Title: The Tunnel Under the Channel

Author: Thomas Whiteside

Release date: November 7, 2021 [eBook #66685]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Brian Wilsden, Tim Lindell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Thomas Whiteside

SIMON AND SCHUSTER · NEW YORK · 1962

[5]

In the social history of England, the English Channel, that proud sea passage some three hundred and fifty miles long, has separated that country from the Continent as by a great gulf or a bottomless chasm. However, at its narrowest point, between Dover and Cap Gris-Nez—a distance of some twenty-one and a half miles—the Channel, despite any impression that storm-tossed sea travelers across it may have of yawning profundities below, is actually a body of water shaped less like a marine chasm than like an extremely shallow puddle. Indeed, the relationship of depth to breadth across the Strait of Dover is quite extraordinary, being as one to five hundred. This relationship can perhaps be most graphically illustrated by drawing a section profile of the Channel to scale. If the drawing were two feet long, the straight line representing the level of the sea and the line representing the profile of the Channel bottom would be so close together as to be barely distinguishable from one another. At its narrowest part, the Channel is nowhere more than two hundred and sixteen feet deep, and for half of the distance across, it is less than a hundred feet deep. It is just this extreme shallowness, in combination with strong winds [6]] and tidal currents flowing in the Channel neck between the North Sea and the Atlantic, that makes the seas of the Strait of Dover so formidable, especially in the winter months. The weather is so bad during November and December that the odds of a gale's occurring on any given day are computed by the marine signal station at Dunkirk at one in seven, and during the whole year there are only sixty periods in which the weather remains decent in the Channel through a whole day. Under these difficult conditions, the passage of people traveling across the Channel by ferry between England and France is a notoriously trying one; the experience has been mentioned in print during the last hundred years in such phrases as "that fearful ordeal," "an hour and a half's torture," and "that unspeakable horror." Writing in the Revue des Deux Mondes in 1882, a French writer named Valbert described the trip from Dover to Calais as "two centuries ... of agony." Ninety-odd years ago, an article dealing with the Channel passage, in The Gentleman's Magazine, asserted that hundreds of thousands of people crossing the Strait each year suffered in a manner that beggared description. "Probably there is no other piece of travelling in civilized countries, where, within equal times, so much suffering is endured; certainly it would be hard to find another voyage of equal length which is so much feared," the author said, and he went on to report that only one day out of four was calm, on the average, while about three days in every eight were made dreadful to passengers by heavy weather. He concluded, with feeling, "What wonder that, under such circumstances, patriotism often fails to survive; and that if any wish is felt in mid-Channel, it is that, after all, England was not an island."

How many Englishmen, their loyalty having been subjected to this strain, might express the same wish upon safely gaining high ground again is a question the writer in The [7] Gentleman's Magazine did not venture to discuss. However, there is no question about the persistence with which, during the past century at least, cross-Channel ferry passengers have spoken about or written about the desirability of some sort of dry-land passage between England and France. Engineers have been attracted to the idea of constructing such a passage for at least a hundred and fifty years. During that time, they have come up with proposals for crossing the Channel by spanning it with great bridges, by laying down submersible tubes resting on the sea bottom or floating halfway between sea bed and sea level, or even by using transports shaped like enormous tea wagons, whose wheels would travel along rails below sea level and whose platforms would tower high above the highest waves. But more commonly than by any other means, they have proposed to do away with the hazards and hardships of the Channel boat crossing by boring a traffic tunnel under the rock strata that lie at conveniently shallow depths under sea level. The idea of a Channel tunnel, at once abolishing seasickness and connecting England with the Continent by an easy arterial flow of goods and travelers, always has had about it a quality of grand simplicity—the simplicity of a very large extension of an easily comprehended principle; in this case, digging a hole—that has proved irresistible in appeal to generations not only of engineers but of visionaries and promoters of all kinds.

The tunnel seems always to have had a capacity to arouse in its proponents a peculiarly passionate and unquenchable enthusiasm. Men have devoted their adult lives to promoting the cause of the tunnel, and such a powerful grip does the project seem to have had on the imagination of its various designers that just to look at some of their old drawings—depicting, for example, down to the finest detail of architectural ornamentation, ventilation stations for the tunnel sticking out of the surface of the Channel as ships sail gracefully [8] about nearby—one might almost think that the tunnel was an accomplished reality, and the artist merely a conscientious reporter of an existing scene. Such is the minute detail in which the tunnel has been designed by various people that eighty-six years ago the French Assembly approved a tunnel bill that specified the price of railway tickets for the Channel-tunnel journey, and even contained a clause requiring second-class carriages to be provided with stuffed seats rather than the harder accommodations provided for third-class passengers. And an Englishman called William Collard, who died in 1943, after occupying himself for thirty years with the problem of the Channel tunnel, in 1928 wrote and published a book on the subject that went so far as to work out a time-table for Channel-tunnel trains between Paris and London, complete with train and platform numbers and arrival and departure times at intermediate stations in Kent and northern France. As for the actual engineering details, a Channel tunnel has been the subject of studies that have ranged from collections of mere rough guesses to the most elaborate engineering, geological, and hydrographic surveys carried out by highly competent civil-engineering companies. Interestingly enough, ever since the days, a century or so ago, when practical Victorian engineers began taking up the problem, the technical feasibility of constructing a tunnel under the Channel has never really been seriously questioned. Yet, despite effort piled on effort and campaign mounted on campaign, over all the years, by engineers, politicians, and promoters, nobody has quite been able to push the project through. Up to now, every time the proponents of a tunnel have tried to advance the scheme, they have encountered a difficulty harder to understand, harder to identify, and, indeed, harder to break through than any rock stratum.

The difficulty seems to lie in the degree to which, among Englishmen, the Channel has been not only a body of water [9] but a state of mind. Because of the prevalence of this curious force, the history of the scheme to put a tunnel below the Channel has proved almost as stormy as the Channel waves themselves. Winston Churchill, in an article in the London Daily Mail, wrote in 1936, "There are few projects against which there exists a deeper and more enduring prejudice than the construction of a railway tunnel between Dover and Calais. Again and again it has been brought forward under powerful and influential sponsorship. Again and again it has been prevented." Mr. Churchill, who could never be accused of lacking understanding of the British character, was obliged to add that he found the resistance to the tunnel "a mystery." Some thirty-five times between 1882 and 1950 the subject of the Channel tunnel was brought before Parliament in one form or another for discussion, and ten bills on behalf of the project have been rejected or set aside. On several occasions, the Parliamentary vote on the tunnel has been close enough to bring the tunnel within reach of becoming a reality, and in the eighties the construction of pilot tunnels for a distance under the sea from the English and French coasts was even started. But always the tunnel advocates have had to give way before persistent opposition, and always they have had to begin their exertions all over again. Successive generations of Englishmen have argued with each other—and with the French, who have never showed any opposition to a Channel tunnel—with considerable vehemence. The ranks of pro-tunnel people have included Sir Winston Churchill (who once called the British opposition to the tunnel "occult"), Prince Albert, and, at one point, Queen Victoria; and the people publicly lining themselves up with the anti-tunnel forces have included Lord Randolph Churchill (Sir Winston's father), Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Robert Browning, Professor Thomas Huxley, and, more recently, First Viscount Montgomery of Alamein. Queen Victoria, once pro-tunnel, later turned anti-tunnel; [10] her sometime Prime Minister, William E. Gladstone, took an anti-tunnel position at one period when he was in office, and later, out of it, turned pro-tunnel. Throughout its stormy history the tunnel project has had the qualities of fantasy and nightmare—a thing of airy grace and claustrophobic horror; a long, bright kaleidoscope of promoters' promises and a cavern resounding with Cyclopean bellowing. Proponents of the tunnel have called it an end to seasickness, a boon to peace, international understanding, and trade; and they have hailed it as potentially the greatest civil-engineering feat of their particular century. Its opponents have referred to it sharply as "a mischievous project," and they have denounced it as a military menace that would have enabled the French (or Germans) to use it as a means of invading England—the thought of which, in 1914, caused one prominent English anti-tunneler, Admiral Sir Algernon de Horsey, publicly to characterize as "unworthy of consideration" the dissenting views of pro-tunnelers, whom he contemptuously referred to as "those poor creatures who have no stomach for an hour's sea passage, and who think retention of their dinners more important than the safety of their country." Over the years, anti-tunnel forces have used as ammunition an extraordinary variety of further arguments, which have ranged from objections about probable customs difficulties at the English and French ends of the tunnel to suspicions that a Channel tunnel would make it easier for international Socialists to commingle and conspire.

Behind all these given reasons, no matter how elaborate or how special they might be, there has always lurked something else, a consideration more subtle, more elusive, more profound, and less answer able than any specific objections to the construction of a Channel tunnel—the consideration of England's traditional insular position, the feeling that somehow, if England were to be connected by a tunnel with the [11] Continent, the peculiar meaning, to an Englishman, of being English would never be quite the same again. It is this feeling, no doubt, that in 1882 motivated an article on the tunnel, in so sober a publication as The Solicitors' Journal, to express about it an uneasiness bordering on alarm, on the ground that, if successful, the construction of a tunnel would "effect a change in the natural geographical condition of things." And it is no doubt something of the same feeling that prompted Lord Randolph Churchill, during a speech attacking a bill for a Channel tunnel before the House of Commons in 1889—the bill was defeated, of course—to observe skillfully that "the reputation of England has hitherto depended upon her being, as it were, virgo intacta."

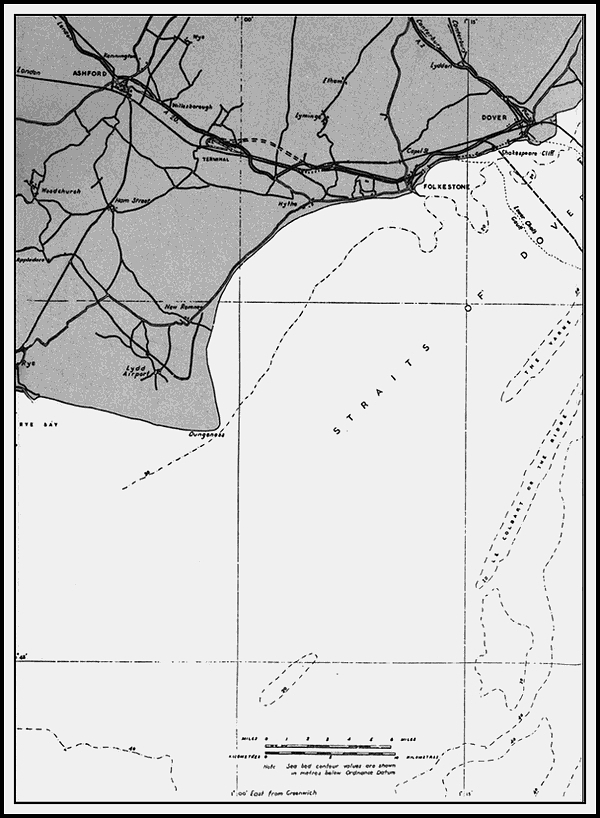

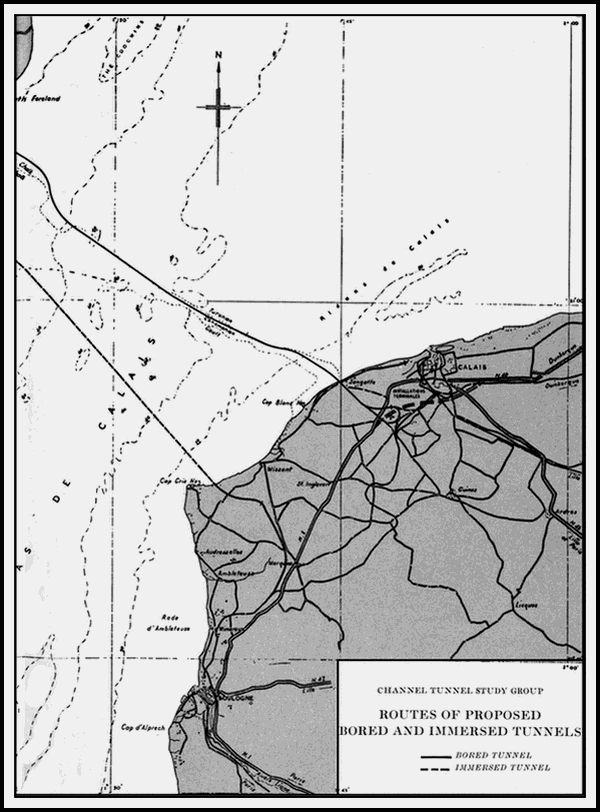

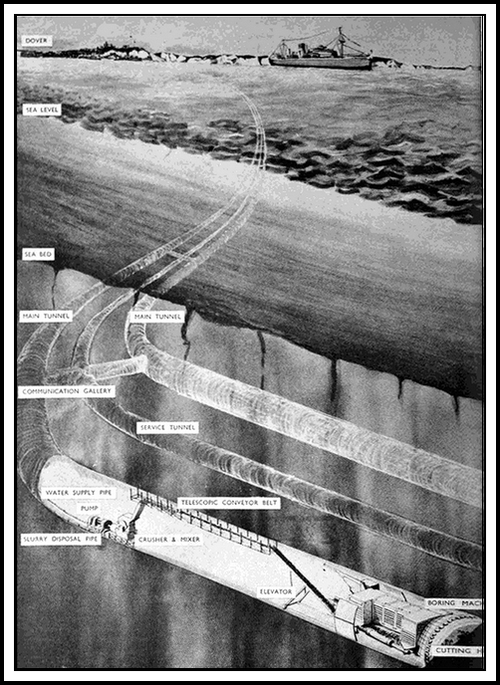

If the proponents and promoters of the tunnel have never quite succeeded in putting their project across in all the years, they have never quite given up trying, either; and now, in a new strategic era of nuclear rockets, a new era of transport in which air ferries to the Continent carry cars as well as passengers, and a new era of trade, marked by the emergence and successful growth of the European Economic Community, or Common Market, the pro-tunnel forces have been at it again, in what one of the leading pro-tunnelers has called "a last glorious effort to get this thing through." This time they have encountered what they consider to be the most encouraging kind of progress in the entire history of the scheme. In April, 1960, an organization called the Channel Tunnel Study Group announced, in London, a new series of proposals for a Channel tunnel, based on a number of recent elaborate studies on the subject. The proposals called for twin parallel all-electric railway tunnels, either bored or immersed, with trains that would carry passengers and transport, in piggyback fashion, cars, buses, and trucks. The double tunnel, if of the immersed kind, would be 26 miles long between portals. A bored tunnel, as planned, would be 32 miles [12] long and would be by far the longest traffic tunnel of either the underwater or under-mountain variety in the world. The longest continuous subaqueous traffic tunnel in existence is the rail tunnel under the Mersey, connecting Liverpool and Birkenhead, a distance of 2.2 miles; the longest rail tunnel through a mountain is the Simplon Tunnel, 12.3 miles in length. The Channel tunnel would run between the areas of Sangatte and Calais on the French side, and between Ashford and Folkestone on the English side. Trains would travel through it at an average speed of 65 miles an hour, reaching 87 miles an hour in some places, and at rush hours they would be capable of running 4,200 passengers and 1,800 vehicles on flatcars every hour in each direction. While a true vehicular tunnel could also be constructed, the obviously tremendous problems of keeping it safely ventilated at present make this particular project, according to the engineers, prohibitively expensive to build and maintain. The train journey from London to Paris via the proposed tunnel would take four hours and twenty minutes; the passenger trains would pass through the tunnel in about thirty minutes. Passengers would pay 32 shillings, or $4.48–$2.92 cheaper than the cost of a first-class passenger ticket on the Dover-Calais sea-ferry—to ride through the tunnel; the cost of accompanied small cars would be $16.48, a claimed 30 per cent less than a comparable sea-ferry charge. The tunnel would take four to five years to build, and the Study Group estimated that, including the rail terminals at both ends, it would cost approximately $364,000,000.

All that the Study Group, which represents British, French and American commercial interests, needs to go ahead with the project and turn it into a reality is—besides money, and the Study Group seems to be confident that it can attract that—the approval of the British and French Governments of the scheme. For all practical purposes, the French [13] Government never has had any objection to a fixed installation linking both sides of the Channel, and as far as the official British attitude is concerned, when the British Government announced, in July, 1961, that it would seek full membership in the European Common Market, most of the tunnel people felt sure that the forces of British insularity which had hindered the development of a tunnel for nearly a century at last had been dealt a blow to make them reel. But what raised the pro-tunnelers' excitement to the greatest pitch of all was the decision of the French and British Governments, last October, to hold discussions on the problem of building either a bridge or a tunnel. When these discussions got under way last November, the main question before the negotiators was the economic practicality of such a huge undertaking.

Yet, with all the encouragement, few of the pro-tunnelers in England seem willing to make a flat prediction that the British Government will actively support the construction of a tunnel. They have been disappointed too often. Then again, despite the generally high hopes that this time the old strategic objections to the construction of a tunnel have been pretty well forgotten, pro-tunnelers are well aware that a number of Englishmen with vivid memories of 1940 are still doubtful about the project. "The Channel saved us last time, even in the age of the airplane, didn't it?" one English barrister said a while ago, in talking of his feelings about building the Channel tunnel. The tunnel project has the open enmity of Viscount Montgomery, who has made repeated attacks on it and who in 1960 demanded, in a newspaper interview, that before the Government took any stand on behalf of such a project, "The British people as a whole should be consulted and vote on the Channel tunnel as part of a General-Elections program." And, to show that the spirit of the anti-tunnelers has not lost its resilience, [14] Major-General Sir Edward L. Spears, in the correspondence columns of the London Times in April of that same year, denounced the latest Channel-tunnel scheme as "a plan which will not only cost millions of public money, but will let loose on to our inadequate roads eighteen hundred more vehicles an hour, each driven by a right-of-the-road driver in a machine whose steering wheel is on the left."

[15]

The first scheme for the construction of a tunnel beneath the English Channel was put forward in France, in 1802, by a mining engineer named Albert Mathieu, who that year displayed plans for such a work in Paris, at the Palais du Luxembourg and the École Nationale Supérieure des Mines. Mathieu's tunnel, divided into two lengths totaling about eighteen and a half miles, was to be illuminated by oil lamps and ventilated at intervals by chimneys projecting above the sea into the open air, and its base was to be a paved way over which relays of horses would gallop, pulling coachloads of passengers and mail between France and England in a couple of hours or so of actual traveling time, with changes of horses being provided at an artificial island to be constructed in mid-Channel. Mathieu managed to have his project brought to the attention of Napoleon Bonaparte, the First Consul, who was sufficiently impressed with it to bring it to the attention of Charles James Fox during a personal meeting of the two men during the Peace of Amiens. Fox described it as "one of the great enterprises we can now undertake together." But the project got no further than this talking stage. In 1803, a Frenchman named de Mottray came [16] up with another proposal for creating a passage underneath the Channel. It consisted of laying down sections of a long, submerged tube on top of the sea bed between England and France, the sections being linked together in such a way as to form a watertight tunnel. However, Mottray's project petered out quickly, too, and the subject of an undersea connection between the two countries lay dormant until 1833, when it attracted the attention of a man named Aimé Thomé de Gamond, a twenty-six-year-old French civil engineer and hydrographer of visionary inclinations.

Thomé de Gamond was to turn into an incomparably zealous and persistent projector of ways in which people could cross between England and France without getting wet or seasick; he devoted himself to the problem for no less than thirty-four years, and had no hesitation in exposing himself to extraordinary physical dangers in the course of his researches. Unlike the plans of his predecessors, Thomé de Gamond's were based upon fairly systematic hydrographic or geological surveys of the Channel area. In 1833 he made the first of these surveys by taking marine soundings to establish a profile of the sea bottom in a line between Calais and Dover; on the basis of this, he drew up, in 1834, a plan for a submerged iron tube that was to be laid down in prefabricated sections on the bed of the Strait of Dover and then lined with masonry, the irregular bottom of the sea meanwhile having been prepared to receive the tube through the leveling action of a great battering-ram and rake operated from the surface by boat. By 1835, Thomé de Gamond modified this scheme by eliminating the prefabricated tube in favor of a movable hydrographic shield that would slowly advance across the Channel bottom, leaving a masonry tube behind it as it progressed. But the rate of progress, he calculated, would be slow; the work was to take thirty years to complete, or fifteen years if work began on two shores [17] simultaneously. Thomé de Gamond moved on to schemes for other ways of crossing the Channel, and between 1835 and 1836 he turned out, successively, detailed plans for five types of cross-Channel bridges. They included a granite-and-steel bridge of colossal proportions, and with arches "higher than the cupola of St. Paul's, London," which was to be built between Ness Corner Point and Calais; a flat-bottomed steam-driven concrete-and-stone ferryboat, of such size as to constitute "a true floating island," which would travel between two great piers each jutting out five miles into the Channel between Ness Corner Point and Cap Blanc-Nez; and a massive artificial isthmus of stone, which would stretch from Cap Gris-Nez to Dover and block the neck of the English Channel except for three transverse cuttings spanned by movable bridges, which Thomé de Gamond allowed across his work for the passage of ships. Thomé de Gamond was particularly fond of his isthmus scheme. He traveled to London and there promoted it vigorously among interested Englishmen during the Universal Exhibition of 1851, but he reluctantly abandoned it because of objections to its high estimated cost of £33,600,000 and to what he described as "the obstinate resistance of mariners, who objected to their being obliged to ply their ships through the narrow channels."

Such exasperating objections to joining England and France above water sent Thomé de Gamond back to the idea of doing the job under the sea, and between 1842 and 1855 he made various energetic explorations of the Channel area in an attempt to determine the feasibility of driving a tunnel through the rock formations under the Strait. Geological conditions existing in the middle of the Strait were, up to that time, almost entirely a matter of surmise, based on observations made on the British and French sides of the Channel, and in the process of finding out more about them, [18] Thomé de Gamond decided to descend in person to the bottom of the Channel to collect geological specimens. In 1855, at the age of forty-eight, he had the hardihood to make a number of such descents, unencumbered by diving equipment, in the middle of the Strait. Naked except for wrappings that he wound about his head to keep in place pads of buttered lint he had plastered over his ears, to protect them from high water pressure, he would plunge to the bottom of the Channel, weighted down by bags of flints and trailing a long safety line attached to his body, and a red distress line attached to his left arm, from a rowboat occupied also by a Channel pilot, a young assistant, and his own daughter, who went along to keep watch over him. On the deepest of these descents, at a point off Folkestone, Thomé de Gamond, having put a spoonful of olive oil into his mouth as a lubricant that would allow him to expel air from his lungs without permitting water at high pressure to force its way in, dived down weighted by four bags of flints weighing a total of 180 pounds. About his waist he wore a belt of ten inflated pig's bladders, which were to pull him rapidly to the surface after he had scooped up his geological specimen from the Channel bed and released his ballast, and, using this system, he actually touched bottom at a depth of between 99 and 108 feet. His ascent from this particular dive was not unremarkable, either; in an account of it, he wrote that just after he had left the bottom of the Channel with a sample of clay

... I was attacked by voracious fish, which seized me by the legs and arms. One of them bit me on the chin, and would at the same time have attacked my throat if it had not been preserved by a thick handkerchief.... I was fortunate enough not to open my mouth, and I reappeared on top of the water after being immersed [19] fifty-two seconds. My men saw one of the monsters which had assailed me, and which did not leave me until I had reached the surface. They were conger eels.

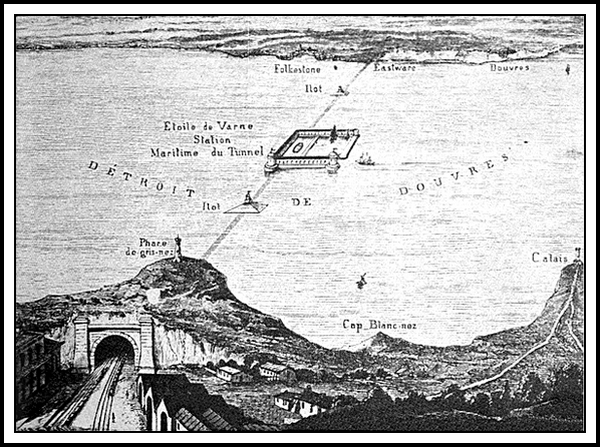

Thomé de Gamond's geological observations, although they were certainly sketchy by later standards, were enough to convince him of the feasibility of a mined tunnel under the Channel, and in 1856 he drew up plans for such a work. This was to be a stone affair containing a double set of railroad tracks. It was to stretch twenty-one miles, from Cap Gris-Nez to Eastwear Point, and from these places was to connect, by more than nine miles at each end of sloping access tunnels, with the French and British railway systems. The junctions of the sloping access tunnels and the main tunnel itself were to be marked by wide shafts, about three hundred feet deep, at the bottom of which travelers would encounter the frontier stations of each nation. The line of the main tunnel was to be marked above the surface by a series of twelve small artificial islands made of stone. These were to be surmounted with lighthouses and were to contain ventilating shafts connecting with the tunnel. Thomé de Gamond prudently provided the ventilation shafts in his plans with sea valves, so that in case of war between England and France each nation would have the opportunity of flooding the tunnel on short notice. The tunnel was designed to cross the northern tip of the Varne, a narrow, submerged shelf that lies parallel to the English coast about ten miles off Folkestone, and so close to the surface that at low tide it is only about fifteen feet under water at its highest point. Thomé de Gamond planned to raise the Varne above water level, thus converting it into an artificial island, by building it up with rocks and earth brought to the spot in ships. Through this earth, engineers would dig a great shaft down [20] to the level of the tunnel, so that the horizontal mining of the tunnel as a whole could be carried on from four working faces simultaneously, instead of only two. The great shaft was also to serve as a means of ventilating the tunnel and communicating with it from the outside, and around its apex Thomé de Gamond planned, with a characteristically grand flourish, an international port called the Étoile de Varne, which was to have four outer quays and an interior harbor, as well as amenities such as living quarters for personnel and a first-class lighthouse. As for the shaft leading down to the railway tunnel, according to alternate versions of Thomé de Gamond's plan, it was to be at least 350 feet—and possibly as much as 984 feet—in diameter, and 147 feet deep; and, according to a contemporary account in the Paris newspaper La Patrie, "an open station [would be] formed as spacious as the court of the Louvre, where travelers might halt to take air after running a quarter of an hour under the bottom of the Strait."

From the bottom of this deep station, trains might also ascend by means of gently spiraling ramps to the surface of the Étoile de Varne, La Patrie reported. The newspaper went on to invite its readers to contemplate the panorama at sea level:

Imagine a train full of travelers, after having run for fifteen minutes in the bowels of the earth through a splendidly lighted tunnel, halting suddenly under the sky, and then ascending to the quays of this island. The island, rising in mid-sea, is furnished with solid constructions, spacious quays garnished with the ships of all nations; some bound for the Baltic or the Mediterranean, others arriving from America or India. In the distance to the North, her silver [21] cliffs extending to the North, reflected in the sun, is white Albion, once separated from all the world, now become the British Peninsula. To the South ... is the land of France.... Those white sails spread in the midst of the Straits are the fishing vessels of the two nations.... Those rapid trains which whistle at the bottom of the subterranean station are from London or Paris in three or four hours.

In the spring of 1856, Thomé de Gamond obtained an audience with Napoleon III and expounded his latest plan to him. The Emperor reacted with interest and told the engineer that he would have a scientific commission look into the matter "as far as our present state of science allows." The commission found itself favorable to the idea of the work in general but lacking a good deal of necessary technical information, and it suggested that some sort of preliminary agreement between the British and French Governments on the desirability of the tunnel ought to be reached before a full technical survey was made. Encouraged by the way things seemed to be going, Thomé de Gamond set about promoting his scheme more energetically than ever. He obtained a promise of collaboration from three of Britain's most eminent engineers—Robert Stephenson, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, and Joseph Locke—and in 1858 he traveled to London to advance the cause of the tunnel among prominent people and to promote it in the press. Leading journals were receptive to the idea. An article in the Illustrated London News referred to the proposed tunnel as "this great line of junction," and said that it would put an end to the commercial isolation that England was being faced with by the creation on the Continent of a newly unified railway system that was making it possible to ship goods from Central to Western Europe [22] without breaking bulk. The article added that the creation of the tunnel

... would still preserve for this country for the future that maritime isolation which formed its strength throughout the past; for the situation of the tunnel beneath the bed of the sea would enable the government on either coast, in case of war, as a means of defense, to inundate it immediately.... According to the calculations of the engineer, the tunnel might be completely filled with water in the course of an hour, and afterwards three days would be required, with the mutual consent of the two Governments, to draw off the water, and reestablish the traffic.

Thomé de Gamond's visit to England was climaxed by a couple of interviews on the subject of the Channel tunnel that he obtained with Prince Albert, who supported the idea with considerable enthusiasm and even took up the matter in private with Queen Victoria. The Queen, who was known to suffer dreadfully from seasickness, told Albert, who relayed the message to Thomé de Gamond, "You may tell the French engineer that if he can accomplish it, I will give him my blessing in my own name and in the name of all the ladies of England." However, in a discussion Thomé de Gamond had earlier had with Her Majesty's Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston, who was present at one of the engineer's interviews with Albert, the idea of the tunnel was not so well received. The engineer found Palmerston "rather close" on the subject. "What! You pretend to ask us to contribute to a work the object of which is to shorten a distance which we find already too short!" Thomé de Gamond quoted him as exclaiming when the tunnel project was mentioned. And, according [23] to an account by the engineer, when Albert, in the presence of both men, spoke favorably of the benefits to England of a passage under the Channel, Lord Palmerston "without losing that perfectly courteous tone which was habitual with him" remarked to the Prince Consort, "You would think quite differently if you had been born on this island."

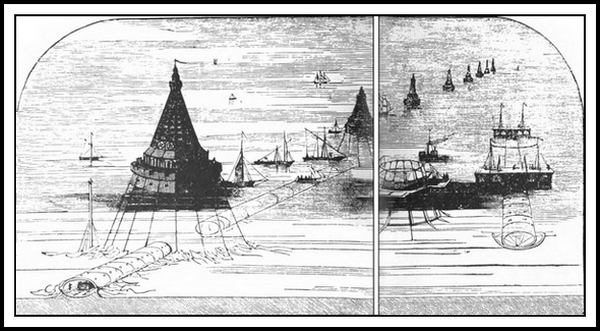

While Thomé de Gamond was occupied with his submarine-crossing projects, other people were producing their own particular tunnel schemes. Most of them seem to have been for submerged tubes, either laid down directly on the sea bed or raised above its irregularities by vertical columns to form a sort of underwater elevated railway. Perhaps the most ornamental of these various plans was drawn up by a Frenchman named Hector Horeau, in 1851. It called for a prefabricated iron tube containing a railway to be laid across the Channel bed along such judiciously inclined planes as to allow his carriages passage through them without their having to be drawn by smoke-bellowing locomotives—a suffocatingly real problem that most early Channel-tunnel designers, including, apparently, Thomé de Gamond, pretty well ignored. The slope given to Horeau's underground railway was to enable the carriages to glide down under the Channel from one shoreline with such wonderful momentum as to bring them to a point not far from the other, the carriages being towed the rest of the way up by cables attached to steam winches operated from outside the tunnel exit. The tunnel itself would be lighted by gas flames and, in daytime, by thick glass skylights that would admit natural light filtering down through the sea. The line of the tube was to be marked, across the surface of the Channel, by great floating conical structures resembling pennanted pavilions in some medieval tapestry. The pavilions were to be held in place by strong cables anchored to the Channel bottom; they were also to contain marine warning beacons. This project never got under the ground.

[24]

In 1858, an attempt to assassinate Napoleon III brought France into the Italian war against Austria, and when word spread in France that the assassin's bombs had been made in Birmingham, a chill developed between the French and British Governments. This led to a wave of fear in England that another Napoleon might try a cross-Channel invasion. All this froze out Thomé de Gamond's tunnel-promoting for several years. He did not try again until 1867, when he exhibited a set of revised plans for his Varne tunnel at the Universal Exhibition in Paris. In doing so he concluded that he had pushed the cause of the tunnel about to the limit of his personal powers. Thirty-five years of work devoted to the problem had cost him a moderate personal fortune, and he was obliged to note in presenting his plan that "the work must now be undertaken by collective minds well versed in the physiology of rocks and the workings of subterranean deposits." After that, Thomé de Gamond retired into the background, squeezed out, it may be, by other tunnel promoters. In 1875, an article in the London Times that mentioned his name in passing reported that he was "living in humble circumstances, his daughter supporting him by giving lessons on the piano." He died in the following year.

Although Thomé de Gamond's revised plan of 1867 came to nothing in itself, it did cause renewed talk about a Channel tunnel. The new spirit of free trade was favorable to it among Europeans, and everybody was being greatly impressed with reports of the striking progress on various great European engineering projects of the time that promised closer communication between nations—the successful cutting of the Isthmus of Suez, the near completion of the 8.1-mile-long Mount Cenis rail tunnel, and the opening, only a few years previously, of the 9.3-mile-long St. Gotthard Tunnel, for example. Hardly any great natural physical barriers between neighboring nations seemed beyond the ability of the great [25] nineteenth-century engineers to bridge or breach, and to many people it appeared logical enough that the barrier of the Dover Strait should have its place on the engineers' list of conquests. In this generally propitious atmosphere, an Englishman named William Low took up where Thomé de Gamond left off. Shortly after the Universal Exhibition, Low came up with a Channel tunnel scheme based principally upon his own considerable experience as an engineer in charge of coal mines in Wales. Low proposed the creation of a pair of twin tunnels, each containing a single railway track, and interconnected at intervals by short cross-passages. The idea was a technically striking one, for it aimed at making the tunnels, in effect, self-ventilating by making use of the action of a train entering a tunnel to push air in front of it and draw fresh air in behind itself. According to Low's scheme, this sort of piston action, repeated on a big scale by the constant passage of trains bound in opposite directions in the two tunnels, was supposed to keep air moving along each of the tunnels and between them through the cross-passages in such a way as to allow for its steady replenishment through the length of the tunnels. With modifications, Low's concept of a double self-ventilating tunnel forms the basis for the plan most seriously advanced by the Channel Tunnel Study Group in 1960.

After showing his plans to Thomé de Gamond, who approved of them, Low obtained the collaboration of two other Victorian engineers—Sir John Hawkshaw, who in 1865 and 1866 had had a number of test borings made by a geologist named Hartsink Day in the bed of the Channel in the areas between St. Margaret's Bay, just east of Dover, and Sangatte, just north-east of Calais, and had become convinced that a Channel tunnel was a practical possibility in geological terms; and Sir James Brunlees, an engineer who had helped build the Suez Canal. In 1867, an Anglo-French committee of [26] Channel-tunnel promoters submitted a scheme for a Channel tunnel based on Low's plan to a commission of engineers under Napoleon III, and the promoters asked for an official concession to build the tunnel. The members of the commission were unanimous in regarding the scheme as a workable one, although they balked at an accompanying request of the promoters that the British and French Governments each guarantee interest on a million sterling, which would be raised privately, to help get the project under way, and took no action. But apart from the question of money the promoters were encouraged. In 1870 they persuaded the French Government officially to ask the British Government what support it would be willing to give to the proposed construction of a Channel railway tunnel. Consideration of the question in Whitehall got sidetracked for a while by the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian war in the same year, but in 1872, after further diplomatic enquiries by the French Government, the British Government eventually replied that it found no objection "in principle" to a Channel tunnel, provided it was not asked to put up money or guarantee of any kind in connection with it and provided that ownership of the tunnel would not be a perpetual private monopoly. In the same year, a Channel Tunnel Company was chartered in England, with Lord Richard Grosvenor, chairman of the London, Chatham & Dover Railway, at its head, and with Hawkshaw, Low, and Brunlees as its engineers. The tunnel envisioned by the company would stretch from Dover to Sangatte, and its cost, including thirty-three miles of railway that would connect on the English side with the London, Chatham & Dover and the South-Eastern Railways, and on the French side with the Chemin de Fer du Nord, would be £10,000,000. Three years later, the English company sought and obtained from Parliament temporary powers to buy up private land at St. Margaret's Bay, in Kent, for the purpose of going ahead with [27] experimental tunneling work there. At the same time, a newly formed French Channel Tunnel Company backed by the House of Rothschild and headed by an engineer named Michel Chevalier obtained by act of the French legislature permission from the French Government to start work on a tunnel from the French side at an undetermined point between Boulogne and Calais, and a concession to operate the French section of the tunnel for ninety-nine years. The cahier des charges of the French tunnel bill dealt in considerable detail with the terms under which the completed tunnel was to be run, down to providing a full table of tariffs for the under-Channel railroad. Thus, a first-class passenger riding through the tunnel in an enclosed carriage furnished with windows would be charged fifty centimes per kilometre. Freight rates were established for such categories as furniture, silks, wine, oysters, fresh fish, oxen, cows, pigs, goats, and horse-drawn carriages with or without passengers inside.

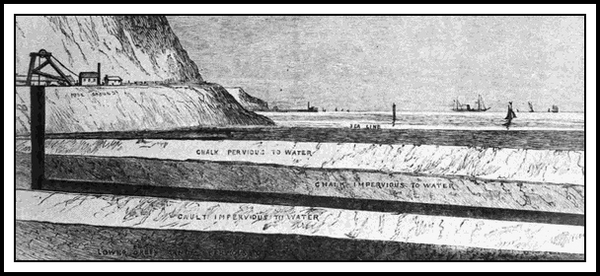

The greatest uncertainty facing the two companies, now that they had the power to start digging toward each other's working sites, consisted of their lack of foreknowledge of geological obstacles they might encounter in the rock masses lying between the two shores at the neck of the Channel. However, the companies' engineers had substantial reasons for believing that, in general, the region and stratum into which they planned to take the tunnel were peculiarly suited to their purpose. Their belief was based on a rough reconstruction—a far more detailed reconstruction is available nowadays, of course—of various geological events occurring in the area before there ever was a Channel. A hundred million years ago, in the Upper Cretaceous period of the Mesozoic era, a great part of southern England, which had been connected at its easterly end with the Continental land mass, was inundated, along with much of Western Europe, by the ancient Southern Sea. As it lay submerged, this sea-washed [28] land accumulated on its surface, over a period of ten million years, layers of white or whitish mud about nine hundred feet thick and composed principally of the microscopic skeletons of plankton and tiny shells. Eventually the mud converted itself into rock. Then, for another forty million years, at just the point where the neck of the Dover Strait now is, very gentle earth movements raised the level of this rock to form a bar-shaped island some forty miles long. By Eocene times this Wealden Island, stretching westward across the Calais-Dover area, actually seems to have been the only bit of solid ground standing out in a seascape of a Western Europe inundated by the Eocene sea. When most of France and southern England reappeared above the surface, in Miocene times, this island welded them together; later, in the ice age, the Channel isthmus disappeared and emerged again four times with the rise and fall of the sea caused by the alternate thawing and refreezing of the northern icecap. When each sequence of the ice age ended, the land bridge remained, high and dry as ever, and it was over this isthmus that paleolithic man shambled across from the Continent, in the trail of rhinoceroses, hippopotamuses, giant boars, and other great beasts whose fossilized bones have been found in the Wealden area.

Encroaching seas made a channel through the isthmus and cut the Bronze Age descendants of this breed of men off from the Continent about six thousand years ago. Then fierce tidal currents coursing between the North Sea and the Atlantic widened the breach still further until, as recently as four thousand years ago (or only about a couple of thousand years before Caesar's legions invaded Britain by boat), the sea wore away the rock of the isthmus to approximately the present width of the Strait, leaving exposed high at each side the eroded rock walls, formerly the whitish mudbank of Cretaceous times—now the white chalk cliffs of the Dover [29] and Calais areas. Providentially for the later purposes of Channel tunnelers, however, the seas that divided England from the Continent also left behind them a thin remnant of the old land connection in the form of certain chalk layers that still stretched in gentle folds across the bottom of the Strait, and it was through this area of remaining chalk that the Victorian engineers planned to drive their tunnel headings. Even more providentially, they had the opportunity of extending their headings under the Channel through a substratum of chalk almost ideal for tunneling purposes, known as the Lower Chalk. Unlike the two layers of cretaceous rock that lie above it—the white Upper Chalk and the whitish Middle Chalk, both of which are flint-laden, heavily fissured, and water-bearing, and consequently almost impossible to tunnel in for any distance—the Lower Chalk (it is grayish in color) is virtually flint-free and nearly impermeable to water, especially in the lower parts of the stratum, where it is mixed with clay; at the same time it is stable, generally free of fissures, and easy to work. From the coastline between Folkestone and South Foreland, north-east of Dover, where its upper level is visible in the cliffs, the Lower Chalk dips gently down into the Strait in a north-easterly direction and disappears under an outcropping Middle Chalk, and emerges again on the French side between Calais and Cap Blanc-Nez. Given this knowledge and their knowledge of the state of Lower Chalk beds on land areas, the Victorian engineers were confident that the ribbon of Lower Chalk extending under the Strait would turn out to be a continuous one. To put this view to a further test, the French Channel Tunnel Company, in 1875, commissioned a team of eminent geologists and hydrographers to make a more detailed survey of the area than had yet been attempted. In 1875 and 1876 the surveyors made 7,700 soundings and took 3,267 geological samples from the bed of the Strait and concluded from their studies that, except for a couple of localities near each shoreline, which a tunnel could avoid, the Lower Chalk indeed showed every sign of stretching without interruption or fault from shore to shore. However, when these [30] studies were completed, Lord Grosvenor's Channel Tunnel Company did not find itself in a position to do much about them. The company was having trouble raising money, and its temporary power to acquire land at St. Margaret's Bay for experimental workings had lapsed without the promoters ever having used it. William Low, who had left the company in 1873 after disagreements with Hawkshaw on technical matters—Low had come to believe, for one thing, that the terrain around St. Margaret's Bay was unsuitable as a starting place for a channel tunnel—had become the chief engineering consultant of a rival Channel-tunnel outfit that called itself the Anglo-French Submarine Railway Company. But the Anglo-French Submarine Railway Company wasn't getting anywhere, either. It remained for a third English company, headed by a railway magnate named Sir Edward Watkin, to push the Channel-tunnel scheme into its next phase, which turned out to be the most tumultuous one in all its history.

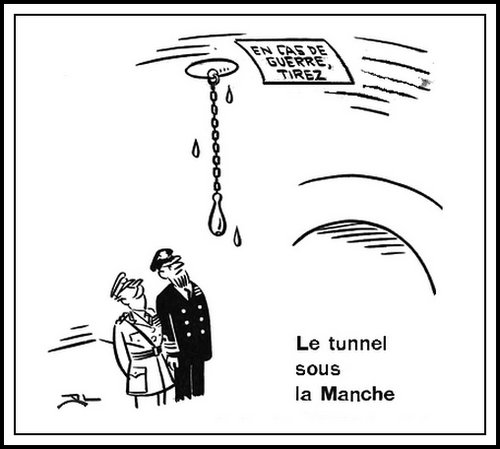

This cartoon depicting the horrors of the Channel crossing originally

appeared in Punch in 1869. In 1961, 92 years later, Punch found it

as timely as ever.

THE GREAT

TUNNEL SCHEMERS

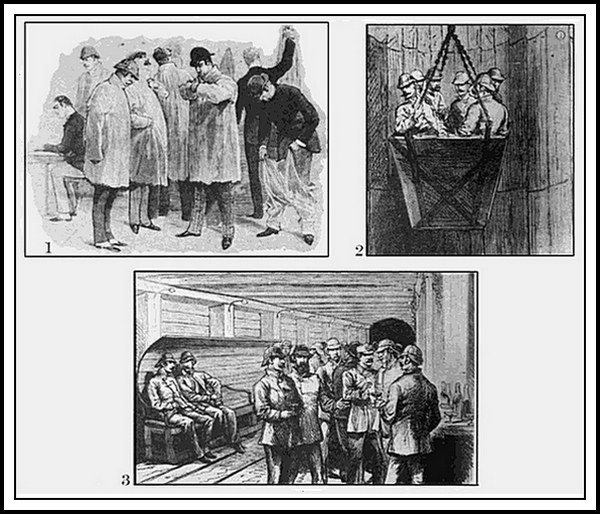

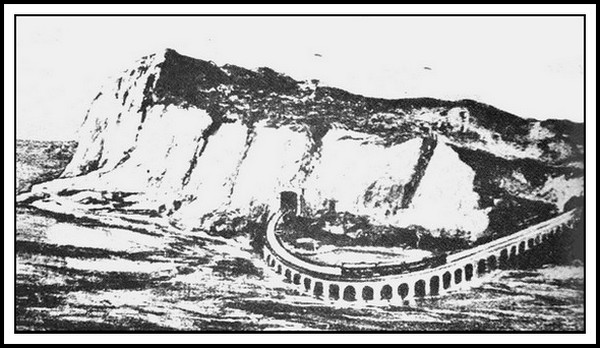

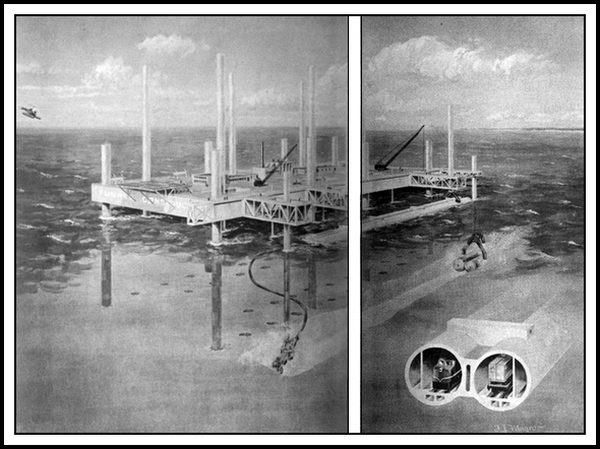

Everybody who was anybody went down into the tunnel to inspect the new undersea road to France.

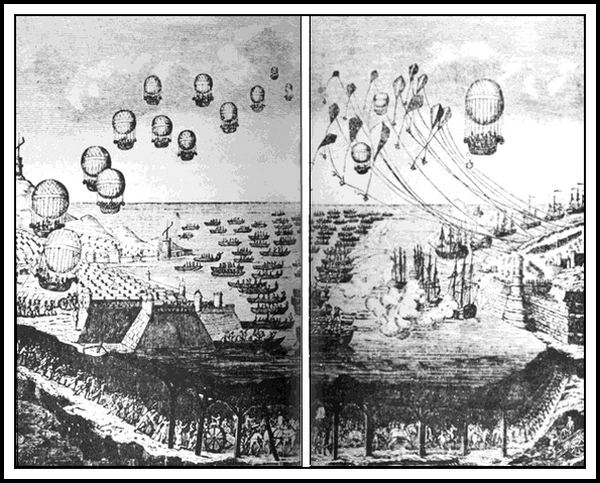

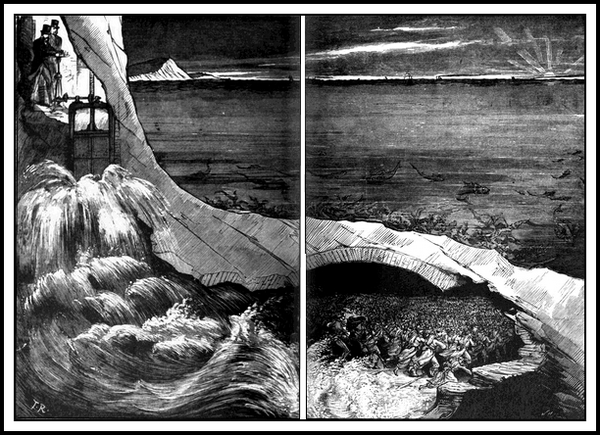

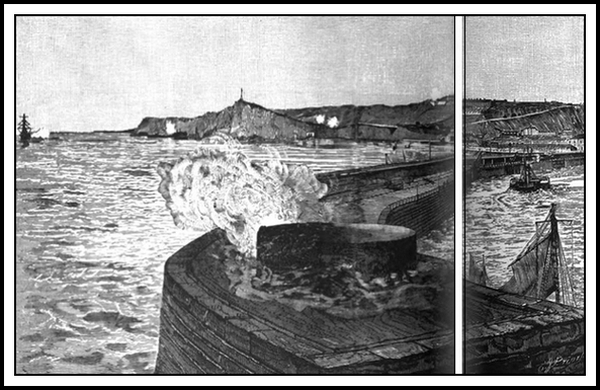

How to have a tunnel and still keep England safe from invasion

is a problem that has attracted the attention of artists since the eighties.

[31]

SIR EDWARD WATKIN was a vociferously successful promoter from the Midlands. The son of a Manchester cotton merchant, Watkin had passed up a chance at the family business in favor of railways in the early days of the age of steam, and it is a measure of his generally acknowledged shrewdness at railway promotion that in his mid-twenties, having become secretary of the Trent Valley Railway, he negotiated its sale to the London North Western Railway at a profit of £438,000. Now in his early sixties, Watkin was chairman of three British railway companies, the Manchester, Sheffield Lincolnshire Railway, the Metropolitan (London) Railway, and the South-Eastern Railway—the last-named being a company whose line ran from London to Dover via Folkestone—and one of his big current schemes was the formation of a through route under a single management—his own, naturally—from Manchester and the north to Dover. It was while he was busily promoting this scheme that Watkin caught the Channel-tunnel fever. He realized that part of the land the South-Eastern Railway owned along its line between Folkestone and Dover lay happily accessible to the ribbon of Lower Chalk that [32] dipped into the sea in the direction of Dover and stretched under the bed of the Strait, and it wasn't long before he was conjuring up visions of a great system in which his projected Manchester-Dover line, instead of stopping at the Channel shoreline, would carry on under the Strait to the Continent.

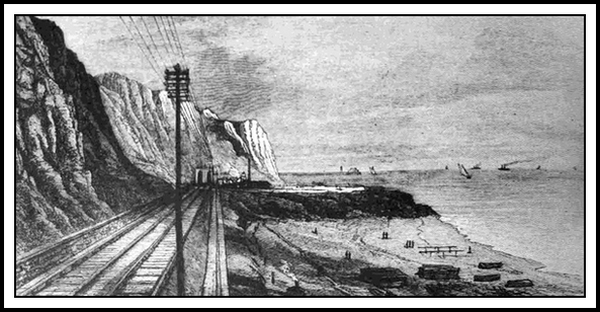

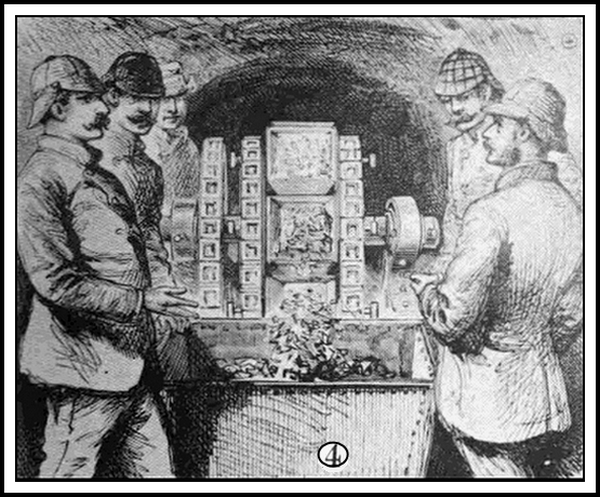

One of Sir Edward Watkin's first steps toward determining the technical feasibility of constructing a tunnel was to call in, sometime in the mid-seventies, William Low, whose own tunnel company had quite fallen apart, for engineering consultation. Watkin decided to aim for a twin tunnel based on Low's idea, which would have its starting point in the area west of Dover and east of Folkestone, and he put his own engineers to work on the job. In 1880, the engineers sank a seventy-four-foot shaft by the South-Eastern Railway line at Abbots Cliff, about midway between Folkestone and Dover, and began driving a horizontal pilot gallery seven feet in diameter along the Lower Chalk bed in the direction of the sea off Dover. By the early part of the following year, the experimental heading extended about half a mile underground. His engineers having satisfied themselves that the Lower Chalk was lending itself as well as expected to being tunneled, Sir Edward went ahead and formed the Submarine Continental Railway Company, capitalized at £250,000 and closely controlled by the South-Eastern Railway Company, to take over the existing tunnel workings and to continue them on a larger scale, with the aim of constructing a Channel tunnel connecting with the South-Eastern's coastal rail line. At the same time, he reached an understanding with the French Channel Tunnel Company on co-ordination of English and French operations; he also engineered through Parliament—he was an M.P. himself, and that helped things a bit—a bill giving the South-Eastern power to carry out the [33] compulsory purchase of certain coastal land in the general direction taken by the existing heading.

Then Sir Edward's engineers sank a second shaft, farther to the east but in alignment with the first heading, 160 feet below a level stretch of ground by the South-Eastern Railway line at Shakespeare Cliff, just west of Dover, 120 feet below high water, and began boring a new seven-foot pilot tunnel that dipped down with the Lower Chalk bed leading into the Channel. This second boring, like the first, was carried out with the use of a tunneling machine especially designed for the purpose by Colonel Frederick Beaumont, an engineer who had had a hand in the construction of the Dover fortifications. The Beaumont tunneling machine, a prototype of some of the most powerful tunneling machines in use nowadays, was run by compressed air piped in from the outside, and the discharge of this air from the machine as it worked also served as a way of keeping the gallery ventilated. The cutting of the rock was done by a total of fourteen steel planetary cutters set in two revolving arms at the head of the machine; with each turn of the borer a thin paring of chalk 5/16 of an inch thick was shorn away from the working face, the spoil being passed by conveyor belt to the back of the machine and dumped into carts or skips that were pushed by hand along the length of the gallery on narrow-gauge rails. The machine made one and a half to two revolutions a minute, and Sir Edward estimated for his stockholders that with simultaneous tunneling with the use of similar equipment from the French shore—the French Tunnel Company had already sunk a 280-foot shaft of its own at Sangatte and was preparing to drive a gallery toward England—the Channel bottom would be pierced from shore to shore by a continuous single pilot tunnel, twenty-two miles long, in three and a half years. Once this was done, according to Sir Edward's plans, the seven-foot gallery was to be enlarged by [34] special cutting machinery to a fourteen-foot diameter, and a double tunnel, thickly lined with concrete and connected by cross-passages, constructed. (Four miles of access tunnel were to be added on the French, and possibly on the English, side, too.) The completed tunnel was to be lighted throughout by electric light—a novelty already being tried out in the pilot tunnel by the well-known electrical engineer C. W. Siemens—and the trains that ran through it between France and Britain were to be hauled by locomotives designed by Colonel Beaumont. Instead of being run by smoke-producing coal, the locomotives were to be propelled by compressed air carried behind the engine in tanks, and, like the Beaumont tunneling machine, the engine was supposed to keep the tunnel ventilated by giving out fresh air as it went along. (A lot of air was to be released in the tunnel in the course of a day; a tentative schedule called for one train to traverse it in one direction or another every five minutes or so for twenty hours out of the twenty-four.)

Trains coming through the tunnel from France were to emerge into the daylight and the ordinary open air of England either from a four-mile-long access tunnel connected to the South-Eastern's railway line at Abbots Cliff or—this was a favored alternative plan of Sir Edward's—at Shakespeare Cliff via a station to be constructed in a great square excavated a hundred and sixty feet deep in the ground, which would be covered over with glass, lighted by electric light, and equipped "with large waiting rooms and refreshment rooms." From the abyss of this submerged station, trains arriving from the Continent were to be raised, an entire train at a time, to the level of the existing South-Eastern line by a giant hydraulic lift. (Actually, constructing an elevator capable of raising such an enormous load would not seem as unlikely a feat in the eighties as it might to many people now; Victorian engineers were expert in the use of hydraulic [35] power for ship locks and all sorts of other devices, and, in fact, hydraulic power was so commonly used that the London of half a century ago had perhaps eight hundred miles of hydraulic piping laid below the streets to work industrial presses, motors, and most of the cranes on the Thames docks.)

As the experimental work progressed, Sir Edward Watkin saw to it that all the splendid details about the Channel-tunnel scheme were constantly brought to the attention of the South-Eastern's shareholders, the press, and the public. Sir Edward, besides being a nineteenth-century railway king, was also something of a twentieth-century public-relations operator. He was a firm believer in the beneficial effects of giving big dinners, a pioneer in the art of organizing big junkets, and an adept at getting plenty of newspaper space. An energetic lobbyist in Parliament for all sorts of causes, not excluding his own commercial projects, he was known as a habitual conferrer of friendly little gestures upon important people in and out of government, and his kindness is said to have gone so far at one time that he provided Mr. Gladstone with the convenience of a private railway branch line that went right to the statesman's country home.

The driving of the Channel-tunnel pilot gallery at Shakespeare Cliff offered Sir Edward a handy opportunity for exercising his gifts in the field of public relations, and he took full advantage of it. Week after week, as the boring of the tunnel progressed, he invited large groups of influential people, as many as eighty at a time, including politicians and statesmen, editors, reporters, and artists, members of great families, well-known financiers and businessmen from Britain and abroad, and members of the clergy and the military establishment to be his guests on a trip by special train from London to Dover at Shakespeare Cliff. There, at the Submarine Continental Railway Company workings, the visitors [36] were taken down into the tunnel to inspect the creation of the new experimental highway to the Continent. A typical enough descriptive paragraph in the press concerning one of these visits (on this occasion a group of prominent Frenchmen were the guests of Sir Edward) is contained in a contemporary report in the Times:

The visitors were lowered six at a time in an iron "skip" down the shaft into the tunnel. At the bottom of this shaft, 163 feet below the surface of the ground, the mouth of the tunnel was reached, and the visitors took their seats on small tramcars which were drawn by workmen. So evenly has the boring machine done its work that one seemed to be looking along a great tube with a slightly downward set, and as the glowing electric lamps, placed alternately on either side of the way, showed fainter and fainter in the far distance, the tunnel, for anything one could tell from appearances, might have had its outlet in France.

Sir Edward Watkin, in a speech he made at a Submarine Continental Railway Company stockholders' meeting shortly after such a visit (the main parts of the speech were duly paraphrased in the press), found the effect of the electric light (operated on something called the Swan system) in the tunnel to be just as striking as the Times reporter had—only brighter.

He thought the visit might be regarded as a remarkable one. Their colleague, Dr. Siemens, lighted up the tunnel with the Swan light, and it was certainly a beautiful sight to see a cavern, as it were, under the bottom of the sea made in places as brilliant as daylight.

[37]

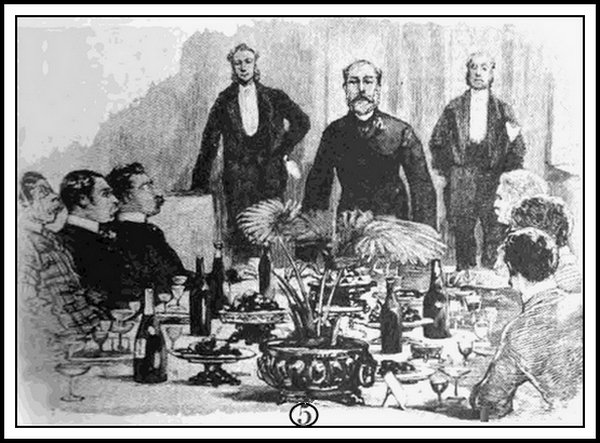

While on their way by tramcar to view the working of Colonel Beaumont's boring machine at the far end of the tunnel, visitors stopped after a certain distance to enjoy another experience—a champagne party held in a chamber cut in the side of the tunnel. A contemporary artist's sketch in the Illustrated London News records the sight of a group of visitors clustered around a bottle-laden table at one of these way side halts. Mustachioed and bearded, and wearing Sherlock Holmes deerstalker caps and dust jackets, they are shown, in tableaued dignity, standing about within a solidly timbered cavelike area with champagne glasses in their hands; and for all the Victorian pipe-trouser formality of their posture there is no doubt that the subjects are having a good time. After such a refreshing pause, the visitors would be helped on the tramcars again and escorted on to see the boring machine cutting through the Lower Chalk and to admire the generally dry appearance of the tunnel, and after that they would be taken back to the surface and given a splendid lunch either in a marquee set up near the entrance to the shaft or at the Lord Warden Hotel, in Dover, where more champagne would be served, along with other wines and brandies, more toasts to the Queen's health proposed, and speeches made on the present and future marvels of the tunnel, the forwardness of its backers, and the new era in international relations that the whole project promised. These lunches were also convenient occasions for the speakers to pooh-pooh the claims of the rival tunnel scheme of Lord Richard Grosvenor's Channel Tunnel Company, which was still being put forward, although entirely on paper, and to make announcements of miscellaneous items of news about progress in the Lower Chalk.

Thus, at one of these lunches at the Lord Warden Hotel held in the third week of February, 1882, Mr. Myles Fenton, the general manager of the South-Eastern Railway, took occasion [38] to announce to a large party of visitors from London that boring of the gallery had now reached a distance of eleven hundred yards, or nearly two-thirds of a mile, in the direction of the end of the great Admiralty Pier at Dover. According to an account in the Times, Mr. Fenton read to the interested gathering a telegram he had received from Sir Edward, who was unable to be present, but who by wire "expressed the hope that by Easter Week a locomotive compressed air engine would be running in the tunnel, of which it was expected the first mile would by that time have been made. (Cheers.)"

Sometimes these lunches were held down in the tunnel itself, and general conditions down there were such that even ladies attended them, on special occasions, as a contemporary magazine account of a visit paid to the gallery by a number of engineers with their families makes clear.

The visitors were conducted twenty at a time to the end on a sort of trolley or benches on wheels drawn by a couple of men. In the centre of the tunnel a kind of saloon, decorated with flowers and evergreens, was arranged, and, on a large table, glasses and biscuits, etc., were spread for the inevitable luncheon. There was no infiltration of water in any part. In the places where several small fissures and slight oozings had appeared during the boring operations, a shield in sheet iron had been applied against the wall by the engineer, following all the circumference of the gallery and making it completely watertight. There they were as in a drawing-room, and the ladies having descended in all the glories of silks and lace and feathers were astonished to find themselves as [39] immaculate on their return as at the beginning of their trip. The atmosphere in the tunnel was not less pure, but even fresher than outside, thanks to the compressed air machine which, having acted on the excavator at the beginning of the cutting, released its cooled air in the centre of the tunnel.

With the widespread talk of champagne under the sea, potted plants flourishing under the electric lights, and bracing breezes blowing within the Lower Chalk, going down from London to attend one of Sir Edward's tunnel parties seems to have become one of the fashionable things to do in English society in the early part of 1882. By the beginning of spring, visitors taken down into the tunnel and entertained by Sir Edward included such eminent figures as the Lord Mayor of London, the Archbishop of Canterbury, and the Prince and Princess of Wales. To judge by this stage of affairs, the boring of the tunnel was going on under the most agreeable of auspices.

Behind all the sociability and the stream of publicity engendered in the press by the visits of well-known people to the tunnel, the situation was not quite so promising. While the physical boring was going ahead smoothly enough in the Lower Chalk, the promotion of the tunnel as a full-scale project was encountering growing resistance from within the upper crust of The Establishment. The fact seems to be that the British Government had never felt altogether easy about the idea of the Channel tunnel from the start, and although it had never formally expressed any misgivings about the scheme as a whole, it had always been careful not to associate itself with the enterprise, and its attitude toward its progress generally had been one of reluctant acquiescence. Whatever disquiet people in government felt about the tunnel project [40] appears to have been expressed in three general ways—first, in the introduction of caveats of a military nature; second, in proposals to delay the progress of the scheme on other than military grounds; and third, in a general, nameless suspicion of the whole idea. Such reservations had been evident even in 1875, when the Channel Tunnel Company applied to Parliament for powers to carry out experimental work at St. Margaret's Bay.

To exemplify the first kind of reservation put forward, the Board of Trade, the governmental department under whose surveillance such commercial schemes came, made a point of insisting that for defense purposes the Government must retain absolute power to "erect and maintain such [military] works at the English mouth of the Tunnel as they may deem expedient," and in case of actual or threatened war to close the tunnel down. As for the tendency of governmental people to find other grounds for objection in the project, this could be exemplified by the delaying action of the Secretary to the Treasury, when in 1875 it looked as though Parliament were about to take action on the Channel-tunnel bill. In a memorandum to the Foreign Office, the Secretary sought to have the tunnel bill laid aside at the last moment of its consideration before Parliament so that the answers to all sorts of important jurisdictional questions could be sought—for example, "If a crime were committed in the Tunnel, by what authority would it be cognizable?"[1] And as for the third, unnamed kind of objection, Queen Victoria, who, with her late husband (Prince Albert died in 1861), had once been so [41] enthusiastic about the idea of a Channel tunnel, simply changed her mind about the entire business; in February of 1875, the Queen wrote Disraeli, without elaborating, that "she hopes that the Government will do nothing to encourage the proposed tunnel under the Channel which she thinks very objectionable."

Ever since 1875, all these official doubts and misgivings had continued to lurk in the background of the Government's dealings with the Channel-tunnel promoters—especially military misgivings about the scheme. Apart from putting down the usual bloody insurrections among native populations while she went about the business of maintaining her colonial territories, Britain was at peace with the world. As far as her military relations with the Continent stood, the threats of Napoleon I to invade the island had not been forgotten, and even in the reign of Napoleon III there had been occasional alarms about an invasion, but the country's physical separation from the Continent tended to make the military tensions existing over there seem rather comfortingly remote. Britain's home defenses were left on a pretty easygoing basis, the country's reliance on resistance to armed attack being placed, in traditional fashion, in the power of the Royal Navy to control her seas—meaning, for all practical purposes, its ability to control the Channel. With the Navy and the Channel to protect her shores, Britain in the seventies and eighties got along at home with a professional army of only sixty thousand men, as against a standing army in France of perhaps three-quarters of a million. Seasickness or no seasickness, the Channel was considered to be a convenient manpower and tax-money saver. The advantages of the Channel to Victorian England were perhaps most eloquently expressed by Mr. Gladstone in the course of an article of his in the Edinburgh Review in 1870 on England's relationship to the military and political turmoil existing on the Continent. [42] "Happy England!" he wrote in a brief panegyric on the Channel. "Happy ... that the wise dispensation of Providence has cut her off, by that streak of silver sea, which passengers so often and so justly execrate ... partly from the dangers, absolutely from the temptations, which attend upon the local neighborhood of the Continental nations.... Maritime supremacy has become the proud—perhaps the indefectible—inheritance of England." And Mr. Gladstone went on, after dwelling upon one of his favorite themes, the evils of standing armies and the miserable burden of conscription, to suggest that Englishmen didn't realize just how grateful they ought to be for the Channel:

Where the Almighty grants exceptional and peculiar bounties, He sometimes permits by way of counterpoise an insensibility to their value. Were there but a slight upward heaving of the crust of the earth between France and Great Britain, and were dry land thus to be substituted for a few leagues of sea, then indeed we should begin to know what we had lost.

These remarks of Mr. Gladstone's on the Channel appear to have made a powerful impression on opinion in upper-class England; for many years after their publication his partly Shakespearean phrase, "the streak of silver sea"—or a variation of it, "the silver streak"—remained as a standard term in the vocabulary of Victorian patriotism. Not surprisingly, considering his views in 1870, the attitude of Mr. Gladstone in 1881 and 1882, during his term as Prime Minister, toward the plan of Sir Edward Watkin to undermine those Straits the statesman had so extolled was an equivocal one.

Indeed, quite a number of people in and around Whitehall had considerably stronger reservations about the Channel-tunnel project than Mr. Gladstone did. These misgivings [43] had to do with fears that a completed tunnel under the Channel might form a breach in England's traditional defense system, and in June of 1881 they first came to public notice in the form of an editorial in the Times. Discussing the Channel-tunnel project, the Times, while conceding that "As an improvement in locomotion, and as a relief to the tender stomachs of passengers who dread seasickness, the design is excellent," went on to observe that "from a national [and military] point of view it must not the less be received with caution." And the paper asked, "Shall we be as well off and as safe with it as we now are without it? Will it be possible for us so to guard the English end of the passage that it can never fall into any other hands than our own?" The Times frankly doubted it, and questioned whether, if the tunnel were built, "a force of some thousands of men secretly concentrated in a [French] Channel port and suddenly landed on the coast of Kent" might not be able by surprise to seize the English end of the tunnel and use it as a bridgehead for a general invasion of England. At the very least, the paper warned, the construction of the tunnel meant that "a design for the invasion of England and a general plan of the campaign will be subjects on which every cadet in a German military school will be invited to display his powers," and it suggested that in the circumstances the Channel had best be left untunneled. "Nature is on our side at present," the Times concluded gravely, "and she will continue so if we will only suffer her. The silver streak is our safety." The author of a letter to the Times printed in the same issue declared that the tunnel, if constructed, could be seized by the French from within as easily as from without, and that "in three hours a cavalry force might be sent through to seize the approaches at the English end."

To all this Sir Edward Watkin replied easily that the tunnel, when it was finished, could at any time be rendered unusable [44] from the British end by "a pound of dynamite or a keg of gunpowder." However, the negative attitude of a journal as influential as the Times was a setback for the project. As a result, the Government increased its caution about the tunnel. When, at the end of 1881, Sir Edward drew up a private bill for presentation during the coming year to Parliament that would formally grant the South-Eastern full authority to buy further coastal lands in the Shakespeare Cliff area and to complete the construction of and to maintain a Channel tunnel (Lord Richard Grosvenor and the proprietors of the London, Chatham & Dover Railway came up with a similar bill on behalf of the Channel Tunnel Company), the Board of Trade held departmental hearings on the rival schemes, and at these hearings further attention was turned to the question of the military security of the tunnel in the event of its being attacked. At these proceedings, Sir Edward, who appeared for the purpose of testifying to the civilizing magnificence of his project, was put somewhat on the defensive by questions about the desirability of the tunnel from a military point of view. He found himself in the disconcerting position of being obliged to show not so much the practicability of building a Channel tunnel as the practicability of disabling or destroying it. However, making the most of the situation, he declared that fortifying the English end of the tunnel, and knocking it out of commission in case of hostile action by another power, was a simple enough matter to be accomplished in any number of ways—by flooding it, by filling it with steam, by bringing it under the gunfire of the Dover fortifications, by exploding electrically operated mines laid in it, or choking it with shingle dumped in from the outside. (There was even mention, at the hearings, of a proposal to pour "boiling petroleum" down upon invaders.) Getting into the spirit of the thing in spite of himself, Sir Edward told the examining committee confidently, [45] "I will give you the choice of blowing up, drowning, scalding, closing up, suffocating and other means of destroying our enemies.... You may touch a button at the Horse Guards and blow the whole thing to pieces."

Notwithstanding Sir Edward's categorical assurances, the wisdom of constructing the tunnel came under vigorous attack at the hearings from a formidably high official military source—from Lieutenant-General Sir Garnet Wolseley, the Adjutant General of the British Army. A veteran of the Crimean War and the Indian Mutiny who was considered to be an expert on the art of surprise attack—his routing of such foes as King Koffee in the first Ashanti War of 1873-74, as well as the great promptitude with which he was said to have "restored the situation" in the Zulu War, made him a well-known figure to the British public—Sir Garnet Wolseley had a dual reputation as an imperialist general and a soldier with advanced ideas on reform of the supply system of the British Army. In fact, his enthusiasm for efficiency was such that the phrase "All Sir Garnet" was commonly used in the Army as a way of saying "all correct." The actor George Grossmith made himself up as Wolseley to sing the part of "a modern Major-General" in performances in the eighties of Gilbert and Sullivan's The Pirates of Penzance. Sir Garnet later became Lord Wolseley and Commander-in-Chief of the British Army. Sir Garnet Wolseley's opinions of the tunnel project were very strong ones. In a long memorandum he submitted to the Board of Trade committee examining the tunnel project, he described the Channel as "a great wet ditch" for the protection of England, the like of which, he said, no Continental power, if it possessed one instead of a land frontier, would "cast recklessly away, by allowing it to be tunnelled under." And he denounced the construction of a Channel tunnel on the ground that it would [46] be certain to create what he termed "a constant inducement to the unscrupulous foreigner to make war upon us." In agitated language, General Wolseley invoked the opinion of the late Duke of Wellington that England could be invaded successfully, and he reiterated the fear previously expressed by the Times that the English end of the tunnel might be seized from the outside—before any of its defenders had a chance of setting in motion the mechanisms for blocking it up—by a hostile force landing nearby on British soil, whereupon it could readily be converted into a bridgehead for a general invasion of the country. He also declared that "the works at our end of the tunnel may be surprised by men sent through the tunnel itself, without landing a man upon our shores." General Wolseley went on to show just how the deed could be done:

A couple of thousand armed men might easily come through the tunnel in a train at night, avoiding all suspicion by being dressed as ordinary passengers, and the first thing we should know of it would be by finding the fort at our end of the tunnel, together with its telegraph office, and all the electrical arrangements, wires, batteries, etc., intended for the destruction of the tunnel, in the hands of an enemy. We know that ... trains could be safely sent through the tunnel every five minutes, and do the entire distance from the station at Calais to that at Dover in less than half an hour. Twenty thousand infantry could thus be easily despatched in 20 trains and allowing ... 12 minutes interval between each train, that force could be poured into Dover in four hours.... The invasion of England could not be attempted by [47] 5,000 men, but half that number, ably led by a daring, dashing young commander might, I feel, some dark night, easily make themselves masters of the works at our end of the tunnel, and then England would be at the mercy of the invader.

General Wolseley conceded that an attack from within the tunnel itself would be difficult if even a hundred riflemen at the English end had previously been alerted to the presence of the attackers, but he doubted that the vigilance of the defenders could always maintain itself at the necessary pitch. And he put it to the committee: "Since the day when David secured an entrance by surprise or treachery into Jerusalem through a tunnel under its walls, how often have places similarly fallen? and, I may add, will again similarly fall?" General Wolseley also found highly questionable the efficacy of the various measures proposed for the protection of the tunnel. He declared that "a hundred accidents" could easily render such measures useless. Thus, for example, he found fault with proposals to lay electrically operated mines inside the tunnel ("A galvanic battery is easily put out of order; something may be wrong with it just when it is required ... the gunpowder may be damp"); proposals to admit the sea into the tunnel by explosion ("an uncertain means of defense"); and proposals to flood it by sluice-gates at the English end ("These water conduits [might] become choked or unserviceable when required" and the "drains rendered useless by treachery"). Then, after pointing out all the frailties of the contemplated defenses, General Wolseley went on to assert that the construction of the tunnel would necessitate, at very least, the conversion of Dover at enormous expense into a first-class fortress and that it could very well make necessary the introduction into England on a permanent [48] basis of compulsory military service to meet the increased threat to Britain's national security.

Surely [Sir Garnet concluded] John Bull will not endanger his birth-right, his property, in fact all that man can hold most dear ... simply in order that men and women may cross to and fro between England and France without running the risk of seasickness.

Sir Garnet reinforced the arguments against the tunnel in personal testimony before the committee. In this testimony he emphasized, among other things, his conviction that once an enemy got a foothold at Dover, England would find herself utterly unable "short of the direct interposition of God Almighty"—an eventuality that Sir Garnet did not appear to count on very heavily—to raise an army capable of resisting the invaders. And the inevitable result of such a default, Sir Garnet told the committee, would be that England "would then cease to exist as a nation."