TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number],

and the footnotes have been placed at the end of each major section.

Three asterisks * * * indicates text omitted by the author from a quotation.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

These are indicated by a dotted gray underline.

BY COMMAND OF His late Majesty WILLIAM THE IVTH.

and under the Patronage of

Her Majesty the Queen.

HISTORICAL RECORDS,

OF THE

British Army

Comprising the

History of every Regiment

IN HER MAJESTY’S SERVICE.

By Richard Cannon Esqre.

Adjutant Generals Office, Horse Guards.

London.

Printed by Authority.

THE THIRTY-FIRST,

OR,

THE HUNTINGDONSHIRE REGIMENT OF FOOT.

LONDON: PRINTED BY W. CLOWES AND SONS, STAMFORD STREET,

FOR HER MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE.

HORSE-GUARDS,

1st January, 1836.

His Majesty has been pleased to command that,

with the view of doing the fullest justice to Regiments,

as well as to Individuals who have distinguished

themselves by their Bravery in Action

with the Enemy, an Account of the Services of

every Regiment in the British Army shall be published

under the superintendence and direction of

the Adjutant-General; and that this Account shall

contain the following particulars, viz.:—

—— The Period and Circumstances of the Original

Formation of the Regiment; The Stations at which it

has been from time to time employed; The Battles,

Sieges, and other Military Operations in which it has

been engaged, particularly specifying any Achievement

it may have performed, and the Colours,

Trophies, &c., it may have captured from the

Enemy.

—— The Names of the Officers, and the number of

Non-Commissioned Officers and Privates Killed or

Wounded by the Enemy, specifying the place and

Date of the Action.

[ii]

—— The Names of those Officers who, in consideration

of their Gallant Services and Meritorious

Conduct in Engagements with the Enemy, have

been distinguished with Titles, Medals, or other

Marks of His Majesty’s gracious favour.

—— The Names of all such Officers, Non-Commissioned

Officers, and Privates, as may have

specially signalized themselves in Action.

And,

—— The Badges and Devices which the Regiment

may have been permitted to bear, and the

Causes on account of which such Badges or Devices,

or any other Marks of Distinction, have been

granted.

By Command of the Right Honorable

GENERAL LORD HILL,

Commanding-in-Chief.

John Macdonald,

Adjutant-General.

The character and credit of the British Army must

chiefly depend upon the zeal and ardour by which

all who enter into its service are animated, and

consequently it is of the highest importance that any

measure calculated to excite the spirit of emulation,

by which alone great and gallant actions are achieved,

should be adopted.

Nothing can more fully tend to the accomplishment

of this desirable object than a full display of the noble

deeds with which the Military History of our country

abounds. To hold forth these bright examples to

the imitation of the youthful soldier, and thus to

incite him to emulate the meritorious conduct of those

who have preceded him in their honorable career,

are among the motives that have given rise to the

present publication.

The operations of the British Troops are, indeed,

announced in the “London Gazette,” from whence

they are transferred into the public prints: the

achievements of our armies are thus made known at

the time of their occurrence, and receive the tribute[iv]

of praise and admiration to which they are entitled.

On extraordinary occasions, the Houses of Parliament

have been in the habit of conferring on the Commanders,

and the Officers and Troops acting under

their orders, expressions of approbation and of thanks

for their skill and bravery; and these testimonials,

confirmed by the high honour of their Sovereign’s

approbation, constitute the reward which the soldier

most highly prizes.

It has not, however, until late years, been the practice

(which appears to have long prevailed in some of

the Continental armies) for British Regiments to keep

regular records of their services and achievements.

Hence some difficulty has been experienced in obtaining,

particularly from the old Regiments, an authentic

account of their origin and subsequent services.

This defect will now be remedied, in consequence

of His Majesty having been pleased to command

that every Regiment shall, in future, keep a full and

ample record of its services at home and abroad.

From the materials thus collected, the country

will henceforth derive information as to the difficulties

and privations which chequer the career of those who

embrace the military profession. In Great Britain,

where so large a number of persons are devoted to

the active concerns, of agriculture, manufactures,

and commerce, and where these pursuits have, for so[v]

long a period, been undisturbed by the presence of

war, which few other countries have escaped, comparatively

little is known of the vicissitudes of active

service and of the casualties of climate, to which,

even during peace, the British Troops are exposed in

every part of the globe, with little or no interval of

repose.

In their tranquil enjoyment of the blessings which

the country derives from the industry and the enterprise

of the agriculturist and the trader, its happy

inhabitants may be supposed not often to reflect on

the perilous duties of the soldier and the sailor,—on

their sufferings,—and on the sacrifice of valuable life,

by which so many national benefits are obtained and

preserved.

The conduct of the British Troops, their valour,

and endurance, have shone conspicuously under great

and trying difficulties; and their character has been

established in Continental warfare by the irresistible

spirit with which they have effected debarkations in

spite of the most formidable opposition, and by the

gallantry and steadiness with which they have maintained

their advantages against superior numbers.

In the official Reports made by the respective Commanders,

ample justice has generally been done to

the gallant exertions of the Corps employed; but

the details of their services and of acts of individual[vi]

bravery can only be fully given in the Annals of the

various Regiments.

These Records are now preparing for publication,

under His Majesty’s special authority, by Mr.

Richard Cannon, Principal Clerk of the Adjutant-General’s

Office; and while the perusal of them cannot

fail to be useful and interesting to military men

of every rank, it is considered that they will also

afford entertainment and information to the general

reader, particularly to those who may have served in

the Army, or who have relatives in the Service.

There exists in the breasts of most of those who

have served, or are serving, in the Army, an Esprit

de Corps—an attachment to everything belonging

to their Regiment; to such persons a narrative of

the services of their own Corps cannot fail to prove

interesting. Authentic accounts of the actions of

the great, the valiant, the loyal, have always been

of paramount interest with a brave and civilized

people. Great Britain has produced a race of heroes

who, in moments of danger and terror, have stood

“firm as the rocks of their native shore:” and when

half the world has been arrayed against them, they

have fought the battles of their Country with unshaken

fortitude. It is presumed that a record of

achievements in war,—victories so complete and surprising,

gained by our countrymen, our brothers,[vii]

our fellow-citizens in arms,—a record which revives

the memory of the brave, and brings their gallant

deeds before us,—will certainly prove acceptable to

the public.

Biographical Memoirs of the Colonels and other

distinguished Officers will be introduced in the

Records of their respective Regiments, and the

Honorary Distinctions which have, from time to

time, been conferred upon each Regiment, as testifying

the value and importance of its services, will be

faithfully set forth.

As a convenient mode of Publication, the Record

of each Regiment will be printed in a distinct number,

so that when the whole shall be completed, the

Parts may be bound up in numerical succession.

[viii]

[ix]

INTRODUCTION

TO

THE INFANTRY.

The natives of Britain have, at all periods, been

celebrated for innate courage and unshaken firmness,

and the national superiority of the British troops

over those of other countries has been evinced in

the midst of the most imminent perils. History contains

so many proofs of extraordinary acts of bravery,

that no doubts can be raised upon the facts which

are recorded. It must therefore be admitted, that

the distinguishing feature of the British soldier is

Intrepidity. This quality was evinced by the

inhabitants of England when their country was

invaded by Julius Cæsar with a Roman army, on

which occasion the undaunted Britons rushed into

the sea to attack the Roman soldiers as they descended

from their ships; and, although their discipline

and arms were inferior to those of their

adversaries, yet their fierce and dauntless bearing

intimidated the flower of the Roman troops, including

Cæsar’s favourite tenth legion. Their arms

consisted of spears, short swords, and other weapons

of rude construction. They had chariots, to the[x]

axles of which were fastened sharp pieces of iron

resembling scythe-blades, and infantry in long

chariots resembling waggons, who alighted and

fought on foot, and for change of ground, pursuit

or retreat, sprang into the chariot and drove off

with the speed of cavalry. These inventions were,

however, unavailing against Cæsar’s legions: in

the course of time a military system, with discipline

and subordination, was introduced, and

British courage, being thus regulated, was exerted

to the greatest advantage; a full development of

the national character followed, and it shone forth

in all its native brilliancy.

The military force of the Anglo-Saxons consisted

principally of infantry: Thanes, and other men of

property, however, fought on horseback. The

infantry were of two classes, heavy and light.

The former carried large shields armed with spikes,

long broad swords and spears; and the latter were

armed with swords or spears only. They had also

men armed with clubs, others with battle-axes and

javelins.

The feudal troops established by William the

Conqueror consisted (as already stated in the Introduction

to the Cavalry) almost entirely of horse;

but when the warlike barons and knights, with their

trains of tenants and vassals, took the field, a proportion

of men appeared on foot, and, although

these were of inferior degree, they proved stout-hearted

Britons of stanch fidelity. When stipendiary

troops were employed, infantry always constituted

a considerable portion of the military force;[xi]

and this arme has since acquired, in every quarter

of the globe, a celebrity never exceeded by the

armies of any nation at any period.

The weapons carried by the infantry, during the

several reigns succeeding the Conquest, were bows

and arrows, half-pikes, lances, halberds, various

kinds of battle-axes, swords, and daggers. Armour

was worn on the head and body, and in course of

time the practice became general for military men

to be so completely cased in steel, that it was

almost impossible to slay them.

The introduction of the use of gunpowder in the

destructive purposes of war, in the early part of the

fourteenth century, produced a change in the arms

and equipment of the infantry-soldier. Bows and

arrows gave place to various kinds of fire-arms, but

British archers continued formidable adversaries;

and, owing to the inconvenient construction and imperfect

bore of the fire-arms when first introduced,

a body of men, well trained in the use of the bow

from their youth, was considered a valuable acquisition

to every army, even as late as the sixteenth

century.

During a great part of the reign of Queen Elizabeth

each company of infantry usually consisted of

men armed five different ways; in every hundred

men forty were “men-at-arms,” and sixty “shot;”

the “men-at-arms” were ten halberdiers, or battle-axe

men, and thirty pikemen; and the “shot” were

twenty archers, twenty musketeers, and twenty

harquebusiers, and each man carried, besides his

principal weapon, a sword and dagger.

[xii]

Companies of infantry varied at this period in

numbers from 150 to 300 men; each company had

a colour or ensign, and the mode of formation recommended

by an English military writer (Sir John

Smithe) in 1590 was:—the colour in the centre of

the company guarded by the halberdiers; the pikemen

in equal proportions, on each flank of the

halberdiers: half the musketeers on each flank of

the pikes; half the archers on each flank of the musketeers,

and the harquebusiers (whose arms were

much lighter than the muskets then in use) in equal

proportions on each flank of the company for skirmishing.[1]

It was customary to unite a number of companies

into one body, called a Regiment, which

frequently amounted to three thousand men: but

each company continued to carry a colour. Numerous

improvements were eventually introduced in the

construction of fire-arms, and, it having been found

impossible to make armour proof against the muskets

then in use (which carried a very heavy ball) without

its being too weighty for the soldier, armour was

gradually laid aside by the infantry in the seventeenth

century: bows and arrows also fell into disuse,

and the infantry were reduced to two classes,

viz.: musketeers, armed with matchlock muskets,[xiii]

swords, and daggers; and pikemen, armed with pikes

from fourteen to eighteen feet long, and swords.

In the early part of the seventeenth century

Gustavus Adolphus, King of Sweden, reduced the

strength of regiments to 1000 men. He caused the

gunpowder, which had heretofore been carried in

flasks, or in small wooden bandoliers, each containing

a charge, to be made up into cartridges, and

carried in pouches; and he formed each regiment

into two wings of musketeers, and a centre division

of pikemen. He also adopted the practice of forming

four regiments into a brigade; and the number

of colours was afterwards reduced to three in each

regiment. He formed his columns so compactly that

his infantry could resist the charge of the celebrated

Polish horsemen and Austrian cuirassiers; and his

armies became the admiration of other nations. His

mode of formation was copied by the English,

French, and other European states; but so great

was the prejudice in favour of ancient customs, that

all his improvements were not adopted until near a

century afterwards.

In 1664 King Charles II. raised a corps for sea-service,

styled the Admiral’s regiment. In 1678

each company of 100 men usually consisted of 30

pikemen, 60 musketeers, and 10 men armed with

light firelocks. In this year the King added a company

of men armed with hand grenades to each of

the old British regiments, which was designated the

“grenadier company.” Daggers were so contrived

as to fit in the muzzles of the muskets, and bayonets,[xiv]

similar to those at present in use, were adopted about

twenty years afterwards.

An Ordnance regiment was raised in 1685, by

order of King James II., to guard the artillery, and

was designated the Royal Fusiliers (now 7th Foot).

This corps, and the companies of grenadiers, did

not carry pikes.

King William III. incorporated the Admiral’s

regiment in the second Foot Guards, and raised

two Marine regiments for sea-service. During the

war in this reign, each company of infantry (excepting

the fusiliers and grenadiers) consisted of 14

pikemen and 46 musketeers; the captains carried

pikes; lieutenants, partisans; ensigns, half-pikes;

and serjeants, halberds. After the peace in 1697 the

Marine regiments were disbanded, but were again

formed on the breaking out of the war in 1702.[2]

During the reign of Queen Anne the pikes were

laid aside, and every infantry soldier was armed

with a musket, bayonet, and sword; the grenadiers

ceased, about the same period, to carry hand grenades;

and the regiments were directed to lay aside

their third colour: the corps of Royal Artillery was

first added to the Army in this reign.

About the year 1745, the men of the battalion

companies of infantry ceased to carry swords; during[xv]

the reign of George II. light companies were added

to infantry regiments; and in 1764 a Board of

General Officers recommended that the grenadiers

should lay aside their swords, as that weapon had

never been used during the Seven Years’ War. Since

that period the arms of the infantry soldier have been

limited to the musket and bayonet.

The arms and equipment of the British Troops have

seldom differed materially, since the Conquest, from

those of other European states; and in some respects

the arming has, at certain periods, been allowed to

be inferior to that of the nations with whom they

have had to contend; yet, under this disadvantage,

the bravery and superiority of the British infantry

have been evinced on very many and most trying

occasions, and splendid victories have been gained

over very superior numbers.

Great Britain has produced a race of lion-like

champions who have dared to confront a host of

foes, and have proved themselves valiant with any

arms. At Crecy, King Edward III., at the head of

about 30,000 men, defeated, on the 26th of August,

1346, Philip King of France, whose army is said to

have amounted to 100,000 men; here British valour

encountered veterans of renown:—the King of Bohemia,

the King of Majorca, and many princes and

nobles were slain, and the French army was routed

and cut to pieces. Ten years afterwards, Edward

Prince of Wales, who was designated the Black

Prince, defeated, at Poictiers, with 14,000 men,

a French army of 60,000 horse, besides infantry,

and took John I., King of France, and his son[xvi]

Philip, prisoners. On the 25th of October, 1415,

King Henry V., with an army of about 13,000

men, although greatly exhausted by marches, privations,

and sickness, defeated, at Agincourt, the

Constable of France, at the head of the flower of

the French nobility and an army said to amount to

60,000 men, and gained a complete victory.

During the seventy years’ war between the United

Provinces of the Netherlands and the Spanish monarchy,

which commenced in 1578 and terminated

in 1648, the British infantry in the service of the

States-General were celebrated for their unconquerable

spirit and firmness;[3] and in the thirty

years’ War between the Protestant Princes and the

Emperor of Germany, the British Troops in the service

of Sweden and other states were celebrated for

deeds of heroism.[4] In the wars of Queen Anne,

the fame of the British army under the great

Marlborough was spread throughout the world;

and if we glance at the achievements performed

within the memory of persons now living, there is

abundant proof that the Britons of the present age

are not inferior to their ancestors in the qualities[xvii]

which constitute good soldiers. Witness the deeds

of the brave men, of whom there are many now

surviving, who fought in Egypt in 1801, under the

brave Abercromby, and compelled the French army,

which had been vainly styled Invincible, to evacuate

that country; also the services of the gallant

Troops during the arduous campaigns in the Peninsula,

under the immortal Wellington; and the

determined stand made by the British Army at

Waterloo, where Napoleon Bonaparte, who had

long been the inveterate enemy of Great Britain,

and had sought and planned her destruction by

every means he could devise, was compelled to

leave his vanquished legions to their fate, and to

place himself at the disposal of the British Government.

These achievements, with others of recent

dates in the distant climes of India, prove that the

same valour and constancy which glowed in the

breasts of the heroes of Crecy, Poictiers, Agincourt,

Blenheim, and Ramilies, continue to animate the

Britons of the nineteenth century.

The British Soldier is distinguished for a robust

and muscular frame,—intrepidity which no danger

can appal,—unconquerable spirit and resolution,—patience

in fatigue and privation, and cheerful obedience

to his superiors. These qualities,—united with

an excellent system of order and discipline to regulate

and give a skilful direction to the energies and

adventurous spirit of the hero, and a wise selection

of officers of superior talent to command, whose

presence inspires confidence,—have been the leading

causes of the splendid victories gained by the British[xviii]

arms.[5] The fame of the deeds of the past and

present generations in the various battle-fields where

the robust sons of Albion have fought and conquered,

surrounds the British arms with a halo of glory;

these achievements will live in the page of history to

the end of time.

The records of the several regiments will be found

to contain a detail of facts of an interesting character,

connected with the hardships, sufferings, and gallant

exploits of British soldiers in the various parts of the

world, where the calls of their Country and the commands

of their Sovereign have required them to

proceed in the execution of their duty, whether in[xix]

active continental operations, or in maintaining colonial

territories in distant and unfavourable climes.

The superiority of the British infantry has been

pre-eminently set forth in the wars of six centuries,

and admitted by the greatest commanders which

Europe has produced. The formations and movements

of this arme, as at present practised, while

they are adapted to every species of warfare, and to

all probable situations and circumstances of service,

are well suited to show forth the brilliancy of military

tactics calculated upon mathematical and scientific

principles. Although the movements and evolutions

have been copied from the continental armies, yet

various improvements have from time to time been

introduced, to ensure that simplicity and celerity by

which the superiority of the national military character

is maintained. The rank and influence which

Great Britain has attained among the nations of the

world have in a great measure been purchased by

the valour of the Army, and to persons who have the

welfare of their country at heart the records of the

several regiments cannot fail to prove interesting.

HISTORICAL RECORD

OF

THE THIRTY-FIRST,

OR,

THE HUNTINGDONSHIRE REGIMENT OF FOOT;

CONTAINING

AN ACCOUNT OF THE FORMATION OF THE REGIMENT

IN 1702,

AND OF ITS SUBSEQUENT SERVICES

TO 1850;

TO WHICH IS APPENDED,

An ACCOUNT of the SERVICES of the MARINE CORPS,

from 1664 to 1748;

The Thirtieth, Thirty-first, and Thirty-second Regiments having been

formed in 1702 as Marine Corps, and retained from 1714 on the Establishment

of the Army as Regiments of Regular Infantry.

COMPILED BY

RICHARD CANNON, Esq.

ADJUTANT GENERAL’S OFFICE, HORSE GUARDS

ILLUSTRATED WITH PLATES

LONDON:

PARKER, FURNIVALL, & PARKER,

30, CHARING CROSS.

1850.

THE THIRTY-FIRST

OR,

THE HUNTINGDONSHIRE REGIMENT OF FOOT,

BEARS ON THE REGIMENTAL COLOUR AND APPOINTMENTS

THE WORDS “TALAVERA,” “ALBUHERA,” “VITTORIA,”

“PYRENEES,” “NIVELLE,” “NIVE,” “ORTHES,”

AND “PENINSULA.”

IN COMMEMORATION OF THE SERVICES OF THE SECOND BATTALION

DURING THE “PENINSULAR WAR,” FROM 1809 TO 1814.

ALSO

THE WORD “CABOOL, 1842.”

FOR THE DISTINGUISHED CONDUCT OF THE REGIMENT DURING

THE SECOND CAMPAIGN IN AFFGHANISTAN

IN THE YEAR 1842;

AND THE WORDS

“MOODKEE,” “FEROZESHAH,” “ALIWAL,” AND

“SOBRAON,”

IN TESTIMONY OF ITS GALLANTRY IN THOSE BATTLES DURING THE

CAMPAIGN ON THE BANKS OF THE SUTLEJ,

FROM DECEMBER 1845, TO FEBRUARY 1846.

[xxvii]

THE

THIRTY-FIRST,

OR,

THE HUNTINGDONSHIRE REGIMENT OF FOOT.

CONTENTS

OF THE

HISTORICAL RECORD.

| Year |

|

Page |

| 1701 |

Introduction |

1 |

| 1702 |

Decease of King William III., and accession of Her Majesty Queen Anne |

2 |

| —— |

Certain Regiments of Marines raised |

— |

| —— |

Formation of the Thirty-first as a Regiment of Marines |

— |

| —— |

Colonel George Villiers appointed Colonel of the Regiment |

— |

| —— |

Names of the Officers |

3 |

| —— |

War of the Spanish Succession |

— |

| —— |

The Earl of Marlborough appointed to the command of the troops in Flanders |

— |

| —— |

Expedition to the coast of Spain under the Duke of Ormond |

4 |

| —— |

The Thirty-first and other regiments embarked for Cadiz |

— |

| —— |

Capture of the combined French and Spanish fleets at Vigo |

5 |

| —— |

The troops under the Duke of Ormond returned to England |

6 |

| 1703[xxviii] |

The Thirty-first Regiment stationed at Plymouth |

7 |

| —— |

Decease of Colonel Villiers |

— |

| —— |

Lieut.-Colonel Alexander Lutterell appointed Colonel of the Regiment |

— |

| 1704 |

Services of the Thirty-first Regiment on board the fleet under Admiral Sir George Rooke |

— |

| —— |

Unsuccessful attempt on Barcelona |

— |

| —— |

Capture of Gibraltar |

— |

| —— |

The Spanish and French armaments defeated in their attempts to retake Gibraltar |

8 |

| 1705 |

Operations against Barcelona |

— |

| —— |

Capture of Fort Montjuich |

— |

| —— |

The Prince of Hesse-Darmstadt killed |

— |

| —— |

Surrender of the Garrison of Barcelona |

— |

| 1706 |

Decease of Colonel Lutterell |

— |

| —— |

Lieut.-Colonel Josiah Churchill appointed Colonel of the Regiment |

— |

| —— |

Barcelona besieged by the French |

9 |

| —— |

Barcelona relieved by the English and Dutch fleet |

— |

| —— |

The allied fleet proceeded to the coast of Valencia |

— |

| —— |

Capture of Carthagena and Alicant |

— |

| —— |

Surrender of Iviça and Majorca |

— |

| 1707 |

Attack upon Toulon |

— |

| —— |

The siege of Toulon raised |

10 |

| 1708 |

Capture of Sardinia |

— |

| —— |

—— —— Minorca |

11 |

| 1709 |

Capture of Port Royal, in Nova Scotia |

— |

| —— |

The Fortress named Anna-polis Royal, in honor of Queen Anne |

12 |

| —— |

Alicant recovered by the enemy |

13 |

| 1710 |

The Isle of Cette taken by the British, and afterwards recaptured by the French |

— |

| 1711[xxix] |

Retirement of Colonel Churchill |

14 |

| —— |

Lieut.-Colonel Sir Harry Goring, Bart., promoted Colonel of the Regiment |

— |

| —— |

Charles III., the claimant to the Spanish throne, elected Emperor of Germany, and its effect upon the war |

— |

| 1712 |

Negociations for Peace |

— |

| 1713 |

Treaty of Utrecht |

— |

| —— |

Reductions in the Army and Navy |

15 |

| 1714 |

Decease of Queen Anne |

— |

| —— |

Accession of King George I. |

— |

| —— |

Augmentation of the Army, to counteract the designs of the Pretender |

— |

| —— |

The Thirtieth, Thirty-first, and Thirty-second Regiments,

which had been ordered to be disbanded, retained on the establishment, and incorporated with the regiments of the line |

— |

| —— |

Authorized to take rank in the Army from the date of original formation in 1702 |

— |

| 1715 |

Disaffection of the Earl of Mar |

16 |

| —— |

Rebellion in Scotland in favor of the Pretender |

— |

| —— |

Battle of Sheriffmuir |

— |

| —— |

Surrender of the Rebels at Preston |

— |

| —— |

Arrival in Scotland of the Pretender |

17 |

| 1716 |

His flight to France |

— |

| —— |

Suppression of the Rebellion |

18 |

| —— |

The Thirty-first embarked for Ireland |

— |

| —— |

Retirement of Colonel Sir Harry Goring |

— |

| —— |

Lord John Kerr appointed Colonel of the Regiment |

— |

| 1727 |

Decease of King George I. |

— |

| —— |

Accession of King George II. |

— |

| 1728 |

Decease of Major-General Lord John Kerr |

— |

| —— |

Colonel the Honorable Charles Cathcart appointed Colonel of the Regiment |

— |

| 1731[xxx] |

Colonel the Honorable Charles Cathcart removed to the Eighth Dragoons |

18 |

| —— |

Colonel William Hargrave appointed Colonel of the Thirty-first Regiment |

— |

| 1737 |

Colonel Hargrave removed to the Ninth Regiment |

— |

| —— |

Colonel William Handasyd appointed Colonel of the Thirty-first Regiment |

— |

| 1739 |

Removal of the Regiment from Ireland to Great Britain |

19 |

| —— |

Spanish depredations in America |

— |

| —— |

War declared against Spain |

— |

| 1740 |

War of the Austrian Succession |

— |

| 1741 |

The Regiment encamped at Windsor and on Lexden Heath |

21 |

| 1742 |

Embarked for Flanders as Auxiliaries |

— |

| 1743 |

Marched towards the Rhine |

22 |

| —— |

Battle of Dettingen |

23 |

| —— |

The Battle compared with other victories |

24 |

| 1744 |

Declaration of War against France |

25 |

| 1745 |

Decease of Colonel Handasyd |

— |

| —— |

Colonel Lord Henry Beauclerk appointed Colonel of the Regiment |

— |

| —— |

Investment of Tournay by Marshal Saxe |

— |

| —— |

Battle of Fontenoy |

26 |

| —— |

Surrender of Tournay to the French |

27 |

| —— |

Skirmish at La Mésle, near Ghent |

28 |

| —— |

Rebellion in Scotland, headed by Prince Charles Edward |

— |

| —— |

Return of the Thirty-first and other Regiments to England |

— |

| —— |

The Regiment stationed in the vicinity of London |

29 |

| 1746 |

Battle of Culloden |

— |

| —— |

Escape of Prince Charles Edward to France |

— |

| 1747[xxxi] |

Battle of Laffeld, or Val |

29 |

| 1748 |

Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle |

— |

| 1749 |

Retirement of Colonel Lord Henry Beauclerk |

30 |

| —— |

Colonel Henry Holmes appointed Colonel of the Regiment |

— |

| —— |

The Regiment embarked for Minorca |

30 |

| 1751 |

Regulations prescribed by Royal Warrant for establishing uniformity in the clothing,

standards, and colours of regiments, &c. |

— |

| 1752 |

The Regiment returned from Minorca to England |

— |

| 1755 |

Proceeded to Scotland |

— |

| 1756 |

The Seven Years’ War |

— |

| —— |

War declared against France |

30 |

| —— |

Capture of Minorca by the French |

31 |

| —— |

Augmentations in the Army and Navy |

— |

| —— |

The Second Battalion of the Thirty-first constituted the Seventieth Regiment |

— |

| 1759 |

Summary of the occurrences of the War |

— |

| 1762 |

War declared against Spain |

32 |

| —— |

Capture of Martinique, Grenada, St. Vincent, and other West India Islands, by the British |

— |

| —— |

Peace of Fontainebleau |

— |

| —— |

The Regiment removed from Scotland to England |

— |

| —— |

Decease of Lieut.-General Holmes |

— |

| —— |

Colonel James Adolphus Oughton appointed Colonel of the Regiment |

— |

| 1765 |

The Regiment embarked for Florida |

33 |

| —— |

Suffered severely from yellow fever |

— |

| 1772 |

Embarked for St. Vincent |

34 |

| —— |

Engaged in reducing the Caribs |

— |

| 1774 |

Termination of the Carib War |

35 |

| —— |

The Regiment returned to England |

— |

| 1775 |

Stationed in North Britain |

— |

| 1775[xxxii] |

War of American Independence |

35 |

| 1776 |

The Regiment embarked for Canada with the |

| —— |

Troops under Major-General Burgoyne |

— |

| —— |

Defence of Quebec against the American Army |

— |

| —— |

Defence of the British Post at Trois Rivières |

— |

| —— |

Declaration of Independence by the American Congress |

36 |

| —— |

Operations on Lake Champlain |

— |

| 1777 |

The flank companies of the Thirty-first and other regiments proceed on an expedition under Major-General Burgoyne |

37 |

| —— |

Capture of Ticonderago |

— |

| —— |

Action at Skenesborough |

— |

| —— |

Action near Castleton |

— |

| —— |

Pursuit of the Americans to Fort Anne and Fort Edward |

38 |

| —— |

Action at Stillwater |

39 |

| —— |

Lieut.-General Burgoyne is compelled to capitulate to General Gates |

40 |

| —— |

Convention of Saratoga |

— |

| 1778 |

Aid rendered by France to the Americans |

41 |

| 1780 |

Decease of Lieut.-General Sir James Oughton |

— |

| —— |

Major-General Thomas Clarke appointed Colonel of the Regiment |

— |

| 1781 |

The battalion companies, which remained in Canada, joined by the flank companies |

— |

| —— |

The light company engaged in effecting the destruction of military stores at Ticonderago |

— |

| 1782 |

The Independence of the United States acknowledged by King George III. |

42 |

| —— |

The Thirty-first styled the Huntingdonshire Regiment |

— |

| 1783 |

Treaty of Peace between England, France, and Spain |

43 |

| —— |

Peace concluded with Holland |

— |

| 1787[xxxiii] |

The Regiment embarked at Quebec for England |

43 |

| —— |

Stationed in Great Britain |

— |

| 1789 |

Commencement of the French Revolution |

— |

| —— |

Preparations for War with Spain |

44 |

| 1790 |

The Thirty-first embarked on board the fleet to perform its original service of Marines |

— |

| —— |

Convention with Spain |

— |

| 1791 |

Disturbances in the Manufacturing Districts |

45 |

| 1792 |

Lieut.-General Thomas Clarke removed to the Thirtieth Regiment |

— |

| —— |

Major-General James Stuart appointed Colonel of the Regiment |

— |

| —— |

The Regiment embarked for Ireland |

— |

| 1793 |

Decease of Major-General Stuart |

— |

| —— |

Colonel Lord Mulgrave appointed Colonel of the Regiment |

— |

| —— |

Progress of events in France |

— |

| —— |

War with France |

— |

| —— |

The flank companies embarked for Barbadoes |

— |

| 1794 |

Capture of Martinique, St. Lucia, and Guadaloupe |

46 |

| —— |

A French Armament sent to retake Guadaloupe |

47 |

| —— |

Gallant defence of Guadaloupe by the British |

— |

| —— |

The Garrison of Berville Camp surrendered to the French |

— |

| —— |

Return of the Troops at Guadaloupe |

48 |

| —— |

Evacuation of Fort Matilda by the British |

49 |

| —— |

The Regiment proceeded from Ireland to England |

— |

| —— |

Embarked for Holland |

— |

| 1795 |

Returned to England |

— |

| —— |

Joined the Camp formed at Nursling, near Southampton |

— |

| —— |

Embarked for the West Indies |

— |

| —— |

Delayed by storms and contrary winds |

50 |

| 1796[xxxiv] |

Disembarked at Gosport |

51 |

| —— |

Embarked for St. Lucia |

— |

| —— |

Engaged in the capture of that Island |

52 |

| —— |

Employed against the Caribs in St. Lucia |

53 |

| 1797 |

Returned to England |

54 |

| 1799 |

Augmented by volunteers from the Militia |

55 |

| —— |

Embarked for Holland, as part of the Army under the Duke of York |

56 |

| —— |

Engaged in the Action at Alkmaar |

— |

| —— |

Attack on the French position between Bergen and Egmont-op-Zee |

58 |

| —— |

Occupation of Alkmaar by the British Troops |

59 |

| —— |

Action near Alkmaar |

— |

| —— |

Withdrawal of the British Troops from Holland |

60 |

| —— |

Regiment arrived in England |

— |

| 1800 |

Embarked for Ireland |

— |

| —— |

Expedition to the coast of France under Brigadier the Honorable Sir Thomas Maitland |

— |

| —— |

Joined the expedition under Lieut.-General Sir James Pulteney destined for the coast of Spain |

— |

| —— |

Landed at Ferrol |

— |

| —— |

Sailed to Vigo |

61 |

| —— |

Proceeded to Cadiz |

— |

| —— |

Embarked for Gibraltar |

— |

| —— |

Expedition to Egypt |

— |

| 1801 |

The Thirty-first proceeded to Lisbon, and subsequently to Minorca |

— |

| 1802 |

Deliverance of Egypt from the French Troops |

62 |

| —— |

Peace of Amiens |

— |

| —— |

The Regiment embarked at Minorca for England |

— |

| 1803 |

Removed to Jersey |

— |

| —— |

Gallant conduct of a Private Soldier of the Thirty-first Regiment |

— |

| 1803[xxxv] |

Renewal of the War with France |

63 |

| —— |

Preparations for the defence of England from the menace of French Invasion |

— |

| 1804 |

A second battalion added to the Regiment |

64 |

| —— |

The Regiment embarked for England |

— |

| —— |

War declared by Spain against Great Britain |

— |

| 1805 |

The second battalion proceeded from Chester, and joined the first battalion at Winchester |

— |

| 1806 |

Employed on the occasion of the Funeral of Admiral Viscount Nelson |

65 |

| —— |

The first battalion embarked for Sicily |

— |

| 1807 |

Proceeded on the Expedition to Egypt under Major-General Fraser |

66 |

| —— |

Attacked by the Turks at Rosetta |

67 |

| —— |

Egypt evacuated by the British |

68 |

| —— |

Return of the troops to Sicily |

— |

| 1808 |

The first battalion embarked for Malta |

— |

| 1810 |

Returned to Sicily |

— |

| 1811 |

Proceeded to Malta |

69 |

| —— |

Returned to Sicily |

— |

| 1812 |

The grenadier company embarked for the east coast of Spain |

— |

| 1813 |

Returned to Sicily |

— |

| 1814 |

The first battalion proceeded on an expedition to Italy |

70 |

| —— |

Disembarked at Leghorn |

— |

| —— |

Actions at Sestri and Recco |

— |

| —— |

Action at La Sturla, on the heights of Albaro |

71 |

| —— |

Gallantry of the first battalion |

72 |

| —— |

Occupation of Genoa |

73 |

| —— |

The first battalion embarked for Corsica |

— |

| —— |

Returned to Sicily |

74 |

| —— |

Treaty of Peace with France |

— |

| —— |

The second battalion disbanded |

— |

| —— |

Honorary Distinctions acquired by the Regiment |

— |

| 1815[xxxvi] |

Return of Napoleon Bonaparte to France, and Renewal of the War |

75 |

| —— |

The Regiment embarked for Naples |

— |

| —— |

Battle of Waterloo |

76 |

| —— |

Termination of the War |

— |

| —— |

The Regiment embarked for Genoa |

— |

| 1816 |

Embarked for Malta |

— |

| 1818 |

Returned to England |

— |

| 1819 |

Disturbed state of the Manufacturing Districts |

— |

| —— |

The Thanks of the Sovereign and of the Magistrates conveyed to the Thirty-first and other Corps employed at Manchester |

77 |

| 1821 |

The Regiment embarked for Ireland |

78 |

| 1824 |

Returned to England |

79 |

| 1825 |

Embarked for Calcutta |

— |

| —— |

Destruction of the “Kent” East Indiaman by fire in the Bay of Biscay |

80 |

| —— |

Gallant conduct of the right wing, embarked in the “Kent” during the conflagration |

81 |

| —— |

Names of the Officers, and the number of the men, women, and children, saved by the ships “Cambria” and “Caroline” |

82 |

| —— |

Letter from the Adjutant-General to Lieut.-Colonel Fearon, commanding the Thirty-first,

expressive of the Commander-in-Chief’s approbation of the courage and discipline displayed by the right wing of the regiment

during the burning of the “Kent” |

88 |

| —— |

Further particulars relating to this calamity |

89 |

| —— |

Part of the right wing re-embarked for India |

92 |

| —— |

Joined the left wing at Berhampore |

— |

| 1826 |

Another detachment embarked for India |

93 |

| —— |

The Regiment marched to Meerut |

94 |

| —— |

Presentation of New Colours to the Regiment by Lady Amherst |

95 |

| 1831[xxxvii] |

Marched to Kurna |

96 |

| —— |

Decease of General the Earl of Mulgrave |

97 |

| —— |

General Sir Henry Warde, G.C.B., appointed Colonel of the Regiment |

— |

| —— |

Interview between the Governor-General of India, Lord William Bentinck, and Runjeet Singh, the Sovereign of the Punjaub |

98 |

| —— |

The Regiment formed part of the Governor-General’s Escort |

— |

| —— |

Detail of the Proceedings on the Sutlej |

99 |

| —— |

The Regiment returned to Kurnaul |

| 1834 |

Decease of General Sir Henry Warde |

100 |

| —— |

Lieut.-General Sir Edward Barnes, G.C.B., appointed Colonel of the Regiment |

— |

| 1836 |

The Regiment marched to Dinapore |

— |

| 1838 |

Decease of General Sir Edward Barnes |

101 |

| —— |

Lieut.-General Sir Colin Halkett, K.C.B., appointed Colonel of the Regiment |

— |

| —— |

The Regiment marched to Ghazeepore |

— |

| 1840 |

Marched to Agra |

102 |

| 1841 |

Insurrection at Cabool |

103 |

| 1842 |

The Regiment marched to Peshawur to join the army under Major-General Pollock, destined to proceed to Cabool |

— |

| —— |

Arrival of the army at Jellalabad |

104 |

| —— |

The Regiment marched to Peshbolak to attack the Shinwarees |

105 |

| —— |

Action at Mazeena |

107 |

| —— |

Passage of the Jugdulluck Pass |

109 |

| —— |

Action at Tezeen |

110 |

| —— |

Advance on Cabool |

112 |

| —— |

Occupation of the Bala Hissar |

113 |

| —— |

Release of the Officers, Ladies, and Soldiers, taken prisoners by the Affghans, at the commencement of the insurrection |

— |

| 1842[xxxviii] |

Return of the Army to India |

113 |

| —— |

Action at the Jugdulluck Pass |

114 |

| —— |

Skirmishes in the Passes between Tezeen and Gundamuck |

— |

| —— |

Arrival of the troops at Jellalabad |

115 |

| —— |

Marched to Peshawur |

— |

| —— |

Honors rendered to the troops on arrival at Ferozepore |

— |

| —— |

Authorized to bear the word “Cabool, 1842,” on the Regimental Colour and Appointments |

— |

| —— |

The Regiment marched to Umballa |

— |

| —— |

Expedition to Khytul |

116 |

| —— |

Outbreak at Lahore |

— |

| 1843 |

The Regiment marched to Ferozepore |

— |

| 1844 |

Returned to Umballa |

117 |

| 1845 |

Disturbed state of the Punjaub |

— |

| —— |

Sikh invasion of the British Territories in India |

118 |

| —— |

The Regiment marched from Umballa to join the Ferozepore Field force |

119 |

| —— |

Battle of Moodkee |

120 |

| —— |

—— —— Ferozeshah |

126 |

| 1846 |

The Regiment marched towards Loodiana with the troops under Major-General Sir Henry Smith |

136 |

| —— |

The Fort of Dhurrumkote captured from the Sikhs |

137 |

| —— |

Action at Buddiwal |

— |

| —— |

Battle of Aliwal |

138 |

| —— |

Return of the troops under Major-General Sir Henry Smith to the head-quarters of the Army |

145 |

| —— |

Battle of Sobraon |

— |

| —— |

Advance of the Army on Lahore |

156 |

| —— |

Occupation of the City |

158 |

| 1846[xxxix] |

Orders received for the Regiment to return to Europe |

159 |

| —— |

Embarked for Calcutta |

163 |

| —— |

Review of the Punjaub Campaign |

165 |

| —— |

Honors conferred on the “Army of the Sutlej” |

167 |

| —— |

General Lord Gough’s farewell order to the Regiment |

172 |

| —— |

Embarked for England |

174 |

| —— |

Reception on arrival |

175 |

| —— |

Letter to Lieut.-Colonel Spence, from General Sir Colin Halkett, reviewing the services of the Regiment |

177 |

| —— |

Stationed at Walmer |

182 |

| 1847 |

Authorized to bear on the Regimental Colour and Appointments the words

“Moodkee,” “Ferozeshah,” “Aliwal,” and “Sobraon” |

183 |

| —— |

General Sir Colin Halkett G.C.B., removed to the forty-fifth Regiment |

— |

| —— |

Lieut.-General the Honorable Henry Otway Trevor appointed Colonel of the Thirty-first Regiment |

— |

| —— |

The Regiment removed to Manchester |

— |

| 1848 |

Embarked for Ireland |

— |

| —— |

Presentation of New Colours by Major-General His Royal Highness the Prince George of Cambridge |

184 |

| 1849 |

Stationed at Athlone |

186 |

| 1850 |

Removed to Dublin |

— |

| —— |

Presentation of a Testimonial to Lieut.-Colonel Spence on his retirement |

— |

| —— |

Conclusion |

— |

[xl]

CONTENTS

OF

THE HISTORICAL RECORD

OF

THE SECOND BATTALION

OF

THE THIRTY-FIRST REGIMENT.

| Year |

|

Page |

| 1804 |

Projected French invasion of England |

187 |

| 1805 |

Formation of the Second Battalion of the Thirty-first Regiment at Chester |

— |

| —— |

Marched from Chester to Winchester |

— |

| 1806 |

Proceeded to Gosport |

188 |

| 1807 |

Embarked for Guernsey |

— |

| —— |

Proceeded to Ireland |

— |

| 1808 |

Joined the force assembled at Falmouth under the command of Lieut.-General Sir David Baird |

— |

| —— |

Sailed for Portugal |

189 |

| —— |

Marched to reinforce the army in Spain under Lieut.-General Sir John Moore |

— |

| 1809 |

The intended advance countermanded |

— |

| —— |

Battle of Corunna |

190 |

| —— |

Arrival of Lieut.-General Sir Arthur Wellesley at Lisbon, and his appointment to the command of the army in the Peninsula |

— |

| —— |

The second battalion of the Thirty-first marched towards Oporto |

191 |

| —— |

Passage of the Douro |

— |

| 1809[xli] |

Arrived at Oropesa |

191 |

| —— |

Battle of Talavera |

192 |

| —— |

Authorized to bear the word “Talavera” on the Regimental Colour and Appointments |

193 |

| —— |

Stationed at Abrantes |

194 |

| 1810 |

Marched to Portalegre |

— |

| —— |

Encamped between the Estrella and the Tagus |

195 |

| —— |

Battle of Busaco |

— |

| —— |

Marched on Thomar |

— |

| —— |

Skirmishes near Alhandra |

196 |

| 1811 |

Pursuit of Marshal Massena |

— |

| —— |

Siege of Olivenza and Badajoz |

— |

| —— |

Battle of Albuhera |

197 |

| —— |

Authorized to bear the word “Albuhera” on the Regimental Colour and Appointments |

199 |

| —— |

Second siege of Badajoz |

— |

| —— |

Affair at Arroyo dos Molinos |

200 |

| —— |

Stationed at Merida |

— |

| 1812 |

Siege of Ciudad Rodrigo |

— |

| —— |

Third siege of Badajoz |

— |

| —— |

Capture of Badajoz |

201 |

| —— |

Attack on the French works at Almaraz |

— |

| —— |

Operations against General Drouet |

202 |

| —— |

Siege of the Castle of Burgos |

203 |

| —— |

Lieut.-General Sir Rowland Hill’s division, of which the

second battalion of the Thirty-first formed part, cantoned at Coria and Placentia |

204 |

| 1813 |

Advance upon Burgos and Vittoria |

— |

| —— |

Battle of Vittoria |

— |

| —— |

Authorized to bear the word “Vittoria” on the Regimental Colour and Appointments |

205 |

| —— |

Siege of Pampeluna |

206 |

| —— |

The French dislodged from the valley of Bastan |

— |

| —— |

Action in the Pass of Roncesvalles |

— |

| 1813[xlii] |

Engaged on the heights at Pampeluna |

206 |

| —— |

Authorized to bear the word “Pyrenees” on the Regimental Colour and Appointments |

207 |

| —— |

Capture of a French convoy at Elizondo |

— |

| —— |

Capture of St. Sebastian and Pampeluna |

— |

| —— |

March of the Allied Army to the French side of the Pyrenees |

—- |

| —— |

Engaged in the Pass of Maya |

— |

| —— |

Passage of the Nivelle |

— |

| —— |

Authorized to bear the word “Nivelle” on the Regimental Colour and Appointments |

208 |

| —— |

Passage of the Nive |

— |

| —— |

Action at St. Pierre, near Bayonne |

209 |

| —— |

Authorized to bear the word “Nive” on the Regimental Colour and Appointments |

210 |

| 1814 |

Action on the heights of Garris |

— |

| —— |

Battle of Orthes |

211 |

| —— |

Authorized to bear the word “Orthes” on the Regimental Colour and Appointments |

— |

| —— |

Action at Aire |

— |

| —— |

Battle of Toulouse |

— |

| —— |

Sortie from Bayonne |

212 |

| —— |

Termination of the Peninsular War |

— |

| —— |

The second battalion of the Thirty-first Regiment marched to Bourdeaux |

— |

| —— |

Embarked for Ireland |

— |

| —— |

Authorized to bear the word “Peninsula” on the Regimental Colour and Appointments |

— |

| —— |

Proceeded to Portsmouth |

213 |

| —— |

Disbanded |

— |

[xliii]

SUCCESSION OF COLONELS

OF

THE THIRTY-FIRST REGIMENT.

|

|

Page |

| 1702 |

George Villiers |

215 |

| 1703 |

Alexander Lutterell |

— |

| 1706 |

Josiah Churchill |

— |

| 1711 |

Sir Harry Goring, Bart. |

216 |

| 1716 |

Lord John Kerr |

— |

| 1728 |

The Honorable Charles Cathcart |

— |

| 1731 |

William Hargrave |

217 |

| 1737 |

William Handasyd |

— |

| 1745 |

Lord Henry Beauclerk |

218 |

| 1749 |

Henry Holmes |

— |

| 1762 |

Sir James Adolphus Oughton |

— |

| 1780 |

Thomas Clarke |

— |

| 1792 |

James Stuart |

219 |

| 1793 |

Henry, Earl of Mulgrave, G.C.B. |

— |

| 1831 |

Sir Henry Warde, G.C.B. |

220 |

| 1834 |

Sir Edward Barnes, G.C.B. |

221 |

| 1838 |

Sir Colin Halkett, G.C.B. |

222 |

| 1847 |

Honorable Henry Otway Trevor, C.B. |

— |

|

Page |

| List of Battles, Sieges, &c., in Germany and the Netherlands, from 1743 to 1748, during the “War of the Austrian Succession” |

223 |

| List of British Regiments which served in Flanders and Germany, between the years 1742 and 1748, during the “War of the Austrian Succession” |

224 |

| Memoir of the services of Colonel Bolton, C.B. |

225 |

| Memoir of the services of Lieut.-Colonel Skinner, C.B. |

226 |

| Memoir of the services of Major Baldwin |

230 |

PLATES.

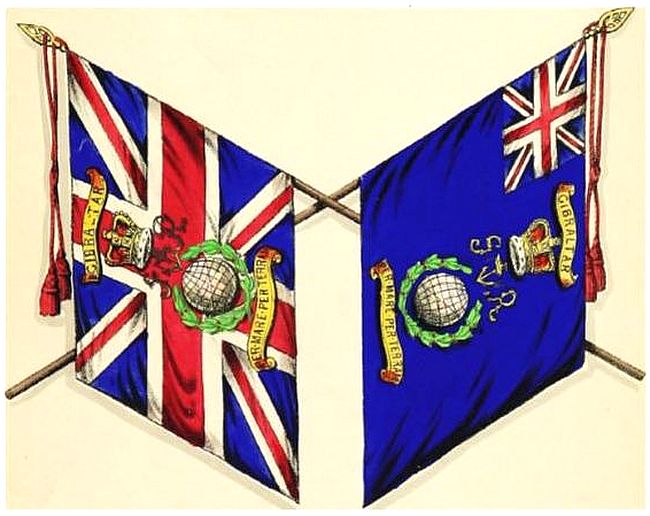

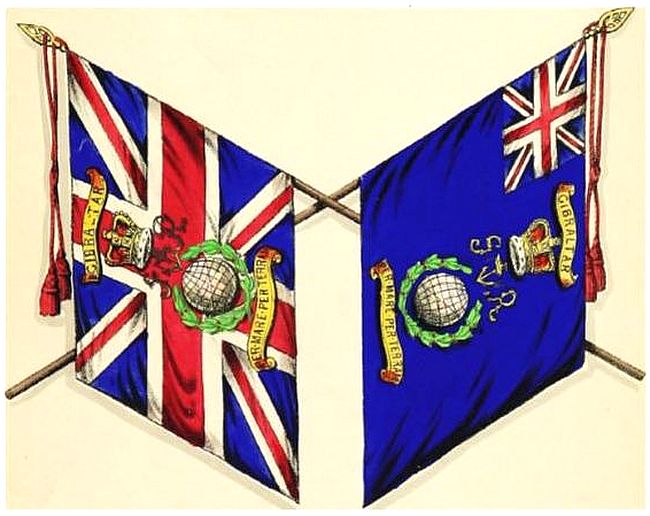

| Present Colours of the Regiment |

to face page |

1 |

| Wreck of the Kent East India Ship |

80 |

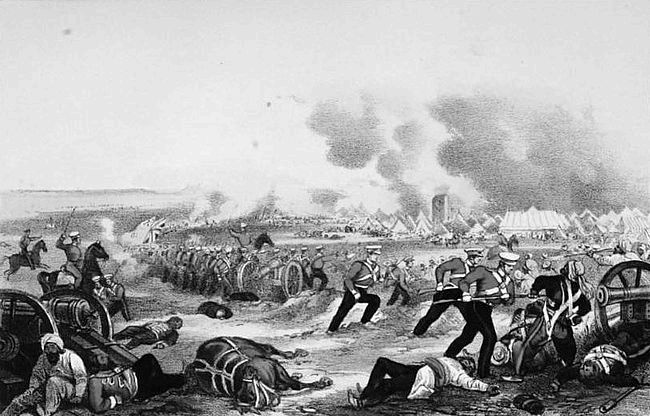

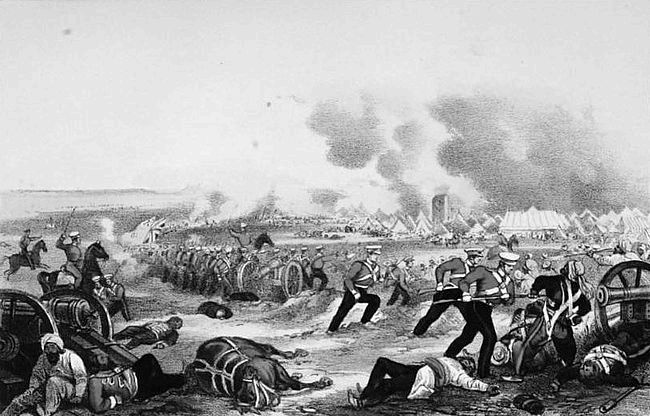

| Battle of Ferozeshah |

128 |

| Battle of Sobraon |

152 |

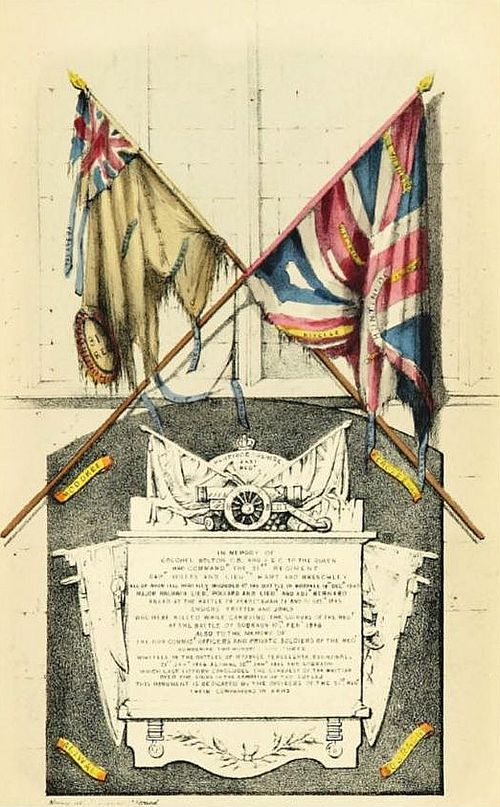

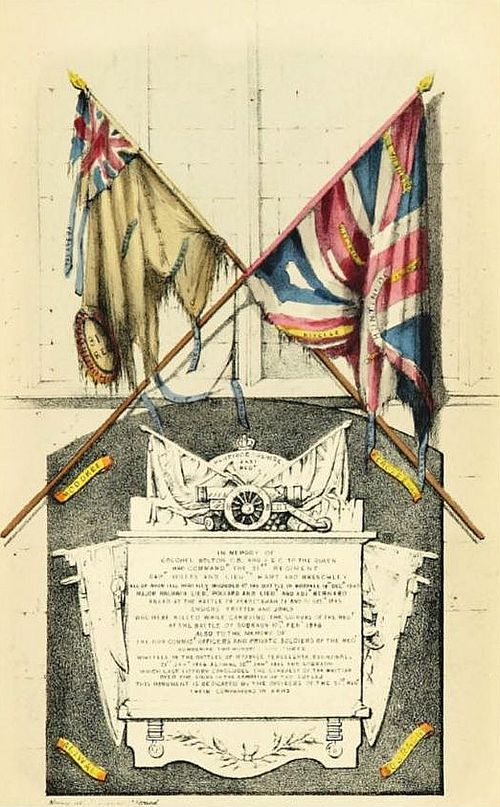

| Monument erected in Canterbury Cathedral, to the memory of the Officers and Soldiers of the Thirty-first Regiment, who were killed during the campaign on the banks of the Sutlej from December 1845 to February 1846 |

214 |

THIRTY-FIRST REGIMENT.

QUEEN’S COLOUR.

REGIMENTAL COLOUR.

FOR CANNON’S MILITARY RECORDS,

Madeley lith. 3 Wellington St Strand.

[Pg 1]

HISTORICAL RECORD

OF

THE THIRTY-FIRST, OR THE HUNTINGDONSHIRE,

REGIMENT OF FOOT.

1701

In the commencement of the eighteenth century,

the British Monarch, King William III., found that

the conditions of the Treaty of Ryswick, concluded in

1697, were violated by the King of France, Louis

XIV., who, on the decease of Charles II. of Spain on

the 1st of November, 1700, pursued with unremitting

assiduity his ambitious project of ultimately uniting

the crowns of France and Spain, by procuring the

accession of his grandson, Philip, Duke of Anjou, to

the vacant throne; thus excluding the claims of the

House of Austria, and disregarding the existing treaties

between the principal nations of Europe. The

seizure of the Spanish Netherlands by the troops of

France,—the detention of the Dutch garrisons in

the barrier towns,—the declaration of Louis XIV.

in favour of the family of James II., and other acts of

hostility, justified the British Government in making

preparations for war.

King William had determined on active measures,

by sea and land, against the powers of France and[2]

Spain, and had accordingly directed augmentations to

be made in the navy and army. A division of the

army had been appointed, under the command of

Brigadier-General Ingoldsby, (twenty-third regiment,)

to embark for Flanders, and another portion of the

army was selected to embark for the coast of Spain,

under the orders of the Duke of Ormond.

1702

The death of King William III. took place on the

8th of March, 1702. His policy was adopted by his successor

Queen Anne, who entered into treaties of alliance

with the Emperor of Germany,—the States-General of

the United Provinces,—and other Princes and Potentates,

for preserving the liberty and balance of power

in Europe, and for defeating the ambitious views of

France.

The measures for increasing the efficiency of the

fleet had occasioned the suggestion of raising Corps of

Marines, capable of acting on land as well as at sea.

Several regiments of the regular army were appointed

to serve as Marines, and six additional regiments

were especially raised for that service.[6]

On the 14th of March, 1702, a Royal Warrant was

issued, authorising Colonel George Villiers to

raise a Regiment of Marines, which was to consist of

twelve companies, of two serjeants, three corporals,

two drummers, and fifty-nine private soldiers each,

with an additional serjeant to the grenadier company.[3]

The rendezvous of the regiment was appointed to be

at Taunton and Bridgewater.

For the raising of this regiment the following officers

received commissions, those of the field officers being

antedated to the 12th of February, 1702:—

| Captains |

George Villiers (Colonel). |

|

Alexander Lutterell (Lt.-Colonel). |

|

Thomas Carew (Major). |

|

Francis Blinman. |

|

George Blakeney. |

| Captain-Lieutenant |

John Deveroux. |

| First Lieutenants |

Saloman Balmier. |

|

Roger Flower. |

| Second Lieutenant |

William Bisset. |

| Chirurgeon |

James Church. |

| Chirurgeon’s mate |

William Church. |

The declaration of hostilities against France and

Spain was issued on the 4th of May, 1702: thus began,

“fruitful in great actions and important results,” The

War of the Spanish Succession.

Additional forces were sent to Flanders, and the

Earl of Marlborough was appointed to command the

confederate troops with the rank of Captain-General.

The expedition, which had been planned by King

William against Spain, was carried out by the Ministers

of Queen Anne. It was arranged, accordingly,

that a combined fleet of English and Dutch ships,

consisting of fifty sail of the line, besides frigates,

under Admiral Sir George Rooke, and a land force

amounting to nearly fourteen thousand men, under

the command of the Duke of Ormond, should proceed[4]

to the coast of Spain. The following corps were

employed on this service, namely:—

|

|

|

Officers

and Men. |

|

| Lloyd’s Dragoons, now 3rd Light Dragoons (detachment.) |

275 |

| Foot Guards, the Grenadier and Coldstream |

755 |

| Sir H. Bellasis’s |

now 2nd |

Foot |

834 |

| Churchill’s |

3rd |

” |

834 |

| Seymour’s |

4th |

” |

834 |

| Columbine’s |

6th |

” |

724 |

| O’Hara’s, 3 companies |

7th |

Royal Fusiliers |

313 |

| Erle’s |

19th |

Foot |

724 |

| Gustavus Hamilton’s |

20th |

” |

724 |

| Villiers’s Marines, 5 Companies. |

31st |

” |

520 |

| Fox’s Marines |

32nd |

” |

834 |

| Donegal’s |

35th |

” |

724 |

| Charlemont’s |

36th |

” |

724 |

| Shannon’s Marines |

|

|

834 |

|

|

|

—— |

|

|

|

9653 |

Dutch Regiments commanded by Major-General Baron

Sparre and Brigadier Pallandt |

} 3924 |

|

|

|

——— |

|

|

|

13,577 |

Colonel Villiers’s Corps of Marines, now the THIRTY-FIRST

regiment, soon after its formation was thus

called upon to supply five Companies for embarkation

for active service on board the fleet destined

against Spain: these Companies embarked in the

latter part of May from Plymouth, and proceeded to

join the fleet at Portsmouth, from whence the expedition

sailed to Cadiz in the month of July, 1702.

The armament appeared off Cadiz on the 12th of

August, and the Duke summoned the place; but his

terms being refused, he landed on the 15th at the Bay

of Bulls, between Rota and Fort St. Catherine, under

great disadvantages and a well conducted opposition:

he marched upon Rota, where the horses and stores

were disembarked, and in two days afterwards he advanced[5]

to the town of St. Mary. Rota was retaken

by a coup-de-main, and the British garrison of 300

men was captured. The attempt on Cadiz failed; the

troops were re-embarked, and sailed from Cadiz on the

30th of September.

In alluding to this expedition, Bishop Burnet remarks,—“It

is certain our Court had false accounts of

the state the place was in, both with relation to the

garrison, and to the fortifications; the garrison was

much stronger, and the fortifications were in a better

state, than was represented.”

Conspicuous as the bravery of the troops had been in

the expedition against Cadiz, still the failure of the

attempt naturally caused painful feelings to arise

among the British soldiers, who were disappointed of

reaping the well-earned fame of a successful enterprise,

when victory appeared almost within their grasp. The

receipt of information of the arrival of a Spanish fleet

from the West Indies, under a French convoy, at the

harbour of Vigo, speedily dissipated these feelings, and

gave renewed hopes to the troops. The allied fleet

immediately bent its course thither, and arrived before

Vigo on the 22nd of October, 1702. The French admiral

Count de Chateaurenaud had placed his shipping and

the galleons within a narrow passage, the entrance

to which was defended by a castle on one side, and

by platforms mounted with cannon on both sides of

the inlet; a strong boom was thrown across the harbour.

To facilitate the attack on this formidable barrier,

the Duke of Ormond landed a portion of his army six

miles from Vigo on the 23rd of October, and took, by

assault, a battery of forty pieces of cannon, situated at[6]

the entrance of the bay. A British flag, hoisted on this

fort, was the signal for a general attack. The fleet in full

sail approached, broke the boom at the first shock, and

became closely engaged with the enemy’s ships, while

the British troops that had landed, stormed and captured

the batteries. After a vigorous defence, the French

and Spaniards, finding they could not escape, set fire to

some of their vessels, and cast their cargoes into the sea;

but the British exerted themselves nobly in extinguishing

the flames, and succeeded in saving six galleons

and seven ships of war. Two thousand of the enemy

are stated to have perished, and the Spaniards sustained

a loss in goods and treasure exceeding eight

million dollars, more than one-half of which fell to the

captors, whose loss in this victory was inconsiderable.

Queen Anne, attended by the Lords and Commons,

went in state to St. Paul’s Cathedral to return thanks

for this success, and each of the regiments of infantry

received 561l. 10s. prize-money.

Villiers’s Marines (THIRTY-FIRST regiment) did not

land at Vigo, but served on board the fleet in this gallant

enterprise.

The troops under the Duke of Ormond subsequently

returned to England, and on their arrival in November,

1702, were stationed as follows, namely:—

| Lloyd’s 3rd Dragoons (detachment) |

Portsmouth. |

| Foot Guards, 1st and Coldstream |

Gravesend and Chatham. |

| Sir H. Bellasis’s |

2nd Foot |

Portsmouth. |

| Churchill’s |

3rd ” |

Chatham. |

| Seymour’s |

4th ” |

Plymouth. |

| Columbine’s |

6th ” |

Portsmouth. |

| Royal Fusiliers |

7th ” |

Tilbury. |

| Villiers’s (Marines) Thirty-first |

Plymouth. |

| Fox’s Marines |

32nd Foot |

Plymouth. |

| Viscount Shannon’s Marines |

Chatham. |

[7]

1703

On the 6th of January, 1703, seven companies of the

regiment were stationed at Plymouth, and on the 27th

of that month four companies were ordered for embarkation

on board of the ships Suffolk and Grafton,

which proceeded on service to the coast of Spain, to

join the fleet under Admiral Sir George Rooke, and continued

in that quarter, and in the Mediterranean, during

that year.

In December, 1703, Colonel Villiers, who was in

command of the Regiment on board of the fleet, was

drowned. He was succeeded in the Colonelcy of the

Regiment by Lieut.-Colonel Alexander Lutterell, on

the 6th of December of that year.

1704

The THIRTY-FIRST regiment, being at this time a

Marine Corps, continued to serve on board the fleet in

the Mediterranean, and in February, 1704, proceeded,

under Admiral Sir George Rooke, to Lisbon, from

whence it proceeded to Barcelona, where the troops were

landed under the command of Major-General the

Prince of Hesse-Darmstadt, on the 19th of May; but

the force, being inadequate for the purpose intended,

was re-embarked on the day following.

The fleet next proceeded to attack the fortress of

Gibraltar, and the Prince of Hesse effected a landing

on the afternoon of the 21st of July, 1704, with eighteen

hundred British and Dutch Marines: after a

bombardment of three days, the governor was forced

to capitulate, and the Prince of Hesse took possession

of the garrison on the evening of Sunday, the 24th of

July, 1704. The attack of the seamen and marines is

recorded in history to have been one of the boldest and

most difficult ever performed. The fortress of Gibraltar

was thus taken, and was besieged by the Spaniards[8]

and French in October following, for seven months,

during which period it was successfully defended by

the navy and marines, and has since remained, as a

monument of British valour, in possession of the

Crown of Great Britain.

After selecting a sufficient force to garrison Gibraltar,

the Marine Corps were distributed in the several ships

of war which were then collected in the Tagus, in order

to co-operate with the land forces on the coast of Spain.

1705

Towards the end of May, 1705, the British fleet having

about five thousand troops on board, with General

the Earl of Peterborough, proceeded to Lisbon; King

Charles embarked on board of the Ranelagh on the

23rd of July, and the Dutch fleet having joined in the

Tagus, proceeded from thence, and anchored before

Barcelona on the 22nd of August.

The Earl of Peterborough commenced operations

against Barcelona by an attack on the strong fortress

of Montjuich, which was taken by storm on the 17th

of September. In this attack the Prince of Hesse

Darmstadt was wounded by a musket-ball which occasioned

his death. The city of Barcelona was invested,

and after considerable efforts on the part of the besiegers

and the besieged, the garrison surrendered on

the 6th of October, 1705.

The capture of Barcelona obtained for the allied

forces the applause of the nations of Europe, and in

a great degree promoted the cause of King Charles

in his efforts to succeed to the Crown of Spain.

1706

The decease of Colonel Lutterell having taken place,

he was succeeded by Lieut.-Colonel Josiah Churchill,

on the 1st of February, 1706.

The neglect of King Charles III. and his counsellors[9]

to secure the advantages obtained by the conquests

before stated, and the persevering efforts made in

favour of King Philip V. by the French, and by those

persons in other countries who supported his cause,

occasioned great difficulties, as well as serious losses to

the allied forces.

A powerful French and Spanish force by land, aided

by a fleet, attempted the recapture of Barcelona, which

was besieged in the beginning of April, 1706; but

when the enemy had made preparations to attack the

place by storm, the English and Dutch fleet arrived

with reinforcements for the garrison;—the French relaxed

in their efforts, and the siege was raised on the

11th of May.

The city of Barcelona was thus relieved, and the

allied fleet, with the troops on board, proceeded to the

coast of Valencia; after capturing Carthagena, and

placing six hundred Marines for its defence, the expedition

proceeded to an attack upon Alicant, which,

after a gallant resistance and severe loss, surrendered

on the 25th of August, 1706.

The fleet then proceeded to Iviça and Majorca, which

surrendered to King Charles III., and detachments of

Marines were placed as garrisons in those islands.

1707

The defeat of the allied forces under the Earl of

Galway by the Duke of Berwick at Almanza, on the

25th of April, 1707, cast a gloom over the prospects of

King Charles in Spain; and in June following, measures

were adopted for co-operating with the Duke of Savoy

and the Prince Eugene, in an attack upon Toulon.

The fleet proceeded for the coast of Italy, and anchored

between Nice and Antibes, when a conference

took place with the commanders-in-chief of the sea and

land forces, and it was decided that a joint attack[10]

should be made upon a portion of the enemy’s army

which was entrenched upon the river Var; the enemy

having evacuated his positions, they were immediately

occupied by several hundred British seamen and marines;

the passage was thus secured for the Duke of

Savoy to prosecute his designs, and ships were stationed

along different parts of the sea-coast: every aid was

afforded by the fleet; but the enemy, having been reinforced,

made a successful sally, and the allied forces

sustained considerable loss; the siege was consequently

raised on the 10th of August following.

1708

In consequence of King Charles having desired that

Sardinia should be reduced, with a view to a passage

being opened for his troops into Naples to attack Sicily,

and also to secure the means of supplying provisions

for his armies, it was decided that a body of marines

should be withdrawn from Catalonia to assist in this

enterprise. On the 12th of August, 1708, the armament

designed for this service arrived before Cagliari,

the capital of Sardinia, and after receiving a hesitating

reply to the summons to surrender, the bombardment

commenced on that evening, and continued until the

following morning, when, at the break of day, Major-General

Wills (Thirtieth regiment), at the head of the

Marines, with one Spanish regiment, landed, and the

place surrendered.

It was next decided that an attempt should be made

upon the island of Minorca. The fleet accordingly

set sail, and arrived before Port Mahon on the 28th of

August, 1708.

At this period the six marine regiments had been

much reduced in numbers by the arduous services on

which they had been employed from the commencement

of the war, so that it became necessary to draft[11]

the men of two of these corps into the other four regiments,

in order to render this force effective for the

service for which it was now destined, and which, there

was reason to expect, would be difficult, and would

require the most energetic measures towards effecting

the conquest of the island. For this purpose all the

Marines fit for service, were drawn from the ships

about to return home, and were incorporated in the

four regiments which were employed in the reduction

of this island. The two regiments (Holl’s and Shannon’s)

returned to England in order to recruit their

numbers.

The fleet proceeded to commence operations, and the

first attack was against Fort Fornelle, which was cannonaded,

and surrendered after a contest of four hours;

a detachment proceeded to Citadella, the capital, which

surrendered; batteries, which had been erected, were

opened on the works defending the town of Port Mahon,

on the 17th of September, when, after a short but brisk

fire, a lodgment was effected under the walls of St.

Philip’s Castle, and on the following day the place surrendered.

The valuable and important Island of Minorca was

thus reduced to submission to the British Crown by

the gallantry of the Navy, and about two thousand four

hundred Marines; the island, which was ceded to

Great Britain at the Treaty of Utrecht, in 1713, continued

in the British possession until the year 1756,

when it was recaptured by a combined Spanish and

French force under the command of Marshal the Duke

de Richelieu.[7]

[12]

1709

In the early part of the year 1709, an armament was

prepared for the purpose of attacking Port Royal in

the province of Nova Scotia, which was then in possession

of the French; the expedition was entrusted

to Colonel Nicholson of the Marines, and to Captain

Martin of the Navy. The squadron proceeded to

Boston, where it was reinforced by some ships, and by

provincial auxiliary troops: a council of war was held,

and arrangements were made for disembarking the

troops, which took place on the 24th of September.

The fortress surrendered on the 1st of October, and the

Marines took possession. The fortress was named

Anna-polis Royal, in honor of Queen Anne, in whose

reign the conquest was effected.

The affairs of Spain at this time had materially

changed, and the prospects of King Charles III. in

obtaining the monarchy had become very doubtful.

The town of Alicant, after sustaining a powerful siege

by the forces of Spain and France, was compelled to

surrender in April; the fleet under Admiral Sir

George Byng, and the troops on board under Lieut.-General[13]

Stanhope, which were destined for its relief,

were prevented, by heavy gales and severe weather,