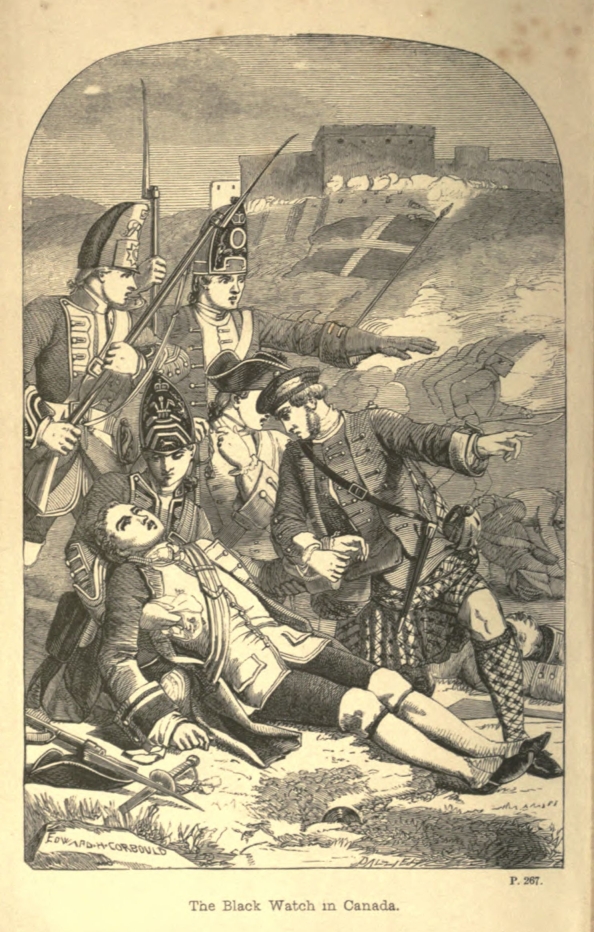

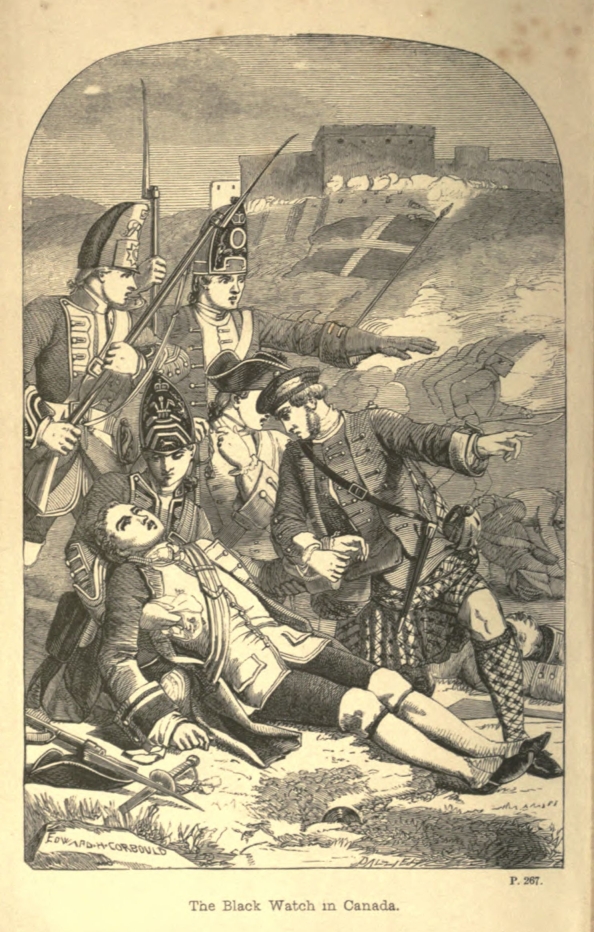

The Black Watch in Canada. P. 267

Title: Legends of the Black Watch; or, Forty-second Highlanders

Author: James Grant

Release date: May 9, 2021 [eBook #65294]

Language: English

Credits: Al Haines

The Black Watch in Canada. P. 267

OR,

Forty-second Highlanders.

BY

JAMES GRANT,

AUTHOR OF

"THE ROMANCE OF WAR," "HOLLYWOOD HALL," ETC., ETC.

NEW EDITION.

LONDON:

ROUTLEDGE, WARNE, AND ROUTLEDGE,

FARRINGDON STREET,

NEW YORK: 66, WALKER STREET.

1860.

[The Author reserves the right of translation.]

LONDON

SAVILL AND EDWARDS, PRINTERS,

CHANDOS STREET.

PREFACE.

Woven up with an occasional legend or superstition gleaned among the mountains from whence its soldiers came, the warlike details and many of the names which occur in the following pages, belong to the military history of the country and of the brave Regiment whose title is given to our Book.

It is generally acknowledged that but for the retention of the kilt in the British service, and for the high character of those regiments who wear it> the military name of Scotland had been long since forgotten in Europe, and her national existence had been as completely ignored during the Wars of Wellington as in those of Marlborough; nor in times more recent had the electric wire announced that, when the cloud of Russian horse came on at Balaclava and our allies fled, "the Scots stood firm."

The kilt alone indicated their country, as our Scots Lowland regiments are clad like the rest of the Line. The martial and picturesque costume of the ancient clans which is now so completely identified with modern Scotland, is one of the few remnants of the past that remain to her; and it is remarkable that it has survived so long; for it was the garb of those adventurous Greeks who fought under Xenophon, and of those hardy warriors who spread the terror of the Roman name from the shores of the Euphrates on the east, to those of the Caledonian Firths upon the west.

It was the best public service of the great Pitt when he first rallied round the British throne, as soldiers of the Highland Regiments, the men of that warlike race, who had been so long inimical to the House of Hanover.

"I sought for merit wherever it was to be found," said he; "it is my boast that I was the first minister who looked for it and found it on the mountains of the north. I called it forth, and drew into your service a hardy and intrepid race of men, who, when left by your jealousy, became a prey to the artifice of your enemies, and who, in the war before the last, had well nigh gone to have overturned the State. These men in the last war were brought to combat by your side; they served with fidelity as they fought with honour, and conquered for you in every part of the world."

Highlander and Lowlander are now so mingled by intermarriage that there is scarcely a subject in the northern kingdom without more or less Celtic blood in his or her veins; and to this mixture of race, which unites the fire and impatience of the former to the steady perseverance of the latter, Scotland owes her present prosperity.

The Clans are passing away, and with them a thousand great and glorious historical and romantic associations; while, by the rapid spread of education, even their language cannot long survive; "but when time shall have drawn its veil over the past as over the present—when the last broadsword shall have been broken on the anvil, and the shreds of the last plaid tossed to the winds upon the cairn, or been bleached within the raven's nest, posterity may look back with regret to a people who have so marked the history, the poetry, and the achievements of a distant age;" and who, in the ranks of the British army, have stood foremost in the line of battle and given place to none!

20, DANUBE STREET, EDINBURGH,

October, 1859.

CONTENTS.

III. THE LOST REGIMENT—A LOVE STORY

IV. MASSACRE AT FORT WILLIAM HENRY

V. THE WIFE OF THE RED COMYN—MY GRANDFATHER'S STORY

VI. STORY OF THE GREY MOUSQUETAIRE—A FRAGMENT OF THE SEVEN YEARS' WAR

VII. THE LETTRE DE CACHET

VIII. THE ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN GRANT

X. THE FOREST OF GAICH—OR THE CAPTAIN DHU

LEGENDS

OF

THE BLACK WATCH,

This soldier, whose name, from the circumstances connected with his remarkable story, daring courage, and terrible fate, is still remembered in the regiment, in the early history of which he bears so prominent a part, was one of the first who enlisted in Captain Campbell of Finab's independent band of the Reicudan Dhu, or Black Watch, when the six separate companies composing this Highland force were established along the Highland Border in 1729, to repress the predatory spirit of certain tribes, and to prevent the levy of black mail. The companies were independent, and at that time wore the clan tartan of their captains, who were Simon Frazer, the celebrated Lord Lovat; Sir Duncan Campbell of Lochnell; Grant of Ballindalloch; Alister Campbell of Finab, whose father fought at Darien; Ian Campbell of Carrick, and Deors Monro of Culcairn.

The privates of these companies were all men of a superior station, being mostly cadets of good families—gentlemen of the old Celtic and patriarchal lines; and of baronial proprietors. In the Highlands, the only genuine mark of aristocracy was descent from the founder of the tribe; all who claimed this were styled uislain, or gentlemen, and, as such, when off duty, were deemed the equal of the highest chief in the land. Great care was taken by the six captains to secure men of undoubted courage, of good stature, stately deportment, and handsome figure. Thus, in all the old Highland regiments, but more especially the Reicudan Dhu, equality of blood and similarity of descent, secured familiarity and regard between the officers and their men—for the latter deemed themselves inferior to no man who breathed the air of heaven. Hence, according to an English engineer officer, who frequently saw these independent companies, "many of those private gentlemen-soldiers have gillies or servants to attend upon them in their quarters, and upon a march, to carry their provisions, baggage, and firelocks."

Such was the composition of the corps, now first embodied among that remarkable people, the Scottish Highlanders—"a people," says the Historian of Great Britain, "untouched by the Roman or Saxon invasions on the south, and by those of the Danes on the east and west skirts of their country—the unmixed remains of that vast Celtic empire, which once stretched from the Pillars of Hercules to Archangel."

The Reicudan Dhu were armed with the usual weapons and accoutrements of the line; but, in addition to these, had the arms of their native country—the broadsword, target, pistol, and long dagger, while the sergeants carried the old Celtic tuagh, or Lochaber axe. It was distinctly understood by all who enlisted in this new force, that their military duties were to be confined within the Highland Border, where, from the wild, predatory spirit of those clans which dwelt next the Lowlands, it was known that they would find more than enough of military service of the most harassing kind. In the conflicts which daily ensued among the mountains—in the sudden marches by night; the desperate brawls among Caterans, who were armed to the teeth, fierce as nature and outlawry could make them, and who dwelt in wild and pathless fastnesses secluded amid rocks, woods, and morasses, there were few who in courage, energy, daring, and activity equalled Farquhar Shaw, a gentleman from the Braes of Lochaber, who was esteemed the premier private in the company of Campbell of Finab, which was then quartered in that district; for each company had its permanent cantonment and scene of operations during the eleven years which succeeded the first formation of the Reicudan Dhu.

Farquhar was a perfect swordsman, and deadly shot alike with the musket and pistol; and his strength was such, that he had been known to twist a horse-shoe, and drive his skene dhu to the hilt in a pine log; while his activity and power of enduring hunger, thirst, heat, cold and fatigue, became a proverb among the companies of the Watch: for thus had he been reared and trained by his father, a genuine old Celtic gentleman and warrior, whose memory went back to the days when Dundee led the valiant and true to the field of Rinrory, and in whose arms the viscount fell from his horse in the moment of victory, and was borne to the house of Urrard to die. He was a true Highlander of the old school; for an old school has existed in all ages and everywhere, even among the Arabs, the children of Ishmael, in the desert; for they, too, have an olden time to which they look back with regret, as being nobler, better, braver, and purer than the present. Thus, the father of Farquhar Shaw was a grim duinewissal, who never broke bread or saw the sun rise without uncovering his head and invoking the names of "God, the Blessed Mary, and St. Colme of the Isle;" who never sat down to a meal without opening wide his gates, that the poor and needy might enter freely; who never refused the use of his purse and sword to a friend or kinsman, and was never seen unarmed, even in his own dining-room; who never wronged any man; but who never suffered a wrong or affront to pass, without sharp and speedy vengeance; and who, rather than acknowledge the supremacy of the House of Hanover, died sword in hand at the rising in Glensheil. For this act, his estates were seized by the House of Breadalbane, and his only son, Farquhar, became a private soldier in the ranks of the Black Watch.

It may easily be supposed, that the son of such a father was imbued with all his cavalier spirit, his loyalty and enthusiasm, and that his mind was filled by all the military, legendary, and romantic memories of his native mountains, the land of the Celts, which, as a fine Irish ballad says, was THEIRS

Ere the Roman or the Saxon, the Norman or the Dane,

Had first set foot in Britain, or trampled heaps of slain,

Whose manhood saw the Druid rite, at forest tree and rock—

And savage tribes of Britain round the shrines of Zernebok;

Which for generations witnessed all the glories of the Gael,

Since their Celtic sires sang war-songs round the sacred fires of Baal.

When it was resolved by Government to form the six independent Highland companies into one regiment, Farquhar Shaw was left on the sick list at the cottage of a widow, named Mhona Cameron, near Inverlochy, having been wounded in a skirmish with Caterans in Glennevis, and he writhed on his sickbed when his comrades, under Finab, marched for the Birks of Aberfeldy, the muster-place of the whole, where the companies were to be united into one battalion, under the celebrated John Earl of Crawford and Lindesay, the last of his ancient race, a hero covered with wounds and honours won in the services of Britain and Russia.

Weak, wan, and wasted though he was (for his wound, a slash from a pole-axe, had been a severe one), Farquhar almost sprang from bed when he heard the notes of their retiring pipes dying away, as they marched through Maryburgh, and round by the margin of Lochiel. His spirit of honour was ruffled, moreover, by a rumour, spread by his enemies the Caterans, against whom he had fought repeatedly, that he was growing faint-hearted at the prospect of the service of the Black Watch being extended beyond the Highland Border. As rumours to this effect were already finding credence in the glens, the fierce, proud heart of Farquhar burned within him with indignation and unmerited shame.

At last, one night, an old crone, who came stealthily to the cottage in which he was residing, informed him that, by the same outlaws who were seeking to deprive him of his honour, a subtle plan had been laid to surround his temporary dwelling, and put him to death, in revenge for certain wounds inflicted by his sword upon their comrades.

The energy and activity of the Black Watch had long since driven the Caterans to despair, and nothing but the anticipation of killing Farqnhar comfortably, and chopping him into ounce pieces at leisure, enabled them to survive their troubles with anything like Christian fortitude and resignation.

"And this is their plan, mother?" said Farquhar to the crone.

"To burn the cottage, and you with it."

"Dioul! say you so, Mother Mhona," he exclaimed; "then 'tis time I were betaking me to the hills. Better have a cool bed for a few nights on the sweet-scented heather, than be roasted in a burning cottage, like a fox in its hole."

In vain the cotters besought him to seek concealment elsewhere; or to tarry until he had gained his fall strength.

"Were I in the prime of strength, I would stay here," said Farquhar; "and when sleeping on my sword and target, would fear nothing. If these dogs of Caterans came, they should be welcome to my life, if I could not redeem it by the three best lives in their band; but I am weak as a growing boy, and so shall be off to the free mountain side, and seek the path that leads to the Birks of Aberfeldy."

"But the Birks are far from here, Farquhar," urged old Mhona.

"Attempt, and Did-not, were the worst of Fingal's hounds," replied the soldier. "Farquhar will owe you a day in harvest for all your kindness; but his comrades wait, and go he must! Would it not be a strange thing and a shameful, too, if all the Reicudan Dhu should march down into the flat, bare land of the Lowland clowns, and Farquhar not be with them? What would Finab, his captain, think? and what would all in Brae Lochaber say?"

"Yet pause," continued the crones.

"Pause! Dhia! my father's bones will soon be clattering in their grave, far away in green Glensheil, where he died for King James, Mhona."

"Beware," continued the old woman, "lest you go for ever, Farquhar."

"It is longer to for ever than to Beltane, and by that day I must be at the Birks of Aberfeldy."

Then, seeing that he was determined, the crones muttered among themselves that the tarvecoill would fall upon him; but Farquhar Shaw, though far from being free of his native superstitions, laughed aloud; for the tarvecoill is a black cloud, which, if seen on a new-year's eve, is said to portend stormy weather; hence it is a proverb for a misfortune about to happen.

"You were unwise to become a soldier, Farquhar," was their last argument.

"Why?"

"The tongue may tie a knot which the teeth cannot untie."

"As your husbands' tongues did, when they married you all, poor men!" was the good-natured retort of Farquhar. "But fear not for me; ere the snow begins to melt on Ben Nevis, and the sweet wallflower to bloom on the black Castle of Inverlochy, I will be with you all again," he added, while belting his tartan-plaid about him, slinging his target on his shoulder, and whistling upon Bran, his favourite stag-hound; he then set out to join the regiment, by the nearest route, on the skirts of Ben Nevis, resolving to pass the head of Lochlevin, through Larochmohr, and the deep glens that lead towards the Braes of Rannoch, a long, desolate, and perilous journey, but with his sword, his pistols, and gigantic hound to guard him, his plaid for a covering, and the purple heather for a bed wherever he halted, Farquhar feared nothing.

His faithful dog Bran, which had shared his couch and plaid since the time when it was a puppy, was a noble specimen of the Scottish hound, which was used of old in the chase of the white bull, the wolf, and the deer, and which is in reality the progenitor of the common greyhound; for the breed has degenerated in warmer climates than the stern north. Bran (so named from Bran of old) was of such size, strength, and courage, that he was able to drag down the strongest deer; and, in the last encounter with the Caterans of Glen Nevis, he had saved the life of Farquhar, by tearing almost to pieces one who would have slain him, as he lay wounded on the field. His hair was rough and grey; his limbs were muscular and wiry; his chest was broad and deep; his keen eyes were bright as those of an eagle. Such dogs as Bran bear a prominent place in Highland song and story. They were remarkable for their sagacity and love of their master, and their solemn and dirge-like howl was ever deemed ominous and predictive of death and woe.

Bran and his master were inseparable. The noble dog had long been invaluable to him when on hunting expeditions, and now since he had become a soldier in the Reicudan Dhu, Bran was always on guard with him, and the sharer of all his duties; thus Farquhar was wont to assert, "that for watchfulness on sentry, Bran's two ears were worth all the rest in the Black Watch put together."

The sun had set before Farquhar left the green thatched clachan, and already the bases of the purple mountains were dark, though a red glow lingered on their heath-clad summits. Lest some of the Cateran band, of whose malevolence he was now the object, might already have knowledge or suspicion of his departure and be watching him with lynx-like eyes from behind some rock or bracken bush, he pursued for a time a path which led to the westward, until the darkness closed completely in; and then, after casting round him a rapid and searching glance, he struck at once into the old secluded drove-way or Fingalian road, which descended through the deep gorge of Corriehoilzie towards the mouth of Glencoe.

On his left towered Ben Nevis—or "the Mountain of Heaven"—sublime and vast, four thousand three hundred feet and more in height, with its pale summits gleaming in the starlight, under a coating of eternal snow. On his right lay deep glens yawning between pathless mountains that arose in piles above each other, their sides torn and rent by a thousand water-courses, exhibiting rugged banks of rock and gravel, fringed by green waving bracken leaves and black whin bushes, or jagged by masses of stone, lying in piles and heaps, like the black, dreary, and Cyclopean ruins "of an earlier world." Before him lay the wilderness of Larochmohr, a scene of solitary and solemn grandeur, where, under the starlight, every feature of the landscape, every waving bush, or silver birch; every bare scalp of porphyry, and every granite block torn by storms from the cliffs above; every rugged watercourse, tearing in foam through its deep marl bed between the tufted heather, seemed shadowy, unearthly, and weird—dark and mysterious; and all combined, were more than enough to impress with solemnity the thoughts of any man, but more especially those of a Highlander; for the savage grandeur and solitude of that district at such an hour—the gloaming—were alike, to use a paradox, soothing and terrific.

There was no moon. Large masses of crape-like vapour sailed across the blue sky, and by gradually veiling the stars, made yet darker the gloomy path which Farquhar had to traverse. Even the dog Bran seemed impressed by the unbroken stillness, and trotted close as a shadow by the bare legs of his master.

For a time Farquhar Shaw had thought only of the bloodthirsty Caterans, who in their mood of vengeance at the Black Watch in general, and at him in particular, would have hewn him to pieces without mercy; but now as the distance increased between himself and their haunts by the shores of the Lochy and Eil, other thoughts arose in his mind, which gradually became a prey to the superstition incident alike to his age and country, as all the wild tales he had heard of that sequestered district, and indeed of that identical glen which he was then traversing, crowded upon his memory, until he, Farquhar Shaw, who would have faced any six men sword in hand, or would have charged a grape-shotted battery without fear, actually sighed with apprehension at the waving of a hazel bush on the lone hill side.

Of many wild and terrible things this locale was alleged to be the scene, and with some of these the Highland reader may be as familiar as Farquhar.

A party of the Black Watch in the summer of 1738, had marched up the glen, under the command of Corporal Malcolm MacPherson (of whom more anon), with orders to seize a flock of sheep and arrest the proprietor, who was alleged to have "lifted" (i.e., stolen) them from the Camerons of Lochiel. The soldiers found the flock to the number of three hundred, grazing on a hill side, all fat black-faced sheep with fine long wool, and seated near them, crook in hand, upon a fragment of rock, they found the person (one of the Caterans already referred to) who was alleged to have stolen them. He was a strange-looking old fellow, with a long white beard that flowed below his girdle; he was attended by two huge black dogs of fierce and repulsive aspect. He laughed scornfully when arrested by the corporal, and hollowly the echoes of his laughter rang among the rocks, while his giant hounds bayed and erected their bristles, and their eyes flashed as if emitting sparks of fire.

The soldiers now surrounded the sheep and drove them down the hill side into the glen, from whence they proceeded towards Maryburgh, with a piper playing in front of the flock, for it is known that sheep will readily follow the music of the pipe. The Black Watch were merry with their easy capture, but none in MacPherson's party were so merry as the captured shepherd, whom, for security, the corporal had fettered to the left hand of his brother Samuel; and in this order they proceeded for three miles, until they reached a running stream; when, lo! the whole of the three hundred fat sheep and the black dogs turned into clods of brown earth; and, with a wild mocking laugh that seemed to pass away on the wind which swept the mountain waste, their shepherd vanished, and no trace of his presence remained but the empty ring of the fetters which dangled from the left wrist of Samuel MacPherson, who felt every hair on his head bristle under his bonnet with terror and affright.

This sombre glen was also the abode of the Daoine Shie, or Good Neighbours, as they are named in the Lowlands; and of this fact the wife of the pay-sergeant of Farquhar's own company could bear terrible evidence. These imps are alleged to have a strange love for abstracting young girls and women great with child, and leaving in their places bundles of dry branches or withered reeds in the resemblance of the person thus abstracted, but to all appearance dead or in a trance; they are also exceeding partial to having their own bantlings nursed by human mothers.

The wife of the sergeant (who was Duncan Campbell of the family of Duncaves) was without children, but was ever longing to possess one, and had drunk of all the holy wells in the neighbourhood without finding herself much benefited thereby. On a summer evening when the twilight was lingering on the hills, she was seated at her cottage door gazing listlessly on the waters of the Eil, which were reddened by the last flush of the west, when suddenly a little man and woman of strange aspect appeared before her—so suddenly that they seemed to have sprung from the ground—and offered her a child to nurse. Her husband, the sergeant, was absent on duty at Dumbarton; the poor lonely woman had no one to consult, or from whom to seek permission, and she at once accepted the charge as one long coveted.

"Take this pot of ointment," said the man, impressively, giving Moina Campbell a box made of shells, "and be careful from time to time to touch the eyelids of our child therewith."

"Accept this purse of money," said the woman, giving her a small bag of green silk; "'tis our payment in advance, and anon we will come again."

The quaint little father and mother then each blew a breath upon the face of the child and disappeared, or as the sergeant's wife said, seemed to melt away into the twilight haze. The money given by the woman was gold and silver; but Moina knew not its value, for the coins were ancient, and bore the head of King Constantine IV. The child was a strange, pale and wan little creature, with keen, bright, and melancholy eyes; its lean freakish hands were almost transparent, and it was ever sad and moaning. Yet in the care of the sergeant's wife it throve bravely, and always after its eyes were touched with the ointment it laughed, crowed, screamed, and exhibited such wild joy that it became almost convulsed.

This occurred so often that Moina felt tempted to apply the ointment to her own eyes, when lo! she perceived a group of the dwarfish Daoine Shie—little men in trunk hose and sugar-loaf hats, and little women in hoop petticoats all of a green colour—dancing round her, and making grimaces and antic gestures to amuse the child, which to her horror she was now convinced was a bantling of the spirits who dwelt in Larochmohr!

What was she to do? To offend or seem to fear them was dangerous, and though she was now daily tormented by seeing these green imps about her, she affected unconsciousness and seemed to observe them not; but prayed in her heart for her husband's speedy return, and to be relieved of her fairy charge, to whom she faithfully performed her trust, for in time the child grew strong and beautiful; and when, again on a twilight eve, the parents came to claim it, the woman wept as it was taken from her, for she had learned to love the little creature, though it belonged neither to heaven nor earth.

Some months after, Moina Campbell, more lonely now than ever, was passing through Larochmohr, when suddenly within the circle of a large green fairy ring, she saw thousands, yea myriads of little imps in green trunk hose and with sugar-loaf hats, dancing and making merry, and amid them were the child she had nursed and its parents also, and in terror and distress she addressed herself to them.

The tiny voices within the charmed circle were hushed in an instant, and all the little men and women became filled with anger. Their little faces grew red, and their little eyes flashed fire.

"How do you see us?" demanded the father of the fairy child, thrusting his little conical hat fiercely over his right eye.

"Did I not nurse your child, my friend?" said Moina, trembling.

"But how do you see us?" screamed a thousand little voices.

Moina trembled, and was silent.

"Oho!" exclaimed all the tiny voices, like a breeze of wind, "she has been using our ointment, the insolent mortal!"

"I can alter that," said one fairy man (who being three feet high was a giant among his fellows), as he blew upward in her face, and in an instant all the green multitude vanished from her sight; she saw only the fairy ring and the green bare sides of the silent glen. Of all the myriads she had seen, not one was visible now.*

* This, and the two legends which follow, were related to me by a Highlander, who asserted, with the utmost good faith, that they happened in Glendochart; but I have since seen an Arabian tale, which somewhat resembles the adventure of the sergeant's wife.

"Fear not, Moina," cried a little voice from the hill side, "for your husband will prosper." It was the fairy child who spoke.

"But his fate will follow him," added another voice, angrily.

Full of fear the poor woman returned to her cottage, from which, to her astonishment, she had been absent ten days and nights; but she saw her husband no more: in the meantime he had embarked for a foreign land, being gazetted to on ensigncy; thus so far the fairy promise of his prospering proved true.*

* His "fate" would seem to have followed him, too; for he was killed at Ticonderoga, when captain-lieutenant of the Black Watch.—See Stewart's Sketches.

Another story flitted through Farquhar's mind, and troubled him quite as much as its predecessors. In a shieling here a friend of his, when hunting, one night sought shelter. Finding a fire already lighted therein he became alarmed, and clambering into the roof sat upon the cross rafters to wait the event, and ere long there entered a little old man two feet in height. His head, hands, and feet were enormously large for the size of his person; his nose was long, crooked, and of a scarlet hue; his eyes brilliant as diamonds, and they glared in the light of the fire. He took from his back a bundle of reeds, and tying them together, proceeded to blow upon them from his huge mouth and distended cheeks, and as he blew, a skin crept over the dry bundle, which gradually began to assume the appearance of a human face and form.

These proceedings were more than the huntsman on his perch above could endure, and filled by dread that the process below might end in a troublesome likeness of himself, he dropped a sixpence into his pistol (for everything evil is proof to lead) and fired straight at the huge head of the spirit or gnome, which vanished with a shriek, tearing away in his wrath and flight the whole of the turf wall on one side of the shieling, which was thus in a moment reduced to ruin.

These memories, and a thousand others of spectral Druids and tall ghastly warriors, through whose thin forms the twinkling stars would shine (but these orbs were hidden now) as they hovered by grey cairns and the grassy graves of old, crowded on the mind of Farquhar; for there were then, and even now are, more ghosts, devils, and hobgoblins in the Scottish Highlands than ever were laid of yore in the Red Sea. Nor need we be surprised at this superstition in the early days of the Black Watch, when Dr. Henry tells us, in 1831, that within the last twenty years, when a couple agreed to marry in Orkney, they went to the Temple of the Moon, which was semicircular, and there, on her knees, the woman solemnly invoked the spirit of Woden!

Farquhar, as he strode on, comforted himself with the reflection that those who are born at night—as his mother had a hundred times told him he had been—never saw spirits; so he took a good dram from his hunting-flask, and belted his plaid tighter about him, after making a sign of the cross three times, as a protection against all the diablerie of the district, but chiefly against a certain malignant fiend or spirit, who was wont to howl at night among the rocks of Larochmohr, to hurl storms of snow into the deep vale of Corriehoilzie, and toss huge blocks of granite into the deep blue waters of Loch Leven. He shouted on Bran, whistled the march of the Black Watch, "to keep his spirits cheery," and pushed on his way up the mountains, while the broad rain drops of a coming tempest plashed heavily in his face.

He looked up to the "Hill of Heaven." The night clouds were gathering round its awful summit, wheeling, eddying, and floating in whirlwinds from the dark chasms of rock that yawn in its sides. The growling of the thunder among the riven peaks of granite overhead announced that a tempest was at hand; but though Farquhar Shaw had come of a brave and adventurous race, and feared nothing earthly, he could not repress a shudder lest the mournful gusts of the rising wind might bear with them the cry of the Tar' Uisc, the terrible Water Bull, or the shrieks of the spirit of the storm!

The lonely man continued to toil up that wilderness till he reached the shoulder of the mountain, where, on his right, opened the black narrow gorge, in the deep bosom of which lay Loch Leven, and, on his left, opened the glens that led towards Loch Treig, the haunt of Damn mohr a Vonalia, or Enchanted Stag, which was alleged to live for ever, and be proof to mortal weapons; and now, like a tornado of the tropics, the storm burst forth in all its fury!

The wind seemed to shriek around the mountain summits and to bellow in the gorges below, while the thunder hurtled across the sky, and the lightning, green and ghastly, flashed about the rocks of Loch Leven, shedding, ever and anon, for an instant, a sudden gleam upon its narrow stripe of water, and on the brawling torrents that roared down the mountain sides, and were swelling fast to floods, as the rain, which had long been falling on the frozen summit of Ben Nevis, now descended in a broad and blinding torrent that was swept by the stormy wind over hill and over valley. As Farquhar staggered on, a gleam of lightning revealed to him a little turf shieling under the brow of a pine-covered rock, and making a vigorous effort to withstand the roaring wind, which tore over the bare waste with all the force and might of a solid and palpable body, he reached it on his hands and knees. After securing the rude door, which was composed of three cross bars, he flung himself on the earthen floor of the hut, breathless and exhausted, while Bran, his dog, as if awed by the elemental war without, crept close beside him.

As Farquhar's thoughts reverted to all that he had heard of the district, he felt all a Highlander's native horror of remaining in the dark in a place so weird and wild; and on finding near him a quantity of dry wood—bog-pine and oak, stored up, doubtless, by some thrifty and provident shepherd—he produced his flint and tinder-box, struck a light, and, with all the readiness of a soldier and huntsman, kindled a fire in a corner of the shieling, being determined that if it was the place where, about "the hour when churchyards yawn and graves give up their dead," the brownies were alleged to assemble, they should not come upon him unseen or unawares.

Having a venison steak in his havresack, he placed it on the embers to broil, heaped fresh fuel on his fire, and drawing his plaid round Bran and himself, wearied by the toil of his journey on foot in such a night, and over such a country, he gradually dropped asleep, heedless alike of the storm which raved and bellowed in the dark glens below, and round the bare scalps of the vast mountain whose mighty shadows, when falling eastward at eve, darken even the Great Glen of Albyn.

In his sleep, the thoughts of Farquhar Shaw wandered to his comrades, then at the Birks of Aberfeldy. He dreamt that a long time—how long he knew not—had elapsed since he had been in their ranks; but he saw the Laird of Finab, his captain, surveying him with a gloomy brow, while the faces of friends and comrades were averted from him.

"Why is this—how is this?" he demanded.

Then he was told that the Reicudan Dhu were disgraced by the desertion of three of its soldiers, who, on that day, were to die, and the regiment was paraded to witness their fate. The scene with all its solemnity and all its terrors grew vividly before him; he heard the lamenting wail of the pipe as the three doomed men marched slowly past, each behind his black coffin, and the scene of this catastrophe was far, far away, he knew not where; but it seemed to be in a strange country, and then the scene, the sights, and the voices of the people, were foreign to him. In the background, above the glittering bayonets and blue bonnets of the Black Watch, rose a lofty castle of foreign aspect, having a square keep or tower, with four turrets, the vanes of which were shining in the early morning sun. In his ears floated the drowsy hum of a vast and increasing multitude.

Farquhar trembled in every limb as the doomed men passed so near him that he could see their breasts heave as they breathed; but their faces were concealed from him, for each had his head muffled in his plaid, according to the old Highland fashion, when imploring mercy or quarter.

Lots were cast with great solemnity for the firing party or executioners, and, to his horror, Farquhar found himself one of the twelve men chosen for this, to every soldier, most obnoxious duty!

When the time came for firing, and the three unfortunates were kneeling opposite, each within his coffin, and each with his head muffled in a plaid, Farquhar mentally resolved to close his eyes and fire at random against the wall of the castle opposite; but some mysterious and irresistible impulse compelled him to look for a moment, and lo! the plaid had fallen from the face of one of the doomed men, and, to his horror, the dreamer beheld himself!

His own face was before him, but ghastly and pale, and his own eyes seemed to be glaring back upon him with affright, while their aspect was wild, sad, and haggard. The musket dropped from his hand, a weakness seemed to overspread his limbs, and writhing in agony at the terrible sight, while a cold perspiration rolled in bead-drops over his clammy brow, the dreamer started, and awoke, when a terrible voice, low but distinct, muttered in his ear—

"Farquhar Shaw, bithidth duil ri fear feachd, ach cha bhi duil ri fear lic!"*

* A man may return from an expedition; but there is no hope that he may return from the grave.—A Gaelic Proverb.

He leaped to his feet with a cry of terror, and found that he was not alone, as a little old woman was crouching near the embers of his fire, while Bran, his eyes glaring, his bristles erect, was growling at her with a fierce angry sound, that rivalled the bellowing of the storm, which still continued to rave without.

The aspect of this hag was strange. In the light of the fire which brightened occasionally as the wind swept through the crannies of the shieling, her eyes glittered, or rather glared like fiery sparks; her nose was hooked and sharp; her mouth like an ugly gash; her hue was livid and pale. Her outward attire was a species of yellow mantle, which enveloped her whole form; and her hands, which played or twisted nervously in the generous warmth of the glowing embers, resembled a bundle of freakish knots, or the talons of an aged bird. She muttered to herself at times, and after turning her terrible red eyes twice or thrice covertly and wickedly towards Farquhar, she suddenly snatched the venison steak from amid the flames, and, with a chuckle of satisfaction, devoured it steaming hot, and covered as it was with burning cinders.

On Farquhar secretly making a sign of the cross, when beholding this strange proceeding, she turned sharply with a savage expression towards him, and rose to her full stature, which was not more than three feet; and he felt, he knew not why, his heart tremble; for his spirit was already perturbed by the effect of his terrible dream, and clutching the steel collar of Bran (who was preparing to spring at this strange visitor, and seemed to like her aspect as little as his master) he said—

"Woman, who are you?"

"A traveller like yourself, perhaps. But who are you?" she asked in a croaking voice.

"Do you know our proverb in Lochaber—

What sent the messengers to hell,

But asking what they knew full well?"

was the reply of Farquhar, as he made a vigorous effort to restrain Bran, whose growls and fury were fast becoming quite appalling; and at this proverb the eyes of the hag seemed to blaze with fresh anger, while her figure became more than ever erect.

"Oich! oich!" grumbled Farquhar, "I would as readily have had the devil as this ugly hag. I have got a shelter, certainly; but with her 'tis out of the cauldron and into the fire. Had she been a brown-eyed lass, to a share of my plaid she had been welcome; but this wrinkled cailloch——down, Bran, down!" he added aloud, as the strong hound strained in his collar, and tasked his master's hand and arm to keep him from springing at the intruder.

"Is this kind or manly of you," she asked, "to keep a wild brute that behaves thus, and to a woman too? Turn him out into the storm; the wind and rain will soon cool his wicked blood."

"Thank you; but in that you must excuse me. Bran and I are as brothers."

"Turn him out, I say," screamed the hag, "or worse may befall him!"

"I shall not turn him out, woman," said Farquhar, firmly, while surveying the stranger with some uneasiness; for, to his startled gaze, she seemed to have grown taller within the last five minutes. "You have a share of our shelter, and you have had all our supper; but to turn out poor Bran—no, no, that would never do."

To this Bran added a roar of rage, and the fear or fury which blazed in the eyes of the woman fully responded to those, of the now infuriated staghound. The glances of each made those of the other more and more fierce.

"Down, Bran; down, I say," said Farquhar. "What the devil hath possessed the dog? I never saw him behave thus before. He must be savage, mother, that you left him none of the savoury venison steak; for all the supper we had was that road-collop from one of MacGillony's brown cattle."

"MacGillony," muttered the hag, spreading her talon-like hands over the embers; "I knew him well."

"You!" exclaimed Farquhar.

"I have said so," she replied with a grin.

"He was a mighty hunter five hundred years ago, who lived and died on the Grampians!"

"And what are five hundred years, to me, who saw the waters of the deluge pour through Corriehoilzie, and subside from the slope of Ben Nevis?"

"This is a very good joke, mother," said poor Farquhar, attempting to laugh, while the hideous old woman, who was so small when he first saw her as to be almost a dwarf, was now, palpably, veritably, and without doubt, nearly a head taller than himself; and watchfully he continued to gaze on her, keeping one hand on his dirk and the other on the collar of Bran, whose growls were louder now than the storm that careered through the rocky glen below.

"Woman!" said Farquhar, boldly, "my mind misgives me—there is something about you that I little like; I have just had a dreadful dream."

"A morning dream, too!" chuckled the hag with an elfish grin.

"So I connect your presence here with it."

"Be it so."

"What may that terrible dream foretell?" pondered Farquhar; "for morning dreams are but warnings and presages unsolved. The blessings of God and all his saints be about me!"

At these words the beldame uttered a loud laugh.

"You are, I presume, a Protestant?" said Farquhar, uneasily.

At this suggestion she laughed louder still, but seemed to grow more and more in stature, till Farquhar became well-nigh sick at heart with astonishment and fear, and began to revolve in his mind the possibility of reaching the door of the shieling and rushing out into the storm, there to commit himself to Providence and the elements. Besides, as her stature grew, her eyes waxed redder and brighter, and her malevolent hilarity increased.

It was a fiend, a demon of the wild, by whom he was now visited and tormented in that sequestered hut.

His heart sank, and as her terrible eyes seemed to glare upon him, and pierce his very soul, a cold perspiration burst over all his person.

"Why do you grasp your dirk, Farquhar—ha! ha!" she asked.

"For the same reason that I hold Bran—to be ready. Am I not one of the King's Reicudan Dhu? But how know you my name?"

"'Tis a trifle to me, who knew MacGillony."

"From whence came you to-night?"

"From the Isle of Wolves," she replied, with a shout of laughter.

"A story as likely as the rest," said Farquhar, "for that isle is in the Western sea, near unto Coll, the country of the Clan Gillian. You must travel fast."

"Those usually do who travel on the skirts of the wind."

"Woman!" exclaimed Farquhar, leaping up with an emotion of terror which he could no longer control, for her stature now overtopped his own, and ere long her hideous head would touch the rafters of the hut; "thou art either a liar or a fiend! which shall I deem thee?"

"Whichever pleases you most," she replied, starting to her feet.

"Bran, to the proof!" cried Farquhar, drawing his dirk, and preparing to let slip the now maddened hound; "at her, Bran, and hold her down. Good, dog—brave dog! oich, he has a slippery handful that grasps an eel by the tail! at her, Bran, for thou art strong as Cuchullin."

Uttering a roar of rage, the savage dog made a wild bound at the hag, who, with a yell of spite and defiance, and with a wondrous activity, by one spring, left the shieling, and dashing the frail door to fragments in her passage, rushed out into the dark and tempestuous night, pursued by the infuriated but baffled Bran—baffled now, though the fleetest hound on the Braes of Lochaber.

They vanished together in the obscurity, while Farquhar gazed from the door breathless and terrified. The storm still howled in the valley, where the darkness was opaque and dense, save when a solitary gleam of lightning flashed on the ghastly rocks and narrow defile of Loch Leven; and the roar of the bellowing wind as it tore through the rocky gorges and deep granite chasms, had in its sound something more than usually terrific. But, hark! other sounds came upon the skirts of that hurrying storm.

The shrieks of a fiend, if they could be termed so;—for they were shrill and high, like cries of pain and laughter mingled. Then came the loud deep baying, with the yells of a dog, as if in rage and pain, while a thousand sparks, like those of a rocket, glittered for a moment in the blackness of the glen below. The heart of Farquhar Shaw seemed to stand still for a time, while, dirk in hand, he continued to peer into the dense obscurity. Again came the cries of Bran, but nearer and nearer now; and in an instant more, the noble hound sprang, with a loud whine, to his master's side, and sank at his feet. It was Bran, the fleet, the strong, the faithful and the brave; but in what a condition! Torn, lacerated, covered with blood and frightful wounds—disembowelled and dying; for the poor animal had only strength to loll out his hot tongue in an attempt to lick his master's hand before he expired.

"Mother Mary," said Farquhar, taking off his bonnet, inspired with horror and religious awe, "keep thy blessed hand over me, for my dog has fought with a demon!" ......

It may be imagined how Farquhar passed the remainder of that morning—sleepless and full of terrible thoughts, for the palpable memory of his dream, and the episode which followed it, were food enough for reflection.

With dawn, the storm subsided. The sun arose in a cloudless sky; the blue mists were wreathed round the brows of Ben Nevis, and a beautiful rainbow seemed to spring from the side of the mountain far beyond the waters of Loch Leven; the dun deer were cropping the wet glistening herbage among the grey rocks; the little birds sang early, and the proud eagle and ferocious gled were soaring towards the rising sun; thus all nature gave promise of a serene summer day.

With his dirk, Farquhar dug a grave for Bran, and lined it with soft and fragrant heather, and there he covered him up and piled a cairn, at which he gave many a sad and backward glance (for it marked where a faithful friend and companion lay) as he ascended the huge mountains of rock, which, on one hand, led to the Uisc Dhu, or Vale of the Black Water, and on the other, by the tremendous steep named the Devil's Staircase, to the mouth of Glencoe.

In due time he reached the regiment at its cantonments on the Birks of Aberfeldy, where the independent companies, for the first time were exercised as a battalion by their Lieutenant-Colonel, Sir Robert Munro of Culcairn, who, six years afterwards, was slain at the battle of Falkirk.

Farquhar's terrible dream and adventure in that Highland wilderness were ever before him, and the events subsequent to the formation of the Black Watch into a battalion, with the excitement produced among its soldiers by an unexpected order to march into England, served to confirm the gloom that preyed upon his spirits.

The story of how the Black Watch were deceived is well known in the Highlands, though it is only one of the many acts of treachery performed in those days by the British Government in their transactions with the people of that country, when seeking to lessen the adherents of the Stuart cause, and ensnare them into regiments for service in distant lands; hence the many dangerous mutinies which occurred after the enrolment of all the old Highland corps.

This unexpected order to march into England caused such a dangerous ferment in the Black Watch, as being a violation of the principles and promise under which it was enrolled, and on which so many Highland gentlemen of good family enlisted in its ranks, that the Lord President Duncan Forbes of Culloden, warned General Clayton, the Scottish Commander-in-Chief, of the evil effects likely to occur if this breach of faith was persisted in; and to prevent the corps from revolting en masse, that officer informed the soldiers that they were to enter England "solely to be seen by King George, who had never seen a Highland soldier, and had been graciously pleased to express, or feel great curiosity on the subject."

Cajoled and flattered by this falsehood, the soldiers of the Reicudan Dhu, all unaware that shipping was ordered to convey them to Flanders, began their march for England, in the end of March, 1743; and if other proof be wanting that they were deluded, the following announcement in the Caledonian Mercury of that year affords it:—

"On Wednesday last, the Lord Sempills Regiment of Highlanders began their march for England, in order to be reviewed by his Majesty."

Everywhere on the march throughout the north of England, they were received with cordiality and hospitality by the people, to whom their garb, aspect, and equipment were a source of interest, and in return, the gentlemen and soldiers of the Reicudan Dhu behaved to the admiration of their officers and of all magistrates; but as they drew nearer to London, according to Major Grose, they were exposed to the malevolent mockery and the national "taunts of the true-bred English clowns, and became gloomy and sullen. Animated even to the humblest private with the feelings of gentlemen," continues this English officer, "they could ill brook the rudeness of boors, nor could they patiently submit to affronts in a country to which they had been called by the invitation of their sovereign."

On the 30th April, the regiment reached London, and on the 14th May was reviewed on Finchley Common, by Marshal Wade, before a vast concourse of spectators; but the King, whom they expected to be present, had sailed from Greenwich for Hanover on the same night they entered the English metropolis. Herein they found themselves deceived; for "the King had told them a lie," and the spark thus kindled was soon fanned into a flame.

After the review at Finchley Common, Farquhar Shaw and Corporal Malcolm MacPherson were drinking in a tavern, when three English gentlemen entered, and seating themselves at the same table, entered into conversation, by praising the regiment, their garb, their country, and saying those compliments which are so apt to win the heart of a Scotchman when far from home; and the glens of the Gael seemed then indeed, far, far away, to the imagination of the simple souls who manned the Black Watch in 1743.

Both Farquhar and the corporal being gentlemen, wore the wing of the eagle in their bonnets, and were well educated, and spoke English with tolerable fluency.

"I would that his Majesty had seen us, however," said the corporal; "we have had a long march south from our own country on a bootless errand."

"Can you possibly be so simple as to believe that the King cared a rush on the subject?" asked a gentleman, with an incredulous smile; for he and his companions, like many others who hovered about these new soldiers, were Jacobites and political incendiaries.

"What mean you, sir?" demanded MacPherson, with surprise.

"Why, you simpleton, that story of the King wishing to see you was all a tale of a tub—a snare."

"A snare!"

"Yea—a pretext of the ministry to lure you to this distance from your own country, and then transport you bodily for life."

"To where?"

"Oh, that matters little—perhaps to the American plantations."

"Or, to Botany Bay," suggested another, maliciously; "but take another jorum of brandy, and fear nothing; wherever you go, it can't well be a worse place than your own country."

"Thanks, gentlemen," replied Farquhar, loftily, while his hands played nervously with his dirk; "we want no more of your brandy."

"Believe me, sirs," resumed their informant and tormentor, "the real object of the ministry is to get as many fighting men, Jacobites and so forth, out of the Highlands as possible. This is merely part of a new system of government."

"Sirs," exclaimed Farquhar, drawing his dirk with an air of gravity and determination which caused his new friends at once to put the table between him and them, "will you swear this upon the dirk?"

"How—why?"

"Upon the Holy Iron—we know no oath more binding," continued the Highlander, with an expression of quiet entreaty.

"I'll swear it by the Holy Poker, or anything you please," replied the Englishman, re-assured on finding the Celt had no hostile intentions. "'Tis all a fact," he continued, winking to his companions, "for so my good friend Phil Yorke, the Lord Chancellor, who expects soon to be Earl of Hardwick, informed me."

The eyes of the corporal flashed with indignation; and Farquhar struck his forehead as the memory of his terrible dream in the haunted glen rushed upon his memory.

"Oh! yes," said a third gentleman, anxious to add his mite to the growing mischief; "it is all a Whig plot of which you are the victims, as our kind ministry hope that you will all die off like sheep with the rot; or like the Marine Corps; or the Invalids, the old 41st, in Jamaica."

"They dare not deceive us!" exclaimed MacPherson, striking the basket-hilt of his claymore

"Dare not!"

"No."

"Indeed—why?"

"For in the country of the clans fifty thousand claymores would be on the grindstone to avenge us!"

A laugh followed this outburst.

"King George made you rods to scourge your own countrymen, and now, as useless rods, you are to be flung into the fire," said the first speaker, tauntingly.

"By God and Mary!" began MacPherson, again laying a hand on his sword with sombre fury.

"Peace, Malcolm," interposed Farquhar; "the Saxon is right, and we have been fooled. Bithidh gach ni mar is aill Dhiu. (All things must be as God will have them.) Let us seek the Reicudan Dhu, and woe to the Saxon clowns and to that German churl, their King, if they have deceived us!"

On the march back to London, MacPherson and Farquhar Shaw brooded over what they had heard at Finchley; while to other members of the regiment similar communications had been made, and thus, ere nightfall, every soldier of the Black Watch felt assured that he had been entrapped by a royal falsehood, which the sudden, and to them unaccountable, departure of George II. to Hanover seemed beyond all doubt to confirm.

"In those whom he knows," according to General Stewart, "a Highlander will repose perfect confidence, and if they are his superiors will be obedient and respectful; but ere a stranger can obtain this confidence, he must show that he merits it. When once it is given, it is constant and unreserved; but if confidence be lost, no man is more suspicious. Every officer of a Highland regiment, on his first joining the corps, must have observed in his little transactions with the men how minute and strict they are in every item; but when once confidence is established, scrutiny ceases, and his word or nod of assent is as good as his bond. In the case in question (the Black Watch), notwithstanding the arts which were practised to mislead the men, they proceeded to no violence, but believing themselves deceived and betrayed, the only remedy that occurred to them was to get back to their own country."

The memory of the commercial ruin at Darien, and of the massacre at Glencoe (the Cawnpore of King William), were too fresh in every Scottish breast not to make the flame of discontent and mistrust spread like wildfire; and thus, long before the bell of St. Paul's had tolled the hour of midnight, the conviction that he had been BETRAYED was firmly rooted in the mind of every soldier of the Black Watch, and measures to baffle those who had deluded and lured them so far from their native mountains were at once proposed, and as quickly acted upon.

At this crisis, the dream of Farquhar was constantly before him, as a foreboding of the terrors to come, and he strove to thrust it from him; but the words of that terrible warning—a man may return from an expedition, but never from the grave—seemed ever in his ears!

On the night after the review, the whole regiment, except its officers, most of whom knew what was on the tapis, assembled at twelve o'clock on a waste common near Highgate. The whole were in heavy marching order; and by direction of Corporal Malcolm MacPherson, after carefully priming and loading with ball-cartridge, they commenced their march in silence and secresy and with all speed for Scotland—a wild, daring, and romantic attempt, for they were heedless and ignorant of the vast extent of hostile country that lay between them and their homes, and scarcely know the route to pursue. They had now but three common ideas;—to keep together, to resist to the last, and to march north.

With some skill and penetration they avoided the two great highways, and marched by night from wood to wood, concealing themselves by day so well, that for some time no one knew how or where they had gone, though, by the Lords Justices orders had been issued to all officers commanding troops between London and the Scottish Borders to overtake or intercept them; but the 19th May arrived before tidings reached the metropolis that the Black Watch, one thousand strong, had passed Northampton, and a body of Marshal Wade's Horse (now better known as the 3rd or Prince of Wales's Dragoon Guards) overtook them, when faint by forced and rapid marches, by want of food, of sleep and shelter, the unfortunate regiment had entered Ladywood, about four miles from the market town of Oundle-on-the-Nen, and had, as usual, concealed themselves in a spacious thicket, which, by nine o'clock in the evening, was completely environed by strong columns of English cavalry under General Blakeney.

Captain Ball, of Wade's Horse, approached their bivouac in the dusk, bearer of a flag of truce, and was received by the poor fellows with every respect, and Farquhar Shaw, as interpreter for his comrades, heard his demands, which were, "that the whole battalion should lay down its arms, and surrender at discretion as mutineers."

"Hitherto we have conducted ourselves quietly and peacefully in the land of those who have deluded and wronged us, even as they wronged and deluded our forefathers," replied Farquhar; "but it may not be so for one day more. Look upon us, sir; we are famished, worn, and desperate. It would move the heart of a stone to know all we have suffered by hunger and by thirst, even in this land of plenty."

"The remedy is easy," said the captain.

"Name it, sir."

"Submit."

"We have no such word in our mother-tongue, then how shall I translate it to my comrades, so many of whom are gentlemen?"

"That is your affair, not mine. I give you but the terms dictated by General Blakeney."

"Let the general send us a written promise."

"Written?" reiterated the captain, haughtily.

"By his own hand," continued the Highlander, emphatically; "for here in this land of strangers we know not whom to trust when our King has deceived us."

"And to what must the general pledge himself?"

"That our arms shall not be taken away, and that a free pardon be given to all."

"Otherwise——"

"We will rather be cut to pieces."

"This is your decision?"

"It is," replied Farquhar, sternly.

"Be assured it is a rash one."

"I weigh my words, Saxon, ere I speak them. No man among us will betray his comrade; we are all for one and one for all in the ranks of the Reicudan Dhu!"

The captain reported the result of his mission to the general, who, being well aware that the Highlanders had been entrapped by the Government on one hand, and inflamed to revolt by Jacobite emissaries on the other, was humanely willing to temporize with them, and sent the captain to them once more.

"Surrender yourselves prisoners," said Ball; "lay down your arms, and the general will use all his influence in your favour with the Lords Justices."

"We know of no Lords Justices," they replied "We acknowledge no authority but the officers who speak our mother-tongue, and our native chiefs who share our blood. To be without arms, in our country, is in itself to be dishonoured."

"Is this still the resolution of your comrades?" asked Captain Ball.

"It is, on my honour as a gentleman and soldier," replied Farquhar.

The English captain smiled at these words, for he knew not the men with whom he had to deal.

"Hitherto, my comrade," said he, "I have been your friend, and the friend of the regiment, and am still anxious to do all I can to save you; but, if you continue in open revolt one hour longer, surrounded as you all are by the King's troops, not a man of you can survive the attack, and be assured that even I, for one, will give quarter to none! Consider well my words—you may survive banishment for a time, but from the grave there is no return."

"The words of my dream!" exclaimed Farquhar, in an agitated tone of voice; "Bithidh duil ri fear feachd, ach cha bhi duil ri fear lic. God and Mary, how come they from the lips of this Saxon captain?"

The excitement of the regiment was now so great that Captain Ball requested of Farquhar that two Highlanders should conduct him safely from the wood. Two duinewassals of the Clan Chattan, both corporals, named MacPherson, stepped forward, blew the priming from their pans, and accompanied him to the outposts of his own men—the Saxon Seidar Dearg, or Red English soldiers, as the Celts named them.

Here, on parting from them, the good captain renewed his entreaties and promises, which so far won the confidence of the corporals, that, after returning to the regiment, the whole body, in consequence of their statements, agreed to lay down their arms and submit the event to Providence and a court-martial of officers, believing implicitly in the justice of their cause and the ultimate adherence of the Government to the letters of local service under which they had enlisted.

Farquhar Shaw and the two corporals of the Clan Chattan nobly offered their own lives as a ransom for the honour and liberties of the regiment, but their offer was declined; for so overwhelming was the force against them, that all in the battalion were alike at the mercy of the ministry. On capitulating, they were at once surrounded by strong bodies of horse, foot, and artillery, with their field-pieces grape-shotted; and the most severe measures were faithlessly and cruelly resorted to by those in authority and those in whom they trusted. While, in defiance of all stipulation and treaty with the Highlanders, the main body of the regiment was marched under escort towards Kent, to embark for Flanders, two hundred privates, chiefly gentlemen or cadets of good family, were selected from its ranks and sentenced to banishment, or service for life in Minorca, Georgia, and the Leeward Isles. The two corporals, Samuel and Malcolm MacPherson, with Farquhar Shaw, were marched back to London, to meet a more speedy, and to men of such spirit as theirs, a more welcome fate.

The examinations of some of these poor fellows prove how they had been deluded into service for the Line.

"I did not desert, sirs," said John Stuart, a gentleman of the House of Urrard, and private in Campbell of Carrick's company. "I repel the insinuation," he continued, with pride; "I wished only to go back to my father's roof and to my own glen, because the inhospitable Saxon churls abused my country and ridiculed my dress. We had no leader; we placed no man over the rest."

"I am neither a Catholic nor a false Lowland Whig," said another private—Gregor Grant, of the family of Bothiemurchus; "but I am a true man, and ready to serve the King, though his actions have proved him a liar! You have said, sirs, that I am afraid to go to Flanders. I am a Highlander, and never yet saw the man I was afraid of. The Saxons told me I was to be transported to the American plantations to work with black slaves. Such was not our bargain with King George. We were but a Watch to serve along the Highland Border, and to keep broken clans from the Braes of Lochaber."

"We were resolved not to be tricked," added Farquhar Shaw. "We will meet the French or Spaniards in any land you please; but we will die, sirs, rather than go, like Saxon rogues, to hoe sugar in the plantations."

"What is your faith?" asked the president of the court-martial.

"The faith of my fathers a thousand years before the hateful sound of the Saxon drum was heard upon the Highland Border!"

"You mean that you have lived——"

"As, please God and the Blessed Mary, I shall die—a Catholic and a Highland gentleman; stooping to none and fearing none——"

"None, say you?"

"Save Him who sits upon the right hand of His Father in Heaven."

As Farquhar said this with solemn energy, all the prisoners took off their bonnets and bowed their heads with a religious reverence which deeply impressed the court, but failed to save them.

On the march to the Tower of London, Farquhar was the most resolute and composed of his companions in fetters and misfortune; but on coming in sight of that ancient fortress, his firmness forsook him, the blood rushed back upon his heart, and he became deadly pale; for in a moment he recognised the castle of his strange dream—the castle having a square tower, with four vanes and turrets—and then the whole scene of his foreboding vision, when far away in lone Lochaber, came again upon his memory, while the voice of the warning spirit hovered again in his eat, and he knew that the hour of his end was pursuing him!

And now, amid crowds of country clowns and a rabble from the lowest purlieus of London, who mocked and reviled them, the poor Highlanders were marched through the streets of that mighty metropolis (to them, who had been reared in the mountain solitudes of the Gaël, a place of countless wonders!) and were thrust into the Tower as prisoners under sentence.

Early on the morning of the 12th July, 1743, when the sun was yet below the dim horizon, and a frowsy fog that lingered on the river was mingling with the city's smoke to spread a gloom over the midsummer morning, all London seemed to be pouring from her many avenues towards Tower Hill, where an episode of no ordinary interest was promised to the sight-loving Cockneys—a veritable military execution, with all its stern terrors and grim solemnity.

All the troops in London were under arms, and long before daybreak had taken possession of an ample space enclosing Tower Hill; and there, conspicuous above all by their high and absurd sugar-loaf caps, were the brilliantly accoutred English and Scots Horse Grenadier Guards, the former under Viscount Cobham, and the latter under Lieutenant-General John Earl of Rothes, K.T., and Governor of Duncannon; the Coldstream Guards; the Scots Fusiliers; and a sombre mass in the Highland garb of dark-green tartan, whom they surrounded with fixed bayonets.

These last were the two hundred men of the Reicudan Dhu selected for banishment, previous to which they were compelled to behold the death, or—as they justly deemed it—the deliberate murder under trust, of three brave gentlemen, their comrades.

The gates of the Tower revolved, and then the craped and muffled drums of the Scots Fusilier Guards were heard beating a dead march before those who were "to return to Lochaber no more." Between two lines of Yeomen of the Guard, who faced inwards, the three prisoners came slowly forth, surrounded by an escort with fixed bayonets, each doomed man marching behind his coffin, which was borne on the shoulders of four soldiers. On approaching the parade, each politely raised his bonnet and bowed to the assembled multitude.

"Courage, gentlemen," said Farquhar Shaw; "I see no gallows here. I thank God we shall not die a dog's death!"

"'Tis well," replied MacPherson, "for honour is more precious than refined gold."

The murmur of the multitude gradually subsided and died away, like a breeze that passes through a forest, leaving it silent and still, and then not a sound was heard but the baleful rolling of the muffled drums and the shrill but sweet cadence of the fifes. Then came the word, Halt! breaking sharply the silence of the crowded arena, and the hollow sound of the three empty coffins, as they were laid on the ground, at the distance of thirty paces from the firing party.

Now the elder brother patted the shoulder of the other, as he smiled and said—-

"Courage—a little time and all will be over—our spirits shall be with those of our brave forefathers."

"No coronach will be cried over us here, and no cairn will mark in other times where we sleep in the land of the stranger."

"Brother," replied the other, in the same forcible language, "we can well spare alike the coronach and the cairn, when to our kinsmen we can bequeath the dear task of avenging us!"

"If that bequest be valued, then we shall not die in vain."

Once again they all raised their bonnets and uttered a pious invocation; for now the sun was up, and in the Highland fashion—a fashion old as the days of Baal—they greeted him.

"Are you ready?" asked the provost-marshal.

"All ready," replied Farquhar; "moch-eirigh 'luain, a ni'n t-suain 'mhairt."*

* Early rising on Monday gives a sound sleep on Tuesday.—see MacIntosh's Gaelic Proverbs.

This, to them, fatal 12th of July Was a Monday; so the proverb was solemnly applicable.

Wan, pale, and careworn they looked, but their eyes were bright, their steps steady, their bearing erect and dignified. They felt themselves victims and martyrs, whose fate would find a terrible echo in the Scottish Highlands; and need I add, that echo was heard, when two years afterwards Prince Charles unfurled his standard in Glenfinnan? Thus inspired by pride of birth, of character, and of country—by inborn bravery and conscious innocence, at this awful crisis, they gazed around them without quailing, and exhibited a self-possession which excited the pity and admiration of all who beheld them.

The clock struck the fatal hour at last!

"It is my doom," exclaimed Farquhar; "the hour of my end hath followed me."

They all embraced each other, and declined having their eyes bound up, but stood boldly, each at the foot of his coffin, confronting the levelled muskets of thirty privates of the Grenadier Guards, and they died like the brave men they had lived. One brief paragraph in St. James's Chronicle thus records their fate.

"On Monday, the 12th, at six o'clock in the morning, Samuel and Malcolm MacPherson, corporals, and Farquhar Shaw, a private-man, three of the Highland deserters, were shot upon the parade of the Tower pursuant to the sentence of the court martial. The rest of the Highland prisoners were drawn out to see the execution, and joined in their prayers with great earnestness. They behaved with perfect resolution and propriety. Their bodies were put into three coffins by three of the prisoners, their clansmen and namesakes, and buried in one grave, near the place of execution."

Such is the matter-of-fact record of a terrible fate!

To the slaughter of these soldiers, and the wicked breach of faith perpetrated by the Government, may be traced much of that distrust which characterized the Seaforth Highlanders and other clan regiments in their mutinies and revolts in later years; and nothing inspired greater hatred in the hearts of those who "rose" for Prince Charles in 1745, than the story of the deception and murder (for so they named it) of the three soldiers of the Reicudan Dhu by King George at London. "There must have been something more than common in the case and character of these unfortunate men," to quote the good and gallant old General Stewart of Garth, "as Lord John Murray, who was afterwards colonel of the regiment, had portraits of them hung in his dining-room."

This was the first episode in the history of the Black Watch, which soon after covered itself with glory by the fury of its charge at Fontenoy, and on the field of Dettingen exulted that among the dead who lay there was General Clayton, "the Sassenach" whose specious story first lured them from the Birks of Aberfeldy.

"As the regiment expects to be engaged with the enemy to-morrow, the women and baggage will be sent to the rear. For this duty, Ensign James Campbell, of Glenfalloch."

Such was the order which was circulated in the camp of the 42nd Highlanders (then known as the Black Watch) on the evening of the 28th April, 1745, previous to the Duke of Cumberland's attack on the French outposts in front of Fontenoy. Our battalion (writes one of our old officers) was to form the advanced guard on this occasion, and had been ordered to the village of Veson, where a bivouac was formed, while Ensign Campbell, of Glenfalloch, the same who was afterwards wounded at Fontenoy, marched the baggage, with all the sorrowing women of the corps, beyond Maulpré, as our operations were for the purpose of relieving Tournay, then besieged by a powerful French army under Marshal Count de Saxe, and valiantly defended by eight thousand Dutchmen under the veteran Baron Dorth. It was the will of Heaven in those days that we should fight for none but the Dutch and Hanoverians.

I had been appointed captain-lieutenant to the Black Watch from the old 26th, or Angus's Foot, and having overtaken the corps on its march between the gloomy old town of Liege and the barrier fortress of Maestricht, the aspect and bearing of the Highlanders—we had then only one regiment of them in the service—seemed new and strange, even barbaric to my eyes; for, as a Lowlander, I had been ever accustomed to associate the tartan with fierce rapine and armed insurrection. Yet their bearing was stately, free, and noble; for our ranks were filled by the sons of Highland gentlemen, and of these the most distinguished for stature, strength, and bravery were the seven sons of Captain Maclean, a cadet of the house of Duairt, who led our grenadiers. The very flower of these were the seven tall Macleans, who, since the regiment had been first mustered at the beautiful Birks of Aberfeldy, in May, 1740, had shone foremost in every encounter with the enemy.

Captain Campbell, of Finab, and I seated ourselves beside the Celtic patriarch who commanded our grenadier company, and near him were his seven sons lounging on the grass, all tall and muscular men, bearded to the eyes, athletic, and weather-beaten by hunting and fighting in the Highlands, and inured alike to danger and to toil. Though gentlemen volunteers, they wore the uniform of the privates, a looped-up scarlet jacket and waistcoat faced with buff and laced with white,* a tartan plaid of twelve yards plaited round the body and thrown over the left shoulder; a flat blue bonnet with the fesse-chequé of the house of Stuart round it, and an eagle's feather therein, to indicate the wearer's birth. The whole regiment carried claymores in addition to their muskets, and to these weapons every soldier added, if he chose, a dirk, skene, pair of pistols, and target; in the fashion of the Highlands; thus our front rank men were usually as fully equipped as any that stepped on the muir of Culloden. Our sword-belts were black, and the cartouch-box was slung in front by a waist-belt. In addition to all this warlike paraphernalia, our grenadiers carried each a hatchet and pouch of hand-grenades. The servicelike, formidable, and cap-à-pie aspect of the regiment had impressed me deeply; but Captain Maclean and his seven sons more than all, as they lay grouped near the watchfire, in the red light of which their bearded visages, keen eyes, and burnished weapons were glinting and glowing.

* The regiment was not made royal until 1768.

The beard of old Maclean was white as snow, and flowed over his tartan plaid and scarlet waistcoat, imparting to his appearance a greater peculiarity, as all gentlemen were then closely shaven. As Finab and I seated ourselves by his fire, he raised his bonnet and bade us welcome with a courtly air, which consorted ill with his sharp west Highland accent. His eye was clear and bold in expression, his voice was commanding and loud, as in one whose will had never been disputed. Close by was his inseparable henchman and foster-brother Ronald MacAra, the colour-sergeant of his company, an aged Celt of grim presence and gigantic proportions, whose face had been nearly cloven by a blow from a Lochaber axe at the battle of Dunblane.

"Welcome, gentlemen," said old Maclean, "a hundred thousand welcomes to a share of our supper, a savoury road collop, as we call it at home. It was a fine fat sheep that my son Dougal found astray in a field near Maulpré; and here is a braw little demijohn of Belgian wine, which Alaster borrowed from a boor close by. These other five lads are also my sons, Dunacha, Deors, Findlay Bane, Farquhar Gorm, and Angus Dhu, all grenadiers in the King's service, and hoping each one to be like myself a captain and to cock their feathers among the best in the Black Watch. Attend to our comrades, my braw lads."

The lads, the least of whom was six feet in height, assisted us to a share of the sheep, which was broiling merrily on the glowing embers, and from which their comrades, who crowded round, partook freely, cutting off the slices, as they sputtered and browned, by their long dirks and sharp skenes. The seven grenadiers were all fine and hearty fellows, who trundled Alaster's demijohn of wine from hand to hand round the red roaring fire, on which the grim henchman or colour-sergeant heaped up, from time to time, the doors and rafters of an adjacent house, and there we continued to carouse, sing, and tell stories, until the night was far advanced.

The month was April, and the night was a glorious one; all our bivouac was visible as if at noonday. The hum of voices, the scrap of a song, a careless laugh, the neigh of a horse, or the jangle of a bridle alone broke the silence of the moonlit sky; though at times we heard the murmur of a stream that stole towards the Scheldt, like a silver current through the fields of sprouting corn, and under banks where the purple foxglove, the pink wild rose, and the green bramble hung in heavy masses.