[i]

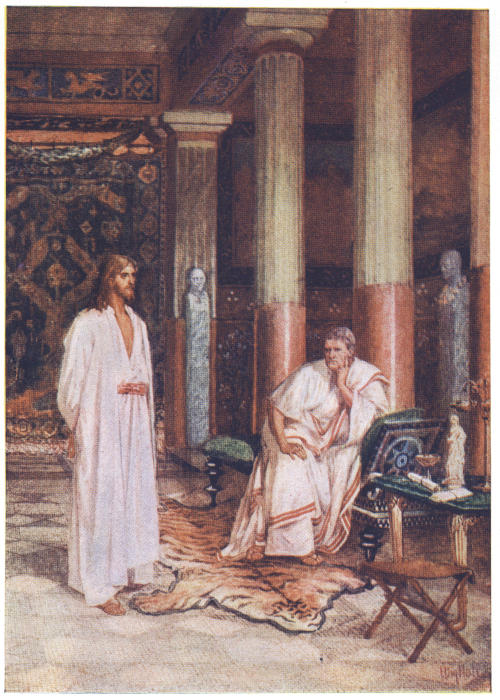

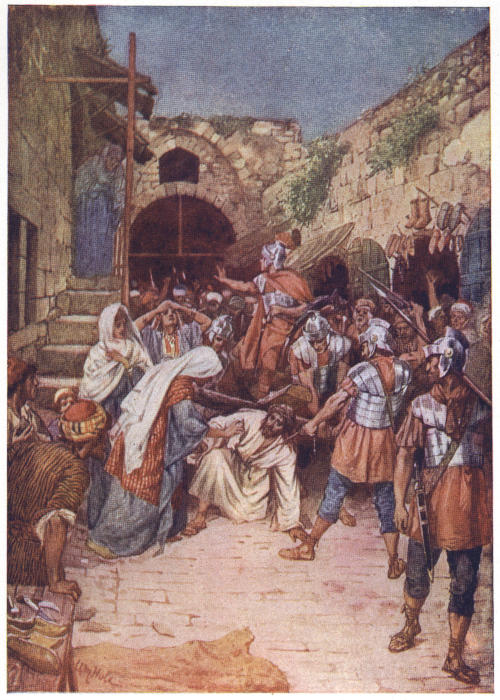

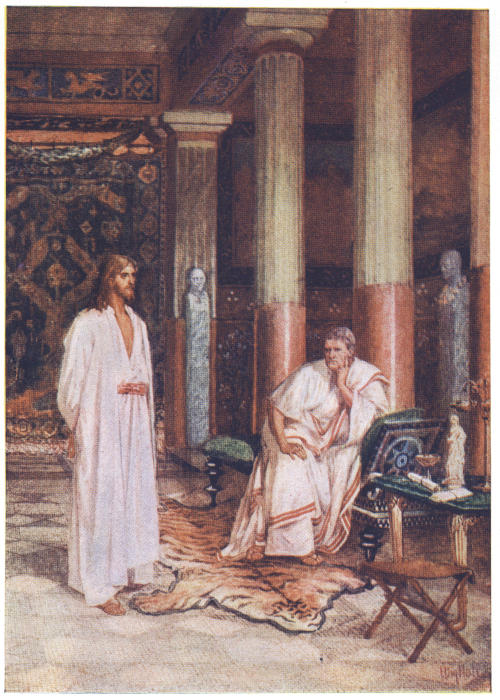

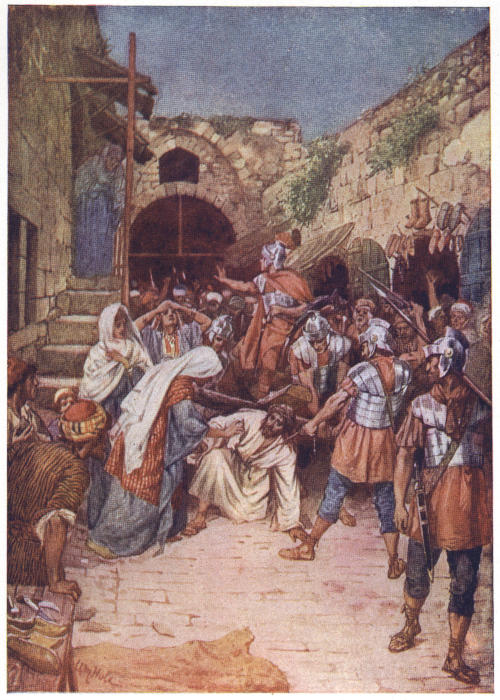

Jesus Arraigned Before Pilate

Then led they Jesus from Caiaphas unto the hall of judgment: and

it was early; and they themselves went not into the judgment hall,

lest they should be defiled; but that they might eat the passover. Pilate

then went out unto them, and said, What accusation bring ye against

this man?—And they began to accuse him, saying, We found this fellow

perverting the nation, and forbidding to give tribute to Cæsar, saying that

he himself is Christ a King.—St. John xviii: 28, 29; St. Luke xxiii: 2.

NOTE BY THE ARTIST

Priding themselves upon their strict administration of justice, the Romans

not infrequently erected their tribunals in the open air, by the city gate, in the

market-place or theatre, or even at the roadside, in order that all might have

the opportunity of seeing and hearing. The design of Herod’s magnificent

palace, now the official residence of Pilate, evidently made permanent provision

for this method of official procedure, the “Gabbatha”—a platform—being

a tesselated pavement in front of the Judgment Hall, to which access was

obtained by a flight of steps. In the centre of this pavement was a slightly-raised

platform, upon which was placed the curule chair of the procurator,

with seats to right and left for the assessors; other officers of the court occupying

benches on the lower level.

61

[ii]

[iii]

THE

LIFE OF JESUS CHRIST

FOR THE YOUNG

BY THE

REV. RICHARD NEWTON, D.D.

AND

HIS LIFE DEPICTED IN A

GALLERY OF EIGHTY PAINTINGS

BY

WILLIAM HOLE

ROYAL SCOTTISH ACADEMY

VOL. IV

PHILADELPHIA

GEORGE BARRIE’S SONS, Publishers

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

[iv]

COPYRIGHTED, 1876-1880, BY G. & B.

RENEWED, 1904-1907, BY GEORGE BARRIE & SONS

COPYRIGHTED, 1913, BY GEORGE BARRIE & SONS

| CHAPTER |

|

PAGE |

|

The Gallery of the Life of Jesus Christ |

vii |

| I |

Jesus in Gethsemane |

1 |

| II |

The Betrayal and Desertion |

29 |

| III |

The Trial |

59 |

| IV |

The Crucifixion |

89 |

| V |

The Burial |

121 |

| VI |

The Resurrection |

151 |

| VII |

The Ascension |

179 |

| VIII |

The Day of Pentecost |

211 |

| IX |

The Apostle Peter |

239 |

| X |

St. John and St. Paul |

271 |

|

Analytical Index |

301 |

|

Index of Poems |

319 |

[vi]

[vii]

THE GALLERY OF THE LIFE OF

JESUS CHRIST

VOLUME IV

| NUMBER |

|

PAGE |

| 61. |

Jesus Arraigned Before Pilate |

Fronts. |

| 62. |

Jesus Privately Examined by Pilate |

14 |

| 63. |

Herod Expecteth to be Amused |

28 |

| 64. |

Jesus is Scourged |

42 |

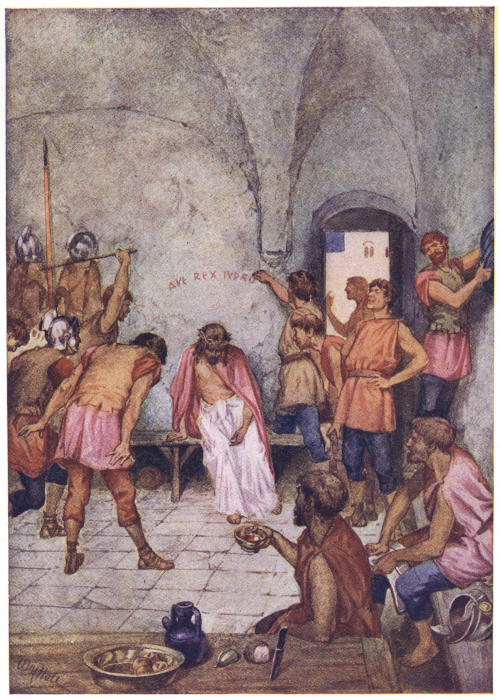

| 65. |

Jesus, Arrayed in Mock State, is Crowned and Beaten |

56 |

| 66. |

Pilate Washeth His Hands |

70 |

| 67. |

“Daughters of Jerusalem, Weep Not for Me” |

84 |

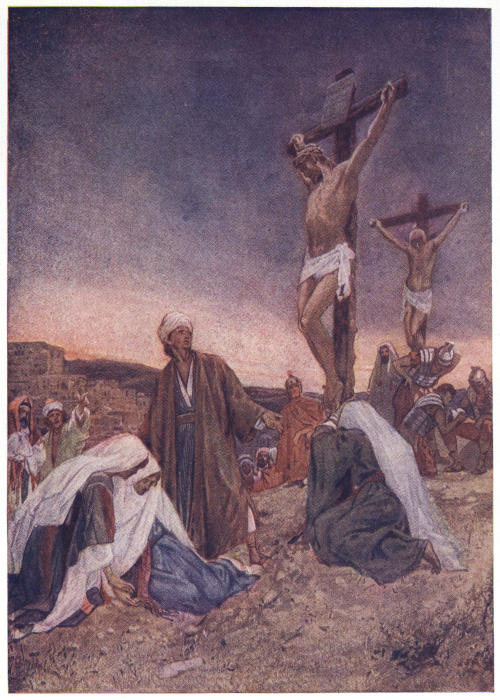

| 68. |

Jesus Attached to the Cross |

98 |

| 69. |

Jesus Commendeth His Mother to John |

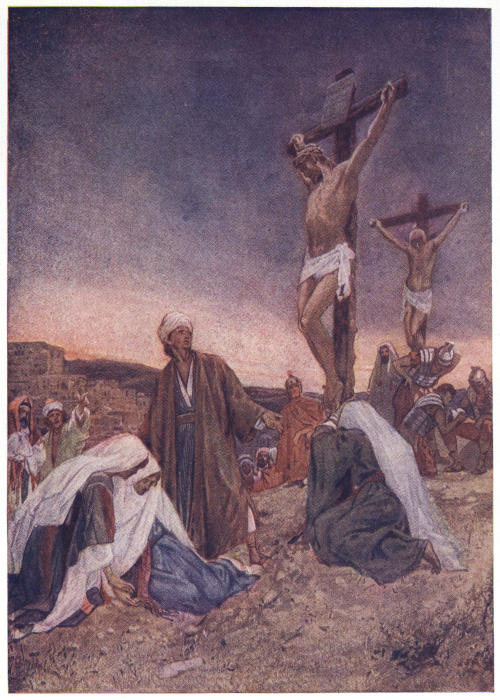

112 |

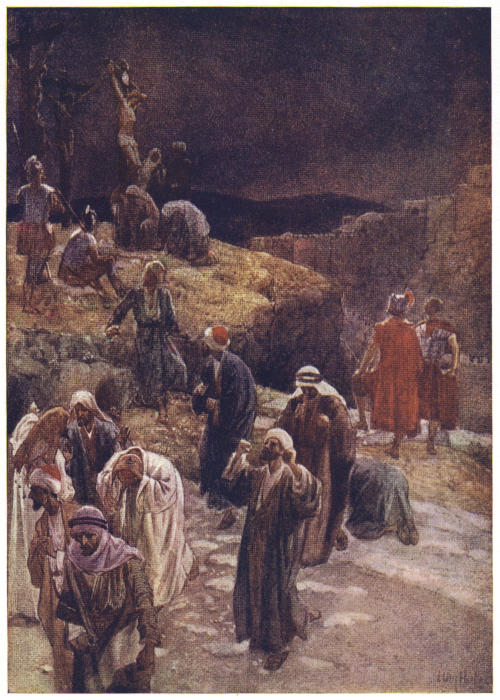

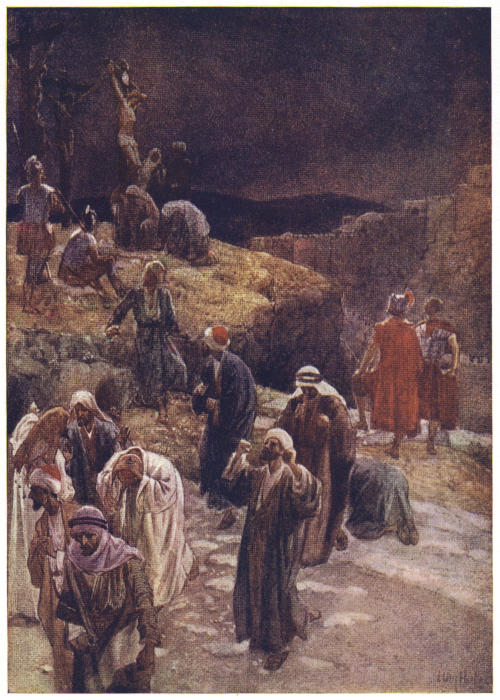

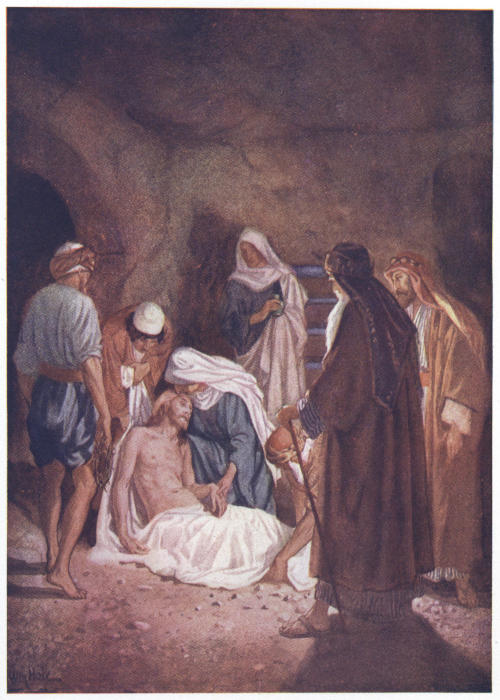

| 70. |

Jesus Yieldeth Up the Ghost |

126 |

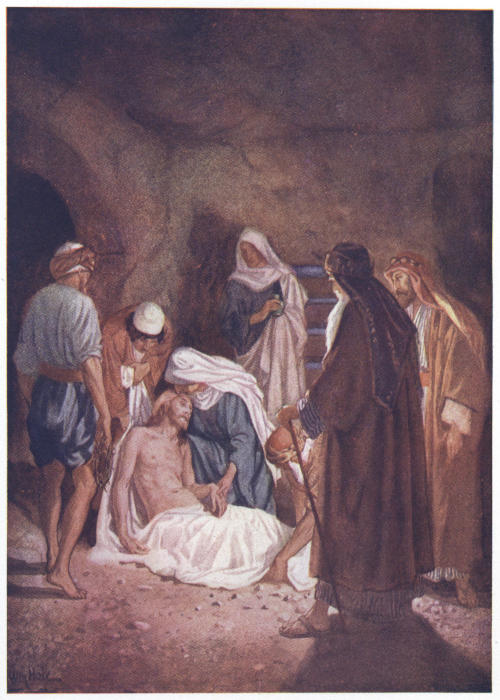

| 71. |

The Body of Jesus Laid in the Tomb |

140 |

| 72. |

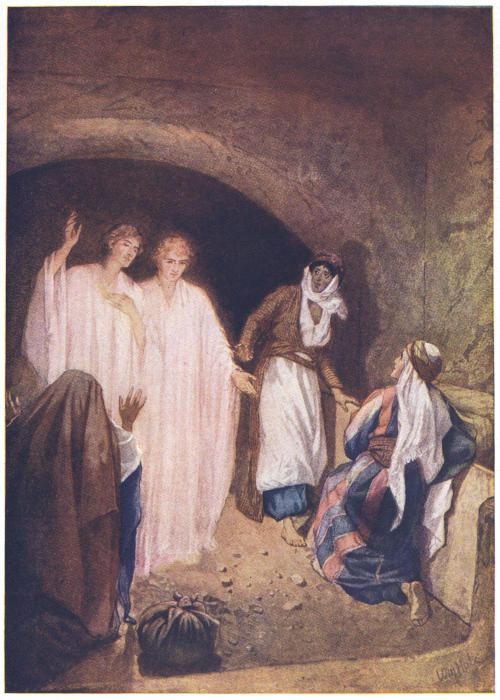

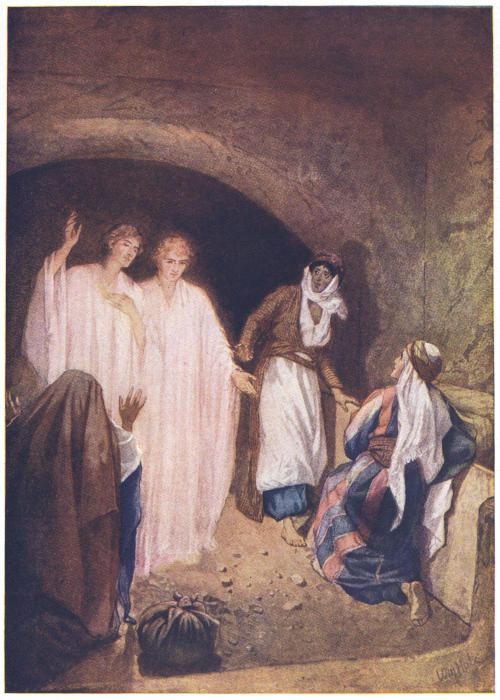

“He is not Here, but is Risen” |

154 |

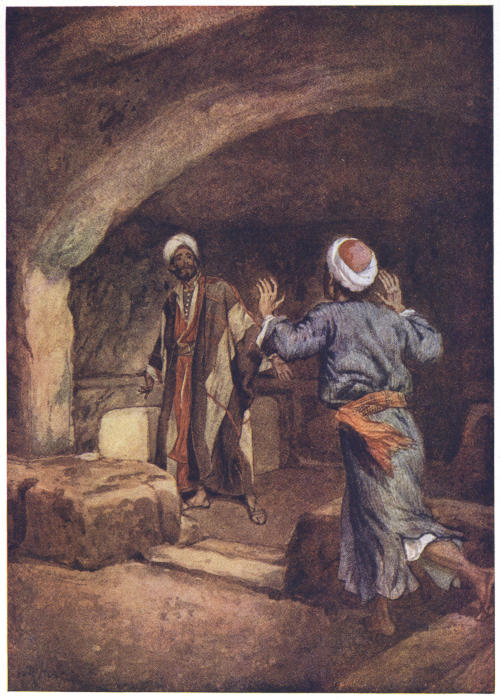

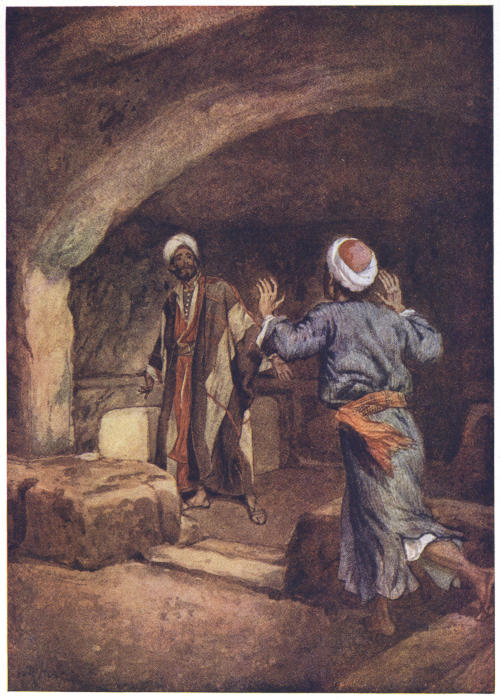

| 73. |

Peter and John in the Sepulchre |

168 |

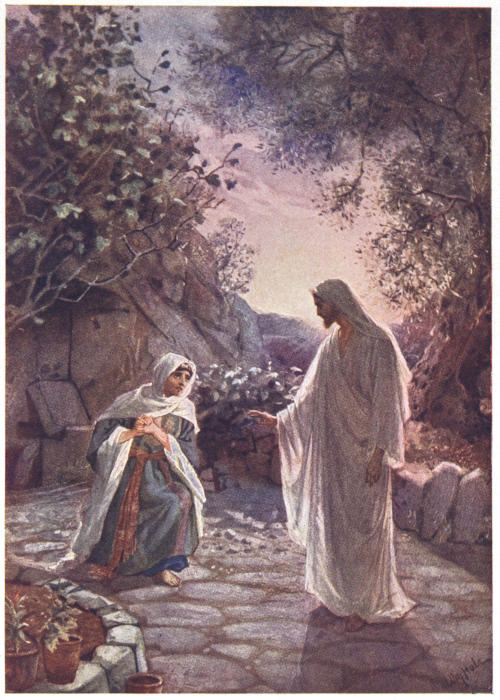

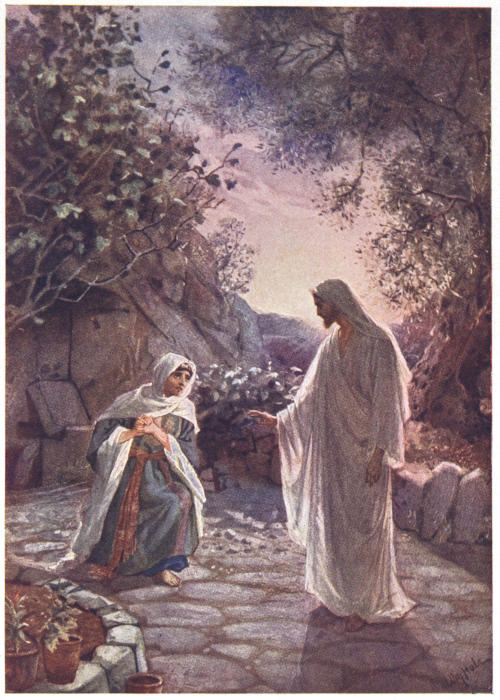

| 74. |

Jesus Revealeth Himself to Mary Magdalene |

182 |

| 75. |

On the Road to Emmaus |

196 |

| 76. |

Jesus Appeareth to and Pardons Simon Peter |

210 |

| 77. |

The Incredulity and Confession of Thomas |

224 |

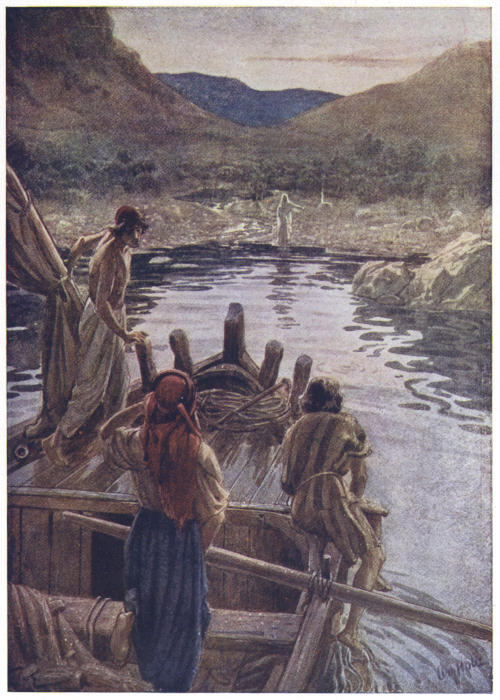

| 78. |

Jesus Showeth Himself at the Sea of Tiberius |

254 |

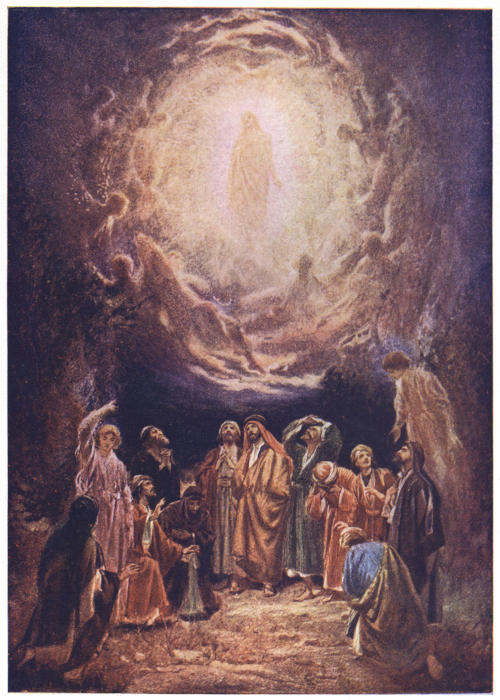

| 79. |

Jesus, His Work Accomplished, Ascends Into Heaven |

268 |

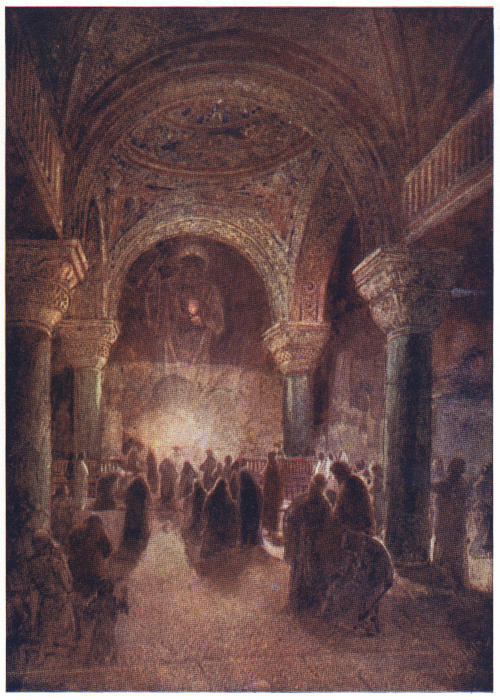

| 80. |

The Church of Jesus Christ |

282 |

[viii]

In sailing across the ocean, if we attempt to

measure the depth of the water in different

places, we shall find that it varies very much.

There are hardly two places in which it is

exactly the same. In some places it is easy

enough to find the bottom. In others, it is

necessary to lengthen the line greatly before

it can be reached. And then there are other

places where the water is so deep that the

longest line ordinarily used cannot reach to

the bottom. We know that there is a bottom,

but it is very hard to get down to it.

And, in studying the history of our Saviour’s

life, we may compare ourselves to persons sailing

over the ocean. The things that he did,

and the words that he spoke, are like the water

over which we are sailing. And when we try to

understand the meaning of what Jesus said and[2]

did, we are like the sailor out at sea who is

trying to fathom the water over which he is

sailing, and to find out how deep it is. And in

doing this we shall find the same difference

that he finds. Some of the things that Jesus

did and said are so plain and simple that a

child can understand them. These are like

those parts of the ocean where a very little line

will reach the bottom. Other things that Jesus

did and said require hard study, if we wish to

understand them. But then, there are other

parts of the sayings and doings of Jesus which

the best and wisest men, with all their learning

and study, cannot fully understand or explain.

These are like those places in the sea where

we cannot reach the bottom with our longest

lines.

We find our illustration of this in the garden

of Gethsemane. Some of the things that were

done and said there we can easily understand.

But other things are told us, of what Jesus

did and said there which are very hard to

explain.

In speaking about this part of our Saviour’s

life, there are two things for us to notice. These

are what we are told about Gethsemane, and

what we are taught by the things that took place[3]

there. Or, a shorter way of stating it will be to

say that our subject now is—the facts—and the

lessons of Gethsemane.

Let us look now at the facts that are told us

about Gethsemane. It is a fact that there was

such a place as Gethsemane, near Jerusalem,

when Jesus was on earth, and that there is such

a place there now. It is a fact that Gethsemane

was a garden or orchard of olive trees then, and

so it is still. Everyone who goes to Jerusalem

is sure to visit this spot, because it is so sacred

to all Christian hearts on account of its connection

with our Saviour’s sufferings. The side

of the Mount of Olives on which Gethsemane

stands is dotted over with olive trees. A portion

of the hill has been enclosed with stone

walls. This is supposed to be the spot where

our Lord’s agony took place. Inside of these

walls are eight large olive trees. They are

gnarled and crooked, and very old. Some suppose

they are the very trees which stood there

when Jesus visited the spot, on the night in

which he was betrayed. But this is not likely.

For we know that when Titus, the Roman

general, was besieging Jerusalem, he cut down

all the trees that could be found near the city.

But the trees now there have probably sprung[4]

from the roots of those that were growing in

Gethsemane on this very night.

It is a fact that after keeping the last Passover,

and observing, for the first time the Lord’s

Supper with his disciples, Jesus left Jerusalem

near midnight with the little band of his followers.

He went down the side of the hill on

which the city stood and crossed the brook

Kedron on the way to Gethsemane. It is a

fact that on going into the garden he left eight

of his disciples at the entrance. It is a fact

that he took with him the chosen, favored three,

Peter, James, and John, and went further into

the garden. It is a fact that then he “began to

be sorrowful and very heavy. Then saith he—my

soul is exceeding sorrowful, even unto

death.” It is a fact that he withdrew from the

three disciples, and, alone with God, he bowed

himself to the earth, and prayed, saying, “O,

my Father, if it be possible, let this cup pass

from me.” It is a fact that after offering this

earnest prayer he returned to his disciples and

found them asleep, and said to Peter, “What!

could ye not watch with me one hour? Watch

and pray, that ye enter not into temptation.”

It is a fact that he went away again, “and being

in an agony he prayed more earnestly, and his[5]

sweat was, as it were, great drops of blood

falling down to the ground.” It is a fact that

in the depths of his agony, “there appeared

unto him an angel from heaven strengthening

him.” We are not told what the angel said to

him. No doubt he brought to him some tender,

loving words from his Father in heaven, to

comfort and encourage him. It is a fact that

he returned to his disciples again and found

them sleeping, for their eyes were heavy. It is

a fact that he went away again, and prayed,

saying, “O, my Father, if this cup may not pass

from me except I drink it, thy will be done.”

It is a fact that he returned the third time to

his disciples, and said—“Sleep on now, and

take your rest: behold the hour is at hand, and

the Son of Man is betrayed into the hands of

sinners. Rise, let us be going: behold he is at

hand that doth betray me.” And it is a fact

that, immediately after he had spoken these

words, the wretched Judas appeared with his

band to take him. These are the facts told us

by the evangelists respecting Jesus and his

agony in Gethsemane. They are very wonderful

facts, and the scene which they set before us

in our Saviour’s life is one of the most solemn

and awful that ever was witnessed.

[6]

And now, let us go on to speak of the lessons

taught us by these facts. These lessons are four.

The first lesson we learn from Gethsemane is a

lesson—about prayer.

As soon as this great trouble came upon our

blessed Lord in Gethsemane, we see him, at

once separating himself from his disciples, and

seeking the comfort and support of his Father’s

presence in prayer. And this was what he was

in the habit of doing. We remember how he

spent the night in prayer before engaging

in the important work of choosing his disciples.

And now, as soon as the burden of

this great sorrow comes crushing down upon

him, the first thing he does is to seek relief in

prayer.

The apostle Paul is speaking of this, when he

says, “he offered up prayers and supplications,

with strong crying and tears, unto him that was

able to save him from death, and was heard in

that he feared.” Heb. v: 7. This refers particularly

to what took place here in Gethsemane.

The earnestness which marked our Saviour’s

prayers on this occasion is especially mentioned.

He mingled tears with his prayers. It appears

from what the apostle here says, that there was

something connected with his approaching[7]

death upon the cross that Jesus particularly

feared. We are not told what it was. And it

is not worth while for us to try and find it out,

for we cannot do it. But the prayer of Jesus,

was not in vain. “He was heard, in that he

feared.” No doubt this refers to what took

place when the angel came to strengthen him.

His prayer was not answered literally. He was

not actually saved from death; but he was saved

from what he feared in connection with death.

Our Lord’s experience, in this respect, was like

that of St. Paul when he prayed to be delivered

from the thorn in the flesh. The thorn was not

taken away, but grace was given him to bear it,

and that was better than having it taken away.

The promise is—“Cast thy burden upon the

Lord, and he shall sustain thee.” Ps. lv: 22.

And so, from the gloomy shades of Gethsemane,

with our Saviour’s agony and bloody sweat, there

comes to us a precious lesson about prayer. We

see Jesus praying under the sorrows that overwhelmed

him there: his prayer was heard, and

he was helped.

And thus, by the example of our blessed Lord,

we are taught, when we have any heavy burden

to bear, or any hard duty to do, to carry it to

the Lord in prayer.

[8]

Let us look at some examples from every day

life of the benefit that follows from prayer.

“Washington’s Prayer.” General Washington

was one of the best and greatest men that this

country, or any other, ever had. He was a man

of piety and prayer.

While he was a young man, he was appointed

by Governor Dinwiddie, of Virginia, to the

command of a body of troops, and sent on

some duty in the western part of that state. A

part of these troops was composed of friendly

Indians. There was no chaplain in that little

army, and so Washington used to act as chaplain

himself. He was in the habit of standing up,

in the presence of his men, with his head

uncovered, and reverently asking the God of

heaven to protect and bless them in the work

they were sent to do. And no doubt, the great

secret of Washington’s success in life, was his

habit of prayer. He occupied many positions

of honor and dignity during his useful life.

But, never did he occupy any position in which

he appeared so manly, so honorable, and so

truly noble, as when he stood forth, a young

man, in the presence of his little army, and tried

to lift up their thoughts to God above, as the

one “from whom all blessings flow.”

[9]

“Praying Better Than Stealing.” A poor family

lived near a wood wharf. The father of this

family got on very well while he kept sober;

but when he went to the tavern to spend his

evenings and his earnings, as he did sometimes,

then his poor family had to suffer. One winter,

during a cold spell of weather, he was taken

sick from a drunken frolic. Their wood was

nearly gone.

After dark one night, he called his oldest boy

John to his bedside, and whispered to him to

go to the wood wharf and bring an armful of

wood.

“I can’t do that,” said John.

“Can’t do it—why not?”

“Because that would be stealing, and since I

have been going to Sabbath-school, I’ve learned

that God’s commandment is, ‘Thou shalt not

steal.’”

“Well, and didn’t you learn that another of

God’s commandments is—‘Children, obey your

parents?’”

“Yes, father,” answered the boy.

“Well, then, mind and do what I tell you.”

Johnny was perplexed. He knew there must

be some way of answering his father, but he

did not know exactly how to do it. The right[10]

thing would have been for him to say that,

when our parents tell us to do what is plainly

contrary to the command of God, we must obey

God rather than men. But Johnny had not

learned this yet. So he said:

“Father, please excuse me from stealing. I’ll

ask God to send us some wood. Praying’s

better than stealing. I’m pretty sure God will

send it. And if it don’t come before I come

home from school at noon to-morrow, I will go

and work for some, or beg some. I can work,

and I can beg, but I can’t steal.”

Then Johnny crept up into the loft where he

slept, and prayed to God about this matter. He

said the Lord’s prayer, which his teacher had

taught him. And after saying—“give us this

day our daily bread;” he added—“and please

Lord send us some wood too, and let father see

that praying is better than stealing—for Jesus’

sake. Amen.”

And at noon next day when he came home

from school, as he turned round the corner, and

came in sight of their home, what do you think

was the first thing he saw? Why, a load of

wood before their door! Yes, there it was.

His mother told him the overseers of the

poor had sent it. He did not know them. He[11]

believed it was God who sent it. And he was

right.

The first lesson from Gethsemane is about

prayer.

The second lesson from this hallowed spot is—about

sin.

Here, in Gethsemane, we see Jesus engaged

in paying the price of our redemption: this

means, what he had to suffer for us before our

sins could be pardoned. The pains and sorrows

through which Jesus passed, in the agony of

the garden, and the death on the cross: the

sighs he heaved—the groans he uttered—the

tears he shed—the fears, the griefs, the unknown

sufferings that he bore—all these were

part of the price he had to pay, that we might

be saved from our sins.

When we read of all that Jesus endured in

Gethsemane: when we hear him say—“my soul

is exceeding sorrowful, even unto death:” when

we see him fall to the earth, in such an agony

that “his sweat was, as it were, great drops of

blood falling down to the ground:” we may

well ask the question—what was it which caused

him all this fearful suffering? And there is only

one way of answering this question; and this

is by saying that he was bearing the punishment[12]

of our sins. There was nothing else that could

have made him feel so sad and sorrowful. But

this explains it all. Then, as the prophet says—“He

was wounded for our transgressions, he

was bruised for our iniquities;—and the Lord

had laid on him the iniquity of us all.” Is. liii:

5, 6. Our sins had provoked the wrath of God

against us, and Jesus was bearing that wrath for

us. In all the world, there is nothing that

shows so clearly what a fearful thing sin is, as

the awful sufferings of Jesus when he was paying

the price of our sins, or making atonement

for us. And it is by knowing what took place

in Gethsemane, and on Calvary, and only in this

way, that we can learn what a terrible evil sin

is, and how we are to be saved from it.

Some years ago, there was a good Christian

lady in England who had taken into her family

a deaf and dumb boy. She was anxious to teach

him the lesson of Gethsemane and Calvary;

that Christ had suffered and died for our sins.

Signs and pictures were the only means by

which she could teach him. So she drew a

picture of a great crowd of people, old and

young, standing near a deep, wide pit, out of

which smoke and flames were issuing, and into

which they were in danger of being driven.[13]

Then she drew the figure of one who came

down from heaven, representing Jesus, the Son

of God. She explained to the boy that when

this person came, he asked God not to throw

those people into the pit, because he was willing

to suffer and to die for them, that the pit might

be shut up and the people saved.

The deaf and dumb boy wondered much:

and then made signs that the person who

offered to die was only one, while the guilty

ones who deserved to die were many. He did

not understand how God could be willing to

take one, in the place of so many. The lady

saw the difficulty that was in the boy’s mind.

Then she took a gold ring off from her finger,

and put it down by the side of a great heap of

withered leaves, from some faded flowers, and

then asked the boy, by signs, which was the

more valuable, the one gold ring, or the many

withered leaves? The boy took in the idea at

once. He clapped his hands with delight,

and then by signs exclaimed—“The one—the

golden one.” And then to show that he knew

what this meant, and that the life of Jesus was

worth more than the world of sinners for which

he died, he ran and got his letters, and spelled

the words—“Good! The golden one good!”[14]

The deaf and dumb boy had learned two great

lessons that day. For one thing he had learned

this lesson about sin which we are trying to

learn from Gethsemane. He saw what a dreadful

thing sin is, when it was necessary for Jesus

to die before it could be pardoned. And then,

at the same time, he learned a lesson about

Jesus. He saw what a golden, glorious character

he is: that he is perfect man, and perfect God.

This made his blood so precious that the shedding

of that blood was a price sufficient to pay

for the sins of the whole world.

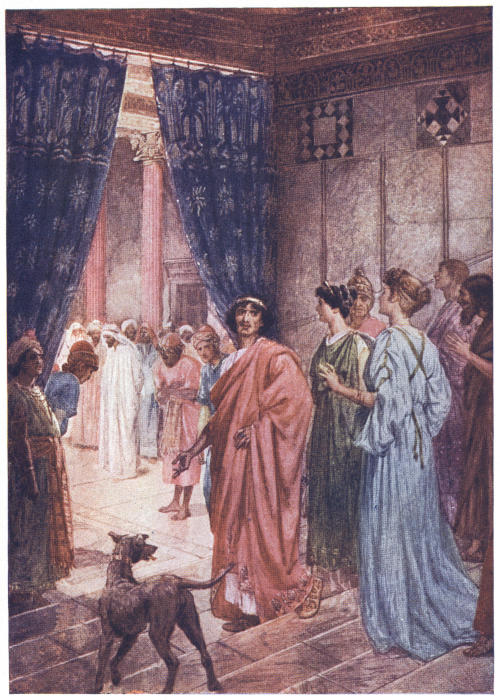

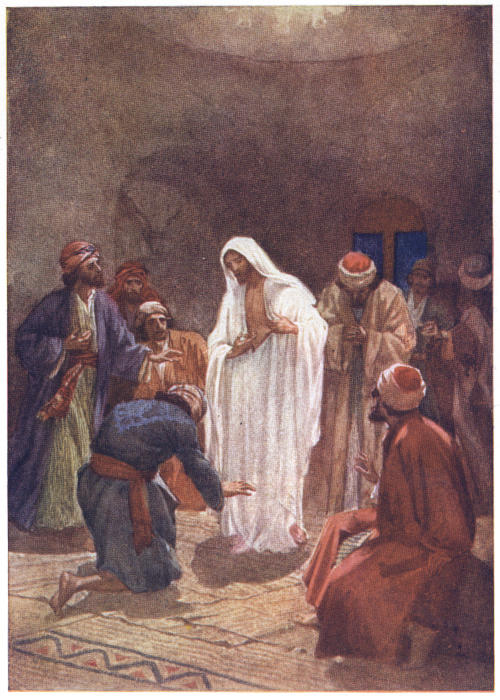

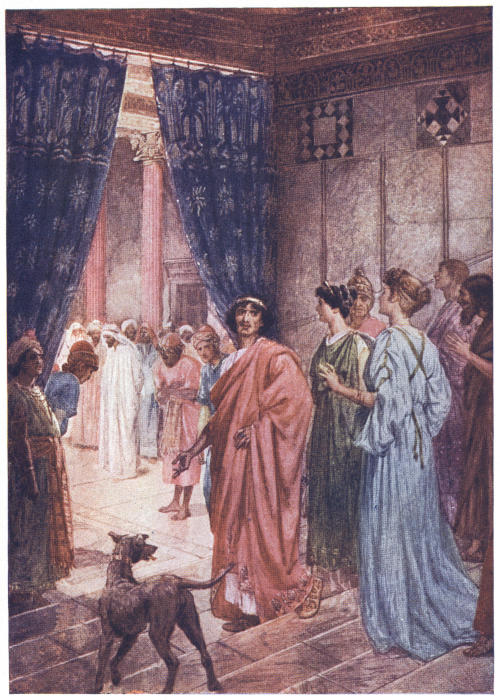

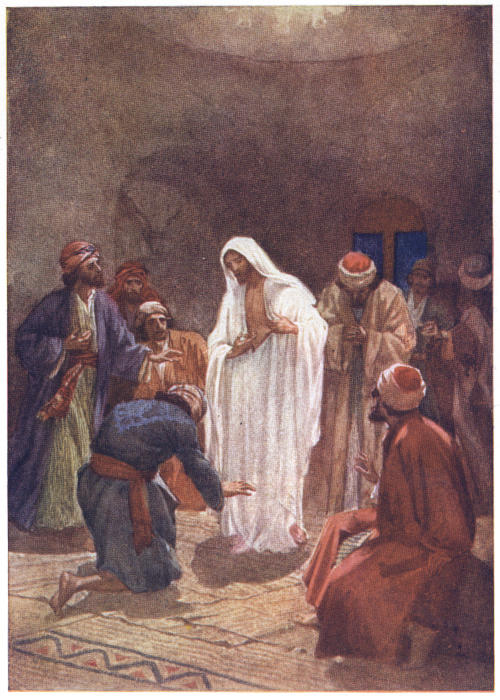

Jesus Privately Examined by Pilate

Then Pilate entered into the judgment hall again, and called Jesus,

and said unto him, Art thou the King of the Jews? Jesus answered

him, Sayest thou this thing of thyself, or did others tell it thee of

me? Pilate answered, Am I a Jew? Thine own nation and the

chief priests have delivered thee unto me: what hast thou done? Jesus

answered, My kingdom is not of this world: if my kingdom were of this

world, then would my servants fight, that I should not be delivered to

the Jews: but now is my kingdom not from hence. Pilate therefore

said unto him, Art thou a king then? Jesus answered, Thou sayest

that I am a king. To this end was I born, and for this cause came I

into the world, that I should bear witness unto the truth. Every one

that is of the truth heareth my voice. Pilate saith unto him, What is

truth?—St. John xviii: 33-38.

NOTE BY THE ARTIST

If Herod’s palace was built according to the customary Roman method,

the private examination of Jesus would naturally be conducted either in the

library, or in Pilate’s business room—apartments which usually occupied positions

on opposite sides of a short passage leading from the further extremity

of the spacious atrium to the inner halls and chambers of the palace. There

were six examinations of our Lord: (1) before Annas for fact; (2) before

Caiaphas for determinations; (3) before the Sanhedrim for official confirmation;

(4) before Pilate for preliminary enquiry; (5) before Herod Antipas as

Tetrarch of Galilee; (6) before Pilate for final acquittal or condemnation.

62

And now, let us see, for a moment, how

much good is done by telling to poor sinners

this story of Gethsemane and Calvary, and of

the sufferings of Jesus there. Here is an illustration

of the power of this story, for which we

are indebted to one of the Moravian Missionaries

in Greenland.

Kazainak was a robber chief, who lived among

“Greenland’s icy mountains.” He came, one

day to a hut, where the missionary was engaged

in translating into the language of that country

the gospel of St. John. He saw the missionary

writing and asked him what he was doing.

Pointing to the letters he had just written, he

said those marks were words, and that the book[15]

from which they were written could speak. Kazainak

said he would like to hear what the book

had to say. The missionary took up the book,

and read from it the story of Christ’s crucifixion.

When he stopped reading the chief asked:

“What had this man done, that he was put

to death? had he robbed any one? or murdered

any one? had he done wrong to any one? Why

did he die?”

“No,” said the missionary. “He had robbed

no one; he had murdered no one; he had done

no wrong to any one.”

“Then, why did he die?”

“Listen,” said the missionary. “Jesus had

done no wrong; but Kazainak has done wrong.

Jesus had robbed no one; but Kazainak has

robbed many. Jesus had murdered no one; but

Kazainak has murdered his brother; Kazainak

has murdered his child. Jesus suffered that

Kazainak might not suffer; Jesus died that

Kazainak might not die.”

“Tell me that again,” said the astonished

chief. It was told him again, and the end of it

was that the hard-hearted, blood-stained murderer

became a gentle, loving Christian. He

never knew what sin was till he heard of

Christ’s sufferings for it.

[16]

The second lesson we learn from Gethsemane

is—the lesson about sin.

The third lesson from Gethsemane is the lesson

about submission.

Jesus taught us in the Lord’s prayer to say,

“Thy will be done on earth, as it is in heaven.”

And this is one of the most important lessons

we ever have to learn. It is very easy to say

these words—“Thy will be done;” but it is not

so easy to feel them, and to be and do just what

they teach. The will of God is always right,

and good, and holy. Everything opposed to

his will is sinful. St. Paul tells us that—“sin is

the transgression of the law.” To transgress a

law, means to walk over it, or to break it. But

the law of God is only his will made known.

And so, everything that we think, or feel, or

say, or do, contrary to the will of God—is sin.

And when we remember this it should make us

very anxious to learn the lesson of submission

to the will of God. If we could all learn to do

the will of God as the angels do, it would make

our earth like heaven. And this is one reason

why Jesus was so earnest in teaching us this

lesson. He not only preached submission to

the will of God, but practised it. When he

entered Gethsemane, he compared the dreadful[17]

sufferings before him to a cup, filled with something

very bitter, which he was asked to drink.

Now, no person, however good or holy he may

be, likes to endure dreadful sufferings. It is

natural for us to shrink back from suffering,

and to try to get away from it. And this was

just the way that Jesus felt. He did not love

suffering any more than you or I do. And so,

when he prayed the first time in Gethsemane,

with those terrible sufferings immediately before

him, his prayer was—“Father, if it be possible,

let this cup pass from me.” But the cup did

not pass away. It was held before him still.

He saw it was his Father’s will for him to drink

it. So, when he prayed the second time, his

words were—“O, my Father, if this cup may

not pass from me, except I drink it: thy will

be done!” This was the most beautiful example

of submission to the will of God the world has

ever seen.

When Adam was in the garden of Eden he

refused to submit to the will of God. He said,

by his conduct, “Not thy will, but mine be

done:” and that brought the curse upon the

earth, and filled it with sorrow and death.

When Jesus was in the garden of Gethsemane,

he submitted to the will of God. He said, “Not[18]

my will, but thine, be done.” This took away

the curse which Adam brought upon the earth,

and left a blessing in the place of it—even life,

and peace, and salvation.

We ought to learn submission to the will of

God, because he knows what is best for us.

“The Curse of the Granted Prayer.” A

widowed mother had an only child—a darling

boy. Her heart was wrapped up in him. At

one time he was taken very ill. The doctor

thought he would die. She prayed earnestly

that his life might be spared. But she did not

pray in submission to the will of God. She said

she did not want to live unless her child was

spared to her. He was spared. But, he grew

up to be a selfish, disobedient boy. One day,

in a fit of passion, he struck his mother. That

almost broke her heart. He became worse and

worse; and, at last, in a drunken quarrel, he

killed one of his companions. He was taken to

prison; was tried—condemned to be hanged—and

ended his life on the gallows. That quite

broke his mother’s heart.

Now God, in his goodness, was going to save

that mother from all this bitter sorrow. And

would have done so if she had only learned

to say—“Thy will be done.” She would not[19]

say that. The consequence was that she brought

on herself all that heart-breaking sorrow.

And then we ought to learn submission to

the will of God—because, whatever he takes away

from us—he leaves us so many blessings still!

Here is a good illustration of this part of our

subject. Some years ago, in a town in New

England, there was a minister of the gospel

who was greatly interested in his work. But

he was attacked with bleeding of the lungs and

was obliged to stop preaching and resign the

charge of his church. About the same time his

only child was laid in the grave; his wife, for a

time, lost the use of her eyes; his home was

broken up, and his prospects were very dark.

They had been obliged to sell their furniture

and take boarding at a tavern in the town where

they lived. But, under all these trials, he was

resigned and cheerful. He felt the supporting

power of that precious gospel which he had so

loved to preach. His wife had not felt as contented

and cheerful under their trials as he was.

One day, as he came in from a walk, she said

to him: “Husband dear, I have been thinking

of our situation here, and have made up my

mind to try and be patient and submissive to

the will of God.”

[20]

“Ah,” said he, “that’s a good resolution. I’m

very glad to hear it. Now, let us see what we

have to submit to. I will make a list of our

trials. Well, in the first place, we have a comfortable

home; we’ll submit to that. Secondly,

we have many of the blessings of life left to us;

we’ll submit to that. Thirdly, we are spared to

each other; we’ll submit to that. Fourthly, we

have a multitude of kind friends; we’ll submit

to that. Fifthly, we have a loving God, and

Saviour, who has promised to take care of us,

and ‘make all things work together for our

good;’ we’ll submit to that.”

This was a view of their case which his wife

had not taken. And so by the time her husband

had got through with his fifthly, her heart was

filled with gratitude, her eyes with tears, and

she exclaimed: “Stop, stop; please stop, my dear

husband; and I’ll never say another word about

submission.”

The lesson of submission is the third lesson

that we are taught in Gethsemane.

The last lesson for us to learn from this solemn

scene in our Saviour’s life is a lesson—about

tenderness.

Jesus taught us this when he came back, again

and again, from his lonely struggles with the[21]

sufferings he was passing through, and found

his disciples asleep. It seemed very selfish and

unfeeling in them to show no more sympathy

with their Master in the time of his greatest

need. He had told them how full of sorrow he

was, and had asked them to watch with him.

Now, we should have supposed that, under such

circumstances, they would have found it impossible

to sleep. They ought to have been

weeping with him in his sorrow, and uniting in

prayer to God to help and comfort him. But,

instead of this, while he was bearing all the

agony and bloody sweat which was caused

him by their sins, they were fast asleep! If

Jesus had rebuked them sharply for their want

of feeling, it would not have been surprising.

But, he did nothing of the kind. He only

asked, in his own quiet, gentle way—“could

ye not watch with me one hour?” And

then he kindly excused them for their fault,

saying—“The spirit indeed is willing, but

the flesh is weak!” How tender and loving

this was! Here we have the lesson of tenderness

that comes to us from Gethsemane.

We see here, beautifully illustrated, the gentle,

loving spirit of our blessed Saviour. And

the exhortation of the apostle, is—“Let this[22]

mind be in you, which was also in Christ

Jesus.” Phil. ii: 5.

Someone has well said, that “the rule for us

to walk by, if we are true Christians, is, when

any one injures us, to forget one half of it, and

forgive the rest.” This is the very spirit of our

Master. This was the way in which he acted

towards his erring disciples in Gethsemane.

And, if all who bear the name of Christ were

only trying to follow his example, in this

respect, who can tell how much good would

be done?

Here are some beautiful illustrations of this

lesson of tenderness and forbearance which

Jesus taught us in Gethsemane.

“The Influence of This Spirit in a Christian

Woman.” A parish visitor had a district to

attend to which contained some of the worst

families in town. There was a sick child in

one of those families. The visitor called on her

every day. The grandfather of this child was a

wicked, hardened man, who hated religion and

everything connected with it. He had a big

dog that was about as savage as he was himself.

Every day, when he saw this Christian woman

coming to visit the sick child, he would let

loose the dog on her. The dog flew at her,[23]

and caught hold of her dress. But she was a

brave woman, and stood her ground nobly. A

few kind words spoken to the dog took away

all his fierceness. She continued her visits, day

after day, bringing to the poor child such nice

things as she needed. At first the dog was set

upon her every day; but as she went on in her

kind and gentle way, the old man began to feel

ashamed of himself; and before a week was

over, when he saw this faithful Christian woman

coming to the suffering little one, instead of

letting loose the dog upon her, he would take

his pipe out of his mouth with one hand and

lift the cap from his head with the other, and

make a polite bow to her, saying, “Good morning,

ma’am: werry glad to see you.”

And so the spirit of Christ, as practised by

that good woman, won the way for the gospel

into that home of sin and misery, and it brought

a blessing with it, as it always does.

“The Spirit of Christ in a Little Girl.” “Sitting

in school one day,” says a teacher, “I overheard

a conversation between a little girl and

her brother. He was complaining of various

wrongs that had been done to him by another

little boy belonging to the school. His face

grew red with anger, and he became very much[24]

excited in telling of all that this boy had done

to him. He was going on to say how he intended

to pay him back, when his sister interrupted

him by saying, ‘Brother, please don’t

talk any more in that way. Remember that

Charley has no mother.’

“Her brother’s lips were closed at once. This

gentle rebuke from his sister went straight to

his heart. He walked quietly away, saying to

himself—‘I never thought of that.’ He remembered

his own sweet home and the teaching of

his loving mother; and the question came up

to him—‘What should I be if I had no mother?’

He thought how lonely Charley must feel, and

how hard it must be for him to do right without

a mother. This took away all his anger. And

he made up his mind to be kind and forbearing

to poor Charley, and to try to do him all the

good he could. This little girl was following

the example of Christ, and we see what a good

effect it had upon her brother.”

“A Boy with the Spirit of Christ.” Two boys—Bob

Jones and Ben Christie—were left alone

in a country school-house between the morning

and afternoon sessions. Contrary to the

master’s express orders Bob Jones set off some

fireworks. When afternoon school began, the[25]

master called up the two boys, to find out who

had done the mischief.

“Bob, did you set off those fireworks?”

“No, sir,” said Bob.

“Did you do it, Ben?” was the next question.

But Ben refused to answer; and so the master

flogged him severely for his obstinacy.

At the afternoon recess the boys were alone

together. “Ben, why didn’t you deny it?”

asked his companion.

“Because there were only us two there, and

one of us must have lied,” said Ben.

“Then why didn’t you say I did it?”

“Because you had said you didn’t, and I

would rather take the flogging than fasten the

lie on you.”

Bob’s heart melted under this. Ben’s noble

spirit quite overcame him. He felt that he

never could allow his companion to lie under

the charge of the wrong that he had done.

As soon as the school began again, Bob

marched up to the master’s desk, and said:

“Please, sir, I can’t bear to be a liar. Ben

Christie didn’t set off these fire-crackers. I did

it, and he took the flogging rather than charge

me with the lie.” And then Bob burst into

tears.

[26]

The master looked at him in surprise. He

thought of the unjust punishment Ben had

received, his conscience smote him, and his

eyes filled with tears. Taking hold of Bob’s

hand, they walked to Ben Christie’s seat; then

the master said aloud:

“Ben, Ben, my lad, Bob and I have done you

wrong; we both ask your pardon!”

The school was hushed and still as the grave.

You might almost have heard Ben’s big-boy

tears dropping on his book. But, in a moment,

dashing the tears away, he cried out—“Three

cheers for the master.” They gave three cheers.

And then Bob Jones added—“And now three

cheers for Ben Christie”—and they made the

school-house ring again with three rousing

cheers for Ben.

Ben Christie was acting in the spirit of Christ

in what he did that day. And in doing so he did

good to his companion, Bob Jones. He did good

to the master, and to every scholar in the school.

And there is no way in which we can do so

much real good to all about us as by trying to

catch the spirit and follow the example of our

blessed Saviour.

And so, when we think of Jesus in Gethsemane,

let us never forget the facts and the[27]

lessons connected with that sacred place. The

facts are too many to be repeated. The lessons

are four. There is the lesson about prayer; the

lesson about sin; the lesson about submission;

and the lesson about tenderness.

And, as we leave this solemn subject, we may

each of us say, in the words of the hymn:

“Can I Gethsemane forget?

Or there thy conflict see,

Thine agony and bloody sweat,

And not remember thee?

“Remember thee, and all thy pains,

And all thy love to me;

Yes, while a breath, a pulse remains,

Will I remember thee.

“And when these failing lips grow dumb,

And mind, and memory flee,

When thou shalt in thy kingdom come,

Jesus, remember me.”

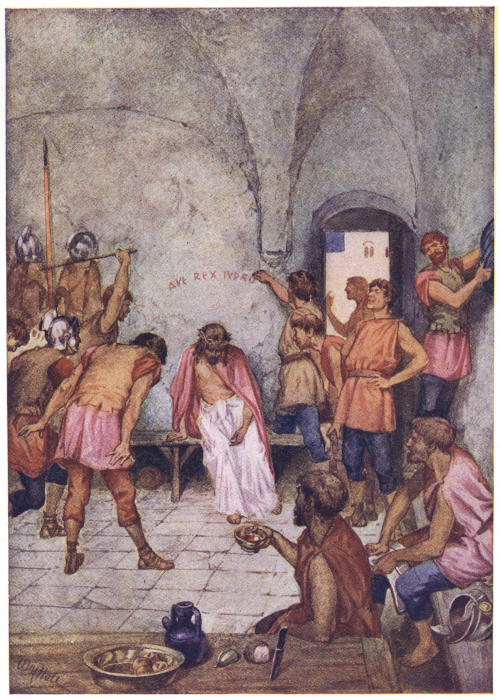

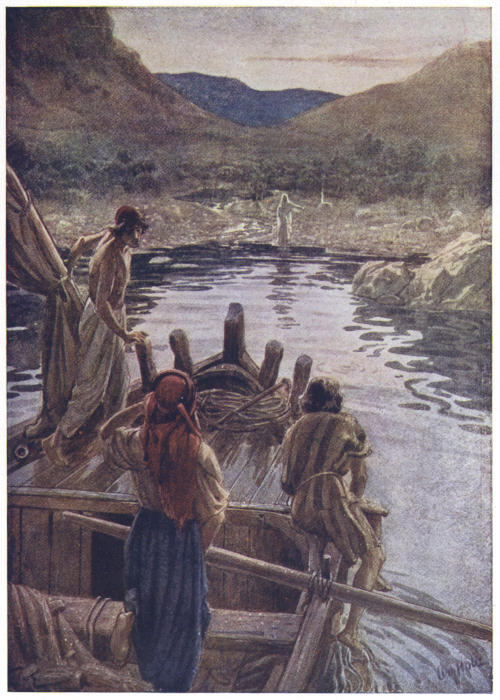

Herod Expecteth to be Amused

Then said Pilate to the chief priests and to the people, I find no

fault in this man. And they were the more fierce, saying, He stirreth

up the people, teaching throughout all Jewry, beginning from Galilee

to this place. When Pilate heard of Galilee, he asked whether the

man were a Galilæan. And as soon as he knew that he belonged unto

Herod’s jurisdiction, he sent him to Herod, who himself also was at

Jerusalem at that time. And when Herod saw Jesus, he was exceeding

glad: for he was desirous to see him of a long season, because he had

heard many things of him; and he hoped to have seen some miracle

done by him. Then he questioned with him in many words; but he

answered him nothing. And the chief priests and scribes stood and

vehemently accused him. And Herod with his men of war set him at

nought, and mocked him, and arrayed him in a gorgeous robe, and sent

him again to Pilate.—St. Luke xxiii: 4-11.

NOTE BY THE ARTIST

While in residence in Jerusalem, Herod Antipas occupied the ancient

palace of the Hasmonæan kings, situated on the western hill, not far from

that built by Herod the Great. A weak, cruel sensualist, Antipas, like other

princelings of his family, affected the dress and manners and the refined

luxury of the Greeks. Blasé and wearied doubtless with the monotonous

pleasures of the dissolute court, he welcomed the excitement promised by the

appearance of Jesus at his judgment-seat, anticipating that the prisoner

would thankfully purchase his life at the cost of amusing him and his

courtiers by some display of the magical power with the possession of which

rumor had credited him. Herod was devoted to hunting and had special

hunting grounds near the Lake of Gennesaret, so a favorite hound is appropriately

introduced.

63

[28]

[29]

THE BETRAYAL AND DESERTION

One of the darkest chapters in the history

of our Saviour’s life is this now before

us. Here we see him betrayed into the hands

of his enemies by one of his disciples and deserted

by all the rest.

In studying this subject, we may look at the

history of the betrayal and desertion, and then

consider some of the lessons that it teaches.

The man who committed this awful crime

was Judas Iscariot. He was one of the twelve

whom Jesus chose, in the early part of his ministry,

to be with him, all the time, to see all the

mighty works that he did, and to hear all that

he said in private as well as in public. He is

called Judas Iscariot, to distinguish him from

another of the disciples of the same name, viz.,

Judas, the brother of James. Different explanations

have been given of the meaning of this

name Iscariot. The most likely is, that it was[30]

used to denote the place of his birth. If this be

so, then it was written at first, Judas-Ish-Kerioth—which

means a man of Kerioth. And then

this would show us that he belonged to a town

in the southern part of Judah, called Kerioth.

We know nothing about Judas before we

hear him spoken of as one of the twelve apostles.

In the different lists of the names of the

apostles, he is always mentioned last, because of

the dreadful sin which he finally committed.

When his name is mentioned he is generally

spoken of as “the traitor”—or as the man

“which also betrayed him.” Jesus knew, of

course, from the beginning, what kind of a man

Judas was, and what he would do in the end.

But, we have no reason to suppose that Judas

himself had any idea of committing this horrible

crime when he first became an apostle; or

that the other apostles ever had the least suspicion

of him. There can be no doubt that he

took part with the other apostles when Jesus

sent them before his face to “preach the gospel

of the kingdom,” and to perform “many mighty

works.” Yes, Judas, who afterwards betrayed

his Master, preached the gospel and performed

miracles in the name of Jesus. His fellow-disciples,

so far from suspecting any harm of[31]

him, made him the treasurer of their little

company, and let him “have the bag” and

manage their money affairs. And this, may

have been the very thing that ruined him.

The first time that we see anything wrong in

Judas is at the supper given to our Lord at

Bethany. We read about this in St. John 12:

1-9. On this occasion, Mary, the sister of Lazarus,

brought a very precious box of ointment,

and anointed the feet of Jesus with it. Judas

thought this ointment was wasted, and asked

why it had not been sold for three hundred

pence, and given to the poor. This would be

about forty-five or fifty dollars of our money.

It is added—“This he said, not because he cared

for the poor; but because he was a thief, and

had the bag, and bore what was put therein.”

None of his disciples suspected Judas of being a

thief at this time. These words were added,

long after the death of Judas, when his true

character was well known.

But, when Jesus rebuked Judas for finding

fault with Mary, and praised her highly for

what she had done, he was greatly offended.

And then, it seems, he first made up his mind

to do that terrible deed which has left so deep

and dreadful a stain upon his memory. For we[32]

read—St. Matt. xxvi: 14-16—“Then one of the

twelve, called Judas Iscariot, went unto the

chief priests and said unto them, What will ye

give me, and I will deliver him unto you? And

they covenanted with him for thirty pieces of

silver. And from that time he sought opportunity

to betray him.” The paltry sum for

which Judas agreed to betray his Master was

about fifteen dollars of our money—the price of

a common slave.

Very soon after this Jesus met his disciples in

that upper chamber of Jerusalem, to eat the

Passover together for the last time. And Judas

came with them. How could the wretched

man venture into the presence of Jesus, when

he had already agreed to betray him?

But Jesus knew all about it. How startled

Judas must have been when he heard Jesus

say before them all—“One of you shall betray

me.” It is probable that Jesus said this to

drive Judas out from his presence, for it must

have been very painful to him to have him

there. And, after Jesus had given the sop to

Judas, to show by this that he knew who the

traitor was, we read that—“Satan entered into

him. Then Jesus said unto him, That thou

doest do quickly.” Then he “went immediately[33]

out;” and hastened to the chief priests to

make arrangements for delivering Jesus unto

them.

It is clear, I think, from this that Judas was

not present while Jesus was instituting the

Lord’s Supper. It must have been a wonderful

relief to Jesus when Judas left their little company.

And we are not surprised to find it written—“When

he was gone out Jesus said, Now

is the Son of man glorified, and God is glorified

in him,” St. John xiii: 31. Then followed

the Lord’s Supper; and the glorious things

spoken of in the 14th, 15th, and 16th chapters

of St. John, and the great prayer in the 17th

chapter. After this came the agony in the

garden of Gethsemane.

Just as this was over, Judas appeared with the

band of soldiers and servants of the chief priests

“with lanterns, and torches, and weapons.”

Jesus went forth to meet them, and asked whom

they were seeking. They answered, “Jesus of

Nazareth. Jesus saith unto them, I am he. As

soon as he had said unto them I am he, they

went backward and fell to the ground.” Then

Judas came to Jesus according to the signal he

had given them, and said, Hail, Master, and

kissed him. But Jesus said unto him, Judas,[34]

betrayest thou the Son of man with a kiss?

Then Peter drew his sword to defend his Master,

and struck a servant of the high-priest, and cut

off his right ear. Jesus touched the ear, and

healed it; and told Peter to put up his sword.

Then they came to Jesus and bound him, and

led him away to the high-priest; and it is added:

“Then all the disciples forsook him and fled.”

He was betrayed by one of his own disciples

and forsaken by all the rest.

Nothing is said about Judas during the time

of the trial of Jesus. Some suppose that he expected

our Lord would deliver himself out of

the hands of his enemies. We have no authority

for thinking so. But, when he found, at last,

that Jesus was condemned and was really to be

put to death, his conscience smote him for

what he had done. He brought back the thirty

pieces of silver—the beggarly price he had received

for betraying his Master—and threw

them down at the feet of the chief priests, saying—“I

have sinned, in that I have betrayed

the innocent blood. And they said—What is

that to us? See thou to that. And he went

and hanged himself.”

This was the end of the wretched man, so

far as this world is concerned. And such is[35]

the history of the betrayal and desertion of

Jesus.

We might refer to many lessons taught us by

this sad history, but we shall speak of only four.

Two of these relate to Jesus, and two of them

to Judas.

One of the lessons about Jesus, taught us here,

refers to—the loneliness of his sufferings.

We all know how natural it is, when we are in

trouble, to desire to have one near who loves us.

The very first thing a child does when worried

about anything is to run to its mother and throw

itself into her loving arms. It would almost break

the child’s heart if it could not have its mother’s

presence and gentle sympathy at such a time.

And it is the same when we grow older. We

naturally seek the company of our dearest

friends in times of trouble. And it adds greatly

to our suffering if we cannot have those we

love near us when we are in sorrow. But, in

the history of our Saviour’s betrayal and desertion,

we see how it was with him. In the midst

of his great trouble, when the wrath of God,

occasioned by our sins, was pressing heavily

upon him, he was betrayed into the hands of

his enemies by one of the little band of his

own chosen followers. How much this must[36]

have added to his sorrow! And if the rest of

his apostles had only stood by him faithfully,

as they had promised to do, during that night

of sorrow, it would have been some comfort to

him. But they did not. As soon as they saw

the traitor Judas deliver him into the hands of

his enemies, we read these sad, and melancholy

words, “Then all the disciples forsook him, and

fled!” How hard this must have been for

Jesus to bear! The cup of his sorrows was full

before; this must have made it overflow. He

knew it was coming. For, not long before, he

had told them that “the hour was coming,

when they would be scattered, and leave him

alone.” This shows how deeply he felt, and

feared this loneliness. Seven hundred years

before he came into our world, the prophet

Isaiah represented him as saying—“I have trodden

the wine-press alone,” chap. lxiii: 3. And

this was what he was doing now. In the midst

of the multitudes he came to save he was left—alone.

There was not an earthly friend to stand

by him—to speak a kind word to him—or to

show him any sympathy in this time of his

greatest sorrow. The only comfort left to him

was the thought that his Father in heaven had

not forgotten him.

[37]

When he spoke of his disciples leaving him

alone, he said, “And yet, I am not alone, because

the Father is with me.” St. John xvi: 32.

Jesus never forgets how lonely he felt at this

time; and he loves to come near and comfort

us when we are left alone. We should always

remember at such times how well able he is to

help and comfort us.

Here are some simple illustrations of the

blessing which those find who look to Jesus in

their loneliness.

An aged Christian was carried to a consumptives’

hospital to die. He had no relation or

friend to be near him except the nurse and the

doctor. Yet he always seemed bright and happy.

The doctor, in talking with him one day, asked

him how it was that he could be so resigned and

cheerful? His reply was—“When I am able to

think, I think of Jesus; and when I am not able

to think of him, I know he is thinking of me.”

And this was just the way King David felt

when he said, “I am poor and needy; yet the

Lord thinketh upon me.”

“Not Alone.” Little Bessie was sitting on

the piazza. The nurse came in and found her

there. “Ah! Bessie dear, all alone in the dark,”

said the nurse, “and yet not afraid?”

[38]

“No, indeed,” said little Bessie, “for I am not

all alone. God is here. I look up and see the

stars, and God seems to be looking down at me

with his bright eyes.”

“To be sure,” said the nurse, “but God is up

in the sky, and that is a great way off.”

“No,” said Bessie; “God is here too; sometimes

He seems to be clasping me in his arms,

and then I feel so happy.”

“The Help of Feeling Jesus Near.” There

was a poor man in a hospital. He was just

about to undergo a painful and dangerous

operation. They laid him out ready, and the

doctors were about to begin, when he asked

them to wait a moment. “What shall we wait

for?” was the inquiry of one of the doctors.

“Oh, wait a moment,” said he, “till I ask the

Lord Jesus Christ to stand by my side. I know

it will be dreadful hard to bear; but it will be

such a comfort to think that Jesus is near me.”

One thing we are taught by the betrayal and

desertion of Christ, is the loneliness of his

sufferings.

Another thing, taught us by this part of our

Saviour’s history is—his willingness to suffer.

We often make up our minds to suffer certain

things, because we have no power to help it.[39]

But it was not so with Jesus. He had power

enough to have saved himself from suffering,

if he had chosen to do so. Sometime before

this, when he was speaking to his disciples

about his death, or, as he called it, laying down

his life, he said—“No man taketh it from me,

but I lay it down of myself. I have power to

lay it down, and I have power to take it again.”

John x: 18. And he showed plainly what his

power was at the very time of his betrayal.

When his enemies came to take him, he “went

forth, and said unto them, Whom seek ye?

They answered him, Jesus of Nazareth. Jesus

saith unto them, I am he.” John xviii: 4. But

he put such wonderful power into these simple

words—“I am he”—that, the moment they

heard them, the whole multitude, soldiers, servants,

and all, fell to the ground before him.

It was nothing but the power of Jesus which

produced this strange effect. It seems as if

Jesus did this, on purpose to show that the

mighty power by which he had healed the sick,

and raised the dead, and cast out devils, and

walked on the water, and controlled the stormy

winds and waves, was in him still. He was not

taken by his enemies because he had no power

to help himself. The same power which made[40]

his enemies fall to the ground with a word

could have held them there while he walked

away; or could have scattered them, as the chaff

is scattered by the whirlwind; or could have

made the earth open and swallow them up.

But he did not choose to exercise it in any of

these ways. He was willing to suffer for us;

and so he allowed himself to be taken.

As the Jews were seizing him Peter drew his

sword, and smote one of the servants of the

high-priest, and cut off his right ear. Jesus

touched the ear, and healed it, in a moment,

thus showing again what power he had. Then

he told Peter to put up his sword, and said—“Thinkest

thou that I cannot now pray to my

Father, and he shall presently give me more

than twelve legions of angels?” St. Matt. xxvi:

53. A full Roman legion contained six thousand

men. Jesus had power enough in his own

arm to keep himself from being taken, if he

had chosen to use it. And more than seventy

thousand angels would have flown with lightning

speed to his deliverance, if he had but

lifted his finger; or said—“come.” There was

so much power in himself, and so much power

in heaven, at his command, that all the soldiers

Rome ever had could not have taken him,[41]

unless he had been willing to be taken. But

he was willing. And when they came to crucify

him, all the nails ever made could not

have fastened him to the cross, unless he had

been willing to be fastened there. But his

wonderful love for you and for me and for a

world of lost sinners, made him willing to be

fastened there, to suffer and to die, that our

sins might be pardoned and that we might

enter heaven.

And it is the thought of this amazing love of

Christ, making him willing to suffer for us,

which gives to the story of the cross the marvellous

power it has to melt the hardest hearts

and win the worst of men to his service. There

is a power in love to do what nothing else can

do,—to make men good and holy. And this is

what we are taught when told that—“Christ

suffered for sins, the just for the unjust, that he

might bring us to God.” I. Peter iii: 18. And

when we find people acting in this way towards

each other in everyday life it has just

the same effect. Here is an illustration of what

I mean. We may call it:

“The Power of Love; or, The Just for the

Unjust.” In a town near Paris, is a school for

teaching poor homeless boys who are found[42]

wandering about the streets of that city and are

growing up in idleness and crime.

When one of the boys breaks the rules of the

school and deserves punishment, the rest of the

school are called together, like a jury, to decide

what shall be done with the offender. One of

the punishments is confinement for several days

in a dungeon, called “the black-hole.” The prisoner

is put on a short allowance of food, and, of

course, forfeits all the liberties of the other boys.

After the boys have, in this way, passed sentence

on one of their companions and the

master approves of it, this question is put to the

rest of the school:—“Will any of you become

this boy’s substitute? i. e., take his place, and

bear his punishment, and let him go free?”

And it generally happens that some little friend

of the criminal comes forward and offers to

bear the punishment instead of him. Then the

only punishment the real offender has to bear

is to carry the bread and water to his friend as

long as he is confined in the dungeon. In this

way, it generally happens that the most stubborn

and hard-hearted boys are melted down,

by seeing their companions willingly suffering

for them what they know they deserved to

suffer themselves.

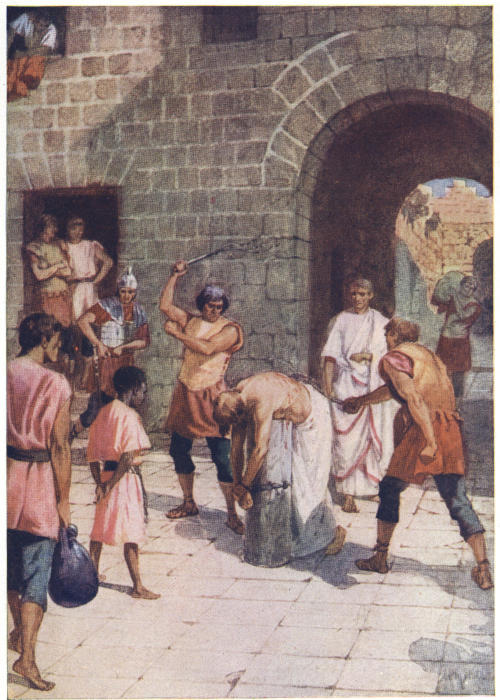

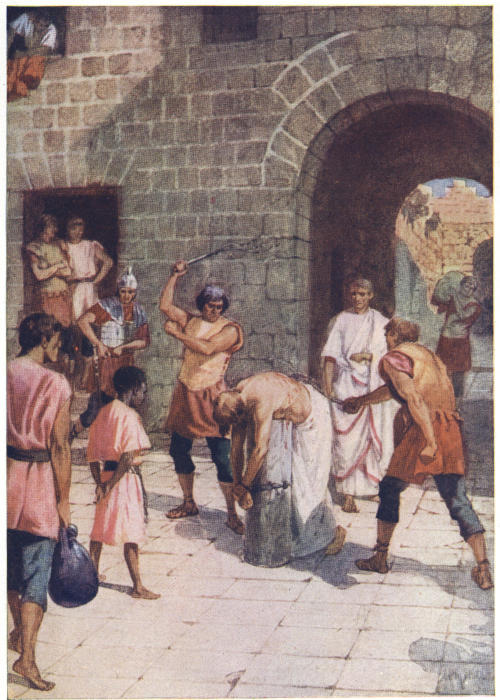

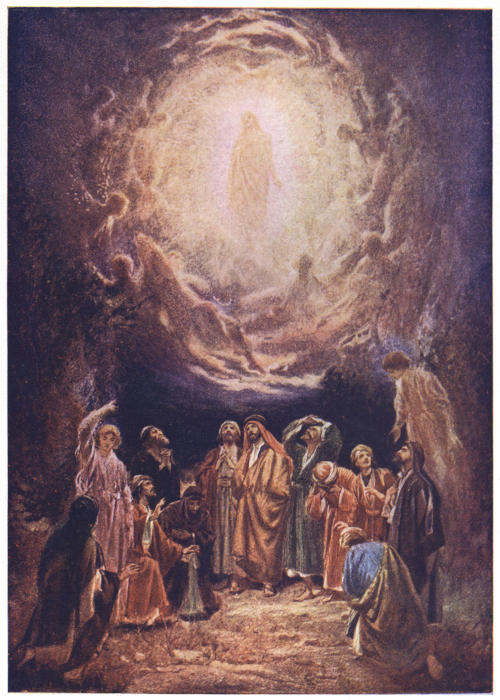

Jesus is Scourged

And Pilate, when he had called together the chief priests and the

rulers and the people, said unto them, Ye have brought this man unto

me, as one that perverteth the people: and, behold, I, having examined

him before you, have found no fault in this man touching those things

whereof ye accuse him. No, nor yet Herod: for I sent you to him;

and, lo, nothing worthy of death is done unto him. I will therefore

chastise him, and release him. (For of necessity he must release one

unto them at the feast.) And they cried out all at once, saying, Away

with this man, and release unto us Barabbas. (Who for a certain

sedition made in the city, and for murder, was cast into prison.)—Then

Pilate therefore took Jesus, and scourged him.—St. Luke xxiii: 13-19;

St. John xix: 1.

NOTE BY THE ARTIST

In endeavoring to apprehend, however imperfectly, the sufferings endured

by Jesus during this terrible day, there may be a tendency to under-estimate

the significance of one detail which is only incidentally mentioned by the evangelists,

namely, the punishment of scourging. But this was nevertheless so

barbarously cruel, that the mind recoils in horror from the effort to realize

the awful agony which it entailed. Bound in a crouching attitude to the

pillar of torment, the quivering flesh lacerated by the fragments of bone and

metal intertwisted with the thongs, few of its victims, save such as were in

perfect physical health, were able to survive the infliction of the scourge, but

perished either then and there, or shortly afterwards, from nervous shock or

from mortification of the wounds. Yet it was a punishment so common, such

an everyday occurrence, that the scourging of one more malefactor—Jesus by

name—the justice or injustice of whose sentence they neither knew nor cared

to know, would be regarded with utter indifference by the brutal soldiery

charged with its infliction.

64

[43]

Not long ago, a boy about nine or ten years

old, named Pierre, was received into this school.

He was a boy whose temper and conduct were

so bad that he had been dismissed from several

schools. He behaved pretty well at first; but

soon his bad temper broke out, and one day he

quarrelled with a boy about his own age, named

Louis, and stabbed him in the breast with a

knife.

Louis was carried bleeding to his bed. His

wound was painful, but not dangerous. The

boys were assembled, to consult about what

was to be done with Pierre. Louis was a great

favorite with the boys, and they all agreed at

once that Pierre should be turned out of the

school and never allowed to come back.

This was a very natural sentence under the

circumstances, but the master thought it was

not a wise one. He said that if Pierre was

turned out of school, he would grow worse and

worse, and probably end his life on the gallows.

He asked them to think again. They then

agreed upon a long imprisonment, without

saying how long it was to be. They were asked

as usual, if any one was willing to go to prison

instead of Pierre. But no one offered and he

was marched off to prison.

[44]

After some days, when the boys were all together,

the master asked again if any one was

willing to take Pierre’s place. A feeble voice

was heard, saying—“I will.” To the surprise of

every one this proved to be Louis—the wounded

boy, who was just getting over the effect of his

wound.

Louis went to the dungeon and took the

place of the boy who had tried to kill him;

while Pierre was set at liberty. For many days

he went to the prison carrying the bread and

water to Louis, but with a feeling of pride and

anger in his heart.

But at last he could bear it no longer. The

sight of his kind-hearted, generous friend, still

pale and feeble from the effects of his wound,

pining in prison—living on bread and water—and

willingly suffering all this for him—who

had tried to murder him—this was more than

he could bear. His fierce temper and stubborn

pride broke down under it. The generous love

of Louis had fairly conquered him. He went

to the master, fell down at his feet, and with

bitter tears confessed his fault, begged to be forgiven,

and promised to be a good boy.

He kept his promise, and became one of the

best boys in the school.

[45]

And so it is the love of Christ in being willing

to suffer for us that wins the hearts and lives of

men to him, and gives to the story of the cross

all its power.

The willingness of Christ to suffer is the

second thing taught us by the history of the

betrayal and desertion.

These are the two things taught us about

Jesus by this history: his loneliness in suffering,

and his willingness to suffer.

But, there are two things taught us about

Judas, also, by this history.

One of these is—the power of sin.

The sin of Judas was covetousness, or “the

love of money.” The apostle Paul tells us that

this—“is the root of all evil.” I. Tim. vi: 10.

The little company of the apostles made Judas

their treasurer. He carried the purse for them.

He received the money that was contributed for

their expenses, and paid out what was needed

from day to day. We may suppose that, soon

after his appointment to this office, he found

himself tempted to take some of this money

for his own use. Perhaps he only took a penny

or two, at first, but then he soon went on to

take more. Now, if he had watched and striven

against this temptation, at the very first, and[46]

had prayed for strength to resist it, what a different

man he might have been! There is an

old proverb which says—“Resist the beginnings.”

Our only safety is in doing this. Judas

neglected to resist the beginning of his temptation

and the end of it was his ruin. We never

can tell what may come out of one sin that is

not resisted.

If you want to sink a ship at sea, it is not

necessary to make half a dozen big holes in her

side; one little hole, which you might stop

with your finger, if left alone, will be enough

to sink that ship. Judas gave himself up to the

power of one sin, and that led him on to betray

his Master.

Let us look at some illustrations of the power

of one sin.

“Clara’s Obstinacy.” Little Clara Cole was

saying her prayers one evening before going to

bed. Part of her evening prayer was the simple

hymn—“And now I lay me down to sleep.”

When she came to the last line she stopped

short and would not say it. “Go on, my dear,

and finish it,” said her mother. “I can’t,” she

said, although she knew it perfectly well, and

had said it hundreds of times before. “Oh,

yes! go right on, my child.”

[47]

“No; I can’t.” “My dear child, what makes

you talk so? Say the last line directly.”

But, in spite of her mother’s positive commands

and loving entreaties, Clara was obstinate,

and would not do it. “Very well,” said

Mrs. Cole at last: “you can get into bed; but

you will not get up till you have said that line.”

Next morning Mrs. Cole went into Clara’s

room as soon as she heard her stir. “Now,

Clara,” she said pleasantly, “say the line, and

jump up.”

“I can’t say it,” said Clara, obstinately, and

she actually lay in bed all that day, and part of

the next rather than give up. The second day

was her birthday and a number of little girls

had been invited, in the evening, to her birthday

party. That little, strong, cruel will of hers

held out till three o’clock; then she said, “I

pray the Lord my soul to take,” and bursting

into tears asked her mother’s forgiveness.

How much power there was in that one sin!

No one can tell what trouble it might have

caused that poor child if she had not been

taught to conquer it. But after that it never

gave her much trouble.

“One Drop of Evil.” “I don’t see why you

won’t let me play with Willie Hunt,” said[48]

Walter Kirk, with a frown and a pout. “I know

he doesn’t always mind his mother. He smokes

segars, and once in a while he swears just a

little; but I’ve been brought up better than

that; he won’t hurt me. I might do him some

good.”

“Walter,” said his mother, “take this glass

of pure water, and put just one drop of ink

into it.”

Walter did so, and then in a moment exclaimed,

“Oh! mother, who would have thought

that one drop would blacken a whole glass so!”

“Yes, it has changed the color of the whole.

And now just put one drop of clear water in it,

and see if you can undo what has been done.”

“Why, mother, one drop, or a dozen, or fifty

won’t do that.”

“That’s so, my son; and that is the reason

why I don’t want you to play with Willie Hunt.

For one drop of his evil ways, like the drop of

ink in the glass, may do you harm that never

can be undone.”

Here we see the power of a single sin.

“One Worm Did It.” One day a gentleman

in England, went out with a friend who was

visiting him, to take a walk in the park. As

they were walking along, he drew his friend’s[49]

attention to a large sycamore tree, withered

and dead.

“That fine tree,” said he, “was killed by a

single worm.”

In answer to his friend’s inquiries, he said:

“About two years ago, that tree was as healthy

as any in the park. One day I was walking out

with a friend, as we are walking now, when I

noticed a wood-worm about three inches long

forcing its way under the bark of the tree. My

friend, who knew a great deal about trees, said—‘Let

that worm alone, and it will kill this tree.’

I did not think it possible, and said—‘well,

we’ll let the black worm try, and see what it

can do.’”

The worm tunnelled its way under the bark.

The next summer the leaves of the tree dropped

off, very early. This year the tree has not put

out a single green leaf. It is a dead tree. That

one worm killed it.

Here we see the power of one sin. The third

lesson taught us by the history of the betrayal

and desertion, is—the power of sin.

The fourth lesson taught us by this history is—the

growth of sin.

Solomon says, “The beginning of strife”—and

the same is true of all sin—“is as when one[50]

letteth out water.” Prov. xvii: 14. There is a

bank of earth that keeps the water of a mill-dam

in its place. You notice one particular

spot where the bank seems weak. The water

is beginning to make its way through. At first,

it only just trickles down, drop by drop. By

and by, the drops come faster. Now, they run

into each other, and make a little rill. Every

moment the breach grows wider and deeper,

till, at last, there is a roaring torrent rushing

through that nothing can stop.

Every sin is like a seed. If it be planted in the

heart and allowed to spring up, no one can tell

what it will grow into. Suppose, that you and

I knew nothing about the growth of trees. We

are sitting under the wide-spreading branches

of a vast oak tree. A friend picks up a tiny,

little acorn, and holding it up before us, says—“This

giant tree, under whose shade we are

sitting, has all grown out of a little acorn, like

this.” It would seem impossible to us. We

could hardly be made to believe it. But we

need no argument to prove this. We know it

is so.

But the growth of sin in the hearts and lives

of men is quite as surprising as the growth of

trees in the forest. We see this in the case of[51]

Judas. Suppose that we could have seen him

when he first let his love of money lead him to

do wrong. Perhaps he only stole a penny or

two, at first. That was not much. And then,

suppose we had not seen Judas again till the

night in which he had made up his mind to

commit that greatest and most awful of all sins—the

sin of betraying his Master! what a wonderful

change we should have seen in him!

The growth of a river from a rill—of a giant

oak from a tiny acorn—would not be half so

surprising as the monstrous growth in wickedness

that we should have seen in Judas. When

we saw him committing his first sin, he was

like a little child. When we saw him committing

his last awful sin—the child had sprung

up into a huge, horrible giant. Jesus said he

had become a devil. St. John vi: 70. How

fearful it is to think of such growth in wickedness!

And yet, if we allow the seed of sin to

be sown in our hearts, and to spring up there,

we cannot tell but what its growth may be as

fearful in us as it was in Judas.

Let us look at some illustrations of the growth

of sin.

“The Growth of Lying.” Some time ago a

little boy told his first falsehood. It was like[52]

a solitary little thistle seed, sown in the mellow

soil of his heart. No eye but that of God saw

him as he planted it. But, it sprung up—O,

how quickly! and, in a little time, another seed

dropped from it into the ground, and then another,

and another, each in its turn bearing

more and more of those troublesome thistles.

And now, his heart is like a field of which the

weeds have taken entire possession. It is as

difficult for him to speak the truth as it is for

the gardener to clear his land of the ugly thistles

that have once gained a rooting in the soil.

“The Snake and the Spider.” A black snake,

about a foot long, lay sunning itself on a garden-bed

one summer’s day. A spider had hung out

his web on the branches of a bush, above where

the snake lay. He saw the huge monster lying

there, for huge indeed he was compared to the

little spider, and he concluded to take him

prisoner. But, you ask, is not the snake a thousand

times stronger than the spider? Certainly

he is. Then how can he take him prisoner?

Well, let us see how he did it. The spider spun

out a fine, slender thread. He slipped down,

and touched the snake with it. It stuck. He

took another, and touched him with that, and

that stuck too. He went on industriously. The[53]

snake lay quiet. Another, and another thread,

was fastened to him, till there were hundreds

and thousands of them. And, by and by, those

feeble threads, not one of which was strong

enough to hold the smallest fly, when greatly

multiplied, were strong enough to make the

snake a prisoner. The spider webbed him

round and round, till, at last, when the snake

tried to move, he found it was impossible. The

web had grown strong out of its weakness. By

putting one strand here, and another there, and

drawing, first on one, and then on another, the

spider had the snake bound fast, from head to

tail, to be a supply of food for himself and

family for a long while.

And so, if we give way even to little sins,

they may make us their prisoner as the spider

did the snake, and before we are aware of it, we

may be bound hand and foot and unable to

help ourselves.

“Sin Like a Whirlpool.” The Columbia river,

in Oregon, has a great bend in it at one place

where it passes through a mountain range.

When the water in the river is high there is a

dangerous whirlpool in this part of the river.

An officer connected with the United States

Exploring Expedition was going down this[54]

river, some years ago, in a boat which was

manned by ten Canadians. When they reached

this bend in the river, they thought the water

was so low that the whirlpool would not be

dangerous. So they concluded to go down the

river in the boat, as this would save them the

labor of carrying the boat with its baggage

across the portage to the place where they

would take the river again below the rapids.

But, the officer was put on shore, to walk across

the portage. He had to climb up some high

rocks. From the top of these rocks he had a

full view of the river beneath and of the boat

in her passage. At first, she seemed to skim

over the waters like a bird. But, soon he saw

they were in trouble. The struggles of the

oarsmen and the shouts of the man at the helm

showed that there was danger from the whirlpool,

when they thought there would be none.

He saw the men bend on their oars with all

their might. But, in spite of all, the boat lost

its straightforward course, and was drawn into

the whirl. It swept round and round, with increasing

force and swiftness. No effort they

could make had the least control of it. A few

more turns, each more rapid than the rest, and

at last, the centre was reached; and the boat,[55]

with all her crew, was drawn into the dreadful

whirlpool, and disappeared. Only one of the

ten bodies was found afterwards, in the river