Title: The Review, Vol. 1, No. 11, November 1911

Author: Various

Publisher: National Prisoners' Aid Association

Release date: January 30, 2023 [eBook #69908]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: National Prisoners' Aid Association, 1913

Credits: Bob Taylor and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

[Pg 1]

VOLUME I, No. 11.

NOVEMBER, 1911

A MONTHLY PERIODICAL, PUBLISHED BY THE

NATIONAL PRISONERS’ AID ASSOCIATION

AT 135 EAST 15th STREET, NEW YORK CITY.

TEN CENTS A COPY. ONE DOLLAR A YEAR

| T. F. Carver, President. | F. Emory Lyon, Member Ex. Committee. | E. A. Fredenhagen, Member Ex. Committee. |

| Wm. F. French, Vice President. | W. G. McClaren, Member Ex. Committee. | Joseph P. Byers, Member Ex. Committee. |

| O. F. Lewis, Secretary, Treasurer and Editor Review. | A. H. Votaw, Member Ex. Committee. | R. B. McCord, Member Ex. Committee. |

| Edward Fielding, Chairman Ex. Committee. |

By Eugene Smith

President Prison Association of New York

[Mr. Smith read a very carefully prepared paper on the above subject at the Omaha meeting of the American Prison Association. The Review would gladly print the address in full but space admits only of certain abstracts, which follow.—Editor]

In the deplorable and chaotic condition of the very sources from which all statistical matter must be drawn, it is hopeless to look for any improvement in our census statistics, unless a radical change can be effected in state administration. The records of the police, the courts, the prisons, can be made of statistical value only by the action of the state itself; and there is apparent but one method by which the state can act to this end.

There should be established in each state a permanent board or bureau of criminal statistics, whether as an independent body or as a department of the office of the attorney general or of the secretary of state. This bureau should be charged with the duty of prescribing the forms in which the records of all criminal courts, police boards and prisons shall be kept and specifying the items regarding which entries shall be made. The law creating the bureau should direct that the forms prescribed by it should be uniform as to all institutions of the same class to which they respectively apply and be binding upon all institutions within the state.

The bureau should issue general instructions governing the collection and verification of the facts to be stated in the record; it should also be its duty, and it should be vested with power, to inspect and supervise the records and to enforce compliance with its requirements. Such a bureau might secure a collection of reliable statistical matter, uniform in quality throughout the state. Indiana is now, it is believed, the only state in the Union where such a bureau exists.

But even this result is not enough. Supposing all the criminal records within each separate state to be made uniform without the state, still they would not be available for comparison or for the purposes of a national census, unless all the states could be brought to adopt the same form and method, so that all criminal records throughout the Union could be kept upon one uniform plan. Here we encounter a serious obstacle. The diversity and conflict of state laws are crying evils of our time, universally recognized and denounced, and yet the most strenuous efforts to bring about harmonious action between the legislatures of separate states have always failed. No single statute, however skilfully drawn, proposed for universal acceptance has ever yet been adopted by all the states[Pg 2] of the Union. Still the states must act in unison upon this matter of uniform criminal records or else our statistics of crime must continue to be a national failure and a national reproach.

Not the slightest reflection can be cast upon the federal census bureau; on the contrary, when consideration is taken of the fragmentary and chaotic state records with which the census bureau had to deal, the systematic and orderly results and the general deductions embraced in the census report of 1904 must be regarded as a signal scientific triumph.

Uniformity in criminal records throughout the Union we have seen to be an imperative need. Is it a visionary ideal, impossible of attainment? If there is any means through which the ideal can be realized, it is through the agency of state bureaus of criminal statistics, such as have just been suggested. Each of these state bureaus, in preparing uniform plans and forms for its own state, would naturally place itself in touch with the national census bureau; while the national bureau would not be legally vested with the slightest power to dictate to the state bureau or to direct its action, practically its wide experience and grasp of the entire situation would enable the federal bureau to wield commanding influence in shaping the action of every state bureau. If the creation of efficient state bureaus, of the kind indicated, in the several states could only be secured, it is not chimerical to believe that through the dominating influence of the federal census bureau, tactfully exerted, a uniform system of statistical records relating to crime could ultimately be established throughout the United States. It is the first step that counts. If a few of the leading states in the Union could be induced to establish such a bureau; if to Indiana could be added New York, Illinois, Nebraska, and in the South Virginia, the force of example would be potent in the sister states. * * *

One exceedingly common and popular error needs special mention; a marked increase in the number of convictions for crime indicates to the public mind an increase necessarily in the volume of crime committed. In fact, it may be owing to increased activity and efficiency on the part of the police and detective officers, to greater severity and thoroughness in the administration of the courts, to a change in the economic conditions of the community, to diminished care and skill on the part of offenders in escaping detection; indeed, there are many possible factors that may have combined to produce an unusual statistical result. A slight change in the laws or methods of procedure, may cause startling statistical fluctuations.

For example, in the year 1890, the number of convictions for drunkenness in Massachusetts was 25,582; two years later, the number had fallen to 8,634. An amazing diminution of drunkenness in Massachusetts—nearly 70%? Not at all; it was owing to a new statute passed in 1891, the effect of which was that only those arrested for the third time within a year were subject to conviction.

The congestion of population in cities and the progress of invention necessitates every year the enactment of numerous statutes and municipal ordinances making certain acts, that are harmful to the public, misdemeanors (that is, legally crimes); but these acts, committed in large part through ignorance or negligence, are not essentially of a criminal nature. Statistically, they swell the number of crimes committed, but most of them are not crimes in the meaning popularly attached to that word. These considerations suggest that all attempts to draw conclusions from, and to explain the significance of the rise or fall of the statistical barometer must be conducted with extreme caution.

An error into which speakers and writers upon crime are prone to fall is that of regarding the statistics of crime as a measure of the total volume of crime committed in the country, affording an answer to the vital question: Is crime increasing? There are two fundamental facts relating to crime that must never be forgotten. First, that criminal statistics are, and must necessarily always be, confined to those crimes that are known and are officially acted upon by the police or the courts. Secondly, that there is a large number of crimes that are committed secretly and are never divulged, the perpetrators of which are[Pg 3] never detected, and crimes that never result in the apprehension of the offender.

The crimes of this second class cannot possibly enter into any criminal statistics and yet they form a very large part of the total volume of crime committed. It does not seem to be commonly appreciated that these unpublished, unpunished crimes, which can never be included in any criminal statistics, probably far exceed in number those that are followed by conviction and punishment. * * *

In addition to unpublished crimes, there are numerous cases where crime is committed and reported to the police, but proceed no further. In these instances, the offender may be known, but has escaped or the offender is unknown and eludes detection; in either case there is no conviction and the crime remains unpunished. * * *

Perhaps the highest value of criminal statistics consists in the light they may throw upon the practical effects produced by penal legislation, by judicial procedure and by the administration of police and detective officers. For example, within the past decade, radical changes in the administration of justice have been established in this country by laws relating to juvenile offenders, and by the extended use of the suspended sentence and probation. A question has arisen in many minds whether the severity of the penal law has not thus been unduly relaxed. It is a matter of supreme importance to know whether and how far, the tenderness of the modern law toward children serves to rescue them from a life of crime—to know whether the clemency of the law toward adults by suspension of sentence and probation promotes their rehabilitation, and to know to what class of offenders this clemency may properly be extended—to know whether these milder methods of treatment are affording adequate protection to the public or whether sterner measures of restraint and discipline may be made more effective in repressing crime.

These vital questions can receive final answer only by following the subsequent career of the offenders to whom these methods are applied and thus gaining data for statistical tabulation. In the same way, the virtue of the indeterminate sentence ought to be substantiated by the statistical test. Statistics can be made to show what class of crimes comes most frequently before the courts in a given community, and whether an increase in the severity of punishment tends to increase or diminish the number of convictions.

A movement is now in progress which may greatly widen the scope of criminal statistics. It has long been realized that many persons sentenced for crime are feeble-minded and seriously defective; mentally and physically but, within the past few years, the conviction has been growing that our penal system is radically imperfect in that it provides no adequate means for deciding whether or not a person on trial for crime is really responsible criminally. * * *

[In the current annual report of the Minister of Justice as to the penitentiaries of Canada, appears an interesting account, partly historical, of the Canadian parole system. We print portions of the report.]

Adult criminals seem to have been under a “ticket of leave” system in England, as far back as the year 1666, in the reign of Charles II, when a statute was passed, giving judges power of sentencing offenders to “transportation to any of His Majesty’s dominions in North America.” This authority was re-affirmed by another statute passed in the year 1718, during the reign of Charles I. In England and France, at that time, adult criminals, also juvenile or minor offenders, were placed on a sort of parole, and given over to societies, or orders, for supervision, while the state still held custody of them, which custody was relaxed as the good effects of their being thus placed became more apparent. The ticket of leave system grew out of the transportation of criminals by England to her colonial possessions. Transportation ceased temporarily in[Pg 4] 1775, because of the war with her American colonies, but it was revived in 1786, and a consignment of convicts was also sent in this year to New South Wales.

The control of this colony was not regulated by statute, but was left to the wisdom of the colonial governor. The necessity of raising crops for their sustenance, the construction of buildings, and the making of homes for the colonists, induced the governor greatly to modify the sentences of the well-disposed prisoners, that he might have a needed moral and possibly a physical support from them in his administration. He set many of them free, and gave them grants of land, and afterwards assigned to these men, thus free, other convict laborers who were being received from the mother country. Following this precedent it became the custom for the governors of different penal settlements to manage each according to his own ideas, and the custom developed into granting such liberties as have been included in the ticket of leave system.

The holder of the ticket of leave, which was granted to the convict who had satisfactorily fulfilled a certain period of his sentence in the cellular prisons then adopted in the penal settlements, would be granted the freedom of the colony during the remainder of his sentence, but he was placed under certain restrictions, such as being confined to certain districts unless he received a pass to go elsewhere, and also being obliged to present himself for inspection to the authorities monthly, quarterly or yearly, as provided for in his license, and being prohibited from carrying fire-arms or weapons of any kind, except under special permission. The ticket of leave was first legalized during the reign of George IV, between 1820 and 1830, and in 1834 it was regulated by a statute, which defined the minimum periods of sentence by which a ticket of leave could be gained. For example, it required a service of four years for a seven year sentence, six years for a sentence of eight, and fourteen years for a life sentence, in what was termed “assigned service or government employed.” These periods could be increased by the slightest misconduct on the part of the prisoner.

Under this law a convict who had held a ticket of leave without having been guilty of misconduct, and who was recommended by responsible persons in the district where he resided, could have his application for a full pardon transferred by the governor of the colony for the consideration of the Crown, but Sir Robert Burke, in a report made by him in 1838, intimates that convicts were granted ticket of leave to some extent at the discretion of the home government upon application of influential persons in England. Under this system the convict on ticket of leave was entitled to his earnings. In case of misconduct, the employer could complain to the nearest magistrate, who could order the convict to be flogged, condemned to work on the roads, or in the chain gang. Any magistrate could order 150 lashes, until the year 1858, when the number was limited to 50. A convict, if ill-treated, might lay a complaint against his master, but for that purpose he must go before a bench of magistrates, the majority of whom were owners of convict labor and masters of assigned convict servants. Such abuses grew up under this system as to make life a living hell for the convicts.

In the year 1838 a committee of parliament condemned the system of transportation, with its attached evils, as “being unequal, without terrors to the criminal classes, corrupting both the criminal and colonists, and very expensive.” They recommended the establishment of penitentiaries instead. It was then ordered that no convicts should be assigned for domestic service, and in the year 1840 transportation to Australia was stopped entirely.

Another advance was made in the year 1842, which was called the “probation system.” It was founded on the idea of passing convicts through various stages of control and discipline, by which it was hoped to instill a more progressive system for their improvement. Probation gangs were established in Van Dieman’s Land, through which all convicts for transportation were to pass. These gangs were scattered through the colony, and were employed on public works under the control of the government. A school master or a clergyman was to be attached[Pg 5] to each gang. From the probation gang, the convict passed into a stage during which he might, with the consent of the governor, engage in private service for wages, but he was required to pay the government a part of the wages, which was retained as security, and forfeited if the convict was guilty of any misconduct. Next followed a ticket of leave with the same privileges, save that the freedom of the convict was greatly enlarged. The last stage was that of a conditional pardon. This probation system failed, as Sir Edmond Ducaine stated, for several reasons: 1st—that suitable means were not provided for insuring proper order or discipline in the probation gang; 2nd—that the officers of the gangs were characterized by insubordination and vices, unnatural crimes being proven to exist to a terrible extent; 3rd—that the demand for labor was found to be very insufficient to employ the ticket of leave portion of the men, so that idleness soon destroyed all the good that had been accomplished under the probation system. The difficulty may be summed up in one or two words—they did not get to the root of the matter as regards discipline and labor, and there was an entire absence of mental and moral training.

In the year 1846, Mr. Gladstone decided that all transportation of convicts to the outside colonies must be suspended, and in 1847 the present system of imprisonment was adopted, under which convicts must pass through the prisons before a conditional release will be granted. Under the present system of penal servitude in England, there are three distinct stages of operation. During the first, which generally lasts nine months, recently greatly reduced in number, the prisoner passes his whole time, except meetings and exercise, in his cell apart from all other prisoners, working at some employment, but always kept separate and alone. During the second stage he eats and sleeps in his cell, but works in association with other prisoners. During the third period he is conditionally released, but is kept under the surveillance of the police, reports at stated periods, and is returned to prison for any infraction of his licence. The system is altogether automatic in its operation, and as far as I can ascertain about one-half of the entire number released on ticket of leave, lapse into crime again.

The “Prevention of Crimes Act” passed in 1871 provides that any person convicted a second time of an indictable offence may be sentenced to be subject to the supervision of the police for seven years after the expiration of his sentence.

The system of conditional liberation was adopted by the king of Saxony, in 1862. In the same year it was adopted by the grand duchy of Oldenburg, by the Canton of Sargovie in Switzerland, in 1868; the kingdom of Servia, in 1869, the German Empire, in 1871, Denmark, in 1879; the Swiss Canton of Vaud, in 1875, also in the same year, the Kingdom of Croatia in Hungary, the Canton of Unter Walden, in 1878, the Netherlands, in 1881, the Empire of Japan, in 1882, the French Republic in 1885, and since these dates it has been adopted in Austria, Italy and Portugal. The system of parole, or conditional liberation, is also now in vogue in many of the United States.

The Canadian parole system, first adopted for the penitentiaries in the year 1899, and since extended to the jails and reformatories, differs from any system now in operation in the entire world, and will compare favorably with any of them. There is nothing automatic in the operation of this system, and it does not conflict with the remission earned in the penitentiaries, which applies to all prisoners whose conduct and industry merit consideration.

What, then, is the parole system? I do not like the general term “ticket of leave,” which has been the outcome of many failures, and resulted in the abuse of many systems, for the term ticket of leave is one which handicaps the prisoner who carries this synonym of “jail bird” printed in large letters on his license, but the word parole, “my word of honor,” is a much better term, and more within the true meaning of a conditional release.

It can be said, in view of the various methods adopted in many countries, that these systems all acknowledge the principle[Pg 6] of conditional liberty to the citizen who has forfeited it by crime, and that a gradual restoration and rehabilitation is not only feasible, but is expedient to the higher and best interests of the state. It is a system which strengthens the weak, and fits them again for contact with society, and when they are sufficiently strong, restores them to full liberty and good citizenship. The parole system of Canada not only gives the released prisoner police supervision, which is an absolute necessity in keeping in touch with them, but it makes provision for a parole officer, as Sir Charles Fitzpatrick demonstrated to the house of parliament, as a “go-between” the police and the prisoner, giving the prisoner protection, sympathy and care in a time when he most needs a helping hand.

The parole system came in vogue in Canada under the late Honorable David Mills, then Minister of Justice, in the year 1899. He was followed by Sir Charles Fitzpatrick, who not only took a deep interest in the system, but he placed it on a well-organized plan of operation, and the present minister of justice, the Honorable A. B. Aylesworth, has been working out this organization with splendid success. The minister of justice occupies a unique position, having at his command the reports from the trial judges, the parole officer, the wardens and jailors of the institutions and the dominion police, for the investigation of complex cases. His position is a much stronger one than that of a “board of pardons,” or any local system operated in other countries, and it would be a step backward to even consider an alteration of our Canadian system. The minister of justice considers every application for a parole on its merits, and free from local prejudice or influence.

It has also been demonstrated that the Canadian parole system is working harmoniously with the principles of law and order in every community in which it is in operation, and that it has never been governed by that mawkish sentimentality which would convert a penitentiary into a summer resort, with perfumed baths, carpets, paintings, or orchestras for the prisoners. The administration realizes that the inmates are criminals, sentenced to confinement on account of crime, and to convert a penitentiary into a place of recreation and amusement would be to pervert the purposes for which it was instituted. In our Canadian institutions, men are punished for criminal offences, and on this fact or basis only the mercy of a parole can be safely administered. One fact I desire to lay stress upon is that our convicts receive a wholesome, humane treatment which leads to the beneficial results of our parole system.

As to the results of the parole system since 1899 in Canada, the following facts are quoted:

| Paroles granted from penitentiaries | 1,903 | |

| Paroles granted from prisons, jails and reformatories | 1,276 | |

| ———— | 3,079 | |

| Licenses cancelled | 103 | |

| Licenses forfeited | 62 | |

| ———— | 165 | |

| Sentences completed | 1,915 | |

| Still reporting | 999 | |

| ———— | 2,914 |

[From a leaflet just issued by the Massachusetts Prison Association we take the following facts:]

The Association was formed in 1899 to enlighten public opinion concerning the prevention and treatment of crime, to secure the improvement of penal legislation, and to aid released prisoners in living honorably. Until the Association was formed, there was no organization in the state to do the work of “enlightening public opinion concerning the prevention and treatment of crime.” The literature of the Association has been distributed widely for educational purposes. Its annual appeal for Prison Sunday has met with a response from many churches, and a greatly improved public sentiment has been developed. During 1910 the Association printed and distributed 75,000 pages of printed matter. The public press and the lecture platform has been used also.

[Pg 7]

Three important changes have been made through the efforts of the Association, in the probation laws. Arrested persons who, after investigation by the probation officer, are found to be occasional offenders, are released from the station, by his direction, with a warning that a record has been made, and that another offense may be followed by punishment, 38,813 being so released in 1910. Since the time available before the opening of the court does not permit a full investigation of all cases, doubtful ones are sent to the court which has authority to release the occasional offender without arraignment. The offender suffers from public exposure in court, but is saved from the stigma of a trial and conviction; 25,295 were so released in 1910.

Commitment to prison formerly followed immediately after the imposition of a fine, if it was not paid on the spot. A new law, secured by the Association, authorizes the court to give a prisoner time to get his fine. He is placed under the supervision of a probation officer, to whom he pays the fine. The receipts from fines collected last year under the suspended sentence amounted to $25,379.

In connection with the abolition or the establishment of correctional institutions, the Association has succeeded in bringing about the abolition of the South Boston house of correction, and the establishment of the Shirley state industrial school for boys, a reformatory on the farm school plan for boys between the ages of 15 and 18. Through the efforts of the Association probation officers have been appointed in the superior court. In 1906 the society played a prominent part in bringing about the treatment of juvenile offenders as delinquents rather than as criminals. Back in 1900 the Association advocated a bill, which was passed providing for a central probation bureau. Not until 1908, through another law, was the principle of this bill put into execution. The Association secured a law expediting criminal trials by giving the lower courts jurisdiction over a greater number of offenses.

Recently the society has secured the passage of a law requiring the state inspectors of health to make an annual inspection of police stations, lockups and houses of detention, and to make rules for such places, relative to the care and use of drinking cups, dishes, bedding and ventilation. The law requires that no such places shall be built, hereafter, until the plans have been approved by the state board. A supplementary law extended this provision to jails and houses of correction.

In the assisting of discharged prisoners the Association has often filled the place of next friend. In 1910 the Association gave relief to 335 different men. The receipts of the Association were in 1910 $3,682, and the expenditures, $3,678.

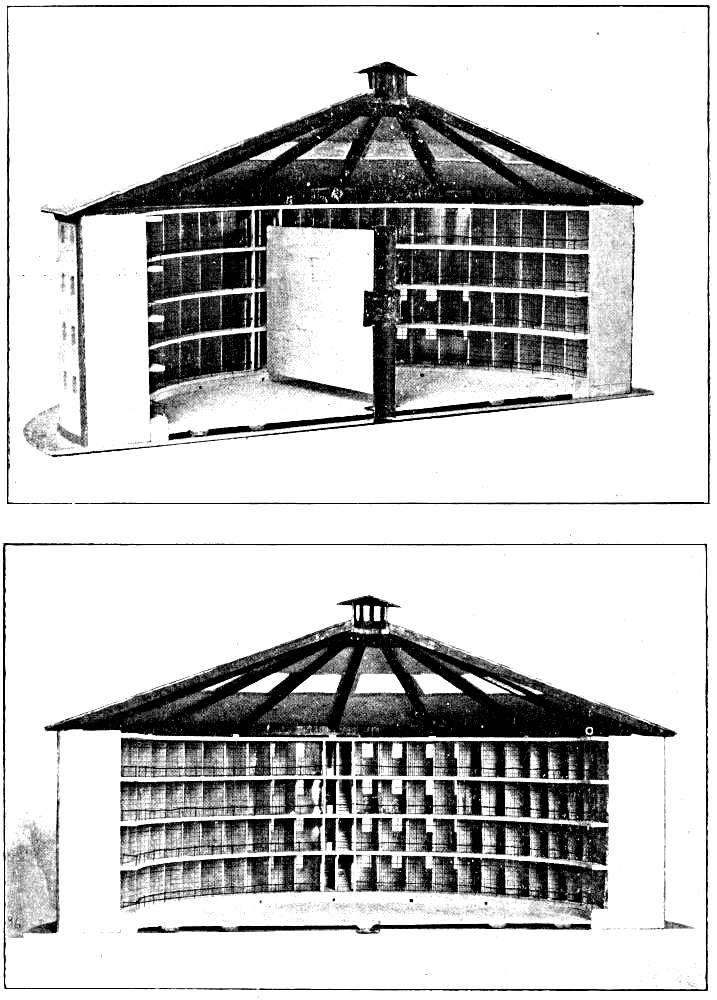

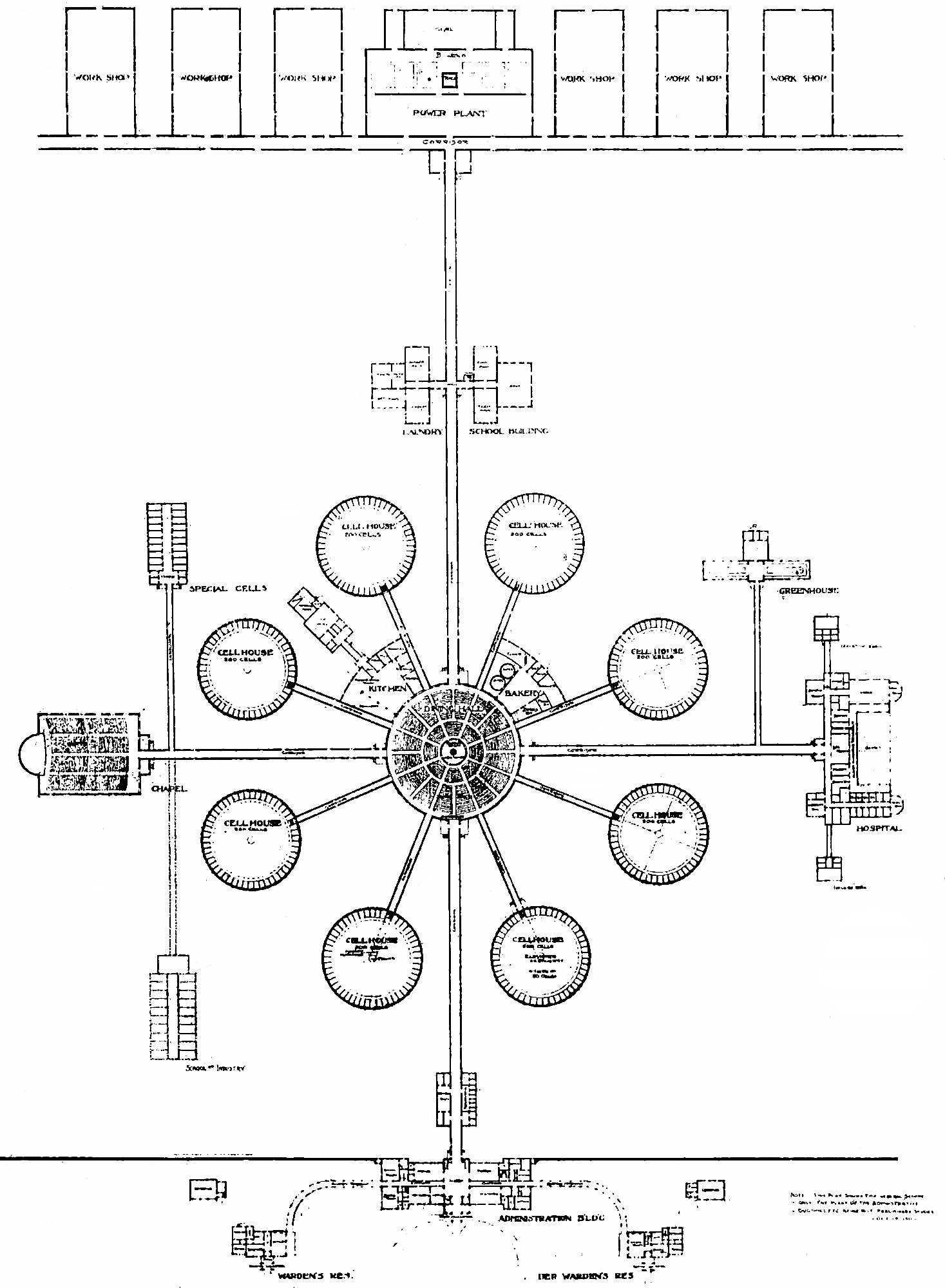

At the annual meeting of the American prison association at Omaha, Mr. W. C. Zimmerman, state architect of Illinois, presented to the careful scrutiny of most of the principal wardens in the United States a half-section model of the new cell house which is to be the unit of construction in the proposed Illinois state prison of which Mr. Zimmerman is the architect. In view of the novelty of the prison plan proposed by Mr. Zimmerman and in view furthermore of the general approval, often enthusiastic, which the wardens gave to the plan and the model, a brief description is submitted herewith to the readers of the Review.

At present the prevailing construction of cell blocks in the United States embodies the following features: (a) the walls of the building; (b) the corridor next the wall; (c) the cell blocks, which are back to back, except for the so-called utility corridor which separate the rows of cells. In short, it is a cell block built within a building known as the cell house. It is obvious that the natural light for the cells must come through windows in the wall of the building.

[Pg 8]

Half-section Model of Proposed Illinois State Prison Cell Houses. (See “A New Kind of Prison,” page 7)

[Pg 9]

European prison construction is the exact opposite, in that the cells are built on the “outside” principle, that is, up against the walls of the cell house. The corridor, therefore, is in the middle of the cell house and each cell has a room to itself with a barred window to the outside air.

The “inside” cell construction in the United States has been held to have several distinct advantages, for the utility corridor, containing the various pipes, wires, etc., is an economical form of construction. The cells on the “inside” are furthermore safer in that the cell door acts as a window and the prisoner in order to escape must first go through the cell door, then through the wall of the cell house and then over the wall of the prison grounds.

Plan of Proposed Illinois State Prison. (See “A New Kind of Prison,” page 7)

Prisons built on the “inside” plan are strongly criticised because of the limited amount of direct sunlight and direct fresh air that may be admitted to the cells. The importance of these two essentials of life is obvious. A further objection to the “inside” cell plan is that as the cells have no doors, the acts and the words of one prisoner can be readily heard or learned throughout a good part of the cell house. Supervision with either the “inside” or the “outside” plan is at present carried on through the patrolling of the corridors by a guard.

The plan evolved by Mr. Zimmerman for the cell house of the new Joliet prison[Pg 10] seemingly overcomes the above objections in a most careful manner. It is proposed by Mr. Zimmerman to build circular shaped cell houses about 120 feet in diameter, placing the cells against the cell house wall and thus assuring direct light and air. Now comes the novelty. Instead of having an open front of steel bars, heavy glass will be fitted into the open space between these bars so as to make a completely closed room out of the cell. A full view, however, of this room is possible from a central point. This central point is a steel shaft in the center of the cell house, enclosing a circular stairway. The stairway will be as high as the highest tier of cells, and from a position half way up the circular stairway, which is completely sheathed with steel, the guard within the “conning tower” has a full view of each and every cell, at the mere turn of his head. The shaft will be arranged with narrow slots opposite the level of the eye so that it will be impossible for inmates to see the guard and impossible to know at what time they are under observation. The shaft will be bullet proof, which in case of possible mutiny assures absolute safety for the guard. An armed guard could undoubtedly from his secure position readily control a mob even though the mob be fully armed. Entrance to the shaft will be possible only through a tunnel which opens into the administration building outside the prison enclosure.

A number of these circular cell houses will be erected as indicated in the group plan here published. That this arrangement lends itself most readily to extension is evident.

Another novel feature is the possibility of classification of prisoners in different groups. Easily moving partitions will be erected as high as the upper tier of rooms and placed with sufficient frequency so that no prisoner can see from his cell into that of any other cell, an arrangement which does not interfere with the view of the guard in the “conning tower” into any room of the cell house.

Escape seems practically impossible, for the guard in the “conning tower” will have at his hand a complete system of levers, push buttons, etc., electrically controlled in such a way that at any time the locks of any or all of the tiers may be locked or unlocked and the lights in any or all of the cells may be dimmed or increased.

In order that all rooms may obtain direct sunlight the roof will be made largely of glass and the diameter of the cell house is sufficiently large to admit of the shining of the sun into the lowest tier of rooms facing the north. Most of the rooms will enjoy direct sunlight at some period of the day through the outside window.

The building of this prison in Illinois will be watched with great interest by all those in the United States interested in the construction of prisons and in the proper housing of the delinquent. The circular form of prison is not entirely new. In 1901 a circular prison was built in Haarlem, Holland, to accommodate about 400 inmates. The Haarlem prison, however, has wooden doors for each cell which renders the supervision of the prisoners much more difficult. The specially new features of Mr. Zimmerman’s plan are the glass inside front, the circular form of construction, the central stairway with its “conning tower,” the partition providing for the obstruction of vision, for the classification of prisoners and the elimination of a number of the attendants otherwise needed for supervision. Mr. Zimmerman believes that this cell house can be built for ten per cent. less than the familiar rectangular cell block.

The first annual meeting of the National Prisoners’ Aid Association was held at Omaha, Nebraska, on Monday, October 16, while the members of the Association were in attendance upon the American Prison Association annual meeting in that city. That the National Prisoners’ Aid Association meeting was encouraging to its members there can be no doubt. In fact two meetings were[Pg 11] held, one an adjourned meeting. At each meeting from 30 to 40 members were present.

In a report sent out by the secretary to the various prisoners’ aid societies in the United States, the following paragraphs occur:

Vice President F. Emory Lyon was in the chair. After Mr. Lyon had stated the purpose of the annual meeting and had outlined briefly the history of the Association, the Secretary, O. F. Lewis of New York, was asked to report. The main business presented by Mr. Lewis was the question of the publication of the Review, a monthly periodical of sixteen or more pages, which has been published since January, 1911, in the interest of the National Prisoners’ Aid Association by Mr. Lewis as editor.

Mr. Lewis showed that the receipts of the Review had been up to the 6th of October $503.67, that the disbursements for the same period had been $445.97, leaving a balance of $57.70 in the treasury; that the principal items had been

| Printing the Review | $388.82 |

| Postage | 46.50 |

| Other expenses | 10.65 |

| ————— | |

| $445.97 |

Mr. Lewis then raised the question of the continuance of the publication of the Review. The expression was unanimous that the Review was a useful paper and should be continued and developed; that the affiliating societies should so far as possible obtain contributions and raise their own contributions to the Review; that the Review should be continued to be published by Mr. Lewis; that the affiliating societies should furnish more information for the Review than during the last year. Mr. Lewis on his part stated that he would gladly continue to be editor of the Review and would do what he could to obtain further contributions in New York and vicinity.

The meeting then proceeded to consider the nomination and election of officers for the ensuing year. After a frank and sincere discussion as to the proportional representation on the board of officers and executive committee of the various associations represented in the national association, it was voted on motion of Mr. Lewis that a nominating committee of five be appointed from the floor and the following persons were named:

Mr. Parsons of Minnesota, Mr. Lewis of New York, Mr. Cornwall of Massachusetts, Mr. McClaren of Oregon and Mr. Messlein of Illinois.

The meeting was then adjourned until 5.30 of the same date.

The adjourned meeting of the National Prisoners’ Aid Association was held at 5.30 P. M., October 16, 1911, at the Hotel Rome, Omaha. Vice President Lyon in the chair.

The nominating committee brought in the following list of officers and executive committee for election: President: Judge Carver of Topeka, Kansas; Vice President: William R. French of Chicago; Secretary and Treasurer: O. F. Lewis of New York; Executive Committee: General Edward Fielding, Chicago; F. Emory Lyon, Chicago; E. A. Fredenhagen, Kansas City; Joseph P. Byers, Newark, N. J.; W. G. McClaren, Portland, Oregon; R. B. McCord, Atlanta. Georgia; and A. H. Votaw, Philadelphia, Pa.

On motion of Mr. Fredenhagen, the above persons were elected officers and members of the executive committee respectively.

A brief discussion followed on methods of supporting the Review.

It was voted that the executive committee of the National Prisoners’ Aid Association should in their discretion ask of the American Prison Association that the National Prisoners’ Aid Association be recognized as a section of the American Prison Association, and that it should have on the program of the 1912 American Prison Association one of the sessions.

Adjourned at 6:30 P. M.

[Pg 12]

The city of New York has taken initial steps to make more adequate provision for dealing with inebriates and persons arrested for public intoxication. Following the enactment of a law authorizing the city to establish such a board, the board of estimate and apportionment of the city appointed a special committee to inquire into the feasibility and advisability of undertaking such a work. As a result of the report of the committee the board of estimate and apportionment decided to initiate the work. In accordance with provisions of the law, the mayor appointed a board of five members. The commissioner of public charities and the commissioner of correction are ex-officio members of the board.

This board has started its preliminary work. Possible sites for institutions have been studied and a request for funds for carrying on the work of the board has been made to the city authorities. In the budget for the coming year, provision is made for a sufficient amount of money for the board to secure a secretary and necessary office assistance. The appointment of a secretary, who can give his whole time to the work, will enable the board to study the problem further and formulate more in detail their plans and present them to the city for its ratification by providing the necessary funds for carrying them out.

This board has been established to do a most important piece of work. It will provide not only a hospital and industrial colony for the care of inebriates, but will establish under its jurisdiction a system of special probation work for cases of intoxication. The work of the board will doubtless be watched by persons interested in this work all over the country. A measure similar to the New York city law, giving authority to any city of the first or second class in the state of New York to make provision for the care and treatment of inebriates, was enacted at the last session of the legislature, and a committee has been formed in the city of Buffalo to secure the adoption of the plan in that city.

[Under this heading will appear each month numerous paragraphs of general interest, relating to the prison field and the treatment of the delinquent.]

The American Prison Association.—Under the title, “The Problem of Prisons.” the Outlook describes thus the recent annual meeting:

“A noteworthy interest in the proper employment of the prisoners in American prisons, reformatories, and jails was the keynote of the annual congress of the American prison association held recently at Omaha. This interest resulted in the appointment of a special committee, in which the name of the president of the American federation of labor is found among others, to investigate thoroughly prison labor conditions in this country and to report recommendations at the next year’s congress in Baltimore as to the best labor methods to be pursued in the correctional institutions of the various states. No more far-reaching action has been taken by the American prison association in the last decade. The sessions of the Omaha congress teemed with aspects of the labor problem. From New Zealand the success of reforestation by prisoners was reported: from Toronto, the remarkable working of convicts on a wide prison farm without armed guards. From the District of Columbia came reports of several successful years of collection of important sums from convicted offenders on probation, for the benefit and support of their families. Colorado has built almost half a hundred miles of state road by prisoners in the open, and other states have emulated the record. The congress was permeated with the feeling that prisoners should be steadily and[Pg 13] profitably employed, not exploited by state or corporation or individual, and that so far as possible the families of prisoners should receive some portion of their earnings. Two other currents were strongly felt: one for the rational development of recreation in correctional institutions, the other for the more careful study of the mental and physical condition of each inmate. Baseball, lectures, concerts, prison schools, and other educational features were warmly advocated. Outdoor sports on a week-end half-day were held to be not only a valuable ‘exhaust pipe’ for pent-up spirits and emotions developed in a necessarily abnormal condition of living, but also a distinct part of the plan of re-creation that is a prominent purpose of imprisonment. As to mental and physical defectives, the testimony of specialists was strong, not only that a considerable percentage of prison inmates are mentally backward and deficient, thus requiring special treatment rather than ordinary prison discipline, but that many industrial and living conditions, in which offenders, young and old, have found themselves, tend predominantly to crime. In several sessions emphasis was laid also on the deplorable absence of statistics regarding crime in the United States, it being shown to be impossible to-day to tell whether crime is increasing or decreasing or what the general results of imprisonment in prisons or reformatories are. Encouraging indeed was the frank introspection that the prison wardens and boards of managers gave to this and their own work. Of special interest was the report of Attorney-General Wickersham on the success up to the present time of the parole system for United States prisoners, who now may be paroled, if first offenders, at the end of a third of the maximum term of their imprisonment, by the action of a board of parole consisting of the warden of the penitentiary in which the prisoner is confined and representatives of the Federal department of justice. The Attorney-General advocated the extension of the parole system to cover the cases of life prisoners, details of administration of which would naturally be worked out in legislation.”

The following officers were chosen:

President—Frederick G. Pettigrove, Boston.

General Secretary—Joseph P. Byers, Newark, N. J.

Financial Secretary—H. H. Shirer, Columbus, Ohio.

Treasurer—Frederick H. Mills, New York city.

Convicts on Roads.—Warden Wolfer of the Minnesota state prison is quoted in the Des Moines, Iowa, Capital as follows:

“The use of convicts in building roads is wrong in principle. In the first place the sight of convicts upon the public highways has a detrimental effect upon the young people, it is apt to inspire in them any but the purest of thoughts. But the worst effect is upon the convict himself. He is subject to public shame and humiliation, and if he is making an effort to reform, he becomes easily discouraged. I have no objection to preparing the stone and other materials for road building by the prisoners, provided it is done within the prison walls. The talk that the use of convicts upon the highway will eliminate the conflict between convict labor and free labor does not prove out. The exhibition of the convict upon the highway only tends to aggravate the conflict, as it gives the lazy free laborer a chance to claim that he would work on the roads if it wasn’t for the convict. It is too expensive a method of road building.”

The Occoquan Workhouse.—The entire supervision of the District of Columbia workhouse at Occoquan probably will soon be given to the Board of Charities. Under the law charitable, correctional, and penal institutions in the District come under the board’s supervision. The workhouse will, it is believed, shortly emerge from the engineering stage and be ready to pass under the control of the board, as is the jail at present.

[Pg 14]

Grim Humor.—The Germans describe that grim humor that emanates from cynics in distress as “gallows humor.” Here is a bit of it from the monthly prison paper of the inmates of the Charlestown (Mass.) state prison. It is a drama synopsis.

Antiquated Methods at Fall River.—The citizens of Fall River, Mass., have recently been aroused by a revelation of conditions prevailing in the central station house of that city. Because of the lack of modern detention quarters, children, women and men of all degrees of vice are crowded together in a common compartment. A clergyman, who investigated the place, says:

“I found two children there, a boy and a girl, about twelve years of age. At night the station filled up with its inevitable horde of drunkards and offending women, whose language, if not immediate presence, was forced upon these children. I called upon the boy on Sunday and found him the companion of the loose women whose cases were to be heard in court Monday morning. I have nothing to say in regard to the accommodation of the men and women who must needs be shut up. But I think the treatment accorded to these children was outrageous.

“Why were they there? For the inexcusable, the damnable reason, that there was nothing else to be done with them. I am not criticising the officers of the central station. They are extremely kind to these children. It is the city of Fall River that is responsible. The community is committing an offence against children. If the city, as by all means it should, will take in hand either to punish or reform little children, it ought to make provision to properly accommodate such.”

Convict Labor in Colorado.—The rapidly spreading custom of employing convict labor on the roads is strongly indorsed by the experience of Governor Shafroth of Colorado. Under the Colorado system, Governor Shafroth says:

“The prisoners, in large gangs and with but two overseers in charge, work on the state roads, and at times are two hundred miles distant from the penitentiary. There is no confinement, guards or other precaution, yet during the past year there was a net loss of only two men by escape. In one instance a piece of road was constructed through solid rock for $6,000, that would have cost $30,000 under the contract system.”

That the convicts are reconciled to the conditions, the Governor explains is due to a law providing that the time of every prisoner is commuted ten days for every thirty he works upon the roads, and the penalty of three years added to the original term of very convict who escapes, in case he is recaptured. The convicts are in better health than they can possibly be when kept in prison, and work harder than men who are paid by the day.

Prison Verse.—“Verses of Hope” is the title given to a book of poems, written by prisoners at the Kansas state prison, and published under the direction of the chaplain.

Night Court Proposed for Baltimore.—A night court, modeled after the Night Court of New York city, should be incorporated in the proposed reform of the police magistracy system of Baltimore, according to Justice Alva H. Tyson. He believes that the numerous instances of innocent people having to spend a night in a cell in a police station is a relic of a crude governmental system, beyond which Baltimore should have passed years ago.

Another great field in Baltimore for charitable endeavor has been exploited in New York—that is probationary systems for women. Under the present magistracy system of Baltimore, almost all women who are arrested on minor charges, unless hardened criminals, have to be dismissed. What is a magistrate today to do with a woman on her first offense of having too much to drink in the opinion of a police officer? There should be a probationary official to whom she could be released and who could look after her future conduct.

Farm Work for “Convalescent” Offenders.—A new plan, intended to give Kansas convicts a new idea of life, has been put into effect at the Kansas penitentiary, according to the report of Warden J. K. Codding to Governor Stubbs. Every man that is sent to the prison is given six months’ work on the farm just previous to his release. The men get out in the open. They are tanned and sunburned, have more liberty, less discipline, get close to nature and leave the prison with the hatred of men and laws gone and really wanting to try to live better lives. Since the new system has been tried not one released convict has come back. Warden Codding believes that through this system Kansas may gain a record for a minimum number of second-term men which will be lower than that of any other state.

Many years ago an island in the Missouri river was sold to the state. The island has never been used, and the lands owned by the state around the prison have never been used to any great extent for farming. Warden Codding began work two years ago, and the first thing he did was to give the prisoners half an hour’s liberty each day in the prison yard. The men can do anything they wish during that half hour. They can talk to each other and the guard, play ball, pitch horse shoes, play croquet or a dozen other games.

The prisoners had been morose and sullen, and there were twenty-two insane prisoners in the hospital and a half dozen tuberculosis patients. The plan was adopted to see if the insanity and tuberculosis could not be stopped. Not a new patient has developed in 14 months, and there is not a single prisoner in the tuberculosis hospital at this time.

“The farm does two things of great importance,” says Warden Codding. “The first is that it gives the men a new aspect of life as they are about to leave the prison. The farm work and a half hour recreation period have reduced the ordinary prison vices seventy per cent. The plan of working the men on the farm has not been going long enough to make any figures, but I believe that there will be a less percentage of men returned to prison for second terms now than under the old plan of keeping them confined all the time.”

[Pg 16]

The State of Jails in Massachusetts.—The state board of health of Massachusetts finds 45 jails in the commonwealth unfit for occupancy. They are unsanitary and not properly managed. Describing his incarceration in the Middlesex county house of correction in Somerville, Mass., Rev. E. E. Bayliss said in the Boston American of September 24th, that

“When prisoners are admitted they are given no medical examination whatever. The weak, the strong, the sick and the well are all one in the eyes of the prison officials. All receive the same food and the same treatment.

“The result is that there are any number of prisoners suffering from very serious and shocking diseases, who receive either no treatment or treatment of the most perfunctionory sort. In addition all these men use the same knives and forks, the same drinking cups, and the same towels as the rest of the men. They are shaved every day with the same razor.

“In other words no precautions whatever are taken to guard healthy individuals from contamination from diseases, the virulence and contagiousness of which are only too well known.

“The sanitary conditions of the jail are abominable. They are not fit to describe in print, and they nauseate me when I think of them. The bedding, walls and floors swarm with vermin, and the half-hearted attempt to get rid of them by an occasional sprinkling of ill-smelling powder only emphasizes their presence.

“Humanity, common courtesy, the slightest sympathetic realization that we are all human beings, after all, is unknown. There is no one to say a good word to the prisoners. During the three months I was there we had only two sermons, and these were perfunctory in the extreme, and delivered without the slightest idea of appropriateness and of crying spiritual needs of the listeners.”

Alien Criminals.—A study recently made by Joseph P. Byers, general secretary of the state charities and prison reform association of New Jersey shows that 35 per cent. of the prisoners in that state are foreign born. Of the inmates of the state reformatory, 23 per cent. are foreign-born and 45 per cent. are either foreign-born or of foreign parentage.

Alien prisoners in 1909-10 comprised one-fourth of all the inmates of the state prison of New York.

Prison Philosophy.—From the Charlestown (Mass.) state prison paper, the Mentor, come the following verses, written by a prisoner.

CHANCE

What Miss Jane Addams Says.—“More and more our reformatories are filled, not with criminals, but with the boys who have in them the basis of play unsatisfied, the basis of art unfulfilled, even those beginnings of variation from types which we call genius.

“It is these children, our brightest and best, whom we are spoiling by giving them no proper chance for development. The city offers adventurous children nothing to satisfy their desire for pleasure, nothing which will allow them to cherish their determination to conquer the world and make it a better one.

“So these children go out and get into trouble, or else they stay in their poor houses and factories and turn into stupid dullards, all initiative, all ambition stamped out of them.”

A commission, one of whose members is Governor Harmon, is seeking a site for a new reformatory in Ohio.

The commission wants 300 acres of land, and an appropriation of $200,000 was made for purchasing the site and beginning the preliminary work. The commission proposes to locate the prison within a radius of 50 or 60 miles of Columbus.