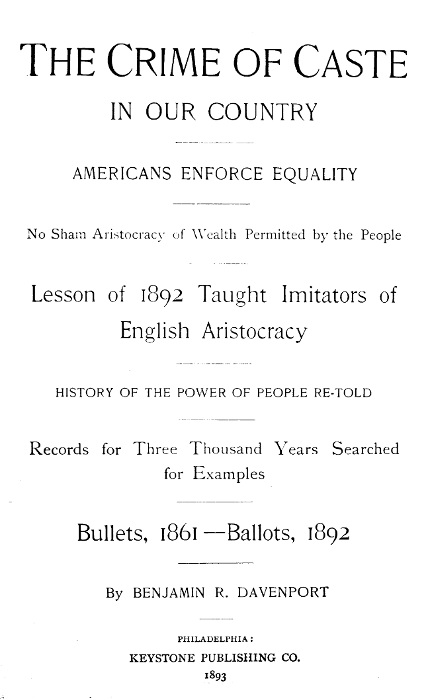

Title: The Crime of Caste in Our Country

Author: Benjamin Rush Davenport

Release date: June 26, 2021 [eBook #65707]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Tim Lindell, Martin Pettit, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (https://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Crime of Caste in Our Country, by Benjamin Rush Davenport

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/crimeofcasteinou00dave |

ABRAHAM LINCOLN

A Man of the People, who Loved and Served the People.

IN OUR COUNTRY

AMERICANS ENFORCE EQUALITY

No Sham Aristocracy of Wealth Permitted by the People

Lesson of 1892 Taught Imitators of

English Aristocracy

HISTORY OF THE POWER OF PEOPLE RE-TOLD

Records for Three Thousand Years Searched

for Examples

Bullets, 1861—Ballots, 1892

By BENJAMIN R. DAVENPORT

PHILADELPHIA:

KEYSTONE PUBLISHING CO.

1893

Copyright by

JOSEPH W. MORTON, Jr.

1892

This Book is Dedicated to All American Citizens,

who believe

That Patriotism, Honesty, Virtue, and Merit

ALONE CONSTITUTE INEQUALITY IN MANKIND;

WHO OBJECT TO AND RESENT ARROGANCE AND PRESUMPTION

UPON THE PART OF

THE POSSESSORS OF WEALTH

AND TO THOSE TO WHOM

“Caste” and Foreign Mannerisms are Obnoxious.

The Author.

The word “Caste,” we derive from a Portuguese word, which means “a race;” the Portuguese being the early voyagers to the East Indies, where they found the distinction of classes of society established under the Brahminical regime of India. Thence it came to be applied as a term of distinction of society in other countries. There were four castes in India: 1, the Priests; 2, military; 3, merchants; 4, the servile classes.

Members of the lowest caste were forbidden to marry those of the upper. Children of such unions were outcasts and irredeemably base; they could not accumulate property, nor change or improve their conditions. Along with many other senseless and inconvenient rules for the conduct of the different castes, were such as those forbidding members of different castes from using the same springs or running streams, sitting at the same table, eating with the same utensils, or preparing food in the same vessels. It was contamination for those of the first class to even mingle in the public highway with those who were of the lower castes. For convenience, and in the interest of the commercial prosperity of India, the British, after much exertion, have been able to eradicate many of these absurd distinctions, and the habits that resulted therefrom.

The attempt to create class distinctions in Free America, upon the basis of wealth or assumed social superiority, is a crime, and as such will be punished by the Common People.

| PAGE. | |

| Introduction | 11 |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Vox Populi, Vox Dei | 33 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| The Alleged General Discontent | 65 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| November 8, 1892 | 79 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Society as the People Found It November 8, 1892 | 91 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Some Reasons for Wrath | 111 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| The Aristocratic “Chappie” vs. Abraham Lincoln | 145 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Hon. John Brisben Walker, on Homestead | 161 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Surrender at Homestead.—Organized Labor Defeated | 183 |

| [Pg viii]CHAPTER IX. | |

| Possible Fruits of Victory | 204 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| The Cause of Bullets, ’61; Ballots, ’92.—Abraham Lincoln, the People’s Choice in ’60 |

225 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Andrew Jackson, 1828 | 241 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Thomas Jefferson, 1800 | 249 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| The Revolution in 1776 | 257 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| The French Revolution | 278 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| England, 1645 | 295 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| The German Empire, 1520-1525 | 307 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Switzerland, 1424 | 312 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Russia | 315 |

| [Pg ix]CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Patricians and Plebeians in Rome | 320 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| Greece.—Venice.—The Rule of “Caste” | 324 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Egypt, 4235 B. C. | 330 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Christianity | 333 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| Not a Democratic Party Victory.—Democracy is Not the Name of a Party, but of a Principle |

346 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| Not a Defeat of Abraham Lincoln’s Republican Party | 390 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| The Populist: the “Allies.”—Elected by the People; therefore, with the “Common People” |

409 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| “Flabbyism” and the Income Tax | 417 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| Conclusion | 428 |

| PAGE. | |

| Abraham Lincoln | Frontispiece. |

| Grover Cleveland | 32 |

| James B. Weaver | 64 |

| John D. Rockefeller | 105 |

| Ward MacAllister | 110 |

| “The Public be D—d” | 115 |

| Mrs. Benjamin Harrison | 127 |

| Benjamin Harrison | 131 |

| American Queen | 136 |

| American Duchess | 137 |

| Jay Gould | 143 |

| Abe, “The Rail-Splitter” | 154 |

| “Chappie” on Fifth Avenue | 155 |

| Andrew Carnegie | 160 |

| Henry C. Frick | 162 |

| The Mistake at Homestead | 182 |

| William H. Vanderbilt | 219 |

| W. Seward Webb | 223 |

| Andrew Jackson | 240 |

| Thomas Jefferson | 248 |

Had a Johnstown flood, a Charleston earthquake, a war with Chili, or a Homestead strike occurred on November 8, 1892, instead of an election, those Napoleons of journalism, James Gordon Bennett, of the New York Herald, Joseph Pulitzer, of the New York World, and Whitelaw Reid, of the Tribune, would have had a score of representatives on the scene at once, without thought of expense; would have had every detail in its most minute particular investigated, and reproduced every statement, embellished by the pencils of a host of artists, utterly regardless of expense, keeping, as these magnificent journals ever have, good faith with the public and their readers, making lasting monuments of their wonderful papers for coming generations of journalists to gaze upon.

But a revolution occurred on November 8, 1892, a revolution of the American people, so overwhelming, so decisive, and so pronounced as to absolutely stupefy even the genius of the press. Instead of corps of reporters, artists, special correspondents, speeding over the land to ascertain the cause—not the result; the cause, the origin,—of this stupendous surprise, all the great[Pg 12] journals of the country, having each nailed to its flag-staff some theory or text utterly inconsistent with the result, utterly disproportioned to the overwhelming revolution, that they have sought by vain endeavor to make an overwhelming result compatible with and agreeable to some one part or portion of the cause thereof.

To loudly proclaim, as did the New York Sun, that an exhibition of the will of the people, so pronounced as that of November the 8th, was occasioned by the Force Bill, is as utterly unreasonable as to ascribe the magnificent volume within the banks of the Mississippi to some little trickling rivulet flowing from the plains of Nebraska. To say, with the Tribune, that the grand result pronounced in the mighty voice of the people was produced by the misunderstanding of the McKinley Bill, is as groundless as to ascribe the echoing thunder tones of heaven to the swelling throat of a canary bird. To herald over the land, “Pauper emigration did it,” with the New York Herald, is about as pregnant with truth as would be the assumption that the foundation and everlasting strength of Christianity has for its basis the misguided vaporings of a negro preacher in Richmond, who proclaims, “The sun do move.” To announce, as did the World, that “Tariff reform and WE, the Democrats, achieved this victory,” is entitled to as much respect as would be given[Pg 13] the utterances of a drummer boy of the Federal Army at Gettysburg.

It was not any one nor all of these causes that moved the people. Each newspaper, Democratic or Republican, has selected some nail upon which it hangs the laurel wreath of victory, inscribed with its own puny text for which it has fought its little battle, and each newspaper of the Republican press has covered, with the tattered garments of defeat, its little text wherein it had proclaimed that the Republican party would be victorious, and labeled its tattered garment of lack of judgment with some phrase like, “Disloyalty of Platt,” “Incapacity of Carter,” “Want of Organization,” “Lack of Popularity and Magnetism of our Candidate,” “The Voters didn’t come out.” Had the press no part of its own reputation at stake, they would have searched and delved into the bosoms of men; yes, neither space nor distance, time nor expense, would have been spared by the magnates of the newspaper world to ascertain the true cause. But in ascertaining that true cause, it would have been necessary, in announcing the same, to stultify themselves in what they had been predicting, proclaiming, foretelling, and advising, for months and years.

The truth is in the air; was in the air before the election. ’Twas breathed; it was thought; yea, better, it was felt, by the great throbbing,[Pg 14] aching heart of the men and women of the Union. From the hovel to the palace, the insidious, poisonous vapor of a supposed affected, sham aristocracy, with the noxious slime of a half-proclaimed doctrine of the inequality of man and woman, by reason of non-possession of wealth, had crept. The air of freedom was polluted by the emanations arising from the imported English decaying corpse of aristocracy. It was everywhere. In blindness and self-delusion, the press made its battle; in the very air of it, howling against Protection and for Protection, against Force Bill and for Force Bill, while the wretched, cankerous ulcer was eating into the pride of every free-born man and woman in the land. The very silence of the people, the general apathy, was evidence of but one of the symptoms of the insidious disease with which the body politic was being consumed.

A scene that has been described in Washington just prior to the late Civil War best illustrates the condition of the people. The city of Washington was filled with silent, sullen, suspicious men. A sombre air pervaded the Capital. South Carolina had seceded; the Union was disintegrating. All that had been, was being forgotten. Old ties were breaking; old friendships becoming strange. Each man viewed his neighbor and his friend of yesterday, with a doubt in his mind as to whether they would fight side by side, or beat each other’s[Pg 15] throats to-morrow. Men paced their rooms in the various hotels, anxious and careworn, sleepless and fearful. Yet, the surface was still, a dangerous state of general apathy obtained, if silence and murmuring, without action, can be called apathy.

It was night, yet the streets were not deserted. Suddenly a window of the Ebbitt House was raised, a man stepped on to the balcony out of the window, and in clear, vigorous, and manly tones began to sing “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Windows were raised; the crowd collected around the Ebbitt House. It was the signal for the breaking of a dam. A flood of patriotism burst from the hearts of the hearers; it was the bugle note, calling upon Americans to save their country. Where there had been silence, were now outspoken vows of fidelity and loyalty to the Union. The battle was won that night; not at Gettysburg and Vicksburg[1].

Just so with the people of America in 1892; for years they have endured in silence, murmuring and thinking, heart to heart speaking by responsive heart throbs; not by word. The rich, who had accumulated their wealth by reason of monopolies which were the necessary consequence of the Civil War, men who had laid the foundation[Pg 16] of their fortunes by speculating upon the necessities of the government while contending for the very existence of the Union, had, year by year, by a stealthy, yet ever-increasing presumption, begun to assume the possibility of a class distinction, presuming that the possession of wealth entitled them to privileges, and arrogating to themselves mannerisms of the titled classes of Europe, adopting crests, coats of arms, claiming descent from titled foreigners, an exclusiveness in their social relations, disregarding the laws of morality. The women of this would-be aristocratic class, flaunting their jewels and laces in the faces of their poorer sisters, with elevated noses, and garments drawn aside, feared to touch or gaze at the poor but honest mothers and wives of America.

It was not much: it was rank presumption; it was nonsense, absurd. “There’s no such thing possible in America as class distinction; in fact, it does not exist, cannot exist; the ‘Four Hundred’ of New York is a joke, a by-word, a stupendous folly.”

But, good people of the said “Four Hundred,” remember that while the American is neither a Socialist nor an Anarchist, when you presume to make a distinction, socially, between the poor man, his wife, children, and mother, you touch him in the most sensitive part of his being. You may[Pg 17] have your villas at Newport, you may ape the English fashionable season in London by a similar one in New York; you may have your steam yachts; you may ride to hounds; your women may marry divorced dukes and puppified sons of lords; but, mark you, claim no privilege, attempt no distinction between yourselves and the poorest honest man and woman in the land. Equality is the jewel that every true American holds most dear. No free son of our Republic will sell this treasure for gold, whether it be offered directly as a bribe or shrewdly tendered under the guise of “protected” wages.

It did not do for the Republican press of the country to demonstrate that Protection brought higher wages to the workingman. They might have proved that by voting the Republican ticket the workingman’s pay would have been a hundred dollars a day; they might have shown him that in point of pocket he would be eternally blest by supporting the party which he deemed identified with those who attempted to force “caste” upon our country. It is not a question of money; the equality of man is the American’s birthright. For it, our fathers sought these shores, contending with privation, enduring untold labor, dangers, and death. For it, our forefathers fought the most powerful nation on earth, when they were but a scattered handful of colonists, scattered from[Pg 18] Massachusetts to Georgia. When the attempt was made—that it was attempted, there can be no doubt—to buy the American’s birthright by preaching to him “increased wages,” it failed.

Take every speech of every Republican orator, every bit of Republican literature, every editorial in the Republican papers, all speak from but one text, viz.: “Workmen, farmers, in fact, all ye good people of America, you can make more money under Protection;” which plainly means, “Let Protection and the Republican party (which you designate in your hearts as The Rich Man’s party) continue in power, accumulating wealth, creating class distinctions, and you can have better wages.”

In other words, “Sell us the right to create a Republic like that of Venice, wherein the rich became the privileged class, and we will give you better pay.”

The Democratic press, orators, and literary bureau were no better. They no more understood the feeling of the people, for their continual cry was, “Free Trade, and you will be better off in pocket.” They excoriated trusts, monopolies; they talked of corruption and what would be done to benefit, IN POCKET, the poor man, if the Democratic party came in power; just as blind as their brothers of the Republican party, they appealed to the American pocketbook.

While every Democratic orator knew that he felt the sting of the venomous and growing reptile, “caste,” in no place in the literature of the Democratic party, in no paper, can be found one single reference to the pride of the American in his citizenship, in his equality. It seemed as if each man thought that he alone endured a pang upon the subject of “caste” and social distinction; for, bear in mind, the man with one million will feel the slight and attempted distinction between his family and the family with ten millions, just as keenly as the cashier of a bank will feel the distinction that the president attempts to make between their social positions; the farmer with ten acres feels towards the farmer with a hundred acres, exactly the same as the farmer with a hundred does towards the farmer possessed of a thousand acres.

This disease was not confined to the horny-handed sons of toil; the heart in the hovel was not the only one that ached. It was not confined to the follower of the plow; but its pestilential breath pervaded every home in the land, leaving everyone below the multi-millionaire unhappy. The clerk of the dry-goods store was hurt because the floor walker assumed a superiority; the floor walker, because the proprietor assumed it; the proprietor, because the importer from whom he purchased goods assumed a distinction; and so it[Pg 20] continued, from the longshoreman up, until it reached our millionaire would-be princes, who ape and mimic English life and manners, leaving, as it arose, a sting of increasing bitterness; but each man felt too proud to give utterance to what he thought it shamed him even to recognize as a sensation.

Hence the apathy on the surface, the sentiment confessed only to themselves and in the closet of the voting booth. Because the people had identified the Republican party with the class of men who were striving to create this class distinction, and because of the very charm of the word Democracy to their aching hearts, they voted the Democratic ticket—not Democrats alone in a political sense, but men who believe in democracy in the broad sense that St. Paul preached on Mars Hill at Athens, in the broad sense that Christ’s life demonstrated.

It was useless, against this first overmastering, powerful emotion in the American breast, to call upon the old veterans of the Civil War, to whom the Republican party had given increased pensions. It was useless to cry even to the negro, to whom the Republican party had given freedom. He, too, had become imbued with the spirit of equality. The wealthy could not purchase the birthright of the veteran by appealing to his pocketbook, any more than they could that of the[Pg 21] laborer. He had shed his blood in the cause of equality, resisting then the assumed superiority of blood and birth so often flaunted in his face by gentlemen from the South.

In 1861, the “mudsills” of the North and West, the tillers of the soil, had shouldered their muskets at the call of that great man of the people, Abraham Lincoln, leaving home and loved ones to face unknown dangers and diseases in the cause of EQUALITY. Down in their hearts then was a sentiment which is revived in 1892. That thing which had been the hardest to bear, for the laboring settler of the West and the workman of the North, was the existence of “caste” in the South, and the supposed superiority of the Southerners in the halls of Congress. Love of the Union was the outspoken, pronounced cause of their coming at Lincoln’s call; but there was something behind and beneath all of that, that had been growing for years; it was resentment, because of the South’s assumption of “caste” in our country.

The question was settled, by these very veterans, from 1861 to ’65 with bullets, and it was utterly unavailing to call upon them for ballots in 1892 against the cause for which they fought in 1861.

The very negro said to himself: “You gave us freedom, the Republican party, but the[Pg 22] Republican party of Abraham Lincoln was purely a Democratic party, in a broader sense.” To the negro’s mind, no three Presidents of the past will more thoroughly represent a picture pleasing to the eye of the enslaved or the lower classes, than Jefferson, Jackson, and Lincoln. All were Democrats—men who believed in the people and labored for the people, leading lives of pure simplicity, affecting no superiority of rank or position. It was useless to attempt to hold the negro vote.

The very name of the “People’s Party,” so strongly did it indicate and describe this sentiment of the people; enabled that party, with all its incongruous doctrines, to carry the electoral votes of some States of the Union.

How frivolous seemed the claim of the Democratic papers and politicians, that the popularity of Grover Cleveland, and the confidence that people had in his rectitude and honesty, caused this revolution. How it appears to be trifling with truth to ascribe the victory of the people, the true Democracy, to the “masterly manner in which Mr. Harrity managed the campaign.” Mr. Whitney’s diplomacy, Mr. Dickinson’s energy and ability, Mr. Sheehan’s shrewdness, sink into utter insignificance, and become as a grain of sand upon the seashore, where they have happened to be tossed by the mighty wave of the ocean of feeling, full of resentment, that filled the hearts of the[Pg 23] people. Their little all was but the piping of a penny whistle in a gale of wind. W. H. Vanderbilt’s four words, “The public be damned,” uttered from the pedestal of $150,000,000, made a greater impression, and became more indelibly impressed upon the minds of the whole people, ranging in wealth from $10,000,000 to less than a cent, than all the management of Harrity, the diplomacy of Whitney, the skill of Sheehan, or the energy of Dickinson. The reported expression of Mr. Russell Harrison, when asked, while in London, what his position was in America, as son of the President,—“Oh, about what the Prince of Wales is here,”—was thought of and resented to greater purpose than was produced by all the speeches of the eloquent Cockran.

The women of the land made more speeches, and effective speeches, to the voters of the land when they thought of the much-advertised American Duchess. They had felt most keenly—for woman’s life is social much more than man’s—the attempted social distinction; and, strange as it may appear to some of the skillful politicians that they had never recognized it, the women of America had become largely Democratic, and in them the Democratic party had its most powerful orators; for even the most brutal, neglectful, and unloving husband resents in a vigorous manner the least slight or insult offered to his wife. Upon every[Pg 24] occasion, gathering, entertainment, charitable undertaking, some wife had been slighted. Because of the attempted creation of “caste,” she became a powerful factor, at once, in the campaign of the people. It mattered not whether her husband was a millionaire or not, no matter in what portion of society,—the clerk in a dry-goods store, the farmer, the banker, the millionaire,—the same result would follow. Some would attempt to arrogate to themselves a better position, and claim certain superiority over her. The banker’s wife feels as keenly the slight of the wife of a railroad president, as the wife of a longshoreman does any assumed difference in social position on the part of the wife of the retail grocer.

This all-prevailing crime of “caste” does not, like most crimes are supposed to do, originate in the gutter, but it permeates the mass of the population, like the source of a great river, starting at the very top of the mountain, and dripping constantly downward.

The example of the rich in imitating the immoralities of the privileged classes of Europe, presents a spectacle of presumed immunity from the consequences of their crimes which would be as detrimental to the continuation of the purity of American homes, as the increase of the feeling of “caste” would be to the happiness of the people. A most beautiful illustration of corruption in high[Pg 25] places was presented in the disgusting and nauseating Drayton-Borrowe affair, wherein the daughter of an Astor, a multi-millionaire, one of the members of the supposed upper “caste,” is paraded before the public as imitating the vices and immoralities of the Court of Charles II. Yet these same Astors would claim, by reason of their assumed position, some exemption from the result of the crime, which would not be accorded to the wife of a farmer, clerk, or a bank cashier, to say nothing of the fact that, had this beautiful sample of America’s sham aristocracy been a laborer’s wife, she would, by the peculiar ethics adopted by the corrupt English aristocracy, have been a fit subject for the police court.

Another of the disgusting apings of foreign vices, along with the foolish claim of “caste,” is exhibited in the delightful Deacon assassination in France. Another representative of American aristocracy, so-called, would play the part of a French Countess. Fortunately for the world, the man Deacon had left remaining a few drops of American blood in his veins, and rid the world of a brute, as any honest American laboring man would have done. The class which the shameless imitators pretend to represent in America assumed the privilege abroad (in Europe) to indulge in drunkenness, debauchery, gambling, and general immorality; leaving the[Pg 26] virtues, sobriety, honesty, and purity to the lower classes. In America, there being but one class, those who assume to imitate the manners of the immoral, to carouse and debauch, render themselves obnoxious to the mass of the people, and that political party which becomes identified in the minds of the people with any set, or “caste,” possessing such distorted principles, becomes correspondingly objectionable. There can be but one law of morals in America. Debauchery, drunkenness, and dishonesty, though sheltered by a palace, are as odoriferous to the senses of the people as the polluted air from a sewer.

There are many able and learned men of America who think seriously and have thought intently for years upon this subject, but hesitated to utter sentiments that falsely and absurdly are called socialistic and anarchical. There is no desire upon the part of Americans to deprive any citizen of his property and his freedom to enjoy the same as he will, so long as he has due appreciation of and respect for the rights of others. No man in the Republic can possess any right, by reason of his wealth, greater than the poorest in the land. Each citizen of a republic, in consideration of the liberty that he enjoys, surrenders all claim to be anything except one of the people, and any assumed immunity from the consequences of his acts is objectionable, and will[Pg 27] be visited upon his head. The roistering sons of millionaires, though clad in evening dress and drunk with champagne, are no less disgusting rowdies than the sons of the laborer, hilarious as the result of gin drunk in a groggery. Unfortunately for the Republican party, in looking over the row of America’s money princes (?), we find “Republican” written behind almost every name. The villa at Newport, the castle in Scotland, the Tally Ho coach, is generally owned by a Republican. In fact, our would-be aristocrats began to assume that it was almost a disgrace to be anything else than a Republican; one would lose “caste” thereby.

The Republican party, of course, is not responsible for this. The Republican candidate, Benjamin Harrison, than whom there is no better example of a patriotic, earnest, honest American, Christian, father, husband, son, gentleman, and soldier, is worthy to be an example to the young men of our country. He was not responsible for the impression made by this excrescence that has grown like some hideous and poisonous fungus upon the stalwart oak planted by Abraham Lincoln. The decay has arisen from this polluting attachment. The McKinley Bill and Protection, while possessing many points of excellence it behooves the country to examine with care before erasing from the statute-books, are not responsible[Pg 28] for the natural animosity of the people toward this child, deformed, misshapen, Sham Aristocracy, clinging to the skirts of the Republican party. The attack was upon this hideous tumor, and, by its amputation by the people, the life-blood of the Republican party has become exhausted; for the operation necessarily was made painful, deep-felt, and severe. The Democratic party derived all the benefit from the defeat of the Republican party, at the hands of the people, without having contributed thereto to any amazing extent.

The result of the election of 1892 should be as the warning written on the wall was to Belshazzar. The rich must understand, and learn now in time, that they hold their lives, their liberty, and their property in this Republic only by the will of the people; that the people, Democratic always in the broad sense of democracy, are long-suffering; but retribution, as surely as night doth follow day, may come, if this warning be not heeded, in some more terrible shape than an overwhelming defeat, at the polls, of that party to which the rich attach themselves. It is not well to flaunt riches or claim privileges or “caste” before the face of a free people.

It would be well for the rich to learn this lesson. It was taught by the people under the name of the Republican party when they elected Lincoln; under the name of the Democratic party[Pg 29] when they elected Andrew Jackson; under the name of the Democratic party when they elected Thomas Jefferson. It was taught to rich and powerful England when she lost a continent in 1776; it was taught to Anglo-Saxon England when Charles I. lost his head; it was taught to France when the long-suffering peasantry and poor broke down the barriers of “caste,” and flooded her fair fields with the tide of blood.

It has been taught in every nation—Rome, Greece, Egypt. The people will suffer long and much, but the resentment occasioned by “caste” and social distinction far outweighs any advantages that money can buy them.

November 8, 1892, showed that the workmen couldn’t be bought, the farmer couldn’t be bought, the veteran couldn’t be bought, the negro couldn’t be bought, by all the fair promises held out by the party of Protection, because this cup of nectar was poisoned by the deadly essence of “caste,” which means extinction of all that the people hold dear. Should the Democratic party create, cause, or have arise under its administration, and become attached to that party, any set, or “caste,” claiming any superiority over their fellow-citizens, the Democratic party would be killed, though the eternal sun might never shine again upon America should that party be defeated.

The purpose and object for which this book is written is not for the instruction of the people as to how they are to do, but it is, if possible, to put notes to the music that has been singing in the hearts of the Common People,—for we are all Common People. That song which echoes our own sentiments, even though we cannot sing the song, is always the sweetest. The man who tells the story we have thought and felt, is the greatest writer to us. Dickens is dear to the hearts of us all because he echoes and puts in words the sentiments of our own souls. If this book tell, in words, that which has been throbbing in the breasts of the people, it but articulates that which they have spoken silently for themselves. The author is one of the people, but he has felt what he believes others have felt. The book is not intended to aid or to harm either the Democratic or the Republican party. The writer is a supporter of ANY party, call it what you will, that represents the BEST INTERESTS, THE HONOR, DIGNITY, VIRTUE, of Americans and American homes.

[1] This story has frequently been related, verbally, but the Author has never seen it in print. Its authenticity, however, is fully established.

GROVER CLEVELAND.

Selected by the “Common People,” November 8, 1892,

to Represent the

Interests of the Masses

against the Classes.

The voice of the people, is indeed, the voice of God, and in grand and tremendous tones has that voice resounded through the land. The 8th of November, 1892, will long be remembered in the history of our country as one which stands in the annals of time as a monument to the might of the people, upon which might be carved in letters of everlasting durability, “Do not tread on me.” The tidal wave, so often referred to by the newspapers, has come with unexpected momentum, washing aside the puny politicians as thistledown on the mighty stream of the Mississippi.

That mirror of public opinion, so generally correct, so apt to be accurate, is absolutely stupefied by the tremendous character of the uprising of the people. Even those who fondly hoped for victory, among the Democratic journalists, stand in reverential awe before the stupendous results so noiselessly and irresistibly effected by the masses. They vainly seek, like one bereft of sight, for the delusive cause of this great outpouring of Democratic sentiment.

That most preëminent and respectable organ of mugwump principles, the New York Times, of November 9, 1892, sounds the praises of Cleveland and his popularity as the cause; which is pardonable, as the Times has consistently closed its eyes before the blinding light of Cleveland’s preëminence and brilliancy, and refused to see anything else or any other issue in the campaign, arguing that by the magic of the one word, “Cleveland,” victory could be attained. Its leader on the result of the people’s resentment to the crime of “caste” in our country, is a sounding eulogy upon Cleveland, with here and there a glimmer of light breaking upon the vision.

“Meanwhile the victory of Mr. Cleveland is the most signal since the re-election of Lincoln in the last year of the war for the Union.”

It is noticeable in this paragraph that Cleveland’s preëminence so overshadowed, in the mind of the Times, Lincoln, that the prefix of “Mr.” is used before Cleveland’s name, while just plain “Lincoln” is good enough for the man who preserved the Union. One would hardly expect, therefore, that the Times would do more than shout the praises of Cleveland, and give no credit to the sense of the people for their victory. Quoting from their article:—

“The nomination of Mr. Cleveland was dictated by the general sentiment of the party,[Pg 35] inspired wholly by confidence in his integrity, purity, firmness, and sound sense. It was unaided by any organization, promoted by no machine, advocated by no literary bureau, appealed to no base passion. * * * * * * His election is due to the recognition by hundreds of thousands of sound-hearted American citizens, who had not before acted with the Democratic party, that under his guidance, with its avowed policy, that party was a fit depository of the powers of the Government. It is, moreover, preëminently a victory of courage and fidelity to principle. The Chicago Convention, in taking Mr. Cleveland as its candidate, planted itself firmly on the ground of principle.”

It is perfectly plain to be seen that, from a source where the wreath of victory dangles, inscribed with but one word, and that “Cleveland,” one could hardly expect to find information as to the cause that brought about this revolution in the minds of the people. Not that there is any objection to the praises of Cleveland, because all that they say of him is believed by thousands throughout the country, and the same thing is believed to be true of thousands of other men whom the Democratic party might have nominated. Horace Greeley, could he have been taken from his tomb and reanimated, would just as surely have been elected upon the Democratic ticket, had the people believed, as they did, that that ticket represented that “caste,” moneyed aristocracy, to which they were bitterly in their heart of hearts opposed.

The New York World, controlled by one of the brightest, keenest, and shrewdest of men in the journalistic field, in an excellent editorial of November 10, 1892, proceeds to tell what the victory means. And one sentence particularly would be significant, if followed by a little definition of “plutocracy.” Were this word significant enough to cover the objectionable features of the peculiar kind of “caste” which had become identified with the Republican party, it would be sufficient, but such is not the understanding of the word.

New York World, November 10th: “The President elect is the very embodiment of conscientious caution. He is preëminently conservative. His administration will mean economy, reform, retrenchment in every branch of the Government. The victory does mean putting a stop to riot, extravagance, profligacy, and corruption.”

Few, very few, men who voted the Democratic ticket believe that there had been corruption, profligacy, under the Republican administration. The people were not directly affected by the aforesaid charges. The victory did not mean that.

The people are no longer political drones; they are thinking men, moved by sentiments and forces which have not as yet been explained by the most laborious newspaper articles written in[Pg 37] the heat of the campaign, actuated in many cases by partisan interests, party journalists, aristocratic tendencies, and political affiliations. Each would see only his side of the party shield, and that was sure to be golden.

Mr. Cleveland, in his speech at the Manhattan Club, New York, commenting on this fact, states: “The American people have become political, and more thoughtful, and more watchful than they were ten years ago. They are considering now, vastly more than they were then, political principles and party policies, in distinction from party manipulation and distribution of rewards for political services and activities.”

The reason for this is obvious. The country has been flooded of late years with newspapers, brought down to a nominal price; the people have read them thoughtfully; have written to them for explanations of difficulties and doubts arising in their minds, and have profited by these explanations. They have seen paraded in the newspapers the exhibitions of the pride of “caste”; they have seen chronicled the doings of the American Duchess with her divorced duke; they have learned to hate that which the Republican party would have preached to them as the source of all their happiness and prosperity. The Republican party, viewing it only as a means whereby fortunes were accumulated, espoused the[Pg 38] principles which created a desire in the minds of divorced dukes, puppified lords, and degenerate descendants of English nobility, from cupidity, to marry America’s fair daughters. The cheapness of the newspapers placed within the reach of the poorest the information upon which he based his faith. The penny paper is the great leveler of the land.

The New York Herald, of November 13th, commenting on the recent election, takes a biblical text as its theme: “Then were the people of Israel divided into two parts. Half of the people followed Tibni and half followed Omri; but the people that followed Omri prevailed against the people that followed Tibni: so Tibni died and Omri reigned,” and says:—

“In those days, questions in dispute were settled by pitched battles. In these modern times, the arbitrament of war has become wellnigh obsolete, and national policies are decided by ballots instead of bayonets. We doubt if the history of the world records a spectacle as inspiring or instructive as that presented by the American people on Tuesday last, when by an orderly revolution they sent one class of political ideas to the rear, and another class to the front. The party leaders on both sides may have gone into the conflict for personal emolument, or some advantage for their followers, which is scarcely concealed under the words, ‘Patronage and Purposes,’ but the body of the people were the rank[Pg 39] and file—the merchant, mechanic, artisan, and farmer; they cast their votes for the greatest good to the greatest number, because the prosperity of the whole means the prosperity of each.”

In other words, 65,000,000 people have made themselves acquainted with the principles which underlie their government; have learned, through innumerable newspapers, which fall on hill and prairie as thick as snowflakes in December, the value and effect of the differing national policies, and on election day, expressed an intelligent and honest opinion.

In his work on “The American Commonwealth,” James Bryce put the matter in terse and brilliant language, as follows:—

“The parties are not the ultimate force in the conduct of affairs. Public opinion—that is, the mind and conduct of the whole nation—is the opinion of the persons who are included in the parties, for the parties taken together are the nation, and the parties, each claiming to be its true exponent, seek to use it for their purposes. Yet, it stands above the parties, being cooler and larger-minded than they are. It awes party leaders, and holds in check party organization. No one openly ventures to resist it. It is the product of a greater number of minds than in any other country, and it is more indisputably sovereign. It is the central point in the whole American policy.”

The people have spoken. Democracy is triumphant. Democratic principles have prevailed.[Pg 40] They are rooted in the hearts of the common people. The voice of God has spoken. To you, Mr. Cleveland, is entrusted a great task. You took the enemy in flank, you invaded his own territory; you put him upon the defensive, and the defence was unsuccessful, while his offensive operations against the Democratic stronghold crippled and embarrassed. You have the love of the American people. Nourish it; cherish it as the apple of your eye, and your name will go down into history, linked with the name of Jackson, Jefferson, and Abraham Lincoln.

Mr. Thomas Dolan, a well-known manufacturer, of Philadelphia, told some plain truths in an impromptu speech at the Clover Club banquet in that city, shortly after the election. Some parts of it have become public. Mr. Dolan was asked, jokingly, why “it snowed the next day.” His answer had the pungent, incisive, trenchant quality characteristic of the man. “You ask me,” he said, “why it snowed the next day. If you want an answer, I will give it to you; but I must give it in plain terms, for I can speak in no other way. It ‘snowed the next day’ because there was the most stupendous lying in this campaign of any that I have ever known. It has been said here this evening, that this was a campaign without personality and without mud-flinging. That may have been so in the treatment of candidates, but[Pg 41] in reference to others, it was a campaign of shameless lying, vituperation, and calumny. The manufacturers of the country, some of those here to-night, were held up as thieves and robbers who are stealing what belongs to labor. The very men who are giving labor its employment, and are seeking to assure it good wages, were assailed and denounced as its worst enemies. The Democratic press was full of abuse of those who have done their best to build up the prosperity of the country. There never was more unscrupulous lying than there has been in the dishonest and demagogic attempt to array class against class, and it is because of this persistent lying, imposed upon the people for the time being, that ‘it snowed the next day.’” This is, of course, an explanation by a representative Republican, of Republican defeat.

The New York World, of November 20th, gives a better explanation, though not a true one:—

Republican politicians are searching in all manner of out-of-the-way corners for the causes of their party’s defeat. They are carefully overlooking the actual cause which lies open to less prejudiced view. The Republican party was defeated because its politicians have strayed away from honest and patriotic courses. They have worshiped strange gods; they have allied themselves and their party with the plutocratic interests of the country; they have betrayed the people[Pg 42] to the monopolists; they have sought to substitute money for manhood as the controlling power; they have tried to buy elections; they have squandered the substance of the country, in order that there might be no reduction in oppressive taxes, which indirectly, but enormously, benefit a favored class. The party is punished for its sins. It has forfeited popular confidence by its misconduct. It has ceased to deserve power, and the people have taken power from it.

Murat Halstead, a deep thinker, wielding a forceful pen, writing about the recent mistakes of the Republican party, says:—

“There was too much ‘Tariff Reform’ and too little attention to practical politics in the conduct of the recent Republican campaign. The mistakes of the Republican party were many. They attempted too much tariff reform and too much ballot reform and too much civil service reform, and strangely mingled too little and too great attention to practical politics. The high character of the Harrison administration was not of the ‘fetching’ sort. There were strong and distinguished Republicans sharply opposed to another Harrison administration, in California, Nevada, Colorado, Kansas, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, Maine, and several of the Southern States. In some States, there was grief because he did too much for Senators and too little for Representatives, and in others, the Senators suffered because the Representatives were especially recognized; and there were scores of personal irritations that were nothing in themselves, but in[Pg 43] the aggregate, became an element of mischief that was magnified into disaster. The ranks seemed solid toward the close of the campaign, but there were weaknesses, here and there, known to those whose information was from the interior. There were three things that seemed to give assurances of Republican success: First, the country was prosperous, and the economic value of protection seemed to be demonstrated, and nowhere more clearly than in the Homestead strike. Second, it was the testimony of home statistics and foreign news that the McKinley tariff was helping our workingmen, and had a powerful tendency to the transfer of industries to our shores, while the reciprocity treaties were aiding our manufacturers and food producers alike to new markets. Two of the grandest steamships on the Atlantic, one the swiftest ever built, were to hoist the stars and stripes and be transferred from the British navy to our own, and this was understood to be the dawn of an era of restoration of our lost strength on the seas. Third, President Harrison was revealed to the nation in his administration as a man of the highest order of ability, of industry that never wavered, and will that was unflinching and executive, while he was the readiest, most varied, and striking public speaker of his time. We have had no President with more influence with his own administration than he wielded. The Republicans have so long been accustomed to holding at least a veto on the Democratic party, that they could not be aroused to the full appreciation of the danger of giving that party the whole power of Government. The masses of men declined, in this[Pg 44] fast age and rapidly-developing country, to be warned by the events of more than thirty years ago. The first surprise was public apathy. There were few displays. It was not a great summer and autumn for brass bands and torches. It was not a great year for newspapers. Those that largely increased their circulation did it outside of presidential excitements and political attractions. The second surprise was the immense registration. Then it was seen that comparative public quietude did not mean lack of interest. Everybody knew something was going to happen. Republicans were cheered, and said: ‘This means the quiet vote. The secret ballot is with us. Times are good. There’ll be a big vote, on the quiet, to let well enough alone. Harrison is a great President, and it is the will of the people that he shall continue his good works.’ The Democrats said: ‘The secret ballot is with us this time. The workingman is dissatisfied. He gets more wages than he does abroad, but he holds that he is robbed of his share of the riches of the land, and the quiet vote is with us. The workshops are for a change.’ There was much in what they said. The workingmen gave the Democrats New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Indiana, Illinois, and the election; but was there ever such a combination of antagonisms gathered into an opposition force, to carry the Government by storm, as that which the Democracy was enabled to make? Contrast the Democratic platforms of Connecticut and Kentucky. They are more flagrantly opposed to each other than the Minneapolis and Chicago papers. Connecticut is rankly Protection, and Kentucky[Pg 45] rabidly Free Trade. Both are for freedom. The Democrats joined with the Populists in several States to give Weaver votes, and in other States terrorized, threatened, assaulted, and cheated his opponents.

“Take the money matters; we find the Democracy are red dog, wild cat, rag baby, silver pig, or gold bug, according to the local demands. They are all for Cleveland, however. The very ferocity of the personal factions of the Democratic party in New York was converted into steam power to drive the Cleveland machine. There was emulation in his service, between his old friends and enemies; and the enemies of other days exceeded the friends in the competitive struggle. The Democrats who hoped he would be defeated, and there were many thousands of them, were the most particular of men to vote for him because they felt their future in the party depended upon their ‘record.’ What they wanted was to be beaten in the ‘give-a-way game,’ and they trusted to the last to be able to say: ‘There, you see how it is; we told you he was impossible. We’ve done all we could, and it is just as we said.’

“When the shriekers of calamity are able to harness the prosperity of the country and turn it against the Government; when the beneficiaries of a great policy turn against it and vote it down; when those who lick the cream of good times, hunger and thirst for experimental changes; when opposing interests and factions, principles and purposes, personalities and all the potencies of all the fads, can be united for a common purpose, there are surprises for citizens who have[Pg 46] held in a commonplace way, but the unreasonable and inconsistent, the unwarrantable and the illogical, must also be the impracticable.

“It has been remarked of St. Petersburg, that in case of the occurrence of, first, a great flood in the Neva; second, extraordinary high tide; third, a long, strong blow from the gulf, the city must be overwhelmed. The years, the decades, and the centuries come and go without the disaster. It was long understood in the Ohio valley that there would be a flood beating all in history, and competing with Indian tradition, if there happened, in the order set down, these events: (1) during a wintry night, a sudden general rain, followed quickly by a freeze, covering Western New York and Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Kentucky, West North Carolina, Tennessee, Ohio, and Indiana with a sheet of ice; (2) if, upon this vast glassy surface, there should fall a series of heavy snows; (3) if, upon the snow, there should come rain, beginning near the Mississippi, which should be full and filling all the streams, locking them from the mouths against speedy discharge; (4) and if there followed rain-storms for a week, so distributed as to boom all the rivers in order from west to east; (5) culminating with three tremendous downpours over all the mountain regions, sweeping from the glazed earth the whole accumulation of snows, and so timed as to tumble all the floods at once into the Ohio, whose channel has been obstructed by the piers of many bridges, and a habit of encroaching upon it, then the river would make a demonstration memorable and marvelous. All this took place, just as we have[Pg 47] set it down, five winters ago, and the high-water-mark at Cincinnati is seventy feet above low-water-mark. Up to this, the boast of the old folks in the valley was, that they had seen ‘the flood of ’32,’ and there could never be anything like it. The world did not now-a-days afford such spectacles as they had beheld in ’32! A few dingy old houses had incredible high-water ’32 marks upon it. If the river looked angry, and rushed through a few low streets, the veterans would say: ‘You should have seen the flood of ’32. ’Twas the biggest thing we ever had, or ever will have. But they do say the Indians said, they once hitched canoes to walnut trees away above the ’32 mark; but them Indians was such liars.’ The flood of 1885 beat that of 1832 two feet, and the flood of 1887 was nearly seven feet above the old high-water-mark. Averaging the chances, it will not happen again for one hundred years. The river Rhine has a way of rising at the same time with the Ohio, and was higher in 1885 than it had been in two hundred years. There was favoring the Democratic party this year, such a combination of circumstances as that which made an Ohio flood seem a prodigy. The high-water-mark is astounding. The country is still here. There is something to eat, and even to drink. Such a Democratic disaster will not be due again for a generation.”

John Russell Young, the brilliant journalist, writing in the Philadelphia Evening Star, quoted by the New York Press, of November 19th, has his explanation for the defeat ready: “Communities[Pg 48] are like men, like women, like children, like dogs. Why do they do it? Why does a man buy wildcat stocks? Why does a woman rave over a bonnet, or marry a student of divinity? Why? Because we are more or less fools, even as the good Lord made us fools, and if we were not fools, it would be a teasing, tiresome world. Why does a boy go to bed as cross as the roaring forties after his Christmas dinner? He has had too much mince pie. The country has had too much mince pie. It kicks. It kicked after Quincy Adams, the best of all Presidents. It kicked after Van Buren, who was as downy as an Angora cat. It kicked after Arthur, whose administration was sunshine. It kicks after Harrison, the radiant, prosperous Government. Too much mince pie! Cleveland comes in because of his medicinal properties. We must take to our herbs now and then.”

The practical politicians of the Republican party feel it incumbent upon them to give their version of the great defeat. James S. Clarkson, who, for many years, has been a guiding spirit among Republican leaders, of the late verdict says: “It is an order from the American people for a change in the industrial economic policy of the Government.” He charges that the Republican party has lost strength and votes among the rich and among the people of independent[Pg 49] means, who now want cheap labor; also among the workingmen, who have come to believe that free trade will cheapen the expense of living, while the Trades-Unions will still keep up their wages. He says: “The result is not a personal defeat of President Harrison, nor really a defeat of the party. It was a Protection defeat, a repudiation of high tariff, a Republican reverse in a field where it put aside all the nobler issues, and staked everything on economic and mercenary issues.”

The surprising overturn of affairs in the distinctly Republican State of Illinois is accounted for by Senator Cullom by distinctive issues other than the McKinley and Force Bills: “Our losses in this State are mainly due to the school question, but in the nation at large they are due, in my judgment, to the passage of the McKinley law, and the impression in the minds of the masses in regard to it. When it was passed, the people expected us to revise the tariff, and revise it in the direction of reducing duties, and, while we did make reductions, they were dissatisfied because so many increases were made. When the bill came to the Senate from the House, we cut many of these in pieces, but, when it went back to the House and got into the Conference Committee, enough of them were restored to put us on the defensive and at a great disadvantage. Yes, I[Pg 50] think our defeat can fairly be attributed to the McKinley Bill,” and Senator Cullom represents the State of Abraham Lincoln. The prairies that gave breath to the typical champion of the people, produced this statesman, who, representing the State of a man who stands first in the minds of the people as their representative, sees only the indications of the mercenary spirit of the people. How Abraham Lincoln would have gauged correctly, instinctively, the heart-throbs of the people whom he assumed to represent in the councils of the nation!

Senator Cullom, in his opinion, mirrors only the reflection, cast upon the surface of his mind, by the aristocratic and multi-millionaired Senate of the Union, in which he occupies a seat. He sees only the cold, hard dollars and cents at issue.

He does not appreciate, as Abraham Lincoln would have done, the feeling of the people whom he pretends to represent. In every prairie home of Illinois there was an insulted wife or mother by the assumed distinctions made by the would-be aristocrats of the Republican party. Stevenson’s speeches awakened no echo in their hearts, except that it gave an opportunity for the exhibition of the old, old story, written by the swords of the Anglo-Saxon people, “Caste is a crime.” That the State of all States, Illinois, which gave to the[Pg 51] Federal Union Abraham Lincoln, should be presented in the sedate Senate of the Union, by a man whose views are so narrowed by the horizon of his own thoughts as to express a sentiment like the foregoing; namely, that the people were governed in their selection of their representative, the Chief Magistrate, by the power of the pocketbook; to be so unresponsive to the throbbing hearts of his constituency, is most disappointing.

Editors can be at times epigrammatic, and this election has brought forth some keen and trenchant opinions on the causes of defeat. Here are a few of them. All of them seek, as a child playing blind-man’s-buff, in darkness, for that which, had the bandage which blinds them been removed from their eyes, would have been made plain, and which was occasioned by their own presumption in assuming to measure the depths and power of the people’s feelings and impulses:—

Clark Howell, in the Atlanta Constitution, says: “Now, after thirty-one years, since Buchanan’s Democratic administration, another political revolution has taken place, and, as a result, the election of 1852, which destroyed the Whig party, is repeated in the Waterloo defeat of the Republican party, and the question is, will this defeat finish the career of that party? The probability is that it will.”

The Atlanta Constitution, of November 17th, in a brisk editorial, states that “Colonel J. B. McCullagh, the esteemed editor of the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, is not very happy. Naturally, he has his regrets and his hours of gloom, but he is not so miserable that he is unable to appreciate a mystery that crosses and recrosses his path in broad daylight. He cannot, for instance, understand the post-mortem talk of his party leaders. ‘Curiously enough,’ he says, ‘they are now claiming that Harrison was defeated by the very things which they then said must insure his success.’ Of course, these statements have a humorous twang, but it seems to us that a Republican as prominent as Colonel McCullagh would be willing to drop a veil over these gibbering evidences of human frailty. After all is said, there is but one trouble with the Republicans. They have but one regret. Editor Grubb, of Darien, outlined the situation very aptly when he said that the only thing that the Republicans desired, was the opportunity to steal a State. They are perfectly willing to see Harrison defeated; they are perfectly willing to retire from the control of the government; the only bitterness they feel is the realization of the fact that they failed to steal a State. They stole three Southern States in 1876. They stole two Northern States in 1890, and they stole a Western State last year, but they have failed to steal a[Pg 53] single one in 1892. It is no wonder they are going about talking wildly and rolling their eyes. These are the symptoms of paresis, and, under the circumstances, Senator McCullagh ought to forgive them. The grief and disappointment of the Republican leaders are natural; a general election, and not a State stolen! Surely, their hands have lost their cunning. They made a tremendous effort to keep up their record. They tried to steal Delaware and West Virginia and Connecticut, but everywhere the Democrats met them and exposed their plans. The result was, that they failed to steal even one State. Under the circumstances, we think editor McCullagh should treat his brethren gently; he should not make satellite allusions to their troubles. Let them gibber.”

Thank God, with our Australian Ballot system, each free-born American citizen carries with him into the voter’s booth, if he be at all sensitive, and clothed with an enlightened conscience, the same awful sense of responsibility with which the enlightened and tender-conscienced Catholic enters the sacred realm of the confessional-box. Tremendous issues are at stake. He feels their force, and arises to the occasion, as he ever has done when the exercise of worth, virtue, or virility has been required upon his part, and of the great mass of the common people, Daniel Webster,[Pg 54] Henry Clay, Abraham Lincoln, furnish fair samples of the people’s worth, virtue, and virility.

The Buffalo Commercial, than which there is no paper in the State of New York in possession of more perspicacity and political common-sense, in speaking of Senator Allison, a Republican leader of the Senate, states that just before leaving for Europe he intimated that the McKinley Bill was too strong a specific for the Republican party. “You remember,” he said, “that epitaph on the tombstone of the young man who died before his time: ‘I was well; medicine made me ill, and here I lie.’”

The Illinois State Journal remarks: “Until the post-mortem is held, it is, perhaps, just as well not to be certain what it was that hit the G. O. P. last Tuesday. It may have been the McKinley Bill, or the Homestead matter, or the Lutheran business, or the naturalized vote, or several other things, and then it may have been a complication of all these diseases.” Thou wise physician, who would lose sight of the most important evidence of the disease, the discontent of the people, the artificial class distinction created by the sham aristocracy of America, the diagnosis of the disease, called discontent, as made by the press generally, is as faulty and erroneous as would be the opinion of the quack who would call measles, smallpox. Every symptom of the displeasure of[Pg 55] the people at the prevalence of the crime of “caste” in our country was evident; yet, apparently, the most learned failed to discern it.

The Toledo Bee says: “The Republican party is dead. The step backward has been taken, and it was a step back that led the party over the precipice of power into the depths of oblivion. The Democratic party has relegated the boodlers, the spoilsmen, and the factional leaders to the rear. What is there left for us to live for?”

Says the Louisville Courier-Journal: “The people will have none of its high tariffs, and none of its Force Bills; but without its high tariffs and its Force Bills, it is only an organized hunt for official plunder. The people will not support it in its old course, and will not believe its brittle promises of reform.”

“‘High tariff did it,’ said Mr. Harrison; but in taking satisfaction for his defeat out of the Napoleonic McKinley, the President is less than just to the magnetic Blaine; for, if high tariff caused the explosion, despite the ‘reciprocity attachment,’ what might it not have done without that little Pan-American vent-hole?” This from the Philadelphia Record.

The President, had he combined the magnetism of Blaine, the Napoleonic ability of McKinley,—yea, had he, in fact, borne the magical name of Lincoln,—could not possibly have been re-elected,[Pg 56] for the people were opposed to the ideas of “caste,” fostered with such care by the members of the Republican party, in whom, in some mystical manner, have become concentrated the wealth and objectionable characteristics which tended to make the Southern cavalier so unpopular in 1860. The people, in their wrath, would have risen against any party so besmeared with the slime of that noxious crime.

The Atlanta Constitution, of November 17th, claims that “the leaders of the two great parties have had a good deal to say during the past few months about ‘the campaign of education.’ In the main, this phrase very correctly describes the work of both parties. Republican speakers and journalists work night and day to convince the people of the benefits of high Protection. On the other hand, the Democrats are equally active in exposing the true inwardness of McKinleyism and class legislation. This educational literature covered the country, and the average voter got a clearer insight of the questions at issue than he ever had before. One effort of this campaign of education was to eliminate personalities; principles and measures were discussed, and the candidates escaped the usual mudslinging. Another result is seen in the sweeping and decisive nature of the vote. The revolution was so complete that the defeated side realized the utter absurdity[Pg 57] of indulging in any bitter complaints, with the great mass of American people arrayed against them. Our victory was so crushing, that it absolutely restored something like good feeling; and we find Whitelaw Reid and Chauncey Depew saying pleasant things to Mr. Cleveland at a banquet, and speaking of their defeat in a humorous fashion. This would not have been the case, had the election been close and only a bare majority of electoral votes for the successful ticket. Altogether, the country has good reason to be satisfied with its campaign of education. It has purified our politics, wiped out sectional lines, and made our people more thoroughly American than ever.”

And for the erasure of sectionalism, God be thanked! but that a man of Mr. Clark Howell’s preëminent ability should have wandered around so near to the object of his search, the cause of the Republican party’s defeat, and not found it, is astonishing. In his own home, the State of Georgia, the Empire State of the South, and as editor of the leading paper in the State, that he should be so oblivious to the fact that the election, by the votes of the people, was a protest upon the part of the people against the assumption by the rich, that such a thing as “caste” could be possible in America.

Georgia, of all the Southern States, is preëminently industrial. Oglethorpe, when he first[Pg 58] settled on the banks of the Savannah river, was himself surrounded by the poor debtors of England. The Salzburgers, who sought the shores of the uninhabited, uncivilized, new colony, were poor, uncultured people. Georgia never possessed, as a colony or as a State, the aristocratic tendencies of its neighbor, South Carolina. The foremost men have ever been essentially of the people; her settlers largely of the Democratic masses; the names preëminent in her history are the names of industrial New England. So Democratic is and was the State of Georgia, that her most eminent son, Alexander H. Stevens, had to be weaned away reluctantly from the doctrine of which Abraham Lincoln was the personification. Since the war, the State of Georgia more readily adapted herself to the new condition created by the result of the struggle. It was never a State of tremendous landed proprietors. The influx of emigration from the crowded Northern States found readier assimilation in the State of Georgia than in any other Southern State. In that State, the negro sooner realized his responsibilities as a citizen of the South, sooner became convinced that his best and wisest course was to merge himself into the large class of toilers and laborers in the commonwealth. That a man with the opportunity, ability, and brilliancy of Clark Howell, should become so utterly befogged by the mists[Pg 59] arising from the marsh of old party cries and principles, should fail to recognize that the tremendous majority accorded the Democratic candidate, was but an exhibition of that spirit which has pervaded the State of Georgia from its embryonic existence on the Savannah river; that Mr. Howell should have forgotten the lesson taught by the forefathers of the Georgians of to-day, that Democracy was one of the essential elements to the happiness of the citizens, settlement, colony, commonwealth, and State, is passing strange. The very negro, upon becoming a Georgian and a citizen, became a Democrat, almost as a matter resulting from the atmosphere he breathed. Georgia’s vast majority for the Democratic nominee was not rolled up except by the aid of the negro, who, in his heart of hearts, is a Democrat, and the appeals of the Republican party to his gratitude, claiming that they were the emancipators of his race, were as futile as was the waving of the bloody shirt in the face of the veterans of the North. The negroes of the State of Georgia joined with their fellow-laborers of the Anglo-Saxon race, to give added weight to the opposition of the masses against “caste” in our country.

The Mail and Express, in an editorial of November 9th, says: “If Benjamin Harrison is defeated, the people of this country, by their[Pg 60] ballots yesterday, decided again to try the experiment of the Democratic administration. It is most extraordinary and unusual for the American people to seek a change in administration at a time of unwonted prosperity; to render a verdict in favor of a change, while the working masses are everywhere busily employed, while farmers are reaping their richest harvests, factories running day and night, and building extensions and our foreign trade growing with rapid strides, all under the beneficent influences of Republican policy, wisely and faithfully administered by a President whose conduct of affairs has been conspicuously conservative, successful, acceptable, and clean. If Grover Cleveland has been elected, a change in administration has been ordered. What shall we get in return? We shall see! The triumph of Democracy would mean a radical change in our economical policy. It would mean the selection for Vice-President of a man whose political record has stamped him as unsafe, untrustworthy, and conspicuously unfit for the high office to which he has been called. An ardent advocate of the unlimited issue of greenbacks and fraudulent silver; a bitter opponent of National Banks, and the advocate of State Banks issue; outspoken in his demand for the imposition of the abandoned and inquisitorial income tax, Mr. Stevenson would, after the 4th of March, occupy a place[Pg 61] separated from the Executive head of this Government by the frail tenure of a single life. In the Senate, the highest legislative body in the land, over which Mr. Stevenson, as Vice-President, would preside, a Senate which may possibly have a Democratic majority, his influence in favor of economic and financial heresies would be potential. Let the people bear in mind the peace, the happiness, and the prosperity they now enjoy. When anxiety and unrest come, as they speedily would, with the renewed agitation in the next Congress, of an attack upon our protective tariff; when the spindles of our mills are silent, the forges black with ashes, our looms yellow with rust, and unemployed men clamor here as they are clamoring to-day in the streets of London and Lancashire against the reduction of wages, let them listen to the plausible excuses and fine-spun prevarications of the Free Trade tariff reformers, who will be responsible. And if, as Vice-President, he should do the evil he can do by aiding the meddlers with our financial and taxation systems, the honest money men of New York and New England, of Illinois and Indiana, who voted for him because he was associated with their idolized free trade candidate, would have only themselves to thank for the prospect of disaster and panic they might face. They would then pay the penalty of their reckless inconsideration. Protection[Pg 62] for American homes, for American workingmen and American farmers, an honest dollar for honest men, and a policy of free trade extension by the beneficent influences of reciprocity, may all suffer assaults in the four years to come, but we can trust the sober, second judgment of the American people, in the light of another but recent experience with the free trade and fraudulent silver Democracy, to do again in 1896 what it did with that party at the close of the first Cleveland experiment, and turn the incompetents out.”

It is most extraordinary and unusual for the American people to seek a change in the administration at a time of unwonted prosperity, but the inward agitation of soul at the thought of great wrongs committed by a pretended beneficent party led to the revolution of ’92, in very much the same manner as inward agitation on another subject brought about that which placed Abraham Lincoln in the Presidential Chair. The American workman is above the American dollar!

The New York World, in an editorial of November 16th, says: “The Iron Trade Review is putting the manufacturers up to a dodge in order to make the people sorry that they voted for Mr. Cleveland. Its advice is that the manufacturers reduce the wages of their workingmen ‘to fortify themselves in advance in view of the increasing probabilities of destructive foreign competition.’[Pg 63] Is this an indication of the kindly feeling entertained by the Protectionists for their workingmen? They have professed that their tax policy was maintained for the purpose of increasing wages. They have been charged with misrepresentation; and they are now advised by one of their organs to prove that the charge is true, by making the wage-earners suffer in order that revenue reform may become unpopular. Nothing could better show the dishonesty of the Protection claim that the tariff exists for the workingman. If that claim were true, the manufacturers would resist every tendency toward downward wages, instead of pushing them down in order to gain an advantage for themselves in a political controversy. The wages of labor are regulated by the supply and demand of the labor market, and the people who would cut down wages, not because they must, but because they want to revenge themselves for a Democratic victory by making the workingman suffer, are the people who have been insisting that the McKinley law repealed the law of supply and demand, and that they are the true and unselfish benefactors of the workingmen. Happily, the next President is a Democrat.”

General JAMES B. WEAVER.

Presidential Candidate of the People’s Party, 1892.

The workmen of our country, it is true, want better times, cheaper clothing, the doing away with trusts, and many other desirable changes; but far more than this, they feel the need of the absolute crushing out of the last vestige of “caste.” They at last realize that “caste” is a crime; and the common people have, at heart, no sympathy with criminals, and especially criminals of that class. The common people stay at home, work hard, and very seldom have need to “go to Canada,” or take a flying trip to Southern Europe. Their sins are mainly those of passion. At their best, they are kindly disposed to their fellows; but they are human. They feel a snub from their employer or employer’s son as keenly as their honest, hard-working wives and daughters feel the haughty stare and condescending patronage of Madame Crœsus and her bejewelled daughters. Here we offer our readers some explanations, given by the common, average American citizen, for the defeat of the Republican party at the polls on November 5th. The article is taken from the pages of the New York Tribune, November 21,[Pg 66] 1892, the official organ of the Republican Vice-Presidential candidate, and therefore entitled to more than ordinary consideration. The article is headed “The General Discontent.”

It consists of talks with the people about the recent election in New York State and Vermont. It is, largely, the observations of a correspondent who has walked through the State, asking farmers and workingmen why they voted for Cleveland. Let it not be forgotten that Whitelaw Reid is the editor of this paper.

“The politician who attempts to explain defeat is ‘crying over spilt milk.’ The newspaper which tells ‘how it was done’ is ‘whining.’ The writer of a political obituary has hardly an enviable task. A defeated party is supposed to accept with philosophical resignation the rejection of pet policies, and with the calmness of the fatalist, tell itself that it ‘was to have been.’ The reasons given for the result of the recent election are as numerous as there are differences in the minds of the two parties. Some say that the desire for free trade is the cause of the Republican overthrow. Others, that the thing that did it is the McKinley bill; others again, that the people want the ‘repeal of the Bank Tax law’; but to him that looks beneath the surface, there is ample evidence that the defeat of the Republican party is not mainly due to the ‘unpopularity’ of its candidates, nor to the love which the people are said to bear for Grover Cleveland; not to the McKinley bill, nor to any ‘desire on the part of the people for free trade;’ not because free silver is or is not wanted. Not through the ‘superb generalship’ of the Democratic National Committee was a victory gained, nor was the battle lost through the ‘lamentable incompetency’ of the Republican leaders. The chief cause of Republican defeat and Democratic victory is the modern tendency toward socialism.

“This statement by no means implies that the socialistic[Pg 67] propaganda has taken a firm hold upon the citizen of the United States, or that its tenets have but to be sowed in American soil to bear an abundant harvest. The people have not subscribed to the mild doctrines of Henry George, nor to the more radical and incendiary plans of John Burns, nor do they place confidence in the ability or stability of the leaders of the ‘New Order of Things.’ They have not the slightest desire to overturn existing government; the ravings of the Anarchists they repudiate altogether.