WOOD-WORKING

Title: Harper's indoor book for boys

Author: Joseph H. Adams

Release date: July 30, 2022 [eBook #68650]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1908

Credits: Richard Hulse and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

WOOD-WORKING

HARPER’S

INDOOR BOOK

FOR BOYS

BY

JOSEPH H. ADAMS

AUTHOR OF

“HARPER’S ELECTRICITY BOOK FOR BOYS”

AND JOINT AUTHOR OF

“HARPER’S OUTDOOR BOOK FOR BOYS”

WITH MANY ILLUSTRATIONS

HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS

NEW YORK AND LONDON

MCMVIII

Copyright, 1908, by Harper & Brothers.

All rights reserved.

Published April, 1908.

| PAGE | |

| INTRODUCTION | xi |

| Part I WOOD-WORKING |

|

| CHAPTER I—CARPENTRY | 3 |

| Tools: How to use them—The Work-bench—A Tool-rack—A Tool-chest—Joints—A Low Bench—A High Bench—A Step-bench—A Shoe-box—A Shoe-blacking-box—A Shoe-blacking-ledge—An Easel—A Clothes-tree—Hanging Book-shelves—A Corner Cabinet—A Chair—A Table—A Settle—A Suspended Settle—A Coal and Wood Box—A Flat-iron Holder—An Umbrella-stand—A Plant-box—A Final Word | |

| CHAPTER II—WOOD-CARVING | 38 |

| Method and Material—Tools—A Carver’s Bench—Chip-carving—A Frame for a Small Clock—Other Designs—Relief-carving—Mouldings | |

| CHAPTER III.—FRETWORK AND WOOD-TURNING | 56 |

| The Tools—The Practice of the Art—The Preparation of the Work—A Match-safe—A Wall-bracket—A Fretwork-box—Other Designs—Wood-turning | |

| CHAPTER IV—PICTURE MOUNTING AND FRAMING | 71 |

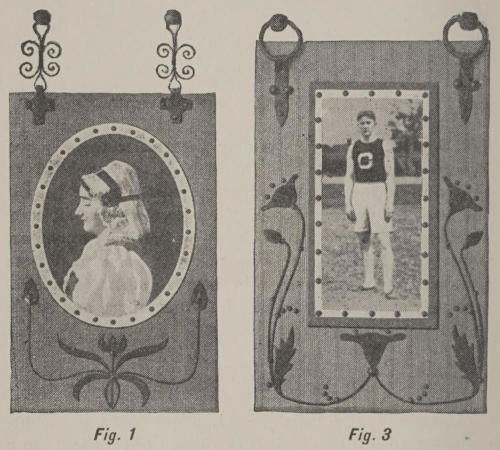

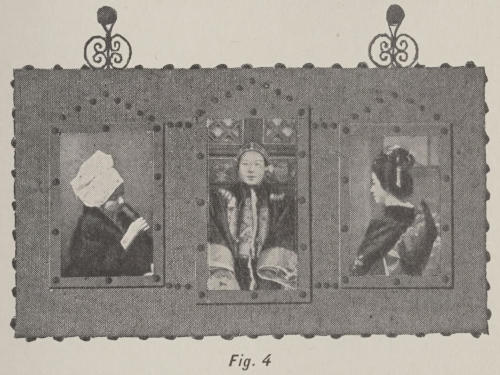

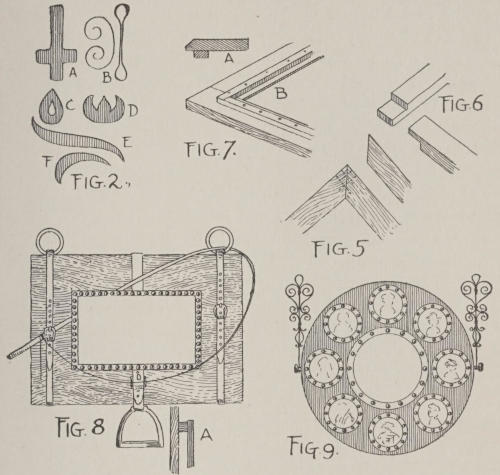

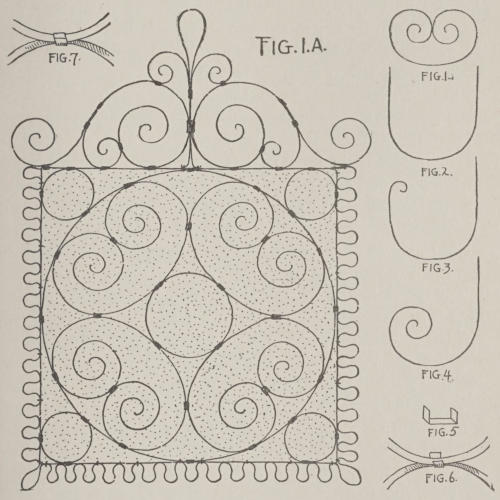

| A Dutch Head Mounting—A Dark Card Mounting—A Triple Mounting—Plain Framing—A Sporting Mount—A Round-robin Mounting[viii] | |

| Part II METAL-WORKING |

|

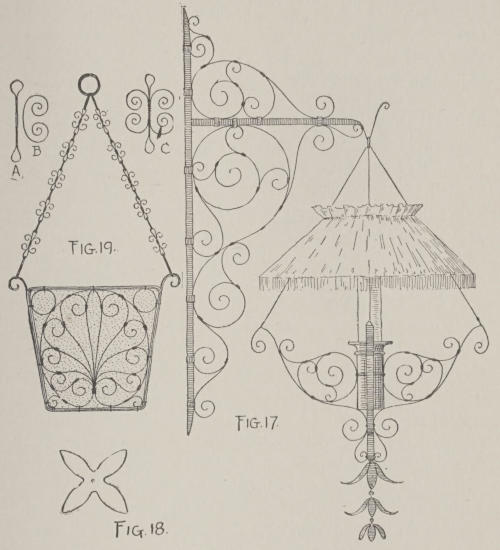

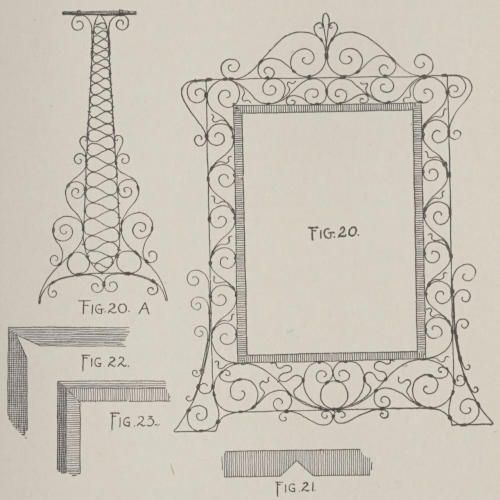

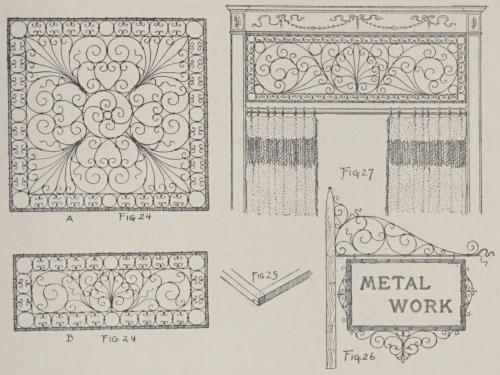

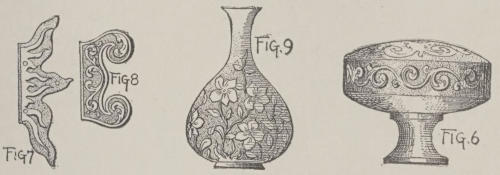

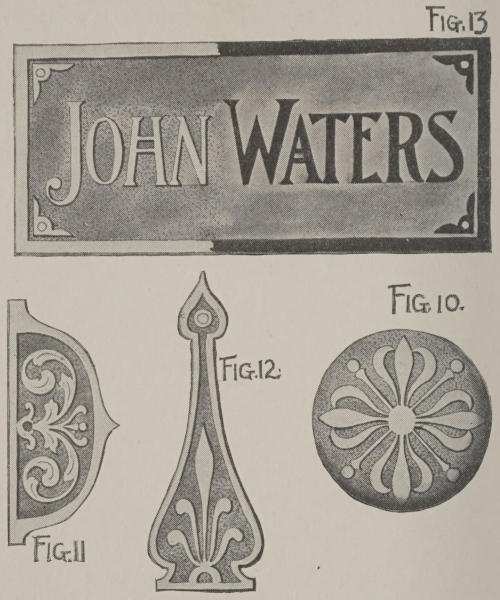

| CHAPTER V.—VENETIAN AND FLORENTINE METAL-WORK | 81 |

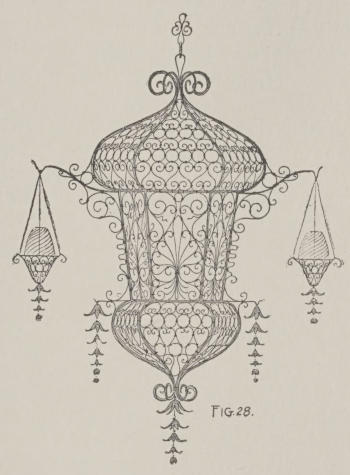

| Tools and Material—A Lamp-screen—Pattern-making—A Standard Screen—A Candlestick—A Candelabra—A Fairy Lamp—A Burned-match Holder—A Photograph-frame—A Handkerchief-box—A Sign-board—Double Doorway Grille—A Moorish Lantern | |

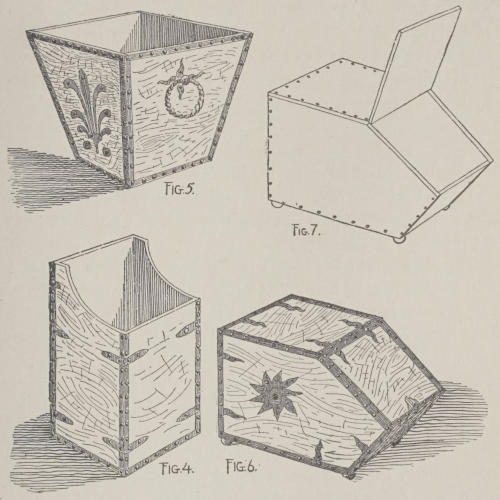

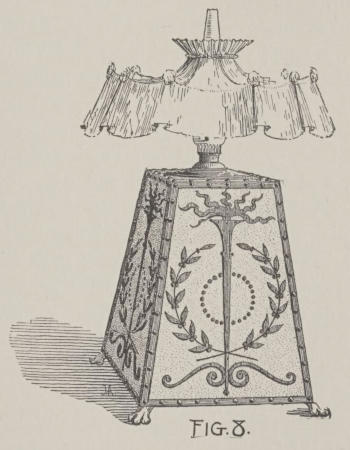

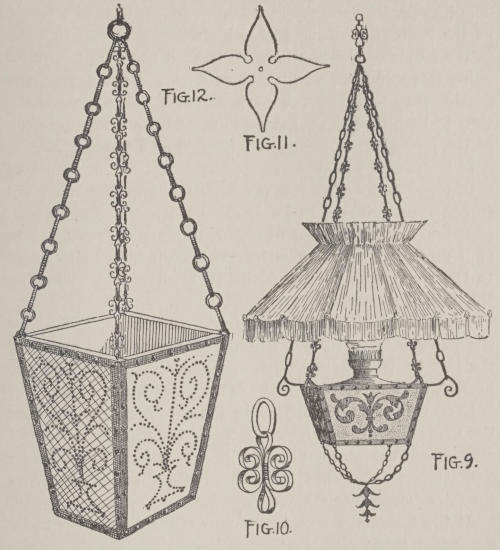

| CHAPTER VI.—METAL-BOUND WORK | 103 |

| A Metal-bound Box—A Wood-holder—A Plant-box—A Coal-box—A Table-lamp—A Hanging-lamp—A Hanging-plant Box | |

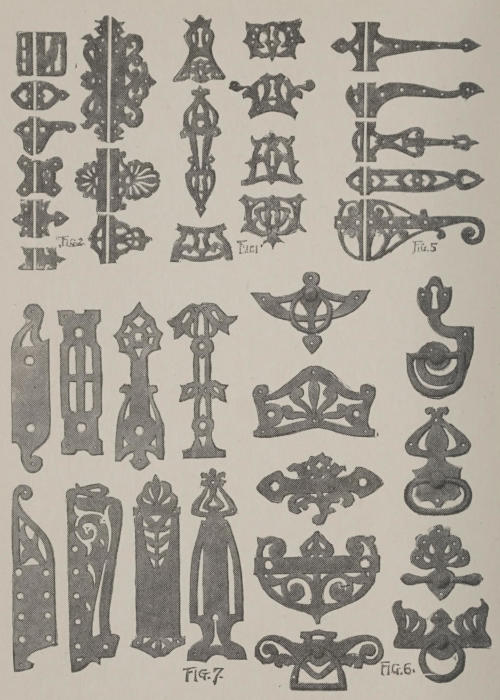

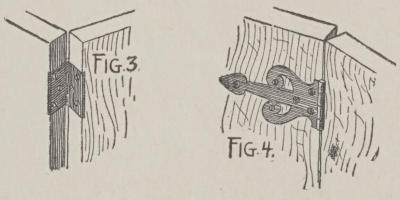

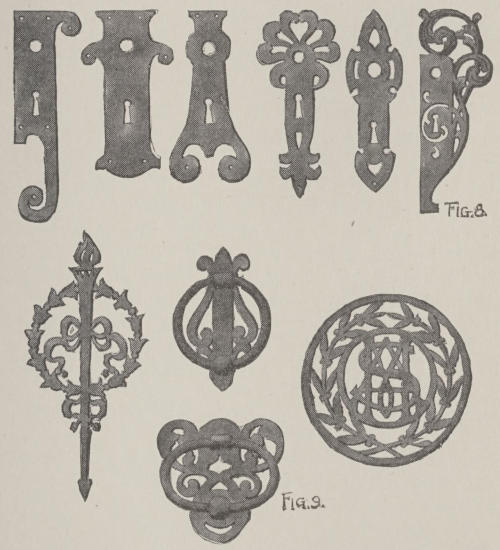

| CHAPTER VII.—DECORATIVE HARDWARE | 115 |

| Materials and Tools—Escutcheons—Short Hinge-straps—Long Hinge-straps—Drawer-pulls and Handle-plates—Door-plates—Large Lock-plates—Door-knockers and Miscellaneous Ornaments | |

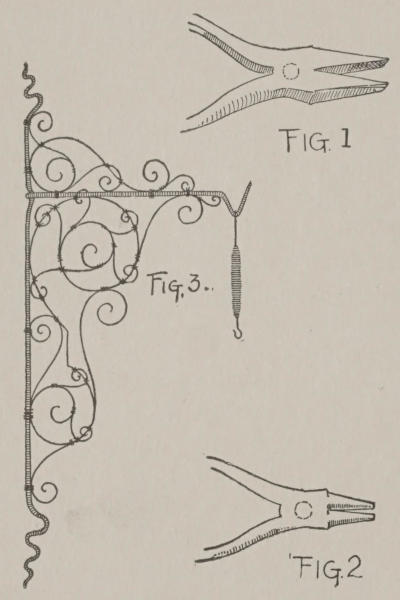

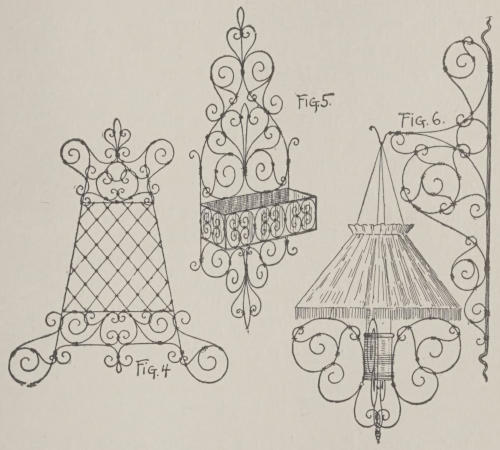

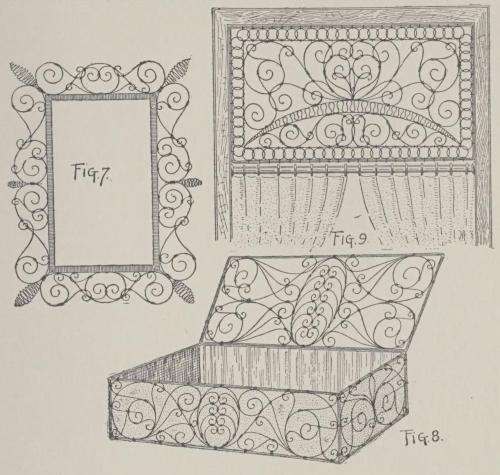

| CHAPTER VIII.—WIRE-WORK | 125 |

| A Bird-cage Bracket—A Photograph Easel—A Match-box—A Fairy Lamp—A Picture-frame—A Glove-box—A Window-grille | |

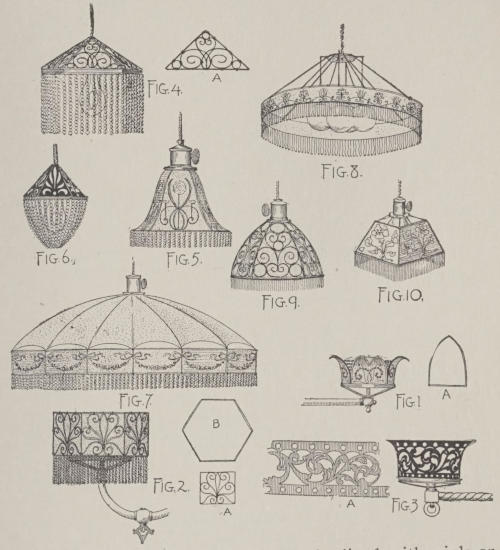

| CHAPTER IX.—GAS AND ELECTRIC SHADES | 133 |

| A Simple Gas-shade—Another Gas-shade—A Metal Shade—An Electric-light Screen—A Bell-shaped Shade—A Pear-shaped Shade—A Dome-shaped Shade—Another Dining-room Shade—A Canopy—A Panel Shade | |

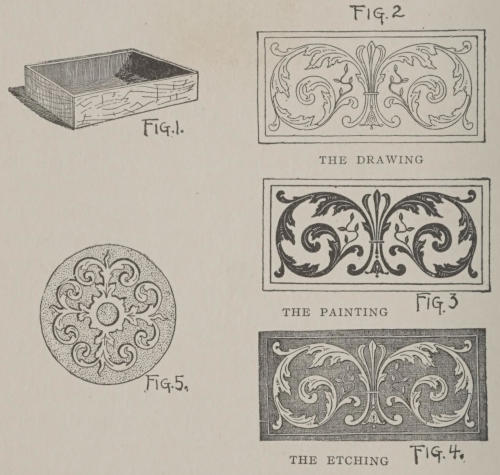

| CHAPTER X.—RELIEF ETCHING | 139 |

| Equipment—The Technique of the Process—The Acid Solution—Some Typical Designs | |

| Part III HOUSEHOLD ARTS |

|

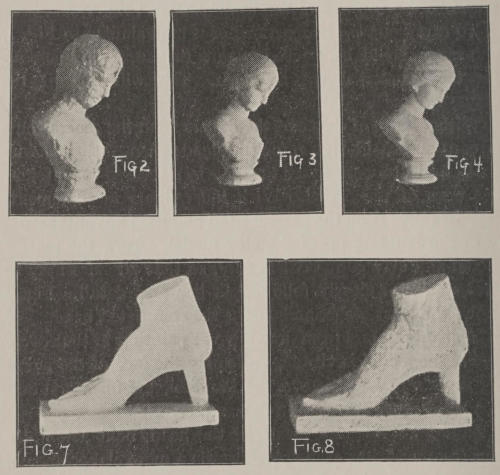

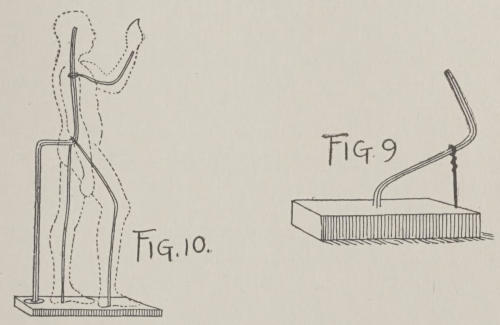

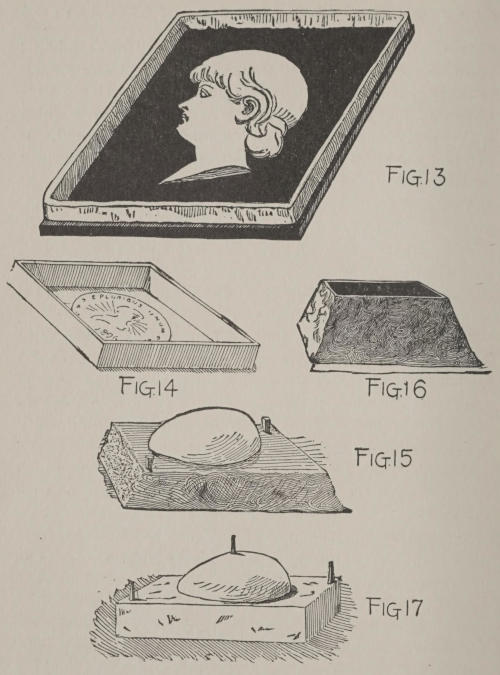

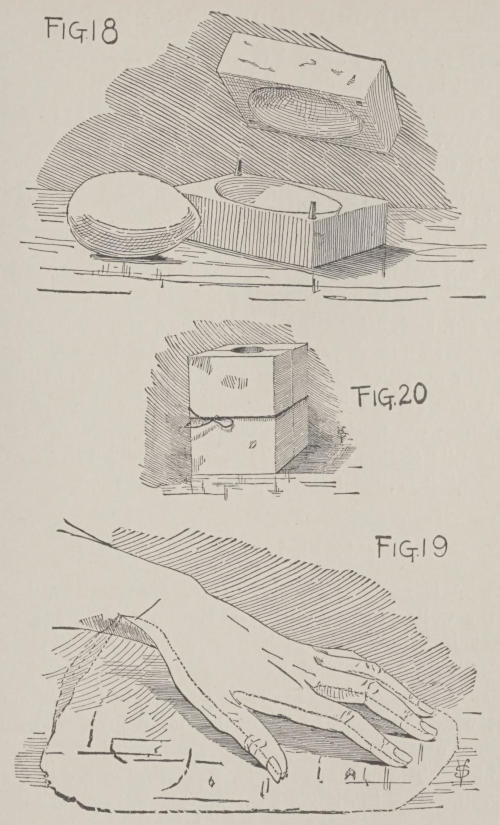

| CHAPTER XI.—CLAY-MODELLING AND PLASTER-CASTING | 151 |

| Tools and Methods—The Technique of the Art—Glue and Gelatine Moulds—Hollow Casting—Modelling a[ix] Foot—Bas-relief Modelling—A Medallion Head—Coin and Metal Casts—Plaster-casting in General—How to Find and Mount Signets | |

| CHAPTER XII.—PYROGRAPHY | 170 |

| Fire-etching on Wood and Leather—Explanation of Methods—A Platinum-point Outfit—A Variety of Work on Wood—Suggestive Designs—Leather-work | |

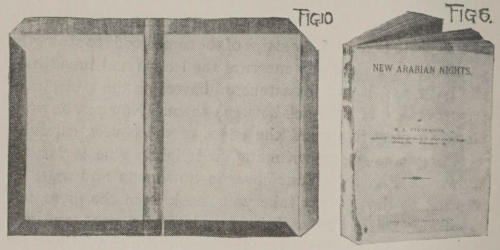

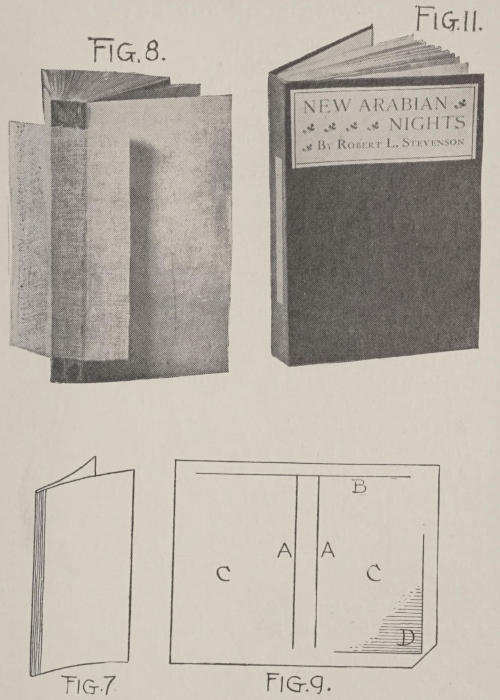

| CHAPTER XIII.—BOOKBINDING AND EXTRA-ILLUSTRATION | 186 |

| Sheets and Signatures—The Tools—The Practice of the Art—Rebinding Books—How to Extra-illustrate a Book—A Circulating Library | |

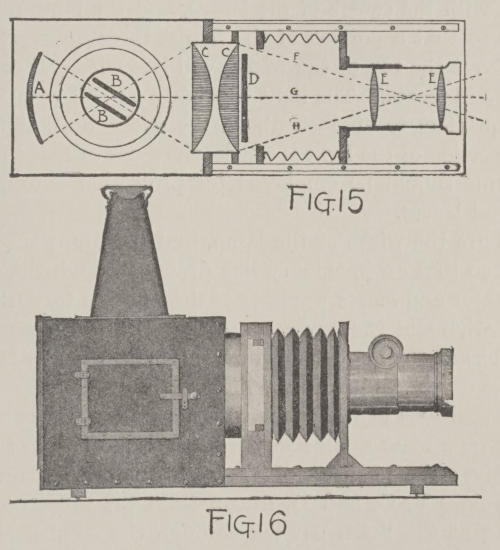

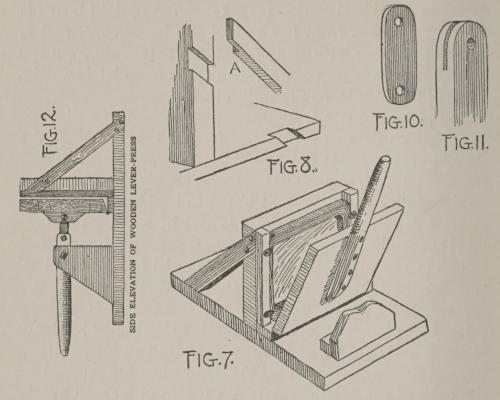

| CHAPTER XIV.—MAGIC LANTERNS AND STEREOPTICONS | 203 |

| A Home-made Magic Lantern—A Stereopticon—Lantern Slides by Contact-printing—Lantern Slides by Reduction | |

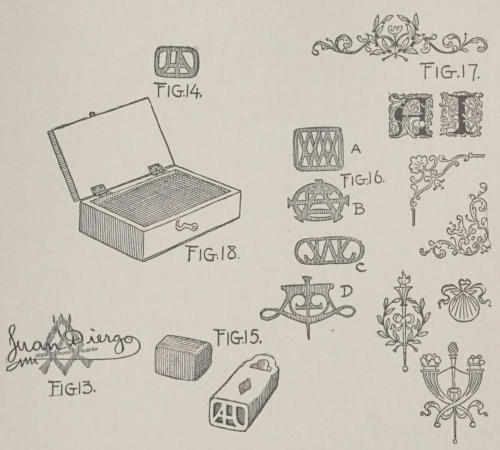

| CHAPTER XV.—PRINTING, STAMPING, AND EMBOSSING | 222 |

| A Simple Flat-bed Press—An Upright Press—A Lever-press—Stamping—Embossing | |

| Part IV ROUND ABOUT THE HOUSE |

|

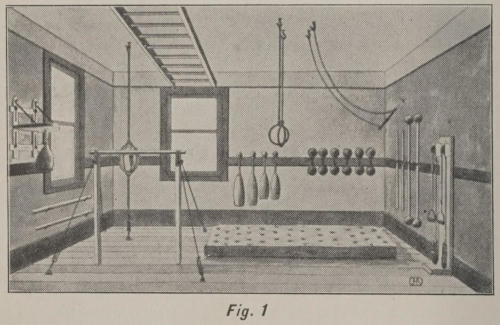

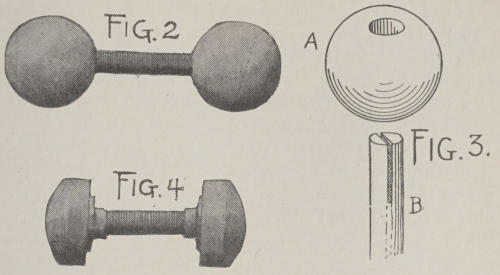

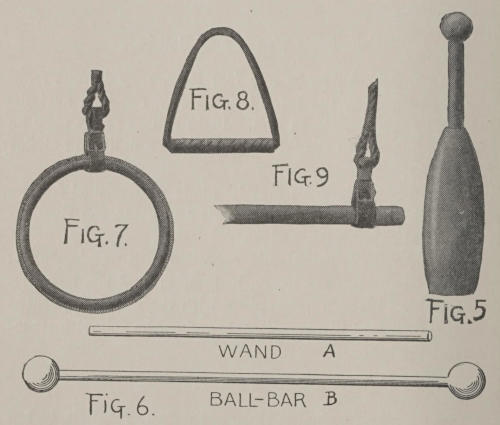

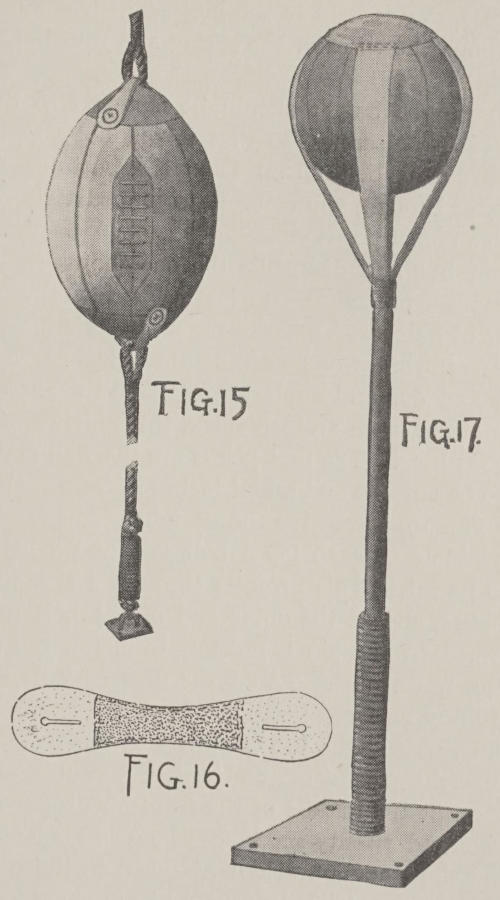

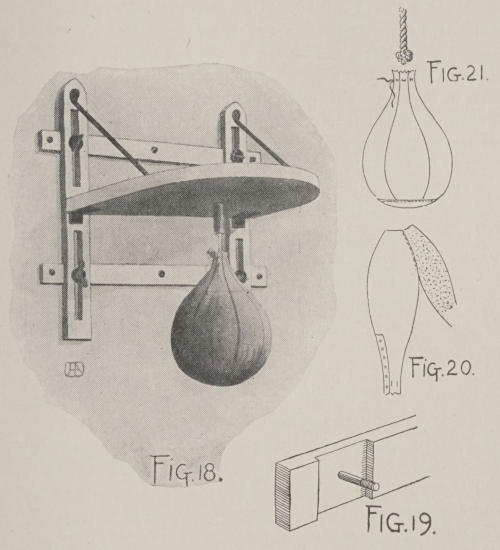

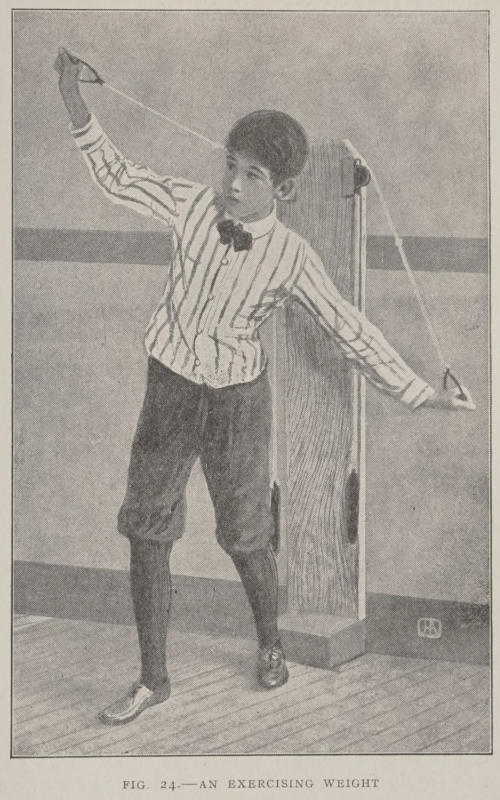

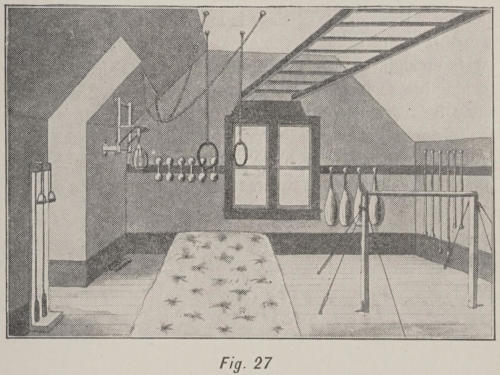

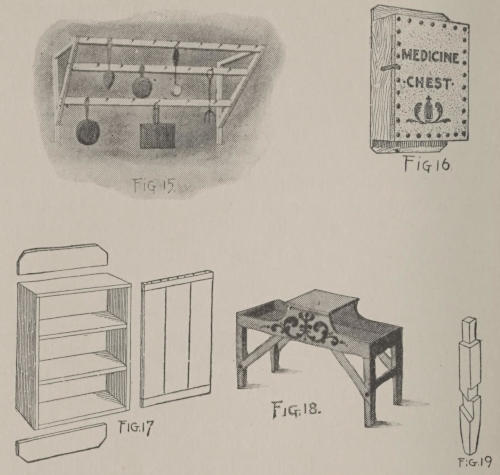

| CHAPTER XVI.—A HOUSE GYMNASIUM | 237 |

| Indoor Physical Development—Dumb-bells—Indian Clubs—Calisthenic Wands and Ball-bars—Swinging-rings—Trapeze Bars—Parallel Bars—A Floor Horizontal Bar—Striking-bags—A Medicine-ball—Pulley-weights and Exercisers—An Attic Gymnasium | |

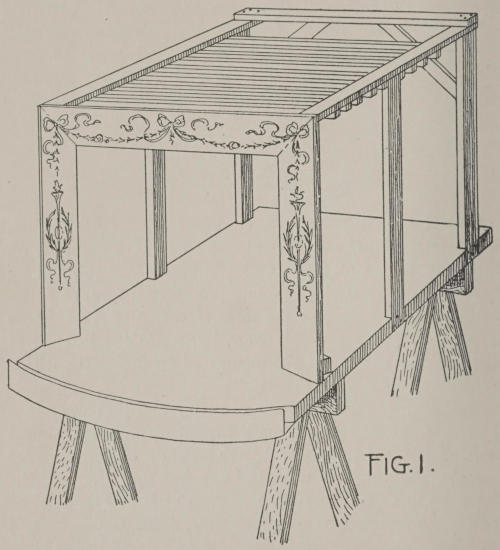

| CHAPTER XVII.—A MINIATURE THEATRE | 259 |

| Arrangement and Lighting—Scenery and Equipment—The Puppets[x] | |

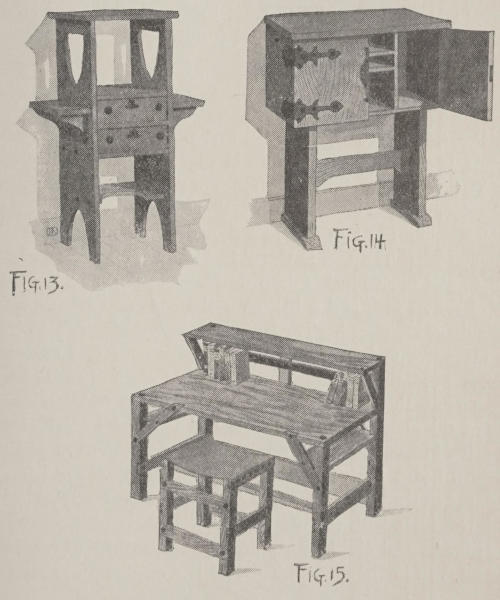

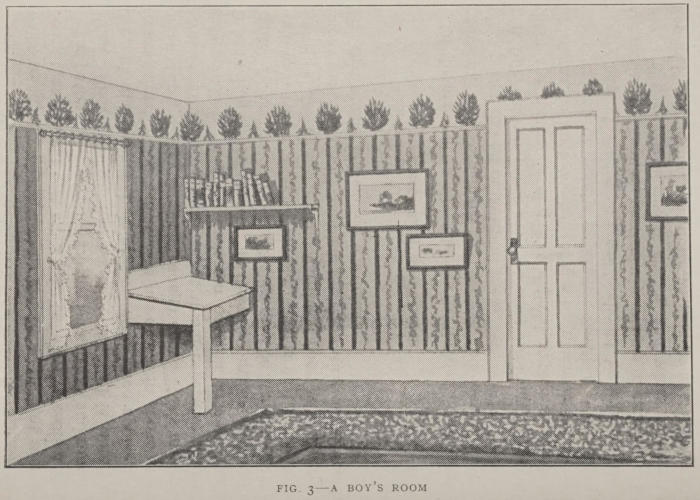

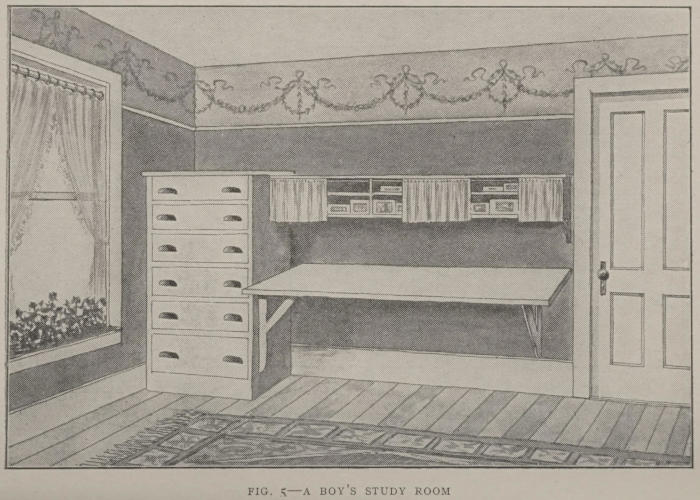

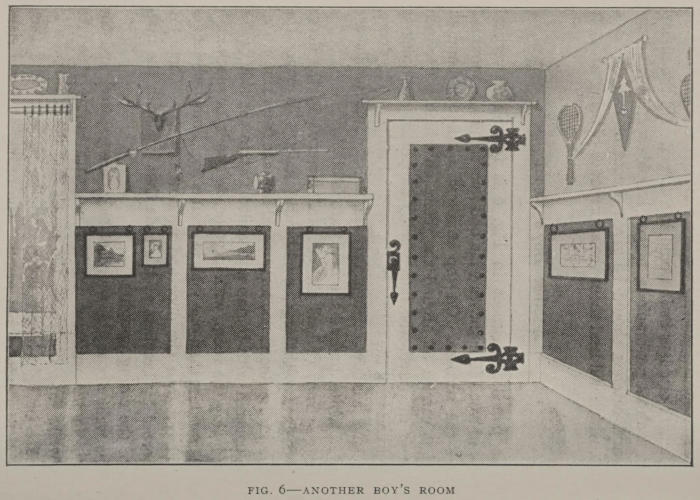

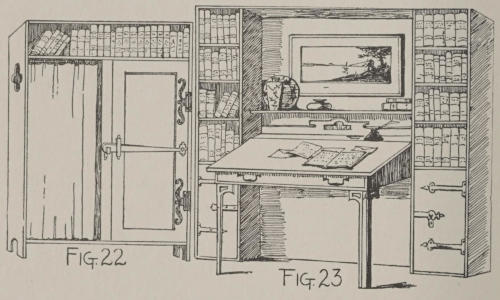

| CHAPTER XVIII.—FITTING UP A BOY’S ROOM | 267 |

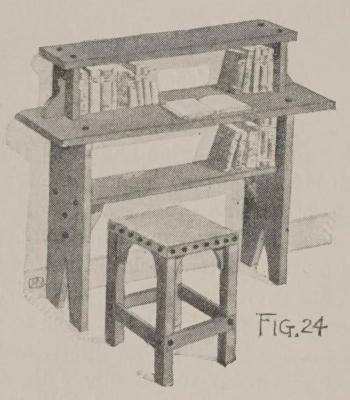

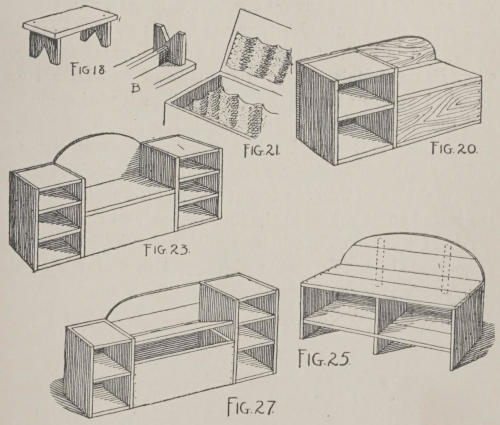

| Simple Methods and Materials—A Plain Chair—An Odd Chair—A Morris Chair—A Settle—A Box-desk—A Writing-table—A Whatnot—A Treasure-chest—Studying-table and Stool | |

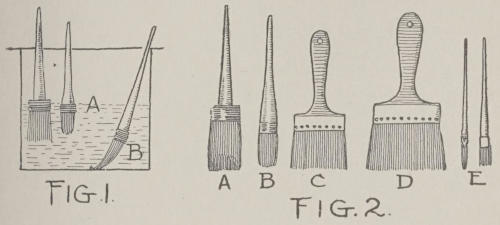

| CHAPTER XIX.—PAINTING, DECORATING, AND STENCILLING | 283 |

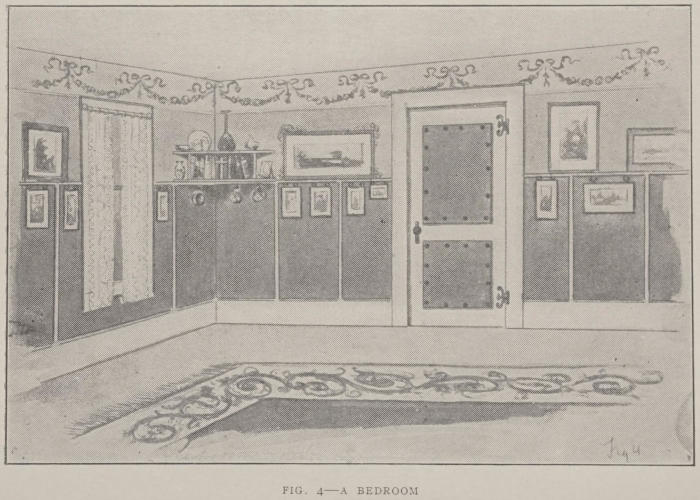

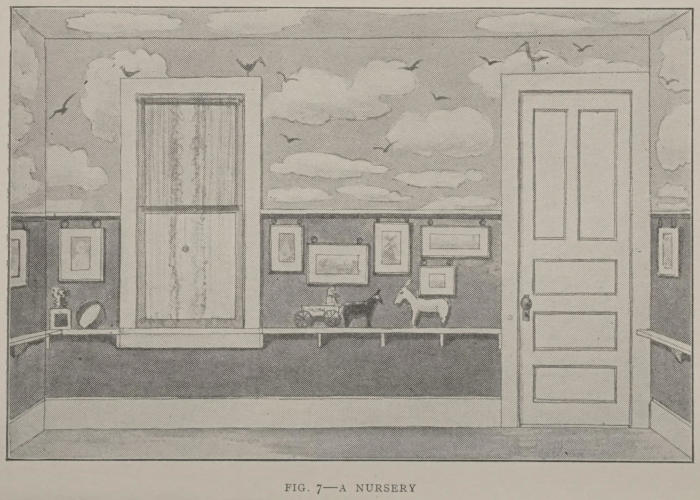

| How to Mix and Use Paints—Schemes of Decoration—Decorating a Bedroom—A Boy’s Room—Another Plan for a Room—A Nursery—Stencilling | |

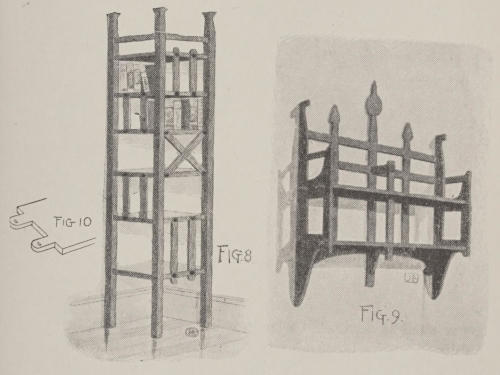

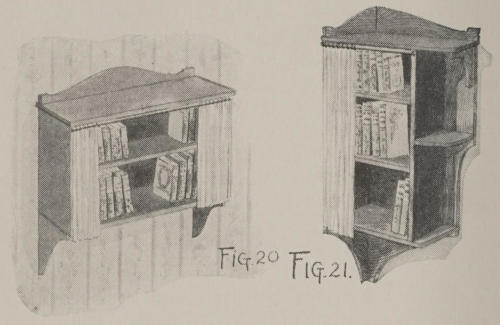

| CHAPTER XX.—NOOKS FOR BOOKS | 302 |

| A Variety of Practical Designs—A Wall-rack—A Book-nest—Another Book-rack—A Corner-nook—A Book-tower—Hanging-shelves—A Book-castle—A Book-chair—A Book-table—A Magazine-rack—A Box Book-case—A Nursery Book-rack—Another Book-rack—A Handy Piece of Furniture—A Book-ledge and Stool | |

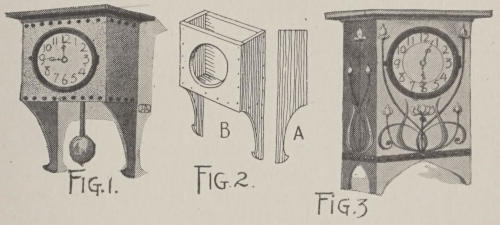

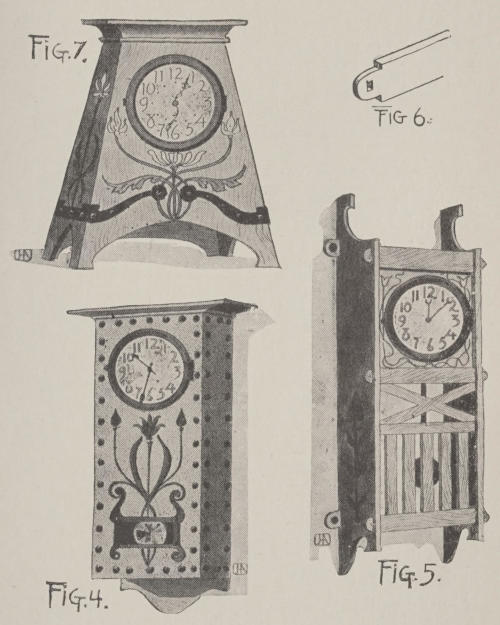

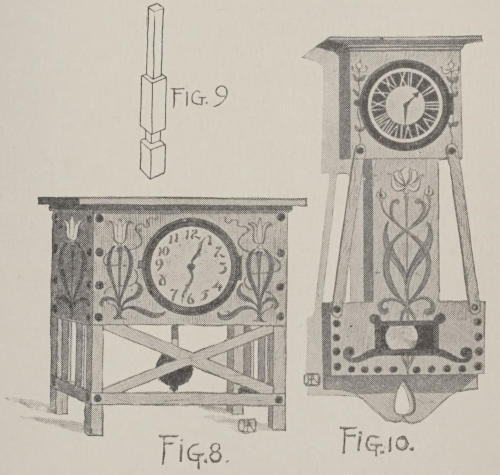

| CHAPTER XXI.—CLOCKS AND TIMEPIECES | 321 |

| Designs and Materials—A Bracket-clock—A Mantel-clock—A Wall-clock—A High Wall-clock—An Odd Mantel-clock—A Shelf-clock—An Old-style Timepiece | |

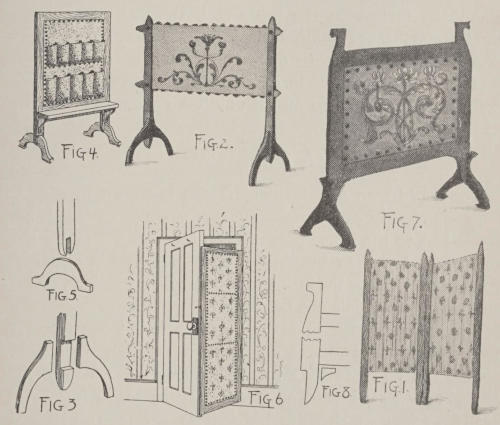

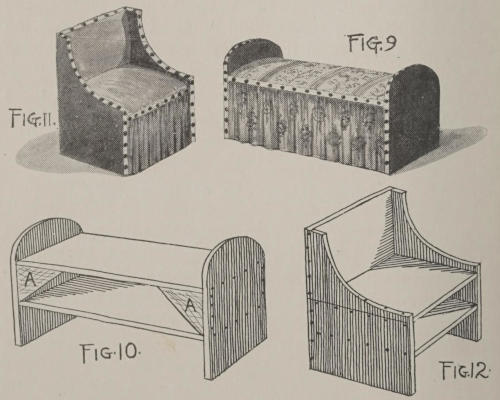

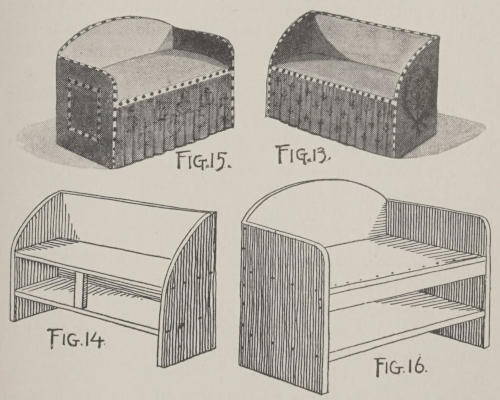

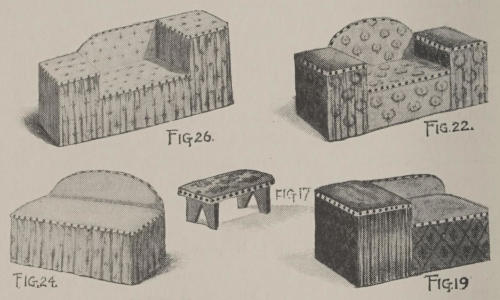

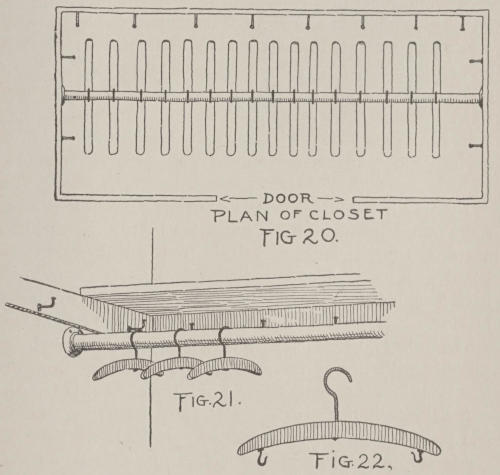

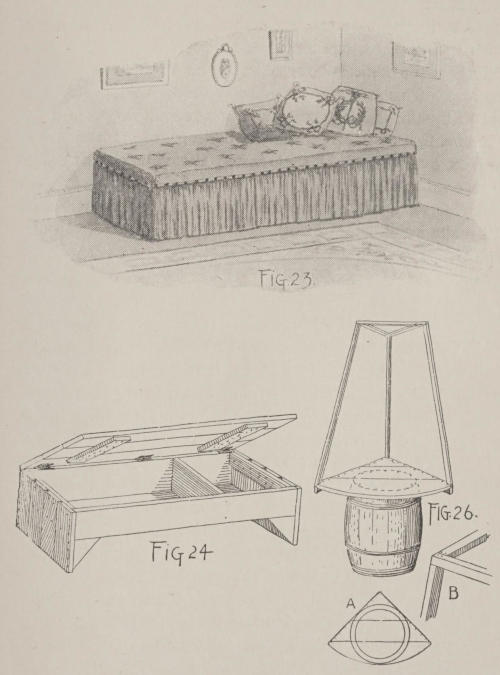

| CHAPTER XXII.—SCREENS, SHOE-BOXES, AND WINDOW SEATS | 331 |

| A Light-screen—A Fire-screen—A Shoe-screen—A Bedroom-door Screen—A Heavy Fire-screen—A Window-seat with Under Ledge—A Shoe-box Seat—A Dressing-room Settle—A Short Settle—A Foot-rest—A Combination Shoe-box and Seat—A Double Shoe-box and Seat—A Curved-back Window-seat—A Window-seat and Shoe-box | |

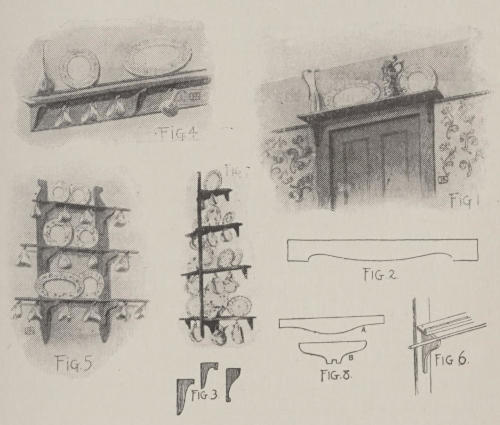

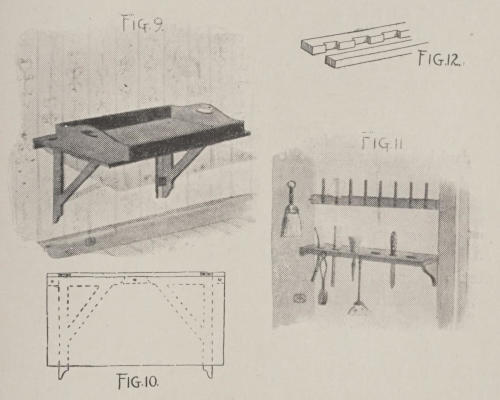

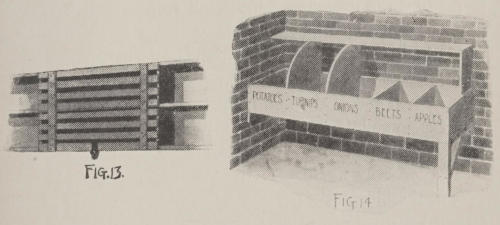

| CHAPTER XXIII.—HOUSEHOLD CONVENIENCES | 347 |

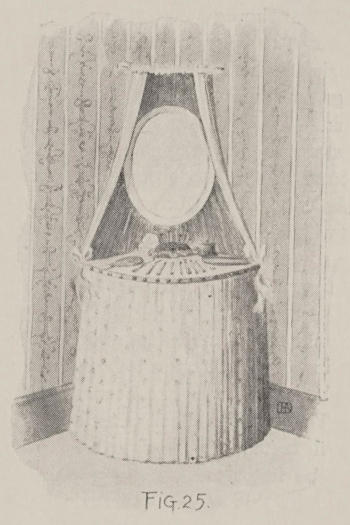

| A Plate-rail—A Cup and Plate Rack—A Cup and Plate Pyramid—A Butler’s Tray—Cup-pins and Brush-rack—Lock-shelves—A Vegetable-bin—A Spoon-bar and Saucepan-rack—A Medicine-chest—A Convenient Plant-tray—An Indispensable Clothes-press—A Divan—A Corner Dressing-table | |

The success of Harper’s Outdoor Book for Boys seems to insure a welcome for an indoor handy book, equally practical and comprehensive, which shall show how leisure time indoors can be spent most pleasantly and profitably. When stress of weather, or the coming of long winter evenings, or any other reason gives the indoor part of life a larger importance, this indoor handy book will be found an invaluable companion. Good books and good games have their value always, but there is also a large place for the joy of actual accomplishment. It is good to do things. It is worth while to learn to use hands and eyes in the production of working results. And when, as in the case of the explanation of this book, achievement goes hand in hand with amusement, it is clear that Mr. Adams and his associates are the best of companions for an indoor day or evening.

Expensive tools and apparatus are not called for. A boy should have good but not necessarily costly tools, and he should take proper care of them. Furthermore, whether his working-place is in his room or elsewhere, he should feel that he is put upon his honor to remove any rubbish and to avoid injury to floor or walls. Let us understand at the outset that the explanation in these pages can be followed[xii] at very little expense, but in this work, as in everything else, common-sense is necessary. To use one tool for work to which another is adapted, or to neglect one’s implements, or allow them to get wet and to rust or to become hopelessly dulled or nicked, is a sign of shiftlessness. A good workman always takes care of his tools, and he also keeps his work-bench in order. The very mention of work in a boy’s room, or even indoors, may excite fears of disorder on the part of the mother; but experience has shown that with care on the part of the boy, and some concessions from the mother, these fears are groundless.

It is desirable that a boy should have a place, whether it be in the cellar or attic, or a corner of his room, definitely devoted to his own work. It is also a useful training for him to feel that he is put upon honor both to confine his work to his own bounds, and also to “tidy up” whenever he leaves his task. With a little patience and oversight all this can be adjusted to the mutual satisfaction of the household and the boy.

In addition to the training in various directions which we have indicated, the suggestions in these pages will help the boy to make things which are useful—to become a contributor to his home. A glance at the Table of Contents shows, under “Wood-working,” an introduction to the use of carpenters’ tools, and instructions in making picture-frames and ornamented wood-carving. Of late years ornamental work for lamps, sconces, hinges, and a variety of purposes has steadily grown in favor, and the second division of the book tells how a great variety of decorative and useful objects in metal may be made. When so much experience[xiii] has been gained, the boy can readily take up more advanced work, such as modelling in clay, and plaster casting; bookbinding, and the kindred craft of extra-illustration; pyrography, or decorative work in burnt wood; printing, stamping, and embossing; and the construction and use of the stereopticon. In Part IV. the young craftsman is shown how he may employ the technical knowledge he has acquired in the fitting up and decoration of his room; in the building and operating of a miniature theatre; in the installation of a home gymnasium; and in the making of various objects of ornament and utility for the household. Amateur photography has been purposely omitted, since there are many excellent and practical manuals on the subject that have been published by the various camera manufacturers for gratuitous distribution. It is easy to see the possibilities for usefulness, for beauty, and for amusement in the home, which are brought within reach in these pages; and these instructions also represent possibilities for earning money. In, schools where manual training receives attention, and, indeed, in any school library, this book will prove peculiarly useful.

Here, as in the Outdoor Handy Book, it has been kept in mind that there will be neither fun nor profit in doing these things unless the way is made clear, and it is certain that the desired results will follow if the directions are carried out. Everything, therefore, has been tested, and all the instructions are put in simple, practical form. It is a friendly, well-tried, and reliable household companion that comes to young Americans in Harper’s Indoor Book for Boys.

Carpentry, or the science of making things out of wood, is the oldest and comes the closest to us of any of the applied arts and crafts. The earliest men made clubs at least. Later they began to build, to construct, and it is interesting to remember that this ability to construct is a faculty shared with man by the animals. There are many species of birds that build well-designed nests; the spider is a weaver; the bee is a geometrician; the ant is a tunnel builder; the beaver, in the construction of his dams and breakwaters, displays engineering ability of a high order. The vital difference between the animal and the human intelligence lies in the fact that the latter is progressive. The spider weaves just the same pattern to-day that he did when the Pyramids were young; the mathematical section of the bee cell is invariable; the mud-swallows build the same kind of houses as their remotest ancestors. The common explanation is that instinct and not reason guides the animal in his work, and instinct is a reproductive faculty, not an inventive one. It is for man alone to progress from the crude beginnings of an art to its highest and most perfect development.

Perhaps the first and most urgent need of all living creatures is for shelter. The oriole weaves his hanging nest; the beaver constructs his wonderfully domed house; primitive man builds his hut of interlaced boughs. But it is man alone who is not content with the first crude efforts; he is constantly aiming after something more substantial and better adapted to his increasing needs. So man becomes the true builder, and as wood is the simple and almost universally obtainable material, carpentry, or the art of working in wood, stands at the head of the applied sciences upon which the civilization of the race depends.

The average boy takes to carpentry as naturally as ducks take to water, and beginning with the tacks a baby boy will hammer in a board, the young builder goes on from the simple to the more complex forms until he attains the full mastery of his material and his tools. He has now obtained the dignity of manhood; he is a maker of things.

Once proficient in the art of cutting, joining, and fastening wood-work, and in the use and care of tools, a boy may begin to call himself a carpenter. But he must learn to work systematically and accurately if he is ever to become a genuine craftsman. In the first place, he should understand the possibilities and limitations of his tools. He should never use a chisel for a screw-driver, nor drive nails with the butt end of a plane. Good tools should have good care. Inanimate things that they are, they yet resent ill-usage, and retaliate, in their own way, by becoming dull and otherwise unfit for their work. Indeed, a good carpenter may be known by the condition of his tool-chest and work-bench. Carpentry, when properly carried on, is[5] a most fascinating occupation for out-of-school hours, especially in the winter season, when bad weather keeps one indoors. Needless to say, it may be made a profitable way of passing time as well as an amusing one.

The tools that a boy will need in order to do good joiner-work should be the same as carpenters use, but they may be smaller and not so cumbersome to handle. The set of tools in a chest, put up for the use of children and sold at toyshops, are not the sort that can be relied upon for good carpentry work, since they are usually dull and made of soft steel that will not hold an edge. Possibly the manufacturer thinks that he is justified in turning out this kind of rubbish, bearing in mind the old saying, “Children should not play with edged tools.” But the boy who is old enough to take up carpentry in earnest is entitled to the use of good and serviceable implements, and without them it is hardly worth while starting at the business.

Competition has brought down the cost of good tools to a point where they are not beyond the means of the average boy who is prepared to save his pocket-money. It is better to purchase only a small kit at first, and then to add to it from time to time, until the complete outfit is obtained.

Good tools may be purchased at nearly every hardware shop or general store throughout the country. For ordinary work you will require a good rip and cross-cut saw, with twenty and twenty-four inch blades, respectively; a claw-hammer, and a smaller one; a wooden mallet for[6] chisels, and to knock together the lap joints of wood; a jack and a smoothing plane; a compass-saw; a brace and several sizes of bitts, ranging from a quarter to one inch in diameter; a draw-knife; a square; awls; pliers; a rule; several firmer-chisels, and a screw-driver. There are many other useful tools, but they may be added as they are required.

It is a difficult matter to instruct a boy, by written description, how to handle tools; and rather than attempt it, I should advise the young workman to watch a carpenter at his work. Most carpenters are quite willing to have you follow their movements, and many of them will even offer advice, if they see that you are really interested. But remember that a good workman never likes to have a boy meddle with his tools, and you should not ask foolish or unnecessary questions.

Perhaps there is a carpenter’s shop near your home in which the owner may let you work occasionally (if you keep out of his way), and where, in the atmosphere of the craft, you will make faster progress than you can possibly do at home with no one to tell or show you how things should be done.

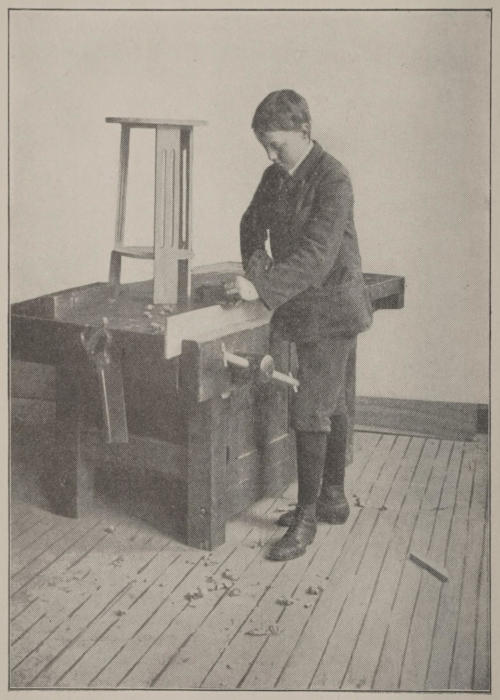

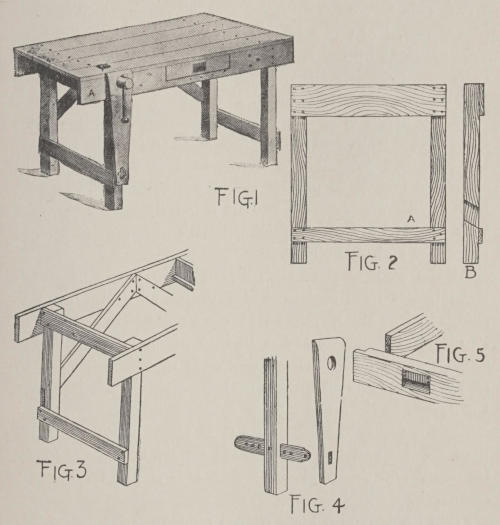

One of the indispensable pieces of equipment for the boy carpenter is a good work-bench. The bench must be substantially made, and provided with a planing-stop, a vise, and a drawer in which to keep small tools, nails, screws, and the various odds and ends that are employed in carpentry.

To begin with, obtain four spruce or white-wood sticks,[7] three inches square and thirty-six inches long, planed on all sides. These are for the legs. You will also need two pieces of clear pine, or white-wood, three feet long and six inches wide, and two more the same length and three inches wide. These pieces should be one and an eighth inches thick, and planed on all sides and edges.

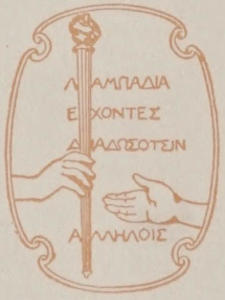

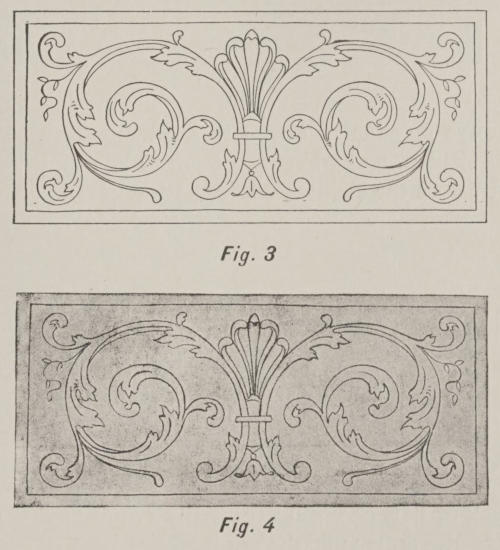

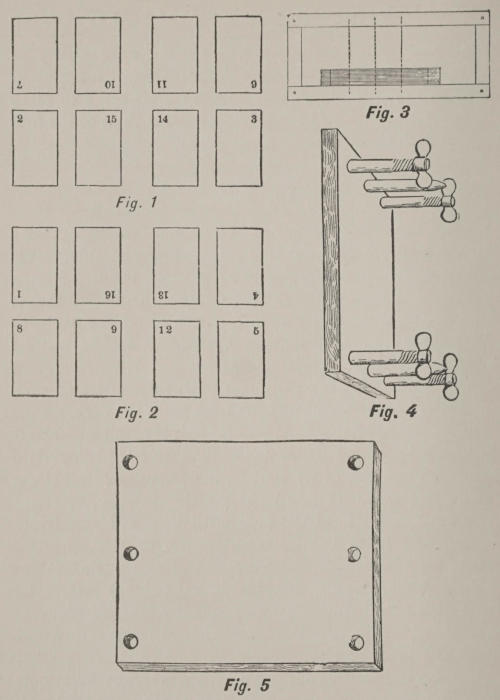

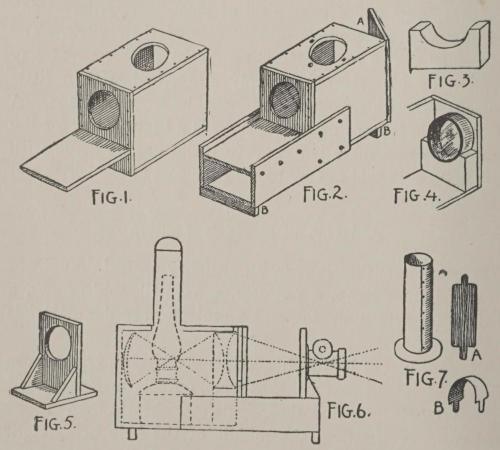

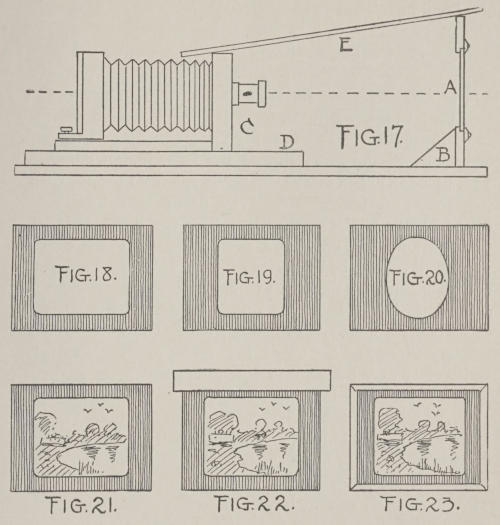

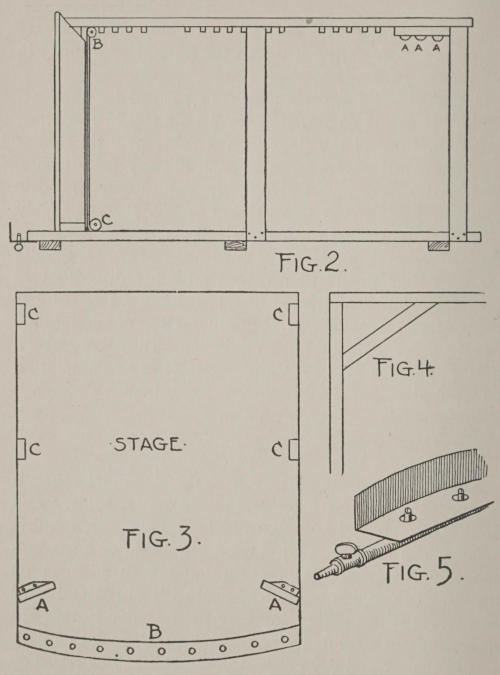

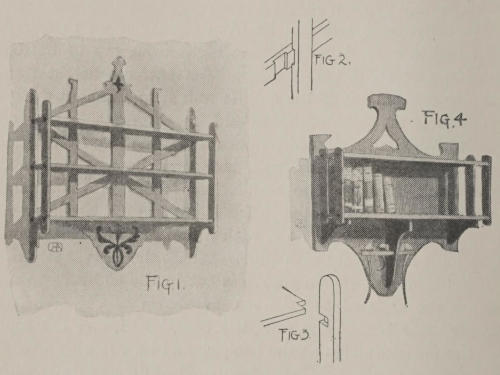

Fig. 1. Fig. 2. Fig. 3. Fig. 4. Fig. 5.

Lay two of the legs on the floor, three feet apart, and join the ends with one of the six-inch strips. Six inches up from the free ends fasten a narrow strip, as shown in Fig. 2 A. This finishes one of the end supports. Flat-headed iron screws, two and a half inches long, should be used for the unions, and a tighter joint may be secured by also using glue.

Prepare, in similar fashion, the other pair of legs, and, with two pieces of clear pine, or white-wood, five feet long, eight inches wide, and seven-eighths of an inch thick, bind the four legs together, as shown in Fig. 3. You should allow the boards to project six inches beyond the legs at both ends. These pieces are the side-rails, or aprons, and they should be securely fastened with glue and screws to the upper end of each leg.

At the back of the bench arrange two braces of wood, three inches wide and seven-eighths of an inch thick, as shown in Fig. 3. Bevelled laps are to be cut in the side of two legs, as shown in Fig. 2 B, into which the ends of the strips will fit flush. The upper ends of the strips are to be mitred (cut at an angle), and attached to the inside of the apron, as shown in Fig. 3.

For the top of the bench use clear pine planking not less than one inch in thickness. This should be fitted closely together, and fastened to the cross-pieces with stout screws.

From hard-wood a piece should be shaped for a vise-jaw thirty-two inches long, three inches wide at the bottom, and seven inches wide at the top. Near the bottom of the jaw an oblong hole should be cut to receive the end of a[9] sliding piece, which in turn is provided with several holes for a peg to fit into. A corresponding oblong hole is cut near the foot of one leg, through which the piece containing the holes will pass. This last regulates the spread of the jaw. This construction may be seen in Fig. 4, and its final position is shown in the illustration of the finished bench (Fig. 1).

Near the top of the jaw a hole is cut to receive the screw that is turned with the lever-stick to tighten the jaw. A bench-screw may be purchased at any hardware store, and fitted to the work-bench. If it should prove too much of an undertaking for the youthful workman, a carpenter will put it in place at a trifling cost. The wood screws are the cheapest, but the steel ones are the most satisfactory, and will cost about one dollar for a small one.

From the apron (at the front of the bench) a piece should be cut fifteen inches long and six inches wide. This opening will admit a drawer of the same width and height, and as deep as may be desired. Twenty-four inches will be quite deep enough.

Rabbets are cut in the ends of a front piece, and the sides are let into them, as shown in Fig. 5. The bottom and back are fastened in with screws, and the drawer is arranged to slide on runners that are fastened across the bench inside the aprons, as shown in the upper corner of Fig. 3.

At the front of the drawer a cove may be cut out, and a thin plate of iron screwed fast across the top of it, so that the fingers may be passed in behind the plate to pull out the drawer (Fig. 5). It will not do to use a projecting drawer-pull, as that would interfere with pieces of work[10] when clamped in the vise. In planing strips, or boards, that are too long for the vise to hold securely, a wooden peg, inserted in a hole at the opposite end of the apron from the vise, will be found convenient. Two or three holes may be made for boards of different widths, and the peg adjusted to the proper one as occasion requires.

A planing-stop, with teeth, may be purchased at a hardware store and set in place near the vise-jaw. The complete bench will then be ready for use.

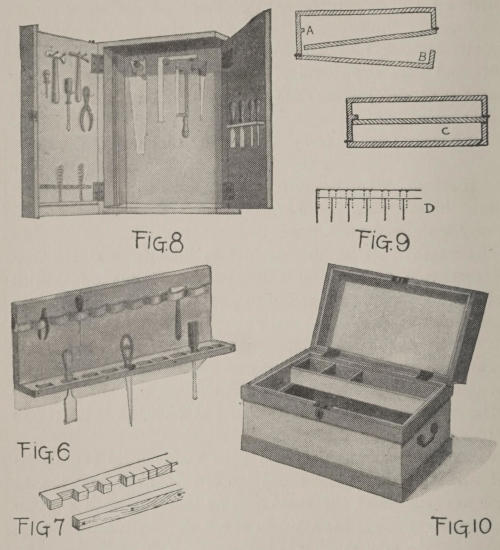

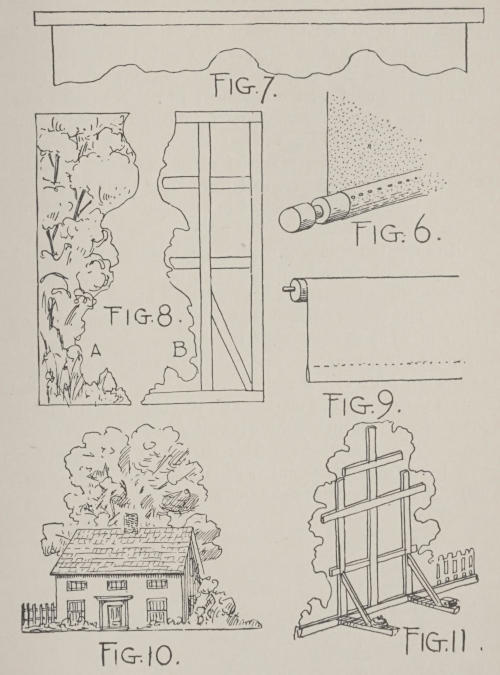

For the accommodation of chisels, gouges, screw-drivers, awls, compass-saws, pliers, and other small tools a tool-rack will be found convenient. It should be fastened against the wall immediately over the work-bench.

The one shown in Fig. 6 is thirty-six inches long and twelve inches high, with a ledge projecting two inches from the back-board. A leather strap is caught along the upper part of the board with nails to form loops, into which the tools are slipped.

The ledge is made from two strips of wood. One of them, one and a half inches in width, is cut with a saw, as shown in Fig. 7, and the superfluous wood, between the saw-cuts, is removed with a chisel. When all the notches are cut, a narrow strip, half an inch in width, is screwed fast to the notched strip. The ledge is then attached to the lower edge of the back-board with long screws, as indicated in the illustration.

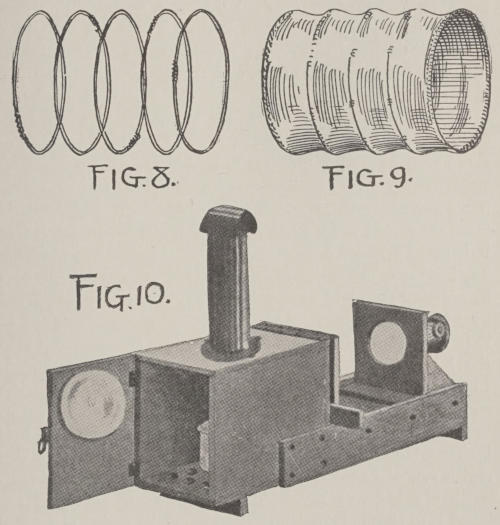

The hanging tool-cabinet shown in Fig. 8 should be constructed with two doors of nearly equal size, so that four instead of two surfaces may be available, against which to hang tools.

The body part of the chest is thirty inches high, twenty inches wide, and nine inches deep, outside measure. It is made of wood three-quarters of an inch in thickness, fastened together with screws and glue, and varnished to improve its appearance.

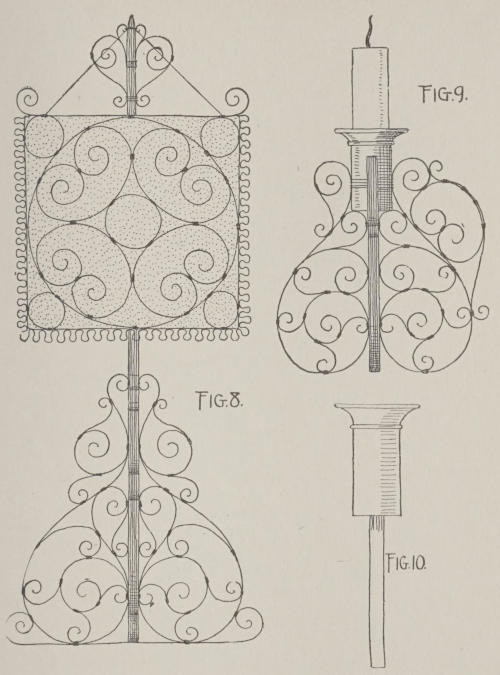

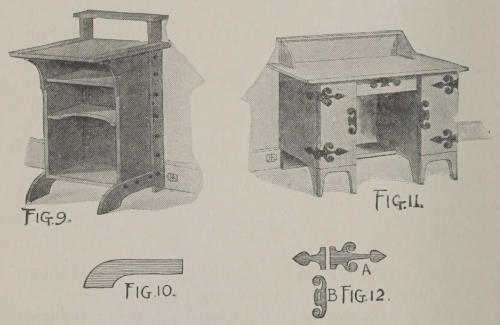

The right side of the cabinet is but three and a half inches wide, and to this the inner door is made fast with hinges, so that it will swing in against a stop-moulding on the opposite side, as shown at A in Fig. 9. A small bolt will fasten the door in place when shut in, and on both sides of this door hooks and pegs may be arranged for the reception of tools. The back-board of the cabinet may be used for hanging saws, squares, and other flat tools, as indicated in Fig. 8.

The outer door is provided with a side-strip (Fig. 9 B) of such size that when the doors are closed in and locked the appearance of the chest will be uniform, with a cross-section appearing, as shown in Fig. 9 C. With a little careful planning and figuring it will not be a difficult matter to construct this cabinet. Take particular care to have the doors fit snugly and close easily. The doors will keep their shape better if they are made from narrow matched boards, held together at the ends with battens, or strips, nailed across the ends of the boards, as shown in Fig. 9 D.[12] Two-inch wrought butts will be heavy enough for the doors, and a cabinet-lock at the edge of the outer door will make all secure.

Fig. 6. Fig. 7. Fig. 8. Fig. 9. Fig. 10.

On the inside of the outer door some tool-pegs may be arranged. Near the bottom a bitt-rack should be fitted,[13] with a leather strap formed into loops, as described for the tool-rack. Under each loop a hole should be bored in a strip of wood, into which the square end of the bitts will fit, and thus insure their orderly position. For chisels a similar set of pockets may be designed as shown in Fig. 8.

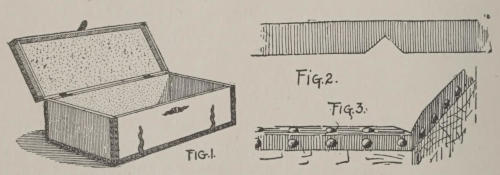

The tool-chest shown in Fig. 10 is twenty-eight inches long, fifteen wide, and twelve inches high. This is a good size for the accommodation of a moderate-sized kit of tools. The interior fittings should include two or three trays arranged to rest on runners and to slide back and forth, so that tools may be reached at the bottom of the chest without removing the trays.

Obtain a pine or white-wood board fifteen inches wide, and free from knots or sappy places. Cut two pieces twenty-eight inches long, and two shorter ones twelve inches long. These will form the top, bottom, and ends. Cut out the front and back pieces twenty-eight inches long and twelve inches wide; then with glue and screws form a box, and let it stand a day until the glue is hard. Make the joints as perfect and tight as possible, so as to present a good appearance; then mark a line around the box two and a half inches from the top.

With a rip-saw cut the cover free from the body, and plane the rough edges of the cut, so that the cover will fit the body snugly. Bind the lid and the top and bottom edges of the chest with a strip of wood three-eighths of an inch in width, as shown in the illustration; to look well,[14] the corners should be mitred. The lid is attached to the chest with stout hinges, and a lock is arranged at the front. Stout handles at the sides will be found a convenience.

Two or three coats of olive-green paint, with a slightly darker shade for the bands, will improve the appearance of the chest. To keep the hardware from rusting, the lock, hinges, and handles should receive a coat or two of black paint.

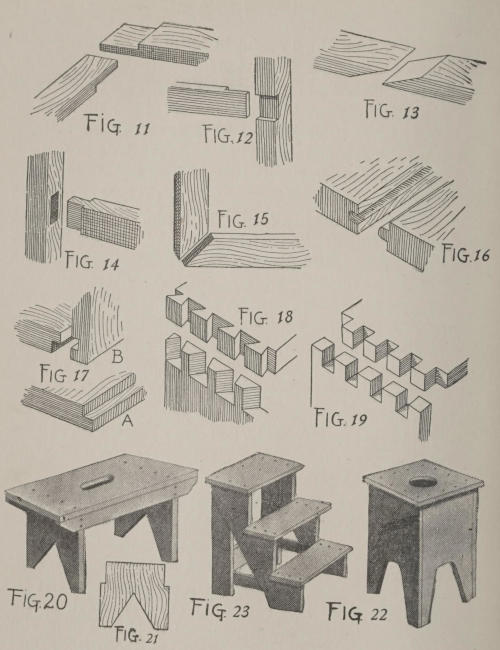

One of the first lessons for the young carpenter to learn will be that of making wood joints. Without good joiner-work there is no such thing as carpentry, and it is the sign-manual of the competent artificer. There are a great variety of joints employed in carpentry, but many of them are too complicated for the boy carpenter to make, and the simple forms will answer every reasonable requirement.

The easiest joint to make is the straight, or box, joint. It is constructed by butting the end of one board against the edge of another and nailing, or screwing, them fast.

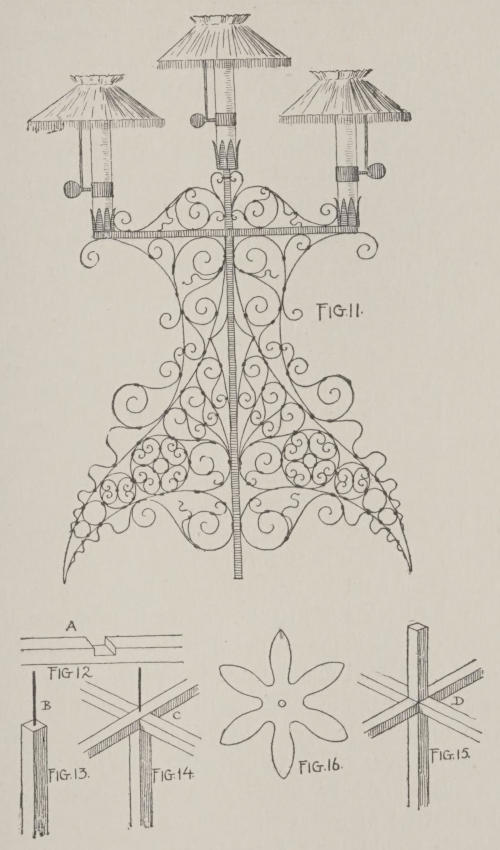

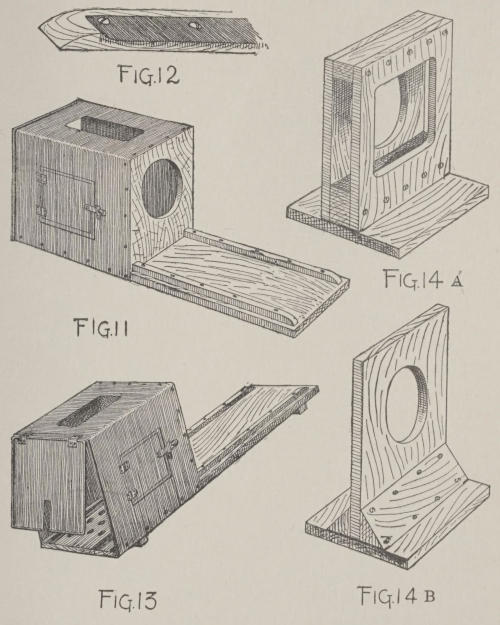

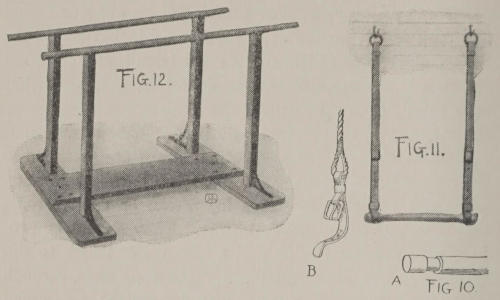

Fig. 11 shows a lap-joint made by cutting away a portion of the wood on opposite sides of the ends which are to be joined. When fastened the wood will appear as a continuous piece. For corners and angles, where a mitre-box is not available, the lap-joint is a very good substitute, and for many uses it is stronger than the mitred-joint, and, therefore, to be preferred.

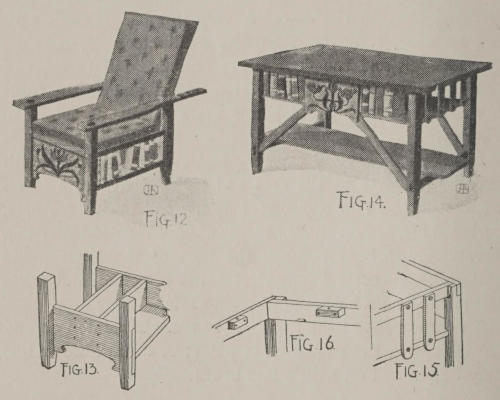

Fig. 12 is another form of lap-joint, where the end of a strip is embedded in the surface of a stout piece of wood.[15] This joint will be found useful in furniture work, and also for frame construction in general.

Fig. 13 is a bevelled lap-joint, and is used for timbers and posts, particularly under conditions where the joint can be reinforced by another piece of wood at one or two sides.

Fig. 14 shows a mortise and tenon. The hole in the upright piece is the mortise and the shaped end on the stick is the tenon. The shaped end should fit the hole accurately, and the joint is usually held with a pin, or nails, driven through the side of the upright piece and into the body of the stick embedded in the mortise. The mortise and tenon is used extensively in framing, and for doors, window-sashes, and blinds. In cabinet work it is indispensable.

Fig. 15 is the mitred-joint. In narrow wood it is usually cut in a mitre-box with a stiff back-saw to insure accuracy in the angles. The mitred-joint is employed for picture-frames, screens, mouldings, and all sorts of angle-joints.

Fig. 16 is the tongue-and-groove joint, and is cut on the edges of boards that are to be laid side by side, such as flooring, weather-boards, and partitions. Before wood-working machinery came into general use the tongues and grooves were all hand-cut with planes, but a tongue-and-groove plane is now almost obsolete, all this class of building material being mill finished.

Fig. 17 A is a rabbet. It is cut on the edges of wood, and another similarly shaped piece fits into it. It is also useful where wood laps over some other material, such as glass or metal. The inner moulding of picture-frames are always provided with a rabbet, behind which the edge of the glass, picture, and backing-boards will fit.

JOINTS, RABBETS, AND BENCHES

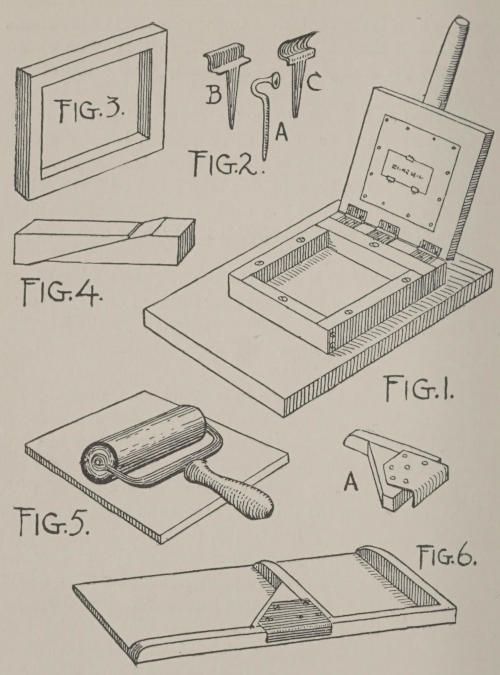

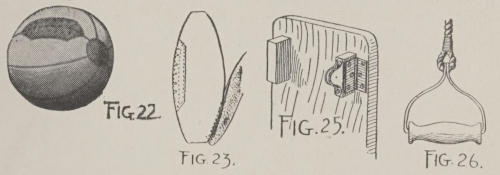

Fig. 11. Fig. 12. Fig. 13. Fig. 14. Fig. 15. Fig. 16. Fig. 17. Fig. 18. Fig. 19. Fig. 20. Fig. 21. Fig. 22. Fig. 23.

Fig. 17 B is a rabbet-joint made with a rabbet and groove. It is a good one to employ for box corners, and where the edges of two pieces of wood come together.

Fig. 18 is the dovetail-joint used for boxes, drawer corners, chests, and sometimes in cabinet work, where the corners are to be covered with mouldings or edging-strips.

Fig. 19 is the straight dovetail employed in the cheap construction of small boxes for hardware, groceries, and other wares. Since the edges are straight, this is the easier one to make, but care must be taken to have the fitting accurate.

Small benches are useful to work upon when sawing, nailing, and matching boards; and they are handy for many purposes about the house. The low bench shown in Fig. 20 is fifteen inches high and twelve inches wide, and the top is twenty-two inches long. The foot-pieces are cut as shown in Fig. 21, and at the upper end at each side a piece is cut out to let in the side-aprons. The aprons are three inches wide and seven-eighths of an inch thick; they are held to the foot-pieces with glue and screws. In the top a finger-hole is cut so that the bench may be quickly picked up and the more easily handled.

The high bench shown in Fig. 22 is twelve inches square and twenty-four inches high, with a top fourteen inches square. The wood is seven-eighths of an inch thick, and[18] all the joints are made with screws. A hand-hole is cut in the top with a compass or key-hole saw, and all the edges are sand-papered to round them off.

A step-bench will be found useful for various purposes. It does not take up so much room as a step-ladder and affords a more solid footing. The bench shown in Fig. 23 is thirty inches high, fifteen inches wide, and eighteen inches deep. The uprights that support the sides are five inches wide; the treads of the first and second steps are six inches wide, and that of the top step eight inches wide. The wood is seven-eighths of an inch thick, planed on both sides, and all the unions are made with screws. The cross-brace at the back and near the bottom is set into laps cut in the edges of the upright supports, and to prevent the support and side-pieces from spreading, stanchion-bars may be screwed fast to the sides, under the first tread, and to the foot of the uprights.

Two or three coats of paint will finish these benches and make them fit for use about the house.

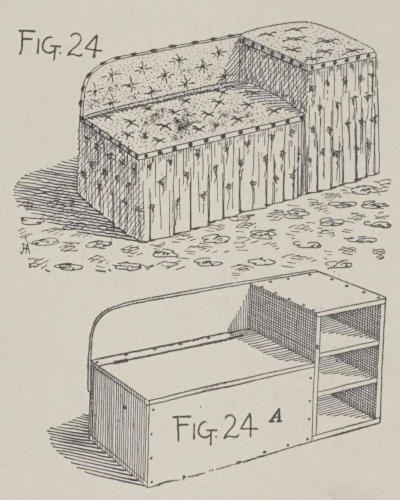

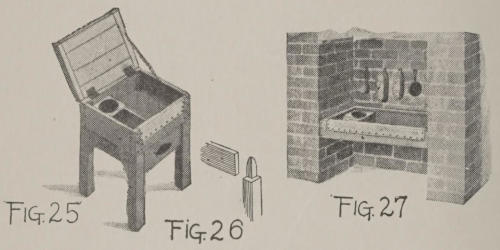

A shoe-box and seat (Fig. 24) is a useful piece of furniture in any bedroom. Two boxes, purchased at a grocery store, may be made to serve the purpose, but for a really neat and workmanlike job the frame should be constructed of boards three-quarters or seven-eighths of an inch in thickness.[19] A good size for the shoe receptacle is twenty-four inches high, fifteen inches deep, and sixteen inches wide. The seat-box should be thirty inches long, and fifteen inches high and deep.

Fig. 24. Fig. 24 A.

These boxes are to be attached to each other with stout screws, and a back the length of the two boxes, and having a rounded corner is to be securely fastened to the rear of each box, as shown in Fig. 24 A. In the shoe-box two shelves are screwed fast, and to the lower box a corner should be arranged on hinges so that it may be raised from the front. The back and seat and also the top of the shoe-box should be covered with denim, under which a padding of hair or cotton may be placed. The denim should be caught down[20] with carriage-buttons and string, the latter being passed through holes made in the wood and tied at the underside. Around the front and sides a flounce of cretonne or denim may be gathered, and hung from the top edge of the box and seat. If finished with gimp and brass-headed tacks it will present a good appearance. Where the drop-curtain at the edge of the shoe-box meets the seat the fabric is to be divided, in order that it may be drawn to one side when taking out or replacing shoes.

Fig. 25. Fig. 26. Fig. 27.

A coat of shellac, or paint, will cover such parts of the wood-work as are not hidden by the upholstery. Fig. 24 shows the finished article of furniture.

Every boy should own a shoe-blacking-box, such as is shown in Fig. 25. Otherwise, the brushes and blacking-box are apt to get widely separated, and are never at hand when they are wanted. Moreover, it is a slovenly practice to use a chair or stool as a foot-rest when engaged in polishing[21] one’s shoes, since the blacking is sure to discolor and dirty whatever it touches. This shoe-blacking-box is twenty-four inches high and eighteen inches square, the compartment being four inches deep. Four sticks, two inches square and twenty-four inches long, will form the legs. Each stick should be cut away at one end three-quarters of an inch deep for a distance of five inches, as shown in Fig. 26, so that when the side boards are fastened to them the joints will be flush. Two sides of each stick should thus be cut away, and the small end of the stick may be tapered slightly. The side boards, of three-quarter-inch wood and five inches wide, are screwed fast to the top of the legs.

A bottom sixteen and a half inches square is cut from boards and fastened inside the frame, where it is held in place with steel-wire nails driven through the lower edge of the side boards and into the edge of the bottom, all around.

Four brackets are cut and fastened with screws at each side of the box, under the side boards. A cover is made and hinged to the box, where it is prevented from falling too far back by a chain attached to the underside of the lid and to the inside of the box.

Over the front edge of the box bend a strip of zinc and tack it fast to both the in and outside of the front board. This will prevent shoes from chafing the wood away, and is easily cleaned when muddied up.

With a thin piece of wood make a division in the box at one side, where blacking and daubers may be kept. Also a drawer may be fitted to slide in and out under the box. It should be constructed, as described for the work-bench, and arranged to work on runners fastened to the inside of[22] the legs. Screw-eyes or staples should be driven into the ends of the brushes and daubers, so that they may be hung up in an orderly manner on hooks set in the wall immediately over the ledge.

A few thin coats of olive-green or light-brown paint will add to the appearance of this shoe-blacking-box, and the owner should take pride in keeping it clean, and the brushes in good order.

In a cellar where one of the chimneys is built with a recess, a shoe-blacking-ledge may be made from four boards five inches wide. The bottom is slatted, so that dirt will fall through. Fig. 27 shows quite clearly how this can be done. One end is partitioned off to hold the box of blacking.

The ledge is twenty-four inches high, and the front board is bound with a strip of zinc along the upper edge. The blacking-brushes may be kept in the tray, but it is a better plan to hang them up against the brick-work on steel nails. If the brushes are to be kept inside the tray, a lid should be made and hinged to the back strip of the tray. When the lid is raised it may be held against the brick wall with a wooden button.

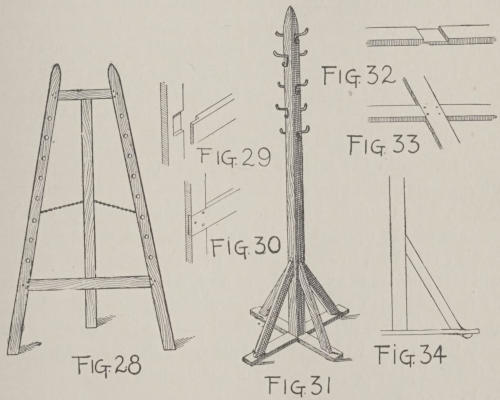

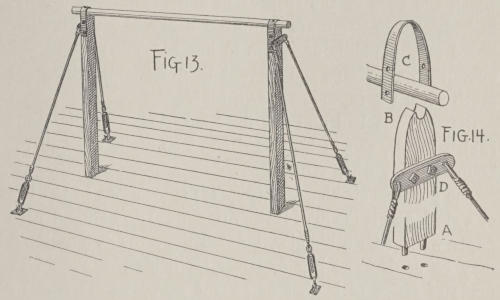

Boys who have a talent for drawing and painting would undoubtedly like to have an easel on which to work, and a good strong one may be made, at moderate cost, in the following manner (Fig. 28).

Obtain four pieces of clear white pine six feet long, two[23] and a half inches wide, and seven-eighths of an inch in thickness. These should be planed on all sides. Two of the sticks should be tapered off at one end, and slightly bevelled at the other. Nine inches from the top and twelve inches up from the bottom laps are to be cut in the sticks at the back, as shown in Fig. 29. Into these the ends of cross-pieces will fit. If the concealed lap is too bothersome to make, it can be cut clear across the sticks, as shown in Fig. 30. Glue and screws will make a strong joint.

Fig. 28. Fig. 29. Fig. 30. Fig. 31. Fig. 32. Fig. 33. Fig. 34.

The remaining long stick is the back support, or leg, and is to be hinged to the upper cross-piece. With this leg the easel may be pitched at any angle, and to prevent it from[24] going back too far a guide-chain should be attached to the leg, and the ends secured to the back of each upright with staples. Holes are bored along the uprights at even distances apart, and two wooden pegs are cut to fit snugly in the holes, and so hold a drawing-board or canvas-stretcher.

A clothes-tree is a most serviceable article of furniture, and helps a boy to form habits of neatness and orderliness in the care of his wearing apparel. To make the one shown in Fig. 31 obtain a clear pine or ash stick one and a half inches square and five feet long for the upright, or staff. Also two pieces eighteen inches long, two inches wide, and three-quarters of an inch thick for the feet; and four braces twelve inches long, one and a half inches wide, and three-quarters of an inch in thickness.

Cut a lap in the middle of each foot-piece, as shown in Fig. 32, and with glue and screws fasten them securely together, as shown in Fig. 33. Screw this foot fast to the bottom of the upright stick, and strengthen the four projecting feet with braces bevelled at the ends, so that they will rest against the upright and on the foot, where they can be fastened with screws, as shown in Fig. 34. Under the end of each foot, the half of a small wooden ball, or a castor, may be arranged to raise the tree from the floor. With a chisel and plane taper the top of the upright stick, as shown in Fig. 31.

At a hardware store purchase eight hooks and arrange them in alternating pairs, as shown in the drawing. The[25] wood-work should be shellacked or painted to give it a finished appearance.

When hanging clothes upon this tree place the coat, vest, and trousers on the lower hooks, the shirt and underclothing on the hooks next above, and on the top hooks the necktie and collar and cuffs. When dressing, the clothing needed first will then be the nearest to hand.

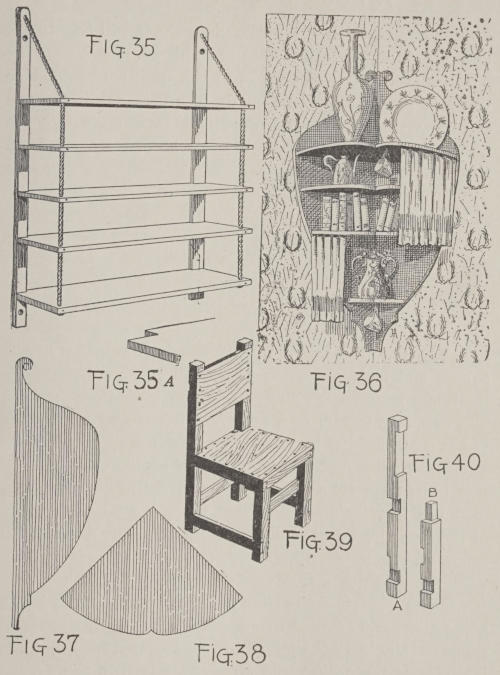

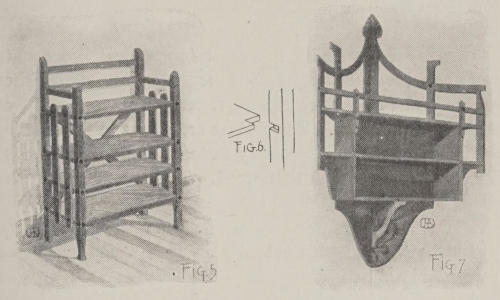

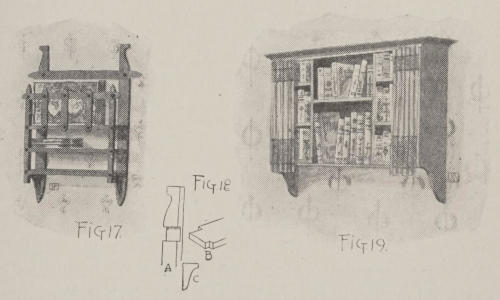

In a room where space cannot be given up to a standing bookcase, it may be possible to arrange a set of shelves to form a book-rack that will hang against the wall. The construction of the hanging shelves shown in Fig. 35 is very simple, and will require but a few boards, two wall-strips, and a few yards of strong rope.

For the shelves, obtain five pine boards eight inches wide, seven-eighths of an inch thick, and from three to four feet long; also two pine strips three inches wide, an inch thick, and four feet long. In the rear edge of each board, at the ends, cut notches three inches long and an inch wide, as shown in Fig. 35 A, into which the wall-strips will fit. Round off the top of each wall-strip and screw them fast to the notched edges of the shelves, first boring gimlet holes in both strips and shelves to prevent splitting of the wood.

Half-inch holes at the top of each wall-strip will admit the suspension rope, which is of manila, and half an inch in diameter. Knot one end of the rope and pass it up through holes made at the outer corners of each shelf, and finally through the hole at the top of the wall-strips, and cut it off[26] three inches back of the hole. With a gouge-chisel a groove should be made at the back of the wall-strip for an inch or two below the hole, so that the rope end may be carried down and ravelled out. It can then be glued and held fast to the wood with staples. Where the rope passes through the hole in each shelf, drive several long steel-wire nails into the edge and end of the board, allowing the nails to pass through the rope and into the wood.

Paint or varnish the wood-work, and securely anchor the wall-plates with stout screws driven into the frame timbers, through the lath and plaster of the wall.

A corner cabinet of odd design and simple construction is shown in Fig. 36. The total height of the wall-plates should be thirty-four inches, and at the top the shelf measures eighteen inches across. Each shelf is rounded out at the front so as to afford more surface on which to place books and bric-à-brac. The ends of each shelf are securely attached to the side or wall-plates with screws, thus insuring a perfect anchorage and a strong construction.

Fig. 37 is a plan showing the shape of the sides or wall-plates. At the widest part they should measure twelve inches across. Fig. 38 is a plan of the top shelf, which is followed in shape by the others. They decrease, however, in size as they near the bottom. The notch at the middle of each shelf breaks the long curved line in a pleasing manner. Two light metal rods from which curtains hang may be arranged under the top shelf and the one next the bottom. Shellac or paint of some appropriate shade will add to the appearance of this useful piece of furniture.

HANGING BOOK-SHELVES AND CHAIR CABINET

Fig. 35. Fig. 35 A. Fig. 36. Fig. 37. Fig. 38. Fig. 39. Fig. 40.

When fastening this cabinet to the wall, care should be taken to pass the screws securely into the studding or uprights. Otherwise the screws might pull out under the accumulated weight, and a fall would be disastrous to both the cabinet and its contents.

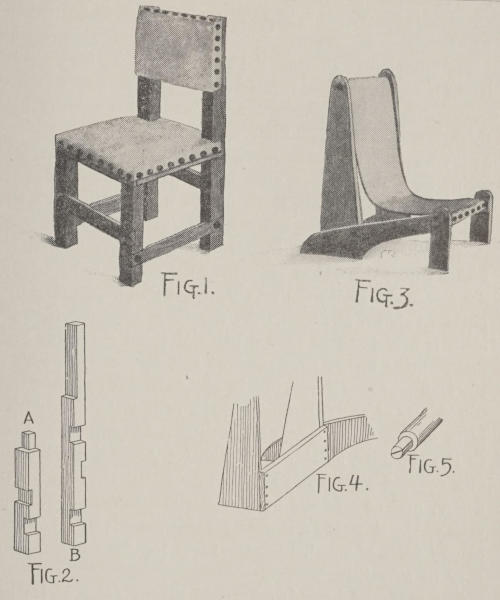

The construction of a chair is perhaps as interesting as anything in carpentry. The one shown in Fig. 39 may be made from either soft or hard-wood, the joints being all open and simple to cut.

The legs are two inches square, the seat is sixteen inches square and eighteen inches high, and the back posts are thirty-six inches long. The front and back posts are cut out, as shown in Fig. 40 A and B. These receive the cross-pieces that bind the legs and back together. The posts are two inches wide and three-quarters of an inch thick. The side braces are set two inches up from the floor and the back one four inches. The front brace is let into the rear of the front legs, and is eight inches from the floor to the lower edge.

The seat is made from matched boards, and the back, ten inches wide, is made from a single board, all the joints being glued and screwed together. Chairs that are made in shops usually have the joints dowelled or mortised, but the lap-joint is the easiest and strongest one to make. Take care, however, that the cuts are accurately sawed, and that[29] the cross-pieces fit the laps so snugly that a mallet is necessary to help drive the strips home.

The seat and back of this chair may be covered with denim, leather, or other upholstery material, drawn over curled hair, or cotton may be used for padding, and fastened down around the edges with large flat-headed tacks or upholstery nails. Shellac, varnish, or paint may be used to give the wood-work a good appearance.

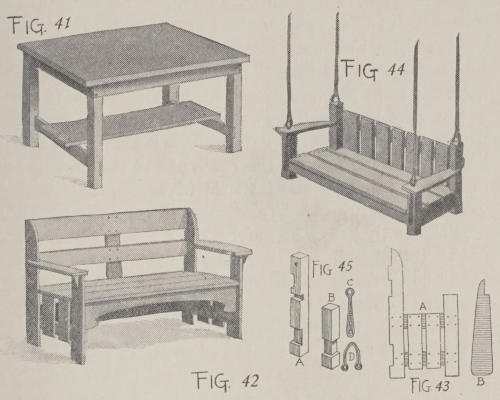

It is not so difficult as it may seem to make a good strong table, but care and perseverance must be exercised to obtain a satisfactory result. When constructing a table bear in mind that every joint should be made to fit accurately; otherwise it will quickly rack and become useless. The proportions and shape for a serviceable table are shown in Fig. 41. Only well-seasoned wood should be employed, and it should be free from knots or sappy places.

For the legs, obtain four sticks thirty-three inches long and two and a half inches square. From two sides, near the end of each stick, cut the wood away for five inches to a depth of seven-eighths of an inch, as shown (at the top) in Fig. 40 B. Now cut two boards five inches wide and forty-two inches long, and four more thirty inches long for the frame. Six inches from the uncut ends of the legs saw and chisel out laps, so that two of the thirty-inch lengths will fit into them, and with two long and two short boards unite the legs, thereby forming a frame thirty inches wide, forty-two inches long, and thirty-three inches high. An under-shelf[30] may be made twelve inches wide and long enough to extend two or three inches over the cross-strips.

The table top extends over the framework for three inches all around, and it is made of narrow tongue-and-grooved boards driven together and screwed down to the band around the top, formed by the thirty and forty-two-inch boards. To finish this top nicely it may be covered with felt, or with imitation leather, in old-red, green, or brown shades, caught under the edge and made fast with stout tacks.

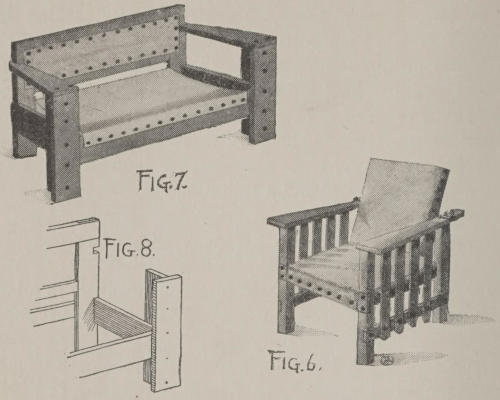

A comfortable settle (Fig. 42), for the piazza or yard, may be made from pine, white-wood, cypress, or almost any other wood that may be at hand.

It is fifty-four inches long, eighteen inches wide, and the seat is eighteen inches above the ground. The sides are made from strips three inches wide and seven-eighths of an inch thick, as shown in Fig. 43 A. The arms are twenty inches long, six inches broad at the front, and cut the shape shown in Fig. 43 B. The notches or laps cut in the rear posts are to let in the strips forming the back and lower brace.

The joints should be made with screws rather than nails, as they hold better and do not work loose. Small brackets support the arms at the front corner posts, and a batten at the middle strengthens the back of the settle. A close inspection of the drawings will show the joints clearly and indicate how the frame is put together. A few coats of paint will finish the wood nicely, or it may be stained and[31] varnished if the wood has a pretty grain. Cushions and a sofa-pillow or two will add to the comfort of this commodious seat.

Fig. 41. Fig. 42. Fig. 43. Fig. 44. Fig. 45.

A suspended settle (Fig. 44) is a convenient piece of piazza furniture, and not a difficult thing for the young carpenter to make.

The corner posts are two and a half inches square, and the boards used in its construction are seven-eighths of an inch thick and four inches wide. The seat is forty-two[32] inches long and eighteen inches wide, and the back is fifteen inches high from the seat. The arms are cut as shown in Fig. 43 B, and securely screwed to the corner posts. The frame-pieces supporting the seat-boards are let into the back and front posts, in which laps have been cut, as shown at Fig. 45 A and B. They should be securely fastened with flat-headed screws. Both the rail to which the backing-boards are attached and the rear ends of the arms are let into the corner post and fastened with screws.

The seat is suspended from the ceiling of the piazza on four chains that may be purchased at a hardware store or from a ship-chandler, or they may be made by a blacksmith from iron three-eighths of an inch in diameter. If it is not possible to obtain the chains, rope may be substituted, but it will not look or last so well.

Two yokes bolted to the top of the back posts and eye-straps for the front posts will anchor the chains securely to the settle. The yoke is shown at Fig. 45 C, and the eye-strap at Fig. 45 D. A bolt passed through the top of the rear posts and through the holes in the yoke will secure the latter firmly, and a nut will prevent it from slipping loose. Holes are made in the arms, and the eye-straps are passed down through them and attached to the front corner posts with screws, as shown in Fig. 44. The back of the settle is composed of boards four inches wide and placed an inch apart.

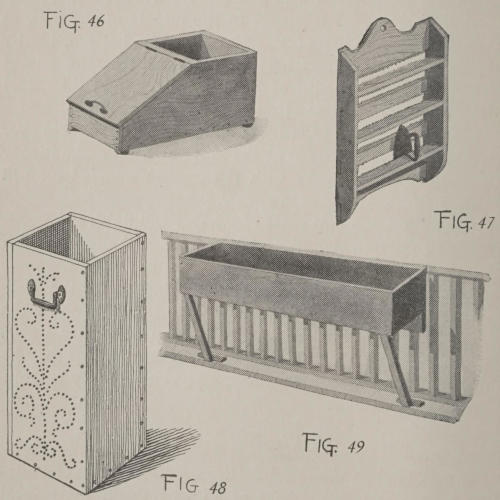

A combination box for coal and wood may be made from an ordinary shoe-box, the sides and one end being cut down[33] as shown in Fig. 46; but a more serviceable one is constructed of boards seven-eighths of an inch thick, planed on both sides, and with the joints securely glued and screwed.

The sides are twenty-six inches long and twelve inches high at the back. At the front they are but four inches high. A back-piece ten inches wide and twelve inches high is cut and fastened in place, and a front strip four inches high is also made fast with glue and long, slim screws.

A division-board is placed in the middle of the box, as indicated by the line of screw-heads, and a bottom, ten by twenty-four inches, is held in place with screws passed through the lower edge of the front, back, and sides, and into the edges of the bottom.

A lid the width of the box is hinged to a cross-strip over the partition. A handle at the lower end will make it easy to lift the lid. Blocks with the corners rounded off will serve as feet, one at each corner.

Thin stain and two coats of varnish will finish the wood-work on the outside. A coat or two of asphaltum varnish will be better for the inside.

Sticks of wood for the open fire or kindling for the grate fire may be kept in the square receptacle, while under the lid at least two bucketfuls of coal may be stowed away. If the fuel-holder is used only at the open fire, logs may be stood on end in the square box, and kindling may be kept in the covered half.

A rack of shelves to hold flat-irons may be made of white-wood or pine seven-eighths of an inch thick, the several[34] pieces being securely fastened together with screws. Two side-plates are cut four inches wide and thirty inches long. The tops are bevelled and the bottom of each piece is curved, as shown in Fig. 47.

Fig. 46. Fig. 47. Fig. 48. Fig. 49.

The shelves are two inches wide and eighteen inches long. They are spaced eight inches apart, having the front edge flush with the edge of the side-plates, and leaving a space[35] two inches wide from the rear edge to the wall. Wall-plates two inches wide are let into the rear edge of the side-plates two inches above the shelves. Against these the bottom of the irons will rest.

A top and a bottom board, cut as shown in the illustration, are to be attached to the wall-plates, and the complete rack of shelves should be fastened to the kitchen or laundry wall with stout screws set firmly into the studding.

Two coats of olive-green or brown paint will finish this holder nicely, or it may be painted any color to match the wood-work in the kitchen or laundry.

An umbrella-stand does not occupy much space, and it is a convenient receptacle for umbrellas, canes, ball-bats, and golf-clubs (Fig. 48).

To make one it will require four pieces of clear pine or white-wood thirty inches long, ten inches wide, and half an inch in thickness. There is also a bottom board nine and a half inches square and seven-eighths of an inch thick, to which the lower ends of the boards are to be screwed fast. A high, narrow box is to be formed of the boards, one side of each board being attached to the edge of the next one, as the illustration shows. Shellac or varnish will give the wood-work a pleasing finish, especially if it is white-wood, cypress, or spruce.

A design may be worked out on one side with large oval-headed hobnails painted black. These may be purchased at a shoemakers for a few cents a paper. The design should[36] first be drawn on thin brown paper and held on the wood with pins. The nails are driven along the lines of the ornament, but before they are hammered home, the paper should be torn away so that none of it is caught under the nail-heads.

A zinc tray six inches high, and made to fit in the bottom of the box, will hold the drippings from wet umbrellas. Rings soldered at the top edge of the tray will permit it to be removed for cleaning.

For growing plants and flowers that always look well around a piazza rail, the plant-box shown in Fig. 49 will be found useful. One or more boxes may be made from pine boards an inch thick and eight inches wide. The boxes should be six inches deep, outside measure, and they may be as long as desired to fill the spaces between the piazza posts.

Straight or box joints are made at the corners and fastened with screws. The inside of the boxes should be treated to several successive coats of asphaltum varnish to render them water-proof. Several small holes must be bored in the bottom of each box to drain off surplus moisture, and the boxes and supports may be painted a color to match the trimmings of the house.

To anchor the boxes, screw a batten to the balustrade, on which the inner edge of the box may rest. The outer edge is supported by means of braces attached firmly to the underside of the box and to the piazza floor, as shown in[37] the illustration. Two small brackets attached to the underside of the box and to the batten will hold the box in place and prevent it from slipping off the top of the batten.

The few objects shown and described in this chapter are, of course, but a small part of the things a wide-awake boy will think of and wish to make. The principles involved in these examples, however, will apply to scores of other things that may be constructed. Once these simpler forms of workmanship are mastered the young craftsman will go forward naturally to the higher exercise of his art. Carpentry is a fascinating occupation, and it is well worth while, since its results are of practical use and value.

A knowledge of drawing and modelling will be most helpful to the young carver, as then the outline of ornament can be readily drawn, while to carve objects from wood the art of modelling form is most desirable.

If the beginner possesses a knowledge of form acquired by drawing and modelling, the art of wood-carving may be readily and quickly mastered; but even if these advantages should be lacking, it is possible that considerable progress can be made by those who will follow the instructions given on these pages.

The most important feature of carving is the ability to sharpen and maintain the little tools, and when this is mastered, more than half the difficulty has been overcome. The dexterity to handle, with a firm and sure hand, the various chisels and gouges comes, of course, with practice only.

It is better to begin with a soft wood. Pine, poplar, button-wood, cypress, or red woods are all of close grain and are easy to work. The harder woods, and those with a very open grain—such as chestnut, ash, and oak—should[39] not be carved until the first principles are learned in the softer woods.

Carving takes time, and it is not an art that can be quickly mastered, unless it be the chip-and-line variety. But this last can hardly be compared to the more beautiful relief-carving, with its well-modelled form and undercutting.

A boy may learn the first principles of carving, using only his small, flat carpenter’s chisels and gouges; but for more advanced work he will need the regular carving-chisels. These latter are sharpened on both sides, while the carpenter’s chisels are ground on one side only. Nevertheless, some very good work has been done by boys who had nothing better than a small gouge, a flat chisel, and a penknife. The true artist can work in any material and with the most indifferent of implements.

At the start a numerous assortment of tools will not be necessary, as the flat work and chip-carving will naturally be the first department of the art to be taken up by the young carver.

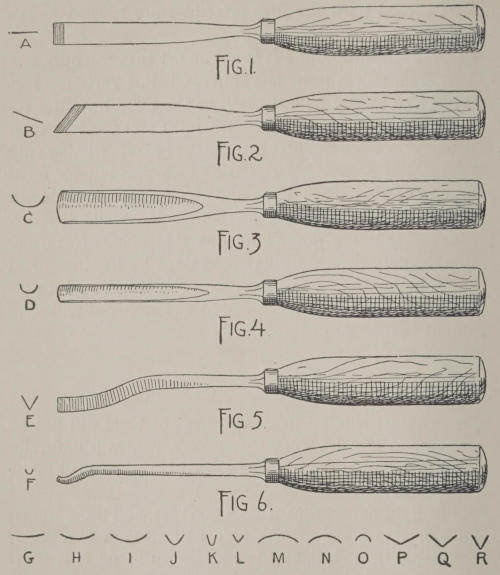

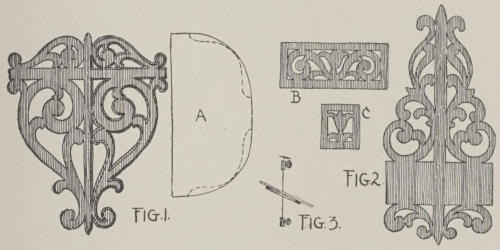

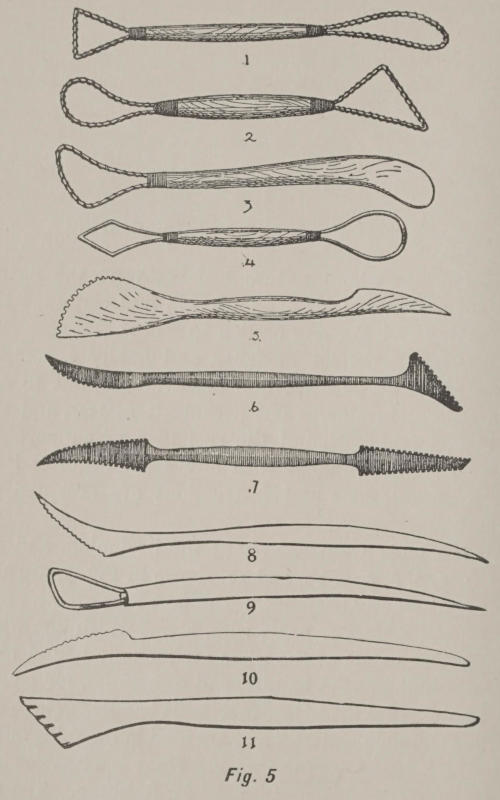

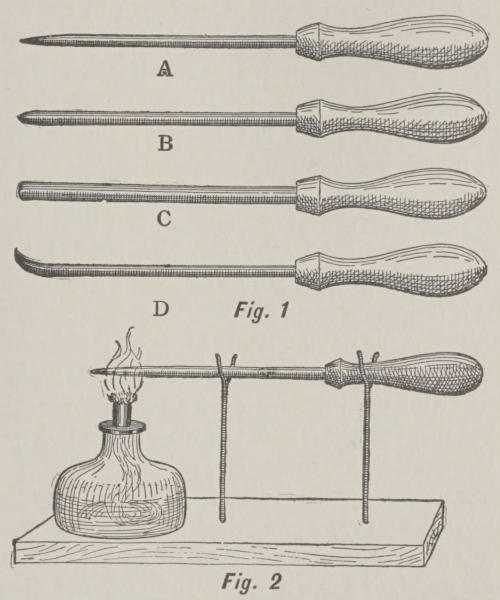

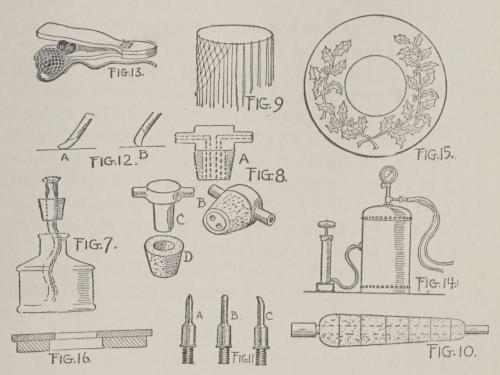

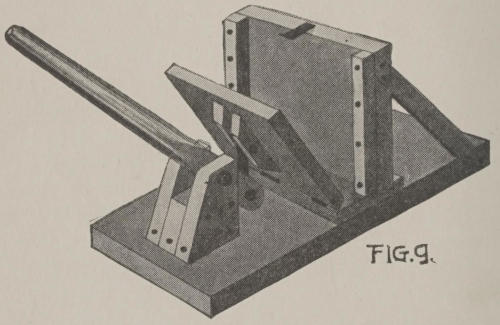

Six or eight chisels constitute a good set, and those shown from Fig. 1 to 6 will answer very well. Fig. 1 is a plain, flat chisel with a straight edge, as shown at A; it is commonly called a firmer. Fig. 2 is also a flat tool, but possessing an angle or oblique edge; it is commonly called a skew-firmer. Figs. 3 and 4 are gouges. Fig. 5 is a V gouge, and Fig. 6 is a grounder. G, H, I, J, and K are gouges of various circles. L is an angle, or V, gouge. M, N,[40] and O are gouges of various curves, and P, Q, and R are V gouges of various widths and angles. These last are used for furrows, chip-carving, and lining.

A Fig. 1.

B Fig. 2.

C Fig. 3.

D Fig. 4.

E Fig. 5.

F Fig. 6.

G H I J K L M N O P Q R

A flat felt or denim case should be made for the tools, so[41] that they may be kept in good order. It is made of two strips of the goods, one wider than the other. Two edges are brought together and sewed, and lines of stitching form pockets for the chisels. The flap left by the wider strip of goods is folded over the chisel ends, and the pockets containing the tools may be rolled up and tied with tape-strings. When opened it will appear as shown in Fig. 7. The edges of chisels kept in this manner are insured against injury and rust, since the case protects them from atmospheric moisture.

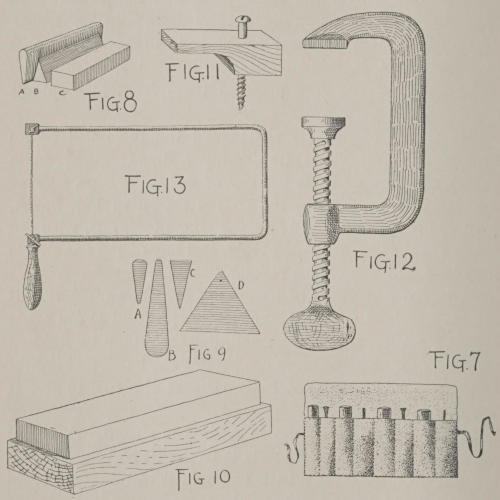

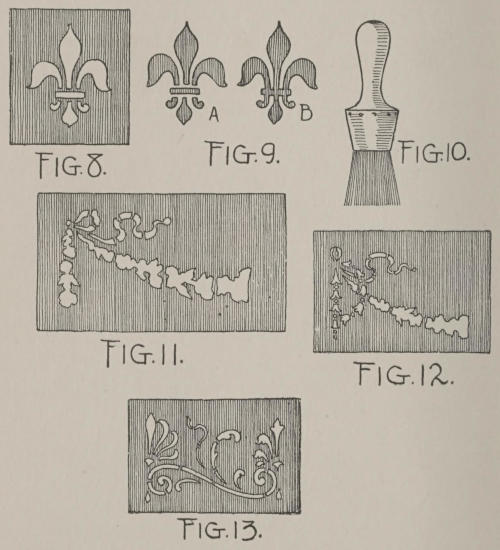

The stones needed for sharpening the tools will be an ordinary flat oil-stone (preferably a fine-grained India stone), and two or three Turkey or Arkansas slips, four or five inches long, having the shapes shown in Fig. 8. A, with the rounded edges, is for the gouge tools; B, with the sharp edges, is for V-shaped tools; and any of the flat chisels may be sharpened on the regular oil-stone, C.

In Fig. 9 end views of some slips are shown. A and B are round-edged slips for gouge-chisels; C and D are angle stones for V chisels; while small, flat tools may be finished on the sides. These stones are held in the hand, and lightly but firmly rubbed against both surfaces of a tool to give it the fine cutting edge.

In Fig. 10 an oil-stone in a case is shown. A boxed cover fits over it and protects it from grit and dust. This is important, for often a little gritty dust will do more harm to the edge of a fine tool than the stone can do it good.

The other tools necessary to complete the kit will be several clamps, similar to those shown in Figs. 11 and 12, and a fret-saw (Fig. 13). If you happen to possess a bracket-machine[42] or jig-saw the fret-saw will not be necessary. A glue-pot will also be found useful.

Fig. 7. Fig. 8. Fig. 9. Fig. 10. Fig. 11. Fig. 12. Fig. 13.

The first essential to good, clean cutting is that the tools shall be absolutely sharp and in a workmanlike condition. It is often the case that an amateur’s tools are in such a state that no professional carver could produce satisfactory results with them. And yet the variety of carving tools is[43] so limited that if the difficulties of sharpening a firmer and gouge are mastered the task is practically ended.

If the tools should be unusually dull they must first be ground on a grindstone, and as carvers’ tools are sharpened on both sides, they must be ground on both sides. The firmers may be sharpened on the oil-stone laid flat on the bench, but the gouges must be held in the hand, in order to sharpen the inside curve with a slip. The outer curve can be sharpened on the flat oil-stone, or held in the hand and dressed with the flat side of a slip. Great care must be taken to give the tools a finished and smooth edge. When they have reached the proper degree of sharpness it will be an easy matter to cut across the grain of white pine, leaving a furrow that is entirely smooth and almost polished.

In the use of the oil-stone and slips, neat’s-foot oil, or a good, thin machine oil, should be employed. Astral oil is too thin, but the oil sold in small bottles for sewing-machines or bicycles will answer every purpose. Water should not be used, as it would spoil the stones, and not produce the sharp edge on the tools.

The finest stones are the best for use, and although they take longer to give the keen edge required, they will be found the most satisfactory in the end. Avoid grit and dust on the stones, and before using them they should be wiped off with an oiled rag. The beginner must not consider any pains too great to make himself thorough master of the tools, and to keep a perfect edge on all of them.

The tools being in proper condition, the next step is to acquire a knowledge of the best methods of handling them.[44] It will require some time and practice to become thoroughly familiar with the manner in which tools are used, and, if it is possible, it would be well to watch some carver at work.

The chisels should always be held with one hand on the handle, with two fingers of the other hand near the edge of the tool. This is to give sufficient pressure at the end to keep it down to the wood, while the hand on the handle gives the necessary push to make the tool cut.

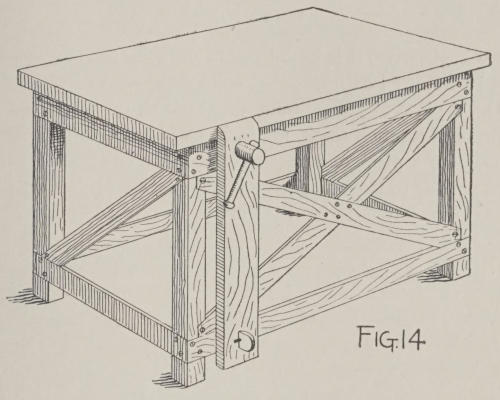

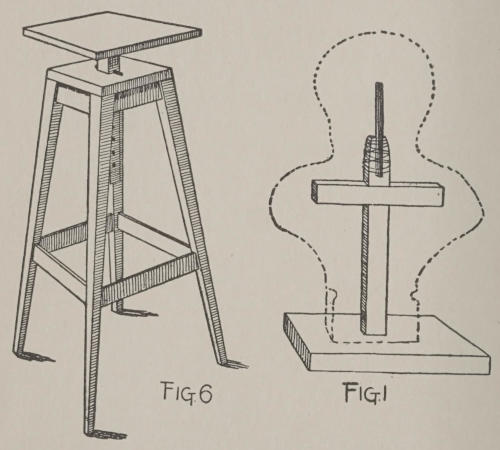

A carver’s bench is a necessity for the young craftsman, but if it is not possible to get one, a heavy, wooden-top kitchen table will answer almost as well. The proper kind of a bench gives greater facility for working, since it is more solid and the height is better than that of an ordinary table. Any boy who is handy with tools can make a bench in a short time of pine or white wood, the top being of hard-wood. If the joiner-work is not too difficult to carry out, it would be better to make the legs and braces of hard-wood also, to lend weight and solidity to the table.

Fig. 14.

The wood should be free from knots and sappy places, and as heavy as it is possible to get it, so as to make a really substantial bench. The top should measure four feet long and thirty inches wide, and not less than one inch and a half in thickness. The framework must be well made, and the corner-posts and braces securely fastened with lap-joints, glue, and screws. The top of the bench should be thirty-nine inches high, and to one side of the bench a carpenter’s[45] vise may be attached, as shown in Fig. 14. The jaw of the vise is seven inches wide, one and an eighth inches thick, and thirty-four inches long. It is hung as described for the carpenter’s bench (see Carpentry, Chapter I.). A wood or steel screw may be purchased at a hardware store, and set near the top and into the solid apron side-rail. The posts are four inches thick, and the cross-pieces and rails should be of seven-eighth-inch hard-wood four inches wide. The top overhangs the framework two inches all around, thus forming a ledge, to which the plates of wood or panels may be bound with the clamps and bench-screws. Where a clamp cannot be used, a cleat, as shown in Fig. 11, is screwed fast to the top of the table, and the projecting ear catches the edge of the wood and holds it securely.

A coat of varnish or paint on the legs and braces will finish this bench nicely, and it will then be ready for the young workman’s use.

To begin with, it is best to work on a simple pattern that can be followed easily.

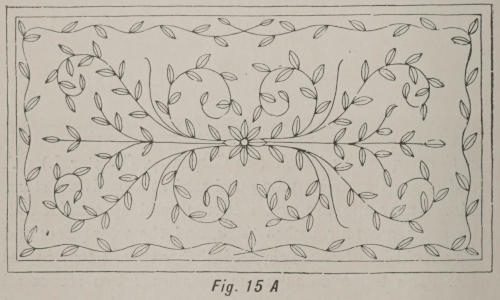

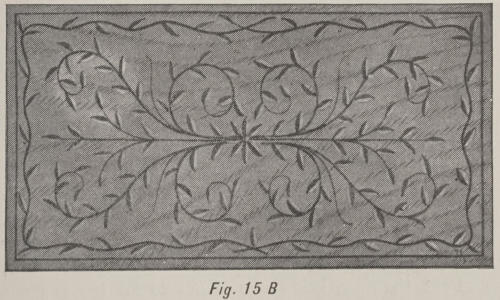

Fig. 15 A.

Get a piece of yellow pine, white-wood, or cypress seven-eighths of an inch thick, six inches wide, and twelve inches long. On a piece of smooth paper draw one-half of a pattern similar to the one shown in Fig. 15 A; or you may use any other simple design that is free in line and open in the ornament. Upon the wood lay a sheet of transfer-paper, with the black surface down, and on top of the transfer-sheet the paper bearing the design. Go over all the lines with a hard lead-pencil, bearing down firmly on the point,[47] so that the lines will be transferred to the wood. Turn the design around and repeat the drawing, so that the wood will bear the complete pattern. Clamp the wood to one side or corner of the bench with three or four clamps. Do not screw the clamps directly on the wood, but place between the jaw and the wood a piece of heavy card-board, or another piece of thin wood, to prevent the clamps from bruising the surface of the panel.

First, with a small V, or gouge-chisel, cut the lines; after that the leaves, using a flat, or spade, chisel. Two curved incisions will shape out the leaf, and the angle through the centre describes the main vein. The chipping may be shallow or deep, as a matter of choice, but more effect may be had by cutting fairly deep.

Fig. 15 B.

The finished result will appear as shown in the illustration of the chip-carved panel (Fig. 15 B). For light ornamenting or drawer-panels, fancy boxes, and picture-frames,[48] this form of carving may be made both pleasing and effective. Moreover, its mastery leads naturally to the more artistic relief-carving.

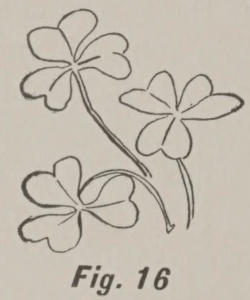

Fig. 16.

Fig. 17.

Get one of the little nickel-plated clocks (sold at sixty cents and upwards). Lay it down on a smooth piece of soft wood—pine or cedar—about seven by eight inches. Mark around it closely with a lead-pencil, and cut out the circular opening with your knife. If you happen to have a fret-saw or suitable tools, you can make it of hard-wood. Smooth nicely with sand-paper. The clock must fit closely into the opening. You will find Fig. 16 very easy to do. Cut out the lines, being careful not to let the tool slip[49] when cutting with the grain. Dilute the walnut stain with turpentine, and paint the design inside the lines; the grooves prevent the color spreading. Let it dry. The next day, with a wad of cotton or piece of canton flannel, rub on some varnish. Soft wood absorbs it very rapidly at first until the pores are filled. When quite dry, sand-paper nicely. Then rub again with varnish, a little at a time. Keep raw linseed-oil near you in a cup; dip one finger of your left hand in this when the work becomes sticky, and apply to the pad; it helps to spread the varnish. Rub briskly with a circular motion. The varnish will dry quickly, when it must have a final polish; this brings out the beauty of the grain. If carefully done, your work will resemble inlaying.

The daisy design (Fig. 17) is charming when finished, and has the additional merit of being easy. Cut the daisy form from a visiting-card, and mark around it. Stain the centre much darker than the petals.

Table-tops, jewel-boxes, calendar frames, chairs, etc., may be purchased already polished, and outlined in some dainty pattern. A finer tool (No. 11, 1/64) comes for this kind of work. Of course it cannot be stained, but if desired the background may be stamped with a star-pointed “marker” to give the design prominence.

These patterns may be adapted for the decoration of glove-boxes, bread-plates, knife-boxes, stools, blotting-books, card-cases, match-boxes, music-portfolios, and many[50] other things, which will sell well at fancy fairs, or be highly appreciated as presents.

Relief-carving differs from the chip work in that the ornament is raised instead of being cut in. Solid relief-carving, such as appears on panels, box-covers, and furniture, is produced either by cutting the background away or by carving the ornament separately and then gluing it onto the surface of the article to be decorated. Of course, this latter process is only a makeshift, and the first method is the really artistic one.

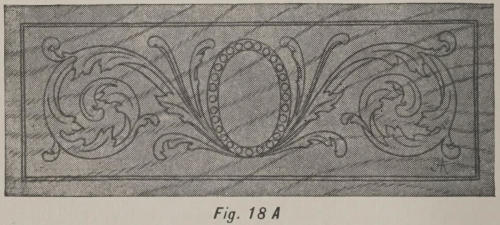

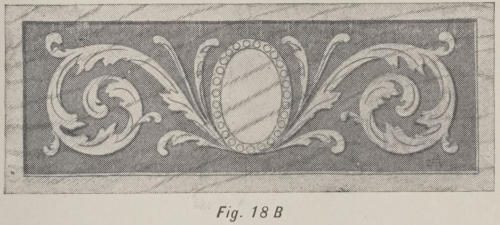

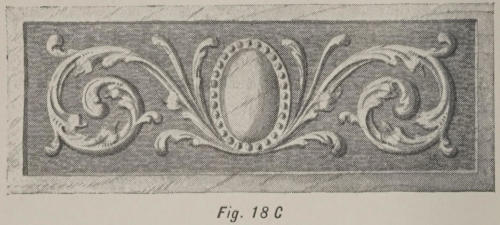

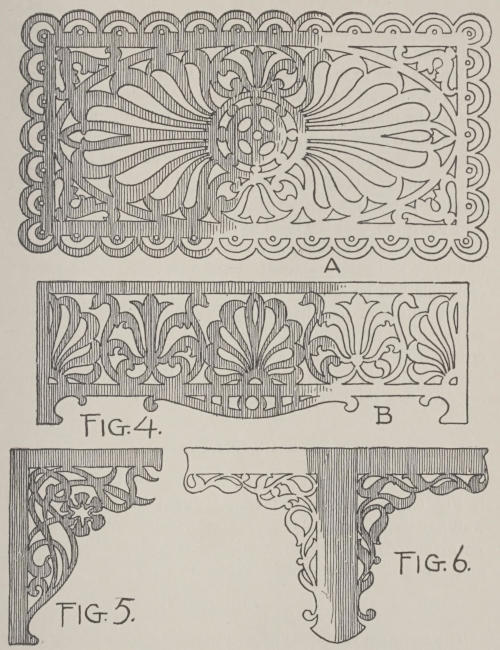

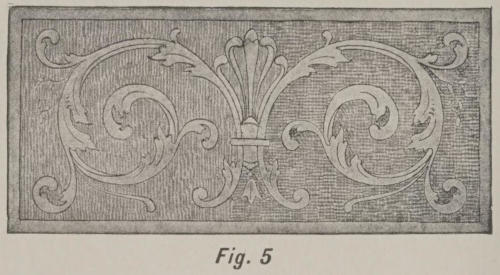

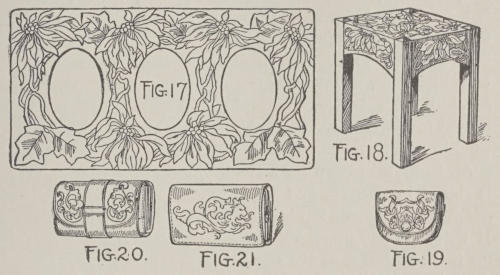

It is best to begin with something simple and then go on to the more complicated forms of ornamental work. A neat pattern for a long panel is shown in Fig. 18 A. This panel is twelve inches long and four and a half inches wide.

Fig. 18 A.

On a smooth piece of paper draw one-half of the design and transfer it to the wood, as described for the chip-carved panel. Clamp the wood to a corner of the bench and, with[51] a small wooden mallet and both firmer and gouge-chisels, cut down on the lines and into the face of the wood. Then, with the gouges and grounding-tool, cut away the background to a depth of one-eighth of an inch or more, until a result is obtained similar to that shown in Fig. 18 B. The entire design and edge of the panel will then be in relief, but its surface will be flat and consequently devoid of artistic feeling. With the flat and extra flat gouge-chisels begin to carve some life into the ornament. A little practice will soon enable the young craftsman to observe which parts should be high and which should be low. The intermediate surfaces should be left neutral, or between high and low relief. This finishing process depends for its effect upon the good taste and feeling of the craftsman; it is the quality that gives artistic beauty and meaning to the work. The panel, when completed, should have the appearance shown in Fig. 18 C.

Fig. 18 B.

As already stated, the general effect of relief-carving may be also obtained through the “applied” method, a simpler[52] and less tedious process, but neither so artistic nor so substantial.

Fig. 18 C.

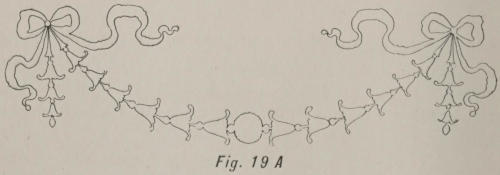

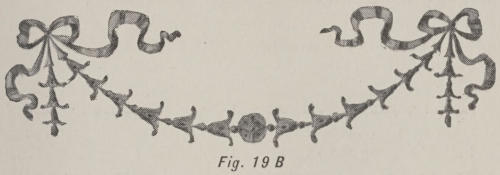

Fig. 19 A.

The design is transferred to a thin piece of wood and cut out with a fret or jig saw. Fig. 19 A shows a suitable pattern for this class of work. The pieces are then glued in position on a thick piece of wood, and the “feeling” carved in after the fashion already indicated. This “applied” carving may be used on the panels of small drawers, cabinets, and boxes of various sizes and shapes. The inventive[53] boy will be able to design patterns for himself, or they may be cheaply bought. Fig. 19 B shows the effect of the finished work.

Fig. 19 B.

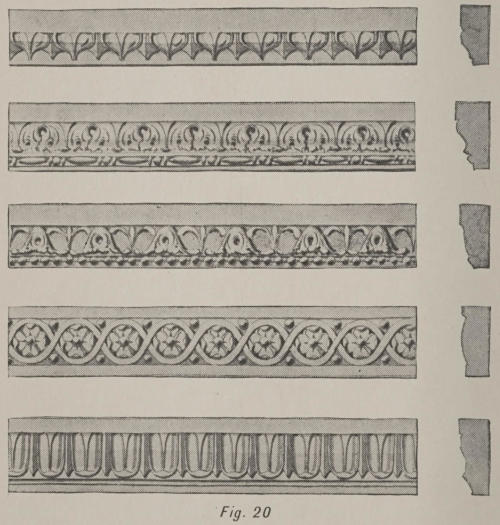

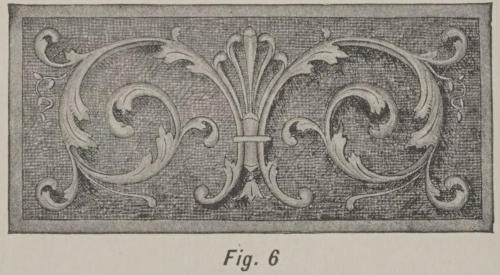

In Fig. 20 some designs are given for carved mouldings, and at the side, end views are shown.

Plain mouldings of various shapes may also be bought at a mill, or from a carpenter, and may be given “life” with a little care and work. Both hard and soft wood mouldings are available, but at first the softer woods will be found the easier to work.

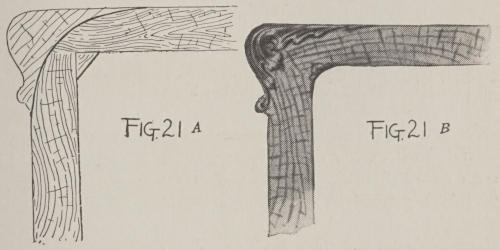

A plain corner on a wooden picture-frame may be built up with blocks of wood glued on as shown in Fig. 21 A. When carved this piece will have the appearance of the finished corner shown in Fig. 21 B. The arms of chairs, corners of furniture, and the like may be treated in this same manner.

When flat and relief carving have been mastered, it would be well to attempt something in figure and free-hand work, such as animals, fruit, or heads. But it will take a good[54] deal of practice on the simple and conventional forms before the amateur will feel himself competent for the more advanced art. As improvement in the flat work is noticed, the ornament may be “undercut” to give it richness and boldness.

Fig. 20.

To finish wood in any desired color, stains may be purchased[55] at a paint or hardware shop. Over the stained surface, when dry, several thin coats of hard-oil finish or furniture varnish should be applied. The back and edges of a carved panel must always be painted to protect them from moisture and dampness; warping and splitting are thereby avoided. Some pieces of carving need only a coating of raw linseed-oil, while others may be treated to a wax finish composed of beeswax cut in turpentine, rubbed in with a cloth, and polished off. Another method of darkening oak (before it is varnished) is to expose it to the fumes of ammonia, or to paint on liquid ammonia, with a brush, until the desired antique shade is obtained. The staining process, however, is preferable.

Fig. 21 A. Fig. 21 B.

Nearly every boy has had, at one time or another, a desire to make scroll-brackets, fretwork-boxes, and filigree wood-work of various sorts. The art is naturally affiliated with other decorative processes in wood-working, such as wood-turning, carving, and marquetry, or the art of inlaying woods. Both fretwork and wood-turning are very old crafts, and were practised by the ancient Egyptians, specimens of their work being still extant.

A great deal of amusement and pleasure may be had in the possession of a scroll-saw, or “bracket machine,” as it was commonly known among boys some years ago. And first, as to the implements required.

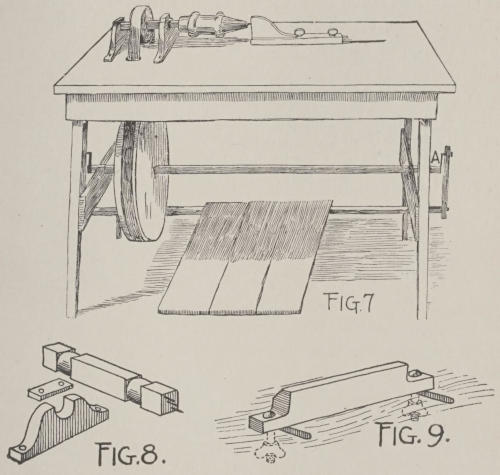

To those who can go to the dealer and pay for just what their fancy dictates, there is no trouble to procure all the tools that may be needed for the finest work; but others who cannot afford this luxury may get along nicely with a very small outlay. In fact, in nearly every instance known to the writer where the amateur has really rigged up his[57] own machine, he has become master of the art sooner. A number of years ago the writer, then a school-boy, transformed an old sewing-machine table into a scroll-saw and lathe, and to-day this homely old stand and crudely put together machine does as good work, with as little effort, as the finest and most expensive outfit. This machine, all complete, with the drilling attachment, cost: old machine, one dollar; dozen saws, assorted, twenty-five cents; new material, rivets, etc., sixty-five cents; drills (still in use), fifteen cents; total, two dollars and five cents.

This money was saved from building fires and taking up ashes, and the first time the saw was run—one cold, stormy day in late November—there was cut up material which, when put together and sold (playmates and school-fellows being the customers), amounted to over three dollars in cash, besides a few pocket-knives, bits of rare wood, and the like that were taken in exchange.

Making a fine scroll-saw from a sewing-machine is of itself an easy matter. The balance-wheels should be retained, in order that all back lash can be easily overcome. The two arms holding the saw are to be geared from some wheel in the rear or connected with a belt. If the wrist-pin (the crank, or pitman wrist) gives too long a motion, it can be easily taken up by either drilling another hole nearer the centre or using a bent crank-pin. In any event the cut should not be over one inch.

Another method of shortening the stroke (and a very good one if the means of making the other changes are not at hand) is by changing the bearing of the arm. The nearer the saw the shorter the stroke. The clamp-screws holding[58] the saws should be adjustable, so that either a long or a short saw-blade may be used. Those who break their blades (and there are none who do not) will find great economy in using adjustable clamps, as the short pieces can be used for sawing thin stuff, veneers, and the like. The best kind of clamp is provided with a slit to receive the blade and a set-screw for tightening.

The tools necessary for hand-sawing are very simple and inexpensive, consisting of a wooden saw-frame, one dollar; dozen saw-blades, twenty cents; one clamp-screw, twenty-five cents; drill and stock, fifty cents; total, one dollar and ninety-five cents.

In selecting saw-blades be careful to buy only those with sharp and regular-cut teeth. Saws are graded by number for hand-sawing. Numbers 0 and 1 are the best sizes, unless for very delicate work, when finer ones should be used. The larger blades have coarse teeth, which are liable to catch in the work and tear it. Since, at the best, the motion of the hand-saw is jerky, not nearly so nice work can be done as with the treadle-saw, which has an even, steady gait.

For all open-work it is necessary to have something to punch holes, so that a start may be made on the inside. Many use an ordinary brad-awl, but this is liable to split the wood. Besides, it is not possible to punch a hole so smooth and nice as it can be drilled or bored; hence, a drill is included in the list, and it will be found a very handy tool for either hand or treadle saws. The most serviceable article of this kind is the small German drill-stock, that can be bought with six drill-points, assorted sizes, for fifty[59] cents, or the small hand-drills, with side wheel and handle, and provided with a small chuck to clutch the drill.

From what I have said, it should not be inferred that any objections are made to any of the beautiful little machines now to be bought at moderate cost. By all means, when the expense can be afforded, these should be used. The good ones will do the most delicate work, can be run with great ease, and will cut from eight to twenty pieces at a time, according to the thickness of the wood, leaving the edges of the work perfectly smooth. In using treadle-machines, insert the saw-blades with the teeth pointing downward and towards the front of the machine, and guide the wood easily with the fingers, with the wrists resting firmly on the table, being careful not to feed too fast or crowd against the saw sideways. Otherwise the blades will be heated and broken, and they will wear away the little wooden button set at the centre of the plate to prevent the saw from touching the metal work-table.

Most boys know how to run a scroll-saw, or think they do, yet a few practical hints should not come amiss.

To begin with, the machine should be well oiled, all nuts, screws, and bolts turned up tight, and the belts adjusted at sufficient tension to run at a high rate of speed without slipping. Many machines, even in large mills, are groaning and filing out their journals and bearings simply because the belts are too tight. One of the first principles to be mastered in applied mechanics is that of power transmission,[60] and right here the young workman has the best of opportunities to solve, in a measure, a great mechanical problem—namely, a belt tight enough to drive the machine and do the work, and loose enough to run easy and cause no unnecessary friction or wear on the journals and boxings.

For your first practice take some cigar-box wood (of which a good stock should be kept), and trace upon the dark sides a series of angles and curved lines. Never, under any circumstances, begin sawing without a tracing, or a pattern of some kind, to saw to, for now is the time to cultivate habits of accuracy. With no design or objective-point, nothing but a bit of useless board will result; besides, you will form a habit of working without a guide, a habit that has made more poor artisans than the love of idleness and bad company. Lay the wood on the rest, or plate, and see that it lies solidly. If it shakes, the wood is uneven and should be straightened, for no one can saw a warped board and make accurate work; besides, it is impossible to work in such wood without breaking the saws. The wood being level, hold it down with the left hand, fasten securely a No. 1 blade in the frame, and begin sawing, being careful to keep the motion very high and feeding slowly, sawing out the tracing lines, or keeping close to one side of them. If an ordinary hand-frame is used, work it firmly in one direction, keeping the blade perpendicular, and turning the wood so that the saw may follow the pattern.

After you have thoroughly learned the motion of the machine, the cutting of the saw, feeding, etc., try sawing a straight line, being careful not to push or crowd the blade sideways, as this will not only make the lines crooked, but[61] will heat and ruin the blades, if it does not break them. When you have become an adept in following a straight line, and cutting the lines of a curve accurately, mark out several Vs and squares. To saw a V begin at the upper end and saw down to the point; now back the saw out, and saw from the other end down to the same point. If the line is carefully followed, this will insure a sharp, clean-cut angle. To cut out a square hole, saw down to the angle, then work the blade up and down in one place rapidly until it becomes loose; then turn the wood at right angles and saw carefully along the line to the other corner, when the operation may be repeated. Just as soon as you can saw straight and curved lines true to tracings, it is safe to begin good work with little if any fear of spoiling lumber or breaking an undue number of saws.