“Careful how you step on that dynamite!” warned Rob.

Title: The Boy Scouts' badge of courage

Author: John Henry Goldfrap

Illustrator: A. O. Scott

Release date: July 12, 2022 [eBook #68508]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Hurst & Company, Inc

Credits: Roger Frank, Al Haines and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

“Careful how you step on that dynamite!” warned Rob.

“We’re nearly there, fellows!”

“Glad to know it, Sim. For one, I’m tired of this stuffy railroad car.”

“That isn’t all our trouble by a long shot, Andy Bowles. You must remember that two shavings of railway lunch-counter sandwiches don’t go very far toward satisfying a growing boy’s appetite.”

“I thought we would soon hear that cry for help from Tubby. His mind seems to run along the eating groove most of the time. A growing boy, eh? If he keeps on expanding much more, he’ll be as big as a hogshead, I reckon.”

“Oh! well, one consolation is you’ll all have to quit calling me Tubby, then. Say, we must be getting somewhere near that town of Wyoming,—how about it, Rob?”

There were four of them occupying seats that faced each other,—all wearing the well-known khaki suits that mark scouts pretty much the whole world over these modern days.

The very stout chap with the freckled, good-natured face was Tubby Hopkins. Sim Jeffords was of rather lean build, with a shrewd look in his keen eyes; Andy Bowles was the one whose cheeks every now and then expanded as though in imagination he might be practicing some new bugle call, for Andy had long been recognized as the official “reveille” and “taps” manipulator of the troop; and last, but far from least, was Rob Blake, the determined leader of the Eagle Patrol, who sometimes acted also as assistant master to the Hampton Troop.

These four comrades, tried and true, came from Long Island, and they had been riding for some hours on a train heading up into the interior of New York State. Part of the Eagle Patrol had passed through rather remarkable adventures in various parts of our own country and abroad as well. Those who are making their acquaintance for the first time in these pages, and who would like to know more concerning their aims and ambitions, as well as some of the stirring things that came their way, are advised to secure recent volumes of this series, where they will find tales of many lively happenings well calculated to please them.

Lately, the boys of the Eagle Patrol had been concerned in the question of national preparedness, and in their role of scouts proved considerable help to Government officials who were wrestling with a number of serious problems.

The vacation season was wearing on after their return home from New Jersey, and things around Hampton had begun to assume their habitual mid-summer stagnation when Sim Jeffords broached an idea to the patrol leader that rather fascinated Rob.

It seemed that Sim had a Cousin Ralph who lived up in the State not far from the heart of the famous Adirondack region, where his father owned a large farm of hundreds of acres a few miles from the bustling manufacturing town of—well, let us call it Wyoming, because for certain reasons it might not be wholly advisable to locate it positively.

This cousin appeared to have a “grouch,” as Sim called it, concerning the subject of Boy Scouts. He believed they were an overrated lot of boys who somehow managed to advertise themselves in the newspapers, but who, after all, could not begin to “hold a candle” to some outside fellows of practical experience.

Some of the correspondence between the cousins when shown to Rob amused him; and at the same time he could not help feeling just a little annoyed at the “jabs” which the said Ralph continued to give the movement.

More than once he had said he would like to know the Adirondack boy, because he believed he could manage to convert him and influence him to join a scout troop.

The more Rob heard about several activities on the part of Ralph Jeffords, the greater his interest grew. If the farm boy could show such surprising aptitude in Nature study and so wide a knowledge of the habits of wild animals as his interesting letters indicated, Rob felt sure he would make a most valuable addition to the ranks of the khaki-clad scouts.

Hence, when Sim came and read how his cousin had actually invited him to fetch several of his chums along up to the farm and see what a fellow who made no pretense to publicity could accomplish in several lines of outdoor work, Rob “fell” for the scheme instantly. This expedition was the result of his growing desire to meet Ralph Jeffords on his own heath and convince him that scouts were not at all overrated, as he seemed to believe.

With this short but necessary digression, we can go back again to the four boys whose lively talk will doubtless explain many other things connected with their enterprise.

“Well,” Rob Blake observed in answer to Tubby’s question, “according to this railroad folder which I got hold of before leaving New York City, we are right now at a little way-station called Jupiter, and I figure that Wyoming lies just seven miles further along the line. At the rate we are going we should be there in ten or twelve minutes.”

“It ought to be a paying trip for us, I should say,” observed Andy, thoughtfully. “First of all there’s that stump-blowing business by the use of dynamite, which I’ve always wanted to see done. Ralph says they have cleared many acres in that way; and, besides, his father, being an advanced scientific farmer, is meaning to make use of dynamite to break up the soil. They say pulverizing it many feet down has resulted in wonderful crops of grain and garden sass.”

“For my part,” added Sim, “and I think I speak for Rob, I’m interested in what my cousin has been doing with his fur farm. You know, his father fenced in a hundred acres of his wildest land, and for a year or two now Ralph has been experimenting in raising black foxes for the market. He hasn’t told me a great deal about it, but what little I know has excited me a heap.”

“Then he’s actually succeeded in raising litters of pups, has he?” asked Tubby.

“I understand he has succeeded more than fairly well,” answered Sim, proudly, for it was his own cousin of whom they were speaking, bearing the family name of Jeffords, too, which counted for a lot with a boy. “Lately he’s branched out some, and I believe he’s not only started a skunk farm in a fenced-in corner of his ‘preserves,’ but is going to try raising mink and otter, something that has really never been done before.”

“My stars! but that cousin of yours is ambitious!” gasped Tubby, though, not much given to energetic movements himself, could at least admire any one who showed a disposition that way. “The only thing I ever thought I’d like to raise in that fashion was frogs, because frogs, you know, have dandy shanks that taste just like spring chicken. I never could get enough of ’em when we camped out.”

“Oh! maybe you will up at my cousin’s place,” said Sim, indifferently, “for he used to have a pond just swarming with husky bull-frogs as big as your hat. You’ll have a jolly old time knocking ’em over and fixing ’em for all of us, Tubby.”

“I agree to handle the job, and would like nothing better,” snapped the stout boy, his face one broad grin of expectancy, as though an ambition he had cherished for many a moon was in a fair way of being realized at last; they could also see Tubby work his jaws as though his mouth fairly watered at the anticipation of the feasts in store.

A short time afterward the train was drawing close to Wyoming. Clouds of smoke told that there was considerable manufacturing done; and when finally they found themselves going into the station, Rob made up his mind that the mountain town was a pretty lively place. He wondered how it ever came that it had never had a scout troop started; and began to suspect there must be something of the feeling Ralph Jeffords had voiced impregnating the entire community.

To himself Rob was saying that it certainly looked as though these benighted people needed some sort of practical demonstration of the value to any community an efficient scout troop was always bound to be. He secretly hoped that before he and his comrades of the Eagle Patrol left that region an opportunity might arise whereby they could give these folks an object lesson calculated to bear fruit an hundred fold.

Nevertheless, little did Rob Blake suspect just then what a wonderful chance to prove their worth was destined to be offered to himself and three chums; but in good time all that will be set before the reader.

“There’s Ralph!” suddenly ejaculated Sim, as with their luggage in hand they prepared to leave the car platform, for the train had now stopped at the station.

A sturdily built young chap, whom Rob instantly liked at first sight, advanced toward them. If Ralph was a farmer’s son, he did not look very countrified; but, then, the fact of his father being well-to-do had enabled the boy to attend high school, and secure all the advantages that go with an education.

Sim grasped him by the hand, though immediately wincing under the pressure Ralph unconsciously put into his warm welcoming grip. In turn Sim introduced each of his three chums, who were also given a sample of country cordiality, Tubby rubbing his fat hand for several minutes afterwards.

“I’ve got the old one-horse shay handy here to carry you all up in, and your duffle ditto,” laughed Ralph, pointing to a rambling car that looked capable of holding half a dozen passengers, and a quantity of stuff besides. “She isn’t to be wholly relied on for stability, because she rocks like a ship in a storm; but that engine is all right, for I look after it myself.”

So Rob understood that besides his many other good qualities Ralph Jeffords must be something of a mechanic, which added to his interest in the tall country lad. He made up his mind on the spot that he was going to like Ralph; and more than ever determined he would win him around to have a much higher opinion of scouts in general, and those of the Eagle Patrol in particular, before he left Wyoming for Long Island again.

They had managed to stow away their suitcases and overcoats, as well as what fishing tackle they had thought to fetch along in hopes of having some sport while up there in the mountains, when something came to pass that for the moment made them forget all their various plans.

Tubby was just settling down in a corner of the rear seat, and trying to get his feet clear of the traps that littered the bottom, when he suddenly threw out one of his hands and pointed excitedly, as he cried shrilly:

“Oh! look, boys, look there at that horse acting crazy! One of the cinders from the engine must have fallen on his back and burned him. There, he’s broke loose and is coming this way like a house afire! Somebody get hold of the reins and stop him!”

It chanced that Ralph was the only one not already in the car, for he had stepped around to give the crank a toss, and turn over the engine for making a start.

As a rule Rob Blake was very quick in his movements, but by the time he had succeeded in getting his feet free from the various impediments not yet properly stowed away, and jumped to the ground, the lively country boy had actually sprung forward, seized the horse’s bridle, and by throwing his whole weight on the lines dragged him to a standstill.

It was splendidly done, and Rob felt that had Ralph only been a wearer of the khaki he would, because of that act, have been a candidate for a medal such as is given to scouts for saving human life.

The boy who was in the vehicle had unfortunately stood up the better to pull at the reins, as he shrieked to the runaway animal to stop; when the sudden halt came he therefore lost his footing, and took a severe header, landing on one shoulder, with his arm under him.

Rob shivered as he heard the crash, for he felt certain the poor chap would suffer some serious injury. Since Ralph seemed capable of mastering the excited horse, Rob turned toward the writhing boy on the ground.

“Give Ralph a hand, Andy!” he called out energetically, accustomed to handling sudden emergencies, and never for an instant losing his head. “You come with me, Sim. This boy has been badly hurt, I’m afraid.”

The little fellow was groaning terribly as they reached his side, and trying unsuccessfully to move himself.

“Oh! it’s broken! it’s broken! What will daddy say?” he kept moaning.

Sim saw that his face was ashen white, showing that he must be suffering great anguish. Rob immediately but gently turned him over. His right arm sagged in a suspicious manner and told the story.

“Is it as bad as that, Rob?” asked Sim, in genuine pity for the poor fellow.

Already the patrol leader was hastily examining, but it did not take him long to understand what had happened.

The patrol leader was hastily examining the little fellow’s arm.

“Yes, he’s fractured both bones in the lower arm; but in a fairly decent place between the elbow and wrist. Some one must run for a doctor in a hurry.”

“I’ll go,” said Ralph who had by now joined them, leaving Andy to fasten the still quivering horse to a hitching post; “because I know just where to find Doc Slimmons. Besides, I can get there quicker by using the car.”

He jumped over and quickly had the engine humming like mad. Meanwhile, Tubby had managed to land, and when the car shot away Ralph was the only occupant.

Luckily enough, he actually met the doctor in his own little touring car, so that he was back again before five minutes had passed. By that time quite a crowd had gathered. Sim and Andy and Tubby were employed in forcing the people to keep back, and this they did all the better because they had long been accustomed to handling excited crowds consumed either by a morbid curiosity, or by fear as in the case of a panic.

Doctor Slimmons asked a few questions. He seemed to be impressed with the fact that Rob had known just how to act.

“You say that his left shoulder was also out of place, and that you pulled the bone into the socket again, my boy? Good for you. That was the wisest thing to be done under the circumstances. I believe now that if there was no doctor within reach you would have known just how to go about handling this broken arm. You see, I happen to be acquainted with some of the doings of you scouts, because I served as scout master to a troop in Albany before coming up here to take a practice.”

“We have done such things before, Doctor,” said Rob, modestly, “and with a fair measure of success. This poor boy is suffering terribly, and I hope you get him home soon.”

“Would you like to use my car for the job, Doctor?” asked Ralph, who had listened to what was said with a question in his eyes, though he knew that was no time to ask what was in his mind.

“No, if you will assist me in getting him in my car, I can manage very well; thank you just the same, Ralph. So you stopped the runaway horse, did you; well, it was just what I would have expected from you. Let me say it would give me a great deal of satisfaction personally if khaki suits were more commonly seen on the streets of Wyoming, where there seems to be a queer feeling against the movement. There, lift gently, boys; now hold him until I can get in and fix him comfortably. I’ve given him something to keep him from fainting, and to deaden the pain as well. Before a great while I’ll have the arm set in plaster. Thank you all for your assistance,” and with that he started off, not with a rush, but in a way calculated to save his young patient as much shock as possible.

“Well, that was a sudden affair, all told,” remarked Tubby, who had been greatly exercised because of the white face of the injured boy, since he could understand what agony of mind and body the victim must be suffering. “Shall we leave the horse and vehicle here, Ralph?”

“Oh! sure,” the other replied; “the boy’s father will come and claim his property. I only hope he doesn’t blame the kid, because it really wasn’t his fault. I reckon a red-hot cinder must have fallen on his back, and stuck there. What was that I heard the Doctor say about you setting the cub’s left arm that had been dislocated—was that a fact?”

“Oh! yes, but that was a simple job,” remarked Rob, smiling at the decided interest the other seemed to show in the incident.

“We’ve got a heap more important things to our credit than that, let me tell you, Ralph,” Sim hastened to boast, when he saw the scout leader shaking his head at him, as though to beg him not to “blow his own horn,” but to leave the other find out these interesting things for himself.

“Well, suppose we try for a start again,” suggested the chauffeur; “get settled in your places, boys, while I give the crank a turn.”

“I wonder,” whispered Tubby to Rob, who chanced to sit next him, with Andy filling the back seat, and Sim in front alongside the driver, “I wonder if he begins to think scouts can be worth a pinch of salt, after all, Rob? You know that was one thing he wrote in a letter?”

“Keep quiet,” advised the other, also in a whisper, “and perhaps a chance will crop up to show him the value of scout education. I’ve got a hunch we’re due to open some people’s eyes up here. I hope it turns out that way. Even that young doctor said they were a narrow-minded lot, you remember, who had a queer antipathy against scouts and their doings.”

“Huh! given half a chance and we’ll soon show ’em,” grunted Tubby, belligerently; and when the fat boy screwed up his features into what he was pleased to term his “fighting face” he certainly did look awe-inspiring, indeed.

They were soon on their way, passing out of the town, and striking a fair road that took them into the country. Ralph, as they went along, pointed out a number of interesting features connected with the landscape, chief of which was the high peak in the distance that he called Thundertop.

“They still get bear up in that country,” he remarked, with kindling eyes that told of the sportsman spirit possessing him, “and deer are often seen. Fact is, at this season of the year they seem tame, and do heaps of damage to some of our crops. But since getting interested in my fur farm I’ve given up hunting.”

“Same way with us,” Sim hastened to say; “only now we do our hunting with a camera instead of a gun. I know fellows who used to be just savage to kill game, but who, nowadays, would ten times rather aim to snap off pictures, showing all sorts of wild animals in their native haunts.”

“I’ve heard about that stunt,” admitted Ralph, “but never met any one who had done much at it. I hope you’ve thought to fetch some pictures along with you, Sim; it would sure please me a heap to look them over.”

“I’m glad to say I have a pack with me, some of which I captured myself, while other scouts grabbed the rest. I’ll take great pleasure in exhibiting the set to you tonight, Cousin Ralph,” and the speaker gave Rob a wicked little wink as he partly turned his head, as though to call the attention of the patrol leader to the interest the other was already showing in regard to some of their activities.

Indeed, Rob was growing more deeply in earnest continually with regard to winning the good opinion of this fine fellow, who it seemed had for so long been laboring under such a misapprehension with regard to the value of scout organization.

Later on he learned that a troop had once been started in Wyoming, but, unfortunately, the fellows who tried to play the part were not qualified to serve with credit, nor could they find the right kind of a scout master who would take an interest in his charges. The consequence was that the troop went from bad to worse, and committed such depredations that in the end they had been dismissed from the service, the wise men at Headquarters declining to have the name of the organization brought into disrepute in such a scandalous fashion.

“Our place is only about eight miles out of town,” Ralph proceeded to explain, as they continued to glide along at a rapid pace, though the big roomy car certainly did “wobble” furiously, and the lurches occasionally made on bad pieces of the roadway tried Tubby’s patience severely, for his breath was knocked out of his body by the “jouncing.”

“Oh! I’m glad of that!” Tubby was heard to say. Tubby may have had the supper hour in view when he uttered those words, rather than the rough bouncing he was experiencing.

“You’ve come in time to see how we knock out some of the stumps in a piece of former woodland,” remarked the farm boy. “Dad’s doing some of his plowing with dynamite, just to get in practice for the fall, when he expects to turn over ten acres that way for an experiment patch. Yes, and I’ve got heaps and heaps to show you up at my hatchery and fur farm. I’m already glad you brought your friends along, Sim. I’ve been hoping to meet some scouts for quite a while; because, you see, I want to find out in what way they’re different from other fellows.”

“Oh! get that idea out of your head in the start, Ralph,” Rob told him, seriously! “Scouts are always boys, just the same, and with a pretty good dose of fun in them, as you’ll find. If we do have some ways that are different from the fellows you happen to know around Wyoming, I want you to find them out for yourself, because a scout should never boast of anything he’s done.”

“Every one of my chums,” chimed in Sim, proudly, “was just wild to come along with me when they heard of the stunts you were doing up here. They’re interested a heap in fur farming. I’ve heard Rob here talking about it for two years back. You’ll be able to give us lots of valuable pointers, Ralph; not that any of us consider going into the business as possible rivals.”

“Shucks! you’re welcome to, if you see fit,” declared the other, indifferently. “The chances are ten to one against success, unless you’ve got the right sort of temperament for the job, and, besides, know all about foxes, and mink, and otter, and skunks. Fortunes can be made, and fortunes lost in fur farming. It all depends on the way you go about it. So far I’ve been pretty lucky, if I do say it myself. Wait a bit until I can show you my plant, that’s all. Here we are, now, at the entrance of the Jefford Farm.”

“Skunks!” repeated Tubby, with a gasp of surprise, “do you really mean to tell me you’re raising a colony of those horrible critters around here, Ralph,” and at that he commenced to sniff the pure atmosphere most suspiciously, in a manner to make some of the others laugh uproarously.

“Wait and see later on,” was all the information Ralph Jeffords would offer, as they turned in through an open gateway, and motored up a winding drive that led to the rambling farmhouse.

The boys were immediately impressed with the air of neatness that seemed to be a leading feature at the Jeffords farm. Evidently, the farmer was not only a man of considerable means, but he also liked to surround himself with conveniences such as few dwellers in this Adirondack wilderness could afford to possess. Running water, electricity generated by his own plant, gas made at home, and a dozen other like comforts attested to his good sense.

“You see, my father had to come up here to live long ago,” explained Ralph, when he heard the others express their surprise concerning these things so unusual in a district removed from town, “and as he grew to love the place more and more, he kept installing these conveniences, until now we are fairly comfortable.”

Tubby felt sure he would like the whole outing first-rate. He even sniffed the air again vigorously, this time because of a delightful aroma of cooking that was borne from the kitchen end of the big farmhouse; for as everybody knew Tubby Hopkins was—well he himself called it a “connoisseur” when it came to the subject of providing for the wants of boyish appetites.

At the door a tall gentleman was waiting to receive them. He, of course, was the father of Ralph, a sunburned man of rugged build, who looked as though he enjoyed the best of health, thanks to his outdoor life; and yet many years before he had come up to this region expecting to make a last fight against insidious disease.

“Glad to know you all, boys,” he told them, shaking hands cordially, while his eyes glistened with pleasure, for it was not often Ralph had friends visit him, he being a rather peculiar boy and much given to keeping his own company.

Supper was soon ready, and although the boys had felt a bit tired after a day on the train, they were speedily revived once they sat down to a table that seemed fairly to groan under the weight of good things.

Tubby actually slyly pinched himself once or twice as he looked at the wonderful spread, for he feared he was dreaming. Tubby was already certain he would like the Jeffords farm very much—all but those skunks, and somehow that worried him. He had had a former experience with similar little animals that had given him great trouble, and caused him to be shunned by every boy in camp during the rest of their stay in the woods.

“Huh! once stung, twice shy,” was the way Tubby put it when he allowed his mind to travel back again to those sorrowful days of the past.

Afterwards they gathered in the big living-room, where the conversation became general. Rob had warned his chums not to attempt to boast of anything they had seen or done in their capacity as scouts; but when actually questioned they were at liberty to reply at length.

Thus a number of events came to be mentioned, and it could be seen that both Ralph and his father had their interest aroused. In good time, just as Sim anticipated, the subject of photography was brought forward.

“Oh! yes, Sim!” exclaimed Ralph, suddenly, “you promised to let me take a look at a bunch of pictures you and some of the other fellows took—I think you said they were of wild animals you had met in the woods. Would you mind getting them now, while we have time?”

“I’ll be only too glad to do it, Ralph,” came the ready reply. “While I’m about it, Rob, I might as well fetch the little package of war scenes you fellows managed to snap off over in Belgium and France when you were there; also of the Panama-Pacific Exposition at San Francisco.”

Ralph looked doubly eager on hearing this.

“Do you mean to tell me, Rob, that you’ve been across the sea, and actually in the fighting zone where the Germans and the French and British are scrapping to beat the band?” was what he flashed out.

“We had that great good fortune,” replied the leader of the Eagle Patrol, modestly; “and saw a lot of things we’ll never forget to our dying day. I’ll tell you more about them while you’re looking over our little collection. They’re not the best pictures we’ve ever taken, because you know we had only a tiny vest pocket edition of a camera, and had to snap most of them off on the sly, for we would have been arrested if caught doing it openly. I see you have a fine reading glass here on the table, and with that you can get a lot of good detail work.”

“Well, I begin to see that I’m going to get real enjoyment out of this visit you and your chums are paying me, Sim,” acknowledged Ralph, frankly.

When later on the pictures were being examined in detail, and there was always some story connected with every one, he repeated this expression a dozen times. Sim or one of the others had a lively yarn to tell of many of the animal pictures—how Mr. Coon, for instance, was induced to snap off his own likeness while in the act of stealing a tempting bait, a cord causing the trap to spring, and the flashlight to flame up, considerably astonishing the invader; also little adventures of their own while stumbling along through the darkness to set a snare for some wary old fox that would never come near the camp.

Ralph enjoyed these reminiscences hugely. They were quite in line with his own fads, and more than once he exchanged glances with his father as though to admit that possibly more enjoyment could be had in hunting with a camera than while “toting” a murderous shotgun through the woods in order to kill off the innocent little beasts and birds that dwelt there.

Then, when the war pictures were being shown, how eagerly did he ask dozens of questions, for every boy has it in him to yearn to see military manœuvres, perhaps a battle royal; though after passing through one such experience his ideas are apt to change radically.

Rob was able to give quite graphic descriptions of numerous thrilling things he and his chums had witnessed, yes, and even participated in. He told these modestly enough, as though it was only a matter of course that scouts should lend a helping hand, and to assist field hospital surgeons take care of desperately wounded men of both sides who were being brought in by streams.

At another time Ralph might have felt considerable doubt regarding the authenticity of these accounts. Somehow, after witnessing the prompt manner in which Rob had taken care of that unlucky boy thrown from the vehicle, and suffering not only a broken arm but a dislocated shoulder as well, it seemed only natural that a wideawake young chap, such as he realized the scout leader to be, should prove equal to even greater emergencies.

Long and earnestly did he scan those small pictures that in many ways revealed the fact that Rob had indeed been in the war zone, close to where terrible battles were being daily fought to prove whether the ideals of the Teuton or those of the Allies were to prevail from that time forth in the world.

Finally, Rob grew tired of talking. He turned the tables by starting Ralph into telling some things connected with his unique enterprise of fur farming. Once this subject came to the front and the farm boy was all animation, for it could be easily seen that his heart was in his peculiar profession.

“I’d always had ideas on the subject,” he went on to say, “but only a couple of years ago commenced to put them into practical operation. Dad gave me a hundred of his wildest acres that could never be used for anything else, and we had the tract fenced in, even going down several feet so as to keep my foxes from ever digging a burrow, and escaping in that way.”

“Did you catch or buy your first pair of blacks?” asked Rob.

“Well, as there hasn’t been a wild black fox seen around this neighborhood for twenty years and more, though plenty of common red ones,” Ralph explained, “we had to invest some big money for the first pair. But they had a litter of pups, and it happened that the little chaps came true to color, all right, though they sometimes revert back to the old stock, you know. So we got started, and by trading, selling, and buying I now have just sixteen foxes in my pen, some young, and others ready to donate their pelts this Fall, if the market quotations hold up.”

“About what price do you call a good one?” asked Sim.

“Oh! all the way from five hundred up to fifteen hundred dollars,” said Ralph in the most unconcerned way possible; at which Tubby’s eyes widened, and he exclaimed:

“Gingersnaps and popguns! but you surely don’t mean that amount of money for just one little black fox skin, Ralph?”

“Why, certainly,” the other assured him, smiling at Tubby’s amazement. “There have been extra fine ones that brought as much as three thousand dollars. I never expect to raise such expensive stock. I’m counting on five hundred as the basis of my calculations; and if you’re fairly successful in raising your litters, there’s good money in the business at that. Besides, it’s great sport in the bargain to one who really loves animals, and knows more or less of their cute ways.”

“Five hundred dollars for just one little skin!” Tubby was heard to mutter, as though that struck him as most remarkable. “Well, if you keep along as you’re going, Ralph, I can see you getting to be a second Rockefeller before you’re fifty. Now, I don’t suppose a skunk is quite as valuable an article, though the fellow brave enough to handle him deserves a fortune, according to my notion.”

“Oh!” laughed the other, “we’re glad to get from one to three dollars for a skunk pelt, according to whether it’s jet black, or striped. Most of them are striped, you know. But wait and you’ll learn more about these things later on.”

“Then it’ll have to be at considerable distance for me, I guess,” affirmed Tubby, with a look of resolution on his broad face, and a determined shake of his head.

Upon being encouraged to narrate some of his interesting experiences while engaged in his odd calling, Ralph gladly complied. The scouts showed deep curiosity as they plied him with questions. Evidently there was a good chance for a fair exchange of notes, and it looked as though both sides would be all the richer for this barter.

It was found that an extra large room had been set aside for the boys, with two generous double beds in it. There were four windows, so they were sure to have an abundance of fresh air while up at the farm.

When retiring for the night, at about ten o’clock, amidst sundry yawns, and more or less stretching of arms, the quartette from Hampton seemed to agree on one particular thing. This was to the effect that their stay in the mountains promised to be one of the most interesting and entertaining of all their experiences. There were so many new things for them to see, and the environments seemed so particularly home-like-with royal fare thrown in, Tubby wanted them to remember as they gave thanks—that a feast awaited them.

Some of them wished they had come for a month instead of just one week. But the vacation season was nearing an end, and they had certain duties and engagements around Hampton that could not be longer deferred.

So they finally climbed aboard their several big beds, and Tubby tried to get the wonderful things he had been hearing out of his mind, so he could go to sleep.

A grand morning awaited the four boys as they hurriedly dressed, and then stepped outdoors. Ralph was already afoot, as he had a few chores to be attended to at the nearby barns, where the grunting of fat hogs and squealing of smaller pigs, the lowing of fancy cattle that gave the rich cream they had enjoyed the night before at supper, as well as horses, sheep, and even some high-priced goats told how Mr. Jeffords took his country pleasures.

Then there was a series of houses and yards devoted to poultry, mostly of the Rhode Island Red and White Leghorn varieties. Just beyond the boys were delighted to find a pen of beautiful imported pheasants with magnificent plumage of almost every color of the rainbow.

“But try as we would,” confessed Ralph, “we’ve never been very successful in raising many of those birds. Father thinks they are not suited to the climate, even up here in the mountains, where it never gets as hot as down your way. You see, they flourish best in a country like England, where the winters are mild, and summers fairly decent. So we just keep that stock for show purposes. Father lost money in his investment; but it taught us both a lesson. We go in now for the best native stock of all sorts.”

Breakfast even raised the good opinion Tubby already entertained toward the woman who did the cooking. When he found that she was a genuine Southern “mammy,” for the Jeffords originally used to be slave-owners down in South Carolina, he could understand how she made such jolly cornbread, and why they had hominy on the table every morning of their stay.

Now they had the first day before them, and there would be much to interest them.

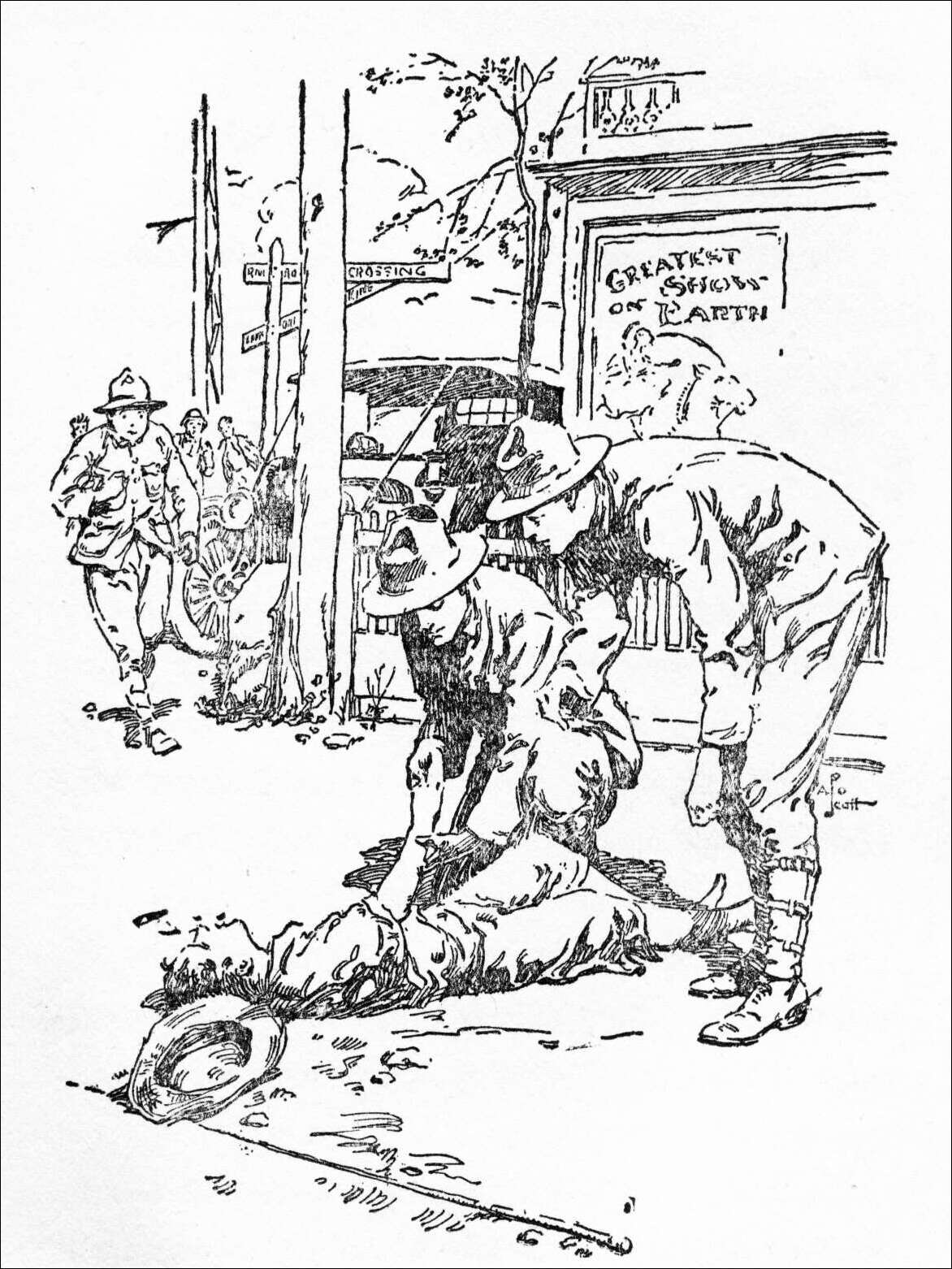

“First thing you want to watch,” Ralph went on to say as they still sat around the table, though no one could eat another mouthful of food, “is the way we smash our big stumps up here. It’s always well worth seeing to a novice, though long ago we became so accustomed of harnessing dynamite, and making it do our work for us, that we take things as a matter of course.”

“I suppose,” said Andy Bowles, reflectively, “it’s just like folks who have electricity, and use it for cooking, ironing, making toast, heating water in a hurry, and a thousand-and-one other things; so before long they look on it as a servant in the house, always to be started working by the touch of a button.”

Once outside and the boys were led to a distant part of the farm, where the wood lot still remained. Here several men were busily engaged in blasting out stumps of trees that had previously been cut down, and carted away in one shape or other.

The dynamite cartridge was placed properly, being connected by a wire with a battery at some little distance away. Then at a signal the operator made his connection, there would follow a sharp report quite different from a powder explosion or the roar of big guns over on the battle lines in Europe. After that the stump would be lifted bodily from its lodgings and could be carted away, either whole or, as usually happened, in fragments.

Rob was particularly interested in the operation. He examined everything connected with the simple apparatus, and asked a number of questions concerning the outfit. No one dreamed how valuable the information he thus received was going to prove before a great time had elapsed.

“Of course, if you are doing all these stunts with dynamite, Ralph,” he finally remarked, “you must keep quite a stock of the explosive on hand all the time?”

“We have to,” he was told, without hesitation. “It is kept locked up in that little stone house we passed coming up here, and father himself doles out the day’s supply. The stuff is a little too dangerous, and costly, too, to be left around loose.”

“I should say so,” admitted Tubby, who had listened to all this talk with interest, though never for a minute dreaming that it would enter into any affair in which they would be connected.

“You see,” continued Ralph, always willing to supply information, “we have it so arranged that we can carry several cartridges, as well as the coil of wire and the battery, on this little hand-cart that one man can push. So we can go to any part of the farm. Once we drove twenty miles with the outfit to clear up a tract for a gentleman who had never seen stumps blown to pieces in this way.”

Rob thought that was a clever idea. He impressed it upon his mind, though had he been asked why he did this he might have found it difficult to answer, except to say that he always liked to store such interesting facts away for future reference.

“How about that plowing with dynamite?” asked Sim. “Will Uncle Simon be doing any of that today, do you expect, Ralph?”

“I hardly think so,” the other replied. “It was laid out for tomorrow, and one gang working along those lines is enough at a time. The next thing on the morning’s programme is a visit to my fur farm. Are you feeling fit for a little walk?”

“We’re crazy to be on the jump,” affirmed Sim. “You must know that scouts hike a great deal, which is one thing that makes for their good health. Even Tubby here is pretty good at tramping, though you wouldn’t think it to look at his build. He has plenty of grit, and will stick everlastingly to anything he attempts, even if laboring under a handicap that none of the rest of us have to stand.”

Tubby had to bow to Sim after this compliment.

“Oh! I’ve got plenty of grit,” he admitted, “but there are times when I puff and blow terribly. That can’t be helped, you know. I’m built on such a generous order that I have to carry a heap more weight than most fellows.”

Presently they started forth, chattering like magpies as they walked along. The section of the big farm given over to Ralph’s experiment in fur raising was quite some distance from the house, being an angle where the primeval woods covered most of the “soil,” which, by the way, happened to be pretty much rock.

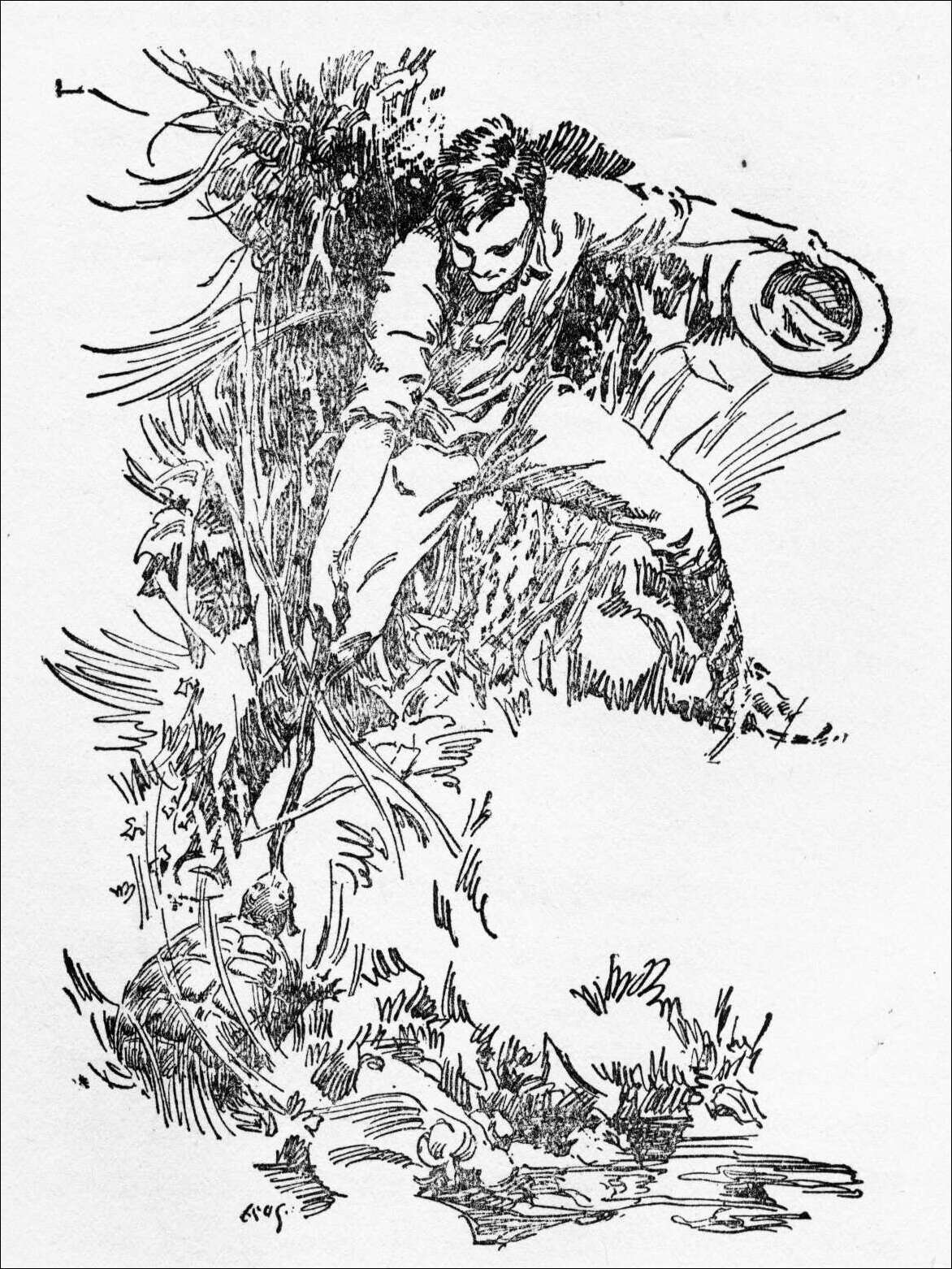

On the road they came across a pond where there were rushes, and plenty of frog-spawn floating on the water. Tubby became interested at once.

“Oh! listen to the bass chorus, will you?” he ejaculated. “Why, there must be a dozen huskies keeping time if there’s one. Oh! see that monster on the bank! Say, I can count three more big greenbacks sunning themselves on the mud near the edge of the water. Whew! but it makes my mouth water just to think of the delicious messes a fellow can pick up here any old day.”

Ralph laughed good-naturedly.

“Then consider yourself appointed official frog hunter for the crowd,” he told Tubby, whose eyes glistened at hearing the joyous news. “You can have just as many as you want to eat while up here. Somehow, I don’t seem to care much for frogs’ legs myself, nor does dad. When we hanker after chicken we get chicken, and if it’s fish we want, we go out for trout or bass; but the combination doesn’t appeal to us.”

“Thank you a dozen times, Ralph, for giving me the promise of a smashing good feast. I’m abnormally fond of them. When you ship a batch of frogs’ legs down to New York markets, how do you go after them? They jump so swift that it’s always hard for me to corral any. At home I use a short pole with two feet of line, and a red fly at the end, pushing close enough to dangle the said fly before the nose of Mr. Frog, who grabs it in a hurry.”

“Oh! we don’t bother with all that fuss up here,” explained Ralph. “I have a little Flobert rifle that I knock ’em over with. You could get a hundred in a morning without much trouble. I’ll lend it to you any time you want, Tubby.”

That completed the delight of the fat boy, who, in imagination, already saw himself feasting on his favorite dish to his heart’s content.

“It’s going to be lots of fun for Tubby,” remarked Andy, quizzically, “but all the same it’s bound to be death to the frogs.”

“Well, what good are the slippery things, except to serve as food for people, I’d like to know? As singers they’re a miserable failure, and all their lives, from the time they’re tadpoles up to when they weigh two solid pounds, they never do any particular good till they are served on the table, browned to a crisp, and making honest boys’ hearts send up their thanksgiving.”

“No use trying to convince Tubby about the sin of sacrificing things to satisfy his appetite,” laughed Rob. “He’s committed to the idea that everything was put on this earth for one great purpose, which was to cater to the wants of man.”

“Well, isn’t getting good and hungry one of man’s greatest troubles?” Tubby immediately demanded, triumphantly. “Hasn’t he been given dominion over all the fowls of the air, the fishes of the waters, and the animals that populate the woods in order to sustain his life? That’s my way of looking at it, so there you are.”

As usual, Tubby’s argument was unanswerable, and as they left the noisy frog pond in the rear, the fat boy cast a happy glance back at the watery stretch, as though anticipating royal good times around that vicinity later on.

After a while they came to a wilder stretch of country. Rob knew then that the fur farm was close at hand, and presently they caught glimpses of the high fence surrounding the tract given over to this unique enterprise.

“I wanted to ask if you ever had any of your foxes stolen, Ralph?” Sim was inquiring as they pushed on. “When a single black fox pelt is worth hundreds of dollars, it strikes me that some unscrupulous men might scheme to sneak in on you and try to clean out your farm.”

“Well, they couldn’t do that, because the foxes are mighty cunning,” the proprietor explained. “They would have to set traps, and come and go. I’ve figured all that out, and taken proper precautions against losing any of my prizes. One of the men stays up here day and night, and I often join him. He has a cabin inside the enclosure; and, besides, we have a way of detecting it if any intruder should try to climb the fence. Electricity is a great agent, you know, Sim.”

He did not take the trouble to explain further, so the boys could only guess what he meant. Rob believed that there must be a wire running along the top of the fence, and that every night an electric current was turned on, after the manner in which empty dwelling houses are protected in big cities by a firm that guarantees against their being entered and robbed during the absence of the owners.

If this were so, it would mean that Ralph was clever, and up-to-date. Rob found himself admiring the other more than ever. He also meant to win Ralph over to a new way of looking at scout activities before they departed from that region. Such a wideawake and enterprising boy certainly should be enrolled in the ranks where his influence would be for the upbuilding of other fellows’ character.

In other words, Rob believed that Wyoming was horribly behind the times in not encouraging a regular scout troop; and he hoped that this fault could be remedied before a great while, to the betterment of the community and every growing lad around Wyoming. Because an irresponsible group of fellows had once organized and tried to carry out the ideas of the Boy Scouts without any real authorization from Headquarters was no reason the experiment should not be tried again, this time starting from the right base.

Once inside the enclosure, they found many things to interest them. Tubby expressed himself wild to set eyes on a genuine black fox. He had often seen the common red variety, but something that was especially valuable appealed to his curiosity.

So, to oblige him, Ralph uttered a little call that, after being repeated several times, brought a response. They could see a dark-colored object creeping toward them, but it would not come very close.

“Usually Timmy will come up and eat food out of my hand,” said Ralph; “but, like all his breed, he’s a timid little duck, and doesn’t take to strangers. So that’s about all you’ll see of him today.”

At the first movement one of them made the fox vanished like a streak.

“He’s lit out,” said Tubby, in a disappointed tone. “I’m sorry, too, because I’d like to say I’d petted a black fox. But, Ralph, between us, he looked sort of silver-colored, you know?”

“Some people call them silver foxes,” the grower of fine fur explained. “In some lights they do look silver gray, and then again dense black. But their fur is the silkiest known, which is one reason it commands such a big price; it isn’t coarse like that of other foxes. You know the difference between a common cart animal and a thoroughbred Kentucky race horse; well, and black fox is of that racer breed.”

They naturally talked more or less of the chances of such an enterprise succeeding, and Ralph learned that Rob Blake was pretty well posted about all such things.

“We are taking a chance, you understand,” he remarked, after Rob had asked several questions, “but we think we are on the way to making the venture a profitable one. Like everything else that deserves success, you have to work like a beaver, and put your whole soul into it, day and night. It’s eternal vigilance in raising fur, because we have all sorts of enemies to fight against.”

“Enemies?” repeated Tubby. “What do you mean by that, Ralph?”

“Oh! some disease may get into your pen, just as sometimes happens to chicken fanciers, and cleans them out. Foxes are liable to disease, and also to insect pests that make the fur less valuable. Then eagles and hawks are always ready to pick up a fat young fox if they get a chance, not to speak of raiding wildcats. My man always carried a gun with him when making his rounds.”

“And has he often had to use it to protect your fox litters?” asked Tubby.

“We’ve killed quite a few birds that meant to rob me of the profits of my labor,” Ralph answered, “and one wildcat was shot close to this place; but so far as I know up to now I haven’t lost a single pelt. We count our animals every day at feeding time. I’ll fix it later on so you can see the whole pen at once by staying hidden in a tree while we call them around. Now let’s move along, because you will want to see my other pens containing the mink, otter, and skunks.”

“You’ll excuse me, boys,” observed Tubby, naively, “if I stop to tie my shoe lace. I’ll catch up with you right away, or hang on to your wake, which will answer just as well.”

Sim chuckled as though amused.

“Bless his heart,” he remarked to Ralph, who had not exactly understood, “Tubby has a natural prejudice against skunks. It was honestly earned, too.”

Then he rapidly went on to sketch the adventure that had taken place once upon a time when Tubby was green to the woods, telling how the other upon running across a skunk for the first time thought it a “cute” little animal just such as he wanted for a camp pet; and after trying to get it in a corner so as to pounce on it, Tubby wished he hadn’t—also how he was banished from active participation in the delightful times they had later on simply because the other fellows refused to associate with him.

All this amused Ralph greatly.

“Well, I admit that it’s mighty dangerous for any one to bother with skunks, for they are timid animals, and mistrust every one they don’t know,” he stated. “I move around among them without any trouble. They feed from my hand, and I’ve taken up several of them just as you would a tabby at home. I admit that eternal vigilance is the price of safety when near them. You must be on the alert continually, and never do anything to startle them.”

“Well, a bee man near our town told me bees were handled along the same lines,” Andy Bowles added. “Those who handle the frames full of honeycomb, and swarming with bees must be cool chaps. Smoking helps some, for bees seem to think the hive is in danger, and begin to load up with honey right away. It seems that when a bee is carrying all the honey it can stagger under it isn’t liable to get busy with its sting.”

They now arrived at the part of the big enclosure given over to the striped animals with the bushy tails and the small heads. Tubby stayed far back, and kept on the anxious seat all the time. No inducement could tempt him to join the others.

“I’m not immune, if you fellows are,” he called out, when they tried to coax him along. “I know when I’m well enough off, too, and some people don’t seem to understand that fine point. Don’t bother with me, boys; go ahead and investigate; but I hope you’ll be wise enough to let Ralph do all the handling of his pets. Ugh!”

So they left Tubby there to await their return. Ralph showed them through the skunk preserve, explaining many things connected with the curing of skins so that they would have a marketable value.

“You see, there’s getting to be a shorter crop of the best skins every year to meet a growing demand,” he proceeded, after the manner of one who had the points at his fingers’ ends from constant study. “That means commoner pelts have to take the place of those that are falling off. Many of these are muskrat and skunk skins, and even the common house tabby is called on to help tide over the shortage. What with a skillful use of dyes, and even the sewing of white hairs in black skins, they manage to deceive the public.”

He showed them how he could feed some of his queer pets. Tubby at a distance was holding his hands together, and looking very much distressed when he saw a dozen of the striped animals all around Ralph, and acting like chickens on the farm when grain was being thrown to them.

Later on, when the boys were thinking of turning away and continuing their investigations further, they heard a great outcry from near at hand.

“Hey! Ralph, everybody come quick, and chase this skunk away! He’s bent on making up to me, and I can see from the way he looks that he just knows I’m a hater of his species. Oh! please hurry and save me!”

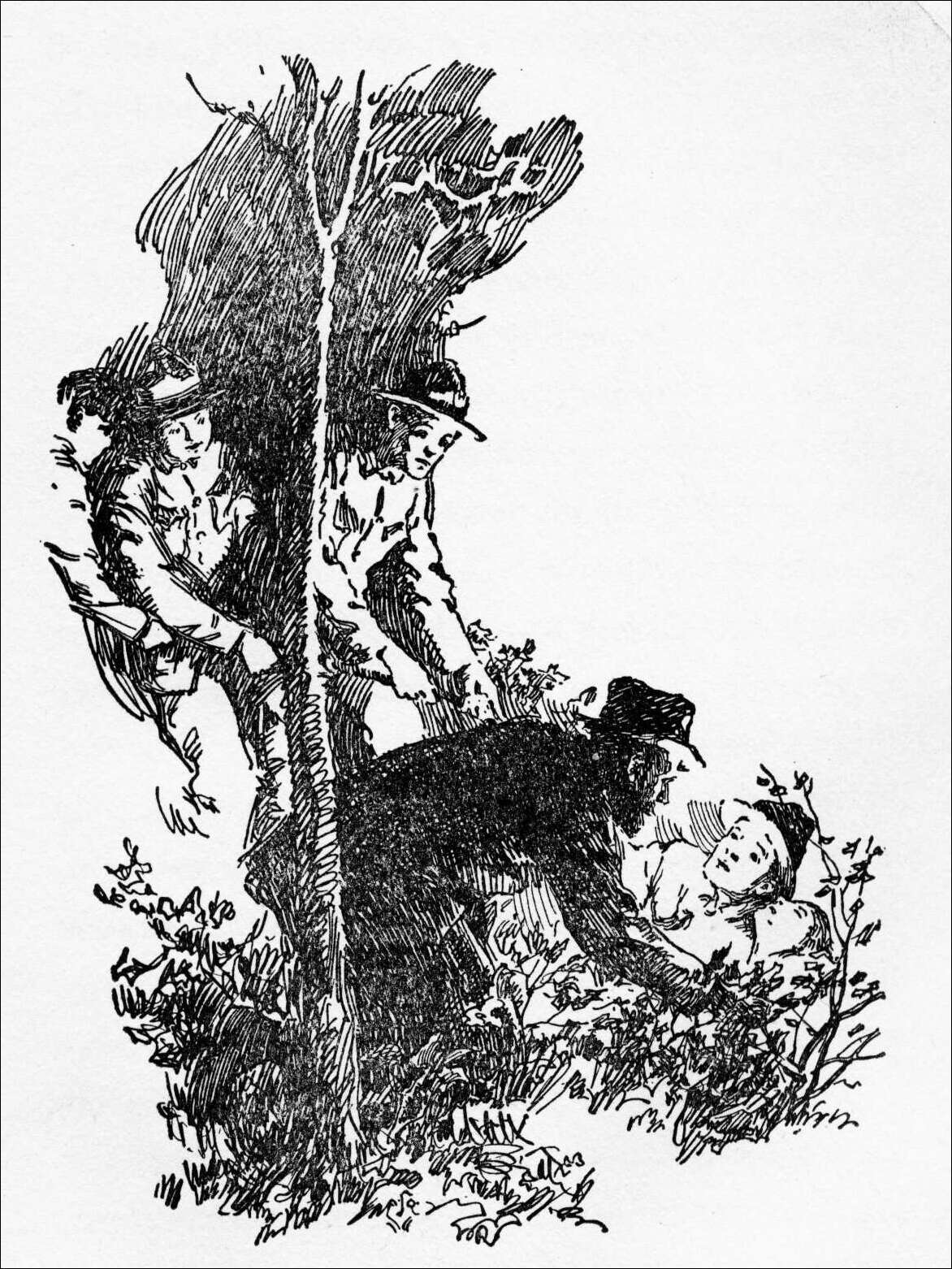

Laughing at the frantic appeal in Tubby’s voice, they hastened toward him, to find that the fat boy in desperation had actually climbed a tree, while a very small specimen of the inmates of the corral was moving about below, now and then looking upward, as if wondering why he was not given something to eat, as usual.

They rescued Tubby by Ralph coaxing the “terrible beast” to move away. Tubby looked red in the face, and also seemed to be a little ashamed at having shown the white feather.

“Well, I admit it was a bad case of rattles with me,” he said, with a grimace; “but, then, there’s a reason. I’ve been there before, and I know that the smaller they are the more likely you may be to get them angry. But all’s well that ends well. I’m glad you’re done with this particular pen. Now show us your mink and otter, won’t you, Ralph?”

“I can show you where I keep them, and what I’ve done to induce them to feel at home and multiply,” replied the other, “but I doubt whether we catch sight of a single member of the community. They are that shy they seldom come out in the daytime. As to feeding them, all we have to do is to see that there are plenty of fish in the brook that runs through the lot.”

“But if that brook comes and goes, what’s to prevent your high-priced mink and otter from following it out?” inquired Andy, who never liked to puzzle over anything unnecessarily when the answer could be obtained simply by asking.

“Oh! we’ve fixed that by a regular barred gate at either end,” explained Ralph. “The water can escape, ditto very small fish; but we keep larger ones stocked in the stream; and those fur-coated fishers can always get a mess.”

“And I suppose,” suggested Rob, deeply interested, “that if you ever do think they’ve increased in number, and you feel like taking your toll of the bunch, you’ll have to set regular mink and otter traps in the water to catch them with?”

“That’s what it’ll amount to,” admitted the other, “but understand that I’m not building any great hopes of more than getting my money back on this mink and otter venture. I don’t believe any one has, so far, been very successful raising them artificially. Some animals, you know, will not breed in captivity. But I’m making the experiment, and later on will let you know how it turns out.”

“Show us how that water gate works, will you, Ralph?” suggested his cousin, who always liked to examine anything that excited his interest—Tubby had also been that way once, but since a bitter experience he had shown more commendable caution, and was ready to take some things for granted.

“Certainly, if you come this way with me,” the fur farmer replied. “Here’s the creek, you see, and in some of these little burrows among the rocks and in the earth the mink and otter lie in safety. Right now I warrant you more than one pair of bright eyes watches every move we make, though you couldn’t discover the animal if you had a field-glass along.”

In this fashion he continued to tell them many interesting things connected with his study of wild animal life; some of which were new even to Rob, who had had an extended acquaintance with such subjects ranging over a long experience. The subject was very fascinating to all of the scouts, even Tubby declaring that he was beginning to take quite some stock in the study of small game animals, “all but one kind that somehow don’t seem to appeal to me,” he went on to say, whereupon, of course, Sim had to hastily remark:

“Huh! some of the boys are still of the opinion that they do appeal to you pretty strongly, Tubby; but there, let it pass. I just couldn’t help saying it, you know.”

They saw the tracks of the timid mink and otter along the edge of the stream where they fished for their dinners daily, but did not catch even a fleeting view of a member of the little fur colony.

Coming to the high fence among the trees, they found where the brook passed out. The “gate” mentioned by Ralph was a well-built one, made of stout lumber, and with iron bars close together, between which the water could always pass, but no animal find either an exit or entrance.

“Sometimes, after a storm, we have to clear this grating,” Ralph told them, “for it catches and holds all sorts of floating stuff, such as dead wood and the like. So far it seems to answer our purpose. Our last census of the inmates showed that they were all here, and that there was a pair of whelps with one set of the mink—if that is what you call them, perhaps cubs, eh, Rob?”

“Well, I hardly know how to answer that,” confessed the other. “If I wanted to speak of them, I’d likely say baby mink, or youngsters. It would be a feather in your cap, Ralph, if you did succeed where so many others have fallen down. I’m sure we all wish you the best luck going.”

“That’s right!” declared Tubby, emphatically. “I admire pluck wherever I see it; and somebody has always got to be a pioneer in every movement that succeeds over many failures.”

“You see, the woods are pretty dense over in this section,” explained the fur farmer, “and there’s always danger that some wild beast may slip in here when Pete and myself are away, to make a haul of my property. It would be a hard blow if I came along here some day and found that my mink colony had been cleaned out.”

As though his words had been carried to hostile ears and aroused a storm of protest, at that very moment there came a growl so savage that it made Tubby tremble. He stared straight up into the tree from which the sound seemed to proceed, pointed a quivering finger, and gasped the one word:

“Wildcat!”

“Don’t move!”

Tubby knew that when Rob Blake spoke in that tense way he meant what he said; so, although he felt an inclination to shrink back from that terrible vision of an enraged bobcat, he managed to grit his teeth together and hold his ground.

Ralph, Sim and Andy took the admonition to heart as well as did the fat boy, for they seemed rooted to their tracks, all staring as hard as they could up into the lower branches of the tree just in front.

The cat could be plainly seen crouching there, with its ears flattened against its head, after the manner of all enraged felines. It was a pretty “hefty” specimen of its kind, too, Rob saw, much larger and more powerful than the ordinary cat.

Undoubtedly, it “sensed” a feast beyond the boundary fence, and had started to pay a neighborly visit with dinner in mind when interrupted by the approach of the five boys. Being accustomed to lording it over other animals in its native forests, the wildcat did not fancy beating a retreat simply because some of those two-legged creatures chose to cross its path.

That ominous growl was meant as a warning to them to beware how they incurred its animosity. From the way in which its haunches had settled upon the limb, it appeared as though the beast might be in readiness to make a leap; and it was because of this that Rob had instantly hissed those words.

At the time it chanced he was just a little in the advance; hence his position was more inclined to be a perilous one than could be said of his companions. None of them had any weapon handy with which to defend themselves in case the animal really attacked them; though Sim and Andy immediately began to use their eyes to advantage in the hope of being able to see a club of some sort, always the first resort of a boy in trouble.

“Tell us what to do, Rob!” urged Sim, who had actually discovered the cudgel he wanted to possess, yet did not dare make a move toward getting it in his grip lest by so doing he tempt the savage beast to spring.

“Stand perfectly still!” ordered the patrol leader. “You can do more good that way than by moving. If we all just stare at him, he’ll soon get uneasy, not knowing what to make of such a mysterious crowd. Animals hate to look into human eyes, they say. I’ve stared a dog out of countenance that way myself.”

“Huh!” grunted Tubby, remembering how he had once tried that same game himself with a barking puppy, getting down on his hands and knees to manage better, only to have the little varmint instantly seize hold of his nose and hang on.

“How would it do for all to give a big yell together?” suggested Ralph.

“That might make him jump, I take it,” replied Andy Bowles, wishing he had his bugle handy, for with it he could sound a shrill blast that would surely cause the impudent cat to retreat in haste.

“Yes, it would startle him, all right,” admitted Rob, “but he might jump the wrong way, and at us. Better try my scheme; it can do no harm, and I don’t think he’ll attack us unless we begin the fight.”

“I see a bully club close by my feet, Rob.”

“Well, don’t bother trying to get hold of it just yet,” urged the other. “But if he should leap at me, see to it you grab that club in a big hurry, and let him have it with a smack. Steady, now, you can see the beast’s beginning to get uneasy right along.”

“Yes, you’re right, he is, Rob,” admitted Ralph, with a vein of relief in his voice, for no fellow can entertain the idea of battling bare-handed with a fierce four-footed adversary without shivering; and Ralph knew only too well how even a scratch from the claws of a carnivorous animal may cause blood poisoning if not properly treated in time.

So they all continued to stand there as nearly like statues as their various dispositions would allow, keeping up a battery of staring looks that must have more or less bewildered the intruder.

Tubby heaved a great sigh. It was additionally hard on him, this trying to keep absolutely still, lest by moving an attack be precipitated, the end of which none of them could see.

“Gee whiz! isn’t he ever going to skip out?” he groaned, feeling the drops of perspiration gathering on his forehead, and running down his stubby nose, yet being deprived of the satisfaction of taking out his red bandanna and wiping his streaming face as he would have liked.

“Have a little more patience, Tubby,” pleaded Sim. “He’s getting ready to vamoose the ranch, I tell you. There, didn’t you see how he took a quick peek behind him? They say that in a fight the man who looks back is the one who is getting whipped, because he’s thinking of beating it. Watch, now, and be ready to give him a parting whoop if he does jump over the fence again.”

The strange bobcat somehow found it unpleasant to remain there on private grounds, and with those five queer creatures facing him so mutely. They meant him harm, of that he must have concluded, and perhaps he had better postpone his intended feast on plump fox cubs or young mink. Night would be a better time for his hunting; and a retreat could not be called dishonorable when the enemy counted five against one.

So, finally, he made a quick backward jump that allowed of a new perch just over the dividing fence. This movement was the signal for a sudden change of policy on the part of the boys, for they burst into a series of loud shouts, and Sim instantly darted forward to secure the coveted club.

The wildcat, having concluded to pull out and evidently not liking those aggressive sounds, continued its flight, growling savagely as it went, and looking back once before finally disappearing amidst the foliage of the trees beyond the high fence.

“That was an adventure, sure enough!” exclaimed Sim, breathing hard after his recent exertions. “Just to think of our running across such a tough customer when Ralph here was speaking about troublesome pests. Do you reckon this was his first visit to your pens, Ralph?”

“I hope and believe so,” the other replied, frowning at the same time. “I would hate to learn that it had become a habit with him. Besides, we have seen no signs around to indicate that he’d ever been here before. But the rascal has scented my pets, and will give us no peace until he’s done for.”

“I should say the same thing!” declared Rob. “It’s just like a wolf that threatens a sheep-fold, there can be no safety until he’s been potted.”

“I’ll see Pete at once,” continued the other, with a look of determination on his strong face, “and start him out with the dogs. If they’re lucky they’ll get on the track of the beast before sundown and, I hope, knock him over.”

The conversation then was mostly of the woods, and Ralph as well as some of the others mentioned a number of curious circumstances that had come under their observation while camping out. Ralph had formerly been quite a hunter and trapper whenever he had an opportunity, though, as he confessed, latterly the sport seemed to be palling upon him somewhat.

“To tell the truth, Sim,” he said, as they strolled back toward the distant farmhouse, after seeing Pete and starting him off with the dogs to look for traces of the feline thief, “I’m getting to be interested in that scheme of hunting with a camera, and I think I’ll take it up soon. There are plenty of good chances for doing something of that sort around here, you know. I want you to put me wise to all the wrinkles of the game before you say goodbye, which I hope won’t be for quite some time yet.”

“What are we going to do this afternoon, boys?” asked Andy.

“Well, if that question is aimed at me,” ventured Tubby, quickly, “I know what I’d like to do, that is if Ralph happens to have plenty of ammunition for that bully little Flobert rifle of his. Frogs for mine, thank you. One thing I like about this scheme of shooting the jumpers is it doesn’t seem half as cruel as catching them with a hook, even if you do intend to put them out of their misery soon afterwards.”

Tubby was known to have a tender heart, and would not hurt anything if he could possibly help it.

Ralph proposed that if the others felt inclined, they might make a run out to a certain lake he knew, where they would likely have a pleasant time.

“Whether we get any bass or not we’ll certainly enjoy the run with you, Ralph,” Rob told him. “As we’ve gone to the trouble to fetch some rods and fishing tackle along, it would be a pity not to wet the lines just once. So far as I’m concerned, I only too gladly say ‘yes’ to your proposition.”

Sim and Andy immediately voiced their sentiments in the same way, and so it was settled. Tubby would be fixed out with the small Flobert rifle and a supply of ammunition, also rubber boots, for he might have to do some wading in order to retrieve his game after shooting it. He promised to have a mess of frogs’ legs ready for the evening meal when the boys came back.

“See to it that you fellows do your duty with the gamey bass!” he called out as the other four piled into the big car, ready to start forth.

“I heard you call that young chap, who was filling the gas tank, Peleg; is he one of the workmen on the farm, Ralph?” Rob asked after they had gotten fairly started, for he chanced to be sitting alongside the driver at the time, the other boys occupying the rear seat.

He saw that Ralph had a slight frown on his face, as though something unpleasant had come into his mind just then, possibly induced by mention of the name.

“Yes, his name is Peleg Pinder,” he replied in jerky sentences. “His father was a sort of hard case in Wyoming, and the family seemed to be always in a peck of trouble. Some folks said the children’d all be worthless, just like their good-for-nothing dad. Then there was a fire, and Peleg’s father was burned trying to save an old crippled woman. Somehow people thought better of him after he died. The children scattered. One girl is working for a farmer seven miles away. My father took Peleg in, and gave him a home. Been with us six months or so now.”

“How about his work—he seems lively enough, and good-natured. In fact,” continued Rob, “I rather like the sparkle in his eyes.”

“Yes, he fooled me right along, too,” said Ralph, with a trace of a sneer in his tone. “He does his work so you couldn’t really find any fault; but then it’s hard to shake off a bad name, and the Pinders always were shiftless and deceitful, Wyoming folks believe.”

Rob was interested at once, and for a reason. He hated to see any one “picked on” simply because “people” chose to believe no good could come out of a family that had a shirker for a father. Why, the very fact that poor Pinder had died while performing an act of heroism ought to be enough to prove that such a wholesale condemnation was utterly wrong.

“You’ve got some sort of reason for saying that, I imagine, Ralph?” he continued, bent on discovering the truth now that he was at it.

“Well, I have, though I didn’t mean to mention it to any of you, because for one thing I wanted you to have a jolly time of it here, and without bothering about any of my troubles. Then, again, I hate to speak ill of anybody, even Peleg Pinder.”

“What has he been doing, then, to make you suspect him?” demanded Rob.

After hesitating for a brief interval, as though he hardly knew just how much to say, Ralph went on to explain.

“Hang it all,” he commenced, “I hate to say a word about it, because it makes me feel mean, just as if I might be picking on a poor chap who hadn’t any other friends but my folks, and who’s got a heavy enough load as it is. Believe me, I haven’t so much as breathed a word of this to dad. He’d fire Peleg if he knew, and then I might be sorry. But I’m honestly up a stump trying to decide what I ought to do.”

“Tell me about it then, Ralph; perhaps I might be able to help you out?” suggested the other.

“All right, then, I will!” declared the driver, as he skillfully avoided a hole in the road ahead. “About three days ago I made a little discovery that bothered me. It seemed that some one was helping themselves to some things I kept in that room out in the barn, a place I had fitted up a long while ago as a sort of boy’s den, you know, where I kept all my treasures, books, games, stamp collection and coins, as well as a lot of other things.”

“Yes, I remember you showing us, though you didn’t stay in there long, I noticed,” Rob went on to remark, significantly.

“That was because I felt bad about something,” explained Ralph. “Fact is, I had just made an unpleasant discovery, which was to the effect that some one had for the second time been poking around among my things, and carried off a number of packets of valuable stamps that I knew positively I had left there on the desk, meaning to return them to the dealer.”

“But if this happened once before,” said Rob, “how did it come you neglected to put a padlock on the door?”

“I had my reasons,” answered Ralph stoutly, and with a flash of fire in his eyes. “First, because I hated to think that anything had to be locked up so as to keep employees about the place from helping themselves. Second, I wasn’t quite sure that my first loss was a certainty. Then again, Rob, I was figuring on laying some sort of trap so as to catch the rascal in the act, and settle the business.”

“But now you are sure a light-handed fellow has taken your things, what do you expect to do about it?” queried Rob.

“I ought to warn my father,” said the other, regretfully. “He hates a thief above all things. I’m sure he would discharge Peleg in a hurry. You see, Peleg has always been allowed to enter my den as he pleased; in fact, anybody could, because I trust the men who work for us.”

“Well,” Rob continued, significantly, “I hope before you tell your father you let me try to identify the thief, because I don’t believe it can be Peleg Pinder.”

Ralph turned hastily and gave Rob a strange look. Unconsciously he was already beginning to realize that Rob Blake could always be depended on to do the right thing when it came to a question of action.

“You’ve got a reason for talking like that, I’m sure, Rob?” he observed.

“I admit it,” came the answer, without the slightest hesitation. “Tell me first if you positively know that Peleg took your things?”

“Well, the evidence is only what you might call circumstantial,” admitted the other. “I remembered seeing him going hurriedly out of the barn an hour before I showed you and the rest of the fellows through there. He acted a bit guilty. I thought he avoided us; but the poor fellow has always been somewhat shy about meeting strangers, because he must know some mention will be made of his history, and that of his family. No, I can’t say I’ve got any positive proof he is the guilty one, if that’s what you mean.”

“I’ll tell you something, Ralph,” said the patrol leader, quietly. “Perhaps it may not mean much to you; but when a fellow becomes a scout, you see, he begins to study character, and notices a good many little things that show which way the wind blows, just as straws are said to do.”

“Go on, then, please; I’ll be glad to hear what you have to say, Rob.”

“It happened that when I was alone this morning I took a little stroll back of the barns, just to amuse myself by looking at the pigs, for they’re always amusing, in my mind. There I ran across Peleg, though at the time I didn’t know that was his name, or anything about him. What do you suppose the boy was doing?”

“Oh! I couldn’t guess in a year,” replied the other.

“Well, he had managed to pick up a young crow that had in some way broken its wing and couldn’t fly,” continued Rob, with a smile. “I suppose it would have been put out of its misery in a hurry by any ordinary farm hand; and perhaps Peleg himself might have fired at the black thieves if he found them getting at the corn in the field. But a wounded bird, and one in pain, distressed him. He was trying to mend that broken wing, and I found myself interested in watching how he succeeded.”

“That’s sure a queer thing for a farm boy to do,” admitted Ralph. “What could have been his idea, do you think?”

“I imagine he had more than one,” Rob replied, soberly enough. “In the first place, he was sorry for the poor thing, for he handled it as tenderly as if it had been a human being. Then I actually suspect that the boy has, deep down in his heart, a vague desire to do surgical work, though you might find it hard to believe.”

Ralph whistled.

“You don’t say?” he ejaculated, looking as though he hardly knew whether to laugh at the idea, or take what Rob was explaining seriously.

“I told you I was interested,” the other went on, “and I asked him a number of questions as to who had showed him how to go about mending a bird’s broken wing in that way. He said no one had, but it just seemed to be the natural thing for him to do. Honestly, Ralph, when I saw what a clever job he made of it I knew that boy had the making of a grand surgeon in him, if ever he found a chance to do the proper studying. It’s a gift, you know, with some people, and money can never purchase it. Clever surgeons are born, not made.”

Again Ralph puckered up his lips, and gave vent to a whistle, which seemed to be his pet way of expressing surprise.

“All that is mighty interesting, I own up, Rob,” he said, presently, after he had taken a little time to think matters over. “If it hadn’t been for this unfortunate happening, I’d be tickled half to death to try and encourage Peleg if he had secret ambitions that way. But why do you think, because he bothered mending a broken wing for a young crow, that he couldn’t have robbed me?”

“For this reason,” replied Rob. “Remember, I may turn out wrong, but I’m going on general principles when I say that I never yet have found that a fellow with such a tender heart could really be a bad case. So, on the strength of my observations, I want you to promise me that you’ll suspend sentence on Peleg until you have more positive proof.”

“I agree, and only too willingly,” said Ralph. “In fact, I’ll be glad to turn the whole case over into your hands for settlement. Do just whatever you think best about it. If you need any help, call on me. I’d be mighty glad to learn I was doing Peleg an injustice; for I’d try and make it up to him in every way I could. Shake hands on that, Rob, will you?”

So the agreement was ratified, and the other boys in the back seat did not even know what their chums had been discussing. It happened that Sim and Andy were engaged in a heated argument concerning something that they did not think the same about.

Shortly afterwards they arrived at the lake where they expected to do their fishing. A boat was procured, and after they had purchased some live bait from a man who lived near the water they started forth.

This was a sport which Rob and his two chums always enjoyed very much. Perhaps they might not meet with such good luck as if they had come early in the morning; but, then, no one can tell when the bass will take hold. It often happens that on a hot and still day nothing may be done until along about four in the afternoon when a breeze arises, with a spatter of rain in the bargain. Somehow, every fish in the lake seems to get ravenously hungry all at once, judging from the way in which they snap at any kind of bait.

“Let’s hope some such good luck comes our way, then,” remarked Sim, when Ralph had mentioned this peculiarity in connection with the gamiest fish that swims in fresh water, barring none. “The day has been warm and still enough, for that matter. There are signs of a shower later on, if those clouds mean anything over in the southwest. I guess we’d better not go too far away, Ralph, because for one I’d hate to get soaked through and through.”

“I’m taking the waterproof coverings from the car along, so that in case it does rain we can keep fairly dry,” explained Ralph, as they started forth.

For an hour they had very little luck. Then the conditions mentioned by Ralph seemed to suddenly come about, for the clouds covered the heavens, a breeze sprang up, and drops of rain began to fall.

“I’ve got one, and a hard fighter!” shouted Sim, as he bent his energies to the task of successfully playing his victim in order to tire the fish out, so a landing net might be successfully used.

“Here’s another, and just as big as yours, Sim!” ejaculated Andy from the bow.

By the time Sim managed to boat his catch, Rob was busily engaged; and, in turn, Ralph found plenty to do in handling an even more vicious fighter.

“Say, this is the best fishing I ever struck!” admitted Sim, some time later, as he cracked another capture on the head with a billet of wood in order to put it out of suffering, and then deposited the victim with a dozen others lying in the bottom of the boat.

The fun kept up furiously for half an hour more. Then the bass ceased biting almost as suddenly as they had commenced. Perhaps the fact that the clouds had broken, allowing the sun to shine again, had something to do with this change.