Title: Mr. Arnold: A romance of the Revolution

Author: Francis Lynde

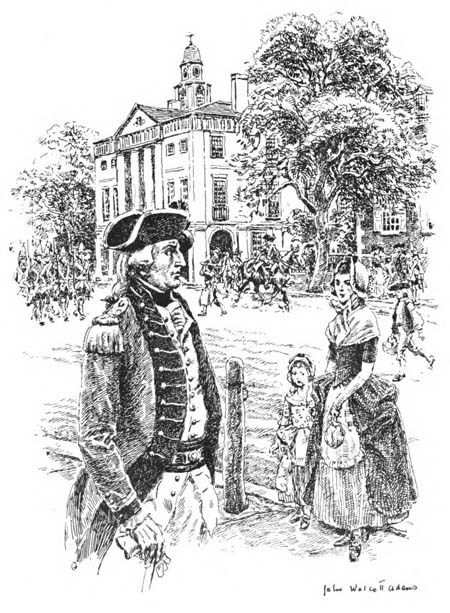

Illustrator: John Wolcott Adams

Release date: January 21, 2023 [eBook #69849]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1923

Credits: D A Alexander, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

“Mais j’y suis, et, mes bons

camarades, par tous les dieux,

j’y reste!”

CHARLES K. JOHNSTON.

MR. ARNOLD

A ROMANCE OF THE REVOLUTION

By

FRANCIS LYNDE

Author of

The Grafters, The Master of Appleby,

The Quickening, Etc.

Frontispiece by

John Wolcott Adams

INDIANAPOLIS

THE BOBBS-MERRILL COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1923

By The Bobbs-Merrill Company

Printed in the United States of America

PRESS OF

BRAUNWORTH & CO.

BOOK MANUFACTURERS

BROOKLYN, N. Y.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | How We Drank a Toast | 1 |

| II | A Voice in the Night | 13 |

| III | In Which I Shed My Rank | 32 |

| IV | How My Rank Was Regained | 50 |

| V | A Kiss and a Man’s Life | 73 |

| VI | Dark Night | 85 |

| VII | And an Unblest Dawn | 93 |

| VIII | A Walk up Gallows Hill | 104 |

| IX | In Which I Pay a Duty Call | 114 |

| X | In Which a Wall Has Ears | 131 |

| XI | Out of the Nettle, Danger | 146 |

| XII | How the Hook Was Baited | 163 |

| XIII | How a Fish Was Hooked and Lost | 176 |

| XIV | A Cask of Bitters | 192 |

| XV | In the Fog | 205 |

| XVI | The Cup of Tantalus | 209 |

| XVII | Masked Batteries | 221 |

| XVIII | In Which the Wind Keeps Revels | 239 |

| XIX | Mine Honor’s Honor | 256 |

| XX | Traitors All | 277 |

| XXI | The Drumhead Court | 296 |

| XXII | In the Powder-Room | 307 |

| XXIII | Open Field and Running Flood | 329 |

MR. ARNOLD

MR. ARNOLD

IF THERE were nothing else to recall the day and date, December 14, 1780, I should still be able to name it because it chanced to be my twenty-second birthday, and Jack Pettus, of the Virginia Hundreds, and I were breaking a bottle of wine in honor of it in the bar of old Dirck van Ditteraick’s pot-house tavern at Nyack.

The afternoon was cold and gray and dismal. The wine was prodigiously bad; and the tavern bar, lighted by a couple of guttering candles in wall sconces, was a reeking kennel. I was hand-blistered from my long pull down the river from Teller’s Point; and Jack, who had ridden the four miles from General Washington’s headquarters at Tappan to keep the mild birthday wassail with me, was in a mood bitter enough to kill whatever joy the anniversary might be supposed to hold for both or either of us.

“I’m telling you, Dick, we’re miles deeper in the ditch than we’ve been any year since this cursed war began!” he summed up gloomily, when we had chafed[2] in sour impatience, as all men did, over the sorry condition of our rag-tag, starving patriot army. “Four months ago we had eight thousand men fronting Sir Henry Clinton here in the Highlands; to-day we couldn’t muster half that number. Where are all the skulkers?”

“Gone home to get something to eat,” I laughed. “We need to hang a few commissary quartermasters, Jack.”

“It isn’t all in the commissary,” he contended, “though I grant you there are empty bellies enough among us. But above the belly-pinching, it’s the example set by that thrice-accursed traitor, Arnold, in his going over to the enemy. Not a night passes now but some troop breaks the number of its mess by losing a man or two to the southward road.”

“But not Baylor’s,” I qualified. Pettus was a lieutenant in Major Henry Lee’s Light Horse Legion, and I a captain in Baylor’s Horse, at the moment posted at Salem on scouting duty.

“Our record is broken,” he confessed, staring soberly at his wine-cup. “Some time back, John Champe, our sergeant-major, took the road at midnight, beat down the vidette with the flat of his sword, and galloped off, with Middleton and his troop in hot pursuit. They rode till dawn, and were in good time to see Champe take to the river at Bergen and swim out to a king’s ship anchored off-shore.”

“We of Baylor’s are whole yet, thank God, save for the potting of a man or so now and then by the Cow-boys,” I boasted.

[3]“The Light Horse is stirred to the very camp-followers by Champe’s desertion,” Pettus went on, with growing bitterness. “It’s the honor of the South.” Then, Van Ditteraick’s vile vintage getting suddenly into his blood, he clapped bottle to cup again and sprang to his feet. “A toast!” he cried. “Fill up and drink with me to the honor of Virginia!”

“Always and anywhere, and in any pot-liquor, however bad,” said I; and when he let me have the bottle I filled the cup, and was glad to note that my hand was still steady.

“Now, then—standing, man, standing!” he bellowed, waving me up: “Here’s to the loyalty of the Old Dominion, and may the next Virginian who smirches it, though that man be you or I, Dick Page, live to lose the woman he loves, and then die by inches on a gibbet, with crows to pluck his eyes out!”

If I smiled in my cup it was at the naming of a woman in the curse, and not at Jack’s extravagance, nor at the savage sentiment. For we of Baylor’s had privately agreed and sworn to flay alive and burn the first man caught deserting the colors, no matter what his name should be nor how high his standing.

After drinking his terrible toast, Jack dropped into his chair and relapsed into silence; whereat I had a chance to look about me, and to gather myself for the question which, more than the mere drinking of a birthday bottle with Pettus, had brought me to the point of asking Colonel Baylor’s leave to ride and row from our camp at Salem to Nyack on this raw December day.

[4]“Jack,” I began, when the silence had sufficed, “are you sober enough to thread a needle for me in that matter of Captain Seytoun’s?”

“Try me and see, Dick,” he said promptly, sitting up and pushing the bottle aside.

“Word came to me yesterday, through Martin, the orderly who rode with despatches from the commander-in-chief to Colonel Baylor, that Seytoun had been talking again,” I went on, trying to keep the rage tremor out of my voice. “Martin had it that he had been revamping that old lie about the Pages and the ship-load of loose-wives sent over to Virginia in Charles II’s time. Is this true?”

Pettus shook his head, not in denial, I made sure, but in deprecation.

“This is no time to be stirring up past and gone private quarrels, Dick,” he said. “The good cause needs every sword it has; Bully Seytoun’s, as well as yours.”

“You’re not answering my question, Jack,” I retorted, fixing him with hot eyes. “I heard this of Captain Seytoun, and more: it was said that he cursed me openly, and that he dragged in the name of Mistress Beatrix Leigh, swearing that he would take her from me if I were thrice wedded to her.”

“A mere pot-house tongue-loosing when he was in liquor, Dick,” said my friend placably. “It was here, in this very den of Van Ditteraick’s.”

“Then you heard him?”

Pettus nodded. “And can testify to his befuddling.”

[5]“He shall answer for it some day, drunk or sober,” I vowed; and then I stood my errand fairly upon its rightful feet. “That is what fetched me to Nyack to-day, Jack. There must be some accommodation brought about with Captain Seytoun. I am not made of sheepskin like a drumhead—to be beaten upon forever without breaking.”

“‘Accommodation’?” Jack queried, with a lip-curl that I did not like.

“Yes. You are near to Major Lee, who is your very good friend, Jack; a word from you to the major, and from the major to Captain Seytoun——”

Pettus never knew what it cost me to say this, or he would not have countered upon me so fiercely.

“Good heavens, Dick Page! Has it come to this?——are you asking me to go roundabout to Seytoun to cry ‘Enough!’ for you? Where is your Virginia breeding, man!—or have you lost it campaigning in this cursed country of the flat-footed Dutch?”

I smiled. This, you may notice, was my cool-blood Jack Pettus, who, but a moment earlier, had been telling me that the present was no time to be stirring up private quarrels. But my word was passed—as I knew only too well, and as he could not know.

“I can’t fight Captain Seytoun, Jack; but neither can I brook his endless tongue-lashing,” I said, moodily enough, no doubt.

“‘Can’t’ is no gentleman’s word, Dick,” he insisted, still fiercely emphatic upon the point of honor.

“But just now you said that private quarrels——”

“I was drunk then, on this vinegar stuff of Van[6] Ditteraick’s; but I’m sober now. This thing that you propose is simply impossible, Dick. Can’t you see that it is?”

I must confess that I did see it as a miserable choice between two evils. But my chance to win the love of Mistress Beatrix Leigh had not been lightly earned, and though it was but a chance, I dared not throw it away.

“But if I have a good reason—the best of reasons—for not fighting Captain Seytoun at the present time,” I began.

Pettus flung up his hand impatiently.

“You are the judge of that; also of how far a gentleman from Virginia may go in the matter of eating dirt at his enemy’s hands. But don’t ask me to carry your apologies for his insults to this bully-ragging captain, Dick. I’m your friend.”

I made the sign of acquiescence. The war would end, one day, and then I should be free of my fetterings. Since our legion had been sent across the river, I had had no opportunity of collision with Captain Seytoun—the opportunity which had recurred daily while the two legions, Baylor’s and Major Lee’s, had been quartered together below Tappan. If the gossiping orderly had only kept a still tongue in his head—but he had not, and here I was at Nyack, on Seytoun’s side of the river, with my finger in my mouth, like a schoolboy caught putting bent pins on the master’s seat, mad to have it out once for all with my tormentor, but more eager still to get away with a whole conscience.

[7]Matters were at this most exasperating poising-point, with the two of us sitting on opposite sides of the slab drinking-table and glowering at the half-emptied wine-bottle, when the choice was suddenly taken from me. There was a medley of hoof-clinkings on the stones of the inn yard, a great creaking of saddle leather and clanking of accouterments to go with the dismounting, and some four or five officers of Lee’s Horse tramped into Van Ditteraick’s bar and called for refreshment.

Being fathoms deep in an ugly mood, I did not look up until I felt Jack calling me with his eyes. Then I saw that one of the in-comers was none other than this same Captain Howard Seytoun; that his red face and pig-like eyes spoke of other tavern visits earlier in the day; and that the ostentatious turning of his back upon me was merely the insulting preface to what should follow.

What did follow gave me no time to consider. As if he were resuming a conversation that moment interrupted, Seytoun turned to the man next at hand—it was Cardrigg, of his own troop—and began to harp on the old out-worn lie; of how Richard Page, first of the name, had got his wife out of that ship-load of women gathered up by the London Company from God knows where and sent out to Virginia to mate with our pioneers, and how the taint had come down the line to make cowards of the men, and——

I think he was going, on to tell how it wrought in the women of our house when my hand fell upon his shoulder and he was made to spin around and face me.[8] I do not know what I said; nor would Jack Pettus tell me afterward. I know only that there was a hubbub of voices, that the murky candlelight of the dismal kennel had gone red before my eyes, that Seytoun’s fat hand was lifted, and that before it could fall I had done something that brought sudden quiet in the low-ceiled room, like the hush before a tornado.

Seytoun was dabbling his handkerchief against the livid welt across his cheek when he said, with an indrawing of the breath: “Ah-h! So you will fight, then, after all, will you, Mr. Page? I had altogether despaired of it, I do assure you. To whom shall I send my friend?—and where?”

Pettus saved me the trouble of replying; saved me more than that, I think, for the red haze was rising again, and Seytoun’s great bulk was fast taking the shape of some loathsome thing that should be throttled there and then, and flung aside as carrion.

“Captain Page lodges with me to-night at Tappan,” I heard Jack say, and his voice seemed to come from a great distance. And then: “I shall be most happy to arrange the business with your friend, Captain Seytoun, the happier, since my own mother’s mother was a Page.” After which I was as a man dazed until I realized that we were out-of-doors, Pettus and I, in the cold frosty mist, and that Jack was pitching me into the saddle of a borrowed horse for the gallop to the camp at Tappan.

“I’ve taken it for granted that your leave covers to-night and to-morrow morning,” said this next friend of mine, when we were fairly facing southward.

[9]“It does,” I replied; and then with the battle murmur still singing in my ears, and the hot blood yet hammering for its vengeful outlet: “Let it be at daybreak, in the grass cove at the mouth of the creek, and with trooper swords.”

It was coming on to the early December dusk when we rode through the headquarters cantonments below Tappan village, and the four miles had been passed in sober silence. I know not what Jack Pettus was thinking of to make him ride with his lips tight shut; but I do know that my own thoughts were far from clamoring for speech. For now a certain thing was plain to me, and momently growing plainer. By some means Seytoun had learned that I was under bond not to fight him, and he knew what it would cost me if I did. Wherefore, his repeated provocations had an object—which object would be gained, and at my expense, whichever way the morning’s weather-cock of life and death should veer.

Hot on this thought came the huge conviction that I had merely played into my sworn enemy’s hands. If he should kill me, I should certainly be the loser; if I should kill him, I should still be the loser, with the added drawback of being alive to feel my loss.

We were walking the horses, neck and neck, up the low hill leading to the legion cantonments when I asked Jack what I had said and done in Van Ditteraick’s, and if it were past peaceful, or at least postponing, remedy.

“Never tell me you don’t know what you said and did, Dick,” he laughed.

[10]“But I don’t,” I asserted, telling him the simple truth. “I saw things vaguely, as if the place were filled with a red mist, and there was a Babel of voices out of which came a great silence. Then I saw Seytoun with his handkerchief to his face.”

“You saw and heard and did quite enough,” he replied, and his smile was grim. “And there is no remedy, save that which the doctors—and sundry hot-blooded gentlemen of our own ilk—are fond of; namely, a bit of blood-letting.”

“Yet, Jack,” I stammered, “if I say that some remedy must be found; that it is worse than folly for me to fight this man at this time?”

He stopped his horse short in mid-road and swore at me like the good friend he was.

“If you could turn your back on this now, Dick Page,” he raged, when the cursing ammunition was all spent, “I could believe at least one thing the captain says of you. He called you a coward,—as I remember,—and put a scurrilous lie on all the Pages since the first Richard to account for it. Great heavens, Dick! can’t you see that this lie must not go uncontradicted?”

“You are altogether right, Jack,” I acquiesced; and then, telling the simple truth again: “This day I seem to have lost what little wit I ever had. As you say, there is no remedy, now; so we fight at daybreak.”

“Of course you do,” said Pettus; and so we rode on to the horse-rope where the legion mounts were tethered.

[11]It was at the door of Pettus’s quarters, one of the rude log cabins chinked with clay that the army had been throwing up for winter shelters, that a surprise was awaiting me in the greeting of Melton, a young Pennsylvanian who was acting-orderly for General Washington.

“Good evening, Captain Page,” he said pleasantly. “You have despatches from Colonel Baylor for the general?”

“No, Mr. Melton,” I replied, wondering a little. “I am on leave until to-morrow. This is my birthday.”

“Ah,” said he, taking my hand most cordially, “allow me to wish you many happy returns.” Then he went back to the matter of the despatches I was supposed to be carrying. “It is very singular; Mr. Hamilton seemed quite sure, and he was certainly advised of your coming to Tappan headquarters. Perhaps you will be good enough to report to him—after supper?”

I said I should be honored, and he went his way and left us to our frugal evening-bread—how the Dutch speech clings when once you have washed your mouth with their country wine!—prepared for Pettus by his scout and horse-holder.

It was not a very social meal, that supper in Pettus’s hut before the cheerful open fire—fire being the one thing unstinted in that starving camp. My thoughts were busy with the meshings of the net into which I had stumbled; and as for Jack, I think he must have been eager to get me out of the way before[12] Seytoun’s second should call. At any rate, it was he who reminded me of Melton’s hint that I would be expected at General Washington’s headquarters, and I do him no more than fair justice when I say that he sped the parting guest quite as heartily as he had welcomed the coming.

So it came about that it was still early when I set out in the starlight for the low tilt-eaved farm-house a half-mile farther up the road, passing on the way the field where poor Major André had paid his debt and where he now slept in his shallow grave; passing also, a scant hundred yards from the great chief’s headquarters, the fortress-like stone house where André had heard his sentence and spent his last night upon earth.

I FOUND Lieutenant-Colonel Hamilton waiting for me in that room of the De Windt house which served as an outer office in the commander-in-chief’s suite. It was my first visit to our army’s brain and nerve center since the execution of Major André, and I saw, in the posting of double sentries and by the many times I was halted before I could come to the door of Mr. Hamilton’s room, one of the consequences of Arnold’s treason. Our general was no longer free to go and come and be approached as simply as he had been in former times.

Mr. Hamilton’s greeting was as pleasant as Melton’s had been, though few ever saw him otherwise than cordial and suave. A slender fine-faced stripling, with the deep-welled eyes, short upper lip and sensitive mouth of his French mother, a man but little, if any, older than I, he had the manner of a true gentleman gently bred, and few as were his years, he carried a wise head on his shoulders.

“Good evening, Captain Page. Come in and stretch your legs before my fire,” he said; “you have the first requisite of a good soldier, Captain; you come promptly when you are called.”

[14]At first I thought he was rebuking me gently because I had stopped to sup with Jack before reporting myself, but a quick glance at his smiling eyes showed me that I was wrong. Yet without that explanation I was left in the dark as to his meaning.

“A soldier’s call is apt to be an order, Mr. Hamilton,” I said, giving him the lead again.

“So was yours,” he announced. “But we scarcely looked for you to come before midnight, ride as you would.”

“I was sent for?” I asked.

“Surely; didn’t you know it?”

“I did not. I left Salem at daybreak, with two days’ leave from Colonel Baylor.”

“In that case,” he said reflectively, “you should have met Halkett on the road, riding with letters to you and to Colonel Baylor.”

“I did not come by the main road to King’s Ferry. I had agreed to meet Lieutenant Pettus at Nyack, and——”

“Ah,” he said, smiling again; “a drinking bout at Van Ditteraick’s in honor of your birthday, I take it. You are sad roisterers—you Virginia gentlemen”—a thing he could say and carry off, since he was himself West-Indian born.

“It was but a single bottle, I do assure you, Mr. Hamilton,” I protested; “and such wine as would make one vow never to be caught under the shadow of a grape-vine again.”

“Still, you are sad roisterers,” he persisted quietly. “And it was precisely because you are the saddest of[15] them all, and, besides, the greatest daredevil in your own or any other troop, that you were sent for at this particular time, Captain Page.”

I hope I was not past blushing at the left-handed compliment, well-meant as it seemed to be. Some few passages there had been in my captaincy where foolhardy daring had taken the reins after wise caution had dropped them hopelessly upon the horse’s neck, and the event on each occasion had had the good luck to prove the wisdom of the foolishness. But as for being a daredevil—why, well, that is as it may be, too. The veriest sheep of a man will often fight like the devil if you can corner him and get him well past caring too much for the precious bauble called life.

But I was killing time, and Mr. Hamilton was waiting.

“Don’t count too greatly upon a roisterer’s courage,” I laughed. “But what desperate venture does his excellency wish to send me on, Mr. Hamilton?”

He held up a slim hand warningly.

“Softly, Captain Page, softly: the commander-in-chief is not to be at all named in this. You will take your orders from me—if you take them from any one; though as to that, there will be no orders. And you have hit on the proper word when you call the venture ‘desperate.’”

“You are whetting my curiosity to a razor-edge,” I averred, laughing again. “By the time you reach the details I shall be ripe for anything.”

He sat staring at the blazing logs for a long minute before he began again; not hesitating, as I made[16] sure, but merely arranging the matter in orderly sequence in his mind.

“First, let me ask you this, Captain Page,” he began at the end of the forecasting minute. “You come of a long line of gentlemen, and no one knows better what is due to a keen sense of honor. How far would that sense of honor let you go on a road which would lead to Sir Henry Clinton’s discomfiture and possible overthrow?”

“There need be little question of honor involved in dealing with Sir Henry Clinton,” I replied promptly. “When he bought Benedict Arnold for a price, and sent his own adjutant-general into our lines as a spy, he set the pace for us. I’d keep faith with any honest enemy, to the last ditch, Colonel Hamilton; but on the other hand, I’d fight the devil with fire, most heartily, if need were, and take no hurt to my conscience.”

“Then I may go on and tell you where we stand. You know very well, Captain Page, the ill effects of Arnold’s treason and desertion; how the infection is spreading in the rank and file.”

I said that I did know.

“This infection is like the plague; it must be stamped out at any cost,” he declared, and the deep-welled eyes flashed angrily. “It is a double evil, sapping the honor of our army on the one hand, and bringing us into contempt with the enemy on the other. The remedy must be a sharp lesson, no less to Sir Henry Clinton than to the traitors. Do you see any way in which it can be administered, Captain Page?”

[17]“If you could once lay hands on Benedict Arnold,” I suggested.

Hamilton nodded slowly.

“You have put your finger most accurately on the binding strand in the miserable knot. If the chief traitor could be apprehended and brought to justice, it would not only stay the epidemic of desertion, it might also convince Sir Henry that we are not to be treated as rebels beyond the pale of honest warfare.”

“Truly,” I agreed. “I wonder it hasn’t been done before this.”

“It has been tried, Captain Page. Let me tell you a thing that is thus far known only to our general, to Major Lee and myself. You have heard of the desertion of a certain sergeant from our army?”

I bowed, saying that I had and knew the man’s name.

“This sergeant posed as a deserter only for the better concealment of his purpose; he went upon this very errand we are speaking of. He is in New York now, and is not only unable to accomplish his object, but is in hourly danger of apprehension and death as a spy.”

“Pardon me, Colonel Hamilton,” I broke in, “but you should not have sent, as they say, a boy to mill. This man would be helpless if only for the reason that he comes from the ranks. Arnold was always a stickler for the state and grandeur of his office; a common soldier could never get near enough to plot against him.”

“Again you have touched upon the heart of the[18] matter, Captain Page. The commander-in-chief suffered the sergeant to go in the first instance (he volunteered for the enterprise, you understand) because he was only a sergeant, and it was not thought to be an errand upon which a commissioned officer could honorably go. But now the affair is all in confusion. The enterprise promises to fail, and our man may easily lose his life on the gallows.”

I rose to terminate the interview.

“Are there any special instructions for me, Colonel Hamilton?” I asked.

The general’s aide laughed like a pleased child and bade me sit down again.

“What a hot-headed firebrand you are, to be sure, Captain!” he said warmly. “I was certain you would not fail us. Have you no curiosity to learn how the choice fell upon you?”

“None whatever,” I replied. “I’m vastly fonder of action than of the whys and wherefores.”

“Then I need only say that you have me to thank for the choice. When it was decided to seek for a stronger head than the sergeant’s seems to be, the choice of the man was left to me, and it was agreed that no one else should know. So this is strictly between us two, as it should be. Colonel Baylor merely knows that you have been detailed for special duty.”

“Good,” I commented. It was best so. By this means I should stand or fall quite alone, as the leader of a forlorn hope should be willing to do.

“As for your instructions, there can be none at all. Our information from the sergeant is most meager;[19] and if it were not, we should not hamper you. Haste and success are your two watchwords. Have you money?”

I had. The Page tobacco of the year before had escaped the clumsy British blockade, and when we Pages sell our tobacco, we lack for nothing in reason.

“That is a comfort,” he smiled. “Our sergeant begged for five guineas in one of his letters, and I promise you we had to scratch painstakingly before we found them. Now for your plan: have you any?”

“The first move is simple enough,” I rejoined. “I shall desert, as the sergeant did, and throw myself into the arms of the enemy. After that—well, sufficient unto the moment will be the evil thereof. I must be guided wholly by conditions as I find them.”

“So you must. And for your communications with me, you may use the same channel the sergeant is using—a Mr. Baldwin, of Newark, who will carry your letters. How will you reach New York?”

I thought a moment upon it.

“The river is the quicker. I have a boat at Nyack; the one in which I pulled from Teller’s Point to-day.”

There was a little pause after this, and I saw that my companion was staring thoughtfully into the fire.

“We have been going at too fast a gallop, Captain Page,” he said at the end of the pause. “We must go back a moment to that point that was raised in the beginning. If you could go with your troop at your back and cut the traitor out and bring him home that would be one thing—and I know of no man fitter to[20] attempt it. But to go as you must go, and use guile and subterfuge ... truly, Captain Page, you must sort this out for yourself; to determine how far in such a cause an officer and a man of honor may go. I lay no commands upon you.”

I put the scruple aside impatiently.

“Benedict Arnold has put himself beyond the pale, Colonel Hamilton. There can be no question of honor in dealing with such as he.”

“Perhaps not,” was the low-toned reply; “though that word of yours is most sweeping and far-reaching. I mean only to leave you free, Captain Page. Our desires, keen as they are, shall not run farther than your own convictions of an honorable man’s duty.” Then he looked at his watch. “The tide serves at eleven, and you have the borrowed horse to return to Nyack. It is best so, since in that way you will seem to be returning to your troop at Salem.”

His mention of the borrowed horse first set me to wondering how he came to know that I had borrowed a horse; but a moment later the wonder went out in a blaze of sudden recollection. As I am a living man, up to that instant I had clean forgotten that I was pledged to meet Captain Howard Seytoun at dawn-breaking in the grass cove at the river’s edge!

I was on my feet and breathing hard when I broke out hotly: “Good heavens, Colonel Hamilton! I can not go to-night; it is impossible! A thing I had forgotten——”

He rose in his turn and faced me smiling.

“Tell me where she lives, Captain Page,” he said[21] slyly, “and I’ll promise to go in person to make your excuses. Nay, no cunningly devised fables, sir, if you please; it is always a woman who hangs to our coat-skirts at the plunging moment. But seriously,” and now his face was grave, “there should not be an hour’s delay. Not to mention our sergeant’s safety, which seems to be hanging in a most precarious balance, there is a sharp chance of your missing the target entirely. Word has come that Arnold is embodying, or has embodied, a regiment with which he may take the field at any moment. No, you must go to-night, if you go at all.”

“But you were not expecting me here from Colonel Baylor’s camp until midnight,” I protested, trying to gain time for the shaping of some excuse that would hide the truth and still seem something less than childish.

“For the anticipating of which expectation by some hours, we are discussing this matter here in comfort before my fire, instead of on horseback and on the southward road, Captain Page. I had planned to ride with you to our outposts, enlisting you as we went.”

“Yet—good lord, Mr. Hamilton! if I could tell you—if I only dared tell you what it will cost me to go to-night....”

He spread his slender hands in a most gentlemanly way.

“I have laid no commands upon you for the services, Captain Page; as I have said, your going rests entirely with yourself. Nor must you think I am trying[22] to bribe you when I point out that the man who carries the enterprise through will have earned much at the hands of his country and of the army. It is for you to decide whether this obstacle of yours is great enough to weigh against the arguments for instant despatch—remembering that these arguments may well include the life of the worthy soldier who has piloted out the way for you.”

It has always been my failing to omit to count the personal cost of anything until the day of reckoning rises up to slap me in the face.

“I’ll go—to-night,” I said grittingly. “But if I could leave an explanatory word with Pettus——”

Again he stopped me in mid-career with a hand laid affectionately on my shoulder.

“You would cancel my permission with your own sober second thought, my dear Captain. That second thought will tell you that there must be no hint, no word or whisper that could remotely point toward your purpose. Further, you must go back to Pettus, smooth over as best you can your visit to me here, and lull his curiosity, if he have any. Then, if you can not tell him point-blank the lie about your returning northward to-night, wait until he is asleep, and make your escape as you can.”

We went somewhat beyond this, but not far; Hamilton telling me of his sergeant’s present besetment, and of how all his plans had come to naught. When I had it all he went with me to the door and I was out of the ante-room when he took leave of me and bade me God-speed; out under the stars and with[23] only the half-mile walk between me and Jack Pettus for the cooking up of all these raw conditions thus thrust masterfully upon me. I saw well enough what I must face; how, when I should turn up missing, Seytoun would lose no time and spare no pains in black-listing me from one end of the army to the other. Yet if I could go quickly and return alive, dragging our Judas with me as the result of the endeavor ... well, then Seytoun would still say that I had deliberately provoked a quarrel which I knew I could not carry out to the gentlemanly conclusion.

It was the cursedest dilemma, no matter how I twisted and turned it about. And to cap the pyramid of misery, there was a lurking fear that Mistress Beatrix Leigh might come to hear some garbled misversion of it, even in far-away Virginia, and would not know or guess the truth. Up to the very present moment, Seytoun owed his immunity solely to her, or rather to a promise I had made her the year before when I came out of the home militia to join Colonel Baylor’s new levies. When she should know the provocation, she might generously forgive the duel, though she had exacted the promise that I would not fight him; but would any explanation ever suffice to gloze over the fact that I had struck the man, and afterward had run away to escape the consequences?—for this is how the story would shape itself in Seytoun’s telling of it.

I saw no loophole of escape, no light on the dark horizon, save at one uncertain point. Seytoun was brave enough on the battle-field; all men said that for[24] him. Yet he was a truculent bully, and bullies are often weak-kneed where the colder kind of courage is required. What if he had pocketed my affront?—had failed to send his friend to Jack Pettus?

The slender chance of such a happy outcome sent me on the faster toward the legion cantonments; and when I saw the scattering of tents and log shelters looming in the starlight I fell to running.

Pettus was waiting for me when I kicked open the door of the low-roofed shelter and entered, and it was my good genius that prompted me to sit by the fire and ask for a pipe and a crumbling of Jack’s tobacco, and otherwise to mask the fierce desire I had to put my fate immediately to the touch. For my Jack was as quick-witted as a woman, and I remembered in good time that I had to deceive him. So my first word was not of Seytoun, or of the quarrel, but of Colonel Alexander Hamilton and the despatches I had been supposed to bring from my colonel.

“Curious how a rumor breeds out of nothing,” I commented, when we were comfortably befogged in the tobacco smoke. “Melton seemed to be sure that I must be the bearer of despatches; and Colonel Hamilton accused me of having ridden over from Nyack on a borrowed horse.”

“The which you did, despatches or no despatches,” laughed Pettus. “But how did you get on with Mr. Hamilton?”

“As one gentleman should when he meets another for a joint shin-toasting before a blazing fire of logs. We chatted amicably, after Mr. Hamilton learned[25] that I brought no word from Colonel Baylor; and when I could break off decently I came away.”

After this silence came and dwelt with us for a while, and when the fierce desire could be no longer suppressed I said, as indifferently as I could: “You have news for me, Jack?”

“If you call that news which we were both expecting—yes. Lieutenant Cardrigg has been here, in Captain Seytoun’s behalf.”

My gasp of disappointment slipped out—or in—before I could prevent it, and it did not go unremarked by Pettus.

“What’s that, Dick? You sigh like the furnace of affliction itself. Twice, already, you have changed your mind about this little riffle with Seytoun. It is far too late to change it again. I warn you as a friend.”

“Truly, it is indeed far too late,” I echoed, agreeing parrot-wise. Then: “You arranged the business as we talked?——to-morrow morning, in the grass cove at the mouth of the creek?”

“How else would I arrange it?” said Pettus querulously. “You were as precise in your instructions as any girl prinking herself for a rout.”

“It is well to be precise,” I offered half absently. The worst had befallen now, and my brain was busy with the shameful consequences which must ensue.

“Cardrigg haggled a little over the trooper’s swords,” Pettus went on reflectively, after a moment. “He is a chip of the same upstart block out of which our red-faced captain was hewn. He said you might[26] have chosen rapiers, if only out of consideration for the captain’s standing; meaning to imply thereby that the captain, at least, was a gentleman, and should be allowed to fight with a gentleman’s weapon.”

“You yielded him the point?” I questioned, trying to show an interest which I could not feel.

“Not I, damn him. I gave him to understand flatly that we stood upon our rights, and that the trooper’s sword was good enough for his principal—or for him and me, if it came to that.”

“It is a small matter,” I said, thinking bitterly that Pettus could not vaguely guess how small a matter this dispute over the weapons had suddenly become. Then I saw how I might perhaps fend off the last and worst of the consequences of the morrow’s revealments; but it was necessary first to pave the way cautiously and carefully.

“The captain is a good swordsman, whatever else may be said of him,” I began after another interval of silence. “It may easily happen that the man who fights with him will cross a wider river than this Hudson of ours, Jack.”

“Bah!” Pettus spat the word out contemptuously. Then he added the friendly smiting, as I expected he would. “Don’t try to make me see you in any other light than that of a true man, Dick.”

“I would not willingly do that, Jack, believe me. But there are always chances, and the wise man, though he were the bravest that ever drew steel out of leather, will provide against them. If I should not come off from this night’s—from to-morrow morning’s[27] work with a tongue to speak for itself, will you carry a word for me?”

“Surely I will. But to whom?”

“To Beatrix Leigh. Tell her she must go down to her grave believing that I was no craven. Tell her——”

“I’m listening,” said Pettus, when the pause had grown to an impossible length.

My lips were dry, and I moistened them and swallowed hard. After all, what word was there that I could send to the woman I loved without taking the risk of betraying my trust as an officer and the confidant of Mr. Hamilton?

“It isn’t worth the trouble,” I went on, when the hopelessness of it became plain. “She will understand without my message; or she will refuse to understand with it.”

Jack laughed boisterously. “I’m no good at conundrums, Dick. I’ll tell her the captain challenged you for brushing a fly from his face. Will that do?”

I smiled in spite of my misery. There would be nothing to tell Beatrix Leigh or any one else about the meeting which was already impossible for one of the combatants.

“Let it go, Jack, and pinch the candle out. Didn’t you hear the drum-roll? We’ll have the patrol in upon us presently. Do you turn in, and catch your few hours of beauty sleep. It’s one of my notions to sit alone before the fire on my birthday night, casting up the year’s accounts. You’ll indulge me, won’t you?”

Jack did it, grumbling a little at what he was[28] pleased to call my churlishness. It was weary work killing the time till he should be safely asleep. I was young, vigorous, and for all my youth, somewhat of a seasoned veteran, but that lonely hour or more spent before Jack Pettus’s fire went nearer to sapping my determination than any former trial I could recall.

I might have made my exit sooner, I suppose. Though he tossed restlessly in his bunk, Jack was asleep before I had filled my second pipe. But there was no object in my reaching Nyack before tide-turning, and I stayed on, dreading the moment which would set the wheels fairly a-grind on my hazard of new fortunes.

It was the hour of guard-changing when I rose noiselessly, struggled into my watchcoat, slung my sword around my neck so that it should not drag and waken Jack, and cautiously secured the little portmanteau which held all the impedimenta I had brought with me from the camp at Salem.

I was carefully inching the door ajar to let me out when Pettus stirred afresh and threw his arms about, muttering in his sleep. I waited till he should be quiet again, and while I stood and held the door, the mutterings took on something like coherence.

“I say you shall drink it! Up, man, up! Now, then; here’s to the loyalty of the Old Dominion, and may the next Virginian who smirches it——”

I whipped through the half-closed door and closed it behind me, softly. It was sobering enough to do what I had to do, without staying to listen to such a word of leave-taking from the dearest friend I owned.

[29]I found the borrowed horse where I had left him at the hitching-rope, and had the saddle on, and the portmanteau strapped to the cantle, when Middleton came up with the guard relief.

“Ho, Captain Page!” he chuckled, when the patrol had thrown the lantern light into my face, “I thought I had caught another deserter in the very act. Has your leave expired so soon?”

I forced a laugh and said it had, more was the pity. And then he asked how I expected to get across the river at that hour; whereupon I told him a part of the truth, saying that I should ride back to Nyack, and from there take the small boat in which I had drifted and rowed down from Teller’s Point.

At this he had the saddle flung upon his own beast, and mounted and rode with me to put me past the sentries on the Nyack road; and now I was enough recovered to grin under cover of the darkness and to picture his rage and astonishment when, within a day or so, he should learn that he had been setting another deserter safely on his way to the British lines. For I made no doubt that the camp, and all the others in the Highlands, would presently be ringing with the news that a captain of Baylor’s Horse had been the latest to go over to the enemy—as, indeed, I hoped they would, since my best guaranty of safety in New York would be in the hue and cry I might leave behind me.

Lieutenant Middleton bade me God-speed at a turn in the road about a mile from his cantonments, and from this on to Nyack I pushed the borrowed nag[30] smartly. At Van Ditteraick’s stable there was only a sleepy horse-boy to rouse up and meet me, and when I had paid the horse’s hire, I made him go with me to the waterside to help me embark, so there might be a witness of the way I went and the manner of my going.

It was the boy himself who pushed me off and saw me lay the boat’s head up the river. And, sleepy as he was, he had wit enough to mumble in broken Dutch that the dunderhead captain had taken the wrong turn of the tide for a pull up the stream.

I headed upward and currentward only until I had made sure that my small boat could not be seen from the western shore. Then I turned the boat’s bow down-stream and pulled lustily for half an hour to warm me, for the gray and cloudy day had cleared into a night of bitter cold.

It was near midnight, as I judged, when I made out by the configuration of the shore lines my passing from the great lake of the Tappan Zee to the narrower channel of the river proper. Here, where King’s Ferry crossed from bank to bank, lay my greatest chance of danger; and taking the mid-channel for it, I unshipped the oars and let the boat drift as it would in the tideway. So floating, when I was well past the line of the ferry, past all hazard of being discovered by one of our patrol boats, as I imagined, I ventured to step the mast and to hoist the little leg-of-mutton sail with which the boat was provided. The showing of the small triangle of white cloth was my undoing. The little craft had scarcely felt the wind-pull,[31] when a dark shape shot swiftly out from the shadow of the western shore and a voice came bellowing at me across the water.

“Ahoy, there! Spill your wind and come to, or we’ll fire upon you!”

My answer was to ship the oars as silently as possible, and to settle down to the long lifting stroke old Uncle Quagga, our black boatman, had taught me on the quiet waters of the James River in the peaceful days before the war began. It promised to be a hopeless flight, with only my two arms against a dozen; but what disquieted me most was the stentorian voice that came booming once again across the gap, cursing me and commanding me to heave to. For the yell was Seytoun’s; and now I remembered that Jack had told me something about Seytoun’s being on boat duty for the middle watch of the night.

IT IS little less than marvelous how the mind’s eye sweeps all the horizons instantly at the apexing point of a crisis. Seytoun’s cursing hail, the sheering cut-water hiss of the well-manned boat as it drove out to head me off, the panic helplessness of my attempt to escape—none of these was distracting enough to cloud the picture of the frightful consequences which would follow my overtaking.

Mr. Hamilton might save me from a deserter’s death; I supposed he would find means to do that much, though all the army would be clamoring for vengeance on me. But every other humiliation the wrath of man could devise would be mine; and in all the mad hurry of the moment one grim determination stood apart in my brain and held itself in readiness to act. I would never be taken alive. If the bullets which would presently begin to spit from the muskets in the watchboat should not put me out of misery, I could at least go overboard with the skiff’s anchor stone to hold me under for the necessary choking time.

The bullets came quickly enough, a ragged fire of them buzzing high overhead to emphasize Seytoun’s[33] second warning. If the marksmen in the watchboat had been my men, I thought I should have a word to say to them about holding well down on a target when powder and lead were worth their weight in gold—as they were with us in that winter of 1780. They wasted a dozen shots on me, I think, before a long drum-roll boomed across the water to tell me that now the camp was aroused and more boats would be coming.

That was only an incident, however. My business was to put my heart and soul into the oars and to keep the narrow gap between me and Seytoun’s boat from closing any more swiftly than it had to. It was closing certainly enough, and by leaping boat-lengths, when my straining ears caught the sound of other oars rolling in muffled row-locks, and a guarded hail came from somewhere in the darkness just ahead of me. I dared not turn around to try to descry the fresh peril. Seytoun’s marksmen were doing better now, and coincident with the low-toned hail ahead a bullet struck the stern of my shallop and neatly stuck a splinter in the calf of my leg.

Another volley from the guardboat would have settled matters, but the volley was never fired—at me. At the flint-snapping crisis my boat’s bow crashed in among banked oars, dark shapes loomed suddenly all around me, and a gruff voice shouted, “Avast there, you lubber! Heave to, or we’ll sink you!”

I needed no command to stop me. The collision with the banked oars, and a dozen hands gripping the gunwales of my shallop, did that for me. What I[34] most needed was the discretion to throw myself flat in the bottom of my boat to escape the storm of lead that was promptly hurled at my pursuers—and that I had, too.

When it was all over, and Seytoun’s boat had turned tail to claw out of harm’s way in frantic haste, I learned to what I owed my opportune deliverance. I had pulled straight into the midst of a British boat expedition (one of the many since Admiral Sir George Rodney had come to Sir Henry Clinton’s aid), sent up from New York to take a chance of surprising some one of our outpost camps. I was rejoicing secretly that my ill-luck had killed the chance of such a surprise, when I was brought roughly to book by the officer in command of the expedition.

“Now, sir, who the devil are you, and what are you doing here?” were his shot-like questions, when my craft had been passed back to the long-boat which served as the flag-ship of the flotilla.

I gave my name and standing briefly, and was adding a hypocritical word of thanks for my rescue when he cut me off abruptly.

“A deserter, eh?” he rasped. “It’s a thousand pities we didn’t let them take you. An officer, too, you say? Then the pities are ten thousand. I would to God some of your fellows in that boat had shot straighter!”

His sentiments were so soldierly and worthy that I loved him for them, and was able to pull the splinter from my leg and laugh.

“You don’t follow your commander-in-chief’s[35] lines very closely, sir,” I ventured. “We gentlemen who are sick of our bargain with General Washington and the Congress get a warmer welcome from Sir Henry Clinton than you are giving me. But there are deserters and deserters; some who are traitors in fact, and some who are merely coming to a better sense of their duty as they see it. My conscience is clear, sir.”

I hoped he would not suspect the double meaning in my answer; as, indeed, he did not. As well as I could make him out in the darkness, he was a bluff, hearty bully of a man; a sea officer, I took it.

“We’ll take you back with us, since that is what you want,” he rejoined crustily; adding: “And I’d hang you to a yard-arm when we get there, Captain Page—as Sir Henry Clinton doubtless will not. To the rear with you, and consider yourself a prisoner. Pass the captive astern, Bannock, and take the oars out of his boat,”—this last to the ensign in command of the long-boat.

The effect of this order was to turn me adrift without any means of locomotion, and my shallop dropped away from the flotilla on the slowly ebbing tide until the British boats became a shadowy blur in the night. There was some huddling of them for a hasty council of war, I judged, and if so, an order to retreat was all that came of it. With our forces on either side of the river aroused and alert, as the firing would ensure, there was little else to be done.

My masterless craft had drifted a mile or more when the boat expedition overtook me. With no more[36] ado my boat was taken in tow, and I chuckled inwardly. I love a boat and the water as I love a good horse; but it is worth something to have your enemy drag you where you expected to drag yourself, and when the shadows of the great western cliffs were blackening thick upon the waters, I kicked the rowing seat out of the way, and stretched myself at ease in the shallop’s bottom to get a soldier’s nap before the sun should rise upon my further adventures.

The day was dawning coldly when I awoke and found that my rescuers—or my captors—were debarking at the town landing-place under the guns of Fort George. It was a raw morning, my leg was stiff and sore from the splinter wound, and the ensign who ordered me to tumble out had evidently taken his cue from his gruff commander and cursed me heartily because I did not move as quickly as he thought I should.

It is remarkable how the morning after takes the fine edge off the enthusiasm and daring of the night before. When I set foot upon the landing-stage and remembered all that I had undertaken to do in this British stronghold of New York, remembered, also, how at this very moment, most likely, Jack and Seytoun, and—save Mr. Hamilton alone—every friend and enemy I had left behind me in the camp at Tappan was cursing the very day of my birth, my teeth chattered with the morning’s cold, and I would have given many broad acres of the Page tobacco lands to be well out of the wretched tangle into which my desperate mission had led me.

[37]My first near-hand view of the lower town, obtained after I had been turned over to one of Sir Henry Clinton’s aides—who was my host or guard, I could not tell which—brought a decided shock. My memories of the city, carried over from a visit made with my uncle Nelson when I was a hobbledehoy of sixteen, were rudely swept away. The great fire of the night of September 20th, 1776, just after the British General Robertson had driven our army back upon Harlem Heights, had made a ruin of what had been the best-built portion of the lower town. Starting near Whitehall Slip, it had left blackened ruins all the way across to the Bowling Green and for some distance up on both sides of Broad Way, and but little in the way of rebuilding had been done during the four years of British occupation. Instead, some of the ruins had been converted into makeshift dwelling places by using the chimneys and parts of the walls that were still standing, eked out with spars from the ships and old canvas for shelter.

It was a dreary prospect that was revealed as we, my guard-host and I, came around the western bastion of the fort and so into the lower end of Broad Way. The fire had spared some few houses on the left, and in one of these, so Mr. Hamilton had told me, Arnold had his headquarters and living-rooms. It was to an inn just beyond these houses, and on the edge of the ruined district, that my walking companion led me; and by the time we were inside and were breaking our fast in the blaze-warmed coffee-room, the hue of things had become less somber, and I could laugh and[38] crack a joke with my entertainer much as if he had been Jack Pettus masquerading in a red coat.

“You do good justice to the commissary, Captain Page,” said my youth in the red coat, when I had begged his leave to order more of the ham and eggs that reminded me most gratefully of Virginia and home.

“If you could know how I have been starved, Mr. Castner,” I retorted. “All you have to do for us—for the rebels, I mean—is to hold them still for a few months longer, and hunger will do for them what your arms have somehow seemed unable to do.”

“Is it that bad, Mr. Page?” he asked.

“Worse than I can describe, I do assure you. I doubt not we of the turncoat legion assign all sorts of reasons for our forsaking of the cause, but I am telling you the bald truth—as I shall tell Sir Henry. We are hungry, and an empty stomach knows neither king nor Congress.”

But my young lieutenant laughed in a most friendly way and shook his head at this.

“You are carrying it off as a brave man should, Mr. Page, and making a jest of it. But you are like a good many of the others; a true Loyalist at heart, with only the eleventh-hour determination to turn your back upon whatever influences swung you first in the wrong direction. Confess, now; are there not many others in the same case, and lacking only the eleventh-hour courage to come over?”

I said there were, doubtless—and hoped most fervently that it was the lie I firmly believed it to be.[39] Then, after I had answered freely all his questions about our camp at Tappan—with more and more ingenious lies, you may be sure—I ventured upon the ground of my own perilous debate.

“There have been rumors in the Highlands of Mr. Arnold’s raising of a regiment of his own here in New York. Is that so, Mr. Castner?” I asked guardedly.

The lieutenant nodded, and there was a graver look in his eyes when he asked, in turn, “Do you know Mr. Arnold, Captain Page?”

“I haven’t that honor, as yet,” I replied. “My short service in the Continental Line has been in the horse; and he, as you know, has been lately in garrison at West Point.”

He bowed thoughtfully. “A strange man, Mr. Page; and growing stranger to all of us, I think, as the days pass. He has not come over to us for any overmastering love of the king or the king’s cause, I fear.”

“No?” said I.

“It is little likely. If I read him aright, he is burned and seared through and through with his own ambition.”

It was no part of my plan to be drawn into open criticism of the man I was shortly to approach in the character of an outspoken fellow traitor.

“We must not judge too hastily, Mr. Castner,” I put in placably. “Arnold was greatly respected by his former subordinates, and, truly, he did many things to win their regard, I am told. But that is neither[40] here nor there: this legion he is enrolling—is it horse or foot?”

“Foot. It is called the ‘Loyal American,’ and is pretty largely composed of—of men who, like yourself, Mr. Page, have changed flags.”

“Are the lists full?” was my next query.

The lieutenant smiled.

“Would you take service under your country’s bitterest enemy, Captain Page?”

I laughed.

“Beggars mustn’t be choosers. And as for my country’s enemies; my country is the king’s, or at least, he says it is, though you must confess, Mr. Castner, that the standing-places where a Loyalist may hear the whipping of the royal standard above his head have become sadly few and restricted.”

Once again the lieutenant was shaking his head in mild deprecation.

“You must teach your tongue a better trade, Captain Page,” he said quite good-naturedly. “There are those in this town who would find fault with that last speech of yours.”

I saw at once, what I should have seen at the outset; that this frank-faced lieutenant was not one to be played with in double-meaning rashnesses. So I went back to Arnold and his “American Loyalists,” or “Loyal Americans,” or whatever lying phrase it was that headed his regimental book.

“You have not told me yet of Mr. Arnold’s conscript lists,” I reminded him.

“Nor do I know,” he replied, and was going on to[41] say more when a tall, harsh-visaged fellow, wearing the insignia of a recruiting sergeant, looked in at the door, swept the apartment with a shrewd glance, as if in search of material for his trade of whipper-in, and was turning away when the lieutenant marked him and said to me: “There is a man who can tell you more than I can.” And then to the soldier: “Hey, Sergeant, a word with you!”

It was not until the man stood at our table-end and was near enough to shock me heartily that I recognized him as Major Lee’s emissary, John Champe; the man I had come to drag out of the peril he had blundered into.

Lieutenant Castner smiled at my start of surprise, and he was further edified, I suppose, by Champe’s drawing back with a muttered oath at his recognition of me. There was humor in the situation, but I was in no frame of mind to appreciate it just then.

It was Champe who first broke the awkward little silence. “You called me, sir?” he asked, saluting Castner, and turning his back on me.

I shall never forget how the young redcoat lieutenant played the gentleman at this crisis. Had there been a trace of malice in his heart he might have flung us two flag-changers at each other’s throats and stood aside to see the sport. Instead, he replied to Champe, quite gravely.

“Yes; your lists for the Loyal Americans—are they filling well, Sergeant?”

“They are closed,” said Champe, with his dour face as expressionless as a slab of wood.

[42]“Ah,” said Castner; and then, with a hand-wave of dismissal for the sergeant, which Champe obeyed instantly: “That answers your question, Captain Page. I hope it does not seriously change your plans.”

I assured him that it did not; telling him that I had no plan beyond seeking an audience with Sir Henry Clinton at the earliest possible hour.

“Then your inclination matches with the necessities,” laughed my jailor. “I should be obliged to put you under guard, conveying you to Sir Henry forcibly, if you were not minded to go of your own accord.”

My heart beat a little less steadily at this. Was it possible that Mr. Hamilton’s plot had leaked so swiftly?—that word of my coming, or of my planned-for coming, had already reached the British commander-in-chief? It was a soul-destroying thought, but Castner’s next word relieved me.

“It is a general order,” he explained. “Sir Henry wishes to see each of you gentlemen—our friends from the other side, you know—as soon as may be after your arrival. If you have finished your breakfast we may as well go at once. I don’t know how your late staff headquarters keeps its hours, but our Sir Henry is an early riser.”

There was no reason on my part for delay, and every reason for haste without the appearance of haste. So I made ready to go with the lieutenant, and we presently fared forth into the crisp December morning and took our way to the row of Dutch-fashioned[43] houses with their sides to the street and facing the Green, the row lying a little to the right of Fort George as you face the harbor.

Before one of the houses a sentry stood on guard, and with a stiff presenting of his duty salute to my officer, the man passed us up the steps.

Castner put me into the audience chamber of the man who stood, for us of the patriotic side, as the embodiment of British duplicity and tyranny, without a word to me by way of preparation; and in introducing me I thought there was a twinkle of grim humor in his grave boyish eyes.

“Sir Henry, I have the honor of presenting to you Mr. Richard Page, late Captain Richard Page, of Baylor’s Horse, in Mr. Washington’s army, and the newest of our new friends.”

His handicapping of me in these few words of introduction was most embarrassing—as perhaps it was meant to be—and for the moment I could only stare at the great man sitting calmly behind his writing-table, which, as I remember, was well littered with papers.

At first sight the British commander was disappointing. He was short, fat and stodgy, with the heavy face of a good feeder, and his nose was aggressively prominent. His eyes, as I saw them, were cold and calculating, and I could never fancy them lighting with enthusiasm or mellowing into anything like good-fellowship. And, indeed, it was told me afterward that he was a man to take his pleasures stolidly, warming neither to wine nor women. Washington, Greene,[44] Hamilton, Lee—all of our leaders, were soldiers and they looked it. But this broad-girthed little man with the great nose and the chilling eyes was a soldier and he did not look it.

To my relief, the interview was short, and to my still greater relief it was not made harder for me by the lieutenant’s presence, that gentleman having disappeared after presenting me. Naturally, Sir Henry wanted news of Washington’s army, his dispositions, his plans and intentions; and having by this time come to my own in my heritage of the Page impudence, I lied to him as freely and joyously as I had to Castner, taking care only to make the lies dovetail neatly with what I had told the lieutenant over the inn breakfast-table.

But my cross-examiner saved his shrewdest question for the last, as if he had been a lawyer.

“Now, for yourself, Mr. Page,” he said finally, fixing me with that cold stare that seemed to read my inmost thoughts. “What brought you here?”

This was a harder thing to lie out of than any of the others. My family, and my own record, for that matter, were too well known to let me dish him up some plausible story of how we were all merely waiting the chance to come over to the king’s side. I must invent some personal grievance, and with those chilling eyes upon me it was a task to make the blood thicken in my veins—at a time when it should have been galloping most freely.

It was at this point that I had an inspiration. There is no lie so compelling as the truth, when the[45] truth can be made to serve the purpose of a lie. I had heard that Sir Henry frowned like a straight-laced Puritan upon dueling; that he put it under the ban for his own officers, punishing for it as he would for any other infraction of orders.

My resolve was taken on the spur of the moment.

“Aside from one other cause, which was great enough in itself to make me wish to change flags, I ran away from a duel,” I told him, returning the stare as hardily as I dared.

“How is that, sir?” he demanded, a shade less coldly.

At that I gave him the story of the quarrel with Seytoun, coloring it only so much as to make it appear that dueling was the accepted code in our army, and that the entire ostracising pressure of my late fellow officers had been put upon me to drive me into a corner from which there was no escape save in the course I had taken.

“You have conscientious scruples, Mr. Page?” he asked, after what seemed an interminable weighing and balancing of my tale.

“You may call them so, if you wish, Sir Henry,” I replied gravely. “I have no desire to kill or to be killed in such a cause. And since, if I had stayed, I should certainly have had to fight this Captain Seytoun, I put this with the other, and possibly better, reason, and crossed the lines.”

“And that other reason?” he questioned shrewdly. “Speak plainly, Mr. Page. You stand upon the dividing line between some honorable occupation with us on one hand, and the prison hulks on the other.”

[46]I saw that my excuse was not big enough, and tremblingly tore another page out of the book of truth.

“I am ashamed to tell you of the other reason, Sir Henry,” I demurred, with as near the proper shade of wounded self-esteem as I could simulate. “It touches me very nearly, and in a tender spot. You know, without my telling of it, how we Pages, my father’s family, have given everything to the cause which is even now tipping in the balance of defeat?”

“I do know it,” he replied, somewhat grimly I thought.

“With that in view, Sir Henry, imagine my feelings as a gentleman and an officer when proposals were made to me involving a complete and entire surrender of all that a man of honor may be supposed to hold most dear. Do you wonder, sir, that I have thrown myself into the arms of a generous and high-minded enemy?”

“Ha!” said he, relaxing the hold of the freezing stare for the first time in the interview. “They wished you to turn spy, did they? Mr. Page, I thoroughly applaud your courage and resolution, as well as your frankness in telling me this. Not many men in your situation would have dared to do it. But I have long suspected Mr. Washington and his advisers on this score. It is the least honorable part of their stubborn resistance to their king.”

I should have laughed outright if I had had liberty. This from the man, mind you, who had corresponded secretly for months with Benedict Arnold,[47] bribing, suborning and finally protecting the traitor; the man who had sent the brave Major André, his own adjutant-general, into our lines, if not as a spy, at least as a go-between to treat with our Judas of West Point!

“As you say, Sir Henry, it is the least honorable part of warfare,” I agreed mildly, fearful now lest, my case being safely made, I should say too much.

But Sir Henry would not let it rest at that.

“It is greatly to your credit that you were courageous enough to refuse, Mr. Page,” he went on, taking, as I meant he should, my refusal for granted. And then, as if upon a premeditated thought: “Are you acquainted with Mr. Arnold?”

I said I was not; that my arm of the service, the horse, had never chanced to be under his command.

The commander-in-chief found a pen and quickly wrote me a note.

“Take that to Mr. Arnold,” he said almost graciously. “He lodges next door, and his hour is nine o’clock.” And, as I was bowing myself out: “Stay, Mr. Page; shall I give you an introduction to the pay-master?—for present necessities?”

I understood this to be an offer to pay, not for my allegiance, but for the information he had—or thought he had—of me, and I declined as delicately as I could, saying that a soldier’s wants were few, and that I had taken the precaution to provide for myself out of my private funds. This seemed to please him still more, and, on the whole, the Sir Henry Clinton who bade me an affable “Good morning” was greatly[48] less alarming and formidable than had been the one who had gripped me so chillingly in his stony stare while Lieutenant Castner was presenting me.

Castner was waiting for me in the ante-room, as I found, but this time only to pass me beyond the sentry at the door. The fact that I was allowed to depart unhindered seemed to be a sufficient guaranty that I had satisfied his chief; but I owe it to the young aide to say that his manner to me now was neither more nor less cordial than it had been over the ham and eggs in our breakfast tavern.

Having thus crossed my Rubicon, and, as one may say, burned my boats behind me, the next thing was to find Champe and to put that ferocious patriot on a proper footing with me. But first I had to get rid of my uniform as a captain of Baylor’s Horse, and here Castner served me again, quite willingly, going with me to a shop north of the burned region and knocking the sleepy proprietor out of his morning nap to wait on me.

Though I had said that I did not know Arnold personally, I knew enough of him and of his foppish taste in dress to make me drive a gentleman’s bargain with the shop-keeper; and when I was arrayed like the lilies of the field in such ready-made finery as I could purchase, Castner looked me up and down approvingly, and swore it was a pity I had ever forsaken my proper garmenting to don the coarse homespun which we officers of Baylor’s Horse made it a point of honor to wear.

By the time my bargaining was done, it was too[49] late to go in search of Champe if I were to take Sir Henry Clinton’s nine o’clock hint pointing to Arnold. So, rather against my better judgment, I faced southward with Castner again, giving our Judas the preference over the worthy sergeant-major—a mistake which was to carry heavier consequences than I ever dreamed could cluster upon so small a pin-point.

NOTWITHSTANDING Sir Henry Clinton’s voucher for Benedict Arnold’s receiving hour, we found the man, Castner and I, on his door-step and apparently just going out, as we came up.

I expected Castner to introduce me at least, but here I had my first hint of Arnold’s standing, or rather his lack of standing, with the British officers, which was pointed by the lieutenant striding on with his head in the air, and leaving me abruptly to my own devices.

Since boldness was the only word I knew, or could know, in all this business, I ran up the steps, struck my hat to the man I hoped to see well hanged, and gave him General Clinton’s note. While he was reading the scrawl—the British knight wrote a most fearful and wonderful hand—I had time to observe how a few short weeks had changed the traitor.

Always a handsome man, with a clear transparent skin, intellectual features, thin nostrils well recurved and sensitive to every changing mood, and eyes that were almost womanish for size and for a certain languorous sensuousness, he might still have sat for the portrait of that Benedict Arnold who had braved the[51] wrath of General Gates to save the day at the second battle of Stillwater. Yet there was a striking change, apparent even to one who had seen him as seldom as I had. The lips were set in thinner lines, the eyes were gloomy, and, when he turned them upon me, I saw a lurking devil of sullen suspicion in them. Also the deep furrows in his brow had grown still more marked and they had taken an upward and outward curve like the suggestion of a pair of horns.

None the less, his reception of me was bland and cordial, made with a half-offering of his hand, which, I am happy to say, I found it possible to seem to overlook.

“You are very welcome, Mr. Page,” he said, smiling with his lips and at the same time probing me with the eyes of gloomy distrust. “Sir Henry Clinton says kind things of you here”—waving the letter—“and I trust we shall go on to a better acquaintance.” Then, a little doubtfully: “Should I be able to place you more nearly?”

I told him I thought not; that I had probably seen him oftener than he had me. Then I added the bold word which has slain many a better man—the word of open flattery.

“Like many another who knows you even less well than I do, Mr. Arnold, I owe you a debt of gratitude. But for your courageous example, not a few men who are now faithfully serving the king would still be in Mr. Washington’s riff-raff army, fighting for that jack-o’-lantern thing called liberty. And, but for that same act of yours, I can most truthfully say that I[52] should not be here this morning, trespassing on your good nature, sir.”

It was very gross, and I do think Mr. Dick Sheridan himself could not have made the doubl’ entendre more dramatic. Yet this gentlemanly turncoat, whose vanity was even greater than his villainy, gulped it down as I have seen our good Dominie Attlethorpe, of Williamsburg, swallow a luscious oyster.

“You are either the most astute of young scapegraces, or the kindliest, Mr. Page,” he retorted, with the moral glutton’s satisfaction in every intonation. And then: “Have you breakfasted, sir?”

I told him I had; whereupon he asked me to walk with him, saying that we could come at my business as well in that way as in any other, if I would so far indulge him.

I laughed in my sleeve, and gave him the wall, as a poor dependent on his bounty should; and, reckoning again without my host, wondered how long it would take poor Champe to get within such easy gripping distance of his quarry. As we passed northward and eastward, quite to the other side of the town, and well beyond the burned area Arnold put me through my deserter’s catechism, which now, since I had danced through it gaily once for Castner, and again for Sir Henry, came off the tongue as glibly as a schoolboy’s lesson.

It was in front of a rather stately house facing an open space that we paused finally, and I saw a woman come and open the door and close it again quickly when she saw there were two of us. I had but a[53] glimpse of the woman’s face, but that was enough. No one who had ever seen Margaret Shippen would fail to recognize her even though she appeared, as she did to me in that door-opening glimpse, in the guise of a sweet young woman prematurely saddened and aged by sorrow unnamable.

But another thing I saw which disturbed me even more than the sight of poor Peggy Shippen’s face; disturbed me so greatly that I scarcely heard the traitor’s question which gave me the opportunity I had been flattering him for. The distracting thing was a fleeting glimpse of another fair face at an upper window of the house; a clean-cut profile appearing for a single instant behind the leaded panes, and then vanishing so quickly that I began to doubt that it had been there. Now I could have sworn upon a stack of Bibles that there was only one face in all the world that could have flung that profile outline upon any window that was ever glazed, and that face I had left safely behind me in Virginia.

Could it be possible—but no, it was only a fancied resemblance, I told myself; and then I flogged my wits into line again in time to answer Arnold’s leave-taking query that had been all but lost in the sudden jangle of emotions.

“What can you do for me, Mr. Arnold?” I echoed. “That is for you to determine. From what Sir Henry Clinton said, or rather hinted at, I hoped you might be able to make use of me in some way. But I shall be at my best if you keep me near your person, sir. Of that I am very sure.”

[54]Again he swallowed the bait like a greedy gudgeon.

“You shall come to me at my headquarters this afternoon, Mr. Page,” he said, with the air of one of the great ones of earth dealing out largesse to a reverent and admiring vassal; and then he ascended the steps and the door was opened quickly for him by the woman who stood inside.

Some things were made plain to me on my chilly walk back to the southward, with its opportunity for quiet reflection. One was that I had not overrated Arnold’s appetite for flattery, which was in truth even grosser than I had imagined. Another developed out of the side-glimpse given me of the traitor’s domestic affairs. It was not passing strange that Arnold should not wish to have his family with him in the house in the lower town where, as Castner had told me, he ate and slept and had his regimental rendezvous. But I saw more than disinclination in the town-wide severing. It spoke eloquently of the traitor’s social isolation that Arnold should be only a daylight visitor at the house where his wife and child were, without doubt, the guests of family friends of the Shippens.

I was wondering upon what footing he stood in this house, and if he were only tolerated there as he seemed to be elsewhere, when the recollection of the face I had seen at the upper window came to haunt and perplex me again. My last letter from Beatrix Leigh had pictured her hived up in the great house at Sevenoaks, in County Warwick, her father and brothers[55] gone to the south with General Greene,—in whose campaign against Cornwallis she was patently more interested than she was in our humdrum New York fuse-sputterings,—and her mother and all the other women-folk of the tidewater homeland shuddering in anticipation of the long-threatened descent of the British upon the Virginia coast.

She had given me no hint of any intended desertion of Sevenoaks, and though she had many friends in Philadelphia, where her schooling had been, I thought it the height of improbability that she would get even that far on the way to New York in these troublous times. Weighing all these things in the mental balance, I saw how absurd it was to let a momentary sight of a beautiful face at a window run me so far aside from the beaten path of calm reasoning. In sober fact the fancied identification proved nothing but this: that Beatrix Leigh’s face was so constantly present in my mind and heart that I was ready to find and adore it under any suggestive guise.