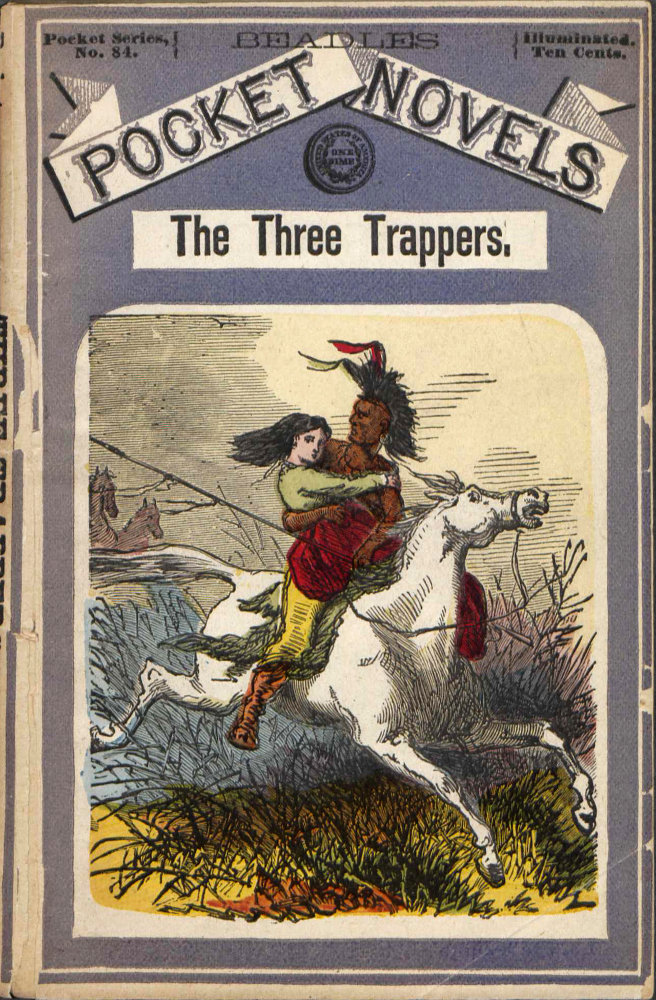

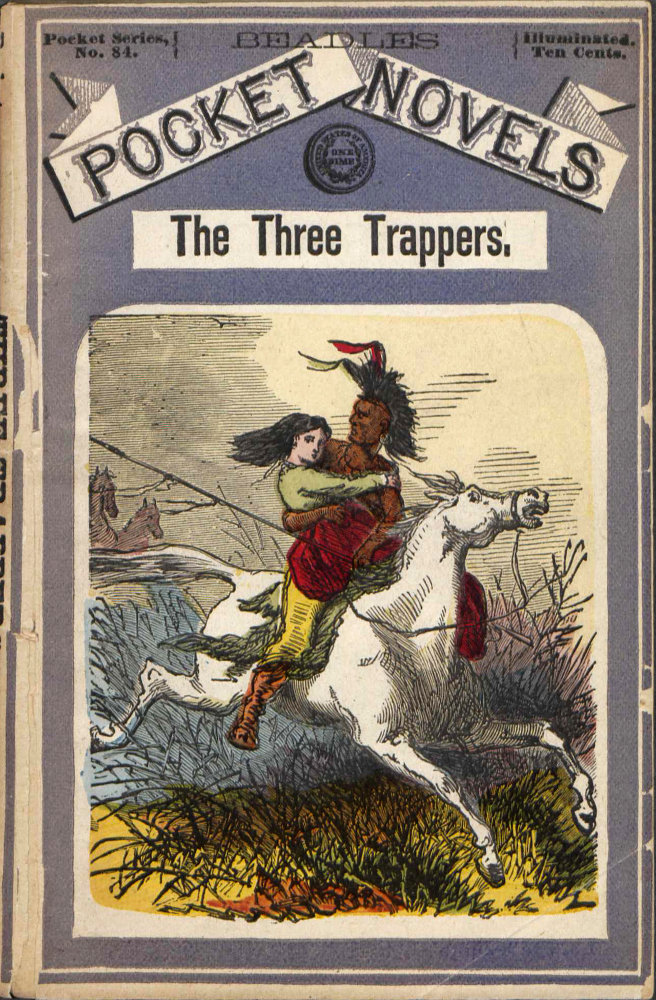

Title: The Three Trappers; or, The Apache Chief's Ruse

Author: Edward Sylvester Ellis

Release date: September 15, 2021 [eBook #66309]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: David Edwards, Stephen Hutcheson, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (Northern Illinois University Digital Library)

BY SEELIN ROBINS,

Author of “The Specter Chief.”

NEW YORK:

BEADLE AND ADAMS, PUBLISHERS,

98 WILLIAM STREET.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1871, by

FRANK STARR & CO.,

In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

It was now quite late in the afternoon, and Fred Wainwright reined up his mustang, and from his position took a survey of the surrounding prairie. On his right stretched the broad dusty plain, broken by some rough hills, and on his left wound the Gila, while in the distance could be detected the faint blue of the Maggolien Mountains.

But it was little heed he paid to the natural beauties of the scene, for an uncomfortable fear had taken possession of him during the last hour. Once or twice he was sure he had detected, off towards the mountains signs of Comanche Indians, and he was well satisfied that if such were the case they had assuredly seen him, and just now he was speculating upon the best line of retreat if such were the case.

“If they are off there, and set their eyes on me,” he speculated, “the only chance for me is towards the Gila, and what can I do there?”

He might well ask the question, for it was one which would probably require a speedy answer. The Comanches, as are well known, are among the most daring riders and bravest red men on the American Continent, and when they take it into their heads to 10 follow up an enemy, one of three things is certain—his destruction, a desperate fight or a skilful escape.

The young hunter had no desire to encounter these specimens of aboriginal cavalry, for he was certain in the first place that there were half a dozen of them, and that it would be madness to stand his ground, while his chances of eluding them were exceedingly dubious. Although mounted on a fine mustang, there was little doubt but what the Indians were equally well mounted, and he had little prospect of success in a trial of speed.

There was only one thing in his favor, and that was that night was close at hand. He was somewhat in the situation of the mariner when pursued by the pirate, who sees his only hope of life in the friendly darkness which is closing around. The young hunter looked at the low descending sun, and wondered what kept it so long above the horizon, and then he scanned every portion of the sky, to see whether no clouds were gathering in masses, which would increase the intensity of the darkness. But the sky was clear, although he remembered that there was no moon, and when night should fairly come it would be one of Egyptian gloom, which would give him all the shelter he wished.

At the precise point where the young hunter was journeying was a mass of tall grass, which partially concealed himself and horse, and which, as a natural consequence, he was reluctant to leave so long as he was sure that danger threatened him. His little mustang advanced slowly, his rider holding a tight rein and glancing toward the river, and then toward the hills on the right, from which he expected each moment to see the screeching Comanches emerge and thunder down toward him.

But as the sun dipped below the horizon the young hunter began to take heart.

“If they give me an hour longer, I think my 11 chances will be good,” he muttered, growing more anxious each moment.

At one point in the hills he noticed a broken place, a sort of pass, from which he seemed to feel a premonition that the Indians would sally forth to make their attack; so before coming opposite he reined up, determined to proceed no further until it was dark enough to be safe.

He had sat in this position a half an hour or so, and the gloom was already settling over the prairie, when a succession of terrific yells struck upon his ear, and glancing toward the hills, he saw half a dozen Comanches thundering down toward him. The hunter at once threw himself off his horse, and resting his rifle on his back, sighted at the approaching redskins. They were nigh enough to be in range, and satisfied that they could be intimidated in no other way, he took a quick aim and fired.

Fred Wainwright possessed an extraordinary skill in the use of the rifle, and the shriek and the frantic flinging up of the arms, and the headlong stumble from his horse of the leading Comanche, showed that the fright of his situation had not rendered his nerves unsteady.

This decided action had the effect of checking the tumultuous advance for a few moments; but the hunter had been in the South-West long enough to understand the nature of these Comanches, and he knew they would soon be after him again. Springing on his horse therefore, he wheeled about without a moment’s delay, and started at full speed on his back track.

Wainwright soon made the gratifying discovery that the speed of his own mustang was equal to that of the animals bestrode by the Comanches, and that even for a time he steadily drew away from them. But his own horse was jaded with half a day’s tramp, and could maintain this tremendous gait for comparatively a short period, while those of the Indians were 12 fresh and vigorous and could not fail soon to draw nigh him.

“However, if the fellow keeps this up for a half hour longer, we shall care nothing for them.”

The little animal strained every nerve, and worked as if he knew the fate of himself and master was depending upon his efforts. The young hunter glanced over his shoulder and could just discern his followers through the gloom, they still shouting and yelling like madmen, as if they sought to paralyze him through great terror. He loaded his gun as he rode, and several times was on the point of turning and exchanging shots with them; but he did not forget there were two parties to the business, and that their return shots might either kill or wound himself or mustang, the ultimate result in each case being the same. So he gave his whole attention to getting over the prairie as fast as possible.

About fifteen minutes had elapsed when the crack of a rifle rung out upon the air, and the bullet whistled within a few feet of the head of the fugitive. He again looked back and could see nothing of his pursuers. At this juncture he struck in among some tall grass similar to that in which he halted when he first beheld the Comanches; and at the same instant he saw that his beast was rapidly giving out.

He hated to part with him but it could not be helped. Delay would be fatal, and reining his horse down to a moderate canter, he sprang to the earth and gave him a blow, which sent him with renewed speed on his way.

Then running rapidly a few rods the hunter dropped flat on his face and listened. All the time he heard the thundering of the approaching horsemen, but he did not dare to raise his head to look. They came nearer and nearer, and the next moment had passed by and for the present he was safe.

Not doubting but that they would speedily come up with the fleeing mustang and discover the ruse 13 played upon them, Wainwright arose to his feet and made all haste toward the Gila.

By this time it was very dark and he was guided only by a general knowledge of the direction in which it lay, and by the sound of its gentle flowing. Once along its steep banks he felt sure of being able to conceal himself, and, if needful, of throwing his enemies off his trail entirely, should they attempt pursuit, when it again became light.

Hurrying thus carelessly forward he committed a natural blunder but one which made him ashamed of himself. He walked straight off the bank a dozen feet high, dropping within a yard of a small camp fire, around which were seated two trappers smoking their pipes.

“Hullo, stranger, did you drop from the clouds?” asked one of them, merely turning his head without changing his position. The other turned his eyes slightly but did nothing more. “This ’yer what I call a new style of introducing yourself into gentlemen’s society; shoot me for a beaver if it aint!”

“That it is,” laughed Wainwright, “but you see I was in quite a hurry!”

“What made you in such a hurry?”

“I was fleeing from Indians——”

“What’s that?” demanded both of them in a breath.

“I was fleeing from Indians, and was looking more behind than in front of me.”

“That yer’s what I call a different story,” exclaimed the oldest, springing up and dashing the burning embers apart, so as to extinguish the light as soon as possible. It required but a few moments thoroughly to complete the work, when he turned to Wainwright and asked in a whisper:

“Mought they be close at hand, stranger?”

“I don’t think they are.”

“Have you time to talk a few minutes?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Then just squat yourself on the ground and tell us all about this scrape you ’pear to have got yourself into.”

Our hero did as requested, giving a succinct account of what we have told the reader, beginning the narration at precisely the same point in which we did, and carrying it up to his “stepping off” the bank. The two trappers listened respectfully until he was done, when one of them gave an expressive grunt.

“'Younker, you don’t look as if you had two faces, and I make no doubt you’ve told us the truth; but it was qua’r you should happen to be trampin’ alone so far away from the settlement.”

“I was with a party of hunters this morning, but became separated from them and was on my return to the camp when I was shut off in the manner I have told you.”

“Do you want to get back to them?”

“I aint particular,” laughed the young hunter, with a peculiar expression. “It aint likely they have waited an hour for me when they discovered my absence, and so I should be at a loss to know where to look for them.”

“Wal, it’s all the same to us,” said the trapper; “you don’t look like a scamp, and you can stay with us, if you want to do so.”

“You see, furthermore, that I have lost my horse, and shall have to take it afoot until I can buy or capture another.”

“We can fix that up easy enough,” grunted the trapper. “My hoss Blue Blazes can carry all that can get on his back, and we can give you a lift till you can scare up an animile of some kind or other.”

It was plain that the trappers were really kind at heart, and were anxious to give the young hunter a “lift.” They were rough in their manner and speech but the diamond is frequently forbidding in its appearance until it is polished, and the wonderful gem displayed.

While this trapper was conversing with the stranger, his companion had stealthily made his way down the bank some distance, where he had clambered up on the plain, and made a reconnoissance to assure himself that the “coast was clear.” Discovering nothing suspicious, he had turned back again and speedily rejoined the other two.

The fire having completely gone out they were left in entire darkness sitting together on the bank of the Gila.

One of the trappers was short, muscular, with a compact frame, resembling in physique the renowned Kit Carson. His name was George Harling, and he hailed from Missouri, and was a hunter and trapper of a dozen years experience. He was generally mild, quick and genial tempered, but when in the Comanche fight, or when on the trail of some of the daring marauders of the northern tribes, he was a perfect terror, fearless, dashing and heedless of all danger.

The second hunter who hitherto had maintained the principal part of the conversation with Wainwright was a tall, lank, bony individual, restless in manner and sometimes impulsive in speech, was called Ward Lancaster, and seemed to have tramped in every part of the country west of the Mississippi; for you could not mention a tribe of Indians, or a peculiar locality, but what he had been there, and had something interesting to tell about it.

He was about fifty years of age, with not a gray hair in his head, and with as gleaming an eye as he possessed thirty years before, when he first placed his foot on the western bank of the Father of Waters, and slinging his rifle over his shoulder, plunged into the vast wilderness, an eager sharer in the adventures and dangers that awaited him.

Ward was a pleasant, even tempered individual, who, when led into the ambush, and fighting desperately the dusky demons who were swarming around him, did so as cooly and cautiously as he galloped 16 over the billowy prairie. He was one of those individuals who seemed born to act as guide and director for parties traversing those regions, where it seems to a man of ordinary ability, fully a lifetime would be required to gain a comparatively slight knowledge. His instinct was never known to be at fault. When in the midst of the immense arid plains, which stretched away on every hand, until like the ocean it joined the sky; in the centre of these vast tracts, with man and beast famishing for water, and when no one else could see the clue, by which to escape from the dreadful situation, Ward displayed a knowledge or intuition, which to say the least, was extraordinary. Looking up to the brassy sky, and then away to the distant horizon, and then at the parched ground, he would fall into a deep reverie, which would last for a few moments, at the end of which he would start off at a rapid gallop toward some invisible point, and the end of that ride was——water.

When questioned as to the manner by which he acquired this remarkable skill, the trapper never gave a satisfactory answer. He sometimes said it must be that he scented the water; but, as it is well known that this element has no smell, taste or color, although the presence of vegetation, which it causes, and which is nearly always a sign of it, frequently gives out a strong odor, which guides the thirsty animal from a long distance, yet it cannot be supposed for an instant that the hunter acquired his wonderful knowledge in this manner. No human olfactories have ever been known to hold a hundredth part of the delicacy necessary for such an exploit. Ward always smiled rather significantly when he gave such an answer.

It might be that he was really ignorant of the means by which he possessed such a superiority over his fellow creatures in this respect, and which made them only too glad to follow him to any point he indicated, without fear of consequences; or it may be that he had acquired some subtle secret of the “hidden 17 springs” of nature—some knowledge of her means of working—so hidden from human knowledge that they can be reached by no process of reasoning, and are only discovered (which is rarely the case,) by accident.

Such a knowledge, or “gift,” as it is properly termed, is frequently found among the North American Indians—a people whose inability to grasp the simplest truths of art or science, is too well known to need reference here. Some withered old Medicine man, or wrinkled old woman, with her crooning and sorcery, is frequently the depository of a secret in medicines,—of the subtle working in certain forms of disease, of some apparently harmless plant, which when made known to the prying eyes of his pale faced brother, has made his fame and reputation and has given him a name for learning and skill, that has made him the enemy of the whole profession.

How many of the colossal fortunes of the present day have been builded upon the knowledge of some Medicine Man, or some negro woman who has gained a well founded reputation among the ignorant people.

So we say Ward Lancaster may have stumbled upon some secret of nature’s workings, which the jealous dame had carefully veiled from other eyes; and in the presence of this knowledge he never went astray.

The hunter was full of adventures, and could recount his experience by the hour as he sat smoking around the camp fire, at the end of the chase, or at the close of the day’s tramp. He had acted as guide to several expeditions which had crossed the Rocky Mountains into California and Oregon; and, at the present time, he and Harling were looking for a caravan or large emigrant party, which they had been sent from Santa Fe to intercept and guide into Lower California.

Having thus introduced somewhat at length our friends to our readers, we come to speak more particularly 18 of their first meeting. They soon explained each other’s name and destination to each other, when Ward seemed disposed to question Wainwright still further. He thought he saw about the young man signs indicating that he had followed this hunting and trapping business but a comparatively short time. His well shaped hands, had not the brown, hardy character which characterized those of his companions, and the jetty luxuriant beard failed to conceal the rosy-tinted skin, which could never have been retained under the storm and tempest of the prairie.

Wainwright, however, skilfully parried the questions when they came too close, or refused to answer them altogether.

“I belong further east,” said he, “but there are some things which I don’t choose to tell at present. The time may come when I shall be glad to do so, but it hasn’t come yet.”

“All right; that yer is what I call a hint to keep my mouth shet. Howsomever, you’ll allow me to ask another question or two.”

“Certainly, you may ask all you please,” replied the young hunter, with a significant intonation.

“How long have you been on the prairies, and among the mountains?”

“A little over a year.”

“Been with one party of hunters all the time?”

“No; with half a dozen, and once with a party of Indians.”

“Have you learned any thing of the ways of the mountains and prairies in that time?”

“As I expect to be associated with you for some time, I will waive that question for a few months, and then allow you to answer it for yourself.”

“That’s sensible,” grunted Harling, “I’ve only one more question to ax.”

“I am ready to hear it.”

“What brought you out here? A quarrel, love adventure, or what?”

“If any one asks you such a question tell him you are unable to answer it.”

This was a decided reply, and the trapper so accepted it. They had conversed together in low tones, occasionally pausing and listening for any sound of their enemies, but they heard none—nothing breaking the stillness but the solemn flow of the dark river.

“I think,” said Harling, “we had better move our quarters, for these sneaking Comanches can smell a white man, about as far as you can smell water.”

“Yes, what I was a thinkin’ on,” muttered his companion, “Mo when-your-right, or Wainwright, you’ll foller.”

The three began stealing along the bank of the river, frequently pausing and listening, but as yet, hearing nothing suspicious. The sky had cleared somewhat during the last hour, and the clouds which had overspread it after the sun went down, and a number of stars were visible. Still it was very gloomy, the party being barely able to discern a few feet in front of them, as they advanced so stealthily upon their way.

Ward took the lead, his form being faintly visible, as he carefully picked his way, while behind him came Harling, and our hero, the young hunter, brought up the rear. The latter had heard them speak of their horses, and knew of course that they must be the owners of animals, which were so indispensable in this desolate country; but he wondered where they were kept, as he failed to see anything of them.

“However, I shall learn all in due time,” was his conclusion, as they walked leisurely along.

They had progressed in this manner perhaps for a third of a mile, when the leader hastily scrambled up the bank the others following, found themselves on the edge of the prairie, which had witnessed the exciting chase between the Comanches and the young hunter, a few hours before.

By this time the sky had cleared and objects could be seen quite distinctly, for a considerable distance. The three men halted and looked out upon the prairie, but saw nothing but darkness.

“Where are your horses!” inquired Wainwright.

“About a mile from here.”

“Aint you afraid of losing them!”

“Not much; they’re lied where it would take a pair of sharp eyes to find them.”

“But those Comanches——”

“Sh!” interrupted the trapper, “I hear something walking.”

They listened, and the faintest sounds of footfalls could be heard, quite hesitatingly, as if some one were very cautiously approaching them.

“Down!” whispered Ward, sinking silently to the earth, “whoever it is is coming this way.”

The others were not slow in imitating his example, and lying thus upon the ground intently listening, they now and then caught a dull sound, as if made by an Indian carrying a heavy body, with which he retreated, as often as he advanced. A person who had had no experience of prairie life would have failed to hear the sound at all; but all three of our friends heard it distinctly.

Ward Lancaster had detected the direction of the sound, and was peering out on the prairie in the hope of discerning the cause of it. All at once he gave utterance to a suppressed exclamation, and then added, as he turned his head.

“What do you s’pose it is?”

“I am sure I cannot tell,” replied Wainwright.

“It’s a horse, and if I’m not powerful mistaken it’s your own animal; but hold on; don’t rise; it may be a trick of the Comanches to find out where you are.”

The horse steadily advanced until a few feet of the prostrate men, when it pawed and snuffed the air Ward then quietly arose, and before the animal could 21 wheel about, he seized the bridle and held it a prisoner. Wainwright then came up and found that it was his own mustang, with all his accoutrements complete.

“How fortunate!” he exclaimed in pleased surprise, as he examined the saddle and bridle; “every thing seems to be here.”

So it proved, and Wainwright lost no time in putting himself astride of his mustang. Following the direction of his friends, they soon reached a small clump of stunted trees and undergrowth, where the trappers’ horses were found. It was at first proposed that they should encamp here for the night, but, as the Comanches were unquestionably in the vicinity, they concluded to get as far away as possible. So they mounted their animals, and under the leadership of Ward took the river for their guide, and rode at a moderate walk until daylight, by which time they had placed many a long mile between themselves and their dusky enemies.

The hunters scrutinized every suspicious point and took a careful survey of the surrounding prairie and hills, but discovered nothing suspicious, and they concluded that there was nothing further to fear from these wild riders of the plains.

The range of hills was still in sight, and offered a secure hiding place for any of their enemies who chose to conceal themselves there, but if such were the case, the trappers were confident they could detect them, and failing in this they believed themselves justified in coming to the conclusion mentioned.

Ward took his bearings and headed towards a point where he hoped to intercept the emigrant train; but when night came they had not yet reached it, and they encamped in a small grove. Wainwright had brought down an antelope with his rifle, at such a distance as to extort a compliment from the hunters, and thus bountifully provided for supper, they counted upon a pleasant evening.

“Come, George, isn’t that steak done yet?” inquired the impatient Lancaster. “It strikes me that it has just got the color to insure a good taste. What do you think Fred?”

“I’m hungry enough to make anything taste good to me, stewed, fried or raw.”

“Now just keep easy,” replied Harling. “When the meat is ready you shall have it—not before—no matter how hungry you are.”

“Woofh!” exclaimed Lancaster, “if I get much hungrier, I’ll eat the meat up and take you by way of dessert. So hurry up, will you?”

Not the least attention did the imperturbable cook pay to the murmurings of those around. He turned the meat around as slowly and carefully as ever, and when it had reached the point when Lancaster declared it was “spoiled” he removed it from its perches, served it into three equal slices, and announced that it was ready.

So it proved—rich, steamy, juicy and tender, so that it fairly melted in their mouths. No sooner did it touch their palates, than they inwardly thanked the cook for resisting their importunities, and furnishing them with such a choice morsel. They thanked him inwardly, we say, but, as might be expected, each took particular good care to say nothing about it.

But Harling saw his advantage and followed it up.

“You’re a couple of purty pups, aint you? Don’t 23 know what’s best for you. If it wasn’t for me, you’d both starve to death.”

“Get out!” replied Lancaster, “let other people brag up your cooking; don’t do it yourself.”

“There’s no one in this crowd got gratitude to thank me after I’ve crammed their mouths for them.”

“Then I wouldn’t do it myself,” laughed Fred Wainwright.

“Yes, I shall too, for it deserves it, and it’s time you learned to say so.”

“Hang it,” cried Lancaster, pretending to have great difficulty in tearing the meat asunder; “if this piece hadn’t been cooked so long, it would be fit for a white man to eat, but as it is, it is enough to tear my teeth out.”

“’Cause you’re making such a pig of yourself. Try and eat like a civilized being, and you’ll find it tender enough for an infant.”

“How do you find it Fred?” turning toward their younger companion.

“I can manage to worry down a little.”

“I should think you could!” was the indignant comment of the cook, as his friends swallowed the last mouthful.

The darkness slowly settled over prairie and mountain, and when the hunters had gorged themselves with meat, so rich and juicy that they could not conceal their delight, they wiped their greasy fingers upon their heads, produced their pipes, lay back and “enjoyed themselves.”

Although in the midst of a hostile country, all three were too experienced to feel any apprehension regarding their safety. This fire had been so skilfully kindled at the bottom of a hollow, so artfully, that a lynx-eyed Apache or Comanche might have stood within a hundred feet of them without suspecting its existence. Their horses, too, had been trained long enough in danger and peril to know the value of silence on a dark night and in a still country; and there 24 was no fear of their discovery by hostile eyes through any indiscretion on their part.

From long exposure to danger, the hunters had acquired a habit of speaking in low tones, and frequently pausing and listening before making responses to a question. When they laughed, no matter how heartily, it was without noise, except out upon the broad prairie, when their cramped up lungs demanded freedom, and then their laugh rang out clear and loud, like the blast of a silver trumpet.

Even as they smoked, the coal in their pipes was invisible. They had a fashion unknown to us of more civilized regions, of sinking the coal or burning part of the pipe below the surface of the tobacco, by a few extra long whiffs, so that, as they leisurely drew upon them afterwards there was no fear of the red points betraying their presence, a thing which has more than once taken place in the early history of our country.

The party drew at their pipes in quiet enjoyment for some time, and then, as the night was pleasant and warm they fell into an easy conversation.

“I wonder whether we shall come upon the caravan tomorrow,” remarked Fred Wainwright, not because he imagined there was any thing particularly brilliant in the remark, but for the same reason that we frequently say a pointless thing—because we can’t think of something better.

“P’raps we shall, and p’raps we shant,” was the non-committal answer of Ward Lancaster.

“You are right for once,” said Harling. “No matter whether we see ’em or not there isn’t much danger of you prophesying wrong.

“But I really think we are somewhere in their vicinity and we shall see something of them tomorrow—some sign at least that will give us an idea of their whereabouts.”

“Are you sure this emigrant train is where it can be found?” asked Fred Wainwright.

“Yes, sir. I said that; I understand it, which is a blamed sight more than either of you two lunkheads could do. The fellow was in earnest about it. Didn’t you see Harling how quick the feller came straight at me, and talked to me like a man whose life depended on his getting my service.”

“Did he go far enough to offer a price?” inquired Harling, rather quizzically.

“Yes, sir,” was the triumphant reply. “He hauled out several yellow boys, and wanted to put them in my hands to seal the bargain.”

“You took ’em, of course?” remarked Fred in a serious tone, but taking advantage of the darkness to grin to an alarming extent.

“No SIR!” was the indignant response. “I told ’em I took money after I’d done a thing—not before. He seemed quite anxious and urged me to take it saying it was a-ahem-a-rainen-strainer.”

“Retainer,” accented Fred.

“Yes; something like that; don’t know what it means, but I told him I did not do business in that way. I axed him all about the company and learned all I wanted, and then told him when it reached ‘Old Man’s Point,’ I’d be thar!”

“How near are we to it?”

“About ten miles off; we’ll ride there before breakfast tomorrow, and take our first meal with the party.”

“What became of their guide?”

“The guide was shot by an Apache Indian two days ago, and the party have been half frightened to death ever since. They declared, if they could not find a guide, they would never enter California; as you can see we’ve good reason to ’spect they’ll be rather glad to have our company.”

“It seems singular that the very man upon whom they relied, and the one who no doubt knew more about the Indians than all the others combined, should be the very first one to fall a victim.”

“How do you know he was the first one?” demanded Ward Lancaster, almost fiercely, as he turned his face toward Fred Wainwright.

“I don’t know it; only imagined it from the remark you made.”

“Well, perhaps he was the first one,” was the complacent remark of the hunter, as he resumed his pipe. “I don’t know neither to the contrary notwithstanding.”

“Then it’s my opinion you’d better keep your mouth shet,” was the comment of Harling. “Them people that don’t know nothing, gain the most credit by saying nothing.”

“That’s the reason you keep mum so much of the time, I ’spose. Wal, that’s right; you ought to know yourself; don’t let me change your habits, because that is a mighty good habit you’ve got.”

“It strikes me it would be a good habit for us all to follow at this time,” suggested Fred Wainwright. “It is getting late, and I feel like going to sleep.”

“Go ahead then,” said Ward.

But the hour was growing late, and shortly after the three hunters were wrapped in profound slumber.

The gray dawn of early morning was just beginning to break over the prairie when the “Trappers of the Gila” were active. Such men are invariably early risers, unless they have been deprived of several night’s rest, and desire to make it entirely up at one stretch.

Harling’s culinary skill had given him the position of caterer to the company’s appetite, and from what has been mentioned in the preceding chapter, there will be but little doubt but that he had succeeded admirably.

The time to which we refer being quite modern, the party always went provided with lucifer matches, instead of resorting to the use of the tedious flint and tender. Of course they were easily carried in such a manner as to be impervious to damp, and to be reliable at all times.

Abundant fuel was close at hand, and not five minutes intervened after their rising, when a bright fire was crackling and snapping, and the cook had another goodly-sized piece of antelope steaming and sizzling, giving out an odor enough to drive a hungry man distracted. A clear icy cold stream a hundred yards away, afforded them the means of performing their morning ablutions.

The breakfast was hastily swallowed, and just as the first beams of the morning sun came up the eastern horizon, the three hunters, mounted on their animals, 28 were galloping over the prairie, toward Old Man’s Point, quite a noted place, which could be distinguished on the plains for a distance of twenty miles.

At the very moment of starting, Lancaster looked to the north, where a dark point, apparently the size of a man’s body could be distinguished. This he announced was the point of rendezvous, so well known to parties crossing the plain and passing into Lower California. As it was in plain sight, all the party had to do was to ride straight toward it.

The hunters were galloping in this leisurely manner, when Fred Wainwright suddenly exclaimed with no little excitement,

“Yonder come the emigrants this very minute.”

As he spoke he pointed away to the east, where in the distance could be seen a cloud of smoke, as if made by the trampling of animals. Nothing else could be distinguished, but a moment’s glance sufficed to show unmistakably that it was not natural clouds, such as an inexperienced eye would pronounce it, but it was the fine dry powder of the parched prairie raised by the passage of multitudinous feet.

From the distance and through the haze nothing at all could be discovered of those who were “kicking up the dust.” The fact that it was very near that quarter from which they expected the coming of the emigrant party, and that it was at the very time they were looking for their coming, argued strongly for their being their friends. But neither Harling nor Lancaster were quite satisfied on this point.

Reining their horses down to a slow walk, they gazed long and fixedly in the direction of the tumult, and finally the sharp-scented trapper exclaimed:

“They ain’t white men; they’re Injins!”

“How do you know that?” inquired Fred.

“I can smell ’em!”

This, however, was an attempt to be facetious, and the hunter condescended to give his reasons for holding such strong suspicions.

“You see there is too much dust, in the first place, for a party of white folks.”

“You know the prairie looks as if it hadn’t rained for six months, and we have left a trail behind us, something like a Mississippi steamer leaves, when she throws every thing she has on board into her furnaces, for the sake of beating her rival. Just look behind you and see what a cloud you have left in the air.”

“Yes; I know,” returned Lancaster, without turning his head. “And that’s just the reason for them ’ere thieves off yonder being redskins. We’ve had our horses in a gallop, and their hoofs have kicked up this dust, an’ that’s just what has been done over yonder. You have heard, I suppose, that emigrant parties aint apt to go ’cross the plains on a full canter, you’ve larn’t that I ’spose, haint you?”

“I’ve learnt it now if I didn’t know it before,” laughed Fred. “You know there may rise occasions for them to put themselves at their highest speed, as when a party of Indians come screaming down upon them.”

Lancaster shook his head.

“You’re mistook there, my friend; you’re mistook there. I’ve guided many a party through the Rockies and across the plains, and some of ’em from St. Louis and Independence, and I never yet seed that thing done. ’Cause why, it would be all tom-foolery, with their loaded wagons, and jaded horses and sleepy oxen; such a thing would be impossible—yes, sir, impossible, even if all the Injins were on foot. You see, don’t you?”

Wainwright could not deny the force of what the hunter said, and much against his will he was led to believe that a party of hostile Indians were rapidly nearing them. This, while it gave the hunter no uneasiness as regarded themselves, looked as though the emigrant train had gotten into trouble, and on that account the three horsemen were more apprehensive 30 than they would have been under ordinary circumstances.

In the mean time the agents in this cloud of dust were rapidly nearing the party of hunters, who, with their horses upon a slow walk, were attentively watching for some further evidence of the identity of their enemies.

“Hark!” admonished Harling, raising his hand with a gesture of silence.

All bent their heads and listened. Faintly through the turmoil and confusion, they caught the sound of shouting, as though the parties were calling to each other; at the same time a faint rumble or trembling was heard which showed that numerous animals were tramping the prairie.

“Doesn’t it look as though the emigrants were in trouble?” asked Fred, with an expression of familiar alarm. “I do hope they haven’t been attacked.”

“It is a party of Injins driving a lot of animals,” said Harling. “They have stampeded them, and if you listen very hard you can hear the tramp of their feet.”

“But the shouting?”

“All as matter of course. They have got the animals on a full run, and are shouting and yelling at them to keep them going. Hark! How much plainer you can hear ’em?”

Such was the case; the fearful whooping of the excited redskins coming to their ears with great distinctness. Suddenly Lancaster’s face brightened.

“I understand now what it all means. A lot of thieves have stampeded a drove of sheep and have ’em on the full run so as to get them as far away from re-capture as soon as possible.”

“They must be Apaches, then,” remarked Fred.

“No, sir,” and the hunter pressing his lips, “them’s Comanches.”

“What are they doing as far up as this?”

Lancaster looked at the interlocutor in surprise, and then repeated.

“As far up as this! Ten years ago I seed a party of over twenty Comanches along the Yellowstone, a thousand miles from here, and I’ve seen hundreds of ’em ’atween here and there.”

“I thought they rarely came so far north. I have never seen any of them till yesterday.”

The hunter laughed as he answered.

“There’s no need of your taking the trouble to tell us that; I never ’sposed you have. True, the most of ’em sticks down in New Mexico, Texas and around there, but they often come further north, just to get a chance to stretch their limbs.”

“But how can you tell them from the Apaches who resemble them so closely?”

“That is rather a nice point, I’ll own,” said Lancaster, “with some professional points, but the fact is, that since we’ve been sitting on our horses, riding and listening, I’ve heard a scream given by one of the dogs, that I’ve heard afore and that always came from the throat of a full blooded Comanche.”

“It strikes me that if such is the case, the best thing we can do is to get out of this region as rapidly as possible.”

This was really the most sensible remark Fred Wainwright had made for some time; and feeling it to be such, he was not a little confused to see that it attracted scarcely any attention. Finally, Lancaster, who was still looking toward the tumultuous crowd which was passing toward them, remarked,

“They’re going to pass to the north of us, between us and the Point.”

“But they’ll see us.”

“What if they do?”

“Why we shall have a chase and all for nothing too, and be kept away the whole day from joining the party who are looking as anxiously for us.”

“See here, youngster,” said the trapper, turning toward 32 their younger companion. “You’re talking about something that you don’t know nothing about. These Comanches are stealing them sheep, and they want to get along with them as fast as they can, if not faster; they have got no time to stop and fight, no matter how bad they want to.”

“You’ve guessed right, for once in your life,” remarked Harling, “you can see that the drove have turned to the north, and when they pass us there will be a good half mile between the Comanches and us.”

Lancaster looked inexpressible things and kept silence.

The remark of the hunter, or rather his prediction came true. In a few minutes, through the dust and smoke, they could distinguish the forms of Indians mounted on their mustangs, dashing hither and thither in the most rapid evolutions, while the affrighted sheep huddled together, or piled pell mell in their frantic attempts to make faster time. The Comanches displayed the most extraordinary skill in horsemanship, darting hither and thither, sometimes under their horse’s belly, then over his neck, and in every conceivable position.

The Indians discovered the hunters at the same instant that the latter saw them; but they did not give them the least heed. They were too numerous to fear any thing from the white men, and they knew they had too much shrewdness to disturb them; and so the mortal enemies passed within a comparatively slight distance of each other, with no other evidence of recognition than a mutual scowl of hate.

The hunters waited until a portion of the thick dust had settled, when they resumed their march for the point where they expected to meet the approaching emigrant party.

The dust raised by the multitudinous drove of sheep was so dense, as almost to suffocate the trappers as they rode along, even when they waited till the yelling, gyrating Comanches were far in the west with their terror-stricken animals.

A thin coating of the powder settled upon their garments, so that when they emerged with the free air beyond, they were all of a yellowish white color; but a vigorous brushing and shaking of their clothes speedily resumed this, and they became themselves again.

A half hour later, the party reached the “Old Man’s Point,” but as they swept the horizon, saw nothing of the approaching emigrant train. The rocks themselves were a mass of irregular boulders piled above each other to the distance of fully a hundred feet, while the base covered an area of fully a quarter of an acre, so that no better spot could be selected as a rendezvous, or from which to take observations.

“Fred, go to the top and take a look!” said Lancaster, “I expect they must be in sight.”

“I was just thinking of doing so,” was the reply of Wainwright, as he dismounted and began clambering up the rocks. His agility soon carried him to the top, and shading his eyes with his hands, he looked off toward the east a moment, and then called out,

“They are coming!”

“Make right sure,” called Lancaster back to him, 34 “for you are powerful apt to make blunders in this part of the world. Be you sure they ain’t Comanches or Apaches or some other party of stragglers.”

“I can see the white tops of their wagons.”

“I guess you’re right then,” was the comment of both the hunters below, as they considered that this fact established the other truth.

Turning their heads in the direction indicated they were able to discern the caravan, at that great distance, apparently standing still, but, as they knew, moving as rapidly as possible toward them.

Having assured himself that it was all right regarding them Fred Wainwright turned his gaze toward the vanishing Comanches and their stolen sheep. There was no difficulty in locating them, as the vast volume of dust indicated their whereabouts as unmistakably as does the smoke the track of a fire on the prairie.

The young hunter observed something which struck him as rather remarkable. The Comanches, after reaching a point, when it was plain they could not be discerned by any one, standing at the base of the Rock, made a bend fully at right angles to the course they had been pursuing. This they continued, until they grew faint and finally vanished from sight altogether.

This rather puzzled Fred until he mentioned it to the two hunters below when he descended, when Harling explained its meanings. From whomsoever the Comanches had stolen the sheep, it was evident they had fears of pursuit. It is the easiest thing in the world to follow a sheep trail over the prairie; but, if the pursuing party should ever happen, for the sake of convenience, to leave the trail, they would be very apt to take a general direction in their pursuit, without going to the trouble of keeping to the main path. In this manner, unless some such ruse were suspected, they would never notice the change in direction made by the thieves, and thus give the latter just what they 35 wanted, sufficient time to get themselves and their prizes into safety.

But the emigrant party was now close at hand, and Fred reascended the rocks and waived his hat as a signal that all was right. This demonstration relieved them in a great degree, for upon discerning the figures, the company had come to a dead halt, and seemed to be consulting together; but now they immediately moved forward; and as the trappers moved out to meet them, the two parties speedily mingled with each other.

The emigrants numbered about a hundred,—ten wives, a young woman, a half dozen children, while the rest were strong, stout bearded men, well-armed, and willing to dare anything in the defence of their property. They had got pretty well used to Indians, storms and danger in coming thus far, and felt considerable confidence in themselves.

“But we’ve never traveled this way before,” remarked Mr. Bonfield, a pleasant, middle aged man, who by virtue of having the largest family, and owning almost all the horses and wagons, was looked upon as a sort of leader in the enterprise; “and, of course we ain’t acquainted with the route. We engaged a capital guide at St. Louis, but several days ago he was shot.”

“He oughter known better than that,” remarked Lancaster; “if he learned enough to be a guide, he oughter learned enough to take care of himself.”

“He did; but this was one of those things which sometimes happens when we don’t dream there is any danger. He and Templeton here were chasing an antelope, just at sunset, when they struck him, and he limped a short distance, and finally tumbled over in a small grove not a half mile distant from camp. Of course they dashed after him, when, just as they went down into the timber, I saw a flash from behind one of the trees, the poor fellow threw up his arms, rolled off his horse and fell dead to the ground. Templeton 36 dashed on into the grove, when a single Apache warrior on foot, started on a run across the prairie, but he hadn’t taken a dozen leaps, jumping from side to side, so as to distract his aim, when he put a ball through his skull and laid him dead in his track. I suppose, when the Apache saw them coming, he knew it meant sure death to him, and as he did the best he could—shot one and run for it; but who of us, if we had been in the guide’s place would not have done precisely as he did?”

“You’re right,” replied Harling. “What was his name?”

“Hackle.”

“Joe Hackle?” asked Lancaster, with considerable interest.

“That was it.”

“Poor Joe; he and I trapped together for three years on the upper forks of the Platte, and a braver or better fellow never lived. He knowed every mile of ground between the Mississippi—that is if you follow the route travelers generally take.”

“And that reminds me that we were told that we should find Mr. Ward Lancaster, and George Harling at this place, and that they would act as our guide into Lower California. I presume you are the gentlemen?”

“Well, yas,” replied Lancaster with a huge grin, “I s’pose we be: that is I’m Ward Lancaster without the Mr.”

Mr. Bonfield laughed; for he evidently understood what it all meant. The emigrant be it remembered had halted, and the leader and several of the men had advanced a hundred yards or so, and were consulting with the hunters. The rest of the emigrants were busy attending to their animals, or to themselves and their private affairs.

“Can we engage you as guides?” asked the leader, unable to conceal his eagerness.

“I rather think so, as we come out here for that thing.”

“There’ll be no difficulty about the compensation; for we need a guide badly enough. Most of my party had concluded to halt here and wait until we could procure one; and, although I opposed this conclusion, I should have disliked very much to have penetrated further into this country, which is entirely unknown to every one of us.”

“It wouldn’t have done,” said Wainwright. “You would have lost your way among the mountains and every one of you would have been picked off by the Indians before a week had passed over your heads.”

“So I thought; or else taken prisoners.”

“Those Indians in these parts, ain’t apt to take prisoners, unless they are in the form of valuable animals, or fair women.”

“He is right,” said Lancaster, deeming it necessary that the statement should receive his endorsement before he could pass for genuine in such a promiscuous company.

Mr. Bonfield and Lancaster now went apart by themselves for a few moments, and talked together in low tones. They soon rejoined the others when the trapper announced that the arrangements were completed, and they were to accompany the party to their destination, which was Fort Mifflin, on the western side of the Coast Range, or Rocky Mountains, in the midst of a gold region. At the little town which encompassed this fort, were a dozen of their friends, who had been there a couple of years, and who had sent for them. They had a young lady, whose father was the principal man at Fort Mifflin, and who had sent for his daughter to join him, at the time the party crossed the plains.

The preliminaries being settled, the party rode back to the emigrant train, made the acquaintance of the others and the march was resumed. They had all breakfasted, and it was concluded to make no halt 38 until they reached a small stream, which Lancaster hoped could be found by noon, when they could rest as long as they chose.

“What part of the States are you from?” inquired Fred Wainwright, of the gentleman who had been referred to by the leader as Mr. Templeton.

“Missouri,” was the reply.

“Ah! what part of it?”

“From the capital.”

The young hunter could not avoid an exclamation of surprise, uttered so naturally that the emigrant turned abruptly toward him.

“Are you from there?”

“I—ahem!—I know several persons from that part of the country—that is I used to know them, but it is a good while ago.”

Mr. Templeton gazed at him sharply, and remarked by way of explanation of his apparent rudeness:

“Most of us are from there, and I thought at first there was something in your voice that was familiar, but I don’t remember your name. We have a young lady—Miss Florence Brandon, whose name you may have heard, as she was a belle at home.”

“I think I have heard of her.”

“Would you like to renew your acquaintance with her?”

“No; I thank you; we hunters are hardly in a condition to appear in the presence of refined ladies, as I judge Miss Brandon to be, and our lives are such that we should cut a sorry figure, if we attempted to do so.”

“But you talk like one who has not always led a hunter’s life.”

“I have some education, but at present, I am simply a hunter and trapper.”

Florence Brandon! Little did Mr. Templeton dream of the strange emotions awakened in the breast of Fred Wainwright, the young hunter, at the mention of that name.

The sun had barely crossed the meridian, when the emigrant party reached a small stream of water, and made midday halt. The animals were fed, dinner cooked and eaten, pipes smoked, and everything done in accordance with the time and circumstance.

Fred Wainwright did his best to appear natural, but since the mention of Florence Brandon’s name, his heart had been stirred, as it had not been stirred for many a day. Old emotions which he imagined were dead had——but enough for the present.

When the call was made for dinner, he saw a young lady descend from one of the large baggage wagons, so remarkably handsome, as to cause an exclamation of surprise and admiration from all who had not seen her. The young hunter started and gasped, and then passed his hand over his face, as if to make sure that his massive beard was there, then he slouched his hat so as to be sure the fair girl could not possibly recognize him.

At meal-time, he managed to keep a goodly distance from her; and, when pressed to go forward and make himself known, he resolutely refused, and acted very much as though he had a mortal terror of Miss Florence Brandon.

The alloted time for rest had expired, and the party were making ready to move on again, when three strangers made their appearance mounted on rather sorry looking nags. Two of them were dressed in half 40 civilized costume, with shaggy, untrimmed beards and hair, and a remarkable talent for saying nothing except when directly appealed to. The third would have attracted attention in any part of the world,—being nothing more nor less than a genuine, traveling Yankee, dressed in precisely the same suit of clothes in which he left his own native Connecticut a year before. A huge, conical hat surmounted a small head, from which sprouted a mass of yellow hair, a portion of which protruded through an opening in the top, while the rest hung down over his shoulders. Sharp, grey eager eyes, a thin peaked nose, a yellow tuft of hair on the chin, prominent cheek bones and bony, angular muscular frame, completed the noticeable points in the most talkative character in the group.

While the party were as yet nearly a hundred yards distant, the Yankee called out,

“Say, you folks, have you seen anything of any stray sheep in these parts?”

The earnest simplicity with which this question was asked brought a broad smile to the face of all who heard it. Lancaster asked as the three horsemen rode up,

“Have you lost any?”

“Ye—s! a few.”

“How many?”

“Five thousand, four hundred and twenty eight.”

From the remark of the horseman, it was evident that the flock of sheep stolen by the Comanches belonged to him and his party. Lancaster, therefore had no hesitation in replying,

“We seed a drove of almost that size go ’long this morning.”

“Did you count ’em?”

“I rather think not.”

“Pretty good sized drove?”

“Right smart size.”

“Who was driving on them!”

“A half dozen Comanches.”

“There’s our sheep!” exclaimed the horseman clapping his knee and turning his face toward his companions, who merely looked their reply without speaking.

“Now, ain’t that mean!” he asked, turning back again toward the trappers and emigrants. “My name is Leonidas Swipes, and me and these two gentlemen left New Haven, a year ago last April. All three of us teached school in districts that joined, but we concluded we was intended for better business, and so we put our heads and purses together and started for California.”

“What were you doing with such a number of sheep!” asked Mr. Bonfield.

“Taking ’em into California where mutton is five times as high as it is east.”

“But where did you get the sheep!”

“Wal, the way on it was this,” replied Mr. Swipes, ejecting a mouthful of tobacco juice, rolling his quid to the opposite cheek, and assuming a position of ease. “We started from St. Louis just at the beginning of Spring, lost our way and afore we knowed it fetched up in Santa Fe, five hundred miles off our course. Of course, we were considerably riled to think we had made such fools of ourselves, but there was no help for it, and we soon found there was as good chance to make money in Santa Fe, as in any other part of the world.”

“Yes,” said Harling, “it is one of the greatest gambling holes this side of the Mississippi.”

Mr. Swipes instantly straightened himself with righteous indignation.

“You don’t s’pose we ever gamble? No, sir; such things are frowned upon in Connecticut, and there aint one of this party that can tell one keerd from another. No, sir; we never gambled in our lives. If you aint mistaken there, then my name aint Leonidas Swipes,—no, sir; by jingo.”

“But how did you get the sheep?” pursued Mr. 42 Bonfield, for there was something in the rattling loquacity of the Yankee that made him interesting and that caused the male members of the party to gather around him. As the horseman found himself in this pleasing position, he grew more voluble than ever, and declaimed in a style and manner, which demonstrated that while his two companions were mum, yet his party in the aggregate did enough talking to answer very well for one of its size.

“I’m saying it was rather queer, the way we come in possession of them sheep, I swan if it wasn’t. We hadn’t been in Santa Fe a great while, when a sickly looking Missourian and a gander legged Arkansian came into the town with this drove of sheep. They tried to sell ’em, but nobody would give their price, and one of ’em got out of patience, and turned his horse’s head around and started straight back for home. The other staid at the hotel where we was, and got took sick, and I soon seen he was going to die. As I’ve read law some, I axed him whether he hadn’t a will to make, and I’d be happy to draw it up for him. He said he hadn’t a single friend in the world, except the Arkansian, and he didn’t s’pose he’d ever see him again. He said he hadn’t any property except the sheep.

“Well, friends, I was not long in seeing there was a fine opening for a young man, and the way I stuck to that poor Missourian would have teached your hospital nurses a lesson. I hope you don’t think there was any selfishness in it; for if any of you get sick, I’ll do the same for you. Howsomever, that aint here nor there; the fellow died after awhile, and, in his will, it was found that the five thousand and odd sheep had been left to Leonidas Swipes.

“I was about to sell the drove to a couple of Mexicans, when I happened to hear that sheep in California was worth twenty dollars a piece. Jingo! wasn’t there a chance? That flock that I wast just on the point of selling was worth over a hundred thousand 43 dollars, if I could only get it through the mountains. I tell you the bare idea gives me the head-ache, I swan if I didn’t.

“Wal, I told my friends here, Mr. Doolittle and Birchem that if they’d join, each of ’em could have a third, and we’d make our fortune. So we started, and here we are without a sheep to our name.”

“How did you expect to get through the mountains?”

“The thing has been done before and can be done again.”

“But you did not know the way.”

“Oh! we had a guide, but he played us a mean trick. I agreed to give him a hundred sheep for his payment, just as soon as he got us into the Sacramento Valley. We hadn’t been out three days, when one night, he give us the slip, taking two or three hundred sheep with him and leaving us to go alone. We felt a little shaky about doing it, but we couldn’t do anything else, and so we shoved ahead, and by jingo here you see us, only three sheep of us,” and Mr. Swipes’ face expanded into a broad smile.

“But you haven’t told us how these Comanches got the sheep away from you?” said Fred Wainwright, echoing the curiosity that all the others felt.

“You wish the modus operandi I presume, I can soon give it, I swan if I can’t. Last night we stopped on a small stream of water, where we knew the grass was so succulent,—so succulent, that the sheep would stay there all Summer if we’d only let them; and, as we was pretty tired, and hadn’t had a good night’s sleep since leaving Santa Fe, we made up our minds to take a square night’s sleep.

“Well, we did so; and when I awoke this morning, I looked around and seen our sheep about a half mile distant, tearing away like mad, and a party of Indians driving on ’em. Well, if you ever seen three Yankees, you know what the matter was with us. We hopped around there awhile, like a lot of chickens that had 44 stepped on a hot johny cake, and then we set off after the Indians, shouting to ’em to hold on, while we explained the matter to them; but hang ’em, they only went the harder; and, as our horses was used up, we had to give it up and yumer ’em along like to keep ’em from giving out.”

“You have been rather unfortunate,” remarked several, feeling really sorry for the unfortunate Yankees.

“Yes, but I hope we can recover ’em agin.”

“How?”

“Can’t we make a party and pursue them? I’ll do the fair thing with any of you that will join us. You see it hardly looks smart to let a hundred thousand dollars stray off in that style.”

“I cannot speak for the three hunters here, but it would be hardly prudent for the rest of us to weaken our force by dividing it when we are in such a dangerous portion of the country,—but, I beg pardon, we have forgotten the laws of hospitality. Have you been to dinner?”

“I was about to observe that we had not, and we would rather do that just now than anything else we can think of.”

Loss of property, grief and misfortune is almost always sure to affect the appetite. A hearty vigorous digestion is incompatible with depression of spirits, or sudden paralysis of sorrow.

But Leonidas Swipes was subject to no such weakness, so far as the loss of his magnificent drove of sheep was concerned. How remote the prospect of his recovering a tithe of his property, he was resolved that it should interfere in no way with the meal before him.

Himself and his two companions seated themselves upon the ground, near one of the large baggage wagons, while several of the females occupied themselves with placing their food upon a matting before them.

In the caravan were a couple of fine milch cows which, although they had traveled all the way from the States were in good condition and gave excellent milk. When a large pitcher of the cool delightful liquid was placed before the hungry horsemen, their eyes expanded in amazement; but neither Mr. Doolittle nor Mr. Birchem uttered a syllable, except when Swipes asked them whether it was not splendid, whereupon they replied with a grunt and nod of the head.

“Well, I swan if it doesn’t beat all I ever seed or heerd tell on. That’s the first drop of decent milk I’ve tasted since leaving Connecticut,” said he, addressing the elderly woman who was acting the part of a 46 waiter. “We had some in Santa Fe, but it couldn’t begin with this.”

At this point, Swipes poured out a large cup-full, and slowly drank off its contents, gradually lifting the cup until it was inverted over his face thrown back so far as to be horizontal. In this position, he held it for some time until sure the last drop had descended into his mouth, when he lowered it again with a great sigh and a prolonged—“A——hem!”

“But that is splendid now! splendid, by jingo! if it isn’t. When I had that up to my mouth, I just shut my eyes, and there! I was back in Connecticut agin, a sitting under the old mulberry tree, at noon, after we have been mowing hay, and was taking our lunch! Ah! I was a boy again.”

While the hunters were eating, most of the emigrants were consulting together, making the arrangements for the day’s journey, and debating the proposition, the Yankee had made for some of them to join in the pursuit of the thieving Comanches.

Fred Wainwright, feeling somewhat interested in Swipes, sauntered slowly toward him, and took a seat on the ground near the party, while they ate, that he might relieve his depression of spirit somewhat by conversing with the quaint New Englander, who, as has been seen was more disposed to be loquacious than anything else.

“I say Mr.——also Mr.——what did you tell me was your name?” remarked the latter, as he suddenly cast his eyes toward the young hunter.

“Wainwright.”

“I say, Mr. Wainwright, you belong to them trappers; don’t you?”

“Yes.”

“Wal, what do you think of my proposition. Fine chance for a spec,” said he, speaking rapidly and looking shrewdly. “’Taint often you have such a chance.”

“I have no particular feeling about it either way,” replied Wainwright. “It is a big loss for you, but 47 we are bound to this emigrant party, having made an engagement to accompany them through the mountains, and don’t believe Lancaster or Harling will join you without the free consent of this party.”

“Hang the Comanches!” exclaimed Swipes, as well as he could, with his mouth full of meat, bread and milk; “hang ’em I say, they’re up to all kinds of tricks, I understand, but I think they have served us just about the meanest one I ever heerd tell 'on. I swan if they haint. I say, Mr. Wainwright, are you much acquainted with the place over the mountains where you’re going!”

“Never have been there in my life.”

“Don’t say; how in creation then are you going to act as guide; that’s what I should like to know?”

“I am not the guide; it is Lancaster; he has been on the mountains several times.”

“O—ah! I understand; then he could tell me all about the country. Have you ever heard him speak of the place?”

“Oh! yes; he has referred to it many times.”

“Do you know whether there is a good opening for a talented young man?”

“It isn’t likely these emigrants would be traveling there through all this danger, unless there was a prospect of their bettering themselves. But what sort of business do you expect engaging in?”

“Well, anything most; I’m handy at everything; served my time as shoemaker, worked some at tailoring and blacksmithing and on the farm, and teached school in the winter. Say, you now,” exclaimed Swipes, with a sudden gleam of eagerness. “What kind of a place would it be to open a select school?”

The young hunter could not forbear a laugh at the simplicity of the question.

“I don’t think I could give you much encouragement in that direction. The country is most too young to give much attention to their schools, as yet, but I’ve no doubt there will be a fine chance in a short 48 time, for such an institution. I am quite aware there is nothing more beneficial to a new settlement than a church and school.”

“Say Mr. Wainwright,” said Mr. Swipes, looking up in the face of the young hunter, with no little interest. “You look to me and you talk just as if you’ne been a school teacher.”

“No,” laughed Fred, “I never taught school a day in my life.”

“You’ve got larning enough to do so. I swan if you haint! when I hear a man say taught for teached, and beneficial, and all them kind of words, I always set him down as knowing enough to teach school. Perhaps you notice I don’t allers speak grammatically and call my words exactly right; but don’t let that give you the idea that I havn’t got no education. I’m sensible of the mistakes after I make them, and when it’s too late to help ’em——Jingo!”

Leonidas Swipes raised his hands in the most profound amazement, as Florence Brandon suddenly walked around the wagon, came up to where they were sitting, and asked in the most musical of tones, “Is there anything more to which you will be helped?”

The discomfited Yankee for a time was unable to find his tongue. He sat gazing at the picture as one enraptured. His companions now found their tongues, and both replied that they were amply provided and wished for nothing more, whereupon she turned and disappeared.

Poor Fred Wainwright was in a dilemma fully as sore as that of Swipes. He had no thought of the girl until the exclamation of the latter. She halted within a few feet of where he was reclining upon the ground, and when Swipes became confused she turned toward the young hunter, and looked in his face with a smile as if she would like to have him join her in the enjoyment of the scene. But Fred’s face was as red as a Comanche’s when he looked up and encountered those soulful eyes.

Ah! those eyes with their deep heavenly blue! had he not looked into them before? Those red lips! had he not heard the sweetest words of his life come from them? and that queenly head; had he not bent over that! But stay! this will never do.

The minute he felt the eye of the young lady fastened upon him he let his own fall to the ground, and had his life depended on it he could not have raised them again. He could feel that his countenance was burning and fiery red, and his heart was thumping as it never thumped before. Indeed he feared that he should really faint unless he could recover himself.

He was enraged at himself for displaying such an unmanly weakness, and by a strong effort of the will he overcame his emotion—not enough to raise his eyes, to catch a glimpse at the hem of her dress as she flitted from sight again.

“Can it be that she suspected me?” he asked himself where she had gone. “No, I think she would not recognize me in this dress. Then my beard conceals my features, so that when I look into a spring, as I am about to drink, I cannot believe that I am the person I was a year ago. And my cap; I would hardly know my own brother in it. I would not have her know me at this time for the world, and I do hope that her look at me raised no suspicion in her mind.”

“By jingo!” exclaimed Leonidas Swipes, as soon as he could find tongue to express himself, “isn’t she a picter? If I wan’t engaged now, I—ahem! might sail in.”

“So you are engaged?” remarked Wainwright, glad to find an excuse for directing the attention from his own awkwardness.

“Yes,” replied the Yankee, resuming his eating in a serious matter-of-fact matter. “Yes, I’m fast; and if them Comanches hadn’t stolen them sheep, I calculated 50 being in San Francisco in ten months from now, to take passage in the steamer for hum, and to buy Deacon Poplair’s farm and settle down with Araminty—but hangnation, the sheep are gone, and where’s the use of talking?”

And as if to draw his griefs clean out of his remembrance, he ate more ravenously than ever.

But all that is temporal must have an end, and so did the enormous meal of the three half famished sheep dealers. When they had finally gorged themselves, and were remounted on their animals, they by no means were the woebegone-looking wretches that might have been imagined, in those who had just seen a hundred thousand dollars slip and escape off on the prairies. On the contrary they seemed quite cheerful. Messrs. Doolittle and Birchem were silent, as a matter of course, but Leonidas looked greasy and rather jovial.

As soon as the meal was concluded and the march was resumed, the train heading a little toward the north west, as Leonidas remarked they were some distance north of the pass by which they hoped to make their way through the mountains into Lower California, which in reality was Southern California, a considerable ways north of the Gulf, and not the peninsula known by that name.

Leonidas Swipes was informed by the trappers that they truly sympathized with the loss borne by him and his friends, but their engagement with Mr. Bonfield and the leaders of the train forbade them to unite with them in the attempt to secure the sheep. In fact, the trapper informed them that it was useless for them to expect to regain their property. It would require but a short time for the Comanches to reach one of their villages, where they could marshal a hundred warriors with which to defend their property; and mounted on their swift mustangs, it was almost impossible to compete with them.

It was a hard dose to swallow, but Swipes took it 51 philosophically, and persisted in believing there was some hope of recovering them. At least, as the Comanches took the same direction that the train was following, he concluded to remain with the latter for the present.

Until the great Pacific Railroad is completed, traveling across the plains must always be a wearisome labor. The rapid staging between many of the distant points, has in a measure toned down this laborious monotony; but, even with this improvement, hundreds who have made the trip will testify to its wearying sameness.

But, when an emigrant train starts forth it is the very impersonation of monotony to an impatient spirit. For a time the variety of landscape occupies the mind and in a great degree relieves the tedium; but, although some of the finest scenery in the world is in the West, it soon loses its power to amuse, and all feelings are absorbed in those of apprehension regarding dangers and anxiety to get ahead—manifested in some by a figuring and calculation as to the number of suns that must yet rise and set before they can hope to see their destination; in others to hurry and make the best time possible, and in still others by a dogged resolve to plod along without noting the distance traveled, but with the intention of suddenly awaking to the fact that they have completed their journey, and their travels are at an end. The only objection to carrying out this whim, is that he who undertakes it, is sure to find himself in spite of all he can do to divert his mind, looking for the denouement long before it is due.

The emigrant train, which from this time forth 53 must occupy a prominent part in our narrative, was one of those that have plodded patiently all the way from the Mississippi, until now having passed three-fourths of the distance, it was on the very border of the wild regions of California.

On the whole they had experienced good fortune. They had not lost an animal or a member of the party since starting, excepting their guide who was slain in the manner already narrated. Not a man, woman or child had seen an hour’s sickness, and all were now in the best of spirits.

But they had encountered more hardships than they anticipated, and on this day instead of having such a stretch of wild wilderness before them, it was their confident expectation to be at Fort Mifflin. They had terrible times in crossing some of the swift rivers; their horses had been carried away, and many a precious hour had been spent in recovering them; ten of their wagons had been hopelessly mired, and a large portion of their most valuable goods had been whirled away by the rushing torrents.

Then storms, whose fierceness they had never seen equalled in their own home, had swept over the prairie, causing them to tremble for their very lives—but here at last they all were, secure, intact, with a skilful guide at their head. So had they not every reason to be thankful, to take courage and to press on?

Ward Lancaster appreciating the magnitude of his charge, rode some distance at the head of the train, his eye constantly sweeping the prairie, and his mind taken up with the duty before him. He rode alone, except when some of his friends chose to keep company with him; but these generally found him as morose and incommunicative, that they were glad to fall back again and join the more sociable portion.

The horsemen were scattered all through the train, so that in case of attack they could rally to the defence of any portion without unnecessary delay. As naturally 54 was to be expected, intimate friends and acquaintances found their way into each other’s society.

Warfield and Mr. Bonfield appeared to take a strong liking to each other, for they rode side by side, and chatted in the most pleasant and familiar manner. Little was seen of Florence Brandon. Occasionally she indulged in a few miles walk, but at other times she was in one of the large lumbering covered wagons with Mrs. Bonfield and a maiden aunt. Miss Jamison, whose loquacity equalled that of Leonidas Swipes, and whose bosom seemed incapable of any emotion except that of the importance of keeping her sharp eye and long nose turned toward her ward.

Messrs. Doolittle and Birchem rode side by side; and as neither was heard to utter a syllable to the other, there can be but little doubt but that they vastly enjoyed themselves.

Swipes was getting along handsomely. He appeared to have recovered his spirits entirely, and to have forgotten the brief time he enjoyed the bliss of expected wealth.

“I tell you Mr. Wainwright,” said he, as he rode beside him, shaking his head and gesticulating his long arms, “I’ve an idee.”

“Ah!”

“Yes; it come into my head as I was riding along. I tell you it is an idee that is an idee—bound to make my fortune.”

“As sure as the sheep would have done had they remained in your possession?”

“Y-es-s; but perhaps not quite so fast; but in a much better manner; in a manner that shall make my name famous along the Pacific coast.”

“It must be quite a grand scheme that has entered your head.”

“It is!” was the emphatic response. “One of those idees such as you don’t get more than once in a life time.”

“Do you wish me to share your knowledge of it?”

“Of course I was preparing your mind for it like. What do you think of the Fort Mifflin Institute for the education of youths of both sexes?”

“That certainly sounds well.”

“And ain’t it well—isn’t it grand? And what do you think of it?”

“You will have to be a little more explicit in your statements, before I can give you any decided opinion.”

“Why, as soon as we get to Fort Mifflin I shall erect a building, to be called the Fort Mifflin Institute for the Education of the Youths of both sexes. I shall have a lot of circulars printed.”

“Where will you get them printed?”

“At Fort Mifflin, of course. I believe in supporting home industry; I swun if I ain’t!”

Wainwright laughed.

“There is no printing office within a hundred miles of Fort Mifflin.”

“Whew! is that so? That’ll make some trouble—not much, however,—I can run up to San Francisco or to Sacramento city; have a few thousand circulars printed and distribute them on my way coming back. Jingo! it’s good I’ll have to go so far, don’t you see?”

“Where will you obtain your pupils?”

“From every part of California! Fact is, I should not wonder, after the Institute becomes known thro’ the Atlantic States, I should draw quite a number from there. You see, Mr. Wainwright, I’ve teached before, and I’ve got a reputation up in Connecticut. What do you think of it, Mr. Wainwright?”

“Perhaps you will succeed—hardly as well though as you seem to anticipate. I presume you would run the institution yourself.”

“I shall be the head of course—the principal; but I shall organize a faculty at once. Mr. Doolittle there will be just the man to be professor of mathematics, and Mr. Birchem professor of the natural sciences.”

“Can you get them to do enough talking to fill their positions?”

“Plenty, plenty. Fact is, Mr. Wainwright, teachers do too much talking altogether. They’re just the men for the position, I swan if they aint.”