Title: Musical Instruments [1908]

Author: Carl Engel

Release date: June 4, 2021 [eBook #65505]

Language: English

Credits: Carol Brown, Turgut Dincer and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive and the HathiTrust.)

BOARD OF EDUCATION, SOUTH KENSINGTON,

VICTORIA AND ALBERT MUSEUM.

BY

WITH SEVENTY-EIGHT ILLUSTRATIONS

REVISED EDITION.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR HIS MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE,

By WYMAN and SONS, Limited, 109, Fetter Lane, E.C.

And to be purchased, either directly or through any Bookseller, from

WYMAN and SONS, Limited, 109, Fetter Lane, Fleet Street, E.C. or

OLIVER and BOYD, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh; or

E. PONSONBY, 116, Grafton Street, Dublin.

1908.

Price 1s. 6d.; in Cloth, 2s. 3d.

In the preparation of the revised edition of the late Dr. Engel’s handbook, first published in 1875, care has been taken to make as few alterations as possible and to express no views from which he might have dissented.

The greatly enlarged chapter relating to post-mediæval instruments has been chiefly compiled from Dr. Engel’s Descriptive Catalogue of the musical instruments in the Museum, published in 1874.

The pages relating to the Ancient Egyptians have been revised by Dr. W. M. Flinders Petrie, those dealing with the Greeks, Etruscans and Romans by Dr. Cecil H. Smith, and the description of Chinese and Japanese instruments by Dr. Stephen W. Bushell. The thanks of the Board are due to these gentlemen for their valuable co-operation.

| CONTENTS. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Page | |||

| Note | iii | ||

| List of Contents | v | ||

| ” ” Illustrations | vii | ||

| Chapter | I. | —Introduction | 1 |

| ” | II. | —Pre-Historic Relics and Ancient Egyptian | 9 |

| ” | III. | —Assyrian and Hebrew | 16 |

| ” | IV. | —Greek, Etruscan and Roman | 27 |

| ” | V. | —Oriental | 37 |

| ” | VI. | —American Indian | 58 |

| ” | VII. | —European Instruments of the Middle Ages | 83 |

| ” | VIII. | —European Instruments of the Middle Ages | 92 |

| ” | IX. | —European Instruments of the Middle Ages | 99 |

| ” | X. | —Post-Mediæval Instruments | 104 |

| Appendix | 135 | ||

| Index | 139 | ||

| LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fig. | Page. | ||

| 1.— | Music, after an oil painting attributed to Melozzo da Forlì (1438-1494) | Frontispiece | |

| 2.— | Painted Wooden Harp. Ancient Egyptian. XVIIIth dynasty (B.C. 1450) | Facing | 10 |

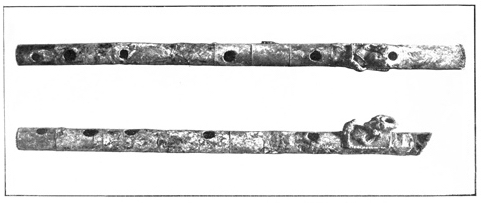

| 3.— | Bronze and Reed Flutes. Ancient Egyptian. B.C. 600, or later | Facing | 12 |

| 4.— | Bronze Sistra. Ancient Egyptian. XXIInd-XXVIth dynasty (B.C. 1000-600) | Facing | 14 |

| 5.— | Series of Bells. Ancient Egyptian. Late Period | 15 | |

| 6.— | A Muse with a Harp, and two others with Lyres. From a Greek vase | 29 | |

| 7.— | Pair of Bronze Flutes, with mouthpiece in the form of a bust of a Mænad holding a bunch of grapes. Greek | Facing | 30 |

| 8.— | A Muse Playing the Diaulos. Greek | 31 | |

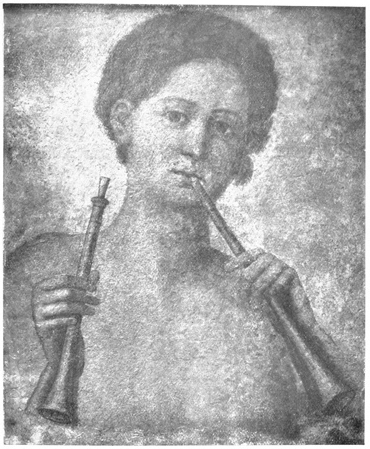

| 9.— | Wall Painting of a youth wearing a myrtle wreath and playing on the Double Pipes. Said to have been found in a columbarium in the Vigna Ammendola on the Appian Way near Rome, about 1823. British Museum | Facing | 34 |

| 10.— | Tuba, Cornu and Lituus. Roman | 35 | |

| 11.— | Hsüan. Chinese | 42 | |

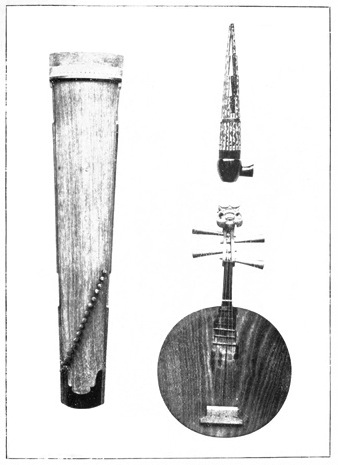

| 12.— | (a) Ch’in (a species of Lute). Modern Chinese | ||

| (b) Shêng (Mouth Organ). Chinese. 19th century | |||

| (c) Yueh-ch’in (Moon Guitar). Chinese. 19th century | Facing | 42 | |

| 13.— | (a) Koto (a species of Lute). Japanese. 19th century | ||

| (b) Biwa (a species of Guitar). Modern Japanese | |||

| (c) Sâmisen. Japanese | Facing | 44 | |

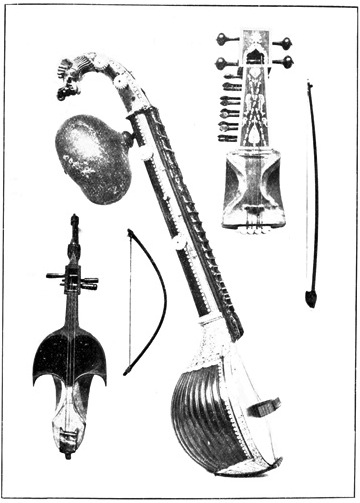

| 14.— | (a) Sârinda and Bow. Indian (Bengal). 19th century | ||

| (b) Rudra Vina. Southern Indian (Madras). 19th century | |||

| (c) Sârangi and Bow. Southern Indian. 19th century | Facing | 48 | |

| 15.— | (a) Kemángeh or Sitâra or Fiddle. Persian. About 1800 | ||

| (b) Nuy (Flute). Persian. 19th century | |||

| (c) Santir (Dulcimer) Case. Persian | Facing | 54 | |

| 16.— | Pottery Whistles, with finger-holes. Ancient Mexican | 59 viii | |

| 17.— | Pottery Flageolets, with finger-holes. (a) and (c) Ancient Mexican; (b) from the Island of Sacrificios | Facing | 60 |

| 18.— | Bone Flutes. Ancient Peruvian, (a) and (b) Truxillo; (c) Lima | Facing | 60 |

| 19.— | Huayra-puhura, discovered in a Peruvian tomb | 64 | |

| 20.— | Wooden Trumpet. Used by Indians near the Orinoco | 65 | |

| 21.— | Juruparis, with and without cover. South American | 66 | |

| 22.— | Botuto. Used by Indians near the Orinoco | 68 | |

| 23.— | Cithara. From a 9th century MS. formerly in the monastery of St. Blasius in the Black Forest | 84 | |

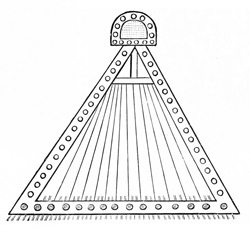

| 24.— | Psalterium. From a 9th century MS. formerly in the monastery of St. Blasius in the Black Forest | 85 | |

| 25.— | Cithara. From a 9th century MS. formerly in the monastery of St. Blasius in the Black Forest | 85 | |

| 26.— | King playing Psaltery. After an engraving in N. X. Willemin’s Monuments Français Inédits, Vol. I., pl. 19, taken from Hortus Deliciarum, a MS. of the 12th century | 86 | |

| 27.— | Nablum. From a 9th century MS. at Angers | 86 | |

| 28.— | Female playing a Species of Citole. From a 9th century MS. formerly in the monastery of St. Blasius in the Black Forest | 86 | |

| 29.— | Harp. From a 9th century MS. formerly in the monastery of St. Blasius in the Black Forest | 87 | |

| 30.— | Crwth. Welsh. 18th century | Facing | 90 |

| 31.— | Organistrum | 93 | |

| 32.— | Sackbut | 94 | |

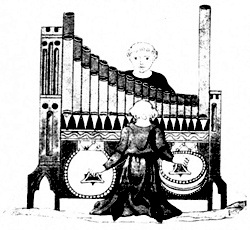

| 33.— | Organ. From a 12th century psalter in the library of Trinity College, Cambridge | 95 | |

| 34.— | Organ (Grand Orgue). After an engraving in N. X. Willemin’s Monuments Français Inédits | 96 | |

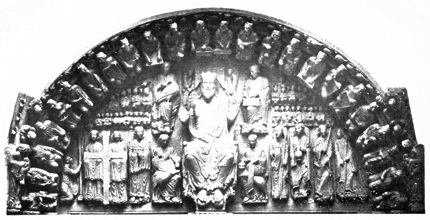

| 35.— | Bas-relief, representing a group of musicians, formerly at the abbey of St. Georges de Boscherville. Late 11th century (?). After an engraving in N. X. Willemin’s Monuments Français Inédits | Facing | 98 |

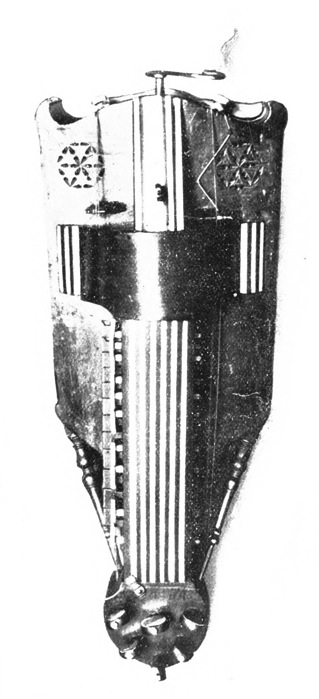

| 36.— | Hurdy-Gurdy (Vielle). With arms of France and crowned monogram of Henry II. on back and front. About 1550 | Facing | 100 |

| 37.— | Tympanum of the Glory Gate of the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostella. Dated 1188. From a plaster cast in the Victoria and Albert Museum | Facing | 100 |

| 38.— | Minstrel Gallery, Exeter Cathedral. 14th century. From a plaster cast in the Victoria and Albert Museum | Facing | 102 |

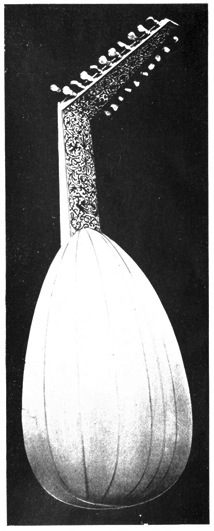

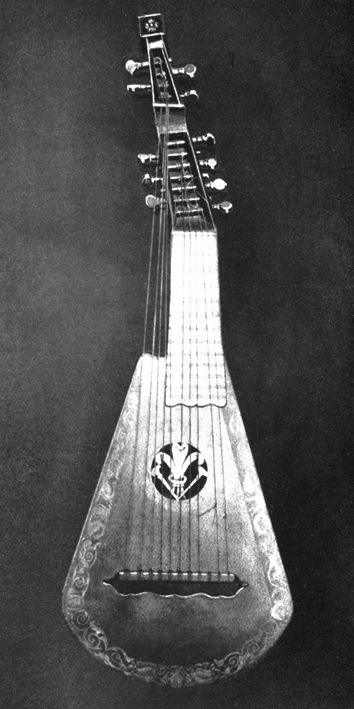

| 39.— | Lute. Italian (Venetian). Beginning of the 17th century | Facing | 104 ix |

| 40.— | Angel Playing a Lute. After an oil painting by Ambrogio da Predis. Late 15th century | Facing | 104 |

| 41.— | Archlute. Inscribed “Rauche in Chandos Street, London, 1762" | Facing | 104 |

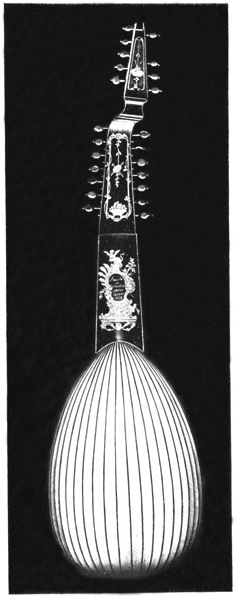

| 42.— | Chitarrone. Italian. Made by Buchenberg in Rome, anno 1614 | Facing | 106 |

| 43.— | Pandurina. French. Second half of 16th century | Facing | 108 |

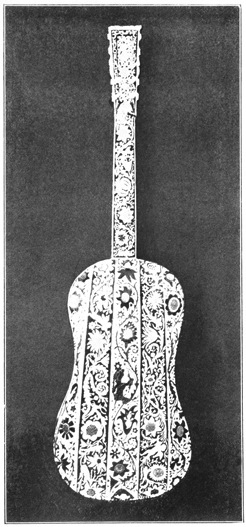

| 44.— | Guitar. French (?). 17th century | Facing | 108 |

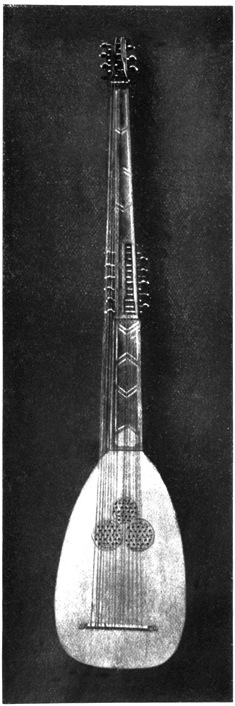

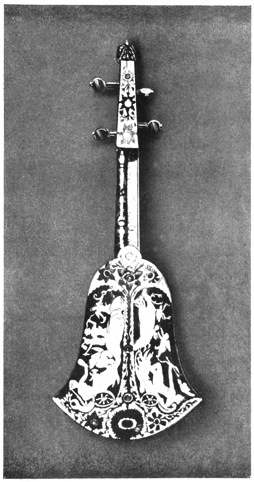

| 45.— | Quinterna, or Chiterna. German. Dated 1539 | Facing | 108 |

| 46.— | Cither. German. End of 17th century | Facing | 108 |

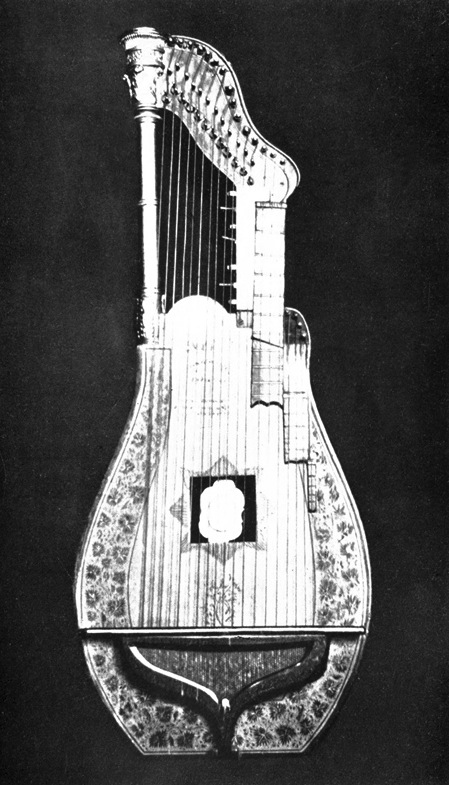

| 47.— | Harp Theorbo. Made by Harley. English. About 1800 | Facing | 110 |

| 48.— | Harp Ventura. English. Early 19th century | Facing | 110 |

| 49.— | Banduria. English. Early 19th century | Facing | 110 |

| 50.— | Harp. Old Irish | Facing | 110 |

| 51.— | Harp. French. About 1770 | Facing | 112 |

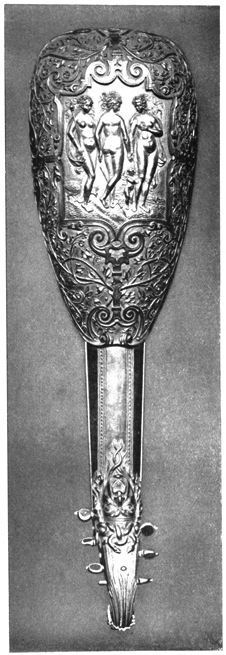

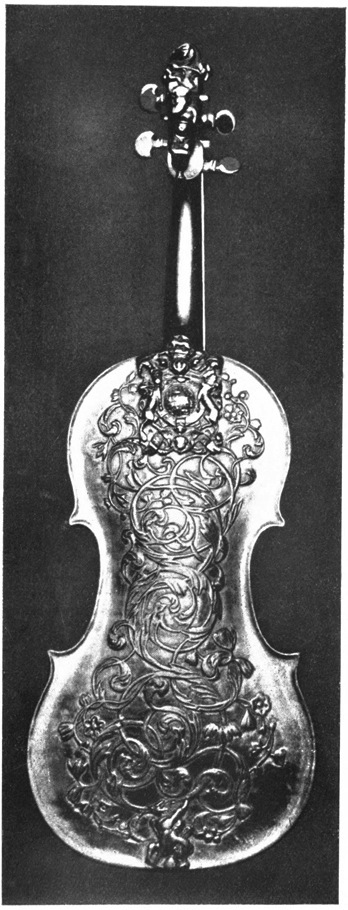

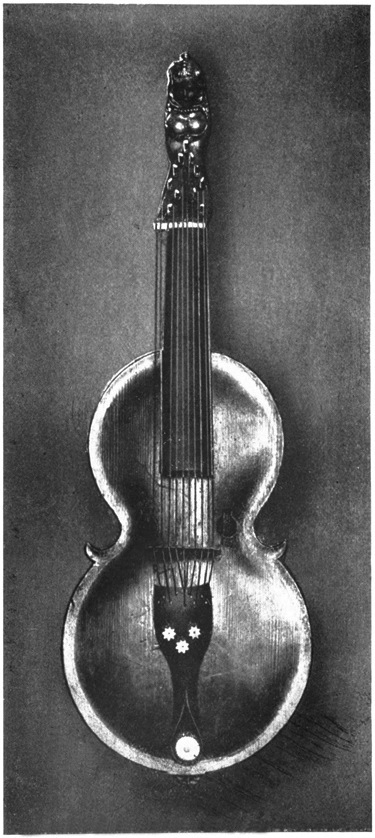

| 52.— | Violin. Said to have belonged to James I. English. Early 17th century | Facing | 112 |

| 53.— | Angel Playing a Viol. After an oil painting by Ambrogio da Predis. Late 15th century | Facing | 104 |

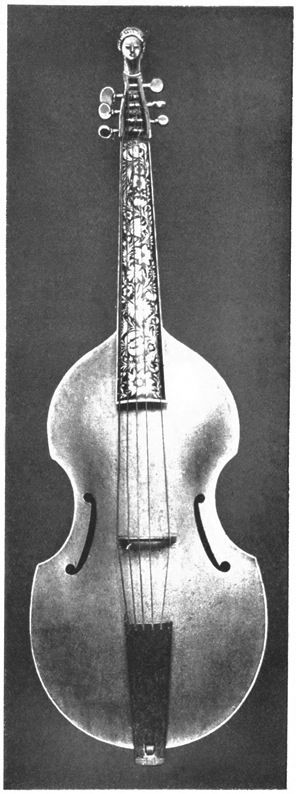

| 54.— | Viola da Gamba. Italian. About 1600 | Facing | 114 |

| 55.— | Viola da Gamba. Italian. 17th century | Facing | 114 |

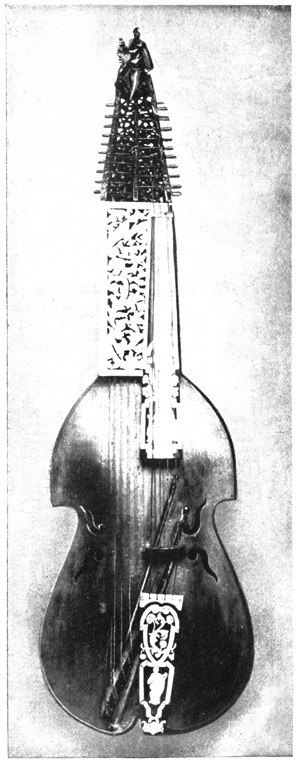

| 56.— | Viola di Bardone, or Bariton, with Bow. German. 17th century | Facing | 114 |

| 57.— | Viola d’Amore. Probably English. Late 17th century | Facing | 116 |

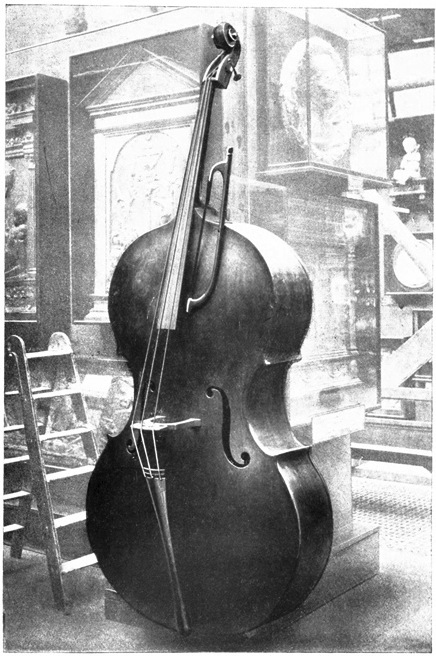

| 58.— | Double-Bass, with Bow. Known as “The Giant.” Italian. 17th century | Facing | 116 |

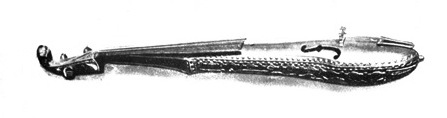

| 59.— | Sordino, or Pochette. Probably German. Late 17th or early 18th century | Facing | 118 |

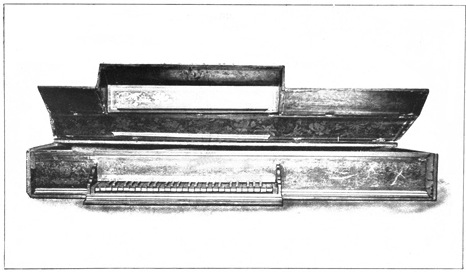

| 60.— | Bûche, or Scheitholz. Made by Fleurot, of the Val d’Ajol in the Vosges Mountains. Early 19th century | Facing | 118 |

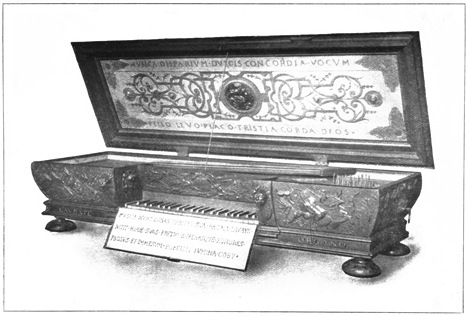

| 61.— | Virginal. Formerly belonging to Queen Elizabeth. Italian. Second half of 16th century | Facing | 118 |

| 62.— | Virginal. Flemish. Second half of 16th century | Facing | 118 |

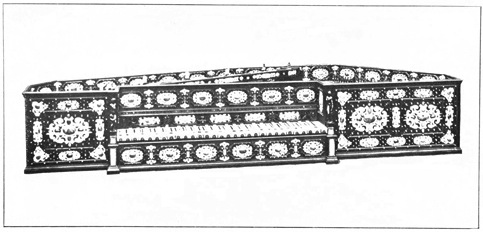

| 63.— | Spinet. Made by Annibale dei Rossi of Milan. Italian. Dated 1577 | Facing | 120 |

| 64.— | Spinet. Signed “Johannes Player fecit” English. About 1700 | Facing | 120 |

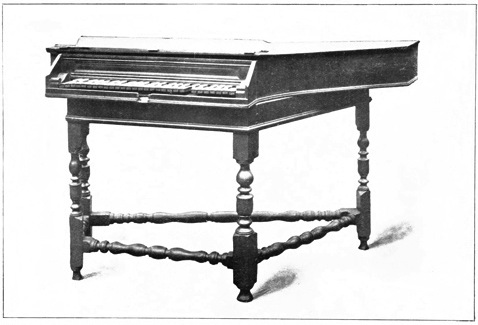

| 65.— | Clavichord. Inscribed “Barthold Fritz fecit, Braunschweig, anno 1751.” German. 18th century | Facing | 120 |

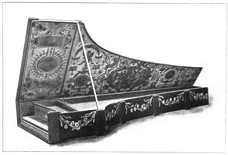

| 66.— | Clavicembalo. Signed “Joanes Antonius Baffo, Venetus.” Italian. Dated 1574 | Facing | 122 x |

| 67.— | Clavecin. Made by Pascal Taskin of Paris. French. Dated 1786 | Facing | 124 |

| 68.— | Organ-Harpsichord, or Claviorganum. Formerly in the chapel of Ightham Mote, near Sevenoaks, Kent. Probably English | Facing | 124 |

| 69.— | Triple Flageolet. Italian. About 1820 | Facing | 124 |

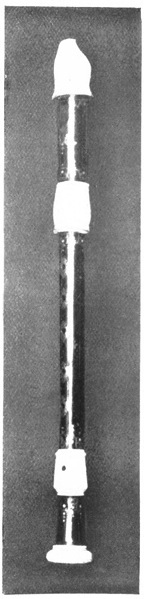

| 70.— | Flauto Dolce, or Flute. Ivory. Inscribed “Anciuti a Milan, 1740" | Facing | 124 |

| 71.— | Flageolet. Italian. Middle of 18th century | Facing | 126 |

| 72.— | Oboe. Made by Anciuti of Milan. Formerly in the possession of the composer Rossini. Latter half of 18th century | Facing | 126 |

| 73.— | Bassoon, species of. English. Late 18th, or early 19th century | Facing | 128 |

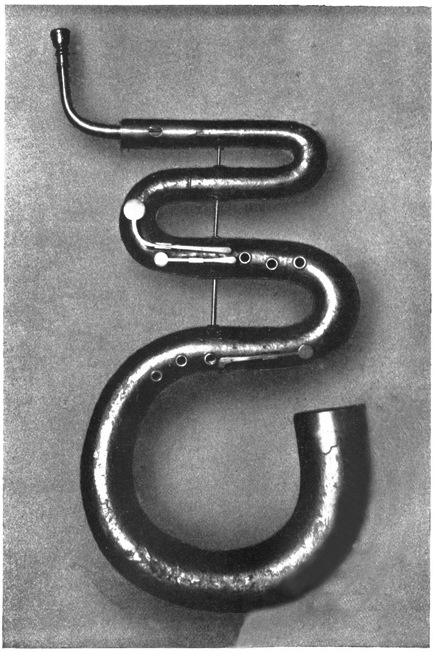

| 74.— | The Serpent. Made by Gerock Wolf, in London. English. Early 19th century | Facing | 128 |

| 75.— | Serinette or Bird Organ. French. Period of Louis XIV. | Facing | 128 |

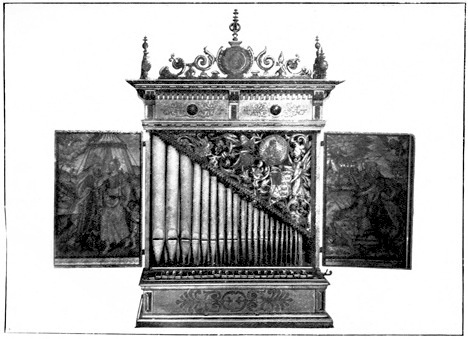

| 76.— | Organ (Positive). German. Dated 1627 | Facing | 128 |

| 77.— | Bagpipes. English. 18th century | Facing | 130 |

| 78.— | Handel’s Harpsichord. Made by Andreas Ruckers, of Antwerp, 1651 | Facing | 134 |

Music, in however primitive a stage of development it may be with some nations, is universally appreciated as one of the Fine Arts. The origin of vocal music may have been coeval with that of language; and the construction of musical instruments evidently dates with the earliest inventions which suggested themselves to human ingenuity. There exist even at the present day some savage tribes in Australia and South America who, although they have no more than the five first numerals in their language and are thereby unable to count the fingers of both hands together, nevertheless possess musical instruments of their own contrivance, with which they accompany their songs and dances.

Wood, metal, and the hide of animals are the most common substances used in the construction of musical instruments. In tropical countries bamboo or some similar kind of cane and gourds are especially made use of for this purpose. The ingenuity of man has contrived to employ in producing music, horn, bone, glass, pottery, slabs of sonorous stone—in fact, almost all vibrating matter. The strings of instruments have been made of the hair of animals, of silk, the runners of creeping plants, the fibrous roots of certain trees, of cane, catgut (which, absurdly referred to the cat, is from the sheep, goat, lamb, camel, and some other animals), metal, etc.

2 The mode in which individual nations or tribes are in the habit of embellishing their musical instruments is sometimes as characteristic as it is singular. The negroes in several districts of Western Africa affix to their drums human skulls. A war-trumpet of the king of Ashantee which was brought to England is surrounded by human jawbones. The Maoris in New Zealand carve around the mouth-hole of their trumpets a figure intended, it is said, to represent female lips. The materials for ornamentation chiefly employed by savages are bright colours, beads, shells, grasses, the bark of trees, feathers, stones, gilding, pieces of looking-glass inlaid like mosaic, etc. Uncivilised nations are sure to consider anything which is bright and glittering ornamental, especially if it is also scarce. Captain Tuckey saw in Congo a negro instrument which was ornamented with part of the broken frame of a looking-glass, to which were affixed in a semicircle a number of brass buttons with the head of Louis XVI.. on them,—perhaps a relic of some French sailor drowned near the coast years ago.

Again, musical instruments are not infrequently formed in the shape of certain animals. Thus, a kind of harmonicon of the Chinese represents the figure of a crouching tiger. The Burmese possess a stringed instrument in the shape of an alligator. Even more grotesque are the imitations of various beasts adopted by the Javanese. The natives of New Guinea have a singularly shaped drum, terminating in the head of a reptile. A wooden rattle like a bird is a favourite instrument of the Indians of Nootka Sound. In short, not only the inner construction of the instruments and their peculiar quality of sound exhibit in most nations certain distinctive characteristics, but it is also in great measure true as to their outward appearance.

An arrangement of the various kinds of musical instruments 3 in a regular order, beginning with that kind which is the most universally known, and progressing gradually to the least usual, gives the following results. Instruments of percussion of indefinite sonorousness or, in other words, pulsatile instruments which have not a sound of a fixed pitch, as the drum, rattle, castanets, etc., are most universal. Wind instruments of the flute kind—including pipes, whistles, flutes, Pandean pipes, etc.—are also to be found almost everywhere.

Much the same is the case with wind instruments of the trumpet kind. These are often made of the horns, bones, and tusks of animals; frequently of vegetable substances and of metal. Instruments of percussion of definite sonorousness are chiefly met with in China, Japan, Burmah, Siam, and Java. They not infrequently contain a series of tones produced by slabs of wood or metal, which are beaten with a sort of hammer, as our harmonicon is played.

Stringed instruments without a finger board, or any similar contrivance which enables the performer to produce a number of different tones on one string, are generally found among nations whose musical accomplishments have emerged from the earliest state of infancy. The strings are twanged with the fingers or with a piece of wood, horn, metal, or any other suitable substance serving as a plectrum; or are made to vibrate by being beaten with a hammer, as our dulcimer. Stringed instruments provided with a finger-board on which different tones are producible on one string by the performer shortening it more or less—as on the guitar and violin—are met with almost exclusively among nations in a somewhat advanced stage of musical progress. Such as are played with a bow are the least common; they are, however, known to the Chinese, Japanese, Hindus, Persians, Arabs, and a few other nations, besides those of Europe and their descendants in other countries.

4 Wind instruments of the organ kind—i.e., such as are constructed of a number of tubes which can be sounded together by means of a common mouthpiece or some similar contrivance, and upon which therefore chords and combinations of chords, or harmony, can be produced—are comparatively of rare occurrence. Some interesting specimens of them exist in China, Japan, Laos, and Siam.

Besides these various kinds of sound-producing means employed in musical performances, a few others less widely diffused could be pointed out, which are of a construction not represented in any of our well-known European specimens. For instance, some nations have peculiar instruments of friction, which can hardly be classed with our instruments of percussion. Again, there are contrivances in which a number of strings are caused to vibrate by a current of air much as is the case with the Æolian harp; which might with equal propriety be considered either as stringed instruments or as wind instruments. In short, our usual classification of all the various species into three distinct divisions, viz., Stringed Instruments, Wind Instruments, and Instruments of Percussion, is not tenable if we extend our researches over the whole globe.

The collection at South Kensington contains several foreign instruments which cannot fail to prove interesting to the musician. Recent investigations have more and more elicited the fact that the music of every nation exhibits some distinctive characteristics which may afford valuable hints to a composer or performer. A familiarity with the popular songs of different countries is advisable on account of the remarkable originality of the airs; these mostly spring from the heart. Hence the natural and true expression, the delightful health and vigour by which they are generally distinguished. Our more artificial compositions are, on the 5 other hand, not infrequently deficient in these charms, because they often emanate from the lingers or the pen rather than from the heart. Howbeit, the predominance of expressive melody and effective rhythm over harmonious combinations, so usual in the popular compositions of various nations, would alone suffice to recommend them to the careful attention of our modern musicians. The same may be said with regard to the surprising variety in construction and in manner of expression prevailing in the popular songs and dance-tunes of different countries. Indeed, every nation’s musical effusions exhibit a character peculiarly their own, with which the musician would find it advantageous to familiarise himself.

Now, it will easily be understood that an acquaintance with the musical instruments of a nation conveys a more correct idea than could otherwise be obtained of the characteristic features of the nation’s musical compositions. Furthermore, in many instances the construction of the instruments reveals to us the nature of the musical intervals, scales, modulations, and suchlike noteworthy facts. True, inquiries like these have hitherto not received from musicians the attention which they deserve. The adepts in most other arts are in this respect in advance. They are convinced that useful information may be gathered by investigating the productions even of uncivilised nations, and by thus tracing the gradual progress of an art from its primitive infancy to its highest degree of development.

Again, from an examination of the musical instruments of foreign nations we may derive valuable hints for the improvement of our own; or even for the invention of new. Several principles of construction have thus been adopted by us from eastern nations. For instance, the free reed used in the harmonium is an importation from China. The organ builder 6 Kratzenstein, who lived in St. Petersburg during the reign of Catherine II., happened to see the Chinese instrument cheng, which is of this construction, and it suggested to him, about the end of the 18th century, to apply the free reed to certain organ stops. At the present day instruments of the harmonium class have become such universal favourites in western Europe as almost to compete with the pianoforte.

Several other well-authenticated instances could be cited in which one instrument has suggested the construction of another of a superior kind. The prototype of our pianoforte was evidently the dulcimer, known at an early time to the Arabs and Persians, who call it santir. One of the old names given to the dulcimer by European nations is cimbal. The Poles at the present day call it cymbaly, and the Magyars in Hungary cimbalom. The clavicembalo, the predecessor of the pianoforte, was in fact nothing but a cembalo with a key board attached to it; and some of the old clavicembali still preserved, exhibit the trapezium shape, the round hole in the middle of the sound-board, and other peculiarities of the first dulcimer. Again, the gradual development of the dulcimer from a rude contrivance, consisting merely of a wooden board across which a few strings are stretched, is distinctly traceable by a reference to the musical instruments of nations in different stages of civilisation. The same is the case with our highly perfected harp, of which curious specimens, representing the instrument in its most primitive condition, are still to be found among several barbarous tribes. We might perhaps infer from its shape that it originally consisted of nothing more than an elastic stick bent by a string. The Damaras, a native tribe of South-western Africa, actually use their bow occasionally as a musical instrument when they are not engaged in war or in the chase. They tighten the string nearly in the middle by means of a leathern 7 thong, whereby they obtain two distinct sounds, which, for want of a sound board, are of course very weak and scarcely audible to anyone but the performer. Some neighbouring tribes, however, possess a musical instrument very similar in appearance to the bow, to which they attach a gourd, hollowed and open at the top, which serves as a sound-board. Again, other African tribes have a similar instrument, superior in construction only inasmuch as it contains more than one string, and is provided with a sound-board consisting of a suitable piece of sonorous wood. In short, the more improved we find these contrivances the closer they approach our harp. And it could be shown, if this were requisite for our present purpose, that much the same gradual progress towards perfection, which we observe in the African harp, is traceable in the harps of several nations in different parts of the world.

Moreover, a collection of musical instruments deserves the attention of the ethnologist as much as of the musician. Indeed, this may be asserted of national music in general; for it gives us an insight into the heart of man, reveals to us the feelings and predilections of different races on the globe, and affords us a clue to the natural affinity which exists between different families of men. Again, a collection must prove interesting in a historical point of view. Scholars will find among old instruments specimens which were in common use in England at the time of Queen Elizabeth, and which are not unfrequently mentioned in the literature of that period. In many instances the passages in which allusion is made to them can hardly be understood, if we are unacquainted with the shape and construction of the instruments. Furthermore, these relics of bygone times bring before our eyes the manners and customs of our forefathers, and assist us in understanding them correctly.

8 It will be seen that the modification which our orchestra has undergone, in the course of scarcely more than a century, is great indeed. Most of the instruments which were highly popular about a hundred years ago have either fallen into disuse or are now so much altered that they may almost be considered as new inventions. Among Asiatic nations, on the other hand, we meet with several instruments which have retained unchanged through many centuries their old construction and outward appearance. At South Kensington may be seen instruments still in use in Egypt and western Asia, precisely like specimens represented on monuments dating from a period of three thousand years ago. By a reference to the Eastern instruments of the present time we obtain therefore a key for investigating the earlier Egyptian and Assyrian representations of musical performances; and likewise, for appreciating more exactly the biblical records respecting the music of the Hebrews. Perhaps these evidences will convey to some inquirers a less high opinion than they have hitherto entertained, regarding the musical accomplishments of the Hebrew bands in the solemn processions of King David or in Solomon’s temple; but the opinion will be all the nearer to the truth.

There is another point of interest about such collections, and especially that at South Kensington, which must not be left unnoticed. Several instruments are remarkable on account of their elegant shape and tasteful ornamentation. This is particularly the case with some specimens from Asiatic countries. The beautiful designs with which they are embellished may afford valuable patterns for study and for adoption in works of art.

A really complete account of all the musical instruments from the earliest time known to us would require much more space than can here be afforded. We can attempt only a concise historical survey. We venture to hope that the illustrations interspersed throughout the text will to the intelligent reader elucidate many facts which, for the reason stated, are touched upon but cursorily.

Pre-Historic Relics.

A musical relic has been exhumed in the department of Dordogne in France, which was constructed in an age when the fauna of France included the reindeer, the rhinoceros and the mammoth, the hyæna, the bear, and the cave-lion. It is a small bone somewhat less than two inches in length, in which is a hole, evidently bored by means of one of the little flint knives which men used before acquaintance with the employment of metal for tools and weapons.[1] Many of these flints were found in the same place with the bones. Only about half a dozen of the bones, of which a considerable number have been exhumed, possess the artificial hole.

M. Lartet surmises the perforated bone to have been used as a whistle in hunting animals. It is the first digital phalanx of a ruminant, drilled to a certain depth by a smooth cylindrical bore on its lower surface near the expanded upper articulation. On applying it to the lower lip and blowing into it a shrill sound is yielded. Three of these phalanges are 10 of reindeer, one is of chamois. Again, among the relics which have been brought to light from the cave of Lombrive, in the department of Ariège, occur several eye-teeth of the dog, which have a hole drilled into them near the root. Probably they also yield sounds, like those reindeer bones, or like the tube of a key. Another whistle—or rather a pipe, for it has three finger-holes by means of which different tones could be produced—was found in a burying-place, dating from the stone period, in the vicinity of Poitiers in France; it is rudely constructed from a fragment of stag’s horn. It is blown at the end, like a flûte à bec, and the three-finger holes are placed equidistantly. Four distinct tones must have been easily obtainable on it: the lowest, when all the finger-holes were covered; the other three, by opening the finger-holes successively. From the character of the stone utensils and weapons discovered with this pipe it is conjectured that the burying-place from which it was exhumed dates from the latest time of the stone age. Therefore, however old it may be, it is a more recent contrivance than the reindeer-bone whistle from the cavern of the Dordogne.

The Ancient Egyptians.

The most ancient nations historically known possessed musical instruments which, though in acoustic construction greatly inferior to our own, exhibit a degree of perfection which could have been attained only after a long period of cultivation. Many tribes of the present day have not yet reached this stage of musical progress.

11As regards the instruments of the ancient Egyptians we now possess perhaps more detailed information than of those appertaining to any other nation of antiquity. This information we owe especially to the exactness with which the instruments are depicted in sculptures and paintings[2] . Whoever has examined these interesting monuments with even ordinary care cannot but be convinced that the representations which they exhibit are faithful transcripts from life. Moreover, if there remained any doubt respecting the accuracy of the representations of the musical instruments it might be dispelled by existing evidence. Several specimens have been discovered in tombs, preserved in a more or less perfect condition.

The Egyptians possessed various kinds of harps, some of which were elegantly shaped and tastefully ornamented. The largest were about 6½ feet high; and the small ones frequently had some sort of stand which enabled the performer to play upon the instrument while standing. The name of the harp was bene. Its frame had no front pillar; the tension of the strings therefore cannot have been anything like so strong as on our present harp. (Fig. 2.)

The Egyptian harps most remarkable for elegance of form and elaborate decoration are the two which were first noticed by Bruce who found them painted in fresco on the walls of a sepulchre at Thebes, supposed to be the tomb of Rameses III. who reigned about 1170 B.C. Bruce’s discovery created a sensation among musicians. The fact that at so remote an age the Egyptians should have possessed harps which vie with our own in elegance and beauty of form appeared to some so incredible that the correctness of Bruce’s representations, as engraved in his “Travels,” was greatly doubted. Sketches of the same harps, taken subsequently and at different times from the frescoes, have since been published, but they differ more or less from each other in appearance and in the number of strings. A kind of triangular harp of the Egyptians was 12 discovered in a well-preserved condition and is now deposited in the Louvre. It has twenty-one strings; a greater number than is generally represented on the monuments. All these instruments, however much they differed from each other in form, had one peculiarity in common, namely the absence of the fore pillar.

The nefer, a kind of guitar, was almost identical in construction with the Tamboura at the present day in use among several eastern nations. It was evidently a great favourite with the ancient Egyptians, and occurs in representations of concerts dating earlier than from B.C. 1500. The nefer affords the best proof that the Egyptians had made considerable progress in music at a very early age; since it shows that they understood how to produce on a few strings, by means of the finger-board, a greater number of notes than were obtainable even on their harps. The instrument had two or four strings, was played with a plectrum and appears to have been sometimes, if not always, provided with frets. In the British Museum is a fragment of a fresco obtained from a tomb at Thebes, on which two female performers on the nefer are represented. The painter has distinctly indicated the frets.

Small pipes or flutes of the Egyptians have been discovered, made of reed, with three, four, five, or more finger-holes. There are some interesting examples in the British Museum; one of which has seven holes burnt in at the side (Fig. 3). Two straws were found with it of nearly the same length as the pipe, which is about one foot long. In some other pipes pieces of a kind of thick straw have also been found inserted into the tube, obviously serving for a similar purpose as the reed in our oboe or clarionet.

13The sebȧ, a single flute, was of considerable length, and the performer appears to have been obliged to extend his arms almost at full length in order to reach the furthest finger-hole. As sebȧ is also the name of the leg-bone (like the Latin tibia) it may be supposed that the Egyptian flute was originally made of bone. Those, however, which have been found are of wood or reed.

A flute-concert is painted on one of the tombs in the pyramids of Gizeh and dates, according to Lepsius, from an age earlier than B.C. 2000. Eight musicians are performing on flutes. Three of them, one behind the other, are kneeling and holding their flutes in exactly the same manner. Facing these are three others, in a precisely similar position. A seventh is sitting on the ground to the left of the six, with his back turned towards them, but also in the act of blowing his flute, like the others. An eighth is standing at the right side of the group with his face turned towards them, holding his flute before him with both hands, as if he were going to put it to his mouth, or had just left off playing. He is clothed, while the others have only a narrow girdle round their loins. Perhaps he is the director of this singular band, or the solo performer who is waiting for the termination of the tutti before renewing his part of the performance. The division of the players into two sets, facing each other, suggests the possibility that the instruments were classed somewhat like the first and second violins, or the flauto primo and flauto secondo of our orchestras. The occasional employment of the interval of the third, or the fifth, as accompaniment to the melody, is not unusual even with nations less advanced in music than were the ancient Egyptians.

The Double-Pipe, called mam, appears to have been a very popular instrument, if we judge from the frequency of its occurrence in the representations of musical performances. Furthermore, the Egyptians had, as far as is known to us, 14 two kinds of trumpets; three kinds of tambourines, or little hand drums; three kinds of drums, chiefly barrel-shaped; and various kinds of gongs, bells, cymbals, and castanets. The trumpet appears to have been usually of brass. A peculiar wind-instrument, somewhat the shape of a champagne bottle and perhaps made of pottery or wood, also occurs in the representations transmitted to us.

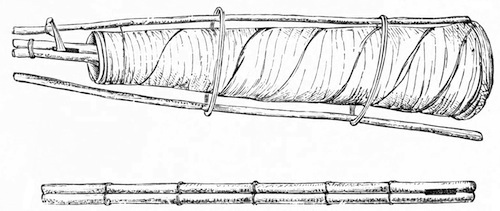

The Egyptian drum was from two to three feet in length, covered with parchment at both ends and braced by cords. The performer carried it before him, generally by means of a band over his shoulder, while he was heating it with his hands on both ends. Of another kind of drum an actual specimen has been found in the excavations made in the year 1823 at Thebes. It was 1½ feet high and 2 feet broad, and had cords for bracing it. A piece of catgut encircled each end of the drum, being wound round each cord, by means of which the cords could be tightened or slackened at pleasure by pushing the two hands of catgut towards or from each other. It was beaten with two drumsticks slightly bent. The Egyptians had also straight drumsticks with a handle, and a knob at the end. The Berlin museum possesses some of these. The third kind of drum was almost identical with the darabuka of the modern Egyptians. The Tambourine was either round, like that which is at the present time in use in Europe as well as in the east; or it was of an oblong square shape, slightly incurved on the four sides.

15The Sistrum consisted of a frame of bronze into which three or four metal bars were loosely inserted, so as to produce a jingling noise when the instrument was shaken. (Fig. 4.) The bars were often made in the form of snakes, or they terminated in the head of a goose. Not unfrequently a few metal rings were strung on the bars, to increase the noise. The frame was sometimes ornamented with the figure of a cat. The largest sistra which have been found are about eighteen inches in length, and the smallest about nine inches. The sistrum was principally used by females in religious performances. Its Egyptian name was seshesh.

The Egyptian cymbals closely resembled our own in shape. There are several pairs of them in the British museum. One pair was found in a coffin enclosing the mummy of a sacred musician, and is deposited in the same case with the mummy and coffin. Among the Egyptian antiquities in the British museum are also several small bells of bronze (Fig. 5). The largest is 2¼ inches in height, and the smallest three-quarters of an inch. Some of them have a hole at the side near the top wherein the clapper was fastened.

The Assyrians.

Our acquaintance with the Assyrian instruments has been derived almost entirely from the famous bas-reliefs which have been excavated from the mounds of Nimroud, Khorsabad, and Kouyunjik (the site of the ancient Nineveh), situated near the river Tigris in the vicinity of the town of Mosul in Asiatic Turkey.

The Assyrian harp was about four feet high, and appears of larger size than it actually was on account of the ornamental appendages which were affixed to the lower part of its frame. It must have been but light in weight, since we find it not unfrequently represented in the hands of persons who are playing upon it while they are dancing. Like all the Oriental harps, modern as well as ancient, it was not provided with a front pillar. The upper portion of the frame contained the sound-holes, somewhat in the shape of an hourglass. Below them were the screws, or tuning-pegs, arranged in regular order. The strings were perhaps made of silk, like those which the Burmese use at the present time on their harps; or they may have been of catgut, which was used by the ancient Egyptians.

The largest assemblage of Assyrian musicians which has been discovered on any monument consists of eleven performers upon instruments, besides a chorus of singers. The first musician—probably the leader of the band, as he marches alone at the head of the procession—is playing upon a harp. 17 Behind him are two men; one with a dulcimer and the other with a double-pipe; then follow two men with harps. Next come six female musicians, four of whom are playing upon harps, while one is blowing a double-pipe and another is beating a small hand-drum covered only at the top. Close behind the instrumental performers are the singers, consisting of a chorus of females and children. They are clapping their hands in time with the music, and some of the musicians are dancing to the measure. One of the female singers is holding her hand to her throat in the same manner as the women in Syria, Arabia, and Persia are in the habit of doing at the present day when producing, on festive occasions, those peculiarly shrill sounds of rejoicing which have been repeatedly noticed by travellers.

The dulcimer is in too imperfect a state on the bas-relief to familiarize us with its construction. The slab representing the procession in which it occurs has been injured; the defect which extended over a portion of the dulcimer has been repaired, and it cannot be said that in repairing it much musical knowledge has been evinced.

The instrument of the Trigonon species was held horizontally, and was twanged with a rather long plectrum slightly bent at the end at which it was held by the performer. It is of frequent occurrence on the bas-reliefs. A number of them appear to have been generally played together. At any rate, we find almost invariably on the monuments two together, evidently implying “more than one,” “a number.” The left hand of the performer seems to have been occupied in checking the vibration of the strings when its discontinuance was required. From the position of the strings the performer could not have struck them as those of the dulcimer are struck. If he did not twang them, he may have drawn the plectrum across them. Indeed, for twanging, a short plectrum would 18 have been more practical, considering that the strings are placed horizontally one above the other at regular distances. It is therefore by no means improbable that we have here a rude prototype of the violin bow.

The lyre occurs in three different forms, and is held horizontally in playing, or at least nearly so. Its front bar was generally either oblique or slightly curved. The strings were tied round the bar so as to allow of their being pushed upwards or downwards. In the former case the tension of the strings increases, and the notes become therefore higher; on the other hand, if the strings are pushed lower down the pitch of the notes must become deeper. The lyre was played with a small plectrum as well as with the fingers.

The Assyrian trumpet was very similar to the Egyptian. Furthermore, we meet with three kinds of drums, of which one is especially noteworthy on account of its odd shape, somewhat resembling a sugar loaf; with the tambourine; with two kinds of cymbals; and with bells, of which a considerable number have been found in the mound of Nimroud. These bells, which have greatly withstood the devastation of time, are but small in size, the largest of them being only 3¼ inches in height and 2½ inches in diameter. Most of them have a hole at the top, in which probably the clapper was fastened. They are made of copper mixed with 14 per cent. of tin.

Instrumental music was used by the Assyrians and Babylonians in their religious observances. This is obvious from the sculptures, and is to some extent confirmed by the mode of worship paid by command of king Nebuchadnezzar to the golden image; “Then an herald cried aloud, To you it is commanded, O people, nations, and languages, that at what time ye hear the sound of the cornet, flute, harp, sackbut, psaltery, dulcimer, and all kinds of musick, ye fall down and 19 worship the golden image that Nebuchadnezzar the king has set up.” The kings appear to have maintained at their courts musical bands, whose office it was to perform secular music at certain times of the day or on fixed occasions. Of king Darius we are told that, when he had cast Daniel into the den of lions, he “went to his palace, and passed the night fasting, neither were instruments of musick brought before him;” from which we may conclude that his band was in the habit of playing before him in the evening. A similar custom prevailed also at the court of Jerusalem, at least in the time of David and Solomon; both of whom appear to have had their royal private bands, besides a large number of singers and instrumental performers of sacred music who were engaged in the Temple.

The Hebrews.

As regards the musical instruments of the Hebrews, we are from biblical records acquainted with the names of many of them; but representations to be trusted are still wanting, and it is chiefly from an examination of the ancient Egyptian and Assyrian instruments that we can conjecture almost to a certainty their construction and capabilities. From various indications, which it would be too circumstantial here to point out, we believe the Hebrews to have possessed the following instruments:

The Harp.—There can be no doubt that the Hebrews possessed the harp, seeing that it was a common instrument among the Egyptians and Assyrians. But it is uncertain which of the Hebrew names of the stringed instruments occurring in the Bible really designates the harp.

The Dulcimer.—Some writers on Hebrew music consider the nevel to have been a kind of dulcimer; others conjecture 20 the same of the psanterin mentioned in the hook of Daniel,—a name which appears to be synonymous with the psalterion of the Greeks, and from which also the present oriental dulcimer, santir, may have been derived. Some of the instruments mentioned in the book of Daniel may have been synonymous with some which occur in other parts of the Bible under Hebrew names; the names given in Daniel being Chaldæan. The asor was a ten-stringed instrument played with a plectrum, and is supposed to have borne some resemblance to the nevel.

The Lyre.—This instrument is represented on some Hebrew coins generally ascribed to Judas Maccabæus, who lived in the second century before the Christian era. There are several of them in the British Museum; some are of silver, and the others of copper. On three of them are lyres with three strings, another has one with five, and another one with six strings. The two sides of the frame appear to have been made of the horns of animals, or they may have been of wood formed in imitation of two horns which originally were used. Lyres thus constructed are still found in Abyssinia. The Hebrew square-shaped lyre of the time of Simon Maccabæus is probably identical with the psalterion. The kinnor, the favourite instrument of king David, was most likely a lyre if not a small triangular harp. The lyre was evidently an universally known and favoured instrument among ancient eastern nations. Being more simple in construction than most other stringed instruments it undoubtedly preceded them in antiquity. The kinnor is mentioned in the Bible as the oldest stringed instrument, and as the invention of Jubal. Even if the name of one particular stringed instrument is here used for stringed instruments in general, which may possibly be the case, it is only reasonable to suppose that the oldest and most universally known 21 stringed instrument would be mentioned as a representative of the whole class rather than any other. Besides, the kinnor was a light and easily portable instrument; king David, according to the Rabbinic records, used to suspend it during the night over his pillow. All its uses mentioned in the Bible are especially applicable to the lyre. And the resemblance of the word kinnor to kithara, kissar, and similar names known to denote the lyre, also tends to confirm the supposition that it refers to this instrument. It is, however, not likely that the instruments of the Hebrews—indeed their music altogether—should have remained entirely unchanged during a period of many centuries. Some modifications were likely to occur even from accidental causes; such, for instance, as the influence of neighbouring nations when the Hebrews came into closer contact with them. Thus may be explained why the accounts of the Hebrew instruments given by Josephus, who lived in the first century of the Christian era, are not in exact accordance with those in the Bible. The lyres at the time of Simon Maccabæus may probably be different from those which were in use about a thousand years earlier, or at the time of David and Solomon, when the art of music with the Hebrews was at its zenith.

There appears to be a probability that a Hebrew lyre of the time of Joseph (about 1700 B.C.) is represented on an ancient Egyptian painting[3] discovered in a tomb at Beni Hassan—which is the name of certain grottoes on the eastern bank of the Nile. Sir Gardner Wilkinson, in his “Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians,” observes: “If, when we become better acquainted with the interpretation of hieroglyphics, the ‘strangers’ at Beni Hassan should prove to be the arrival of Jacob’s family in Egypt, we may examine 22 the Jewish lyre drawn by an Egyptian artist. That this event took place about the period when the inmate of the tomb lived is highly probable—at least, if I am correct in considering Usertsen I. to be the Pharaoh who was the patron of Joseph; and it remains for us to decide whether the disagreement in the number of persons here introduced, thirty-seven being written over them in hieroglyphics, is a sufficient objection to their identity. It will not be foreign to the present subject to introduce those figures, which are curious, if only considered as illustrative of ancient customs at that early period, and which will be looked upon with unbounded interest should they ever be found to refer to the Jews. The first figure is an Egyptian scribe, who presents an account of their arrival to a person seated, the owner of the tomb, and one of the principal officers of the reigning Pharaoh. The next, also an Egyptian, ushers them into his presence; and two advance bringing presents, the wild goat or ibex and the gazelle, the productions of their country. Four men, carrying bows and clubs, follow, leading an ass on which two children are placed in panniers, accompanied by a boy and four women; and, last of all, another ass laden, and two men—one holding a bow and club, the other a lyre, which he plays with the plectrum. All the men have beards, contrary to the custom of the Egyptians, but very general in the East at that period, and noticed as a peculiarity of foreign uncivilized nations throughout their sculptures. The men have sandals, the women a sort of boot reaching to the ankle, both which were worn by many Asiatic people. The lyre is rude, and differs in form from those generally used in Egypt.” In the engraving the lyre-player, another man, and some strange animals from this group, are represented.

The Tamboura.—Minnim, machalath, and nevel are usually supposed to be the names of instruments of the lute 23 or guitar kind. Minnim, however, appears more likely to imply stringed instruments in general than any particular instrument.

The Single Pipe.—Chalil and nekeb were the names of the Hebrew pipes or flutes.

The Double Pipe.—Probably the mishrokitha mentioned in Daniel. The mishrokitha is represented in the drawings of our histories of music as a small organ, consisting of seven pipes placed in a box with a mouthpiece for blowing. But the shape of the pipes and of the box as well as the row of keys for the fingers exhibited in the representation of the mishrokitha have too much of the European type not to suggest that they are probably a product of the imagination. Respecting the illustrations of Hebrew instruments which usually accompany historical treatises on music and commentaries on the Bible, it ought to be borne in mind that most of them are merely the offspring of conjectures founded on some obscure hints in the Bible, or vague accounts by the Rabbins.

The Syrinx or Pandean Pipe.—Probably the ugab, which in the English authorised version of the Bible is rendered “organ."

The Bagpipe.—The word sumphonia, which occurs in the book of Daniel, is, by Forkel and others, supposed to denote a bagpipe. It is remarkable that at the present day the bagpipe is called by the Italian peasantry Zampogna. Another Hebrew instrument, the magrepha, generally described as an organ, was more likely only a kind of bagpipe. The magrepha is not mentioned in the Bible but is described in the Talmud. In tract Erachin it is recorded to have been a powerful organ which stood in the temple at Jerusalem, and consisted of a case or wind-chest, with ten holes, containing ten pipes. Each pipe was capable of emitting ten 24 different sounds, by means of finger-holes or some similar contrivance: thus one hundred different sounds could be produced on this instrument. Further, the magrepha is said to have been provided with two pairs of bellows and with ten keys, by means of which it was played with the fingers. Its tone was, according to the Rabbinic accounts, so loud that it could be heard at an incredibly long distance from the temple. Authorities so widely differ that we must leave it uncertain whether the much-lauded magrepha was a bagpipe, an organ, or a kettle-drum.

The Trumpet.—Three kinds are mentioned in the Bible, viz., the keren, the shophar, and the chatzozerah. The first two were more or less curved and might properly be considered as horns. Most commentators are of opinion that the keren—made of ram’s horn—was almost identical with the shophar, the only difference being that the latter was more curved than the former. The shophar is especially remarkable as being the only Hebrew musical instrument which has been preserved to the present day in the religious services of the Jews. It is still blown in the synagogue, as in time of old, at the Jewish new-year’s festival, according to the command of Moses (Numb. xxix. 1). The chatzozerah was a straight trumpet, about two feet in length, and was sometimes made of silver. Two of these straight trumpets are shown in the famous triumphal procession after the fall of Jerusalem on the arch of Titus.

The Drum.—There can be no doubt that the Hebrews had several kinds of drums. We know, however, only of the toph, which appears to have been a tambourine or a small hand-drum like the Egyptian darabuka. In the English version of the Bible the word is rendered timbrel or tabret. This instrument was especially used in processions on occasions of rejoicing, and also frequently by females. We find 25 it in the hands of Miriam, when she was celebrating with the Israelitish women in songs of joy the destruction of Pharaoh’s host; and in the hands of Jephtha’s daughter, when she went out to welcome her father. There exists at the present day in the East a small hand-drum called doff, diff, or adufe—a name which appears to be synonymous with the Hebrew toph.

The Sistrum.—Winer, Saalschütz, and several other commentators are of opinion that the menaaneim, mentioned in 2 Sam. vi. 5, denotes the sistrum. In the English Bible the original is translated cymbals.

Cymbals.—The tzeltzelim, metzilloth, and metzilthaim, appear to have been cymbals or similar metallic instruments of percussion, differing in shape and sound.

Bells.—The little bells on the vestments of the high-priest were called phaamon. Small golden bells were attached to the lower part of the robes of the high-priest in his sacred ministrations. The Jews have, at the present day, in their synagogues small bells fastened to the rolls of the Law containing the Pentateuch: a kind of ornamentation which is supposed to have been in use from time immemorial.

Besides the names of Hebrew instruments already given there occur several others in the Old Testament, upon the real meaning of which much diversity of opinion prevails. Jobel is by some commentators classed with the trumpets, but it is by others believed to designate a loud and cheerful blast of the trumpet, used on particular occasions. If Jobel (from which jubilare is supposed to be derived) is identical with the name Jubal, the inventor of musical instruments, it would appear that the Hebrews appreciated pre-eminently the exhilarating power of music. Shalisbim is supposed to denote a triangle. Nechiloth, gittith, and machalath, which 26 occur in the headings of some psalms, are also by commentators supposed to be musical instruments. Nechiloth is said to have been a flute, and gittith and machalath to have been stringed instruments, and machol a kind of flute. Again, others maintain that the words denote peculiar modes of performance or certain favourite melodies to which the psalms were directed to be sung, or chanted. According to the records of the Rabbins, the Hebrews in the time of David and Solomon possessed thirty-six different musical instruments. In the Bible only about half that number are mentioned.

Most nations of antiquity ascribed the invention of their musical instruments to their gods, or to certain superhuman beings. The Hebrews attributed it to man; Jubal is mentioned in Genesis as “the father of all such as handle the harp and organ” (i.e., performers on stringed instruments and wind instruments). As instruments of percussion are almost invariably in use long before people are led to construct stringed and wind instruments it might perhaps be surmised that Jubal was not regarded as the inventor of all the Hebrew instruments, but rather as the first professional cultivator of instrumental music.

The Greeks.

Many musical instruments of the ancient Greeks are known to us by name; but respecting their exact construction and capabilities there still prevails almost as much diversity of opinion as is the case with those of the Hebrews.

It is generally believed that the Greeks derived their musical system from the Egyptians. Pythagoras and other philosophers are said to have studied music in Egypt. It would, however, appear that the Egyptian influence upon Greece, as far as regards this art, has been overrated. Not only have the more perfect Egyptian instruments—such as the larger harps, the tamboura—never been much in favour with the Greeks, but almost all the stringed instruments which the Greeks possessed are stated to have been originally derived from Asia. Strabo says: “Those who regard the whole of Asia, as far as India, as consecrated to Bacchus, point to that country as the origin of a great portion of the present music. One author speaks of ‘striking forcibly the Asiatic kithara,’ another calls the pipes Berecynthian and Phrygian. Some of the instruments also have foreign names, as Nablas, Sambyke, Barbitos, Magadis, and many others."

We know at present little more of these instruments than that they were in use in Greece. The Magadis is described as having twenty strings. The other three are known to have been stringed instruments. But they cannot have been anything like such universal favourites as the lyre, because this 28 instrument and perhaps the trigonon are almost the only stringed instruments represented in the Greek paintings on pottery and other monumental records. If, as might perhaps be suggested, their taste for beauty of form induced the Greeks to represent the elegant lyre in preference to other stringed instruments, we might at least expect to meet with the harp; an instrument which equals if it does not surpass the lyre in elegance of form.

The representation of a Muse with a harp, depicted on a splendid Greek vase now in the Munich Museum (Mun. Vase Cat. No. 805), may be noted as an exceptional instance. This valuable relic dates from the end of the fifth century B.C. The instrument resembles in construction as well as in shape the Assyrian harp, and has fifteen strings. The Muse is touching them with both hands, using the right hand for the treble and the left for the bass. She is seated, holding the instrument in her lap. The little tuning-pegs, which in number are not in accordance with the strings, are placed on the sound-board at the upper part of the frame, exactly as on the Assyrian harp. If we have here the Greek harp, it was more likely an importation from Asia than from Egypt. In short, as far as can be ascertained, the most complete of the Greek instruments appear to be of Asiatic origin. Especially from the nations who inhabited Asia Minor the Greeks are stated to have adopted several of the most popular. Thus we may read of the short and shrill-sounding pipes of the Carians; of the Phrygian pastoral flute; of the three-stringed kithara of the Lydians; and so on.

The Greeks had lyres of various kinds, more or less differing in construction, form, and size, and distinguished by different names; such as lyra, kithara, chelys, phorminx, etc. Lyra appears to have implied instruments of this class in general, and also the lyre with a body oval at the base and held in 29 the arms of the performer; while the kithara had a square base and was held against the side by a sash around it. The chelys was a small lyre with the body made of the shell of a tortoise, or of wood in imitation of the tortoise. The phorminx was a large lyre, and, like the kithara, was used at an early period singly, for accompanying recitations. It is recorded that the kithara was employed for solo performances as early as B.C. 700.

The design on the Greek vase at Munich (already alluded to) represents the nine Muses, of whom three are given in the engraving (Fig. 6), viz., one with the harp, and two others with lyres. Some of the lyres were provided with a bridge, while others were without it. The largest was held probably on or between the knees, or were attached to the left arm by means of a band, to enable the performer to use his hands 30 without impediment. The strings, made of catgut or sinew, were more usually twanged with a plektron than merely with the fingers. The plektron was a short stem of ivory or metal pointed at both ends.

A fragment of a Greek lyre which was found in a tomb near Athens is deposited in the British Museum. The two pieces constituting its frame are of wood. Their length is about 18 inches, and the length of the cross-bar at the top is about 9 inches. The instrument is unhappily in a condition too dilapidated and imperfect to be of any essential use to the musical inquirer.

The trigonon consisted originally of an angular frame, to which the strings were affixed. In the course of time a third bar was added to resist the tension of the strings, and its triangular frame resembled in shape the Greek delta. Subsequently it was still further improved, the upper bar of the frame being made slightly curved, whereby the instrument obtained greater strength and more elegance of form.

The magadis, also called pektis, had twenty strings which were tuned in octaves, and therefore produced only ten tones. It appears to have been some sort of dulcimer, but information respecting its construction is still wanting. There appears to have been also a kind of bagpipe in use called magadis, of which nothing certain is known. Possibly, the same name may have been applied to two different instruments.

Fig. 7.—Pair of Bronze Flutes,

with mouthpiece in the form of the bust of a Mænad holding a bunch of grapes. Greek.

British Museum.

The barbitos was likewise a stringed instrument of this kind. The sambyke is traditionally said to have been invented by Ibykos, about 560 B.C. The simikon had thirty-five strings, and derived its name from its inventor, Simos, who lived about 600 B.C. It was perhaps a kind of dulcimer. The nabla had ten, or according to Josephus, twelve strings, and probably resembled the nevel of the Hebrews, of which but little is known with certainty. The pandoura is supposed to have been a kind of lute with three strings. Several of the instruments just noticed were used in Greece, chiefly by musicians who had immigrated from Asia; they can therefore hardly be considered as national musical instruments of the Greeks. The monochord had (as its name implies) only a single string, and was used as a tuning string.

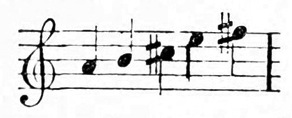

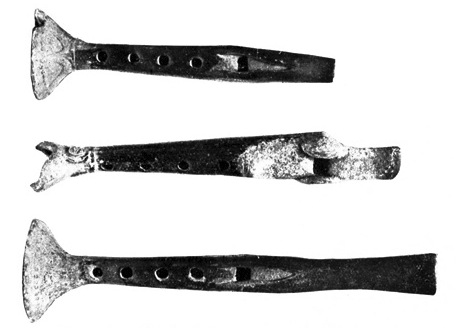

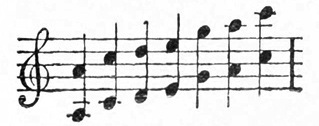

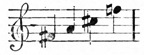

The aulos, of which there were many varieties, was a highly popular instrument, and differed in construction from the flutes and pipes of the ancient Egyptians. Instead of being blown through a hole at the side near the top it was held like a flageolet, and a vibrating reed was inserted into the mouth-piece, so that it might be more properly described as a kind of oboe or clarinet. The Greeks were accustomed to designate by the name of aulos all wind instruments of the flute and oboe kind, some of which were constructed like the flageolet or like our antiquated flûte à bec. The single flute was called monaulos (Fig. 7), and the double one diaulos (Fig. 8). A diaulos, which was found in a tomb at Athens, is in the British Museum. The wood of which it is made seems to be cedar, and the tubes are fifteen inches in length. Each tube has a separate mouth-piece and six finger-holes, five of which are at the upper side and one is underneath.

The syrinx, or Pandean pipe, had from three to nine tubes, but seven was the usual 32 number. The straight trumpet, salpinx, and the curved horn, keras, made of brass, were used exclusively in war. The small hand-drum, called tympanon, resembled in shape our tambourine, and was covered with parchment at the back as well as at the front. The kymbala were made of metal, and resembled our small cymbals. The krotala were almost identical with our castanets, and were made of wood or metal.

The Etruscans and Romans.

The Romans are recorded to have derived some of their most popular instruments originally from the Etruscans, a people which at an early period excelled all other Italian nations in the cultivation of the arts as well as in social refinement, and which possessed musical instruments similar to those of the Greeks. It must, however, be remembered that many of the vases and other specimens of art which have been found in Etruscan tombs, and on which delineations of lyres and other instruments occur, are supposed to be productions of Greek artists whose works were obtained from Greece by the Etruscans, or who were induced to settle in Etruria.

The flutes of the Etruscans were not unfrequently made of ivory; those used in religious sacrifices were of box-wood, of a species of the lotus, of ass’ bone, bronze and silver. A bronze flute, somewhat resembling our flageolet, has been found in a tomb; likewise a huge trumpet of bronze. An Etruscan cornu is deposited in the British Museum, and measures about four feet in length.

To the Etruscans is also attributed by some the invention of the hydraulic organ. The Greeks possessed a somewhat similar contrivance which they called hydraulis, i.e., water-flute and which probably was identical with the organum 33 hydraulicum of the Romans. The instrument ought more properly to be regarded as a pneumatic organ, for the sound was produced by the current of air through the pipes; the water applied serving merely to give the necessary pressure to the bellows and to regulate their action. The pipes were probably caused to sound by means of stops, perhaps resembling those on our organ, which were drawn out or pushed in. The construction was evidently but a primitive contrivance, contained in a case which could be carried by one or two persons and which was placed on a table. The highest degree of perfection which the hydraulic organ obtained with the ancients is perhaps shown in a representation on a coin of the Emperor Nero, in the British Museum. Only ten pipes are given to it, and there is no indication of any keyboard, which would probably have been shown had it existed. The man standing at the side and holding a laurel leaf in his hand is surmised to represent a victor in the exhibitions of the circus or the amphitheatre. The hydraulic organ probably was played on such occasions; and the medal containing an impression of it may have been bestowed upon the victor.

During the time of the Republic, and especially subsequently under the reign of the Emperors, the Romans adopted many new instruments from Greece, Egypt, and even from western Asia; without essentially improving any of their importations.

Their most favourite stringed instrument was the lyre, of which they had various kinds, called, according to their form and arrangement of strings, lyra, cithara, chelys, testudo, and fidis (or fides). The name cornu was given to the lyre when the sides of the frame terminated at the top in the shape of two horns. The barbitos was a kind of lyre with a large body, which gave the instrument somewhat the shape of the Welsh crwth. The psalterium was a kind of lyre of an oblong 34 square shape. Like most of the Roman lyres, it was played with a rather large plectrum. The trigonum was the same as the Greek trigonon. It is recorded that a certain musician of the name of Alexander Alexandrinus was so admirable a performer upon it that when exhibiting his skill in Rome he created the greatest furore. Less common, and derived from Asia, were the sambuca and nablia, the exact construction of which is unknown.

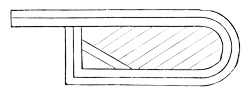

The flute, tibia, was originally made of the shin bone, and had a mouth-hole and four finger-holes. Its shape was retained even when, at a later period, it was constructed of other substances than bone. The tibia gingrina consisted of a long and thin tube of reed with a mouth-hole at the side of one end. The tibia obliqua and tibia vasca were provided with mouth-pieces affixed at a right angle to the tube; a contrivance somewhat similar to that on our bassoon. The tibia longa was especially used in religious worship. The tibia curva was curved at its broadest end. The tibia ligula appears to have resembled our flageolet. The calamus was nothing more than a simple pipe cut off the kind of reed which the ancients used as a pen for writing.

The Romans had double flutes as well as single flutes. The double flute consisted of two tubes united, either so as to have a mouth-piece in common or to have each a separate mouth-piece. If the tubes were exactly alike the double flute was called tibiæ pares; if they were different from each other, tibiæ impares. Little plugs, or stoppers, were inserted into the finger-holes to regulate the order of intervals. The tibia was made in various shapes. The tibia dextra was usually constructed of the upper and thinner part of a reed; and the tibia sinistra, of the lower and broader part. The performers used also the capistrum,—a bandage round the cheeks identical with the phorbeia of the Greeks.

Fig. 9.—Wall Painting of a youth wearing a myrtle wreath and playing on the Double Pipes.

Restored in places. Said to have been found in a columbarium in the Vigna Ammendola

on the Appian Way near Rome, about 1823.

British Museum.

The British Museum contains a wall painting (Fig. 9) representing a Roman youth playing the double pipes, which is stated to have been disinterred in the year 1823 on the Via Appia. Here the holmos or mouth-piece, somewhat resembling the reed of our oboe, is distinctly shown. The finger-holes, probably four, are not indicated, although they undoubtedly existed on the instrument.

Furthermore, the Romans had two kinds of Pandean pipes viz., the syrinx and the fistula. The bagpipe, tibia utricularis, is said to have been a favourite instrument of the Emperor Nero.

The cornu was a large horn of bronze, curved. The performer held it under his arm with the broad end upwards over his shoulder. It is represented in the engraving (Fig. 10), with the tuba and the lituus.

The tuba was a straight trumpet. Both the cornu and the tuba were employed in war to convey signals. The same was the case with the buccina,—originally perhaps a conch shell, and afterwards a simple horn of an animal,—and the lituus, which was bent at the broad end but otherwise straight. The tympanum resembled the tambourine, and was beaten like the latter with the hands. Among the Roman instruments of percussion the scabellum, which consisted of two plates combined 36 by means of a sort of hinge, deserves to be noticed; it was fastened under the foot and trodden in time, to produce certain rhythmical effects in musical performances. The cymbalum consisted of two metal plates similar to our cymbals. The crotala and the crusmata were kinds of castanets, the former being oblong and of a larger size than the latter. The Romans had also a triangulum, which resembled the triangle occasionally used in our orchestra. The sistrum they derived from Egypt with the introduction of the worship of Isis. Metal bells, arranged according to a regular order of intervals and placed in a frame, were called tintinnabula. The crepitaculum appears to have been a somewhat similar contrivance on a hoop with a handle.

Through the Greeks and Romans we have the first well-authenticated proof of musical instruments having been introduced into Europe from Asia. The Romans in their conquests undoubtedly made their musical instruments known, to some extent, also in western Europe. But the Greeks and Romans are not the only nations which introduced Eastern instruments into Europe. The Phœnicians at an early period colonized Sardinia, and traces of them are still to be found on that island. Among these is a peculiarly constructed double-pipe, called lionedda or launedda. Again, at a much later period the Arabs introduced several of their instruments into Spain, from which country they became known in France, Germany, and England. Also the crusaders, during the eleventh and twelfth centuries, may have helped to familiarize the western European nations with instruments of the East.

The Chinese.

Allowing for any exaggeration as to chronology, natural to the lively imagination of Asiatics, there is no reason to doubt that the Chinese possessed long before our Christian era musical instruments to which they attribute a fabulously high antiquity. There is an ancient tradition, according to which they obtained their musical scale from a miraculous bird, called fêng-huang, which appears to have been a sort of phœnix. When Confucius, who lived about B.C. 551-479, happened to hear on a certain occasion some Chinese music, he is said to have become so greatly enraptured that he could not take any food for three months afterwards. The sounds which produced this effect were those of K’uei, the Orpheus of the Chinese, whose performance on the ch’ing—a kind of harmonicon constructed of slabs of sonorous stone—would draw wild animals around him and make them subservient to his will. As regards the invention of musical instruments the Chinese have other traditions. In one of these we are told that the origin of some of their most popular instruments dates from the period when China was under the dominion of heavenly spirits, called Ch’i. Another assigns the invention of several stringed instruments to the great Fu-hsi who was the founder of the empire and who lived about B.C. 3000, which was long after the dominion of the Ch’i, or spirits. Again, another tradition holds that the most important instruments and systematic arrangements of sounds are an invention of Nü-wa, sister and successor of Fu-hsi.

38 According to their records, the Chinese possessed their much-esteemed ch’ing 2200 years before our Christian era, and employed it for accompanying songs of praise. It was regarded as a sacred instrument. During religious observances at the solemn moment when the ch’ing was sounded sticks of incense were burnt. It was likewise played before the emperor early in the morning when he awoke. The Chinese have long since constructed various kinds of the ch’ing, by using different species of stones. Their most famous stone selected for this purpose is called yü. Yü includes the two varieties of jade, nephrite and jadeite. It is not only very sonorous but also beautiful in appearance. It is found in mountain streams and crevices of rocks. The largest known specimens measure from two to three feet in diameter, but examples of this size rarely occur. The yü is very hard and heavy. Some European mineralogists, to whom the missionaries transmitted specimens for examination, pronounce it to be a species of agate (ma-nao). It is found of different colours, and the Chinese appear to have preferred in different centuries particular colours for the ch’ing.

The Chinese consider the yü especially valuable for musical purposes, because it always retains exactly the same pitch. All other musical instruments, they say, are in this respect doubtful; but the tone of the yü is influenced neither by cold nor heat, nor by humidity, nor dryness.

The stones used for the ch’ing have been cut from time to time in various grotesque shapes. Some represent animals: as, for instance, a bat with outstretched wings; or two fishes placed side by side: others are in the shape of an ancient Chinese bell. The angular shape appears to be the oldest form and is still retained in the ornamental stones of the pien-ch’ing, which is a more modern instrument than the 39 ch’ing. The tones of the pien-ch’ing are attuned according to the Chinese intervals called lü, of which there are twelve in the compass of an octave. The same is the case with the other Chinese instruments of this class. They vary, however, in pitch. The pitch of the sung-ch’ing, for instance, is four intervals lower than that of the pien-ch’ing.

Sonorous stones have always been used by the Chinese also singly, as rhythmical instruments. Such a single stone is called t’ê-ch’ing.

The ancient Chinese had several kinds of bells, frequently arranged in sets so as to constitute a musical scale. The Chinese name for the bell is chung. At an early period they had a somewhat square-shaped bell called t’ê-chung. Like other ancient Chinese bells it was made of copper alloyed with tin, the proportion being one part of tin to six of copper. The t’ê-chung, which is also known by the name of piao, was principally used to indicate the time and divisions in musical performances. It had a fixed pitch of sound, and several of these bells attuned to a certain order of intervals were not unfrequently ranged in a regular succession, thus forming a musical instrument which was called pien-chung. The musical scale of the sixteen bells which the pien-chung contained was the same as that of the ch’ing before mentioned.

The hsüan-chung was, according to popular tradition, included with the antique instruments at the time of Confucius, and came into popular use during the Han dynasty (from B.C. 200 until A.D. 200). It was of a peculiar oval shape and had nearly the same quaint ornamentation as the t’ê-chung; this consisted of symbolical figures, in four divisions, each containing nine mammals. The mouth was crescent-shaped. Every figure had a deep meaning referring to the seasons and to the mysteries of the Buddhist religion. The largest hsüan-chung was about twenty inches in length; 40 and, like the t’ê-chung, was sounded by means of a small wooden mallet with an oval knob. None of the bells of this description had a clapper. It would, however, appear that the Chinese had at an early period some kind of bell provided with a wooden tongue: this was used for military purposes as well as for calling the people together when an imperial messenger promulgated his sovereign’s commands. An expression of Confucius is recorded to the effect that he wished to be “A wooden-tongued bell of Heaven,” i.e., a herald of heaven to proclaim the divine purposes to the multitude.

The fang-hsiang was a kind of wood-harmonicon. It contained sixteen wooden slabs of an oblong square shape, suspended in a wooden frame elegantly decorated. The slabs were arranged in two tiers, one above the other, and were all of equal length and breadth but differed in thickness. The ch’un-tu consisted of twelve slips of bamboo, and was used for beating time and for rhythmical purposes. The slips being banded together at one end could be expanded somewhat like a fan. The Chinese state that they used the ch’un-tu for writing upon before they invented paper.

The yü, likewise an ancient Chinese instrument of percussion and still in use, is made of wood in the shape of a crouching tiger. It is hollow, and along its back are about twenty small pieces of metal, pointed, and in appearance not unlike the teeth of a saw. The performer strikes them with a sort of plectrum resembling a brush, or with a small stick called chên. Occasionally the yü is made with pieces of metal shaped like reeds.

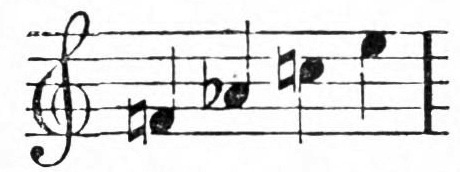

The ancient yü was constructed with only six tones which were attuned thus—f, g, a, c, d, f. The instrument appears to have deteriorated in the course of time; for, although it has gradually acquired as many as twenty-seven pieces 41 of metal, it evidently serves at the present day more for the production of rhythmical noise than for the execution of any melody. The modern yü is made of a species of wood called k’iu or ch’iu; and the tiger rests generally on a hollow wooden pedestal about three feet six inches long, which serves as a sound-board.