Dragons

and

Cherry

Blossoms

By

Mrs. Robert

C. Morris

New York

Dodd, Mead

& Company

1896

Title: Dragons and Cherry Blossoms

Author: Alice A. Parmelee Morris

Release date: June 11, 2022 [eBook #68287]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Dodd, Mead & company, 1896

Credits: Charlie Howard and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them. When text follows the contours of an illustration, a larger version of that illustration may be seen by clicking or right-clicking the word “Larger” just below the illustration.

Dragons

and

Cherry

Blossoms

By

Mrs. Robert

C. Morris

New York

Dodd, Mead

& Company

1896

Copyright, 1896,

By Dodd, Mead and Company.

All rights reserved.

University Press:

John Wilson and Son, Cambridge, U.S.A.

TO

MY HUSBAND.

Many have been before me, and the theme of this volume can hardly be called new, for Japan has been viewed from every side and through all kinds of eyes. This, however, has not deterred me from jotting down a few observations and experiences of my own, hoping that in them my readers may feel some rays of the Orient sunshine and beauty.

I desire to thank Mr. Burton J. Hendrick for the kind and sympathetic aid given upon the manuscript.

| Page | |

| Foreign Residents | 15 |

| Shopping | 49 |

| Our Dinner at Kioto | 81 |

| Miyako Odori | 109 |

| The Rise and Fall of the Kakemono | 141 |

| A Glimpse of Royalty | 173 |

| Fin de Siècle Japan | 209 |

| Cho and Eba | 239 |

15

Your visit to Japan is likely to be a succession of surprises. Our discovery of the country is so recent that the large amount of literature on the subject frequently fails to change your childhood impression of that distant land. European travellers often entertain us with their ideas of America as an uncultivated waste with an occasional hastily constructed town, in which the red man is still to be16 seen; and my notions of the land of the Mikado were somewhat similar. I could never think of the Orient without thinking of the mushroom hat; and for me Japan meant a succession of bamboo huts, almond-eyed men with long and low-hanging moustaches, an occasional china cup, and now and then a strangely decorated fan. I was not at all sure that it was a hospitable shore to visit; I understood that heads were removed there upon the slightest provocation. My earliest knowledge was gained from the paper lanterns that were the delight of Fourth-of-July celebrations, and those remarkably adorned napkins familiar to patrons of church fairs. I was also frequently called upon to make Sunday-School contributions17 for the conversion of these abandoned souls, and have vivid recollections of listening to many addresses by daring spirits, who had actually returned from the dangerous soil. After such occasions as these, I always looked upon the principal occupation of the Japanese as the stoning of missionaries. As I grew older, I tried to educate myself into different ideas, but all the books that I read, and even an occasional Japanese friend that I made, did not succeed in doing away with my childish fancies.

And so, when I found myself sailing into the Port of Yokohama one bright April morning, the ideal Japan of years gone by was what was uppermost in my mind. At first I thought there must be some mistake, for there was nothing to be seen in this harbour to correspond with the strange delights of my dreams. Not a single18 one-storied, thatched house, such as used to grace the pages of my geography, was visible on the shore. Everything, as far as I could see, was the same as the entrance to an European seaport. The long array of wharves might perhaps be missing, but there was many a ship built on western lines, and occasionally a small steam-tug went puffing by, the whistle blowing as naturally as in any western harbour. And, even as I looked beyond all this, towards the shore, there was no visible sign that I had reached Japan. “Those people who make pictures of Japanese life do not tell the truth,” I thought to myself, completely bewildered. When I landed, I found large brick houses of a most occidental kind, and shops fitted out in the regular English style. Not only were the outward evidences of life most un-Japanese, but few of19 the people passing up and down the street had the almond eyes, the short, wiry hair, or the olive complexion that I had quitted America to see; and young nurse girls wheeled about little carriages containing the same kind of babies that I had left three thousand miles away. Children in little trim English clothes, with their little English bare legs, were walking about and occasionally disappearing behind English hedges into houses of a distinctly Queen Anne type.

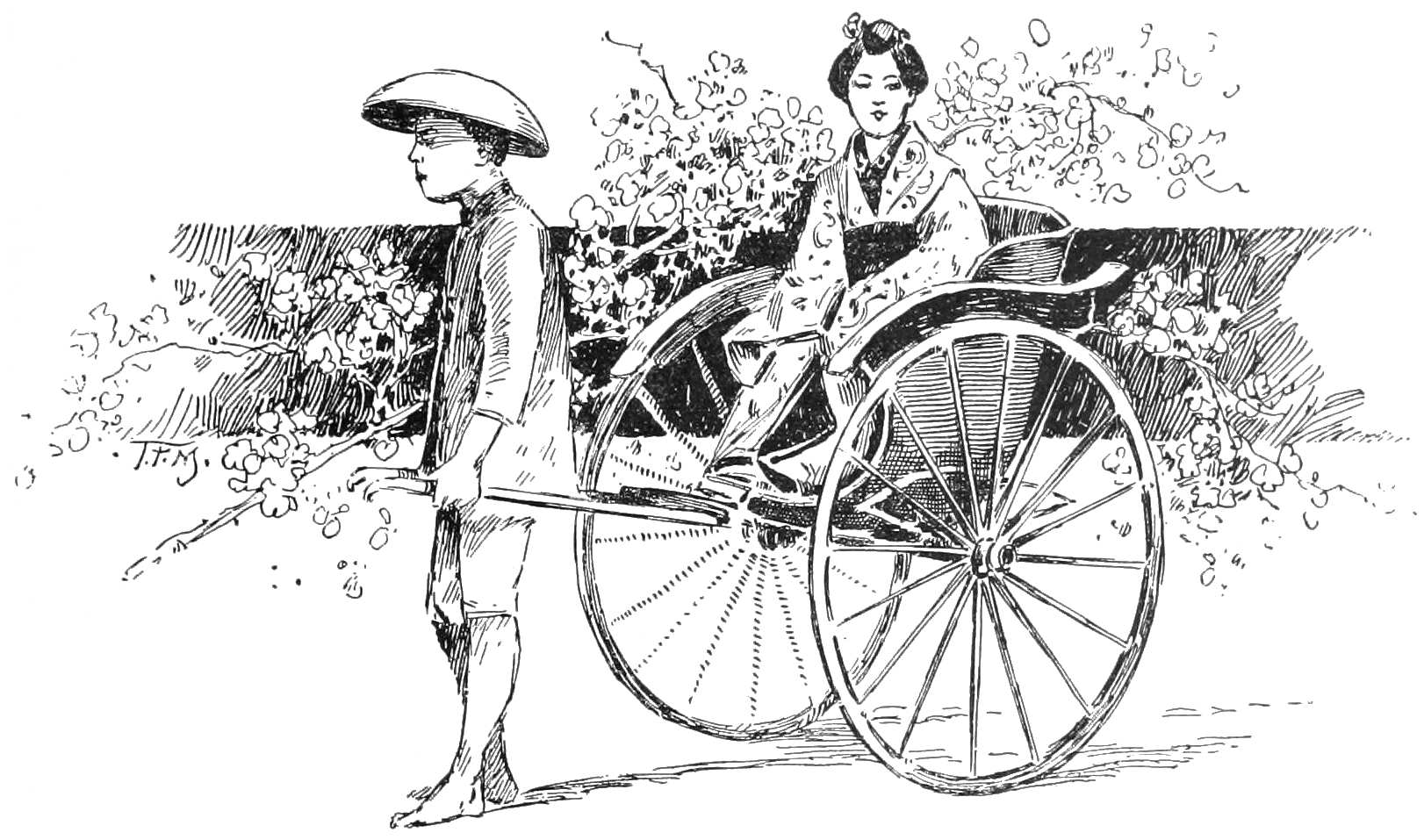

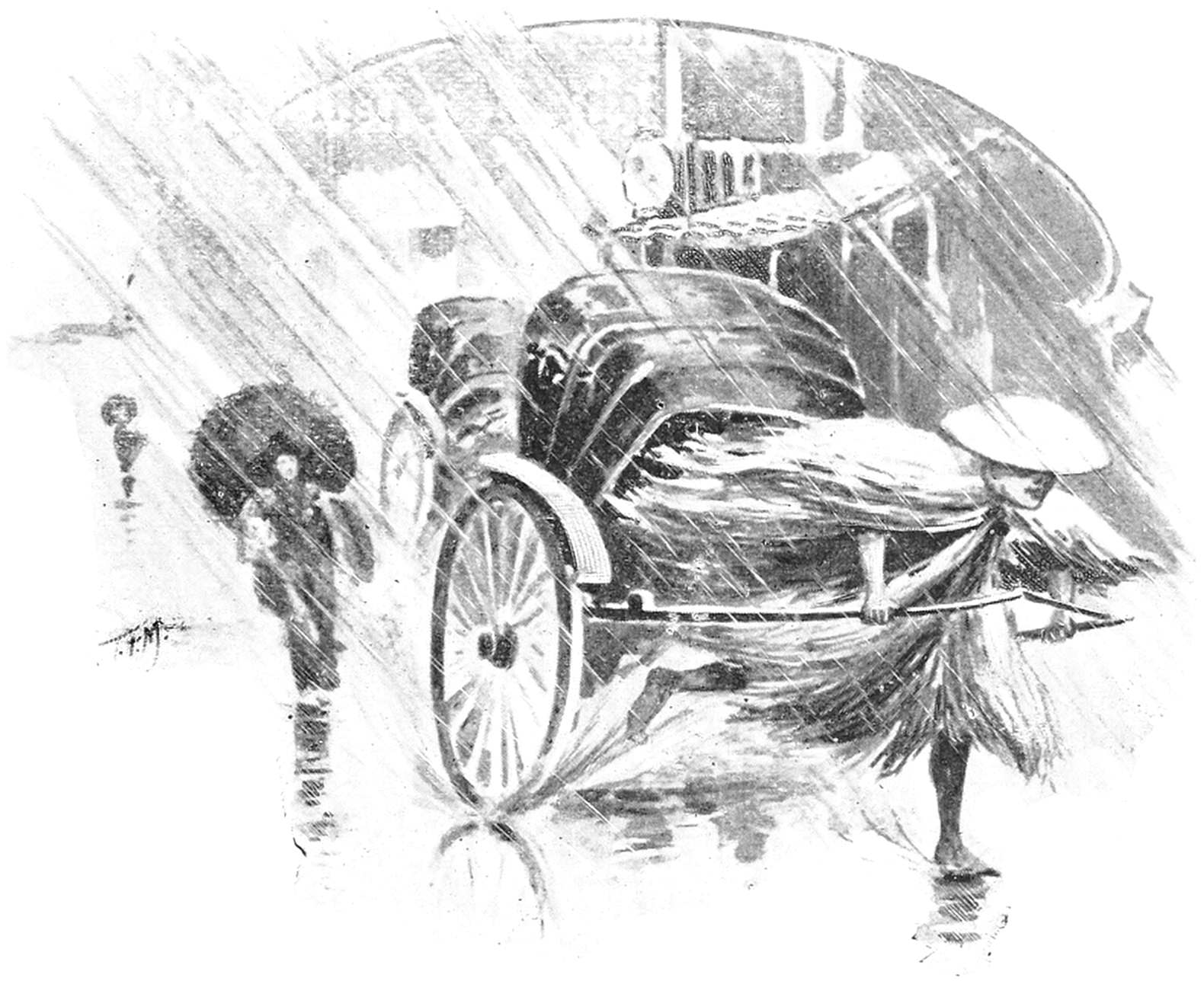

While I was surveying all this with a startled air, I was delighted and relieved by the sight of several small Orientals who ran quickly up to the wharf, dragging behind them peculiar two-wheeled conveyances. Yes, after all, here was some indication of the thing for which I had been looking; these were men of Japan, it was true, but hardly the Japanese of20 whom I had dreamed. They seemed rather out of place in this European city, and did not assume an aggressive air at all, as they politely offered to carry us to the hotel in their strange vehicles.

The explanation of this state of affairs is, however, very satisfactory. When you reach Yokohama, you land at what is called the Settlement, which is the portion of the city set aside by the Government for the foreign residents. Japan itself is situated back of this, and there, if you jump again into your jinrikisha and take another ride, you will find that it is Japan indeed.

There is one great hotel at Yokohama,—a genuine European importation, with large parlours, reading and sitting rooms, electric lights and bells. Your jinrikisha man immediately takes it for granted that you wish to stop21 at the Grand Hotel, and without waiting for instructions, hurries you off to Ni-jiu-ban, as it is called in the vernacular. You will probably arrive during the season of travel, and so be enabled to see the house at its best. If one or two of the foreign ships are in the harbour, and the officers come ashore, a scene of unusual attractiveness is sure to follow. A military band plays during dinner, commonly discoursing the patriotic airs of the different nations, though a well-known western march is frequently interspersed. The rooms are trimmed with flowers; there are ladies in bright, pretty gowns, men in evening dress, and Japanese “boys” in blue tights, white coats, and stocking feet. The gathering is decidedly cosmopolitan. You can talk with an American on stocks, an Englishman on golf, a Frenchman on Panama, or a Russian22 on the Triple Alliance. If you only step out on the piazza and take a short stroll, you will have a fine opportunity to gratify your taste for contrast, for it will be stepping from the Occident to the Orient. Perhaps the moon is shining—and the moon seems to shine differently in Japan than at home. There, below you, lies the land you thought you were being cheated out of; there are the small one-storied houses, the narrow streets, all bathed in the silence that so well fits your mood. A few lights are blinking below, but for the most part you see only what the moonlight cares to reveal. Off in the harbour are large shadowy forms which you know are western vessels, and your spirit feels a touch of old-fashioned patriotism at the thought that one of them is flying the American flag. The sound of the music comes from the23 distance, and you know that the dancing has begun; but you care little at the present time for such occidental diversions.

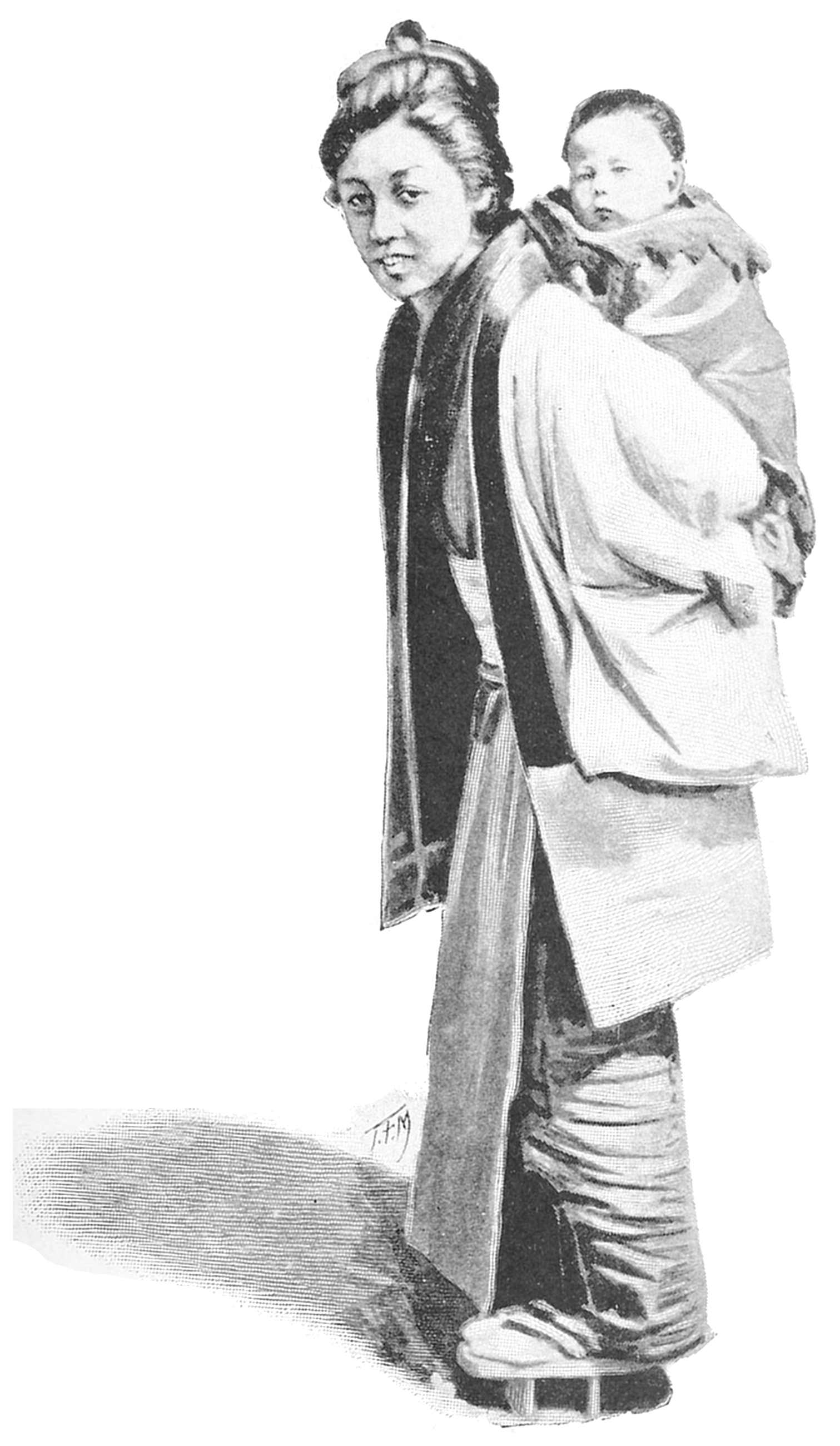

In the morning the sun will probably be shining in a truly oriental way, and you think it might be well to take a drive. Probably the first thing you will see, will be a large number of young Japanese girls, apparently out24 for a walk. Though they are clad in their own native costumes and have a general appearance that is decidedly Japanese, there is yet an air about them suggestive of the West. You puzzle over the matter for some time, and at last, with a sudden burst of intelligence, exclaim: “A boarding-school.” And you are right; these young girls are being trained in the usages of the best English society, and have begun to dabble in French and algebra in a true boarding-school style. As they pass you by and you go on, you will see many small children attended by Japanese amahs, and baby carriages meet you everywhere. There are also a few shops scattered around, and looking to the left you will see the British flag waving above the marine hospital. A little further on, your heart gives a bound, for you see the stars and stripes waving in the breeze,25 and you think that being an American is not so bad after all, whatever the foreigner may say of our confusion of “baggage” and “luggage” and our use of ice-water at dinner. It is the American hospital, a large, old-fashioned building, comfortable and home-like, with a garden filled with flowers and tropical plants. You can look from here into the bay, and the ship so dimly perceived the night before, you see is the “Baltimore.” You keep in the road, pass more Queen Anne houses and pretty green hedges, and an occasional bungalow; and further on you meet a park that has been laid out by the foreigners. Here are more baby carriages and bare legged children, and several prettily arranged tennis courts in which the players are enjoying themselves in a genuine English way.

It is probably a holiday, and the26 people will soon turn out for a celebration. It is hard to find a day in Japan that is not a holiday. It is well to know this before you visit the country, or you will be very much inconvenienced. You will be likely to visit the bank, and be much surprised to find it closed. “Why?” you will ask a friend, and he will answer: “It is a holiday.” And what is the day celebrated? Perhaps the fall of the Bastile; perhaps the discovery of the Gunpowder Plot; perhaps Washington’s birthday, the Fourth of July, or one of the innumerable sacred days of the Japanese. The trouble is that there are so many different nationalities in Japan, each demanding that certain events be respectfully observed, that only on about one-third of the calendar days can business be transacted. It is a country of a perennial holiday. There27 are a great many ways in which properly to observe these occasions, and a large number of entertainments are arranged. If you wish, you can attend the theatre,—not the anciently-established institution of the country, but a genuine play, such as you sometimes see in the Occident. I qualify the statement because I think it seldom that you will permit yourself to attend such execrable performances at home as draw crowded houses of intelligent people at Yokohama. They are given by strolling players on their way around the world, who stop at the principal Japanese cities and foist their wares upon a diversion-craving public. They entertain you with the misfortune of the “Forsaken Leah,” the mistakes and unavailing repentance of “Bob Briley,” the “Ticket-of-leave-man,” or you may have the opportunity of28 weeping through five acts of “East Lynne,” or “The Elopement.” A minstrel show has been known to come ashore, and an exhibition of French marionettes is no uncommon sight.

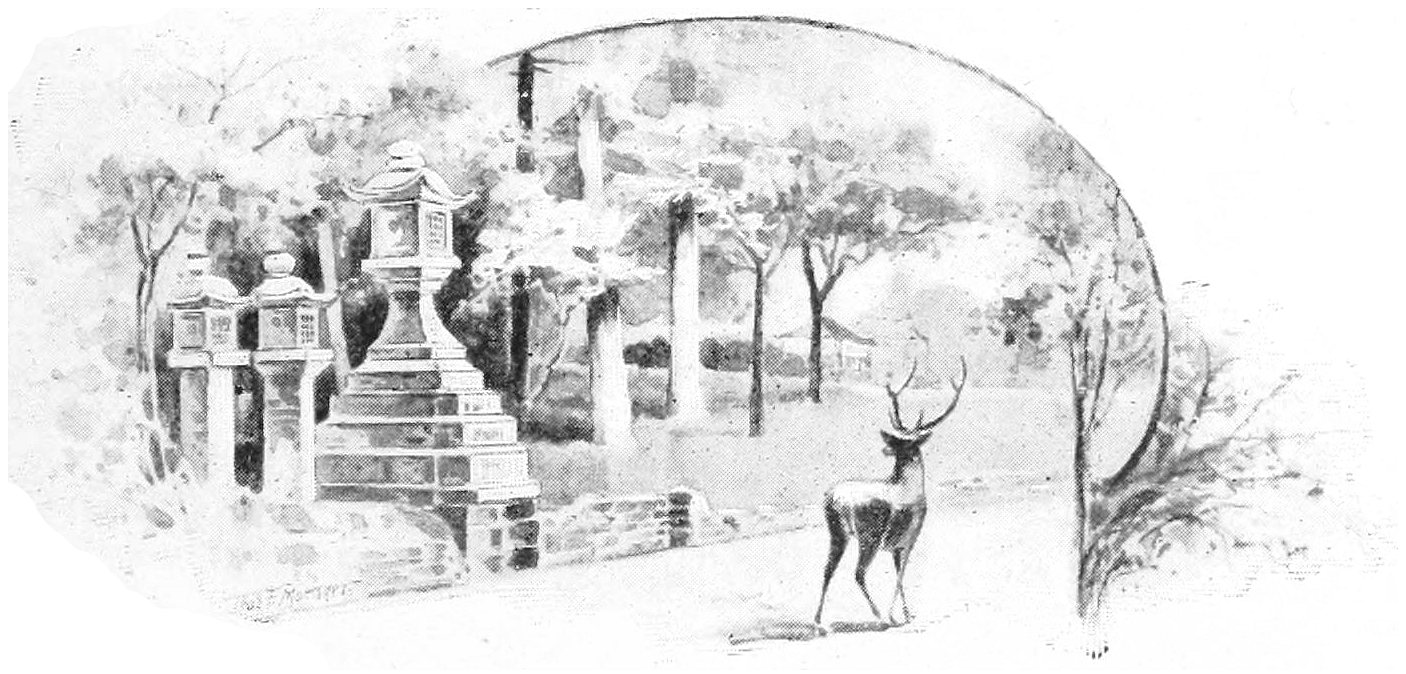

Perhaps your nature requires a different kind of excitement; if so, you may attend the races. These are carried on in the true English style, and are very generously patronised. The occasions are holidays in themselves, and offer a sufficient excuse for the closing of the banks and stores. A race track has been laid out back of the residence portion of the city, and has an additional attractiveness in the fact that it commands an excellent view of the elusive Fuji. Foreigners turn out in full force, many coming down from Tokio. Often the Mikado honours the affair with his presence; he is always an interesting addition to29 any event, but he is an inconvenient person to have around, owing to a peculiar phase of Japanese veneration. No one may hold his head higher than the Mikado, else his sacredness would be outraged; and the many attempts to make him tower above the rest of the populace frequently produce amusing complications. Such a predicament happened a short time ago, when the Mikado was on his way to the races. An American with more curiosity than knowledge of Japanese religious rites, thought it a fine opportunity to catch a glimpse of the royal person, and so elevated himself upon a box near by and awaited the procession. He had stood there some time, flattering himself upon the difference between American and Oriental intelligence, when his peace of mind was suddenly disturbed by a series of shouts, which, he divined from the30 gesticulations, were directed towards himself. The constant motions to descend he regarded with a true Yankee stoicism, and it was not until the box was pulled from beneath his feet, that he was induced to pay the proper respect to the Majesty of Japan. The races themselves, with the little shaggy horses, have proved to be a very fertile means of entertainment. The riding is done to a considerable extent by the little Japs, who take to it quite readily, and make very acceptable jockeys.

One of the most delightful events in the social life of the foreign residents of Yokohama is Regatta Day. All their pent-up enthusiasm seems to let itself out, and the numerous visiting vessels contribute to a most entertaining scene. The contests take place in the spring, and preparations are made many days in advance. The 33vessels in the harbour are gayly decorated with flags and streamers; the wealthier classes turn out in their carriages, and the Bund is one mass of ladies and children in white dresses, intermingled by the dainty kimono-clad form of the Japanese. The hotel is impartially adorned with the colours of every nation, and the piazza is a varied scene of moving gayety. Every one does not attend the races behind the bluff, but Regatta Day is the one event of the season, and furnishes an excuse for considerably more than the nautical contests. The races themselves are perhaps not of sufficient importance to justify all this excitement, but Yokohama is very different from New York harbour. The day is bound to be clear, the sky is always of Italian deepness, and the sun never fails to shine down on the lively scene with a refreshing glow.

34

Domestic life in Japan has its inconveniences; but it has also its more advantageous side. Do you wish to live in splendid style on a small income? You should dwell in the land where servants cost only four dollars a month. The life of the foreign residents in Japan is somewhat mysterious; the position of the mistress of the household eluded my investigations for a long time. “What do you do?” was a question I asked many of the ladies, but never received a satisfactory reply. After much thought I have come to the conclusion that the only thing your position requires of you is to sit in your parlour and amuse yourself as best you may; and when you wish anything done, simply clap your hands and cry “Boy.”

This last word is the keynote to the situation. As soon as you have35 learned the word “Boy,” you have solved the whole problem of the European household in Japan. Everything centres around this important dignitary, whom even foreign innovation has not succeeded in abolishing. The “Boy” has edged his way into every foreign home in Japan, and his position is as firmly established as the homes themselves. He is one of the most indispensable domestic functionaries that have figured in history. But, in the first place, an excusable mistake must be corrected. The “Boy” is not a boy at all, but is simply called so in deference to custom. Most of the “Boys” have large families of their own, and I have seen many with white hair and wrinkled faces. He never seems to resent this youthful title, and would feel very much bewildered should you suddenly begin to call him “Man.”36 He appreciates his important position very keenly; he is no ordinary servant, but a man with thoughts of his own and the dignity of a household resting upon his shoulders.

The whole thing is managed somewhat after this style: You receive an intimation that a few friends will dine with you, and this intimation is all about which you need trouble yourself. You never begin to think what you have to offer your guests, for you are not supposed to know anything about such things. You simply sit down, clap your hands and shout “Boy!” In a few moments the door will open and the person who bears this title presents himself. He approaches, bows lowly, and makes a single ejaculation,—

“Heh!”

This simply means that he is all attention. If you are inexperienced,37 you will get the idea that this word means “yes.” But you will have many opportunities later to correct your mistake. The Japanese says “Heh!” to signify that he is listening, and there his responsibility ends. He never commits himself.

“I am going to have two friends to dinner,” you reply, and you give their names.

“Heh!”

He bows again, turns around, and leaves the room. That is all you have to do until the dinner hour arrives. Never make any suggestions; the “Boy” would be completely mystified by such a proceeding. The way he goes about everything is very picturesque. You understand that the man who has just made his exit is the head “Boy” or No. 1 “Boy.” He goes downstairs and begins to examine the possibilities for the dinner.38 Very likely he finds something lacking. If so, he immediately makes a call on No. 1 “Boy” next door, and returns with the supplementary dish needed to make the dinner a success. There exists a kind of free-masonry among the “Boys,” and what one cannot find in his own domain he feels no hesitation in borrowing from a friend near by. Your “Boy” then visits the “Boys” of the friends who are to dine with you and makes many interesting inquiries. He asks what their favourite wines are, and never hesitates to request a loan of their plate and linen. He usually also demands the cooks of your friends, and leads them off to your house in order that the dinner may be more satisfactorily prepared. Thus it happens that when your friends arrive they are very likely to eat your dinner cooked by their own servants and to see their39 own china and linen gracing your table. More than this, the “Boys” of your friends are usually present and attend to their wants. The order of things will be reversed when you dine out.

You see this “Boy” is a very convenient and important person, and as he is usually an intelligent man, everything goes smoothly on. Occasionally a difficulty arises owing to the fact that he has not a sufficient regard for the mistress of the house, and indeed it is a question whether he ever looks upon her as such. Japan has not yet learned to rate women at their true worth, and it is this sentiment that is at the bottom of the “Boy’s” reluctance to take orders from anyone but a man. Most of them are gradually coming around and will obey you, but a few conservative souls still remain. I had a friend who40 possessed a very worthy “Boy,” whose character was blemished by this one defect. She told him one day to remove a plant into an adjoining room. He bowed, said “Heh!” and departed. Some hours passed, and the plant was still unmoved. He was called in again, again he bowed, ejaculated the usual “Heh!” and left the room. My friend tried this several times, and succeeded in getting more bows and more “Hehs!” but the plant remained where it had been. She spoke to her husband about the matter, who called in the “Boy” and told him to remove the object of the dispute. The “Boy” bowed, said “Heh!” took the plant and carried it into an adjoining room. When asked to explain his previous disobedience, he said: “I will do it if master wishes it, heh!” and with a profound obeisance he retired.

41

Another great enemy to domestic life is what is known as the “Squeeze.” This is not peculiar to the household, but is found in every part of the Japanese social system. The whole business of the country is run on a commission. Every time you buy anything, you have to pay several “squeezes,” or commissions, to the various people concerned in the transaction. No “Boy” will run an errand without his “squeeze,” and he uses a great deal of liberty in your domestic accounts. Should you send him out to buy a bouquet of flowers, he would always charge you as well as the florist a “squeeze” in the reckoning. The butcher who deals with you has to pay him a certain amount, and of course you are the one who suffers in the end. This is altogether independent of the profit of the goods, and often is little more than a personal42 consideration. Foreigners have made war many times against the “squeeze,” but their efforts have been unsuccessful. It seems to be a second nature with the Japanese; it is one of those good old customs that they will not let die. I had an iconoclastic friend who resolved that there should be no “squeezes” to impede her domestic calculations, and who decided upon a reform. She thought that she would begin modestly at first, and hit upon the lamps to experiment on. There is a very humble person whose occupation it is to go from door to door and fill all the lamps of his customers, but his pay is not too small to necessitate a little “squeeze” to the head “Boy” for the privilege. The lady in question decided to hire this boy directly, and for a time she thought the plan was succeeding remarkably well. One day, however,43 she found that her head “Boy” had a pleasing custom of making a round of the lamps every morning and removing a certain quantity of the oil. By selling what he procured this way, he recovered the “squeeze” of which he had been defrauded.

The specialising tendency of the people is another thing particularly irritating to those who live in Japan. Such a thing as a man-of-all-work who goes around picking up odd jobs is an unknown phenomenon. You must have a large number of servants or you will get nothing done. A certain “Boy” puts the coal in the stove and another cooks the dinner. But the “Boy” who does the cooking would never touch the coal, if you had a dozen guests waiting upstairs. It is a matter of caste, and one occupation is immeasurably superior to another; at least, in the opinion44 of him who practises it. You have a “Boy” who takes care of the horses, but he would not understand you at all should you ask him to drive them. If a light needs turning up, and you request your head “Boy” to do it, he would never think of obeying. He would rather run two blocks to fetch the menial whose duties are along that line. I was told a story of a lady on shipboard, who requested her attending “Boy” to close an open port-hole. He answered “Heh!” and went out to search for the servant who attended to such matters. It took him fifteen minutes to find him, but he finally led him triumphantly in, and the port-hole was closed. It had never occurred to the former that he ought to do it himself; he had not been educated to that position in society, and it would have grated harshly against his sense of45 the fitness of things to suggest that he was fully qualified to close port-holes. Every Japanese has a great pride in his task, knows his own place, and thinks that the greatest requirement of a virtuous life is that he does not interfere with the duties of others.

46

49

You will have many friends who will give you a great deal of kindly advice before you leave for Japan. On no point will their suggestions be as plentiful as on the mooted question of shopping. With a knowledge born of experience, they will inform you that these almond-eyed Orientals are not the guileless souls that they may seem, and that50 beneath all their gentleness of manners there lies a keen wit which will tax your American sharpness to the utmost. They may perhaps go further and descend to particulars, and you will have the opportunity of learning the number of tricks you will be subjected to and the large amount of wares that are being reserved until you land. All this advice you will carefully note, and think that when you start down the streets of Tokio or Yokohama you have an advantage over your compatriots, and that you are secure from the dangers of early shopping in a new country. You have all the words of your friend in mind, and decide to wait several days before you make a single purchase. At about this point of your self-congratulations you will catch sight of a small two-story building, and for some inconceivable reason be51 attracted within. Perhaps it is the dainty sign over the door; perhaps the smiling face of the host, who looks upon you with so inviting an air; perhaps the ever-attendant evil spirit of shopping that has begun to work his baneful spell. At any rate, in a short time you find yourself in a small room surrounded by a delightful collection of bric-à-brac, with a cup of tea in your hand and the happy face of the proprietor beaming down upon you. An hour or two slips by, and when you leave you will suddenly discover that you have ordered a large part of the merchant’s wares, and that you have a neat little bill smilingly presented to you. It is not until you are in the52 street again, or perhaps easefully reposing in your room at the hotel, that the whole terrible truth flashes upon you. You have done just what you were told not to do, and just what you had considered yourself firmly guarded against. A horrible suspicion crosses your mind. What if all those charming things you bought belonged to the worthless class your friend had so conscientiously warned you of; and what if the genial smile of the merchant were but the mask of a deceiving heart? In a day or two your suspicion will have been confirmed. The goods that you so rashly purchased will be given as a present to your attending “Boy,” and your shopping henceforth will become rather a scientific than an emotional affair.

The Japanese are rapidly learning the proper use to be made of tourists,53 and are always ready to receive them. You will not have been long in your room when a gentle knock will be heard at the door, and a most obsequious Oriental will make his entrance. He will bow with the utmost profoundness, and present you with a card which contains his name and crest,—usually in the form of a teacup or fan. You return his gaze as kindly as possible. He says: “Please you come see my shop,” makes another bow, and retires. The whole scene is not unpleasing to you, and you are thinking it over as an interesting experience when another knock is heard. Another Jap of the same appearance as your former visitor now enters, makes a similar bow, gives you his card, says: “Please you come see my shop,” and as gracefully takes his leave. If you are wise you will now determine to receive no more54 callers, for this sort of thing will be kept up all day, and you will have a varied assortment of cards before the evening comes. Your new friends are most scrupulously polite and have no air of bluster or eagerness; but they are quietly persistent, and would not think of passing you by without giving you a chance to learn of the advantages of their house. They keep a careful watch for the arrival of every new steamer, and trace all the passengers to the different hotels. The reputation of the American as the generous spender of millions is as firmly fixed in the minds of the Japanese as in those of less distant lands, and to them they give a large amount of attention.

Indeed, it is generally assumed by everyone you meet that you have come to Japan to shop, and the kindest favour he can do you is to55 show you how and where you can do so with the best results. Even the humble coolie, who carries you around in your jinrikisha, firmly believes this, and thinks that if he is in a small measure the means of your making a happy purchase, his way into your affections is won. If you tell him in the morning that you wish to take a ride, he will tuck you comfortably in and start at a rapid pace towards the main thoroughfare of the city. You will be quietly enjoying everything you see, and will, perhaps, be somewhat surprised when the coolie suddenly stops before one of those two-story buildings with which you are now so familiar, and glances up into your face with the most self-congratulating expression. If you do not immediately descend and enter the shop, he will suddenly become crestfallen, and wear a look that56 means that you are quite unable to appreciate a favour, and do not know a good thing when you see it. The chances are, however, that you will feel an invisible force attracting you within the little shop, and so leave your coolie without, a happy man.

If you are in Japan during a period of silver depression, you are a very unfortunate person indeed. You have perhaps visited the bank the day before and changed a thousand dollars of your gold into two thousand dollars of silver, and this unexpected increase in your worldly possessions is the very worst thing that could have happened to you. For you are likely to get the idea that you can now afford to be a little extravagant; that you have just twice as much money as you had before, and that you would be a very stingy person, did you not scatter a little of57 it about. You have probably, however, one advantage in the fact that you have shopped before, and do not think that there is much danger that the experience of a few days ago will be repeated. By this time your respect for your anxious friend, who so vainly gave you his advice, has greatly increased; and you decide that when you return you will make a point of breathing the same gentle counsel in the ears of all you meet who are on their way to the land of the cherry-blossom and the almond-eyed sharper.

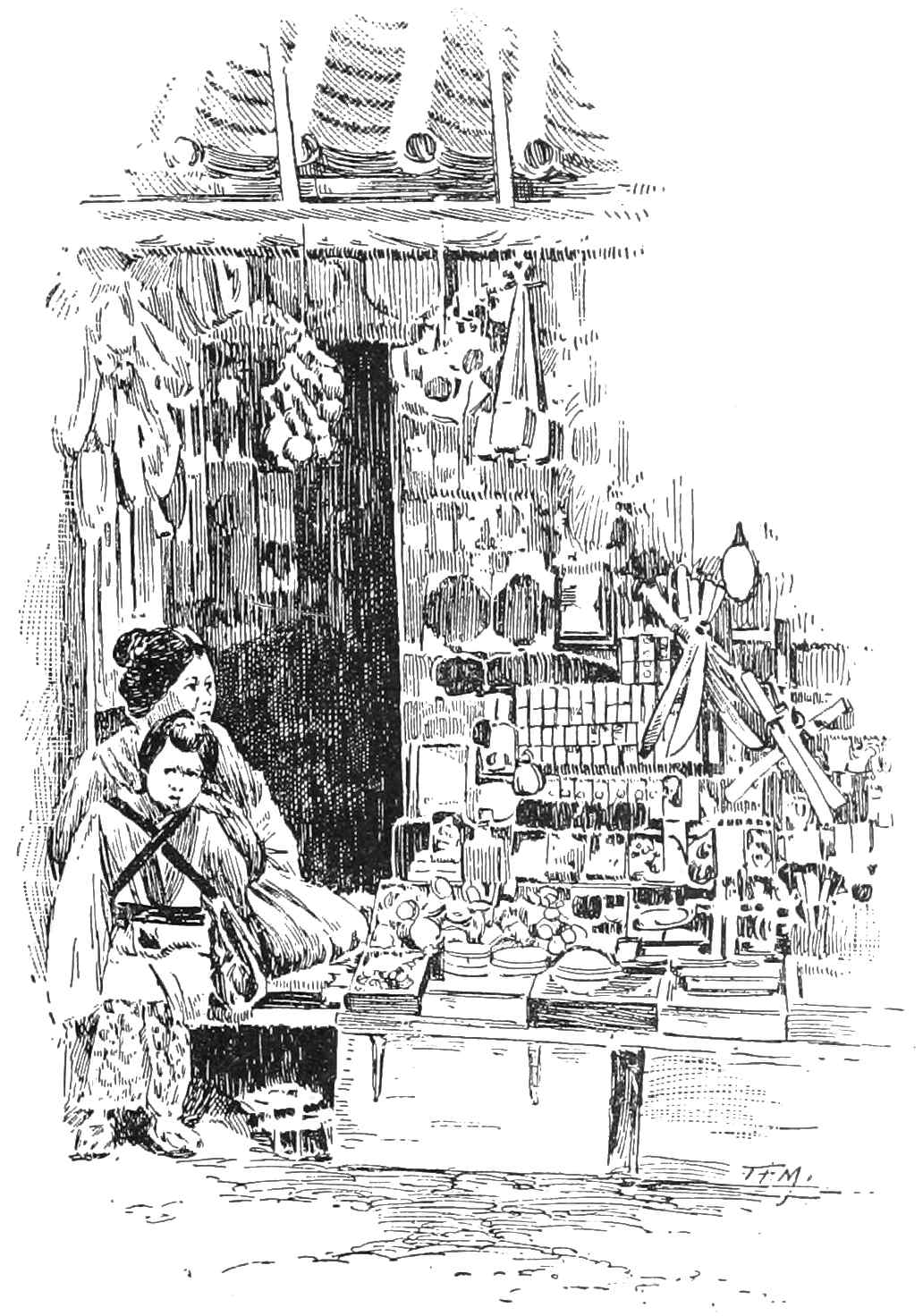

The street in which most of the shops are found has the delicious local flavour that seldom fails to entice the unwary purchaser. The thoroughfare is very narrow, and is lined by two rows of shed-like buildings adorned in front by hanging cloth signs. Many of these signs are inscribed with the name of the58 keeper, who does not confine himself to the Japanese characters, but frequently spells himself out in English,—a thing that you are likely to take as a personal compliment to yourself. The cloths are also sometimes covered with emblematic figures representative of the goods sold within. There are grotesque and unheard of birds; armour, and paintings representing the god of money and good luck. The lower story of the house is probably open to the street, but it is sometimes hidden by a curtain of blue and white, which an attendant lifts to allow you to enter. Really, there is nothing in all this that tells you of the treasures that lie beyond, but you have a sensation which for the time being seems uncontrollable. Sometimes, on a holiday, the whole scene may be changed, and by the addition of a large number of paper59 lanterns and clusters of wistaria and cherry-blossoms an element of festivity is introduced. But the grotesque methods of advertising that you are familiar with as an American, are unknown to the Japanese, and utterly distasteful to their sense of propriety. Even in the marking of prices they exercise the greatest taste, using little thin strips of cloth with the cost of the article painted in blue. This, however, you do not see until you enter the shop. The proprietor will receive you with the utmost politeness, but there is no sign of unpleasant aggressiveness in his behaviour. He views your visit both from a social and business point of view, and esteems your notice of him as a personal favour. Even though you do not buy, he always takes pleasure in showing what he has to sell. He likes to have you show some appreciation60 of his goods; and if you have done this, you can leave without buying a thing and be sure of as warm a welcome when you return. One demand he will make of you, and that is, that you take plenty of time. He likes to talk and discuss, and seems dissatisfied unless you consider the transaction as one of great importance and worthy of much meditation. The hurried visits that he sometimes receives from Americans, who rush in and wish to do everything in a few moments, utterly bewilder him. He is willing to spend a whole day with a single customer, and never shows any impatience except when you are in a hurry. He greets you with a profound bow, and smilingly places his shop at your disposal. He usually has one or two assistants who keep at a respectful distance until their services are required.61 The host is very quiet, and does not begin to praise everything in the room, but calmly calls your attention to each article, and relies upon your own good taste to see its virtues. His first floor is usually given up to a large display of ancient62 armour and swords, each piece with a history of its own, and speaking terrible tales of the good old fighting days of the Shoguns. There are grotesque and grinning masks that the most stoical temperament cannot gaze at without shuddering, and frequent representations of the Japanese conception of the Devil that make you suddenly turn your back and become interested in something of a less religious aspect. The weapons are what delight many a warlike spirit; Japan has always been famous for its steel, and many of these swords might make one think that the days of the famous blades of old had returned. All these are now, of course, as antique to the Japanese as to ourselves, for their usefulness, except as interesting curios, has been replaced by the more prosaic implements of modern warfare.

63

If you are a woman you will not be likely to buy any of these articles of war, and you will find it a relief to escape the fiery eyes and low-hanging tongue of that mask in the corner. The proprietor calls your attention to a rickety staircase, and invites you to ascend into the second story. By so doing, you will soon find yourself in a little room which reveals altogether a different sight to the one below. You have left the domain of war and blood, and are now surrounded by suggestions of religion and art. There are Buddhas of every kind,—wooden, bronze, and gold; there are dainty little tea-pots, porcelains, candlesticks, and altar-pieces, to satisfy the most exacting taste; there are highly-polished mirrors gracing the walls, and another collection of swords, of a perhaps less warlike appearance than those below.64 The scene has graceful touches, for the small children of the family are huddled together on the floor, amusing themselves with such Japanese playthings as grasshoppers and crickets. These are their dolls, and they would never lay them aside for the less animated toys of the Western world. The wife of the proprietor is always at hand, who supplements the bows of her husband with dimpled smiles of her own, and who treats you with a respect that is not too distant to be friendly. She is sitting on the floor in front of a small hibachi. You have not been in the room long before you hear that little quiet steaming that you now know so well, and soon the little woman rises and, with a smile and bow, leaves the room.

All this is very delightful, and it requires all your presence of mind 67and the recollections of a previous day’s experience to keep you from falling into a snare. You know very well that all these dazzling things about you have more glitter than gold, and that they are manufactured expressly for unknowing foreigners, such as you are assumed to be. You may be sure, that there are finer goods than these, kept carefully out of sight. The merchants never display their choicest wares on the shelves, but have them neatly tied up in boxes in an adjoining room. In some way you hint to your suave friend that you have shopped before, and are perfectly familiar with the peculiar tricks of the trade. All this he receives with an intelligent smile, and asks you to seat yourself. If you look around for a chair you will betray yourself as less experienced than you claim, so you had better68 drop at once on your heels; for by doing so, you will immediately gain a point in the good graces of your host.

And now a delicate patter is heard on the stairs, and the little woman who left a few moments ago returns. She has a small tray full of cups and sweetmeats, which she deposits on the floor as she sits down in front of you. The proprietor joins the group, and occasionally one or two of the children forego their grasshoppers and crickets, and supply the sole element lacking to a very pretty domestic picture. The tea is now poured out; you are expected to drink several cups, else the shopping that is to follow would not be a success. The host says many pretty things, rejoices at the fact that you are an American, and thinks your country the crowning triumph of69 modern civilization. He trusts that your health is as good as your rosy cheeks and sparkling eyes would lead one to believe, and that nothing will happen to make your journey in Japan anything but one of the delightful memories of your after-life. Meanwhile you sip the pale drink, nibble at the cakes and candies, think your charming new friend not the crafty schemer you know him to be, and are almost led to believe that you have come not so much on business as for the sake of making a morning call.

But now the host claps his hands, and an attendant appears from a rear room, bearing several neat-appearing boxes in his arms. The goods that you have come to buy are in these little square affairs, but you are almost as much interested in the boxes themselves as in what they contain.70 They are daintily made of light wood, and are not disfigured by the clumsy nails or cracks that do not annoy our less æsthetic merchant of the West. When the attendant begins to remove the wares your appreciation of the artistic shopkeeper increases, for everything is daintily wrapped up in cloth of alternate red and yellow sides. Japanese paper is of a much choicer kind than ours, but no self-respecting merchant would ever think of using it to cover his wares. You become very familiar with this yellow cloth before you leave the country, for it is as generally used as our less artistic substitute at home.

Perhaps you know what you want and perhaps you don’t, but it will make no difference to the proprietor, who prefers that you take plenty of time. He says very little in praise71 of what he puts before you, though occasionally he will unaggressively remark on the particular qualities of an unusually charming article of bric-à-brac or roll of silk, or drop a word on the depth of colour and finish of a piece of gold lacquer; nor is he willing to let an occasional piece of Satsuma pass by without calling your attention to its delicate shade and crackle.

This goes on for some time, until your eye alights on something that you must have, and then the most interesting feature of the performance begins; for a Japanese merchant is entirely out of harmony with the one-price system of the West, and would never think of asking the actual amount for which he will really sell his wares. He has his price, it is true, but this is only for those of small experience, and from others he seldom hopes to72 get more than one-third to one-half of what he asks. Never think, however, that you get the best of him, for there is always a limit below which he will never go. Friends of mine have reached this limit, and their most persistent efforts have never succeeded in making the shopkeeper less firm. They would drop into the shop morning after morning and renew their offer; the merchant would smile, but remain unshaken. If you stay very long in Japan you will become so accustomed to this haggling practice, that you will acquire a habit you will have difficulty in shaking off. When, after I returned home, a dry-goods-store clerk told me that the price of a certain article was fifteen dollars, I could hardly keep from replying, “I’ll give you ten.”

“How much will you sell me this for?” you inquire at last, perhaps73 picking up a piece of delicate bric-à-brac, which in your fond imagination you already see gracefully reposing on your library table at home.

The shopkeeper looks at it sharply with his little eyes for some time, then answers with a smile,—

“Sixty yen.”

Your hands go up in horror. “What?” you frantically exclaim; but the merchant answers you with another smile. Your emotion, however, is as feigned as the shopkeeper’s apparent firmness, for you know that it will be an easy matter to make him reduce the price,—the main question being whether your limit will be the same as his. The chances are that he will take just about one-third what he asks, and make a handsome profit then. So, you with the proper spirit decide to take him at an even lower figure and reply,—

74

“I will give you fifteen.”

The dejected air that suddenly spreads over his face is the kind of which a Japanese merchant is alone capable. He gives a great sigh and gazes at you with a look that seems to ask if you were born without a heart. His emotion is so great that he may even rise, walk around the shop, and examine several of his dearly beloved curios that have not been subjected to such outrageous treatment. He will soon return, however, and, with the humblest voice in the world and a sadly withered smile, announce his ultimatum,—

“Will give for thirty yen.”

You shake your head, push the rare object aside, and rise. You do not intend to go, but you begin to look at a different line of goods. The shopkeeper has not lost his politeness, and he takes the utmost pains75 in showing a large number of things that he knows you never intend to buy. During all this you and he occasionally cast furtive glances at the object of your disagreement, but neither one for a long time makes any allusion to it. Finally, the moment comes for you to go, but you decide to make one more attempt, which you know will be effectual. Picking up the dainty bronze, you say in an off-hand manner that you will give him twenty yen.

He looks at you sadly, and then again at the object in your hands. He casts his eyes at the ceiling, bestows a glance upon his innocent children playing with grasshoppers and crickets, all unaware that they are being defrauded of an inheritance, makes the bow of humiliation, and says with a short gasp,—

“I am resigned.”

76

After he has expressed his emotions in this unvarying phrase, his spirits seem once more to return. He smiles again in his old way, and his bows have the old obsequiousness. He even gives you another cup of tea, and in other ways betrays the secret satisfaction that he feels on having made a very good bargain. He follows you down the stairs to the awaiting jinrikisha and bids you farewell with the most touching “Sayonara” that you have yet heard. As you slowly ride away, the last thing you see is his bowing form in the door, and you give a sigh at the thought that all this display of friendship is but owing to the fact that you have probably paid twice what you should for the dainty bronze statue that is to adorn your library at home.

77

78

81

Of course, it could hardly be expected that our dinner would be Japanese in all its features, but it was not only our embarrassment at our surroundings that prevented it from being so. The appearance of our host himself in side-whiskers was enough to give an un-oriental air to the ceremony, and clearly indicated the peculiar mixture of the East and West of which his character presents82 a striking example. For he had visited extensively in America, where he had performed high diplomatic functions and carried back many of our traits, not the least evident of which were the whiskers above referred to. It was also unnecessary to use an interpreter when talking with him, as he spoke our language easily and well. As far as politeness went, however, he was entirely Japanese. I have an indefinite recollection of him as an embodiment of smiles and bows; his manners were perfect, his voice was of unusual sweetness. He had a keen mind and kept a watchful eye on us during the evening, in order that the strangeness of our situation should add rather a feeling of pleasantness than of discomfort.

He was a man far advanced in the ideas of new Japan, and he had gone83 so far as to adopt the European costume. But this evening he had cast it aside and appeared in all the splendor of a Japanese host. After we had travelled under the direction of a little musmee with a lighted candle, through a long, arched lane, we suddenly found ourselves before a small house and heard the most un-oriental of all words: “Good evening.” We looked up, and there stood our host between two wicker panels which he had thrust aside, with his handsome face smiling the most cordial of welcomes. He wore the conventional divided skirt, and over this a kimono of dark grey, caught together in front with a cord. His foot-gear was the customary sandals, which, however, he did not wear during the evening. Of course he did not have his wife with him, for even his progressive spirit had not reached the point where84 he could allow any feminine supervision of his feast. The hostess is unknown in Japan, where domesticity does not play the part it should. We had another proof of this in the invitations we received, which did not invite us to our host’s house, but to one of the swell restaurants of Kioto. For a Japanese to entertain at his own house would be a social barbarism.

The length of the Major—one of our party—was often inconvenient in Japan, and I saw him casting troubled glances at the house before which we found ourselves. It was very small, and when we finally entered he found it necessary to stoop in order to get in at all. We did not gain an entrance immediately, for we found an obstacle in our way in the form of the little musmee who had conducted us thither. Before starting,85 the two ladies of the party had debated for a long time what foot-gear they should wear, being faced by the American extreme of shoes and the Japanese extreme of stocking feet. They congratulated themselves that they had hit upon a happy solution, by wearing their party slippers; but when they arrived they found that they had miscalculated. As they stepped upon the platform and were about to enter the room, the little musmee’s hands went up in horror.

We can only appreciate her feelings by imagining our own, should one of our callers elevate his feet upon the parlor furniture. Should they desecrate her86 spotless white mats with their barbarous American slippers? Our poor host had his hands full, trying to pacify the little enraged body, and at the same time to act towards us as though this outburst was one of the regularly-planned features of the dinner. His ever present smiles were still more in requisition, and he could not bow enough in his endeavour to make us feel at ease. Suddenly, there came a calm; the little maid withdrew, and we were bidden in a most polite way to enter. The offended girl, however, sulked away like an angry child, and I am convinced that if we made any enemies in our trips in Japan, the little musmee at this restaurant was one of them.

This was the first Japanese house I had ever been in, and naturally I was interested to see what it was like. It was oriental in every way,87 though by no means an example of oriental splendor. At one end there was a platform on which incense was burning, and the walls were entirely bare but for two paper kakemonos. The floor was covered with white matting, on which were placed black velvet cushions. These were our seats for the dinner, and each of us was supplied, in addition, with a black lacquered candlestick. For some time we stood there waiting for the host to begin, but as we afterwards learned, it is customary at Japanese social functions for that dignitary to follow. He smilingly requested us to be seated as quietly as though he was bidding us to four hours in Paradise, and not to the physical discomfort—almost torture—that it proved to be. The ladies seated themselves with little trouble, but things did not go so well with the poor Major. His legs88 formed a large part of a body that measured considerably over six feet, and as those six feet had to be disposed of picturesquely in a sitting posture, you will see that we had almost a tragedy on hand. The Major made several spasmodic attempts, and finally threw himself down in a lifeless heap in a way that furnished our host new cause for smiles and bows.

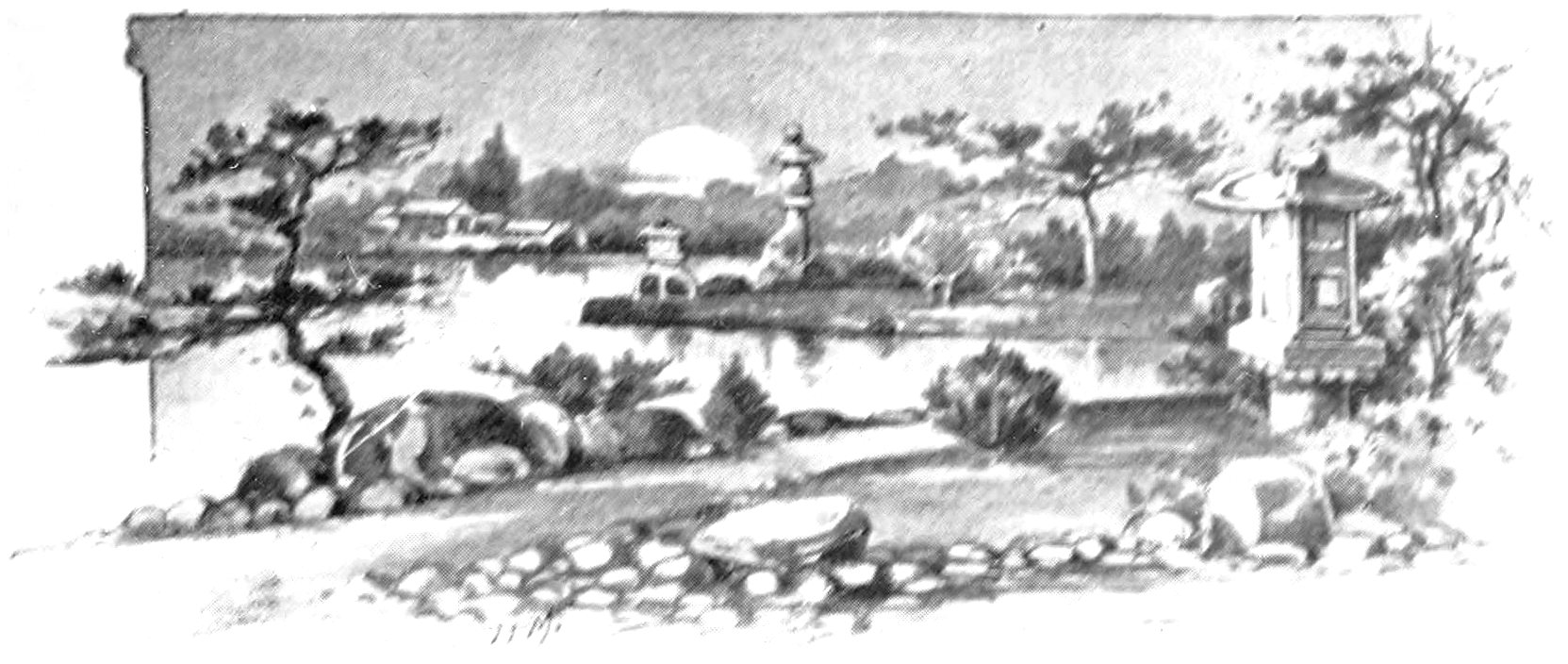

For all this the scene in which we found ourselves had its romantic side. It was early in the evening of a beautiful night in April, the Japanese June. The wicker panels of the house were thrown open, and the warm air came through, scented with the perfume of the cherry-blossoms and bearing delicate sounds from the garden without. We could see the stars from where we sat, and they had that warm, melting lustre that one sometimes sees at home, but89 which is characteristic of an oriental night. In front of the house was one of those famous miniature gardens that embody the dainty Japanese taste. A small, sparkling lake was bordered by the sacred cherry-trees, which were in full bloom; a passing breeze had blown many of the blossoms upon the surface of the water. The shores were covered with dwarf trees and a few sprays of pansies. All of this we could clearly see, for the moon gleamed down upon the scene with just enough brightness to render all distinct without removing any of the enchantment. From the distance90 we could hear the faint tinkling of a waterfall. Even the Major’s uncomfortable state of body could not prevent him from catching the poetic flavour of all this. But there was more romance ahead. We all felt a disappointment when our host dropped the oriental manner of salutation and simply bowed profoundly; but now we were soon to have Eastern respect at its fullest. Two musmees entered, and, falling on their hands and knees, touched their flower-bedecked heads to the floor. In this respectful attitude they remained before us for some seconds, while we wondered whether the occasion demanded any action on our part, when, suddenly, they rose and presented us with handleless cups full of tea—for every dinner in Japan begins with tea. I looked at the host in despair. “Ah! I will explain,” he said, with91 a laugh, and he did so. This is the way you do it: you place the cup in the palms of both hands, twist the fingers into a supporting position (I do not yet fully understand it), and drink between the thumbs. If you are well-enough bred, you will do this with the utmost ease; but if you are not, you may land the tea in your lap, break the china cup, and be put down as an extremely low person. Of course, the fact that we were foreigners warded off any harsh judgment; and besides, I really believe we all of us did manage somehow to get through the crisis in a way that was not entirely disgraceful.

Japanese æstheticism extends to their dinners, which are extremely graceful affairs. Our host, for example, had divided this dinner into four parts, each typical of a season of the year. In this was a hidden92 compliment; he intended thus to express his regret that we were unable to spend the whole year in Kioto, and his hopes that this evening’s pleasure would offer as good a substitute as possible. And in spite of our uncomfortable attitudes and the strangeness of many of the dishes placed before us, I do not think he was entirely unsuccessful. Not the least pleasant part of the dinner, for example, was that which immediately followed the tea drinking. We had hardly handed the cups back to the musmees, when they gave to each of us a beautiful wicker basket filled with flowers,—that, at least, is what we thought they were, until we discovered that they were without smell. In fact, it took us some time to find out that they were not flowers at all, but most exquisite candy imitations. They were more than93 confectionery—they were true works of art.

But there were other surprises in store for us. As we sat admiring these delicate creations, the doors at the rear suddenly opened, and a living wave of colour came fluttering in. At first we could distinguish nothing but a flock of miniature bats, storks, and other creatures which figure exclusively in Japanese natural history, disporting themselves among dainty representations of purple violets, dandelions, and white and pink cherry-blossoms. After recovering from our first surprise we saw that these were small pieces of embroidery on a background of pale greys and shaded blues, and then we caught sight of waving loops of hair in which were intertwined sprays of flowers and fancy pins. This delicate yet somewhat confused mass drew nearer, and we saw94 five little faces painted entirely white with the exception of clearly-defined spots of red under the eyes and lips, that were made particularly small by a skilful handling of the brush. We could but ejaculate one word: “Geisha!” These were the famous dancing girls of Japan, who lead, I fear, not too happy lives in furnishing much of the enjoyment of Japanese social life. It is only ordinary people who frequent the theatre in this country, and it falls upon these little creatures to furnish the higher classes a large part of their amusement. They dance, they sing, they joke, act as waiters, and are generally expected to supply the element of gaiety without which no dinner can be thought complete.

The Japanese do not walk, they flutter; they do not sit down, they sink. Each of these delicate bits of95 humanity bearing a small lacquered tray sank down before the guest she was to serve. They were continually laughing and chattering among themselves, making naive criticisms of our costumes and of ourselves—for the geishas are given a great deal of freedom. They were particularly inquisitive about the ladies’ dresses, and even went so far as to ask, through the interpreter, the cost of them. They also were anxious to know whether the Americans made them themselves, and how long it took. These materialistic thoughts changed when they caught sight of the ladies’ diamonds, which they romantically imagined to have grown on trees. They made endless remarks about us which we did not understand, and from the interpreter’s unwillingness to translate many of their speeches, I am96 sure the little fault-finders saw much in us to criticise.

(Larger)

And now the dinner began in earnest. By our sides we discovered mysterious packages done up in paper, which we were horrified to find contained chop-sticks. This was worse than drinking tea between your thumbs. It was my first experience with these utensils, and I hardly thought myself in a well-chosen place to learn their mysterious qualities. I was greatly surprised, however, to find that it was not so difficult as it looked, and that chop-sticks,97 after all, are not the impossible things the untutored suppose. We had a hard dish to begin on; for after we had got our chop-sticks in battle array, the geishas startled us by bringing in soup. More smiles from the host, and more explanations. All you have to do is to eat the solid part with the chop-sticks and drink the liquid as you drink tea. The soup was politely christened “Congratulatory,” and was made of green turtle, which is popularly supposed to live a thousand years—another compliment for us. And now that I have begun the menu, I may as well say that the succeeding dishes included fish and eels, and an unprecedented number of soups, cooked à la Japonaise, particularly one made of seaweeds, in which their taste was by no means concealed. And there were wines, bomei, which the Japanese regard as98 a kind of medicine to prepare the stomach for the food, and saki, the national drink, not dissimilar in appearance and taste to a pale, dry sherry.

At this point we were surprised by the arrival of another guest. He had been invited to meet us as a friend of our host, but for some reason had been detained and had sent his excuses. He was clad in the same costume as our host and had also adopted the occidental whiskers, though his were grey. He was not sufficiently Europeanised, however, to omit the Japanese salutation, and consequently prostrated himself “on all fours” before us. He further mystified our minds by presenting each of our party with his card. We looked at our host in despair, who explained that it was customary on such occasions to exchange cards. But we had99 failed to bring any along, and therefore had to apologise ourselves out of the difficulty as best we could. Of course, our excuses met with the customary smiles.

“We hope you will be able to visit our country sometime,” one of us had inspiration enough to say through the interpreter the new arrival had brought with him.

“I have been there already,” he replied.

“And how did he like it?”

“It is a very beautiful country, and I hope to go back again sometime.”

Though the conversation was satisfactory, the inconvenience always occasioned by the use of an interpreter prevented it from being very lively. The next remark I remember was from the Major, and was not of so suave a kind.

“Say, if I have to sit here much100 longer, I shall never be able to use my legs again.”

All the evening he had been attempting to gain relief by a constant change of position, but his efforts did not seem to have been successful. We all of us were somewhat tired, but the Major had a great deal more to be tired than we. He had to compose himself, however, for one of the most distinctive features of the dinner.

There was a slight pause after his remark, and we began casting glances at one another and wondering what was to come next. The pause at an American dinner we should consider an awkward one, but our host did not seem to entertain any such idea. Suddenly we heard two snaps that apparently came from stringed instruments, and at the same time the panels in a rear room were101 drawn aside. We were taken somewhat by surprise, for we were not acquainted with the fact that a small theatrical performance is one of the usual accompaniments of a Japanese dinner.

Two of the geishas began to play on the samisen, the Japanese banjo, and the koto, a kind of elongated harp, picked with ivory tips. At102 the same time one of the girls came out in the centre of the room, and we had our first sight of Japanese dancing. While she went through the movements of the “Reign of Spring,” the two girls with the instruments began singing in that falsetto key which it takes an educated taste to appreciate. They sing so shrilly and the notes they strike are so unnatural, that it becomes a very painful exercise, and will frequently bring tears to the performer’s eyes. And how about the dancing? One who is accustomed to the serpentine mazes of our occidental skirt dancers and who likes that sort of thing, may find it hard to enter into the spirit of her Japanese contemporaries; but if you delight in gracefulness in any form, these little geishas cannot fail to please. Their costume plays an important part in the series of posturings103 that makes up the dance, and no small amount of the success achieved depends on the proper manipulation of the fan. You can get the best idea of what it is like, by imagining a succession of dainty tableaux in which the changes are made before your eyes.

After sitting in a Japanese posture on American legs for four hours at a stretch, it was with some difficulty that we finally arose and prepared to leave. As we went out into the night we were followed by a veritable chorus of “Sayonara,” which is the Japanese word for “good-bye.” We were somewhat surprised to be followed by the little musmees, bringing as gifts, neatly tied up in boxes, that portion of the dinner we had not eaten. There is something delightfully original in that idea. The smiles and bows of our host were succeeded104 by those of his friend, whom he had sent to escort us safely home. His courtesies did not stop here, for he called on us the next morning to thank us for the honour we had done him in accepting his invitation to dine,—a notable expression of the refinement of Japanese politeness.

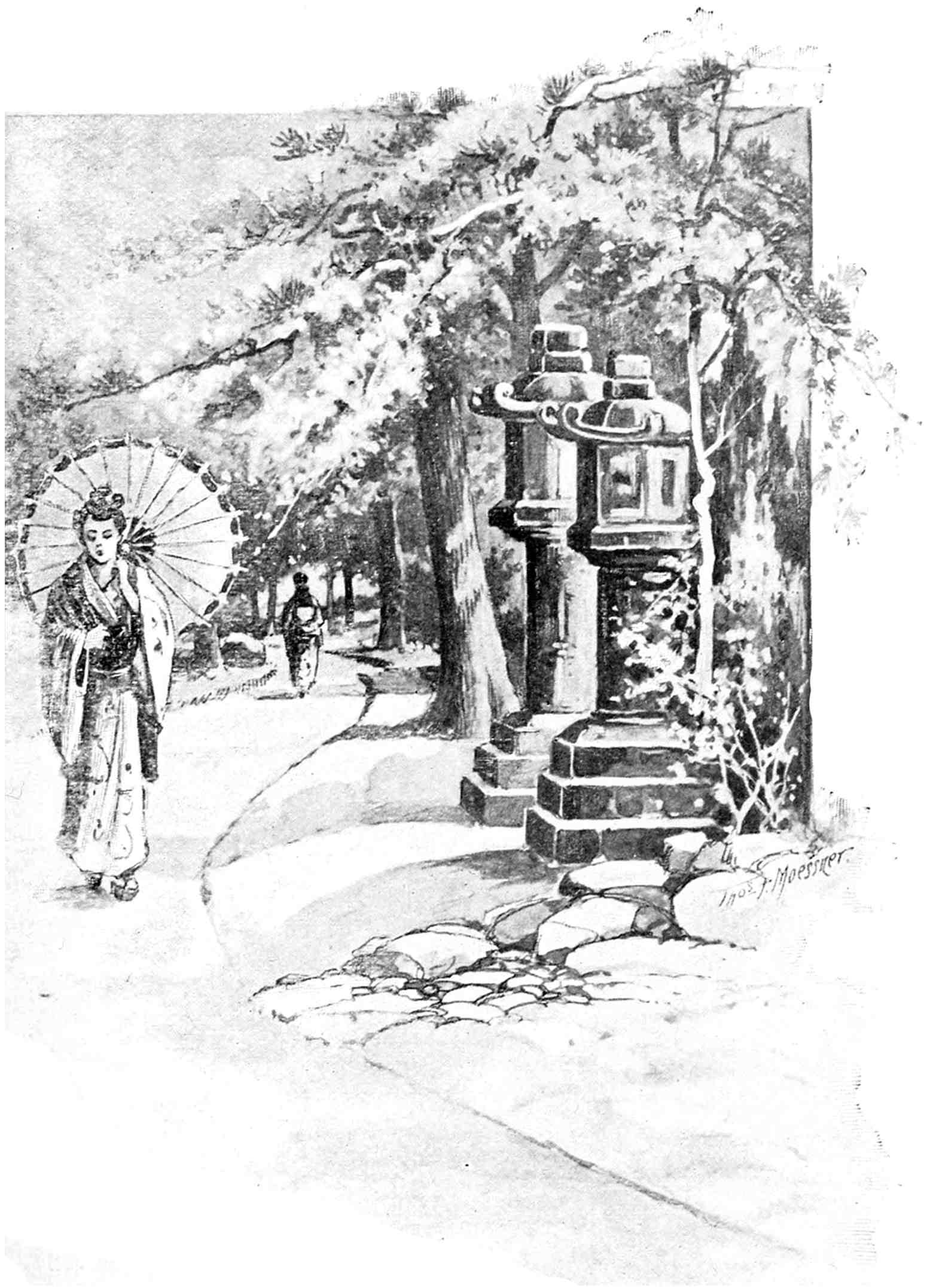

The night had grown still more beautiful during the four hours we had spent within, and we caught many interesting glimpses of local colour on our way to the hotel. The air was warm, the sky clear, and the brilliantly-lighted parks were filled by proud Japanese fathers and mothers with their prattling children. Men and women were stopping under the cherry-trees that were in full bloom, gazing upon the sacred blossoms that have been dear to Japanese hearts for so many centuries. We went by one of the temples, standing on a hill, the105 approach marked by a succession of bright red gateways. Under the light of the moon, this ancient structure, which for ages has been the heaven of aspiration and love for so many hopeful spirits of this land, had an air of the utmost impressiveness. The whole scene made us forget that we had been sitting for four hours on our heels, and called to our minds the fact that we had had one of the most enjoyable experiences of our lives.

106

109

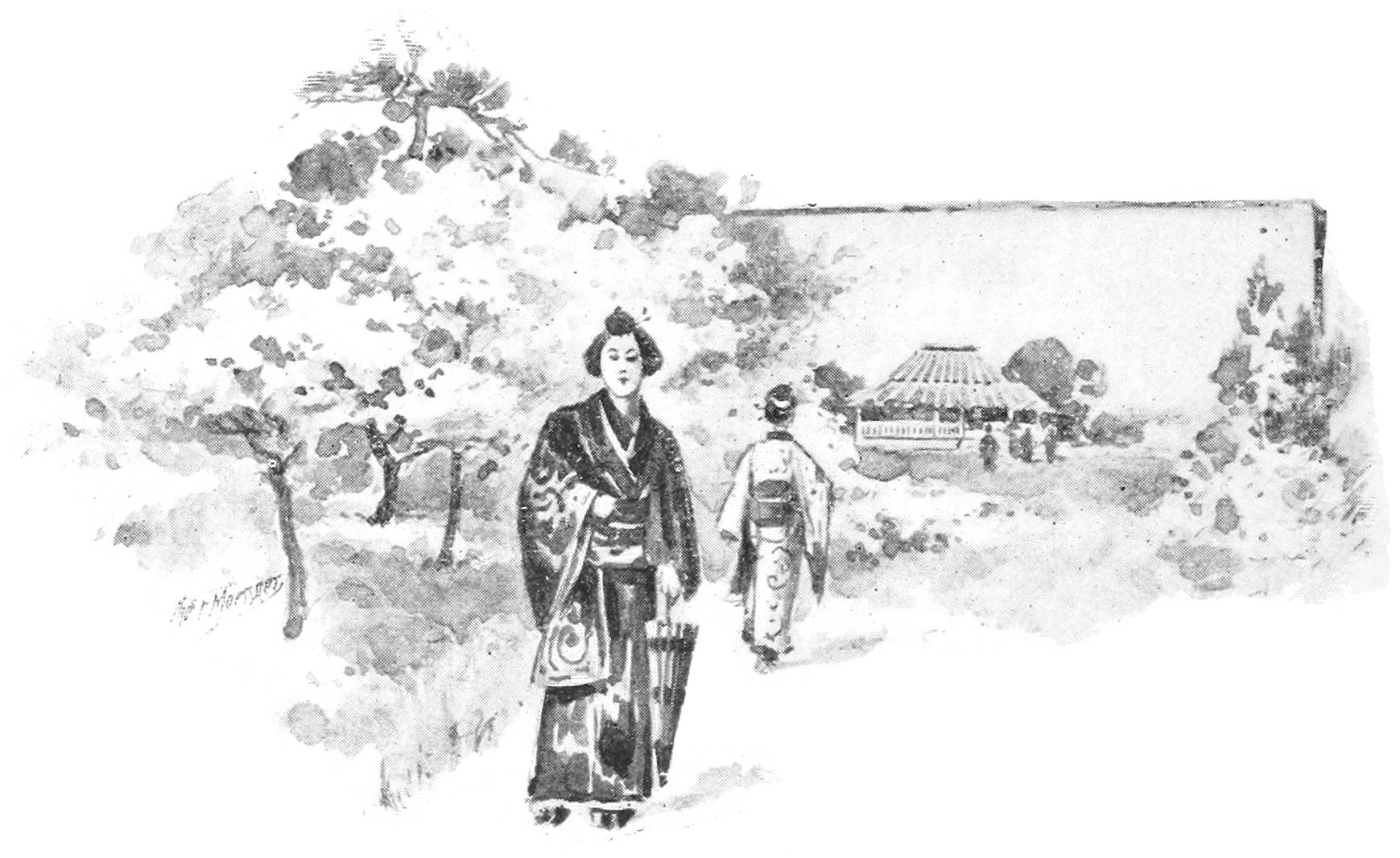

We suddenly found ourselves before the entrance to an unfamiliar by-street, and turned to our guide to inquire the meaning of what we saw. The huge red lanterns hanging in a perpendicular row from two high poles, evidently had a significance about which we were in the dark, and the exhibition of haste, which we observed on the part of these leisurely Orientals, surely was inspired by no everyday110 event. The girls were looking their prettiest with their hair filled with flowers and their pale grey kimonos tied with that magical sash-knot, which is the despair of their Western sisters. Along with them trotted their smaller brothers in bright-coloured flowing robes, their little heads cropped close with the exception of a solitary tuft. Fathers and mothers of sedater age and deportment displayed an eagerness that was equally strong, if more quietly marked.

Our attending coolie informed us that we had hit upon a festival that has particular attractions to the foreign eye. You have probably heard of those sacred cherry-blossoms that are so dear to the hearts of the Japanese, and which, with the chrysanthemum, are their chief floral pride. It is true that meddling foreigners have said that they are not cherry-blossoms at111 all; but that does not seem to prevent the delicate mingling of pink and white from being a very beautiful flower. It is in the month of April that they are to be seen at their best, and it is then that this æsthetic people assemble in different ways, and touchingly illustrate the part that these flowers play in their lives,—for the Japanese without their cherry-blossoms would not be the Japanese at all. When, therefore, the coolie informed us that all these people were on their way to see the famous cherry-blossom dance, we lost no time in mingling with the throng and following it down the lane-like street.

Everything here was a maze of Japanese forms clad in their daintiest robes, and Japanese faces flushed with eagerness and anticipation. Though æsthetic before everything else, the people have a keen eye for business,112 and the street was lined with booths full of knicknacks and toys of every kind. And here also were whole families picturesquely seated on their heels, sipping the everlasting tea. Pushing our way through the crowd, we drew up before a platform-like entrance, and were immediately met by one of the attendants, who presented us each with a pair of enormous white duck shoes. If you travel long in Japan, you will become accustomed to this sort of thing, and cease from experiencing any embarrassment or indignation at being requested to remove your foot-gear before stepping on a Japanese floor. The irreverent foreigner, however, unaccustomed to walking around in stocking feet, does not always see things from the Japanese point of view, and it has therefore been necessary at the temples and places of public amusement to have 115a stock of these ungainly foot-coverings for his benefit. The measure, of course, is a conciliatory one, and is intended to smooth the ruffled feelings of the Westerner without at the same time scandalising the sensibilities of the Japanese. We had had many similar experiences, and so lost no time in incasing our feet in a manner that would insure us entrance into the theatre, even though it might detract a little from our dignity.

In the small lobby in which we found ourselves were a number of Japanese enjoying the national attitude of repose, and quietly waiting for something to turn up. The other end of the room was occupied by a counter on which was displayed a large collection of fans made of artificial cherry-blossoms, similar to those that were afterwards used in the dance. These are exhibited in a large measure116 for the benefit of the foreigner, who is expected to make generous purchases. All the while we could hear notes of that unmistakable Japanese music coming from beyond a small wooden door, mingled with weird voices and unclassifiable sounds. We began to fear that the dance had begun before our arrival, and that we might miss the best part of the show. We signified our wish to enter by pounding on the small door; but it was securely locked, and those on the other side treated our emphatic demands with oriental disdain. As we had paid our admission fee, we began to get indignant at this kind of treatment; but it is better not to get indignant at such things in Japan. Besides, the explanation was quite satisfactory, as one of the attendants told us that it was a fixed rule never to interrupt the performance by the entrance of new117 spectators, and, therefore, any one who came late must wait until all was finished. We were pacified when we learned that the dance was now nearly over and would shortly be repeated, and that we would lose nothing by waiting. But we were not the only ones who were impatient. There was one little Jap accompanied by his mother, who, after a careful search finally succeeded in discovering a small crack near the floor, to which he applied his eye in much the same fashion that his penniless occidental cousin watches the progress of a game of baseball; and evidently with the same emotions, if the glances of delight which he occasionally threw towards his mother might serve as indications.

Suddenly the music ceased, and the crowd began to push in. Japanese crowds are particularly noted for118 their good nature, and our progress into the theatre was the occasion of many sprightly jokes from the local wits, which were evidently very good, for they were received with bursts of laughter. We soon found ourselves in a front seat of a small gallery, with a three-sided stage before us. This gallery was reserved for those from over the seas and for those of the higher classes of Japan. Below in the pit sat those of humbler station, making themselves as comfortable as possible with their cushions spread out on the floor. Spectators who had already seen the performance were leaving the theatre from the two entrances under either end of the gallery, but the eager crowd from without was rapidly filling their places. The faces seemed the same that we had parted with a few minutes before, and they had the same appearance119 of expectant happiness. Here and there was a father and mother, followed by five or six wee ones, hurriedly rushing around to find the most convenient place. Apparently satisfied, they would finally sit down, begin to chatter and laugh, until suddenly one would notice what he thought a more advantageous place, when up they would all scramble again and hurry on in fear that some one might forestall them. It sometimes took more than two trials before they were satisfied, and so, while we were waiting for the curtain to rise, the gay mass below us was constantly changing about in the eagerness of the spectators to gain as comprehensive a view of the stage as possible. Each little group was provided with that indispensable adjunct to happiness,—the tobacco-box. The occasion meant far more to them than120 what took place on the stage; it was a general holiday, and they were there to get as much out of it as possible. There was a continual buzz as the conversation went on, and occasionally from some animated group there would rise a loud shout of laughter, whence we could infer that an oriental funny man had made another appreciated hit. Indeed, the sight below us was so interesting and brought us so in touch with the people themselves, that we almost forgot that there was a more pretentious display to follow, and gazed at the curtain before us in total disregard of the glories that lay beyond.

Suddenly our attention was aroused by the loud clapping together of two pieces of wood; and as suddenly every chattering tongue quietly ceased, and every laughing face assumed an expression of the utmost interest. It was the Japanese substitute for the121 prompter’s bell. The curtain obediently rose, and we settled ourselves for the enjoyment of an oriental performance. Even at the beginning we could see that the Japanese prefer to manage these things in a way of their own, for the orchestra with them is not a mere incident of the performance with which to appease the impatience of the audience between the acts or to drown the weak portions of a faltering tenor’s solo. In Japan the orchestra is kept behind the curtain as the chief performer, and comes in as generously for its share of applause. The first thing that caught our gaze, therefore, were two rows of geishas, picturesquely ranged on either side of the stage, with koto and drums ready for the opening overture. They were all painted and plastered after the usual geisha style, their little red and white faces surmounted by towering head-dresses122 of the ever-present cherry-blossom and wistaria. Dainty is a word that one constantly finds one’s self using while speaking of the geisha, and none other seems to serve the purpose so well. Those on the left, in their bright kimonos, with their little drums shaped like hour-glasses, were in the full daintiness of geisha life, while those picking the koto opposite, though still very young, could not but bring the pathetic thought that that strange life is a brief one. The whole audience observed the strictest silence all through the opening selection, which was not without its charms, even to unaccustomed ears. Occasionally a small shrill voice would be heard above the steady thrumming of the instruments, and though this could not perhaps be called singing, it had charms for those receptive souls in the pit.

123

But in the mean while our attention had been attracted to the stage. It had been prettily arranged as a garden scene, in a way far more realistic and beautiful than the painted trees and urns which pass for such in our own theatres. Here we had a profusion of cherry-blossoms to serve as a background to the equally pretty and delicate girls, who now began to enter from the two doors that had been previously used by the spectators. They were in two files, one in which pale blue and pink predominated, while the kimonos of the others were of bright red. The faces and headgear124 had been arranged in the same way as those of the musicians, and each held in her hand a cherry-blossom fan. Their entering motion was very slow, consisting of a step forward and a step backward, the time of the music being scrupulously observed. In this way they proceeded up the middle of the stage, where they parted and formed in line on the sides, meeting again in the centre. They were now ready for the dance to begin.

The word “dancing,” in its western interpretation, can hardly be applied to the graceful body-motions which satisfy the more subdued taste of the Japanese. The nearest thing that our stage can offer for comparison is the march, more spectacular than artistic, in which glistening helmets and emblazoned shields and swords play so large a part. In place of the knightly helmet these Japanese use their cherry-blossom125 head-dresses to good effect, while their less aspiring minds are satisfied with a fan instead of a sword. They have large flowing sleeves which they are constantly waving with a motion not too slow to be picturesque, and they can bend their little bodies in a way that their Western rivals have yet to learn. They toss their heads backwards and forwards in a very graceful and captivating way, and make any number of gesticulations with their sleeves, holding them in all conceivable positions in front of the face, back of the head, or stretching them out at arm’s length as a bat does its wings. At times the marching and counter-marching becomes delightfully confusing, the stage being a mass of slowly-waving colour, from the midst of which a large number of cherry-blossomed crests can be seen and an occasional smiling white-plastered126 face. The dancers do not show the slightest traces of fatigue, and when the curtain is rung, or to be more precise, clapped down at the conclusion of this first act, they seem as fresh as when it began, and a little disappointed that they are obliged to pause for a short time.

Another clap, and up went the curtain again. The scene-shifters had been working hard during the interval, and produced a charming change for the second act. We thought at first that we were to have an oriental version of a well-known scene of Italian love-making, for here was a Japanese house with bow-windows and balconies that would have delighted the eye of the most fastidious Romeo. But there were only Juliets in this play, and they made, after all, a satisfactory use of the windows and piazza, though they relied simply upon127 their own charms for their success. Now one tiny form would appear in a window, now one would step upon a balcony, and another somewhere amid the trees would smilingly gaze upon her sister above. There were no carefully memorised speeches of blank verse, but the scene was full of that clever geisha sentiment that can be so charming. Each little actor became her own poet, yet there was no need of words to make us feel the happy spirit of romance inspiring her unrestrained heart. The atmosphere of gayety was not confined to the stage but found its way into the delighted souls in the pit, and scarcely had the curtain descended when they seemed to feel it their duty to give a performance of their own. The children began to run about, pull each other by the sleeves, roll around on the floor,—all to the accompaniment128 of ceaseless tittering and all with the utmost good nature. A wrestling match formed the diversion of one group gathered around two diminutive athletes of local reputation, who were tugging savagely at each other with the utmost disregard of usual athletic rules. The pit was not without gymnasts of its own, who turned somersaults and handsprings in a way that must have shocked the more refined taste of the gliding geishas. While all this was going on, the more dignified members of the family were sitting on their heels, smoking their pipes in a stately manner, and occasionally bringing forth materials for a light lunch. This would have a greater attraction than the trials of athletic skill, and even one or two of the most successful turners of the somersault made a pause in their gyrations to watch the progress of the meal.

129

My attention was so occupied by the busy throng below, that it was not until I felt a gentle tug at my elbow that I was aware that I had a visitor at hand. I turned and saw a smiling white-plastered face, surmounted by tall sprays of cherry-blossoms, gazing up into mine. It was one of the geishas, who had left the stage and who had quickly selected a foreigner on whom to bestow her favours. And yet, I like to think her attentions were not merely of a perfunctory kind, and that she was drawn towards me for other reasons than because it was the way in which she had been trained. Her actions surely had not an artificial air, and the continued smiles which she showered upon me seemed to be sincere. She did not feel the least embarrassment, and kept talking on in her sweet little voice as though I understood130 everything that she said. And a great deal of it was perfectly plain. When, for example, she glanced up into my eyes in such a meaning way and let drop a few dulcet words, could my woman’s nature refuse to understand the little flatterer? She was amused by the ornaments on my hat, and smoothed my hair in a most caressing manner. When she tired of this, she called my attention to a small tray at my side, which I had not noticed before. From this she took a cup of tea in her delicate little hands and offered it to me. I drank it with the utmost readiness, and did not stop to131 think that it was the bitterest thing that had ever passed my lips. This was the real object of her visit, and with another smile she gathered up her tray and passed on. I gave a sigh as I saw her go through the same thing with another lady not far away, and apparently with the same sincerity and feeling. With an equal tenderness would she clasp her hands, and—crushing stroke to feminine vanity—gaze into her eyes with the same admiration as she had into mine.