Title: Rudimentary Architecture for the Use of Beginners

Author: W. H. Leeds

Release date: May 28, 2021 [eBook #65462]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Charlene Taylor and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

THE ORDERS,

AND THEIR ÆSTHETIC PRINCIPLES.

BY

W. H. LEEDS, ESQ.

London:

JOHN WEALE,

ARCHITECTURAL LIBRARY, 59, HIGH HOLBORN.

M.DCCC.XLVIII.

CONTENTS.

| PAGE | ||||

| The Orders generally | 3 | |||

| First Order: | Ancient Doric | 14 | ||

| Modern Do. | 25 | |||

| Tuscan | 28 | |||

| Second, or Voluted-capital, Order: | Greek Ionic | 30 | ||

| Roman and Modern | 46 | |||

| Third, or Foliaged-capital Order: | Corinthian | 53 | ||

| Composite | 62 | |||

| Columniation: Forms and Denominations | ||||

| of Temples and Porticoes | 68 | |||

| Intercolumniation | 77 | |||

| Glossarial Index | 82 | |||

It is important that an elementary treatise,—more particularly if it profess to be a popular one, intended for the use of beginners as well as for professional students,—should not only give rules, but explain principles also; and unless the latter be clearly defined, the memory alone is exercised, perhaps fatigued, owing to the former being unsupported by adequate reasoning. To confine instruction to bare matter-of-fact is not to simplify, much less to popularize it; since such mode entirely withholds all that explanation which is so necessary for a beginner, who will else probably feel more disheartened than interested. Any study which is presented in its very driest form by being divested of all that imparts interest to the subject, will soon become dry and uninteresting in itself, and prejudice may thus be excited against it at the very outset.

Those who pursue the profession of Architecture must of course apply themselves to the study of it technically, and acquire their knowledge of it, both theoretical and practical, by methods which partake more or less of routine instruction. Others neither will nor even can do so. If the public are ever to become acquainted with Architecture,—not, indeed, with its scientific and mechanical processes of construction, but in its character of Fine Art and Design,—other methods of study [Pg 2] than those hitherto provided must be furnished, as it appears to have been assumed that those alone who have been educated to it professionally can properly understand any thing of even the Art of Architecture,—a fatal mistake, which, had it clearly perceived its own interest, the Profession itself would long since have attempted to remove; it being clearly to the interest of Architects that the public should acquire a taste and relish for Architecture.

The study of Architecture, it may be said, has of late years acquired an increased share of public attention; but it has been too exclusively confined to the Mediæval and Ecclesiastical styles, which have consequently been brought into repute and general favour,—a result which strongly confirms what has just been recommended, namely, the policy of diffusing architectural taste as widely as possible. As yet, the taste for Architecture and the study of it, so promoted, has not been duly extended; for next to that of being acquainted with the Mediæval, the greatest merit, it would seem, is that of being ignorant of Classical Architecture and its Orders; which last, however ill they may have been understood, however greatly corrupted and perverted, influence and pervade, in some degree, the Modern Architecture of all Europe, and of all those countries also to which European civilization has extended. Nevertheless, no popular Manual on the subject of the Orders has yet been provided,—a desideratum which it is the object of the following pages to supply.

[Pg 3]

RUDIMENTARY ARCHITECTURE.

Although this little treatise is limited to the consideration of Ancient and Classic Architecture, we may be allowed to explain briefly what is to be understood by Architecture in its quality of one of the so-called Fine Arts, if only to guard against confused and erroneous notions and misconceptions. It will therefore not be deemed superfluous to state that there is a wide difference between Building and Architecture,—one which is apparently so very obvious that it is difficult to conceive how it can have been overlooked, as it generally has been, by those who have written upon the subject. Without building we cannot have architecture, any more than without language we can have literature; but building and language are only the matériel,—neither, the art which works upon that matériel, nor the productions which it forms out of it. Building is not a fine art, any more than mere speaking or writing is eloquence or poetry. Many have defined architecture to be the art of building according to rule: just as well might they define eloquence to be the art of speaking according to grammar, or poetry the art of composing according to prosody. Infinitely more correct and rational would it be to say that architecture is building greatly refined upon,—elevated to the rank of art by being treated æsthetically, that is to say, artistically. In short, architecture is building with something more than a view to mere utility and convenience; it is building in such a manner as to delight the eye by beauty of forms, to captivate the imagination, and to [Pg 4] satisfy that faculty of the mind which we denominate taste. Further than this we shall not prosecute our remarks on the nature of architecture, but come at once to that species of it which is characterized by the Orders.

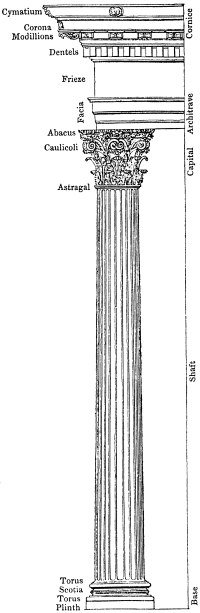

In its architectural meaning, the term ORDER refers to the system of columniation practised by the Greeks and Romans, and is employed to denote the columns and entablature together; in other words, both the upright supporting pillars and the horizontal beams and roof, or trabeation, supported by them. These two divisions, combined, constitute an Order; and so far all Orders are alike, and might accordingly be reduced to a single one, although, for greater convenience, they are divided into three leading classes or families, distinguished as Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian. It was formerly the fashion to speak of the FIVE ORDERS, and also to treat of them as if each Order were reduced to a positive standard, admitting of very little deviation, instead of being in reality included in many subordinate varieties, which, however they may differ from each other, are all formed according to one common type, and are thereby plainly distinguished from either of the two other Orders. The vulgar Five Orders’ doctrine is, it is to be hoped, now altogether exploded; for if the so-called Tuscan, which is only a ruder and bastard sort of Doric, and of which no accredited ancient examples remain, is to be received as a distinct Order, a similar distinction ought to be established between the original Ancient or Grecian and the derivative Roman and Italian Doric, which differ from the other quite as much, if not more so, than the Tuscan does from either. Even the Grecian Doric itself exhibits many decided varieties, which, though all partaking of one and the same style, constitute so many Doric Orders. The Pæstum-Doric, for instance, is altogether dissimilar from the Athenian or that of the Parthenon. Again, if the Composite is to be received as a distinct Order from the Corinthian, merely on account of its capital being of a mixed character, partaking of the Ionic, inasmuch as it has volutes, and of the Corinthian in its foliage, the [Pg 5] Corinthian itself may with equal propriety be subdivided into as many distinct Orders as there are distinct varieties; and the more so, as some of the latter vary from each other very considerably in many other respects than as regards their capitals. Except that the same general name is applied to them, there is very little in common between such an example of the Corinthian or foliaged-capital class as that of the monument of Lysicrates, and that of the Temple at Tivoli, or between either of them or those of the Temple of Jupiter Stator and the Pantheon, not to mention a great many others. Instances of the so-called Composite are, moreover, so exceedingly few, as not even to warrant our calling it the Roman Order, just as if it had been in general use among the Romans in every period of their architecture. With far greater propriety might the Corinthian itself, or what we now so designate, be termed the Roman Order, being not only the one chiefly used by that people, but also the one which they fairly appropriated to themselves, by entering into the spirit of it, and treating it with freedom and artistic feeling. In fact, we are indebted far more to Roman than to Grecian examples for our knowledge of the Corinthian; and it is upon the former that the moderns have modelled their ideal of that Order.

What has been said with regard to striking diversity in the several examples of the Corinthian, holds equally good as to those of the Ionic Order, in which we have to distinguish not only between Roman and Grecian Ionic, but further, between Hellenic and Asiatic Ionic. Nor is that all: there is a palpable difference between those examples whose capitals have a necking to them, and those which have none,—a difference quite as great, if not greater, than that which is recognized as sufficient to establish for the Composite the title of a distinct Order from the Corinthian; inasmuch as the necking greatly enlarges the proportion of the whole capital, and gives increased importance to it. The Ionic capital further admits of a species of variation which cannot possibly take place in those of either of the other two Orders: it may have either two faces and two baluster [Pg 6] sides, or four equal and similar sides,—the volutes being, in the latter case, turned diagonally, the mode chiefly practised by the Romans; but by the Greeks, and that not always, in the capitals at the ends of a portico, by placing the diagonal volute at the angle only, so as to obtain two outer faces for the capital, one in front, the other on the ‘return’ or flank of the portico.

It is therefore unnecessary to say, that to divide the Orders into Five, as has been done by all modern writers, until of late years, and to establish for each of them one fixed, uniform character, is altogether a mistake; and not only a mere mistake as regards names and other distinctions, but one which has led to a plodding, mechanical treatment of the respective Orders themselves, nothing being left for the Architect to do, so far as the Order which he employs is concerned, than merely to follow the example which he has selected,—in other words, merely to copy instead of designing, by imitating his model with artistic freedom and spirit. Our view of the matter, on the contrary, greatly simplifies and rationalizes the doctrine of the Orders, and facilitates the study of them by clearing away the contracted notions and prejudices which have been permitted to encumber it; and owing to which, mere conventional rules, equally petty and pedantic, have been substituted for intelligent guiding maxims and principles.

Having thus far briefly explained the rationale of the Orders with regard to the division of them into three leading classes, each of which, distinct from the other two, yet comprises many varieties or species,—which, however much they may differ with respect to minor distinctions, all evidently belong to one and the same style, or what we call Order,—we have now to consider their constituent parts, that is, those which apply to every Order alike. Hitherto it has been usual with most writers to treat of an Order as consisting of three principal parts or divisions, viz. pedestal, column, and entablature. The first of these, however, cannot by any means be regarded as an [Pg 7] integral part of an Order. So far from being an essential, it is only an accidental one,—one, moreover, of Roman invention, and applicable only under particular circumstances. The pedestal no more belongs to an Order than an attic or podium placed above the entablature. In the idea of an Order we do not include what is extraneous to the Order itself: it makes no difference whether the columns stand immediately upon the ground or floor, or are raised above it. They almost invariably are so raised, because, were the columns to stand immediately upon the ground or a mere pavement, the effect would be comparatively mean and unsatisfactory; the edifice would hardly seem to stand firmly, and, for want of apparent footing, would look as if it had sunk into the ground, or the soil had accumulated around it. With the view, therefore, of increasing height for the whole structure, and otherwise enhancing its effect, the Greeks placed their temples upon a bold substructure, composed of gradini or deep steps, or upon some sort of continuous stylobate; either of which modes is altogether different from, and affords no precedent for, the pedestal of modern writers. And here it may be remarked, that of the dignity imparted to a portico by a stylobate forming an ascent up to it in front, we have a fine example in that of St. George’s Church, Bloomsbury, which so far imitates the celebrated Maison Carrée at Nismes. Nevertheless, essential as some sort of stylobate is to the edifice itself, it does not properly belong to it, any more than that equally essential—in fact more indispensable part—the roof.

It is not without some regret that we abandon, as wholly untenable, the doctrine of the pedestal being an integral part of an Order: it would be so much more agreeable to say that the entire Order consists of three principal divisions, just the same as each of the divisions themselves. As regards the entire structure, such triplicity, that of ‘beginning, middle, and end,’ was observed. For ‘beginning,’ there was substructure, however denominated, or whether expressly denominated at all, or not; for ‘middle,’ there were the columns; and for ‘end’ or [Pg 8] completion, the entablature. For the whole of a structure, there is or ought to be such ‘beginning, middle, and end;’ but from the Order itself we exclude one of them, as not being dependent upon it either for character or treatment.

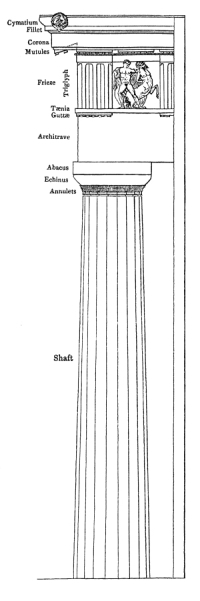

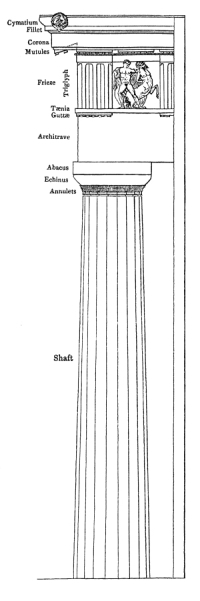

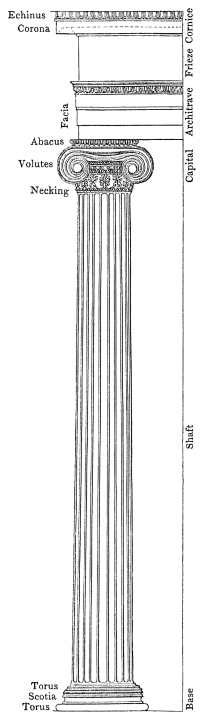

The pedestal being discarded as something apart from the Order itself, the latter is reduced to the two grand divisions of column and entablature, each of which is subdivided into three distinct parts or members, viz. the column, into base, shaft, and capital; the entablature, into architrave, frieze, and cornice; so that the latter is to the entablature what the capital is to the column, namely, its crowning member,—that which completes it to the eye. Yet, although the above divisions of column and entablature hold good with regard to the general idea of an Order, the primitive Greek or Doric one does not answer to what has just been said, inasmuch as it has no base,—that is, no mouldings which distinctly mark the foot of the column as a separate and ornamented member. Hence it will perhaps be thought that this Order is not so complete as the others, since it wants that member below which corresponds with the capital above. Still the Grecian Doric column is complete in itself: it needs no base,—in fact, does not admit of such addition without forfeiting much of its present character, and thus becoming something different. Were there a distinct base, the mouldings composing it could not very well exceed what is now the lower diameter or actual foot of the column; because, were it to do so, either the base would become too bulky in proportion to the capital, or the latter must be increased so as to make it correspond in size with the enlarged lower extremity. Even then that closeness of intercolumniation (spacing of the columns), which contributes so much to the majestic solidity that characterizes the genuine Doric, could not be observed; unless the columns were put considerably further apart, the bases would scarcely allow sufficient passage between them. The only way of escaping from these objections and difficulties is by making the shaft of the column considerably more slender, so that what was before the [Pg 9] measure of the lower diameter of the shaft itself, becomes that of the base. That can be done—has been done, at least something like it; but the result is an attenuated Roman or Italian Doric, differing altogether in proportions from the original type or order. The shaft no longer tapers visibly upwards, or, what is the same thing, expands below.

Before we come to speak of the Orders severally and more in detail, there are some other matters which require to be noticed; one of which is the origin of the Greek system of columniation, or the prototype upon which it was modelled. Following Vitruvius, nearly all writers have agreed to recognize in the columnar style of the ancients the primitive timber hut, as furnishing the first hints for and rudiments of it. Such theory, it must be admitted, is sufficiently plausible, if only because it can be made to account very cleverly for many minor circumstances. Unfortunately, it does not account at all for, or rather is in strong contradiction to, the character of the earliest extant monuments of Greek architecture. Timber construction would have led to very different proportions and different taste. Had the prototype or model been of that material, slenderness and lightness, rather than ponderosity and solidity, would have been aimed at; and the progressive changes in the character of the Orders would have been reversed, since the earliest of them all would also have been the lightest of them all. The principles of stone construction have so evidently dictated and determined the forms and proportions of the original Doric style, as to render the idea of its being fashioned upon a model in the other material little better than an absurd though time-honoured fiction. Infinitely more probable is it, that the Greeks derived their system of architecture from the Egyptians; because, much as it differs from that of the latter people with regard to taste and matters of ornamentation, it partakes very largely of the same constitutional character. At any rate the doctrine of a timber origin applies as well to the Egyptian as to the Hellenic or Grecian style. Indeed, if there be any thing at all that favours such doctrine, it is, that construction with [Pg 10] blocks of stone would naturally have suggested square pillars instead of round ones; the latter requiring much greater labour and skill to prepare them than the others. But, as their pyramids and obelisks sufficiently testify, the most prodigal expenditure of labour was not at all regarded by the Egyptians. That, it will perhaps be said, still does not account for the adoption of the circular or cylindrical form for columns. We have therefore to look for some sufficiently probable motive for the adoption of that form; and we think that we find it in convenience. In order to afford due support to the massive blocks of stone placed upon them, the columns were not only very bulky in proportion to their height, but were placed so closely together, not only in the fronts of porticoes, but also within them, that they would scarcely have left any open space. Such inconvenience was accordingly remedied by making the pillars round instead of square. Should such conjectural reason for the adoption of circular columns be rejected, it is left to others to propound a more satisfactory one, or to abide, as many probably will do, by the old notion of columns being so shaped in order to imitate the stems of trees. It is enough that whatever accounts for the columns being round in Egyptian architecture, accounts also for their being the same in that of the Greeks.

Among other fanciful notions entertained with regard to columns and their proportions, is that of the different orders of columns being proportioned in accordance with the human figure. Thus the Doric column is said to represent a robust male figure, and those of the two other Orders, female ones,—the Ionic, a matron; the Corinthian, a less portly specimen of feminality. Now, so far from there being any general similitude between a Grecian Doric column and a robust man, their proportions are directly opposite,—the greater diameter of the column being at its foot, while that of the man is at his shoulders. The one tapers upwards, the other downwards. If the human figure and its proportions had been considered, columns would, in conformity [Pg 11] with such type, have been wider at the top of their shafts than below, and would have assumed the shape of a terminus,[1] or of a mummy-chest. With regard to the other two Orders, it is sufficient to observe, that if so borrowed at all, the idea must have been preposterous. We happen to have a well-known example of statues or human figures, and those, moreover, female ones, being substituted for columns beneath an entablature; and so far are they from confirming the pretended analogy between the Ionic column and the proportions of a female, that they decidedly contradict it, those figures being greatly bulkier in their general mass than the bulkiest and stoutest columns of the Doric Order. At any rate, one hypothesis might satisfy those who will not be satisfied without some fancy of the kind, because two together do not agree: if columns originated in the imitation of stems of trees, we can dispense with the imitation of men and women, and vice versá.

Some may think that it is hardly worth while to notice such mere fancies; yet it is surely desirable to attempt to get rid of them by exposing their absurdity, more especially as they still continue to be gravely brought forward and handed down traditionally by those who write upon the Orders, or who, if they do not actually write, repeat what others have written. It is worth while to clear away, if possible, and that, too, at the very outset of the study, erroneous opinions, prejudices, and misconceptions. We do not pretend to explain and trace, step by step, the progress of the Doric Order, and of the columnar system of the Greeks, from their first rudiments and formation. We have only the results of such progressive development or formation; of the actual formation itself we neither know nor can now ever know any thing. The utmost that can now be done is to take the results themselves, and from them to reason backwards to causes and motives. Adopting such a course, we may first observe, that there is a [Pg 12] very striking and characteristic difference between Egyptian and Grecian taste and practice in one respect: in the former style the columns are invariably cylindrical, or nearly so,—in the other they are conical, that is, taper upwards, and in some instances so much so, that were they prolonged to double their height, they would be almost perfect cones, and terminate like a spire. This tapering greatly exceeds that of the stems of trees, taking for their stem the trunk, from above which the branches begin to shoot out. It appears to have been adopted for purely artistic reasons, certainly not for the sake of any positive advantage, since the diminution of the shaft, and the great contraction of the diameter just below the capital, must rather decrease than at all add to the strength of the column. What, then, are the artistic qualities so obtained? We reply,—variety and contrast, and the expression of strength without offensive heaviness. The sudden or very perceptible diminution of the shaft,—it must be borne in mind that our remarks refer exclusively to the original Greek style or Doric Order,—produces a double effect; it gives the column an expression of greater stability than it otherwise would, combined with comparative lightness. What is diminution upwards, is also expansion downwards; and similar difference and contrast take place also with respect to the intercolumns, although in a reverse manner, such intercolumns being wider at top than at bottom. So far the principle of contrast here may be said to be twofold, although one of the two sorts of contrast inevitably results from the other. Were it not for the great diminution of the shaft, the columns would appear to be too closely put together, and the intercolumns much too narrow, that is, according, at least, to the mode of intercolumniation practised by the Greeks in most of their structures in the Doric style; whereas such offensive appearance was avoided by the shaft being made considerably smaller at top than at bottom,—consequently the intercolumns wider above than below, in the same ratio; so that columns which at their [Pg 13] bases were little more than one diameter apart, became more than two, that is, two upper diameters apart at the top of their shafts, or the neckings of their capitals. In this style every thing was calculated to produce a character of majestic simplicity,—varying, however, or rather progressing, from heaviness and stern severity to comparative lightness of proportions,—for examples differ greatly in that respect: in some of the earlier ones the columns are not more than four diameters in height, while in some of the later they are upwards of six, which last-mentioned proportions not only amount to slenderness, but also destroy others. The capital itself may be proportioned the same as before relatively to the diameter of the column, but it cannot possibly bear the same ratio as before to its height. The average proportions for that member are one diameter for its width at its abacus, and half a diameter for its depth: consequently, if the entire column be only four diameters in height, the capital is ⅛th of it, or equal to ⅐th of the shaft; whereas, if the column be six or more diameters, the capital becomes only ¹/₁₂th of the column, or even less, so that the latter appears thin and attenuated, and the other member too small and insignificant. Yet though the original Greek Order or style exhibits considerable diversity with respect to mere proportions, it was otherwise very limited in its powers of expression, and moreover something quite distinct from the nominal Doric of the Romans and the Italians, as will be evident when we come to compare the latter with it.

Before we enter upon this part of our subject, and previous to an examination of the details of the several Orders, it should be observed that the diameter, that is, the lower diameter of the column, is the standard by which all the other parts and members of an Order are measured. The diameter is divided into 60 minutes, or into two halves or modules of 30 minutes each; and those minutes are again subdivided into parts or seconds when extreme accuracy of measurement is required; which two last are noted thus: 5′ 10″, for instance, meaning five minutes and ten seconds. [Pg 14]

It has been already observed, that in the genuine Doric the column consists of only shaft and capital, which latter is composed of merely an echinus and abacus, the first being a circular convex moulding, spreading out beneath the other member, which, although a very important one, is no more than a plain and shallow square block upon which the architrave rests, not only firmly and safely, but so that the utmost expression of security is obtained, and pronounced emphatically to the eye. Such expression arises from the abacus being larger than the soffit or under surface of the architrave itself; and as the former corresponds, or nearly so, with the lower diameter of the shaft, it serves to make evident at a glance that the foot of the column is greater than the soffit of the architrave placed upon the columns. Thus, as measured at either extremity, the column is greater than the depth or thickness of the architrave, and projects beyond the architrave and general plane of the entablature. Now this [Pg 15] would produce a most unsightly effect were the columns of the same, or nearly the same diameter throughout. In such case they would appear not only too large, but most clumsily so, and the entablature would have the look of being set back in the most awkward and most unaccountable manner. Instead of which, the architrave, and consequently the general plane of the whole entablature, actually overhangs the upper part of the shaft, in a plane about midway between the smallest diameter of the column, just below the capital and the face of the abacus. Even this, the overhanging of the entablature, would be not a little offensive to the eye, were the abacus no larger than the architrave is deep; whereas, being larger, it projects forwarder than the face of the architrave, thereby producing a powerful degree of one species of æsthetic effect, namely, contrast,—and if contrast, of course variety also; for though there may be variety without contrast, there cannot be contrast without variety. Another circumstance to be considered is, that were not such projection beyond the face of the architrave given to the abacus, that and the rest of the capital could not correspond with the foot of the shaft, and thus equalize the two extremities of the entire column. As now managed, all contradictions are reconciled, and the different sorts of contrast are made to contribute to and greatly enhance general harmony. In the outline of the column we perceive, first, contraction,—then expansion, and that in both directions,—for in like manner as the column diminishes upwards and the capital expands from it, its shaft may be said to expand and increase in bulk downwards, so as to agree with the abacus or upper extremity.

Though a few exceptions to the contrary exist, the shaft of the Doric column was generally what is technically called fluted, that is, cut into a series of channels touching each other, and thus forming a series of ridges upon its surfaces,—a mode of decoration, we may observe, altogether the reverse of that which was practised by the Egyptians, some of whose columns exhibit, instead of channels or [Pg 16] hollows, a series of convex mouldings that give them the appearance of being composed of very slender pillars or rods bound together. Many have attempted, with perhaps pains-taking but idle inquiry, to account for the origin of such fluting or channeling, supposing, among other things, that it was derived from the cracks and crevices in the stems of trees, or from the streakings occasioned by rain on the shafts of the columns. Most perverse ingenuity! We do not find any thing like such marked streakings on columns even in this rainy English climate of ours; much less would they have been at all visible in such a climate as that of Greece. Others have supposed that these channels were at first intended to hold spears! that is, to prevent them from slipping and falling down when set up against a column; than which idea it is hardly possible for the utmost stretch of ingenuity to go farther in absurdity.

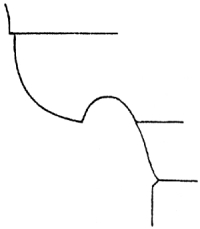

We, who are less ambitious, content ourselves with supposing that the fluting of columns was introduced and adopted principally for the sake of effect. If other motives for doing so existed, we know them not, nor need we care, since study of effect alone suffices to account for such mode of decoration. By multiplying its surfaces, it gives variety to the shaft of the column, and prevents it from showing as a mere mass. With the same, or very nearly the same bulk and degree of solidity as before, it causes the column to appear much less heavy than it otherwise would do, and contributes to a pleasing diversity of light and shade, reminding us of Titian’s ‘bunch of grapes.’ Being upon a curved surface, the channels serve to render the circularity of the column more apparent, since, though they are all of the same width, they show to the eye narrower and narrower on each side of the centre one,—no matter in what direction the column is viewed. Here then we have variety combined with uniformity, and a certain apparent or optical irregularity with what we know to be perfect regularity. In the Doric Order the number of channels is either sixteen or twenty,—afterwards increased in the other Orders to twenty-four; for [Pg 17] they are invariably of an even number, capable of being divided by four; so that there shall always be a centre flute on each side of the column, that is, in a line with the middle of each side of the abacus. Doric flutings are much broader and shallower than those of the Ionic or Corinthian Orders;—broader for two reasons,—first, because they are fewer in number; and secondly, because there are no fillets or plain spaces left between them upon the surface of the shaft. Their proportionably much greater shallowness, again, may be accounted for equally well: were the channels deeper, not only would they seem to cut into the shaft too much, and weaken it, but also produce much too strong shadows; and another inconvenience would be occasioned, for the arrises or ridges between the channels would become very sharp and thin, and liable to be injured. The mode of fluting Doric columns with mere arrises between the channels, instead of fillets, has been retained by the moderns as characteristic of the Order; but as the Order has been treated by them, it is little better than a mere distinction, with very little regard to general character. In the original Doric almost every part is marked by breadth, or by flatness, or by sharpness. There are no curved mouldings or surfaces, except the cymatium of the cornice and the echinus of the capital, which last is generally kept exceedingly flat. The breadth and shallowness of the channels, and the flat curves in which they commence and terminate, are therefore in perfect keeping with the style in other respects; so also are the sharp arrises or ridges between the channels or flutings on the surface of the shaft, they being expressive of a severe simplicity. The same remark applies to the horizontal annular narrower channels or incisions immediately beneath the echinus of the capital, and lower down, which last are just the reverse of the projecting astragal or convex moulding given to the Doric capital by the moderns. Why such horizontal channels or grooves should have been cut in the very thinnest and weakest part of the column, where they diminish instead of adding to strength, it is not easy to say, except [Pg 18] that they were merely for the sake of effect,—of producing shadow, and increasing the proportions of the capital, to which they seem to belong. We leave others, should any be so disposed, to object that the lowermost groove or grooves, as the case may be, give the capital the appearance of being a separate piece, merely joined on to the shaft without such joining being concealed. Looking at it differently, we will rather say that such groove is intended to mark to the eye the commencement of the capital, the portion above it of the shaft being thereby converted into the hypotrachelium or necking of the capital itself, which is thus enlarged in appearance without being actually increased, and rendered unduly heavy. It is not, however, every example of the Order that has such necking: while in some the groove separating the capital from the shaft is diminished to a mere line,—which looks like a joining not intended to show itself,—in others it is omitted altogether. With respect to the echinus, we have little more to remark than that its office—which it performs admirably—is, by expanding out, to connect the diminished upper end of the column with the overhanging abacus; and the former being circular and the latter square, but adapted to each other in size, a beautiful combination is produced of a circle inscribed within a square; and the result is variety, contrast, and harmony. In its profile or section,—by which latter term is understood the contour of any moulding or other member,—it is usually very flat, little more than a portion of a cone (turned downwards), with scarcely any perceptible degree of convexity, except just beneath the abacus, where it is suddenly rounded and diminished, so that the abacus does not seem to press upon or compress it too much.

We arrive now at the entablature, the first or lowermost division of which, the architrave, otherwise called by the Greek name of epistylium (from ἐπι, upon, and στύλος, column), is no more than a plain surface whose height, including the tænia or fillet which finishes it and separates it from the frieze, is equal to the [Pg 19] upper diameter of the column. Such, at least, may be considered its standard proportion, that by means of which it conforms to and harmonizes with the column itself. The second or middle division of the entablature, namely, the frieze, constitutes in the Doric style a very characteristic feature of the Order, being invariably distinguished by its triglyphs and metopes. The former of these are upright channeled blocks, affixed to or projecting from the frieze, and are supposed to have been originally intended to represent the ends of inner beams laid upon the architrave transversely to it. The metopes, on the contrary, are not actually architectural members, but merely the intervals or spaces between the triglyphs; so that without the latter there could not be the others, because it is the triglyphs which produce the metopes. With slight variations in different examples, the frieze is of about the same height as the architrave,—a trifle less, rather than more; and the average proportion for the breadth of the triglyphs is the mean diameter of the column, or that taken midway of the shaft. The face of the triglyph has two glyphs or channels carved upon it, and its edges beveled off into a half channel, thus making what is equal to a third glyph, whence the name triglyph, or three-channeled. We have till now reserved speaking of what, although it shows itself upon the architrave, belongs to the triglyph, and is in continuation of it, namely, the fillet and guttæ attached to the tænia of the architrave immediately beneath each triglyph, and corresponding with it in width. These small conical guttæ or drops are supposed, rather whimsically, by some to represent drops of rain that have trickled down the channels of the triglyph, and settled beneath the ledge of the architrave. Others suppose them to have been intended to indicate the heads of nails, screws, or studs. Leaving all such suppositions to those who have a taste for them, we will be satisfied with discerning artistic intention and æsthetic effect. That member of the triglyph,—for such we must be allowed to consider it,—is of great value, serving, as it does, to impart [Pg 20] somewhat of decoration to the architrave, to break the monotony of the otherwise uninterrupted line of the tænia, and to connect, to the eye at least, the architrave and frieze together. Although in a much fainter degree, the architrave is thus made to exhibit the same system of placing ornamental members at regular distances from each other, as is so energetically pronounced in the frieze itself. If it be asked why the same, or something equivalent to it, was not extended to the architrave in the other Orders, our answer is, because a similar motive for doing it does not exist. The triglyph being suppressed in the Ionic and Corinthian frieze, the accompanying guttæ beneath it were of necessity omitted also, otherwise they would have made evident that the triglyph ought to have been shown likewise. There is, indeed, one example, the monument of Thrasyllus, of a Grecian Doric entablature, whose frieze is without triglyphs (wreaths being substituted for them), and the guttæ are nevertheless retained. But how?—instead of being placed at intervals, as if there were triglyphs, they are continued uninterruptedly throughout, so that the idea of triglyph disappears; besides which, the example here referred to is altogether so anomalous and exceptional as to be not so much a specimen of the Doric Order as of the Doric style, modified according to particular circumstances; on which account it is highly valuable, since we may learn from it that where peculiar circumstances required—at least admitted of peculiar treatment, the Greeks did not scruple to avail themselves of the liberty so afforded.

With regard to the arrangement of the triglyphs, one is placed over every column, and one or more intermediately over every intercolumn (or space between two columns), at such distance from each other that the metopes are square; in other words, the height of the triglyph is the measure for the distance between it and the next one. In the best Greek examples of the Order there is only a single triglyph over each intercolumn, whence that mode is sometimes called monotriglyphic or single-triglyphed intercolumniation; which is the closest of all, the distance from axis to axis of the columns being [Pg 21] limited to the space occupied above by two metopes and two triglyphs, i. e. one whole triglyph and two halves of triglyphs. In such intercolumniation the number of the triglyphs is double the number of the columns, minus one. Further, it is evident that as there must be a triglyph over every column, the triglyphs must regulate the intercolumniation. The width of the intercolumns cannot be at all less than the proportion above mentioned; neither can it be increased, except by introducing a second triglyph,—and if a second triglyph, a second metope also, over each intercolumn, thus augmenting the distance between the columns to half as much again, which becomes, perhaps, too much, the difference between that and the other mode being considerably more than the diameter of a column; whereas in the other Orders the intercolumns may be made, at pleasure, either a little wider or a little narrower than usual. One peculiarity of the Grecian Doric frieze is, that the end triglyphs, instead of being, like the others, in the same axis or central line as the columns beneath, are placed quite up to the edge or outer angle of the frieze. In itself this is, perhaps, rather a defect than the contrary, although intended to obviate another defect,—that of a half metope or blank space there,—for it produces not only some degree of irregularity, but of æsthetic inconsistency also, the triglyph so placed being, as it were, on one side of, instead of directly over the column. One advantage attending it is, that the extreme intercolumns become in consequence narrower than the others by half a triglyph, and accordingly a greater degree and expression of strength is given to the extremities of a portico.

The Doric Cornice.—The third and last division of the entablature which remains to be considered is, although exceedingly simple, strongly characteristic, and boldly marked. With regard to its proportions, it is about a third or even more than a third less than the other two, and may itself be divided into three principal parts or members, viz. the corona, with the mutules and other [Pg 22] bed-mouldings, as they are termed, beneath it and the epitithedas above it. The mutules are thin plates or shallow blocks attached to the under side or soffit of the corona, over each triglyph and each metope, with the former of which they correspond in breadth, and their soffits or under-surfaces are wrought into three rows of guttæ or drops, conical or otherwise shaped, each row consisting of six guttæ, or the same number as those beneath each triglyph. Nothing can be more artistically disposed: in like manner, as an intermediate triglyph is placed over every two columns, so is an intermediate mutule over every two triglyphs. The smaller members increase in number as they decrease in size; and in the upper and finishing part of the Order, the eye is led on horizontally, instead of being confined vertically to the lines indicated by the columns below. The corona is merely a boldly projecting flat member, not greatly exceeding in its depth the abacus of the capital; in some examples it is even less. The epitithedas, or uppermost member of the cornice, is sometimes a cymatium, or wavy moulding, convex below and concave above; sometimes an echinus moulding, similar in profile to the echinus of the capital. The cornice may be said to be to the entablature, and indeed to the whole Order, what the capital is to the column,—completing and concluding it in a very artistic manner. By its projection and the shadow which it casts, the cornice gives great spirit and relief to the entablature, which would else appear both heavy and unfinished. In the horizontal cornice beneath a pediment, the epitithedas is omitted, and shows itself only in the sloping or raking cornices, as they are called, along the sides of the pediment.

Antæ.—Pilasters, as well as columns, belong to an Order, and in modern practice are frequently substituted indifferently for columns, where the latter would be engaged or attached to a wall. In Grecian architecture, however, the antæ,—as they are thus termed, to distinguish them from other pilasters,—are never so employed. They are never placed consecutively, or in any series, but merely as a facing at the end of a projecting wall, as where a portico [Pg 23] is enclosed at each end by the walls forming the sides of the structure, in which case it is described as a portico in antis. Although they accompany columns, and in the case just mentioned range in the same line with them, antæ differ from them, inasmuch as their shafts are not diminished; for which reason their faces are not made so wide as the diameter of the columns, neither are their capitals treated in the same manner, as both shaft and capital would be exceedingly clumsy. The expanding echinus of the column capital is therefore suppressed, and one or more very slightly projecting faciæ, the uppermost of which is frequently hollowed out below, so as to form in section what is called the ‘bird’s beak’ moulding. In a portico in antis the want of greater congruity between the antæ and the columns is made up for by various contrasts. Flatness of surface is opposed to rotundity, vertical lines to inclined ones (those of the outline and flutings of the column), and uniformity, in regard to light, to the mingled play of light and shade on the shafts of the columns. Instead of attempting to keep up similarity as far as possible, the Greeks made a studied distinction between antæ and columns, not only in those respects which have been noted above, but carried difference still further, inasmuch as they never channeled the faces of their antæ, whereas the moderns flute their pilasters as well as columns. Hardly was such marked distinction a mere arbitrary fashion; it is more rational to suppose that it was adopted for sufficient æsthetic reasons and motives; nor is it difficult to account, according to them, for the omission of channeling on the shafts of antæ. Upon a plain surface the arrises between the channels would have occasioned an unpleasing harshness and dryness of effect, as is the case with fluted Doric pilasters, and would have been attended with monotony also, the lines being all vertical, and consequently parallel to each other; whereas in the column, the channels diminish in breadth upwards, and all the lines are inclined, [Pg 24] and instead of being parallel, converge towards each other, so that were the shaft sufficiently prolonged, they would at last meet in a common point or apex similar to that of a spire. Owing to this convergency, the lines on one side of a vertical line dividing the column, or rather a geometrical drawing or elevation of it, into two halves, instead of being parallel, are opposed to each other, like the opposite sides of an isosceles triangle; and this opposition produces correspondence.

Pediment.—In addition to what has been already said relative to this very important feature of Grecian architecture, some further remarks will not be at all superfluous. In the first place, then, the pediment proves to us most convincingly that a figure which, considered merely in itself, is generally regarded as neither beautiful nor applicable to architectural purposes, may be rendered eminently beautiful and satisfactory to the eye. Reasoning abstractedly, it would seem that if such figure is to be made use of at all, the equilateral triangle would recommend itself in preference to any other, as being obviously the most perfect and regular of all triangles. For a pediment, however, such form would be truly monstrous; and yet even the equilateral triangle, or even one of still loftier pitch, may, under some circumstances, become a pleasing architectural form, as we may perceive from pyramids and Gothic gables. How, then, is this seeming inconsistency or contradiction to be explained? It explains itself, if we merely reflect, as we ought to do, that in architecture, forms and proportions are beautiful not positively but only relatively. Were it not so, the same forms and proportions would be beautiful, and equally so under all circumstances, without any regard to purpose or propriety. It must also be taken into account that habit, custom, association of ideas, or prejudice, greatly influence our notions of architectural beauty. We are prejudiced in favour of the low Greek pediment, if for no other reason, because it is sanctioned by Greek authority and is according to Greek precedent. In all probability, had that people employed high-pitched instead of [Pg 25] low-pitched pediments, we should, without inquiring further, have admired the former rather than the latter. What we have now to inquire is, why lowness of pitch for the pediment best agrees with the Greek system and its principles. Notwithstanding that the pediment forms no part of the Order, since the latter is complete without it,—and in fact the pediment occurs only at the ends of a sloping roof,—the pediment must, when it does appear, be in accordance with the Order itself, or that front of the building which is beneath the pediment; consequently the pitch of the latter must be regulated by circumstances,—must be either greater or less, according to the proportions of the front itself. So far from being increased in the same ratio, the wider the front,—the greater the number of columns at that end of the building,—the lower must the pediment be kept, because the front itself becomes of low proportions in the same degree as it is extended or widened. Under all circumstances, the height of the pediment must remain pretty nearly the same, and be determined, not by width or horizontal extent, but by the height of what is beneath it. The height of the pediment or its tympanum (the triangular surface included between the horizontal cornice of the Order, and the two raking cornices of the pediment) never greatly exceeds the depth or height of the entablature; for were it to do so, the pediment would become too large and heavy, would take off from the importance of the Order, and appear to load its entablature with an extraneous mass which it was never calculated to bear.

We hardly need observe that it was, if not a constant, a very usual practice with the Ancients to fill in the whole of the tympanum of the pediment with sculpture, and also the metopes of the frieze, by which the latter, instead of being mere blank spaces between the triglyphs, were converted into highly ornamental features.

Of the Roman and the modern varieties of this Order we shall treat much [Pg 26] more briefly, because our remarks may be confined to comparison and the notice of differences. Certain it is that the original character of the Order was gradually lost sight of more and more, till at length it was converted into something quite different from its Greek type. The few circumstances in which Modern Doric, as we may call it, resembles the original one, are little more than the mode of fluting with arrises instead of fillets,—the general form of capital composed of echinus and abacus, and the triglyphs upon the frieze. The differences are, if not greater, far more numerous. The column becomes greatly elongated, being increased from six to eight diameters. The sunk annulets beneath the capital were omitted or converted into fillets; the capital was increased in depth by a distinct necking being given to it, divided from the shaft by a projecting moulding, which in that situation is called an astragal. The abacus, too, is made shallower, and has mouldings added to it. One of the greatest changes of all, as far as the column is concerned, is the addition of a base to it, which is partly both consequence and cause of the greater slenderness of the shaft; for were the shaft not reduced in diameter,—which is the same as being made more diameters in height,—the base added to it would enlarge the foot of the column: so again, on the other hand, were only the shaft decreased in thickness, without any mouldings for a base being added to it, that end of the column would be as much too small. The base best adapted to the Order, as being the most simple, though not uniformly made use of, is that which consists of merely a torus, or large circular and convex-sided block, and two shallow fillets above it. It may here further be noticed, that besides the base itself, or the base proper, the moderns have, for all the Orders alike, adopted an additional member, namely, a rather deep and square block, which, when so applied, is termed a plinth; and beneath this is frequently placed another and deeper one, called a sub-plinth. Contrary as this is to the practice of the Greeks, it is by no means an unwarrantable license, for had no greater liberty been taken with the [Pg 27] Orders and the modes of applying them, they would have remained comparatively quite pure. In apology for the plinth beneath a base, it may be said to produce a pleasing agreement between both extremities of the column,—in the Doric Order at least, where the square plinth beneath the circular torus of the base answers to the square abacus (which is itself another plinth, though differently named) placed upon the circular echinus of the capital.

Passing over several particulars which our confined limits will not permit us to notice, we may remark, that if greatly altered, not to say corrupted, from its primitive character, the Doric Order, as treated by the moderns, has been assimilated to the other Orders,—so much so as, though still differing from them in its details, to belong to the same general style. One advantage, if no other, of which is, that it may, should occasion require, be used along with the other Orders; whereas the original or Grecian Doric is so obstinately inflexible that it cannot be made to combine with any thing else, or to bend to modern purposes. So long as a mere portico or colonnade, and nothing more, is required, backed by a wall unperforated by windows, its character and characteristic system of intercolumniation can be kept up, but no longer; or if it is to be done, it is more than has yet been accomplished. Nothing could be more preposterous, or show greater want of proper æsthetic feeling, or greater disregard of æsthetic principles, than the attempt to combine, as was done by Nash in the Park façade of Buckingham Palace, a Grecian Doric Order with a Corinthian one. So totally irreconcileable are the two styles, that it was like placing Tudor or florid Perpendicular Gothic upon the early Lancet style. Besides, in that instance, the Doric, though affecting to be Greek, was depravated most offensively, as may still be seen in what is now left in the two low wings, the architrave and frieze being thrown together into one blank surface. [Pg 28]

This, as already stated, is not entitled to rank as a distinct Order, being, in fact, nothing more than a simplified, if not a spurious and debased variety of the Doric. No authentic examples of it exist: it is known only from what Vitruvius says of it, following whose imperfect account, modern writers and architects have endeavoured to make out something answering to it. Yet what has been so produced is to all intents and purposes Doric,—though not Grecian Doric,—excepting that the shafts are unfluted and the frieze quite plain; which last circumstance, and much more, as has just above been intimated, is a mere trifling discrepancy, since not the triglyphs merely, but the frieze may, it seems, be omitted without thereby forfeiting the character of Doric for the Order. Though the Tuscan is spoken of, it is not practised. Almost the only example of what is called by that name in this country is Inigo Jones’s portico of St. Paul’s, Covent Garden, which, though not devoid of character and effect, is remarkable chiefly [Pg 29] for the great width of the intercolumns, and the great projection of its very shallow, and therefore too shelf-like cornice, which, if no other part, must be admitted to differ widely from the comparatively slightly projecting and massive Doric cornice. The Tuscan has, however, been treated differently by different Architects, and some of them have given it what is merely a modification of the Doric cornice without its mutules. Their Tuscan becomes, in fact, very little more than a plainer sort of their own Doric, distinguished from it chiefly, and that only negatively, by the omission of triglyphs on the frieze. One thing which the Moderns have done, both in their Doric and their Tuscan, is to assimilate pilasters to columns, giving to the former precisely the same bases and capitals as the others have, and also generally diminishing their shafts in the same manner. Still all the differences here pointed out, together with many minor ones besides, do not constitute different Orders, unless they are to be multiplied by being subdivided into almost as many distinct Orders as there are varieties of one and the same class. All the Dorics and the Tuscan agree in having the echino-abacus capital. Therefore, if we want a quite different and distinct Order, we must turn, as we now do, to the voluted-capital class of columns, or that which bears the name of the [Pg 30]

How this Order originated,—what first led to the adoption of volutes as a suitable decoration for the capital,—whether they were mere decoration, or were at first intended to express some meaning,—whether they were intentionally devised for the latter purpose, or grew out of some accidental hint,—must now be entirely matter of conjecture. Of one thing we may be quite certain, that the Order as we now find it in the best and best known examples, was not struck out all at once, but must have passed through several stages till it was ultimately matured into perfection.

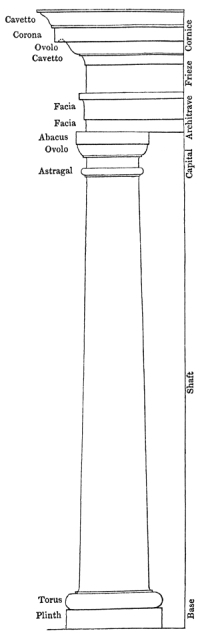

Although the capital is the indicial mark of the Order,—that by which the eye immediately recognizes and distinguishes it,—the entire column is of quite a different character from the Doric. Besides having the addition of a base, the shaft is of more slender or taller proportions, and consequently made much less visibly tapering; for if it diminished in the same degree as the Doric shaft does,—the Ionic being about two diameters longer,—the upper one would, in consequence of such tapering, become much too small; and a further consequence would [Pg 31] be that the foot and base of the column would appear much too large,—perhaps clumsily so. Not knowing expressly to the contrary, we are at liberty to suppose that it was the altered form and character of the capital itself which first led to the formation of a base or series of mouldings at the bottom of the shaft, in order to produce such degree of finish below as would correspond with and balance the richness and flow of outline given to the capital. And it must be allowed that the swelling contours of the base are admirably in keeping, and harmonize with the play of curves in the volutes; whereas, were the shaft to stand immediately upon the floor or pavement without any base, as in the Doric Order, although such treatment is in perfect correspondence with the character of that echino-abacus Order, it would be just the reverse in the voluted one. There would be a harshness and abruptness below, in grating discord with the graceful flow of lines in the capital above. This feeling dictated the necessity for a corresponding base, which, although generally spoken of as an addition to the shaft, may with far greater propriety be said to have been taken out of it. Any actual addition to the foot of the shaft would have been the same as an enlargement of it, producing disproportion, and therefore deformity. The most rational explanation therefore is, that the original diameter for the foot of the shaft was retained, but the foot itself shaped into mouldings, and the portion immediately above it pared away or reduced, so that the column became more diameters in height than before. That being done, and a distinct base so obtained, it was found necessary to make a further change, for the sharp arrises of the Doric mode of fluting occasioned a degree of harshness quite at variance with the greater delicacy aimed at in other respects. Those arrises were accordingly converted into fillets, which are not actual members, but merely spaces left between the channels or flutes themselves, which last are consequently narrower than in the Doric column; and their comparative narrowness is further [Pg 32] increased by their being augmented in number, from that of twenty to twenty-four. Thus the change from the Doric to the Ionic column may be accounted for, rationally at least, and æsthetically, if not historically. We do not, indeed, profess to know and determine the actual origin of the volutes of the capital, and therefore leave those who put faith in Vitruvius to believe, if they can, that they were derived from the imitation of the curls in a lady’s head-dress; or, as others will have it, that the idea was borrowed either from rams’ horns, or the slender and flexile twigs of trees placed upon the capital for ornament! We also leave those who are not satisfied with our way of accounting for the base given to the Ionic column to fancy that this member was intended to imitate the ancient chaussure or sandals.

The Ionic capital is far more complex than that of the Doric, and not only more complex, but more irregular also: instead of showing, like the other, four equal sides, it exhibits two faces or fronts parallel to the architrave above it, and two narrower baluster sides, as they are termed, beneath the architrave. Some consider this irregularity a defect, which, if such it be, is to be got over only by either turning the volutes diagonally, as in some Roman and modern examples, or by curving concavely the faces of the capital, instead of making them planes, so as to obtain four equal faces or sides, as is done in the capitals of the inner Order of the Temple of Apollo at Bassæ. At least that method, and the other one of turning the volutes diagonally, are the only methods that have been practised for giving perfect regularity to the Ionic capital by means of four equal faces; for, though difficult, it is possible to accomplish the same purpose differently, by making the abacus quite square, as in the Doric Order, and letting the volutes grow out of it on each side or face, their curvature commencing not on the upper horizontal edge, but descending from the vertical edges of the abacus. In fact, the volutes might be fancied to have originated in a prolonged abacus, first falling down on each side beneath the architrave, and then coiled up on the back and [Pg 33] front of the column for the two faces, which thus became greater in width; after which a smaller ornamental abacus was introduced as a crowning member, immediately beneath the architrave. As it is now treated, the great extent of the two flat voluted faces prevents the capital from being square. Let us endeavour to explain this: as average measurement, we may put down 50 minutes, or 10 less than the lower diameter, for that of the upper diameter of the shaft; 65 for the sides of the abacus; from 56 to 60 for the soffit of the architrave, which last accordingly overhangs the upper part of the shaft; and 90 minutes, that is, three modules, or a diameter and a half, for the faces of the capital, measured across the volutes. Now, were the capital square—as deep from back to front as it is wide in front—its bulk would be excessive, and out of proportion with the column and other parts of the Order, and inconsistent with the delicacy aimed at in all respects. The mere lateral expansion of the capital, on the contrary, as viewed in front, does not occasion any appearance of heaviness,—rather that of richness; more especially as the bulk is greatly diminished by the following ingenious expedient. Instead of the baluster side being made cylindrical by being kept of the same diameter throughout, and equal to the face of the volute, it is gradually diminished from each face; so that the side of the capital thus becomes in a manner hollowed out; and not only that, but great play of form is imparted to it, and its curvature both contrasts and harmonizes with the curves of the volutes themselves.

If there be not the same completeness with respect to uniformity in all the four sides as is obtained in the Doric and Corinthian capitals, at any rate the most admirable artistic contrivance and propriety are exhibited. The only thing to be objected against the Ionic capital is, that in the end columns of a portico the form of capital just described occasioned obvious if not offensive irregularity, because on the return or side of the building the baluster side showed itself beneath the face of the architrave: yet even this was of little consequence if [Pg 34] there was merely a single row of columns in front; but where the colonnade was continued along the flanks of the building also, a very unsightly sort of irregularity was produced; for while all the other columns on those flanks showed the faces of their capitals, the end one would show its baluster side. Here then a difficulty presented itself that demanded some ingenuity to overcome it; and hardly can we sufficiently admire the happy expedient by which it was surmounted. It was necessary to give the capital at the angle two adjoining voluted faces, so that it should agree with those of the other columns both in front and on the flank of the building. This was accordingly effected by placing the volute at the angle, diagonally, so as to obtain there two voluted surfaces placed immediately back to back,—a most happy and simple contrivance, which, now that it has been applied, every one is at liberty to fancy he could have found out for himself. Nevertheless it is not every one that approves of it, for there are some who affect to regard that disposition of the volute at the angle as a defect. If it be strictly considered merely in itself, it may, perhaps, be objected to such capital that in itself it is irregular, one of the volutes in each of its faces being turned obliquely and foreshortened, while the other volute in the same face is seen directly in front, as in all the other capitals. Yet surely such partial and trifling irregularity may very well be excused, instead of being imputed as a defect, since it obviates far greater irregularities, and contributes so effectively to general harmony and symmetry. At all events, it is incumbent upon those who make the objection to show how much better they could have managed matters. So far are we from objecting to it, that we do not see why the same diagonal disposition of the volutes should not, occasionally at least, be employed for all the capitals alike, thereby giving them, although in all other respects perfectly Greek as to style, four uniform faces, as in some of the Roman and Italian examples of the Order.

How little modern Architects are capable of modifying the Ionic capital, and adapting it to particular circumstances, may be seen in [Pg 35] the colonnades of the façade of the British Museum, where, at the re-entering or internal angle formed by colonnades at right angles to each other, the column at the angle has two adjoining voluted faces given to it; but as a re-entering or inner angle is circumstanced quite differently from an external one, the consequence is that each of those faces falls opposite the baluster side of the columns ranging with it either way. We explain this briefly in two simple diagrams, in which f indicates the face or voluted side of the capital, and b the baluster side. In an external angle, or the return of a portico, the faces and sides are arranged thus, so that b b b b come opposite each other; but in an internal or re-entering angle, the reverse takes place; for we have then this disposition of the faces and sides of the capitals, in which a voluted face comes opposite to the baluster side of the next capital,—a most unsightly irregularity, and one all the more unpardonable because it could have been got over, if in no other way, by converting that column (a) into a square pillar, which would besides give strength, or the expression of it, where such expression is very desirable.

If these observations on the Ionic capital seem to detain us too long, we cannot help it: they are nothing less than indispensable for a proper understanding of its nature, and the peculiarity of circumstances attending it. What remains to be observed is, that owing to its complexity, that capital admits of very great diversity of character and decoration. It is sometimes without, and sometimes has a necking to it, which may either be plain or decorated, as may best accord with the particular expression, either as to richness or quiet simplicity, which is aimed at as the characteristic of the entire design. The capital may be modified almost infinitely in its proportions; first, as regards its general proportion to the column; [Pg 36] secondly, as regards the size of the volutes compared with the width of the face. In the best Greek examples the volutes are much bolder and larger than in those of the Roman and Italian, in some of which they are so greatly reduced in size, and become consequently so far apart from each other, as to be insignificant in themselves, and give the whole capital an expression of meagreness and meanness. The spirals forming the volute supply another source of variety, since they may be either single or manifold. In what is called the Ilissus Ionic capital there is only a single spiral, or hem, whose revolutions form the volute, which mode, indeed, prevails in all the Roman and modern Ionics; but in the capitals of the Temple of Erechtheus at Athens, there are, besides that principal spiral, other intermediate ones which follow the course of its revolutions. Again, the cathetus, or eye of the volute, where the spiral or spirals terminate, admits of being made smaller or larger. It is, besides, sometimes flat, sometimes convex, and occasionally carved as a rosette. All these variations are independent of the general composition of the capital, and though not all equally good, they both suggest and authorize other modifications of the Ionic type, and fresh combinations.

One exceedingly interesting example, highly valuable as suggestive study,—one quite sui generis, and perhaps on that account viewed with more of prejudice than relish, is the internal Order of the Temple of Apollo at Bassæ, delineated and described by Mr. T. L. Donaldson, in the supplementary volume to Stuart’s ‘Athens.’ This example, which seems to have found favour only in the eyes of Mr. C. R. Cockerell, who has employed it on more than one occasion, has, as already intimated, four similar faces; yet if it so far agrees with many Roman and modern Ionic capitals, it differs from them totally in every other respect. While the faces of the latter are formed rather by merely sticking on the volutes diagonally, instead of turning them, so in the example now under notice, each face may be said to be arched, since it curves downwards on each side from the [Pg 37] middle of its upper edge, instead of being there straight or horizontal beneath the architrave. Owing to this circumstance the faces of the capital have the look of being rather affixed to than properly connected with the abacus, and there is a certain degree of incongruousness and want of finish. So far, then, there is room for improvement, and perhaps in some other respects also; yet upon the whole there is much to approve of and admire in this capital, among whose peculiarities it deserves to be noted that the space between the volutes is not above half the width of the volutes themselves. Nor is [Pg 38] it for its capital alone this that example of the Order is remarkable, its base being equally peculiar, on account of its simplicity of form, and still more so, perhaps, on account of its very great expansion, spreading out below to considerably more than two upper diameters of the shaft; which perhaps causes the capital to appear rather too small in comparison with it. This base is all the more remarkable because it differs entirely from what is called the Ionic base, although not employed by the European Greeks for that Order, who made use of what is styled the Attic base, consisting of two tori and a scotia, or deep curved hollow, between them. The proper Ionic base, or what is so called, differs from every other form of that member, being greatly contracted in its lower mouldings, which, if not a deformity, is not a particular beauty, as it gives the base too much the appearance of being reversed or turned upside down; and hence it is difficult to assign any probable or sufficient motive for such conformation of mouldings in the foot of a column. Perhaps the only modern instance of the application of that base occurs in the tetrastyle (four-columned) portico of Hanover Chapel, Regent Street, whose Order is copied from the Temple of Minerva Polias at Priene, in Asia Minor; to which example we shall presently have occasion to refer again when we come to speak of the Ionic entablature. Before so doing we have to call attention to another peculiarity in the columns within the Temple at Bassæ, whose base is above shown: we allude to the mode in which the shafts are fluted, which seems to indicate a transition from the Doric to the Ionic style, the fillets being exceedingly narrow, and the channels shallow and very slightly curved, which gives the shaft altogether a different character from that attending the usual mode of fluting practised for this Order.

Although it is a modern composition, derived from the study of Greek fragments, yet certainly not on that account the less meritorious than if it were an express copy from some one particular example, we may be [Pg 39] allowed to speak of the Order, or rather the columns of the hexastyle (six-columned) portico of the Church in Regent Square, Gray’s Inn Road, erected between twenty and thirty years ago by Mr. Inwood, soon after the completion of St. Pancras’ Church, whose portico so admirably exemplifies the florid and elaborately wrought Ionic of the Temple of Erechtheus at Athens. The columns of the Regent Square Church,—and it is on account of the columns alone that we allude to it,—differ from all other known examples; not only in their bases and capitals, but also in the very peculiar mode of fluting, or rather striating, employed for their shafts. Not having detailed drawings, or any drawings at all to assist us, we cannot pretend to enter into description, but can only say that base, shaft, and capital are unlike all received examples, and at the same time so well adapted to each other as to produce artistic unity and consistency of character; and that character is stamped by breadth and simplicity. With respect to the fluting, it partakes of what may be called striating, the fillets showing themselves rather as narrow surfaces raised upon the shaft, than the channels as positive hollows between them. The capital is at once graceful and simple, and derives much of its peculiar character from the enlarged eye of the volute, which is occupied by a rosette ornament.

Interesting as it would be to particularize other examples, we cannot do so here, which is the less to be regretted because mere verbal remarks, unaccompanied by drawings on such a scale as to fully show all their minutiæ, would not be very satisfactory. Perhaps we shall be thought to have already dwelt rather too long on the mere column, for we have not yet quite done with that part of the Order. It remains to be observed, that notwithstanding its situation is such as to render detail there hardly noticeable, the baluster side of the capital was always enriched. In Greek examples it had a series of wide channels with broad fillets between them, and where great richness was affected, as in the Ionic of the Temple of Erechtheus, the fillets had an [Pg 40] additional moulding upon them, carved into beads. In the Asiatic examples, on the contrary, and Roman ones also, the baluster side is usually cut into the form of leaves, bound together, as it were, in the centre by a broad moulded ring, which produces an exceedingly good effect; and indeed, in several instances, much better taste is manifested in that obscure part of the capital than in the face itself.

Although it is repetition to say that the base usually given to this Order by the Greeks was the Attic one, consisting of two tori, divided by a scotia, we here refer to that part of the column again for the purpose of noting a species of enrichment applied to it, the upper torus being sometimes fluted horizontally, at others cut to resemble an interlaced chain-like ornament, now called a guilloche. Modern Architects, however, invariably leave the upper torus of the base quite plain, even when they scrupulously copy every other part of the column. The only instance of channeling upon the upper torus, to which we can point, is that of the portico of St. Pancras’ Church, which building well deserves to be carefully examined and studied by those who would acquire a correct idea of the exquisite finish and richness of Grecian Ionic details, and their effect in execution.