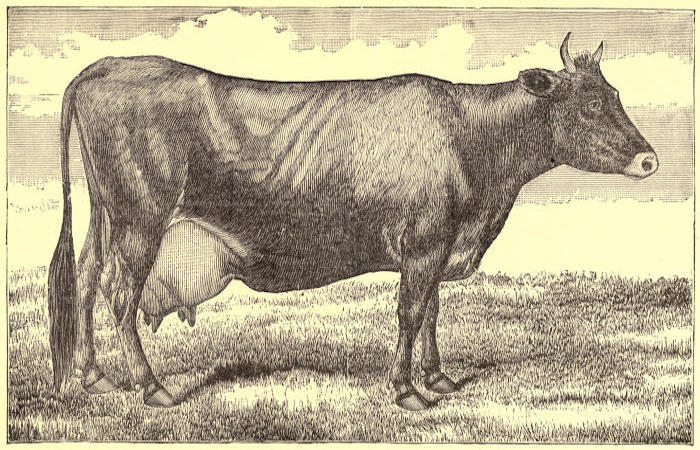

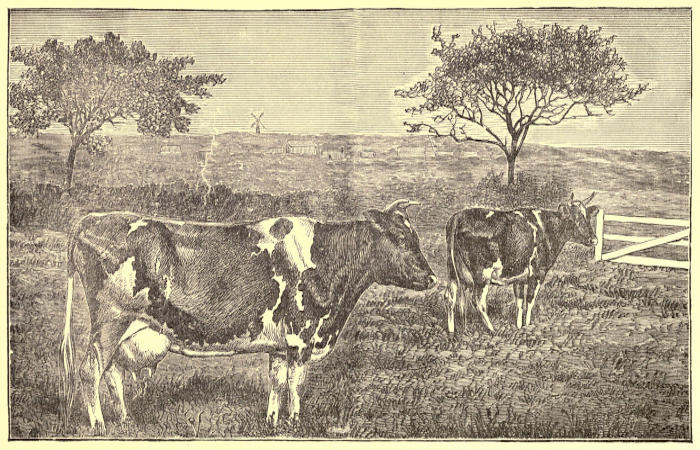

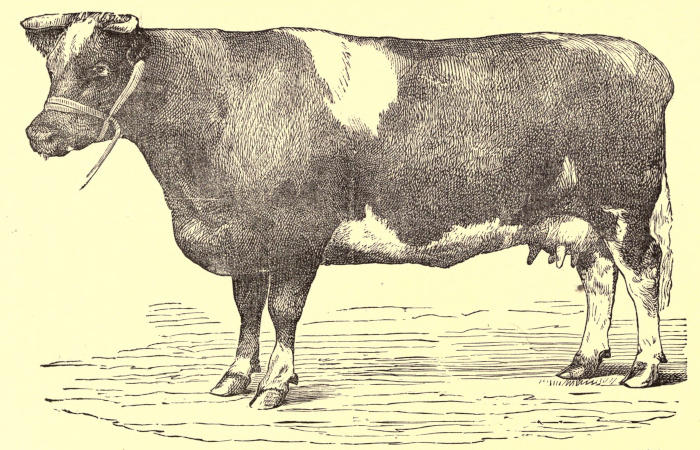

THE FAMOUS JERSEY COW “EUROTAS” (2.454). (Frontispiece.)

Title: Keeping one cow

Author: Various

Release date: May 15, 2022 [eBook #68093]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Orange Judd Company, 1880

Credits: deaurider and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

THE FAMOUS JERSEY COW “EUROTAS” (2.454). (Frontispiece.)

KEEPING ONE COW.

BEING THE EXPERIENCE OF A NUMBER OF PRACTICAL WRITERS,

IN A CLEAR AND CONDENSED FORM,

UPON THE

Management of a Single Milch Cow.

ILLUSTRATED.

NEW YORK:

ORANGE JUDD COMPANY,

751 BROADWAY.

1884.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1880, by the

ORANGE JUDD COMPANY,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

We have now, according to the last census, a population pressing close upon fifty Millions. Every one of this vast number is individually interested in the milk question. What is true of perhaps no other element of food and nourishment, milk is consumed in some form by all, old and young. It is because of this necessarily universal personal interest in milk that the publishers offer this volume which aims to show all how to obtain the best milk, plenty of it, and at the cheapest rates. The book embraces the experience and advice of able, well known writers—such, for example, as Professor Slade, of Harvard College, and Henry E. Alvord—elicited in response to propositions presented by the Publishers for articles upon the subject. The editorial supervision of the work has been in the hands of Col. Mason C. Weld and Professor Manly Miles—recognized authorities on Dairy Matters—who would have included many other valuable and interesting papers submitted, were it not that they would have made the volume too bulky. Mr. Orange Judd has added a leaf from his personal experience.

The topics treated are only those legitimately connected with the subject, yet they cover a wide field, and will prove of great interest to all occupied in the culture of the soil, while as a handbook and guide to those who keep one or more family cows it must be of almost daily practical use. The prominent subjects, such as soiling, stabling, care of manure, the tillage of the soil, the cultivation of various crops, care of the cow and of the calf, are each treated in detail, and yet there is so great a variety and such genuine personal experience and sincere conviction on the part of each writer, that his or her way is the best way—as indeed it may be, under the circumstances—that there is little or nothing of sameness or repetition in the book, but the reader’s interest is sustained to the last.

Every farmer is ordinarily supposed to keep several cows, and there is no reason why most families in villages and very many in cities should not possess at least one. Good milk affords the best of nourishment for young children, and goes a long way in saving butchers’ bills, and in the preparation of palatable nourishing food of many varieties. Two to five families, according to age and number, can readily unite in having one cow kept, dividing the milk and expenses, and thus always have good, pure, rich milk at very moderate cost. The suitable refuse from the kitchens of three or four families would very much reduce the cost of purchased food. In rural villages, summer pasturage can be obtained near at hand, which, with a daily feed of good meal will furnish a large supply of rich milk at a low cost. A boy can be secured at a small price to drive the cow to the pasture in the morning, and return her at night to the stable. A stable or stall can always be obtained at a trifling rent, and be kept clean. There are plenty of gardeners or farmers who will gladly take the manure away so frequently as to prevent it being a nuisance, or disagreeable.

We have no doubt that all residents of villages, manufacturing towns, etc., can, by arrangements like the above, secure an abundant supply of pure, rich, fresh, healthful milk at less than three cents per quart, and at the same time add greatly to their home comforts, and preserve the health if not the lives of their little ones.

In February, 1880, the publishers of this volume offered prizes for three essays on keeping one cow, indicating at the same time their scope. Some extracts from the explanatory remarks accompanying this offer may fitly outline an introduction to the work.

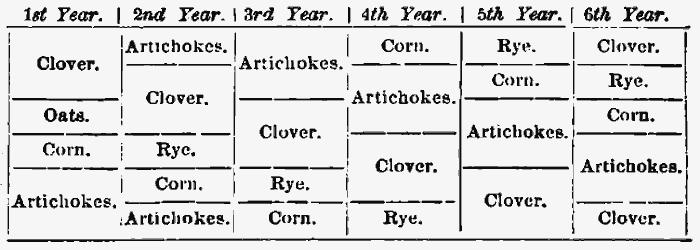

The number of persons who possess but one cow is far larger than those who have ten or more. No doubt many others, living outside of closely built cities, would gladly lessen the cost of supporting their families, and at the same time add to their comforts, and even luxuries, by keeping a cow, did they know how to keep one. There is a general notion that keeping a cow requires a pasture. If a pasture is not necessary, they do not know how to get along without one. Dairymen and farmers learn how to treat herds as a part of general farm management, or in books on the subject. There are books on cows, but none on[viii] one cow. It is not a question of dairy farming, but of dairy gardening. The offer was made to elicit information to enable one to keep a single cow with the best possible results. The main points to be considered are: the stabling or housing of the cow; the yard room she requires, and the storage or disposal of her manure; the least area of land that can be safely set apart for the support of the cow, and how can that land be best managed. It is to be assumed that the land will be made to produce all that it will profitably yield, which will bring up the question of manure and fertilizers, of course considering that produced by the cow herself. What proportion of the produce of the land is to be cured for winter? How much food must be bought, and what? How is the cow to be fed, and in every respect how treated so as to give the best returns to her owner? What should be done at calving time and afterwards? milking, etc. In short, the problem is—given a good cow, how to get the best possible returns from the least possible portion of the land through the agency of the cow.

This, we think, is satisfactorily answered, if not by any one writer, certainly by several combined.

We place as a frontispiece the portrait of a most famous and excellent cow—not so much for her beauty or on account of her breed, but as a model of a dairy cow, and one which may be carried in the mind when purchasing.

There are several ways of providing for the wants of a cow, but in all cases it is absolutely necessary, in order to obtain the best results, that certain rules be followed with regard to the treatment the cow receives. She must be fed and milked at regular times, be kept thoroughly clean, have plenty of fresh air and water, and her food composed of those substances that will keep her always in good condition, do away with the milk bill, reduce the grocer’s account, and contribute greatly to the health and comfort of the family. I have tried various things, and have found fresh grass or fodder, provender, bran, oil-cake, mangels, and hay, the best bill of fare for “Daisy” or “Buttercup.” Avoid brewer’s slops or grains as you would poison, for although they increase the flow of milk, it is thin and blue, the butter white and tasteless, and after a time the cow’s teeth will blacken and decay. I was told the other day by a very intelligent dairyman that after feeding his cows one season on brewer’s grains he was obliged to sell his whole herd.

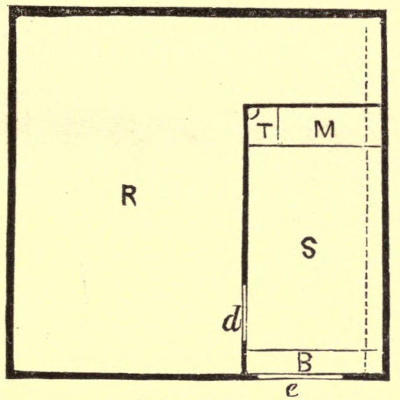

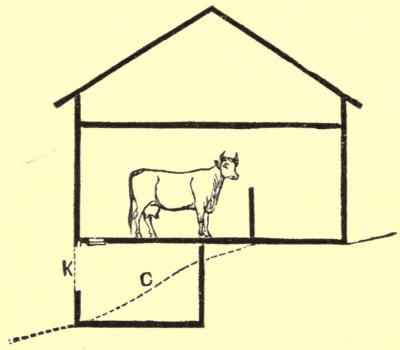

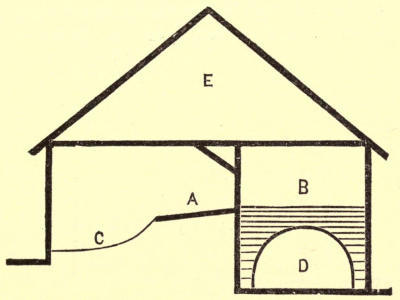

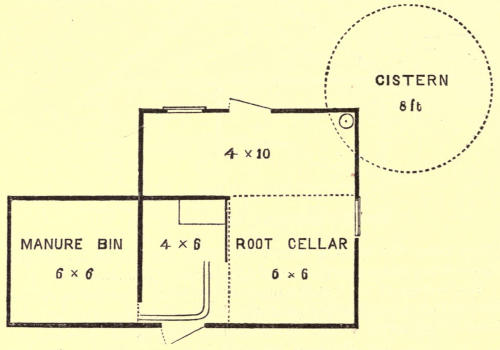

Mr. Geo. E. Waring, Jr., in his “Ogden Farm Papers,” says he expects to be able to feed a cow from May fifteenth to November fifteenth from half an acre of ground, but the average citizen had[10] better not attempt it, but keep his half acre to raise vegetables and fruit, buying the food required to keep his cow. A cow can be made very profitable if kept in the following way; First, as to the accommodation required, a yard fifteen feet by fifteen, and a stable or cow-shed arranged as in the following plan. A, manure shed; B, bin for dried earth; C, cow; D, store-room; E, window for putting in hay; F, door; G, trap to loft; H, feeding trough. Have her food provided as follows: into a common pail put one quart of provender (“provender” is oats and peas ground together, and can be purchased at any feed store), one-quarter pound of oil-cake, then fill the pail nearly full of bran and pour boiling water over the whole; stir well with a stick, and put it away covered with an old bit of carpet until feeding time; give her that mess twice a day. Have her dinner from June to November consist of grass or fodder cut and brought in twice a week by some farmer or market gardener in exchange for her manure and sour milk. In Montreal, grass and fodder are brought to market by the “Habatants,” and sold in bundles. As to quantity, a good big armful will be sufficient, and it is more healthful for the cow if it is a little wilted. In the winter hay and mangels are to be fed in place of the grass and fodder. She should also have salt where she can take a lick when so minded, and fresh water three times a day. The yard should be kept clean by scraping up the manure every morning into the little shed at the end of the stable.

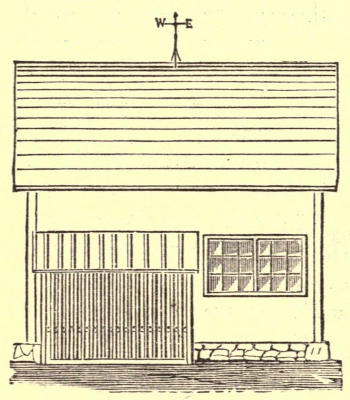

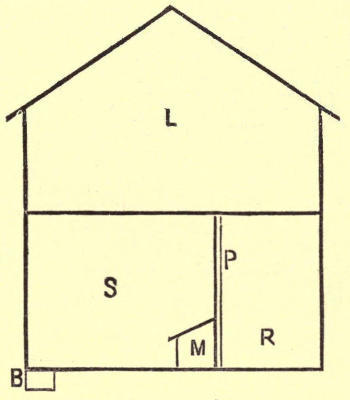

Fig. 1.—STABLE AND YARD.

The following table shows the food required to keep one cow through the entire year:

| Hay, the best, two tons, at $10 per ton | $20.00 |

| 200 pounds of Oil-cake, at $4 per 100 pounds | 8.00 |

| 800 pounds of Provender, at $1 per 100 pounds | 8.00 |

| Half a ton of Bran, at $12 per ton | 6.00 |

| One ton of Mangels | 5.00 |

| $47.00 |

Your cow will require the following “trousseau”:

| One five-gallon stone churn | $1.25 |

| One and a half dozen milk pans, at $2 | 3.00 |

| One milk pail and strainer | .60 |

| One butter bowl (wooden) | .50 |

| One paddle and print | .20 |

| Two wooden pails for feed | .40 |

| One card | .25 |

| $6.20 | |

| Cost of a good cow | 40.00 |

| Interest at 6 per cent | $3.69 |

Any ordinary family will take from a milkman at least one quart a day. We in Ottawa pay eight cents per quart, making per year (365 × 8,) $29.20.

It is a very poor cow that will not average five pounds of butter a week for forty weeks, and that at twenty-five cents per pound, that is 40 (weeks) × 5 (pounds), × 25 (cents), equals 50 (dollars).

So the account stands thus:

| Butter | $50.00 | ||

| Milk | 29.20 | ||

| $79.20 | |||

| Cost of food for one year | $47.00 | } | |

| Interest on cow and trousseau | 3.69 | } | 50.69 |

| Profit | $28.51 |

I have found that two acres of land is the least possible area that will provide cow-food for the entire year, and that should be divided thus: One acre for hay, the other for fodder and mangels. If you have no land already seeded down, plow up your acre, sow clover and timothy, six pounds, of each. In May, when the grass has fairly started, top-dress it with two bushels of land plaster; if you can apply it just before a rain it is the best time. The first year you will have all clover hay, and it must be cut before the second blossom comes; if not cut early enough, the stalks become tough and woody, and are wasted by the cow. The second year, if top-dressed in the fall with the manure collected during the summer, you will have a fine crop of timothy, and if the land was good for anything you can cut hay from it for three years by giving it a little manure every fall. As early as the ground will admit, sow some peas and oats; one bushel of each will plant one-third of an acre. Peas do well on old sod, and are the best crop to plant on new ground. In about six weeks you can commence cutting it for fodder, and it should give the cow two good[12] meals a day until corn comes in. L. B. Arnold, in “American Dairying,” says of corn: “When too thickly planted its stems and leaves are soft and pale, its juices thin and poor. If sown thin or in drills, so that the air and light and heat of the sun can reach it, and not fed until nearly its full size, it is a valuable soiling plant.” Now Mr. Waring, in “Farming for Profit,” says: “It is a common mistake when the corn is planted in drills to put in so little seed that the stalks grow large and strong, when they are neglected by the cattle, the leaves only being consumed. There should be forty grains at least to the foot of row, which will take from four to six bushels to the acre, but the result will fully justify the outlay, as the corn standing so close in the row will grow fine and thick.” My experience tells me that Mr. Waring is right; any way, my cow will not eat the coarse stalks which will grow when the corn is planted too thin.

The one-third acre reserved for mangels, must be the perfection of richness, well drained, and manured. If the soil is deep, you can plant them on the flat, but if the soil is shallow, plant them on ridges, the ridges thirty inches apart (I always plant them in that way); then thin out the plants to fifteen inches apart. Ten to twelve hundred bushels may be grown on an acre, but the ground must be properly prepared. In storing them, they require to be very carefully handled, as the least bruise hastens decay, and we want to keep them fresh and good until April, when our cow ought to give us a calf.

I thought I had tried almost everything relating to the care of cows, but when I undertook to wean a five-weeks’-old calf, I found my education in that respect sadly neglected. I asked a farmer’s wife how I was to manage. “Oh,” she said, “just dip your fingers in the milk, and let the calf suck them a few times, and it will soon learn to put its nose in the pail and drink.” It sounded simple enough, so I took my pail and started for the barn, where that wretched animal slopped me all over with milk, bunted me round and round the pen, until I was black and blue, sucked the skin off my finger, and wouldn’t drink. After trying at intervals for two days, the calf was getting thin, and so was I. In despair, I left the pail of milk, giving that calf a few words of wholesome advice. When I went back two hours after, the calf was standing over the empty pail, with an expression on its face, that I translated into an inquiry, as to why I hadn’t left that pail there before.[13] I have weaned several calves since then, but have never had any trouble. Leave them with the cow three or four days, then take a little milk and hold the calf’s nose in the pail; it must open its mouth or smother, and when once it tastes the milk, will soon learn to drink.[1] When it is a week old, commence feeding with oil-cake, skim-milk and molasses. Into an old two-pound peach can, I put one tablespoonful of oil-cake and one of molasses, fill up the can with boiling water, and set it on the stove until thoroughly cooked. That quantity will be its allowance for one day, mixed with skim-milk. The next week, give it that quantity at each meal, and the next week, twice that. The calf will then be four weeks old, and the butcher ought to give you a price for it that will pay for all trouble and the family milk bill while the cow was dry. It does not pay to raise calves where you only keep one cow. (Mr. Cochrane, the owner of the celebrated cow “Duchess of Airdrie,” told me the other morning that last year he sold a calf of her’s to an English gentleman for four thousand guineas (twenty thousand dollars). I think it would pay to have a wet nurse if one had a calf like that). A tablespoonful of lime-water put in the milk now and then will prevent the calf from “scouring,” a complaint very common among calves brought up by hand. I believe that winter rye makes a valuable soiling plant, but I have never tried it.

[1] It is better, as a rule, not to allow the calf to suck at all. Aptness in learning to drink is influenced by heredity. Calves from ancestors that have not been allowed to suck, learn to drink more readily than those which have been allowed to run with the dam.

I think it cruel to keep cows tied up all summer. They do not require much exercise, but fresh air they must have, and it is a great comfort to them to lick themselves, although they ought to be well curried every day. It is better to milk after feeding, as they stand more quietly. Don’t allow your milk-maid to wash the cow’s teats in the milk pail, a filthy habit much in vogue. Insist on her taking a wet cloth and wiping the cow’s bag thoroughly before she commences to milk. A cow ought to be milked in ten minutes, although the first time I undertook to milk alone, I tugged away for an hour. I knew how much milk I ought to have, and I was bound to get it. An old cow will eat more than a young one, but will give richer milk. If you can get a cow with her second calf, you can keep her profitably for five years, when she should be sold to the butcher. There is nothing that[14] will keep your cow-shed so neat, and add so much to the value of your manure pile, as a few shovelfuls of dry earth or muck thrown under the cow. It will absorb the liquid manure better than anything else. Don’t allow your milk pans to be appropriated for all sorts of household uses; you cannot make sweet, firm butter if the milk is put into rusty old tin. Skim the milk twice a day into the stone churn; add a little salt, and stir it well every time you put in fresh cream. Use spring water, but don’t allow ice to come in contact with the butter; it destroys both color and flavor. If your cream is too warm, the butter will come more quickly, but it will be white and soft. When the cream is so cold that it takes me half an hour to churn, I always have the best butter. Don’t put your hands to it, work out the buttermilk with a wooden paddle, and work in the salt with the same thing. There is an old saying that one quart of milk a day gives one pound of butter a week, and I think it’s a pretty fair rule, but don’t expect to buy a cow that will give you thirty quarts of milk a day. There are such cows I know, but they are not for sale. Be quite satisfied if your cow gives half that quantity. Place the cow’s food where she cannot step on it, but don’t put it high up; It is natural for them to eat with their heads down. I think it is better that the family cow should have a calf every year, provided you can have them come early in the spring or late in the autumn. As to the time that a cow should be dry, that depends much upon the way the cow was brought up. If she was allowed to go dry early in the season with her first calf, she will always do it. A cow being a very conservative animal, she should be milked as long as her milk is good. When she is dry, stop feeding the provender, bran, and oil-cake, and give her plenty of good hay, with some roots, until after she calves. The provender and oil-cake being strong food, are apt to produce inflammation and other troubles at calving time. You can feed turnips when she is dry, at the rate of two pails a day, cut up fine, of course, but don’t feed turnips when she is milking. I have tried every way to destroy the flavor of turnips in milk, but without success. I have boiled it, put soda in it, fed the cow after milking, but it was all the same—turnip flavor unmistakable—and as we don’t like our butter so flavored, I only feed turnips when the cow is dry.

The Rev. E. P. Roe in his delightful book called “Play and Profit in My Garden,” says: “If a family in ordinary good circumstances, kept a separate account of the fruit and vegetables bought and used during the year, they would, doubtless, be surprised[15] at the sum total. But if they could see the amount they could and would consume if they didn’t have to buy, surprise would be a very mild way of putting it.” The same rule applies to the keeping of a cow. We buy one quart a day and manage to get along with it. Our cow gives us ten to twenty quarts a day and we make way with the greater part of it. I think with a cow and a garden, one may manage to live, but life without either, according to my ways of thinking, would be shorn of many of its pleasures.

Instead of writing on how a cow might be kept, I propose simply to tell just how we manage our cow, what we feed her, how we procure that food; in fact everything relating to her care, so that any one can go and do likewise.

“Spot,” we call her, for she has a beautiful white spot in her forehead, is not a Jersey, for we can not afford to buy one at the prices at which they are held with us; nor is she a thorough-bred of any kind; yet she is a good cow, of medium size, fills a twelve-quart pail each night and morning, when her milk is in good flow, that raises a thick coat of rich cream, which, after been churned, furnishes all the butter needed for a family of six, and some to spare. Our place is small, only two acres, and a portion of this is covered by the dwelling, barn, poultry-house, etc. The fruit garden occupies about one-fourth of an acre, and from this portion nothing is grown to furnish food for “Spot.” Adjoining the barn there is half an acre of the land in good grass, or mostly clover, and every spring a quart of clover seed is sown, so as fast as the old plants die out, young ones take their places. A bushel of land plaster is sown on this when the grass begins to start in the spring. This plot produces a very heavy growth of grass and clover, enabling us to cut it three times each season; about the first of June, August, and of October. A coat of fine manure is always spread over the ground immediately after each mowing. The grass is mostly cured, and makes fine hay for winter feeding. Occasionally a small portion of the crop is used green for soiling. Besides the land occupied by buildings, fruit garden, and clover plot, there remains about one acre, which we call the garden. Here are grown all the vegetables for the family’s use, besides some to sell. About one-fourth of it is planted to Early Rose potatoes, and as soon as these are sufficiently ripe for use or market, they are dug, and sweet corn, in drills, for fodder, is sown upon the land. Another fourth of an acre is planted to sugar beets; the ground being very rich, the yield is always large; this last season (1879), though very dry, I harvested one hundred and seventy-eight bushels. Our cow is very fond of the beets, and I think there is nothing better to keep up a flow of milk, and they give it no bad flavor, as do turnips. An additional fourth of an acre is planted to sweet, or evergreen,[17] corn; as fast as the corn is picked for use or market, the green stalks are cut up, run through the cutting-box, and every particle of them consumed. As soon as the corn is all harvested, the ground it occupied is thoroughly fitted and manured, and then sown to winter rye, to be used for soiling the next spring, after which the ground is again prepared for corn. The remaining fourth acre is devoted to early peas, beans, cabbages and other garden vegetables. As soon as one crop is off, the ground is prepared, and something else is almost always planted or sown; consequently, on the most of this acre, two crops are produced each season, except where sugar-beets are grown, or late cabbages, which require the whole season to mature. With the clover on the half acre, and the forage crop and roots on the acre, we have not only had sufficient food for the cow the entire season, but have also kept our family horse, with the exception of one load of oat-straw purchased for three dollars, to mix in with the fodder corn; this is hard to cure sufficiently to keep bright and sweet through the winter, but by mixing a layer of corn-fodder, and a layer of straw, it all comes out nice and bright. Besides keeping both horse and cow, we have marketed from this little farm, in berries, vegetables, butter, eggs, poultry, and one fat hog, weighing, dressed, over three hundred pounds, four hundred and sixty-eight dollars’ worth of the above produce, keeping enough for our own use, and salting down one barrel of pork.

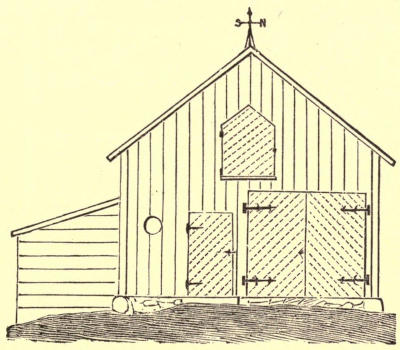

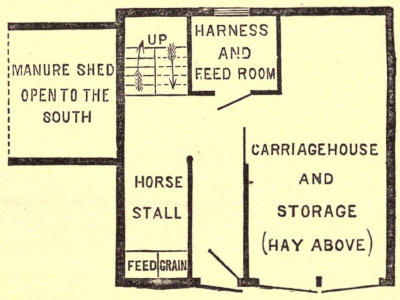

The barn is twenty-five by thirty feet, with the stable on the south side. The stall for “Spot” is five feet wide, and the floor on which she stands is five feet long, with a manger two feet wide in front, one and a half high next to the cow, and three feet next to the barn floor. She is fastened with a wide strap around her neck, attached to a chain eighteen inches long, which is fastened to a staple driven into a post at the corner of the stall adjoining the manger; this gives her room to turn her head so as to lick any portion of her body. The floor is made of two-inch plank, battened on the under side with thin boards, raised from the ground ten inches in rear and one foot in front; all the droppings and urine fall into the four-foot alley behind. This alley has a clay floor beaten perfectly solid and level. Next to the stable door is a large bin, ten by seven feet, for storing road-dust or muck; at the other end of the stable is another bin, ten by eleven feet, for storing leaves for bedding.[18] My great object is not only to make “Spot” comfortable, and have her stable free from all bad odors, but to save all the manure, both liquid and solid. The best absorbent is dried muck, pulverized, or road-dust from clayey roads. As it is easier to procure the latter, I generally make use of that, and always keep from two to three inches of it in the alley; this effectually absorbs all the liquid portions and all offensive odors. Twice each day, this is thrown out through a window closed by a sliding shutter in the rear of the stall, under a shed, where it remains until wanted for use. In the fall, I go to the woods and procure a sufficient quantity of leaves to last until spring; a liberal use of these not only makes a nice, soft, clean bed, but largely increases the quantity of manure. The stable opens into a small yard, across one corner of which runs a small brook. Each morning, the cow is permitted to go out and drink; if the weather is pleasant, she is allowed to remain out an hour for exercise. She is let out the same at night, after sunset in warm weather, so that she will not be annoyed by flies. The barn is well-battened, and is warm in winter; it is well ventilated by two windows, but these, in summer, are darkened by blinds, with wide slats, to keep out flies.

Each morning, while “Spot” is eating her breakfast, she is well curried with a curry comb or card, and if any filth is observed on her bag or teats (which is very seldom), they are carefully washed off, if in winter, with warm water. She is never scolded nor whipped; consequently she never kicks over the pail, or holds up her milk. She is fed in winter with a peck of sugar-beets cut up, both morning, noon, and night; also, a bushel of cut feed, either corn-stalks or clover hay, wet with a pailful of hot water, with two quarts of “sugar meal,” or bran, thoroughly mixed together, with a little salt sprinkled over it. I generally use what is known here as “sugar meal” to mix with her feed; it is corn meal from the factory after the sugar or glucose has been extracted; it costs from ten cents to twelve and a half cents per bushel, and I prefer it to bran, and “Spot” likes it very much. We consider her a machine for converting the food we give her into milk, and the more we can get her to eat and digest, the more milk is obtained, and the greater the profit. It is a good plan to change the food occasionally, substituting carrots for beets, clover hay for corn fodder, for brutes, like mankind, are fond of a variety. There are root-cutters that can be procured for cutting[19] up roots, but I have always used a common spade, ground sharp, and an empty flour barrel to hold the beets. It takes but a few minutes to cut up a mess of beets in that way.

With a bin of road-dust, and one of leaves, a winter’s supply of litter is secured, and it is surprising what a pile of manure we have in the spring. Another valuable source of manure is the pigsty, with plenty of leaves for a warm bed, and sufficient road-dust to absorb all the liquids, it is astonishing how clean our pigs are, and the sty is free from all bad odors; the big potatoes and mammoth beets, show the richness of the pig-pen fertilizer. I think our fifty hens pay for all their food with the droppings the poultry-house furnishes. The roosts are over a slanting platform, which is kept covered with road-dust both summer and winter; the droppings fall on this floor, and roll down into a large box twelve feet long, three feet wide, and three feet deep. The dust the chickens work down with the droppings is sufficient to absorb all the ammonia and preserve all the fertilizing qualities of this most valuable guano. A large box of road-dust is always kept in the water-closet, a liberal use of which furnishes a quantity of most valuable fertilizer, besides freeing the closets from all noxious smells. The wash water and slops from the kitchen are utilized by being thrown on a pile of sods and other rubbish, which are forked over, and as soon as decayed, carted to the manure pile. From so many sources we are enabled to give our small farm a most liberal supply of manure each spring and fall, so that even with the double cropping most of it gets, it continues to improve, and yields more bountifully each succeeding season.

In the cultivation of sugar beets, the ground is first manured heavily, plowed deep, and thoroughly pulverized with the cultivator, then marked out in rows with a garden plow, two feet apart. Manure from the poultry-house is scattered in each furrow, which should be lightly covered with soil, so the seed will not come in contact with it; drop the seeds about six inches apart, covering lightly with the garden rake. When the leaves are about four inches long, thin out to one plant in a place, and fill any vacancies with the plants pulled out. Hoe them thoroughly, destroying all weeds, which can easily be done by cultivating each time before hoeing, with an arrow cultivator. Keep the ground[20] mellow, and cultivate three or four times, after which they will take care of themselves and soon cover the ground. With ground in good condition, and a fair season, six hundred to eight hundred bushels per acre can be easily produced. Let them grow until frost comes, when they should be dug with a garden fork, the tops cut off, and stored for winter. Those to be used before the first of March, are stored in the cellar, the others are buried in a long pit, digging out a shallow place, piling up the roots about three feet high, and three feet wide, covering well with straw and sufficient soil to keep them from freezing, putting in a drain-tile about every four feet in the top of the pile, with one end to project a little through the covering, for ventilation. If the weather becomes very cold, lay a turf over the tile, and remove when pleasant. I grow carrots after the same plan, and store in like manner. I prefer beets, as they are so much larger, it is less trouble to gather and take care of them, and the crop is generally larger, still I always grow some carrots for a change. I plant sweet corn in drills, always put some fertilizer along the furrow, dropping the kernels about eight inches apart, with the rows three feet wide, I commence planting soon after May first, and continue at intervals until about July first, so I can have a fresh supply for use, and market, all the season. The sweet corn being grown on the plot sown to winter rye, for soiling, enables us to cut some portions of it twice, before the ground is needed for corn. When sowing corn for fodder, which is done as soon as we commence digging the early potatoes, I sow it in drills two feet apart, and drop the kernels about one inch apart in the drills, manure from the pigsty is first dropped in the furrow, and covered with soil at least two inches deep, or the corn will not come up. This fertilizer is so strong, if properly used it causes a most extraordinary growth of stalks. While the corn is small, cultivate it two or three times with a narrow cultivator, when it will take care of itself, and there will be a surprising growth of stalks; I have them often six feet high. Just before time for frosts, cut with a scythe, and set up in small bunches bound around the top, and leave to cure until cold weather. When it is to be put in the mow, spread alternately a layer of stalks, and a layer of straw, and it will keep bright and sweet until wanted. The rye for spring soiling is sown when the sweet corn is picked, and stalks removed, in drills about ten inches apart. Fine manure is spread on the ground after plowing, and thoroughly mixed with the surface soil; one or two hoeings being given to keep the ground mellow; to destroy any weeds that may make their appearance. By May[21] first, the early sown rye will cover the ground with a dense growth, at least four feet high, furnishing a large quantity of most nutritious green food. On those portions of the plot where the latest corn is to be planted, two or three cuttings are made; this gives most excellent food for the cow, and the quantity grown on this fourth of an acre will surprise any one who has never tried it. There is quite a plot of early peas, and as soon as the last picking occurs, while the vines are green, they are pulled and fed to “Spot,” who relishes them very much. Turnips, or corn, are at once sown on the ground where the peas were.

When our early cabbages are taken up, all the leaves, and much of the stalks, are turned into milk by taking them to the cow’s manger, and the ground at once planted, or sown, to something that will make more food. The beet, carrot, and turnip tops, and late cabbage leaves, make quite a quantity of feed late in the fall, if care is taken in saving and preserving them. Possibly there may be some better forage crop than “evergreen,” or sugar corn; I think another fall I will try the Minnesota Amber Sugar Cane, in a small way. I tried Pearl Millet, in one row, this season; it tillered, or spread wonderfully, but did not do so well as the corn, as the stalks were small, and the millet makes such a feeble growth, at first, it requires the whole season to produce as much fodder as I get from corn sowed the fourth of July.

I generally manage to have the cow come in about the first of September; by that means the six weeks time she is allowed to go dry, occurs during the warmest portion of the summer, viz., in July and August, when, with the facilities the person who keeps but one cow possesses, it is difficult to make good butter. This is also the season when butter most generally sells the lowest.

The calf is taught to drink after it is a week or ten days old, and fed on a porridge made from skim-milk and wheat middlings, or shorts; by the time it is six weeks or two months old it will be well fattened, and can be sold to the butcher for veal, at a good price, for at that season of the year veal is scarce and in demand. The cow being in full flow of milk all winter, when butter is most always high, will pay a good profit for her feed and care. A couple of weeks prior to the time the calf should be born, I make a box stall on the barn floor, and permit the cow to run loose in it until the calf is taken away to learn to drink. During this time she should have a good bed of leaves, and the stall be cleaned each night and morning. So far at such times I have experienced[22] no difficulty, or trouble; should any occur, it is better to apply to an experienced person, than to try and “doctor” her yourself. After the calf is born, I feed the cow on warm slops a day or two, permitting the calf to suck until the swelling has gone from her bag, and it has assumed its natural condition. Then, as before stated, teach it to drink, which can easily be done by inserting the finger in its mouth, and putting its head in the dish, cautiously withdrawing the finger a few times, and in a short time you will have no difficulty, as it will help itself.

In conclusion, I can say I have tried to state just how our cow is managed and kept. I presume there can be improvements made on our system. I shall be glad to take advantage of the experience of others, at any and all times. No record is kept of the milk obtained, or of the butter made. We know we always have plenty for the family’s use, and considerable to spare. Bread and milk furnish the children half their food a portion of the time. Pure milk and plenty of fresh fruits, in abundance, we consider afford one of the principal reasons why our family is so healthy, and we have so few doctor’s bills to pay.

From our acre and a half, all the food has been grown for both cow and horse, except the three dollars expended for straw. The “sugar meal” given the cow has not cost five dollars during the past year. It is safe to say, that one half, and probably more, of the clover, corn fodder, green rye, etc., has been fed to the horse. Consequently the keeping of the cow can all be credited to the small area of about three-fourths of an acre of land, in addition to an outlay of not exceeding seven dollars for meal, bran, and straw. This land, about one half of it, has also produced, in addition, full crops for the use of the family, or market, while the sour milk and buttermilk have largely assisted in making six hundred pounds of pork. The calf, at less than two months of age, was sold for eight dollars, which more than paid for the extra feed bought for the cow. The family which has never kept a cow can hardly realize the satisfaction and benefits derived from such a source. Children, whose appetites are often capricious, will almost always relish a cup of cool milk. Cream, for our coffee at breakfast, is much enjoyed by all, but realized by few, and what can be more delicious than a nice dish of strawberries smothered in rich yellow cream. When we consider the small expense, the little trouble and care, contrasted with the great benefits derived, it is, so to speak, surprising that any family should rest satisfied without possessing a cow.

Fig. 2.—THE AYRSHIRE COW “OLD CREAMER.”

For several years I had been experimenting on a small scale in soiling cattle. My area of land, however, was exceedingly limited, being only a portion of the kitchen garden of a city residence, but my success was, even in this small way, so satisfactory, that I determined at some future day to try it on a more extensive scale. My reading and experience convinced me, that in our favored southern climate, a half acre of land, intelligently cultivated, would produce a supply of food amply sufficient to support one cow through the year, and circumstances favoring, I determined to try the experiment. In April, 1876, I became owner of a lot two hundred and fifty feet long by one hundred and twenty wide in the rear of my premises—the greater portion having been used as a grass plot for a horse. I immediately began by fencing off a portion one hundred and twenty feet by two hundred, running a wagon-way eight feet wide down the center, which, with the space occupied by the stable (say twenty by thirty feet), left nearly twenty-two thousand feet, or within a fraction of half an acre, for actual cultivation. The land was a sandy loam, covered with a thick sod of Bermuda and other grasses. Years before it had been cultivated as a market garden, but latterly given up to grass; it sloped to the south sufficiently to favor good drainage. In and around the stable was a goodly lot of manure, which, during April, was spread upon the land—some forty cart loads. On April twentieth the land was thoroughly plowed with a two-horse turning-plow, and harrowed until finely pulverized. On May first, I planted one half of the land in Southern field corn, in drills two feet apart, with the grains about one inch apart. The rows were lengthwise, to render after cultivation more convenient. On May fourth, sugar corn was put in one half of the remainder, planting at the same distance as the larger variety. May sixth, the remaining fourth was sown heavily with German or “Golden” Millet, in drills twelve inches apart. Seasonable showers, followed by warm sunny days, soon produced a vigorous and rapid growth. On May fifteenth, a Thomas’ harrow was run over the first planted corn, and six days later over the second planting, and over the millet. On May thirtieth, the corn was plowed, followed by a good hoeing. A fortnight later, a second and last hoeing[26] was given. The millet was also hoed twice, after which the growth effectually shaded the ground, and thus prevented the growth of weeds. In the meantime I had repaired the stable, and had a large door cut into the side next to the original lot, and made a stall for our pet Jersey cow. The floor was cypress, three inches thick, and sloped slightly from the manger. By actual measurement of the space occupied by the cow—giving just room for her hind feet to clear the same, a trough, eight inches deep, and fifteen wide, was made to receive the urine and droppings. The stall was four and one half feet wide, the sides coming only half the length of the cow, and just her hight. The manger extended entirely across the stall, was twelve inches wide at the bottom, and eighteen at the top, and twelve deep, the bottom being twelve inches above the floor. The fastening consisted of a five-eighths iron rod, passing from one side of the stall to the other, along the center of the manger, and one inch from it. On this rod was a ring, to which was attached a short chain that ended in a snap-catch, to attach to a ring fastened to the head-stall—the head-stall being made of good, broad leather. Usually, in turning the cow out in the morning, the head-stall was unbuckled and left in the stable; to fasten again was but a moment’s work. By this arrangement the cow had full liberty to move her head, without any possibility of getting fastened by the halter. The bottom of this manger was made of slats, one half inch apart, so that no dirt could collect. For feeding wet messes, there was a box made to fit one end of the manger, which could be removed to be washed without trouble. With plenty of sawdust, costing only the hauling, perfect comfort and perfect cleanliness were matters of course.

Attached to the stable was a lot fifty by fifty feet, where, in pleasant weather, the cow was turned, but free to go in and out of her stall at pleasure. In this lot was a trough, connected with the pump, where a supply of clean and fresh water was always kept. Daily this trough was emptied and thoroughly cleaned. A cow may eat dirty feed occasionally, but see to it that the water she drinks is pure. Unless this is attended to her milk is unfit for human food.

The manure trough being supplied with sawdust, the urine, as well as the droppings, were saved and removed daily to a covered shed located in one corner of the lot, where it was kept moist, and worked over occasionally. Our Jersey was due with her second calf about June twentieth, but was still giving milk in April and May. Her feed from May first to June fifteenth, was the run of a common pasture, with a mess twice daily of[27] wheat bran and corn meal, with hay. On June first she was dried up for a brief resting spell. June fifteenth we began cutting the sugar corn, now waist high. This was run through a cutter (making cuts three-quarters of an inch), and fed to her three times a day, first sprinkling two quarts of wheat bran over the corn, and continuing the hay feed twice a day. At the same time she was taken from the pasture, not to go on again until this experiment was finished. June twenty-second her udder was so distended, it was deemed prudent to relieve it by milking. This was done twice a day for three days. Here, at the South, there is a foolish prejudice against doing this, the belief being strong among the ignorant classes that it will cause the death of the coming calf. In some instances I have found it necessary to relieve the udder daily for a week before calving; I never knew any evil to result. At dawn June twenty-fifth there was a fine heifer calf beside her. As soon as convenient the cow was thoroughly milked, and a bucket of water, with one quart each of corn meal and wheat bran stirred in, and a pinch of salt, was given her, and nothing else except water for twenty-four hours. At evening she was again milked to the last drop, and the calf left with her during the night. Next morning a small feed of three quarts of wheat bran, and one quart of corn meal, made pretty wet, was given her, and her udder again thoroughly emptied. After milking, a small feed of hay was given, and a pail of water placed near. The calf was separated from her, but within sight. At mid-day the calf was allowed to take her fill, and afterwards the udder stripped. At evening, as the cow seemed to be free from any indications of fever, or inflamed bag, she was given a full mess of corn meal, wheat bran, cotton-seed meal, and hay. Her calf took her supper, and the udder was again stripped; that night the calf was taken from her, never to suck again, as fresh milk in a city was too valuable to feed to even a registered Jersey. Having, in years past, lost several very fine cows from over-feeding and under-milking, at calving time, I cannot urge too strongly what Col. Geo. E. Waring calls “high starvation” at this critical period in a cow’s life. If a cow has been decently cared for up to the day of calving, she needs nothing but rest, quiet, and a light mash,—warm in cold weather—for twenty-four hours, and then but light feeding for two or three days. But be sure to empty her udder completely at least twice every twenty-four hours, and if the cow is a deep milker, then three times; with this treatment, the feed can be gradually increased to all that she will eat up clean.

It is a very easy matter to teach a calf to drink milk, when one has seen the thing done. Next morning this calf was impatient for her mess of warm milk, so, after milking her dam, I took a shallow pan, and putting two quarts of milk into it proceeded to give the first lesson in a calf’s life, of doing without a mother. The process is very simple; you merely wet the first and second fingers of the left hand with milk, and place them in the calf’s mouth, to give her a taste of what is in store. Repeat this a few times, then gradually draw the pan near her mouth with the right hand, using your left as above. When the calf permits your two fingers to enter her mouth, raise the pan so that your left hand will be immersed, and the calf, by suction, will draw the milk up between the fingers. At mid-day, another mess of milk, and a second lesson was given; at evening a third. Next morning the process was repeated, but in this instance she did not need the fingers to guide her to what was good for her; she readily accepted the situation, and stuck her pretty nose into the warm milk, which rapidly disappeared to where it would do the most good. But with milk worth ten cents per quart, and cream seven times as much, it did not “pay” to use six quarts daily of rich Jersey milk in this way, so, after a fortnight’s supply of the raw material, the feed was gradually changed to sweet skim-milk for two weeks, and then substituting hay-tea, the milk ration was cut down to two quarts daily. Beginning with a tablespoonful of cotton-seed meal, thoroughly mixed with the feed, the quantity was increased in ten days to one pint daily. At one month old, she was gradually taught to eat bran by stirring it into her food.

The preparation of hay-tea is very simple. Nice hay is run through a cutter, and taking an ordinary two-gallon pailful, boiling water is poured upon it; it is then covered and allowed to steep for twelve hours. This makes a most excellent food, and calves thrive upon it. The most stylish and vigorous calf I ever saw, was raised upon hay-tea, with bran and cotton-seed meal as here described. I enter thus fully into the best manner of raising a calf without its mother, for the especial benefit of my southern readers, where the thriftless habit of allowing the calf to suck its dam, oftentimes until a year old, so generally prevails. In this instance the little heifer got along nicely until two months old, when an aggravated attack of scours set in, but by timely doses of laudanum in a mess of warm gruel, poured down her throat twice a day, for three days, a cure was effected. In ordinary cases of[29] scours, a change to dry food will correct it, but it is well to watch and not to permit the disease to become seated. A few years ago, a very valuable young Jersey heifer, received from the vicinity of Philadelphia, was taken in this way, while undergoing the usual course of acclimation incident to northern cattle brought south, and the simpler treatment proving of no effect, I gave injections twice a day of rice-water and laudanum, besides drenching her with corn-gruel and laudanum. This was kept up for ten days; we carried her safely through, and her present value amply compensates for the time and trouble expended.

But let us return to the cow. On the morning of June twenty-ninth, we began giving her a fair feed of green corn, adding to it wheat bran, and cotton-seed meal. July second we fed her all the corn stalks she would eat, continuing to add bran and cotton meal, giving four quarts of the former and two of the latter; and this was her daily food, including the German Millet, treated in the same way, until September. The green food was given three times a day, but the bran and cotton meal added only morning and night. Occasionally a day’s supply was cut early in the morning, and allowed to wilt before feeding, but in this, as well as in many other matters, my man-of-all-work did as circumstances permitted. His various duties about the place gave him but little time to reduce to an exact system the care and feed of a cow. She had a good stable, and plenty to eat, received daily a good brushing, and was treated kindly. Yet, she was our servant (and a most faithful one she was), and we were not her’s, or slaves to any arbitrary clock-work regularity. She was fed and milked at regular intervals, but beyond this it was not always convenient to have regular hours at her stable. We did not keep her as an exhibition of a model cow in a model stable, and to exemplify a model system of care and keep. Like thousands all over the land, we kept her simply for the profit she yielded, in the way of milk and butter. It has often struck me, in reading the many suggestions and hints about how to keep a cow, to be found in some agricultural and live-stock journals, that were they all carried into practical operation, it would take the entire time of two able-bodied men to attend one animal—one to be always on hand during the day, the other to serve at night. Now common sense is a good thing, even when applied to the management of cows, and my experience convinces me that the[30] average man wishes only to know the cheapest and easiest way to have an abundant supply of rich, wholesome, and clean milk, and with pride enough in the possession of a good cow to furnish a good shelter and comfortable quarters. Beyond these, breeders of fancy and high-priced stock may go to any extreme, and find a paying business in doing so, but the village or city owner of one or two cows, kept solely for his own use, can not afford to indulge in any of this “upper-tendom” style of cow life; it won’t pay him. As a row of corn was cut and fed, the land was plowed, manured, and more corn (common field) drilled in thick, so that the ground for the whole summer presented the appearance of an experimental corn field, with corn at every stage of its growth.

This was kept up through the months of July, August, September, and October. Indeed, the half of this yield was more than sufficient for keeping the cow in superb condition, so that much the greater portion was cut in the tasselling stage and cured for winter feed. After September begins, it will not do to sow corn; the worms destroy it, but in our southern Bean, or “cow pea,” we have one of the very best of soiling crops. Sown either broadcast, or in drills, it does equally well, makes a rapid growth, and affords a tempting and nutritious food for cattle. It grows until checked by frost, and I know of no plant, save Indian corn, that produces more weight to a given quantity of land. In this instance we fed it daily during October and late into November, before a frost put an end to its use in its green state. Anticipating a frost, it was cut and cured for winter feed. Properly cured, no hay equals it for cattle.

November twenty-fourth our cow went into winter quarters, and for her winter feed there were over four thousand eight hundred pounds of well cured corn-fodder, and one thousand five hundred pounds of good pea-vine hay—far more than she could consume.

Early in December, after spreading over the land all the manure on hand, it was plowed again with a two-horse turning plow, and sowed thickly to oats, harrowing them in. A seasonable rain gave them a good start, so they were well prepared for the vicissitudes of winter—a good stand and vigorous growth. The cow now received a daily ration of corn fodder and pea hay, run through the cutter, and after mixing thoroughly three quarts of wheat bran and one quart of cotton-seed meal, were wet with water (warm in cold weather). This was given her in the morning, and the same quantity at evening. The corn fodder and pea-hay for a day’s feed were fifteen pounds of each,[31] more or less. On this food she was kept through the winter, giving milk of excellent quality, and in good quantity.

In February, she was tethered every fair day in the oats, and in March, we fed her a good mess of fresh cut oats, still, however, keeping up the winter feed of corn fodder, pea-hay, wheat bran, and cotton meal. About April first, the feed of green oats was increased to all she would eat, feeding three times daily, and the excellence of this diet was shown by a marked increase in the quantity of her milk. Though due to calve again in July, she continued to supply a family of ten persons with an abundance of milk. Late in April, when the oats were in the milk state, they were cut and cured for hay, making a little over a ton of good food.

Upon summing up the result, the following dollar and cents view of the experiment of sustaining a cow on a half acre is submitted. The labor expended in cultivation is not put down as an item of expense, as the carriage horse was used in plowing, and the hired man did the rest.

| Dr. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| To | 1,500 | pounds Wheat Bran, at 90c. | $13.50 | |

| ” | 200 | pounds Corn Meal, at 70c. | 1.40 | |

| ” | 800 | pounds Cotton-seed Meal, at $1 | 8.00 | |

| ” | 300 | pounds Hay, at 75c. | 2.25 | |

| Total | $25.15 | |||

| Cr. | ||||

| By sale of | 2,200 | pounds of Corn-fodder, at 60c. | $13.20 | |

| ” | 2,100 | pounds of Oats, at 75c. | 15.75 | |

| $28.95 | ||||

| Profit | $ 3.80 | |||

But the profit above shown does not express the real profit. A year’s continuous supply of rich milk in abundance, for a large household, cream for special occasions, and that best of luxuries, delicious home-made butter, and one hundred dollars for the little heifer when six months old, aggregate the chief results of the experiment.

For the best results in soiling, no crop compares, as far as my experience goes, with our Southern variety of Indian corn; on rich land it produces marvellously. I have raised it at the rate of one hundred thousand pounds (or fifty tons) per acre. There is no difficulty in producing three crops in one season on the same land. But cattle need a variety of food in soiling, as in other forms of feeding. Oats are excellent, and come in early. Cat-tail Millet (“Pearl Millet”) is a rapid grower, but cattle are not specially fond of it; they like German Millet better. Garden (or[32] English) Peas make an excellent food, coming into use in March, and lasting to June. I remember one year I produced five crops for soiling, on the same land, in one year, namely: oats, three of corn, and one of cow-peas. The last named is a superb food late in the year, after corn has gone. I have never experimented with roots, nor am I aware of any being cultivated in the South as a soiling crop. Cabbages set out in September and October will be ready for feeding in December, and will, next to corn, produce the largest weight of green food. One year I fed them to a considerable extent, and found my cows were very partial to them. By beginning with cabbages in December, to be succeeded by oats in March, then peas, corn, and millet, to wind up in November with cow-pea, a cow in our climate can be soiled every day in the year.

Fig. 3.—THE JERSEY COW “ROSALEE.”

BY HENRY E. ALVORD, EASTHAMPTON, MASS.

In writing upon this subject the narrative form is convenient, and while it cannot be claimed that this is entirely a “true story,” it may be said to be founded on fact. Personal experience is my basis, and whatever of fancy may be interwoven with the facts would have been quite practicable, and all ought to have occurred as narrated, if all did not.

Let me premise by saying that I own a comfortable little home in a village of a few thousand inhabitants, not a thousand miles from New York, supporting my family by a moderate income earned from day to day, and my occupation is such as to enable me to spend an average of three hours of daylight on my place, from the middle of March to the middle of October, and occasionally a whole day besides. Thus I can make and care for my garden, which for some years has uniformly been an excellent one, quite a model, though I say it. Of this sort of work I have always been very fond, as well as of domestic animals, all kinds of which were familiar to me when a boy.

May 1st, 1875.—For several years I have kept more or less poultry, and sometimes a pig; there is so much from a good garden that is otherwise wasted. The ambition of the family is to own a horse and a cow. It has been talked about a good deal, but we are agreed that the horse would be a pure luxury, in our circumstances, and must wait. The cow I have felt would be a luxury too, that is, cost more than it would produce, but on this point the good wife has differed with me, claiming that it would be a real economy. It has been a part of our domestic policy to use milk and butter liberally, thereby keeping down the butcher’s bill and buying very little lard. Of the value of milk as an article of food, in its natural state, and in the many ways which it can be used in cooking, there can be no doubt, especially where there are young and growing members of the family. Still, I have been skeptical on the economy of keeping a cow, and to convince me, the help-meet recently proved, from well kept accounts, that during the last two years there have been consumed by our family of five persons, one thousand five hundred and forty-five quarts of milk, averaging seven cents a quart, and three hundred and sixty-one pounds of butter, average price thirty-three cents a pound.[36] These have amounted to a cash expenditure of one hundred and thirteen dollars and sixty-four cents a year, which was a decided surprise to me, and feeling pretty sure the expense need not exceed two dollars a week, I yielded to the argument; am the owner of a cow, and here record the result of my experiment. One of the pleasant spring days of last week, we took a drive among the farms of the vicinity, and selected a good looking cow which had just dropped her second calf. The price paid was sixty-five dollars, to be delivered to me to-day, without the calf. The man I bought of called her “pure Alderney,” but she looks large of her age for that race, weighing somewhat over seven hundred pounds, and if, two or three generations back there was a cross of Ayrshire, or of Guernsey, it is all the better. My belief is that she has a streak of Ayrshire blood, and that she will make a fine cow. Being three years old next month (exact date unknown), it has been decided that our cow is to be known as “June.”

May 1st, 1876.—When “June” was bought, it was in the full expectation that pasturage could be hired in a small lot adjoining the rear of mine. I supposed it was fixed, but the spring had been favorable, the grass on the meadow promised well, and the owner concluded he would mow it, so that arrangement fell through. By that time I was too late to secure room in the only pasture convenient to the village, and I have been forced to keep her in the stable and a small stable yard, the whole year. The result is more than satisfactory, considering the disadvantageous circumstances.

A year ago to-day “June” arrived, in fair condition, save that her coat looked a little rough, and with a good bag of milk; her daily yield that month was about twelve quarts. In a day or two I noticed that when in the yard, she rubbed her neck vigorously against the corner of the stable and sometimes backed up to a building or fence for the purpose. An examination proved that she had vermin upon her; so I made a pail full of strong suds, with soft soap, and put into it an ounce of sulphuric acid, and with this I sponged the parts infested, twice daily, for a few days. This seemed efficient and there has been no such trouble since.

For long forage “June” had only dry food, good fine hay, until late in May, and then I began to give her a green bite whenever I could, clippings from the yard, trimmings of early vegetables and whatever there was to spare from the garden. Besides this, everything she ate had to be bought, except a few roots used since February. A little bran was fed for the first few days, and gradually[37] increased, so that during the summer she received four pounds daily, fed in two parts, morning and night. Later in the season corn-meal was added to the ration, and at times oats were substituted for the bran. In the winter, eight pounds of meal and bran, half and half, mixed, was the daily allowance. Buying hay in small quantities I managed to keep both rowen and clover hay on hand, some of it very fresh, and could thus vary the dry food. Also, for variety, I frequently gave one cut feed a day, moistened. Besides this, I obtained and worked in, during the summer, a lot of half-ripe oats, in the straw, which had lodged and were cured like hay. The food, although thus often changed, was changed carefully.

In my garden I made a large parsnip bed, and followed my earliest peas with carrots, so that in the fall there were several bushels of these roots. The carrots were buried in the garden, a mellow loam, and the parsnips left in the ground. The former were opened during a thaw in February, and a few fed to “June” each day, lasting until the end of March; by that time I could get the parsnips and they have just given out. When I began the roots the grain was gradually withheld and she has had none since February. These roots have had a most apparent effect, giving her coat a bright, thrifty look, and she is in fine condition for calving, which is expected in ten days. But the roots made it hard to dry off the cow. She was shrinking in milk fast when we began on the carrots, then started up again and was giving about three quarts a day in March, when the milk (and especially the cream) began to have a sharp, unpleasant, bitter taste, and we soon had to give up using it. It then took a fortnight to dry her off, which was done by lessening the roots, milking not quite dry, then only once a day, and once in two days. Water has been offered three times a day, through the year, all she would drink, salt has always been within her reach. All summer, and every mild, dry day in winter, “June” has passed some hours in the stable yard. A large amount of bedding has been necessary, and for this I have used the waste hay, the rakings of the yard last autumn, the scrapings of the garden walks, garden litter, and the leaves from a row of maple trees in front of the house, carefully saved for the purpose. So much in the stall, “June” has required more personal care, and it has been made a rule to rub and brush her body enough to keep it clean and free from dead skin. But I never use a harsh card; nothing is better for rubbing than a piece of old seine or very coarse bagging. Everything about the cow, too, is kept clean and sweet.

The result of this continuous stabling has been a rapid accumulation of manure, and this having been mixed with all the suitable refuse of the place, and forked over several times, I this spring have on hand a huge pile of rich compost. It is more than can be used on the garden, and the newer part has been corded up under a temporary shed for sale or future use. This alone well pays for all my extra work in keeping the cow, as I have yearly been obliged to buy for the garden.

Our plan during the year has been to sell a little milk to neighbors, set aside two quarts daily for family use, cream and all. The cream from the remainder has been made into butter, and an accurate account kept of the butter produced.

The following is the result of this first year keeping one cow:

| EXPENSES: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Interest 7 per cent on cost of cow | $ 4.55 | ||

| 4 tons of Hay, av. $20 | 80.00 | ||

| 500 lbs Oats in straw | 4.25 | ||

| 960 lbs. Wheat Bran, @ $1.20 | 11.52 | ||

| 350 lbs. Corn-Meal @ $1.10 | 3.85 | ||

| 4 bus. Oats @ 55c. | 2.20 | ||

| Expended | $106.37 | ||

| Less 400 lbs. Hay on hand | 3.00 | ||

| Year’s expense | 103.37 | ||

| RETURNS: | |||

| 155 qts. Milk sold @ 7c. | $ 10.85 | ||

| 311 qts. Skim-milk, @ 3c. | 9.33 | ||

| Sales | $ 20.18 | ||

| 620 qts. Milk for family, @ 7c. | 43.40 | ||

| 123 lbs. Butter made, @ 35c. | 43.05 | ||

| Year’s return | $106.63 | ||

| Memorandum—Cost | $103.37 | ||

| Less sales | 20.18 | ||

| 83.19 | |||

| Plus purchases— | |||

| 88 qts. Milk | 6.16 | ||

| 52 lbs. Butter | 16.64 | ||

| Cow products cost family | $105.99 | ||

Here is a net balance of three dollars and twenty-six cents in favor of the cow, without allowing anything for the abundant supply of skim-milk and butter-milk which has been profitably used in the poultry yard as well as at the house—or for the big compost heap, which could readily be sold.

The figures also show that the family has had a better supply of cow products than last year, at seven dollars and sixty-five cents less expense. No labor is charged, for I am not so much keeping an exact account of the maintenance of the cow, as of the profit of my keeping one, taking care of her myself. And no credit is given for manure, as I mean to apply that to reducing the cost of keeping in the future. The cow might have been fed at less cost, but I intended to have her improve on my hands, and she has done so. “June” now weighs seven hundred and sixty-two pounds, is about to have her third calf, and is certainly worth more than was paid for her.

Altogether, in spite of unfavorable conditions there is no occasion to complain of the result of the year.

May 1st, 1877.—Last spring, my neighbor, north, was willing to let me have his acre and a half of meadow for pasturage, but wanted thirty-five dollars for the season. I would not pay that, and, instead, hired a place for “June” in a large pasture half a mile or more distant, paying twenty dollars for the season, May fifteenth, to October fifteenth, and four dollars to a boy for driving. On the ninth of May, the cow dropped a bull calf without difficulty, and I gave it away the next day. No special care was needed or given, except a little caution as to feeding, and on the fifteenth the cow went to pasture. She did remarkably well until early in July, being in pasture during the day, and at the stable at night. Then the weather grew very hot, the pasture dry, and “June” began to fail rapidly in her milk; so I commenced feeding a little bran, and offered hay when she came up at night. Later, a friend recommended cotton-seed meal, and a hundred weight of that was obtained and fed with good results, two or three pounds a day. August was a month of intense dry heat, and the pasture became of little use except for the exercise, shade, and water. In spite of meal and hay fed at night, “June’s” yield of milk shrank to three quarts a day, and we feared she would go dry. August fifth, I made the change of sending her to pasture just before six o’clock in the evening, as the boy went after the other cows, and bringing her up to the stable in the morning, where I kept her during the day. This was an improvement, and also gave better opportunity of feeding sweet corn stalks, vegetable trimmings and the like, fresh from the garden. The grain was continued through August, and she ate more or less hay. At the end of the month she was giving over a gallon of milk a day. Rains came early in September, the pasturage soon became good again, and the daily mess of milk steadily increased until November. By that time she was in the stable for the winter, and the treatment since has been practically a repetition of last year. My root patch in the garden was enlarged, as the result of last year’s experience, and accordingly I put eight or ten bushels of carrots into my cellar in October, covering them with sand, and left a fine lot of parsnips in the ground. I began feeding the carrots in January, two or three a day, just for a relish; gradually increased them, until in February the cow received half a peck or more, and thus they lasted into March. Then I dried her off, getting the last milk to use March twenty-eighth. Grain feeding was stopped the first of March, and she has had none since. After the cow was fully dry, I began on the parsnips, and she is now getting half a peck daily,[40] with all the hay she will eat. “June” will be fresh again on the twentieth of this month.

The season has not satisfied me. Not only has the weather been unfavorable, (we must expect severe summers occasionally,) but I don’t like sending the cow to a distant pasture which I can know very little about, and where nobody knows how the other animals treat her. I shall never do this again if any other arrangement can be made.

The account for the year is as follows:

| Expenses. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Interest at 7 per cent. on cost of cow | $4.55 | |

| Hay from last year | 3.00 | |

| 2½ tons Timothy Hay @ $18 | 45.00 | |

| Pasturage and driving | 24.00 | |

| 750 lbs. Wheat Bran @ $1.10 | 8.25 | |

| 450 lbs. Corn-Meal @ $1 | 4.50 | |

| 100 lbs. Cotton-seed Meal | 2.00 | |

| Expended | $91.30 | |

| Less hay on hand | 2.00 | |

| Year’s expense | $89.30 | |

| Returns. | ||

| 42 qts Milk sold at 6½c. | $2.73 | |

| 286 qts. Skim-milk sold at 3c. | 8.58 | |

| Sales | $11.31 | |

| 640 qts. Milk for family, at 6½c. | 41.60 | |

| 109 lbs. Butter made @ 32c. | 34.88 | |

| Year’s returns | $87.79 | |

| Memorandum—Cost | $89.30 | |

| Less sales | 11.31 | |

| 77.99 | ||

| Plus purchases— | ||

| 86 qts. Milk @ 6½c. | $ 5.59 | |

| 70 lbs. Butter @ 30c. | 21.00 | |

| Cow products cost family | $104.58 | |

Comparing this with last year’s statement, it will be seen that although there is a small balance against the cow, she is still, all things considered, a profitable part of the domestic establishment.

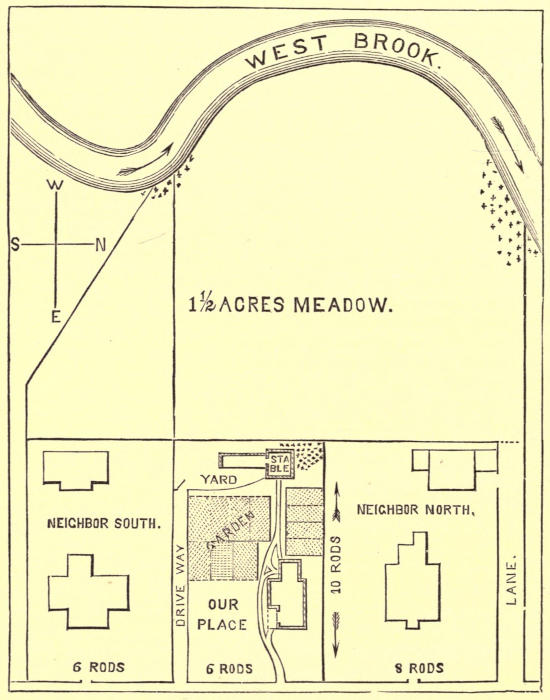

May 1st, 1878.—Dissatisfied with the last year’s management, and seeing that there would last spring be a large surplus of fine compost on hand, more profitable to use than to sell, I planned a new arrangement in the autumn of 1876 for keeping my one cow. First, I secured the meadow west of my lot, renting it from the owner from October first, 1876, until April first, this year, for thirty dollars. The acre and a half yielded about two tons of hay in 1876, but no rowen; the aftermath was good, however, when I came in possession. The south end of it, although in good heart, was weedy and uneven. I drove some strong stakes, and ran a wire fence across, in continuation of my southern boundary, thus cutting off just about a quarter of an acre in rear of my neighbor, south. This piece I dressed with compost made the summer just preceding, and had it plowed and cross-plowed before the ground froze, in preparation for a root crop. The soil is a deep, mellow, sandy loam, but rich. Last spring the new root patch was plowed once, well dressed from the compost pile of 1875-6, and that harrowed in. (There was enough of the same compost for my garden, and to spare, so last June there was still on hand the manure of about a year’s collection put up in good shape.) The rest of[41] the work I was able to do myself. My root-garden, laid out in rows running north and south, was divided as follows: eight square rods of parsnips next to neighbor, south, on the slope, where they caught the wash from his garden; twelve square rods of carrots and ten rods of mangolds; in the point west to the stream I put sweet corn at first, and followed it with strap-leafed turnips, ten square rods. Without going into the details of root-culture, which any one who has made a good garden knows all about, I put into my house cellar last fall fifty-two bushels of Long Orange Carrots, and over forty bushels of Long Yellow Mangel Wurzels (these monstrous, twisted, forked roots are awkward things to measure, but there must have been a ton or more in weight), left in the ground from twenty to twenty-five bushels of Hollow-crowned Parsnips, and harvested thirty-six bushels of English Turnips. This was more than I had bargained for. I see now that roots enough might have been raised in my old garden, and the parsnips would have done much better there, but I sold twenty bushels each of carrots and turnips for more than enough to cover all expenditures for seed and hired labor.

A year ago to-day, I turned “June” into her new pasture of an acre and a quarter; the grass was then starting well, and I preferred to have the change gradual. She ate more or less hay until the end of the month. Doors and gates were so fixed that she could be in stall, yard, or pasture at pleasure, and could drink at the stream bordering the meadow.

On the eighteenth of May, her bag began to swell, and became feverish. A quart or two of watery milk was drawn at intervals of eight hours for the next three days, and the udder was bathed as often in tepid water, and gently but thoroughly rubbed with goose oil, in which camphor-gum had been dissolved. Each day, also, she was given a quarter of a pound of Epsom Salts, dissolved in a quart of “tea” made from poke-weed root (Phytolacca decandra), which all druggists now keep in store; this was administered as a “drench,” from a bottle, her head being held up while she swallowed it. On the morning of the twenty-second, being two days overdue, she calved, having a hard time, but producing without help a fine large heifer. Very soon after, I gave her a bucket of cool (not cold) water, in which was stirred a quart of wheat bran, a half pound of linseed-meal, previously scalded, and a handful of pulverized poke or garget root. This mess was repeated at noon, and[42] the bag milked dry. A little later, the after-birth naturally passed off and was removed. The udder remained hot, knotty, and so tender that when the calf sucked I had to protect it from the mother’s kicks, and also to prevent it from taking one teat which was extremely sore. From this quarter I carefully drew the milk with one of a set of four “milking-tubes,” which I bought two years ago to do my milking, but soon discarded; here they came in use, just the thing wanted, but one as good as four. At night I milked dry, gave a dose of half a pound of Salts, with one ounce of Nitre, and a warm Bran-mash. The bag was well rubbed as before. The cow ate some hay during the night, and a few cabbage sprouts in the morning. That day (twenty-third), she was on the pasture a little while, and had a full bag of milk, but still hot and tender. The calf was separated from the cow at daylight, and allowed to suck four times during the day, the bag being milked dry, and then oiled and well rubbed every time. The bowels appearing to be in a sufficiently active state, appetite improving, and her eyes natural, the physic was discontinued, the cow allowed to eat grass and hay at will, and for several days the calf sucked at daylight, noon, and dark, the milk left by it being all drawn. The bag was rubbed and anointed two or three times a day, and a little extract of Belladonna added to the oil used. Under this treatment the inflammation gradually subsided. As soon as the cow would allow her calf to take the tenderest teat, I kept it on that side as much as possible while sucking. At the end of a week after calving, the udder was again in sound condition. The calf was kept until the first of June, and then the owner of its sire took it in full for service of bull three seasons. We then began to get the full flow of milk, and the pasture being good, it was a fine mess daily. At that time, I began to measure the milk, and have done so ever since. “June” gave four hundred and eighty-two quarts the month she was five years old, an average of sixteen quarts a day.