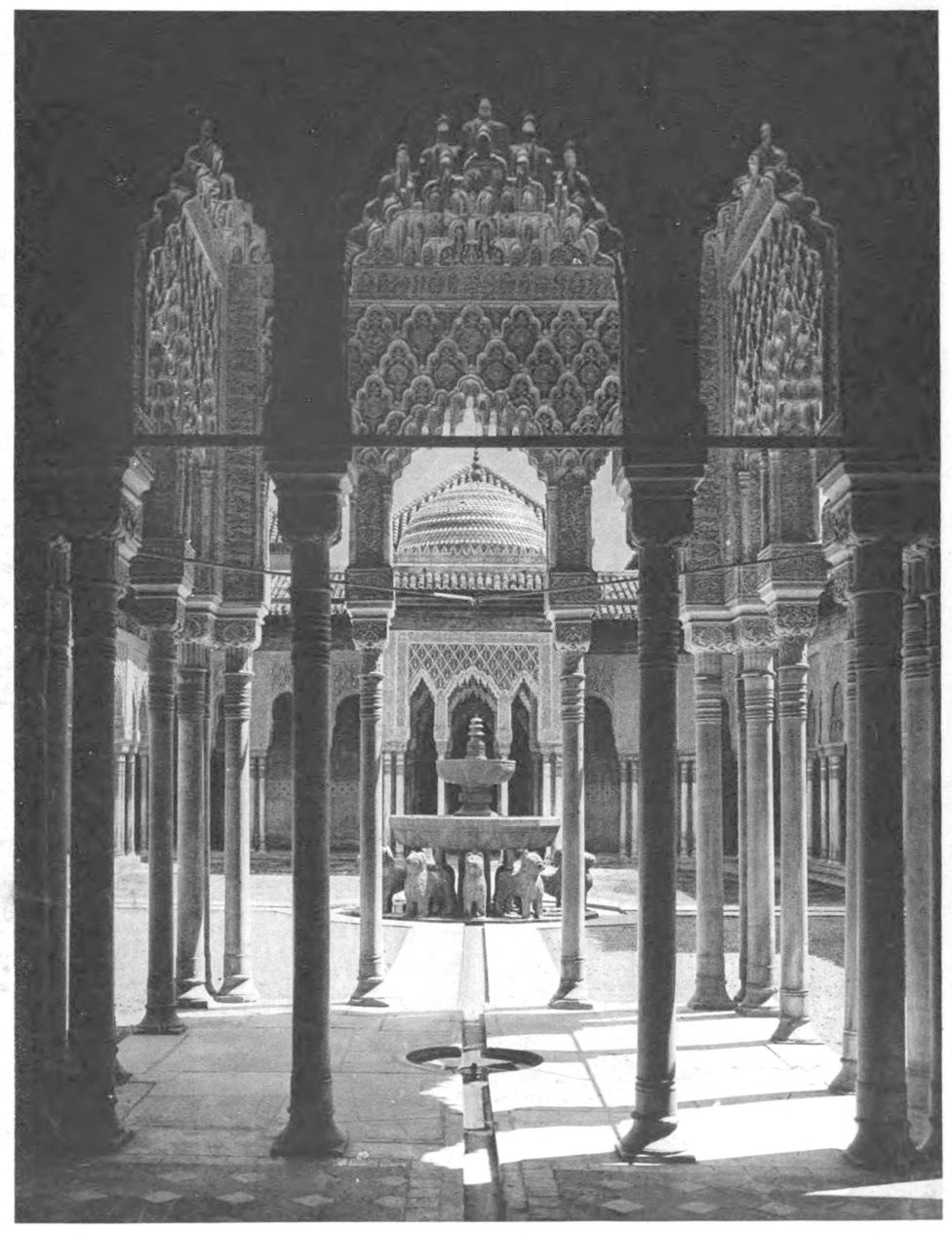

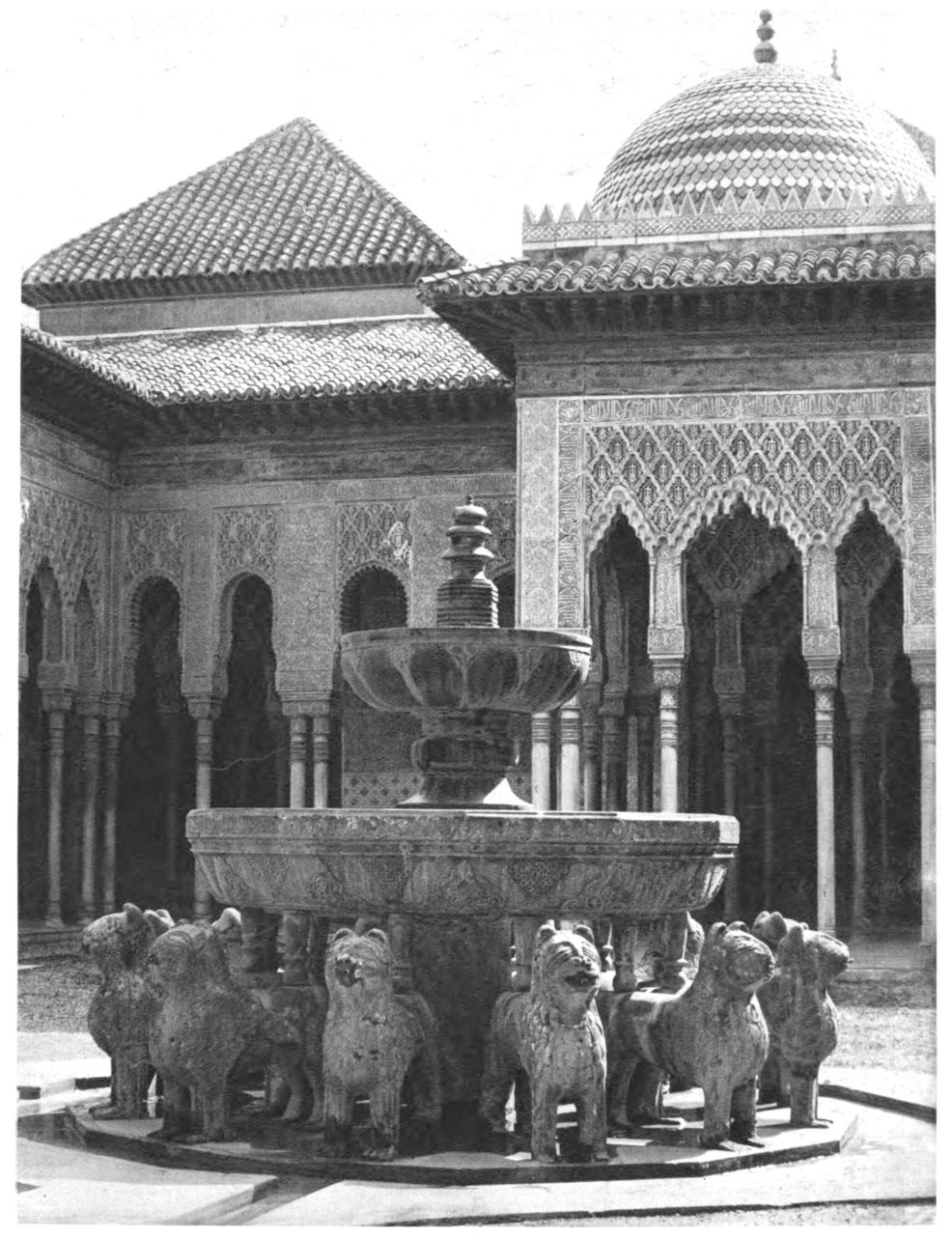

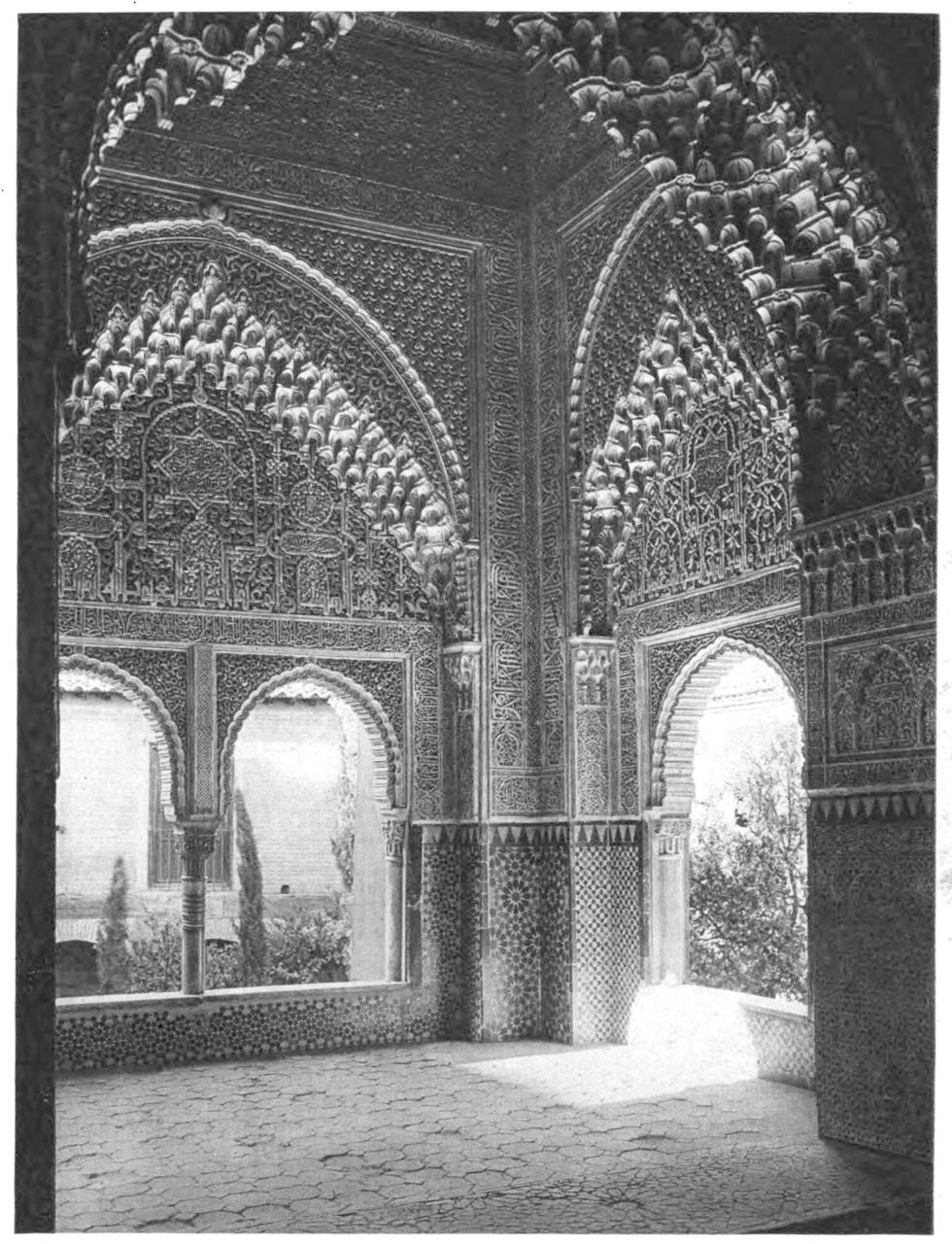

Then there is the Court of the Lions, subject of so many songs, with the filigreed architecture of its covered walks. Enchanting in its delicate tracery and beauty, it is a fairy-tale, a poem in stone, infinitely rhythmic with music. And indeed, music is the only language that can render such beauty.

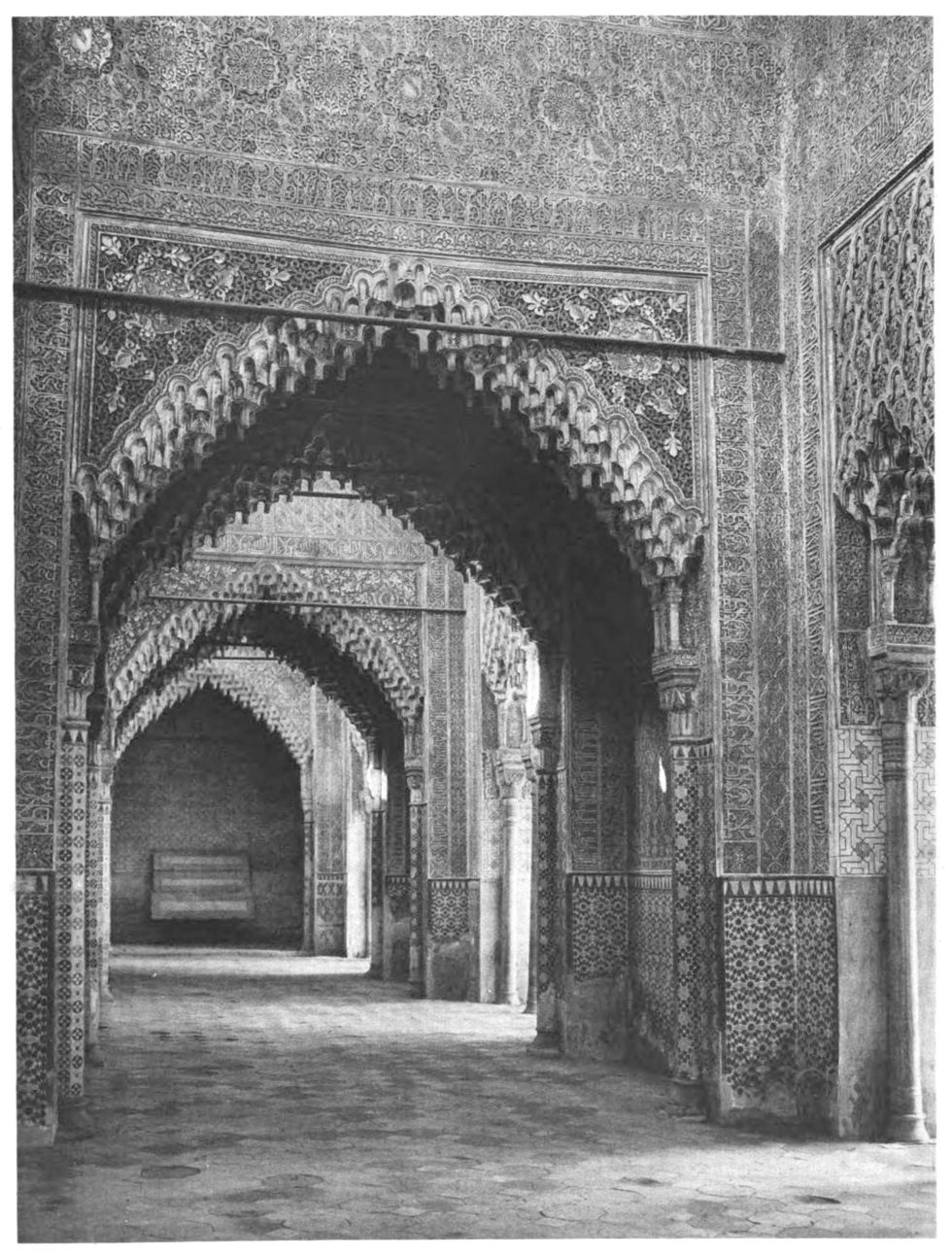

The magnificent halls are full of a wealth of ornamentation. The walls are rainbow-like with the colours of Persian carpets and Cashmere shawls. Arabic inscriptions are scrolled along these labyrynths of colour, praising in exalted words the mystic beauty of the halls. One runs joyously: “God has filled me with such a plentitude of beauty that even the stars stay in their course enchanted to gaze on me.”

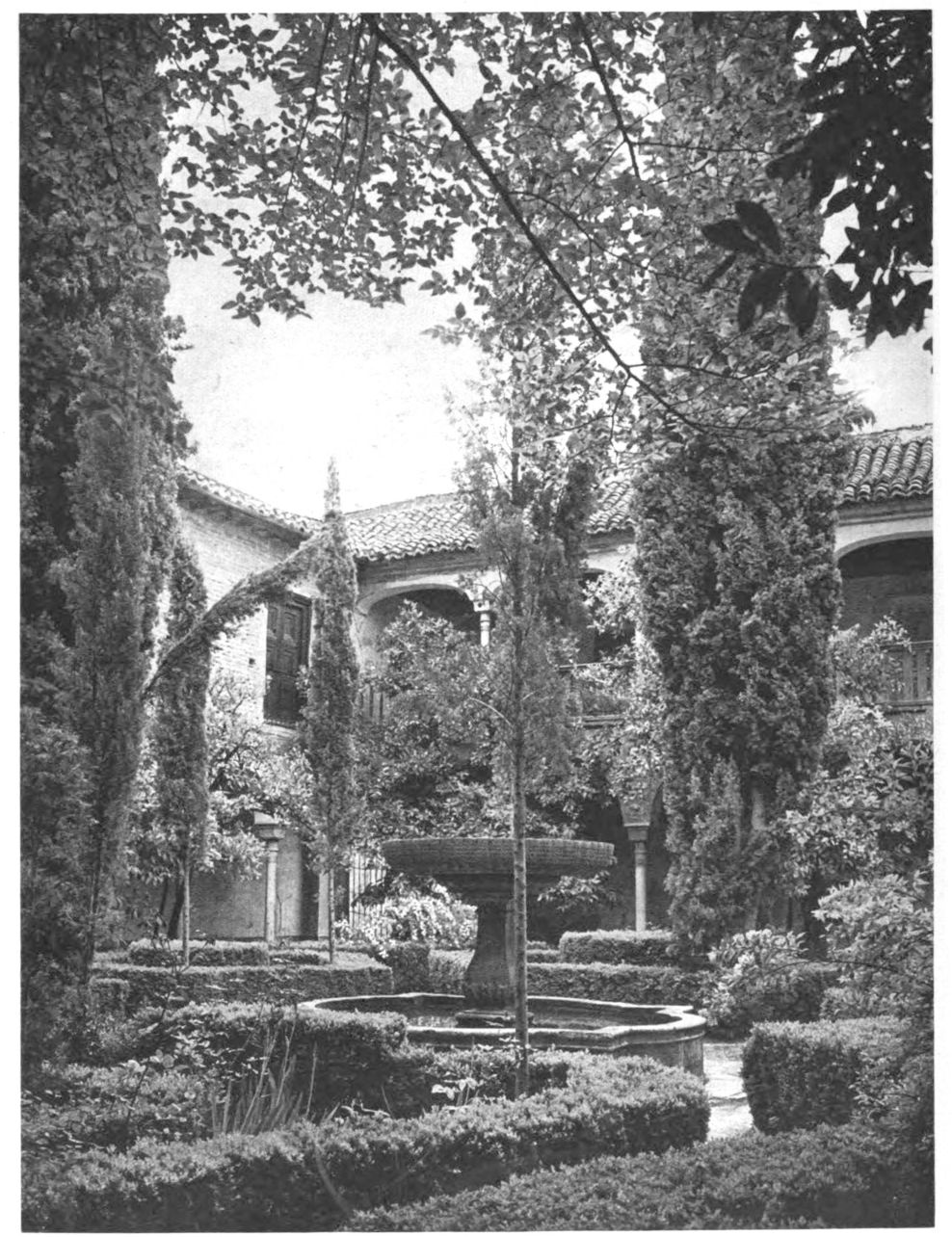

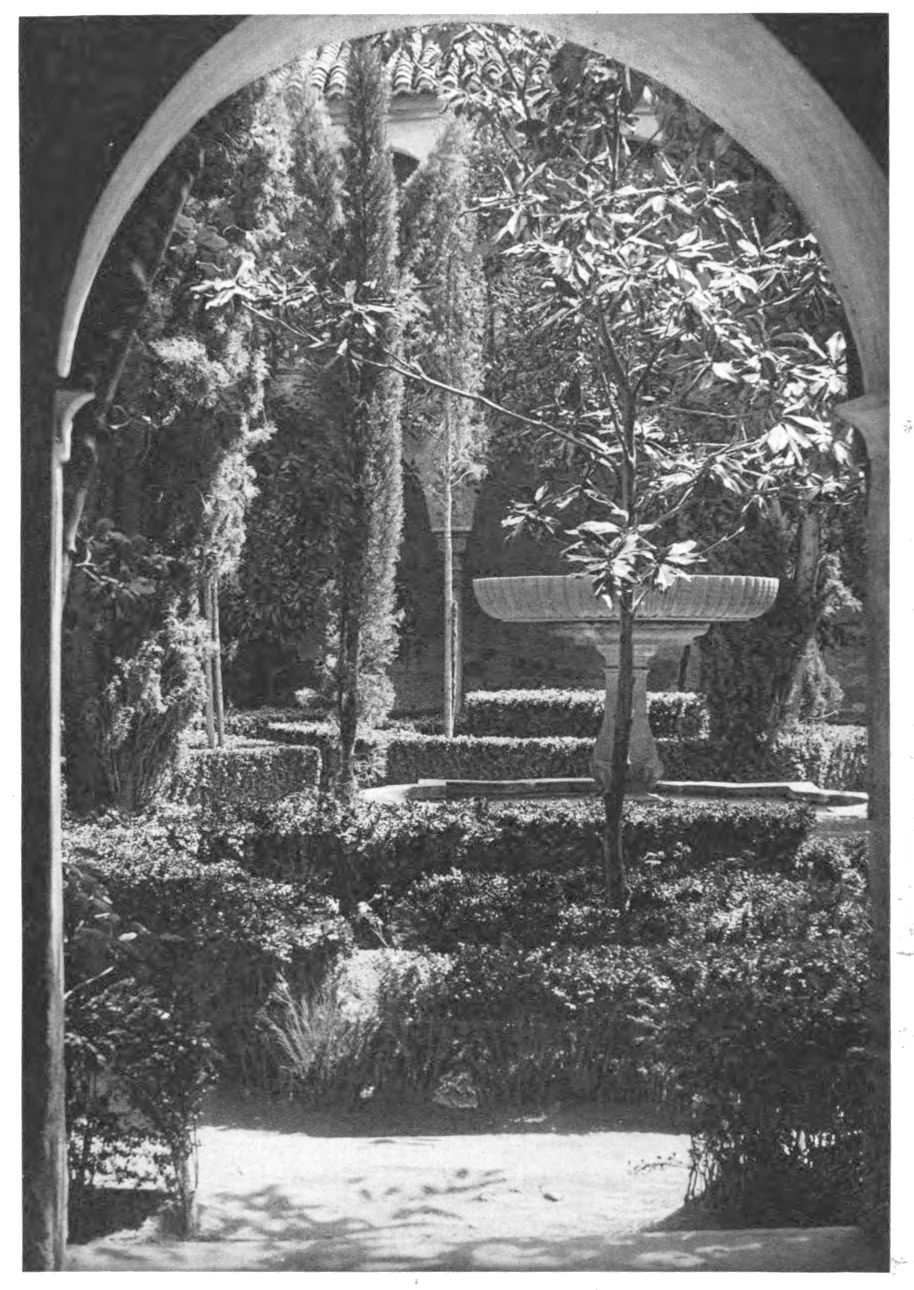

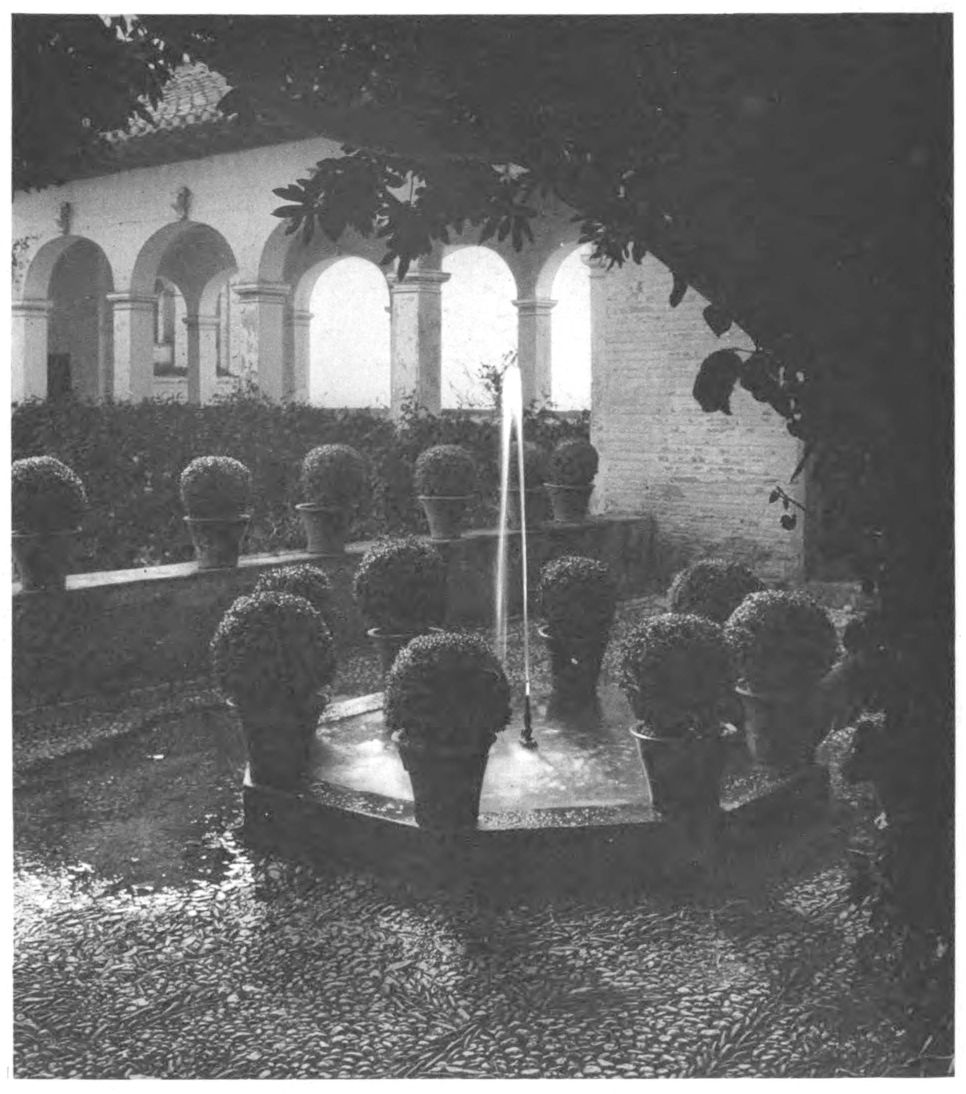

Once beautiful sultanas looked out from the “Seat of Admiration” (as the Arabs called that jewel of the Alhambra, the Mirador de Daraca,) into the pretty garden filled with the heavy scent of roses, jasmines and oleanders. A swaying mass of tangled climbing plants are festooned from laurel to cypress, and from cypress to orange-tree. In the middle there is a marvellously delicate fountain basin from the edges of which the water slides and drips with tuneful sound as if it fain would tell of long forgotten beauteous days.

We leave the glittering fairy-palace full of memories of the Arabian Nights, and our lips whisper the wish of the Arabic poem writ over a little niche:

Nay, as long as clouds sail the skies, and seekers after beauty rove on earth!

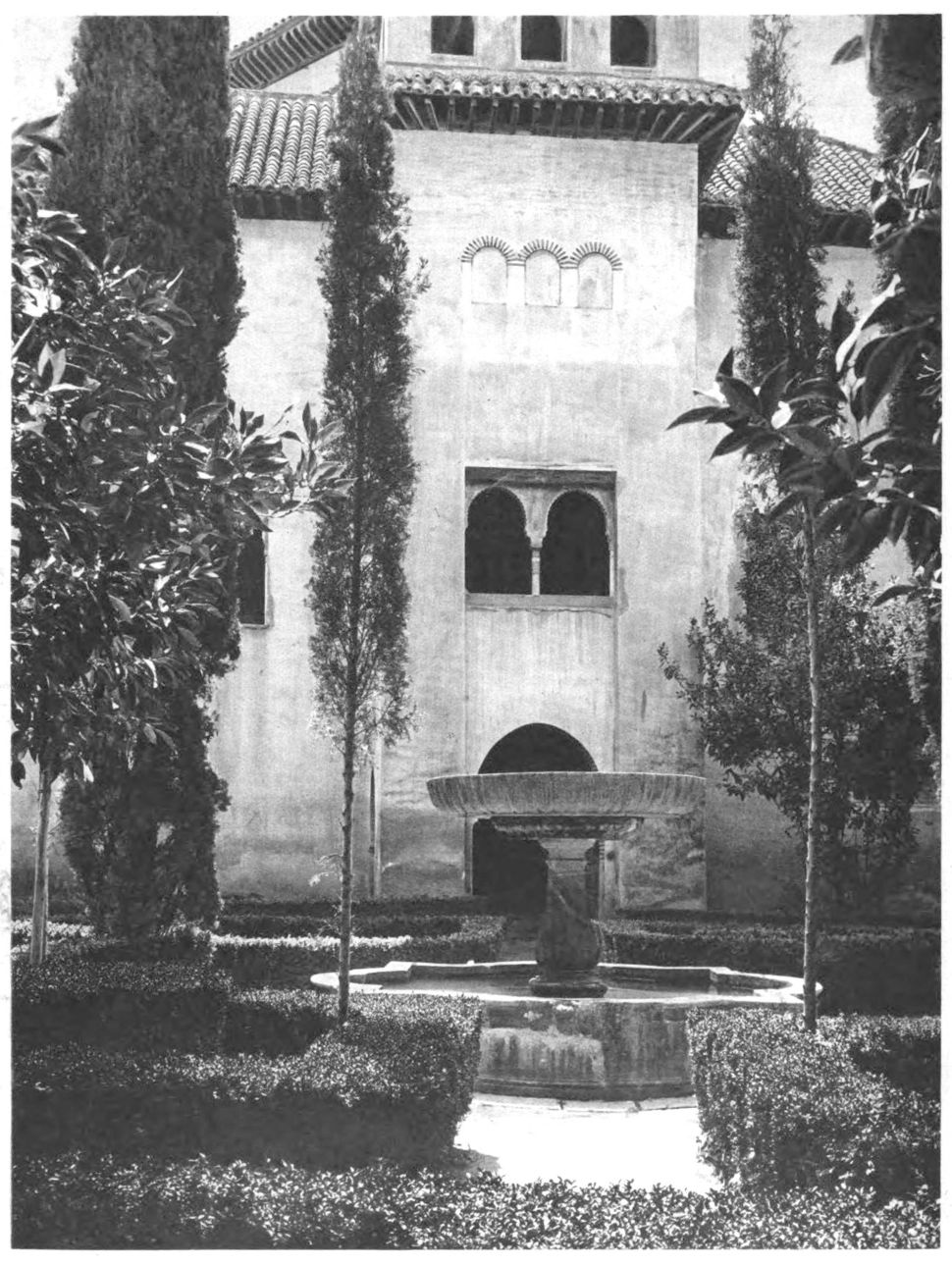

This is the mood one is in when climbing further up the mountain to the Moorish summer palace, the Generalife.

We are met, as it were, and shown the way by a double row of slim black-green cypress—dark trees of silence.{ix}

The Generalife is enthroned far up on the heights, and embedded in terrace-shaped gardens.

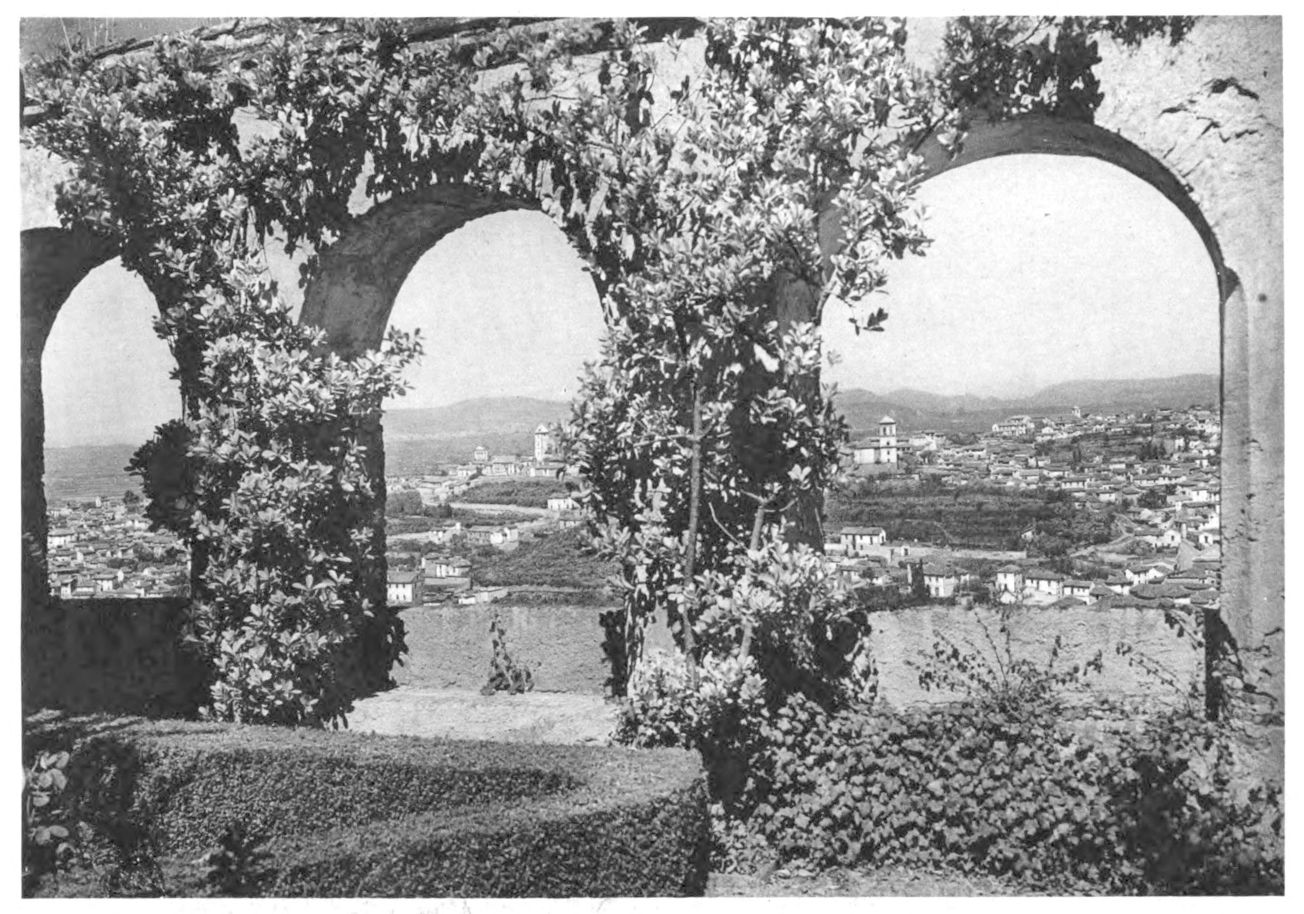

The gardens! In them nature has enfolded all her abounding wealth of colour. Crimson-ramblers, wistarias, vines and ivy smother the walls. Mangolias, oleanders, almond trees, laurels, cypresses, araucarias, olive trees, agaves, palms and mimosa vie with one another for precedence. Flaming pomegranate blossoms, blood-red roses, violet mallows, blue fleurs-de-lis, white jasmine, yellow narcissi, and golden oranges in dark green foliage are a riot of colour. Ball shaped myrtles surround the little fountain, listening to the babbling of its silver waters, and in the twigs the song of birds greeting nature in her holiday garments.

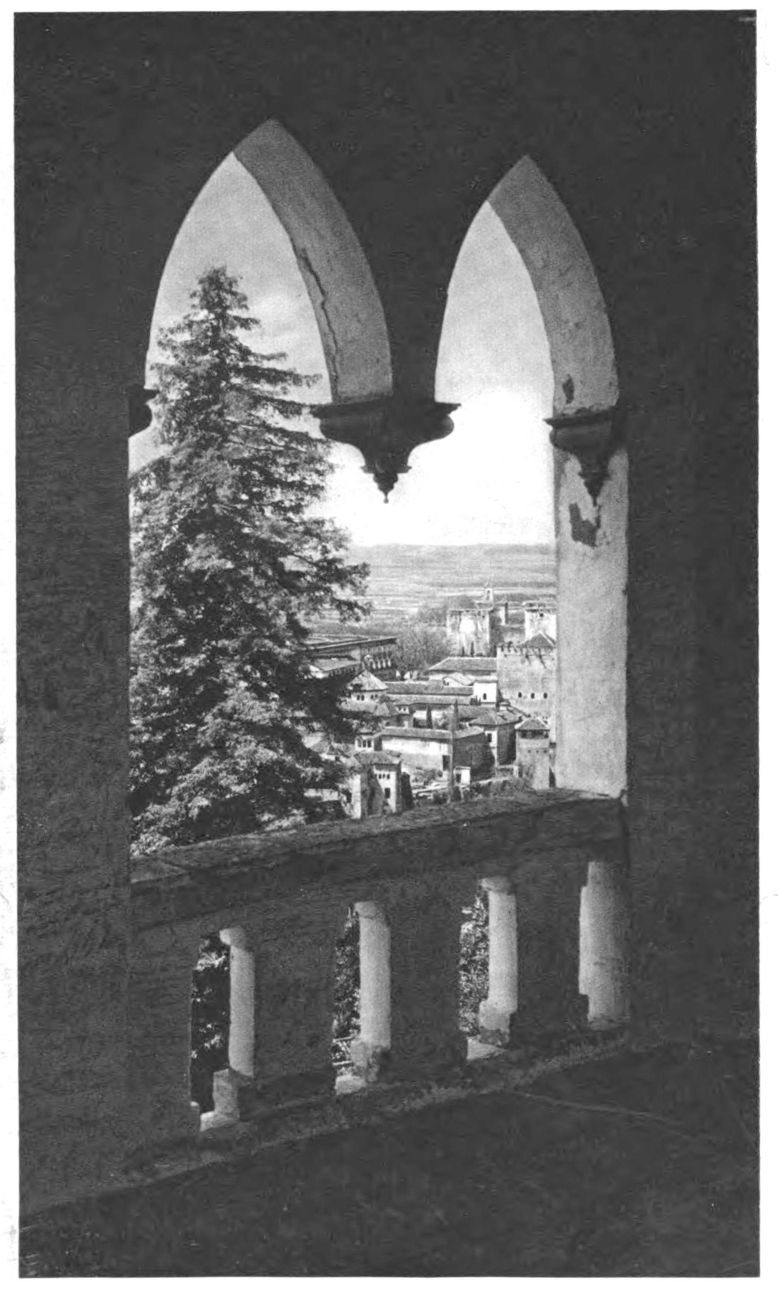

Wondrous peace broods o’er this land. Through trees and halls and wall arches there is a magnificent view of the Alhambra and the multi-coloured houses of the town at its feet, and further on to the picturesque Albaicin, and over cactus-grown Sacromonte with its gypsy cave-dwellings, and still further to the snow-capped Sierra Nevada. Another glance shows the fertile plains of the Vega through which the clear waters of the Genil flow.

However full of radiant happiness the day may have been, it is outshone by the sinking sun casting a golden halo over the country-side. The walls of the Alhambra, once so fiercely fought for, stand forth as though dipped in blood. The distant mountains glitter golden-bronze, and the snowy sides of the Sierra Nevada scintillate in flames. Slowly the fair fires die down, and a chill spectral white falls upon the snow summits. The eventide is there and with it the stars.

The Spaniards have coined a proud sentence: “Quien no ha visto Granada, no ha visto nada!” He who has not seen Granada has seen nought! And I should like to add: He who has seen Granada and the Alhambra on sunny spring days, bears with him a talisman to ward off sorrows in dull days, and can never be completely unhappy again in life.

⚪

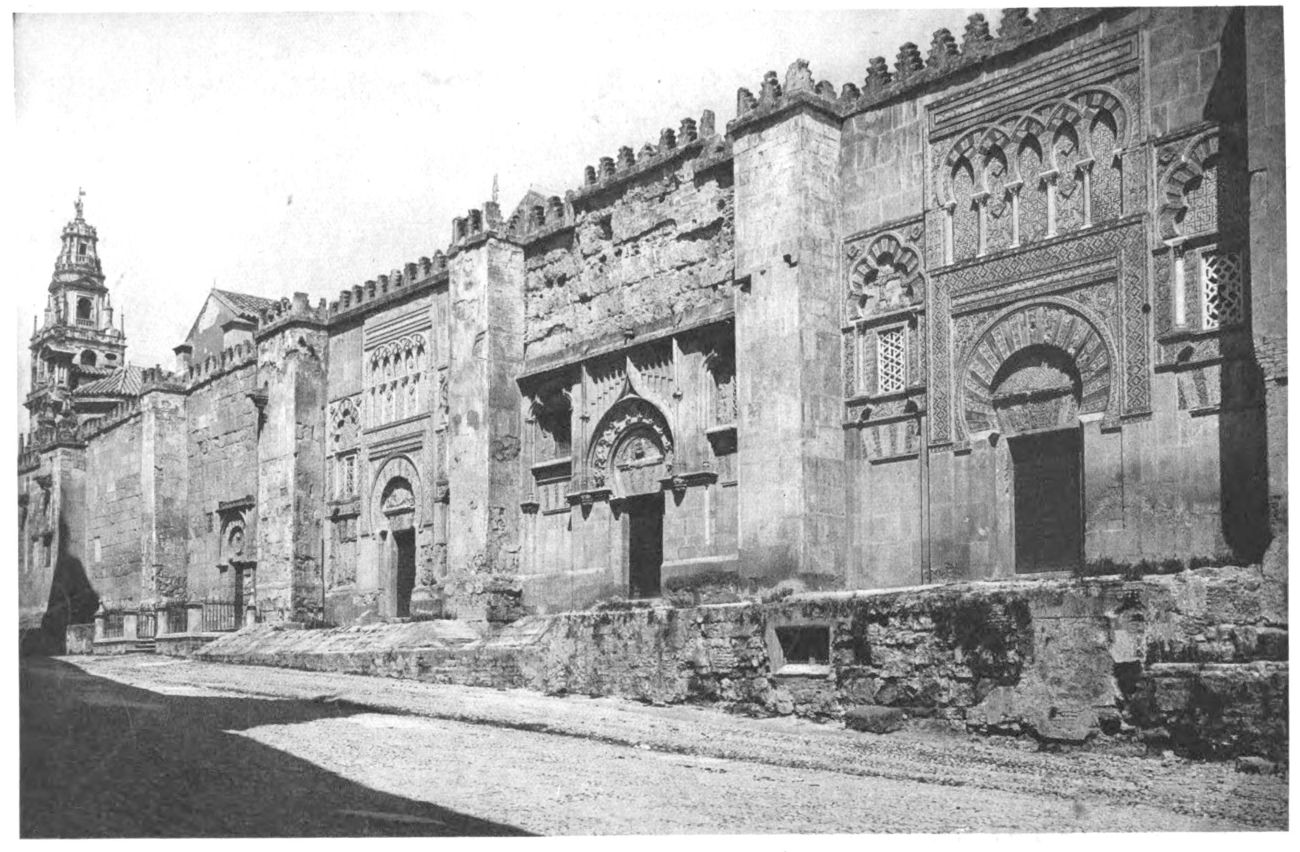

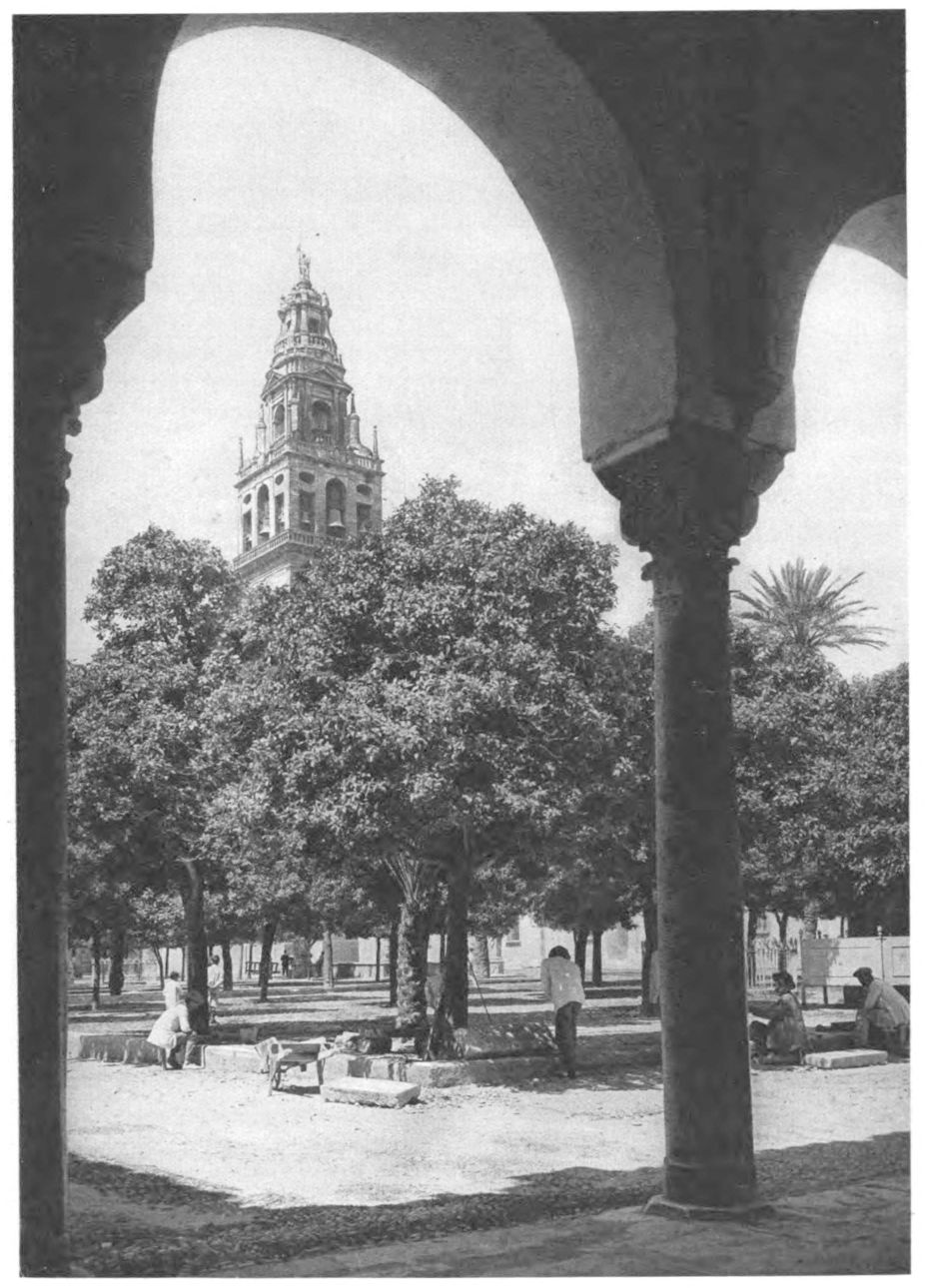

The Mosque, Cordova. A nation set forth to convert the world to its faith. Its battle-cry in this holy war was Allah! Victory after victory was gained, till finally the triumphal march of fanaticism was stopped by the opposing faith of its religious adversaries. The waves receded, and the Cross triumphed over the Crescent. This struggle of two faiths and two continents left indelible marks on the fields of battle.

These wars had been carried on in the name of God. Sacred edifices were erected to the victor. On the ruins of the mosque arose the most beautiful cathedral in the world as token of victory. Spain never would have received the impress she bears to-day without those bitter religious wars.

Cordova was the jewel among Moorish occidental towns, destined to outshine the sister cities Damascus and Bagdad in the far Orient. It was here that all the wealth and pomp of Moorish domination was displayed. Cordova’s population exceeded a million souls. It was the seat of Arabic art and profound learning; the centre of religious life. The muezzin called the faithful to prayers from 3000 minarets. Cordova became a new Mecca which drew crowds of pilgrims from the East to the West.

What has now become of this metropolis? A shadow! Wandering through narrow streets of the town one seems to be in Cordova of a thousand years ago. The old cobbled pavements are probably the same, the houses too, behind whose trellised windows the harem was hidden. The old crooked, narrow and confused mass of streets are still there. Once in a while a palm is seen leaning over white walls across the street; open doors offer views into pleasant court-yards.{x}

The Mezquita, the Mosque, stands like a dark rock surrounded by the white trembling light of the sea of houses.

A wonderful gateway leads to the Orange Court. The fruit and flowers of these trees perfume the air with incense. High up, backed by the blue sky, the palm trees are waving in the wind. Fountains are plashing. Once they served to refresh burnoosed dusty and foot-sore pilgrims come from afar to serve their God here. The faithful bathed in these fountains before purifying their souls in Allah’s house.—Now the fountains are perpetually surrounded by the town maidens who come to fetch a cooling draught in their finely curved earthenware jugs.

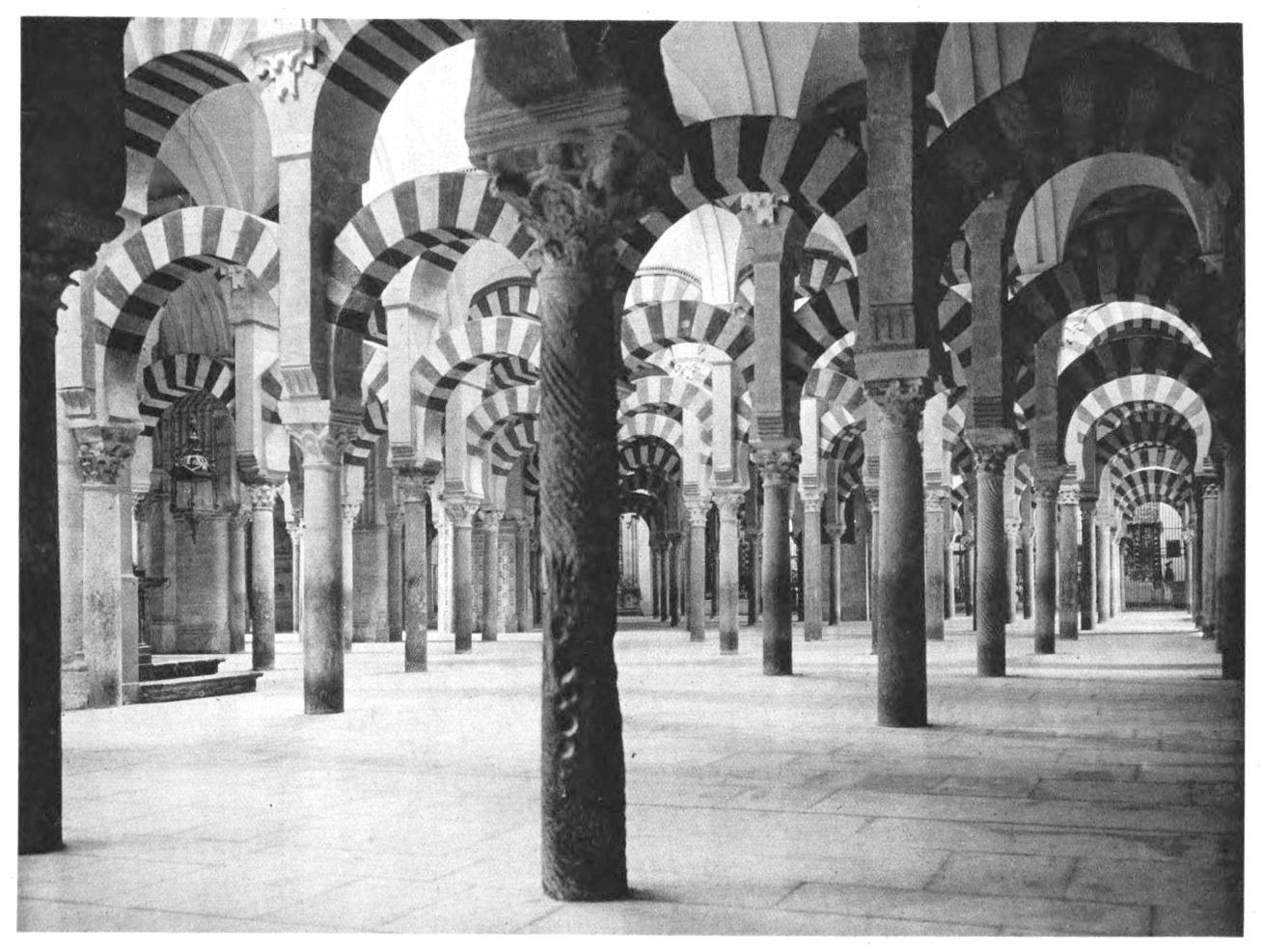

The impression on entering the forest of columns that support the mosque is both unexpected and overpowering. Is this not a petrified palm wood? And does not this stony grove incorporate the conception of infinity? There is a mystic dusk among these columns that lends to them an endless space of silence and eternity: the symbol of belief.

It is to the credit of the victorious Christians that they did not cool their religious ardour by destroying this Islamitic place of worship. It is extremely regrettable that their descendants have treated this monument of Mohammedan culture with such carelessness.

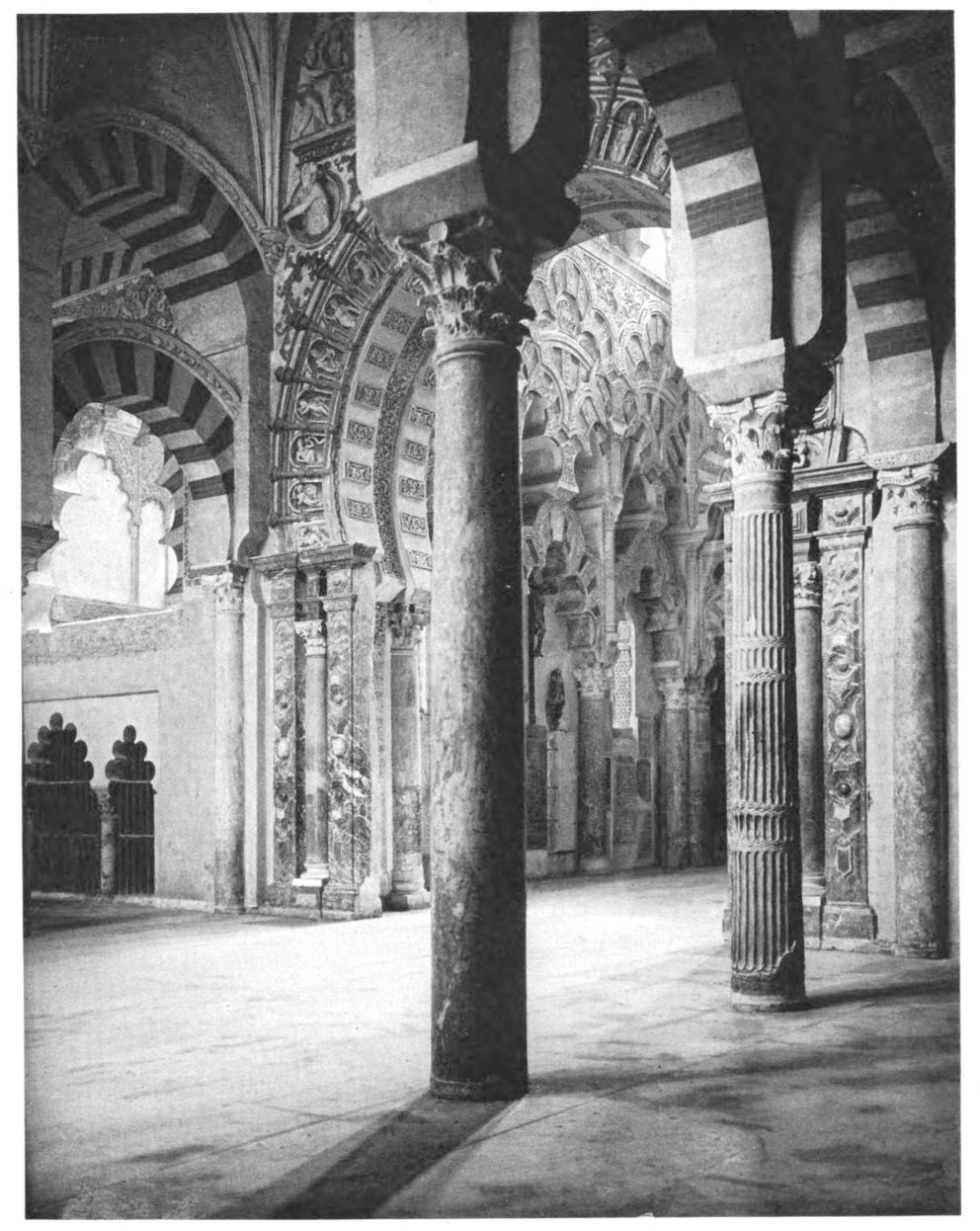

The mosque became a Christian church. Where once the cry of “Allah illah Allah!” echoed thousandfold, “Praise be the Lord!” is now sung. The first deed was to erect altars in the door-niches. Then seventy pillars were laid low, and a choir with the High-Altar erected in their stead: a church within a church. Charles V. was reluctant to give his permission for these alterations. When he came to Cordova and saw what had been done, he exclaimed in perturbation: “What you are building can be seen anywhere. You have destroyed what was unique in the world.”[B]

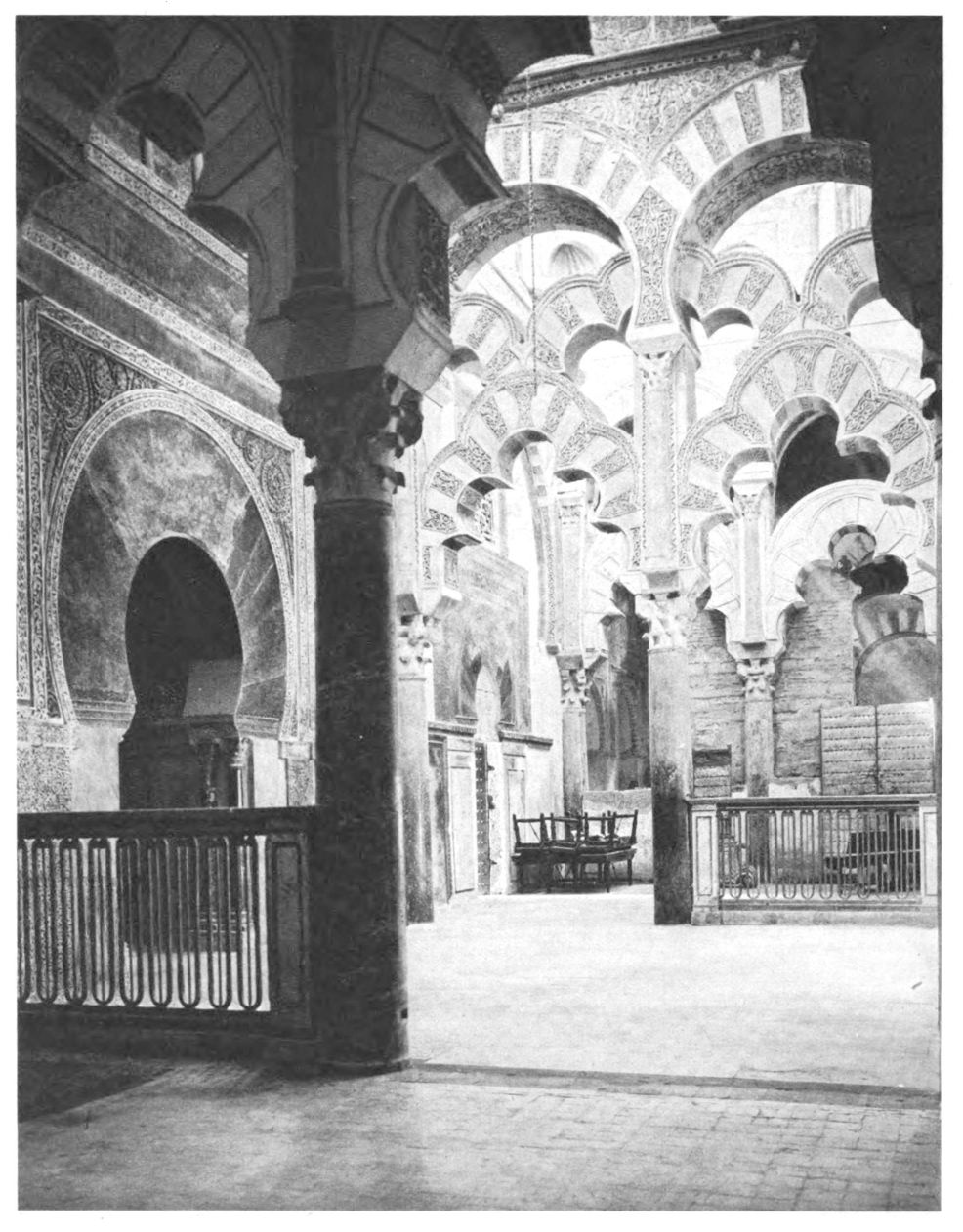

Untouched in its pristine beauty, hidden in semi-darkness, not far from the Holy of Holies of the Christian church, stands the Holy of Holies of the mosque, the Mihrab or prayer-niche in which the Koran was kept. It is a jewel of Moorish art. Whereas the rest of the mosque columns are connected by double horse-shoe arches, banded in red and white, here the beautifully chased dentated arches rise straight to the lovely curved dome. The niche socle is white marble of lace-like texture above which a profusion of colours glow: blood-red, rust brown, dark blue violet interwoven with a sublime sheen of gold. Perhaps the mosaic walls and lettered scrolls upon them have in some mystical manner caught the light of the thousand swinging lamps that once had cast their soft rays through the dim shades of space. For six long centuries all these glowing colours were hidden. Before Cordova was surrendered to the Christians the sanctuary was walled up. It was only discovered in 1815.

We pass entranced along the colonnaded aisles, enthraled by the wondrous beauty of this miracle in stone. It is like awakening from a fantastic dream to set foot again in the blinding sun of the silent town that has become the shrine of one of the most precious jewels in the world (50-60).

O

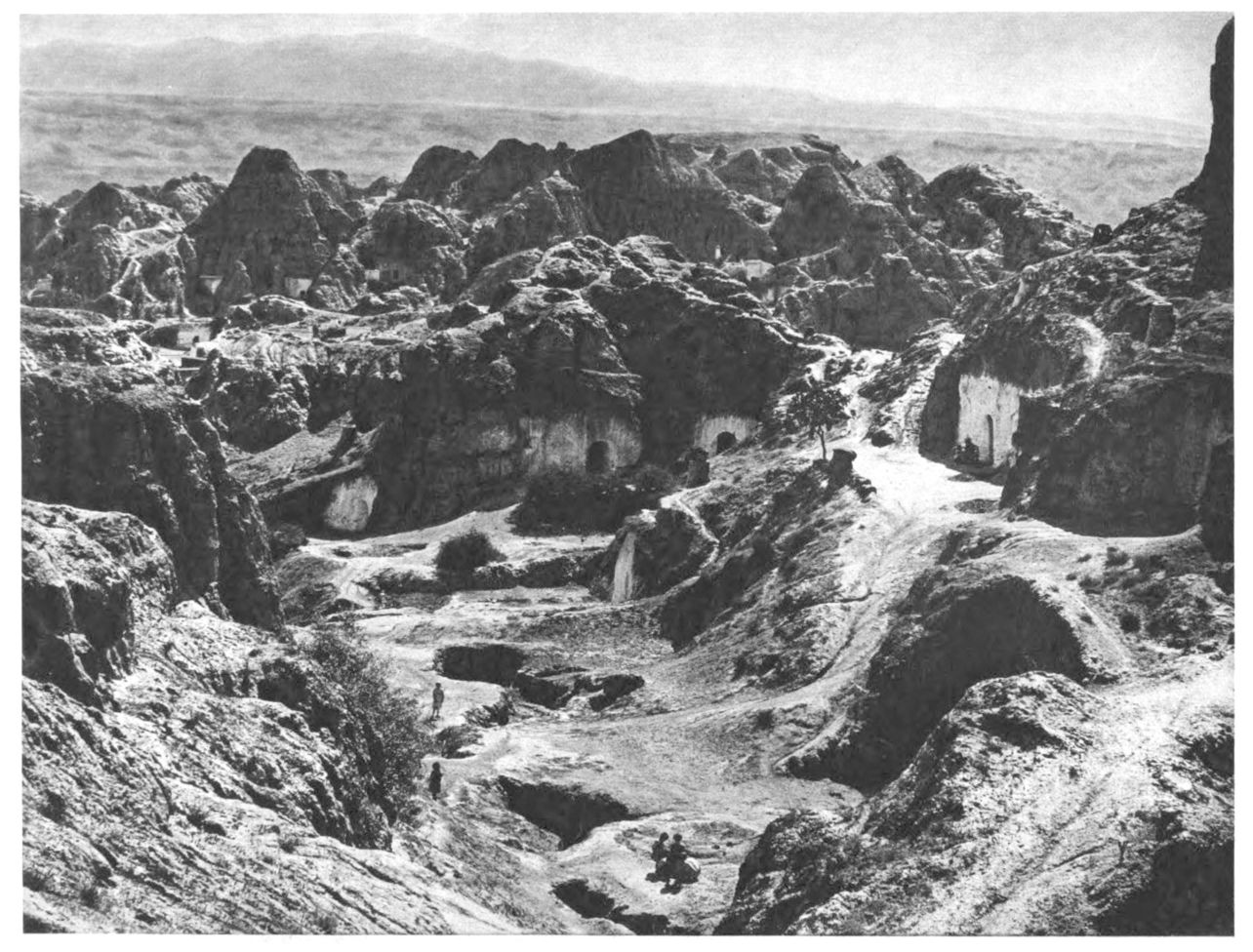

Moorish scenes far from the beaten track: A burning hot day in August.—The air trembles in the heat over the olive trees. The day hangs heavy in the blue vault of heaven. I had been wandering for long long hours, when all of a sudden my eyes were caught by a fata morgana: wafted perhaps from the coast of Morocco? No, it was{xi} no mirage. Impossible! Yet it did not disappear as I approached. Strange indeed was the scene: houses scattered like dice over a mountain (91).

A timid lad of whom I asked the name of the spot, slunk shyly past me. My map was of no assistance to me. At last I was informed that I had arrived at “la muy noble y bel ciudad Mochagar, llave y amparo del reino de Granada”. “What,” I asked “this hamlet still calls itself the key and guardian of the kingdom of Granada? But that kingdom was destroyed half a thousand years ago when the Moors were driven from Granada.”

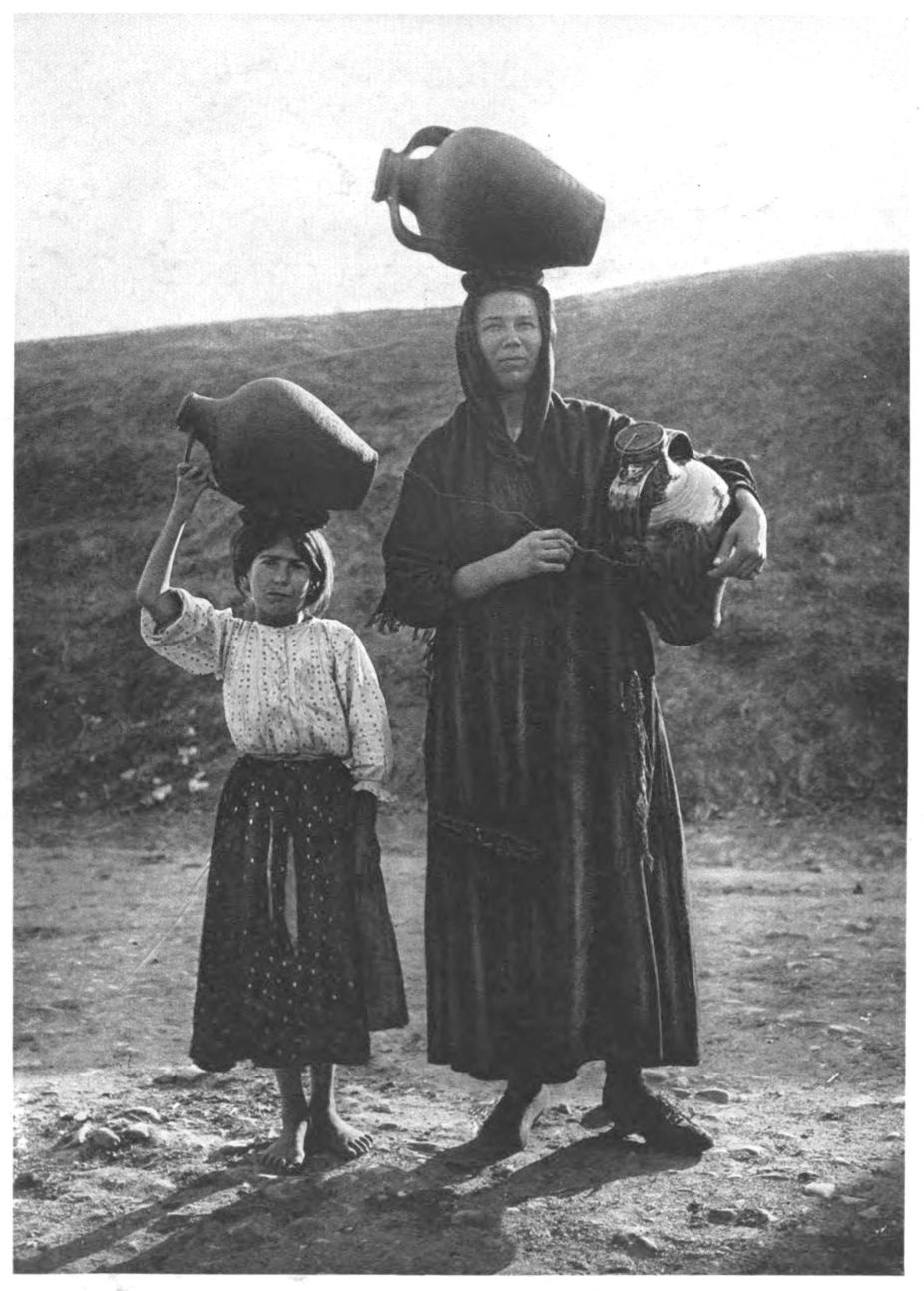

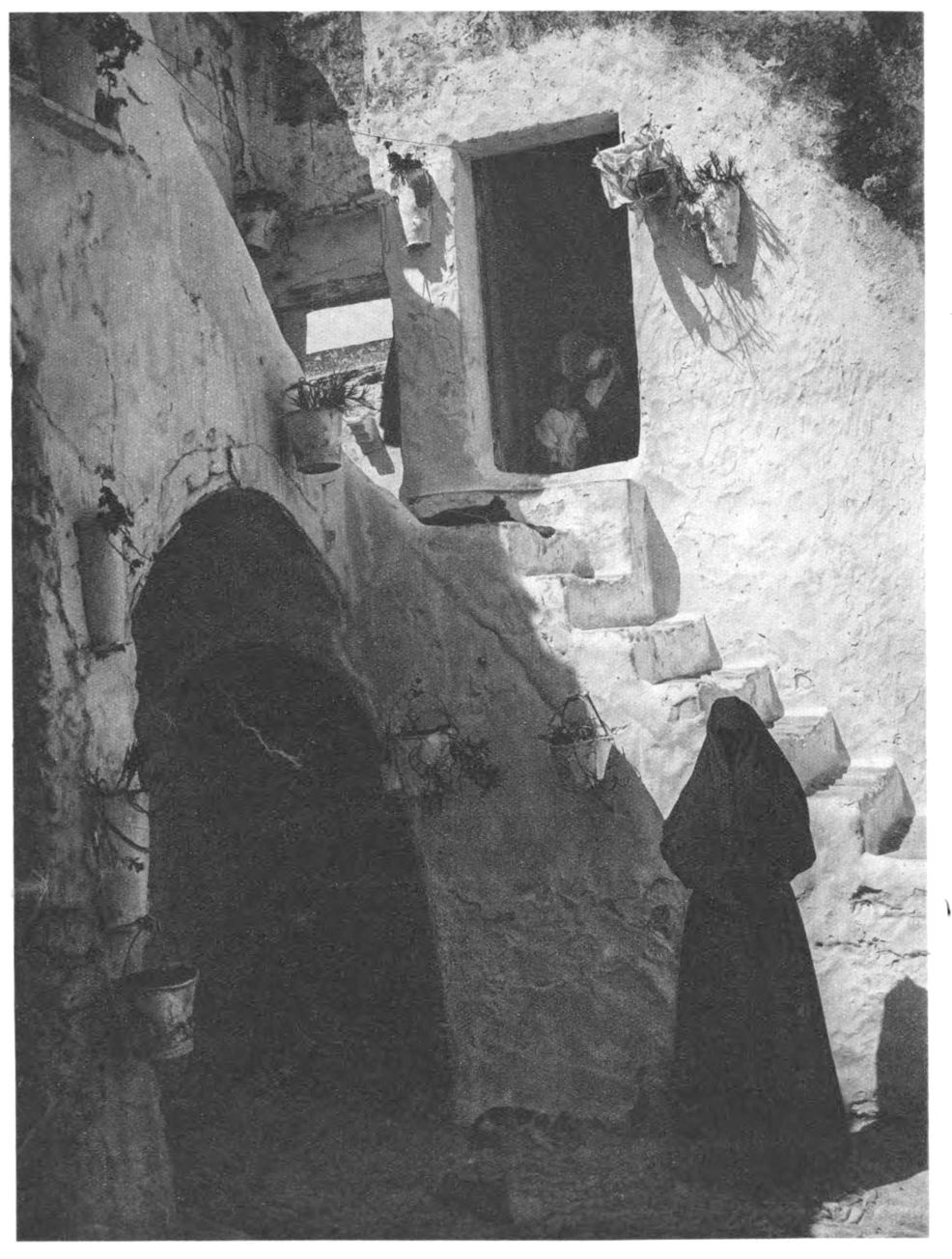

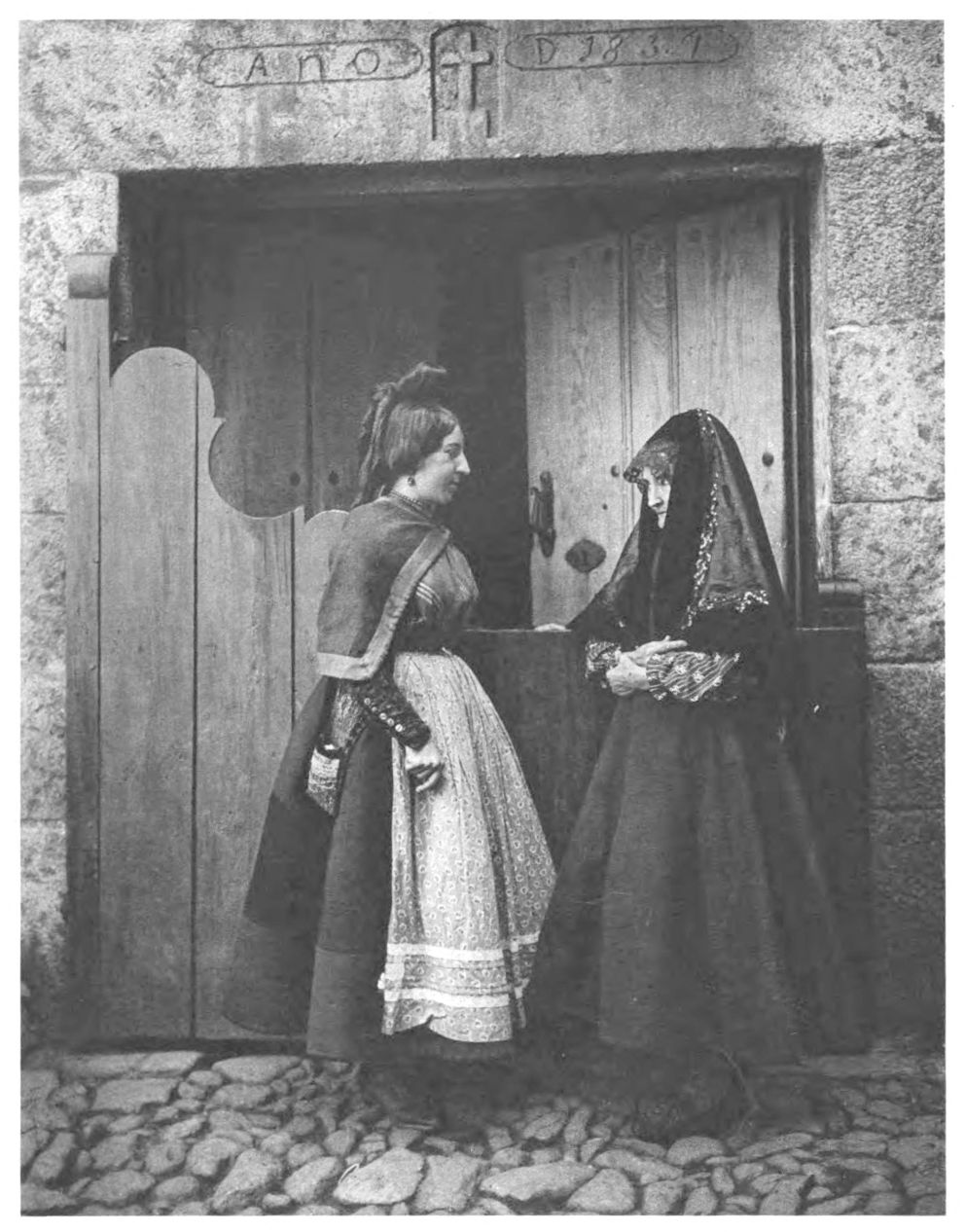

A miracle must have happened here that time should have remained stationary. Here was the pure Moorish impress. Most of the houses are windowless. The flat roofs are sometimes the road to the higher houses, and always their foot-stool. And although the water of baptism has wetted the women’s hair, they pass veiled in the Moorish fashion along the streets. With tucked up skirts and naked legs they step lightly along the steep alleys, returning from the fountains with water amphorae. They eye the foreign trespasser suspiciously and curiously. And when I requested the veiled women to let me take their photographs they stared at me, for they had never even seen a camera. I showed them a picture, and explained that I wanted to have theirs too. They refused. Finally one girl agreed. But an old scold hurried up and beat her for her frowardness: throwing herself away like that! In this Christian country I found shamefacedness and adherence to the laws of Mohammed. Let no mortal body serve as an image!

An old man with whom I spoke about this incident told me that if a girl no longer veiled her face, but hid her legs, there was not much left to spoil about her.

But I was determined that I would not leave without a picture of one of the veiled beauties. At last I succeeded, with the consent of the mother of one of the girls. The eye of my camera winked slyly when I took my snap-shot. In thanking the girl, I held out my hand, but she seemed quite taken aback, and hid her hands behind her. I pressed her to shake hands. I should not do her any harm. But her mother apologized for her saying: “No, she doesn’t mean to be rude, but it is not the custom in our country for a girl to let a man touch her hand before marriage.” Perhaps this little incident explains the once much-used expression employed by wooers “will you give me your daughter’s hand?” (90)

O

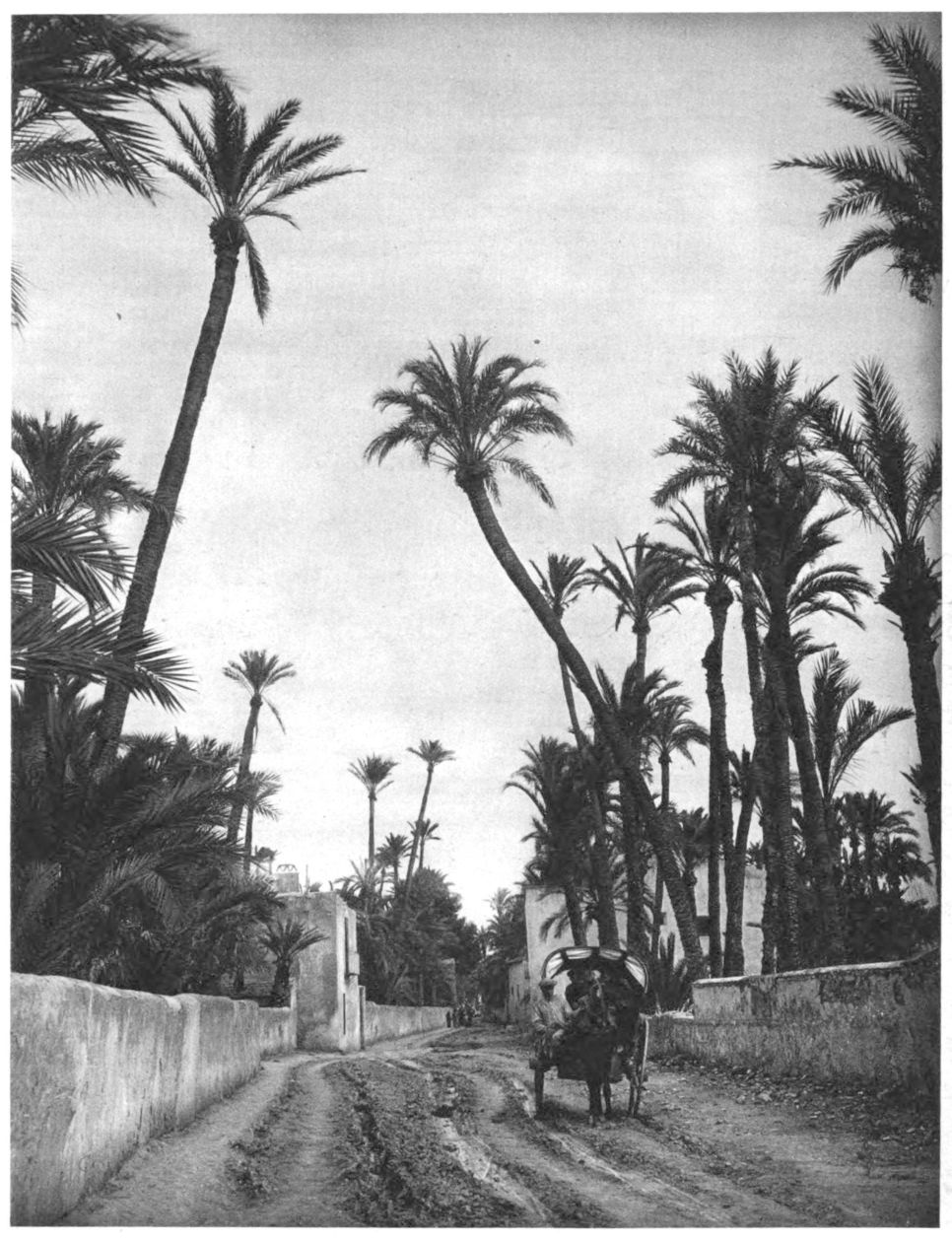

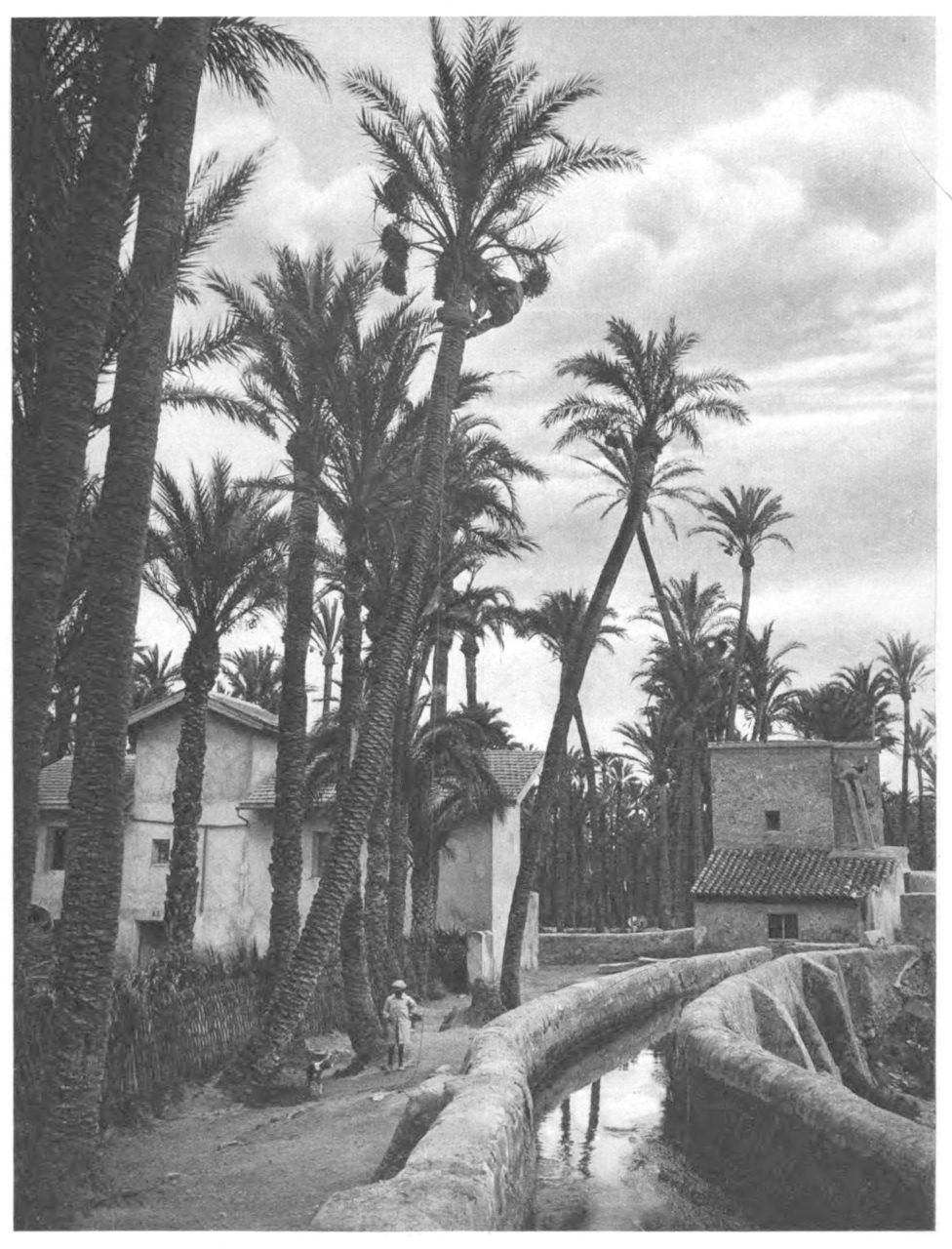

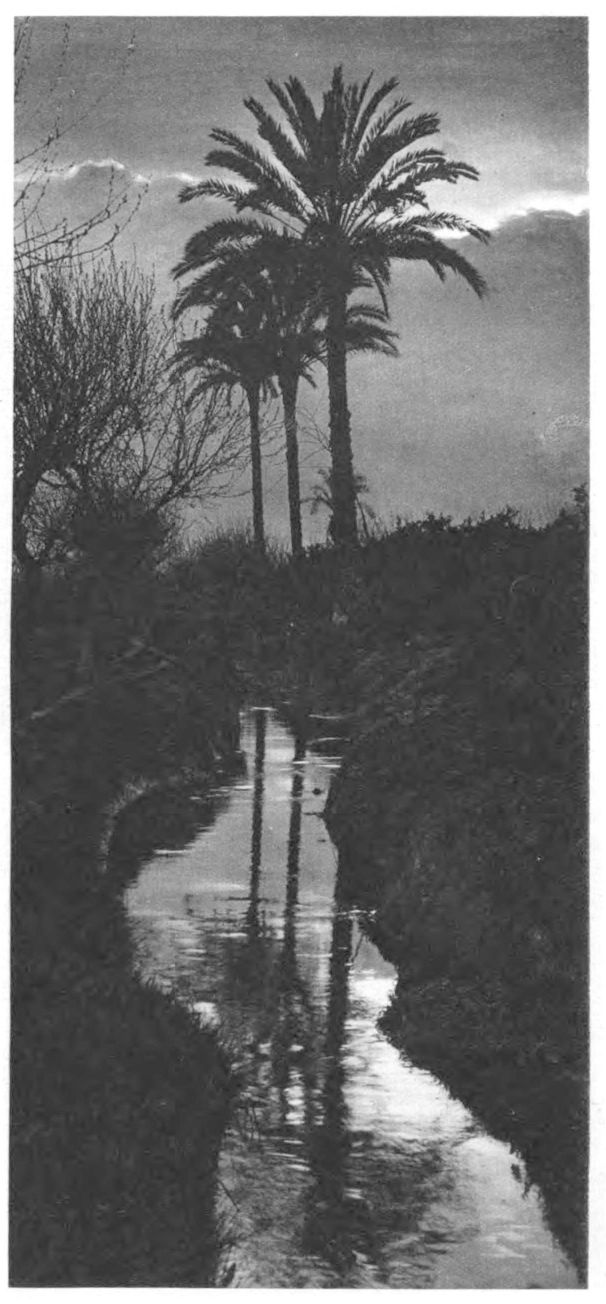

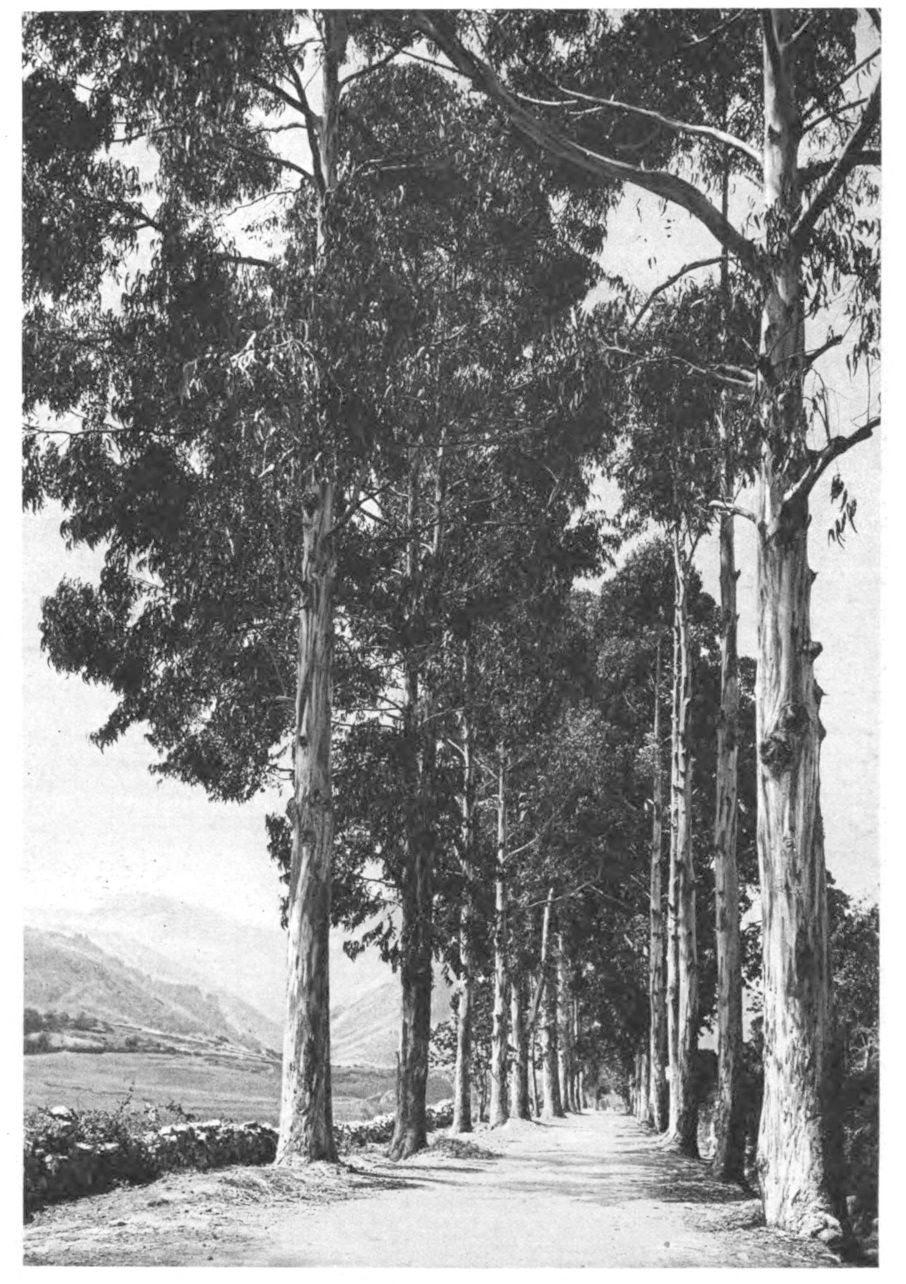

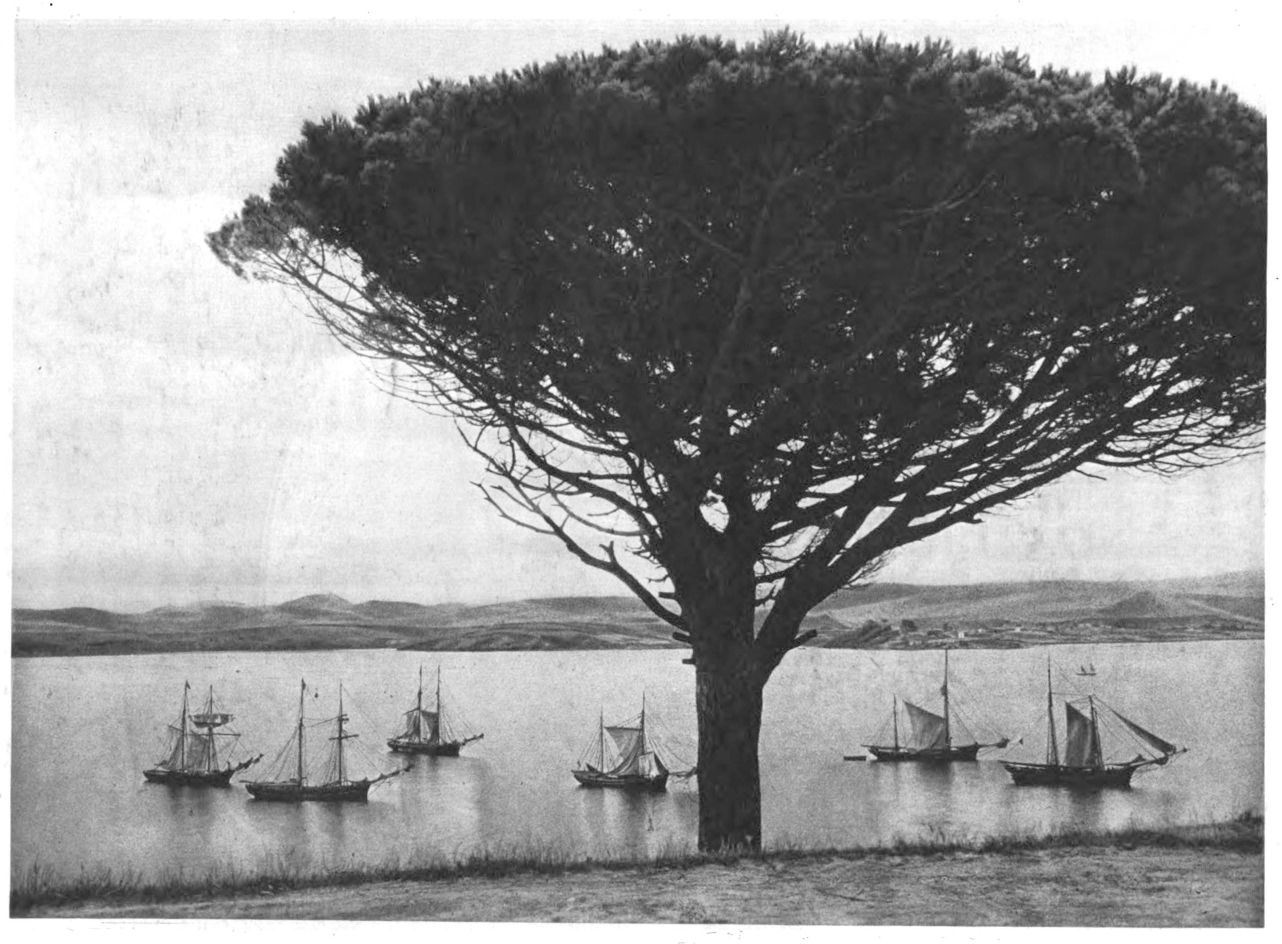

The Palm Forest of Elché (100-103). The only palm forest in Europe. It numbers more than 115000 trees, and is also a Moorish heritage. They caused the water to flow to this spot from a distance of 5 kilometres in order to create an oasis here in the desert—for the district is to-day little else. Palms must grow with their roots in the water and their crowns in the glaring sun. For years no rain has fallen on this spot.

The view is strange from the church-tower down on white houses over which the palm tops are spread like a canopy. Beyond the palm forest the grey-yellow desert plain surrounds this isle of peace. In the far distance the blue ocean sleeps in proud majesty. Death and life are here in close juxtaposition.

O

Easter in Seville. The train is rushing southwards over the arid Castillian high plateaux, which in summer are as empty as a beggar’s palm. The bare treeless Mancha has put on its modest spring garment which now shows in the distance like delicate green velvet. A short-lived joy! In but a few weeks the scorched ground will again be covered with a yellowish-gray pall.{xii}

At present the fresh breeze comes down from the mountains of the Sierra de Guadarrama. Scarcely, however, has the train wound its way through the wild cañons of the Sierra Modena, when spring opens wide her gate. A warm damp hot-house atmosphere is wafted into the carriage windows.

We are soon surrounded by meadows that are like a great flower-garden in which the blood-red poppy and golden-yellow primrose struggle for supremacy. Once in a while a village is seen dreaming like Sleeping Beauty among the flower groves. For a long stretch agaves and cacti fringe the track. Finally Seville sends forth her messengers in the shape of blossoming rose-gardens and orange groves laden with their ripe golden fruit. An ancient mangolia stretches a rosy blossom branch towards us, lingering on in its old age in this scene so full of yearning life. Tall slim palms nod to us, and yet new children of Flora crowd upon us to bring us Seville and spring’s friendly welcome.

Heedlessly the train clatters past all this beauty towards the white maze of Seville’s houses, above which towers that beautiful emblem of the town, the Giralda. At last the engine snorts noisily into the station.

But how different is everything to-day in front of the station. No yelling hotel porters, no carriages awaiting the passengers, no electric-car with clanging bell, no hooting of motor-cars.—The square is lifeless at this early afternoon hour. It is the “Semana santa”, Passion-week, that has cast this almost oppressive spell of silence over the great city. Even the brazen voices of the church-bells are muffled, as though that had gone into sacred mourning. The wooden banging of the Matraca calls hoarsely to prayers with dry and unmelodious voice.

The further you penetrate into the town, the more the sacred holiday stillness is ousted. All Seville is crowding, chattering and laughing to the Cathedral to see the procession. At last you have to stop. There is no getting through the impenetrable human wall. It is a strange procession that is passing by, as though conjured up from the Middle Ages. Huddled figures stalk past slowly and stiffly. They appear like spectres. Old pictures of witches and inquisitionary trials are recalled to my mind, for nowhere else have I ever seen such terrifying apparitions; never in life. Black cowls are wrapped around their bodies, and on their head are huge black conical hats a yard high. Long sable cloths, in which only two eyelets are pierced, are suspended over their faces down to their waists. A corded rope is wound round the penitential garments. The hands of the apparitions clasp rough wooden crosses, or metal staves, as tall as themselves. These figures march in front of a portable dais on which a life-like statue of the Virgin Mary is enthroned clad in magnificent garments thickly encrusted with gold.—The procession stops. The dais is lowered. A young woman steps from the crowd, turns her eyes to the Queen of Heaven and sings her praise.

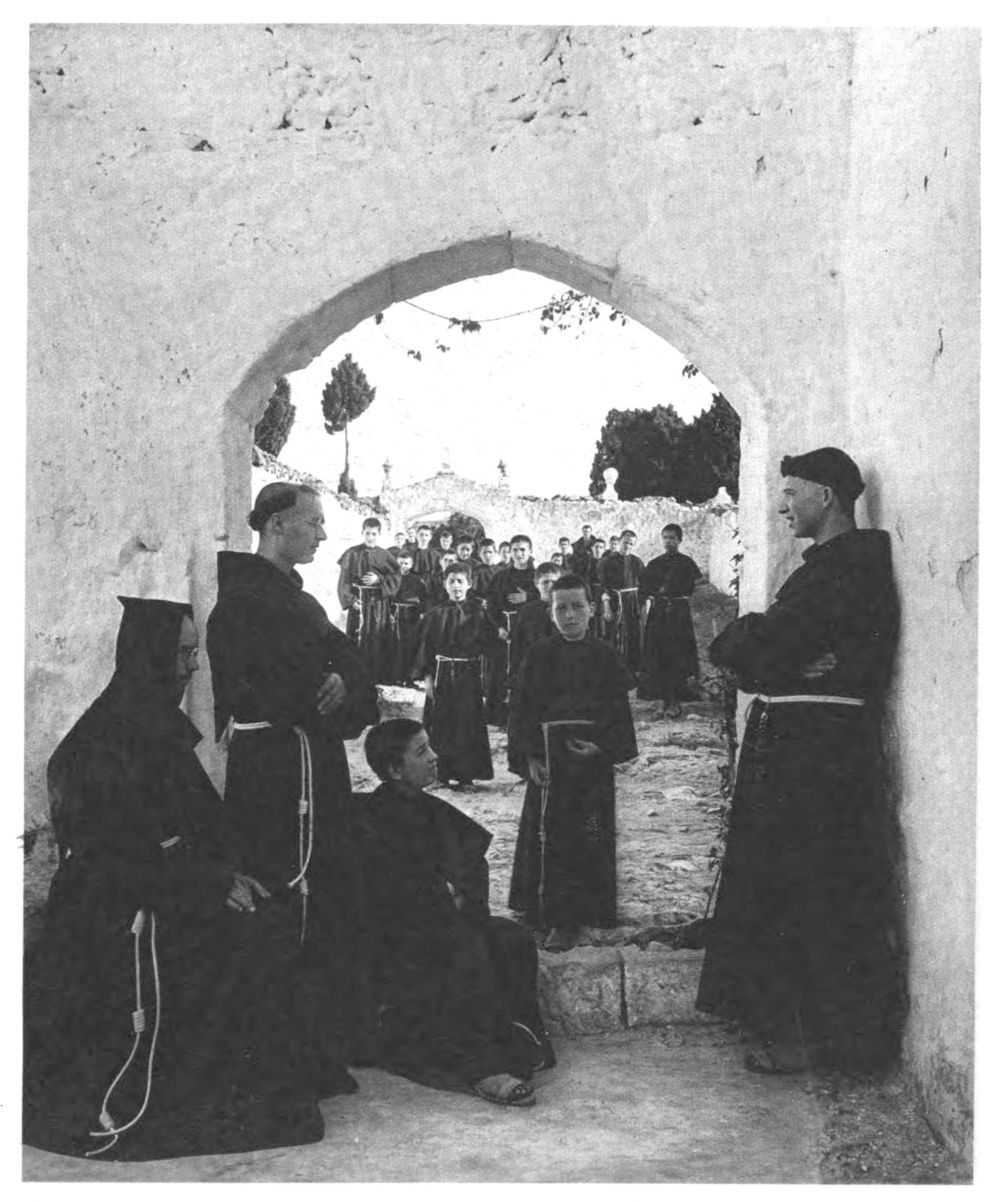

When the twenty or thirty bearers who carry the heavy dais on their shoulders, and who are hidden by drapery suspended round the frame, have rested enough, the signal to start is given by knocking on the front of the dais. A jerk, and the procession moves on a few paces. One religious body of brethren follows on the heels of the other. Each of them wear their own distinctive multi-coloured badges. Some have a blue pointed hat, others white, brown, violet or other coloured garments. Next to a father his ten-year old son in the same vestments is often seen, as well as the miniature penitent of fifteen in the procession.

The various brotherhoods are filled with an ardent ambition to outdo the others in the magnificence of their Pasos as the daises are called. The whole story of the Passion from Gethsemane to the burial of our Lord, is shown on them as they pass before our eyes.—Of course the clergy in full canonicals, as well as the town and state officials are also represented in the procession. At intervals, groups of Roman legionaries of Chris{xiii}t’s day appear, then angels, and St. Veronica carrying the kerchief. Interspersed bands bray and flourish the same march without cess.

Each brotherhood in the procession is cerimoniously received by the chief authority of the town in Constitution Square which looks like a huge theatre auditorium. It is filled with rows of chairs of which not a single one is empty. The surrounding balconies are a sea of heads.

Hour by hour passes. Night falls. And now hundreds of wax-candles blaze forth on the daises, and each penitent carries a gigantic taper in his hand. Thus this endless and mysterious procession of lights moves on to the cathedral, passes through its magnificent nave, and out again through the other doors into the streets.

The cathedral has opened its treasure-house for the “Semana santa” and displayed all its pomp. The candles of the gigantic bronze candelabrum (the renowned Tenebrario) as well as on the altar the sacred wax-candle weighing several hundredweight. A huge sepulchre has been erected to the glory of Christ, in which the Holy of Holies is kept during Passion week. Hundreds of lamps and candles illuminate the golden-white four-storey edifice, which is over 30 metres high, and flooded with a wondrous glowing halo.

The celebrated miserere of Eslava is performed in the cathedral on the night of Good Friday. But, alas! it is impossible to enjoy the sacred tunes owing to the general noisy inattention around. Weary forms are sitting on the steps of the chapels and around the grave of Columbus. Here a mother is suckling her infant, there an animate heap of rags is wrapt in sleep, and all the while there is a continual pushing and elbowing to get to the front.

However we must not judge of all this in the light of serious northern church festivals. This would only lead us to drawing both severe and wrong conclusions. Perhaps this manner may be an historical development. Has not our Teutonic Christianity also wedded itself to much that is ancient heathenism? For instance Christmas and the winter solstice festival. Much that is Moorish obtains in Spain to this day. Perhaps even—unconsciously—the conception of the purpose of a place of worship. Was not the mosque often enough a secular place of meeting for the Moslems, and at the same time a university? However, enough of conjectures. It is a fact that the worship of the Lord and the Virgin Mary is for the Spaniard a service of love. Whether the occasion be Trinity or Passion week, it is one of joyful praise of Heaven.

I shall always remember one quiet hour permeated with the holy spirit of Easter among these joyful and yet pious Easter days.—I had mounted the Giralda, that jewel of erstwhile Moorish minaret architecture, the cathedral tower. At my feet lay the white sea of houses. The town was bathed in sunshine. The beautiful blue dome of heaven spread its mighty arch over the holiday-making land as though protecting and blessing it. The faint music of the mass far below was wafted up to me, when suddenly a booming vibration filled the air, and all the tower bells, which had been silent so long, peeled out across the sunlit country: Christ is arisen! The sister bells of all the other towers echoed the message across the spring clad country.

O

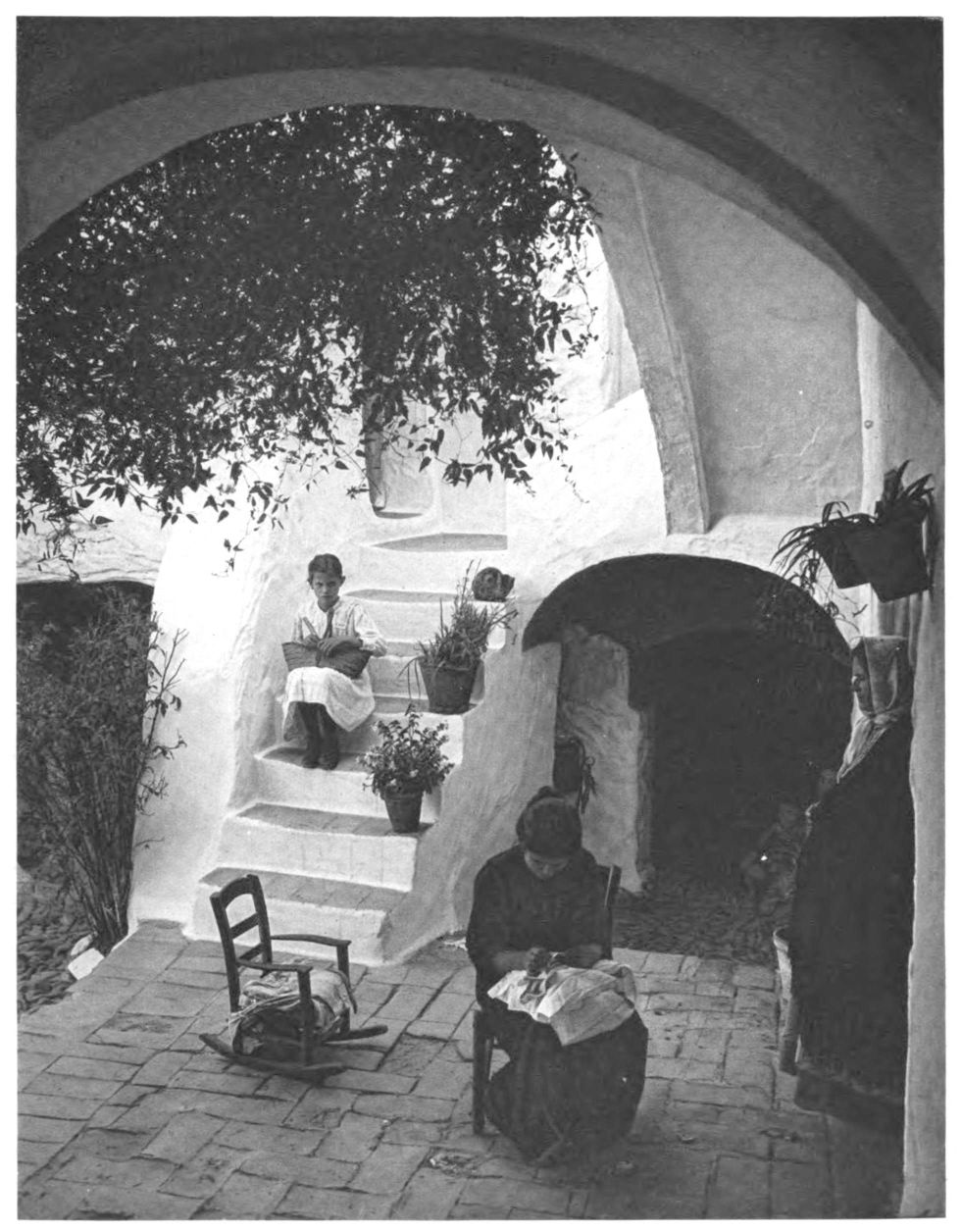

The Patio (40, 42-49). It is a favourite expression to call Seville the town of bright court-yards. Those court-yards which light and fill the house with sunshine. The Sevillian house, or rather the Andalusian house, is not a building such as our houses, fronting on the street, but one that fronts to an inner court, turning its back on the street. The outsides of the houses are bare of ornament, almost windowless; a secret to the passer-by. All their beauty is displayed yardwards. There wealth obtains in all{xiv} its pomp, and poverty unfolds its modest ornaments. The narrow passage—the Zaguan—leading from the street to the court is closed by a railed gate. The gallery—to which access is gained by steps leading from the court—is supported by columns. The rooms of the upper stories lead to the gallery. To cool the air there is a fountain in the middle of the court surrounded by palms, araucarias, laurels, orange-trees, oleanders and flowers in pots. The walls are covered with multi-coloured tiles. Against them brightly up-holstered furniture, chairs, and sometimes even a piano; the inevitable guitar is in a corner. Climbing plants festoon the court.

Practically this is the centre of the whole family life. Friends are received here, hours passed in argument, singing, music and dancing—whether in company or alone, dreaming away the hours, listening to the plashing of the fountain, it is in the court—the soul of the house—that most time is spent.

O

There is nothing commonplace about Spanish houses. They still retain their peculiarity impressed on them by the patina of age. Many have tumbled down under the burden of years. Many are dead; but they “died in beauty”. The period of their prosperity still lingers on in the churches and ornate façades of deserted squares.

Toledo is the most Spanish of towns. It was once the heart of the country, pulsating with the great rhythm of epic history. But its heart no longer beats.

Resting on steep granite hills above the deep Tajo valley stands the yellow-grey heap of houses as though rooted in the rocks. Two gigantic bridges span the river. Narrow alleys lead up hill and down dale; many-cornered and dark. The whole town seems in a fighting mood. Huge gateways and towers, the houses fort-like, the doors studded with heavy nails. Indeed, there is hardly a town that has seen so many battles rounds its walls. Spain’s history has passed over it with heavy steps. And to-day? Rent walls, ruin and silence: the town the accumulated wreckage of a thousand years (139-148).

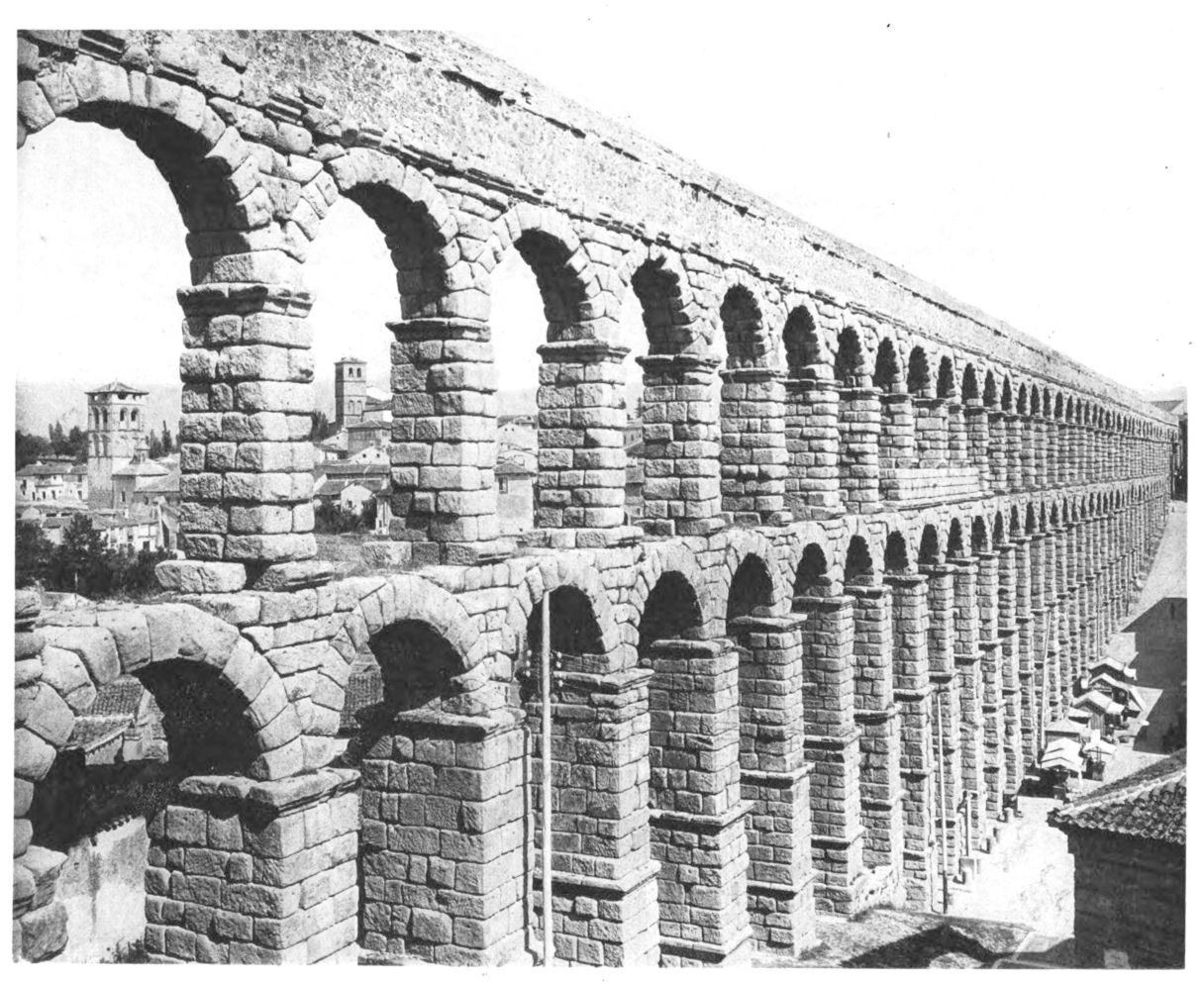

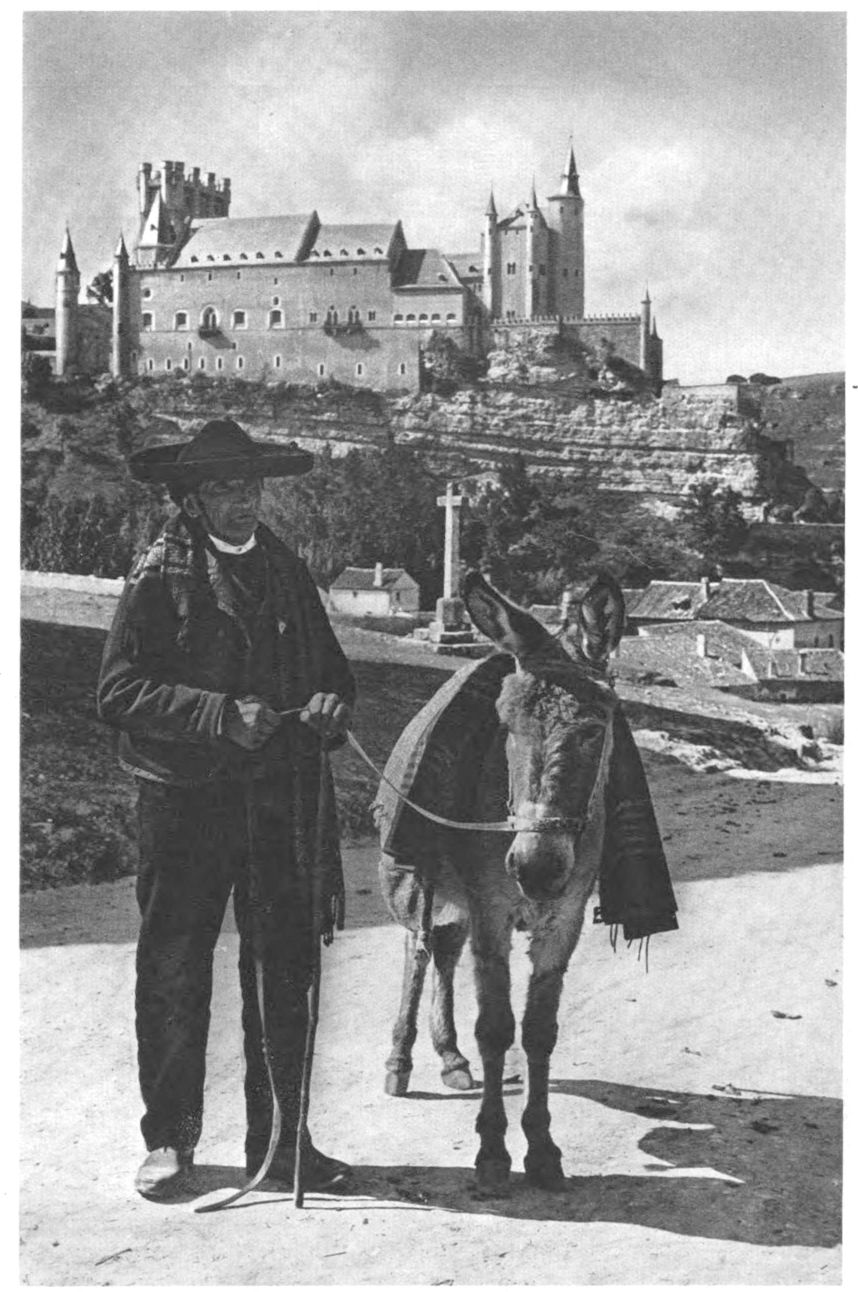

Segovia, Toledo’s sister city is situated similarly on rocks arising abruptly from the plain. It is dominated by a great cathedral tower, and guarded by the well-proportioned Alcazar which stands forth like a fairy castle. A miraculous building, erected one would say to brave eternity in the days when Christ was born. But otherwise Segovia is different to Toledo. It is the Nuremberg of Spain, gay in its leafy setting (157-164).

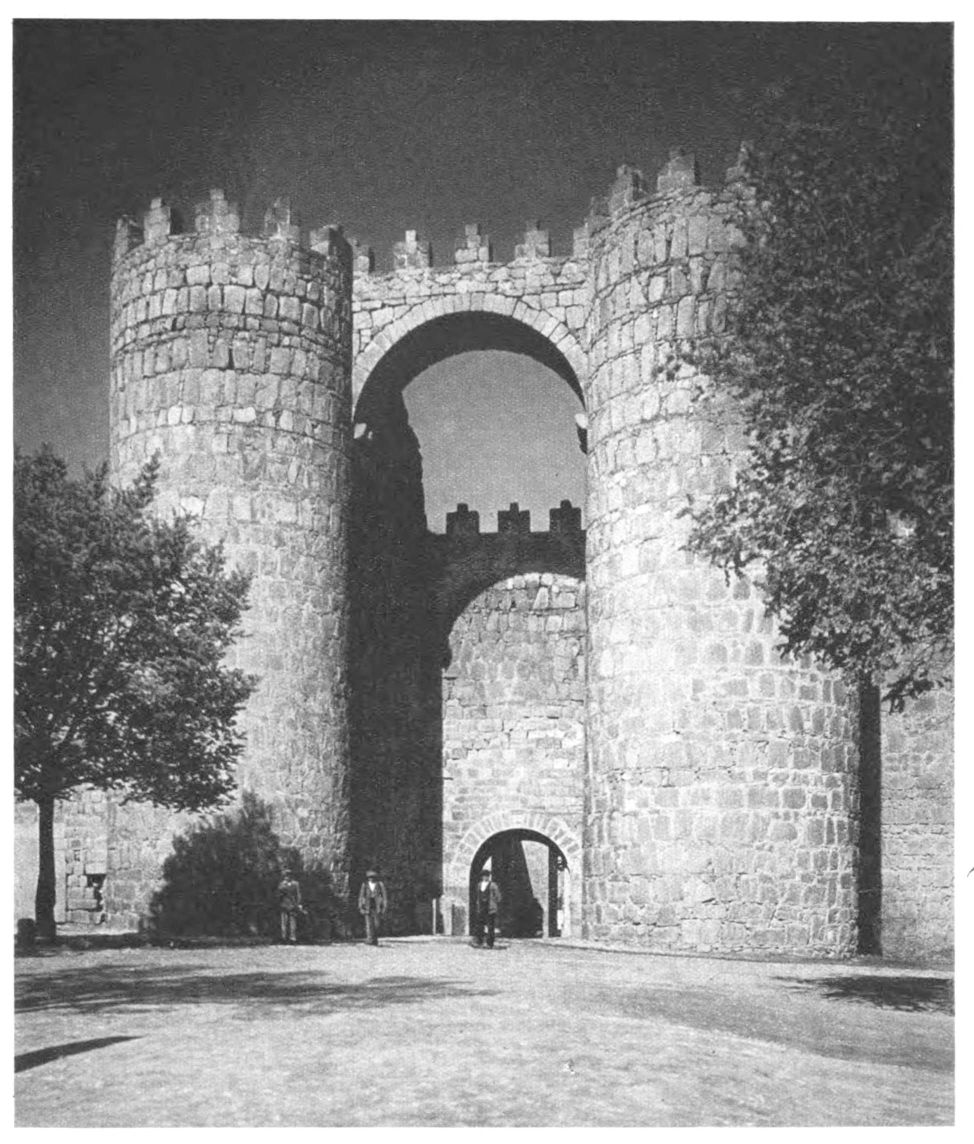

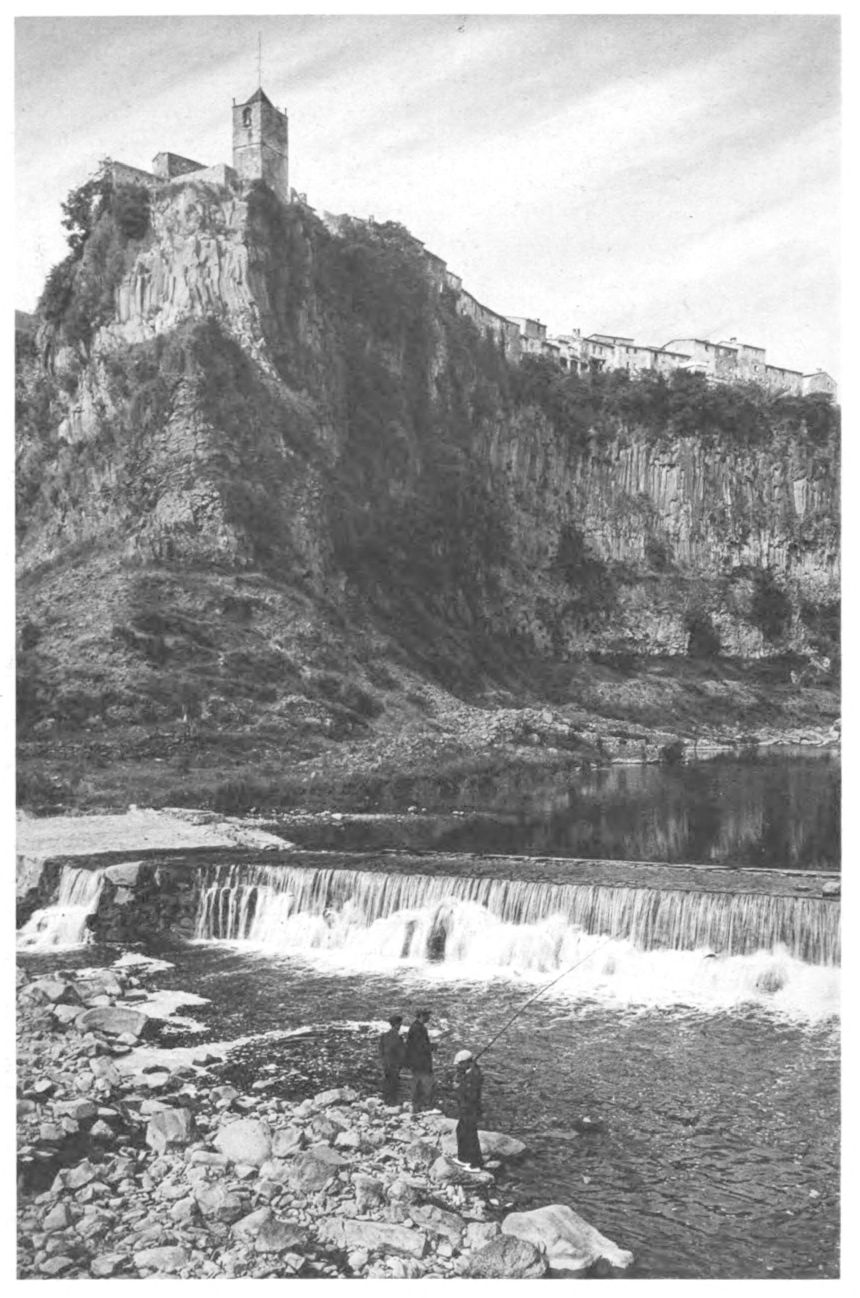

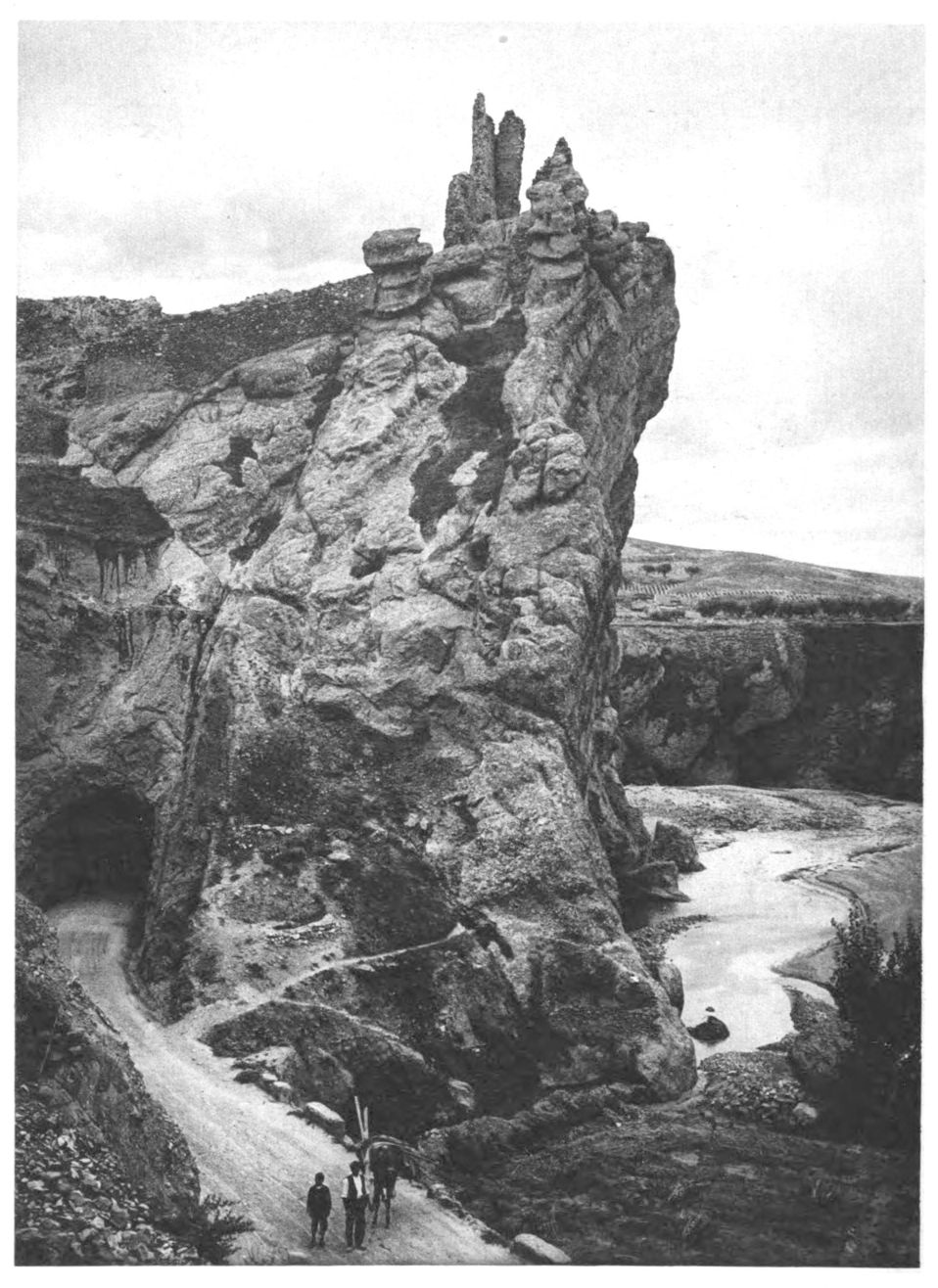

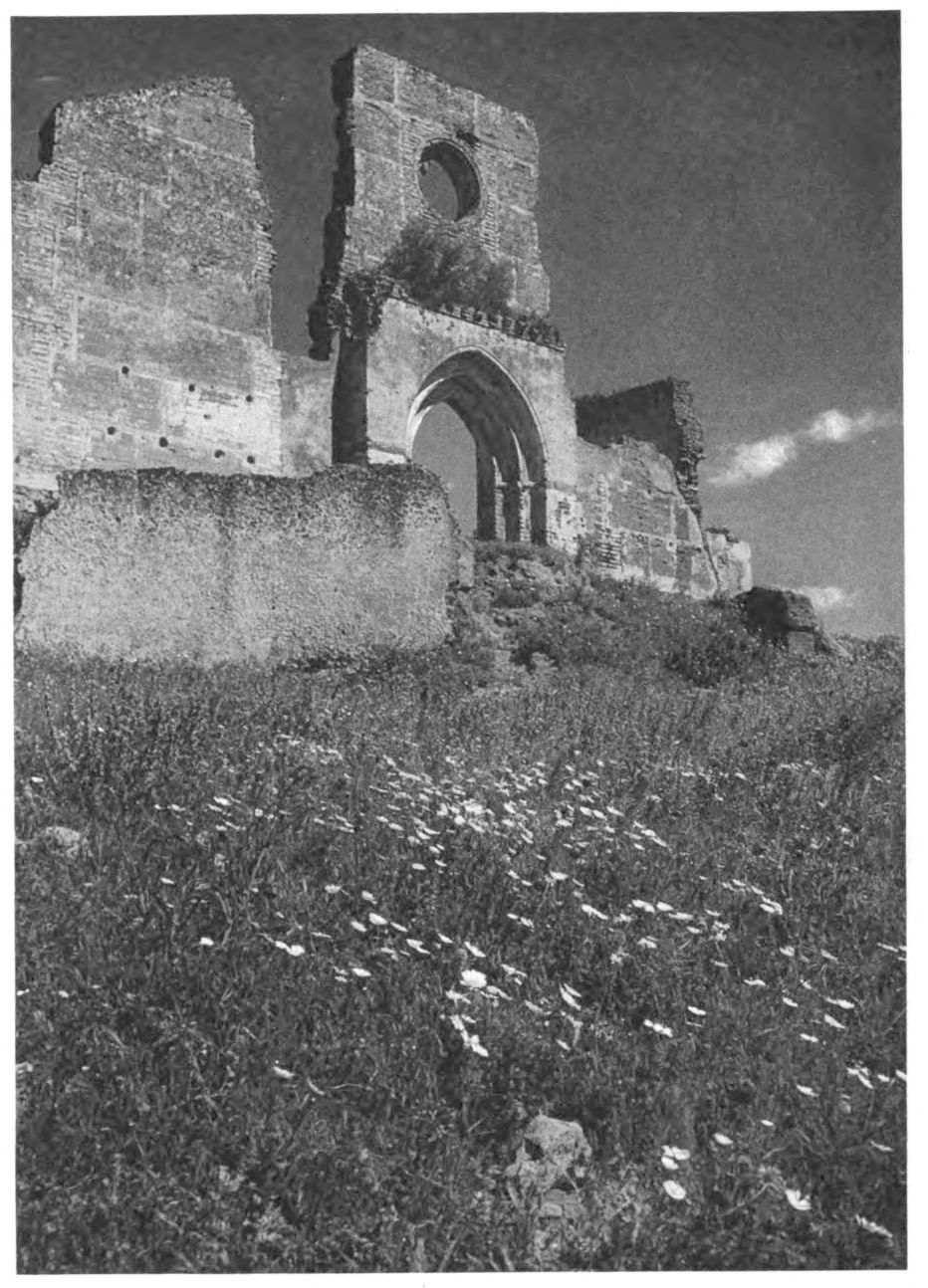

There are other brave old companions-in-arms of these two veterans, dating from ancient war days: circumvallated Avila (165-169), Cuenca and Albarracin with their swallow-nest houses clinging to lofty crags (120, 121, 192-194), Daroca protected by two mountains over which the whole of the battlemented walls have climbed (195-197), Alquezar in the Pyrenees, the northern outpost of the Moors in Spain (210-212), Sigüenza, Jerica, Trujillo, Caceres, Niebla, Carmona, Martos, Antequera, and many bold castillos.

Ronda is the most boldly situated town lying on a high plateau encircled by a wide mountain arena (62, 63). Running through the rocky plateau is a huge crevice which looks as though it had been split in rage by the mighty fists of giants.

The streams thunder down in all their wild force over the boulders, hammer threateningly against the rocky walls, break into scintillating spray, rush round in whirlpools, and hurry on their course. And in close proximity to all this turmoil, the rocky walls stand unshaken in their immobility against the sky-line, an emblem of eternity cast in stone by the hand of God. The rainbow in the spray has been copied by man in the shape of a bridge high over the abyss joining the rocky heights upon which the town stands.{xv}

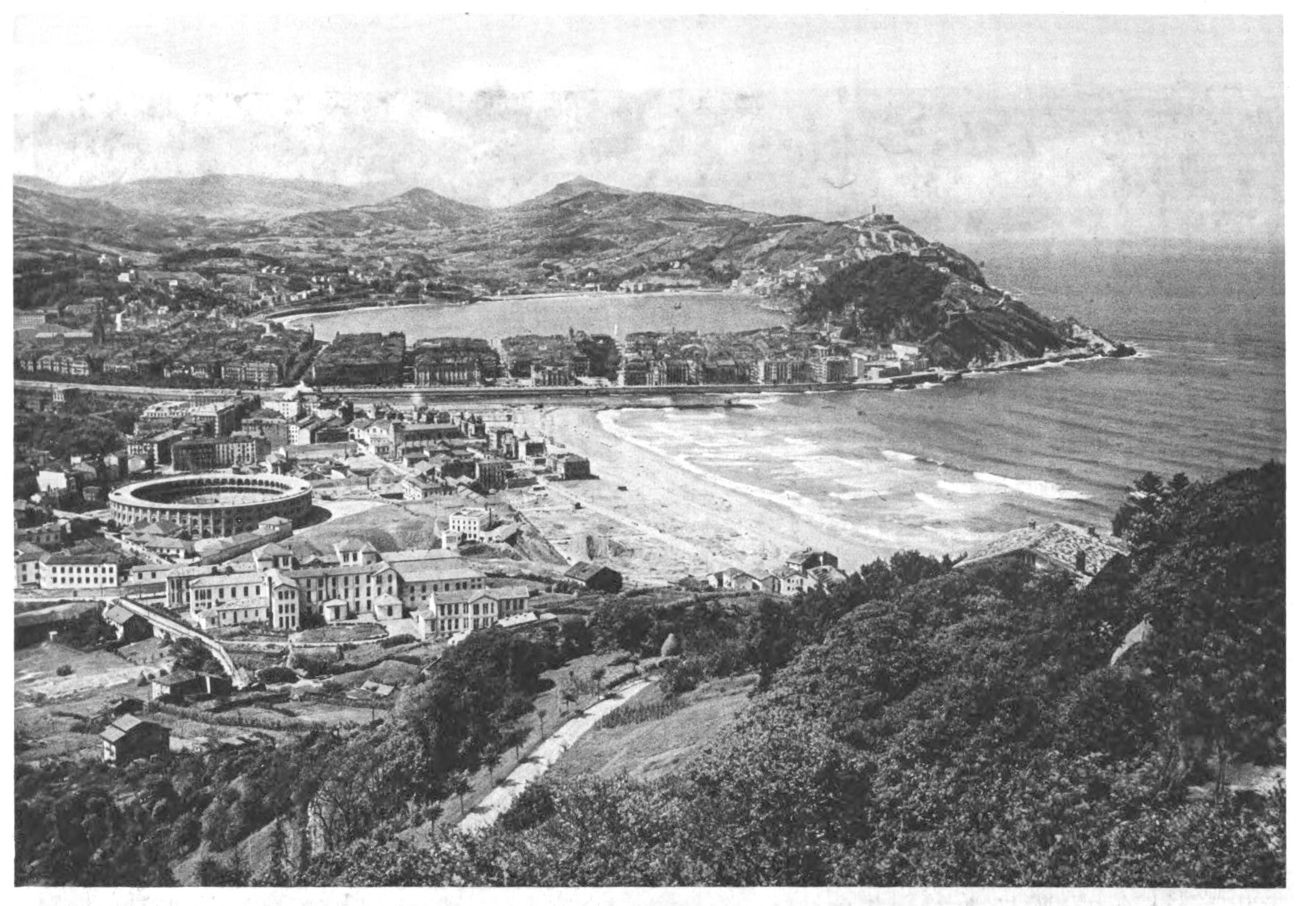

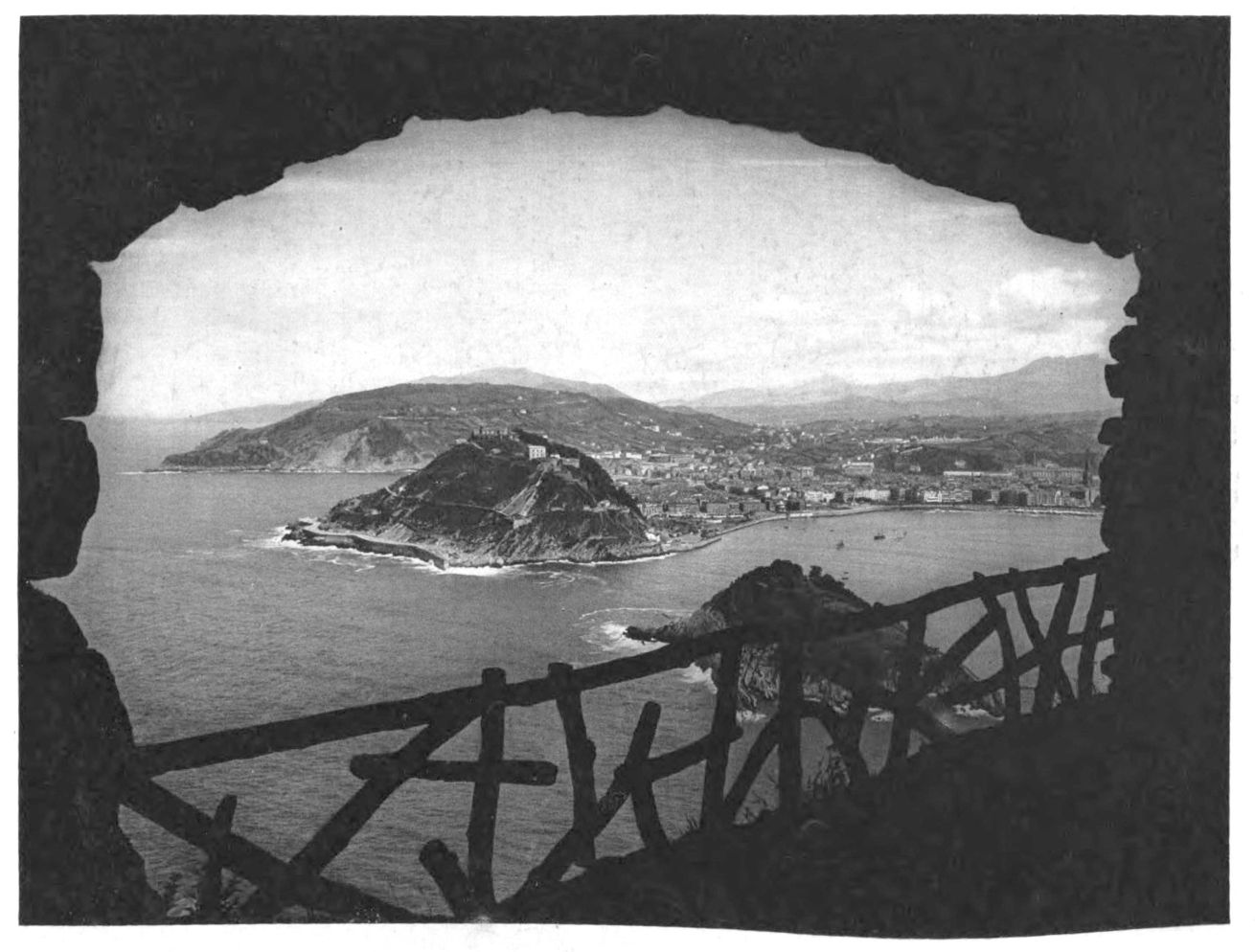

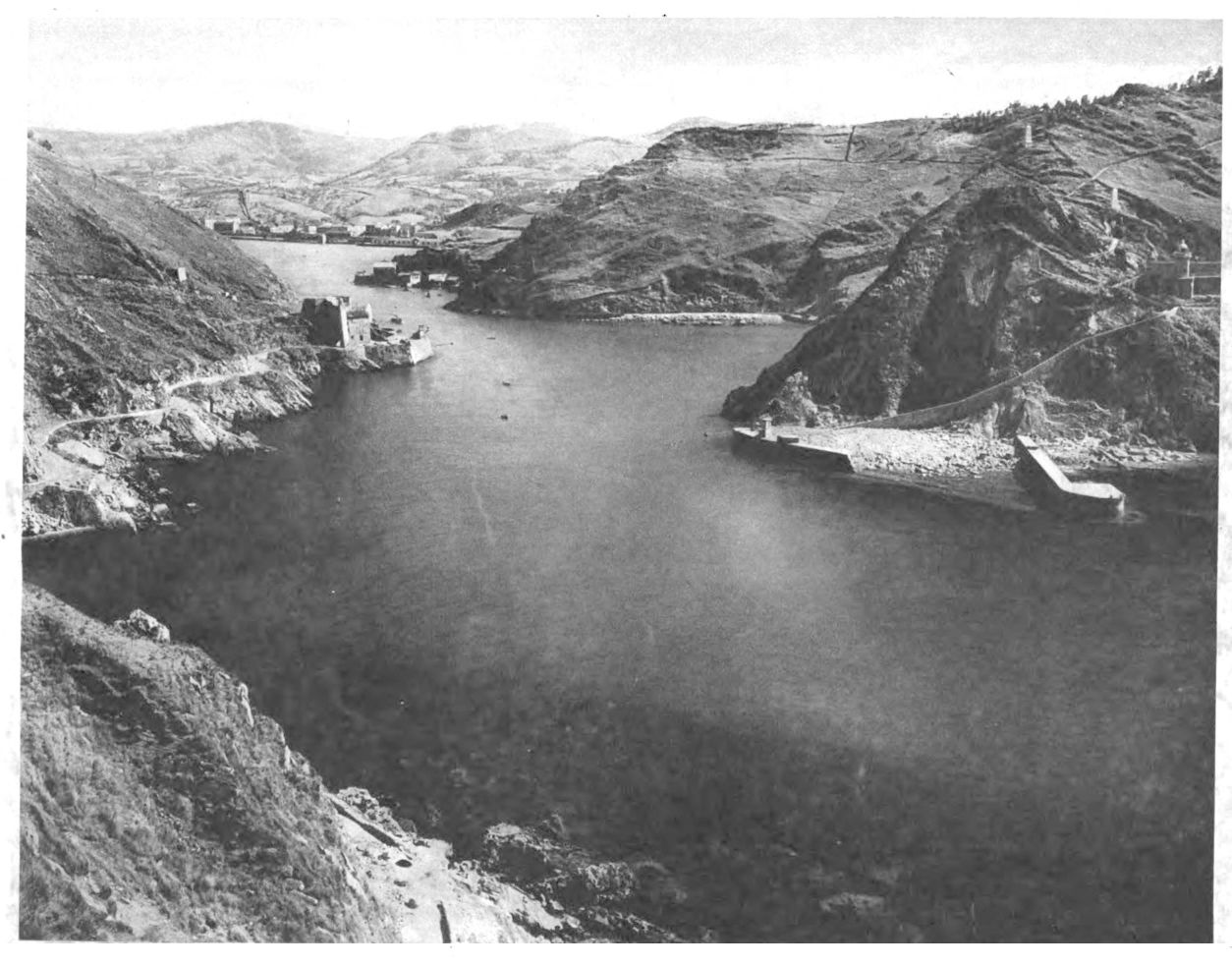

Let us pass from these stubborn old battle towns to a more smiling scene: San Sebastian (286-290) known throughout the world for its incomparably beautiful situation on the sea. The view from Monte Ulia, a mountain guarding the entrance to this paradise, is wonderful beyond words. Here nature has modelled and painted a masterpiece. The sea hugs the land in two gracefully curved bays and catches the beauties of the town in the reflection of its waters.

O

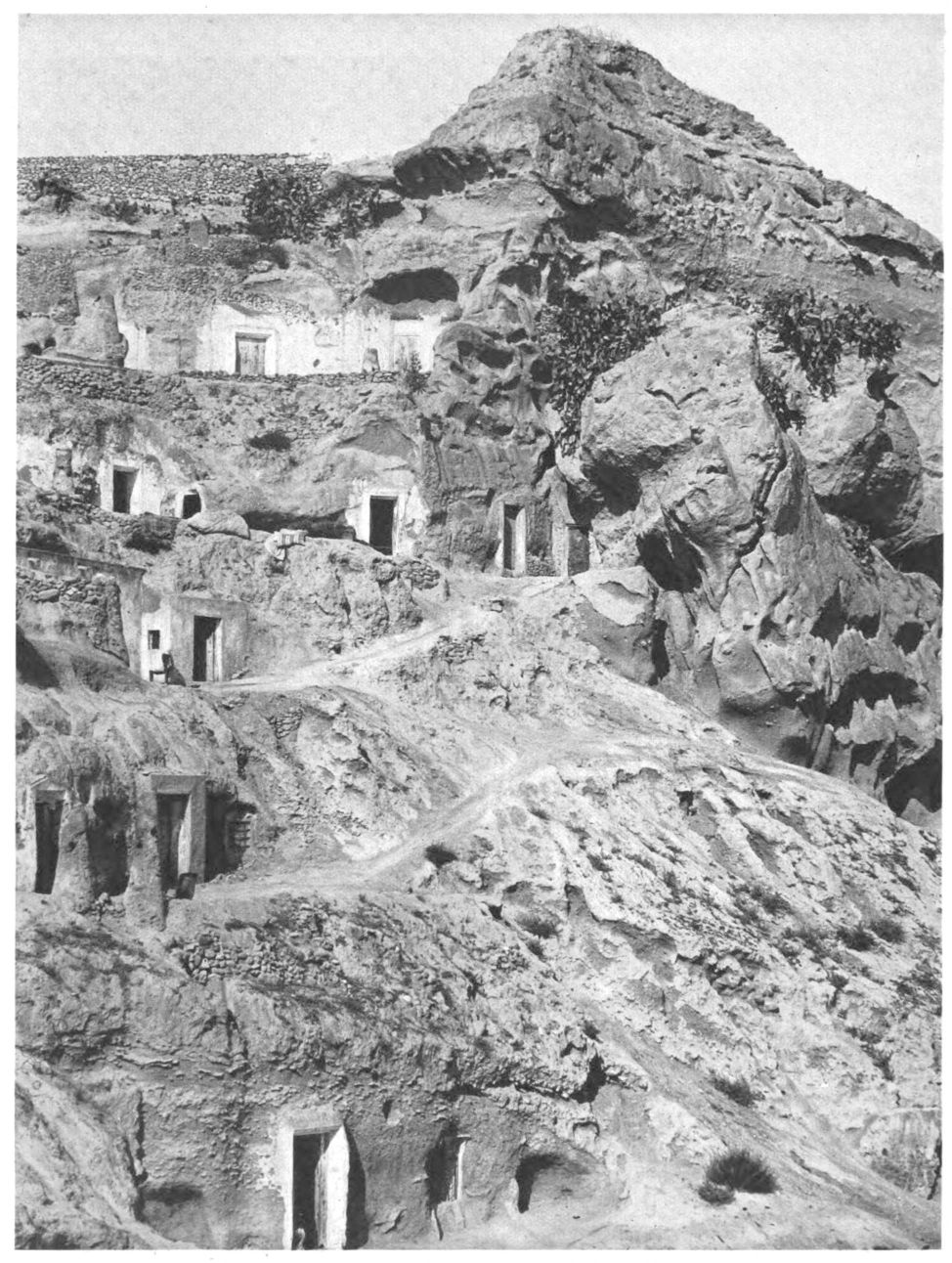

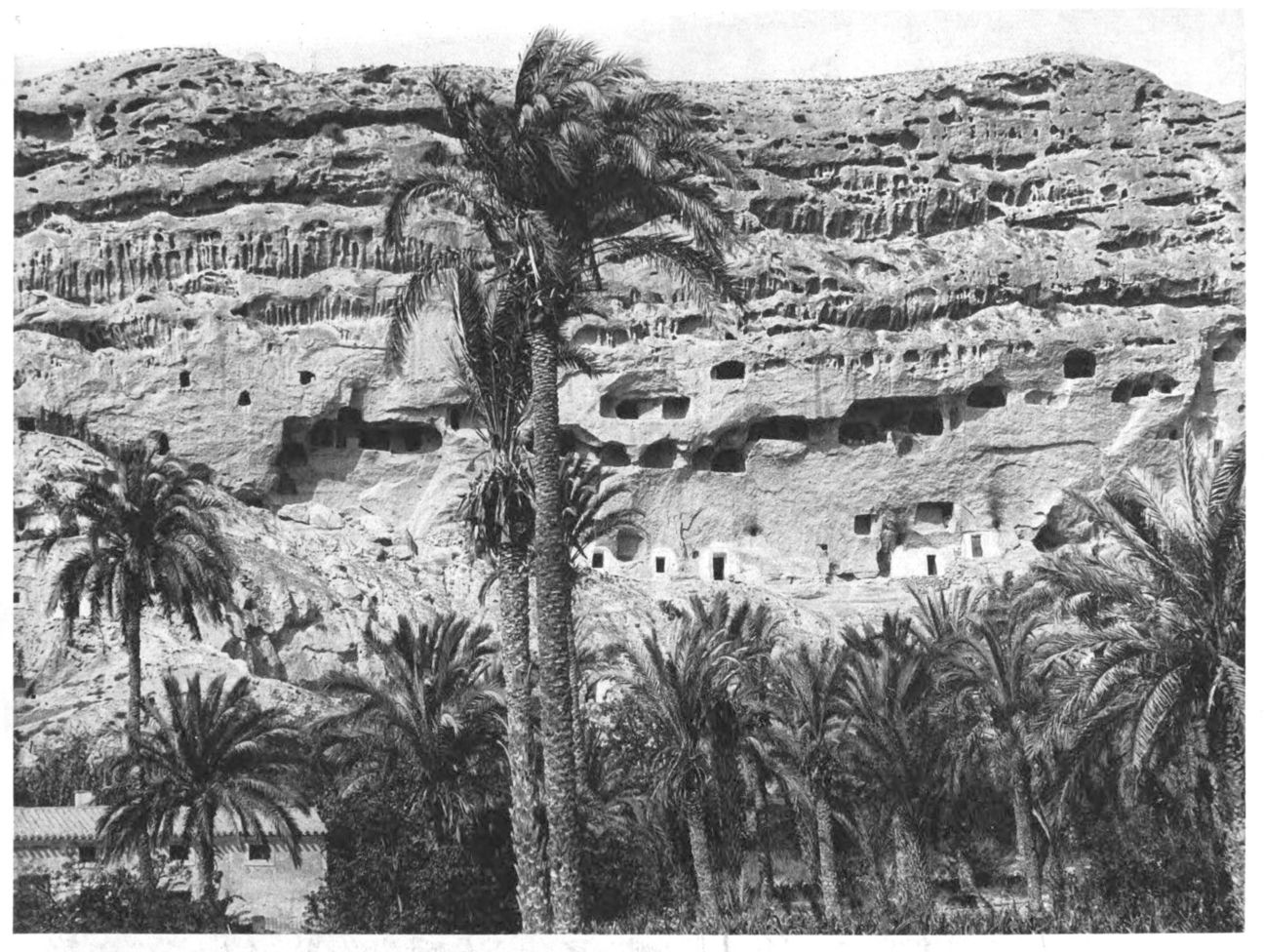

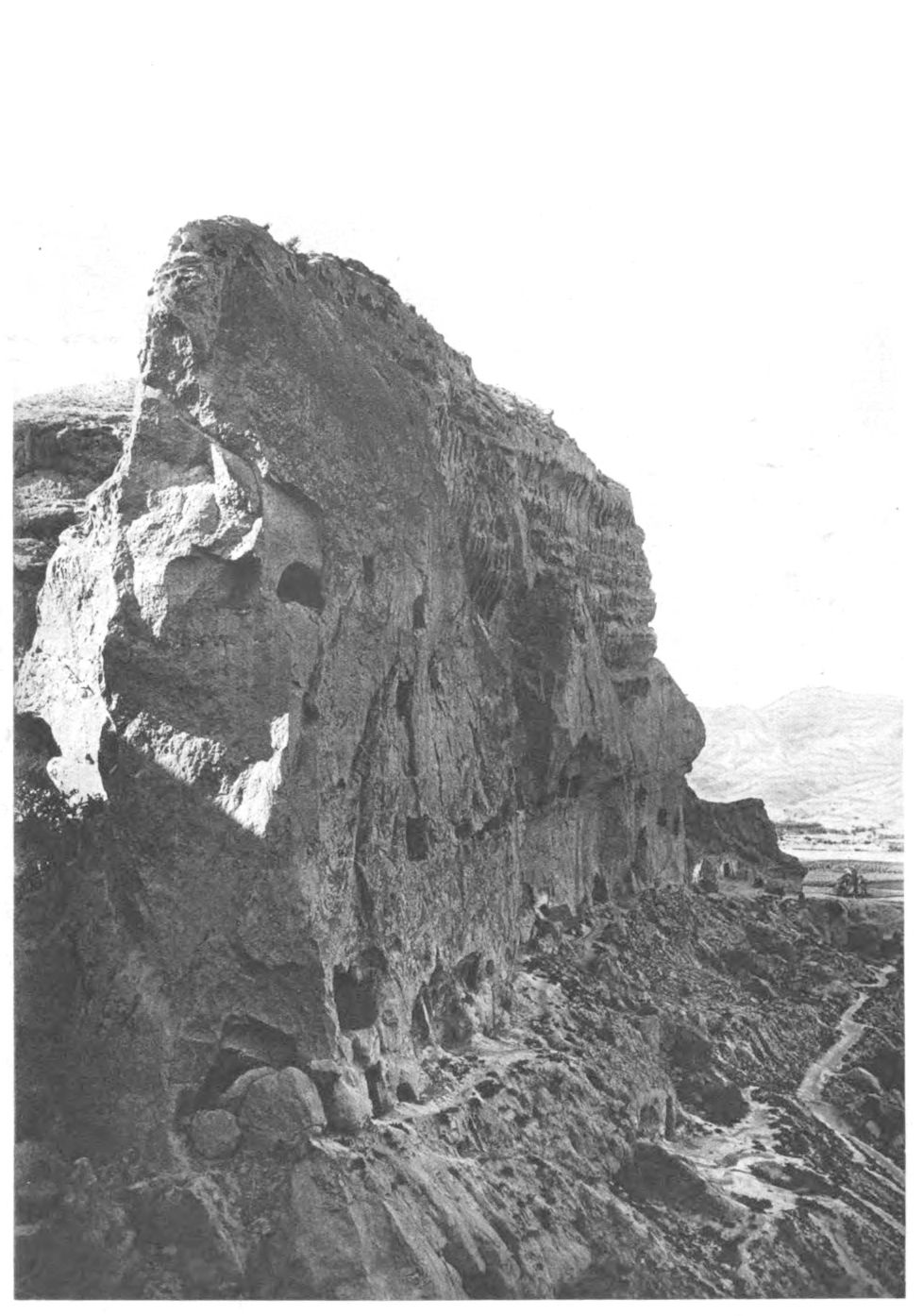

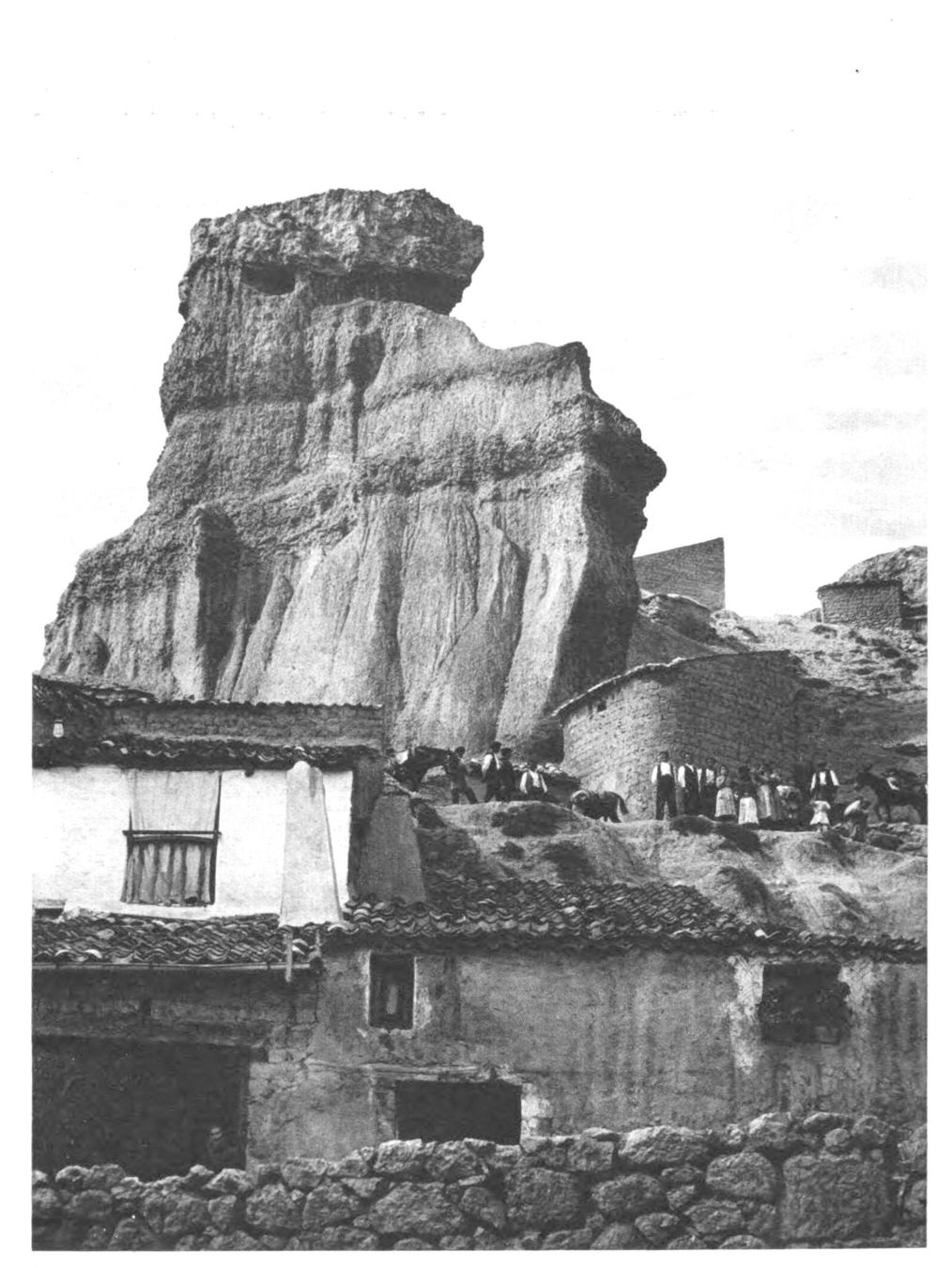

Cave-dwellings and the simple life.—This time I decided to leave the destination of my wanderings to chance. I could have chosen no better guide. I set out long before the dew was dry, or the sun had risen. The palm trees were just beginning to shake themselves in the early breeze when I approached a strange rocky landscape. Dark holes in the rock stared at me like dead eyes. But nevertheless life was hidden there. Human forms stepped out of the holes to greet the morn.

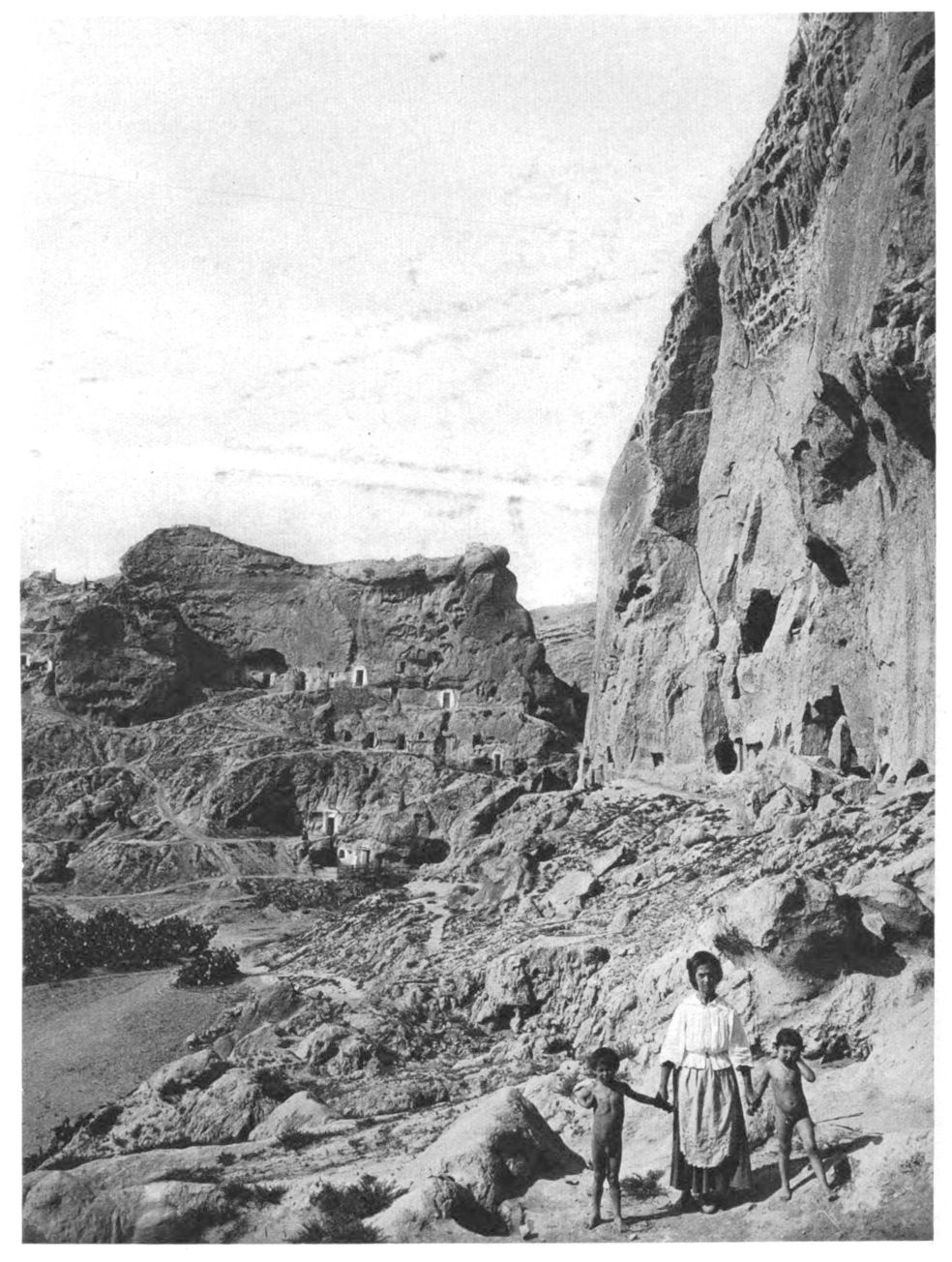

What I saw was a towering rock wall with hundreds of cave-dwellings next to each other and over each other. Some of them were even five storeys high and approached from the outside (92). Where the rocks were too steep, the approaches had been dug from the inside, and upper storeys created with outlook holes and loggias high up in the rocks. Tunnels had been cut in the soft stone to get from one rock valley to the other.

The children were running about in the costume God had given them. But it is not to be supposed that they were troglodytes, and as unaware of culture as those who lived in the ice period. High on the rocks you can read in large black letters on a white background “El Retiro”.

Every Spaniard knows, at least by name, Madrid’s beautiful park the Retiro. For this reason it seems somewhat of a joke to suddenly come across the name in such a spot far up on the rocks. El Retiro, like Sanssouci, means solitude, retreat, place of rest. An enterprising hotel-keeper has levelled his portion of rocks into roof-terraces where the favourite gossip hour (tertulla) is spent, skittles played, and merry dances performed. Hence the alluring words on the wall for the benefit of passers-by. On another rock is graven the brief significant inscription: “Dios, Pan y Cultura” (God, Bread, and Culture. 92-95.

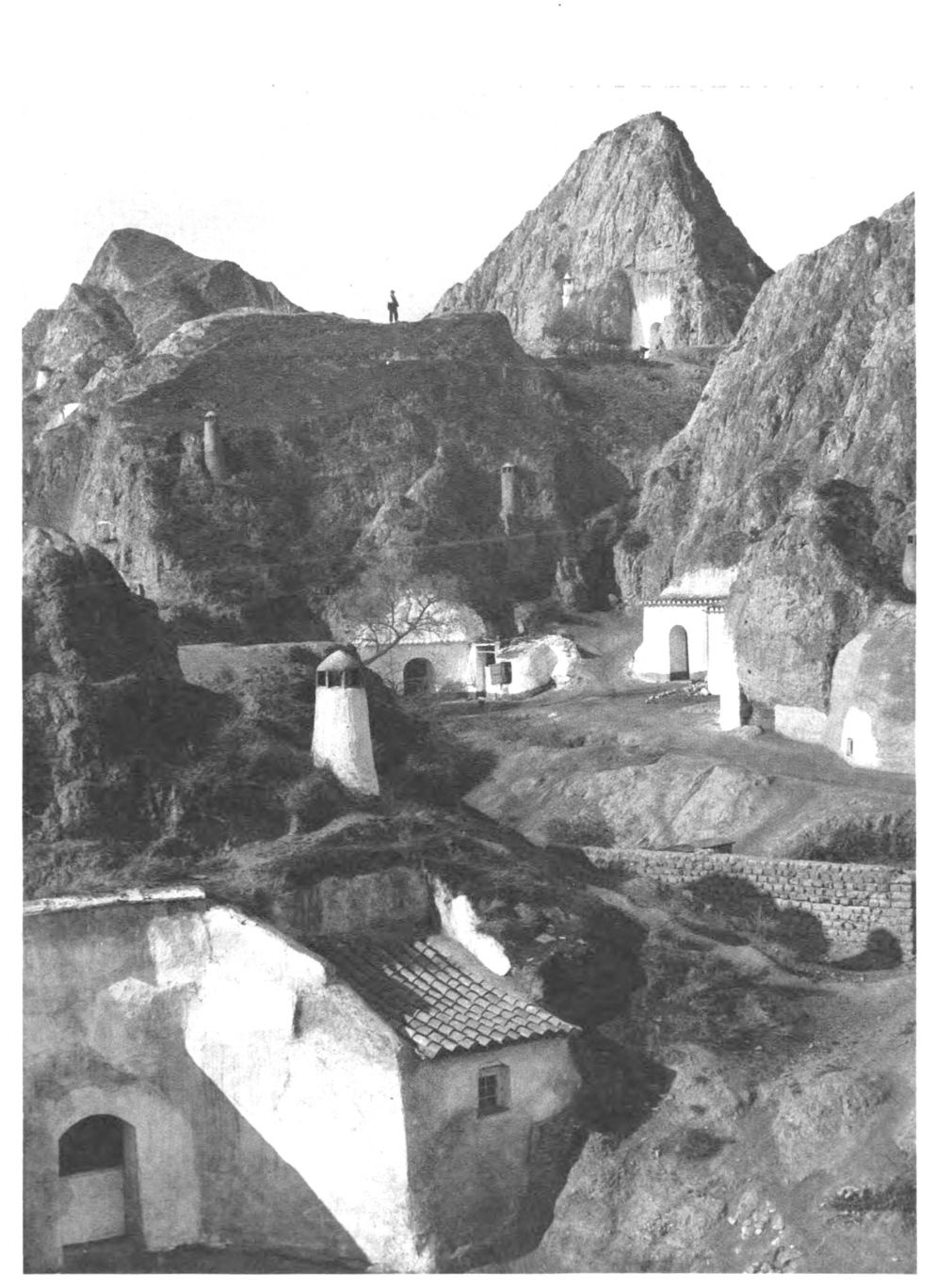

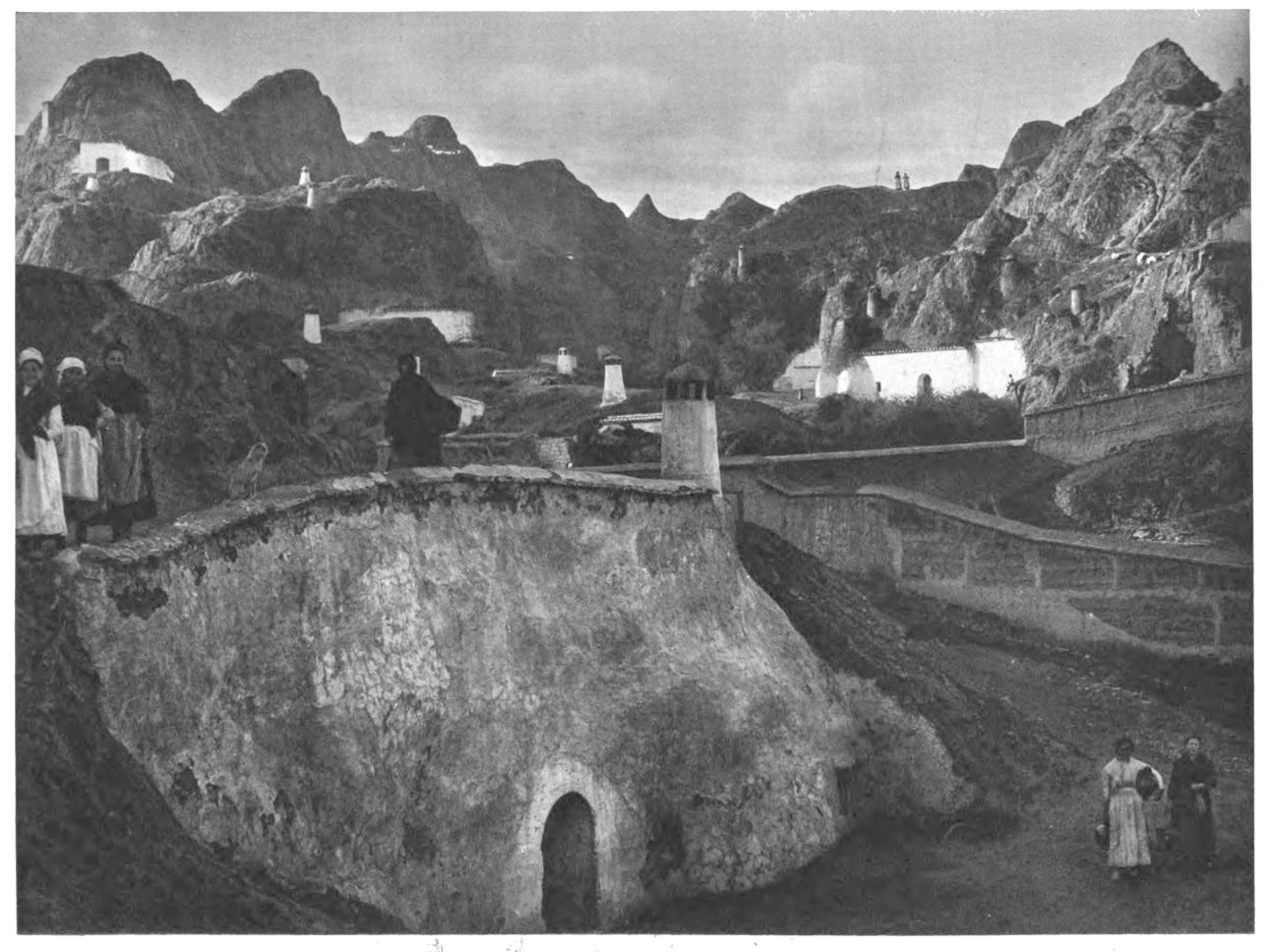

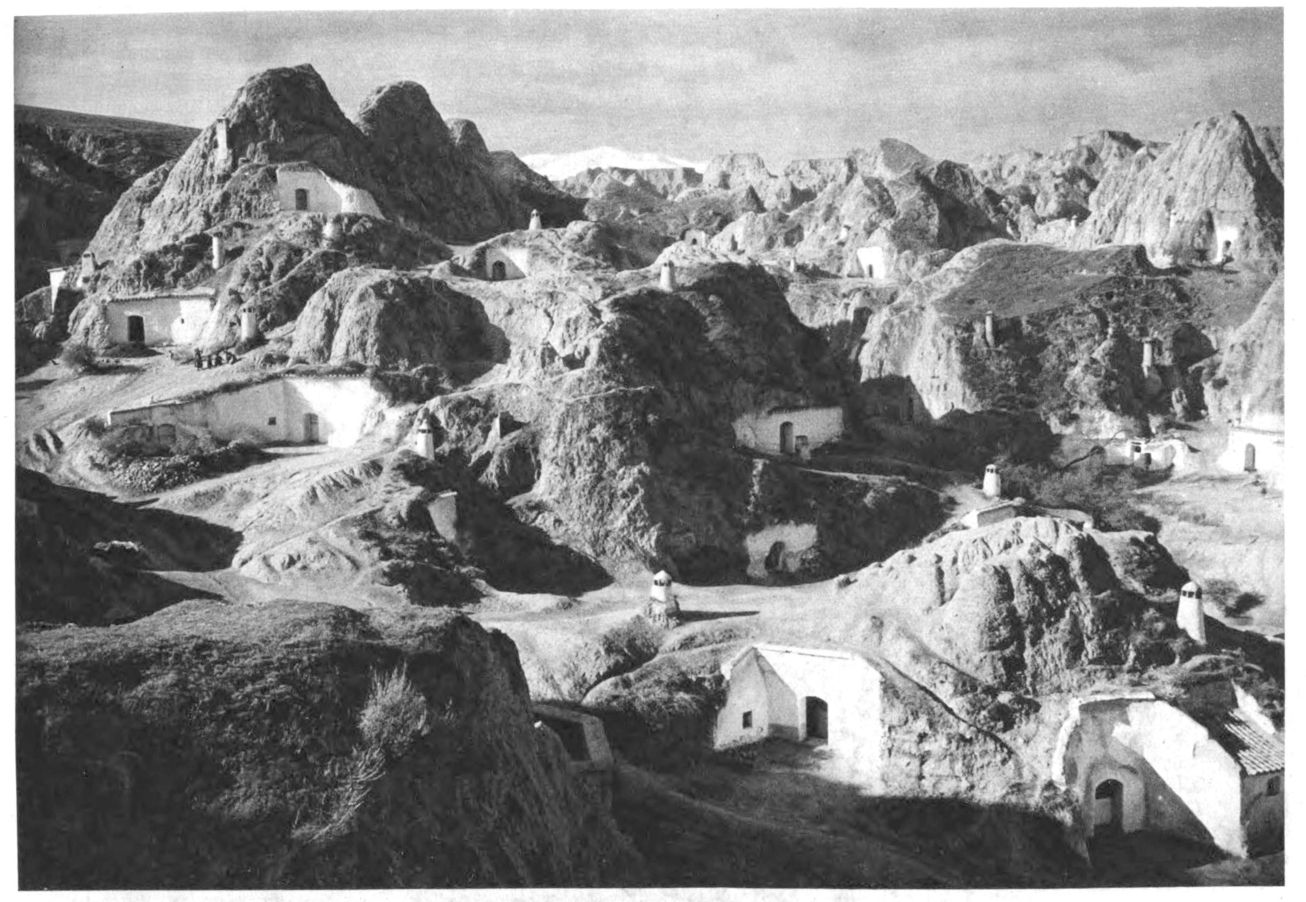

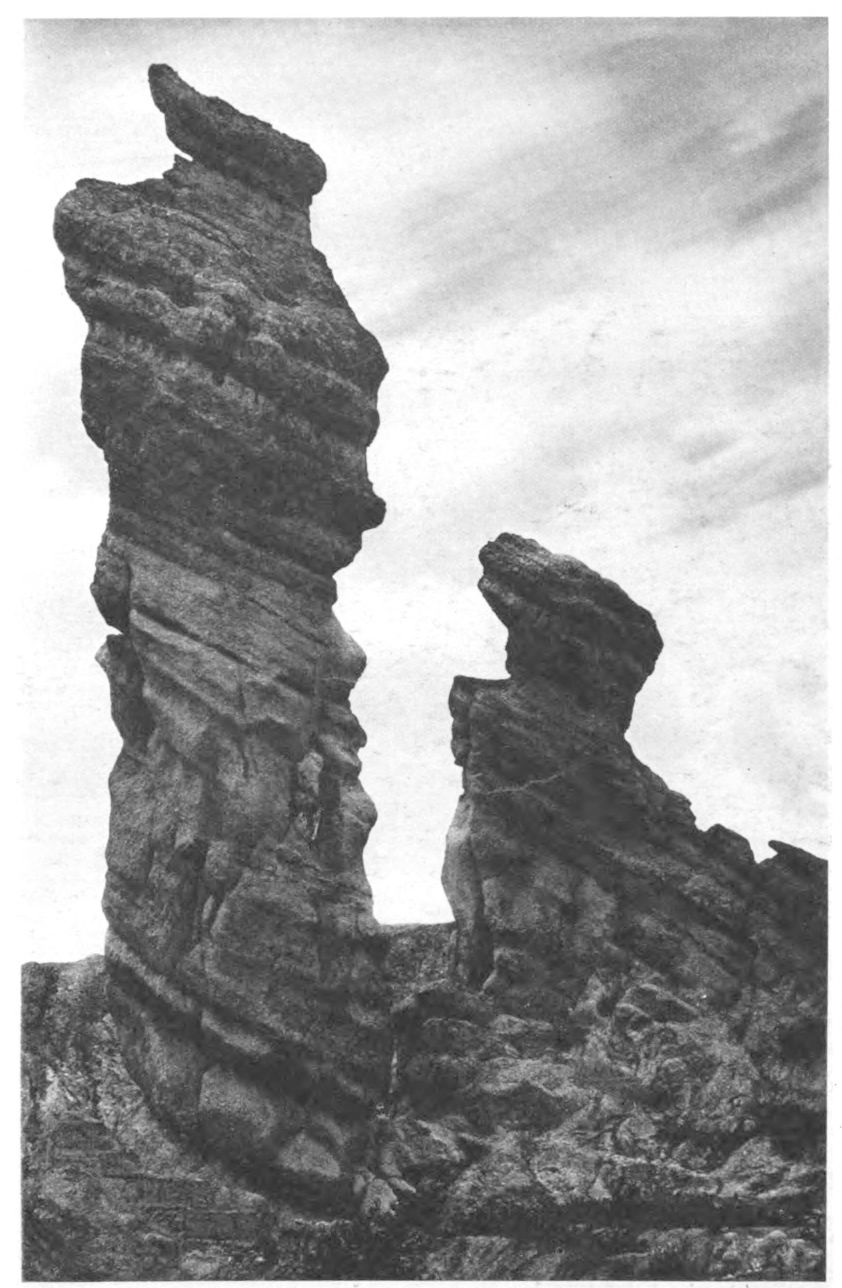

During the course of another stroll I was again equally surprised. I saw smoke arising in the distance from ground that looked like fantastic mountain erosions. Surely this was not the site of volcanic activity? Indeed this was out of the question. And on drawing nigh I discerned human figures moving among the columns of smoke. I then saw to my astonishment that little smoking towers—not unlike champagne corks in shape—were chimneys projecting out of the ground. I had again strayed among cave-dwellers. What Homeric primitiveness was there! The valleys are the streets, the mountain sides the fronts of the houses, the pinnacles villas. Front gardens are once and a while supplied by giant cacti and spiky agaves. My wanderings in this interesting world-forgotten primitive spot lasted for hours as I passed up and down the so-called streets (96-99).

My greetings were met with a cheerful response, and I was invited to enter a cool cave, provided with a drink of fresh water, and shown the treasures of the modest household: the bed on the ground, the hearth with a copper kettle, the earthenware pitcher, the stool, the oil-lamp and the image of the patron saint.

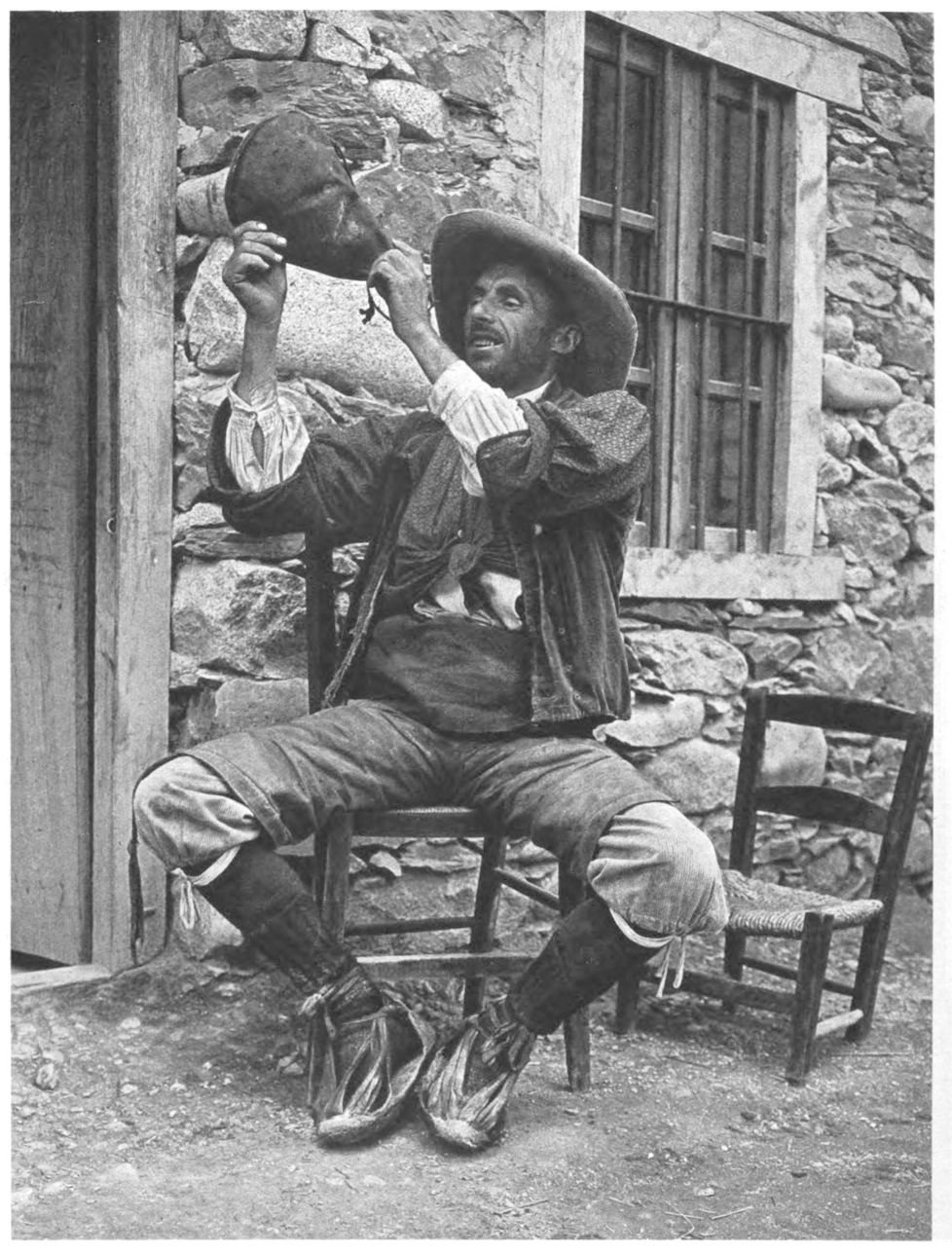

“Now as to work?” I asked. “Well we don’t do too much in that way. We cultivate what we need over there where the river runs. We make bricks for the towns where the people live in houses.”—Truly a picture of an enviable state of modest{xvi} requirements. There are still those who are satisfied with the tub of Diogenes. Indeed you may find many such all over Spain. I remember when at a little railway station finding only a lad deep in his after-dinner nap. For the rest, there was no one else to take my luggage, so I woke him up and asked him to help me. He stretched himself in all the bliss of laziness, took a couple of coppers out of his pocket, and showing them to me said: “I’ve earned 25 centimos to-day already; that’s all I need,” turned over, and went to sleep again. I continued on my way recalling the words of the Indian philosopher: “He who is without wants is nearest to God.”

There is no cause to shrug one’s shoulders. Diligence and happiness are but relative conceptions. And just the poorest in Spain understand the art of doing nothing combined with extracting joy from next to nothing. They need a little shade in summer, and the sunshine in winter; a piece of bread, a tomato, a drop of wine. The whole earth with the sky for a roof is their bed-room; the highroad their field of labour. There is no master they would exchange positions with; they are their own masters; masters of their own time—verily a great possession this. Why then should they not spend it generously? “He whom God helps will go further than he who rises betimes” runs a Spanish proverb. And the Bible tells us: “Behold the fowls of the air: for they sow not, neither do they reap, nor gather into barns; yet your heavenly Father feedeth them.”

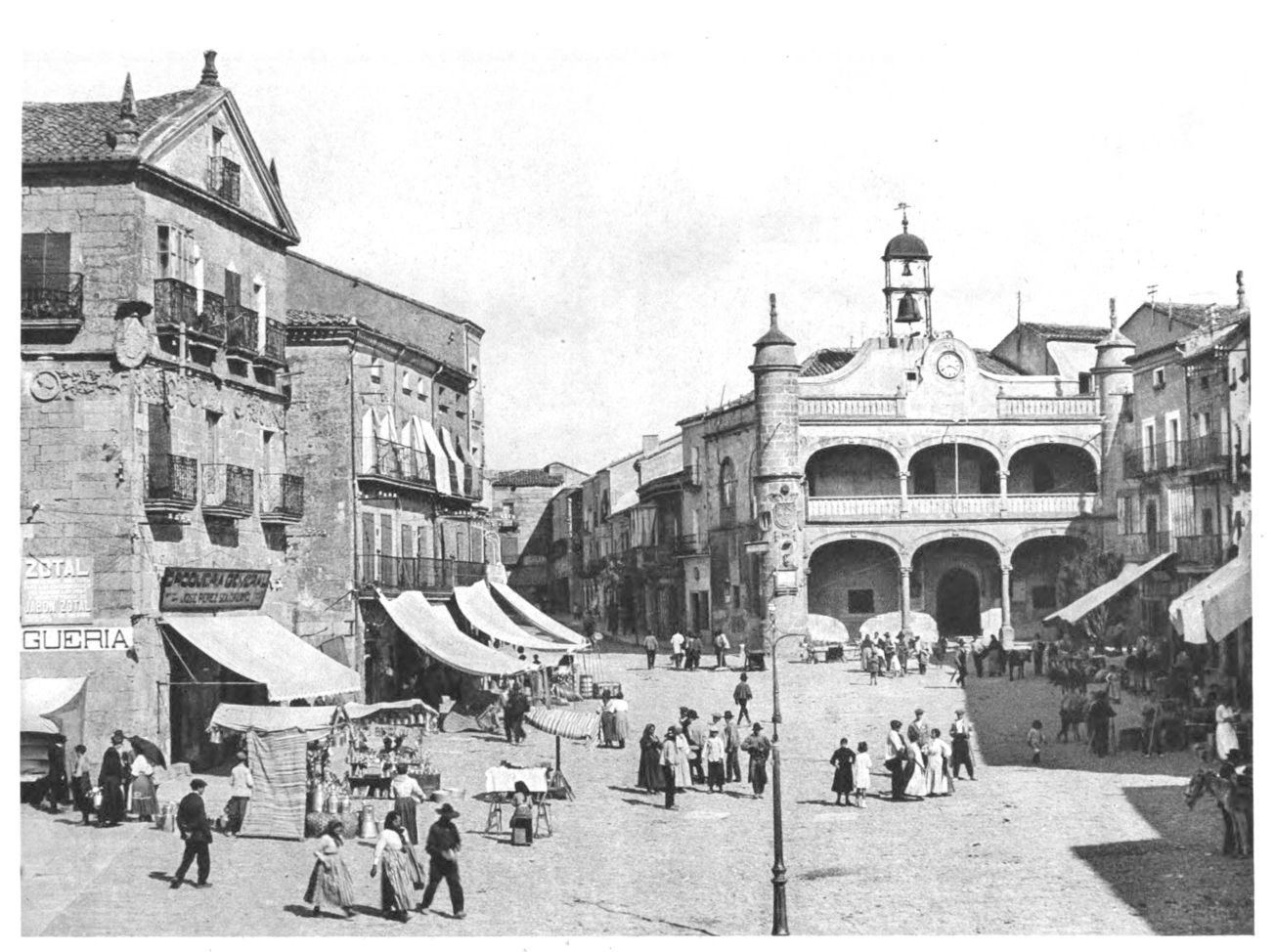

O

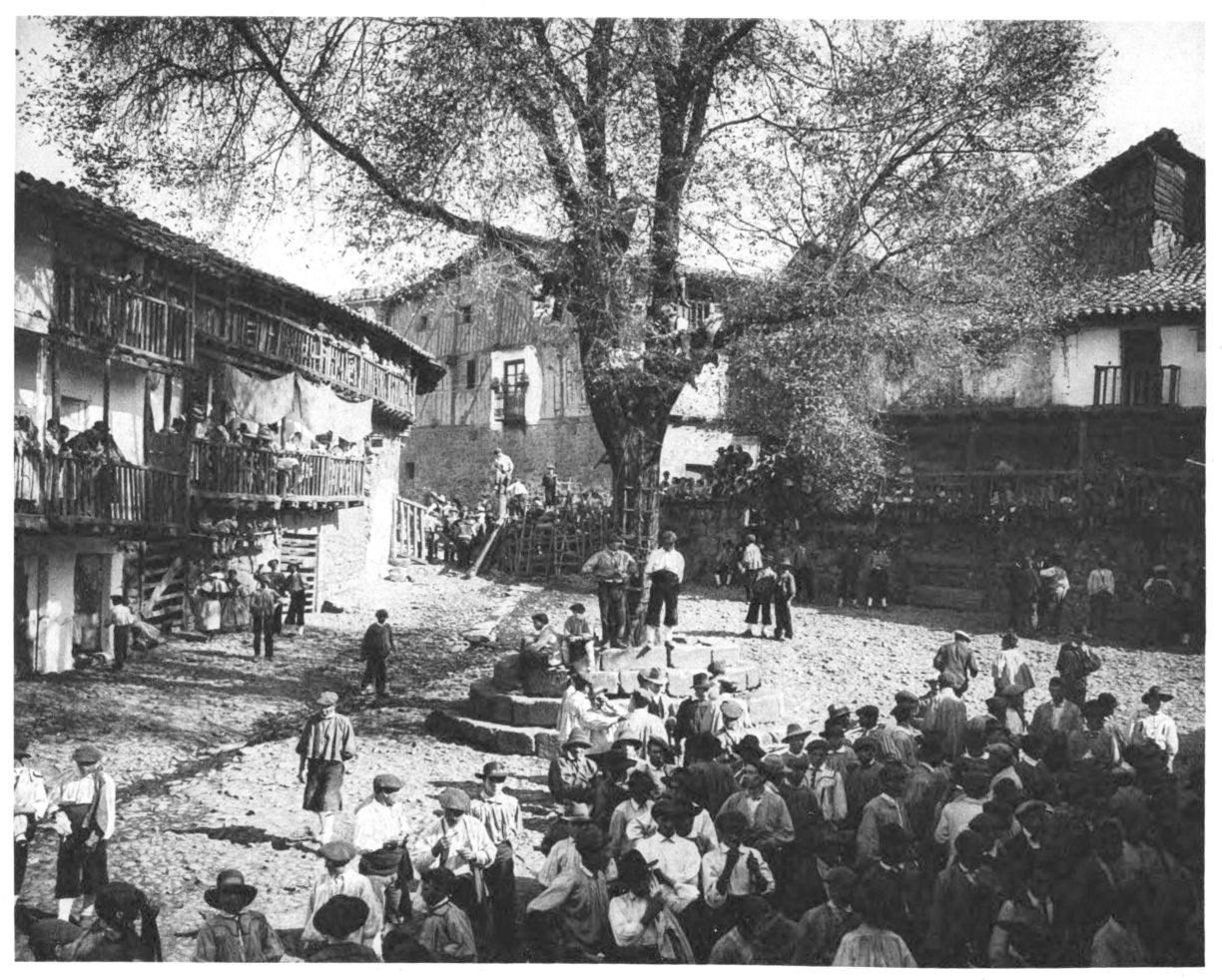

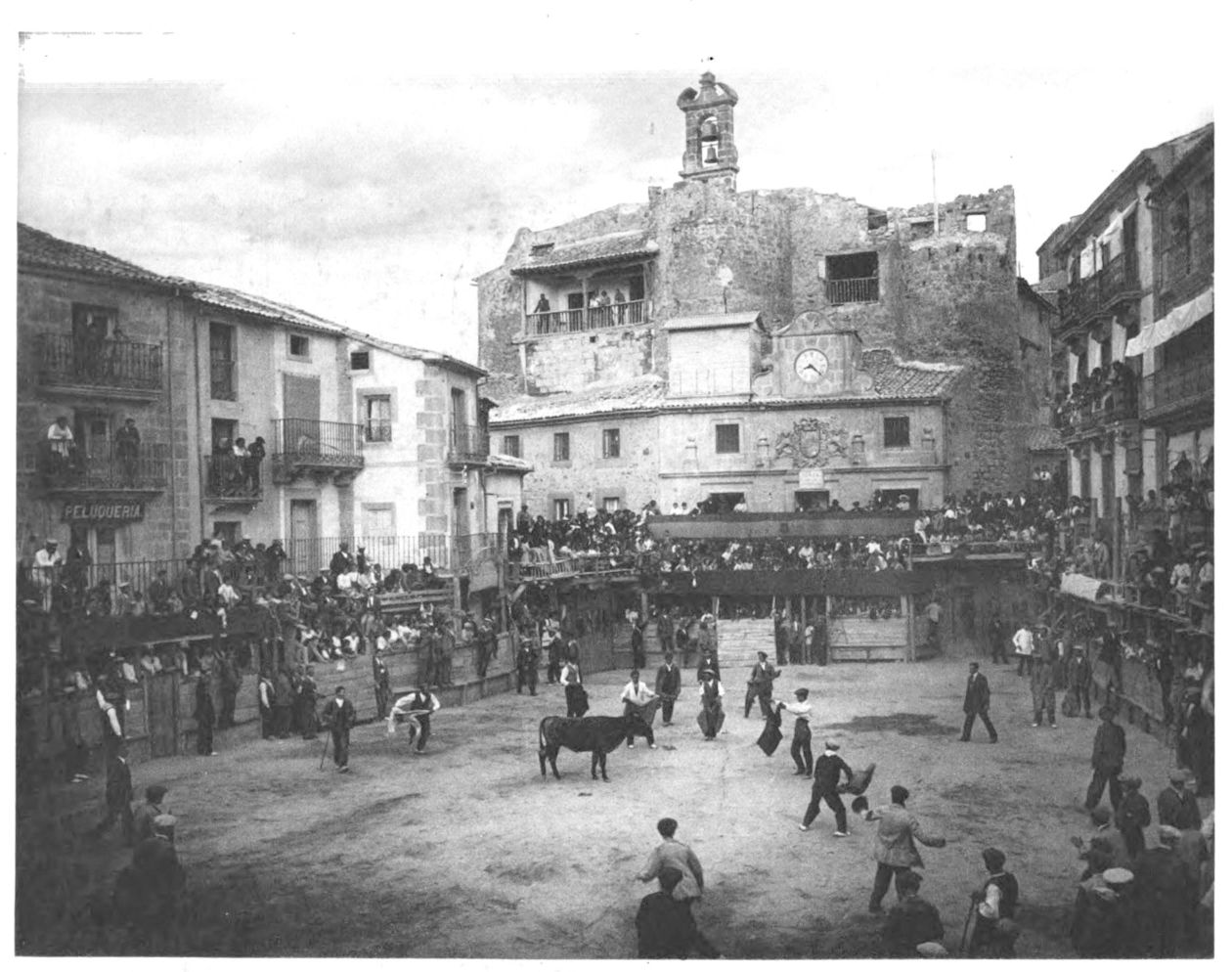

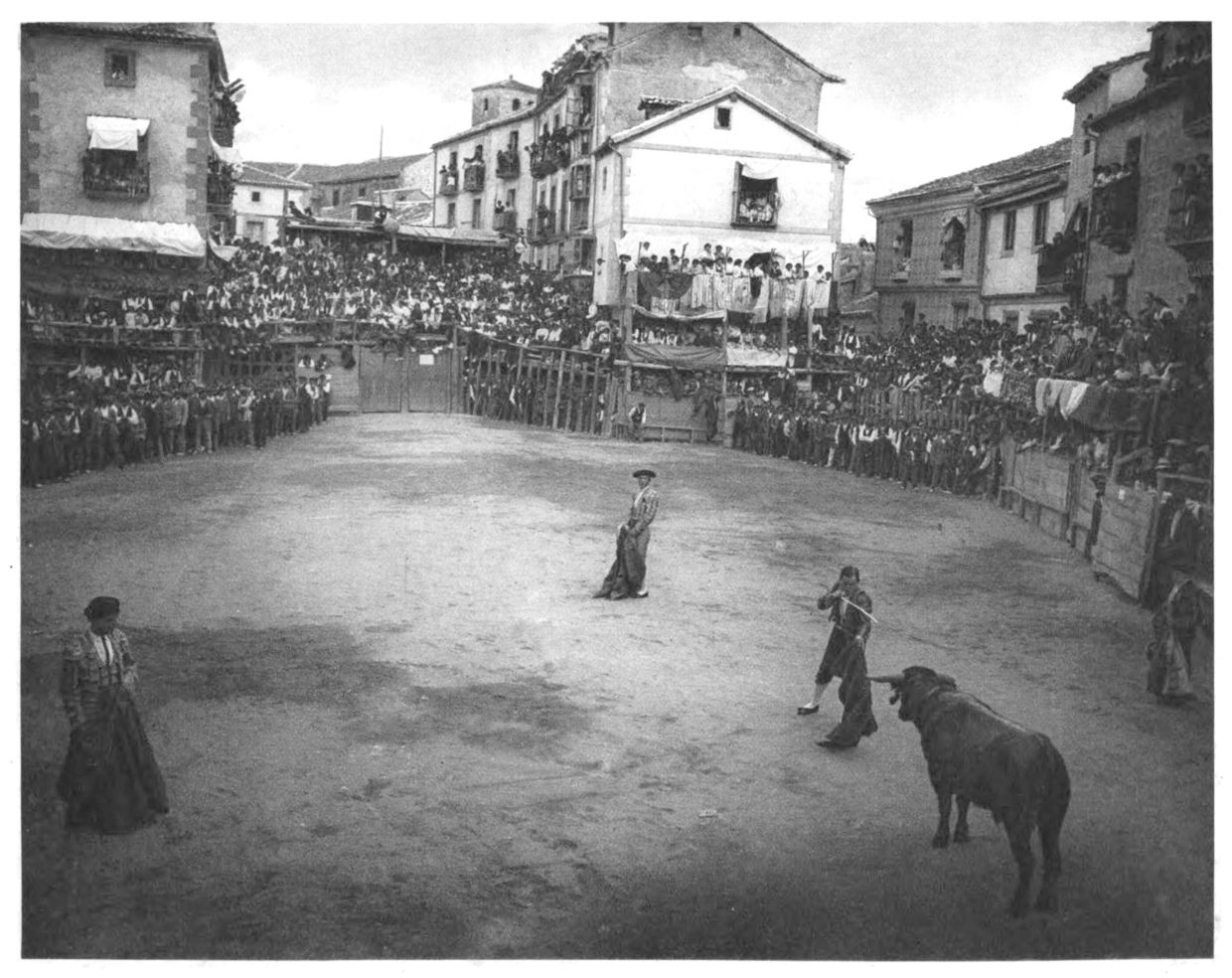

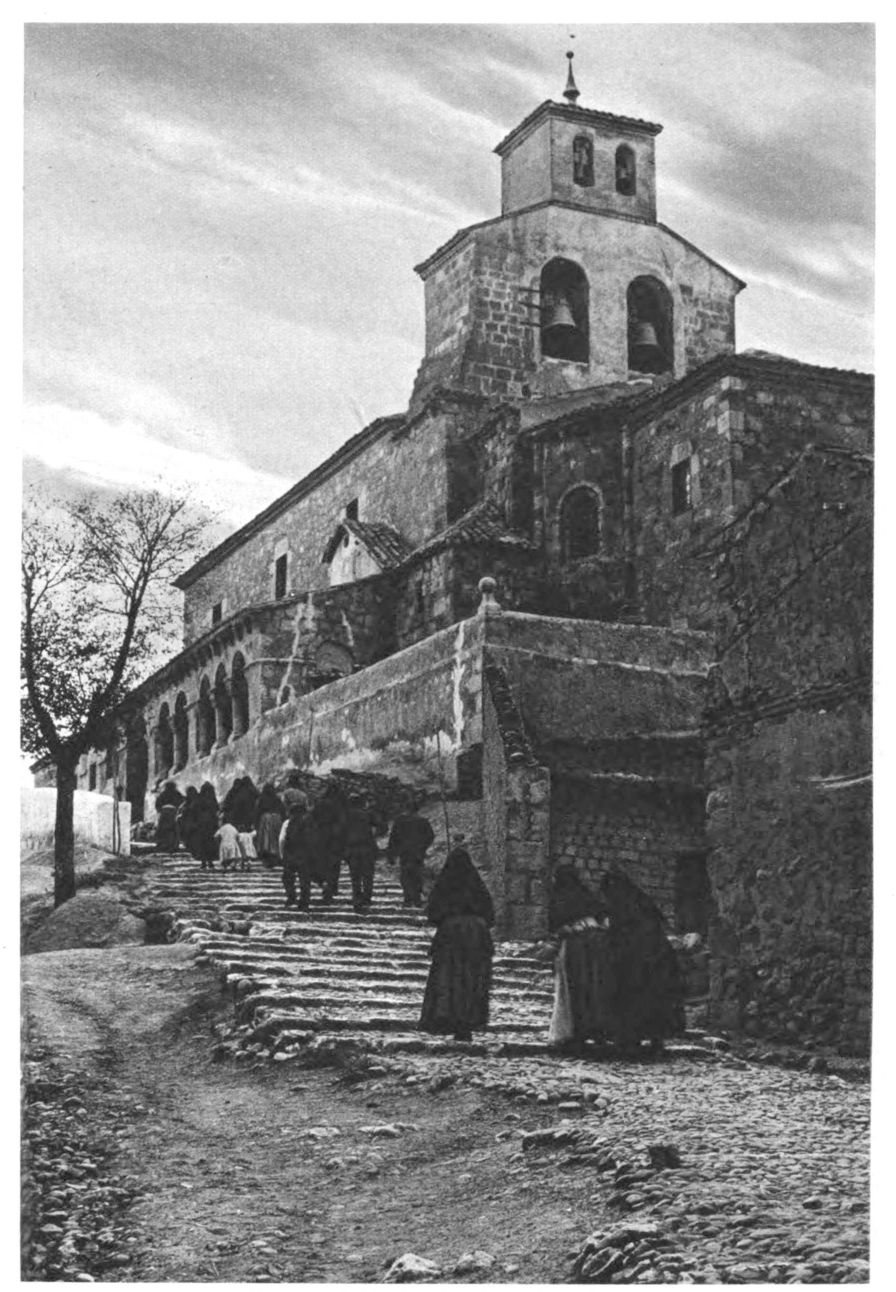

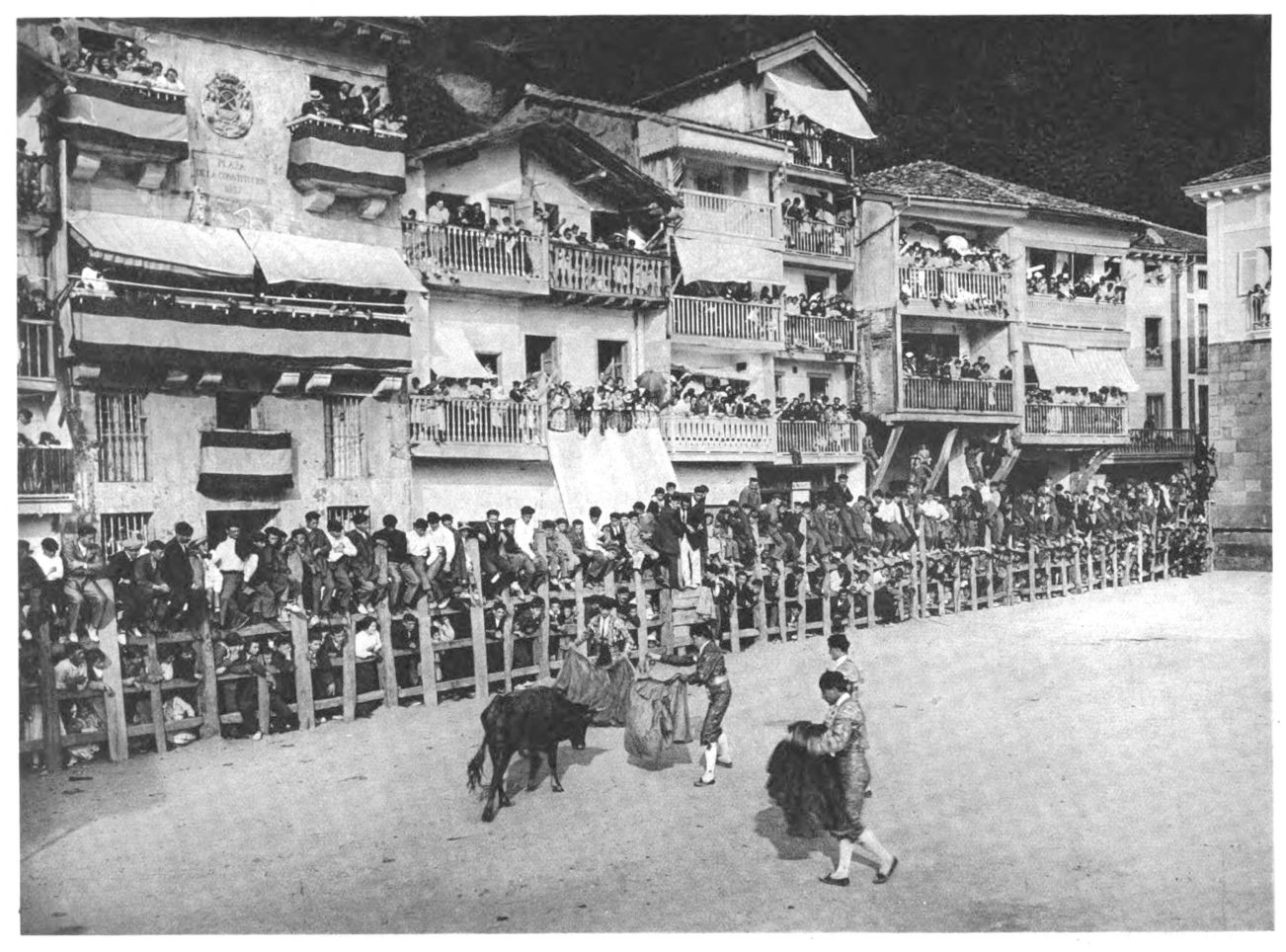

Feria in Sepúlveda.—A bull-fight. There is high holiday in Sepúlveda, (172, 173) an ancient little town far from the turmoil of the great world, and far even from the railroad, which indeed is nearly 100 kilometres away. The feria is the greatest day of the whole year. Men and women crowd into the place on horses and donkeys. Old friends meet again. Once more they see ‘life’. Above all it is the bull-fight that is the greatest attraction. It has been for weeks already the only topic worth speaking about. As however our little town has no arena, the market-place is used instead. All day the lively rat-tat of hammers is heard there. The windows of the picturesque dignified old town-hall gaze smilingly down on the lively scene. At last there is really something worth looking at again. Another long tedious sleepy year has gone by.

There is hardly any one who does not go the hour’s walk outside the town to admire the bulls which have come from a long way off, and for the present are being kept at pasture.

When the great day has come, every one is up with the sun. The arrival of the savage animals is feverishly expected. The bravest show their courage by going forth to meet the procession.

A cloud of dust on the highway announces its approach. And finally forms emerge from it. At the head a picador on horseback with a lance, behind him the black bodies of the bulls surrounded by tame steers, and followed by a second picador. As they rush through the narrow streets to the market-square a mighty cry goes up: “Los toros! Los toros!” Shouting, whistling, howling, yelling, and a general pandemonium rends the welkin.

Finally the bulls are secured, and it is only in the afternoon that the longed-for hour arrives.

The forenoon has its own pleasures. Young men demonstrate their daring by teasing a young bull specially selected for the purpose, and earn acclamation or mocking laughter as the case may be. These young heroes try to put into practice what they have seen at the Torero; only it is less dangerous. No blood is shed, only torn trousers and bruises are the honorific mementoes of the great day (174, 175).{xvii}

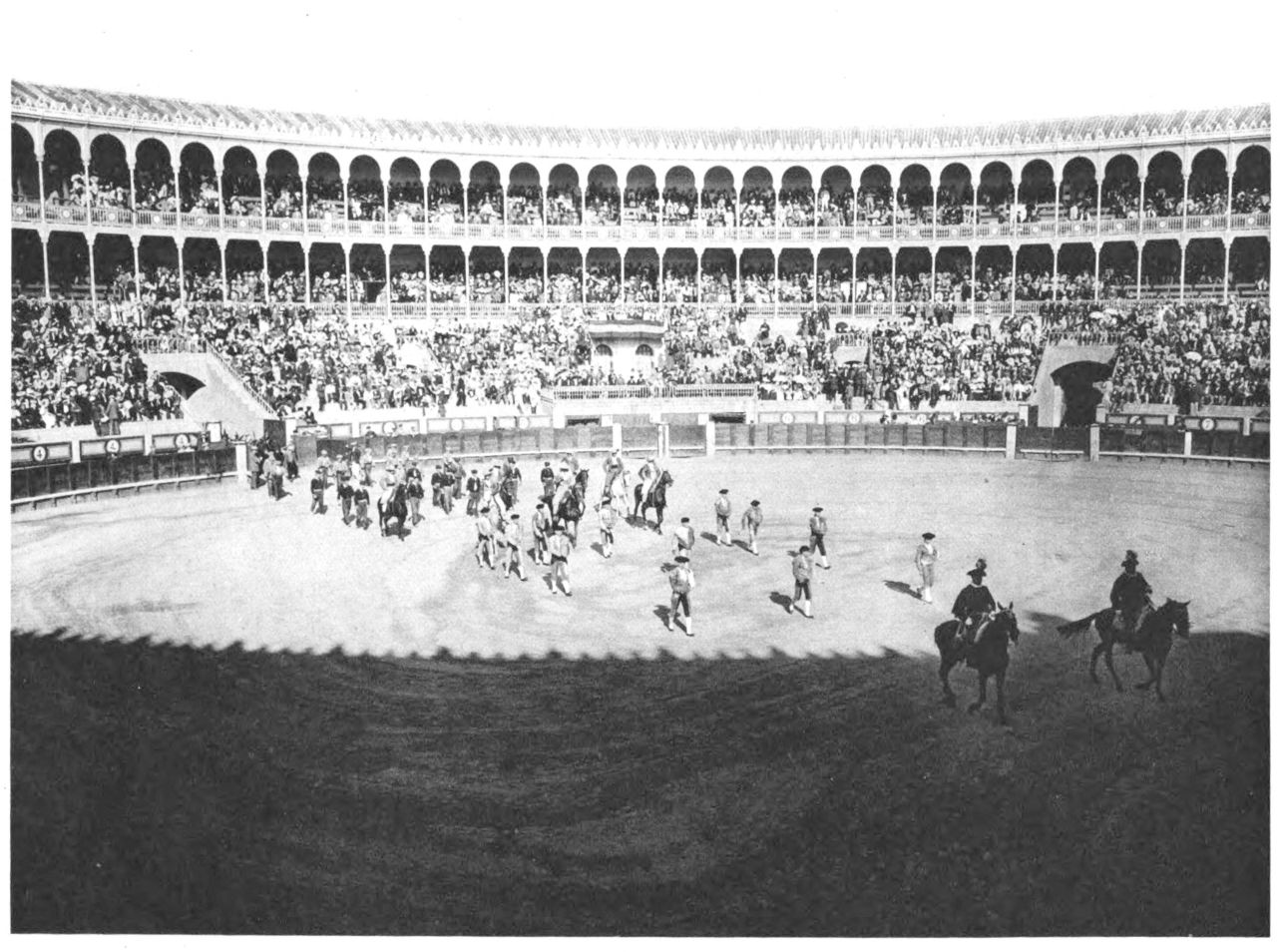

My thoughts naturally harked back to the first bull-fight I had seen—in Madrid. The impression was stupendous: fifteen thousand gay spectators in the great sweep of the arena all impatient for the nerve-racking fight to begin. The arena was filled with the babble of voices. It was a chaos of colours, cloudy lace mantillas, flower-embroidered shawls, fans swaying nervously, jet-black glowing eyes.—Shouts of applause greeted the bull-fighters. Yells saluted the great bull as he rushed in. The game was a risky one for life or death. Deeds of audacity were met with idolatrous cheers, the timid with desolating laughter. All of a sudden a coloured form is tossed into the air. A single scream from a thousand throats.—“Is he dead?” “No!” A sigh of relief.—“Go on!”—The condemned bull is mad with rage, his opponent cold as steel. He wields the mortal instrument, the sword flashes, and a hurricane of applause bursts forth for the victor and his tottering victim. White handkerchiefs flutter from every seat like pigeons. Hats are waved, a shower of flowers descends, and the fêted hero returns thanks, nonchalant and proud.—The trumpets blare and a new fight begins (125, 126).

O

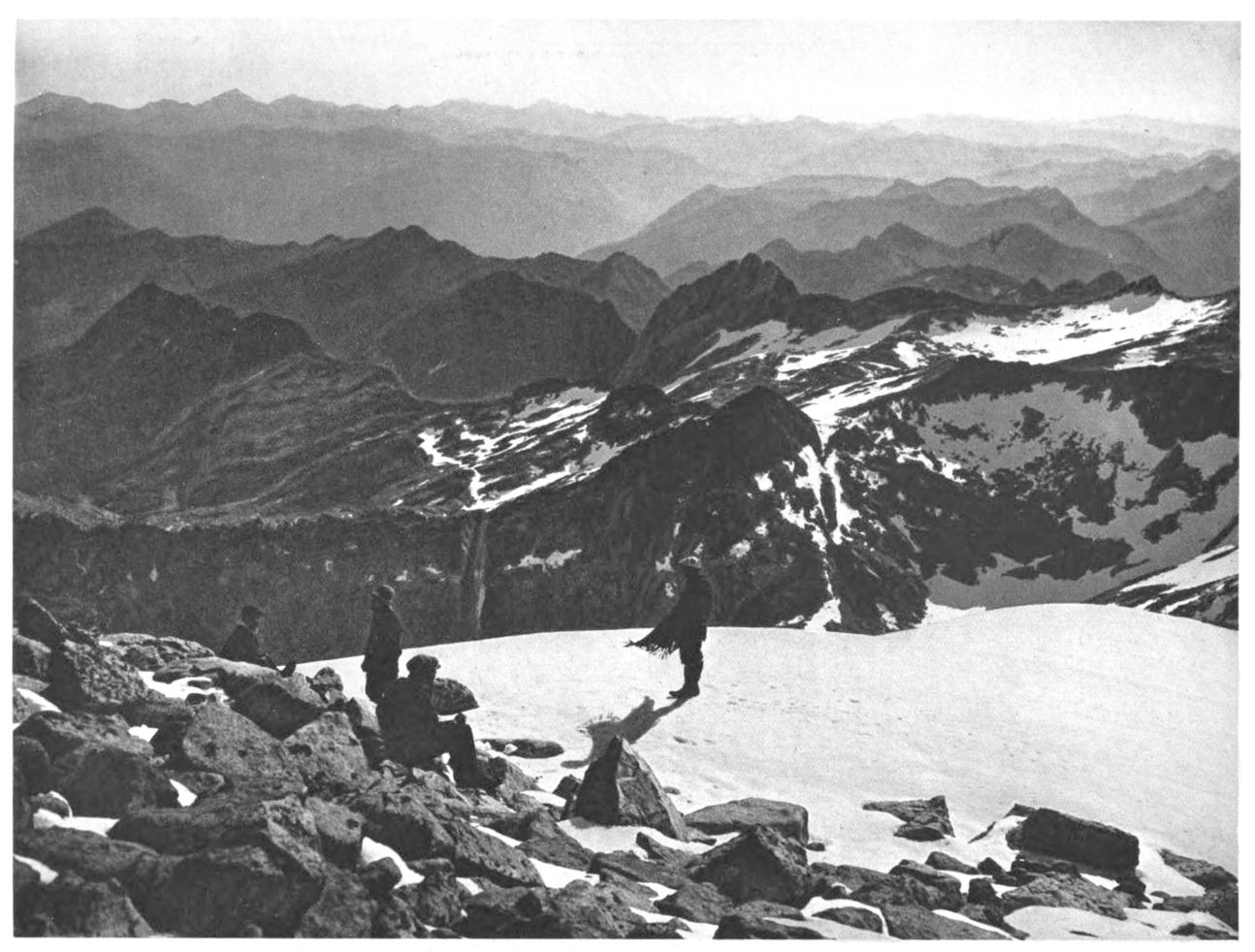

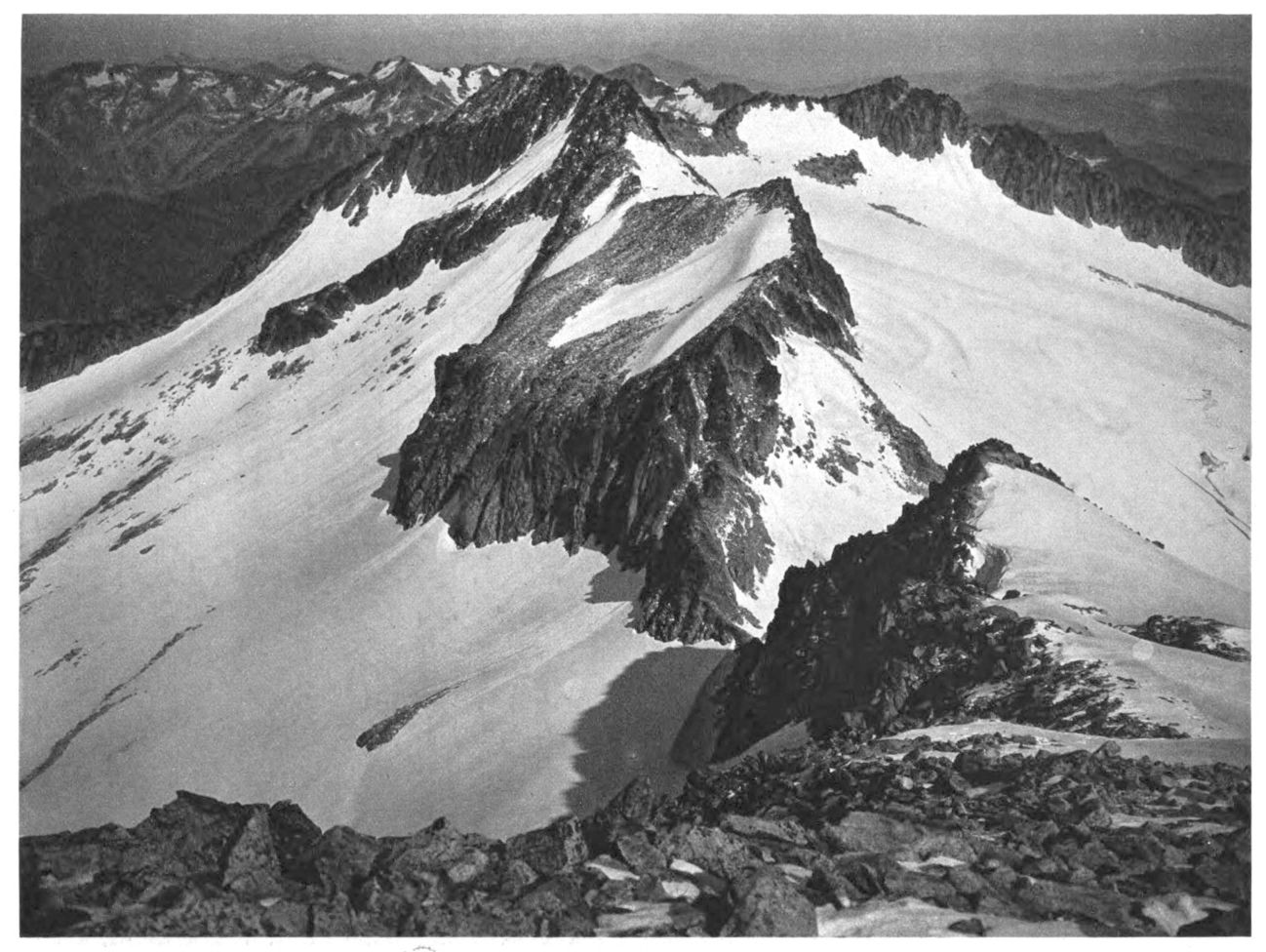

Crossing the Picos de Europa.—Masses of high mountains with peaks about 2700 metres high rise among the Asturian Cantabrian coast range. They bear the proud name of Picos de Europa (The Peaks of Europe). They are the Dolomites of Spain. But they exceed these considerably in inaccessibility.

Tourist facilities in Spain are of a very primitive nature. For this reason there are no shelter huts for mountaineers in the Picos de Europa, and there are likewise no trained guides. There are it is true some game-keepers. Shepherds and miners acquainted with individual parts of the mountains act once in a while as guides.

I had been at the gateway of the Picos de Europa when at Covadongo the celebrated place of pilgrimage. Since then the desire had never left me to become acquainted with this demure mountain beauty so alluring and yet so stand-offish in her loneliness. Thus I started for the mountains.

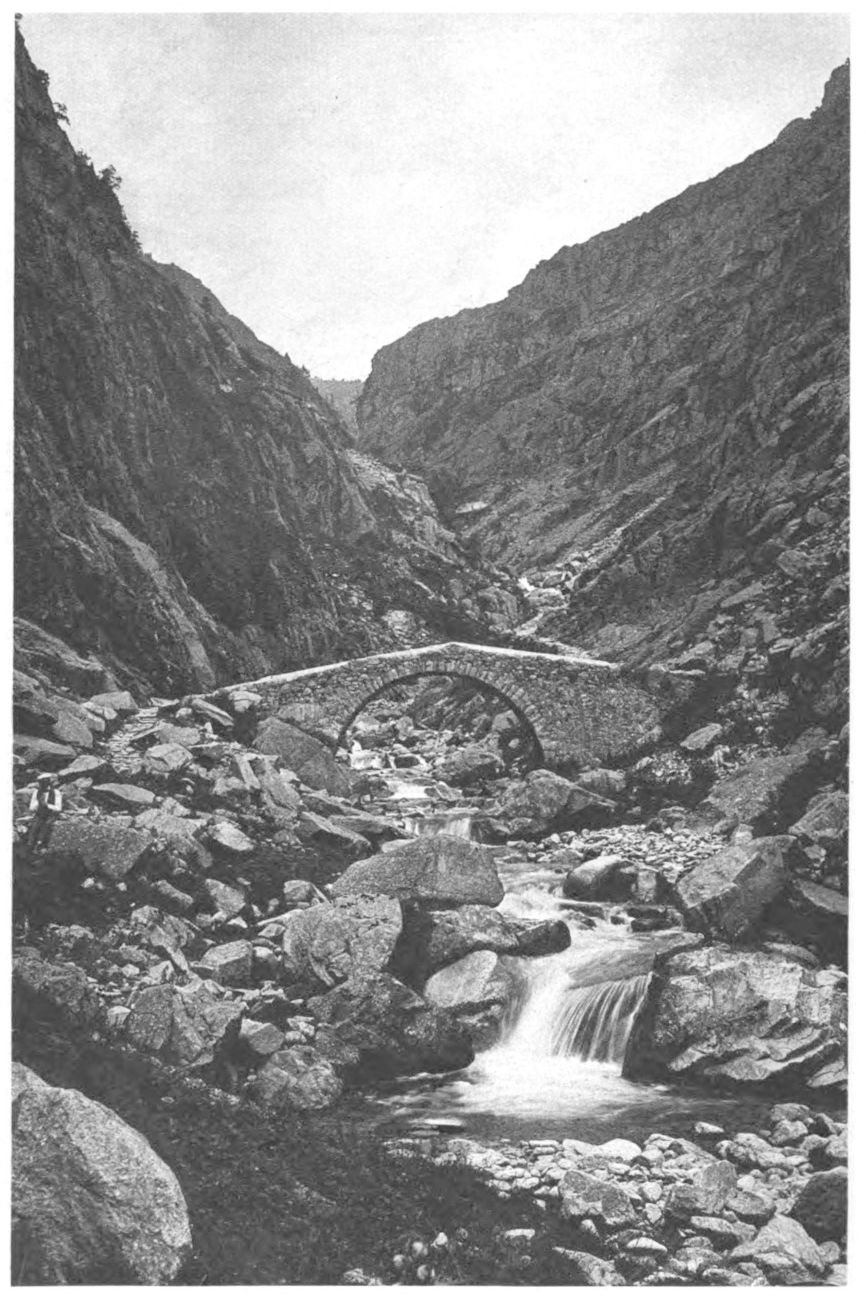

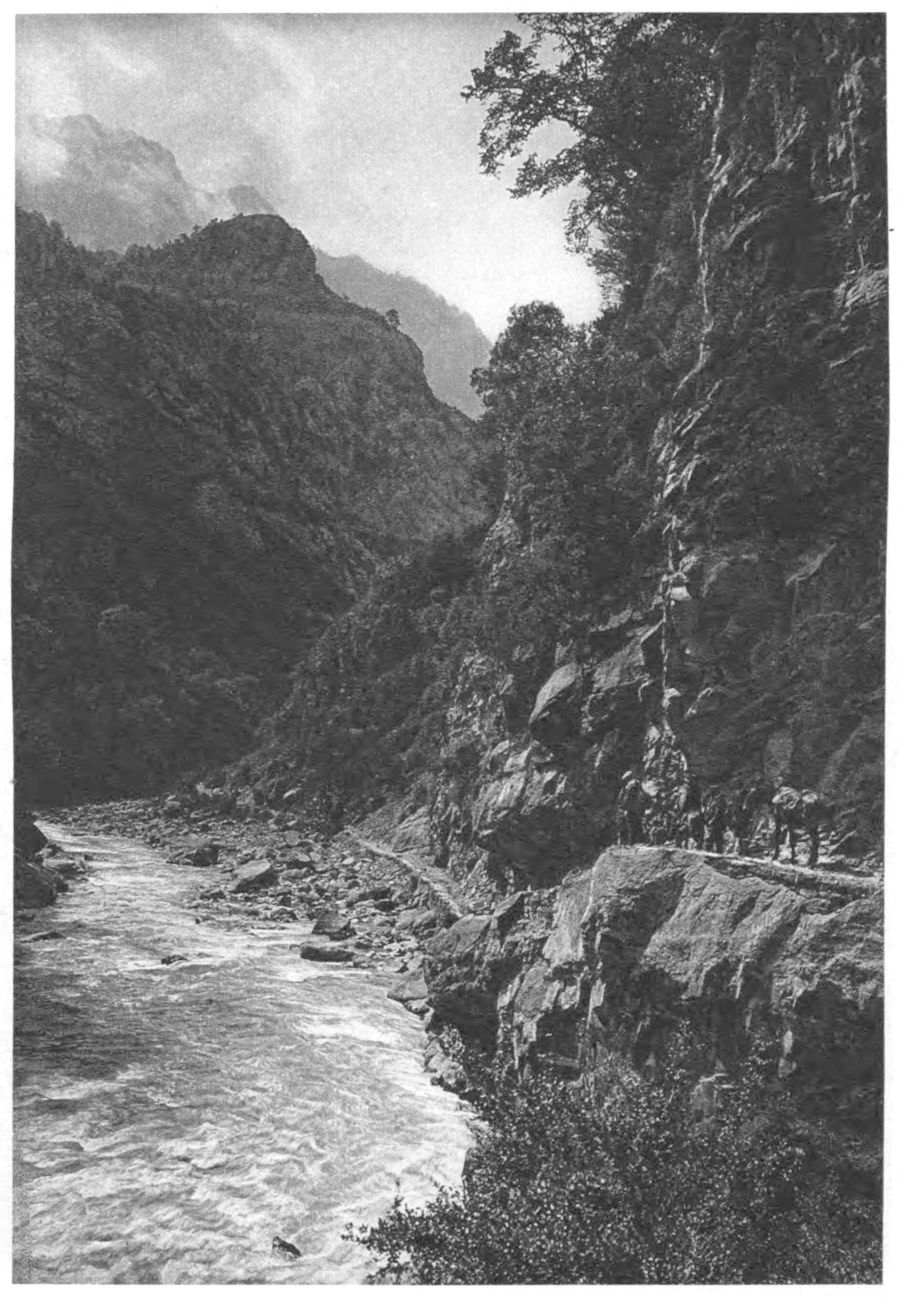

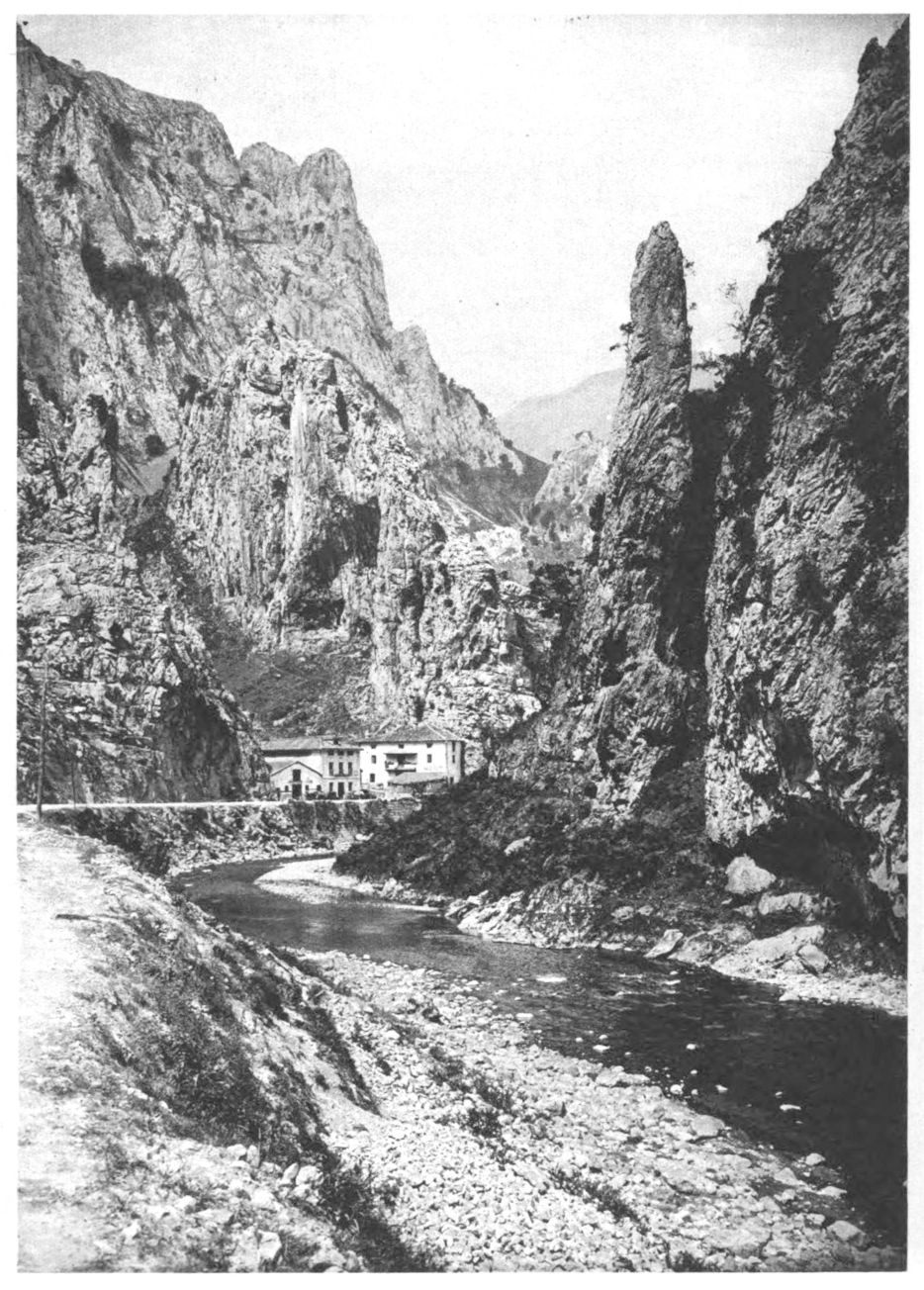

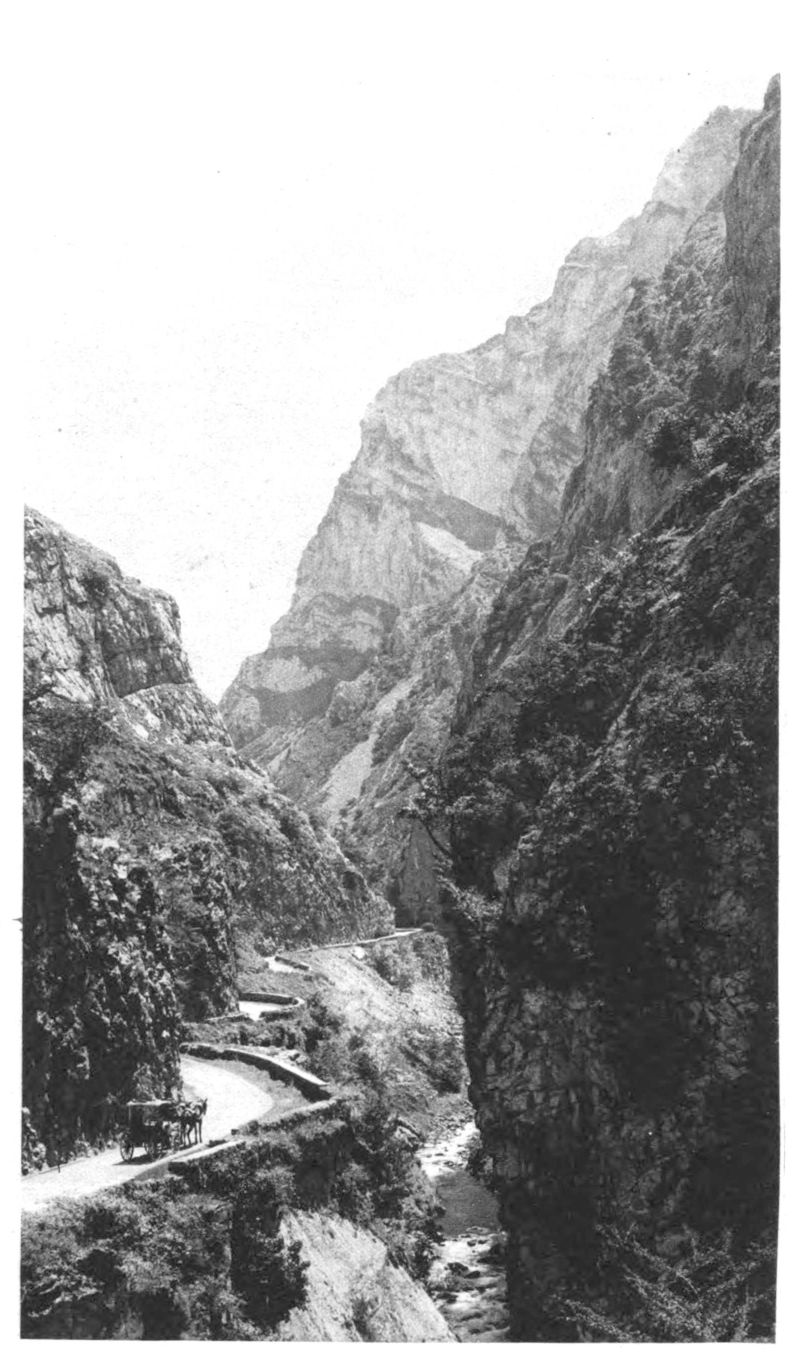

My path led me from Unquera through the Deva valley to Potes at the foot of the Picos. I very soon noticed that my task would be no easy one, for shortly after leaving Panes the track winds through a mighty and deep valley known as the Desfiladero de la Hermida. My reception was not a friendly one. The rocky guardian of the valley looked down and frowned at me, and the sky treated me at intervals to a cold shower-bath.

In Potes the clouds were low down on the mountain sides on which I was going to test my prowess the next day. But I was so enchanted with the spot, that I willingly renounced the view for that day.

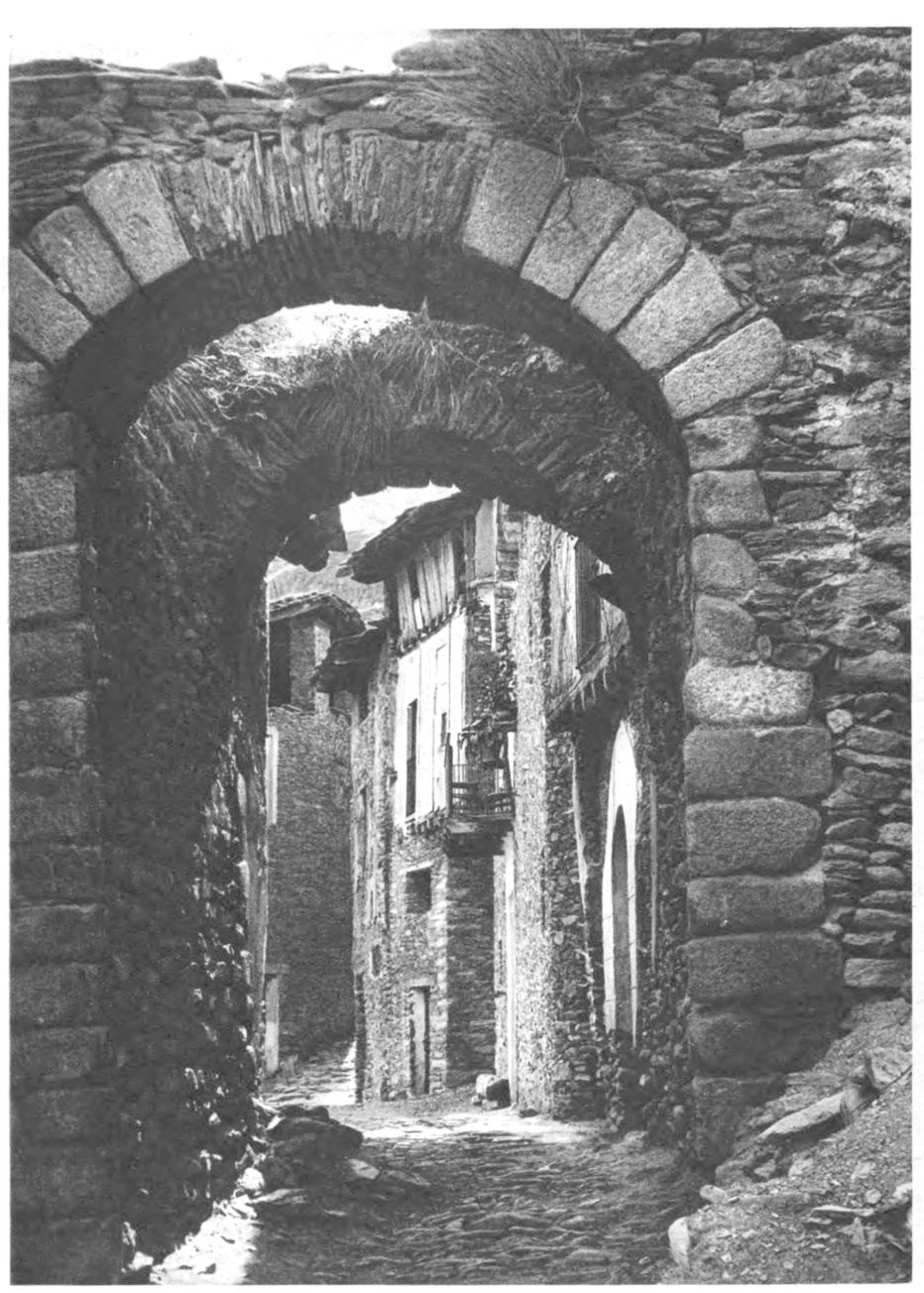

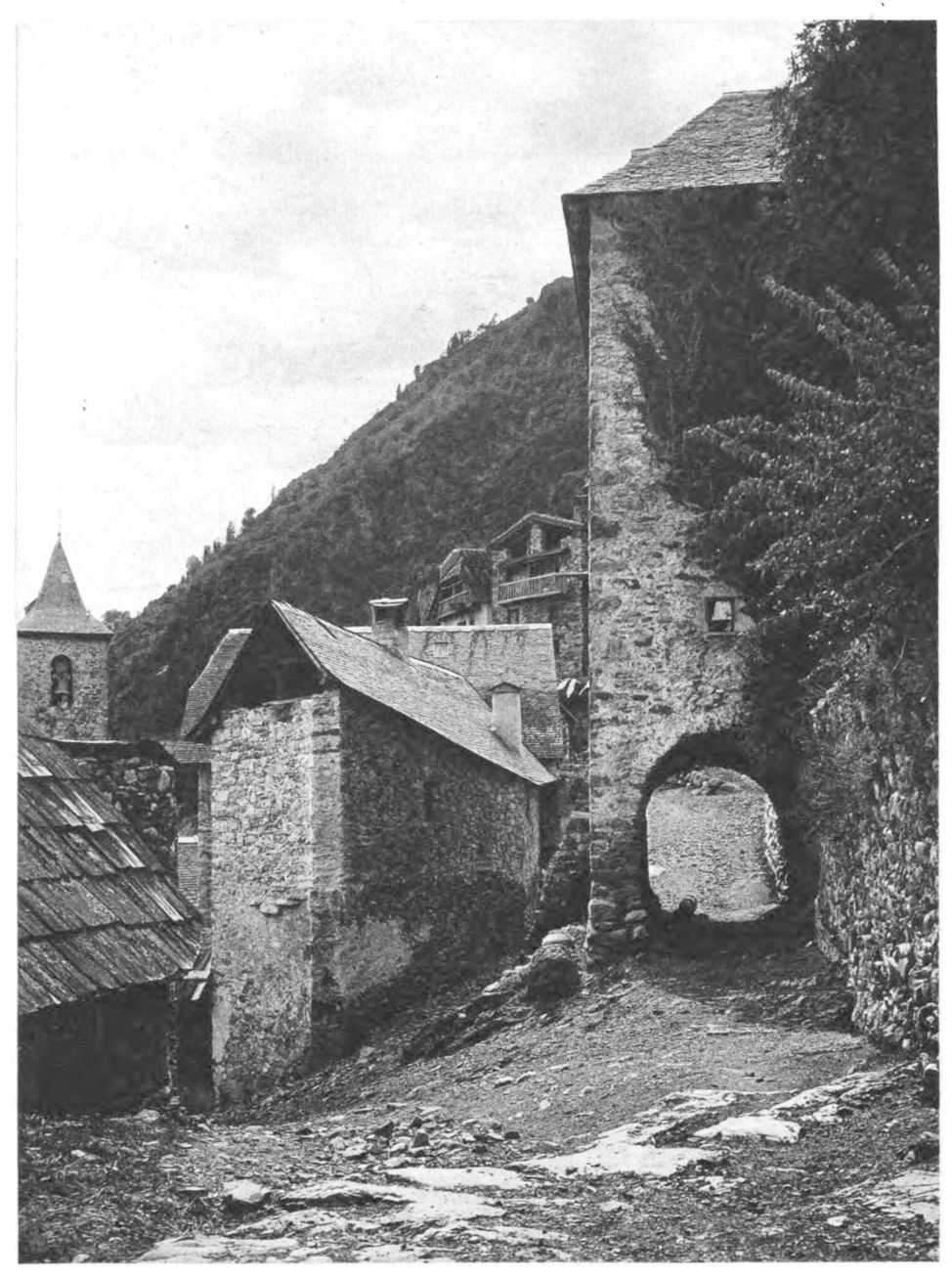

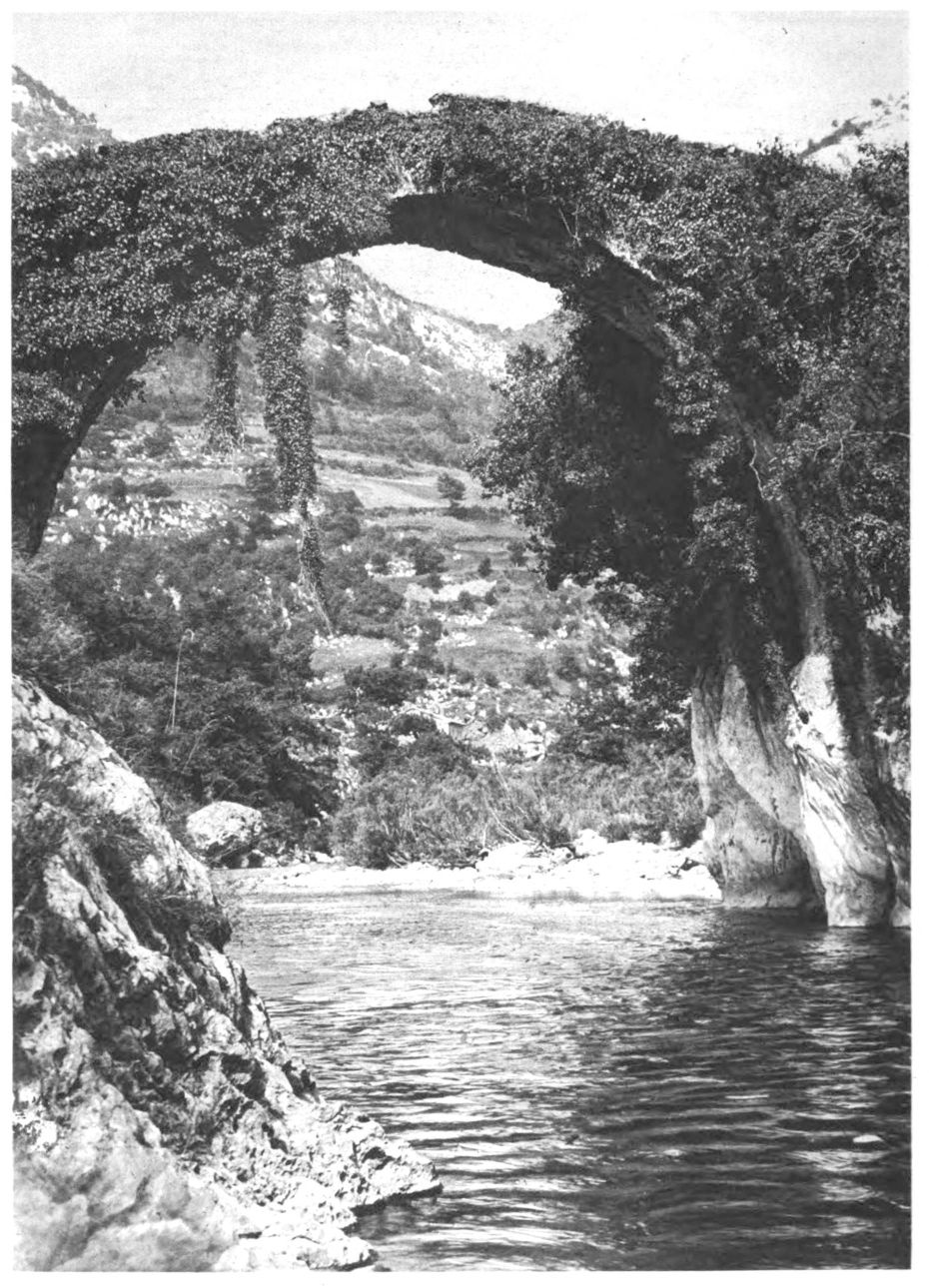

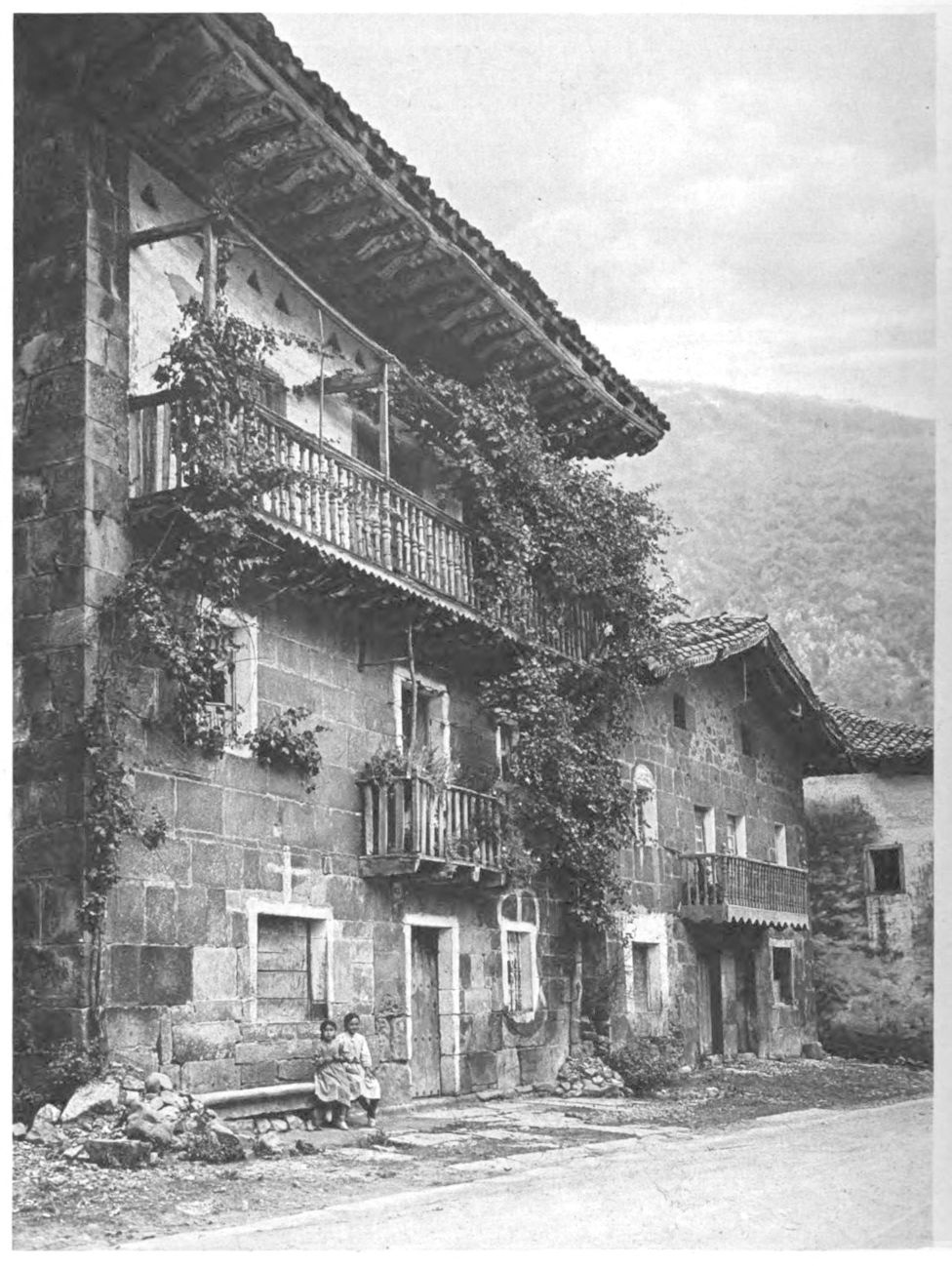

The little town is a very ancient spot. It must once have been the seat of many a knightly family. This is attested to by the various Spanish coats of arms on the houses. But those times are now no more. Where once Spanish grandees strutted by with buckled shoes and sword, clodhopping peasants plod along. And the present generation is hardly aware of the plentitude of beauty surrounding it. Bold bridges span the glen. Narrow colonades with overhanging balconies cling to the steep river bank. A multitude of archways offer innumerable enchanting glimpses. A high watch-tower guards the houses clustering at its base.

Before the sun had risen on the morrow I had set out. Dark and dismal-looking clouds hung low over the landscape. But the Picos pinnacles had rent them asunder, and suddenly they stood forth in the glory of the rising sun. Dark night lay behind me as I marched towards the sunlight.{xviii}

My guide met me by arrangement at Espinama. He was a grey-headed man with weather-beaten face and smiling eyes. His feet were clad in leather sandals, and under his arm was an ancient umbrella. We soon discussed the itinerary, filled our rucksacks and started for the Puerto de Aliva. The old song came back to me:—

As we passed on our way, the houses of the village became smaller and smaller. We soon left the last tree behind, and our path led over sweet green slopes, till they too were lost under the stony debris of rocky giants. There was a hunting-lodge close to the foot of the Peña vieja cliff which the king of Spain visits nearly every year when chamois hunting.

The day drew slowly to its end. Great streamers curled round the Peña vieja, pale shadows floated by like silver grey cobwebs, and the mist rose and fell with every breath of wind. The billowing fog had already wrapped us in its mighty veil when we reached the miners’ inn at Lloroza. An overseer invited us to spend the night there. And we were right glad to find shelter, in spite of the fact that both the hut and its furniture looked like the first attempts of primitive man to scale the ladder of civilization. The night we spent on the hard ground was not a very restful one, and we were glad when the approach of day called us from our layer.

When we left the hut a surprising spectacle met our eyes. The fog which had deprived us of any possibility of obtaining a view the evening before now lay at our feet in the valley. The summits of the mountain rose like islands in the sea of mist.

The moment had arrived when day struggled with night for predominance. The full-moon’s silver disc hung in the deep blue of the western sky, and the morning star held its own for a while against the rising light in the east. At last both moon and star turned to pale glass when the sun sent forth his herald rays. The horizon was tinged with pink; long red streamers fluttered from the windows of heaven to greet us, and then the sun rose above the misty expanse, gilded the crests, flooded the eastern pinnacles with the glory of his light, and glowed on the rocky wall to which our hut clung. O wonderful silence of that hour!

“A new day beckons us to other shores.”

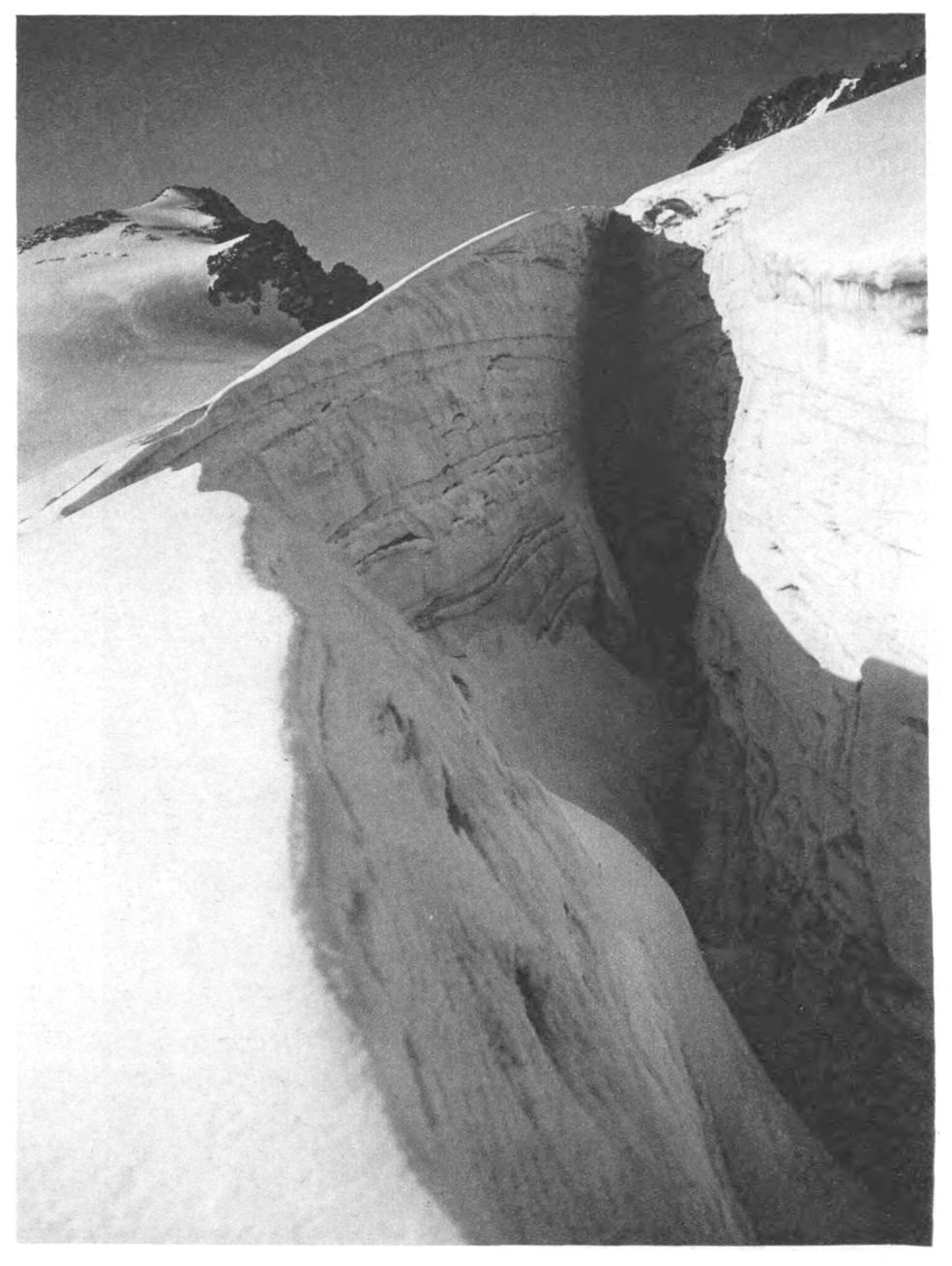

For yet a short distance the beaten path used by the king when stalking showed us the way. Then we bent our steps over pathless boulders, sharp edged rocks, mounds of debris, snow-fields strewn among the stony desert with its jagged rock walls and towers.

Whole herds of chamois stared in astonishment at the strange intruders in their paradise. For the rest, they showed little inclination to run away. The mountain fastness became progressively more barren and wild in its aspect. An infinitely dismal mood seemed to brood o’er the scene. Yet the magnificence of these mountains augmented from minute to minute. Grotesque stone giants—cast in burning ore by the furnace of high heaven—stood guarding this great grave of nature.

Woe to the wanderer whose ignorant footsteps err here! Death lies in ambush in the deep crevices and chasms.

At last we halted in front of the monarch of the magnificent mountain empire. His throne stands high in everlasting snow; a golden crown is on his head. His picture is known to all from the most distant mountain valley to the shores of the restless ocean. All admire his beauty, all know his name: Naranjo de Balnes.{xix}

This huge rock colossus rises 600 metres over its surroundings. Its perpendicular walls show hardly a crevice. And it seems incredible that nevertheless that bold mountaineer the Marqués de Villaviciosa de Asturia climbed to its summit.

On our wanderings round this mighty and stubborn rock tower we seemed to be lightened of all earthly burdens high up there in the solitude above the depths of humanity.

We climbed up to the Ceredo tower. The rocks were as sharp as knives. Again the ghostly mist rose from the valleys and whirled spectrally around us.

It was 5 o’clock and the Cares valley with Cain to where our steps were directed were not yet in sight.—I asked my companion: “How far yet?” “A few hours more” was the not very consoling reply.—The mist, that enemy of mountaineers was getting thicker. And ere long we could not see twenty paces ahead. The feeling of insecurity grew apace. And the sensation of climbing with mist-bound eyes was terrible. Again I questioned my guide. “Severo, is there no hut or shelter on the way?”—“I don’t think so.” Once more long minutes of silent groping. At last we were, at any rate for a while, rid of the stony region. Here and there a rocky projection, but it was quite impossible to tell if we were not suspended on it hundreds of meters over a yawning abyss. It was impossible to see anything through that fog. And at a quarter past six it was pitch dark.

Suddenly we came across a few low rough huts of unhewn stone huts sheltered by a rock-wall. There at last we could spend the night. But my guide wanted to go on. “Stop!” I cried. “Can we get to Cain to night?”—“I don’t know.” “Well then we’ll stay here!” Suiting the action to the word, we crept into one of the huts, crouched down, and slept fitfully through ten endless hours of night. But even they passed. The morning meant a dangerous and nasty descent. We waded knee-deep in wet grass, clambered over ledges with fog all around us. Woe to us had we slipped! Then we got lost and had to stop and climb back with the greatest care. Then we slid down a stony gully in which nearly every step set rocks thundering to the depths below.

At last the moist grey mist began to lift. A rift showed the bed of the valley far beneath us, and, as we thought, houses. But no, we were mistaken. They were huge boulders, the wreckage of some avalanche that filled the upper hollow. Down and down we scrambled till finally we broke through the foggy screen. Our goal was at our feet. Cain, strangely walled in by precipitous rocky cliffs rising sheer 1500 metres high. We were there! And we could rest. Some bread and butter was all we could find in the whole village to appease our hunger. We would gladly have rested there a day, but the place was too inhospitable. We had therefore to shoulder our rucksacks again. The distance we had climbed down the day before, we had to climb up again on the opposite rocks of the Peña santa. Hours and hours of strenuous efforts passed till we reached the ridge. We re-descended valleywards in a drizzling rain. Lake Enol was the last spot of beauty to be hidden from our view. It was there we struck the main road, and then marched another 10 kilometres down to Covadonga which we reached as tired as dogs.

Night had already cast her shadow over the valley, and the stars were beginning to shine forth. Welcoming lights were seen burning in Covadonga. But it seemed as though we should never reach them. However the prospect of a bed lent us strength, and at half past eight we stumbled painfully over the threshold of a clean hospitable house. I went to bed exhausted, and my restless dreams were haunted with the beautiful and terrible wanderings in the Picos de Europa (266-274).

O

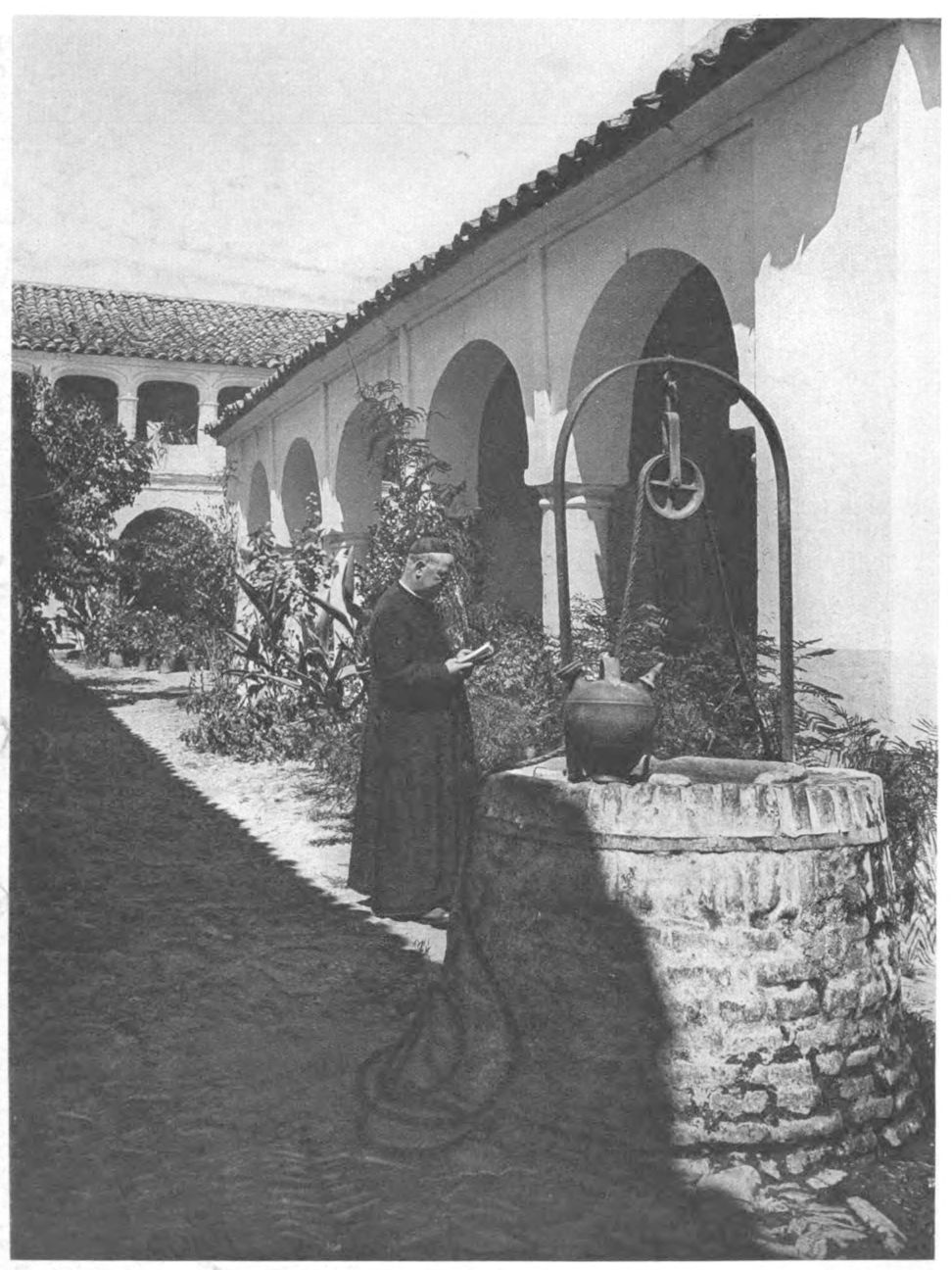

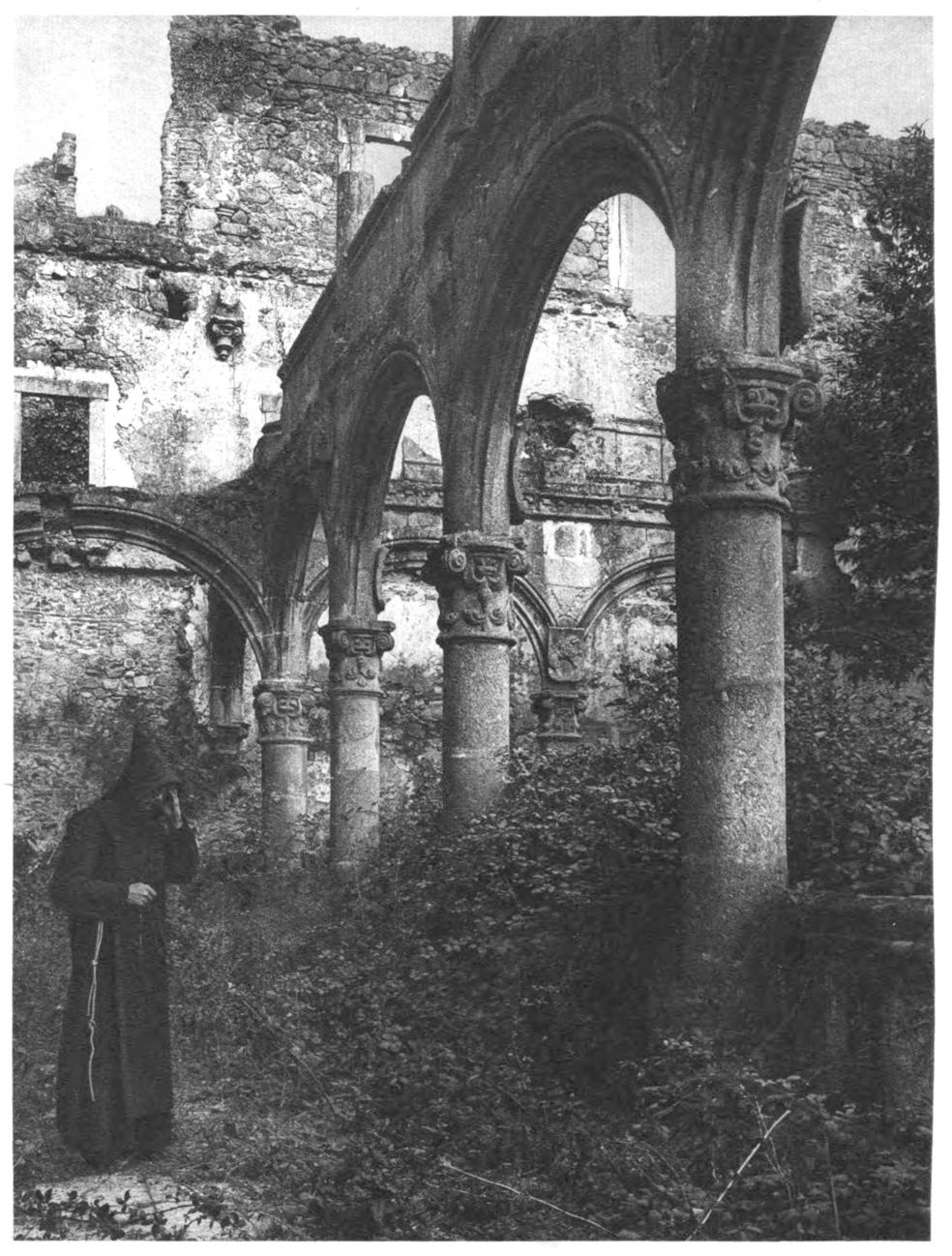

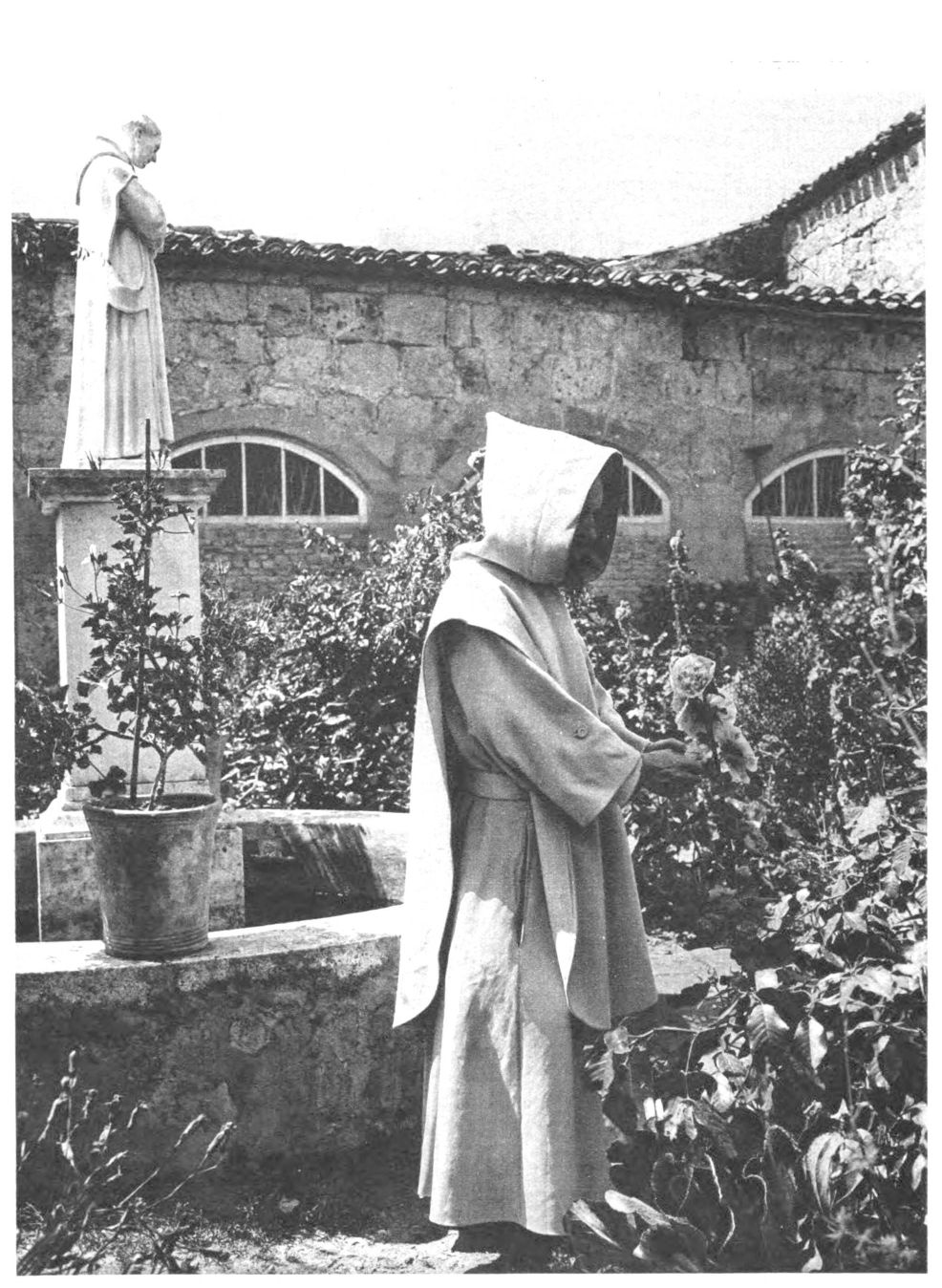

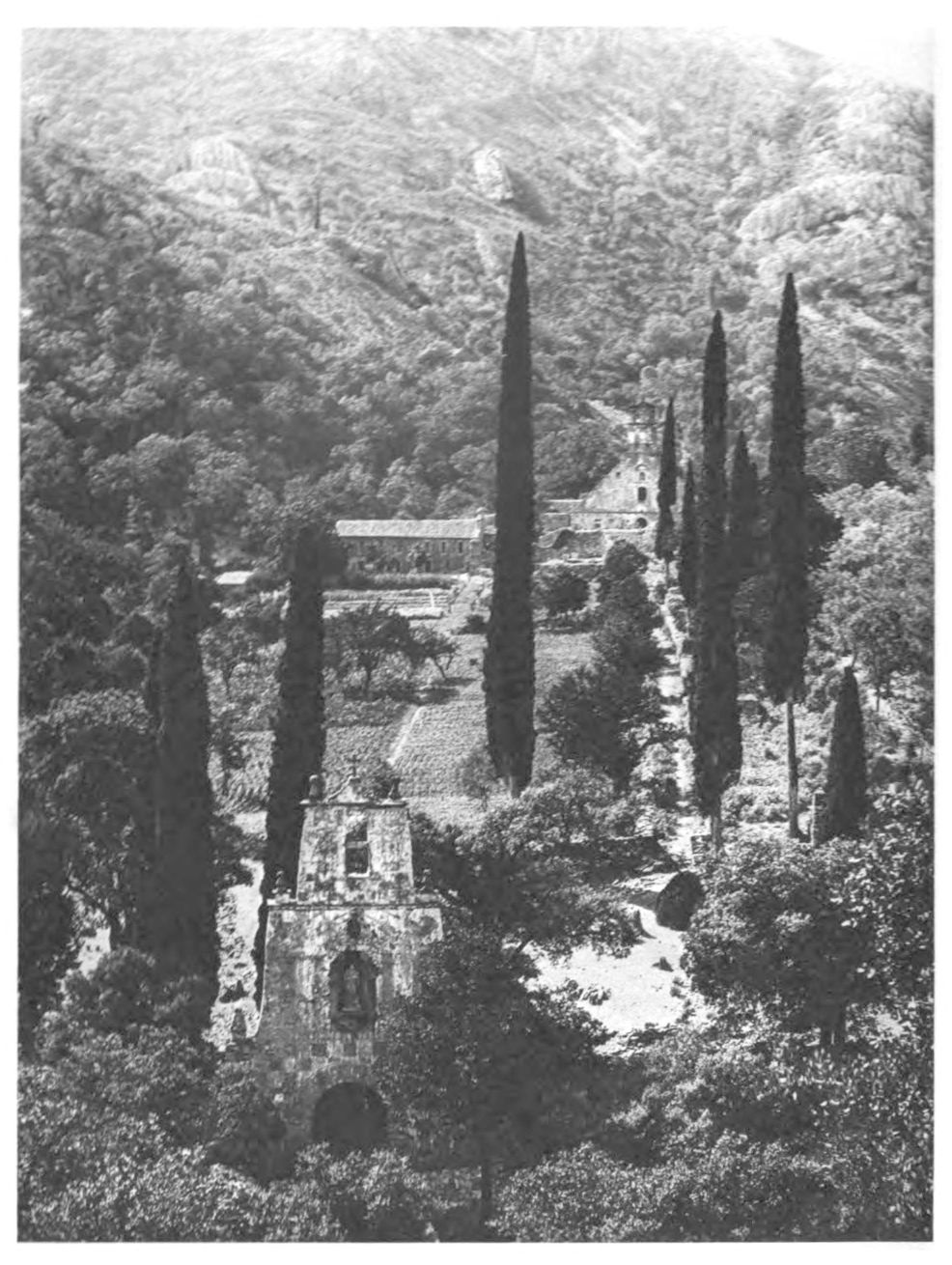

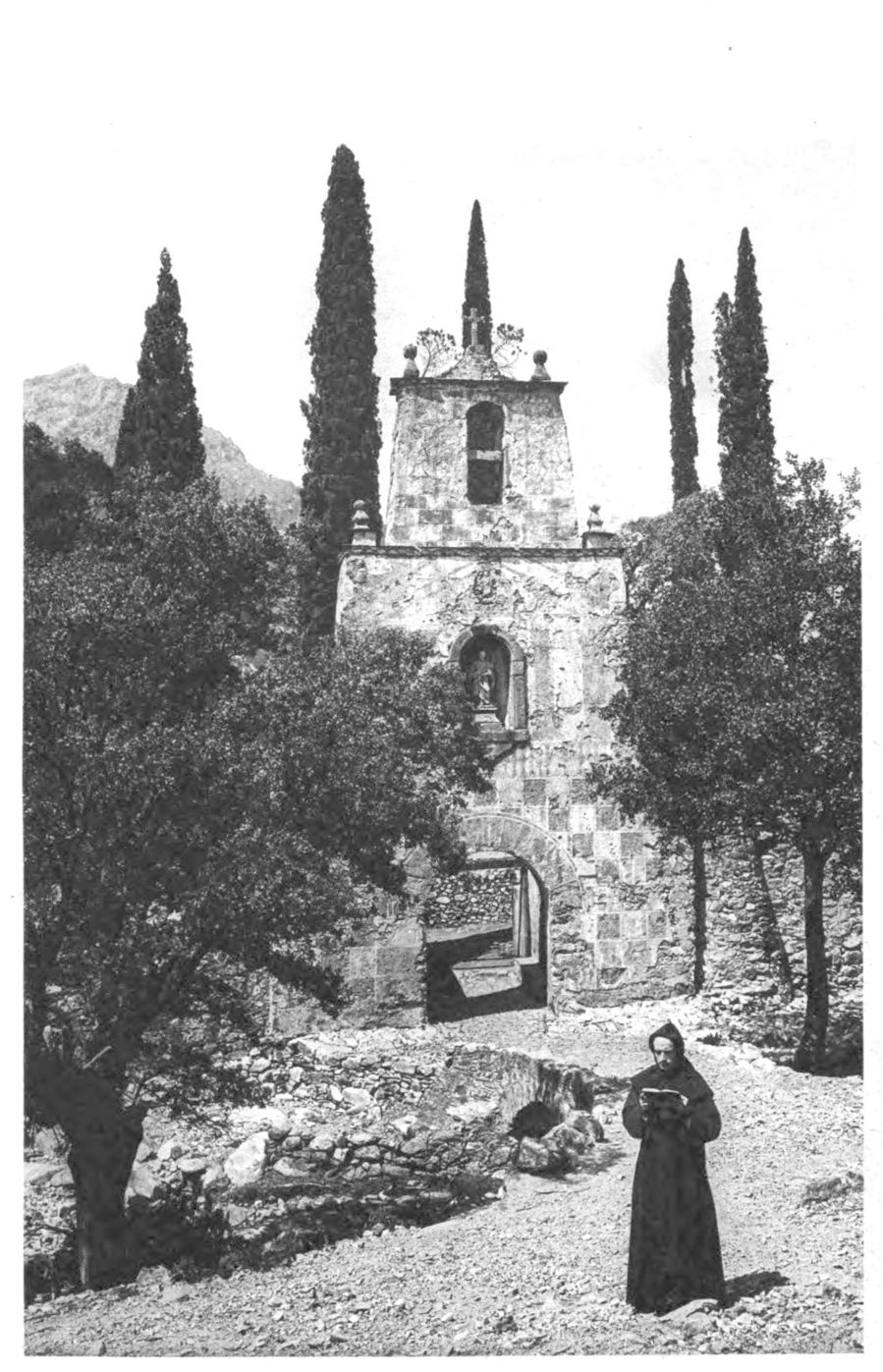

My pilgrimage to the Yuste Convent (153).—I left soon after midnight, for marching is delightful in southern nights when the glittering stars shed their soft light from the great vault of heaven. In the south the cool night is succeeded by summer days that are the misery of the pedestrian.—The hours melted by but slowly in the furnace heat of the day. I was beset with all possible ills: infernal heat, thirst, and no water. Not a tree or a shrub was to be seen for miles; no shade; hours without passing a house; not a soul abroad; the melancholy mood that comes in the train of solitude. My path was obstructed by a river—at any rate, water—but nary a bridge! So I had to wade, and continue my journey. At last I spied a shepherd. What joy to feel that I was no longer alone!

“Is this the right road to Yuste?” I enquired of him.—“Yes, but where doest thou come from, and what countryman art thou?” The good fellow addressed me with the fraternal tutoyer, as though we were brothers.

When he heard that I was a German he was quite surprised. He willingly agreed to accompany me to the next village, and was quite curious to hear something about my country. The news of the war had penetrated to this remote part of the world. It was charming to listen to the questions of this child of nature. He knew nothing of the three Rs; had never seen a railway, had never left the neighbourhood of his village. We soon met another shepherd on the mountain-side who was just as pleased and interested as the other. And I must say, that wherever I was in Spain, all classes of the population were friendly towards Germans.

It was not long before we encountered other wayfarers who joined us, for Sunday enticed them into the village. My entrance was therefore almost a triumphal procession. We entered the inn, ordered some wine, and sat down to a well-earned rest. When I wanted to pay the landlord, he refused, telling me that Pepa had settled the bill. However, this wouldn’t do. And at last he agreed to my paying on condition that the next time I returned I should be his guest. They all shook hands with me most-heartily and I continued joyfully on my way.

At last I stood in front of the monastery gates. They were opened, and the white haired abbot rode out on a little donkey, holding a green parasol over his head. I saluted the venerable Father and enquired of him whether I could stay at the monastery for the night. “No”, he replied, “impossible.”—Discomfitted I exclaimed: “But where am I to go to-day? I have travelled fifty kilometres and have come from Navalmoral.”—“What, on foot? Impossible!” “Yes, but I have. I am a German and want to see the spot which the emperor Charles V. exchanged for all the crowns in the world, and where he closed his eyes.”—“You are a German? Of course you can’t continue your journey.”

I was most kindly and touchingly taken care of.

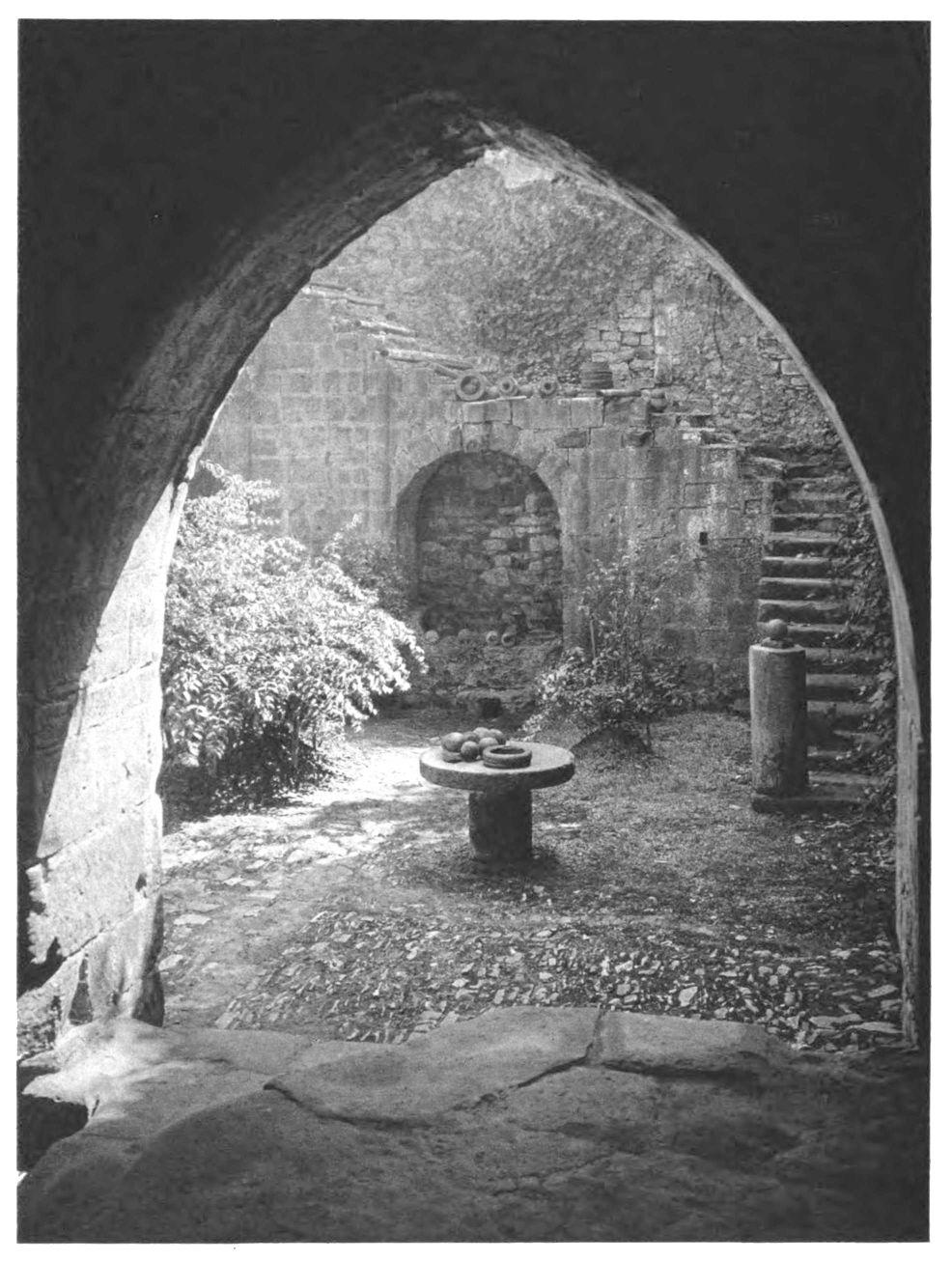

I was shown the monastery which had once been destroyed by the French. Decay and mould have continued the work of destruction. But nature’s eternal youth triumphs victoriously amongst the ruins and beautifies the decay of age. And yet this is a place to think about the everlastingness of all things, of the end of all terrestrial happiness.—Once that great monarch who had fled from the turmoil of the world had paced these halls.

At supper, I, the infidel sat at the monks’ board and was treated like a brother.

The next morning I was awakened long hours before sunrise. A lay brother lit me with a lantern through the dark and ancient park. The monastery gate swung on its hinges, the latch fell heavily, and I was again out in the world all silvery with the moonlight. For a moment I stood entranced.—I heard the mass bell calling the monks to prayers. And the gates of Paradise were closed behind me.

O

The last echoes.—My wanderings through Spain filled me with the joy of life. She had become my second home. It was with a heavy heart that I left.

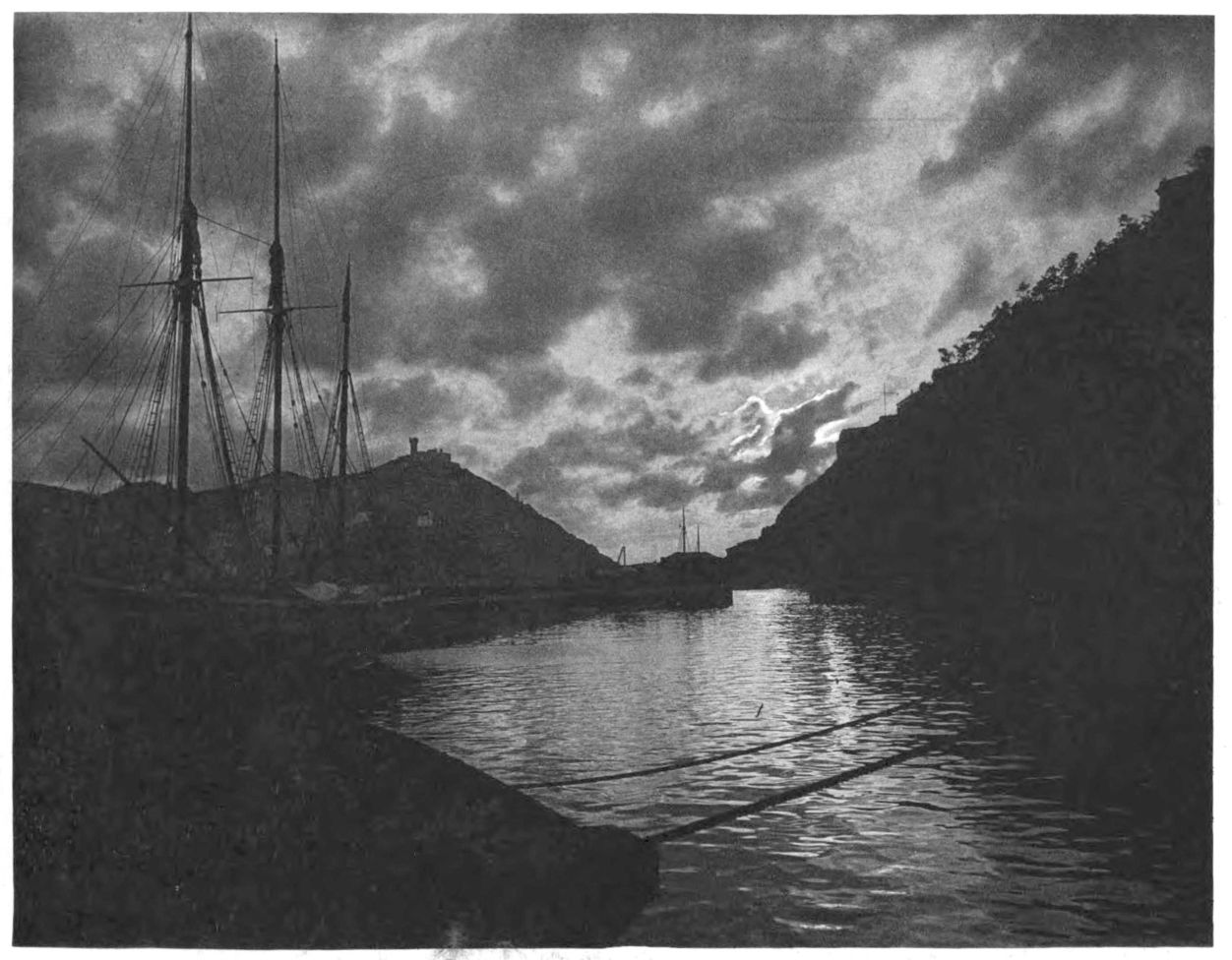

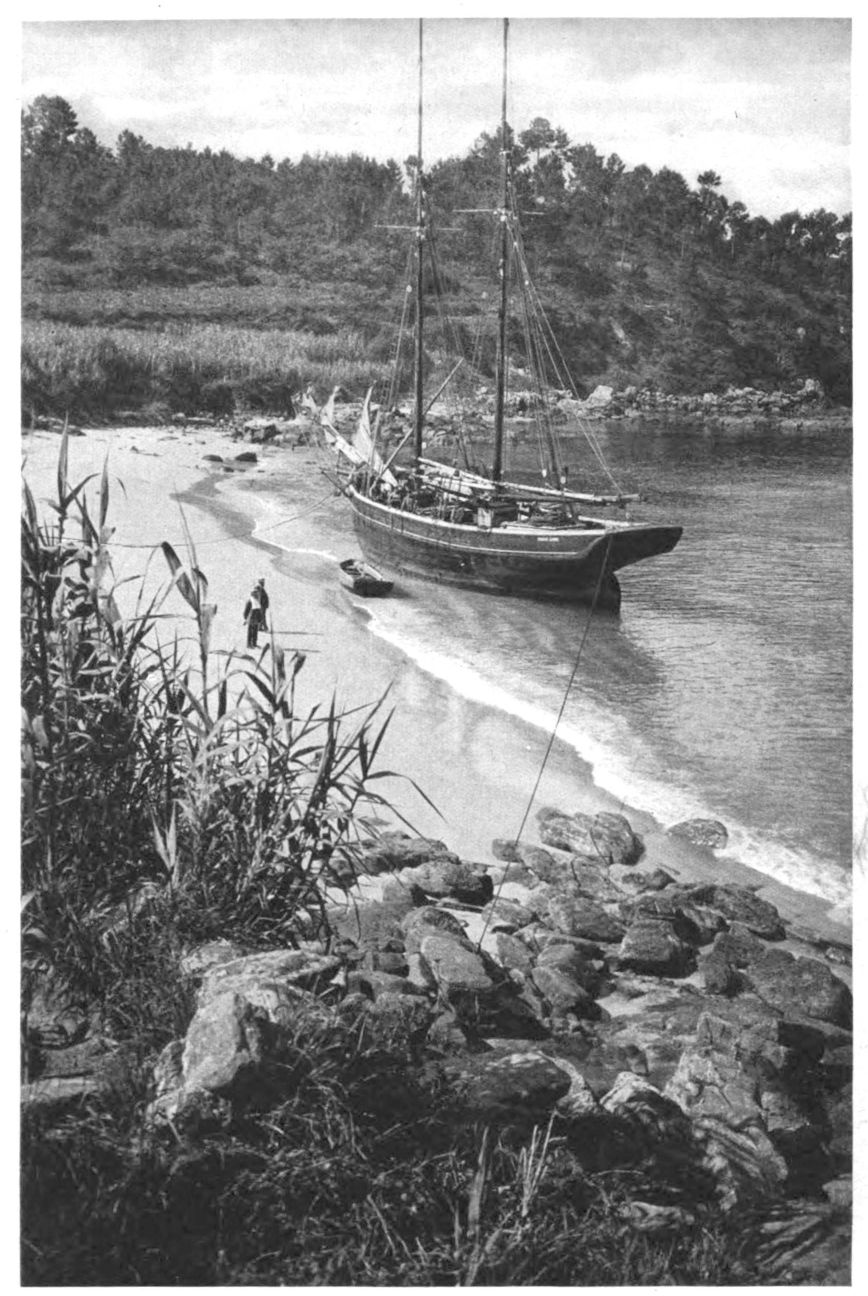

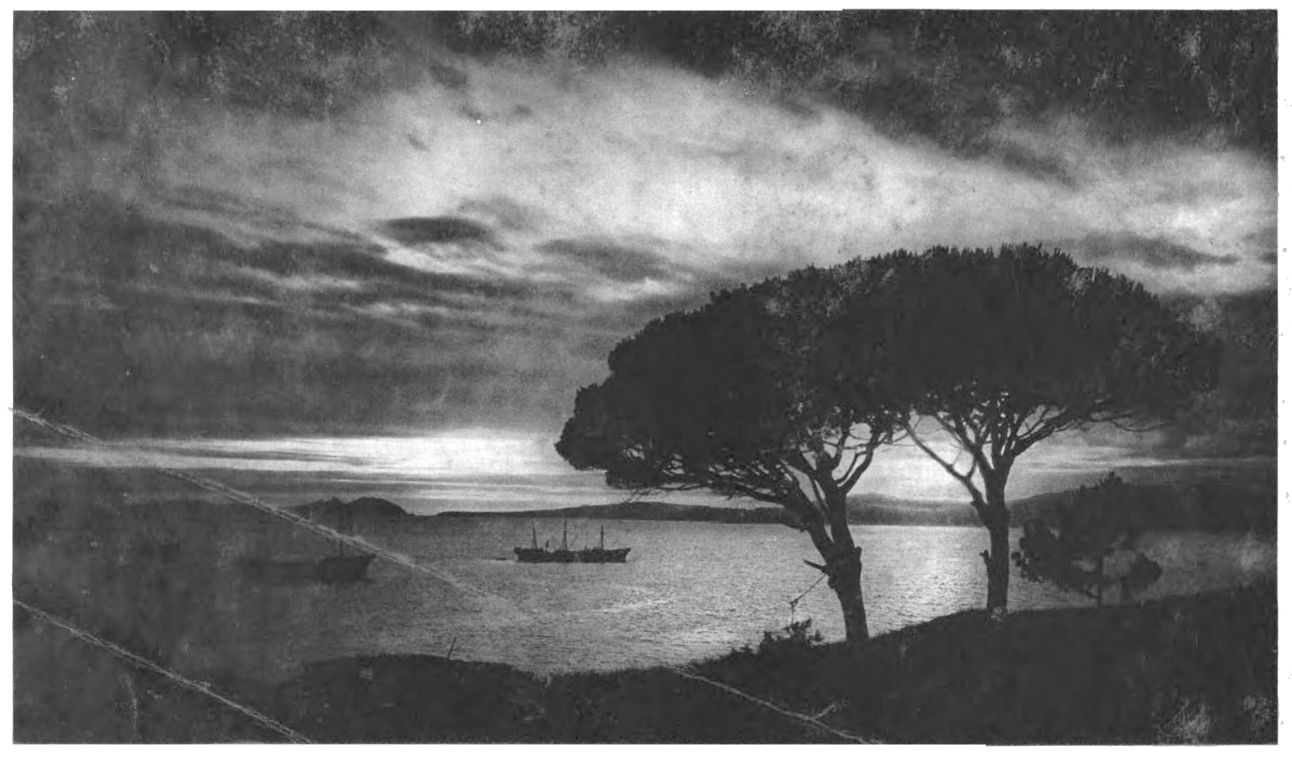

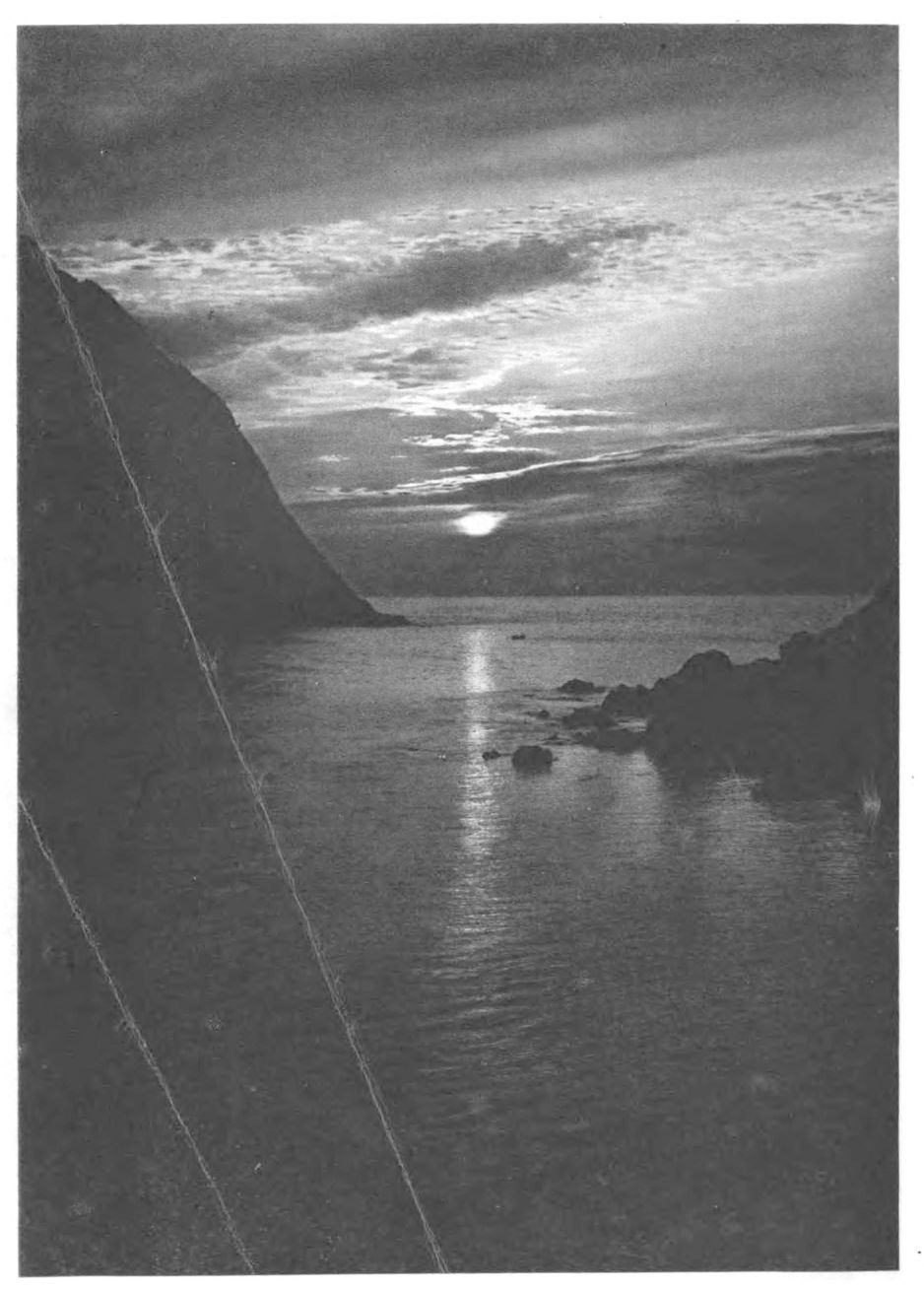

The hour of departure had arrived.—It was a wonderful moonlight night in which the little Spanish steamer which was to bear me homewards sailed slowly out of Ferrol harbour. The moon cast a silver bridge over the water, and along it my thoughts fled back to other moonlight nights when she had often shown me the way in picturesque Spain.

The lights along the coast shone like the eyes of anxious friends looking a last farewell before darkness closed their lids. And then the little ship ploughed homeward through the eternal waters with the eternal sky above us, and the old old song of the waves accompanied me back to my familiar home.

And now that days and weeks of cloudy skies hang heavily over my country where the sun is not so generous as in southern climes, my heart is filled with yearning for Spain, with nostalgia for the sun.—Then I look at my pictures, and we hold converse together, and re-live those unfettered days spent in wanderings in sun-kissed Spain.

In this volume I send forth my sun harvest. May it cast its light in the hearts of many! May it tell of my love of Spain, and of my heartfelt thanks to her chivalrous people for all their kind hospitality!{xxii}

Albarracin 192-194

Albufera 116

Alcala de Guadaira 71

Aldeanueva de la Vera 154

Algatocin 76

Alhambra 1-16, 22

Almazan 227

Alquezar 210-212

Andújar 44, 115

Antequera 64-66

Aranjuez 136-138

Arcos de la Frontera 48, 49, 72

Arranda de Duero 240

Autol 224, 225

Avila 165-169

Barcelona 200

Batuecas 260, 261, 263

Bielsa 213

Bilbao 284

Burgo de Osma 226

Burgos 234-238

Butron 277

Brachimañasee 216

Caceres 83, 84

Candelario 252, 253

Cangas de Onis 274

Carmona 43, 70

Castellbó 208

Castellfullit 204

Cave Dwellings 92-99

Cenaruza 282

Cepeda 155

Chorro 73

Ciudad Rodrigo 250, 251

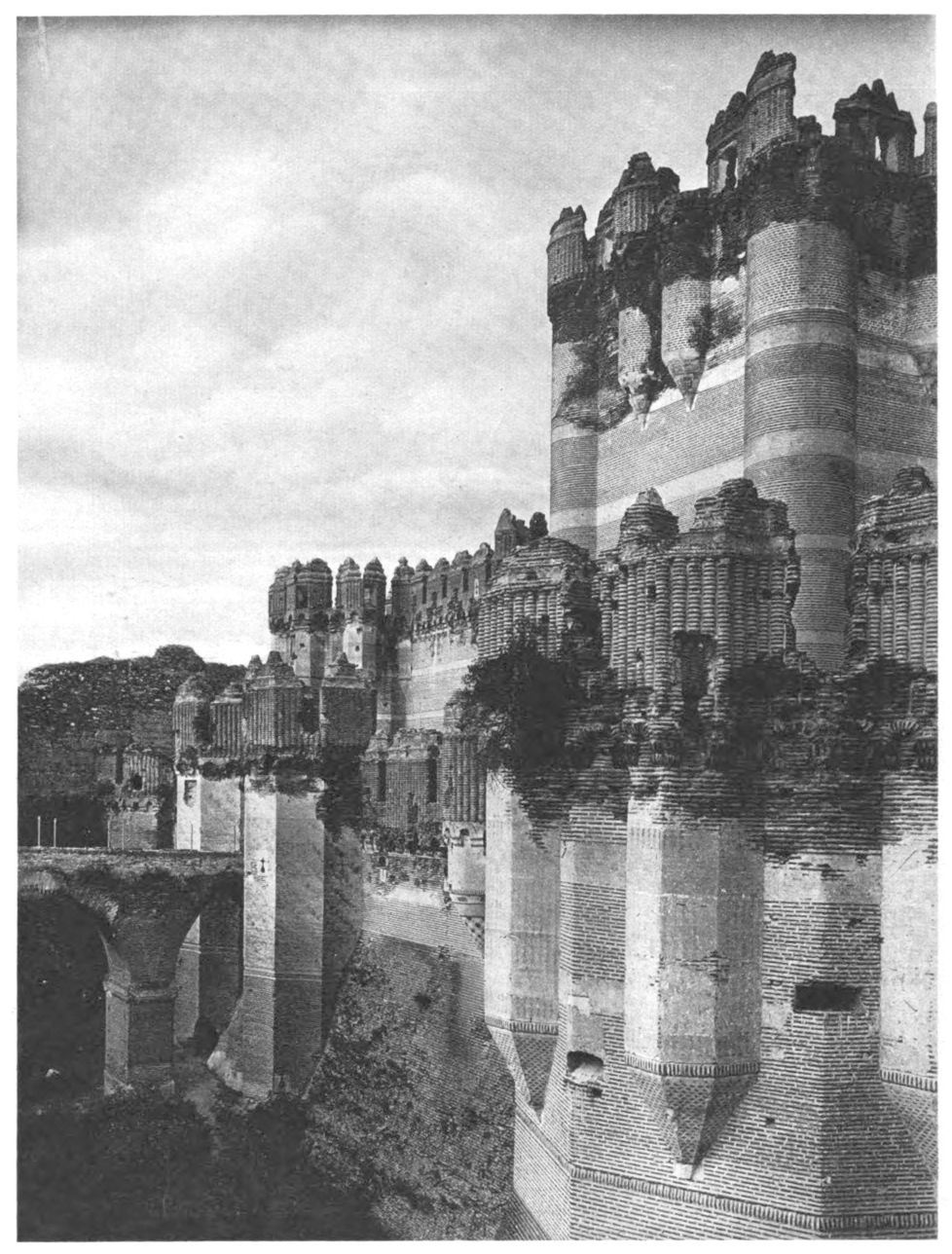

Coca 184-187

Cordoba 50-60

Cuenca 120, 121

Daroca 195-197

Debotes Valley 207

Durango 279, 283

Ecija 68, 69

Elché 101-103

Elorrio 285

Escorial 129-135

Fuenterabia 298

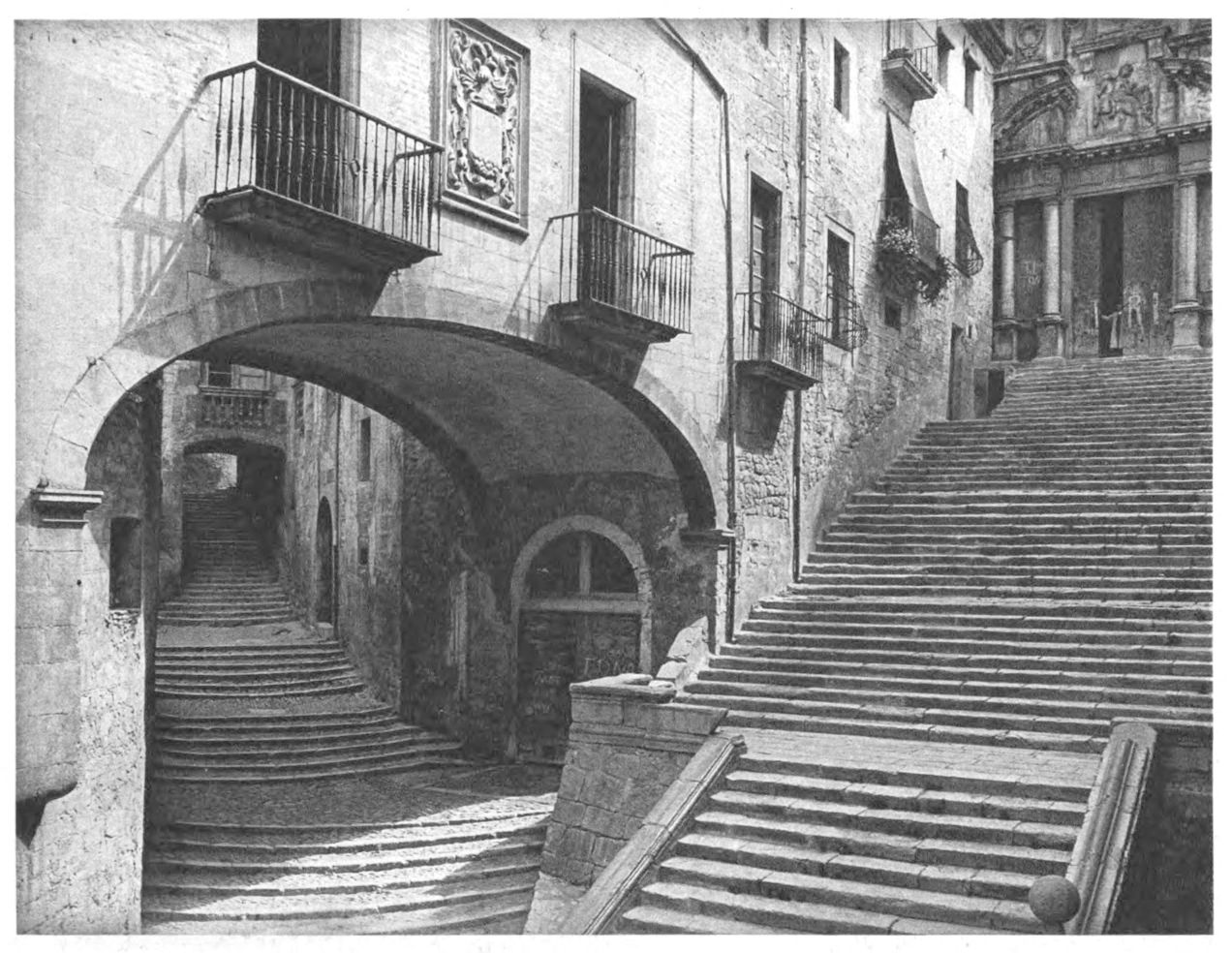

Gerona 202, 203

Granada 1-25

Guadalajara 178-181

Guadalest 118

Guadix 100

Güejar-Sierra 77

Hermida 266

Hurdes 259

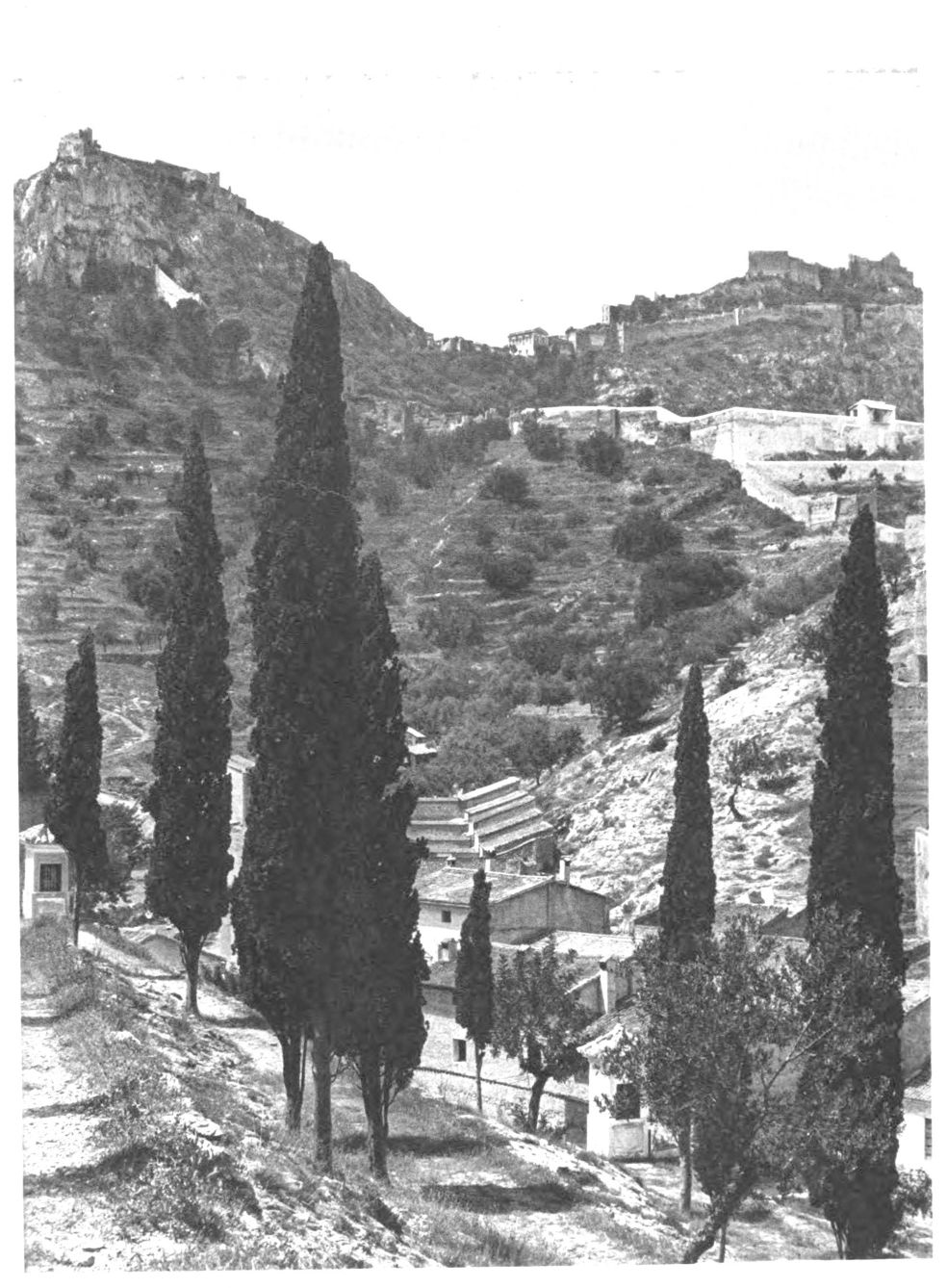

Jativa 111-113

Javea 108

Jerez de la Frontera 67

Jerica 191

La Alberca 254, 256, 257

Lagartera 150, 151

Madrid 126-128

Maladeta 219

Mañaria 278

Manzanera 42

Martos 74, 75

Medinaceli 176, 177

Mochagar 91

Mogarraz 258

Mombeltran 183

Monte Agudo 119

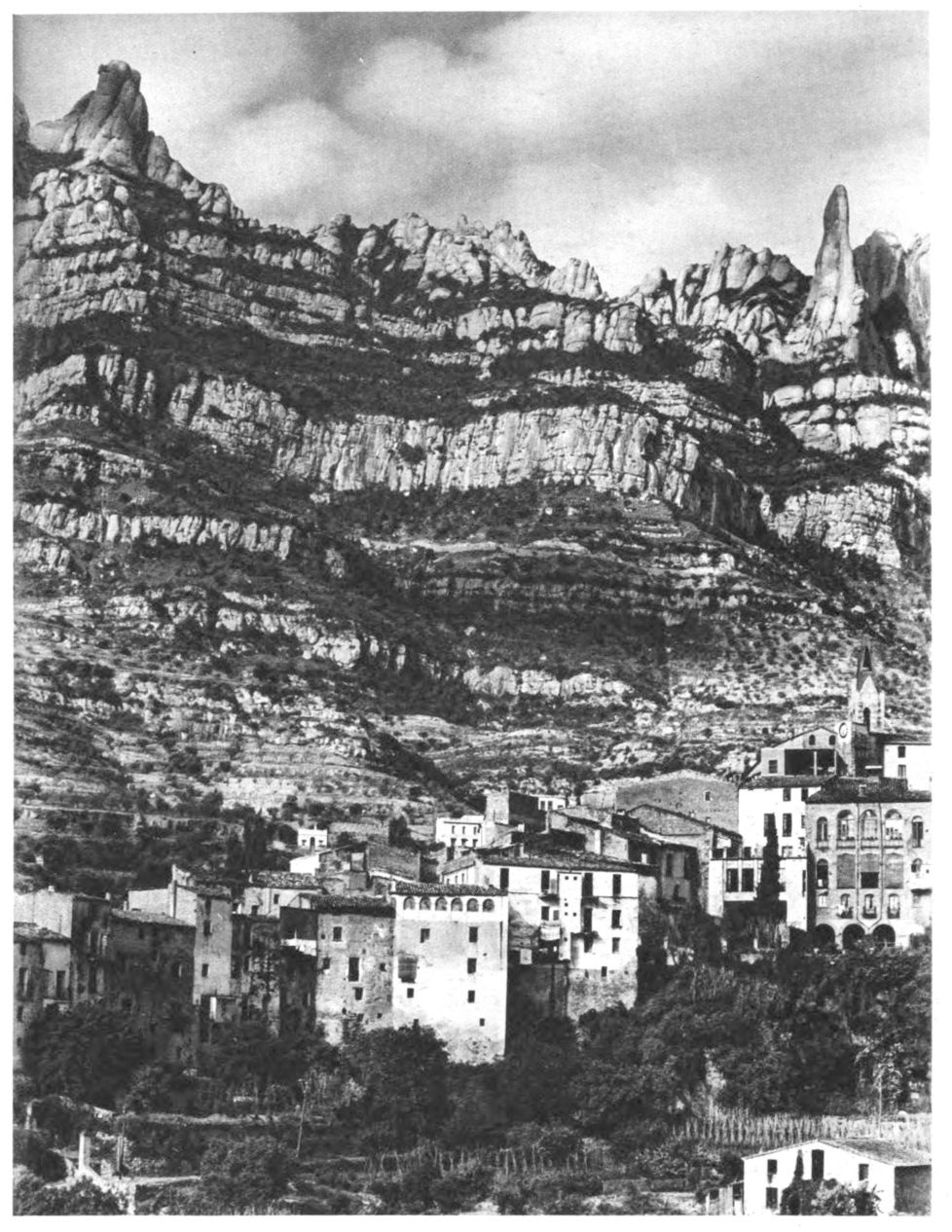

Montserrat 201

Niebla 80, 81

Nuria 206

Ondarroa 276

Orihuela 104-107

Oviedo 264, 265

Pancorbo 231-233

Pasages 291-296, 304

Peñafiel 182

Peña Montañesa 214

Pic de Aneto 217, 218

Pic du midi 216

Picos de Europa 266-274

Pontevedra 301

Potes 270-273

Pyrenees 205-219

Ronda 62, 63

Sagunt 109, 110

Salamanca 246-249

San Esteban de Gormaz 229, 230

San Juan de Plan 209

San Sebastian 286-290

Santander 275

Santiago de Campostela 300

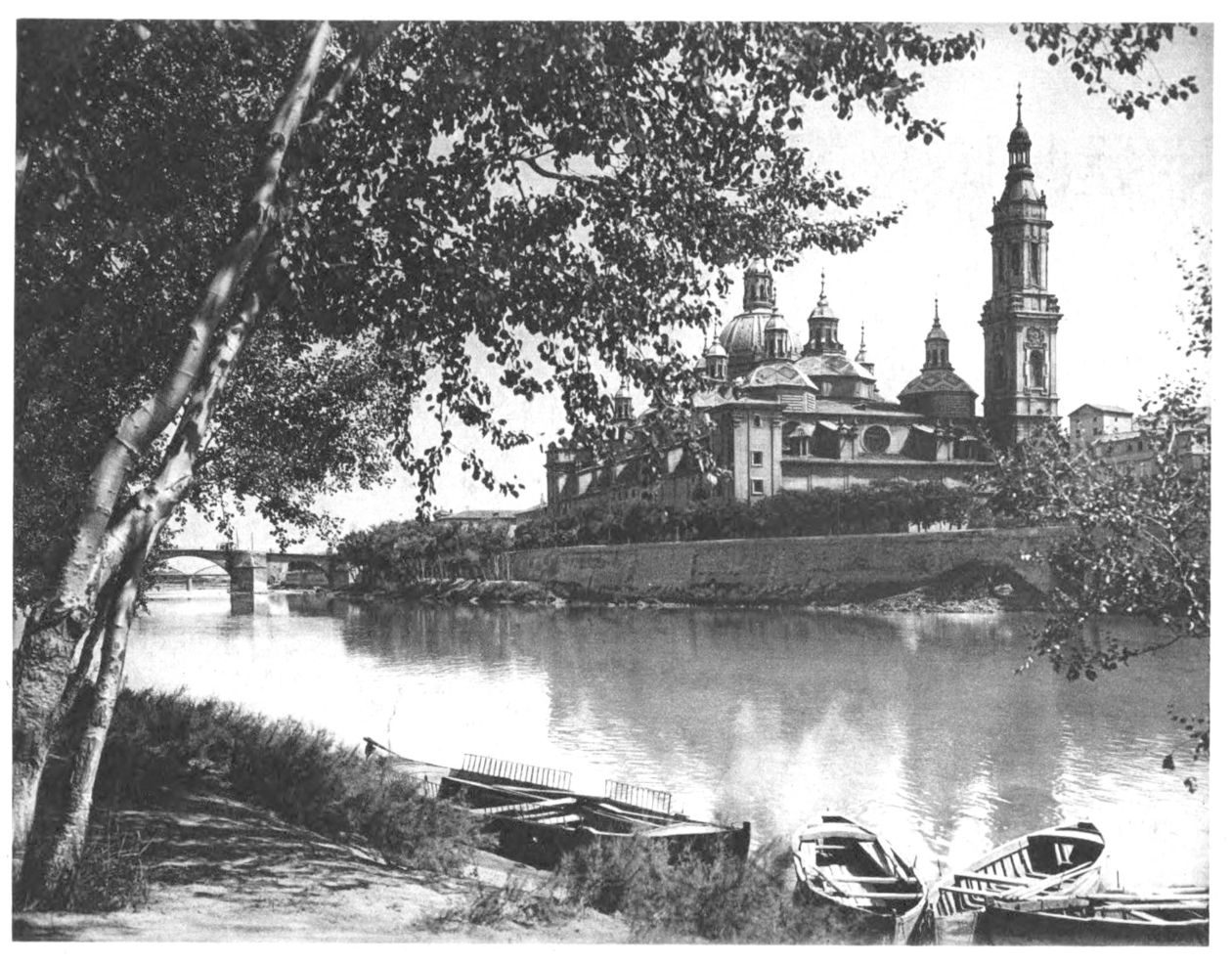

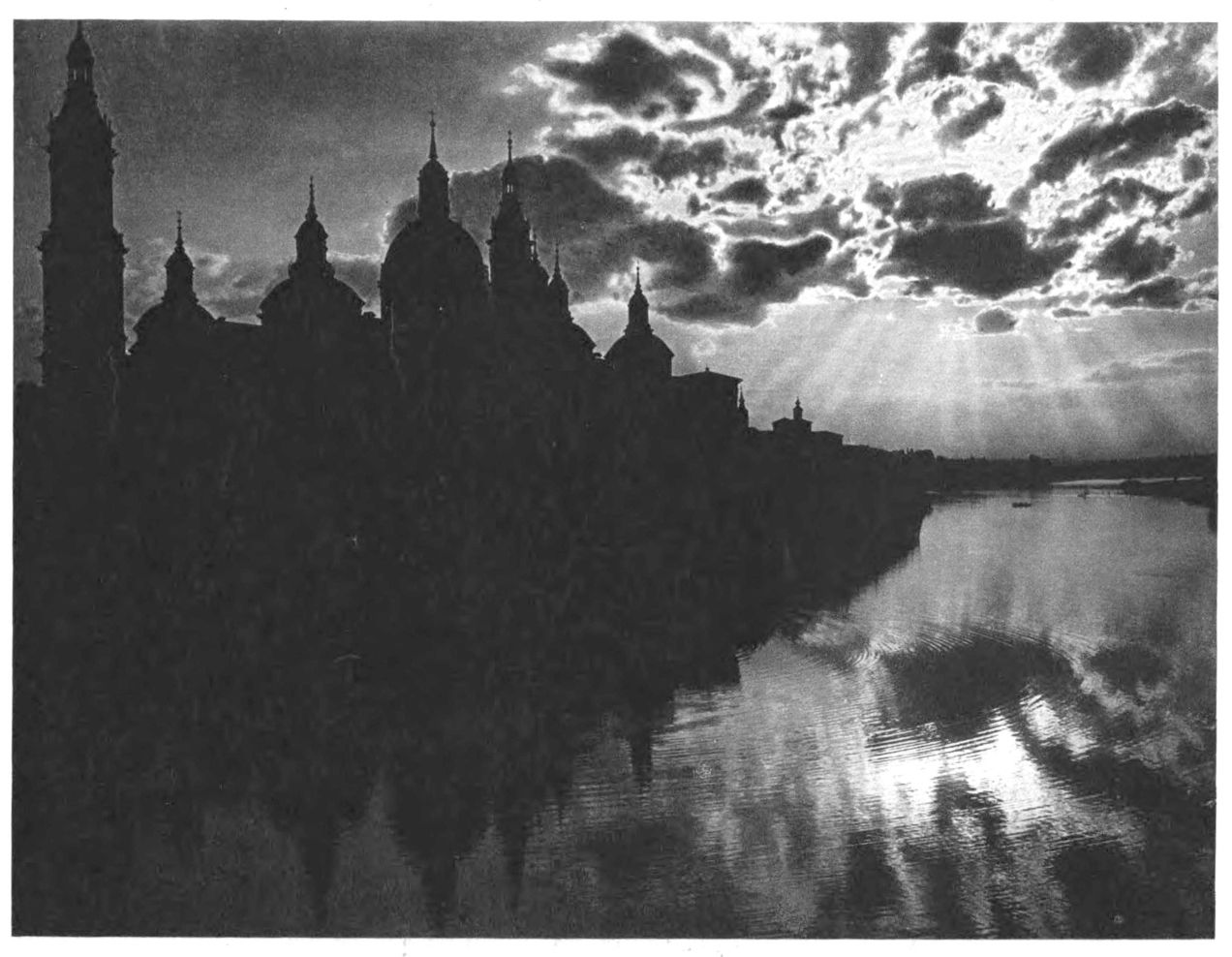

Sarragoza 220, 221

Segovia 157-164

Segretal 205

Sepulveda 172-175

Seville 28-41

Sierra Nevada 79

Sigüenza 188-190

Soria 228

Tarifa 45, 46

Tarazona 223

Tarragona 198, 199

Toledo 139-148

Toro 244

Trujillo 85-87

Turrégano 170, 171

Valencia 114, 117

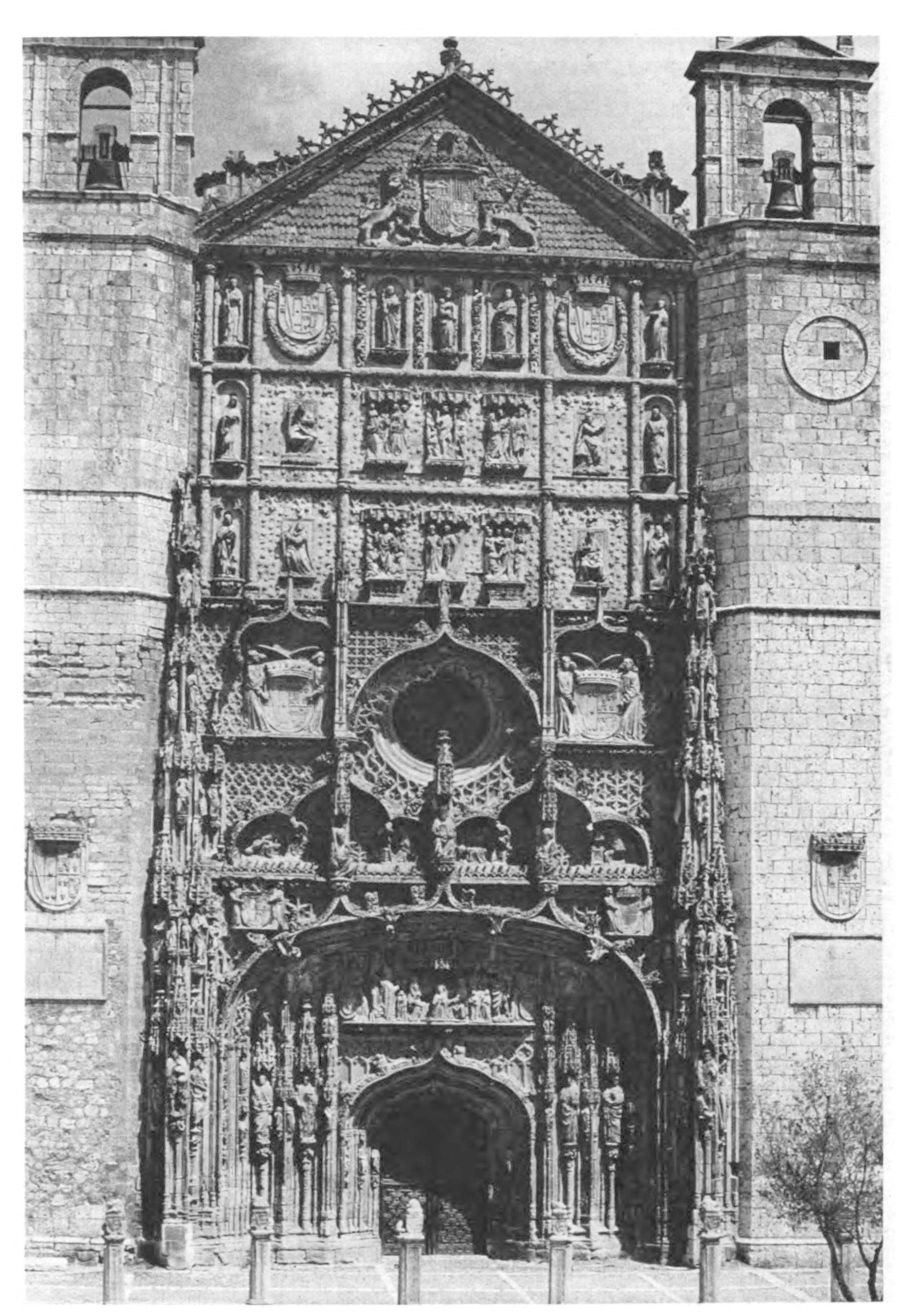

Valladolid 241-243

Vigo 303

Yuste 153

Zafra 82

Zamora 245

Towns: 2, 4, 16, 21, 28, 62-64, 72, 74, 80, 91-99, 120, 128, 139, 157, 166, 172, 191, 192, 195, 202, 204, 210, 223, 226, 227, 232, 246, 276, 286, 287, 290, 293.

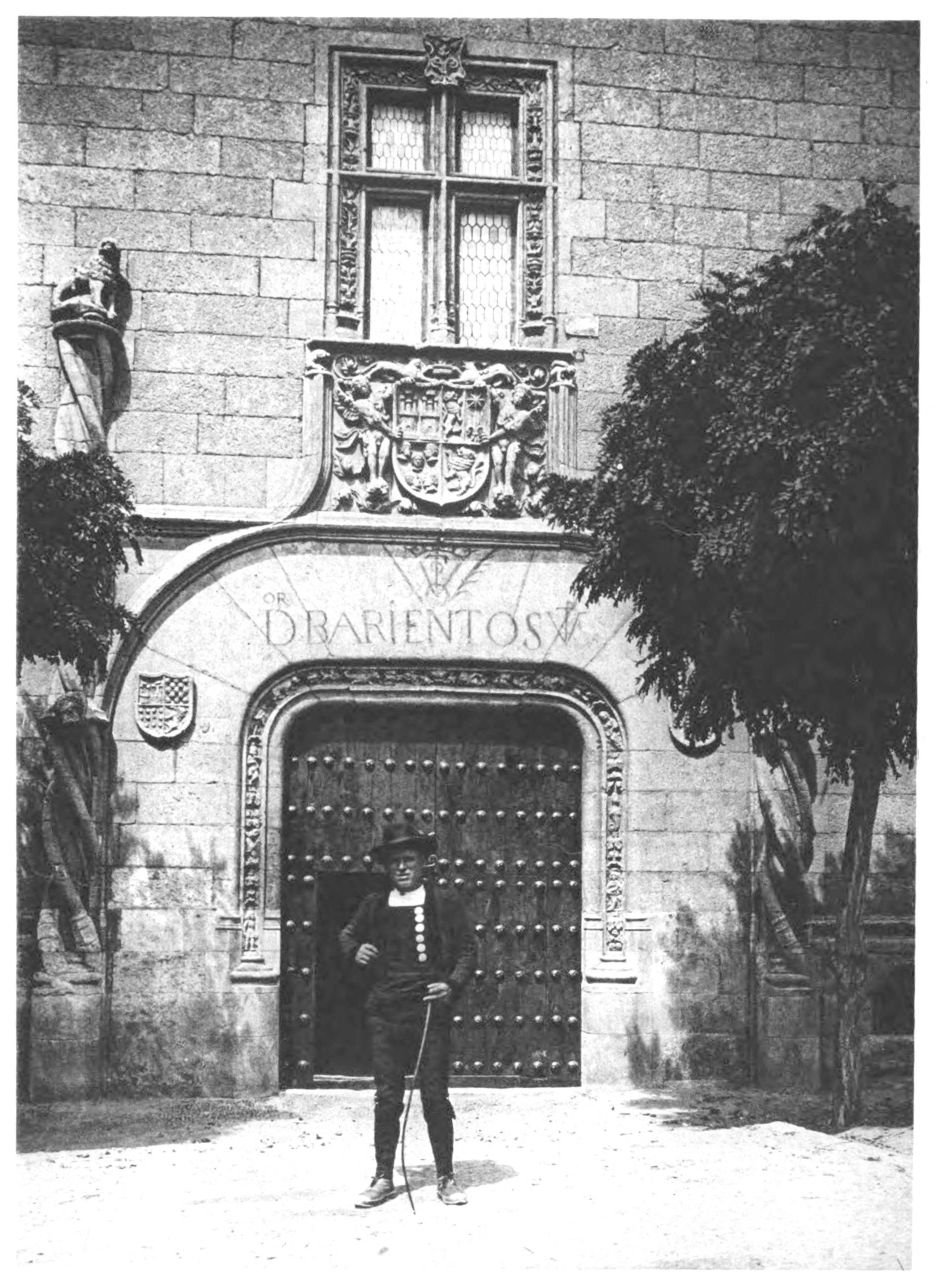

Gateways, Towers, Fortified Walls: 5, 29, 75, 80, 81, 85-87, 143, 167-169, 186-188, 193, 196.

Streets, Squares: 24, 25, 31, 60, 65, 66, 75-77, 83, 85, 86, 147, 148, 154, 155, 163, 170, 173, 174, 175, 176, 189, 190, 193, 197, 198, 203, 208, 209, 211-213, 231-233, 247, 251, 253, 270-273, 278, 295, 296.

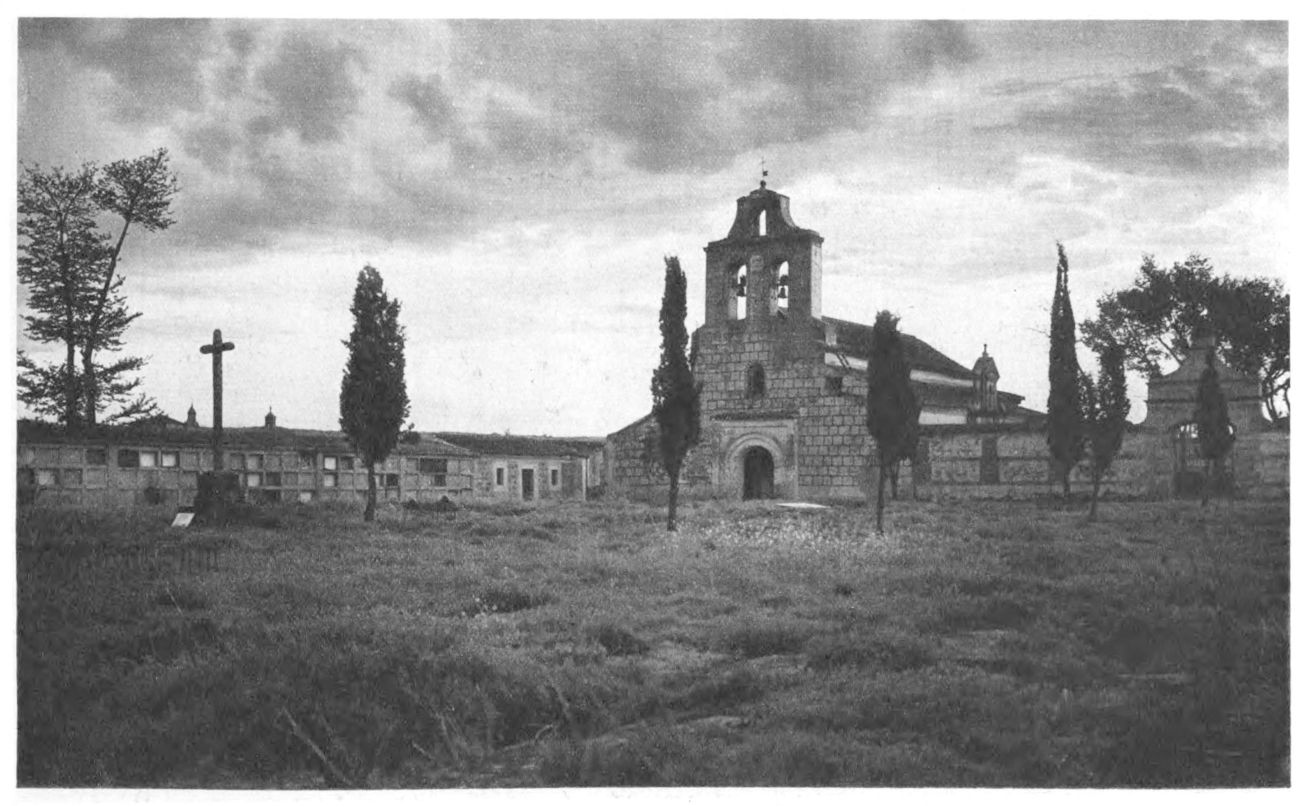

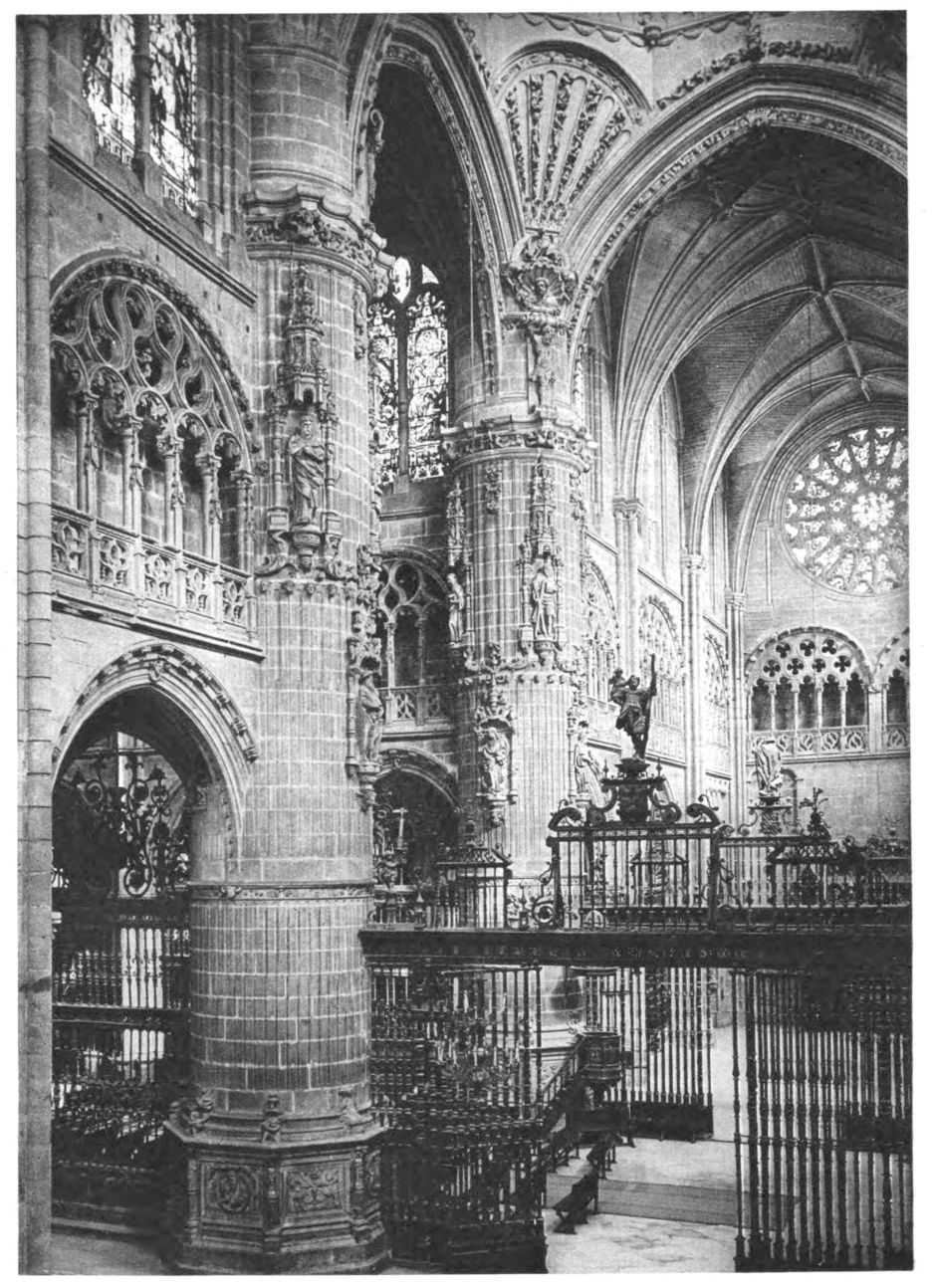

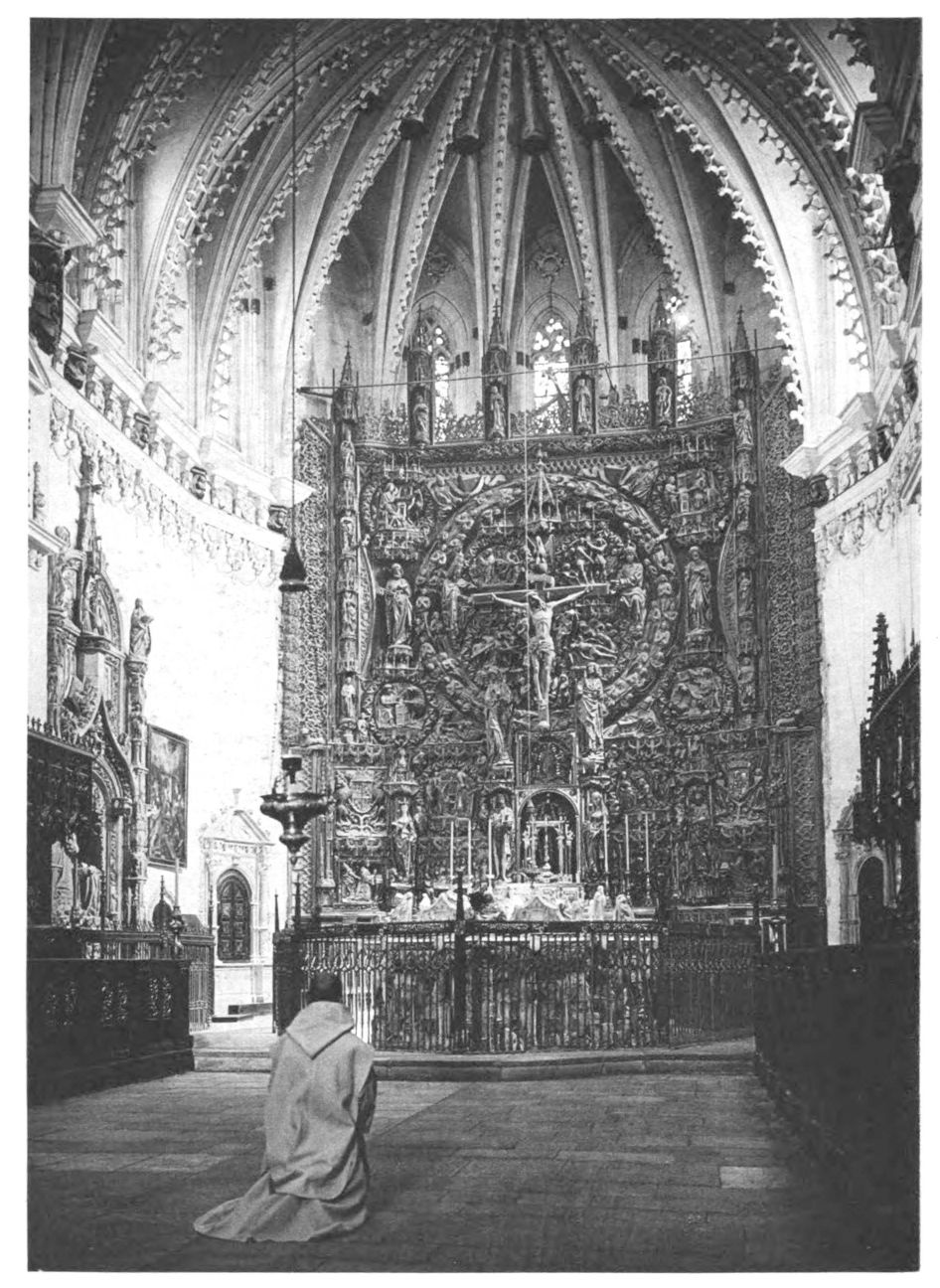

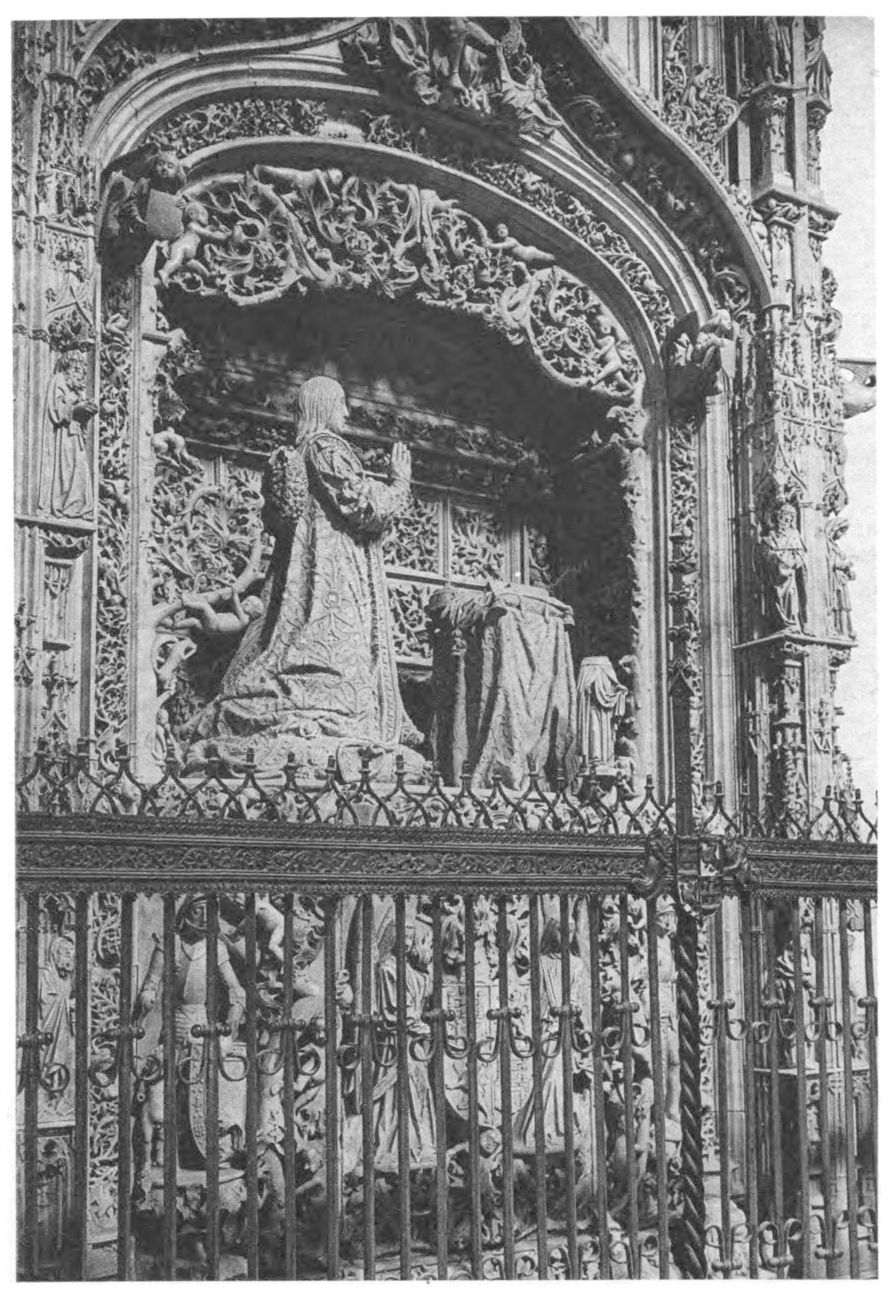

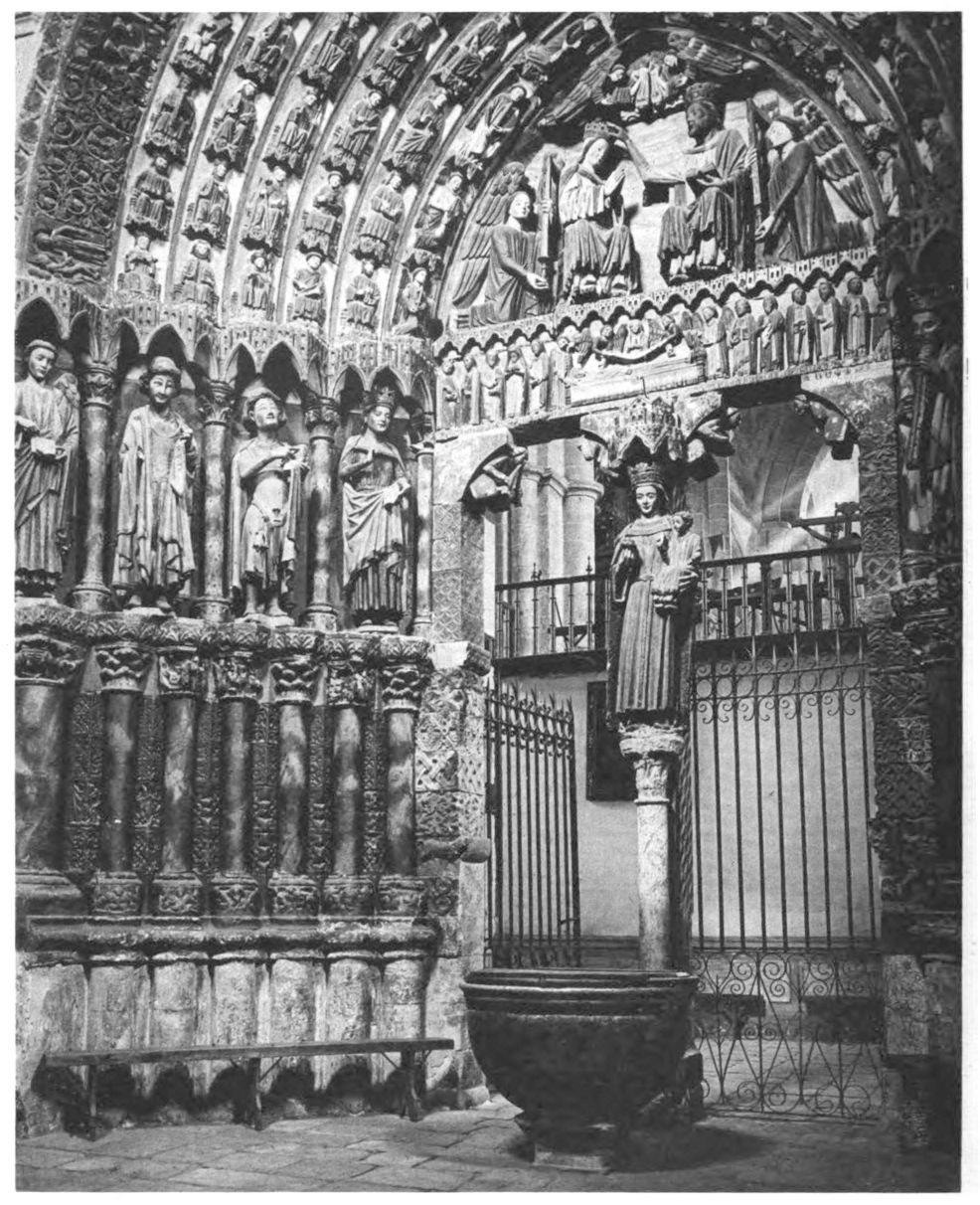

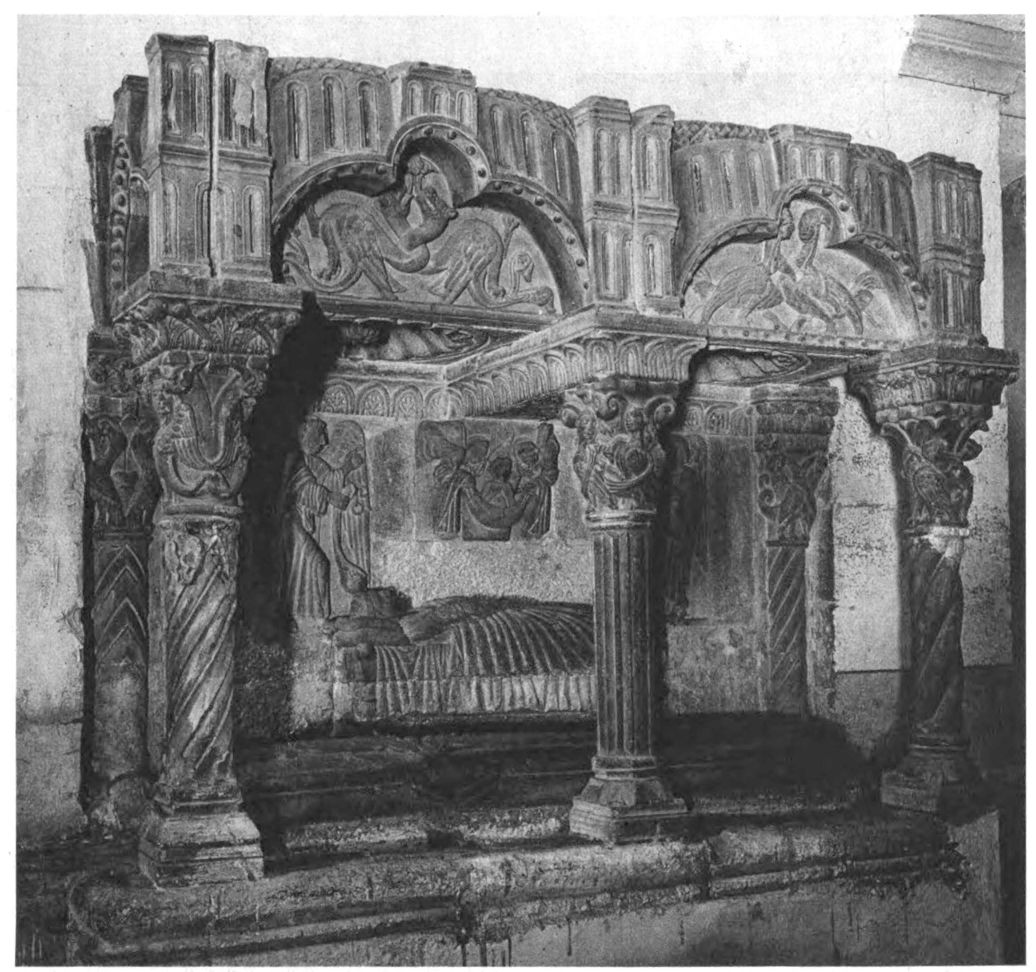

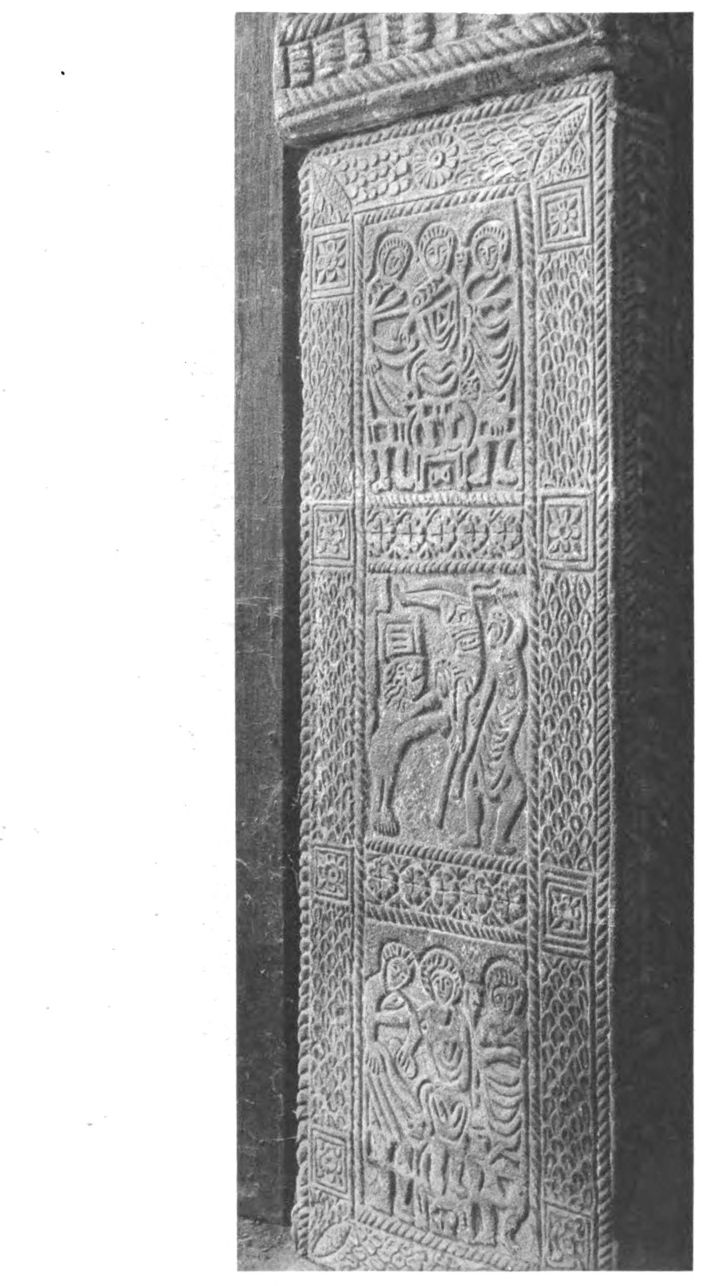

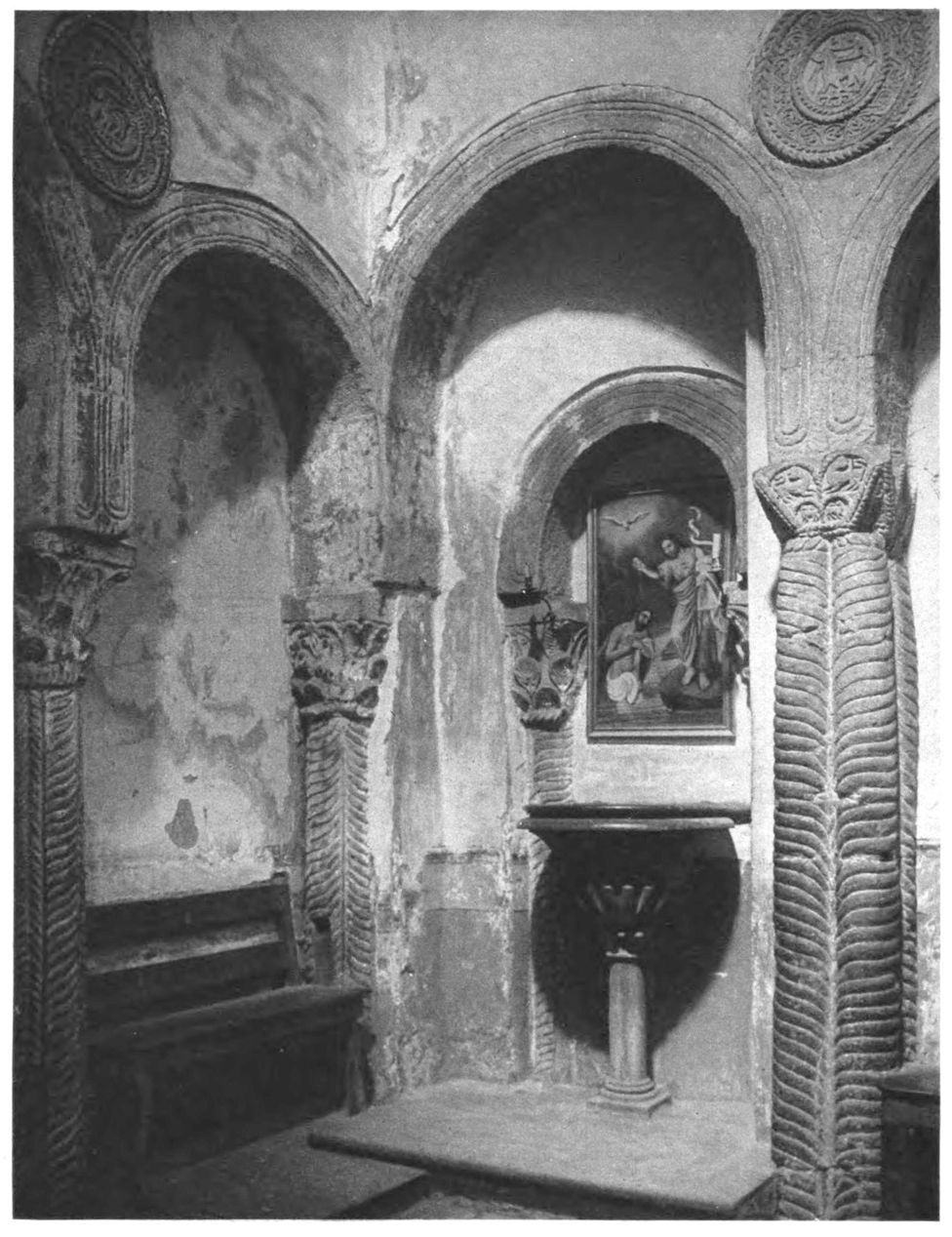

Churches, Convents, Chapels, Cemeteries, etc.: 23, 31, 41, 50-59, 66, 67, 86, 108, 146, 147, 152, 153, 158, 164, 165, 169, 177, 199, 220, 221, 228, 229, 234-241, 244-246, 260-262, 264, 265, 282-285, 300.

Squares, Public Buildings, Typical Houses: 6-15, 17-21, 30, 32, 33, 36-40, 68, 69, 114, 116, 117, 126, 127, 129, 130, 132, 134-137, 144, 162, 178-181, 250, 279, 280, 298.

Courts (Patios) and Gardens: 6-8, 12-15, 17, 34, 35, 37, 40, 42-49, 58, 69, 82, 90, 131, 138, 145, 179-181, 200, 238, 242, 243, 249, 298.

Stairways, Lattice Windows: 39, 68, 115, 144, 200, 203, 248.

Fountains: 9, 12-15, 20, 37, 49, 60, 197, 232.

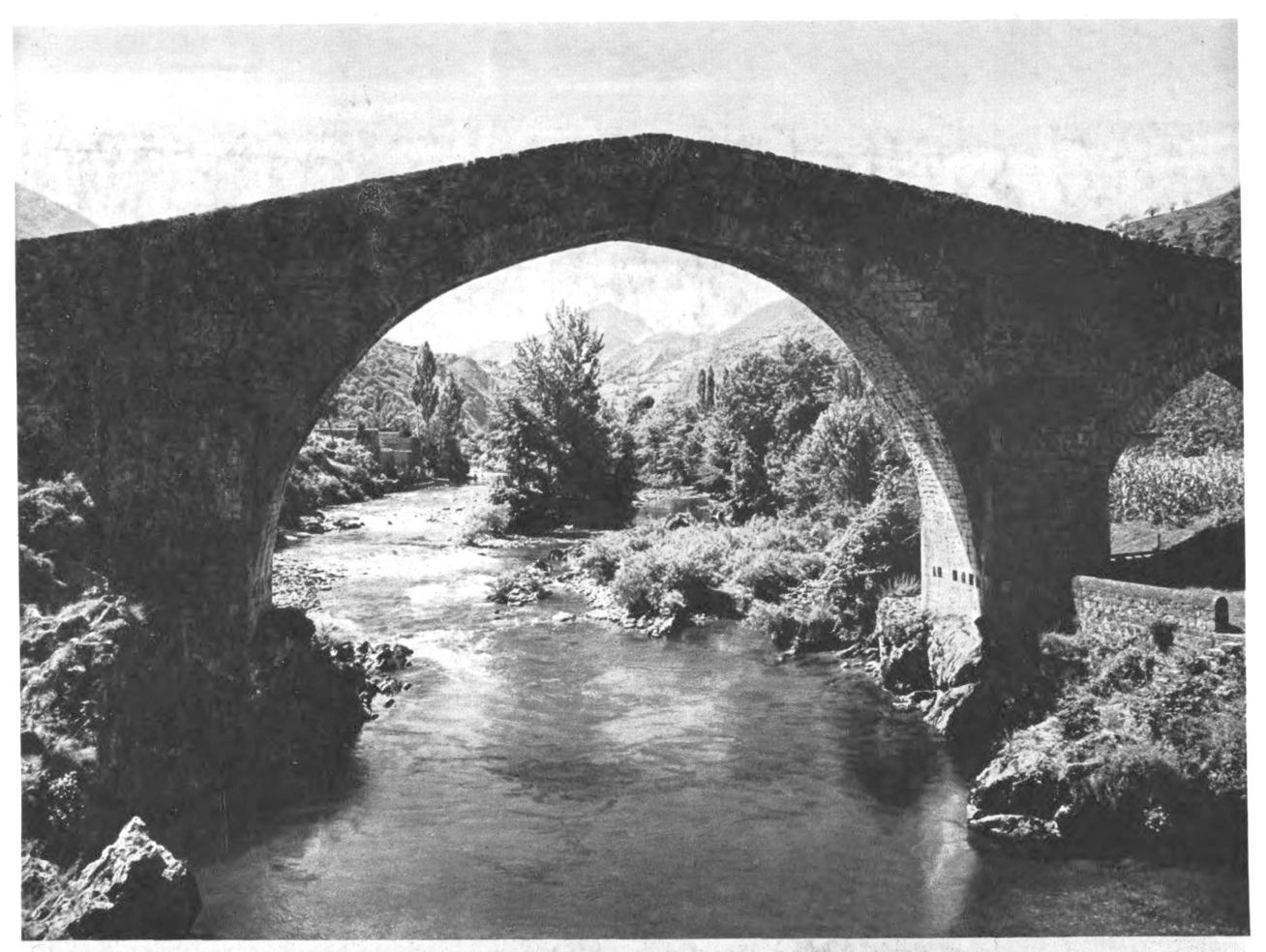

Bridges: 63, 140-143, 268, 270, 274, 276.

Castles (Castillos): 1-5, 22, 70, 71, 110-112, 118, 119, 141, 161, 170, 171, 182-186, 277.

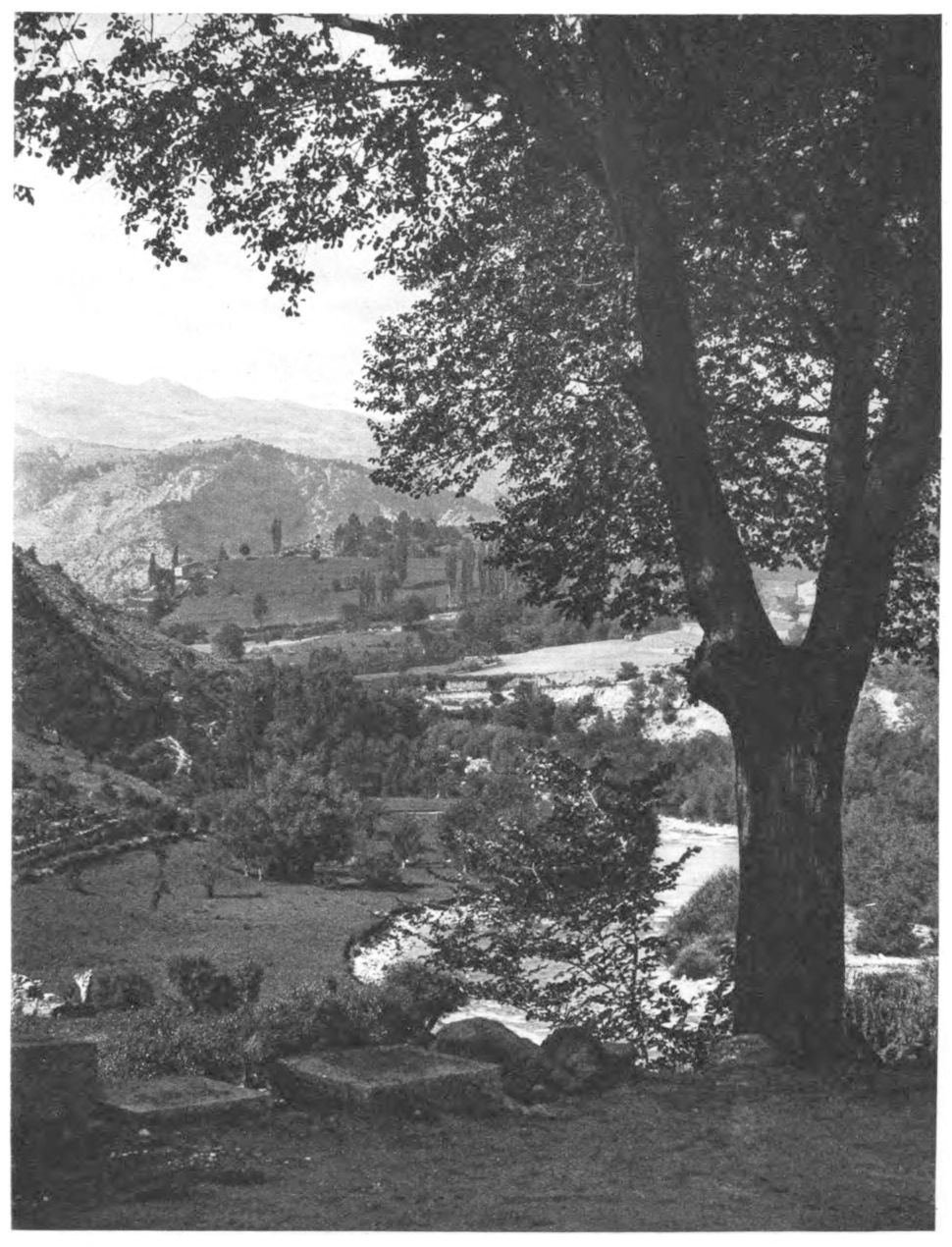

Views of Landscapes: 2-4, 21, 62, 63, 72, 73, 79, 88, 92-99, 101-107, 113, 116, 194, 201, 204-207, 214-219, 224, 225, 230, 260, 263, 266-269, 274, 275, 286-289, 291, 292, 294, 299, 301-304.

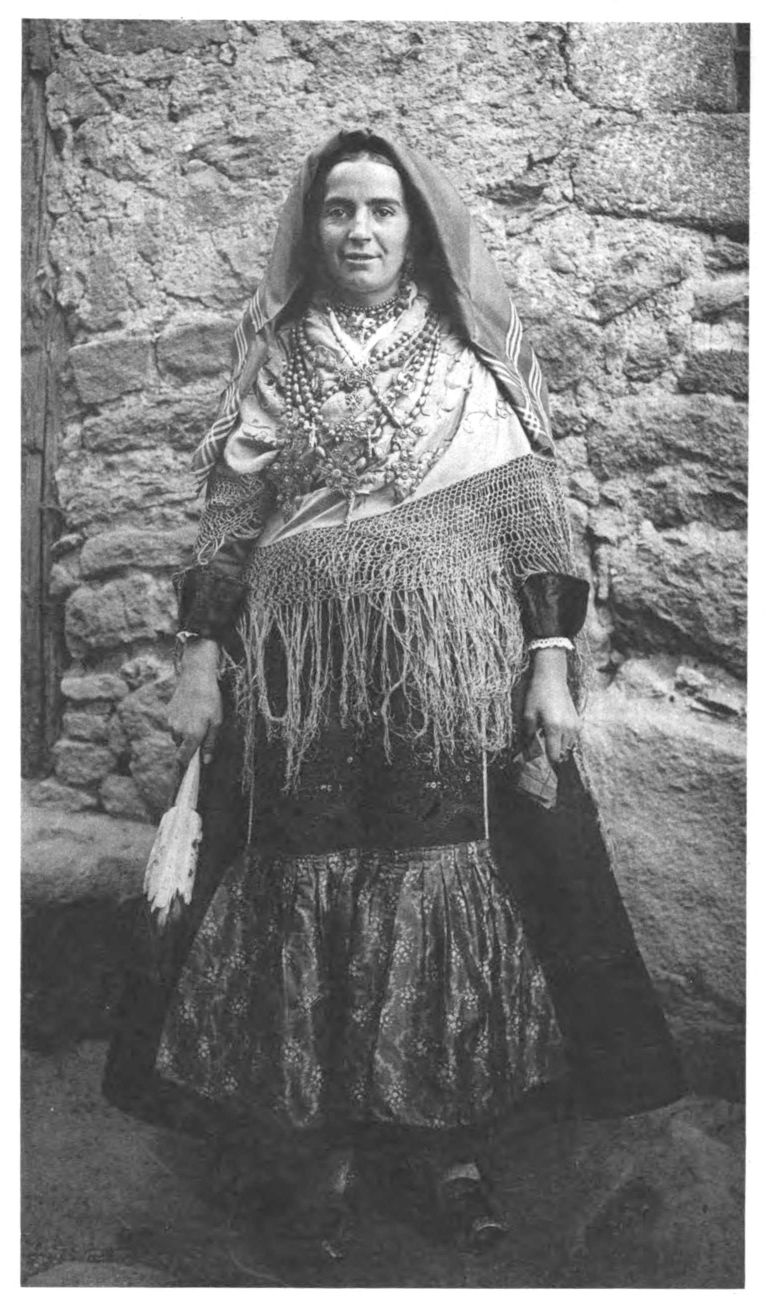

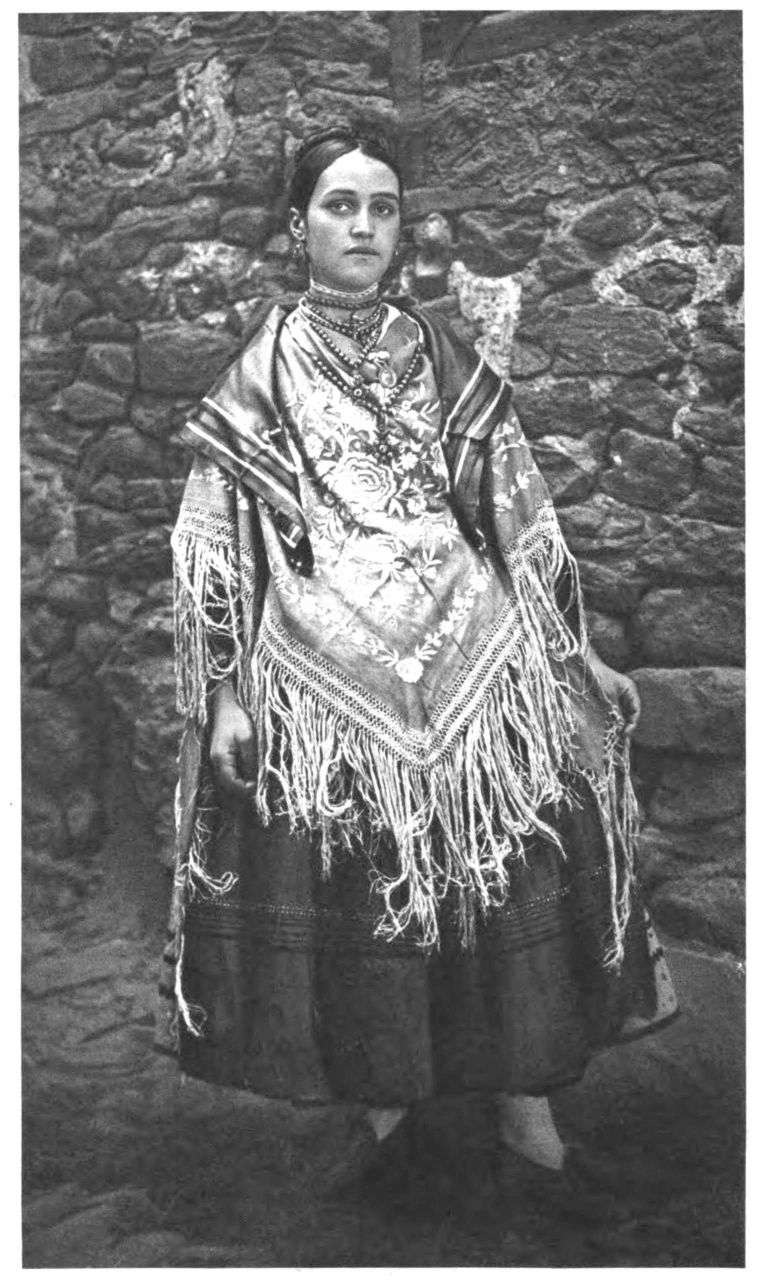

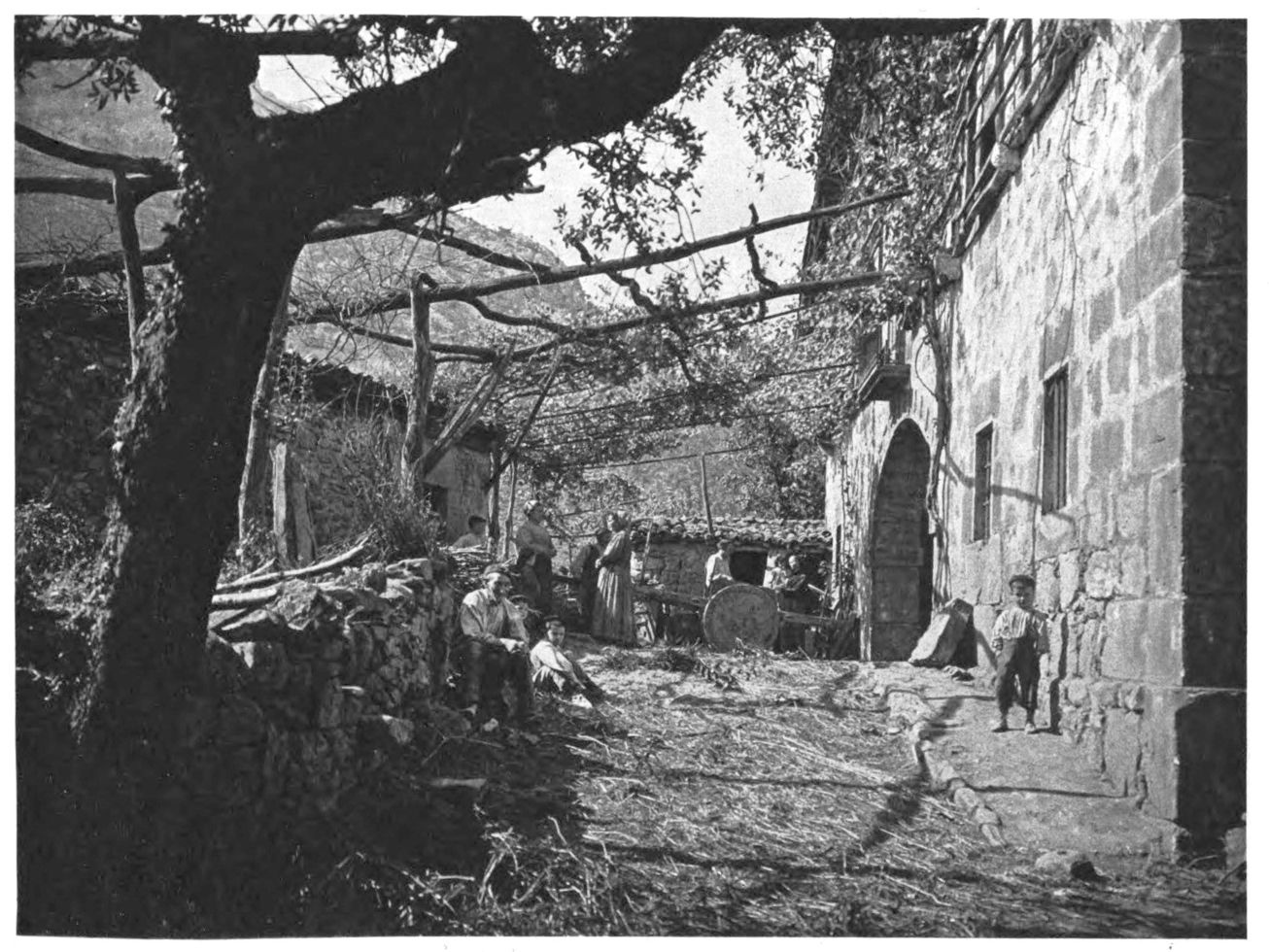

Costumes and Life of the People: 26, 27, 61, 78, 84, 90, 122-125, 149, 150, 151, 155, 156, 160, 174, 175, 222, 252, 254-259, 262, 281, 296, 297.

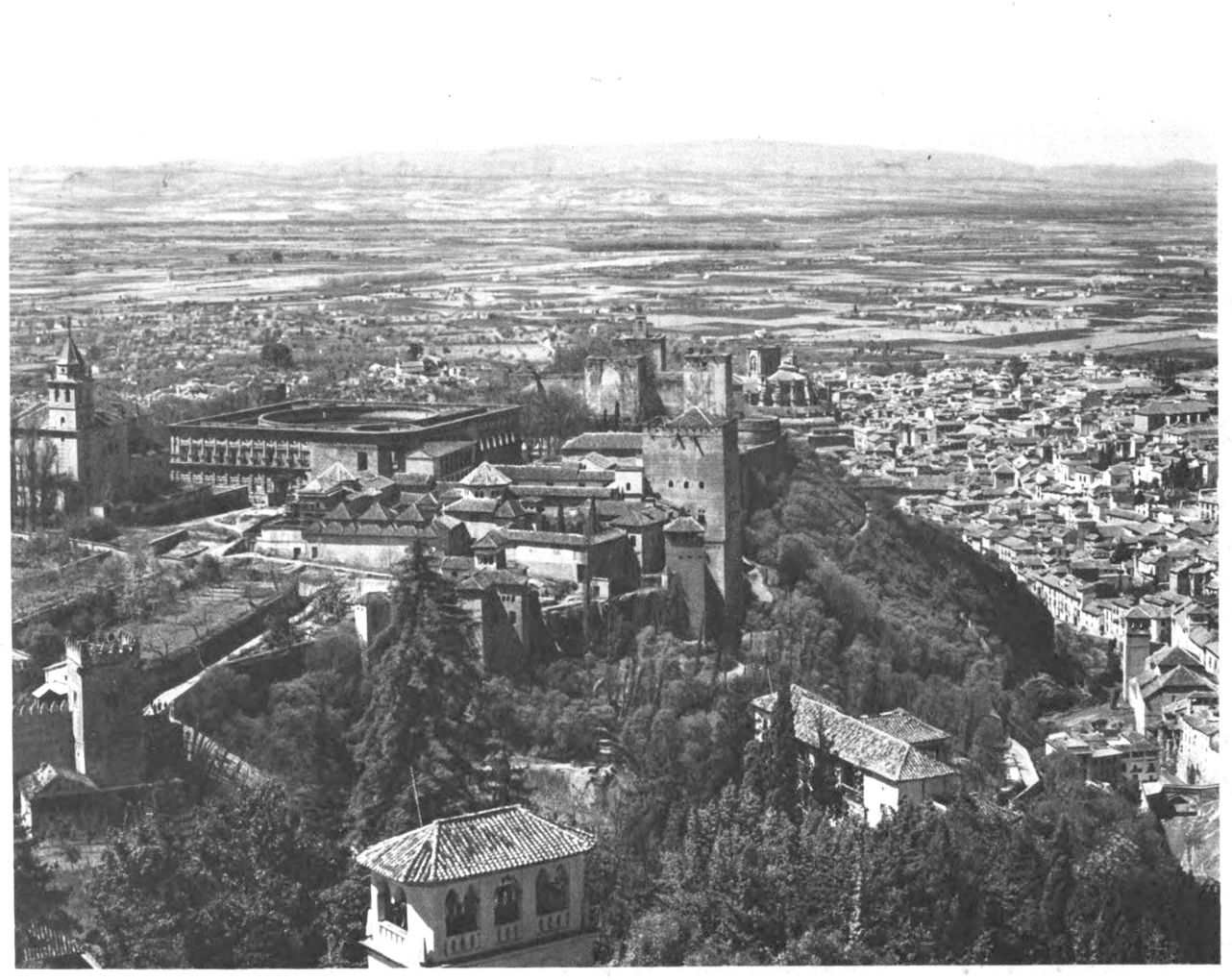

Granada

Alhambra and the Vega

Alhambra y la Vega

Alhambra und die Vega

Vue de l’Alhambra et la Vega

L’Alambra e la Vega

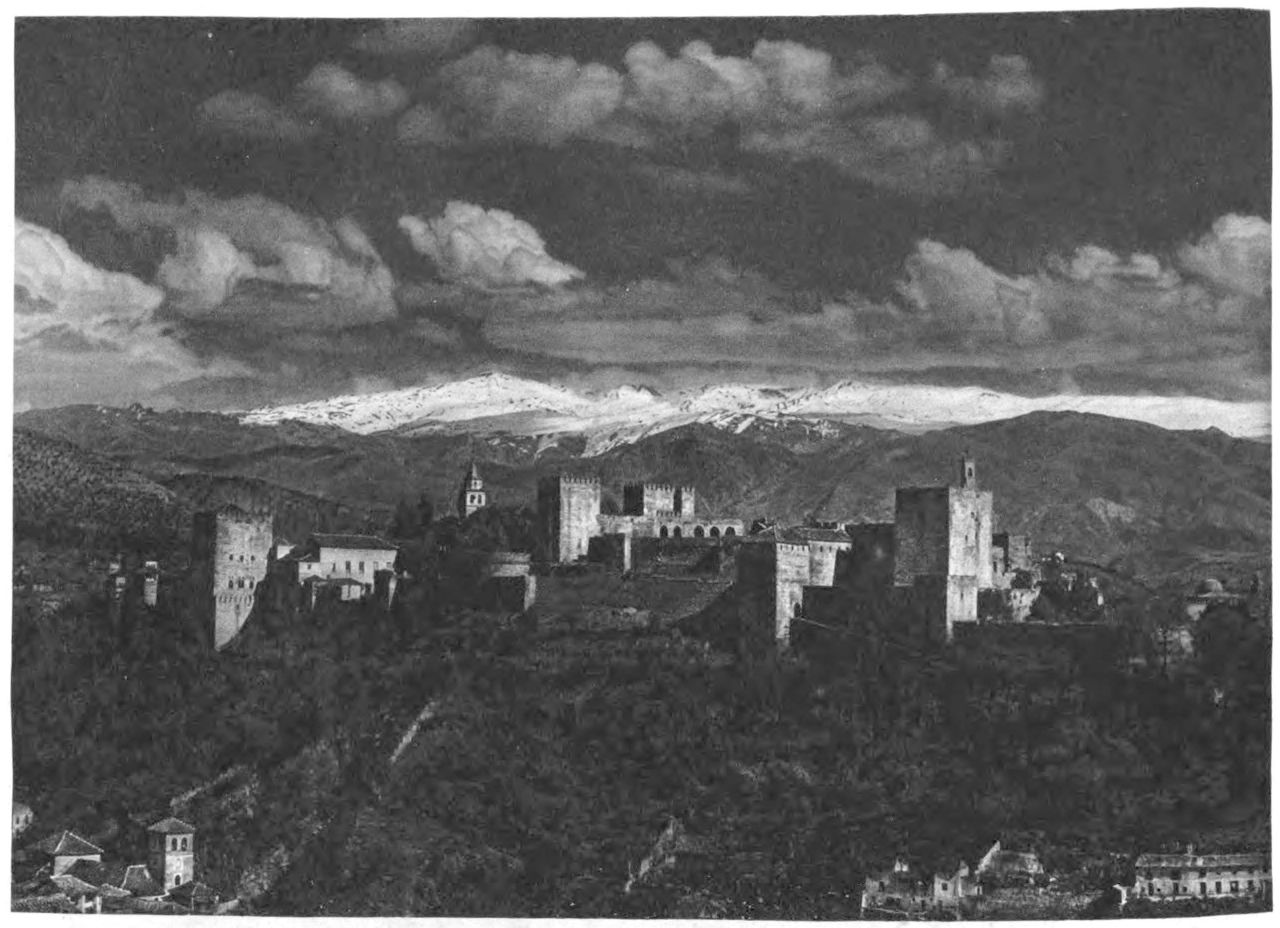

Granada

Alhambra—In the background the Sierra Nevada

Alhambra-Puesta del sol: En el fondo la Sierra Nevada

Alhambra-Abendstimmung: im Hintergrund die Sierra Nevada

Le soir à Grenade: au fond la Sierra Nevada

L’Alambra sul tramonto: In fondo la Sierra Nevada

Granada

The Alhambra Towers

Torres de la Alhambra

Alhambratürme

Les tours de l’Alhambra

I torrioni dell’Alambra

Granada-Alhambra

The Myrtle Court

Patio de los Arrayanes

Myrtenhof

La cour des myrtes

La corte dei mirti

Granada-Alhambra

The Myrtle Court

Patio de los Arrayanes

Myrtenhof

La cour des myrtes

La corte dei mirti

Granada-Alhambra

The Court of the Lions

Patio de los Leones

Löwenhof

La cour des Lions

La corte dei leoni

Granada-Alhambra

The Lion Fountain in the Court of the Lions

La fuente en el patio de los Leones

Der Löwenbrunnen im Löwenhof

La Fontaine avec le bassin dans la cour des Lions

La fontana del leoni nella Corte omonima

Granada-Alhambra

Court of Justice

Sala de la Justicia

Gerichtshalle

La salle de Justice

La sala della Giustizia

Granada-Alhambra

Bay Windows of the Daraxa

Le pavillion de la Daraxa

Erker der Daraxa

Mirador de Daraxa

Il padiglione di Daraxa

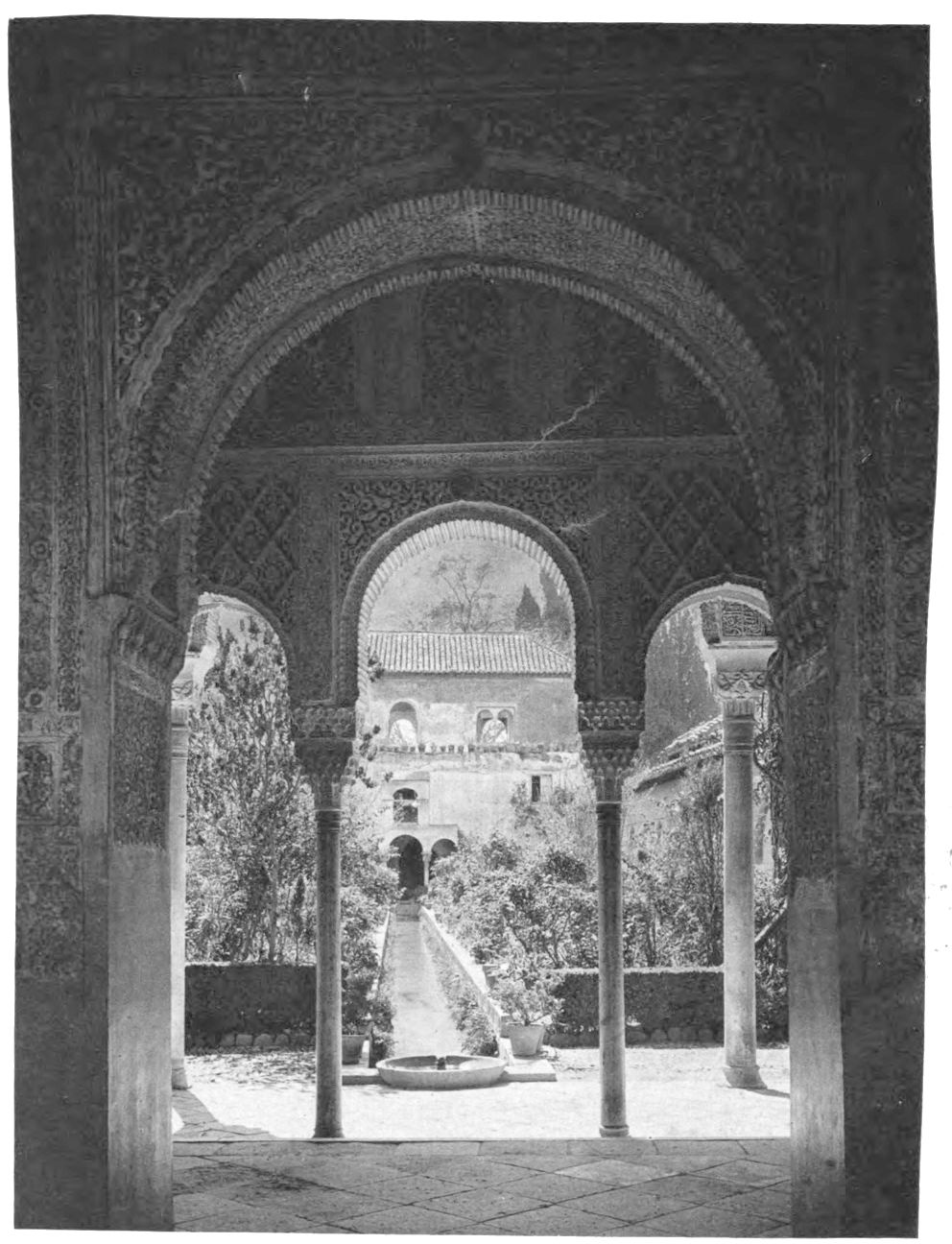

Granada-Alhambra

The Daraxa Court

Un coin du jardin de la Daraxa

Gartenhof der Daraxa

Patio de Daraxa

Il giardino di Daraxa

Granada-Alhambra

The Daraxa Court

Un coin du jardin de la Daraxa

Gartenhof der Daraxa

Patio de Daraxa

Il giardino di Daraxa

Granada-Alhambra

In the Daraxa Garden

Patio de Daraxa

Im Garten der Daraxa

Dans le jardin de la Daraxa

Il giardino di Daraxa

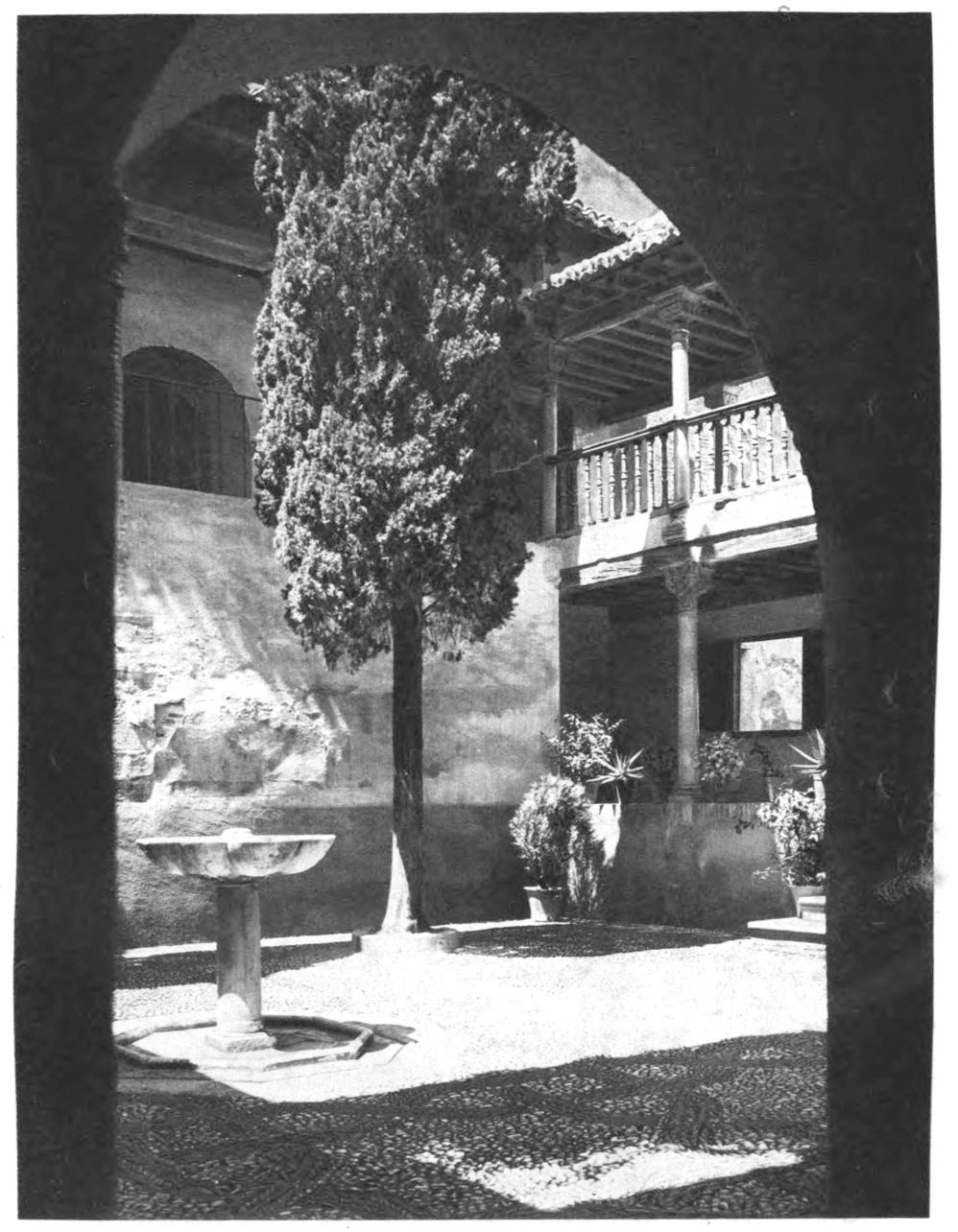

Granada-Alhambra

The Cypress Court

Patio de los cipreses

Zypressenhof

La cour des cyprès

Il cortile dei cipressi

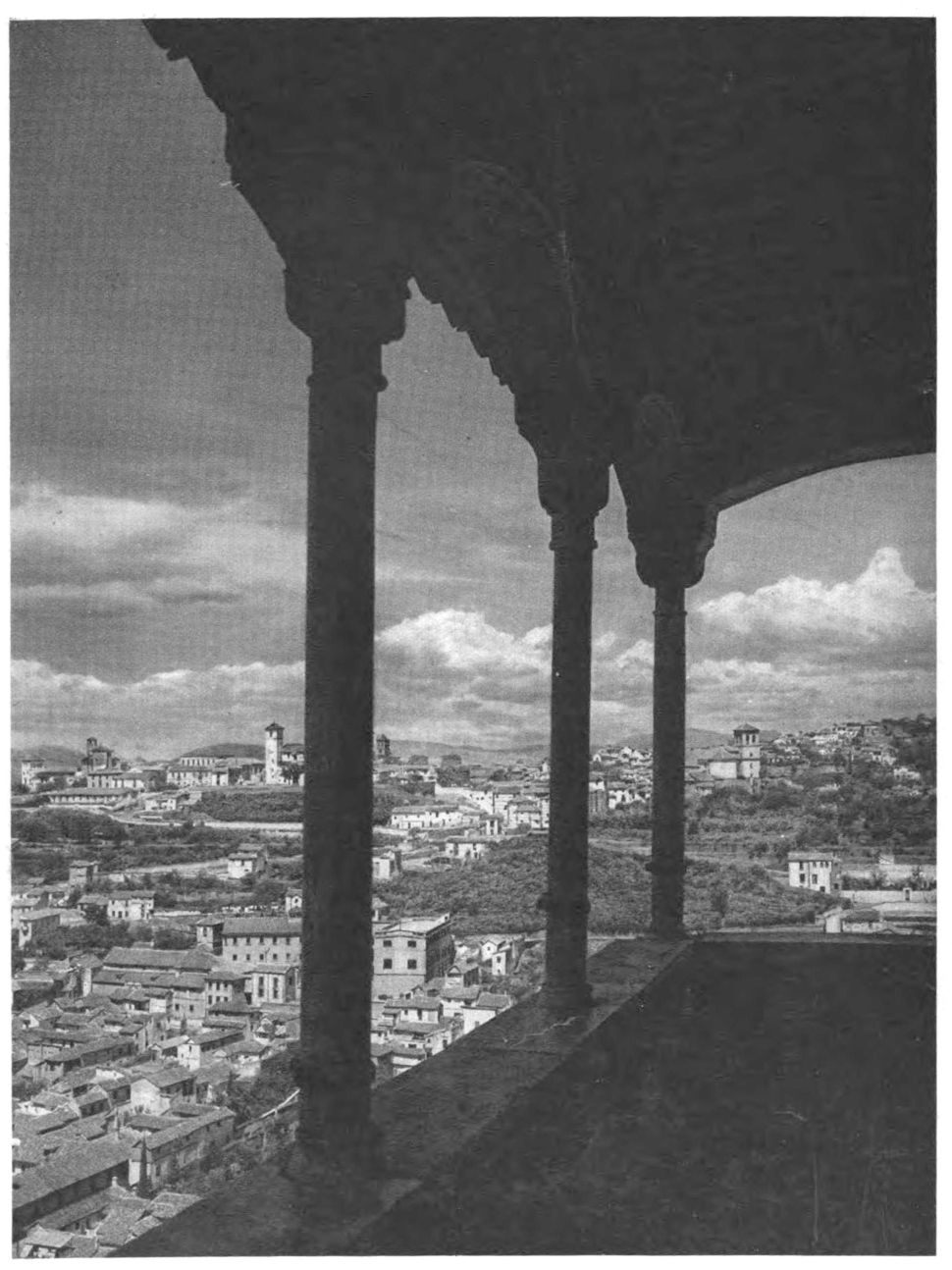

Granada-Alhambra

View of the Albaicin from the Queens Boudoir

Vista desde el Peinador de la Reina sobre el Albaicin

Blick aus dem Putzzimmer der Königin nach dem Albaicin

Vue sur l’Albaicin, prise du boudoir de la reine

Veduta di Albalcin presa dallo spogliatola della regina

Granada

Palace of the Generalife

Palacio del Generalife

Generalifepalast

Palais da Généralife

Palazzo del Generalife

Granada

Entrance-Hall of the Generalife

Entrade del Generalife

Eintrittshalle im Generalife

Entrée du Généralife

Ingresso nel Generalife

Granada

Colonnade in the Generalife

En el Generalife

Säulenhalle im Generalife

Colonade dans le Généralife

Colonnato nel Generalife

Granada

In the Garden of the Generalife

En el jardin del Generalife

Generalifegarten

Un jardin du Généralife

Giardino del Generalife

Granada

View from one of the Generalife Gardens on the Albaicin

Vista desde un jardincito del Generalife sobre el Albaicin

Blick aus einem Generalifegärtchen nach dem Albaicin

Vue sur l’Albaicin, prise d’un jardin du Généralife

Veduta di Albaicin da un giardino del Generalife

Granada

View of Alhambra from the Outlook Tower of the Generalife

Vista desde el Mirador del Generalife sobre la Alhambra

Blick aus dem Aussichtsturm des Generalife auf die Alhambra

Vue sur l’Alhambra, prise du belvedère du Généralife

Veduta dell’Alhambra della torre del Generalife

Granada

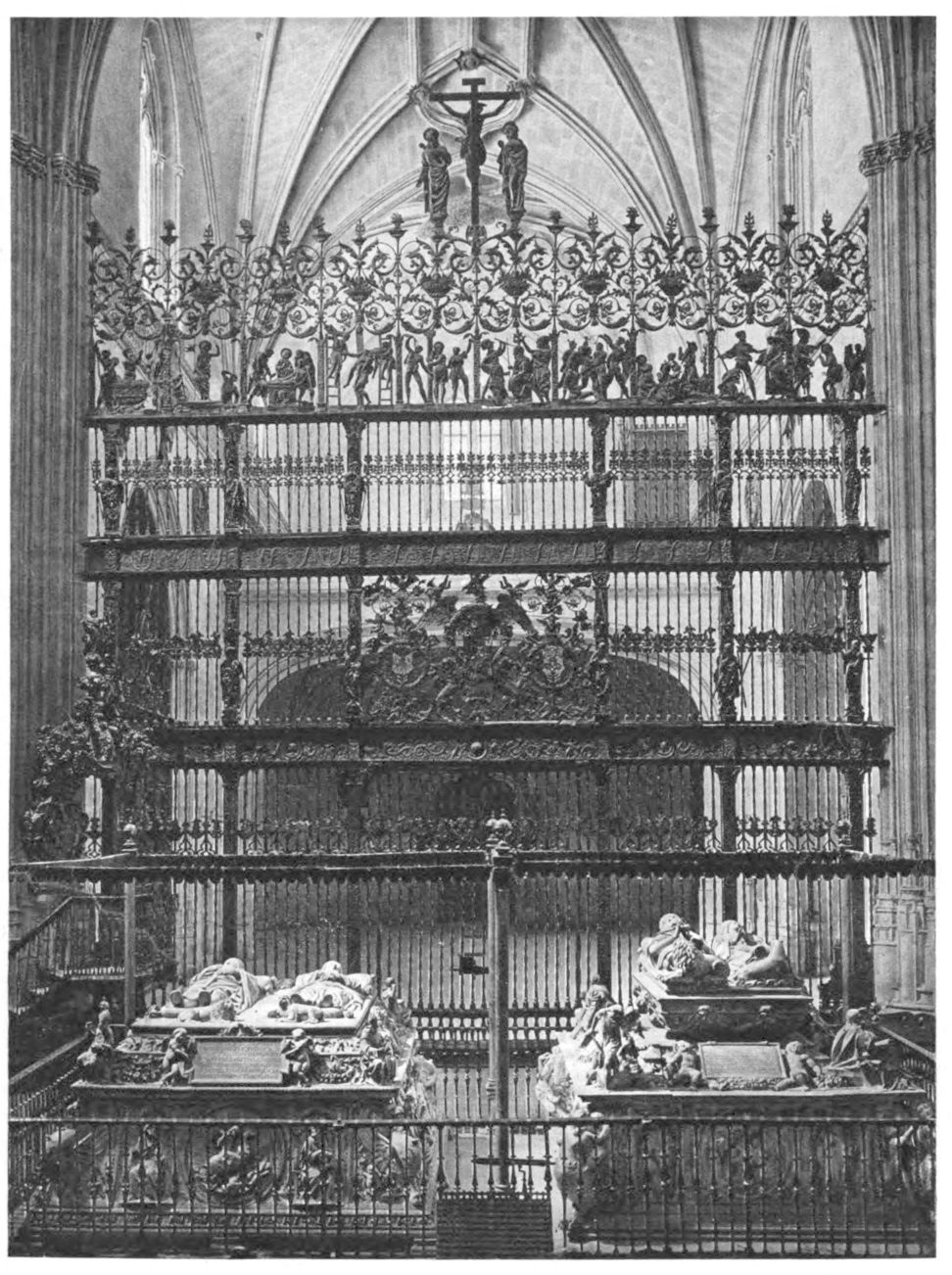

The Cathedral—The Royal Chapel—in the Railing the Passion

La Catedral-Capilla real—En la reja la Pasión de Jesucristo

Kathedrale-Capilla real—im Gitter die Leidensgeschichte Christi

A la Cathedrale—La Chapelle royale—Au haut de la grille sont representées les scènes de la Passion de Jésus-Christ

Cattedrale—Capello Reale—Nel cancello è raffigurata la passione di Cristo

Sevilla

General View of the Town from the Giralda Tower of the Cathedral

Vista general, tomada desde la Giralda

Blick vom Turm der Kathedrale (der Giralda) über die Stadt

Vue générale, prise de la Giralda (tour de la cathédrale)

Veduta dalla citta dalla torre (la Giralda) della Cattedrale

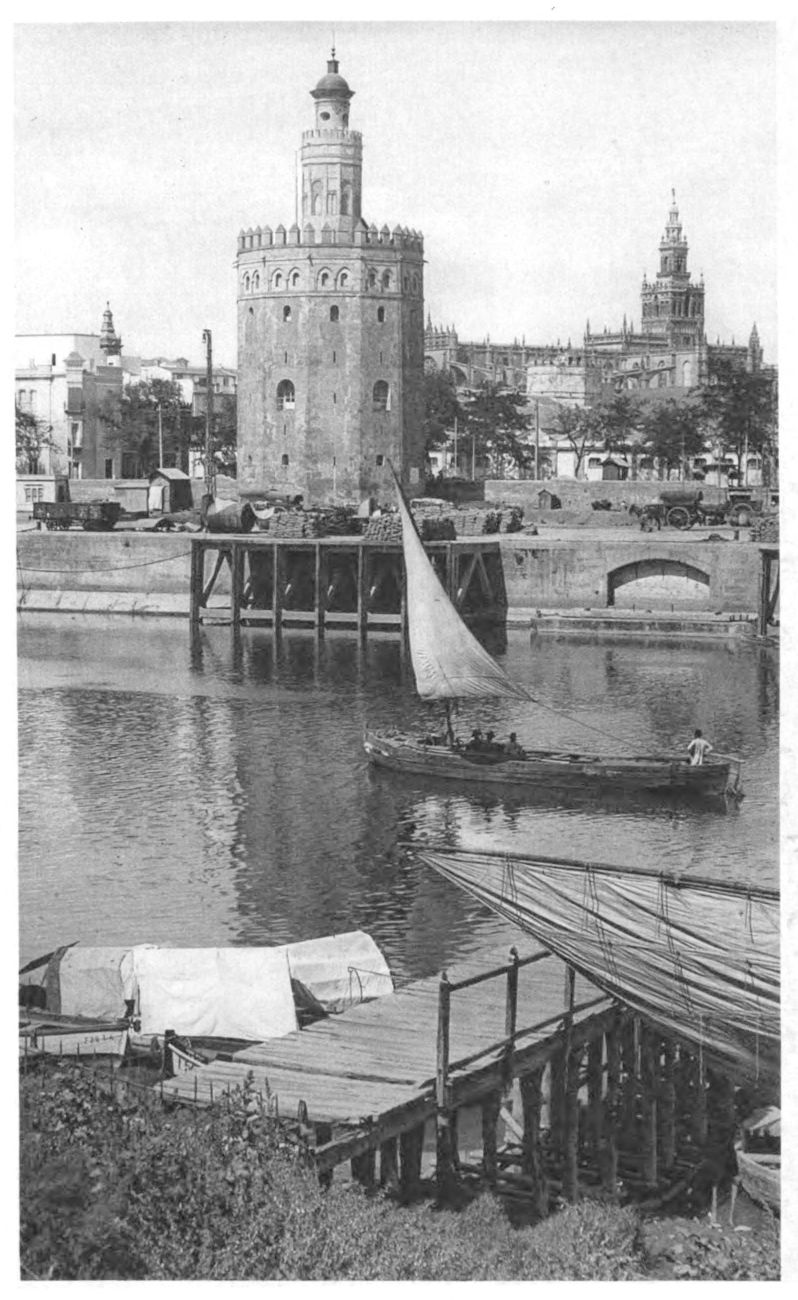

Sevilla

The Golden Tower and the Cathedral

La torre de Oro y la Catedral

Der Goldturm und die Kathedrale

La tour d’or et la cathédrale

La torre dell’ora e la Cattedrale

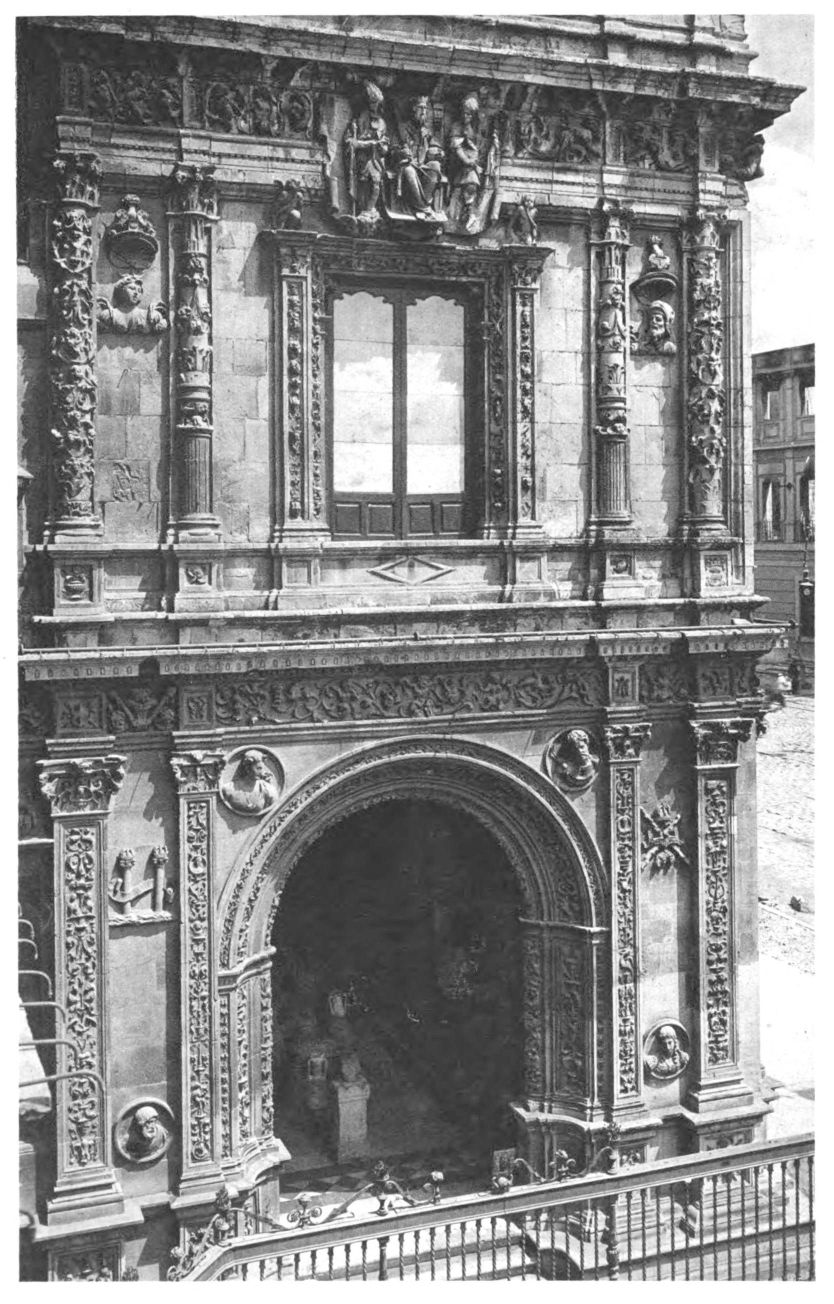

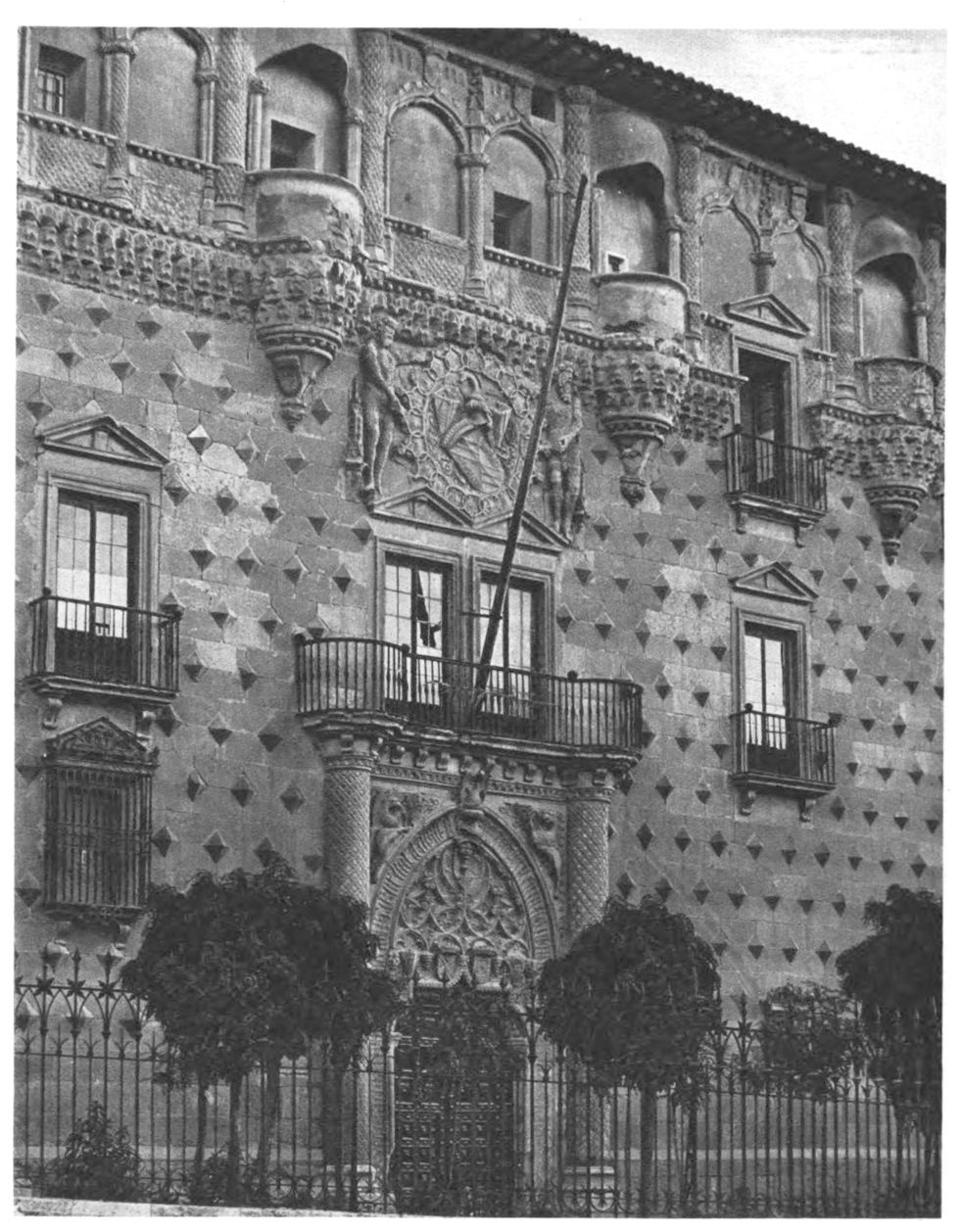

Sevilla

Details of the City-Hall Façade

Detalle de la fachada del Ayuntamiento

Teilstück der Rathausfassade

Détail de la façade de l’hôtel de ville

Dettaglio della facciata del Municipio

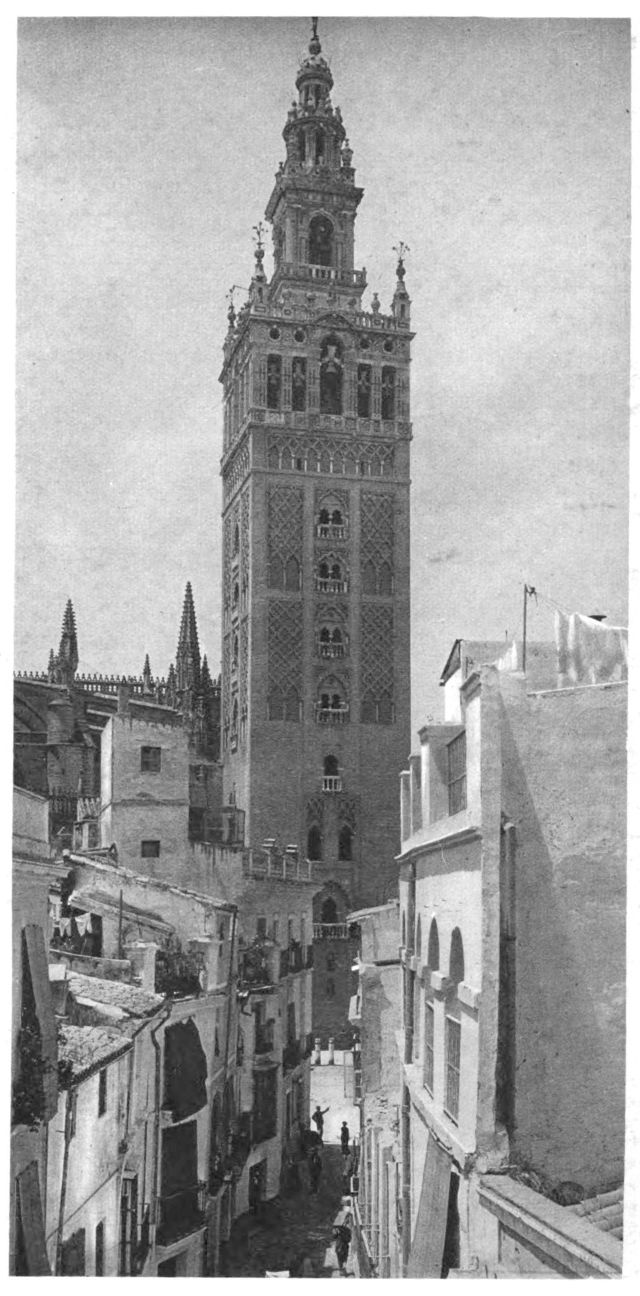

Sevilla

The Giralda (Cathedral Tower)

La Giralda

Die Giralda (Turm der Kathedrale)

La Giralda (Tour de la cathédrale)

La Giralda (la torre della Cattedrale)

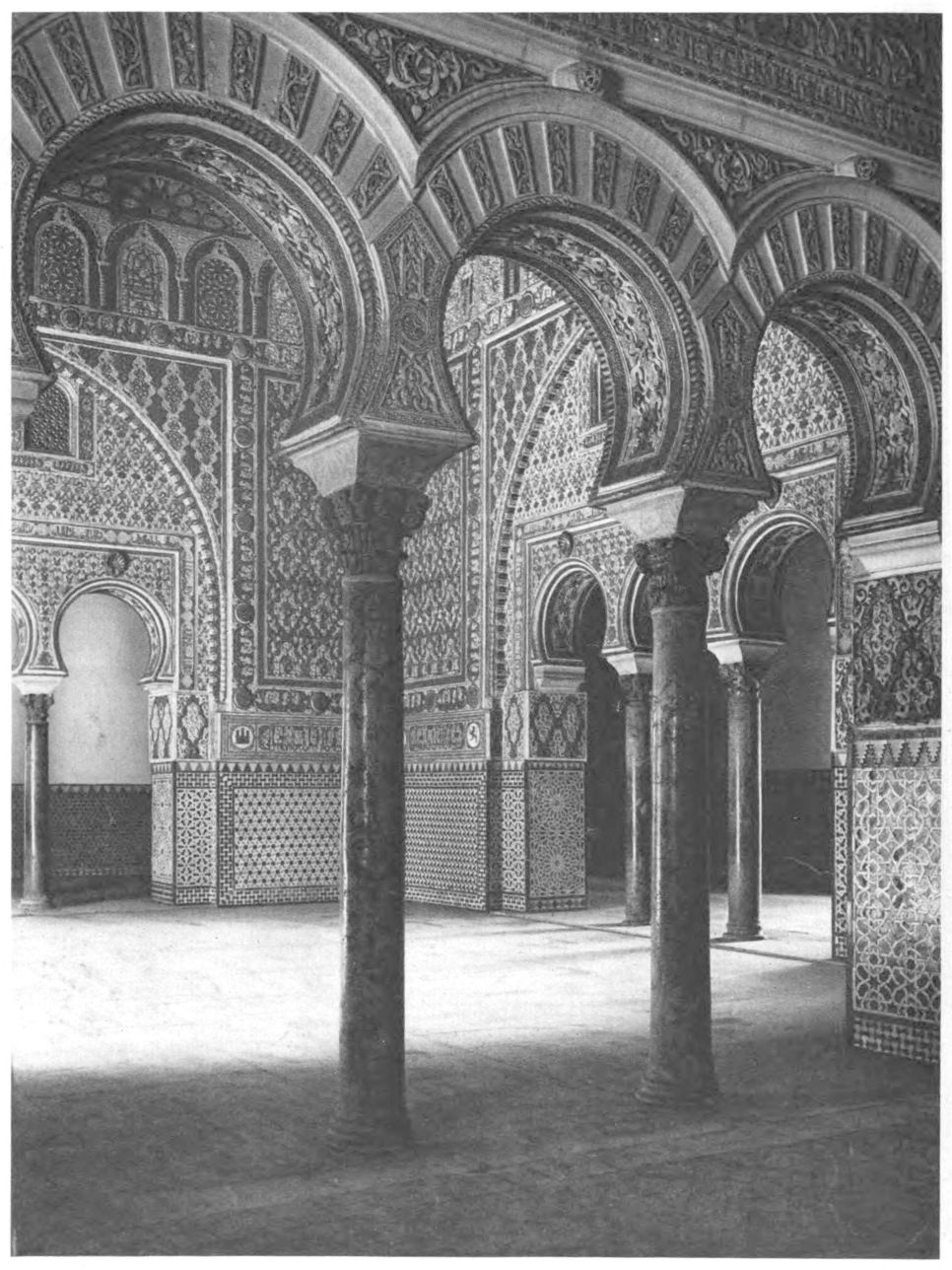

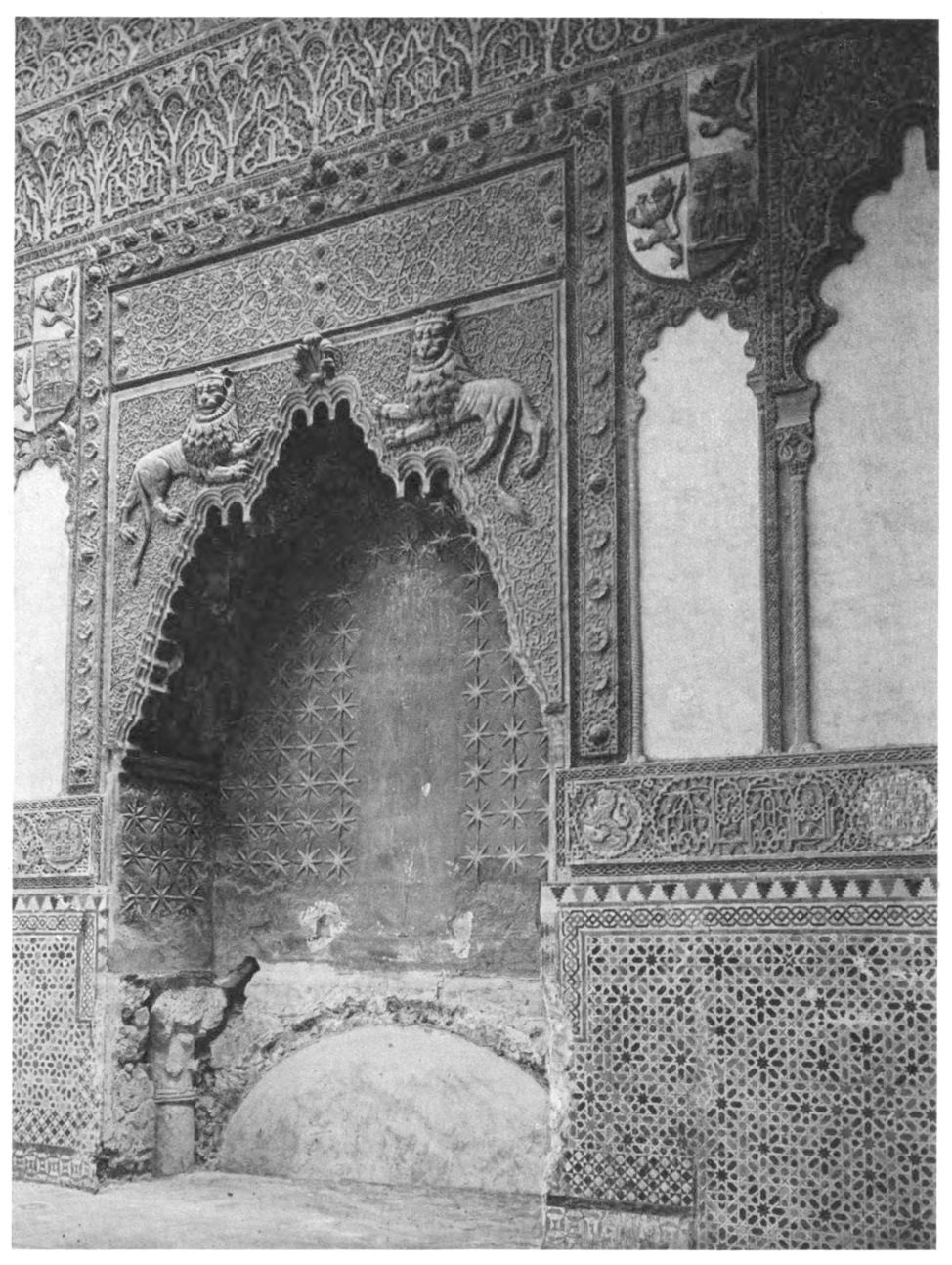

Sevilla-Alcázar

The Ambassadors’ Hall

Sala de Embajadores

Gesandtensaal

Salle des ambassadeurs

La Sala degli Ambasciatori

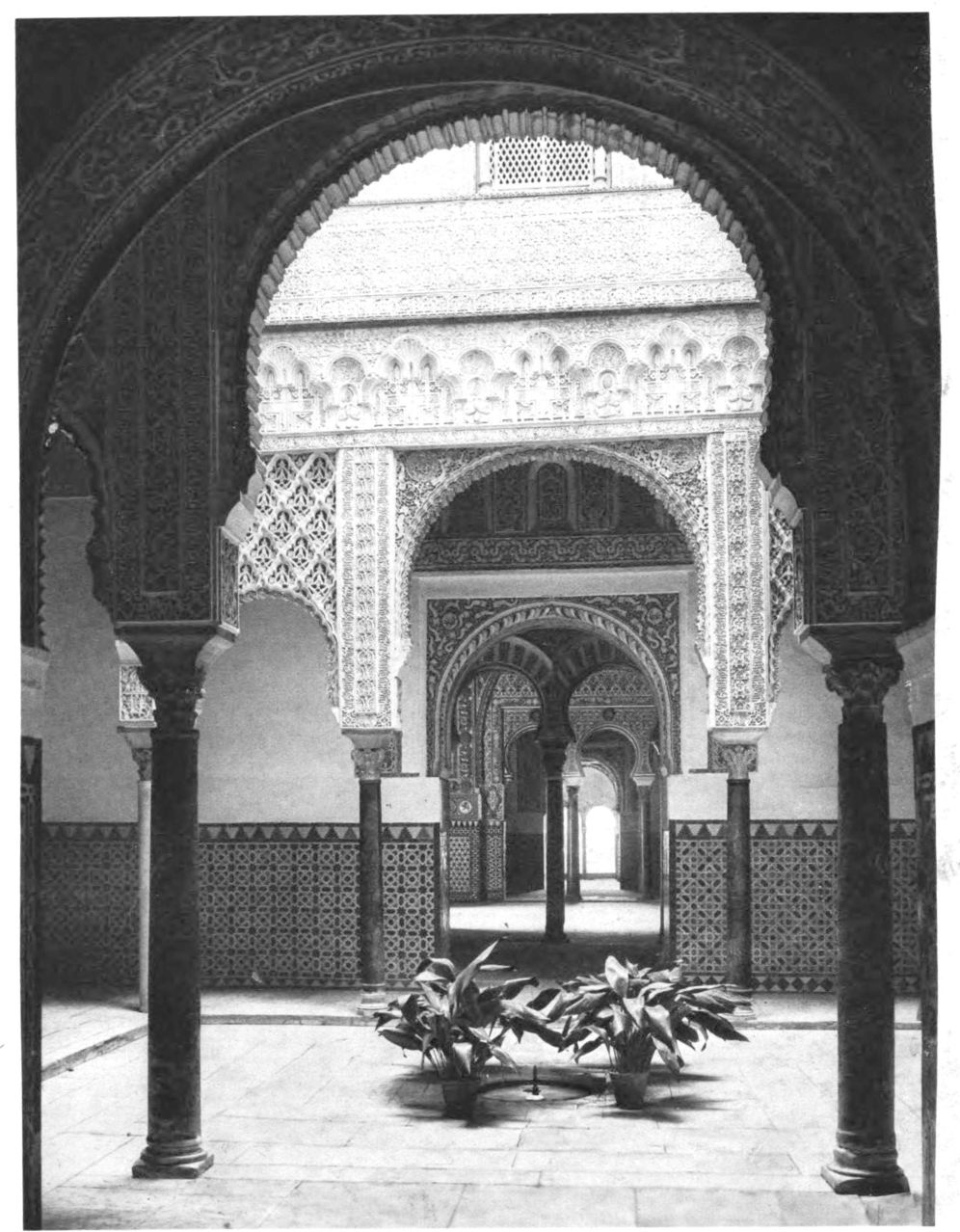

Sevilla-Alcázar

The Dolls’ Court

Patio de las Muñecas

Puppenhof

La cour des poupées

La Corte delle bambole

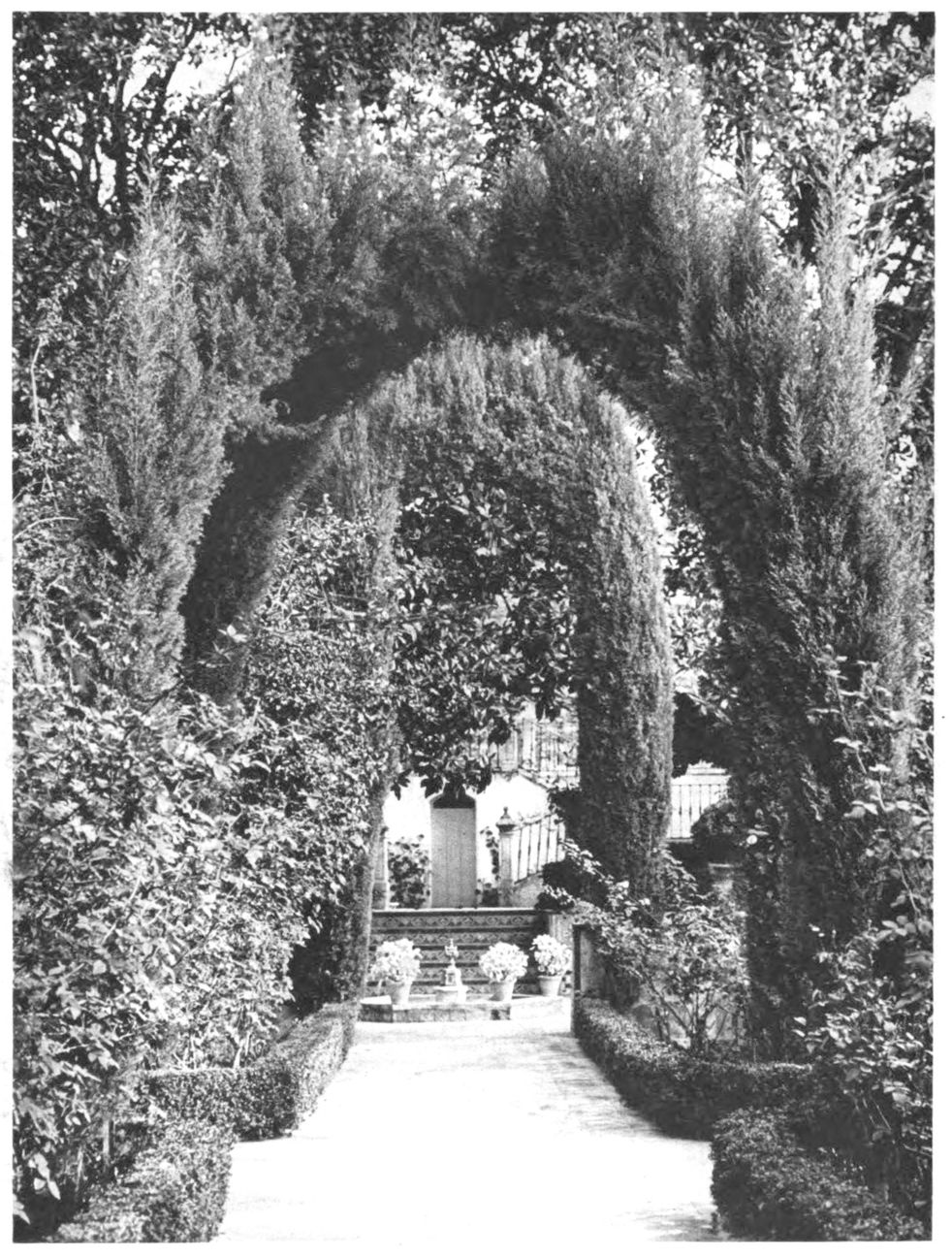

Sevilla

In the Alcázar Garden

En el jardin del Alcázar

Im Alcázargarten

Au jardin de l’Alcázar

Nel giardino dell’Alcázar

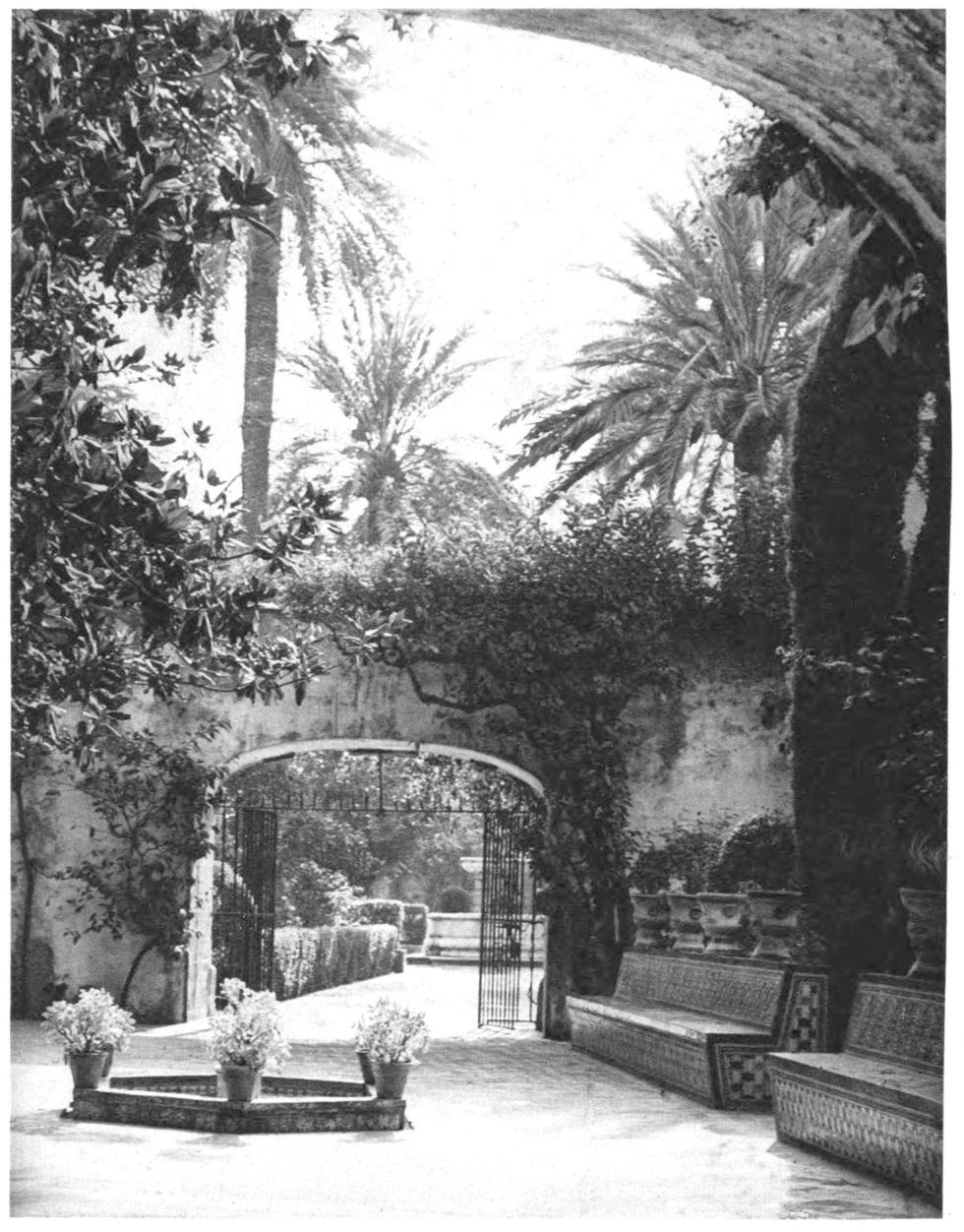

Sevilla

In the Alcázar Garden

En el jardin del Alcázar

Im Alcázargarten

Au jardin de l’Alcázar

Nel giardino dell’Alcázar

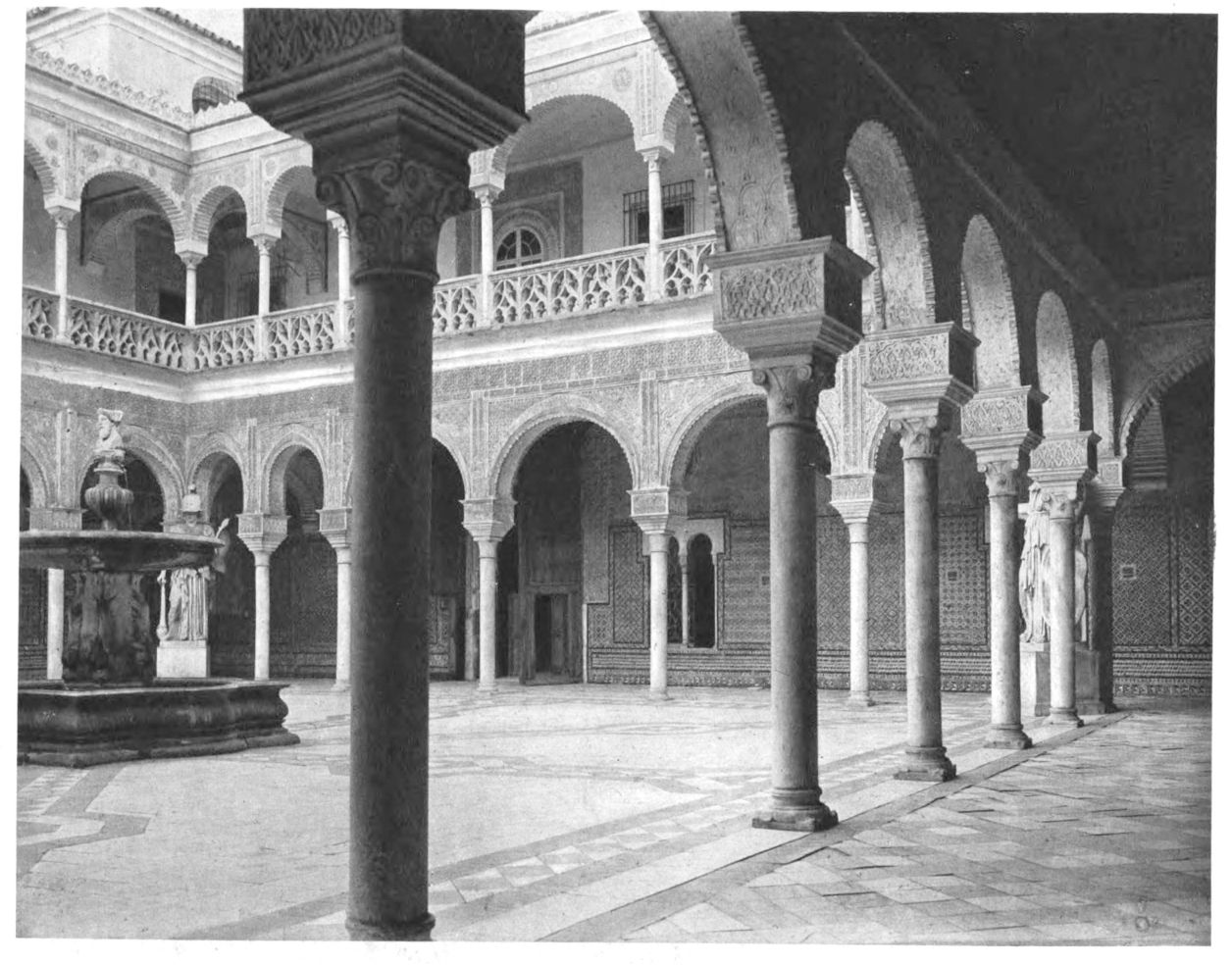

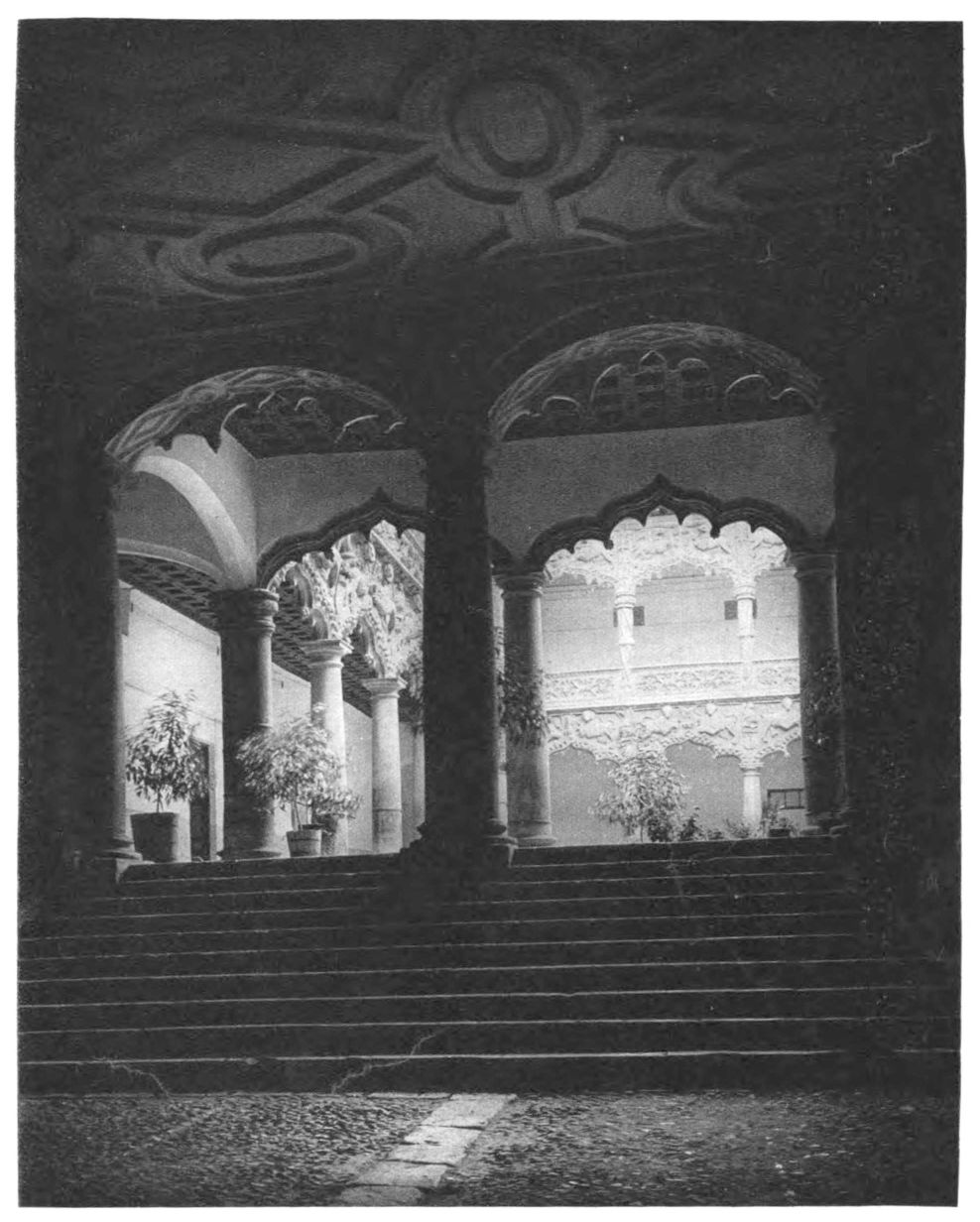

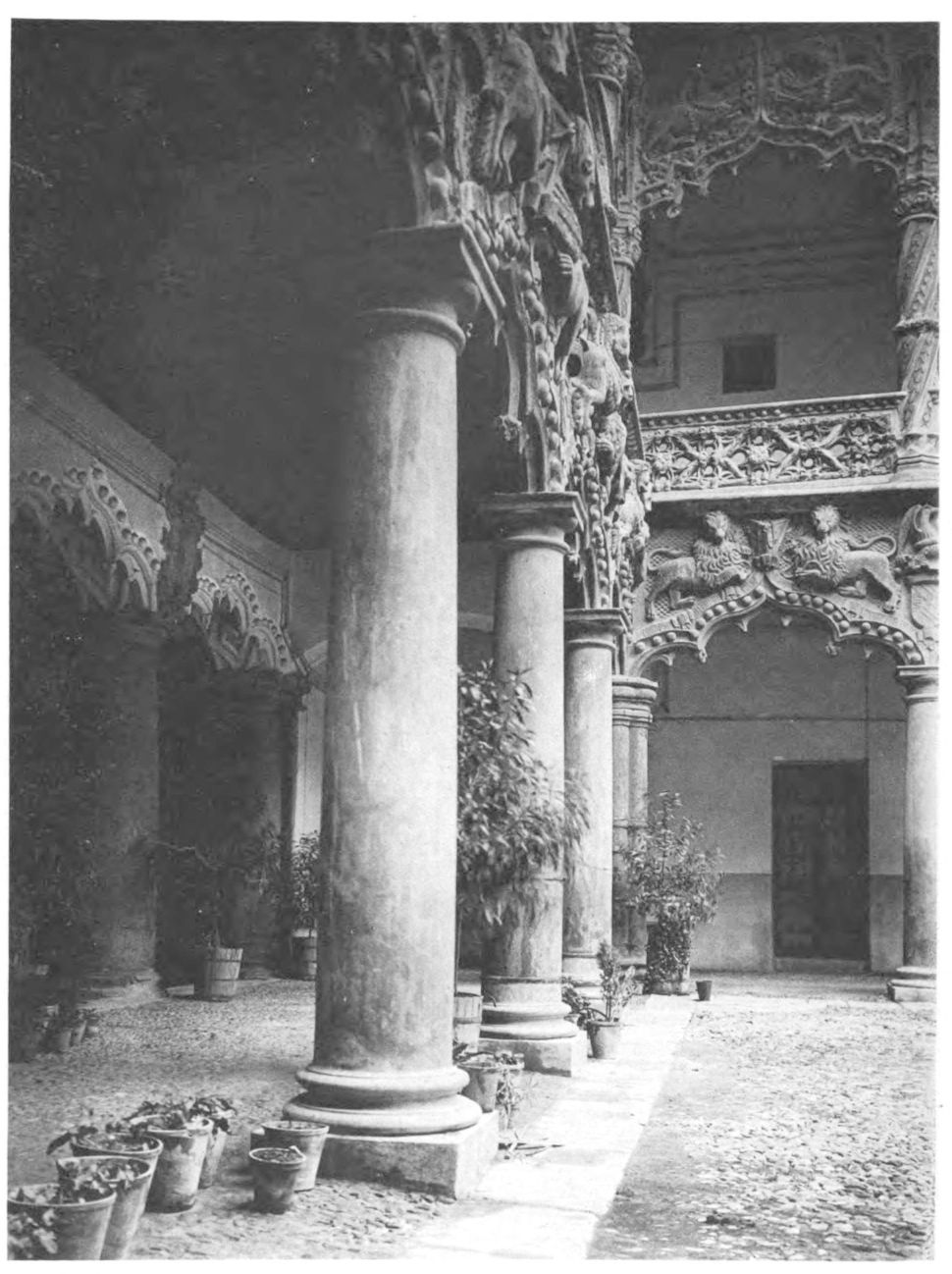

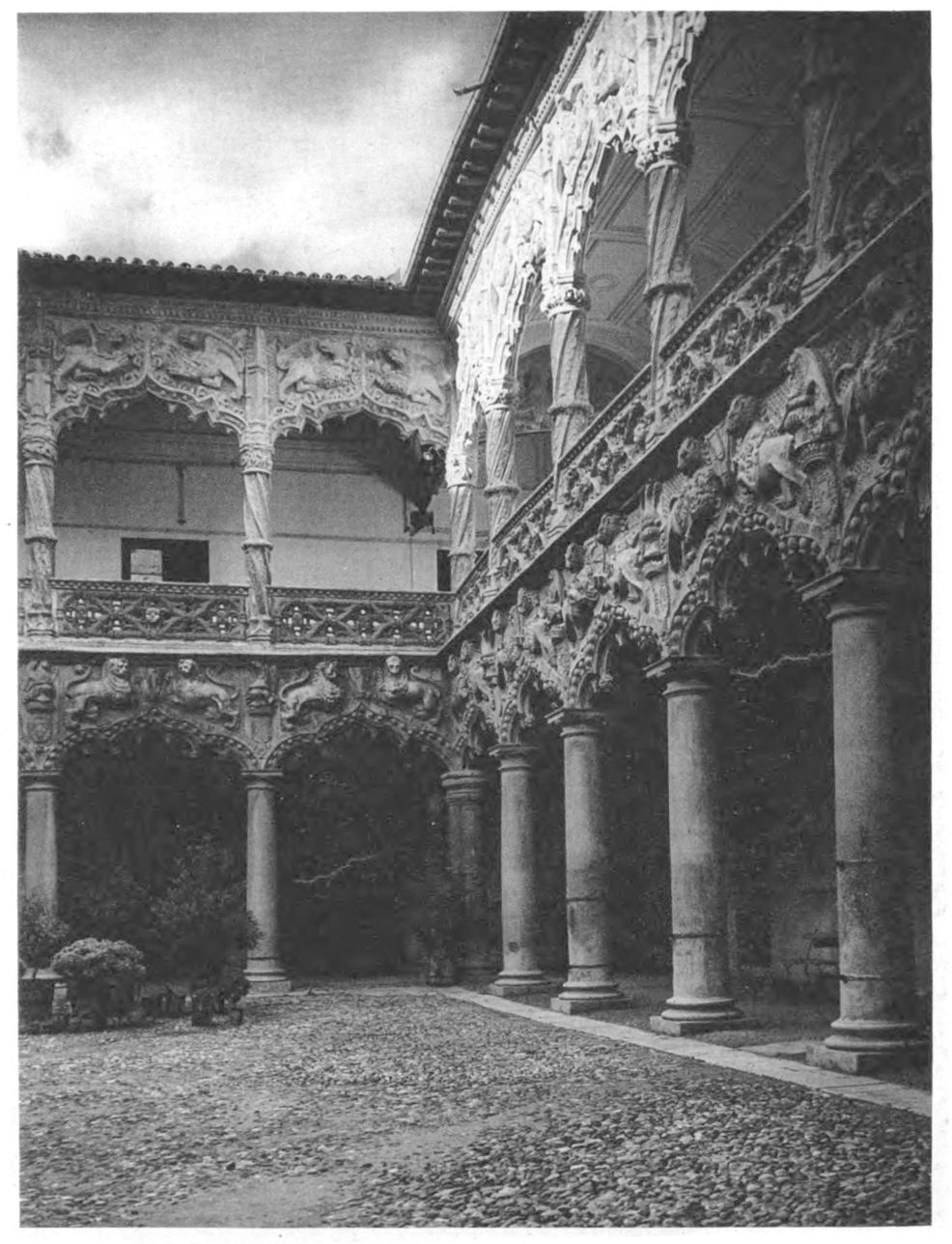

Sevilla

Court in Pilate’s House

Patio de la Casa de Pilato

Hof im Pilatushaus

Cour intérieure de la maison de Pilate

La Casa di Pilato, Corte

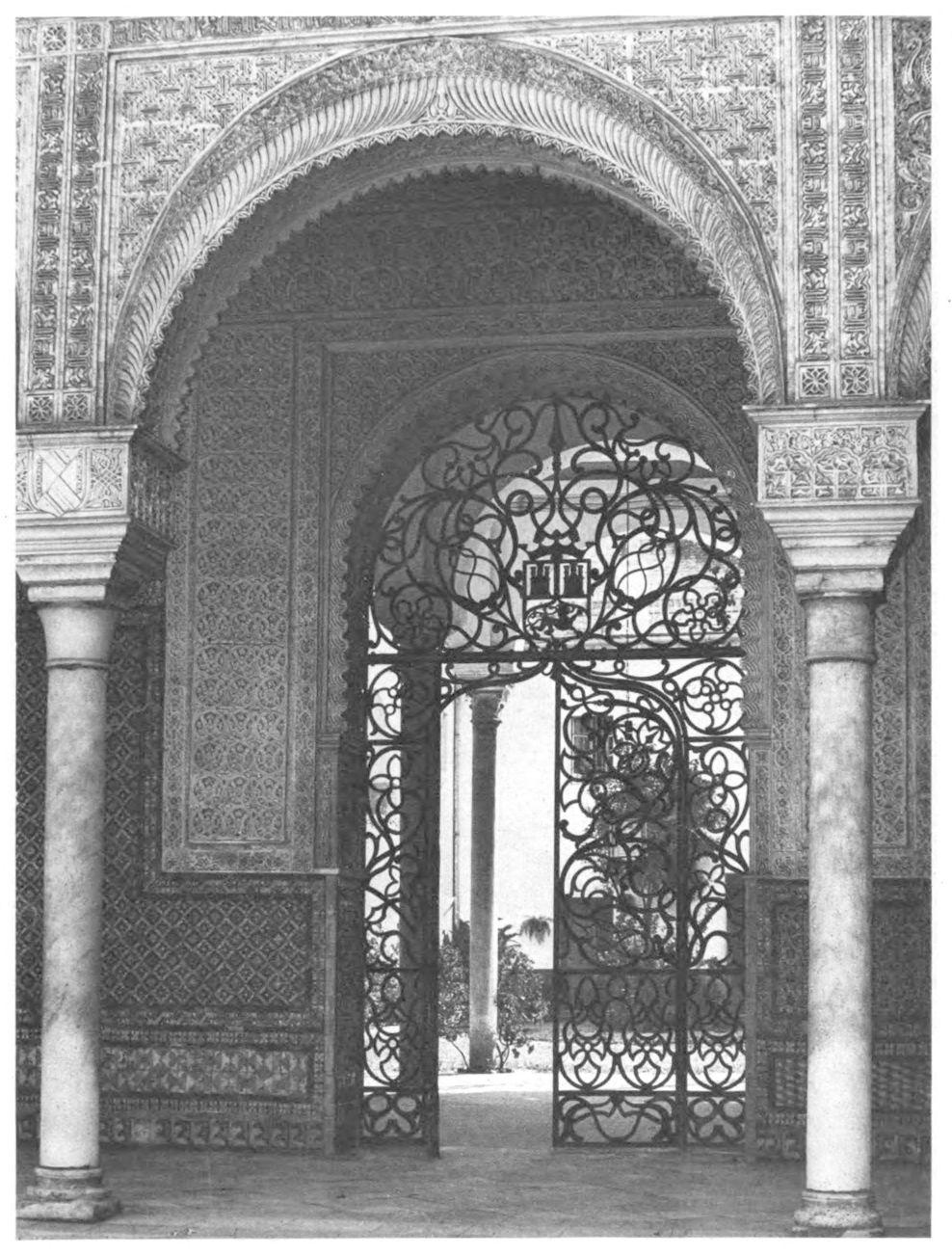

Sevilla

Court Gates, Pilate’s House

Portada de la Casa de Pilato

Tür zum Hof des Pilatushauses

Entrée de la cour de la maison de Pilate

Porta di accesso alla Corte della Casa di Pilato

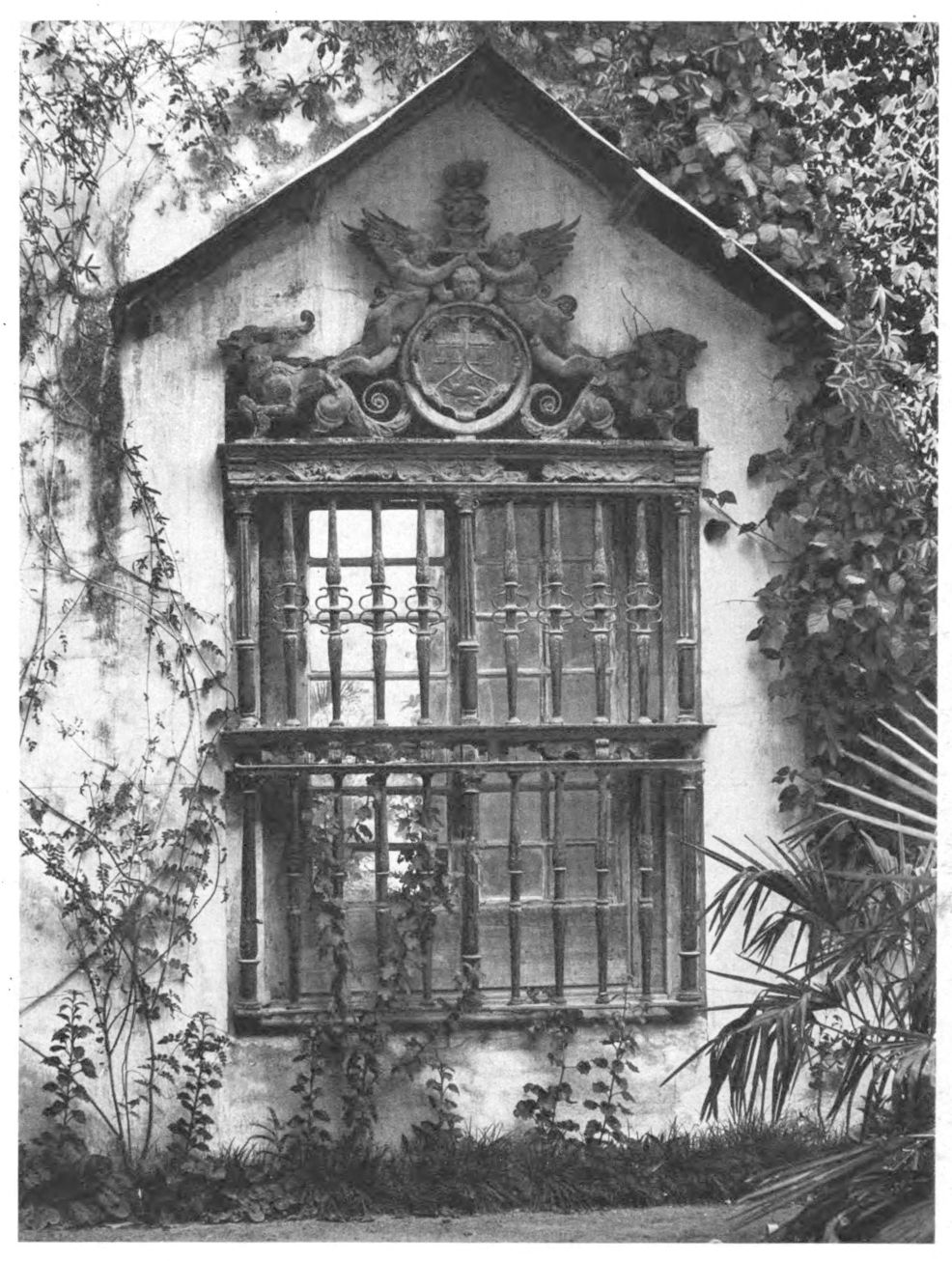

Sevilla

Pilate’s House—Grille

Casa de Pilato—Reja

Pilatushaus—Fenstergitter

Fenêtre grillée de la maison de Pilate

Casa di Pilato. Finestra con grata

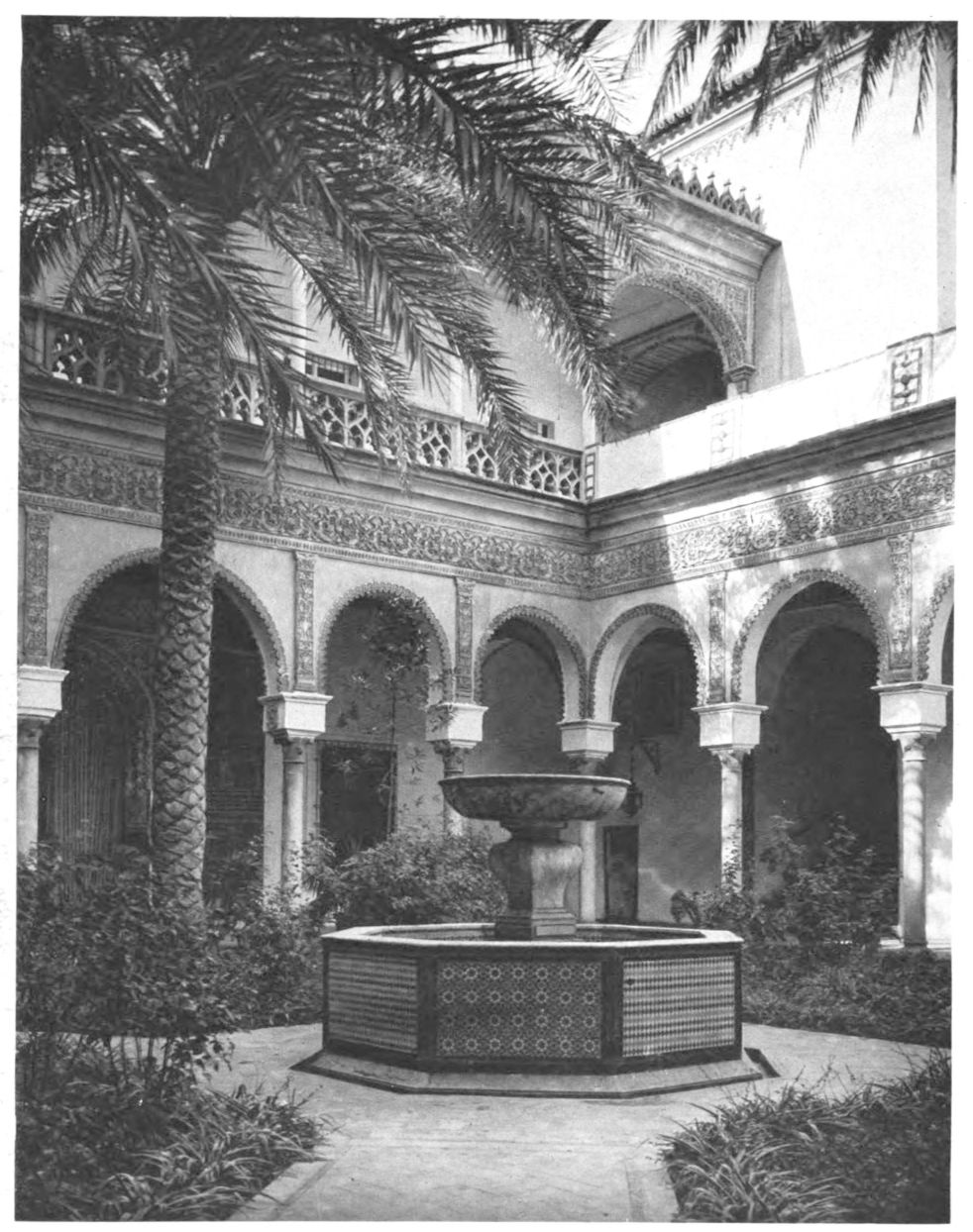

Sevilla

Court in Duke Alba’s Palace

Patio en el palacio del duque de Alba

Hof im Palast des Herzogs Alba

Cour intérieure du palais du duc d’Albe

La Corte nel Cortile del Duca d’Alba

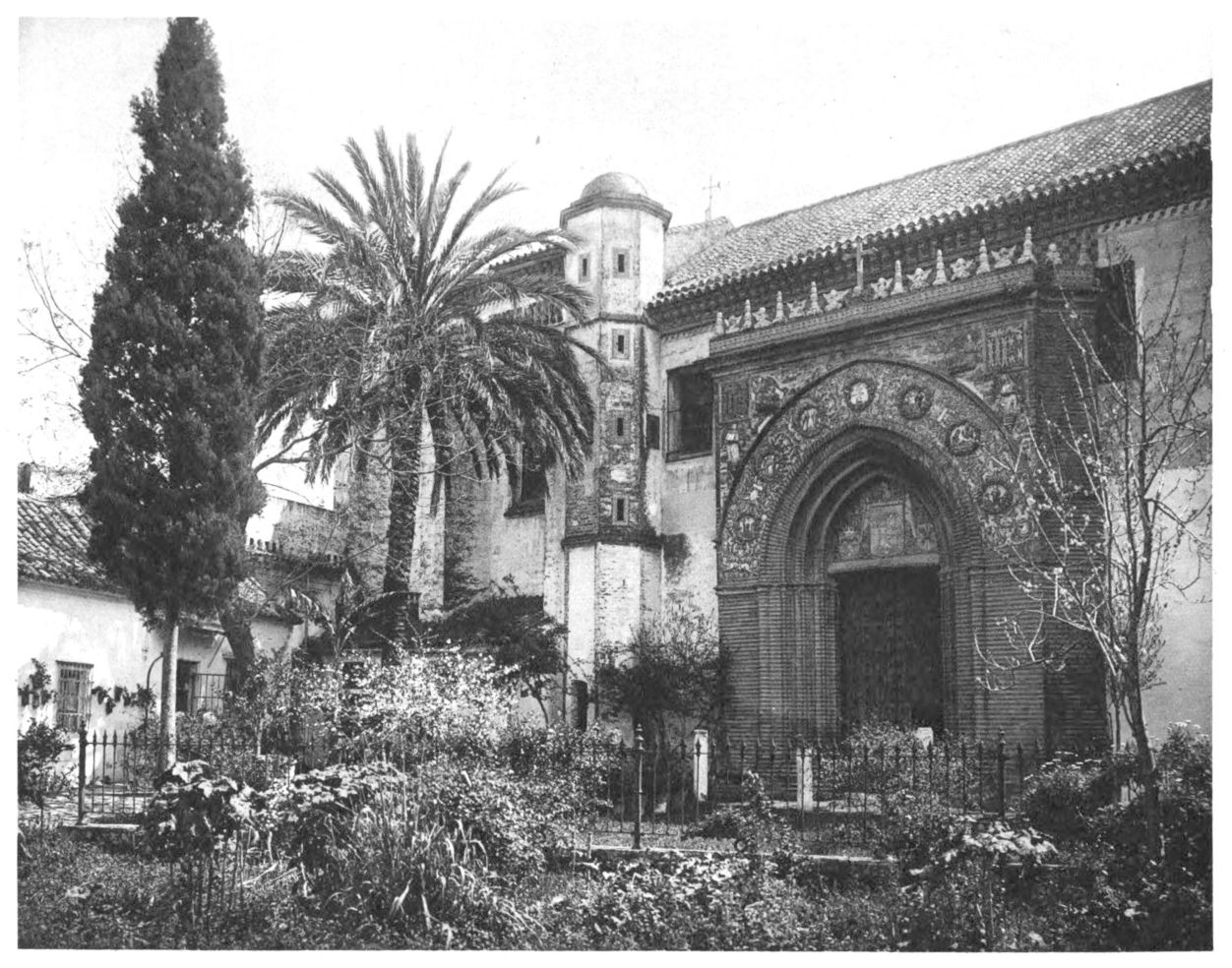

Sevilla

St. Paul’s Convent

Convento de Sta. Paula

Kloster Sta. Paula

Couvent de Sainte Paule

Il Convento di Santa Paola

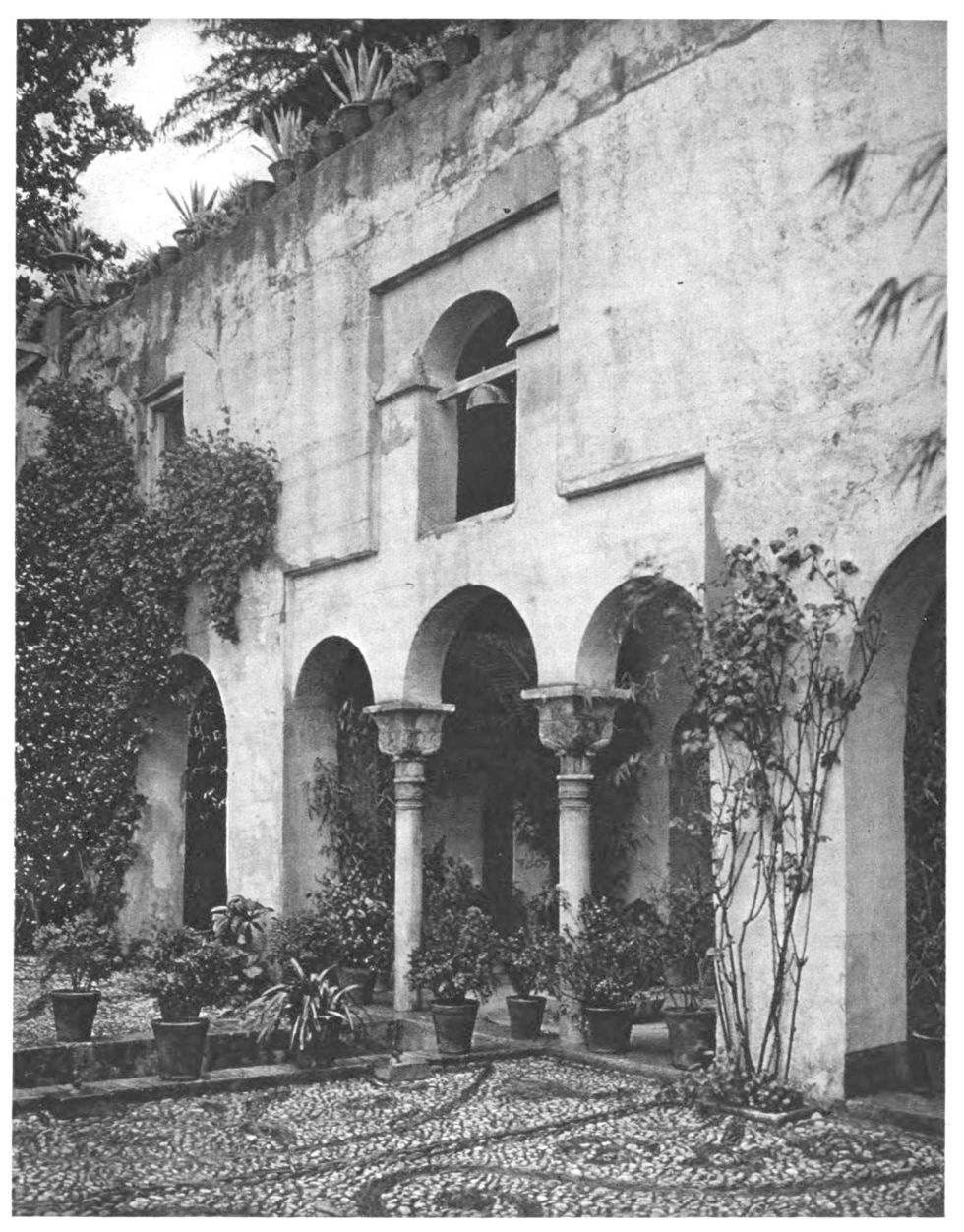

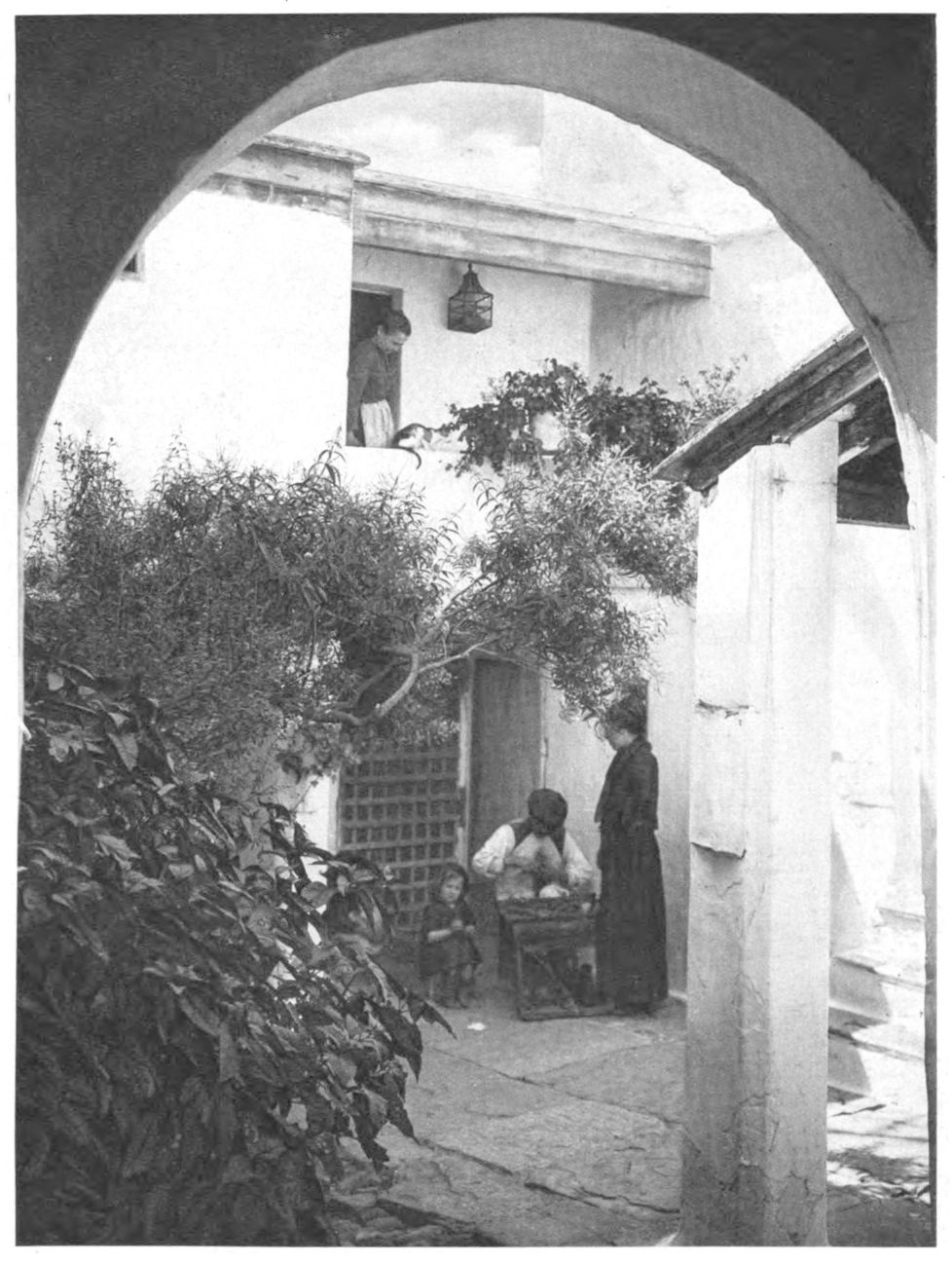

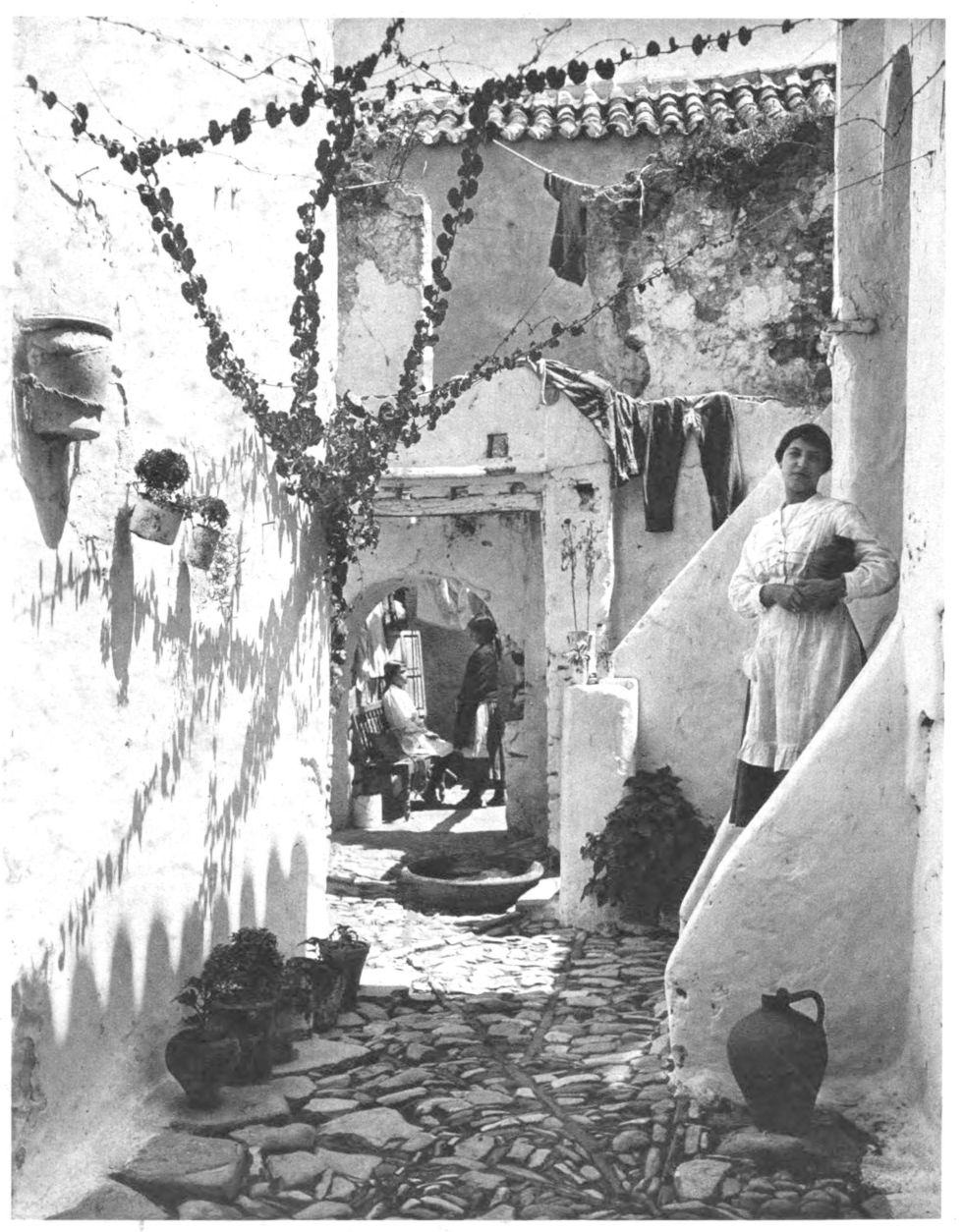

Court in Carmona

Patio en Carmona

Hof in Carmona

Une cour de maison à Carmona

Il cortile in una casa di Carmona

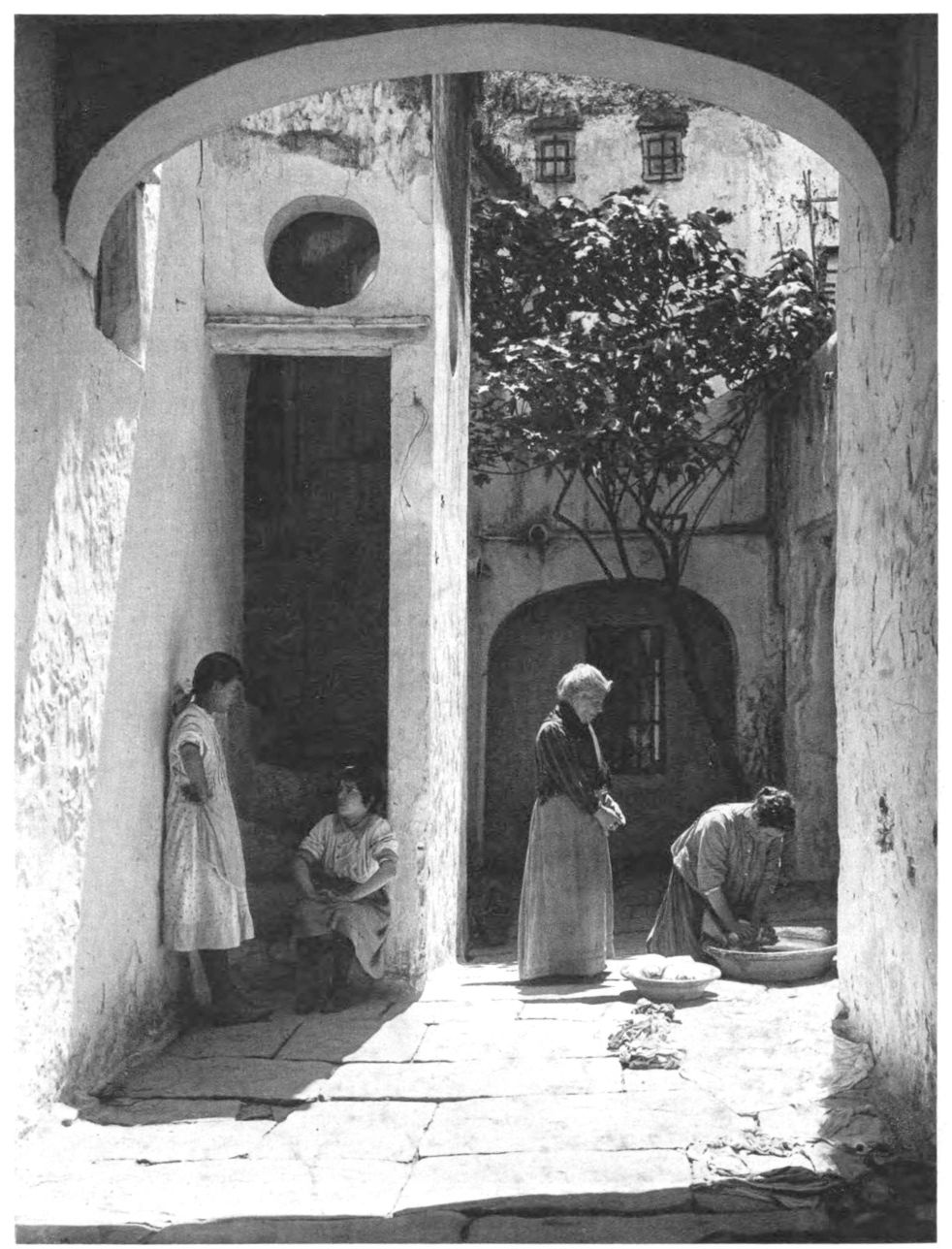

Court in Andújar

Patio en Andújar

Hof in Andújar

Une cour de maison à Andújar

Il cortile in una casa di Andújar

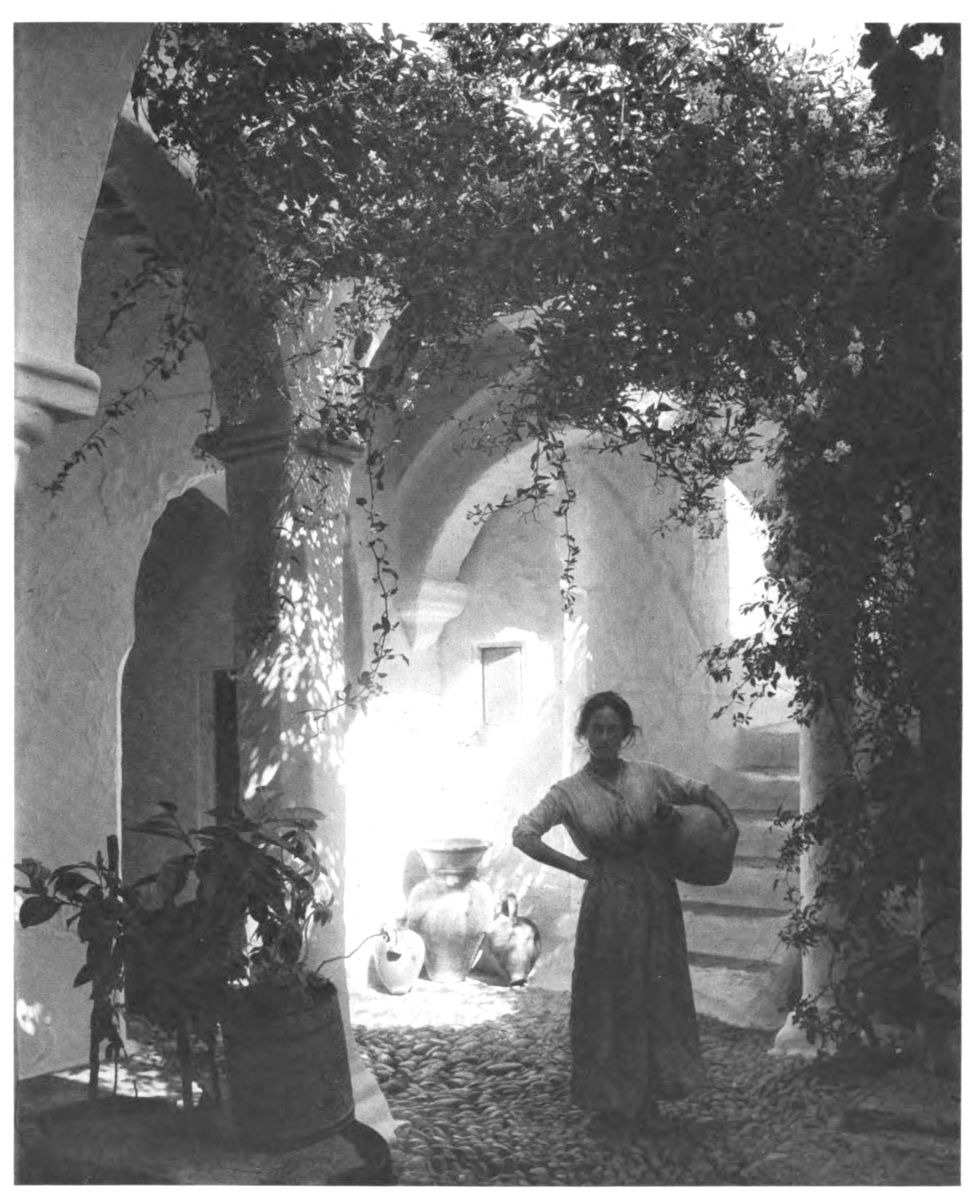

Court in Tarifa

Patio en Tarifa

Hof in Tarifa

Une cour de maison à Tarifa

Il cortile in una casa di Tarifa

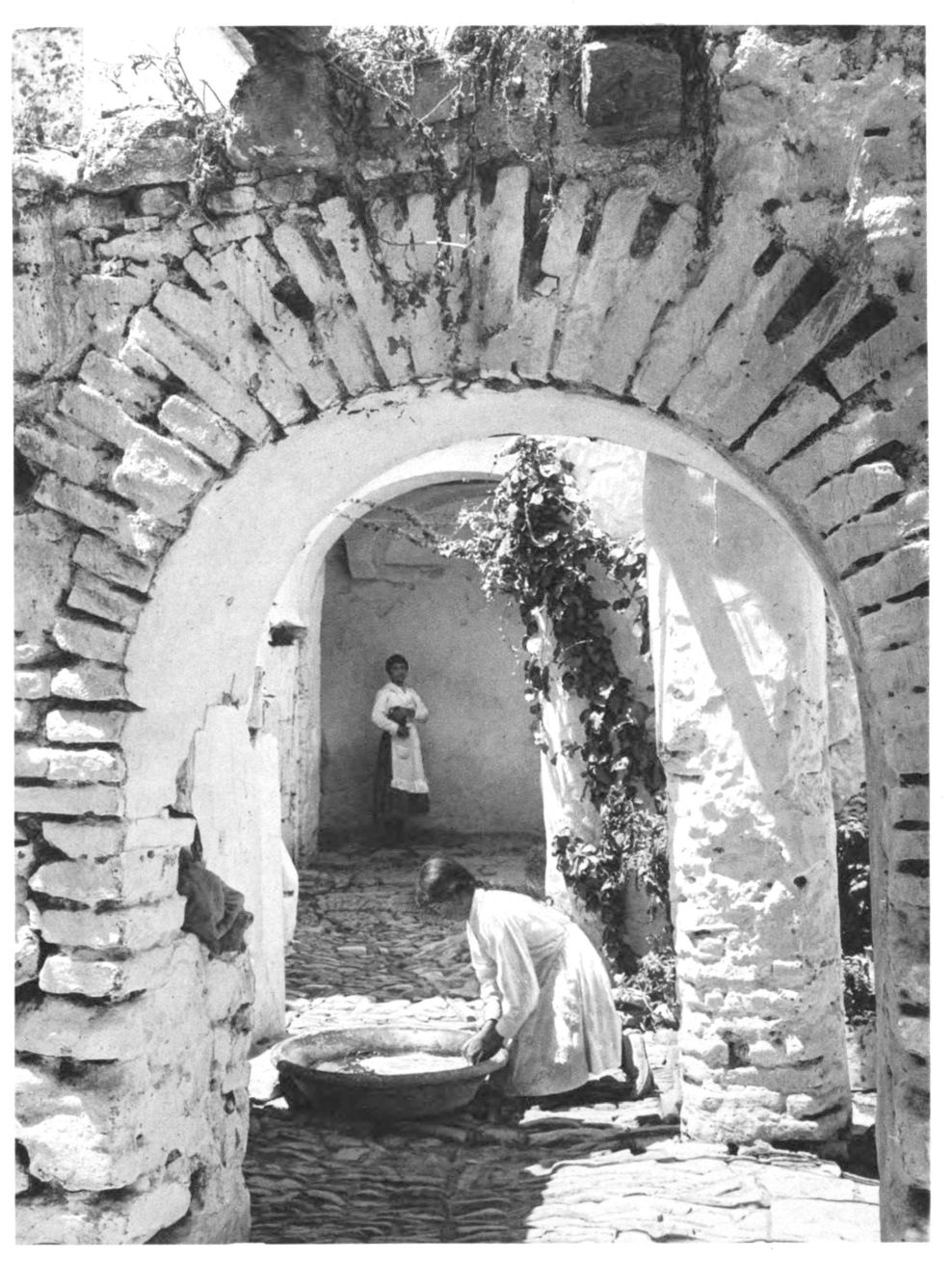

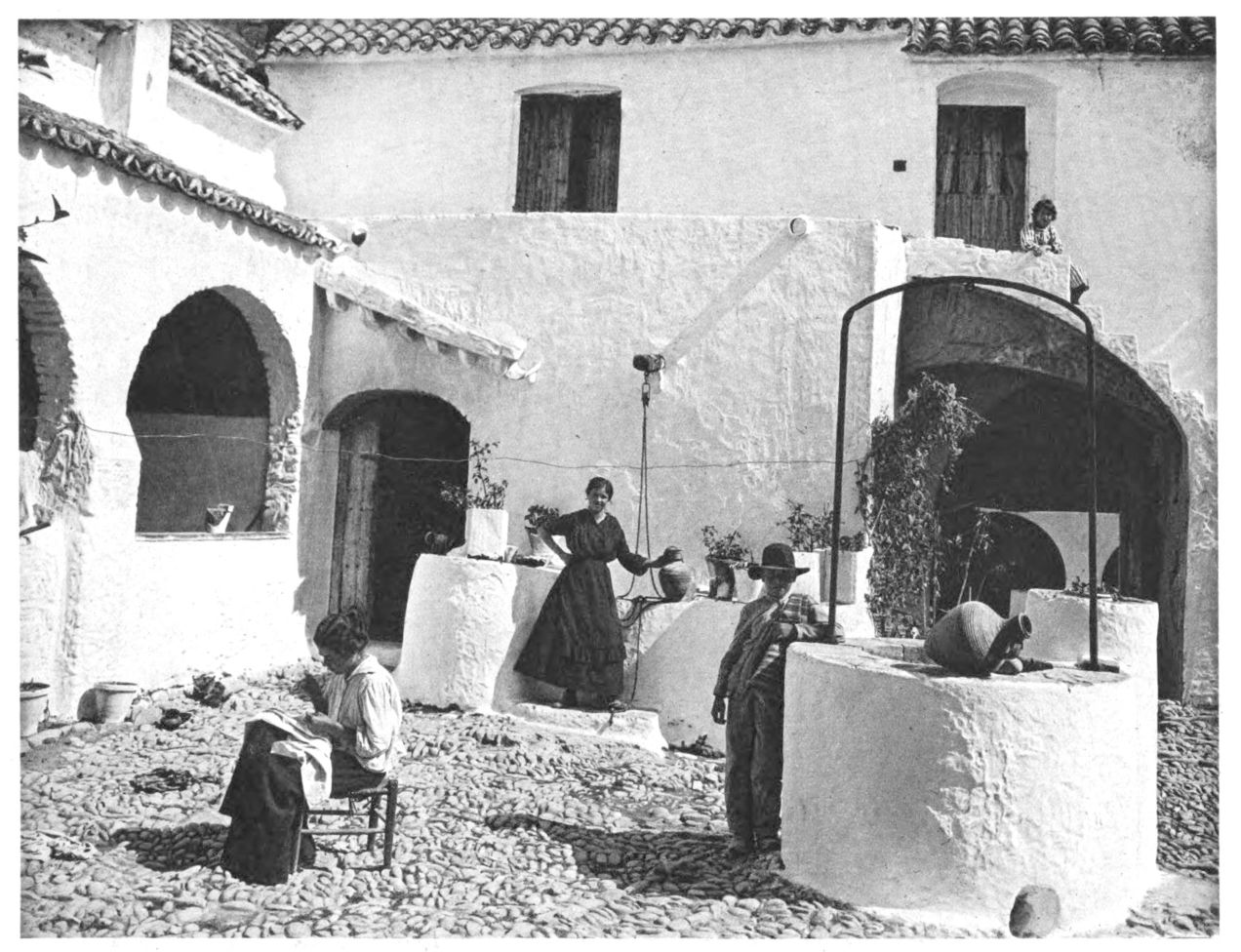

Court in Tarifa

Patio en Tarifa

Hof in Tarifa

Une cour de maison à Tarifa

Il cortile in una casa di Tarifa

Court in Vejer

Patio en Vejer

Hof in Vejer

Une cour de maison à Vejer

Il cortile in una casa di Vejer

Court in Arcos de la Frontera

Patio en Arcos de la Frontera

Hof In Arcos de la Frontera

Une cour de maison à Arcos de la Frontera

Il cortile in una casa di Arcos de la Frontera

Court in Arcos de la Frontera

Patio en Arcos de la Frontera

Hof in Arcos de la Frontera

Une cour de maison à Arcos de la Frontera

Il cortile di una casa a Arcos de la Frontera

Cordoba

Facade of the Mosque

Fachada de la Mezquita

Fassade der Moschee

Façade de la mosquée

Facciata della Moschea

Cordoba

Columns in the Mosque

Columnas en la Mezquita

Säulenwald der Moschee

Le fouillis des colonnes à l’intérieur de la mosquée

La selva delle colonne nell’interno della Moschea

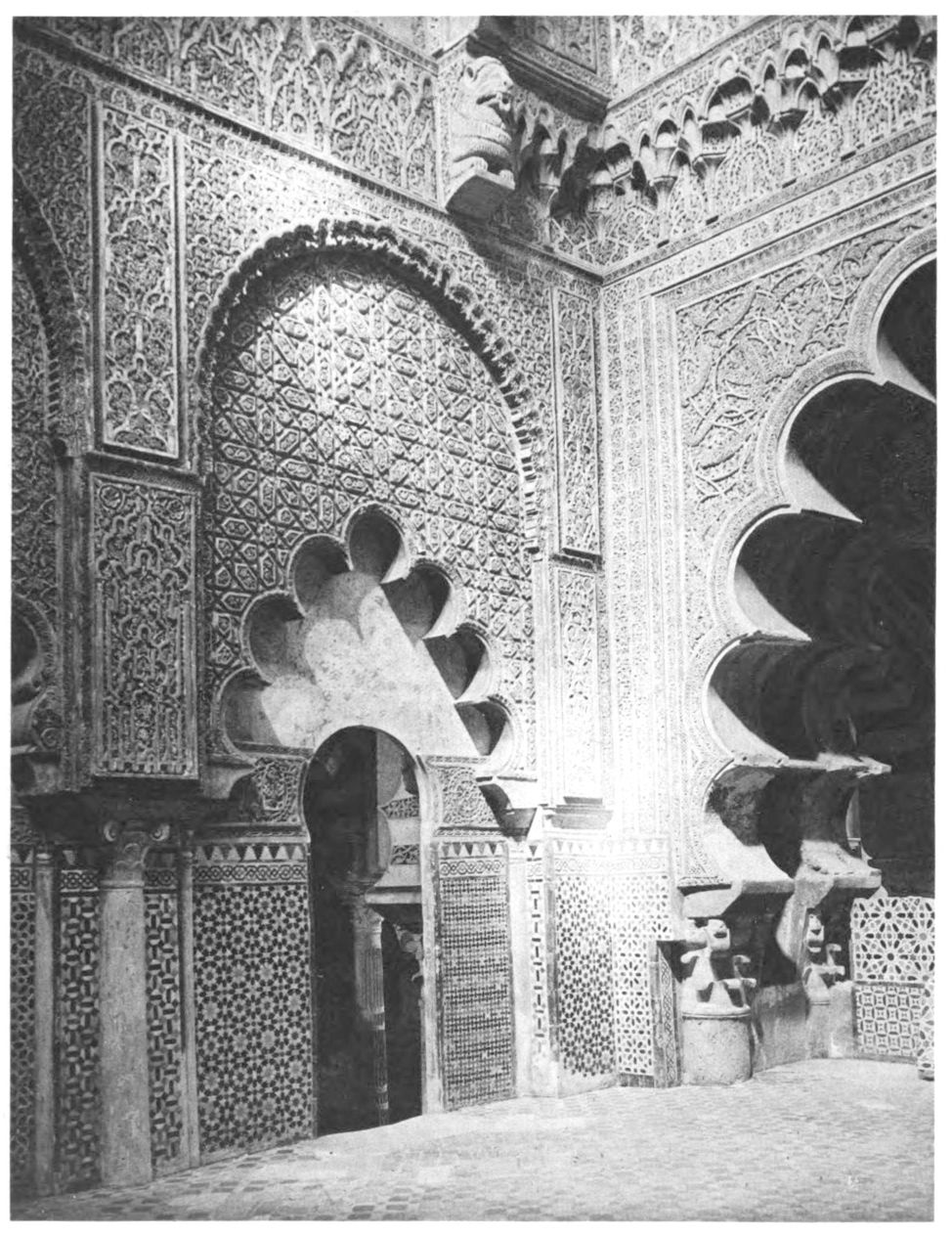

Cordoba

Mihrab Mosque (Holy of Holies)

Mezquita—Mihrab

Moschee—Mihrab (Allerheiligstes)

La Mosquée: le Mihrab (sanctuaire)

La Moschee: Mihrab (santuario)

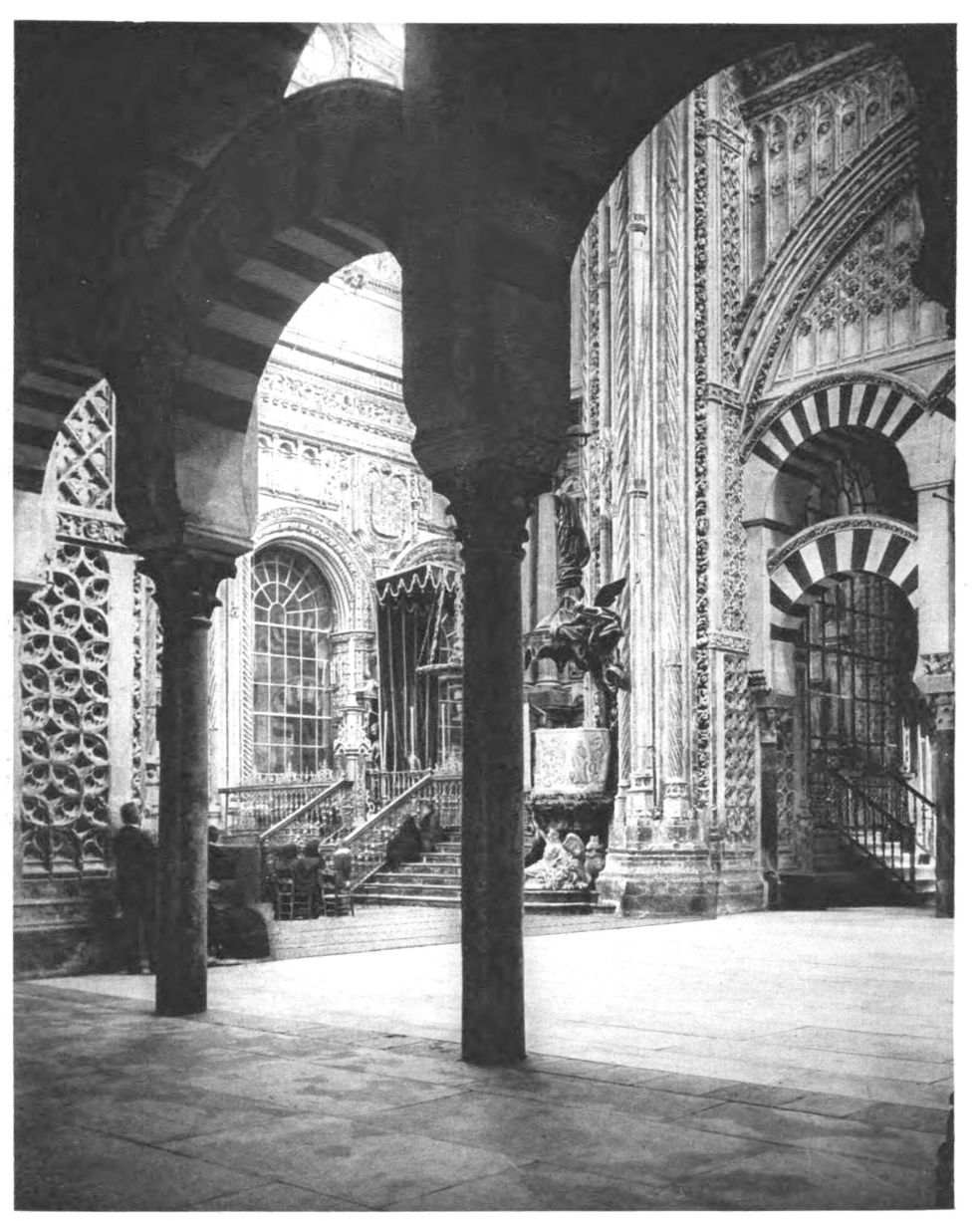

Cordoba

Interior of the Mosque

En la Mezquita

Moscheeinneres

Intérieur de la mosquée

L’interno della Moschee

Cordoba

Mosque—View of the High Altar

Mezquita—Vista del altar mayor

Moschee—Blick zum Hochaltar

La Mosquée: vue du maître-autel

La Moschea: veduta dell’altar maggiore

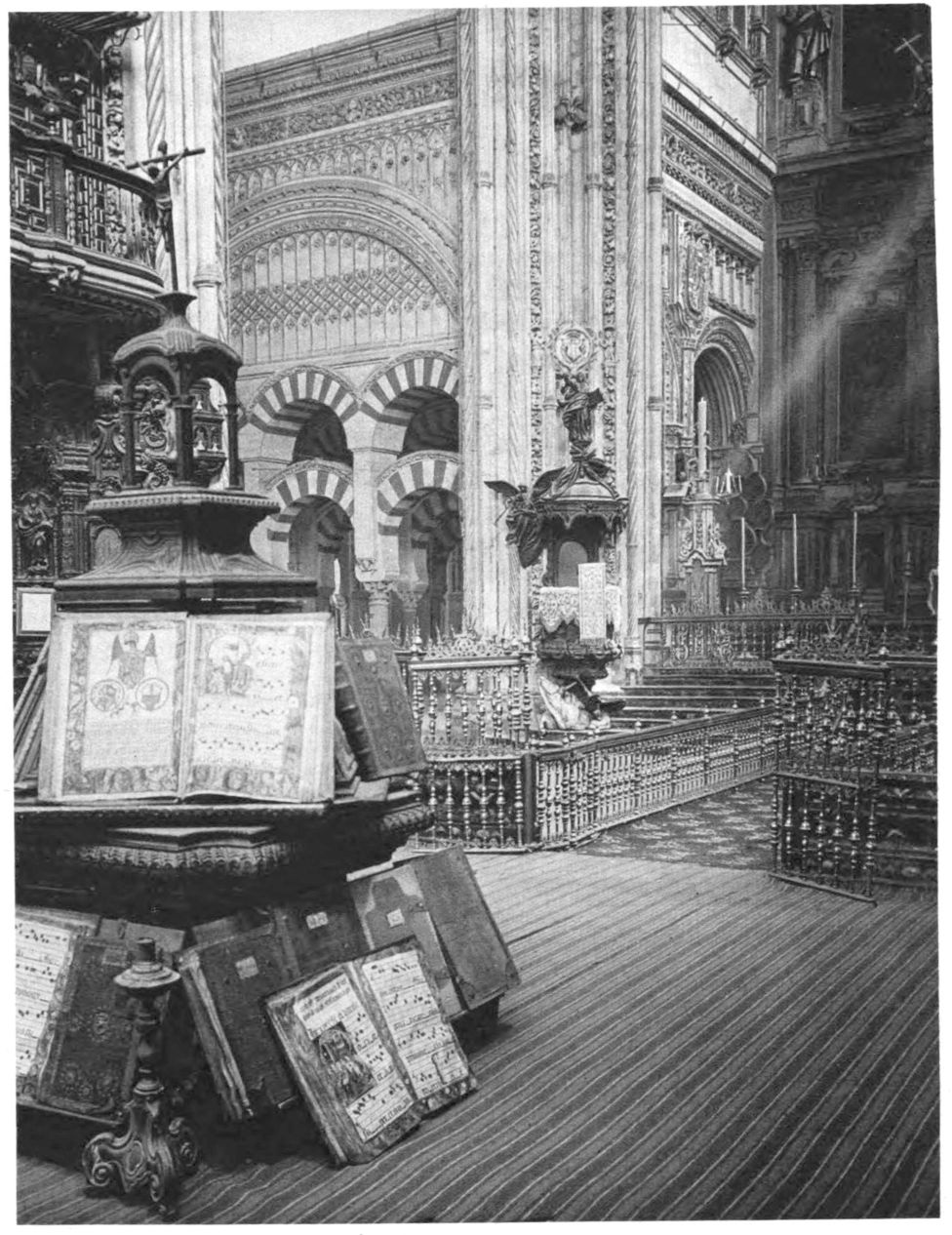

Cordoba

Mosque—View from the Choir

Mezquita—Vista desde el Coro

Moschee—Blick aus dem Choreinbau

La Mosquée vue de choeur

La Moschea: veduta del Coro

Cordoba

Mosque—Capilla de St. Fernando

Mezquita—Capilla de S. Fernando

Moschee—Capilla S. Fernando

La Mosquée: chapelle de Saint Ferdinand

La Moschea: Cappella di S. Ferdinando

Cordoba

Mosque—Capilla de St. Fernando

Mezquita—Capilla de S. Fernando

Moschee—Capilla S. Fernando

La Mosquée: chapelle de Saint Ferdinand

La Moschea: Cappella di S. Ferdinando

Cordoba

Mosque—The Court of Oranges

Mezquita—Patio de las Naranjas

Moschee—Orangenhof

La Mosquée: cour des orangers

La Moschea: La corte degli aranci

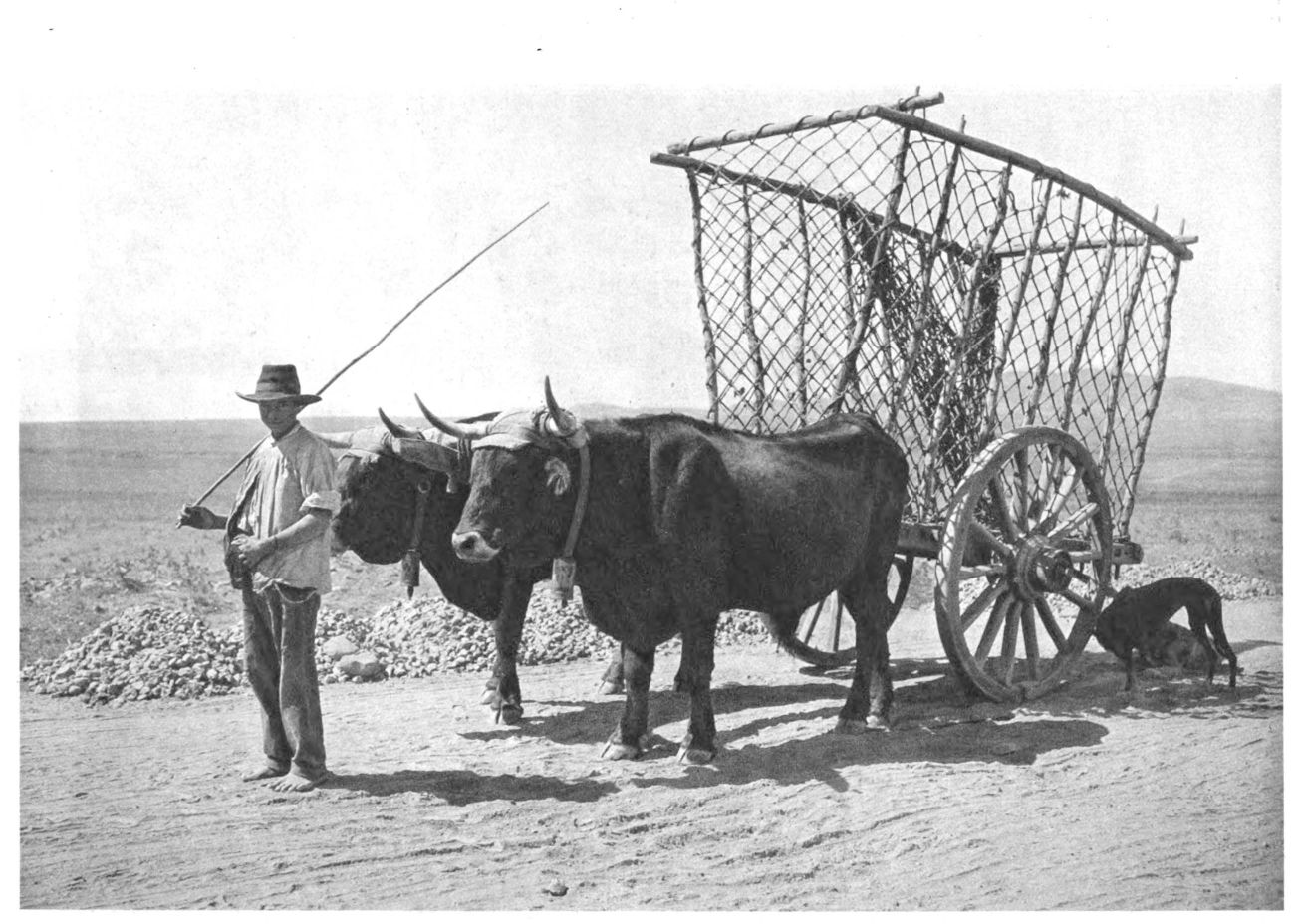

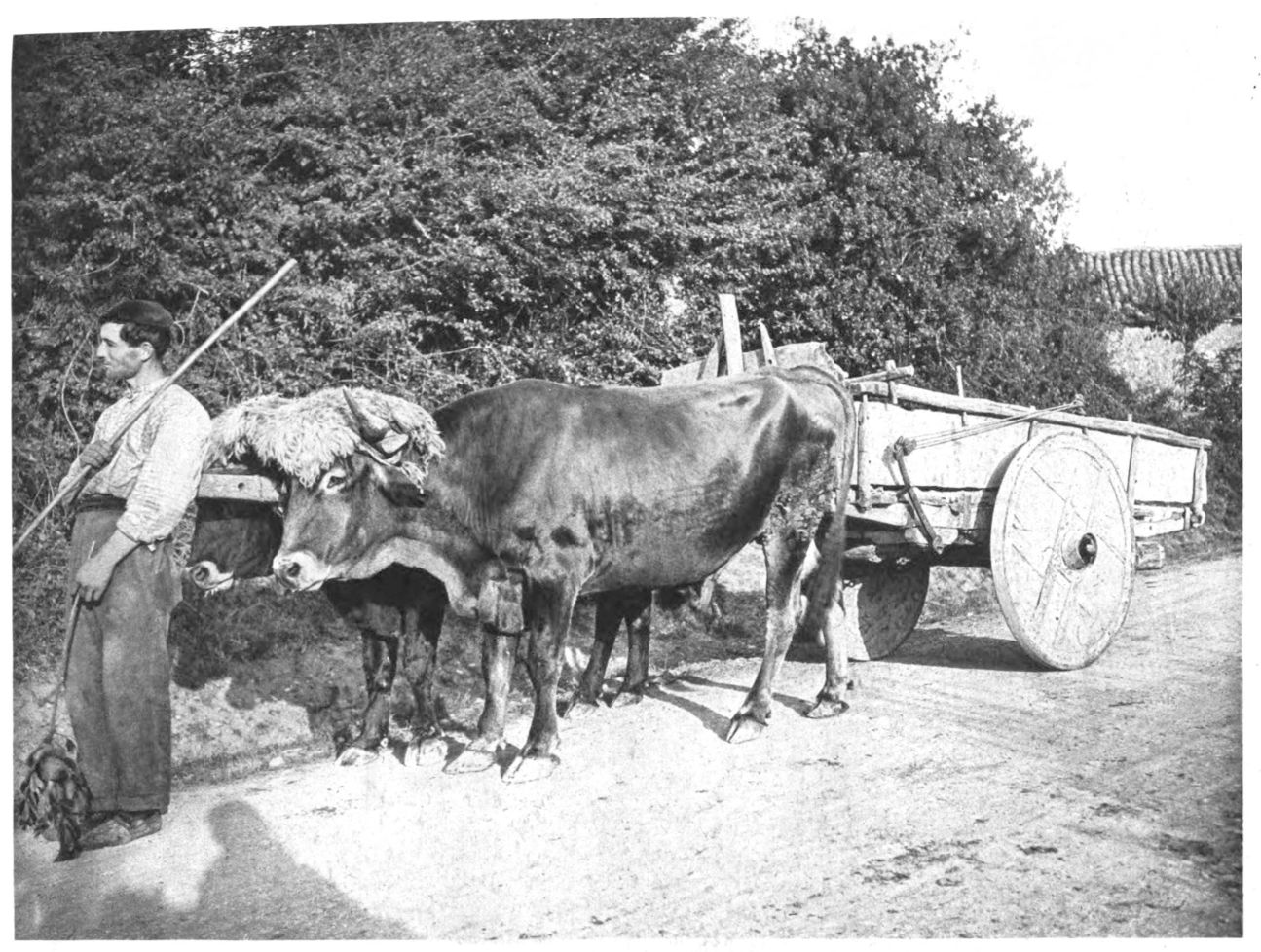

Straw Cart

Carro para cargar paja

Karren für Stroh

Une charrette pour le transport da la paille

Una carretta per il trasporto della paglia

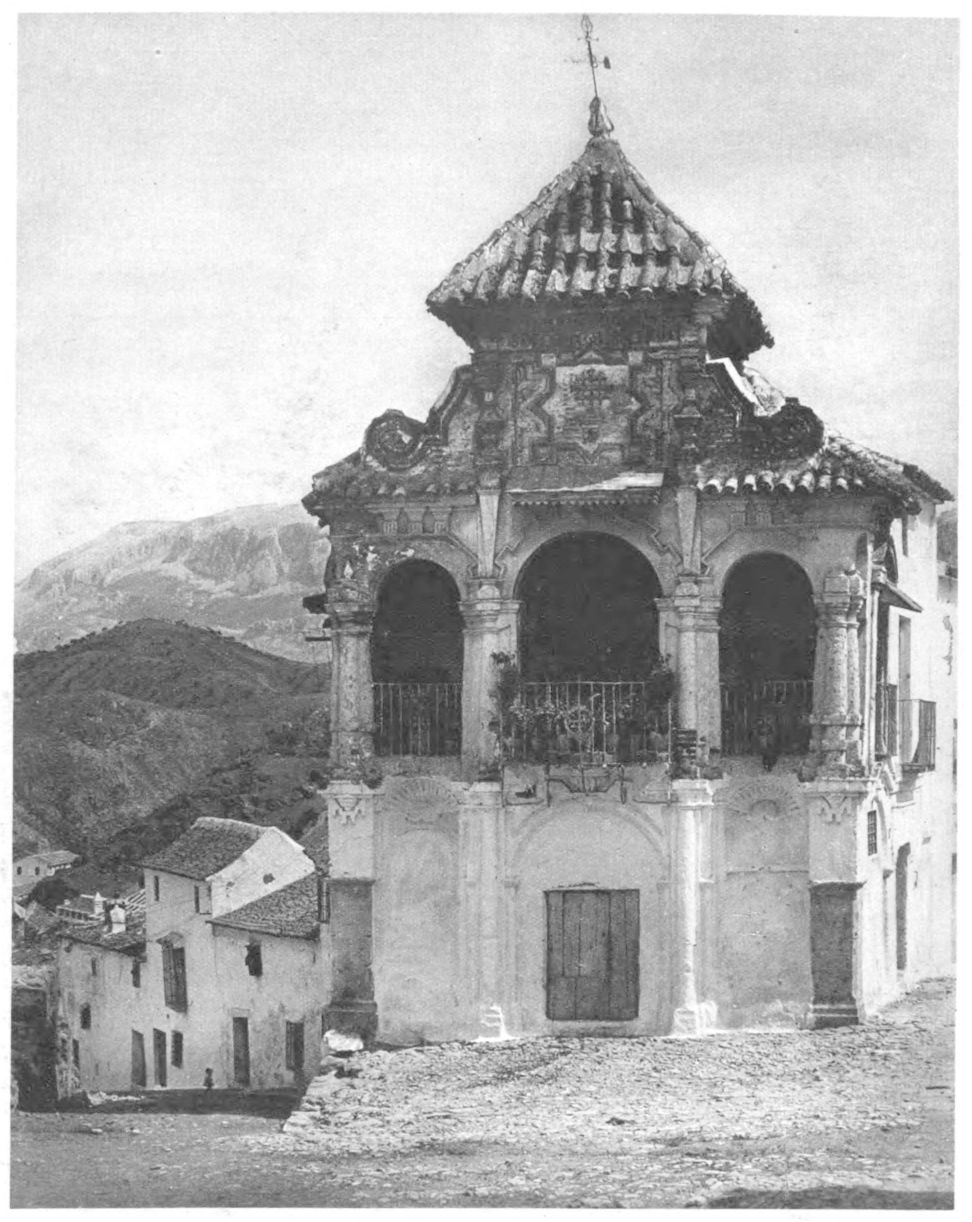

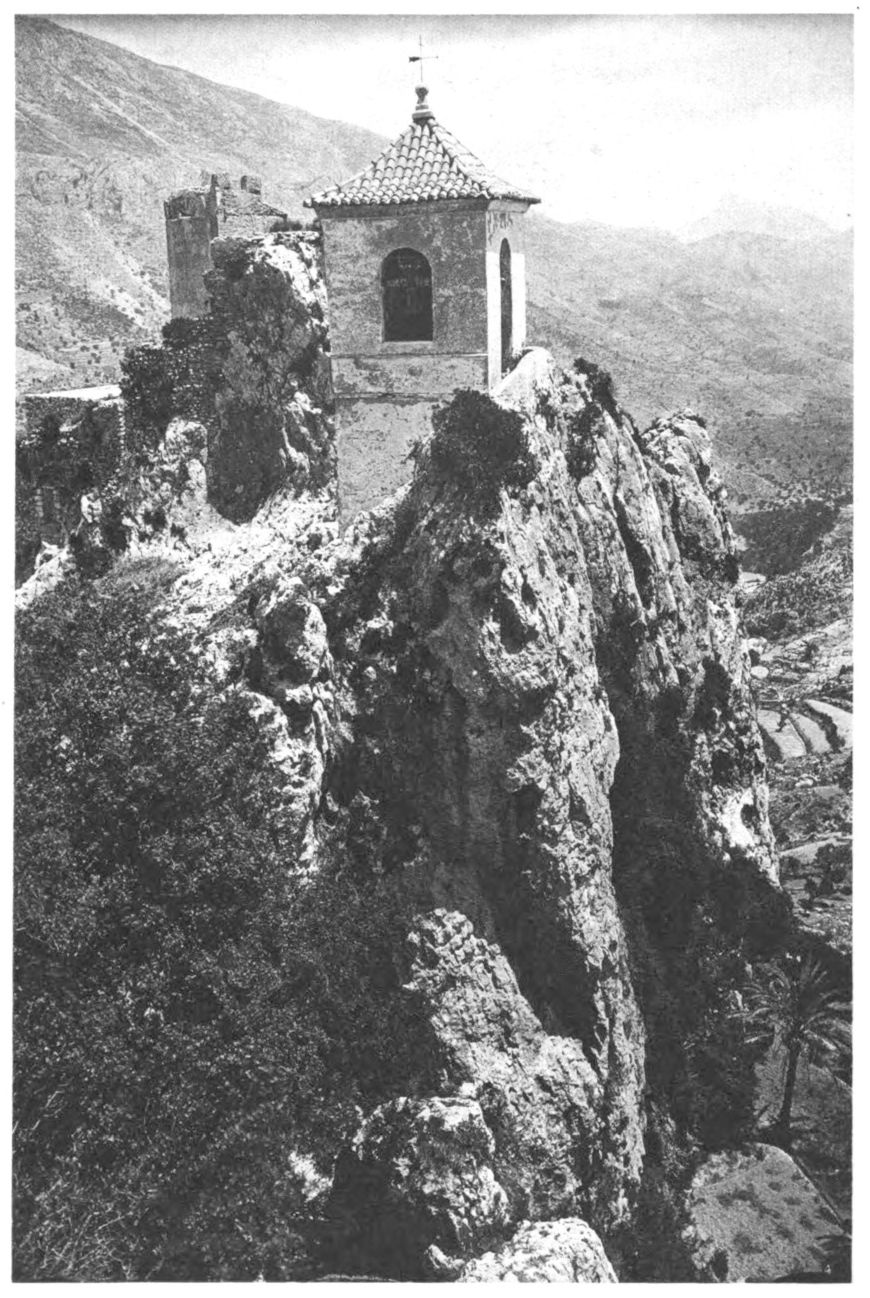

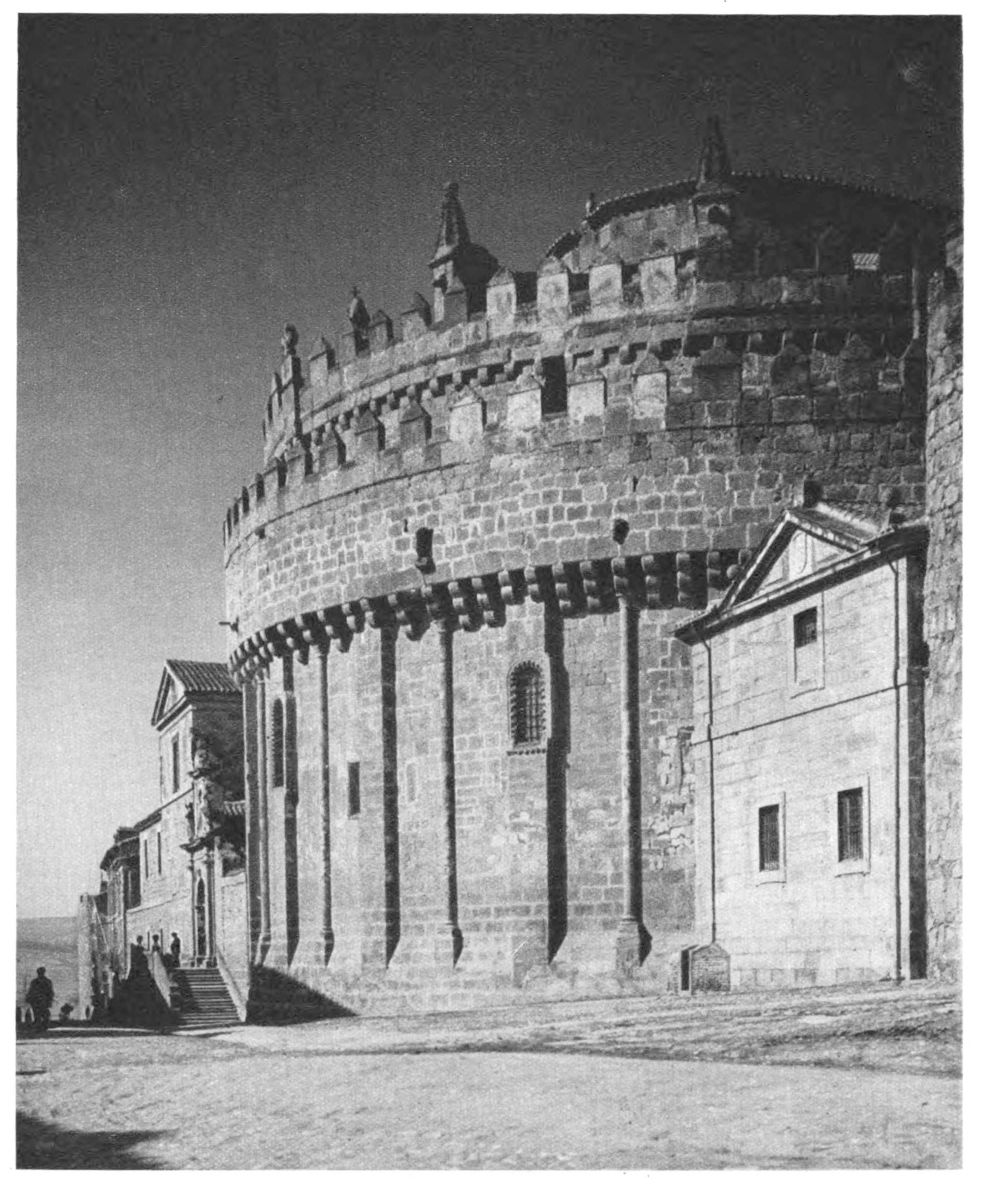

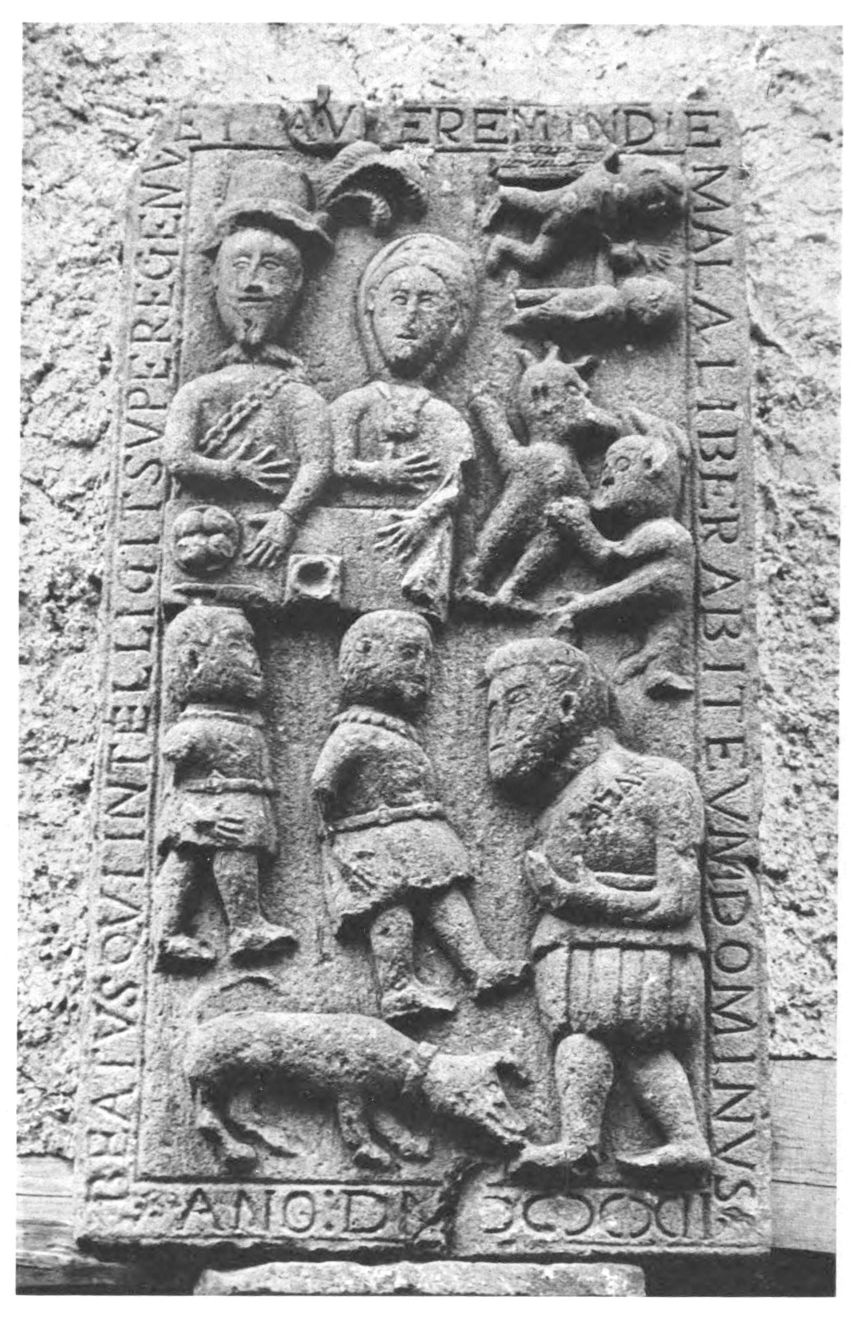

Antequera

Chapel of the Virgin of Succour

Capilla de la Virgen del Socorro

Kapelle der hilfespendenden Jungfrau

Chapelle de Notre-Dame de Bon Secours

Cappella della Madonna del Buon soccorso

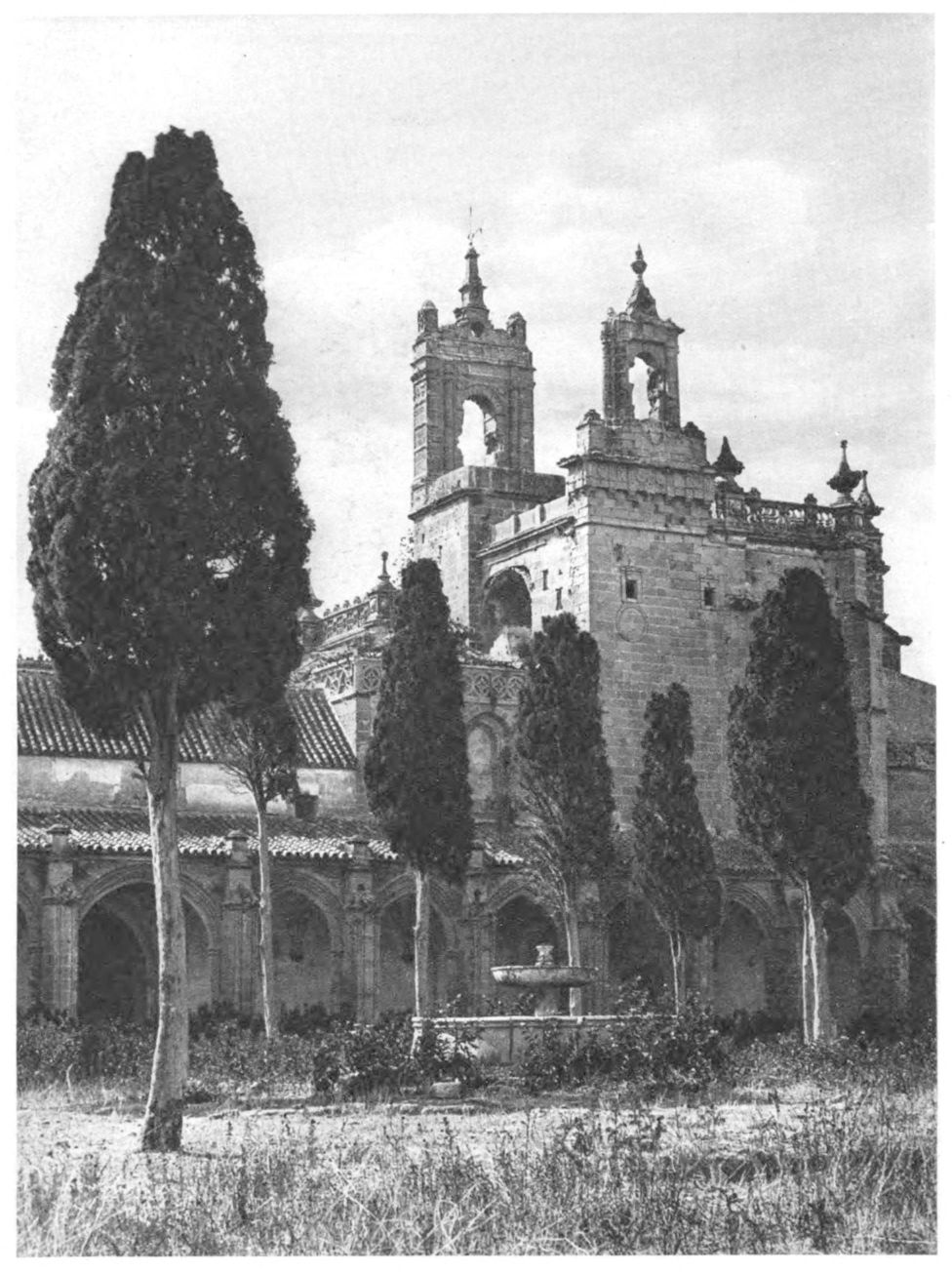

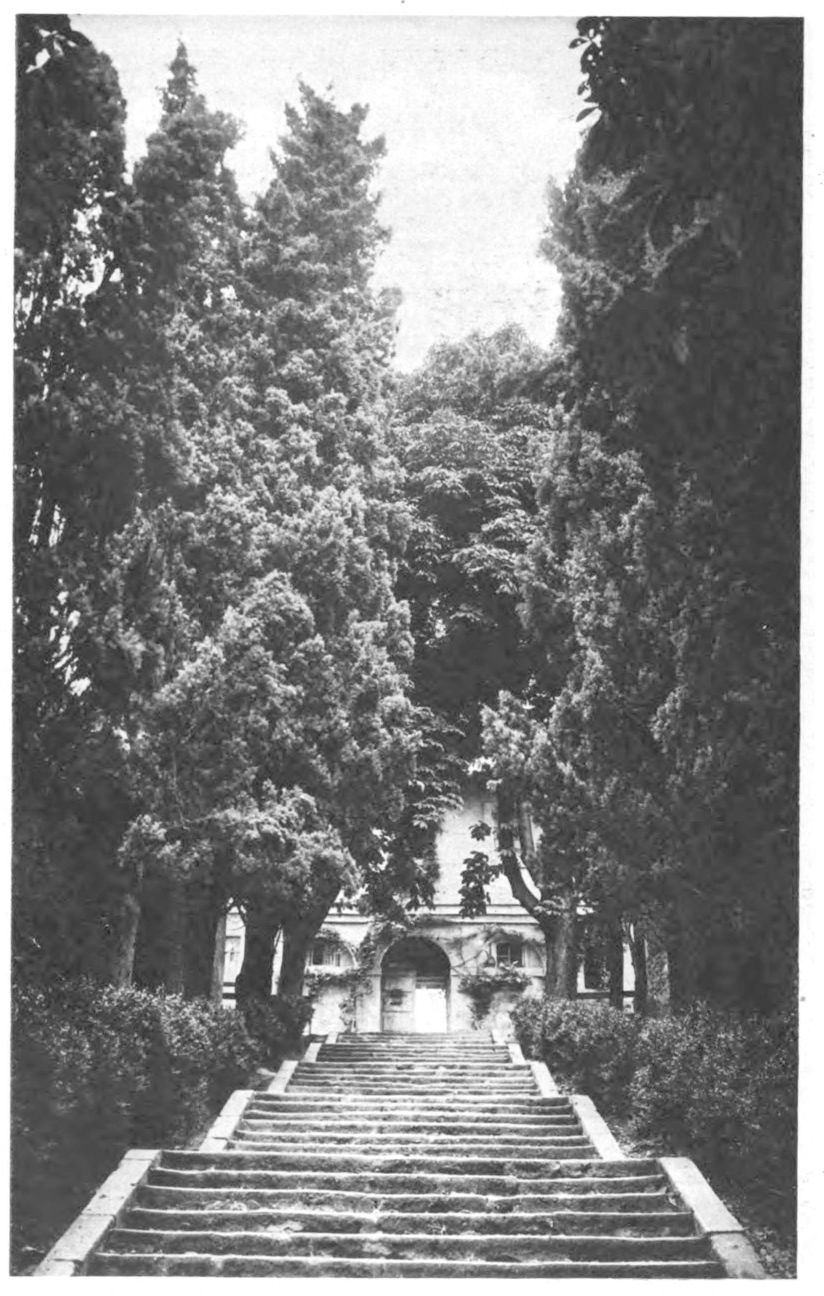

Jerez de la Frontera

Cartuja—Cypress Court

Cartuja—Patio de los cipreses

Cartuja—Zypressenhof

Cartuja: la cour des cyprès

Cartuja: Il cortile del cipressi

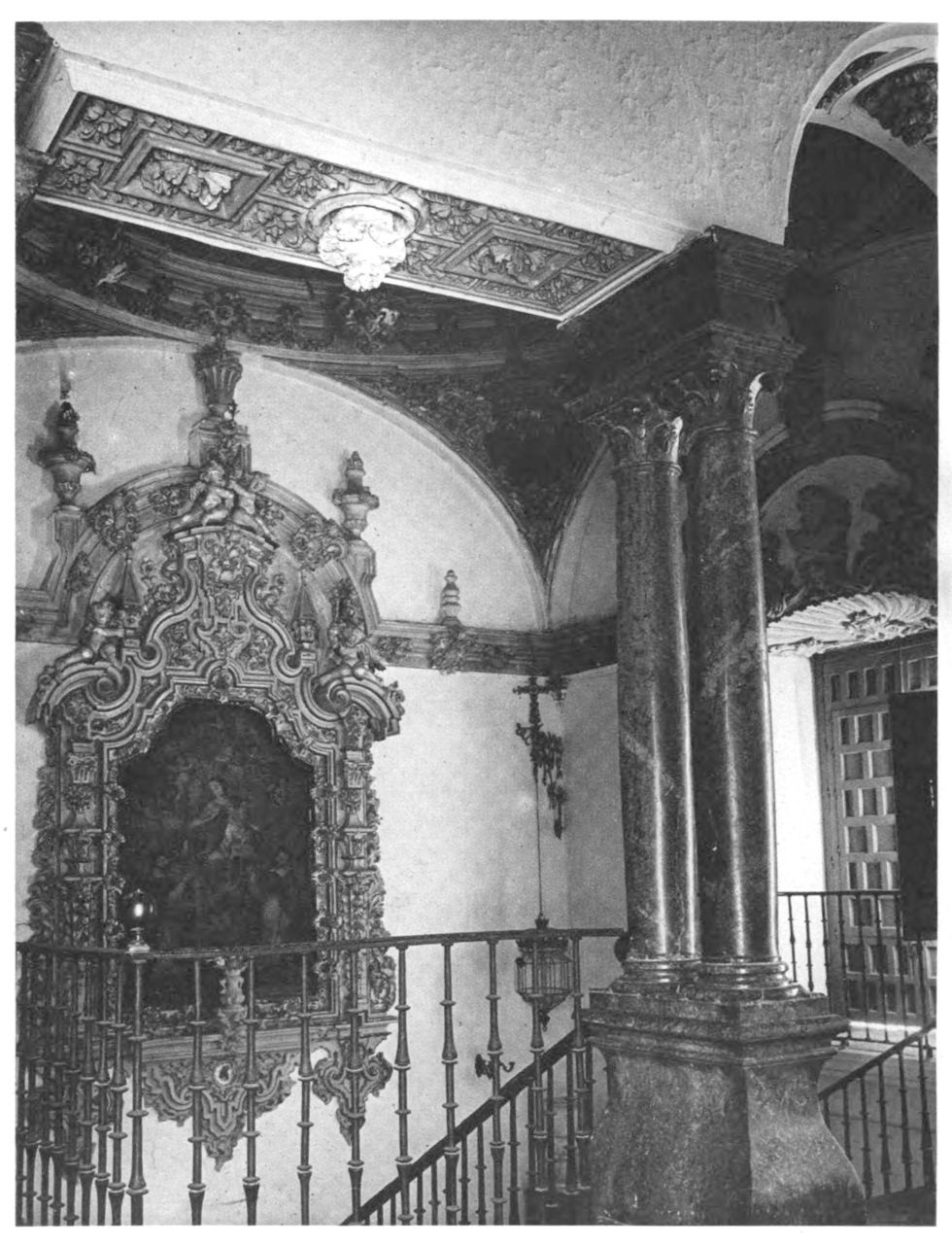

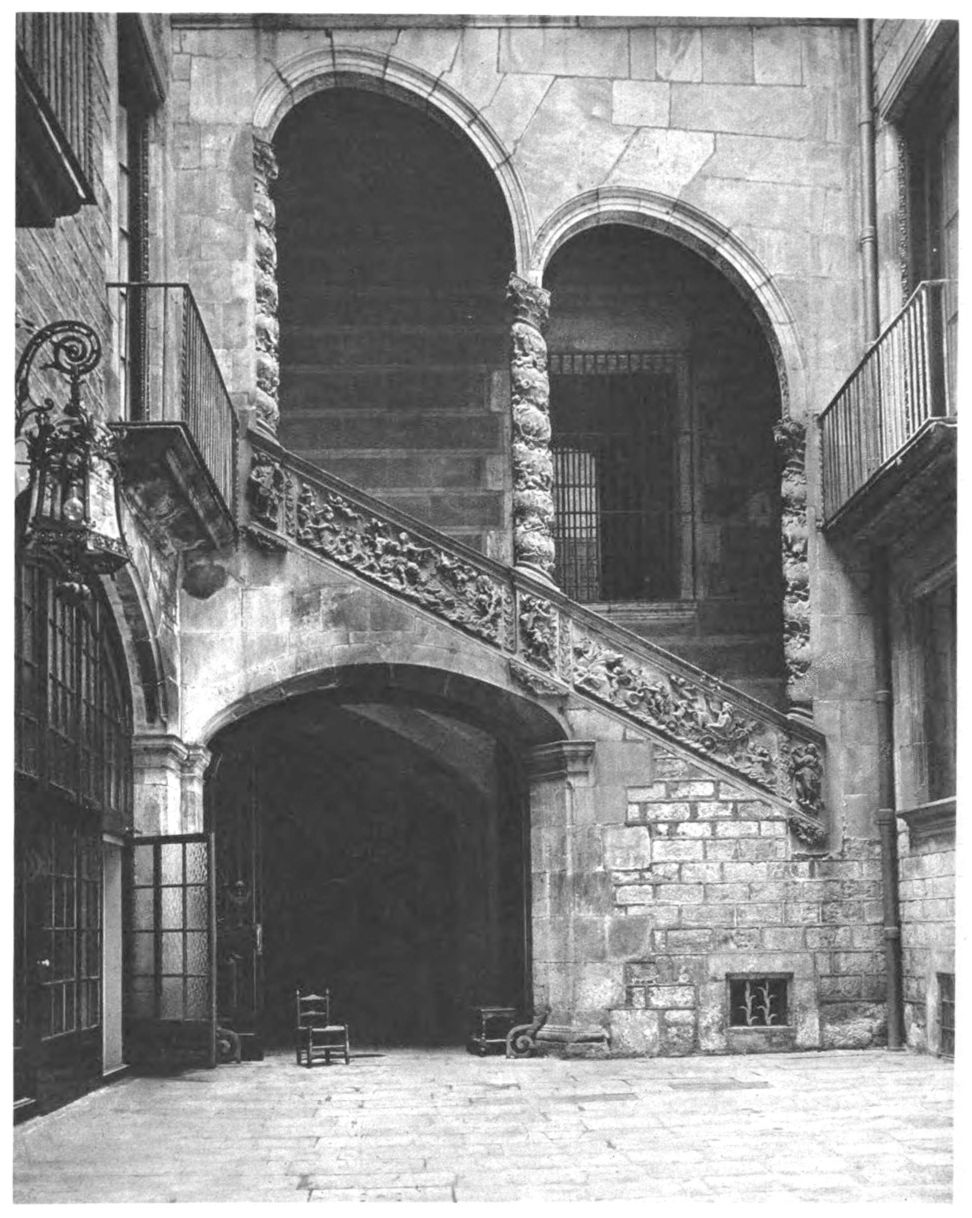

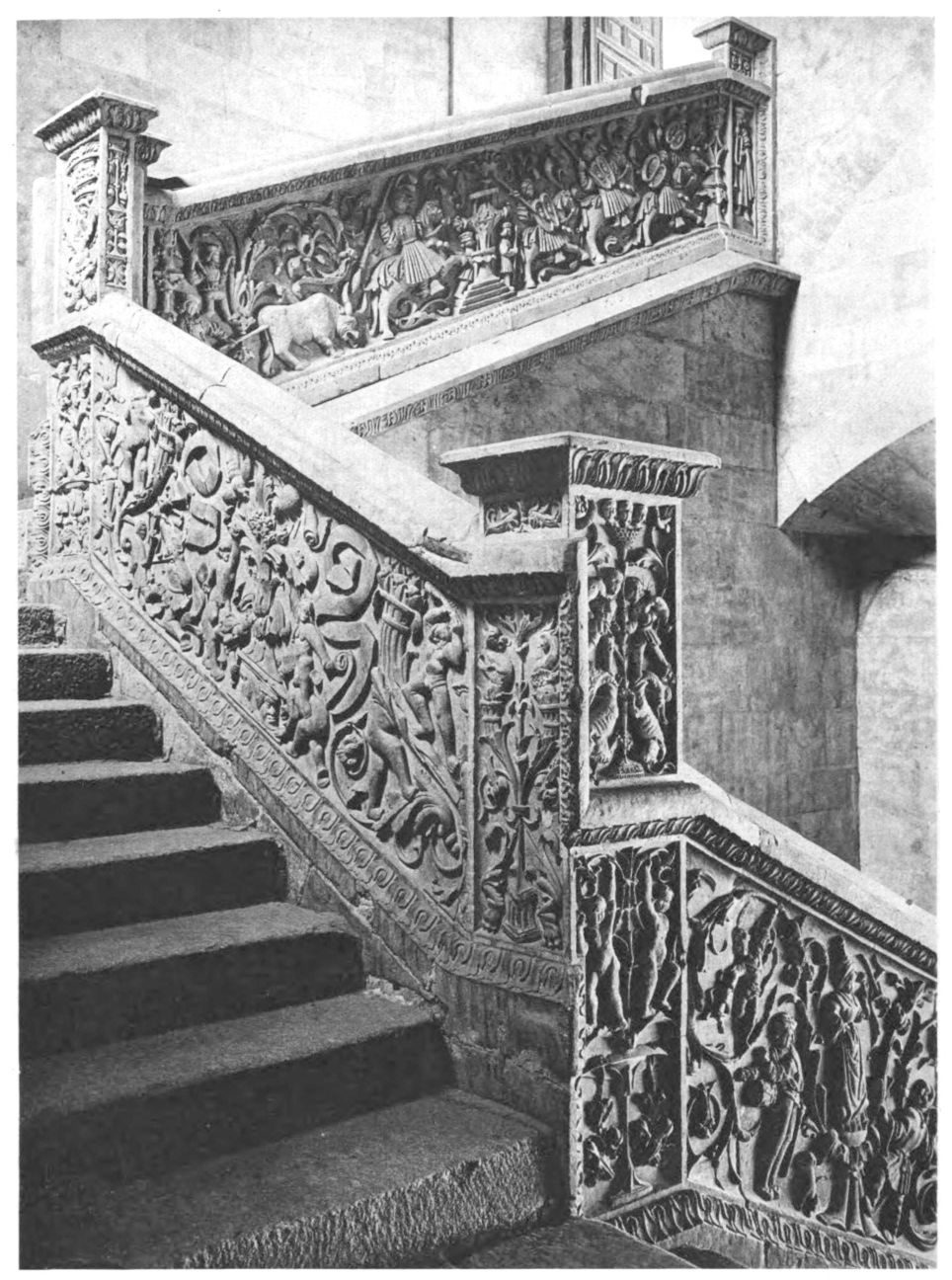

Ecija

Staircase in the Marquis of Peñaflor’s Palace

Escalera en el palacio del Marqués de Peñaflor

Treppenaufgang im Palast des Marqués de Peñaflor

Cage d’escalier au palais du marquis de Peñaflor

Scala nel palazzo del Marchese de Peñaflor

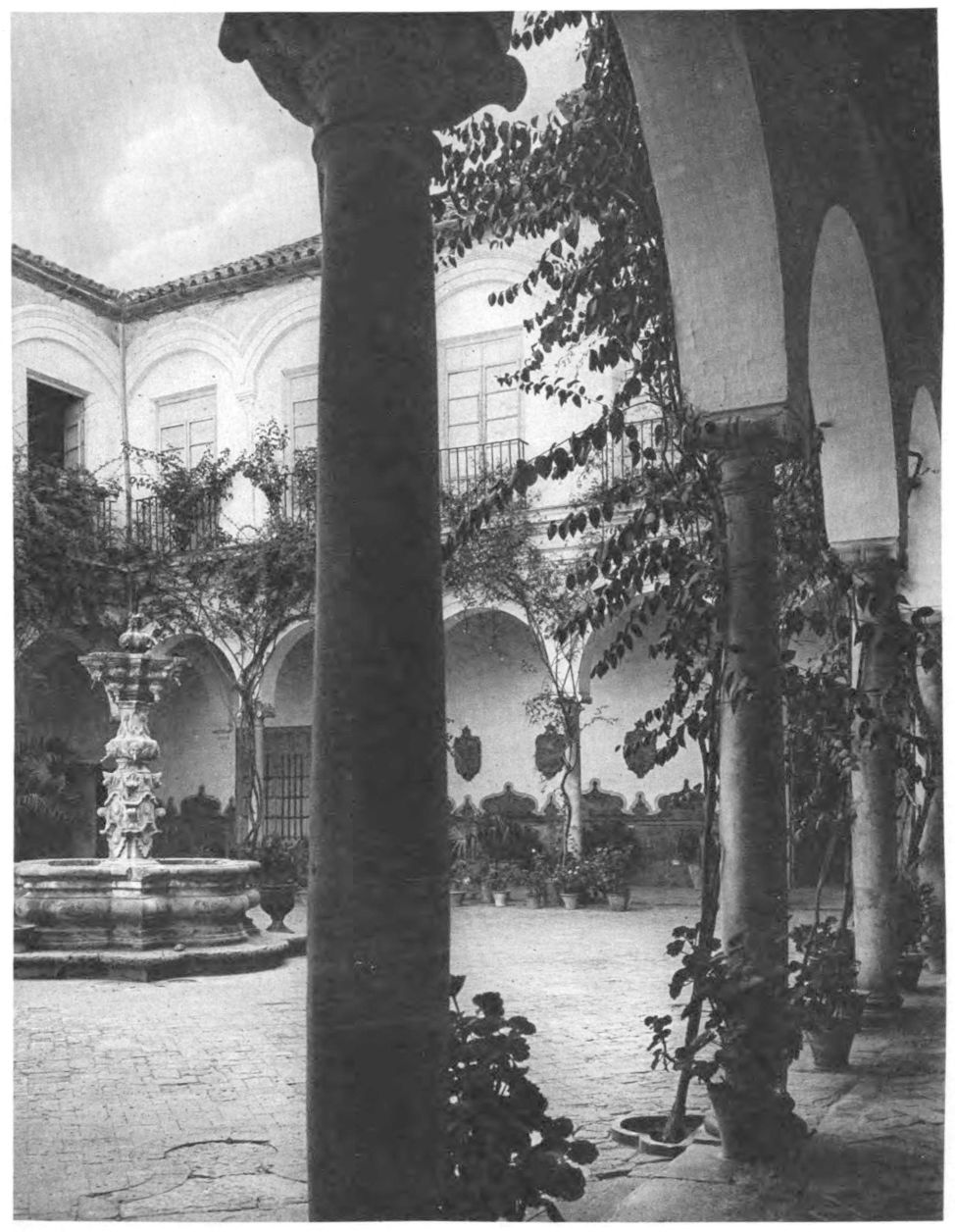

Ecija

Court In the Marquis of Peñaflor’s Palace

Patio en el palacio del Marqués de Peñaflor

Hof im Palast des Marqués de Peñaflor

Cour Intérieure du palais du marquis de Peñaflor

La Corte nell palazzo del Marchese de Peñaflor

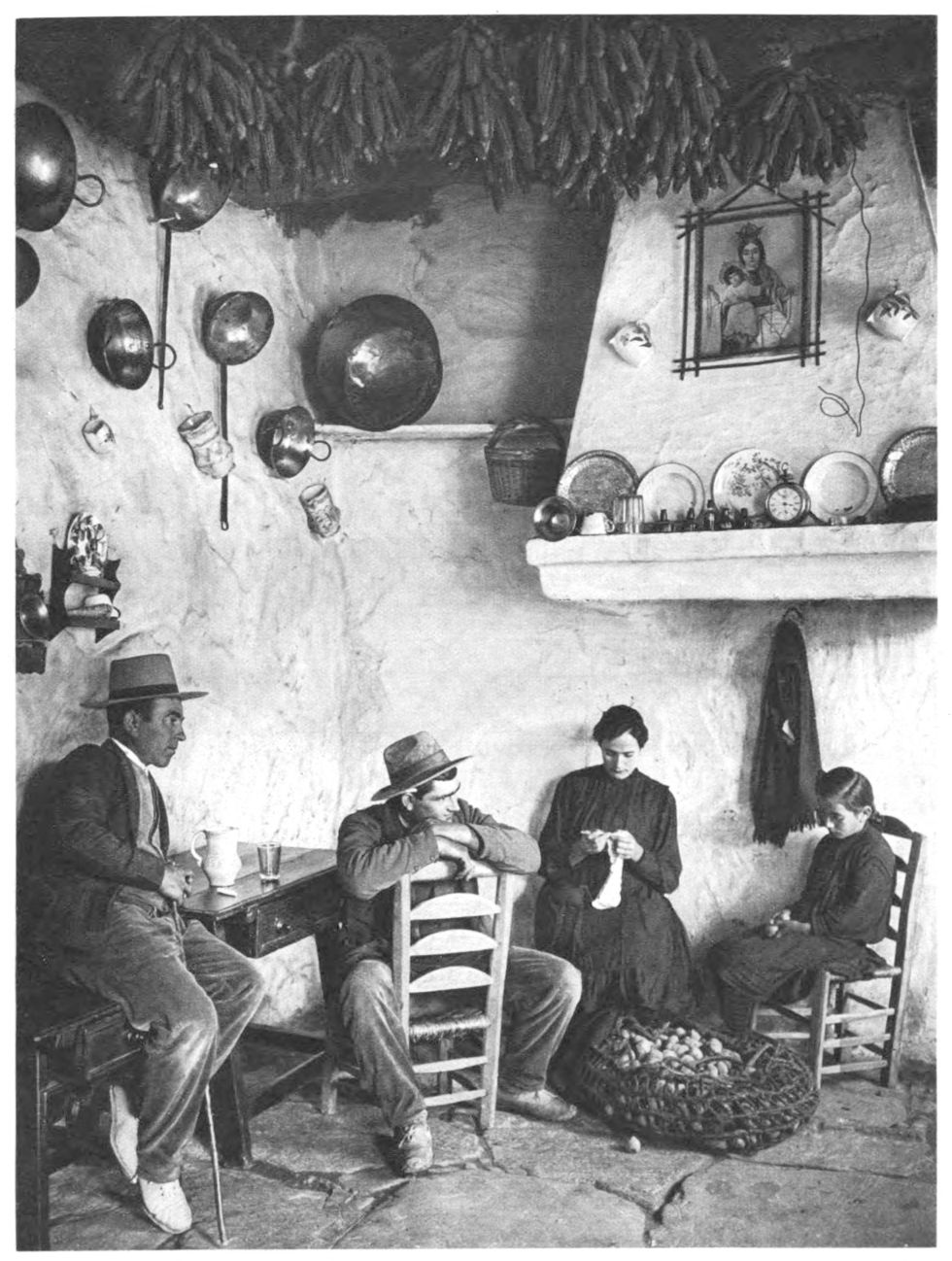

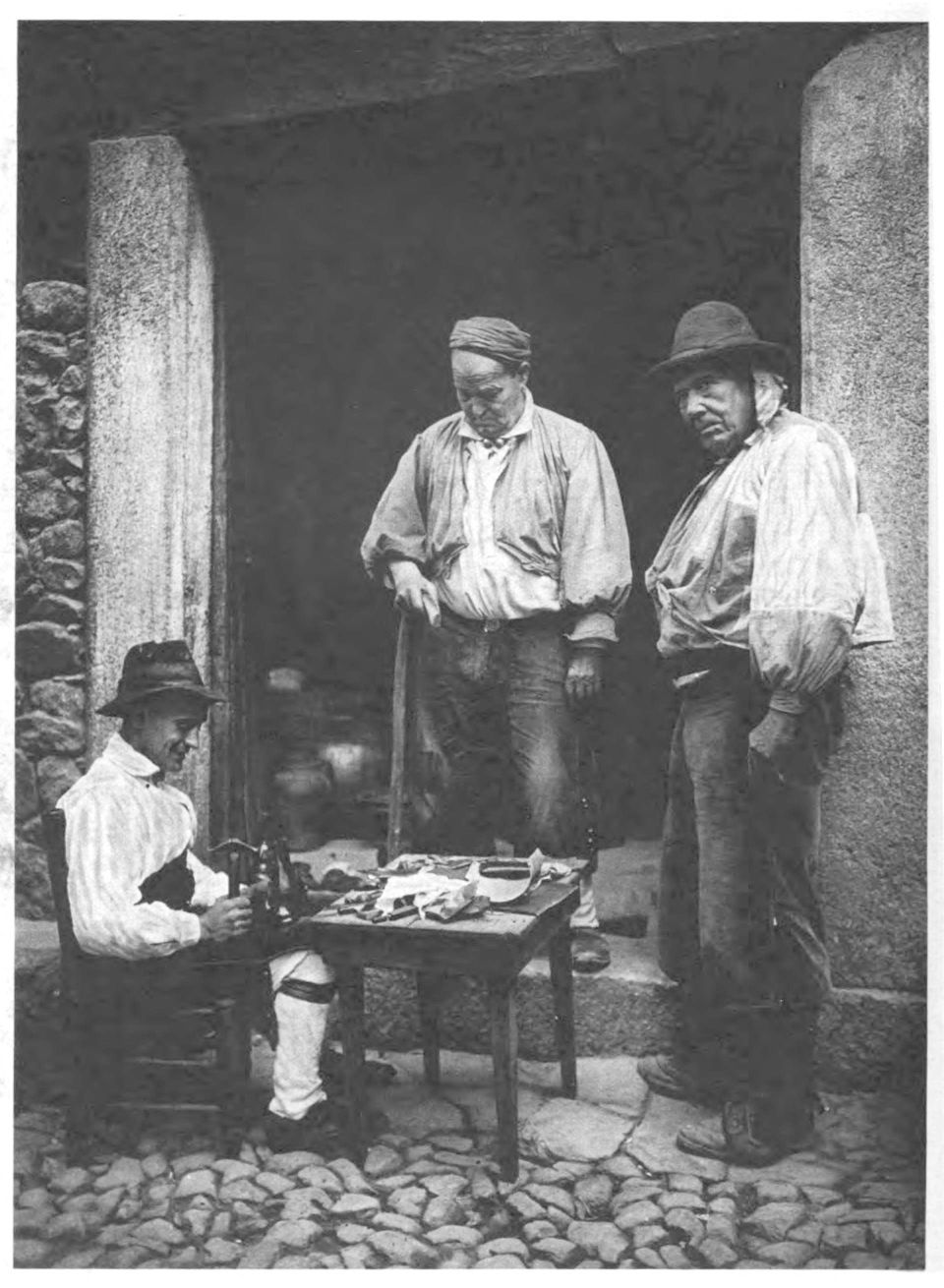

In a Wayside Inn (Sierra Nevada)

En una posada (Sierra Nevada)

In einer Wegschenke (Sierra Nevada)

Intérieure d’une posada (auberge) da la Sierra Nevada

In una trattoria. Sierra Nevada

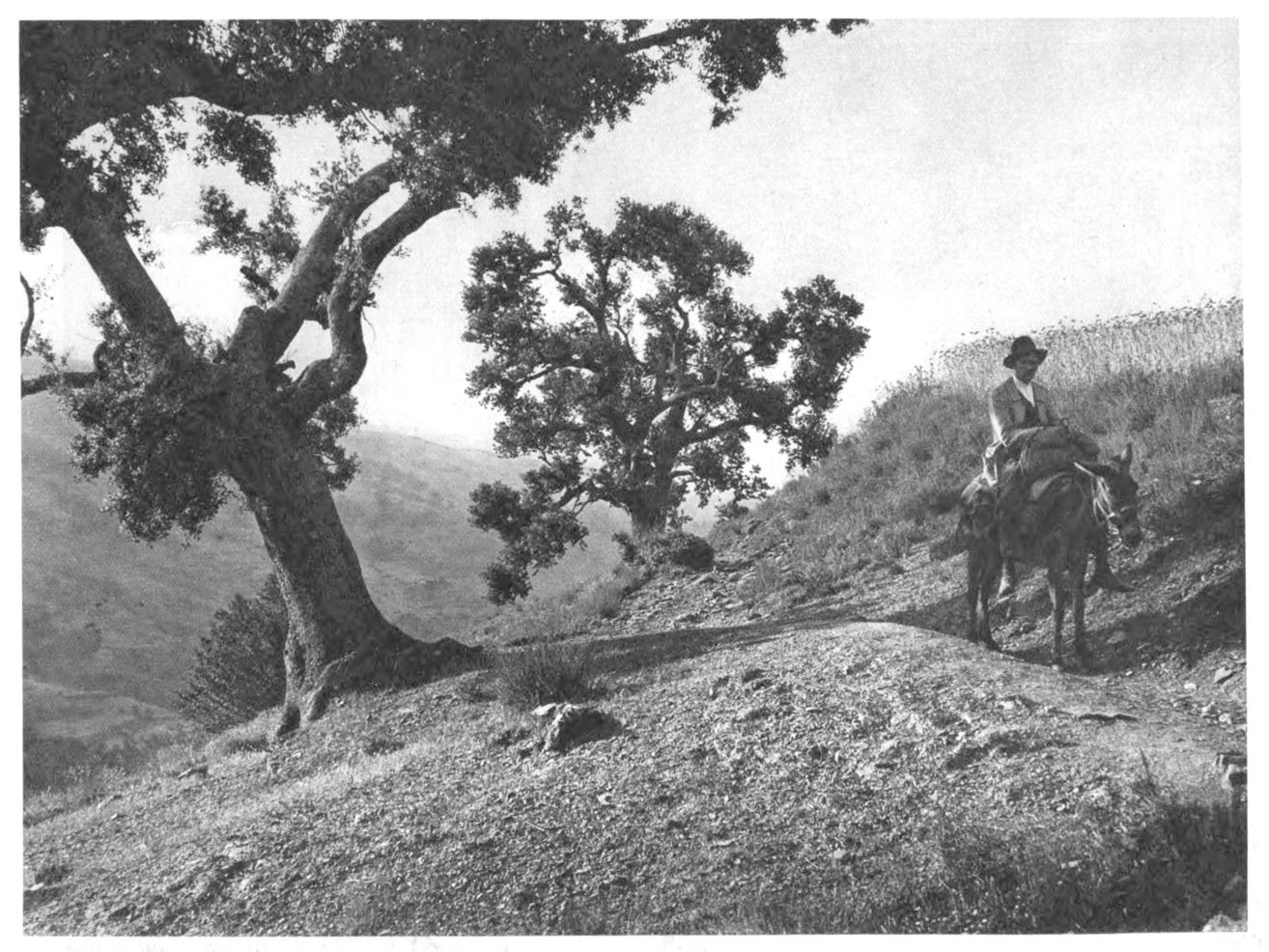

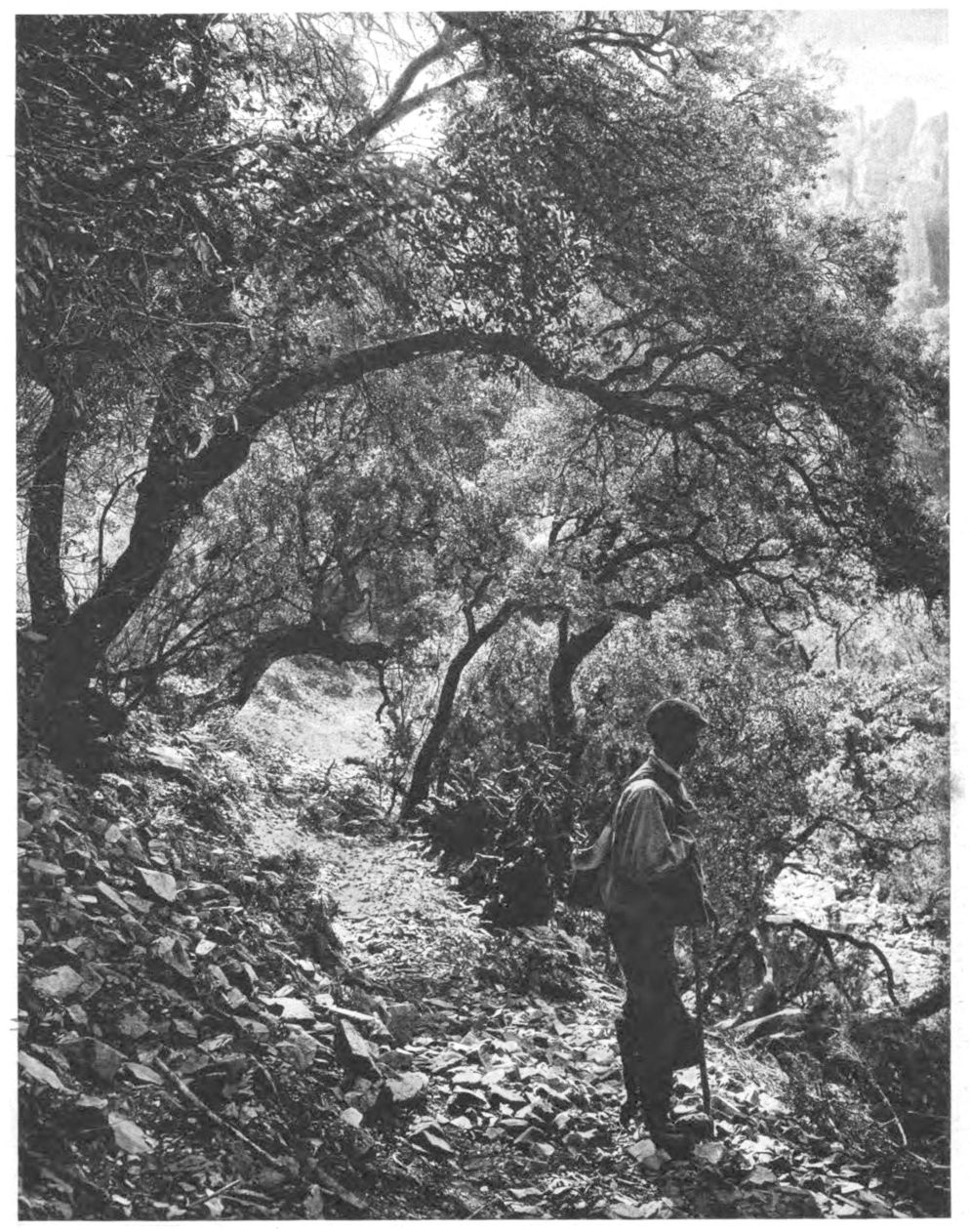

In the Sierra Nevada (Holm Oak)

En la Sierra Nevada

In der Sierra Nevada (Steineichen)

Chênes rouvres dans la Sierra Nevada

Nella Sierra Nevada. Lecci

Zafra

Court in St. Miguel’s Hospital

Patio en el hospital de S. Miguel

Hof im Hospital S. Miguel

Cour de l’hopital Saint-Michel

Ospedale di S. Michele. Il cortile

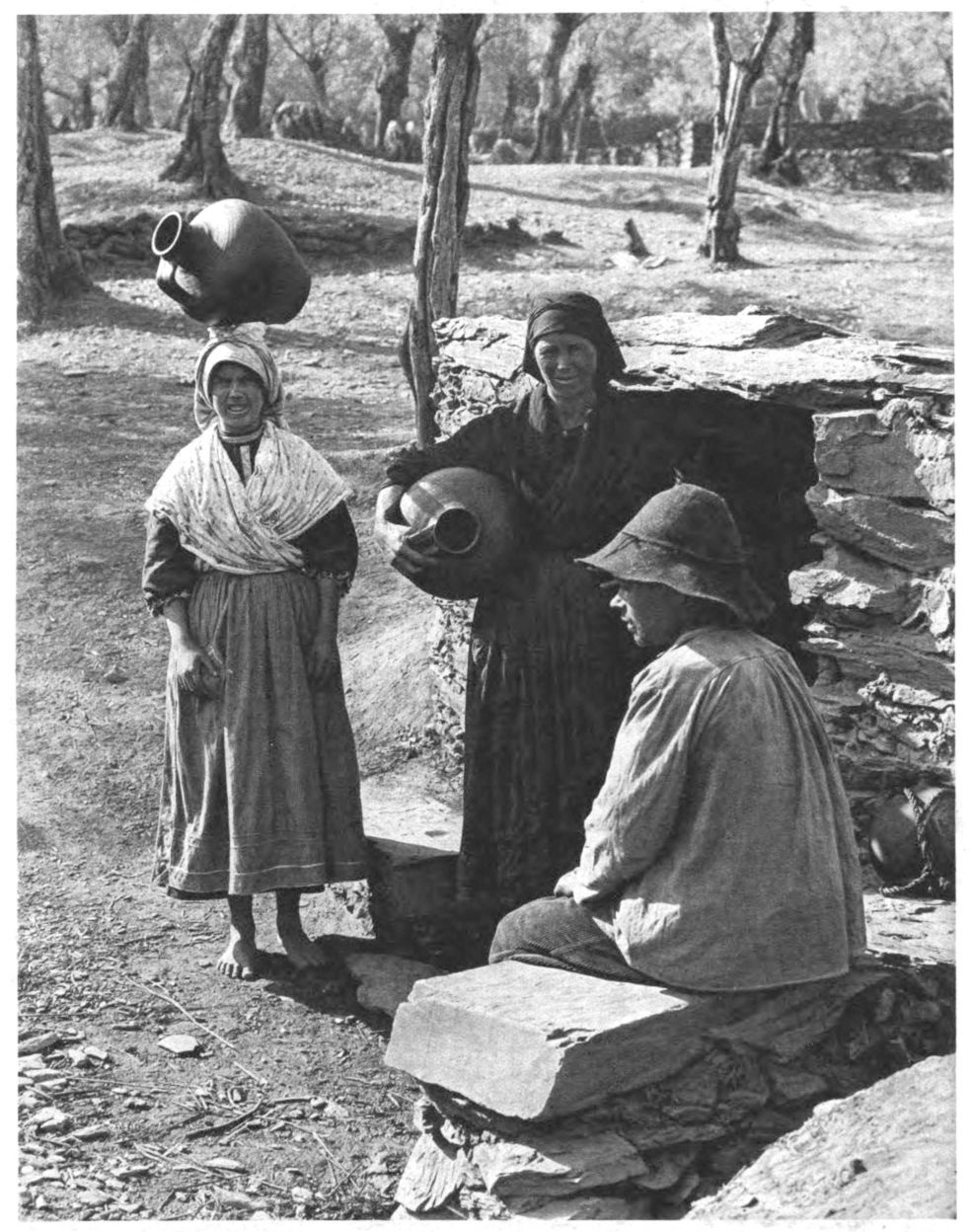

Cáceres

Water-Carriers

Mujeres con jarros de agua

Wasserträgerinnen

Porteuses d’eau

Portatrici d’acqua

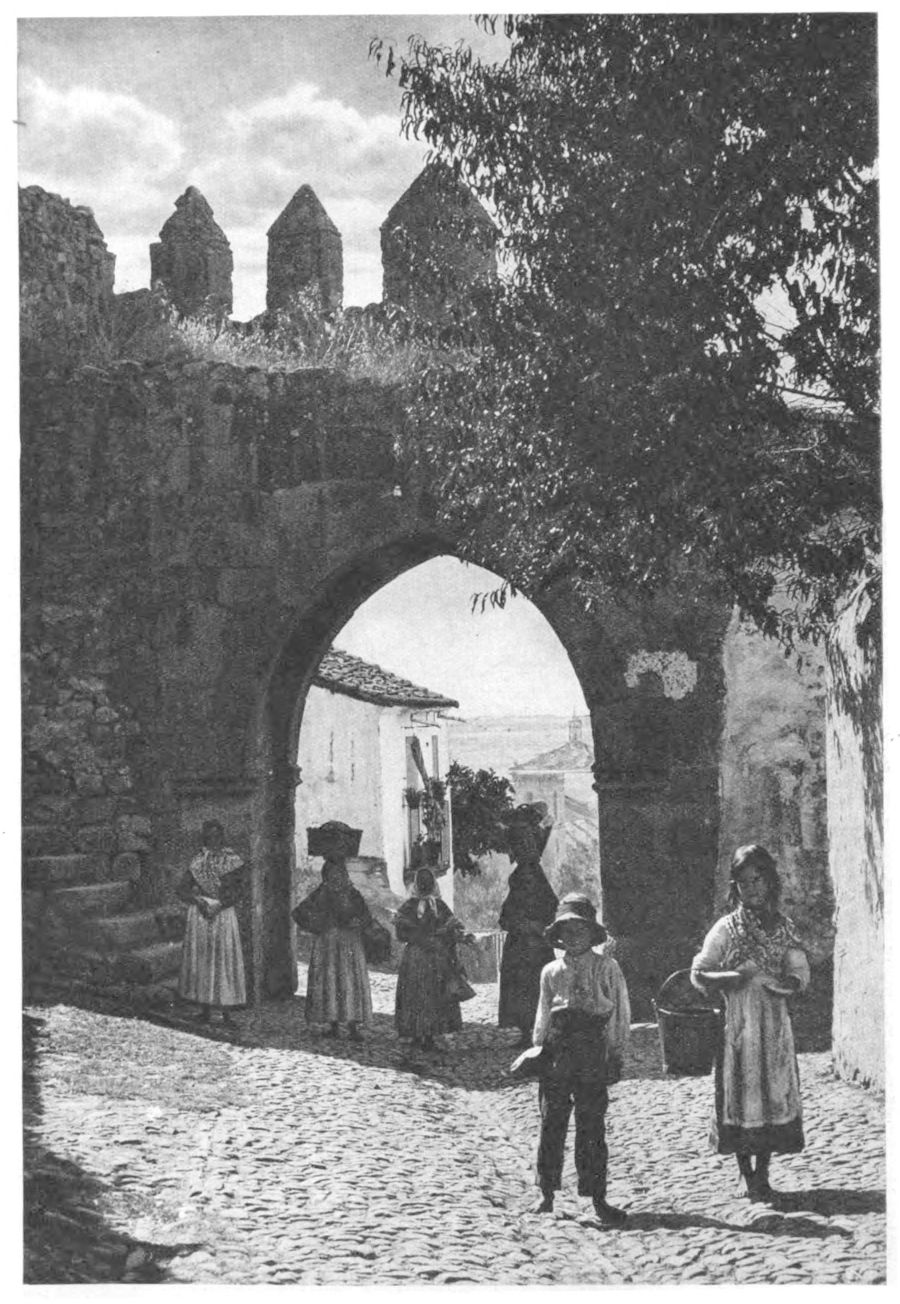

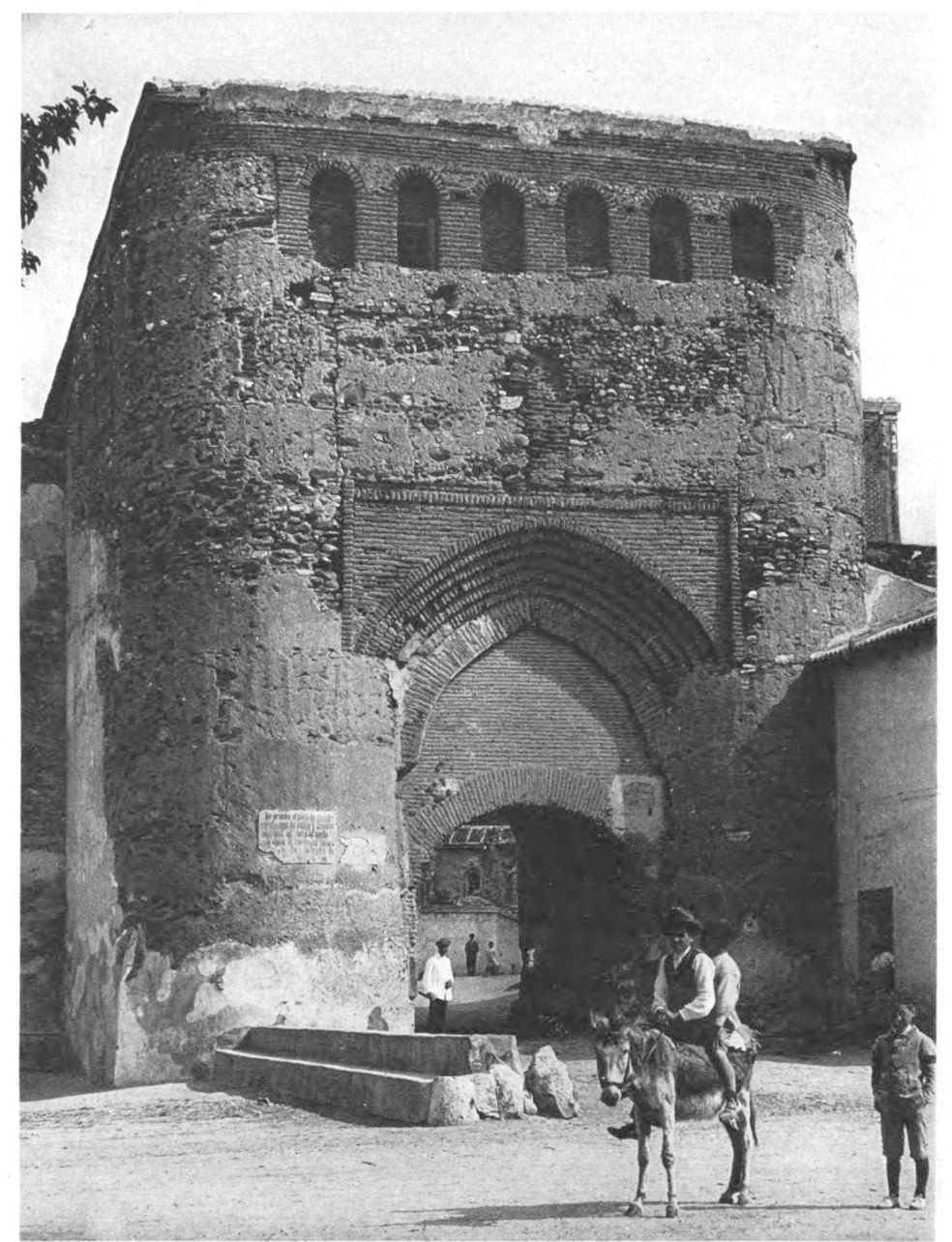

Trujillo

Old Town-Gate

Puerta antigua

Altes Stadttor

Vieille porte d’entrée

Un’antica porta della città

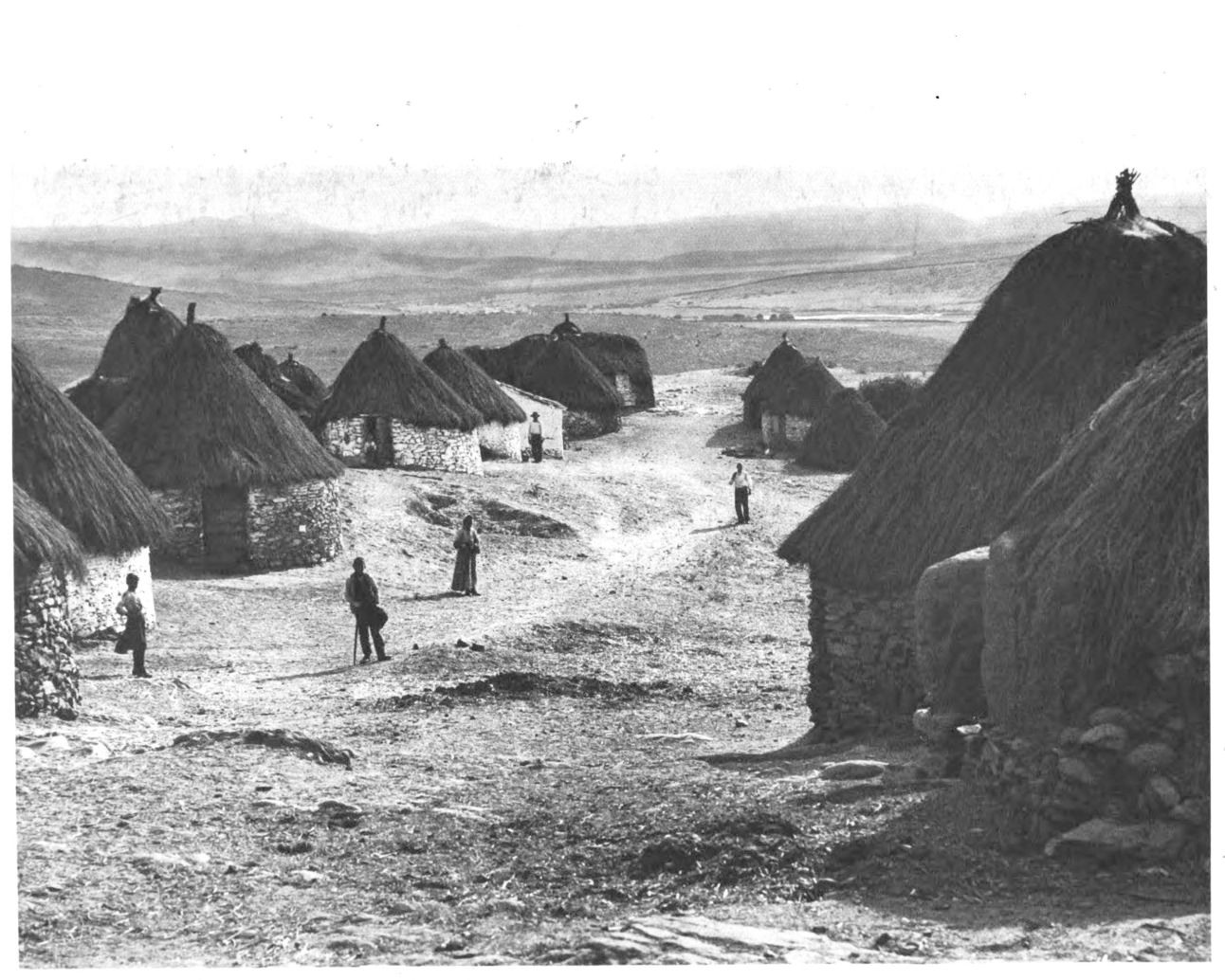

Village in South Estremadura

Aldehuela en el sur de Estremadura

Dorf in Süd-Estremadura

Un village de l’Estremadura méridionale

Villagio di capanne nell’ Estremadura meridionale

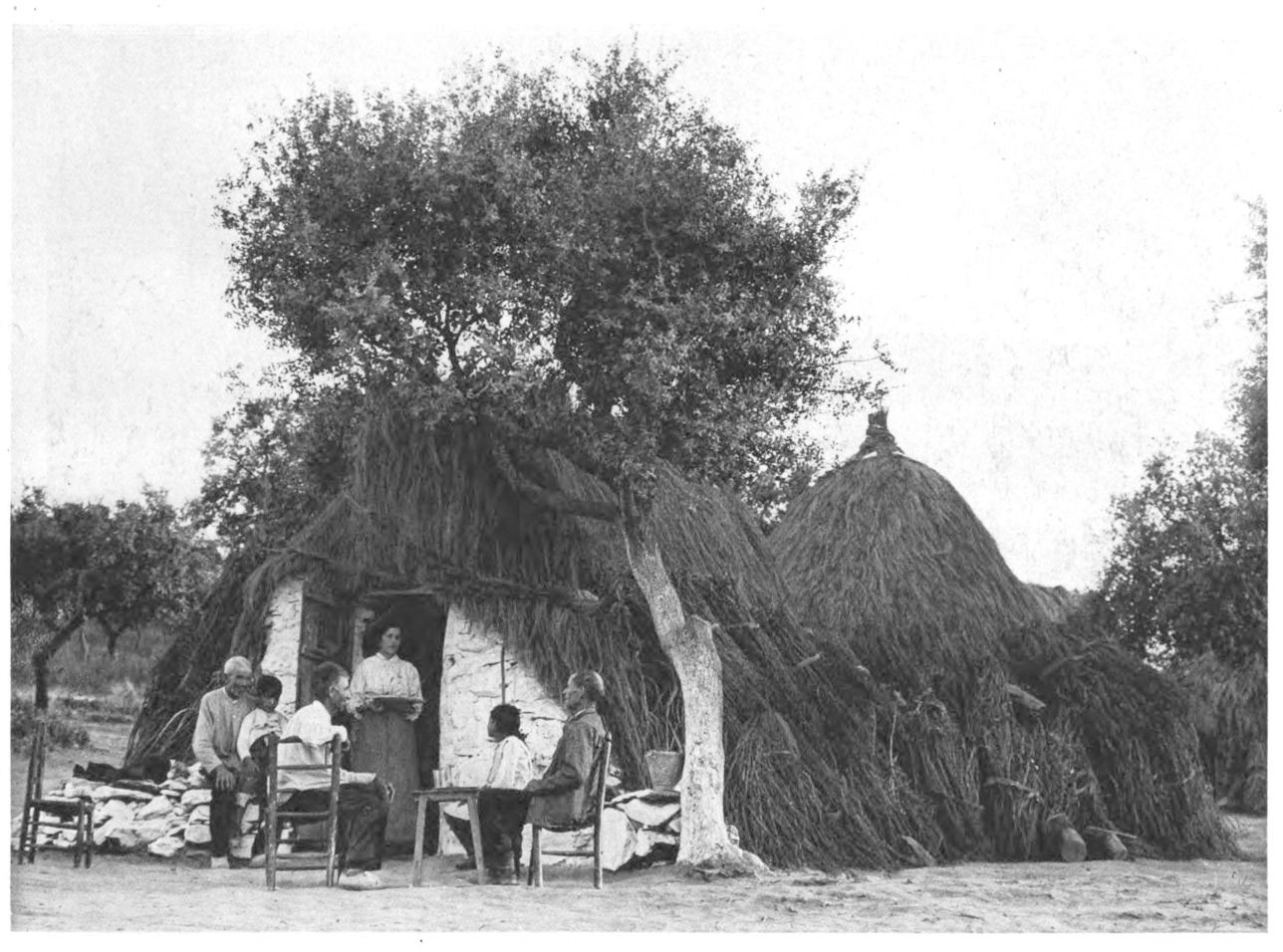

Inn (South Estremadura)

Venta (en el sur de Estremadura)

Schenke (Süd-Estremadura)

Une buvette dans l’Estremadure méridionale

Osteria (Estremadura meridionale)

Moorish women of Christian persuasion who still wear the veil in Mochagar-Vejer

Mujer en Mochagar-Vejer llevando la cara tapada como las marroquínas

Eine der noch heut maurisch verschleiert gehenden Christenfrauen in Mochagar-Vejer

Une des femmes chrétiennes qui vont encore voilées aujourd’hui comme au temps des Maures d’Espagne

Una donna cristiana che va ancor oggi velata all’uso marocchino

Cave Dwellings (Province of Almeria) None of the caves shown in this book are prehistoric. They are still excavated and inhabited

Cuevas en las rocas (Prov. de Almería)

Höhlenfels (Prov. Almeria) Alle in diesem Werk wiedergegebenen Höhlen sind nicht vorgeschichtlich; sie werden noch jetzt gegraben und bewohnt

Cavernes dans le roc. (Province d’Almeria) Toutes ces cavernes ne sont pas des formations préhistoriques; on en creuse maintenant encore pour les habiter.

Caverne nella roccia (Provincia d’Almeria) Tutte le caverne riprodotte in quest’opera non sono di formazione preistorica, ma si contina a scavarle anche al giorno d’oggi

Cave Dwellings (Province of Almeria)

Cuevas en las rocas (Prov. de Almería)

Höhlenfels (Prov. Almeria)

Cavernes dans le roc (Province d’Almeria)

Caverne nella roccia (Provincia d’Almeria)

Cave Dwellings (Province of Almeria)

Cuevas en las rocas (Prov. de Almería)

Höhlenfels (Prov. Almeria)

Cavernes dans le roc (Province d’Almeria)

Caverne nella roccia (Provincia d’Almeria)

Cave Dwellings (Province of Almeria)

Cuevas en las rocas (Prov. de Almería)

Höhlenfels (Prov. Almeria)

Cavernes dans le roc (Province d’Almeria)

Caverne nella roccia (Provincia d’Almeria)

Cave Town (Sierra de Guadix) The chimneys of the dwellings are seen projecting out of the rocks

Población de cuevas (Sierra de Guadix) Se ven las chimeneas de las cuevas, saliendo de tierra

Höhlenstadt (Sierra de Guadix) Aus der Erde ragen die Schornsteine der Wohnhäuser hervor

Une ville souterraine (Sierra de Guadix) On ne voit surgir de terre que les cheminées des habitations

Una città di caverne (Sierra de Guadix) Si vedono sorgere dal suolo i camini delle caverne

Cave Town (Sierra de Guadix)

Población de Cuevas (Sierra de Guadix)

Höhlenstadt (Sierra de Guadix)

Habitations souterraines (Sierra de Guadix)

(Sierra de Guadix) Città di caverne

Cave Town (Sierra de Guadix)

Población de Cuevas (Sierra de Guadix)

Höhlenstadt (Sierra de Guadix)

Habitations souterraines (Sierra de Guadix)

Città di caverne (Sierra de Guadix)

Cave Town (Sierra de Guadix)

Población de Cuevas (Sierra de Guadix)

Höhlenstadt (Sierra de Guadix)

Habitations souterraines (Sierra de Guadix)

Città di caverne (Sierra de Guadix)

In the Palm Forest of Elche

Las palmeras de Elche

Im Palmenwald von Elche

Elche: au milieu des palmiers

Il palmizio di Elche

In the Palm Forest of Elche (A date-picker in the tree-top)

Las palmeras de Elche

Im Palmenwald von Elche (Im Baumwipfel ein Dattelpflücker)

Elche: la récolte des dattes. (L’homme grimpé au sommet du palmier en détachera les régimes de fruits)

Nel palmizio di Elche (Sulla palma un uomo che coglie datteri)

Elche

Evening in the Palm Forest

Caia la tarde

Abend im Palmenhain

Effet de soir

Il tramonto nel palmizio

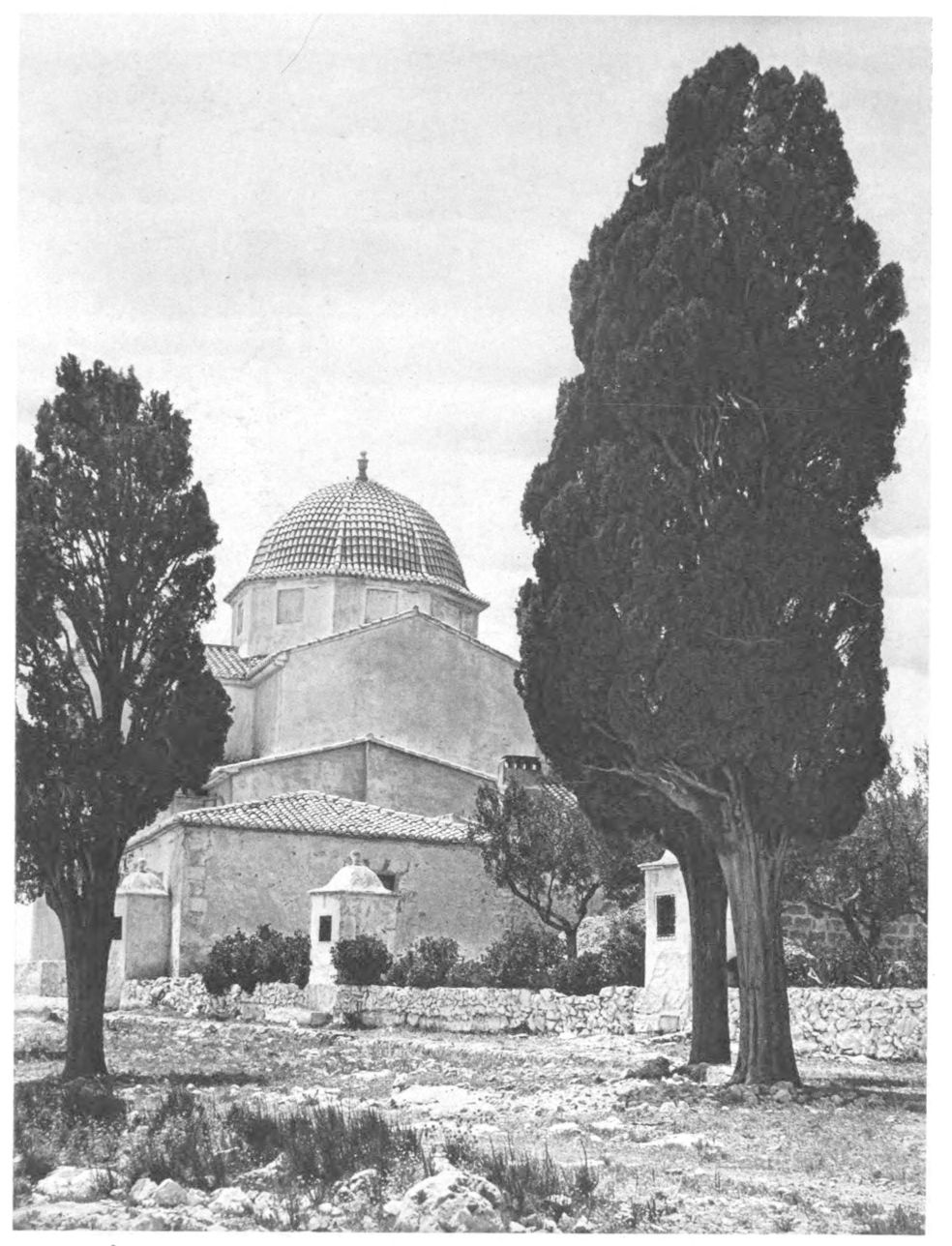

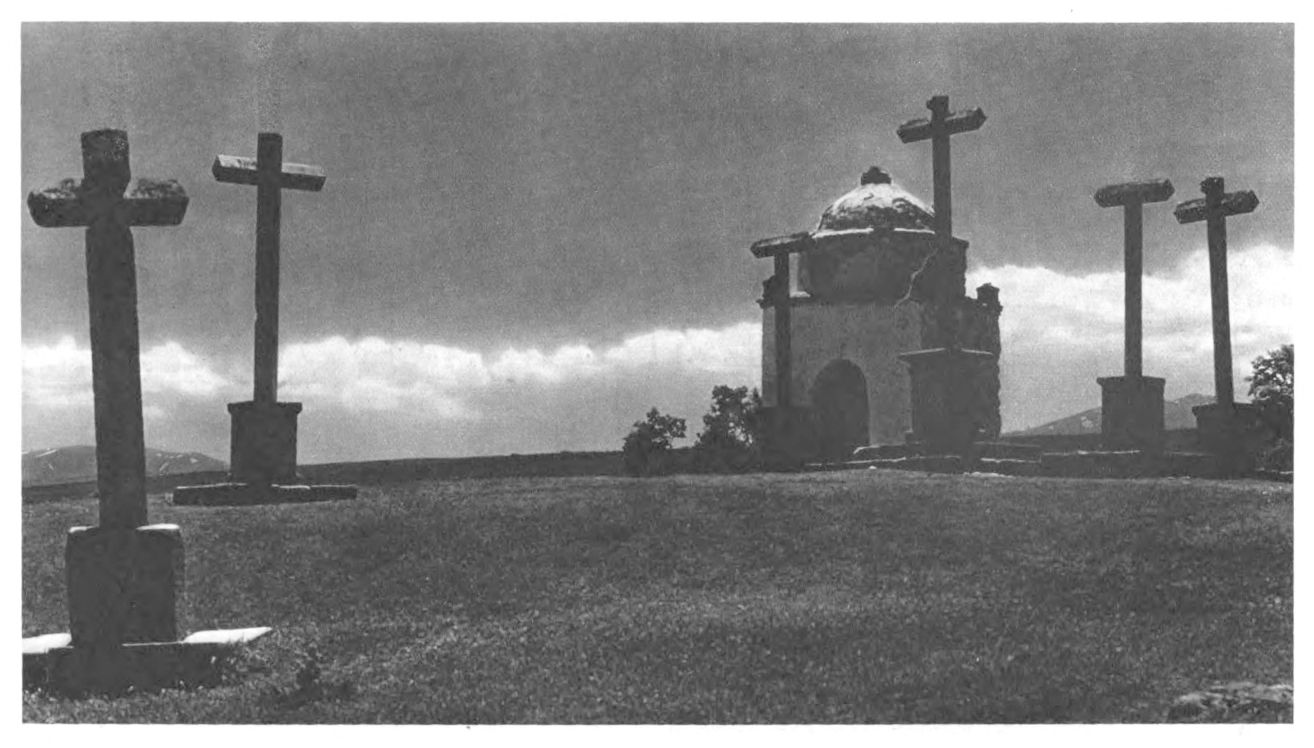

Javea (Denia)

Church of Calvary

Iglesia del calvario

Kalvarienbergkirchlein

L’église du calvaire

La chiesetta del Calvario

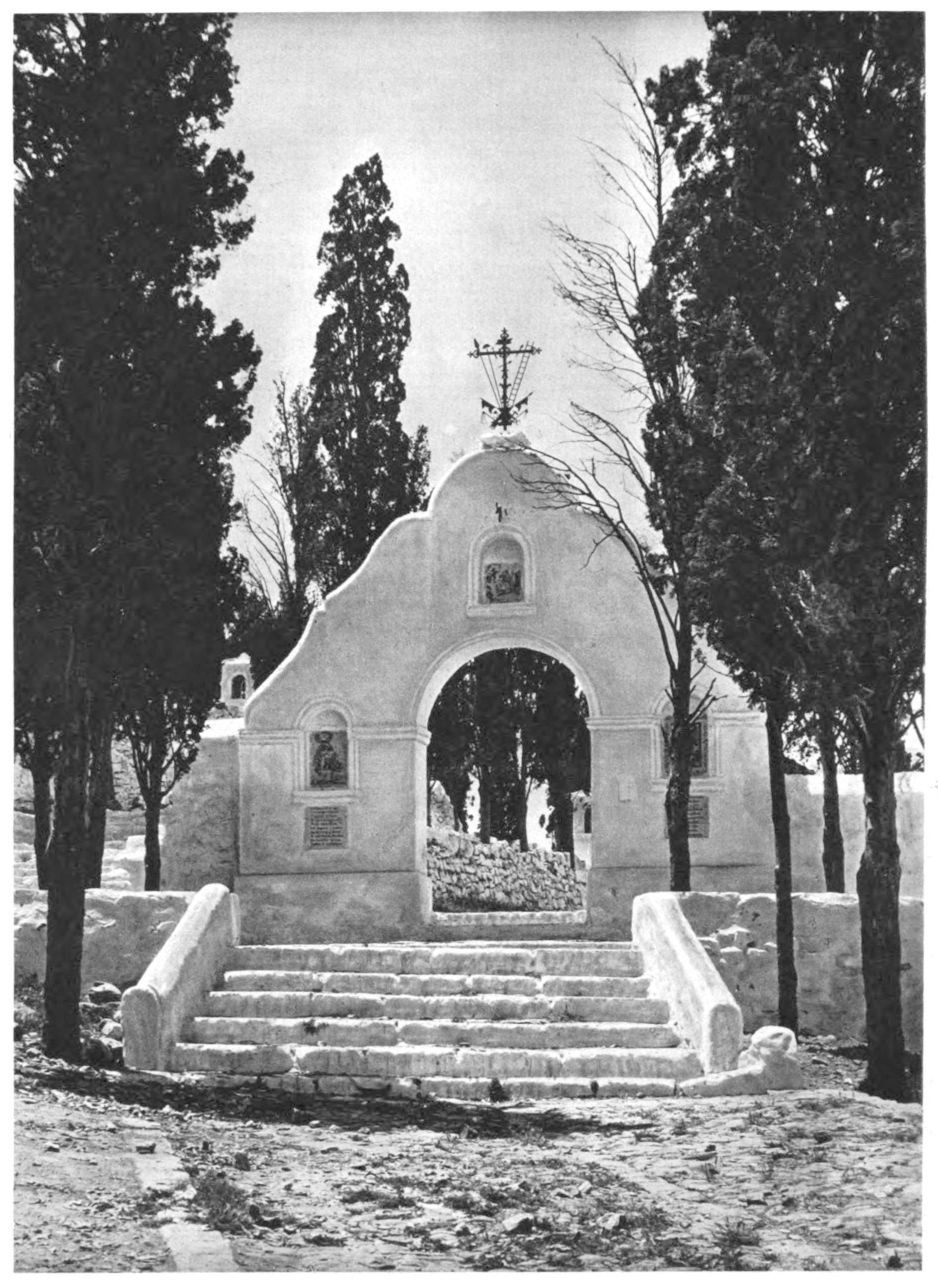

Gateway to the Mount of Calvary, Sagunt

Puerta del calvario de Sagunto

Tor zum Kalvarienberg bei Sagunt

Environ de Sagoute: Accès et entrée du Calvaire

La porta del Calvario presso Sagunto

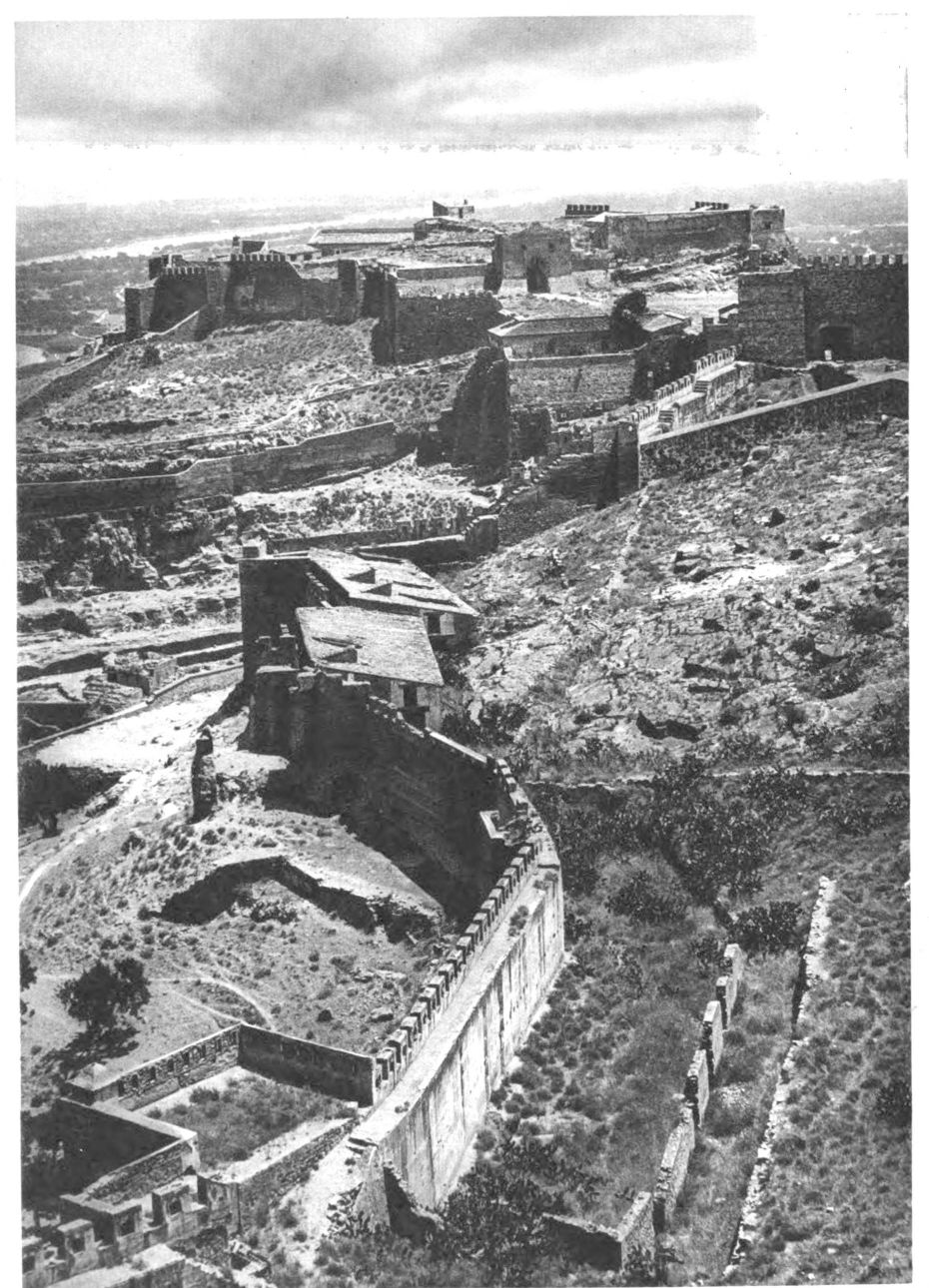

Sagunto, Roman Castle

Sagunto, Castillo romano

Sagunt, Römische Burg

La citadelle romaine

Castello romano

Jativa

View of the Castle

Vista del Castillo

Blick zur Burg

Vue sur le Château-fort

Veduta del Castello

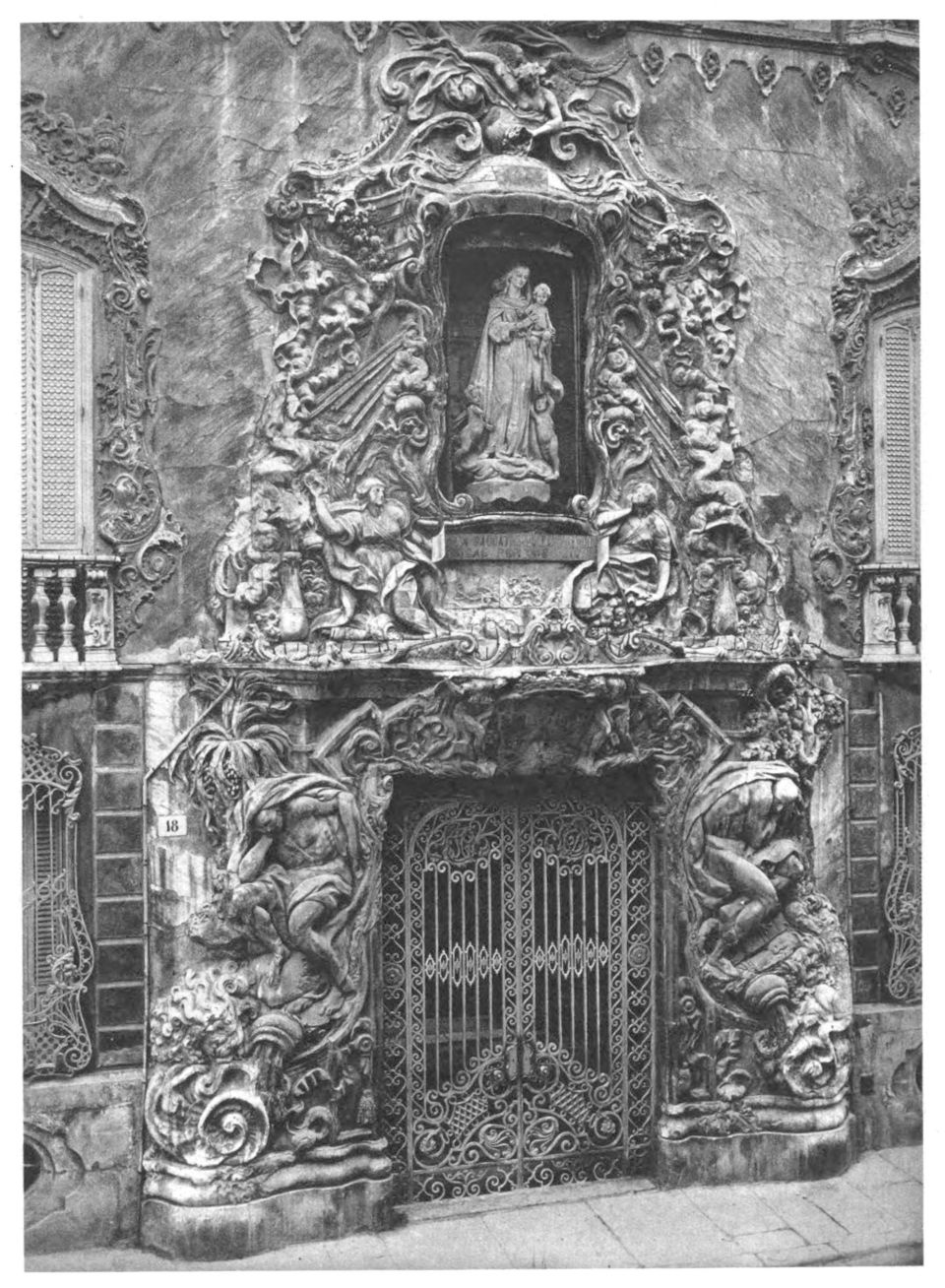

Valencia

Gateway of the Marquis de Dos Aguas Palace

Portada del Palacio del Marqués de Dos Aguas

Portal des Palastes des Marqés de Dos Aguas

Portail du palais du marquis de Dos Aguas

Portale del Palazzo del Marchese de Dos Aguas

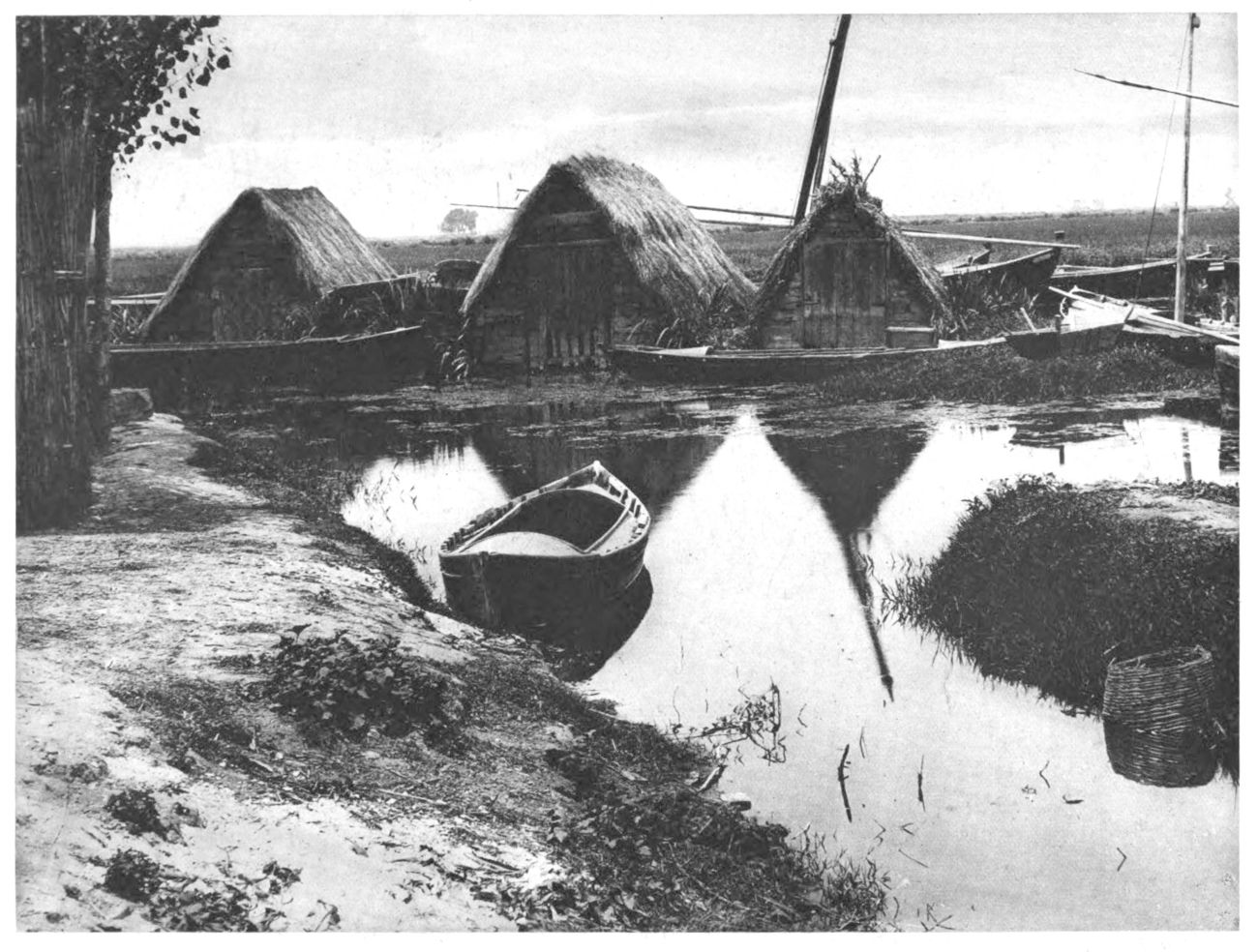

Huts on the banks of the Albufera near Valencia

Barracas de La Albufera cerca de Valencia

Albuferahütten bei Valencia

Environs de Valence: Cabanes de l’Albufera

Capanne di Albufera presso Valenza

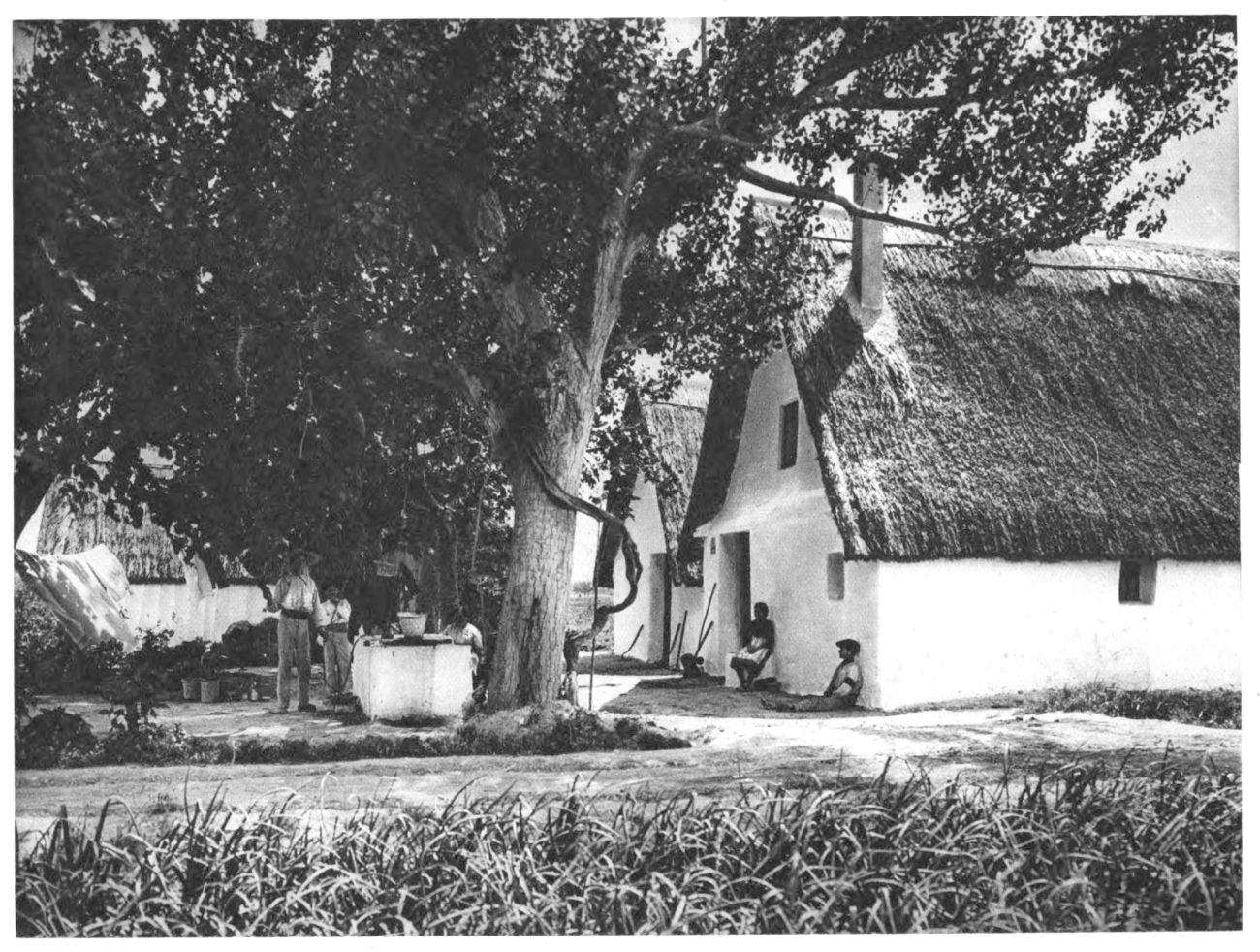

Huerta Huts near Valencia

Barracas de la Huerta de Valencia

Huertahütten bei Valencia

Maisons de paysans de la Huerta

Capanne di Huerta presso Valenza

Guadalest Castle (Prov. of Alicante)

Castillo Guadalest (Prov. de Alicante)

Castillo Guadalest (Prov. Alicante)

Château de Guadalest (Province d’Alicante)

Castello di Guadalest (Provincia di Alicante)

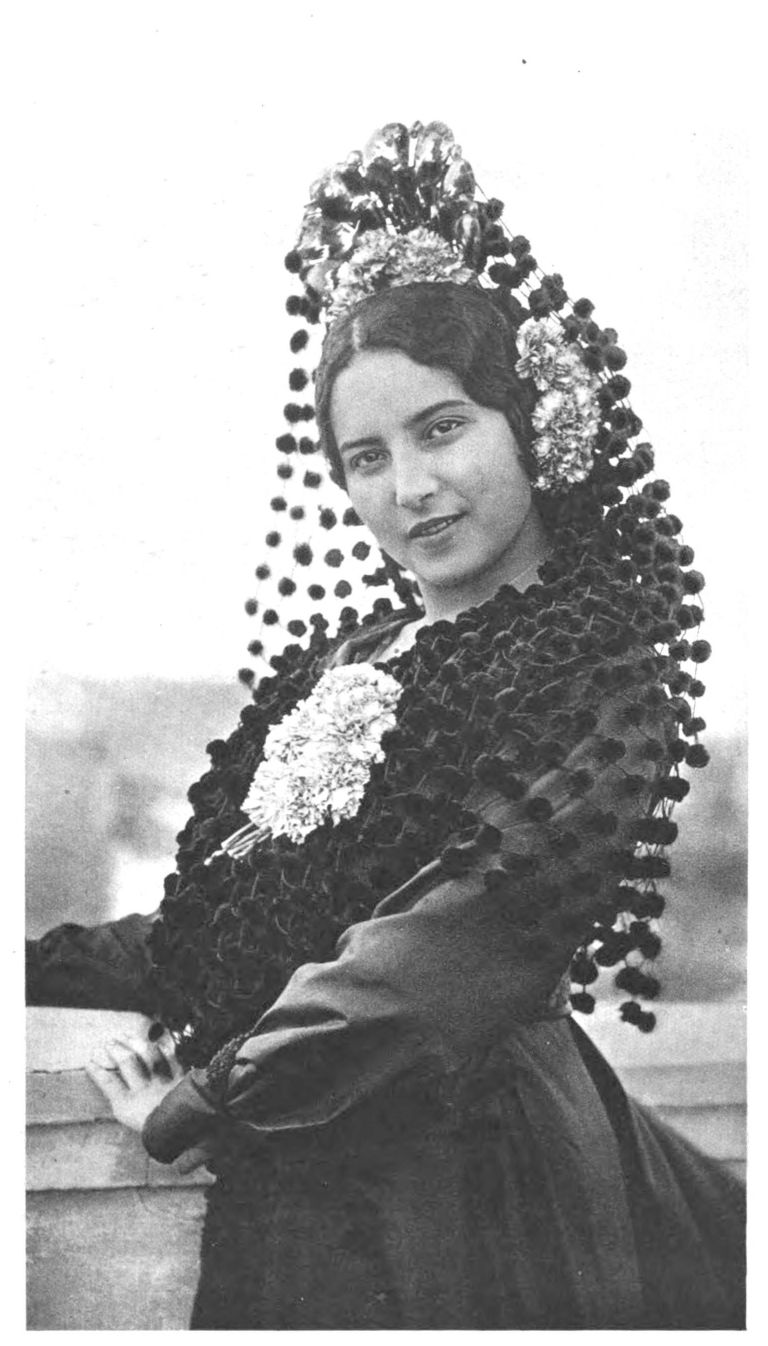

The Jerez mantilla

Con la mantilla jerezana

Im Schmuck der Mantilla von Jerez

Sous la mantille (Femme de Jerez)

Mantiglia jerezana

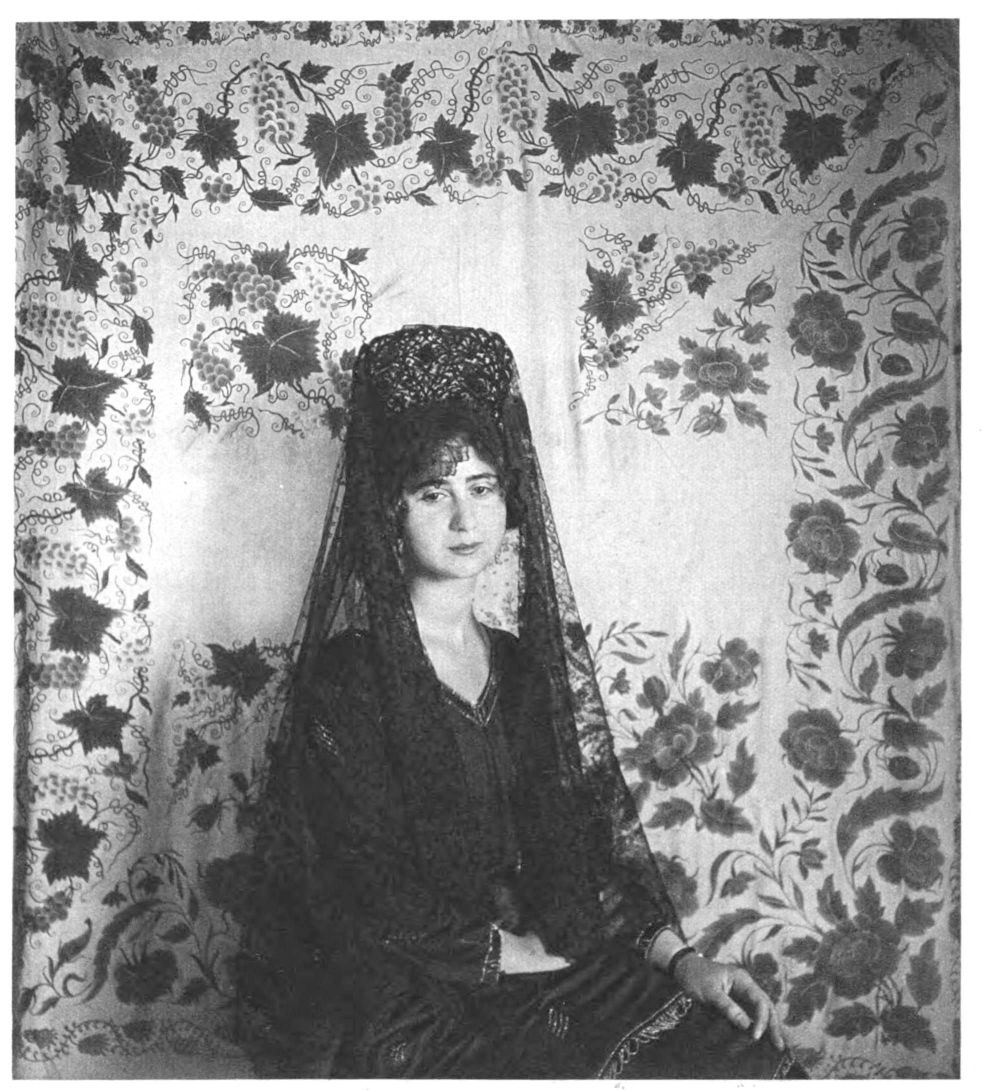

With the mantilla

Con la mantilla

Im Schmuck der Spitzenmantilla (als Hintergrund die Manton)

En mantille de dentelle

Mantiglia a merletti

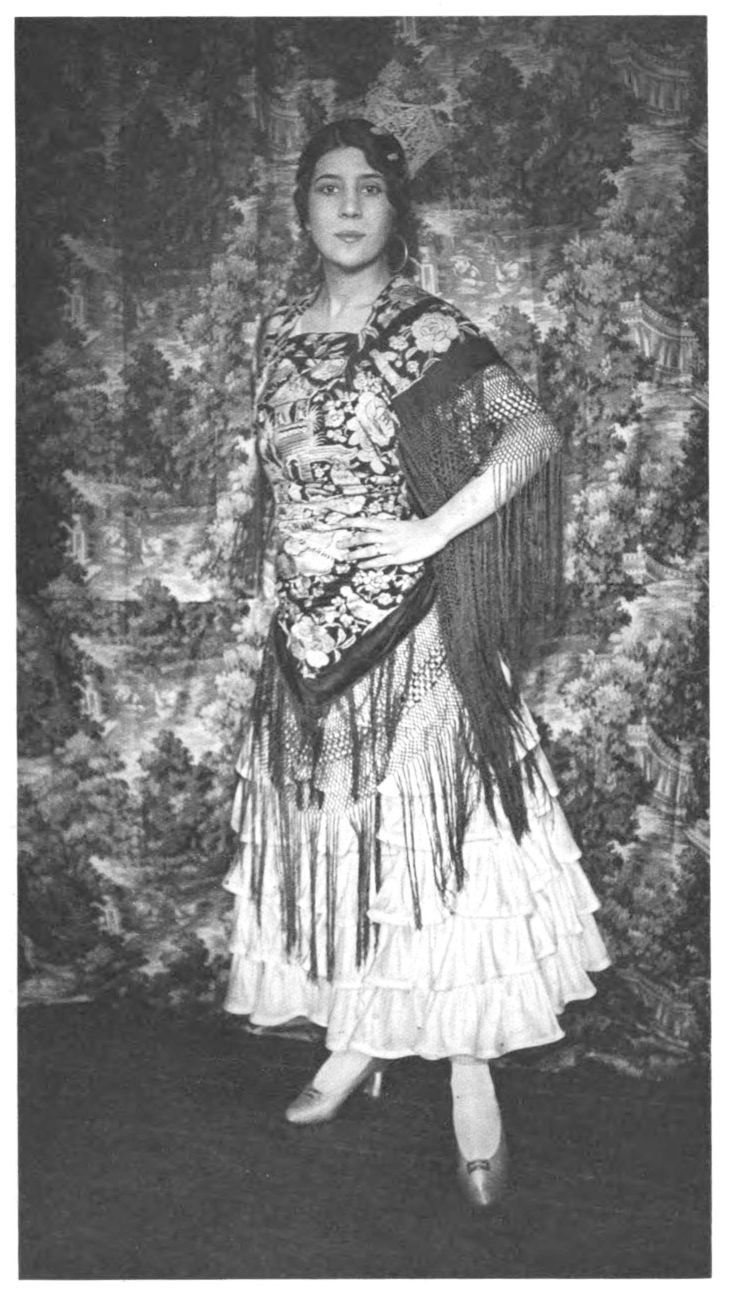

La Argentinita, Spain’s most celebrated dancer wearing the Manton (shawl)

La Argentinita

Argentinita, Spaniens berühmteste Tänzerin im Schmuck der Manton (Schultertuch)

La Argentinita, la plus célèbre danseuse de l’Espagne avec la mante espagnole sur les épaules

Argentinita, la più celebre ballerina della Spagna, con sulle spalle il caratteristico Manton spagnole

Entrance of the bull-fighters into the Madrid Arena

El despejo en la plaza de toros de Madrid

Einzug der Stierkämfer in die Arena von Madrid

Entrée du cortège dans l’arène avant la corrida (Madrid)

Ingresso del toreadori nell’Arena di Madrid

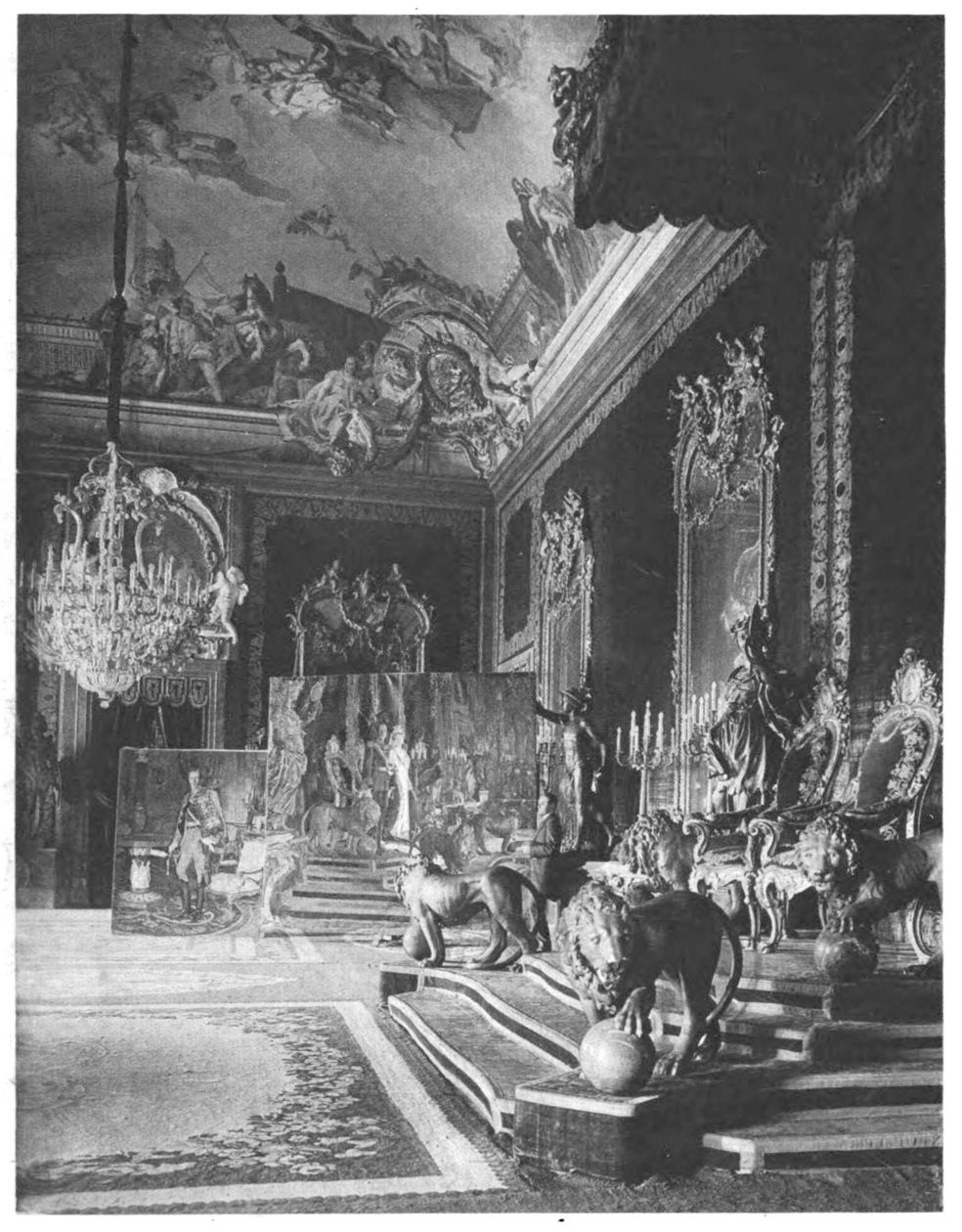

Madrid

The Throne-Room in the Royal Castle

Sala del Trono en el Palacio Real

Thronsaal des Königlichen Schlosses

La salle du trône au Château royal

La Sala del Trono nel Palazzo Reale

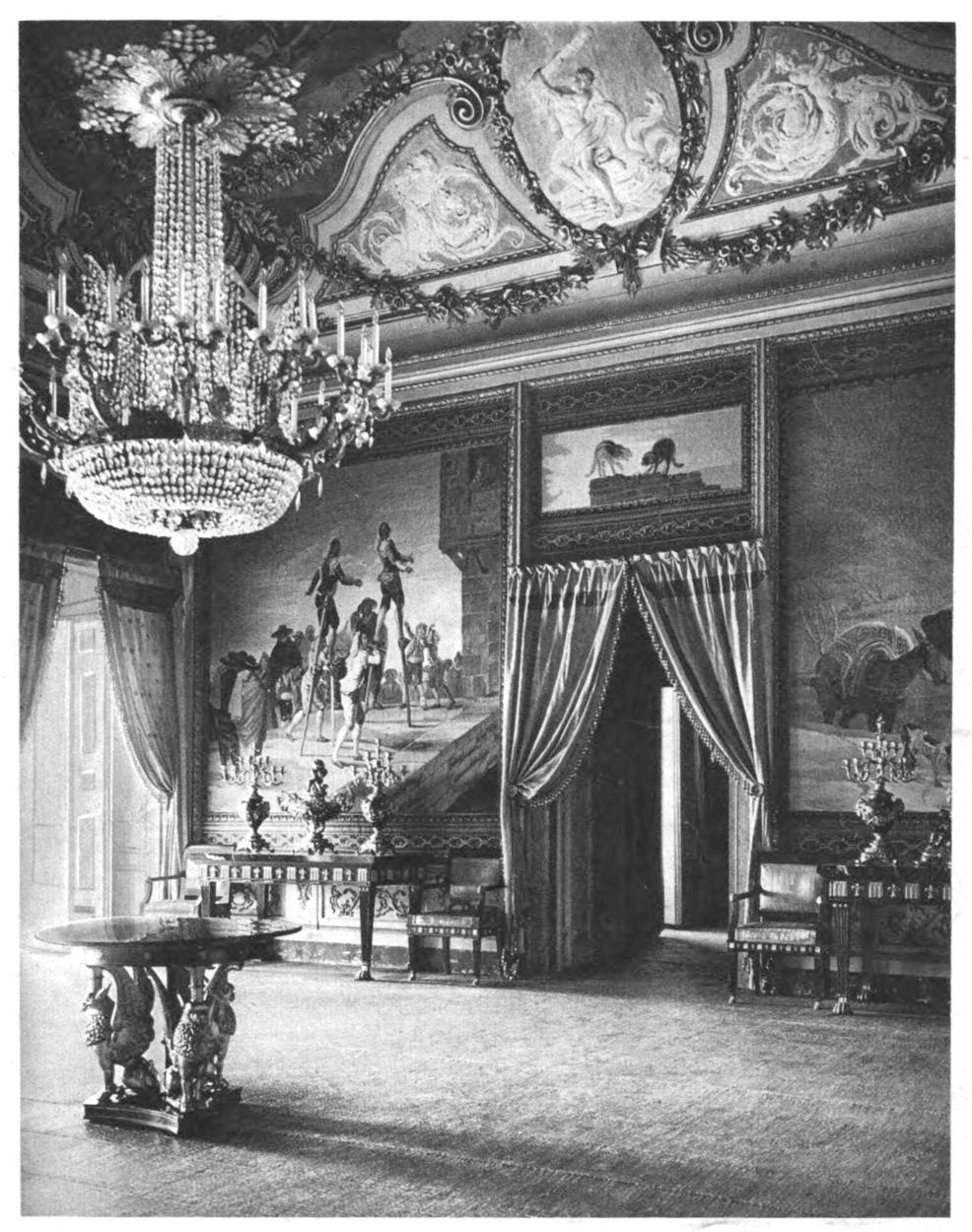

In the Royal Castle El Pardo near Madrid

En el Pardo

Im Königlichen Schloß El Pardo bei Madrid

Une salle du château royal d’el Pardo près de Madrid

Nel Palazzo Reale El Pardo, presso Madrid

Escorial

Court of the Evangelists

Patio de los Evangelistas

Evangelistenhof

Cour des evangelistes

La corte degli evangelisti

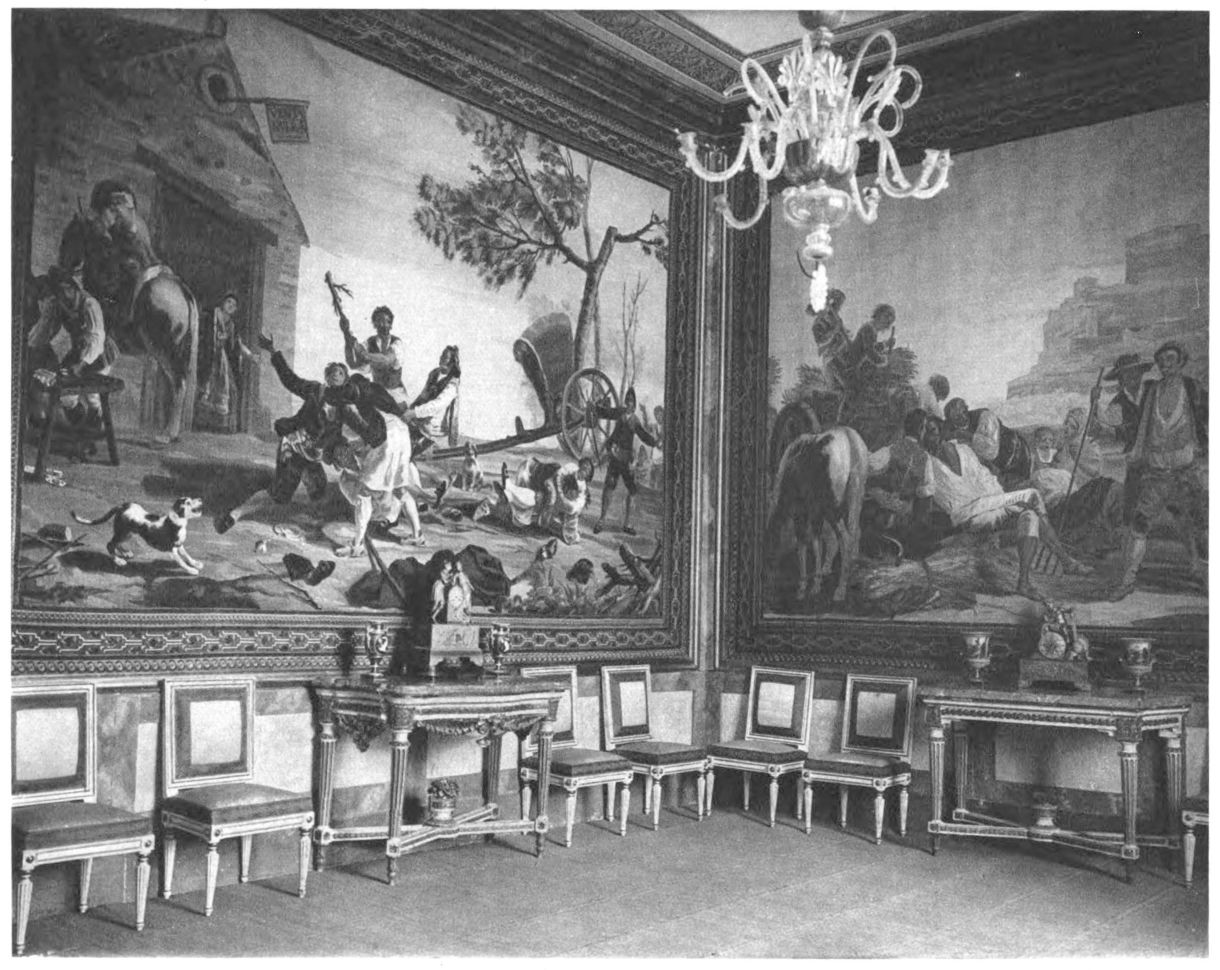

In the Escorial Palace: on the walls tapestries after Goya’s paintings

Palacio del Escorial

Im Palast des Escorial: an den Wänden Gobelins nach Goyaschen Gemälden

Le Château de l’Escurial. Tapisseries des Gobelins d’après des peintures de Goya

Nel Palazzo dell’Escorial. Alle pareti tappeti Gobelins con riproduzione delle pitture di Goya

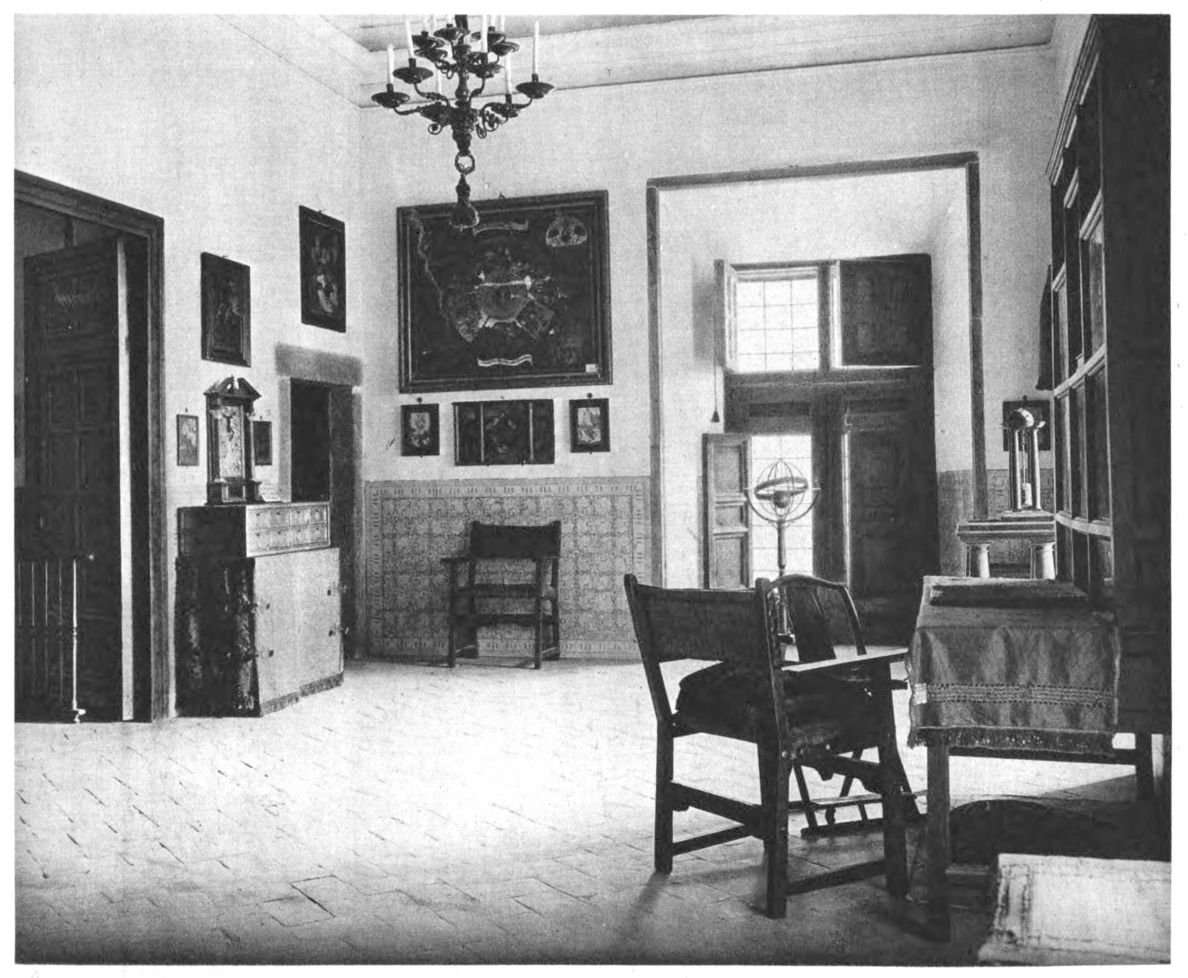

Escorial

Philip II. Study

Despacho de Felipe II

Arbeitszimmer Philips II

Cabinet de travail de Philippe II

Gabinetto da lavoro di Filippo II

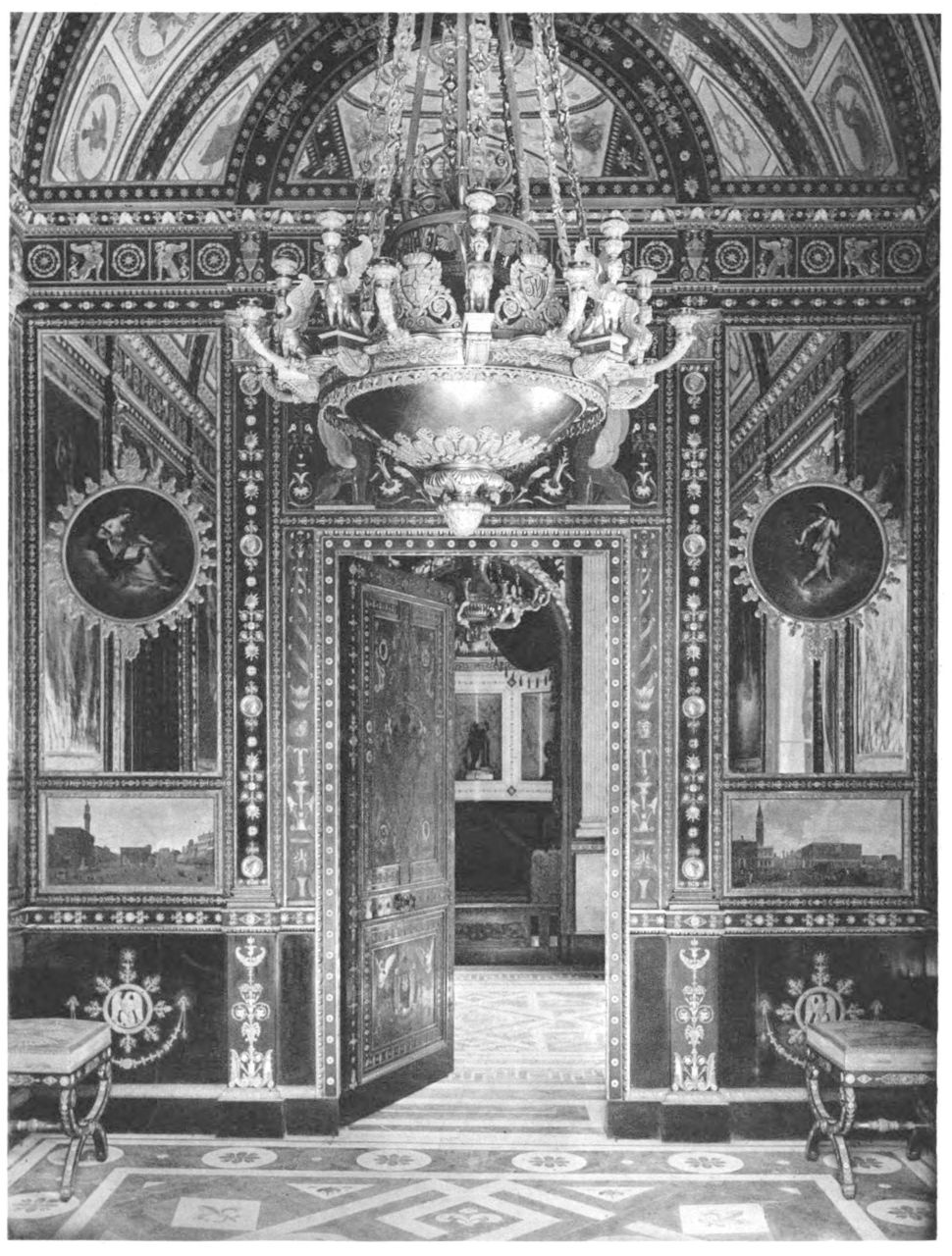

Aranjuez—Casa de Labrador

The Platinum Hall

Sala de Platino

Platinsaal

Maison de Labrador. La salle de platine

Casa de Labrador. Sala del platino

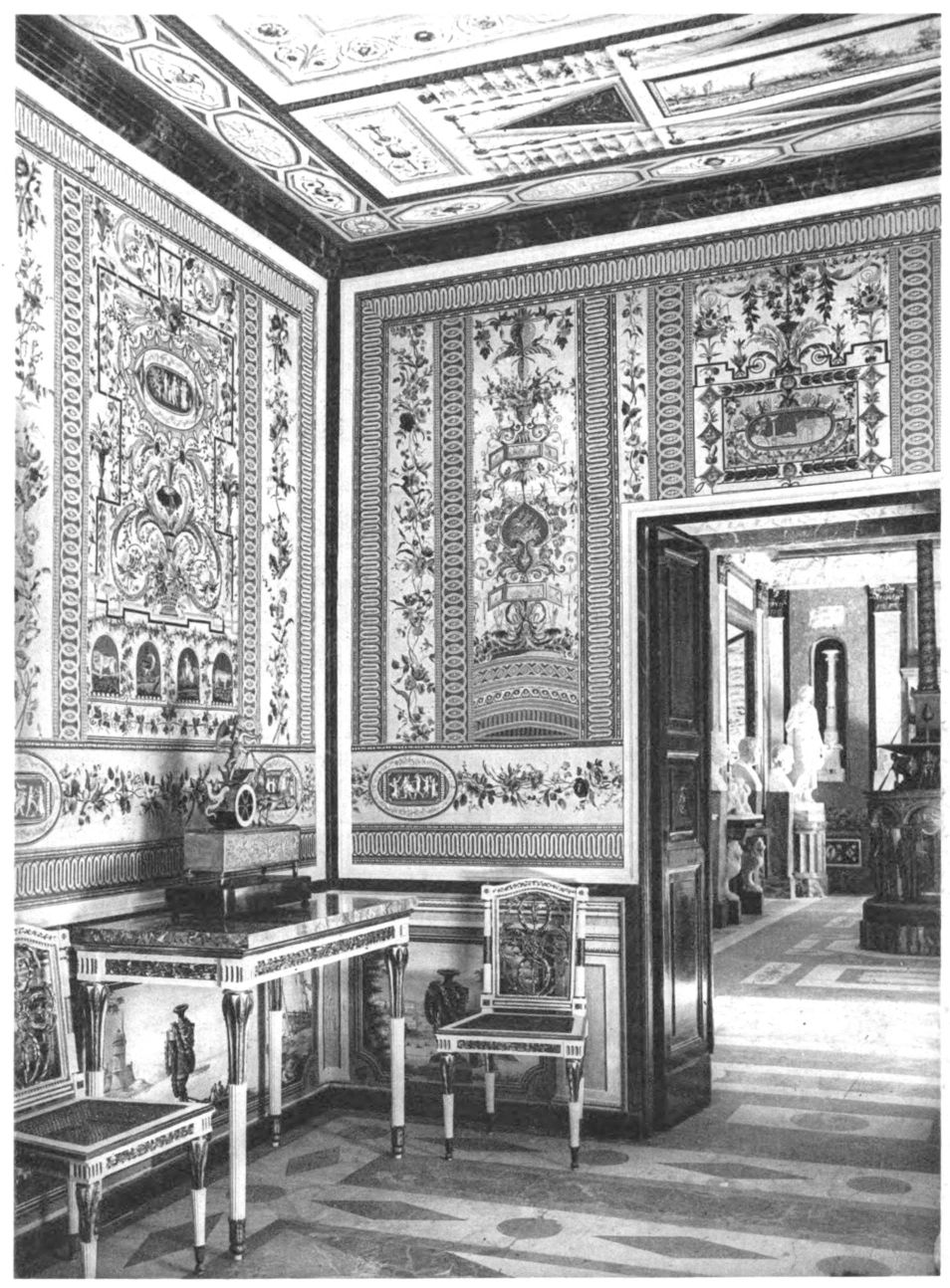

Aranjuez

In the Casa de Labrador

En la Casa de Labrador

In der Casa de Labrador

Intérieur de la maison de Labrador

Nella Casa de Labrador

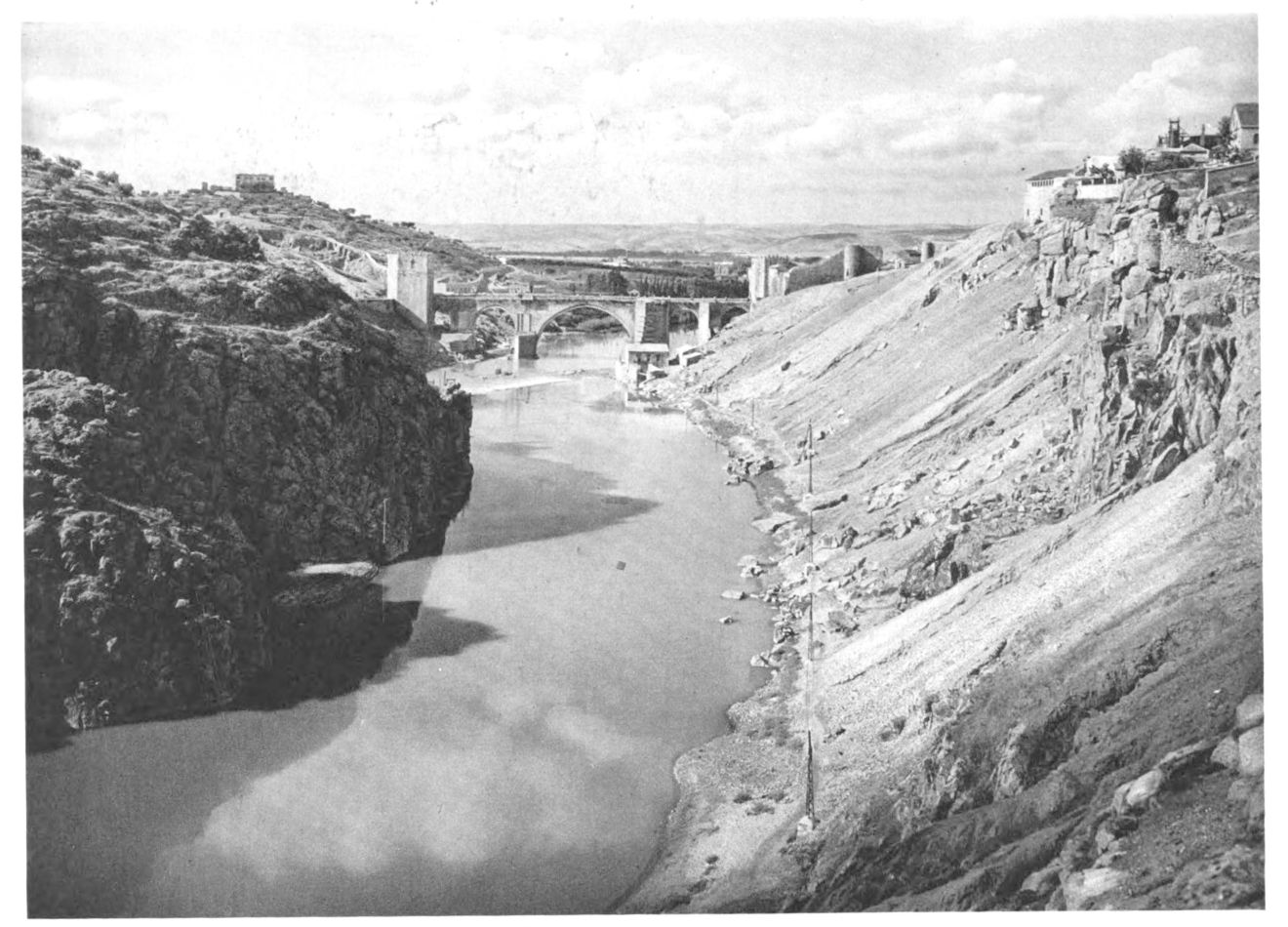

Toledo

Tajo Valley and St. Martin Bridge

Valle del Tajo y puente de S. Martin

Tajotal und San Martinbrücke

La vallée du Tage et le pont St. Martin

La valle del Tajo dal ponte di S. Martino

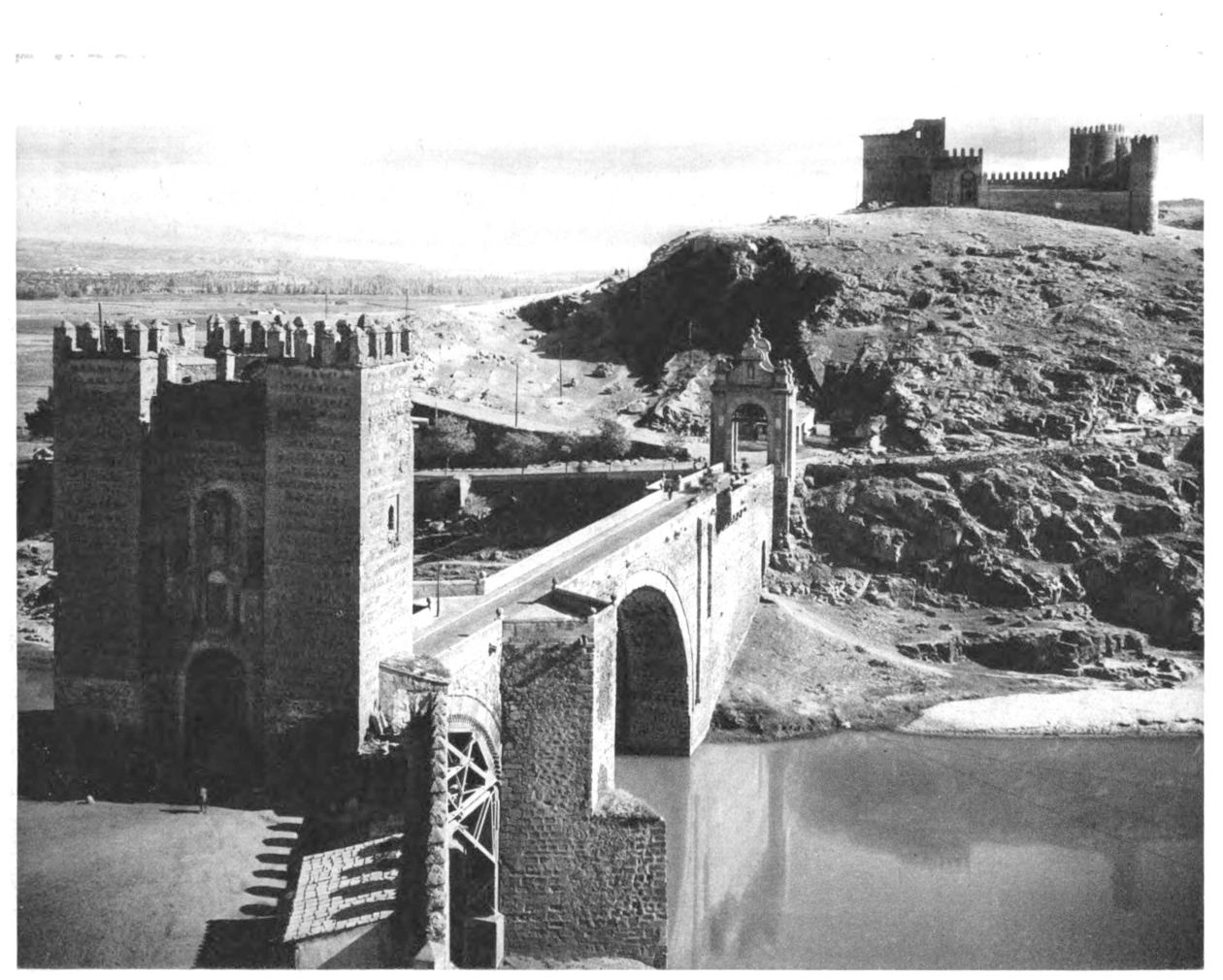

Toledo

Alcantara Bridge and St. Servando Castle

Puente Alcantara y Castillo S. Servando

Alcantarabrücke und Castillo S. Servando

Pont d’Alcantara, et château de St. Servando

Il Ponte d’Alcantara e il Castello di S. Servando

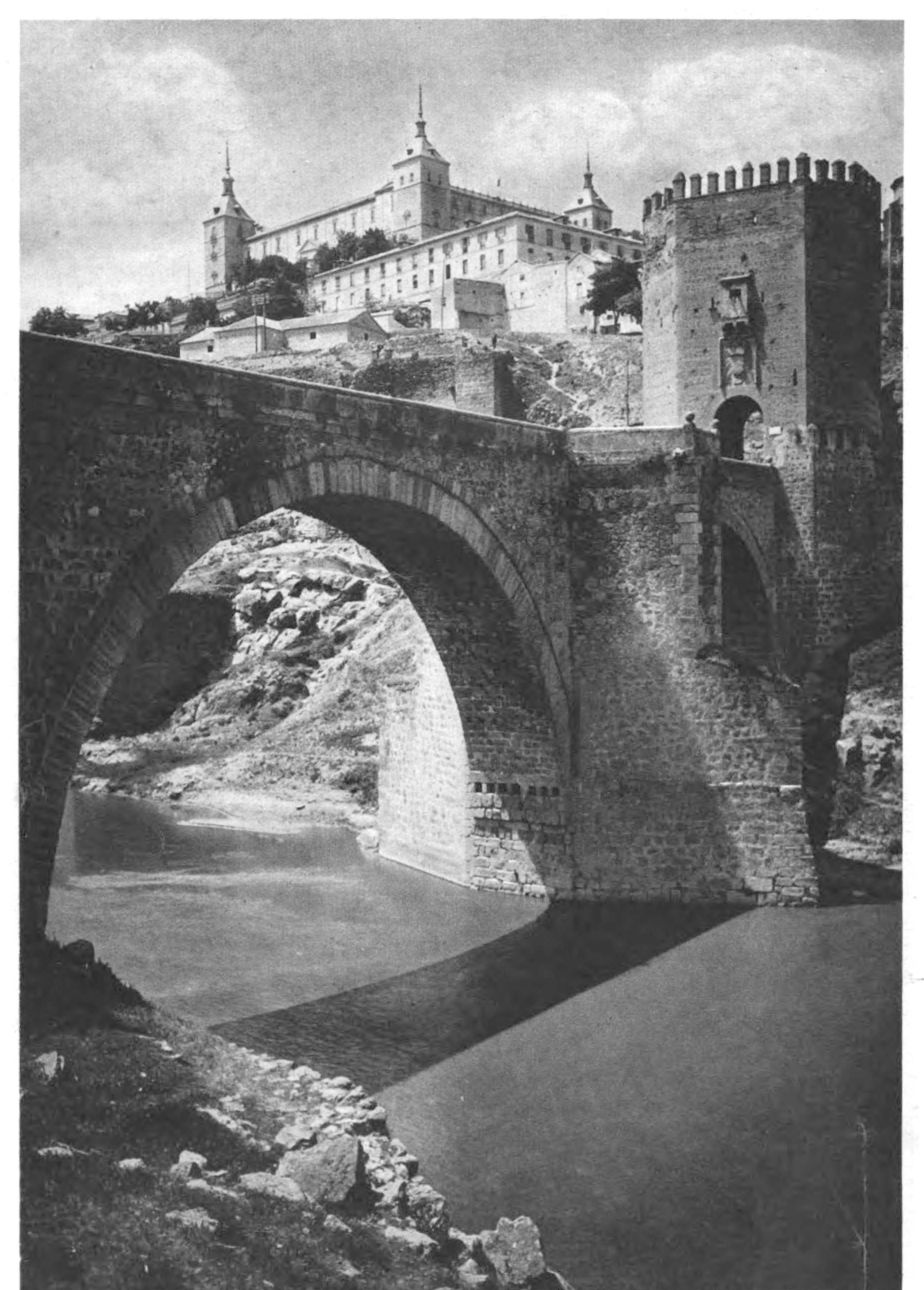

Toledo

Alcantara Bridge with the Alcazar in the background

Puente Alcantara en el fondo el Alcazar

Alcantarabrücke, überragt vom Alcazar

Le Pont d’Alcantara, dominé par l’Alcazar

Il Ponte Alcantara e in alto, in fondo, Alcazar

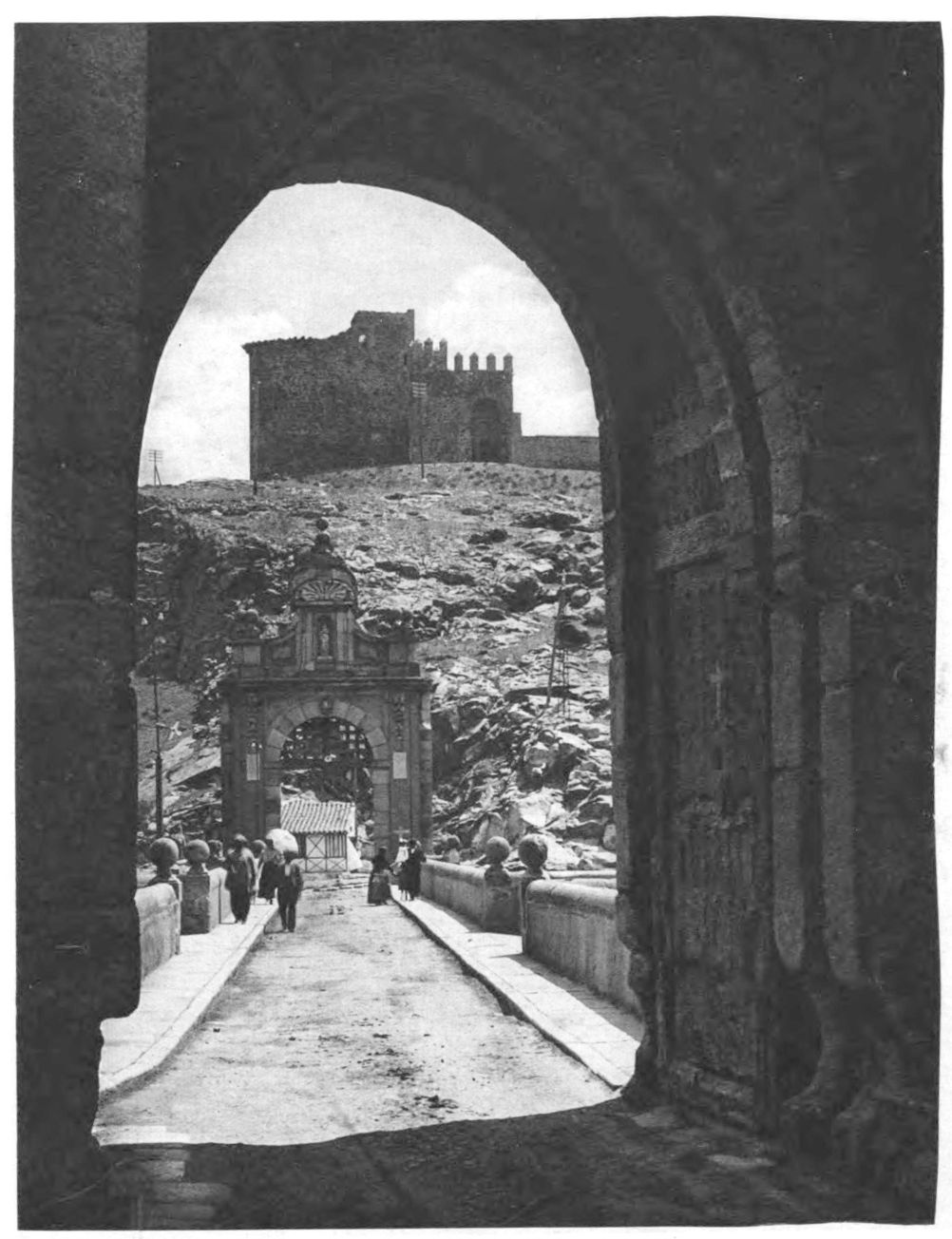

Toledo

View through the gateway of the Alcantara Bridge

Vista tomada desde la puerta del puente Alcantara

Blick durch das Brückentor der Alcantarabrücke

Vue de la porte d’entrée du pont d’Alcantara

Veduta del Ponte d’Alcantare dal Portone del Ponte stesso

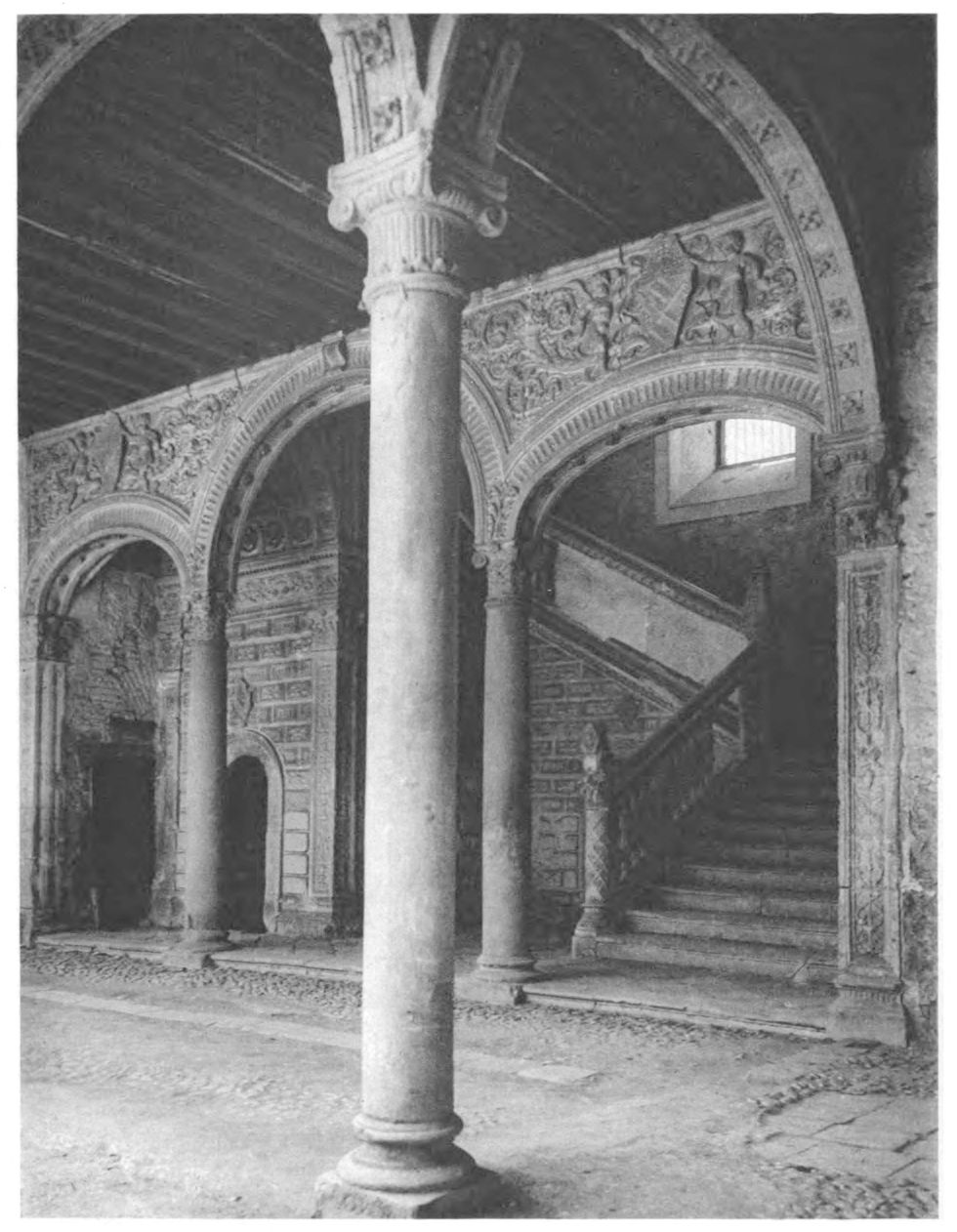

Toledo

Staircase in St. Cruz Hospital

Escalera del hospital de Sta. Cruz

Treppe des Hospitals Sta. Cruz

Escalier de l’hôpital Santa-Cruz

Scala dell’ospedale di Santa Cruz

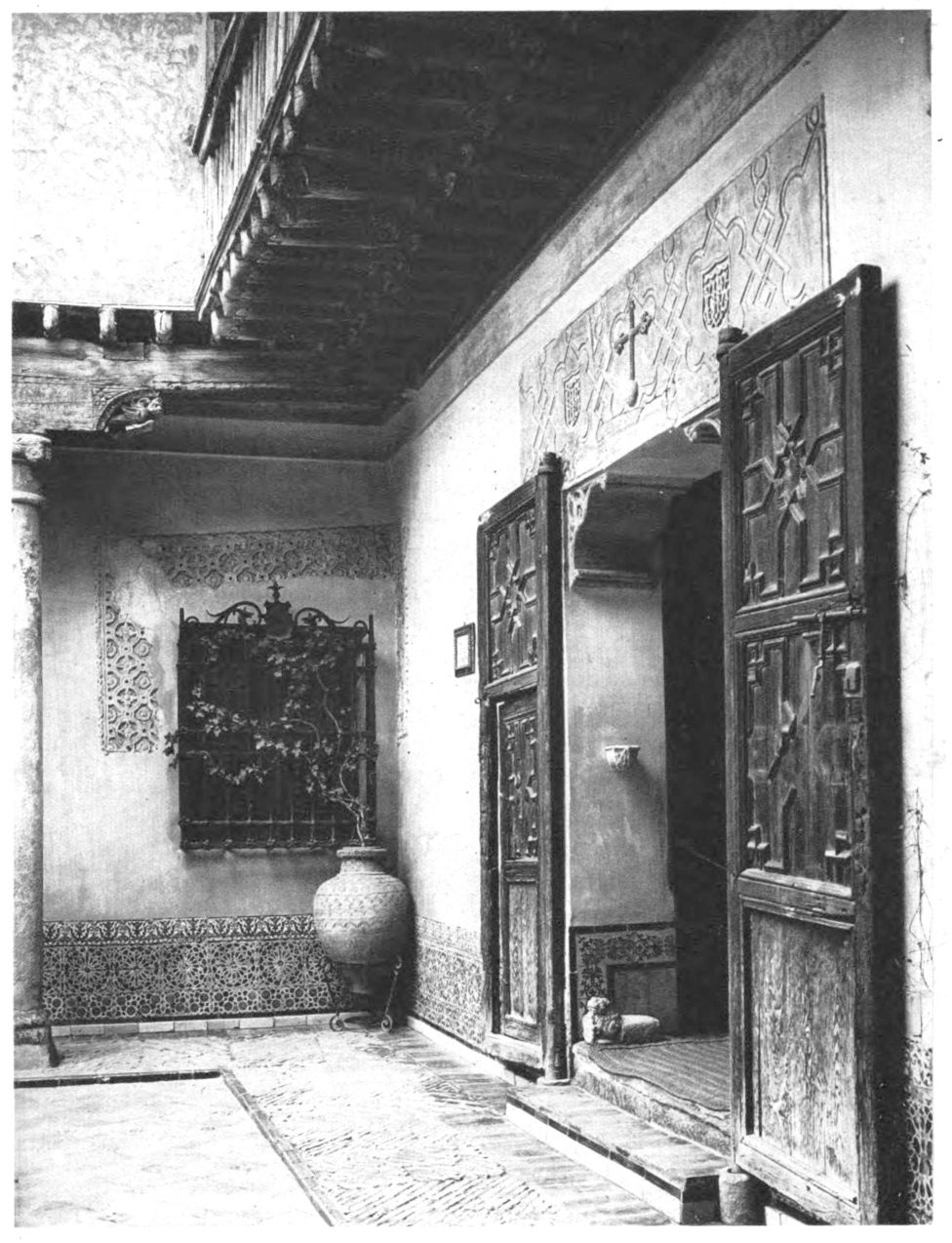

Toledo

In the court of the Casa Greco

En el patio de la Casa del Greco

Im Hof des Grecohauses

Cour de la maison du Grec

Cortile della Casa del Greco

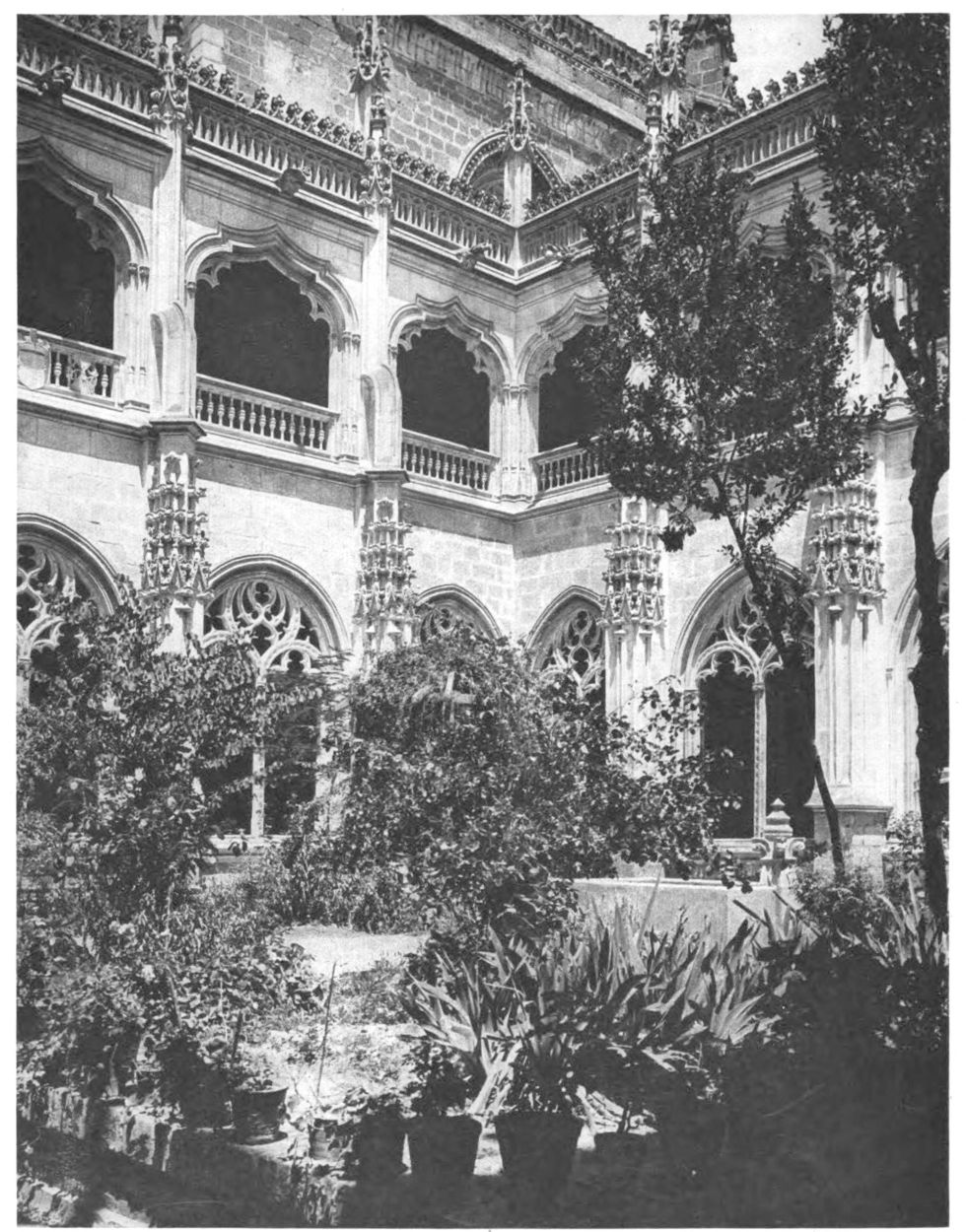

Toledo

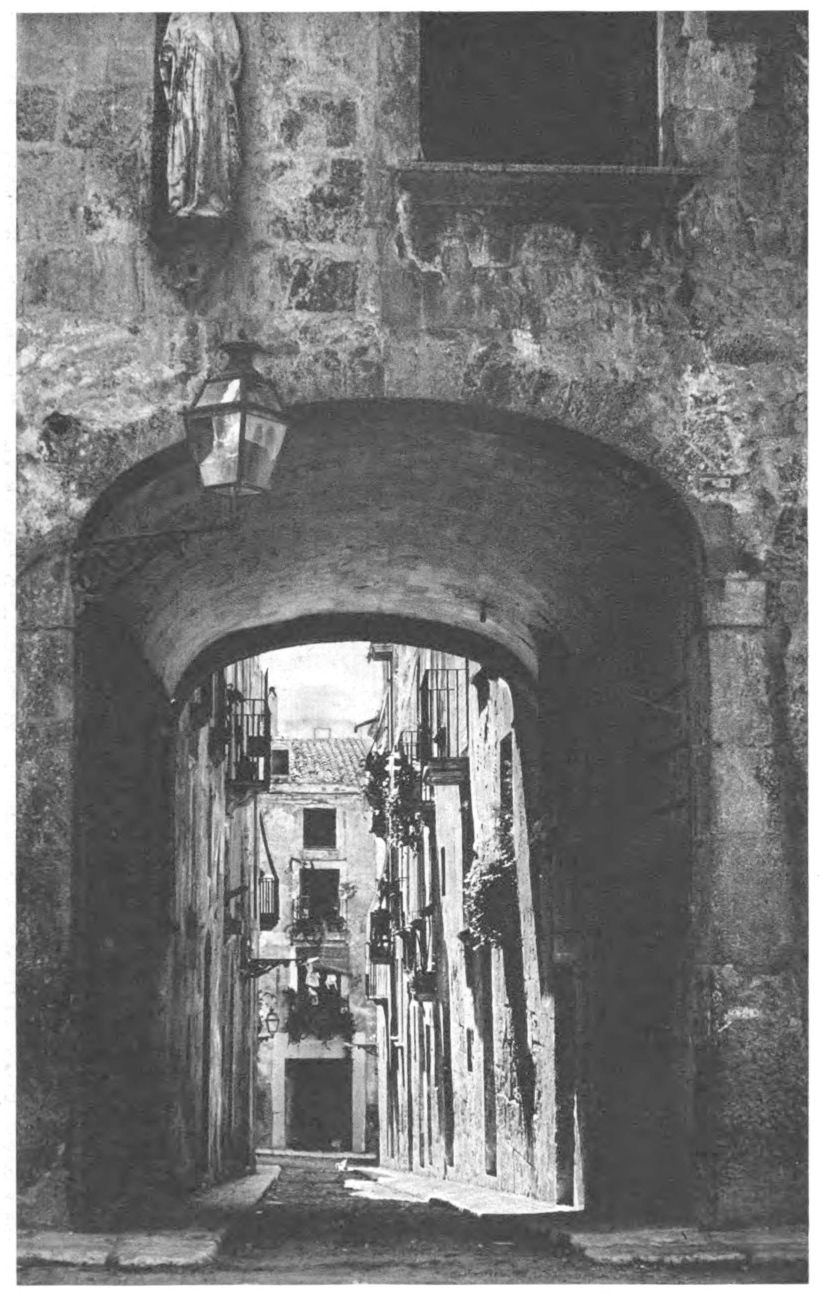

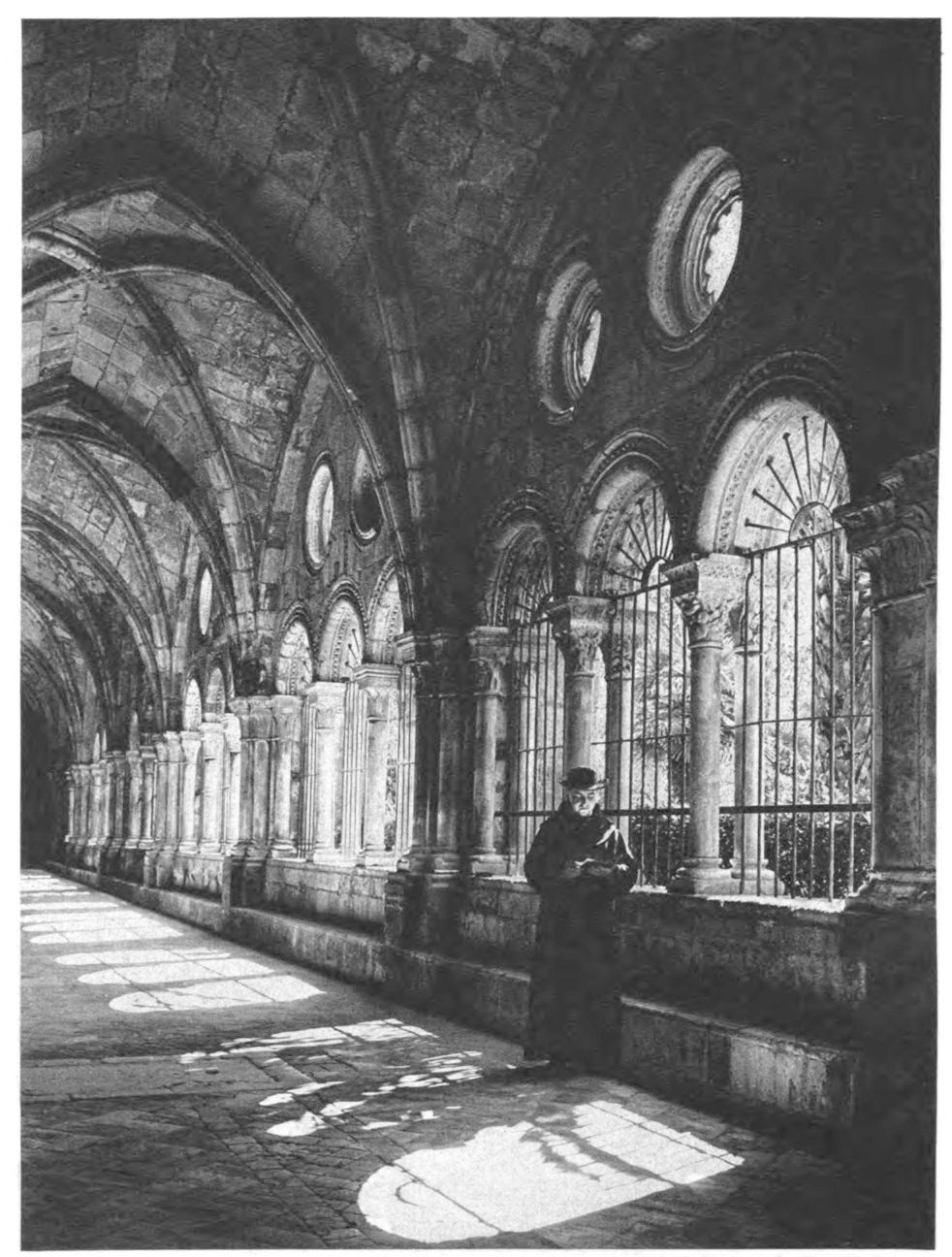

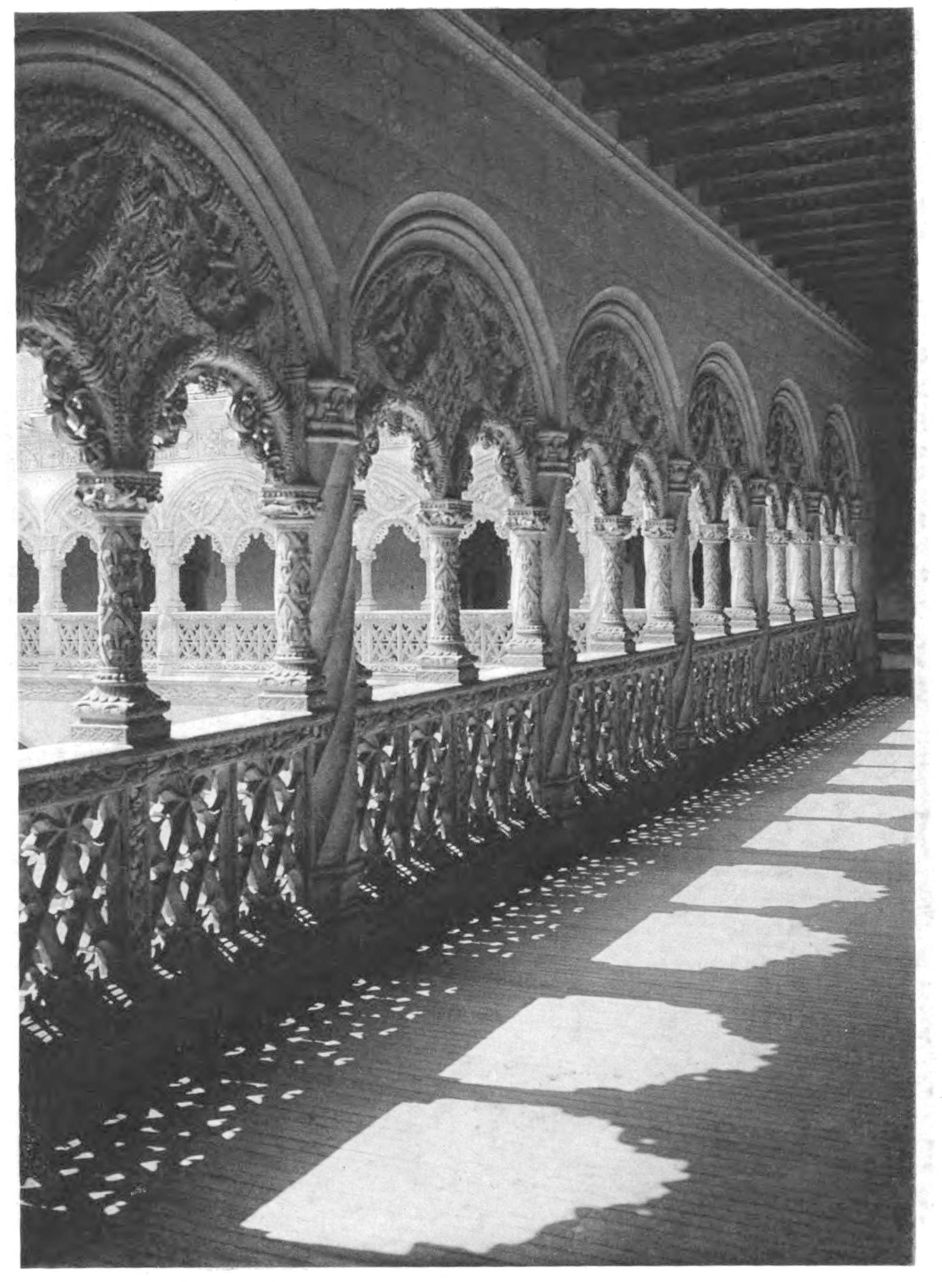

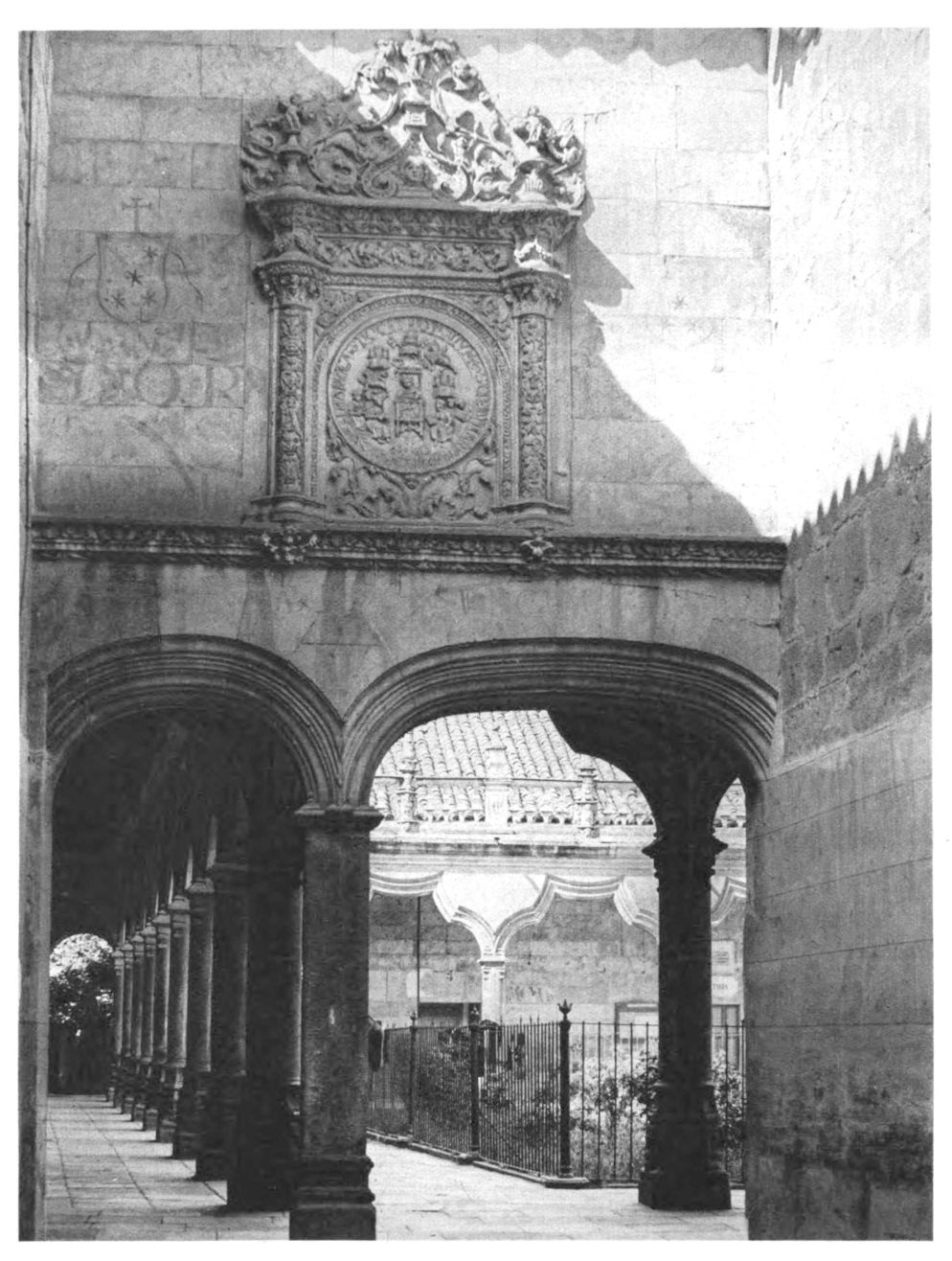

Cloister of St. Juan de los reyes

Claustro de S. Juan de los reyes

S. Juan de los reyes, Kreuzgang

Cloître de St. Jean de los reyes

Loggiato del Chiostro di S. Juan de los reyes

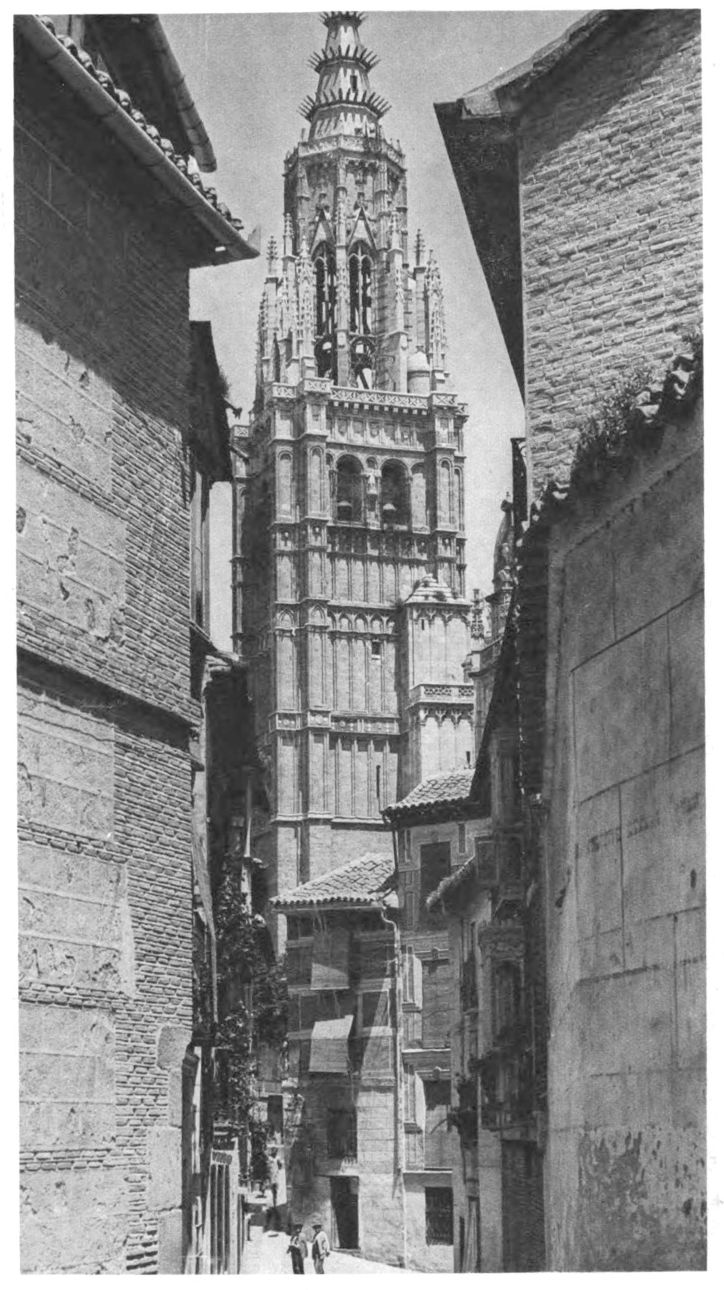

Toledo

Cathedral Spire

Torre de la Catedral

Turm der Kathedrale

Tour de la Cathédrale

Il campanile della Cattedrale

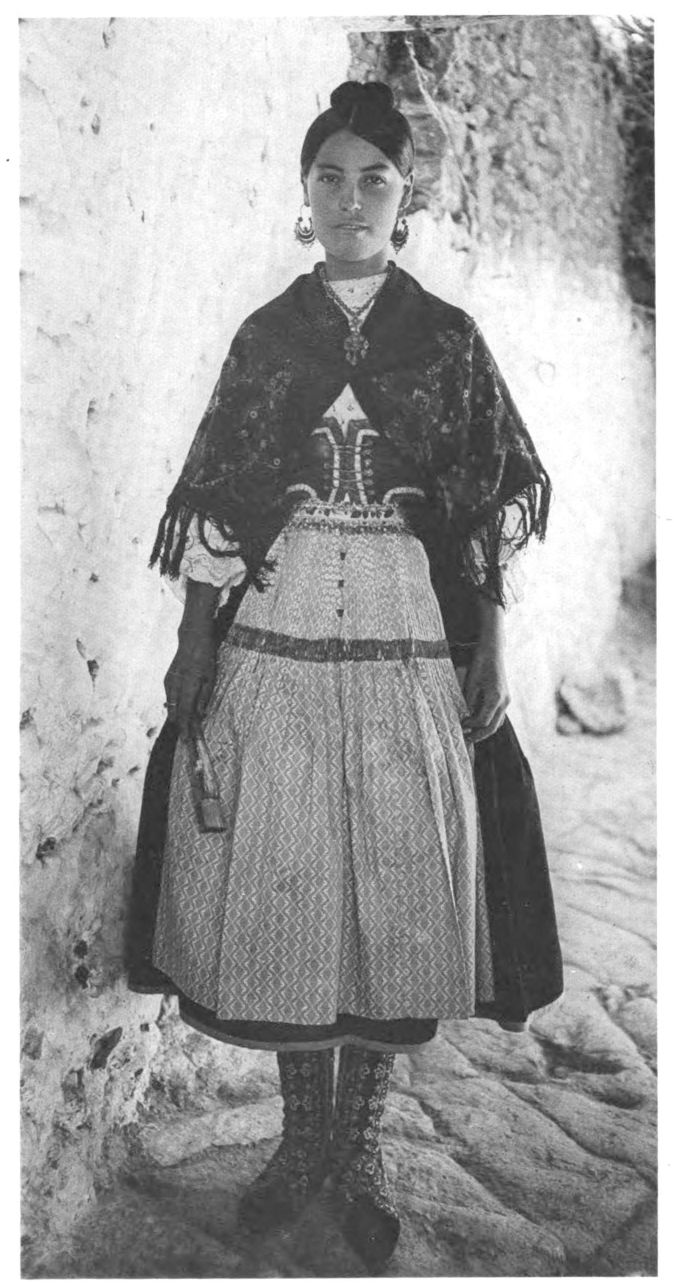

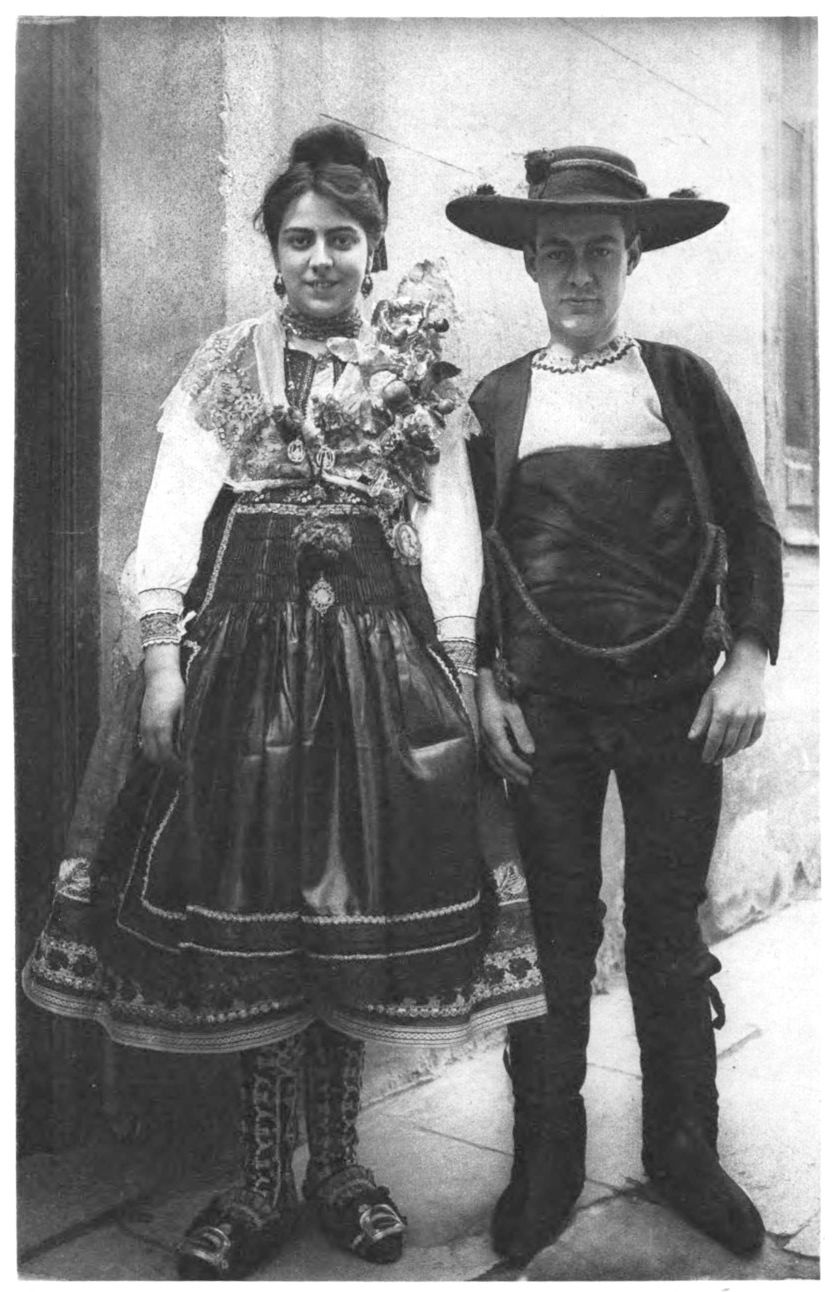

Lagartera Costume (Prov. of Toledo)

Traje de Lagartera (Prov. de Toledo)

Tracht von Lagartera (Prov. Toledo)

Jeune femme de Lagartera (Province de Tolède)

Costume di Lagartera (Prov. di Toledo)

Lagartera Wedding Dress (Prov. of Toledo)

Traje de boda de Lagartera (Prov. de Toledo)

Hochzeitstracht von Lagartera (Prov. Toledo)

Une noce à Lagartera (Province de Tolède) Les maries

Veste nuziale di Lagartera (Prov. di Toledo)

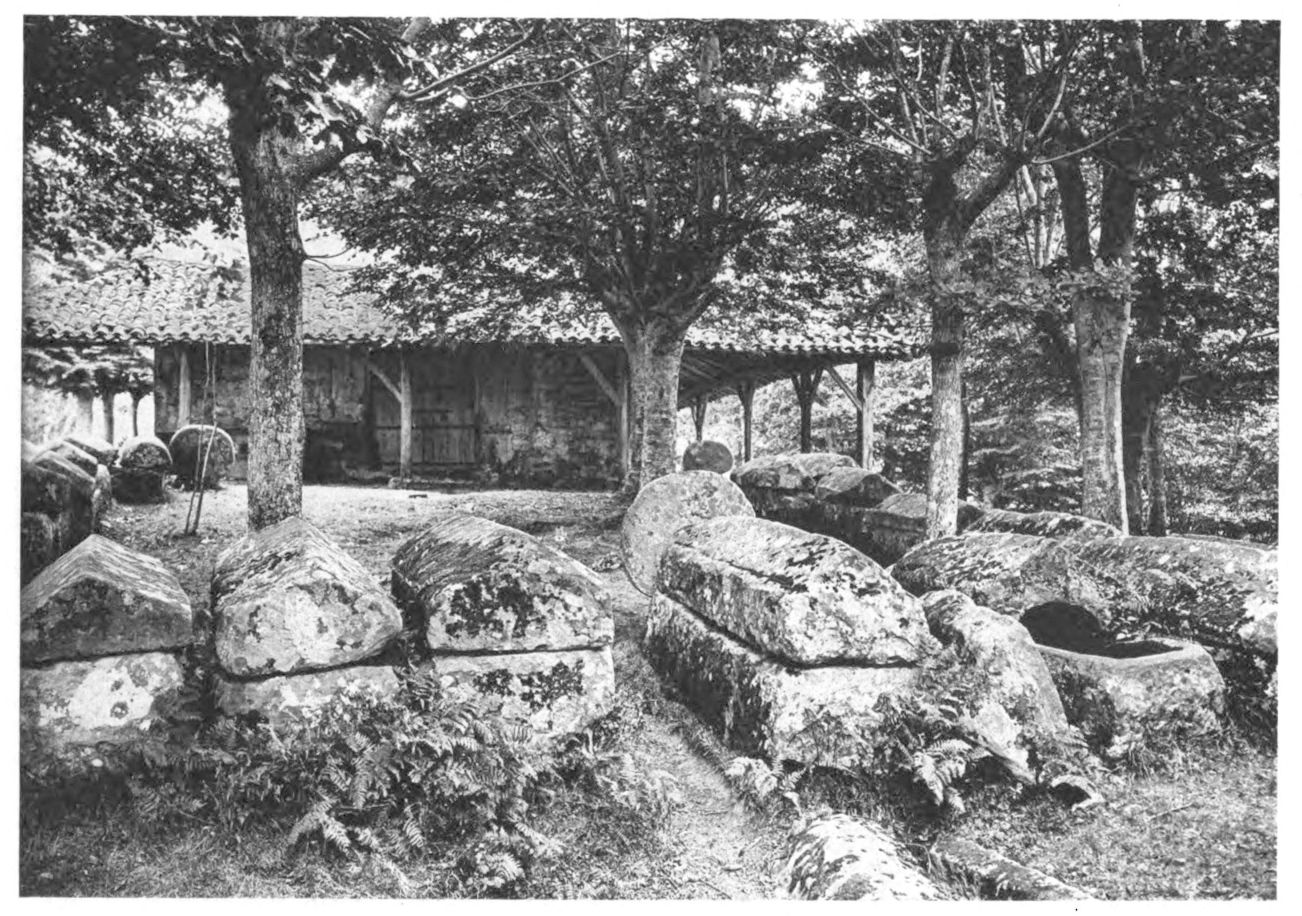

Ruins of the Cloister in Yuste Convent

Ruinas del Claustro de Yuste

Ruinen des Kreuzganges im Kloster Yuste

Ruines du monastère de Yuste

Rovine nel Chiostro di Yuste

In the village-square of Cepeda before the bull-fight

Antes de la novillada en la plaza de la aldea da Cepeda

Vor dem Stierkampf auf dem Dorfplatz von Cepeda

Avant le combat de taureaux sur la place de Cepeda

Prima della Corrida di tori nella piazza del villaggio di Cepeda

Segovia

The Roman Aqueduct

El acueducto romano

Römischer Aquädukt

L’aqueduc romain

Acquedotti romani

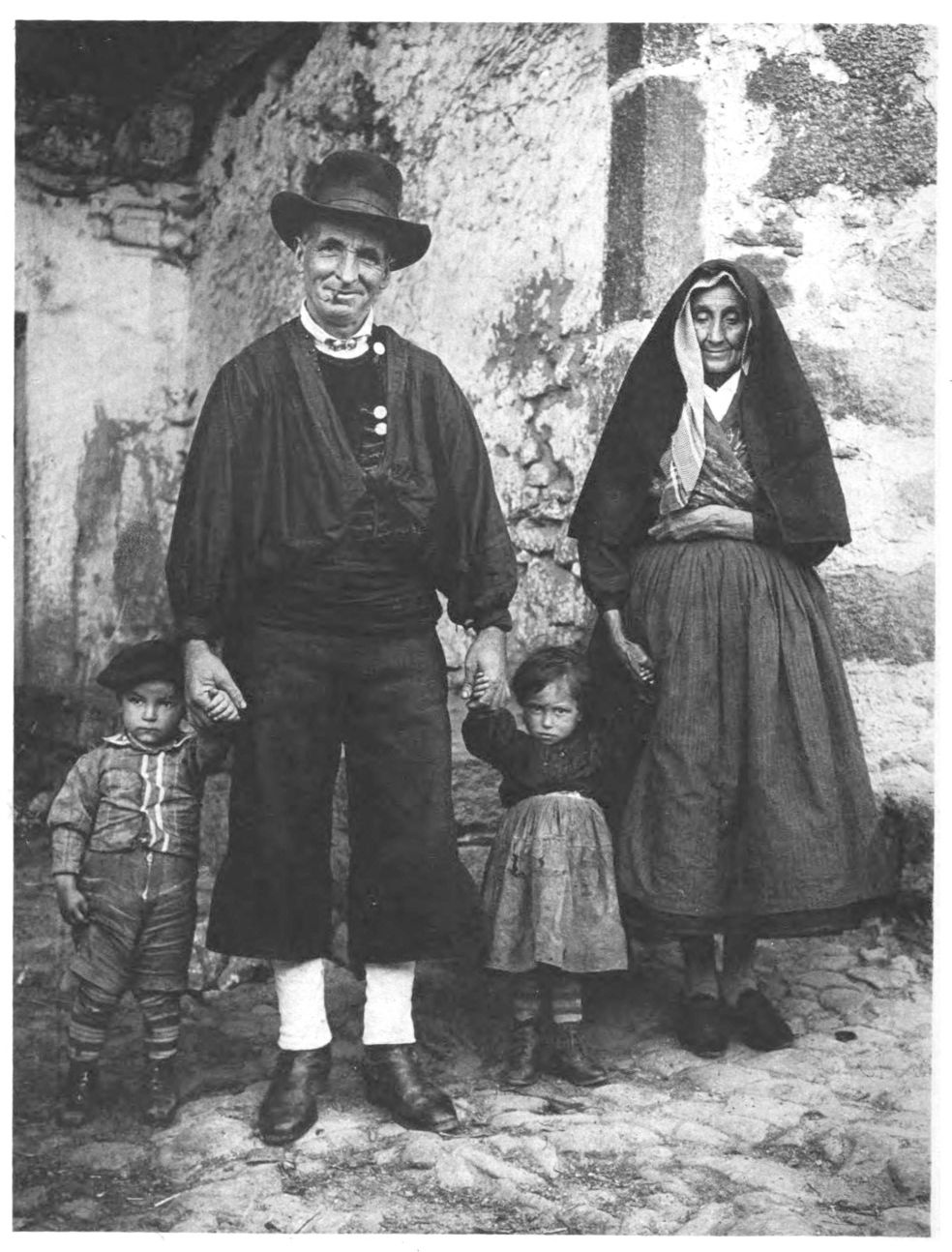

Segovianian peasant. In the background the Segovia Alcázar

Aldeano segoviano, en el fondo el Alcázar de Segovia

Segovianischer Bauer, im Hintergrund der Alcazar von Segovia