THE

PILLARS OF HERCULES;

OR,

A NARRATIVE OF TRAVELS

IN

SPAIN AND MOROCCO

IN 1848.

VOL. II.

THE

PILLARS OF HERCULES;

OR,

A NARRATIVE OF TRAVELS

IN

SPAIN AND MOROCCO

IN 1848.

BY

DAVID URQUHART, ESQ., M.P.,

AUTHOR OF

“TURKEY AND ITS RESOURCES,” “THE SPIRIT OF THE EAST,” ETC.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. II.

LONDON:

RICHARD BENTLEY,

Publisher in Ordinary to Her Majesty.

1850.

LONDON:

Printed by S. & J. Bentley and Henry Fley,

Bangor House, Shoe Lane.

CONTENTS

OF

THE SECOND VOLUME.

| BOOK III.

|

| (CONTINUED.) |

| CHAPTER VI. |

| PAGE |

| ARAB DOMESTIC INDUSTRY |

1 |

| CHAPTER VII. |

| RUINS OF BATHS |

18 |

| CHAPTER VIII. |

| THE BATH |

33 |

| CHAPTER IX. |

| THE HELOT |

89 |

| CHAPTER X. |

| THE ARABS OF THE DESERT |

102 |

| CHAPTER XI. |

| RETURN TO RABAT FROM SHAVOYA |

117 |

| CHAPTER XII. |

| THE HISTORY OF MUFFINS.—THE ORIGIN OF BUTTER.—THE

ENGLISH BREAKFAST |

140 |

|

| BOOK IV. |

| EL GARB. |

| CHAPTER I. |

| DEPARTURE FROM RABAT |

188 |

| CHAPTER II. |

| SHEMISH, THE GARDENS OF THE HESPERIDES |

213 |

| CHAPTER III. |

| ARZELA |

245 |

| CHAPTER IV. |

| THE JEWS IN BARBARY |

266 |

| CHAPTER V. |

| TANGIER |

274 |

| CHAPTER VI. |

| DRUIDICAL CIRCLES NEAR TANGIER—CONNEXION OF THE CELTS

WITH THE ANCIENT POPULATION OF MAURITANIA AND SPAIN |

289 |

| CHAPTER VII. |

| THE CLANS IN BARBARY |

312 |

|

| BOOK V. |

| SEVILLE. |

| CHAPTER I. |

| THE ISLAND OF ANDELUZ |

332 |

| CHAPTER II. |

| THE CATHEDRAL |

350 |

| CHAPTER III. |

| SPANISH PAINTING |

361 |

| CHAPTER IV. |

| PELEA DE NAVAJA,—THE OLD SPANISH SWORD |

383 |

| CHAPTER V. |

| THE DANCE |

394 |

| CHAPTER VI. |

| THE ARCHITECTURE OF CANAAN AND MOROCCO |

406 |

| CHAPTER VII. |

| GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE FROM SPAIN |

433 |

THE

PILLARS OF HERCULES.

BOOK III.

(CONTINUED.)

CHAPTER VI.

ARAB DOMESTIC INDUSTRY.

The sheik deploring the result of the day’s hunt, I

expressed the hope that we should make up for it next

day; on this they were thrown into paroxysms, and

they set about the sheik, some by fair means, the rest

by foul, to prevent my doing anything save going

along the main road, or going any road except that

to Dar el Baida, whither I had no particular wish to

go. Despite these difficulties, I found means to concert

privately a chase for the next day. We were to be

limited to twenty guns, and, with a good supply of

beaters, to start early. In the morning, Sheik Tibi

and the other soldiers, after using every effort to stop

me, insisted on going also; thus, the sun was high

before we got a start. We drew two valleys with no

better success than the day before, expending two

hours on each. Being satisfied that there was a purpose

in this, I persisted in trying further off, and

being joined by thirty or forty men from the next

tribe, the oath was administered and we proceeded.

It was now a sight to see the boars, as they issued from

each of two valleys simultaneously beaten, running

about, listening and watching, starting and returning,

as the roll of musketry came up from both sides:

it was like shooting hares in a well-stocked preserve,

without dogs. The scenery surpassed that of the day

before. I was now quite at home with these people,

and it was only after it was over, that we thought it

might have been imprudent to start on such an expedition,

without knowing a word of their language,

and not only without, but in defiance of, the persons

charged with the care of us.

The boars enjoy a state of unparalleled happiness

under the fostering shadow of Islamism and the law

of Moses; a law not so observed in ancient Judæa as

in Modern Morocco, as may be seen by the denunciations

of the Prophets—the occupation of the Prodigal

Son and the selection made by the cast-out devils.

These two laws have excluded from this region domestic

pigs and peopled it with wild ones.

The Arabs hold them to be transformed men and

infidels; and converse with them, interpreting into

words their grunts and motions. Each Arab, as he

came up, soliloquised or addressed a curse to the carcasses,

as he would to a slaughtered doe. These

notions are natural enough, for they seem possessed

of man’s reason with brute’s force. We had commonly

an alarm at day-break of boars close to the douar, and

though instantly pursued by dogs and horsemen, they

managed to escape by speed, dodging, and short turns.

They move through the bushes with a surprising facility

of avoiding noise, squeezing by strength and

with their thick hides through places that appeared

utterly impassable. They get over everything, through

everything, and lie as close under cover as they are

alert when up. In starting for a chase, the boys commence

by plaiting the rush-like palm leaves into a

sling, for it is only by stones that they can start them.

No pigs are fed like these. They have the run of the

forests of cork, producing the bellota and the palmetto-root:

they prefer, however, the potato-like root

of the aram, which is called yerni, and grows generally

in the bunches of the palmetto. In substance it

is like a milky turnip, of a sweetish and mawkish

flavour. Next to this they feed on the narcissus, the

plant of which is called bugareg, and the root bililouse.

They like very much the loto, of which I have yet to

speak, and therefore deserve the name of lotofagoi.

It is called folilla. Their well-known predilection for

turfel—truffles—would be gratified in the extreme, were

it not that the taste of the Arab coincides with theirs.

Every square yard contains these plants, and when

the vegetation is dried up, these roots remain in the

ground fresh and succulent. No wonder, then, that

they prosper, with free quarters and full commons.

The tribes of the Tahel are wood-destroyers. They

consume constantly, and never plant. A portion of

their fuel is brushwood; but still the olive, the oak, and

the arar, the remnants of primeval forests, daily disappear.

Around Rabat, not a tree is to be seen; yet

the firewood is the roots which are dug out of the plain.

The copses, woods, and forests of the cork-tree,

which I have traversed, will have disappeared in a very

few years. This, however, is the effect of stripping

them of their bark for exportation. It was saddening

to pass through these groves, where the ancient patriarch

of the forest was circled by the scalping-knife,

which did not spare even the young promise by his

side; and, as if in savage ruthlessness, and not blinded

avarice, they sought to ensure the decay of the tree.

They had stripped the bark only to the height of a

man, neglecting the rest. They seek the bark only for

tanning. The cork stripped off was lying rotting

around. The cork may be taken from the tree, without

injury, as it covers the real bark through which

the sap runs. This the Spaniards never touch.

Four years ago, this speculation was introduced by

a French merchant. He offered 4,000 dollars for the

liberty of exportation, besides four per cent. duty.

The farm has risen this year to 25,000 dollars. The

Arabs seemed shocked at this work, but avoided the

subject with apparent uneasiness, whenever it was introduced.

I asked them why they did not plant trees

for their children, as they were constantly destroying

those that their fathers had left? The answer was,

“It is not the custom; if we planted them there

would be nobody to watch them, and they would be

destroyed.”

At present, large districts are destitute of douars

from the deficiency of fuel. A considerable portion

of the country I have passed over will soon be in the

same condition, unless by the reduction of the population

the forests are again allowed to spread. The extent

of the change within a century is marked by the

extinction of wild beasts. Travellers, a century ago,

narrate that they did not dare to pass the night out of

a douar for the lions and panthers. Reading these accounts

enables one to understand how the people of

Palestine were not to be driven out before the Jews

in one month or in one year, lest the beasts of the

field should multiply against them. In the times of

the Romans, the lions and panthers must have been

as numerous as are now the

boars.[1]

The chief lady of the douar was too busy for ceremony;—she

left that department to her husband. She

was first lieutenant. But one evening, as we were

returning to the douar, she signified that she had

something to say, and conducting me into the tent,

made me sit down, and, seating herself opposite, said,

“Christian,—since the wives and daughters of your

country’s sheiks neither cook nor weave, nor make

butter, nor look after the guests or sheep, what do

they do?” Having already avowed that the greatest

sheik in the English country had not in his tent or

in his house a spindle or a loom, I explained how

our ladies occupied themselves. She shook her head,

and said, “It is not good;” but added, after a pause,

“Are your women happier than we?” I answered,

“Neither of you would take the life of the other. But

when I tell my countrywomen about you, they will be

glad to hear, and they will not say, 'it is not good.’”

“Christian,” she said, “what will you tell of me?”

I answered, “I will say I have seen the wife of an

Arab Sheik, and the mistress of an Arab tent, such

as we read of in the writings of

old,[2]

such as are the

models held up to our young maidens; such as we

listen to only in songs or see in dreams.”

Had a voice spoken from the earth, I could not

have been more startled. It was Nature saying to Art,

“What is thy worth?” What do we know of the

happiness and the uses that belong to the drudgeries

of life? Our harvest is of the briers and thorns of

a spirit uneasy and over-wrought. Here are no

changes in progress—no revolutions that threaten—no

theories at war—no classes that hate—and why?

The household works. There is no subdivision of

labour—the household, not the man, is the mint of

the state. It is so by its work, its varying cares,

and interchanging toil. These impose discipline, nurture

affection, knit and fortify that unit. Take away

these cares, this industry, this dexterity, this power of

standing alone, and what will—what can—a “home”

become, save a crib to sleep in, with a trough to feed

at, supplied from the butcher’s cart and the huckster’s

stall? Take from the household its industrial character,

and you take away its social charm, and its public

worth. You exchange domestic industry for political

economy—that is, the fictitious evils which it classifies:

for habits you substitute laws, that is, cumbrous

mockery: for happiness, refinement, that is, pretence:—and

you become possessed of the gifts of fortune—the

few at least who draw the prizes, only to lose the

value, of life.

The change in our manners is producing, no doubt,

an alteration in the position as well as in the happiness

of women. From my first acquaintance with the

East, I was struck with the erroneous notions which we

entertain regarding the state of the sex there. I could

not resist the evidence of their occupying relatively

a higher station, and I perceived that the difference

depended upon the greater strength of the family tie.

I find in an official French work[3]

my proposition

strengthened.

“In all the Sahara, the fabrication of stuffs is

exclusively the work of the women. The men apply

themselves to the culture of the date-trees. It has

been already shown that in the movements and expeditions,

the women have their share equally allotted

to them with the men. Thus, in the produce of the

labour of the Sahara, that of the women amounts to

one-half. In the intervals of their necessary household

occupations, they find time to contribute to the

common riches an equal quantity with the men.

This is a fact which it appears to us worthy of being

placed in evidence, because it is impossible that it

should remain without influence on the condition of

the female sex. The inutility of the occupations in

which they are engaged almost everywhere else, explains

perhaps, to a certain degree, and excuses the

state of dependence in which they are placed, and

the disregard of which they are the object; but where

by the nature of the occupations they are placed upon

a level equal with that of man, he must cease to

regard himself as the sole chief of the domestic hearth,

and be prepared to share the family sovereignty with

his companion. It is certain that in the Sahara the

merit of a woman is measured above all by her talents

and dexterity.”

In Egypt all things were consecrated, and then

displayed in types. The successive labours (as even

to these days in Africa) were announced from the

sanctuary, accompanied by sacrifices and processions,

and amidst the richness of their ceremonials,

and the pomp of their temples. The changes of the

seasons which they announced, appeared to flow from

their directing power, and the labours undertaken to be

the fruit of their providential care. Before calendars

were printed, all field labours had to be determined

by astronomy, and especially in the valley of the Nile,

which was subject to disappear under a deluge, and

whose fertility consisted in the rise and duration of the

flood. Placing ourselves in the soft and yielding, the

unlearned and unprejudiced embryo of society; man

groping his way, fearful to stray, yet eager to advance,

what more natural than a scientific priesthood and a

symbolical worship? The Greeks, copying these fruitful

symbols, sacrificed purpose and usefulness to grace.

The name of Moses, we are informed in Scripture,

means saved from the water. The Muses was the

same word: nine months in Egypt are saved from the

waters—these are the Muses. Each had its festival,

and the symbol of its occupation. There were three

other similar—these are the Graces—they are admitted

by the most learned Hellenists to be water-nymphs;—together

they make up the year. Here, then, we

have the homeliest occupations the basis of the religious

pomps of Egypt, and of the mythology and

art of Greece; the distribution of these works filled

up the year, combined field and in-door labour, and

linked the community, while furnishing the charm of

life.

The plough, the yoke, “The invention of gods and

the occupation of heroes;” are the loom, the spindle,

and distaff of less noble parentage? You sever the

distaff and the plough, the spindle and the yoke, and

you get factories and poor-houses, credit and panics—two

hostile notions, agricultural and commercial.

Poetry becomes politics, patriotism faction; and a

light-hearted and contented people rusts into clowns

or sharpens into knaves.

I made, amongst the Arabs, the discovery that home

industry was the secret of the permanency of their

society. I made, on subsequently visiting the Highlands,

another, namely, that home-made stuffs are the

cheapest. I refer, of course, to the common clothing

of the labouring population. The comparison cannot

be instituted where the habit has been extinguished;

for on the one hand, the implements and the dexterity

are wanting; on the other, fashion has set another way,

and new habits have arisen, adjusted to the articles and

stuffs that have been introduced. In the Highlands,

however, the comparison is easy, and I speak after

thorough examination, and with perfect certainty,

when I say that a family clothed by its own homework,

as compared with a family which buys its

clothes at the shop, saves one-third. Of course, in the

former case, no cotton will be used, and home-bred

wool and home-grown flax will be the staple.

The change in this respect is generally deplored;

but it is considered as inevitable, it being the result of

cheapness, no hand-labour being able to stand against

machinery. But the heavy charges are not for the

operation but for the capital engaged, and the numerous

transfers and profits. Home-spinning costs

nothing.[4]

Twenty pounds of wool converted unobtrusively

into the yearly clothing of a labourer’s family,

makes no show; but bring it to market, send it to the

factory, bring it thence to broker, send it to dealer, and

it will represent commercial operations and apparent

capital to the amount of twenty times its value, and

costs the labourer, when returned to him, twice as

much as it would cost him money in dyeing, spinning,

weaving, &c. The working class is thus amerced to

support a wretched factory population, a parasitical,

shopkeeping class, and a fictitious, commercial, monetary,

and financial system. The landlord, for his

share, pays five shillings per acre poors-rates. And all

this is the result, not of cheapness, but delusion. The

people of England were better clothed and fed than at

present, when there were no commerce and no factories.

At this moment, after exhausting human ingenuity,

they are returning to domestic labour, as a

means of remedying the evils of Ireland!

Hallam has admitted that in those times which we

look back on with pity, the labourer received twice as

much as at present for his labour. This is a terrible

blow and a fearful avowal. Mr. Macaulay, on the

contrary, “sees nothing but progress, hears of nothing

but decay.” He must have transposed the two senses,

or carefully selected the spots for indulging in their

use: if, indeed, by progress he means approach towards

a fair remuneration for labour, and by decay a falling

away from just judgment in important concerns. Or

is it his purpose to cover Hallam’s indiscretion?—“They

say that in former times the people were better

off. The time will come that they will say the same

of this.” If we be in a state of progress, those who

speak thus must be very foolish, and if the proposition

deserved notice it required refutation.

The Arab tent, without our waking follies, presents

to us the reality of our dreams. Property has there

its value, wealth its honour, labour its reward. On

the one side, the fruits of wisdom without effort, on

the other the toil of the understanding without profit.

But the Arab woman asked, “Are your women happier

than we?” The European lady would be shocked

at the bare possibility of comparison. She shrinks

from domestic occupation, yet is she not able to

expel nature, so as to despise Nausicaa and Naomi. We

cannot refuse to bow before the shades of the heroic

or patriarchal times—our nature acknowledges Abraham

or Alcinous. Yet, if our condition be that of

refinement, how contemptible must be Tanaquil and

her distaff, Penelope and her loom?

An English lady, who had the means of comparison,

has not hesitated to assert that between an Eastern and

an European household, the balance of happiness leans

to the side of the former; and in the Eastern household

it is certainly the women who have the larger share—who

are the idols, and who possess authority such as

belongs not to our courts, and affections on the part

of those under their sway which belong not even to

our dreams. The most touching words of the wisest

of men are the description of the mistress of a household.

It is an Arab woman he describes.

“Look at the hand of man! The best gift of Providence!

What so perfect in mechanism, what so

beautiful in form? Is it not given for work, and

ought not that work to be for the service of those we

love? Can we omit that use without the sacrifice of

more than words can tell? Let not any one who follows

the picture disturb the effort of his own imagination,

to fill it up by thinking of the possibility of

carrying it into effect. Obstacles arise at every point.

Our set habits all point the other way. Julia could

work for her husband because there was then a noble

and an antique costume. An empress, she could summon

about her her handmaidens, because there was a

formula of ceremony which enabled all ranks to associate

without derogation or familiarity. Then there was

the hall to assemble in. 'The plant,’ still stood in every

house. Because all this is gone, are we not to count

the loss? If we cannot restore, let us not mistake.

If we cannot return, let us not hurry on—in the wrong

direction. It is something to know whither we are

going, when the speed is the result of our own will.

“Nations are not changed by time or accident—they

change themselves. Progress of society—march of intellect!

Good heavens! we can utter such trash and call

ourselves reasonable beings: as well speak of the justice

of a steam-engine, or the virtue of a rocket. What need

to examine their state;—their words suffice. When

the phrases have gone mad, what can be in order?

“It is something in the midst of empires crumbling

to the earth and civilization gasping for breath and

struggling with itself for life, to point to the permanency

of single tribes, who have never reasoned, but

who have simple habits; and to be able to say to the

wildly-frantic or to the meekly-deluded, ‘Christians,

ye are incorrigible.’”

Such were the concluding words of a series of

articles by M. Blacque, which appeared in the Moniteur

Ottoman, in 1834. Since then fifteen years—barren,

save in convulsions such as many centuries

have not witnessed before—have justified his judgment

on Europe’s condition, and his anticipations of her fate.

M. Odillon Barrot, his cousin, on one occasion said

that had he returned, he “would have played a great

part in France.” I answered, “He would have made

France play a worthy one.” He was offered the

highest offices in the Russian Government, and on

refusing them was persecuted by his own. The

Turkish Government then adopted him, and he was

poisoned while on his way to England. The incidents

of his life and death, no less than the passages left

by his pen, will serve at a future time, perhaps, to

illustrate that chimera with a brain of cobwebs and a

heart of mud, which is called civilization, and which

we are pleased to designate as the child of science and

the parent of corruption.

But I do not speak of “civilization,” as an entity.

It will be found in no classical writer, Greek or Roman,

English or French, German or Italian. It is a word

which belongs to us,—exclusively to us; let us be

either proud or conscious—its invention must be

either a merit or a shame.

What is it? It is no standard. We have the

words “excellence,” and “perfection.” It is no description

of a particular people, for it neither does

nor can describe or define. Its own sense has to be

defined. Whoever uses the word, conjures up to correspond

with it an idea of some aggregate condition,

which never can have the same parts in any two

speakers’ minds, or in the mind of the same speaker at

any two moments. It is an unknown quantity, like

x in algebra; but instead of concluding the operation

by finding out its value, we commence the proposition

by supposing it known. These are the reasons why

you do not find it in any classical writer. These are

the reasons why it has been received as a discovery

for this generation. It facilitates talk without meaning,

is a cloak for ignorance and pretence, and covers,

by an apparent “grasp of intellect,” the shrinking

from intellectual effort, which consists in getting possession

of the instruments we use, and in fathoming

the meaning and assuring ourselves of the accuracy

of the terms we employ. It is made up of things

that have no ratio—virtue and science, wealth and

political order; so also, vice, ignorance, poverty, and

discontent—each of these must be found in it: to

employ it logically, you must class plus and minus

quantities and rate each in decimals. So in one

country there would be so many degrees of positive,

in another so many of negative civilization. If you

cannot do this, you use an instrument that is necessarily

false; the whole field of your intellectual operation

must be, as it is, reduced to that condition in

which our buildings, railways, and accounts would be,

if arithmeticians and engineers were to create an

elementary sign of number, the value of which was

uncertain, and might be mistaken for an 8 or a 9. It

is the case, not of an error of opinion, but of false process,

which renders it impossible to be right. It is not

opinions, but words, that ruin states. Should a sane

people occupy Europe after the Gothic race has been

put down or swept away, the title of M. Guizot’s great

work will suffice for the history of times distinguished

at once by a fatuity that cannot reason,[5]

and an

activity that will not rest. Alas for man, if such

things as we have seen since the conversation in the

Arab tent, which prompted these reflections, were the

fruit of the proper use of his faculties! Alas for folly

too, if, with such men for its apostles, institutions

could endure or nations prosper!

CHAPTER VII.

RUINS OF BATHS.

After a few days spent as those I have described,

we started in a south-westerly direction, and towards

evening passed out of the land of the Ziaïdas. Their

territory extends a summer day’s journey from north

to south, and from east to west. We then entered

that of the Ladzian. Our guardians inquired from

the shepherds touching different douars, to select one

for sleeping, but did not seem satisfied with the replies.

I urged going to one of the Lachedumbra, a tribe of

the Ladzian, and they reluctantly complied. This was

the first douar we approached as perfect strangers.

We rode up to within two hundred paces and halted.

After we had waited about ten minutes we advanced

half way and halted again. Then one man walked

slowly out; one of our party in like manner advanced.

They saluted. After some time the Arab shouted,

and instantly a single man advanced from each of the

tents on the side next us: they stood for some minutes

as if holding council. The chief then turned round,

and walking straight up to me, took my hand in their

manner, and thrice repeated Mirababick; the others

then advanced, and pronounced the salutation all

together. Each of the party was thus greeted in turn.

We were led inside. The whole douar set to work,

and in a few minutes our tent was pitched, and strewed

with fresh shrubs. A sheep was led up to the door,

the customary present of the sheik, that we might

see it before we made our supper on it. This was

a Sherriff’s douar, and the government officers have

no right to enter. Such was the explanation given

to me. It is difficult to ascertain, and impossible to

vouch for, the commonest fact in a country where one

is not thoroughly conversant with its habits, and when

information is received through interpreters, however

intelligent and upright these may be; and, indeed,

integrity is next to an impossibility in an interpreter;

but this an eastern traveller learns, if at all, at the

wrong end of his experience.

I have seen no douar entered except by the free

will, and in some cases the formal consent, of the

tribe. I was much perplexed at this, as it appeared

at first a contradiction to, and as I afterwards ascertained,

modification of the fundamental rule of Arab

society. It doubtless arose from the necessity of

defence against a central government.

After they had pitched our tent, instead of pressing

upon us as amongst the Ziaïda, they drew off about

thirty yards, and squatted down in a circle: a few

only came, and then it was to bring presents, or to

petition for medicine for a greasy heel, or a barren

wife, as the case might be. I proposed to the sheik a

boar hunt, to which he readily assented; but it was

fixed for a future day.

From the high ground, as we approached it, Dar El

Baida has an imposing appearance: inside it is a heap

of ruins. A house consisting of a single room—a good

one on a second floor, and entered from a terrace—was

prepared for us. Our horses were piqueted in the

street before it. We understood there was a French

Consular agent and some Europeans here, and consequently

we brought for them a camel-load of game.

This place is said to have been retaken from the

Portuguese by the following stratagem. A Moor pretended

to become Christian, settled in the town, and

obtained permission to have a gate opened in the wall

close to his house for the convenience of sending in

and out his flocks. He one night brought in a number

of his countrymen covered with hides, as cattle among

them. Such is the story of the place; and if you

doubt it, they say, “There is the gate.”

The Spanish name is Casa Bianca, just as if we

chose to call it “White House.” Its ancient name,

“Anafe,” involves some obscurity. The same name

belonged to a colony in Asia Minor, and to an island

close to Crete, which forms an episode in the Orphic

epic of the Argonauts. The adventurers were rescued

by Apollo, who discharging an arrow into the deep,

the island arose, and was called Anafe, from ἀνφααίνειν,

to appear. What this etymology is worth for the

Cretan Island, it must also be for the Lybian promontory:

its present name likewise implies brightness. It

is on the other hand asserted, that this is the new

case of lucus a non lucendo, and that Anafe means,—that

is, in Hebrew not Greek,—dark and gloomy,[6] and

that the island was so called, not from having appeared

in the light, but by being shut out from the light by

groves.[7]

If so, the Lybian promontory must likewise

in those days have been green and feathered, and not

as now, naked and pale. The Phœnician Backs and

Parrys did not dot their charts with the names of

the Admiralty Lords of Tyre. They gave names descriptive

or commemorative, as the other names of this

coast will vouch. That the name is Phœnician, not

Greek, is clear from finding it here. We have also

Thymiatirium, where Arzilla now stands, and which

is interpreted in Hebrew—an open plain. Ampelusa

was on the northern promontory, and its interpretation

coincides with the descriptions left of groves

delightful to the eye, filled with fruit grateful to the

taste. This must have been one of the spots first

named, and this name seems to confirm what we derive

from so many sources regarding the primeval horticulture

of this land. Had the Phœnicians come to

plant vines, and gardens—that is, to cultivate and civilize—they

would not have given such a name. These

glimpses of the well-being in the most early times bring

up the contrast with the present. The parched and

naked brow of the once shady Anafe, further recalls

an island nearer home, once, also, named after its

forests,[8]

where now scarce a tree is to be found.

Would that the resemblance were complete! If Moorish

rule has blasted the oak, it has at least spared the

man. What Moorish rule has worst done it has done

with a purpose, and neither on principle nor for philanthropy.

A quantity of grain was in store, and much arriving

destined for England. The stores were filled all

along the coast, but there are no means of shipment.

This port is a principal place for the exportation of

bark and wool, both managed by Scheik Tibi, who,

last season, when the country was otherwise impassable,

went and came, conducting caravans of seventy

and eighty camels; by his personal character ensuring

safety on the road. The schooner which had been

in company with us during our voyage, lay on the

beach high and dry. An English brig at anchor in

the open roadstead was pitching bows under, though

there was scarcely a breath of wind, and had narrowly

escaped shipwreck two days before from her

cables having been cut by the rocks.

There is here a sort of bay. The southern horn is a

headland running a little way out, and distant four or

five miles. On its bald black brow I was told that

traces of the Phœnician city were to be seen. I was all

impatience to reach the spot, for it was just a site for

them, and no one since would have gone there. So

here was the site of a Lybo-Phœnician city, and any

fragment was precious. I found nothing standing, yet

was not disappointed; for the stones in the fields were

rolled fragments of building: the mortar was of such

consistency that it wore or split only with the stones

imbedded in it, and these were crystalline: the stones

were small, the mortar abundant; the masses looked

like amygdaloid. For the first time was I assured that

I beheld a piece of Tyrian rubble. I would have travelled

many a mile for this. Mortar was used by

them—and what mortar! But this was not the only

architectural point I had to mark this day.

As I sat on the brow of the headland, watching the

great waves which went and came over long shelves of

rocks, stretching out to the west and southward in the

line of the declining sun, and playing under his rays,

my eye was attracted to a singular mass immediately

below: it was a cone indented all over with deep

semicircular cavities, and, therefore, bristling with

truncated points. The sandstone hollows out in this

manner[9]

by the action of the water, and the points

which are left are sharp as a knife. The substance is

black and porous, like a sponge. When the foam

dashed over this rock, the basins filled; the white froth,

as the wave retired, poured in cataracts from basin to

basin, on every side, and so continued almost till the

next long wave came to shroud it in spray, and replenish

it with foam. As I watched these changes,

familiar forms floated before me, till at last becoming

more distinct, I distinguished those singular pendants

that belong to the Moorish vault, and the indentures

of its arch. The stalactites of caverns might

have furnished the type of the last, but could not of

the former. The fair creations of art have models in

Nature, and here is that of the Moorish. The substance

in which it is exhibited lines the whole coast,

and must present an infinite variety of such effects.

I had few occasions of seeing that coast, but the very

next time I reached it, about twenty miles north of

Rabat, I saw the same figure reversed, or as we see it

in the Moresco vault, depending from the roof like the

stalactites in a cave.[10]

I returned to the same place next morning, but the

tide was out, and the rock without the foam was a

common stone. The ledges of rock which the evening

before had been so lashed by the waves, were white

(quartz) rock. On them were patches of coarse recent

madrepores, looking like gigantic sponges. Further

out the rocks were black, and on inspection proved to

be so because completely covered with mussels, the

largest I have ever seen, and the finest I have ever

tasted. Such is the fury of the waves, that beautifully-rounded

quartz-stones, some of them three-quarters of

a hundred weight, have been cast up into a bank thirty

feet above high-water-mark.

Amongst the mass of ruins within the walls of Dar

el Baida one building alone could be made out. It

was a bath. If London or Paris were laid low, no

such monument would survive of their taste, luxury, or

cleanliness. The people called it “Roman,” meaning

Portuguese. When I was at Algesiras, some excavations

were making, and on examining them, the building

proved to be a bath. Within the circuit of the walls

of old Ceuta, which unquestionably belonged to a very

remote period, the only edifice, the purpose of which is

distinguishable, is a bath. The vestiges of the Romans,

which from time to time we fall upon in our island,

are baths. The Romans and the Saracens were the

most remarkable of conquerors, and are associated in

the relics which they have left-fortresses and baths.

The first is of necessity, but how should the second

be ever found conjoined, unless it played some part

in forming that temper which made them great, or in

conferring on them those manners which rendered

them acceptable? A nation without the bath is deprived

of a large portion of the health and inoffensive

enjoyment within man’s reach: it therefore increases

the value of a people to itself, and its power

as a nation over other people. From what I know

of the loss in both respects which those incur who

have it not, I can estimate its worth to those who

had it.

I now had the opportunity of examining a public

bath of the Moors belonging to their good times.

The disposition varies from that of the ancient

Thermæ and the modern Hamams. The grand and

noble portion of the Turkish and the ancient bath was

a dome, open to the heavens in the centre. Such a

one, but not open in the centre, is here; it was the

inner not the outer apartment. The vault has deep

ribs, in the fashion of a clam shell, and is supported

upon columns with horse-shoe arches spreading between.

Instead of a system of flues through the walls,

only one passed through the centre under the floor.

To get at it, I had to break through the pavement of

beaten mortar covering a slab of marble. It was

nearly filled up with a deposit, partly of soot and

partly of earthy matter, which I imagined to be the

residuum of gazule, on the use of which hinge the

peculiarities I have noticed in the structure and distribution

of the building.

I turned to Leo Africanus, expecting a flood of light

upon a matter with which he must have been so

familiar. All I found was this:—“When any one is

to be bathed, they lay him along the ground, anointing

him with certain ointment and with certain

instruments clearing away his filth.” The ointment

is evidently the gazule; the instrument can only be

the strigil. He mentions a “Festival of the Baths.”

The servants and officers go forth with trumpets and

pipes, and all their friends, to gather a wild onion; it

is put in a brazen vessel, covered over with a linen

cloth, which had been steeped in lees of wine; this they

bring with great solemnity and rejoicings, and suspend

in the vessel in the portal of the bath. This would

indicate an Egyptian source, were it not for the absence

of all trace of the bath on their storied walls, and

among their ruins.

The onion, however, being the emblem of the planetary

system,[11]

may be a trace of Sabæism. The

festival and ceremony savour much of those of the

“Great Mother,” and of course preceded Christianity.

No original superstition arose here; no original bath

appears among the Arabs. The Phœnicians brought

their religion and found the bath, and to it the people

adapted the new religious practices.

Part of the funereal rites of the Moors was to

convey the corpse to the bath.[12]

Such a practice is

unknown in any other country, and seems to identify

the bath with the primitive usages.

The gazule furnishes, however, the strongest intrinsic

evidence in favour of my conclusion, which indeed

it requires but scanty proof to establish, for the

rudest people may have had the bath. The Red

Indians are fully acquainted with it, and the means

they employ are heated stones and a leather covering.

They crawl in and throw water on the stones, and soak

till the same effect is produced as the Balnea of Rome

obtained. In Morocco they are of primitive and modest

structure, and of diminutive proportions. Add to

this, the rude simplicity of the process, and the exclusive

use in them of natural and native productions.

Before coming to this point, I wish to refer to historical

evidence.

Augustus borrowed a stool, called

duretum,[13] from

Spain. Mauritania was inhabited by the same people,

so that two thousand years ago the Romans copied the

Moors.

Few Iberian words have come down to us—one

of them is strigil. It applied to a species of metal;

and strigils were made of metal. The early use

of this strigil, and its connection with the East, is

shown by one of the celebrated bronzes of antiquity—a

group of two boys in the bath using the strigil,

which was attributed to

Dædalus.[14] The Etruscans

and Lydians also had

it.[15]

The Phæacians, as elsewhere shown, were Phœnicians.

Homer mentions their baths at the time of the

Trojan war, when the Greeks had none. The term

Ἡρακλεία λούτρα seems to identify baths with that

people as much as letters were by the term Καδμεία γράμματα;

and as the Greeks got everything from

them, the baths of the Greeks are in themselves a

testimony in favour of the Phœnicians, my inference

being, not that the Phœnicians brought thither the

tice, but that they learnt it here.

That the Arabs, when they issued from their deserts,

should have adopted the Thermæ and Balnea of the

sinking Roman empire, does not necessarily follow;

indeed it is rather to be assumed that they would not,

and that it was from a people who became by religion

incorporated with them, and from whom, indubitably,

they derived their architecture, that they had it.

This view is supported by the use of the glove, which

is not Roman, and the disuse of the strigil, which

was so. It would thus appear that Morocco had conferred

on antiquity and the East of the present day,

the chief luxury of the one, and the most beneficial

habit of the other.

There being a bath in the unoccupied house of the

Governor of the Province, I made the attempt to complete

my investigation by experience, and privately

applied to the guardian of the mansion, who, to my

surprise, immediately acceded to my request. Soon

after, he came to inform me that the Caïd had been

very angry, and had forbidden him to let me use it.

It was suggested that there were mollifying methods,

such as a civil message, a box of tea and some loaves

of sugar. While these were preparing, an elderly

Moor walked in and seated himself. This was no

other than the Caïd. He plunged at once in medias

res, and the following dialogue ensued.

Caïd. No Christian or Jew can go to the bath. It

is forbidden by our law.

Can a law forbid what it enjoins?

Caïd. It is the law.

Where is that law?

Caïd. (After a pause.) The wise men say there is

such a law.

The wise man is he who speaks about what he

knows.

Caïd. Do the wise men err?

Have you read the book?

Caïd. I have heard it read.

Did you hear the word—the Jews and Christians

shall not bathe?

Caïd. I may or may not have heard.

I have read the book, and have not seen that word,

for in it there is no name for bath. The Mussulmans,

when they came to “the West,” found the bath in

your towns as they are to-day, and here first learned

how to bathe, and you were then Christians. How

then do you say you have a law which forbids the

Jews or the Christians to go to the bath?

Caïd. (laughing). The Nazarenes are cunning. In

what Mussulman land do Christians go to the bath?

Missir, is it not a Mussulman land? Stamboul

(Constantinople), is it not a Mussulman land? Now,

I will ask you questions. Where, except in this dark

West, do Christians not go to the bath with the Mussulmans?

Why do I want to go to the bath? Have we

got the bath in Europe? From whom did I learn it?

Caïd. How can I tell?

I have gone to the bath with doctors of the law

(Oulema), and Rejals of the Ali Osman Doulet: I have

been shampooed by vizirs. From Mussulmans I have

learned how to wash myself, and here I come to Mussulmans,

and they say, “You shall not bathe.” This

is not Islam, this is

Jahilic.[16]

Caïd. You shall not say our faces are black. You

shall go, but—only once. To-morrow I will keep the

key: it shall be heated when the Mussulmans are

asleep. I will come, and you shall go and be satisfied.

He then got up and walked off. Presently a sheep

arrived as an earnest and propitiation.

It was so often and so confidently repeated to me

by the resident Europeans that I could place no reliance

upon his word, that I gave up all idea of it.

Next night, as we were disposing our beds and preparing

to occupy them, there was a rap at the door,

and on its being opened, who should walk in but the

Caïd. His abrupt salutation was, “The bath is ready—come.”

While I was re-dressing, he told us that

he had forgotten, and having business of importance

with a neighbouring sheik before sunrise, had started

on his journey, when recollecting his promise, he had

returned.

Finding he was making dispositions to accompany

me, I begged he would not take the trouble; but not

staying to answer, he seized with one hand a candle

out of the candlestick, laid hold of my hand with the

other, conducted me down stairs, lighting me and

lifting me through the dirty streets over the different

places, as if I had been a helpless child. Arrived at

the place, he took the keys from his breast, and opened

the doors. I thought his care was to end here, but he

squatted himself down on a mat in an outhouse, as if

to wait the issue. Every other argument failing, I

said, that if he remained there, I could not stay long

enough. He answered, “I will sleep. If I went home

I could not sleep, for something might happen.” The

deputy-governor stripped to officiate as bath-man.

But for this weighty matter I must take breath, and

honour it with a special chapter—a chapter which, if

the reader will peruse it with diligence and apply with

care, may prolong his life, fortify his body, diminish

his ailments, augment his enjoyments, and improve

his temper: then having found something beneficial

to himself, he may be prompted to do something to

secure the like for his fellow-creatures.

τοὶ δ’ ἀγλαὸν Ἀπόλλωνι

Ἄλσει ὲνὶ σκιερῷ τέμενος σκιόεντά τε βωμὸν

CHAPTER VIII.

THE BATH.

... Quadrante lavatum,

Rex ibis. Hor.

Sat. i. 3.

It is amusing to hear people talk of cleanliness

as they would of charity or sobriety. A man can

no more be clean than learned by impulse, and no

more by his will understand cleanliness than solve

equations. Cleanliness has the characters of virtue

and of vice—it is at once beneficial and seductive. It

is also a science and an art, for it has an order which

has to be taught, and it requires dexterity and implements.

It has its prejudices and superstitions: it

abhors what is not like itself, and clings to its practices

under a secret dread of punishment and fear of sin.

It has its mysteries and its instincts: it regards not

the eye or favour of man, and follows the bent of its

nature without troubling itself with reasons for what

it does; it has its charities and its franchises: the

poorest is not without the reach of its aid, nor the

most powerful strong enough to infringe its

rights.[17]

It is suited to every condition: men and women, the

young and the old, the rich and the poor, the hale and

the sick, the sane and the insane: the savage can

enjoy it no less than the refined. The most polished

have prized it as the chief profit of art; the simple

receive it as the luxury of Nature—a cheap solace for

the cares of life, and a harmless medicament for the

infirmities of man.

The philosopher prized it as essential to

happiness,[18]

the austere to virtue, the dissolute to

vice.[19] To corrupt

Greece and Rome it furnished a gratification that

was innocent; to the rigid sectarians of the Koran

an observance that was seductive; multiplying the

sensibilities and strengthening the frame, it increased

to all the value of life. No sacrifice is required for

its possession. Nothing has to be given up in exchange:

it is pure gain to have, sheer loss to want.

Like the light of heaven, those only walk not in it

who are blind. Where not practised, it is not inducements

that are wanting, but knowledge: “they

don’t know

how.”[20]

Our body is a fountain of impurities, to which

man is more subject than the

beast.[21] The body of

man, far more than that of the brutes, is exposed to

be contaminated; and by an artificial mode of life

and food, he has further multiplied his frailties. By

casing his body in closely-fitting clothes—integuments

rather than covering—he has shut out the purifying

elements. Without the means of cleanliness of the

brute, he is also without the guidance of its instinct;

what then, if in the culture of his body, he should

lose the light of reason? If reason and not instinct

be his portion, it is because he is endowed with a

mechanism, to keep which in order instinct would

not suffice. What if that mechanism receive at his

hands not such care as would be bestowed upon it,

if it belonged to the beast of the field or the bird

of the air!

What filth is to the body, error is to the mind;

and therefore if we are to use our reason in regard to

the former, we must have a standard of cleanliness as

well as of truth; such a rule we can owe neither to

freak nor fashion. We must look for one tested by

long experience and fixed from ancient days:—this

standard is THE BATH. This is no ideal one; it is at

once theory and performance; he who has gone

through it, knows what it is to be clean because he

is cleansed. I shall use as synonymous the words,

“cleanliness,” and the “bath.”

I must beg the reader to dismiss from his mind

every idea connected with that word: unless I thought

he would and could do so, I should persist in speaking

of Thermæ,

Balneum or Hamâm, but I trust I may

venture to naturalize, in its true sense, the word in

our tongue as a step to naturalise the thing in our

habits.

A people who know neither Latin nor Greek have

preserved this great monument of antiquity on the

soil of Europe, and present to us who teach our children

only Latin and Greek, this institution in all its

Roman grandeur, and its Grecian taste. The bath,

when first seen by the Turks, was a practice of their

enemies, religious and political; they were themselves

the filthiest of mortals; they had even instituted filth

by laws and consecrated it by

maxim.[22] Yet no

sooner did they see the bath than they adopted it;

made it a rule of their society, a necessary adjunct

to every settlement; and Princes and Sultans endowed

such institutions for the honour of their

name.[23]

In adopting it, they purified it from immorality and

excess, and carrying the art of cleanliness to the

highest perfection, have made themselves thereby the

most sober-minded and contented amongst the nations

of the earth. This arose from no native disposition

towards cleanliness, but from the simplicity of their

character and the poverty of their

tongue.[24] They had

no fallacious term into which to convert it, and no

preconceived ideas by which to explain it. Knowing

they were dirty, they became clean; having common

sense, they did not rush on a new device, or set up

either a “water cure,” or a joint-stock washing company;

but carefully considered and prudently adopted

what the experience of former ages presented to their

hands.

I have said that the Saracens, like the Romans,

have left behind them, temples, fortresses, and baths:

national security reared its battlements, public faith

its domes, and cleanliness, too, required its structures,

and without these no more could it exist, than defence

or worship. I shall not weary the reader with ground-plans

or “elevations,” and shall confine myself to the

leading features, in so far as they are connected with

use. They are vast and of costly materials, from their

very nature. Before describing the Moorish bath, I

must request the reader to accompany me through the

bath as it is used by the Turks, which, as more complete

and detailed, is more intelligible.

The operation consists of various parts: first, the

seasoning of the body; second, the manipulation of

the muscles; third, the peeling of the epidermis;

fourth, the soaping, and the patient is then conducted

to the bed of repose. These are the five acts of the

drama. There are three essential apartments in the

building: a great hall or mustaby, open to the outer

air; a middle chamber, where the heat is moderate;

the inner hall, which is properly the thermæ. The

first scene is acted in the middle chamber; the next

three in the inner chamber, and the last in the outer

hall. The time occupied is from two to four hours,

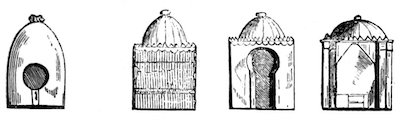

and the operation is repeated once a week.

On raising the curtain which covers the entrance to

the street, you find yourself in a hall circular, octagonal,

or square, covered with a dome open in the

centre: it may be one hundred feet in height; the

Pantheon of Rome may be taken as a model. This

is the apodyterium, conclave or spoliatorium of the

Romans. In the middle, a basin of water, the “sea”

of the Jews, the “piscinum” of the Romans, is raised

by masonry about four feet; a fountain plays in the

centre. Plants, sometimes trellises, are trained over

or around the fountain, and by it is placed the stall

to supply coffee, pipes, or nargelles. All round there

is a platform, varying in breadth from four to twelve

feet, and raised about three; here couches are placed,

which I shall presently describe. You are conducted

to an unoccupied couch to undress; your clothes are

folded and deposited in a napkin and tied up; you

are arrayed in the bathing costume, which consists

of three towels about two yards long and under a

yard in width, thickened in the centre with pendant

loops of the thread, so as to absorb the moisture, soft

and rough without being flabby or hard, with broad

borders in blue or red of raw silk. This gives to this

costume an air of society, and takes from it the stamp

of the laundry or wash-house. One is wrapped with

an easy fold round the head, so as to form a high and

peculiar, but not ungraceful turban; the second is

bound round the loins, and falls to the middle of the

leg; this is the ordinary costume of the attendants

in the bath, and appears to be the costume known

in antiquity as περίζωμα, præcinctorium,

and subligaculum,

and which have been of difficult interpretation,

as implying at once a belt and a clothing. The

third is thrown over the shoulder like a scarf: they

are called Pistumal, as are all towels, but the proper

name is Futa, a word borrowed, as the stuff is, from

Morocco. While you change your linen, two attendants

hold a cloth before you. In these operations, which

appear to dispense of necessity with clothing and

concealment, the same scrupulous attention is observed.

It extends to the smallest children. I have

been on a bathing excursion to the sea-side, where

a child under four years was disappointed of his

dip because his bathing drawers had been forgotten.

There is nothing which more shocks an Eastern than

our want of decorum; and I have known instances

of servants assigning this as a reason for refusing to

remain in Europe, or to come to it.

Thus attired, you step down from the platform

height; wooden pattens,—nalma in Turkish, cob cob

in Arabic,—are placed for your feet, to keep you off

the hot floors, and the dirty water running off by the

entrances and passages; two attendants take you, one

by each arm above the elbow—walking behind and

holding you. The slamming doors are pushed open,

and you enter the region of steam.

Each person is preceded by a mattress and a cushion,

which are removed the moment he has done with them,

that they may not get damp. The apartment he now

enters is low and small; very little light is admitted;

sometimes, indeed, the day is excluded, and the small

flicker of a lamp enables you to perceive indistinctly

its form and occupants. The temperature is moderate,

the moisture slight, the marble floor on both sides is

raised about eighteen inches, the lower and centre part

being the passage between the two halls. This is the

tepidarium. Against the wall your mattress and

cushion are placed, the rest of the chamber being

similarly occupied: the attendants now bring coffee,

and serve pipes. The object sought in this apartment

is a natural and gentle flow of perspiration; to this

are adapted the subdued temperature and moisture;

for this the clothing is required, and the coffee and

pipe; and, in addition, a delicate manipulation is

undergone, which does not amount to shampooing:

the sombre air of the apartment calms the senses, and

shuts out the external

world.[25]

During the subsequent parts of the operation, you

are either too busy or too abstracted for society; the

bath is essentially sociable, and this is the portion

of it so appropriated—this is the time and place where

a stranger makes acquaintance with a town or village.

Whilst so engaged, a boy kneels at your feet and

chafes them, or behind your cushion, at times touching

or tapping you on the neck, arm, or shoulder, in a

manner which causes the perspiration to start.

2nd Act.—You now take your turn for entering the

inner chamber: there is in this point no respect for

persons, and rank gives no

precedence,[26] but you do

not move until the bathman, the tellack of the Turks,

the nekaës of the Arabs, the tractator of the Romans,

has passed his hand under your bathing linen, and is

satisfied that your skin is in a proper state. He then

takes you by the arm as before, your feet are again

pushed into the pattens, the slamming door of the

inner region is pulled back, and you are ushered into

the adytum,—a space such as the centre dome of a

cathedral, filled—not with dull and heavy steam—but

with gauzy and mottled vapour, through which the

spectre-like inhabitants appear, by the light of tinted

rays, which, from stars of stained glass in the vault,

struggle to reach the pavement, through the curling

mists. The song, the not unfrequent shout, the clapping,

not of hands, but

sides;[27] the splashing of water

and clank of brazen bowls reveals the humour and

occupation of the inmates, who, here divested of all

covering save the scarf round the loins, with no distinction

between bathers and attendants, and with

heads as bare as bodies and legs, are seen passing to

and fro through the mist, or squatted or stretched

out on the slabs, exhibiting the wildest contortions,

or bending over one another, and appearing to inflict

and to endure torture. A stranger might be in doubt

whether he beheld a foundry or Tartarus; whether

the Athenian gymnasia were restored, or he had entered

some undetected vault of the Inquisition. That

is the sudatorium. The steam is raised by throwing

water on the floor,[28]

and its clearness comes from

the equal temperature of the air and walls.

Under the dome there is an extensive platform of

marble slabs: on this you get up; the clothes are taken

from your head and shoulders; one is spread for you

to lie on, the other is rolled for your head; you lie

down on your back; the tillak (two, if the operation

is properly performed) kneels at your side, and bending

over, gripes and presses your chest, arms, and legs, passing

from part to part, like a bird shifting its place on a

perch. He brings his whole weight on you with a jerk,

follows the line of muscle with anatomical

thumb,[29]

draws the open hand strongly over the surface, particularly

round the shoulder, turning you half up in so

doing; stands with his feet on the thighs and on the

chest and slips down the ribs; then up again three

times; and lastly, doubling your arms one after the

other on the chest, pushes with both hands down, beginning

at the elbow, and then, putting an arm under

the back and applying his chest to your crossed elbows,

rolls on you across till you crack. You are now turned

on your face, and, in addition to the operation above

described, he works his elbow round the edges of

your shoulder-blade, and with the heel plies hard the

angle of the neck; he concludes by hauling the body

half up by each arm successively, while he stands with

one foot on the opposite

thigh.[30]

You are then raised

for a moment to a sitting posture, and a contortion

given to the small of the back with the knee, and a

jerk to the neck by the two hands holding the temples.

3rd Act.—Round the sides there are cocks for

hot and cold water over marble basins, a couple of

feet in diameter, where you mix to the temperature

you wish. You are now seated on a board on the

floor at one of these fountains, with a copper

cup[31] to

throw water over you when wanted. The tellak puts

on the glove—it is of camel’s hair, not the horrid

things recently brought forth in England. He stands

over you; you bend down to him, and he commences

from the nape of the neck in long sweeps down the

back till he has started the skin; he coaxes it into

rolls, keeping them in and up till within his hand they

gather volume and length; he then successively strikes

and brushes them away, and they fall right and left as

if spilt from a dish of macaroni. The dead matter

which will accumulate in a week forms, when dry,

a ball of the size of the fist. I once collected it, and

had it dried—it is like a ball of chalk: this was

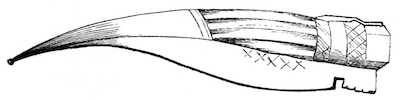

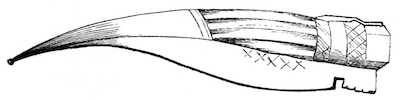

the purpose for which the strigil was used. In our

ignorance we have imagined it to be a horse-scraper to

clear off the perspiration, or for other purposes equally

absurd.[32]

4th Act.—Hitherto soap has not touched the skin.

By it, however strange it may appear to

us,[33] the

operation would be spoiled—the shampooing would

be impossible, and the epidermis would not come off;

this I know by experience. The explanation may be,

that the alkali of the soap combines chemically with

the oily matter, and the epidermis loses the consistency

it must have to be detached by rolling. A large

wooden bowl is now brought; in it is a lump of soap

with a sort of powder-puff of

liff,[34] for lathering. Beginning

by the head, the body is copiously soaped

and washed twice, and part of the contents of the

bowl is left for you to conclude and complete the

operation yourself. Then approaches an acolyte, with

a pile of hot folded futas on his head, he holding a

dry cloth spread out in front—you rise, having detached

the cloth from your waist, and holding it before

you: at that moment another attendant dashes on you

a bowl of hot water. You drop your wet cloth; the

dry one is passed round your waist, another over your

shoulders; each arm is seized; you are led a step or

two and seated; the shoulder cloth is taken off, another

put on, the first over it; another is folded round the

head; your feet are already in the wooden pattens.

You are wished health; you return the salute, rise,

and are conducted by both arms to the outer hall.

I must not here omit all mention of an interlude

in which Europeans take no part. The Mussulmans

get rid of superfluous hair by shaving or

depilation.[35]

The depilatory is composed of orpiment and

quick lime, called in Turkish ot, in Arabic dewa.

The bather retires to a cell without door, but at

the entrance of which he suspends his waist towel;

the bath-man brings him a razor, if he prefers it, or

a lump of the ot about the size of a walnut. In two

or three minutes after applying it the hair is ready

to come off, and a couple of bowls of water leave the

skin entirely bare, not without a flush from the corrosiveness

of the

preparation.[36]

The platform round the hall is raised and divided

by low balustrades into little compartments, where

the couches of repose are arranged, so that while

having the uninterrupted view all round, parties or

families may be by themselves. This is the time and

place for meals. The bather having reached this

apartment is conducted to the edge of the platform,

to which there is only one high step. You drop

the wooden patten, and on the matting a towel is

spread anticipating your foot-fall. The couch is in

the form of a letter

M.[37] spread out, and as you rest

on it the weight is everywhere directly supported—every

tendon, every muscle is relaxed; the mattress

fitting, as it were, into the skeleton: there is total

inaction, and the body appears to be

suspended.[38]

The attendants then re-appear, and gliding like noiseless

shadows, stand in a row before you. The coffee

is poured out and presented: the pipe follows; or,

if so disposed, you may have sherbet or fruit; the

sweet or water melons are preferred, and they come

in piles of lumps large enough for a mouthful; or you

may send and get kebobs on a skewer; and if inclined

to make a positive meal at the bath, this is

the time.

The hall is open to the heavens, but nevertheless

a boy with a fan of feathers, or a napkin, drives the

cool air upon you. The Turks have given up the cold

immersion of the Romans, yet so much as this they

have retained of it, and which realizes the end which

the Romans had in view to prevent the after breaking

out of the perspiration; but it is still a practice

amongst the Turks to have cold water thrown upon

the feet. The nails of hands and feet are dexterously

pared with a sort of oblique chisel; any callosities

that remain on the feet are rubbed down:

during this time the linen is twice

changed.[39] These

operations do not interrupt the chafing of the

soles,[40]

and the gentle putting on of the outside of the folds of

linen which I have mentioned in the first stage. The

body has come forth shining like alabaster, fragrant

as the cistus, sleek as satin, and soft as velvet. The

touch of your own skin is electric. Buffon has a

wonderful description of Adam’s surprise and delight

at his first touch of himself. It is the description

of the human sense when the body is brought back

to its purity. The body thus renewed, the spirit

wanders abroad, and reviewing its tenement rejoices

to find it clean and tranquil. There is an intoxication

or dream that lifts you out of the flesh, and yet

a sense of life and consciousness that spreads through

every member. Each breastful of air seems to pass,

not to the heart but to the brain, and to quench, not

the pulsations of the one, but the fancies of the other.

That exaltation which requires the slumber of the

senses—that vividness of sense that drowns the visions

of the spirit—are simultaneously engaged in calm and

unspeakable luxury: you condense the pleasures of

many scenes, and enjoy in an hour the existence of

years.

But “this too will

pass.”[41] The visions fade, the

speed of the blood thickens, the breath of the pores

is checked, the crispness of the skin returns, the fountains

of strength are opened; you seek again the

world and its toils; and those who experience these

effects and vicissitudes for the first time exclaim, “I

feel as if I could leap over the moon.” Paying

your pence according to the tariff of your deserts,

you walk forth a king from the gates which you

had entered a beggar.

This chief of luxuries is common, in a barbarous

land and under a despotism, to every man, woman,

and child; to the poorest as to the richest, and to the

richest no otherwise and no better than to the

poorest.[42]

But how is it paid for? How can it be within

the reach of the poor? They pay according to their

means. What each person gives is put into a common

stock; the box is opened once a week, and the distribution

of the contents is made according to a scale:

the master of the bath comes in for his share just

like the rest. A person of distinction will give a

pound or more; the common price that, at Constantinople,

a tradesman would pay, was from tenpence

to a shilling, workmen from twopence to threepence.

In a village near Constantinople, where I spent some

months, the charge for men was a

halfpenny,[43] for

women three farthings. A poor person will lay down

a few parahs to show that he has not more to give,

and where the poor man is so treated he will give

as much as he can. He will not, like the poor Roman,

have access alone, but his cup of coffee and a portion

of the service like the

rest.[44] Such rules are not to

be established, but such habits may be destroyed by

laws.

This I have observed, that wherever the bath is

used it is not confined to any class of the community,

as if it was felt to be too good a thing to be

denied to any.

I must now conduct the reader into the Moorish

bath. First, there was no bath linen. They go in naked.

Then there is but one room, under which there is an

oven, and a pot, open into the bath, is boiling on the

fire below. There were no pattens—the floor burning

hot—so we got boards. At once the operation commenced,

which is analogous to the glove. There was a

dish of gazule, for the shampooer to rub his hands in.

I was seated on the board, with my legs straight out

before me; the shampooer seated himself on the same

board behind me, stretching out his legs. He then

made me close my fingers upon the toes of his feet,

by which he got a purchase against me, and rubbing

his hands in the gazule, commenced upon the middle

of my back, with a sharp motion up and down, between

beating and rubbing, his hands working in

opposite directions. After rubbing in this way the

back, he pulled my arms through his own and through

each other, twisting me about in the most extraordinary

manner, and drawing his fingers across the

region of the diaphragm, so as to make me, a practised

bather, shriek. After rubbing in this way the

skin, and stretching at the same time the joints of

my upper body, he came and placed himself at my

feet, dealing with my legs in like manner. Then

thrice taking each leg and lifting it up, he placed his

head under the calf, and raising himself, scraped the

leg as with a rough brush, for his shaved head had

the grain downwards. The operation concluded by

his biting my heel.

The bath becomes a second nature, and long privation

so increases the zest, that I was not disposed to

be critical; but, if by an effort of the imagination I

could transport the Moorish bath to Constantinople,

and had then to choose between the hamâm of Eshi

Serai or my own at home, and this one of the Moors, I

must say, I never should see the inside of a Moorish

bath again. It certainly does clear off the epidermis,

work the flesh, excite the skin, set at work the

absorbent and exuding vessels, raise the temperature,

apply moisture;—but the refinements and

luxuries are wanting.

A great deal of learning has been expended upon

the baths of the ancients, and a melancholy exhibition

it is—so much acuteness and research, and no

profit. The details of these wonderful structures, the

evidences of their usefulness, have prompted no prince,

no people of Europe to imitate them, and so acquire

honour for the one, health for the other. The writers,

indeed, present not living practices, but cold and

ill-assorted details, as men must do who profess to

describe what they themselves do not comprehend.

From what I have said, the identity of the Turkish

bath, with that of the Romans, will be at once

perceived, and the apparent discrepancies and differences

explained. The apodyterium is the mustaby

or entrance-hall; after this comes the sweating-apartment,

subdivided by difference of degrees. Then

two operations are performed, shampooing, and the

clearing off of the epidermis. The Romans had in

the tepidarium and the sudatorium distinct attendants

for the two operations; the first shampooer

receiving the appropriate name of tractator; the

others, who used the strigil, which was equivalent to

the glove, being called suppetones. The appearance of

the strigil in no way alters the character of the

operation. They used sponges also for rubbing down,

like the Moorish gazule. They used no soap; neither

do the Moors;—the Turks use it after the operation

is concluded. The Laconicum I understood when I

saw the Moorish bath, with the pot of water, heated

from the fire below, boiling up into the bath. I

then recollected that there is in the Turkish baths an

opening, by which the steam from the boilers can be

let in, although not frequently so used, nor equally

placed within observation. Many of the Turkish