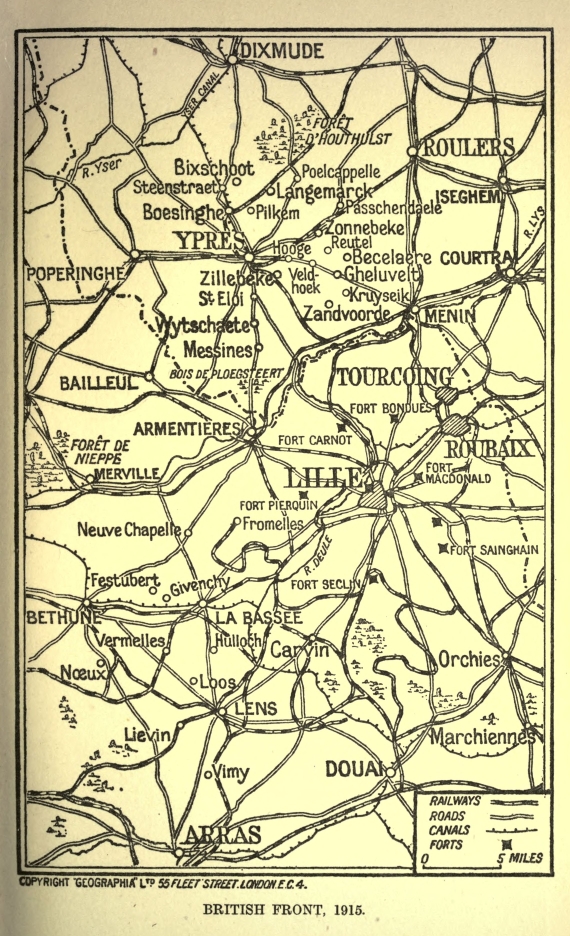

BRITISH FRONT, 1915.

Title: The British Campaign in France and Flanders, 1915

Author: Arthur Conan Doyle

Release date: April 9, 2021 [eBook #65043]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Al Haines

BY

ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

AUTHOR OF

'THE GREAT BOER WAR,' ETC.

SECOND EDITION

HODDER AND STOUGHTON

LONDON NEW YORK TORONTO

MCMXVII

UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

THE BRITISH CAMPAIGN

IN FRANCE AND FLANDERS

1914

LONDON: HODDER AND STOUGHTON

PREFACE

In the previous volume of this work, which dealt with the doings of the British Army in France and Flanders during the year 1914, I ventured to claim that a great deal of it was not only accurate but that it was very precisely correct in its detail. This claim has been made good, for although many military critics and many distinguished soldiers have read it there has been no instance up to date of any serious correction. Emboldened by this I am now putting forward an account of the doings of 1915, which will be equally detailed and, as I hope, equally accurate. In the late autumn a third volume will carry the story up to the end of 1916, covering the series of battles upon the Somme.

The three years of war may be roughly divided into the year of defence, the year of equilibrium, and the year of attack. This volume concerns itself with the second, which in its very nature must be less dramatic than the first or third. None the less it contains some of the most moving scenes of the great world tragedy, and especially the second Battle of Ypres and the great Battle of Loos, two desperate {vi} conflicts the details of which have not, so far as I know, been given up to now to the public.

Now, as before, I must plead guilty to many faults of omission, which often involve some injustice, since an author is naturally tempted to enlarge upon what he knows at the expense of that about which he is less well informed. These faults may be remedied with time, but in the meantime I can only claim indulgence for the obvious difficulty of my task. With the fullest possible information at his disposal, I do not envy the task of the chronicler who has to strike a just balance amid the claims of some fifty divisions.

ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE.

WINDLESHAM, CROWBOROUGH,

April 1917.

CONTENTS

THE OPENING MONTHS OF 1915

Conflict of the 1st Brigade at Cuinchy, and of the 3rd Brigade at Givenchy—Heavy losses of the Guards—Michael O'Leary, V.C.—Relief of French Divisions by the Twenty-seventh and Twenty-eighth British—Pressure on the Fifth Corps—Force subdivided into two armies—Disaster to 16th Lancers—The dearth of munitions

NEUVE CHAPELLE AND HILL 60

The opening of the spring campaign—Surprise of Neuve Chapelle—The new artillery—Gallant advance and terrible losses—The Indians in Neuve Chapelle—A sterile victory—The night action of St. Eloi—Hill 60—The monstrous mine—The veteran 13th Brigade—A bloody battle—London Territorials on the Hill—A contest of endurance—The first signs of poison

THE SECOND BATTLE OF YPRES

(Stage I.—The Gas Attack, April 22-30)

Situation at Ypres—The poison gas—The Canadian ordeal—The fight in the wood of St. Julien—The French recovery—Miracle days—The glorious Indians—The Northern Territorials—Hard fighting—The net result—Loss of Hill 60

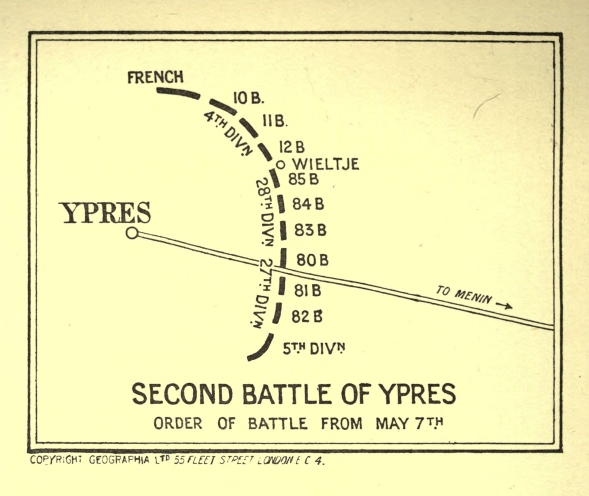

THE SECOND BATTLE OF YPRES

(Stage II.—The Bellewaarde Lines)

The second phase—Attack on the Fourth Division—Great stand of the Princess Pats—Breaking of the line—Desperate attacks—The cavalry save the situation—The ordeal of the 11th Brigade—The German failure—Terrible strain on the British—The last effort of May 24—Result of the battle—Sequence of events

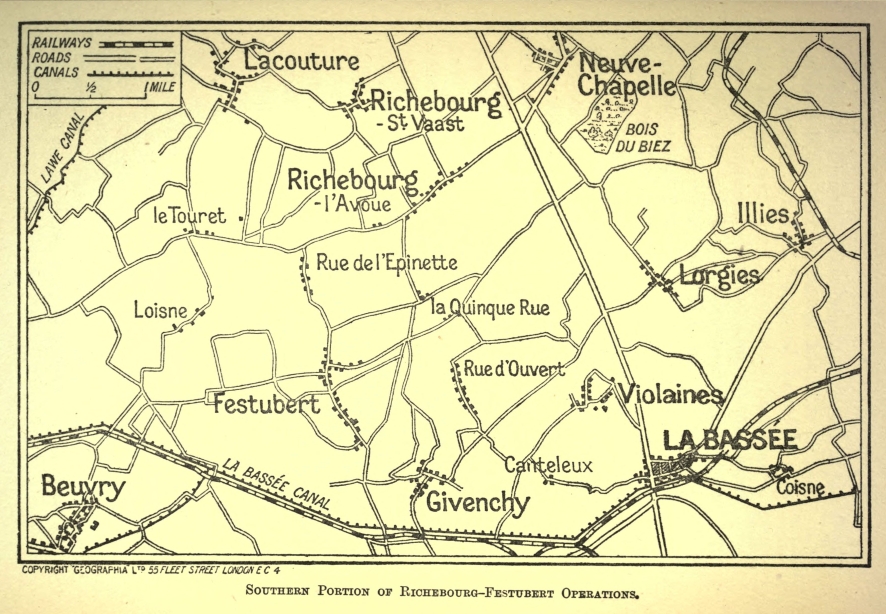

THE BATTLE OF RICHEBOURG-FESTUBERT

(May 9-24)

The new attack—Ordeal of the 25th Brigade—Attack of the First Division—Fateful days—A difficult situation—Attack of the Second Division—Attack of the Seventh Division—British success—Good work of the Canadians—Advance of the Forty-seventh London Division—The lull before the storm

THE TRENCHES OF HOOGE

The British line in June 1915—Canadians at Givenchy—Attack of 154th Brigade—8th Liverpool Irish—Third Division at Hooge—11th Brigade near Ypres—Flame attack on the Fourteenth Light Division—Victory of the Sixth Division at Hooge

THE BATTLE OF LOOS

(The First Day—September 25)

General order of battle—Check of the Second Division—Advance of the Ninth and Seventh Divisions—Advance of the First Division—Fine progress of the Fifteenth Division—Capture of Loos—Work of the Forty-seventh London Division

THE BATTLE OF LOOS

(The Second Day—September 26)

Death of General Capper—Retirement of the Fifteenth Division—Advance of the Twenty-fourth and Twenty-first Divisions—Heavy losses—Desperate struggle—General retirement on the right—Rally round Loos—Position in the evening

THE BATTLE OF LOOS

(From September 27 to the end of the year)

Loss of Fosse 8—Death of General Thesiger—Advance of the Guards—Attack of the Twenty-eighth Division—Arrival of the Twelfth Division—German counter-attacks—Attack by the Forty-sixth Division upon Hohenzollern Redoubt—Subsidiary attacks—General observations—Return of Lord French to England

MAPS AND PLANS

Map to illustrate the British Campaign in France and Flanders [Transcriber's note: omitted from ebook because its size and fragility made it impractical to scan]

Conflict of the 1st Brigade at Cuinchy, and of the 3rd Brigade at Givenchy—Heavy losses of the Guards—Michael O'Leary, V.C.—Relief of French Divisions by the Twenty-seventh and Twenty-eighth British—Pressure on the Fifth Corps—Force subdivided into two armies—Disaster to 16th Lancers—The dearth of munitions.

The weather after the new year was atrocious, heavy rain, frost, and gales of wind succeeding each other with hardly a break. The ground was so sodden that all movements of troops became impossible, and the trench work was more difficult than ever. The British, with their steadily increasing numbers, were now able to take over some of the trenches of the French and to extend their general line. This trench work came particularly hard upon the men who were new to the work and often fresh from the tropics. A great number of the soldiers contracted frost-bite and other ailments. The trenches were very wet, and the discomfort was extreme. There had been some thousands of casualties in the Fifth Corps from this cause before it can be said to have been in action. On the other hand, the medical service, which was extraordinarily efficient, did everything possible to preserve the health of the men. Wooden troughs were provided as a stance for them in the trenches, {2} and vats heated to warm them when they emerged. Considering that typhoid fever was common among the civilian residents, the health of the troops remained remarkably good, thanks to the general adoption of inoculation, a practice denounced by a handful of fanatics at home, but of supreme importance at the front, where the lesson of old wars, that disease was more deadly than the bullet, ceased to hold good.

On January 25 the Germans again became aggressive. If their spy system is as good as is claimed, they must by this time have known that all talk of bluff in connection with the new British armies was mere self-deception, and that if ever they were to attempt anything with a hope of success, it must be speedily before the line had thickened. As usual there was a heavy bombardment, and then a determined infantry advance—this time to the immediate south of the Bethune Canal, where there was a salient held by the 1st Infantry Brigade with the French upon their right. The line was thinly held at the time by a half-battalion 1st Scots Guards and a half-battalion 1st Coldstream, a thousand men in all. One trench of the Scots Guards was blown up by a mine and the German infantry rushed it, killing, wounding, or taking every man of the 130 defenders. Three officers were hit, and Major Morrison-Bell, a member of parliament, was taken after being buried in the debris of the explosion. The remainder of the front line, after severe losses both in casualties and in prisoners, fell back from the salient and established themselves with the rest of their respective battalions on a straight line of defence, one flank on the canal, the other on the main Bethune-La Bassée high road. {3} A small redoubt or keep had been established here, which became the centre of the defence.

Whilst the advance of the enemy was arrested at this line, preparations were made for a strong counter-attack. An attempt had been made by the enemy with their heavy guns to knock down the lock gates of the canal and to flood the ground in the rear of the position. This, however, was unsuccessful, and the counter-attack dashed to the front. The advancing troops consisted of the 1st Black Watch, part of the 1st Camerons, and the 2nd Rifles from the reserve. The London Scottish supported the movement. The enemy had flooded past the keep, which remained as a British island in a German lake. They were driven back with difficulty, the Black Watch advancing through mud up to their knees and losing very heavily from a cross fire. Two companies were practically destroyed. Finally, by an advance of the Rifles and 2nd Sussex after dark the Germans were ousted from all positions in advance of the keep, and this line between the canal and the road was held once more by the British. The night fell, and after dark the 1st Brigade, having suffered severely, was withdrawn, and the 2nd Brigade remained in occupation with the French upon their right. This was the action of Cuinchy falling upon the 1st Brigade, supported by part of the 2nd.

Whilst this long-drawn fight of January 25 had been going on to the south of the canal, there had been a vigorous German advance to the north of it, over the old ground which centres on Givenchy. The German attack, which came on in six lines, fell principally upon the 1st Gloucesters, who held the front trench. Captain Richmond, who commanded {4} the advanced posts, had observed at dawn that the German wire had been disturbed and was on the alert. Large numbers advanced, but were brought to a standstill about forty yards from the position. These were nearly all shot down. Some of the stormers broke through upon the left of the Gloucesters, and for a time the battalion had the enemy upon their flank and even in their rear, but they showed great steadiness and fine fire discipline. A charge was made presently upon the flank by the 2nd Welsh aided by a handful of the Black Watch under Lieutenant Green, who were there as a working party, but found more congenial work awaiting them. Lieutenant Bush of the Gloucesters with his machine-guns did particularly fine work. This attack was organised by Captain Rees, aided by Major MacNaughton, who was in the village as an artillery observer. The upshot was that the Germans on the flank were all killed, wounded, or taken. A remarkable individual exploit was performed by Lieutenant James and Corporal Thomas of the Welsh, who took a trench with 40 prisoners. A series of attacks to the north-east of the village were also repulsed, the South Wales Borderers doing some splendid work.

Thus the results of the day's fighting was that on the north the British gained a minor success, beating off all attacks, while to the south the Germans could claim an advantage, having gained some ground. The losses on both sides were considerable, those of the British being principally among Scots Guards, Coldstream and Black Watch to the south, and Welsh to the north. The action was barren of practical results.

There were some days of quiet, and then upon January 29 the Fourteenth German Corps buzzed {5} out once more along the classic canal. This time they made for the keep, which has already been mentioned, and endeavoured to storm it with the aid of axes and scaling ladders. Solid Sussex was inside the keep, however, and ladders and stormers were hurled to the ground, while bombs were thrown on to the heads of the attackers. The Northamptons to the south were driven out for an instant, but came back with a rush and drove off their assailants. The skirmish cost the British few casualties, but the enemy lost heavily, leaving two hundred of his dead behind him. "Having arranged a code signal we got the first shell from the 40th R.F.A. twelve seconds after asking for it." So much for the co-operation between our guns and our infantry.

On February 1 the Guards who had suffered in the first fight at Cuinchy got back a little of what was owing to them. The action began by a small post of the 2nd Coldstream of the 4th Brigade being driven back. An endeavour was made to reinstate it in the early morning, but it was not successful. After daylight there was a proper artillery preparation, followed by an assault by a storming party of Coldstream and Irish Guards, led by Captain Leigh Bennett and Lieutenant Graham. The lost ground and a German trench beyond it were captured with 32 prisoners and 2 machine-guns. It was in this action that Michael O'Leary, the gallant Irish Guardsman, shot or bayoneted eight Germans and cleared a trench single-handed, one of the most remarkable individual feats of the War, for which a Victoria Cross was awarded. Again the fight fell upon the 4th Brigade, where Lord Cavan was gaining something of the reputation of his brother peer, Lord {6} "Salamander" Cutts, in the days of Marlborough. On February 6 he again made a dashing attack with a party of the 3rd Coldstream and Irish, in which the Germans were driven out of the Brickfield position. The sappers under Major Fowkes rapidly made good the ground that the infantry had won, and it remained permanently with the British.

Another long lull followed this outburst of activity in the region of the La Bassée Canal, and the troops sank back once more into their muddy ditches, where, under the constant menace of the sniper, the bomb and the shell, they passed the weary weeks with a patience which was as remarkable as their valour. The British Army was still gradually relieving the French troops, who had previously relieved them. Thus in the north the newly-arrived Twenty-seventh and Twenty-eighth Divisions occupied several miles which had been held on the Ypres salient by General D'Urbal's men. Unfortunately, these two divisions, largely composed of men who had come straight from the tropics, ran into a peculiarly trying season of frost and rain, which for a time inflicted great hardship and loss upon them. To add to their trials, the trenches at the time they took them over were not only in a very bad state of repair, but had actually been mined by the Germans, and these mines were exploded shortly after the transfer, to the loss of the new occupants. The pressure of the enemy was incessant and severe in this part of the line, so that the losses of the Fifth Corps were for some weeks considerably greater than those of all the rest of the line put together. Two of the veteran brigades of the Second Corps, the 9th Fusilier Brigade (Douglas Smith) and the 13th (Wanless {7} O'Gowan), were sent north to support their comrades, with the result that this sector was once again firmly held. Any temporary failure was in no way due to a weakness of the Fifth Army Corps, who were to prove their mettle in many a future fight, but came from the fact, no doubt unavoidable but none the less unfortunate, that these troops, before they had gained any experience, were placed in the very worst trenches of the whole British line. "The trenches (so called) scarcely existed," said one who went through this trying experience, "and the ruts which were honoured with the name were liquid. We crouched in this morass of water and mud, living, dying, wounded and dead together for 48 hours at a stretch." Add to this that the weather was bitterly cold with incessant rain, and more miserable conditions could hardly be imagined. In places the trenches of the enemy were not more than twenty yards off, and the shower of bombs was incessant.

The British Army had now attained a size when it was no longer proper that a corps should be its highest unit. From this time onwards the corps were themselves distributed into different armies. At present, two of these armies were organised. The First, under General Sir Douglas Haig, comprised the First Corps, the Fourth Corps (Rawlinson), and the Indian Corps. The Second Army contained the Second Corps (Ferguson), the Third Corps (Pulteney), and the Fifth Corps (Plumer), all under Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien. The new formations as they came out were either fitted into these or formed part of a third army. Most of the brigades were strengthened by the addition of one, and often of two territorial battalions. Each army consisted roughly at this {8} time of 120,000 men. The Second Army was in charge of the line to the north, and the First to the south.

On the night of February 14 Snow's Twenty-seventh Division, which had been somewhat hustled by the Germans in the Ypres section, made a strong counter-attack under the cover of darkness, and won back four trenches near St. Eloi from which they had been driven by a German rush. This dashing advance was carried out by the 82nd Brigade (Longley's), and the particular battalions which were most closely engaged were the 2nd Cornwalls, the 1st Royal Irish, and 2nd Royal Irish Fusiliers. They were supported by the 80th Brigade (Fortescue's). The losses amounted to 300 killed and wounded. The Germans lost as many and a few prisoners were taken. The affair was of no great consequence in itself, but it marked a turn in the affairs of Plumer's Army Corps, whose experience up to now had been depressing. The enemy, however, was still aggressive and enterprising in this part of the line. Upon the 20th they ran a mine under a trench occupied by the 16th Lancers, and the explosion produced most serious effects. 5 officers killed, 3 wounded, and 60 men hors de combat were the fruits of this unfortunate incident, which pushed our trenches back for 40 yards on a front of 150 yards. The Germans had followed up the explosion by an infantry attack, which was met and held by the remains of the 16th, aided by a handful of French infantry and a squadron of the 11th Hussars. On this same day an accidental shot killed General Gough, chief staff officer of the First Corps, one of the most experienced and valuable leaders of the Army.

On the 21st, the Twenty-eighth Division near Ypres {9} had a good deal of hard fighting, losing trenches and winning them, but coming out at the finish rather the loser on balance. The losses of the day were 250 killed and wounded, the greatest sufferers being the Royal Lancasters. Somewhat south of Ypres, at Zwarteleen, the 1st West Kents were exposed to a shower of projectiles from the deadly minenwerfer, which are more of the nature of aerial torpedoes than ordinary bombs. Their losses under this trying ordeal were 3 officers and 19 men killed, 1 officer and 18 men wounded. There was a lull after this in the trench fighting for some little time, which was broken upon February 28 by a very dashing little attack of the Princess Patricia's Canadian regiment, which as one of the units of the 80th Brigade had been the first Canadian Battalion to reach the front. Upon this occasion, led by Lieutenants Crabb and Papineau, they rushed a trench in their front, killed eleven of its occupants, drove off the remainder, and levelled it so that it should be untenable. Their losses in this exploit were very small. During this period of the trench warfare it may be said generally that the tendency was for the Germans to encroach upon British ground in the Ypres section and for the British to take theirs in the region of La Bassée.

With the opening of the warmer weather great preparations had been made by Great Britain for carrying on the land campaign, and these now began to bear fruit. Apart from the numerous Territorial regiments which had already been incorporated with regular brigades—some fifty battalions in all—there now appeared several divisions entirely composed of Territorials. The 46th North Midland and 48th South Midland Divisions were the first to form independent {10} units, but they were soon followed by others. It had been insufficiently grasped that the supply of munitions was as important as that of men, and that the expenditure of shell was something so enormous in modern warfare that the greedy guns, large and small, could keep a great army of workmen employed in satisfying their immoderate demands. The output of shells and cartridges in the month of March was, it is true, eighteen times greater than in September, and 3000 separate firms were directly or indirectly employed in war production; but operations were hampered by the needs of batteries which could consume in a day what the workshops could at that time hardly produce in a month. Among the other activities of Great Britain at this period was the great strengthening of her heavy artillery, in which for many months her well-prepared enemy had so vast an advantage. Huge engines lurked in the hearts of groves and behind hillocks at the back of the British lines, and the cheery news went round that even the heaviest bully that ever came out of Essen would find something of its own weight stripped and ready for the fray.

There was still considerable activity in the St. Eloi sector south-east of Ypres, where the German attacks were all, as it proved, the preliminaries of a strong advance. So persistent were they that Plumer's men were constantly striving for elbow room. On March 2 part of Fortescue's 80th Brigade, under Major Widdington of the 4th Rifles, endeavoured to push back the pressure in this region, and carried the nearest trench, but were driven out again by the German bombs. The losses were about 200, of which 47 fell upon the 3rd, and 110 upon the 4th {11} Rifles. In these operations a very great strain came upon the Engineers, who were continually in front of the trenches at night, fixing the wire entanglements and doing other dangerous work under the very rifles of the Germans. It is pleasing to record that in this most hazardous task the Territorial sappers showed that they were worthy comrades of the Regulars. Major Gardner, Commander of the North Midland Field Company, and many officers and men died in the performance of this dangerous duty.

The opening of the spring campaign—Surprise of Neuve Chapelle—The new artillery—Gallant advance and terrible losses—The Indians in Neuve Chapelle—A sterile victory—The night action of St. Eloi—Hill 60—The monstrous mine—The veteran 13th Brigade—A bloody battle—London Territorials on the Hill—A contest of endurance—The first signs of poison.

We now come to the close of the long period of petty and desultory warfare, which is only relieved from insignificance by the fact that the cumulative result during the winter was a loss to the Army of not less than twenty thousand men. With the breaking of the spring and the drying of the water-soaked meadows of Flanders, an era of larger and more ambitious operations had set in, involving, it is true, little change of position, but far stronger forces on the side of the British. The first hammer-blow of Sir John French was directed, upon March 10, against that village of Neuve Chapelle which had, as already described, changed hands several times, and eventually remained with the Germans during the hard fighting of Smith-Dorrien's Corps in the last week of October. The British trenches had been drawn a few hundred yards to the west of the village, and there had been no change during the last four months. Behind the village was the Aubers Ridge, and behind that again {13} the whole great plain of Lille and Turcoing. This was the spot upon which the British General had determined to try the effects of his new artillery.

The British surprise.

His secret was remarkably well kept. Few British and and no Germans knew where the blow was to fall. The boasted spy system was completely at fault. The success of Sir John in keeping his secret was largely dependent upon the fact that above the British lines an air space had been cleared into which no German airman could enter save at his own very great peril. No great movement of troops was needed since Haig's army lay opposite to the point to be attacked, and it was to two of his corps that the main assault was assigned. On the other hand, there was a considerable concentration of guns, which were arranged, over three hundred in number, in such a position that their fire could converge from various directions upon the area of the German defences.

It was planned that Smith-Dorrien, along the whole line held by the Second Army to the north, should demonstrate with sufficient energy to hold the Germans from reinforcing their comrades. To the south of the point of attack, the First Army Corps in the Givenchy neighbourhood had also received instructions to make a strong demonstration. Thus the Germans of Neuve Chapelle, who were believed to number only a few battalions, were isolated on either side. It was advisable also to hinder their reinforcements coming from the reserves in the northern towns behind the fighting lines. With this object, instructions were given to the British airmen at any personal risk to attack all the railway points along which the trains could come. This was duly done, and the junctions of Menin, Courtrai, Don, and Douai were {14} attacked, Captain Carmichael and other airmen bravely descending within a hundred feet of their mark.

The troops chosen for the assault were Rawlinson's Fourth Army Corps upon the left and the Indian Corps upon the right, upon a front of half a mile, which as the operation developed broadened to three thousand yards. The object was not the mere occupation of the village, but an advance to the farthest point attainable. The Second Division of Cavalry was held in reserve, to be used in case the German line should be penetrated. All during the hours of the night the troops in single file were brought up to the advanced trenches, which in many cases were less than a hundred yards from the enemy. Before daylight they were crammed with men waiting most eagerly for the signal to advance. Short ladders had been distributed, so that the stormers could swarm swiftly out of the deep trenches.

The obstacle in front of the Army was a most serious one. The barbed wire entanglements were on an immense scale, the trenches were bristling with machine-guns, and the village in the rear contained several large outlying houses with walls and orchards, each of which had been converted into a fortress. On the other hand, the defenders had received no warning, and therefore no reinforcement, so that the attackers were far the more numerous. It is said that a German officer's attention was called to the stir in the opposing trenches, and that he was actually at the telephone reporting his misgivings to headquarters when the storm broke loose.

Terrific bombardment.

It was at half-past seven that the first gun boomed from the rear of the British position. Within a few {15} minutes three hundred were hard at work, the gunners striving desperately to pour in the greatest possible number of shells in the shortest period of time. It had been supposed that some of the very heavy guns could get in forty rounds in the time, but they actually fired nearly a hundred, and at the end of it the huge garrison gunners were lying panting like spent hounds round their pieces. From the 18-pounder of the field-gun to the huge 1400-pound projectile from the new monsters in the rear, a shower of every sort and size of missile poured down upon the Germans, many of whom were absolutely bereft of their senses by the sudden and horrible experience. Trenches, machine-guns, and human bodies flew high into the air, while the stakes which supported the barbed wire were uprooted, and the wire itself torn into ribbons and twisted into a thousand fantastic coils with many a gap between. In front of part of the Indian line there was a clean sweep of the impediments. So also to the right of the British line. Only at the left of the line, to the extreme north of the German position, was the fatal wire still quite unbroken and the trenches unapproachable. Meanwhile, so completely was the resistance flattened out by the overpowering weight of fire that the British infantry, with their own shells flowing in a steady stream within a few feet of their heads, were able to line their parapets and stare across at the wonderful smoking and roaring swirl of destruction that faced them. Here and there men sprang upon the parapets waving their rifles and shouting in the hot eagerness of their hearts. "Our bomb-throwers," says one correspondent, "started cake-walking." It was but half an hour that they waited, and yet to many it seemed {16} the longest half-hour of their lives. It was an extraordinary revelation of the absolute accuracy of scientific gunfire that the British batteries should dare to shell the German trenches which were only a hundred yards away from their own, and this at a range of five or six thousand yards.

The infantry attack.

At five minutes past eight the guns ceased as suddenly as they had begun, the shrill whistles of the officers sounded all along the line, and the ardent infantry poured over the long lip of the trenches. The assault upon the left was undertaken by Pinney's 23rd Infantry Brigade of the Eighth Division. The 25th Brigade of the same division (Lowry-Cole's) was on the right, and on the right of them again were the Indians. The 25th Brigade was headed by the 2nd Lincolns (left) and the 2nd Berkshires (right), who were ordered to clear the trenches, and then to form a supporting line while their comrades of the 1st Irish Rifles (left) and the 2nd Rifle Brigade (right) passed through their ranks and carried the village beyond. The 1st Londons and 13th London (Kensingtons) were pressing up in support. Colonel McAndrew, of the Lincolns, was mortally hit at the outset, but watched the assault with constant questions as to its progress until he died. It was nothing but good news that he heard, for the work of the brigade went splendidly from the start. It overwhelmed the trenches in an instant, seizing the bewildered survivors, who crouched, yellow with lyddite and shaken by the horror of their situation, in the corners of the earthworks. As the Berkshires rushed down the German trench they met with no resistance at all, save from two gallant German officers, who fought a machine-gun until both were bayoneted.

The ordeal of the 23rd Brigade.

It was very different, however, with the 23rd Brigade upon the left. Their experience was a terrible one. As they rushed forward, they came upon a broad sheet of partly-broken wire entanglement between themselves and the trenches which had escaped the artillery fire. The obstacle could not be passed, and yet the furious men would not retire, but tore and raged at the edge of the barrier even as their ancestors raged against the scythe-blades of the breach of Badajoz. The 2nd Scottish Rifles and the 2nd Middlesex were the first two regiments, and their losses were ghastly. Of the Scottish Rifles, Colonel Bliss was killed, every officer but one was either killed or wounded, and half the men were on the ground. The battalion found some openings, however, especially B Company (Captain Ferrers), upon their right flank, and in spite of their murderous losses made their way into the German trenches, the bombardiers, under Lieutenant Bibby, doing fine work in clearing them, though half their number were killed. The Middlesex men, after charging through a driving sleet of machine-gun bullets, were completely held up by an unbroken obstacle, and after three gallant and costly attacks, when the old "Die-hards" lived up to their historic name, the remains of the regiment were compelled to move to the right and make their way through the gap cleared by the Scottish Rifles. "Rally, boys, and at it again!" they yelled at every repulse. The 2nd Devons and 2nd West Yorkshires were in close support of the first line, but their losses were comparatively small. The bombers of the Devons, under Lieutenant Wright, got round the obstacle and cleared two hundred yards of trench. On account of the impregnable {18} German position upon the left, the right of the brigade was soon three hundred yards in advance and suffered severely from the enfilade fire of rifles and machine-guns, the two flanks being connected up by a line of men facing half left, and making the best of the very imperfect cover.

It should be mentioned that the getting forward of the 23rd Brigade was largely due to the personal intervention of General Pinney, who, about 8.30, hearing of their difficult position, came forward himself across the open and inspected the obstacle. He then called off his men for a breather while he telephoned to the gunners to reopen fire. This cool and practical manoeuvre had the effect of partly smashing the wires. At the same time much depended upon the advance of the 25th Brigade. Having, as stated, occupied the position which faced them, they were able to outflank the section of the German line which was still intact. Their left flank having been turned, the defenders fell back or surrendered, and the remains of the 23rd Brigade were able to get forward into an alignment with their comrades, the Devons and West Yorkshires passing through the thinned ranks in front of them. The whole body then advanced for about a thousand yards.

At this period Major Carter Campbell, who had been wounded in the head, and Second Lieutenant Somervail, from the Special Reserve, were the only officers left with the Scottish Rifles; while the Middlesex were hardly in better case. Of the former battalion only 150 men could be collected after the action. The 24th Brigade was following closely behind the other two, and the 1st Worcesters, 2nd East Lancashires, 1st Sherwood Foresters, and 2nd {19} Northampton were each in turn warmly engaged as they made good the ground that had been won. The East Lancashires materially helped to turn the Germans out of the trenches on the left.

Gallant Indian advance.

Whilst the British brigades had been making this advance upon the left the Indians had dashed forward with equal fire and zeal upon the right. It was their first real chance of attack upon a large scale, and they rose grandly to the occasion. The Garhwali Brigade attacked upon the left of the Indian line, with the Dehra Duns (Jacob) upon their right, and the Bareillys (Southey) in support, all being of the Meerut Division. The Garhwalis, consisting of men from the mountains of Northern India, advanced with reckless courage, the 39th Regiment upon the left, the 3rd Gurkhas in the centre, the 2nd Leicesters upon the right, while the 8th Gurkhas, together with the 3rd London Territorials and the second battalion of the Garhwalis, were in support. Part of the front was still covered with wire, and the Garhwalis were held up for a time, but the Leicesters, on their right, smashed a way through all obstacles. Their Indian comrades endured the loss of 20 officers and 350 men, but none the less they persevered, finally swerving to the right and finding a gap which brought them through. The Gurkhas, however, had passed them, the agile little men slipping under, over, or through the tangled wire in a wonderful fashion. The 3rd Londons closely followed the Leicesters, and were heavily engaged for some hours in forcing a stronghold on the right flank, held by 70 Germans with machine-guns. They lost 2 officers, Captain Pulman and Lieutenant Mathieson, and 50 men of A Company, but stuck to their task, and eventually, with the help {20} of a gun, overcame the resistance, taking 50 prisoners. The battalion lost 200 men and did very fine work. Gradually the Territorials were winning their place in the Army. "They can't call us Saturday night soldiers now," said a dying lad of the 3rd Londons; and he spoke for the whole force who have endured perverse criticism for so long.

The moment that the infantry advance upon the trenches had begun, the British guns were turned upon the village itself. Supported by their fire, as already described, the victorious Indians from the south and the 25th Brigade from the west rushed into the streets and took possession of the ruins which flanked them, advancing with an ardour which brought them occasionally into the zone of fire from their own guns. By twelve o'clock the whole position, trenches, village, and detached houses, had been carried, while the artillery had lengthened its range and rained shrapnel upon the ground over which reinforcements must advance. The Rifles of the 25th Brigade and the 3rd Gurkhas of the Indians were the first troops in Neuve Chapelle.

It is not to be imagined that the powerful guns of the enemy had acquiesced tamely in these rapid developments. On the contrary, they had kept up a fire which was only second to that of the British in volume, but inferior in effect, since the latter had registered upon such fixed marks as the trenches and the village, while the others had but the ever-changing line of an open order attack. How dense was the fall of the German shells may be reckoned from the fact that the telephone lines by which the observers in the firing line controlled the gunners some miles behind them were continually severed, {21} although they had been laid down in duplicate, and often in triplicate. There were heavy losses among the stormers, but they were cheerfully endured as part of the price of victory. The jovial exultation of the wounded as they were carried or led to the dressing stations was one of the recollections which stood out clearest amid the confused impressions which a modern battle leaves upon the half-stunned mind of the spectator.

At twelve o'clock the position had been carried, and yet it was not possible to renew the advance before three. These few hours were consumed in rearranging the units, which had been greatly mixed up during the advance, in getting back into position the left wing of the 25th Brigade, which had been deflected by the necessity of relieving the 23rd Brigade, and in bringing up reserves to take the place of regiments which had endured very heavy losses. Meanwhile the enemy seemed to have been completely stunned by the blow which had so suddenly fallen upon him. The fire from his lines had died down, and British brigades on the right, forming up for the renewed advance, were able to do so unmolested in the open, amid the horrible chaos of pits, mounds, wire tangles, splintered woodwork, and shattered bodies which marked where the steel cyclone had passed. The left was still under very heavy fire.

The reserved advance.

At half-past three the word was given, and again the eager khaki fringe pushed swiftly to the front, On the extreme left of the line of attack Watts's 21st Brigade pushed onwards with fierce impetuosity. This attack was an extension to the left of the original attack. The 21st was the only brigade of the Seventh Division to be employed that day. There is a hamlet {22} to the north-east of Neuve Chapelle called Moulin-du-Piètre, and this was the immediate objective of the attack. Several hundreds of yards were gained before the advance was held up by a severe fire from the houses, and by the discovery of a fresh, undamaged line of German trenches opposite to the right of the 21st Brigade. Here the infantry was held, and did no more than keep their ground until evening. Their comrades of the Eighth Division upon their right had also advanced, the 24th Brigade (Carter's) taking the place of the decimated 23rd in the front line; but they also came to a standstill under the fire of German machine-guns, which were directed from the bridge crossing the stream of the little Des Layes River in front of them.

The Bois du Biez is an important wood on the south-east of Neuve Chapelle, and the Indians, after their successful assault, directed their renewed advance upon this objective. The Garhwali Brigade, which had helped to carry the village, was now held back, and the Dehra Dun Brigade of 1st and 4th Seaforths, Jats, and Gurkhas, supported by the Jullundur Brigade from the Lahore Division, moved forward to carry the wood. They gained a considerable stretch of ground by a magnificent charge over the open, but were held up along the line of the river as their European comrades had been to the north. More than once the gallant Indians cleared the wood, but could not permanently hold it. The German post at the bridge was able to enfilade the line, and our artillery was unable to drive it out. Three regiments of the 1st Brigade were brought up to Richebourg in support of the attack, but darkness came on before the preparations were complete. The troops slept {23} upon the ground which they had won, ready and eager for the renewal of the battle in the morning. The losses had been heavy during the day, falling with undue severity upon a few particular battalions; but the soldiers were of good heart, for continual strings of German prisoners, numbering nine hundred in all, had been led through their lines, and they had but to look around them to assure themselves of the loss which they had inflicted upon the enemy. In that long winter struggle a few yards to west or east had been a matter for which a man might gladly lay down his life, so that now, when more than a thousand yards had been gained by a single forward spring, there was no desire to flinch from the grievous cost.

Subsidiary attacks.

It has already been stated that the British had made demonstrations to right and to left in order to hold the enemy in their trenches. In the case of Smith-Dorrien's Second Army, a bombardment along the line was sufficient for the purpose. To the south, however, at Givenchy, the First Corps made an attack upon the trenches two hundred yards in front of them, which had no success, as the wire had been uncut. This attack was carried out by Fanshawe's 6th Infantry Brigade, and if it failed the failure was not due to want of intrepid leading by the officers and desperate courage of the men. The 1st King's (Liverpool) suffered very heavily in front of the impassable wire. "Our boys took their bayonets and hacked away. It was impossible to break through." Colonel Carter was wounded, but continued to lead his men. Feveran and Suatt, who led the assault, were respectively killed and wounded. The officers were nearly all hit, down to the young Subaltern Webb, who kept shouting "Come on, the {24} King's!" until he could shout no more. A hundred were killed and 119 wounded in the ranks. Both the 2nd South Staffords and the 1st King's Royal Rifles joined in this brave, but ineffectual, attack, and lost very heavily. The total loss of the brigade was between six and seven hundred, but at least it had prevented this section of the line from reinforcing Neuve Chapelle. All along the line the night was spent in making good the ground that had been won.

Second day of battle.

The morning of the 11th broke with thick mist, a condition which continued during the whole of the day. Both the use of the aircraft and the direction of the artillery were negatived by the state of the weather—a grievous piece of ill-fortune, as it put a stop to any serious advance during the day, since it would have been a desperate business to march infantry against a difficult front without any artillery preparation. In this way the Germans gained a precious respite during which they might reinforce their line and prepare for a further attack. They essayed a counter-attack from the Bois du Biez in the morning, but it was easily repulsed by the Indians. Their shell-fire, however, was very murderous. The British infantry still faced Moulin-du-Piètre in the north and the Bois du Biez in the south, but could make no progress without support, while they lost heavily from the German artillery. The Indians were still at the south of the line, the 24th Brigade in the middle and the 21st in the north. Farther north still, at a point just south of Armentières, a useful little advance was made, for late at night, or early in the morning of the 12th, the 17th Infantry Brigade (Harper's) had made a swift dash at the village of {25} l'Epinette, calculating, no doubt, that some of its defenders had been drafted south to strengthen the stricken line. The place was carried by storm at the small cost of five officers and thirty men, and the line carried forward at this point to a depth of three hundred yards over a front of half a mile. A counter-attack upon the 13th was driven off with loss.

Third day.

So far as the main operation was concerned, the weather upon the 12th was hardly more favourable than upon the 11th. The veil of mist still intervened between the heavy artillery and its target. Three aeroplanes were lost in the determined efforts of the airmen to get close observation of the position. It also interfered with the accuracy of the German fire, which was poured upon the area held by the British troops, but inflicted small damage upon them. The day began by an attack in which the Germans got possession of a trench held by the 1st Sherwood Foresters. As the mist rose the flank company of the 2nd West Yorks perceived these unwelcome neighbours and, under the lead of Captain Harrington, turned them out again. Both the Indians on the right and the Seventh Division on the left lost a number of men during the morning in endeavouring, with poor success, to drive the German garrisons out of the various farmhouses, which were impregnable to anything but artillery. The gallant 20th Brigade, which had done such great work at Ypres in October, came into action this day and stormed up to the strongholds of the Moulin-du-Piètre. One of them, with three hundred Germans inside, was carried by the 2nd Borders, the defenders being made prisoners. All the battalions of the brigade—the 2nd Scots Guards, the 1st Grenadiers, the 2nd Gordons, and their {26} Territorial comrades, the 6th Gordons—lost heavily in this most desperate of all forms of fighting. Colonel McLean of the latter regiment died at the head of his men. "Go about your duty," was his last speech to those who tended him. The Grenadiers fought like heroes, and one of them, Corporal Fuller, performed the extraordinary feat of heading off fifty Germans by fleetness of foot, and single-handed compelling the surrender of all of them. At the other end of the line, the 25th Brigade, led by the Rifle Brigade, also made desperate efforts to get on, but were brought to a standstill by the trenches and machine-guns in the houses. The losses of the British upon this day were heavy, but they were a small matter compared to those of the Germans, who made several counter-attacks in close formation from dawn onwards in the vain hope of recovering the ground that had been lost. It is doubtful if in the whole war greater slaughter has been inflicted in a shorter time and in so confined a space as in the case of some of these advances, where whole dense bodies of infantry were caught in the converging fire of machine-guns and rifles. In front of the 1st Worcesters, of the 24th Brigade, alone more than a thousand dead were counted. From the ridge of Aubers, half a mile to the eastward, down to the front of the Indian and British line, the whole sloping countryside was mottled grey with the bodies of the fallen. All that the British had suffered in front of the barbed wire upon the 10th was repaid with heavy interest during the counter-attacks of the 12th. Gradually they faded away and were renewed no more. For the first time in the war the Germans finally abandoned a position that they had lost, and made no further {27} attempt to retake it. The Battle of Neuve Chapelle was at an end, and the British, though their accomplishment fell far short of their hopes, had none the less made a permanent advance of a thousand yards along a front of three thousand, and obtained a valuable position for their operations in the future. The sappers were busy all evening in wiring and sand-bagging the ground gained, while the medical organisation, which was strained to the uttermost, did its work with a bravery and a technical efficiency which could not be surpassed.

Result of Battle of Neuve Chapelle.

Upon the last day of the fighting some 700 more prisoners had been taken, bringing the total number to 30 officers and 1650 men. The original defenders had been men of the Seventh German Corps, raised from Karlsruhe in Westphalia; but the reinforcements which suffered so heavily were either Saxons or Bavarians. The losses of the Germans were estimated, and possibly overestimated, at 18,000 men. The British losses were very heavy, consisting of 562 officers and 12,239 men. Some 1800 of these were returned as "Missing," but these were the men who fell in the advanced attack upon ground which was not retained. Only the wounded fell into the enemy's hands. The Fourth Corps lost 7500 men, and the Indians about 4000.

Of the six brigades of the Fourth Corps, all suffered about equally, except the 22nd, which was not so hard hit as the others. The remaining brigades lost over 25 per cent of their numbers, but nothing of their efficiency and zeal, as they were very soon to show in the later engagements. When one remembers that Julius Cæsar describes an action as a severe one upon the ground that every tenth man was wounded, {28} it may be conjectured that he would have welcomed a legion of Scottish Rifles or Sherwood Foresters. Certainly no British soldier was likely to live long enough to have his teeth worn down by the ration bread, as was the case with the Tenth Legion. The two units named may have suffered most, but the 2nd Lincolns, 2nd Berkshires, 2nd Borders, 2nd Scots Fusiliers, 1st Irish Rifles, 2nd Rifle Brigade, the two battalions of Gordons, and the 1st Worcesters were all badly cut up. Of the five commanding officers of the 20th Brigade, Uniacke of the 2nd Gordons, McLean of the 5th Gordons, and Fisher Rowe of the Grenadiers were killed, while Paynter of the 2nd Scots Guards was wounded. The only survivor, the Colonel of the Borders, was shot a few days later. It was said at the time of the African War that the British colonels had led their men up to and through the gates of Death. The words were still true. Of the brave Indian Corps, the 1st Seaforths, 2nd Leicesters, 39th Garhwalis, with the 3rd and 4th Gurkhas, were the chief sufferers. The 1st Londons, 3rd Londons, and 13th (Kensingtons) had also shown that they could stand punishment with the best.

So ended the Battle of Neuve Chapelle, a fierce and murderous encounter in which every weapon of modern warfare—the giant howitzer, the bomb, and the machine-gun—was used to the full, and where the reward of the victor was a slice of ground no larger than a moderate farm. And yet the moral prevails over the material, and the fact that a Prussian line, built up with four months of labour, could be rushed in a couple of hours, and that by no exertion could a German set foot upon it again, was a hopeful first lesson in the spring campaign.

On March 12 an attack was made upon the enemy's trenches south-west of the village of Wytschaete—the region where, on November 1, the Bavarians had forced back the lines of our cavalry. The advance was delayed by the mist, and eventually was ordered for four in the afternoon. It was carried out by the 1st Wilts and the 3rd Worcesters, of the 7th Brigade (Ballard), advancing for two hundred yards up a considerable slope. The defence was too strong, however, and the attack was abandoned with a loss of 28 officers and 343 men. It may be said, however, to have served the general purpose of diverting troops from the important action in the south. It is to be hoped that this was so, as the attack itself, though fruitless, was carried out with unflinching bravery and devotion.

Action of St. Eloi.

On March 14, two days after the Battle of Neuve Chapelle, the Germans endeavoured to bring about a counter-stroke in the north which should avenge their defeat, arguing, no doubt, that the considerable strength which Haig's First Army had exhibited in the south meant some subtraction from Smith-Dorrien at the other end of the line. This new action broke out at the hamlet of St. Eloi, some miles to the south-east of Ypres, a spot where many preliminary bickerings and a good deal of trench activity had heralded this more serious effort. This particular section of the line was held by the 82nd Brigade (Longley's) of the Twenty-seventh Division, the whole quarter being under the supervision of General Plumer. There was a small mound in a brickfield to the south-east of the village with trenches upon either side of it which were held by the men of the 2nd Cornish Light Infantry. It is a mere clay dump about seventy feet {30} long and twenty feet high. After a brief but furious bombardment, a mine which had been run under this mound was exploded at five in the evening, and both mound and trenches were carried by a rush of German stormers. These trenches in turn enfiladed other ones, and a considerable stretch was lost, including two support trenches west of the mound and close to it, two breastworks and trenches to the north-east of it, and also the southern end of St. Eloi village.

So intense had been the preliminary fire that every wire connecting with the rear had been severed, and it was only the actual explosion upon the mound—an explosion which buried many of the defenders, including two machine-guns with their detachments—which made the situation clear to the artillery in support. The 19th and 20th Brigades concentrated their thirty-six 18-pounders upon the mound and its vicinity. The German infantry were already in possession, having overwhelmed the few survivors of the 2nd Cornwalls and driven back a company of the 2nd Irish Fusiliers, who were either behind the mound or in the adjacent trenches to the east of the village. The stormers had rushed forward, preceded by a swarm of men carrying bombs and without rifles. Behind them came a detachment of sappers with planks, fascines, and sand-bags, together with machine-gun detachments, who dug themselves instantly into the shattered mound. The whole German organisation and execution of the attack were admirable. Lieutenants Fry and Aston of the Cornwall Light Infantry put up a brave fight with their handful of shaken men. As the survivors of the British front line fell back, two companies of the 1st Cambridge Territorials took up {31} a rallying position. The situation was exceedingly obscure from the rear, for, as already stated, all wires had been cut, but daring personal reconnaissance by individual officers, notably Captain Follett and Lieutenant Elton, cleared it up to some extent. By nine o'clock preparations had been made for a counter-attack, the 1st Leinsters and 1st Royal Irish, of the 82nd Brigade, being brought up, while Fortescue's 80th Brigade was warned to support the movement.

It was pitch-dark, and the advance, which could only be organised and started at two in the morning, had to pass over very difficult ground. The line was formed by two companies of the Royal Irish, the Leinster Regiment, and the 4th Rifles in general support. The latter regiment was guided to their position by Captain Harrison, of the Cornwalls, who was unfortunately shot, so that the movement, so far as they were concerned, became disorganised. Colonel Prowse, of the Leinsters, commanded the attack. The Irishmen rushed forward, but the Germans fought manfully, and there was a desperate struggle in the darkness, illuminated only by the quick red flash of the guns and the flares thrown up from the trenches. By the light of these the machine-guns installed upon the mound held up the advance of the Royal Irish, who tried bravely to carry the position, but were forced in the end, after losing Colonel Forbes, to be content with the nearest house, and with gaining a firm grip upon the village. The Leinsters made good progress and carried first a breastwork and then a trench in front of them, but could get no farther. About 4.30 the 80th Brigade joined in the attack. The advance was carried out by the 4th Rifle Brigade upon the right {32} and the Princess Patricia's (Canadians) upon the left, with the Shropshires and the 3rd Rifles in support. It was all-important to get in the attack before daylight, and the result was that the dispositions were necessarily somewhat hurried and incomplete. The Canadians attacked upon the left, but their attack was lacking in weight, being confined to three platoons, and they could make no headway against the fire from the mound. They lost 3 officers and 24 men in the venture. Thesiger's 4th Rifle Brigade directed its attack, not upon the mound, but on a trench at the side of it. This was carried with a rush by Captain Mostyn Pryce's company. Several obstacles were also taken in succession by the Riflemen, but though repeated attempts were made to get possession of the mound, all of them were repulsed. One company, under Captain Selby-Smith, made so determined an attack upon one barricade that all save four were killed or wounded, in spite of which the barricade was actually carried. A second one lay behind, which was taken by Lieutenant Sackville's company, only to disclose a third one behind. Two companies of the Shropshires were brought up to give weight to the further attack, but already day was breaking and there was no chance of success when once it was light, as all the front trenches were dominated by the mound. This vigorous night action ended, therefore, by leaving the mound itself and the front trench in the hands of the Germans, who had been pushed back from all the other trenches and the portion of the village which they had been able to occupy in the first rush of their attack. The losses of the British amounted to 40 officers and 680 men—killed, wounded, and missing, about 100 coming under the last category, {33} who represent the men destroyed by the explosion. The German losses were certainly not less, but it must be admitted that the mound, as representing the trophy of victory, remained in their hands. In the morning of the 15th the Germans endeavoured to turn the Leinsters out of the trench which they had recaptured, but their attack was blown back, and they left 34 dead in front of the position.

It is pleasing in this most barbarous of all wars to be able to record that all German troops did not debase themselves to the degraded standards of Prussia. Upon this occasion the Bavarian general in charge consented at once to a mutual gathering in of the wounded and a burying of the dead—things which have been a matter of course in all civilised warfare until the disciples of Kultur embarked upon their campaign. It is also to be remarked that in this section of the field a further amenity can be noted, for twice messages were dropped within the British lines containing news as to missing aviators who had been brought down by the German guns. It was hoped for a time that the struggle, however stern, was at last about to conform to the usual practices of humanity—a hope which was destined to be wrecked for ever upon that crowning abomination, the poisoning of Langemarck.

A month of comparative quiet succeeded the battle of Neuve Chapelle, the Germans settling down into their new position and making no attempt to regain their old ones. Both sides were exhausted, though in the case of the Allies the exhaustion was rather in munitions than in men. The regiments were kept well supplied from the depots, and the brutality of the German methods of warfare {34} ensured a steady supply of spirited recruits. That which was meant to cow had in reality the effect of stimulating. It is well that this was so, for so insatiable are the demands of modern warfare that already after eight months the whole of the regiments of the original expeditionary force would have absolutely disappeared but for the frequent replenishments, which were admirably supplied by the central authorities. They had been far more than annihilated, for many of the veteran corps had lost from one and a half times to twice their numbers. The 1st Hants at this date had lost 2700 out of an original force of 1200 men, and its case was by no means an exceptional one. Even in times of quiet there was a continual toll exacted by snipers, bombers, and shells along the front which ran into thousands of casualties per week. The off-days of Flanders were more murderous than the engagements of South Africa. Now and then a man of note was taken from the Army in this chronic and useless warfare. The death of General Gough, of the staff of the First Army, has already been recorded. Colonel Farquhar, of the Princess Patricia Canadians, lost his life in a similar fashion. The stray shell or the lurking sniper exacted a continual toll, General Maude of the 14th Brigade, Major Leslie Oldham, one of the heroes of Chitral, and other valuable officers being killed or wounded in this manner.

Battle of Hill 60.

On April 17 there began a contest which was destined to rage with great fury, though at intermittent intervals, for several weeks. This was the fight for Hill 60. Hill 60 was a low ridge about fifty feet high and two hundred and fifty yards from end to end, which faced the Allied trenches in the Zillebeke region to the south-east of Ypres. This portion of {35} the line had been recently taken over by Smith-Dorrien's Army from the French, and one of the first tasks which the British had set themselves was to regain the hill, which was of considerable strategic importance, because by their possession of it the Germans were able to establish an observation post and direct the fire of their guns towards any portion of the British line which seemed to be vulnerable. With the hill in British hands it would be possible to move troops from point to point without their being overseen and subjected to fire. Therefore the British had directed their mines towards the hill, and ran six underneath it, each of them ending in a chamber which contained a ton of gunpowder. This work, begun by Lieutenant Burnyeat and a hundred miners of the Monmouth battalions, was very difficult owing to the wet soil. It was charged by Major Norton Griffiths and the 171st Mining Company Royal Engineers. At seven in the evening of Saturday, April 17, the whole was exploded with terrific effect. Before the smoke had cleared away the British infantry had dashed from their trench and the hill was occupied. A handful of dazed Germans were taken prisoners and 150 were buried under the debris.

Storming of the Hill.

The storming party was drawn from two battalions of the veteran 13th Brigade, and the Brigadier Wanless O'Gowan was in general control of the operations under General Morland, of the Fifth Division. The two battalions immediately concerned were the 1st Royal West Kents and the 2nd Scottish Borderers. Major Joslin, of the Kents, led the assault, and C Company of that regiment, under Captain Moulton Barrett, was actually the first to reach the crest while {36} it was still reeking and heaving from the immense explosion. Sappers of the 2nd Home Counties Company raced up with the infantry, bearing sandbags and entrenching tools to make good the ground, while a ponderous backing of artillery searched on every side to break up the inevitable counter-attack. There was desperate digging upon the hill to raise some cover, and especially to cut back communication trenches to the rear. Without an over-crowding which would have been dangerous under artillery fire, there was only room for one company upon the very crest. The rest were in supporting trenches immediately behind. By half-past one in the morning of the 18th the troops were dug in, but the Germans, after a lull which followed the shock, were already thickening for the attack. Their trenches came up to the base of the hill, and many of their snipers and bomb-throwers hid themselves amid the darkness in the numerous deep holes with which the whole hill was pocked. Showers of bombs fell upon the British line, which held on as best it might.

At 3.30 A.M. the Scots Borderers pushed forward to take over the advanced fire trench from the Kents, who had suffered severely. This exchange was an expensive one, as several officers, including Major Joslin, the leader of the assault, Colonel Sladen, and Captains Dering and Burnett, were killed or wounded, and in the confusion the Germans were able to get more of their bombers thrown forward, making the front trench hardly tenable. The British losses up to this time had almost entirely arisen from these bombs, and two attempts at regular counter-attacks had been nipped in the bud by the artillery fire, aided by motor machine-guns. As the sky was beginning to whiten {37} in the east, however, there was a more formidable advance, supported by heavy and incessant bombing, so that at half-past five the 2nd West Ridings were sent forward, supported by the 1st Bedfords from the 15th Brigade. A desperate fight ensued. In the cold of the morning, with bomb and bayonet men stood up to each other at close quarters, neither side flinching from the slaughter. By seven o'clock the Germans had got a grip of part of the hill crest, while the weary Yorkshiremen, supported by their fellow-countrymen of the 2nd Yorkshire Light Infantry, were hanging on to the broken ground and the edge of the mine craters. From then onwards the day was spent by the Germans in strengthening their hold, and by the British in preparing for a renewed assault. This second assault, more formidable than the first, since it was undertaken against an expectant enemy, was fixed for six o'clock in the evening.

At the signal five companies of infantry, three from the West Ridings and two from the Yorkshire Light Infantry, rushed to the front. The losses of the storming party were heavy, but nothing could stop them. Of C Company of the West Ridings only Captain Barton and eleven men were left out of a hundred, but none the less they carried the point at which their charge was aimed. D Company lost all its officers, but the men carried on. After a fierce struggle the Germans were ejected once again, and the whole crest held by the British. The losses had been very heavy, the various craters formed by the mines and the heavy shells being desperately fought for by either party. It was about seven o'clock on the evening of the 18th that the Yorkshiremen of {38} both regiments drew together in the dusk and made an organised charge across the whole length of the hill, sweeping it clear from end to end, while the 59th Company Royal Engineers helped in making good the ground. It was a desperate tussle, in which men charged each other like bulls, drove their bayonets through each other, and hurled bombs at a range of a few yards into each other's faces. Seldom in the war has there been more furious fighting, and in the whole Army it would have been difficult to find better men for such work than the units engaged.

From early morning of that day till late at night the Brigadier-General O'Gowan was in the closest touch with the fighting line, feeding it, binding it, supporting it, thickening it, until he brought it through to victory. His Staff-Captain Egerton was killed at his side, and he had several narrow escapes. The losses were heavy and the men exhausted, but the German defence was for the time completely broken, and the British took advantage of the lull to push fresh men into the advanced trenches and withdraw the tired soldiers. This was done about midnight on the 18th, and the fight from then onwards was under the direction of General Northey, who had under him the 1st East Surrey, the 1st Bedfords, and the 9th London (Queen Victoria) Rifles. Already in this murderous action the British casualties had been 50 officers and 1500 men, who lay, with as many of the Germans, within a space no larger than a moderate meadow.

During the whole of the daylight hours of April 19 a furious bombardment was directed upon the hill, on and behind which the defenders were crouching. Officers of experience described this concentration {39} of fire as the worst that they had ever experienced. Colonel Griffith of the Bedfords held grimly to his front trench, but the losses continued to be heavy. During that afternoon a new phenomenon was observed for and the first time—an indication of what was to come. Officers seated in a dug-out immediately behind the fighting line experienced a strong feeling of suffocation, and were driven from their shelter, the candles in which were extinguished by the noxious air. Shells bursting on the hill set the troops coughing and gasping. It was the first German experiment in the use of poison—an expedient which is the most cowardly in the history of warfare, reducing their army from being honourable soldiers to the level of assassins, even as the sailors of their submarines had been made the agents for the cold-blooded murder of helpless civilians. Attacked by this new agent, the troops still held their ground.

Desperate fighting.

Tuesday, April 20, was another day of furious shell-fire. A single shell upon that morning blew in a parapet and buried Lieutenant Watson with twenty men of the Surreys. The Queen Victorias under Colonel Shipley upheld the rising reputation of the Territorial troops by their admirable steadiness. Major Lees, Lieutenant Summerhays, and many others died an heroic death; but there was no flinching from that trench which was so often a grave. As already explained, there was only one trench and room for a very limited number of men on the actual crest, while the rest were kept just behind the curve, so as to avoid a second Spion Kop. At one time upon this eventful day a handful of London Territorials under a boy officer, Woolley of the Victorias, were the only troops upon the top, but it was in safe keeping none the less. {40} This officer received the Victoria Cross. Hour after hour the deadly bombardment went on. About 7.30 in the evening the bombers of the enemy got into some folds in the ground within twenty yards and began a most harassing attack. All night, under the sudden glare of star shells, there were a succession of assaults which tried the half-stupefied troops to the utmost. Soon after midnight in the early morning of Wednesday, April 21, the report came in to the Brigadier that the 1st Surreys in the trenches to the left had lost all their officers except one subaltern. As a matter of fact, every man in one detachment had been killed or wounded by the grenades. It was rumoured that the company was falling back, but on a message reaching them based upon this supposition, the answer was, "We have not budged a yard, and have no intention of doing so." At 2.30 in the morning the position seemed very precarious, so fierce was the assault and so worn the defence. Of A Company of the Surreys only 55 privates were left out of 180, while of the five officers none were now standing, Major Paterson and Captain Wynyard being killed, while Lieutenant Roupell, who got the Cross, and two others were wounded. It was really a subalterns' battle, and splendidly the boys played up.

All the long night trench-mortars and mine-throwers played upon them, while monstrous explosions flung shattered khaki figures amid a red glare into the drifting clouds of smoke, but still the hill was British. With daylight the 1st Devons were brought up into the fight, and an hour later the hill was clear of the enemy once more, save for a handful of snipers concealed in the craters of the north-west corner. In vain the Germans tried to win back a foothold. Nothing {41} could shift that tenacious infantry. Field-guns were brought up by the attackers and fired at short range at the parapets hastily thrown up, but the Devons lay flat and held tight. It had been a grand fight. Heavy as were the strokes of the Thor hammer of Germany, they had sometimes bent but never shattered the iron line of Britain. Already the death-roll had been doubled, and 100 officers with 3000 of our men were stretched upon that little space, littered with bodies and red with blood from end to end. But now the action was at last drawing to its close. Five days it had raged with hardly a break. British guns were now run up and drove the German ones to cover. Bombers who still lurked in the craters were routed out with the bayonet. In the afternoon of the 21st the fire died gradually away and the assaults came to an end. Hill 60 remained with the British. The weary survivors were relieved, and limped back singing ragtime music to their rest-camps in the rear, while the 2nd Cameron Highlanders, under Colonel Campbell, took over the gruesome trenches.

It was a fine feat of arms for which the various brigadiers, with General Morland of the Fifth Division, should have the credit. It was not a question of the little mound—important as that might be, it could not justify so excessive a loss of life, whether German or British. Hill 60 was a secondary matter. What was really being fought for was the ascendancy of the British or the Prussian soldier—that subtle thing which would tinge every battle which might be fought thereafter. Who would cry "Enough!" first? Who would stick it to the bitter end? Which had the staying-power when tried out to a finish? The answer to that question was of more definite military {42} importance than an observation post, and it was worth our three thousand slain or maimed to have the award of the God of battles to strengthen us hereafter.

This description may well be ended by the general order in which Sir John French acknowledged the services of the troops engaged in this arduous affair:

"I congratulate you and the troops of the Second Army on your brilliant capture and retention of the important position at Hill 60. Great credit is due to Lieutenant-General Sir Charles Ferguson, commanding Second Corps; Major-General Morland, commanding Fifth Division; Brigadier-General Wanless O'Gowan, commanding 13th Brigade; and Brigadier-General Northey, commanding 15th Brigade, for their energy and skill in carrying out the operations. I wish particularly to express my warmest admiration for the splendid dash and spirit displayed by the battalions of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Brigades which took part under their respective commanding officers. This has been shown in the first seizure of the position, by the fire attack of the Royal West Kents and the King's Own Scottish Borderers, and in the heroic tenacity with which the hill has been held by the other battalions of these brigades against the most violent counter-attacks and terrific artillery bombardment. I also must commend the skilful work of the Mining Company R.E., of the 59th Field Company R.E., and 2nd Home Counties Field Company R.E., and of the Artillery. I fully recognise the skill and foresight of Major-General Bulfin, commanding Twenty-eighth Division, and his C.R.E., Colonel Jerome, who are responsible for the original conception and plan of the undertaking."

It will be noticed that in his generous commendation Sir John French quotes the different separate units of Engineers as a token of his appreciation of the heavy work which fell upon them before as well as during the battle. Many anecdotes were current in the Army as to the extraordinary daring and energy of the subterranean workers, who were never so happy as when, deep in the bowels of the earth, they were planning some counter-mine with the tapping of the German picks growing louder on their ears. One authentic deed by Captain Johnston's 172nd Mining Company may well be placed upon record. The sapping upon this occasion was directed against the Peckham Farm held by the Germans. Finding that the enemy were countermining, a camouflet was laid down which destroyed their tunnel. After an interval a corporal descended into the shaft, but was poisoned by the fumes. An officer followed him and seized him by the ankles, but became unconscious. A private came next and grabbed the officer, but lost his own senses. Seven men in succession were in turn rescuers and rescued, until the whole chain was at last brought to the surface. Lieutenants Severne and Williams, with Corporal Gray and Sappers Hattersley, Hayes, Lannon, and Smith, were the heroes of this incident. It is pleasant to add that though the corporal died, the six others were all resuscitated.

A military crime.

It is with a feeling of loathing that the chronicler turns from such knightly deeds as these to narrate the next episode of the war, in which the gallant profession of arms was degraded to the level of the assassin, and the Germans, foiled in fair fighting, stole away a few miles of ground by the arts of the murderer. So long as military history is written, the poisoning of {44} Langemarck will be recorded as a loathsome incident by which warfare was degraded to a depth unknown among savages, and a great army, which had long been honoured as the finest fighting force in the world, became in a single day an object of horror and contempt, flying to the bottles of a chemist to make the clearance which all the cannons of Krupp were unable to effect. The crime was no sudden outbreak of spite, nor was it the work of some unscrupulous subordinate. It could only have been effected by long preparation, in which the making of great retorts and wholesale experiments upon animals had their place. Our generals, and even our papers, heard some rumours of such doings, but dismissed them as being an incredible slur upon German honour. It proved now that it was only too true, and that it represented the deliberate, cold-blooded plan of the military leaders. Their lies, which are as much part of their military equipment as their batteries, represented that the British had themselves used such devices in the fighting on Hill 60. Such an assertion may be left to the judgment of the world.

Stage I.—The Gas Attack, April 22-30

Situation at Ypres—The poison gas—The Canadian ordeal—The fight in the wood of St. Julien—The French recovery—Miracle days—The glorious Indians—The Northern Territorials—Hard fighting—The net result—Loss of Hill 60.

It may be remembered that the northern line of the Ypres position, extending from Steenstraate to Langemarck, with Pilken somewhat to the south of the centre, had been established and held by the British during the fighting of October 21, 22, and 23. Later, when the pressure upon the British to the east and south became excessive, the French took over this section. The general disposition of the Allies at the 22nd of April was as follows.