Title: A patriot lad of old Boston

Author: Russell Gordon Carter

Illustrator: Henry C. Pitz

Release date: September 6, 2023 [eBook #71577]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: The Penn Publishing Company

Credits: Charlene Taylor, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

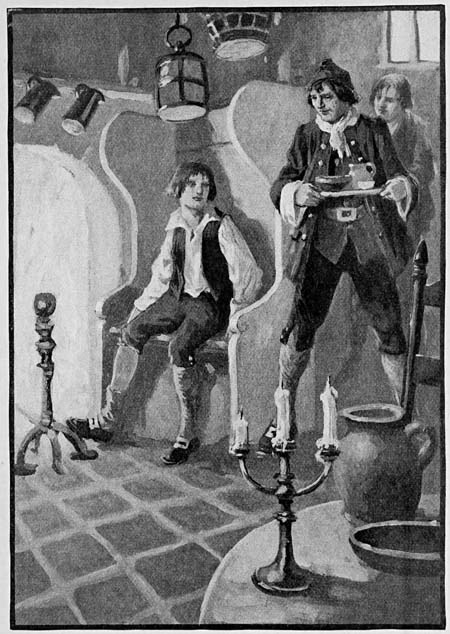

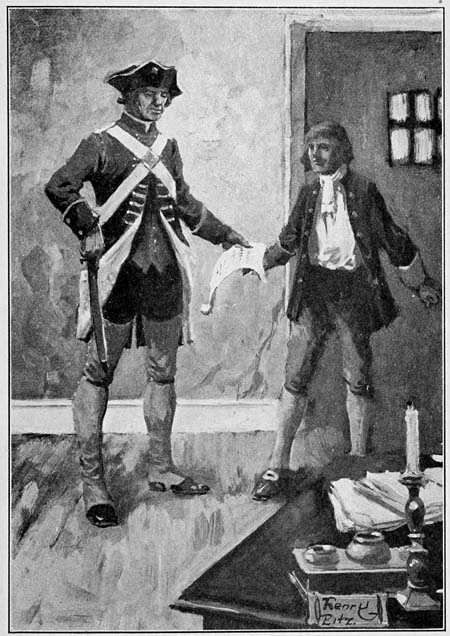

“You Needn’t Be Afraid of This Tea; Nobody’s Paid a Tax on It.”

BY

Russell Gordon Carter

Author of the Bob Hanson Books

Illustrated by HENRY PITZ

THE PENN PUBLISHING

COMPANY PHILADELPHIA

1923

COPYRIGHT

1923 BY

THE PENN

PUBLISHING

COMPANY

A Patriot Lad of Old Boston

Manufacturing

Plant

Camden, N. J.

Made in the U. S. A.

The story of Don Alden is the story of Boston during the British occupation. Like the sturdy out-of-doors boy of to-day, Don was fond of hunting and fishing and trapping; it is of little wonder therefore that Glen Drake, the old trapper from the North, formed an instant liking for him.

But from the moment that the Port Bill went into effect—yes, and before that unfortunate event—there were other things than hunting and fishing to think about. Don’s aunt, a heroic, kindly woman of old New England, refused to leave her home in Pudding Lane, even though the town seemed likely to become a battle ground. And Don was not the boy to forsake his aunt in time of need.

How he helped her during the period of occupation; how he acted when his best friend cast his lot with the Tories; what he did when he suddenly found that he could save the life of one of the hated Redcoats; and what happened at the[4] end when Crean Brush’s Tories forced their way into the house—those events and many others only go to prove that heroism is not limited by age.

There were other things also to test the courage of a lad like Don—the Battles of Concord and Lexington and of Bunker Hill, the felling of the Liberty Tree, and the many small annoyances that both Tories and Redcoats committed to make life a little more miserable for the suffering townsfolk. But he met them all in such a way as to deserve the words of praise from the one man whom he admired more than any other—General Washington.

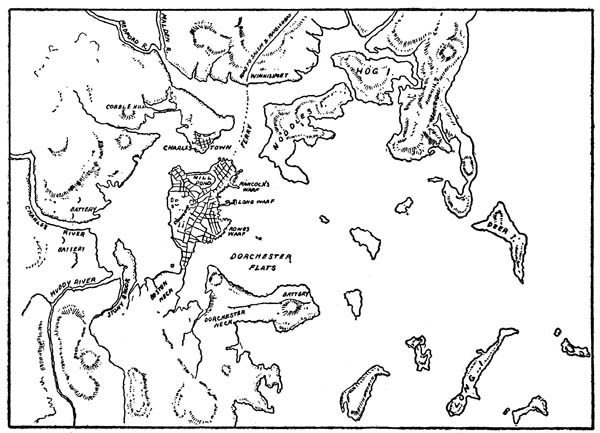

Boston in the days of the Revolution resembled Boston of to-day in one noticeable respect: many of the streets were narrow and crooked and bore the names that they bear at present. But the differences between the old town and the new are many and astonishing. In Revolutionary days mud flats, which were exposed at low water, lay where South Boston and the Back Bay are now situated; near where the present North Station stands there used to be a broad placid mill-pond that extended down almost to Hanover Street; and to the south,[5] where to-day many broad streets and avenues cross one another over a wide space, there used to be a very narrow strip of land known as the Neck—to have cut it would have made of the town an island. Such in brief was the Boston of Donald Alden and of his friends.

If Don is a fictitious hero he is at least typical of many another patriot lad who, too young to serve a great cause under arms, did serve it nevertheless as best he could. How he cared for his Aunt Martha throughout the long trying months of British occupation and in the end foiled Crean Brush’s Tories and performed a service for General Washington makes a story that is well within the beaten paths of history.

The facts of history, taken alone, are likely to seem cold and colorless; regarded from the point of view of a hero in whom we are interested, and whose life they are affecting, they glow with warmth and romance. If readers who follow the adventures of Don find that at the end of the story the Tea Party, Bunker Hill, Lexington and Concord and other important events of history are a little more real to them than they were at first, I shall be content. That is one of the purposes of the book. The other, and perhaps[6] the more important, is simply to provide an interesting story of a boy—a Patriot Lad of Old Boston.

The Author.

| I. | Tea and Salt Water | 11 |

| II. | Don Finds a New Friend | 24 |

| III. | A Redcoat Gets Wet | 36 |

| IV. | A Trip to Concord | 49 |

| V. | The Regulars Come Out | 62 |

| VI. | Across the Flats | 77 |

| VII. | Jud Appleton | 92 |

| VIII. | The Boys Set a Trap | 105 |

| IX. | The Regulars Embark | 116 |

| X. | From a Housetop | 128 |

| XI. | The Liberty Tree | 142 |

| XII. | A Blustering Sergeant-Major | 152 |

| XIII. | A Farce is Interrupted | 162 |

| XIV. | A Broken Lock | 173 |

| XV. | March Winds Blow | 184 |

| XVI. | Crean Brush’s Men | 194 |

| XVII. | Don Meets General Washington | 207 |

[8]

| PAGE | |

| “You Needn’t Be Afraid of This Tea; Nobody’s Paid a Tax on It.” | Frontispiece |

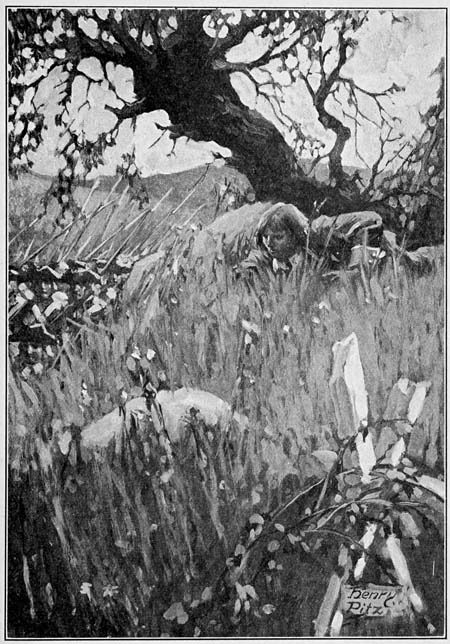

| He Lifted His Head Cautiously and Began to Count | 72 |

| “Who Lives Here Beside Yourself, Young Sire?” | 154 |

A Patriot Lad of Old Boston

A pink and golden sunset was flaming across Boston Common. It was one of the prettiest sunsets of the whole winter of 1773; but on that day, the sixteenth of December, few persons were in the mood to stop and admire it. For trouble had come to town.

In the Old South Meeting-House at the corner of Marlborough and Milk Streets the largest and perhaps the most important town-meeting in the history of Boston was in session. The hall was filled to overflowing, and those who had been unable to gain admittance lingered in the streets and tried to learn from their neighbors what was going on inside.

On the outskirts of the crowd in Milk Street two boys were talking earnestly. “This is a bad piece of business,” said one in a low voice. “What right have we to protest against the[12] King’s sending tea to his colonies? We’re his loyal subjects, aren’t we?”

His companion, an alert-looking boy with blue eyes, did not reply at once; but his eyes flashed as he glanced restlessly now at the meeting-house, now at the persons round him, many of whom he knew. At last he said, “Of course we’re loyal, but we’re not represented in Parliament; for that reason we shouldn’t be taxed. The protest is not against the tea but against the tax that the King has put on it. At least that’s what my Uncle Dave says.”

“Now see here, Don,” replied the boy who had spoken first, “there’s going to be trouble just as sure as you’re born. Take my advice and don’t pick the wrong side.” He lowered his voice. “Keep away from trouble-makers. Men like Sam Adams inside there are a disgrace to the town; and anyway they can’t accomplish anything. There are three shiploads of tea at Griffin’s Wharf; it will be landed to-night, and before many days have passed, you and I will be drinking it—as we should. Don’t be a fool, Don!”

Donald Alden lifted his chin a trifle. “I don’t intend to be a fool, Tom,” he replied slowly.

[13]His companion, Tom Bullard, the son of one of the wealthiest men in town, seemed pleased with the remark, though he certainly was not pleased with what was going on about him. From time to time he scowled as the sound of hand-clapping came from within the meeting-house, or as he overheard some snatch of conversation close by. “Cap’n Rotch,” a tall, rugged-faced man was saying to his neighbor, “has gone with some others to Milton to ask the governor for a clearance.”

“Old Hutchinson will never give it to them,” was the quick reply. “He’s as bad as King George.”

“Well, then, if he doesn’t, you watch out and see what happens.” With that advice the tall man smiled in a peculiar way and a few minutes later left his companion.

Meanwhile the crowd had increased to almost twice the size it had been when Don and Tom had joined it. Don guessed that there were between six and seven thousand people inside the meeting-house and in the streets close by it, and he was astonished at the quiet nature of the gathering. Although everyone around him seemed uneasy and excited, yet they talked in[14] ordinary tones of voice. Occasionally a small boy would shout as he chased another in play, but for the most part even the small boys were content to wait quietly and see what was about to happen; for it seemed that something must happen soon.

Almost all of the pink and gold had faded from the sky, and a light breeze was swaying some of the signs over the doors of the shops on Milk Street and making them creak. There were lights flashing in many of the windows; and inside the Old South Meeting candles were burning.

Don and Tom edged as near as they could to the door, which was partly open. They could hear someone speaking, though the words were indistinct; they could see the heads and shoulders of some of the listeners; they could see grotesque shadows flit about the walls and ceiling as somebody moved in front of the flickering candles. It was long past supper-time, but few persons seemed to have any thought for food.

“I’m cold,” said Tom, “and hungry too. Aren’t you, Don?”

“No,” replied Don.

He lifted his hands to loosen his collar; they[15] were trembling but not with cold. Something must happen soon, he thought.

Somewhere a bell was tolling, and the tones seemed to shiver in the chill air. Half an hour dragged by, slowly. And then there was a sudden commotion near the door of the church, and the buzz of conversation rose to a higher pitch. “It’s Rotch!” exclaimed someone. “It’s Rotch,” said another; “and Governor Hutchinson has refused clearance.”

The crowd pressed closer to the door. Don could see people moving about inside the meeting-house. Then he saw somebody at the far end of the hall lift his hand, and he barely distinguished the words: “This meeting can do nothing more to save the country.”

An instant later there was a shout from someone on the little porch of the church, and then the startling sound of war-whoops rang in Marlborough Street. In a moment the people in the church began to pour out of the door. In Milk Street, near Bishop’s Alley, Don spied half a dozen figures clothed in blankets and wearing feathered head-dresses; their faces were copper-colored, and all of them carried hatchets or axes. Where they had come from no one seemed to[16] have any clear idea, but as they started down the street others joined them; and the crowd followed.

“Where are you going, Don?” Tom asked sharply as his companion turned to join the throng in Milk Street.

“He’s going to have a look at the King’s tea, aren’t you, my lad?” said a voice near by.

“Come on along,” cried Don.

But Tom seized his companion’s arm and held him. “Don, are you crazy?” he demanded. “Keep out of this; it’s trouble; that’s what it is——”

Don jerked his arm free and ran ahead; soon he was lost to Tom in the crowd. At Long Lane he caught a glimpse of bobbing head-dresses. He started to run as best he could. Once he stumbled and fell to his knees, but somebody helped him quickly to his feet. “No time to stumble now,” said the stranger, whoever he was.

A few moments later those at the head of the throng turned sharply to the right, and as they stumbled over the cobblestones down a narrow street Don observed that the moon was shining. In and out among the streets the throng went,[17] past Cow Lane, past Belcher’s Lane and straight toward Griffin’s Wharf. Everyone was excited, and yet there was a certain order about the whole movement.

“Remember what Rowe said in meeting?” remarked a florid-faced man whom Don recognized as a grocer from King Street. “‘Who knows how tea will mingle with salt water?’ Well, I guess we’ll all know pretty quick.”

Don felt his heart take a sudden leap. So they were going to throw the tea overboard! These were no Indians; they were Colonists, all of them! He thought he even recognized one of the leaders as the tall, rugged-faced man in the crowd who had advised his companions to wait and see what would happen if the governor refused the clearance.

Once on the wharf, the first thing the men did was to post guards, and then Don noticed that all of the little copper-colored band had pistols as well as hatchets and axes. The Dartmouth was the first ship to be boarded; someone demanded that the hatches be opened, and the sailors complied with the demand at once; there was no resistance. In a moment square chests with strange markings were being lifted to the deck.[18] Again Don observed that everything was being done in an orderly manner.

It was a night that he should long remember. The tide was low, and the three Indiamen with their high sides and ornamented sterns reminded him of huge dragons lying beside the wharf in the moonlight. He saw chest after chest broken open with axes and hatchets and then tumbled overboard into the water; he heard the low voices of the men as they worked—they seemed to be talking in Indian dialect, though he knew that it was not genuine, for now and again he would catch a word or two of English.

For a while Don leaned against one of the great warehouses and tried to guess who the “Indians” were; at one time he counted as many as fifteen of them, but he could not be sure that there were not more; for at least a hundred persons were on the wharf, helping to get rid of the tea. Some of the chests that they tossed overboard lodged on the mud flats that were out of water, but young men and boys waded in and broke them into pieces and pushed them off. It was fascinating to watch the destruction.

Don remained near the warehouse for perhaps three hours; and not until the last chest had been[19] tossed from the Eleanor and the Beaver, the other two tea vessels, did he realize that he was hungry; he had entirely forgotten that he had missed his supper.

Taking one last glance at the pieces of broken chests, which the turning tide was now carrying out into the harbor, he set forth toward home. At the head of Atkinson Street he heard someone call his name, and, turning, he saw Tom Bullard close behind him. “Oh, Don, wait a minute.”

Don paused. “I can’t wait very long,” he said and grinned. “My Aunt Martha won’t be very well pleased with me as it is.”

“See here, Don,” began Tom abruptly, “I know where you’ve come from, and I know what’s happened down at the wharf. I know also that those men weren’t Indians. The thing I want to ask you is, what do you think of it?”

“Why,” replied Don slowly, “I’m afraid it won’t please you, Tom, if I tell. I think we—that is, the Indians,—did the proper thing in throwing the tea overboard.”

Tom stiffened. “So you’re a young rebel,” he said. “A young rebel! Well, I thought so all along. I’m through with you from now on.”

“I’m sorry, Tom; we’ve been good friends.”

[20]“Well, I’m not sorry,” replied Tom, turning part way round. “A young rebel!” he repeated, flinging the words over his shoulder. “Well, look out for trouble, that’s all.” And he crossed the street.

Don bit his lips. He had lost an old friend; Tom was a Tory. Well, he was not astonished; but he had hoped that their friendship might last through their differences.

He felt somewhat depressed as he made his way along the crooked streets to his aunt’s little house in Pudding Lane. No light was burning in the store at the front where his aunt sold groceries and odds and ends of a household nature to eke out the income of his Uncle David, who was employed at MacNeal’s rope yard on Hutchinson Street. He entered the small sitting-room at the back of the house. “Hello, Aunt Martha,” he said cheerfully.

“Donald Alden, for goodness’ sake, where have you been?” Aunt Martha Hollis dropped the stocking that she had been knitting and adjusted her spectacles.

“Well, first I went up to the town-meeting.”

“Did you see your Uncle David there?”

[21]“No, ma’am; there was an awful big crowd. I’m pretty hungry, Aunt Martha.”

“What happened at the meeting?”

“Well, there was a lot of talking, and then just as it broke up, a band of Indians—that is, a band of men with tomahawks and feathers and colored faces—appeared in Milk Street and started down to Griffin’s Wharf and—is there any pie, Aunt Martha?”

“Donald, go on!” said his aunt, whose fingers had begun to tremble violently.

“They boarded the three tea ships and tossed all the tea into the water. My, you should have seen them! Then they went home. Aunt Martha, I certainly am hungry.”

“Was—was anybody hurt, Donald?”

“Oh, no, ma’am—except one man whom I didn’t know; a chest of tea fell on him. Another man tried to put some of the tea into his pockets, but I guess he was more scared than hurt.”

Aunt Martha drew a deep breath and rose from her chair. In a few minutes she had placed some cold meat and potatoes and a large slice of apple pie on the table. “Now don’t eat too fast,” she cautioned her nephew. Then she[22] seated herself again, but she did not go on with her knitting.

She was a little woman with blue eyes and silvery hair parted in the middle. She was naturally of a light-hearted disposition, though perhaps somewhat overly zealous for the welfare of her only nephew, whom she had taken to live with her eight years ago on the death of both his parents. Now her eyes were gravely thoughtful as she watched him eating.

“This is mighty good pie, Aunt Martha.”

“Well, eat it slowly, then, for that’s all you can have.”

Don grinned and held up his empty plate, and a moment later his aunt went to the kitchen and returned with another piece. As she was setting it on the table, the door opened, and David Hollis entered. He nodded and smiled at his nephew and then strode quickly into the kitchen, where Don heard him washing his hands and face. Then Don heard his aunt and uncle talking in subdued voices. When they entered the sitting-room again Aunt Martha carried more meat and potatoes, which she placed on the table.

Uncle David, big and broad and hearty, sat down opposite his nephew. “So you were at the[23] wharf this evening?” he inquired. “Did you see the—the Indians?”

“I saw feathers and tomahawks and painted faces,” replied Don, and Uncle David laughed and quickly lowered his hands to his lap, but not before his nephew had caught a glimpse of dark red paint round the finger-nails.

“It was a bold thing that the Mohawks did,” said Uncle David. “Don’t ever forget, Donald, that the men who tossed that tea overboard were Indians.”

Don nodded and, turning to his aunt, said, “This is awfully good pie, Aunt Martha. Maybe there’s another piece——”

“Donald! Of course not!” Nevertheless, Aunt Martha went again to the kitchen cupboard.

During the next few days the destruction of the King’s tea was the main topic of conversation in and round Boston. Moreover, bells were rung in celebration of the event, and some persons said frankly that they believed the act to be a stroke toward independence. David Hollis said so one day at the dinner-table.

When he had gone out Aunt Martha turned to her nephew. “Donald,” she said, “your uncle is a good man, a brave man, and he is usually right; but, oh, I do hope that this time he is wrong. Do you realize what it will mean if the Colonies declare their independence of England?”

“It will mean fighting,” Don replied.

“Yes, it will mean—war.” Aunt Martha’s voice trembled. “War between us and our own kinsmen with whom we have been close friends for so long.”

Don thought of Tom Bullard, but he said nothing.

[25]“I do hope that things will be settled peaceably before long,” said his aunt.

Not many days had passed before the inhabitants of Boston learned that tea ships that had tried to land cargoes at New York and at Charleston had fared no better than the three Indiamen at Boston. And again the people of Boston rejoiced, for they were sure that they had done right in destroying the tea.

For a while Don found things very quiet at the little house in Pudding Lane. He went regularly to the Latin School in School Street and after hours frequently helped his aunt to look after the store. He saw Tom Bullard almost every day, but Tom had not a word to say to his former close friend.

One day shortly after Christmas the two boys met unexpectedly near Tom’s house in Hanover Street. Don stopped short. “Say, Tom,” he said, “don’t you think we might be friends again even if we can’t agree on all things?”

“I don’t care to be friendly—with you,” replied Tom shortly.

“Oh, all right, then,” said Don.

For several minutes he was indignant and angry; then he decided that the best thing for[26] him to do would be to forget the quarrel, and from that moment he did not allow it to worry him.

The winter dragged on slowly. January passed, and February came and went. There had been plenty of sledding on the Common; and there were numerous ponds and swamps, where Don tried his new upturned skates that his Uncle David had given him on his birthday.

March was drawing to a close when Don unexpectedly found a new friend. It was Sunday evening, and Aunt Martha and Uncle David and Don were seated in front of a roaring fire on the hearth, when two loud knocks sounded at the door. Before Uncle David could get to his feet it swung open, and a short heavy-set man dressed in deerskin entered.

“Glen Drake!” exclaimed Uncle David. “By the stars, what in the world brings you out of the woods?”

“Oh, I just meandered down,” replied the other, clasping the outstretched hand. “Thought maybe you’d be glad to see me.”

“Glad? I surely am! Here—you know Aunt Martha.” Glen Drake shook hands with[27] Don’s aunt. “And here—this is my nephew Donald.”

Don felt the bones in his hand fairly grate as the man pressed it.

“Draw up a chair, Glen,” said Uncle David.

But Glen Drake had crossed to the door and slipped outside. In a moment he was back, carrying a large bundle in both arms. “A little present for Aunt Martha,” he said and dropped it on the floor in the centre of the room. “There’s a silver fox among ’em.”

“Furs!” cried Don.

“Why, Glen Drake,” began Aunt Martha, “you don’t mean to say——”

“Best year I ever had,” said Glen and, kneeling, cut the thong that bound the bundle.

Don’s eyes seemed fairly to be popping from his head as he watched the old trapper lift pelt after pelt from the closely-packed pile. There must have easily been several thousand dollars’ worth there on the floor. Perhaps one-fourth of the pelts were muskrat; the rest were beaver, otter, mink, martin, sable, ermine and finally the trapper’s greatest prize—a silver fox.

“You don’t mean to say——” Aunt Martha[28] began again. “Why, you surely don’t intend to give me all these!”

At that the old trapper threw back his head and laughed for fully half a minute. “All!” he exclaimed. “Why, bless your heart, Aunt Martha, you should have seen the catch I made. This isn’t one-fifth—no, not one-tenth!”

He seated himself in front of the fire and began to fill his pipe. “Never saw so much fur in my life,” he said.

“Where have you been?” Uncle David asked.

“Up Quebec way and beyond.”

While the two men were talking, Don not only listened eagerly, but studied the visitor closely. He was a short man with broad sloping shoulders and a pair of long heavy arms. His musket, which he had carried in when he went to get the furs, lay beside his coonskin cap on the floor. Though the weapon lay several feet from him, Don was sure that the man could get it in a fraction of a second, if he needed it badly; for he had crossed the floor with the quick noiseless tread of a cat. Now he was lying back in his chair, and his deep-set black eyes seemed to sparkle and burn in the moving light of the fire. His face was like dark tanned leather drawn over high[29] cheek bones; his hair was long and jet black. His pipe seemed twice the size of Uncle David’s when it was in his mouth, but when the trapper’s sinewy hand closed over the bowl it seemed very small. Glen Drake was just the sort of man to catch a boy’s fancy.

All evening Don sat enthralled, listening to the stories the man told of the north, and Aunt Martha had to use all her power of persuasion to send her nephew off to bed. “No more pie for a week, Donald, unless you go this instant,” she said at last.

“You like pie, Don?” asked the trapper. “Well, so do I. And I like boys also, and since I hope to be here for some little time maybe you and I can get to be real friendly.”

“I—I surely hope so!” said Don and turned reluctantly toward the stairs.

He did not go to sleep at once; his room was directly above the sitting-room, and he could hear his uncle and Glen Drake talking until late into the night.

The month that followed was a delightful one for Don. After school hours he and the old trapper would often cross the Neck and go for a long walk through Cambridge and far beyond.[30] The backbone of winter was broken; spring was well along, and the birds had returned from the south. Glen knew them all, by sight and by sound, and he was willing and even eager to teach his companion; he taught him also the habits of the fur-bearing animals and the best ways to trap them; he taught him how to fish the streams, the baits to use and the various outdoor methods of cooking the fish they landed.

“I declare,” said Glen one evening in May when they were returning with a fine mess of fish, “you’re the quickest boy to learn a thing ever I knew. I’m as proud of ye as if you were my own son.”

Don felt a thrill pass over him; he had not expected such praise as that. “I hope I can learn a lot more,” he said.

But that was the last trip the two made into the country together for a long time. On arriving at the house in Pudding Lane, they found Uncle David pacing nervously back and forth across the floor.

“What’s the matter, Dave?” asked Glen.

“Matter enough; haven’t you heard?” Uncle David paused. Then he said with a note of anger in his voice: “I was sure all along that[31] the King would take some means of revenge for the affair of the tea, but it’s worse than I’d suspected. He’s going to close the port.”

Glen Drake whistled softly. Don paused at the foot of the stairs.

“Military governor is coming first,” continued Uncle David, “and troops later—Redcoats!”

“That won’t help the town,” said the trapper.

“You’re right; and it won’t help me; I’ve got a good supply of merchandise in the cellar—cloth mostly and a little powder. Bought it last week from the captain of the Sea Breeze and offered it right off to a friend of mine in Carolina, but can’t send it till I hear from him and know whether he wants it. By that time, though, I’m afraid there won’t be any ships sailing.”

“Sell it here in town,” suggested Glen.

“Can’t do it; my offer was as good as a promise.”

“Send it overland, then, though that would be more expensive, wouldn’t it?”

“Yes, it would be; there wouldn’t be any profit left.”

But during the stress of the next few days Uncle David quite forgot about his merchandise. Captain-General Thomas Gage had arrived in a[32] ship from England; and on the seventeenth of May he landed at Long Wharf and as military governor was received with ceremony. On the first of June, amid the tolling of bells and fasting and prayer on the part of most of the good people of Boston, the Port Bill went into effect. A few days later Governor Hutchinson sailed for England.

Uncle David was moody and preoccupied. He and Glen spent much of their time in the North End, and Don could not help wondering what they were doing there. He and the trapper had become such close friends that he missed his old companion greatly. “Where do they go every evening?” he asked his aunt.

“You must not ask too many questions, Donald,” Aunt Martha replied.

“Well,” said Don, “how long will the port be closed?”

“I don’t know. All I can say is that it is a wicked measure; I declare it is!”

Aunt Martha’s words soon proved to be only too true. Hundreds of vessels, prevented from sailing by the British fleet, lay idle at the wharfs. Hundreds of persons walked the streets, out of work; and many of the very poor people were[33] without bread. Day by day the town seemed to grow a little more miserable. And still Aunt Martha hoped that there would be a peaceful settlement between the Colonies and the mother country. Uncle David and Glen Drake said very little except when they thought they were quite alone.

Don went frequently to the Common, where Redcoats were encamped; in the course of the summer the number of them increased. Barracks had been erected, and cannon had been placed at various points of vantage. It looked as if the British were preparing for a long stay.

Once Don overheard a conversation between two of the soldiers that made his blood boil. He was waiting for a school chum near the Province House, which General Gage was occupying as headquarters, when two Redcoats turned the corner at Rawson’s Lane and stopped near him. “We’ll teach these people how to behave in the future,” said one.

“It’s pretty hard for them,” remarked the other, “having all their trade cut off and having a lot of their liberties taken from them.”

“Hard!” exclaimed the first speaker. “It’s meant to be hard. Everything is done purposely[34] to vex them. They talk of liberty; we’ll show ’em what liberty means. Maybe when they feel the pinch of starvation they’ll come to understand. Maybe they’ll need powder and ball to make them behave, but they’ll behave in the end!”

Don turned away, and from that moment he hoped that a time would come when the people of the Colonies would rise and drive the hated soldiers from the town. If he were only a little older! If he could only do something!

That evening when he returned to Pudding Lane he found the table set for only two persons. “Why, Aunt Martha,” he said, “where are Uncle Dave and Glen?”

“They’ve gone on a trip southward. They won’t return for perhaps a week or two.”

“Oh,” said Don, “did they go to see about the consignment of goods in the cellar?”

“They could see about that,” Aunt Martha replied slowly.

As a matter of fact, the two men had gone on a special trip to New York. For some time they, together with such men as Paul Revere, a silversmith in the North End, William Dawes and others had been meeting in secret at the Green[35] Dragon Tavern; they were part of the Committee of Correspondence, and their object was to watch the British, learn all they could about them—where they kept their guns and powder, how many there were of them at various points—and to convey the information to the other Colonies. Uncle David had ceased work at the rope yard, and if Aunt Martha had known all the details of his doings at the Green Dragon she might have worried even more than she did. His mission now was, among other matters, to inform the Committee of Correspondence at New York of the arrival of a fresh regiment of Redcoats.

In the absence of Glen Drake, Don had formed the habit of going down to the wharves and watching the great ships that lay in forced idleness. The boys that he knew were divided sharply between Whigs and Tories, though most of them were Whigs like himself. So far he had found no one with whom he could be as intimate as he had been with Tom Bullard; so he spent much of his time alone.

On the first day of September, Don was on his way to the water-front when he observed an excited group of sailors and townsmen on the opposite side of the street; they were talking loudly and making violent gestures with their hands. He crossed just in time to hear one of the sailors say: “I was down at Long Wharf and saw them go early this morning—more than two hundred Redcoats in thirteen boats!”

“And they went to Winter Hill,” exclaimed another, “broke open the powder house and carried off two hundred and fifty half-barrels![37] And a second detachment went to Cambridge and brought back two field-pieces that belong to the militia. Thieving Redcoats! It’s high time Congress took some measures to oust ’em!”

“Have patience, Jim,” said a third. “Our time will come, see if it doesn’t.”

“Patience! We’ve shown too much of it already.”

Before Don reached home the news of the raids had spread all over town. People were discussing it on the street corners and in public meeting, and many persons were of a mind to organize at once and recapture as much of the stores as possible.

The Powder Alarm, as it was called, spread rapidly. Messengers from the Committees of Correspondence carried the news to the other Colonies, and the whole country soon blazed with indignation; as a result Lieutenant Governor Oliver and other important officers of the Crown were forced to resign. General Gage began at once to fortify Boston Neck, and then the flame of indignation blazed brighter.

In the midst of the excitement Uncle David and Glen Drake returned with the information that all the people of the other Colonies had “all[38] their eyes turned on Boston.” “We’ll have to open hostilities before long,” Don’s uncle declared. “Human nature can bear just so much—then look out!”

“O David!” cried Aunt Martha. “You seem to be anxious for bloodshed. You do indeed!”

“I’m anxious for justice,” replied Uncle David.

“Ye can torment a critter just so far, Aunt Martha,” said Glen; “then it’ll turn and fight. I don’t care what it is—mink, otter or even a poor little muskrat. And when it does fight it fights like fury. It’s not only human nature, but the nature of every living critter.”

Aunt Martha was silent, and Don, observing the old trapper’s powerful fingers as he tightened the lacing in one of his boots, secretly wished that he were old enough to carry a musket in one of the companies of militia.

Two days later the two men were off on separate missions to the west and south, and again Don was left alone with his aunt.

One Saturday afternoon late in September he took a long walk with his dog, a young terrier that a sailor on one of the ships at Woodman’s[39] Wharf had given him in exchange for three cakes of maple sugar and a set of dominoes. Up past the Faneuil Hall the two went, past the Green Dragon Tavern and along to the shipyard at Hudson’s Point, the dog tugging eagerly at his leash, and Don holding him back.

For a while Don stood in Lynn Street, looking across the water at Charlestown and enjoying the cold wind that was sweeping in from the east. So far he had not found a name for the dog, and he was walking along thoughtfully when he caught sight of a red-coated figure standing at the approach to Ruck’s Wharf and talking with—why, it was Tom Bullard! Don stopped short and then turned to watch the tide, which was sweeping round the point. What was Tom doing, talking with a Redcoat? On second thought Don realized that Tories and Redcoats had only too much in common these days. He was on the point of resuming his walk when he heard someone shout at the end of the wharf, and, turning, he saw a man in a small sloop holding something upraised in his hand. Tom and the soldier started toward the sloop, laughing. Then Don observed that it was a bottle that the man in the boat was holding. “Tom’s found bad company,[40] I’m afraid,” he thought and again resumed his walk.

On coming opposite the end of the wharf, he observed that Tom had gone aboard the sloop; he had crossed on a narrow plank stretched between the boat and the dock. The soldier, a tall, well-built fellow, had started across at a swinging gait. He had passed the middle and was only a few feet from the sloop when, apparently, the narrow plank tilted sidewise. “Look out!” Don heard Tom shout.

The soldier threw out both arms, balanced uncertainly for several seconds, took two short quick steps and then slipped. Don saw the man’s hat fly off and go sailing in the wind. The next instant the soldier struck the water with a tremendous splash.

Tom Bullard stood with open mouth, looking down at the black water that had closed over the head of the soldier. The man with the bottle ran to get a rope, but by the time he reached the gunwale again the soldier reappeared a dozen yards from the bow, uttered a gurgling shout and sank even as the man on board made his cast.

Don’s fingers had tightened round the leash; his eyes were wide, and his breath came quickly.[41] Then, letting go the leash, he ran to the edge of the wharf. He paused and in two swift movements tore off his jacket; then he felt a stab of doubt. What was he thinking of? Save a Redcoat! He thought of his uncle and of Glen Drake; he thought of all the wrongs the town was suffering at the hands of the King’s soldiers—their insolent conduct on the streets, their hatred of the townsfolk. Then he thought of his aunt. That thought settled it. As the tide swept the man to the surface for the third time, Don jumped.

The water was like ice. He strangled as a wave struck him in the face just as his head came to the surface. He caught a glimpse of a dark red mass of cloth a dozen yards at his left; it seemed rapidly to be taking on the color of the water round it. Kicking with all his might, he struck out toward it, swinging his arms with short, quick strokes. Everything was confusion—air, sky, water. A great weight seemed to be pressing against his chest. Then one foot struck something hard. In an instant he had turned and plunged downward. All was water now, black, cold and sinister. His fingers closed on something soft—it might be seaweed. He struggled[42] upward. His lungs seemed on the point of bursting. Upward, upward—then a rush of air and light. A bundle of sodden red cloth came up beside him.

“Grab the wharf!” someone shouted.

But Don did not hear. He took a stroke with his free hand, and at that moment a length of heavy rope whipped down across his arm. Seizing it, he held on. Then he saw that the tide had carried him and his burden against the piling of the next wharf.

“Hold him a moment longer,” said a voice, and then three red-faced sailors lowered themselves like monkeys, and two of them lifted the soldier out of the water. The third caught Don by the back of his shirt and pulled him upward.

On the splintery planks of the wharf, Don blinked his eyes and looked about him. A group of men were carrying the Redcoat into a warehouse.

“How do you feel, my lad?” asked the sailor who had pulled Don from the water.

“C-C-Cold.”

“That’s right, stand up. You did a plucky thing. Too bad the fellow was a Redcoat.”

“Is—is he alive?”

[43]“Oh, yes; he’ll stand parade to-morrow all right. I’m sorry for that. How I hate ’em!”

Don caught a glimpse of Tom Bullard entering the warehouse. Then a low, plaintive cry sounded behind him, and, looking over the edge of the wharf, he saw his terrier in the water. “My pup!” exclaimed Don. “Get him somebody, please!”

A good-sized group of persons had gathered round the boy by that time, and the sailor and two other men hastened to rescue the dog. Once on the wharf, the terrier ran to his young master and began to leap up on him.

“Get the boy to a warm place,” said a lanky fisherman and grasped Don by one arm.

The sailor who had pulled him from the water placed himself on the other side, and together the three of them started down the street at a rapid pace. Soon Don felt a warm glow all over his body; nevertheless his teeth were chattering, and with each puff of strong wind he shivered.

“Wish it had been old Gage instead of a common Redcoat,” the sailor was saying.

“Same here,” replied his companion. “You’d have pushed him under when you pulled the lad out, wouldn’t you, Hank?”

[44]“You’re right, I would have done just that.”

Down one street and into another the three hurried and then paused in front of a tavern with a swinging sign-board that bore the grotesque figure of a green dragon. “Here’s Revere’s place,” said the sailor. “In we go.”

Don soon found himself seated in front of a blazing wood-fire in a large room. It was the first time he had ever entered the Green Dragon Tavern. He glanced round the low-ceilinged room—at the long table, at the rows of pewter on the walls, at the dozen or more chairs with shiny rounded backs. Then he moved as close to the fire as he could with safety, and soon steam was rising from his shoes and stockings. The dog curled up on the hearth and blinked now at the boy, now at the blazing logs.

Hank left the room and returned a few minutes later with a bowl of broth and a cup of strong tea. “You needn’t be afraid of this tea, my lad,” he said and grinned. “Nobody’s paid a tax on it.” He winked at the fisherman. “See if you can find some dry clothes about the place, John.”

Don finished the broth and was sipping the hot[45] tea when a big, rugged-faced man strode into the room, and Don recognized Paul Revere.

“This is the boy,” said John.

“H’m,” said Revere. “David Hollis’s nephew, aren’t you?”

“Yes, sir,” replied Don.

“They tell me you saved a Redcoat.”

“I did, sir,” replied Don. “He couldn’t swim.”

“What’ll your uncle say to that?” The man smiled.

“I’m sure I don’t know.” Indeed the question had occurred to Don several times before. What would Glen Drake say? Don felt his face grow hot; he thought he ought to say something more. “I—wouldn’t pick a Redcoat to save—if I had my choice,” he added.

Revere laughed heartily. “No, I don’t believe you would,” he said. “Well, I’ll have some clothes for you in a trice. Put ’em on in the other room; you can return ’em to-morrow or next day.”

Half an hour later Don said good-bye to Hank and John and set forth toward the house in Pudding Lane. Twilight was coming on, but Don was not sorry for that. He thought of the[46] miserable figure that he must present to passers-by. The coat he wore was several sizes too large for him; he had turned up the sleeves three times, and still they reached to his knuckles. The trousers were so big that he felt as if he were walking in a burlap bag. The hat, which was his own, was wet and misshapen. And at his heels trotted a wet, shivering terrier; no leash was necessary now.

What would his aunt say? And then he happened to remember that the day was Saturday. “Why, I declare,” he said to himself. “Uncle Dave and Glen are expected home to-night.”

He quickened his steps as he crossed the cobblestones on King Street. He was thinking of just how he should begin his story, but suddenly in the midst of his thoughts he stopped and looked at the pup. “I believe I’ve found a name for you!” he said.

The pup wagged his tail.

“I can’t call you Redcoat or soldier, but since it was a sailor I got you of, and a sailor that pulled both of us out of the water, I’m going to call you—Sailor!”

The pup’s tail wagged more vigorously, as if he were content with the name.

[47]Don reached his aunt’s house; there was a light in the store; he entered and passed through to the sitting-room. Uncle David and Glen evidently had been home for some little while, for they were both seated comfortably beside a candle, reading the Massachusetts Spy and the Boston Gazette. They looked up as Don entered, and Aunt Martha, who had just come from the kitchen, dropped a plateful of doughnuts and gave a little cry.

“Where you been, Don, to get such clothes as those?” asked Glen.

“Donald Alden, I couldn’t believe it was you,” said Aunt Martha. “How you frightened me!”

“Scarecrow come to town,” said David Hollis.

Don helped to pick up the doughnuts, adding as he held the last one, “This one’s dirty, Aunt Martha; I’ll eat it.” Then he told what had happened to him on his afternoon walk, and Uncle David’s face glowed while he listened, though Don could not tell whether it was with satisfaction or with anger. “Did I do what was right, Uncle Dave?” he asked when he had concluded the narrative.

David Hollis did not reply at once, but Aunt Martha said quickly, “You did, Donald; but,[48] my dear boy, what a risk you took! Don’t ever do such a thing again—that is,” she hastened to add, “don’t do it unless you have to.” The good lady seemed to be having a hard time adjusting her spectacles.

“Yes,” said Uncle David at last, “your Aunt Martha is right, Don.” He laughed and added, “You did right, but don’t do it again unless you have to.”

Glen Drake nodded and bent over the Gazette.

The next day was Sunday, a bleak, damp day that most of the good people of Boston were content to spend indoors. Snow was falling in large wet flakes that melted almost as soon as they struck the sidewalks. The great elms on the Common tossed their gaunt black branches in the wind; and on the water-front the flakes of snow whirled downward among the spars of the idle shipping and vanished into the black water.

In Pudding Lane, Aunt Martha and the two men had finished dinner, and Don was munching his fourth doughnut, when a knock sounded at the door. “Now who can that be?” asked Don’s aunt.

Uncle David opened the door and disclosed a tall, well-built man in the bright uniform of a British soldier. “Good day to you, sir,” said the Redcoat and took off his hat.

“Good day to you.” David Hollis’s tone was by no means hospitable.

[50]“You have a boy—a boy who is called Donald—Donald Alden, I think.”

Uncle David nodded. “Be so kind as to step inside. The day is bleak.”

The soldier crossed the threshold, and David Hollis closed the door and stood stiffly with his hand on the latch. Glen Drake had stopped in the act of filling his pipe. Aunt Martha’s lips were pursed, and her eyes were wide open. For a moment or two no one spoke. Then the soldier looked at Don, who had hastily swallowed the last of the doughnut. “This boy,” he said, “saved my life yesterday. I should be a most ungrateful man if I allowed the act to pass without a word. Be sure that I am grateful. Harry Hawkins is my name, private in His Majesty’s 43rd Regiment. If I can be of any service to you, Master Donald,” he added with a smile, “I shall be indebted to you until I have performed it.”

“Thank you, sir,” Don replied. “I had no hope of reward when I plunged from the dock.”

The man smiled faintly and turned as if to go.

“You and your fellows might act with a little more consideration for folks who wish only to be left alone in justice,” said Uncle David.

[51]“I am a soldier; I obey my King,” the man replied and stepped to the door. “I wish you all good day.”

David Hollis closed the door behind him.

“I like that fellow for three things,” said Glen Drake abruptly. “He’s grateful to Don here, as he should be; he didn’t offer the lad money for saving his life; and he said what he had to say and then made tracks.”

Aunt Martha nodded and sighed, but Uncle David kept a stubborn silence.

As for Don, he admitted afterward to his aunt that he liked the looks of Harry Hawkins better than he liked the looks of any Redcoat he had ever seen, and that he was really glad that he had been able to save the man’s life. “I like him far better than I like a Tory,” he added with considerable spirit.

Indeed a good many people were far more bitter against the Tories than they were against the Redcoats, who after all had behaved pretty well under somewhat trying conditions. By now, the middle of November, there were eleven regiments of Redcoats, most of which were grouped on and round the Common; there was also artillery; and the following month five hundred[52] marines landed from the Asia. Earl Percy was in command of the army, and a formidable looking force it was, on parade.

But the Colonies also had an army. Uncle David and Glen Drake, on returning from their frequent journeys, brought much news of what was happening outside the town. The conviction was fast becoming general that force and force alone could settle the whole matter; and to that end Alarm List Companies of Minute-Men were being formed in the various towns, and supplies and ammunition were being collected and stored for future use. “By Hector,” Glen remarked on one occasion, “right out here in Danvers the deacon of the parish is captain of the Minute-Men, and the minister is his lieutenant! Donald, if you were only a mite older—but then again maybe it’s best that you’re not.”

By the first of the new year the force of Redcoats in Boston had increased to approximately thirty-five hundred; and, moreover, General Timothy Ruggles, the leader of the Tories, was doing his best to aid the soldiers in every possible way. Tom Bullard, it seems, was acting as a kind of aide to the general and had accompanied[53] him several times on missions to the Tory town of Marshfield.

“I tell you, Don,” said Glen one day, “watching this trouble is a whole lot like watching a forest fire. It started with only a few sparks, like the Stamp Act, you might say; now it’s burning faster and faster every minute. It won’t be long before it blazes up bright, and then it’ll have to burn itself out.”

“How soon is it likely to blaze up?”

“Mighty soon, I’m a-thinking.”

Glen’s estimate was correct. In March the people of Boston saw a marked change in the behavior of the troops. On the fifth of the month, which was the anniversary of the Boston Massacre, the address that Dr. Warren made was hissed by perhaps twoscore of officers who had attended the Old South just for that purpose. And on the sixteenth, a day of fasting and prayer, soldiers of the King’s Own Regiment acted in a way that filled Aunt Martha with indignation.

She and Don had gone to church early. Shortly before the service began, old Mrs. Lancaster, who lived across the way in Pudding Lane, came in and remarked that soldiers were[54] pitching their tents outside. A few minutes later, in the midst of the service, the sounds of fife and drum came from the street. The minister stopped his sermon and looked round him.

Aunt Martha bit her lips, and two bright pink spots showed on her cheeks. “This is scandalous!” she exclaimed.

“It’s downright wicked!” said old Mrs. Lancaster.

The minister went on with the service, raising his voice to make himself heard; but Don, and doubtless many others, had little thought for what was being said inside the church.

At the end of the service many of the people hurried past the soldiers on their way home; but others stood and watched with indignant glances.

That event was only one of many other irritations that followed and inflamed the hearts of the townsfolk.

“Aunt Martha, war has got to come,” said Don.

“Don’t speak of it, Donald,” she replied, and Don glanced once at his aunt’s face and wished that he had held his tongue in the first place; his aunt’s eyes were red and moist.

[55]“All that cloth and powder is still in the cellar, isn’t it?” he asked a while later.

“Yes, Donald; and your uncle intends to keep it there until he can find a satisfactory way of getting it out, though what with all the trouble that surrounds us, I do believe that he doesn’t often give it a thought any more.”

“Seems too bad not to sell it,” said Don.

“Yes, I’ve said so myself, but he always nods and says, ‘Yes, that’s right,’ and then his mind goes wandering off on—on other matters.”

David Hollis, and indeed all the members of the Committees of Correspondence, had many matters to keep them busy. A close watch was being kept on the troops in town. It was known that Gage had sent two officers in disguise to make maps of the roads that led to Boston; and rumor had it that he intended to send a strong force to Concord to capture supplies that the patriots had stored there.

The month of March dragged past with war-like preparations on both sides. Many of the townsfolk, realizing that open hostilities must begin soon, had moved into the country. Samuel Adams and John Hancock had gone to Lexington, where they were staying with the Rev. Jonas[56] Clark. David Hollis and Glen Drake had both made several trips to the town with messages for them.

One day early in April, David Hollis took his wife aside out of hearing of his nephew. “Martha,” he said in a low voice, “I want you to leave the house for a while. There’s going to be trouble, and Boston will be no safe place for you.”

Aunt Martha’s chin lifted a trifle. “And, pray, where should I go?” she asked.

“To Cousin Deborah’s in Concord.”

“I shall not go!” Aunt Martha replied.

“But she has already prepared for you; I told her you’d come.”

“You had no right to say that.”

“But, Martha, listen to reason. I say there will be trouble—I know it! And it’s coming soon. Need I speak plainer than that?”

“No, David, you need not. I understand. Yet I intend to remain right here in our home.”

David Hollis threw out his hands and turned away. Then with another gesture he said, “Martha Hollis, you are a foolish woman. I—I command you to go; it is for your own good.”

Aunt Martha’s blue eyes flashed behind her[57] spectacles. “And I refuse to obey. My place is here, and here is where I stay.” Then with a sudden flash of anger she exclaimed, “I’d like to see any Redcoats drive me from my own home!”

David Hollis turned toward the fire and snapped his fingers several times. “It’s too bad,” he said. “Stubbornness is not a virtue.”

“You have it!”

Uncle David made no reply.

“You tell Cousin Deborah that I’m sorry she has gone to any trouble about me.”

“I don’t expect to go that way very soon.”

“Then Glen can see her.”

“Glen has gone—elsewhere.”

Aunt Martha was thoughtful. “Well,” she said at last, “as you say, it is too bad, but, David, my mind is made up.”

“How would it be to send Donald? Seems to me it might be a good vacation for him. He’s an able lad, and I know that he’d be glad to make the trip. He could ride almost as far as Lexington with Harry Henderson. Cousin Deborah would be glad to have him for overnight.”

“Dear me!” said Aunt Martha. “I can’t allow it.”

[58]But in the end she yielded, and that evening Don heard the news with glee. “Your cousin is a nervous, exact kind of person,” his aunt told him, “and I want you to tell her everything that I say.”

“But what is it?” asked Don.

“Tell her that I am very sorry she has gone to any trouble on my account, but that I cannot with a clear conscience visit with her at this time. Say also that when your uncle promised for me he had not consulted me and therefore did not know all the facts.”

“She’ll want to know the facts,” said Don, grinning. “I’m kind of curious myself, Aunt Martha.”

“Donald!”

But Don’s grin was irresistible, and his aunt smiled. “Never mind,” she said. “And you’ll hurry home, won’t you?”

“I surely will, Aunt Martha.”

The next morning, the sixteenth of April, Don set out with Harry Henderson, a raw-boned young fellow with red hair and a short growth of red stubble on his face. The soldiers had just finished standing parade on the Common when Don and Harry rattled by in the cart; Harry’s[59] light blue eyes narrowed as he watched them moving in little groups to their barracks.

“Good morning to you, young sir,” said a cheerful voice.

Don, looking up, saw Harry Hawkins. “Good morning to you, sir,” he replied.

Harry Henderson looked at his companion narrowly. “Friend of yours?” he asked.

“Well, no, not exactly,” replied the boy.

“Friend of your uncle’s maybe?” Harry was grinning impudently now, and Don’s cheeks were red.

“No; here’s how it is——” And Don gave a brief account of how he had happened to meet the Redcoat.

“Well,” said Harry dryly, “I should think he might say good morning to you.”

They passed the Common and finally turned into Orange Street and, after some delay, drove past the fortifications on the Neck. “Clear of ’em b’gosh!” said Harry, cracking his whip. “We’ll reach Lexin’ton by mid-afternoon if old Dan here doesn’t bust a leg.”

But Harry had not reckoned on horseshoes. Shortly before they reached Medford, old Dan lost a shoe, and the circumstance caused a delay[60] of two hours. Then later Dan shied at a barking dog and snapped one of the shafts. As a result Harry and Don did not reach Lexington until almost ten o’clock.

“You’ve got to stay right here with me,” said Harry, “It’s too late for you to reach Concord. I know your cousin, and she wouldn’t be at all pleased to have you wake her at midnight—not she!” He laughed.

So Don remained at Lexington overnight and the next morning set out on foot for Concord. He reached his cousin’s house just before noon.

Cousin Deborah was a tall strong-looking woman with black hair, black eyes and a nose that was overly large. She had once been a school teacher and, as David Hollis used to say, had never lost the look. “Where’s your Aunt Martha?” were her first words to Don.

“She decided she couldn’t come.”

“But Uncle David told me——”

Then followed the inevitable questions that a person like Cousin Deborah would be sure to ask, and Don wriggled under each of them. But after all, Cousin Deborah was good-hearted, and deep within her she knew that she would have done the same as Don’s aunt was doing, if she[61] had been in similar circumstances—though she would not acknowledge it now. “Your aunt always did have a broad streak of will,” she said severely. “Now I want you to spend several days with me, Donald.”

“Aunt Martha told me to hurry back.”

“That means you can stay to-night and to-morrow night,” Cousin Deborah decided. “I’ll have dinner in a few moments, and then I want you to tell me all the things that have happened in Boston.”

In spite of his cousin’s questions, which were many and varied, Don managed to enjoy himself while he was at Concord. On the second day he met a boy of his own age, and the two fished all morning from the North Bridge. In the afternoon they went on a long tramp into the woods along the stream.

At night Don was tired out and was glad when his cousin finally snuffed the candles and led the way up-stairs. He was asleep shortly after his head struck the pillow.

That night proved to be one of the most eventful in the history of the Colonies.

While Don was asleep, breathing the damp, fragrant air that blew over the rolling hills and fields round Concord, his friend, Paul Revere, was being rowed cautiously from the vicinity of Hudson’s Point toward Charlestown. It was then near half-past ten o’clock.

Revere, muffled in a long cloak, sat in the stern of the small boat and glanced now at his two companions—Thomas Richardson and Joshua Bentley—and now at the British man-of-war, Somerset, only a few rods off. The tide was at young flood, and the moon was rising. The night seemed all black and silver—black shadows ahead where the town of Charlestown lay, black shadows behind that shrouded the wharfs and shipyards of the North End, and silver shimmering splashes on the uneasy water and on the sleek spars of the Somerset.

The sound of talking came from the direction of the man-of-war and was followed by a burst of[63] laughter that reverberated musically in the cool night air. Revere blew on his hands to warm them. The little boat drew nearer, nearer to Charlestown; now he could see the vague outlines of wharfs and houses. Several times he glanced over his shoulder in the direction of a solitary yellow light that gleamed in the black-and-silver night high among the shadows on the Boston side,—a light that burned steadily in the belfry of the Old North Meeting-House behind Corps Hill as a signal that the British were on their way by land to attack the Colonists.

“Here we are,” said one of the rowers, shipping his muffled oar and partly turning in his seat.

A few minutes later the boat swung against a wharf, and the two men at the oars held it steady while Revere stepped out. A brief word or two and he was on his way up the dock. In the town he soon met a group of patriots, one of whom, Richard Devens, got a horse for him. Revere lost no time in mounting and setting off to warn the countryside of the coming of the Redcoats.

He had not gone far beyond Charlestown Neck, however, when he almost rode into two[64] British officers who were waiting in the shadows beneath a tree. One of them rode out into the middle of the path; the other charged full at the American. Like a flash Revere turned his horse and galloped back toward the Neck and then pushed for the Medford road. The Redcoat, unfamiliar with the ground, had ridden into a clay pit, and before he could get his horse free Revere was safely out of his reach.

At Medford he roused the captain of the Minute-Men; and from there to Lexington he stopped at almost every house along the road and summoned the inmates from their beds. It was close to midnight when he reached Lexington. Riding to the house of the Rev. Jonas Clark, where Hancock and Adams were staying, he found eight men on guard in command of a sergeant.

“Don’t make so much noise!” cried the fellow as Revere clattered up to the gate.

“Noise!” repeated Revere in a hoarse voice. “You’ll have noise enough here before long—the regulars are coming out!”

At that moment a window opened, and Hancock thrust his head out. “Come in, Revere!” he said. “We’re not afraid of you!”

[65]Revere dismounted and hurried inside. In a few words he told his story, that the British were on their way either to capture Hancock and Adams or to destroy the military stores at Concord. While he was talking, William Dawes, who also had set out to warn the people, clattered up to the door.

After he and Revere had had something to eat and to drink they started for Concord and were joined by a Dr. Prescott, whom Don had seen once or twice in company with his uncle. With Revere in the lead the party rode on at a rapid pace.

About half-way to Concord, while Prescott and Dawes were rousing the people in a house near the road, Revere spied two horsemen ahead. Turning in his saddle, he shouted to his companions, and at that moment two more horsemen appeared.

Prescott came riding forward in answer to the shout, and he and Revere tried to get past the men, all of whom were British officers. But the four of them were armed, and they forced the Americans into a pasture. Prescott at once urged his horse into a gallop, jumped a stone wall and, riding in headlong flight, was soon safe[66] on his way to Concord. Revere urged his horse toward a near-by wood, but just before he reached it six British officers rode out, and he was a prisoner.

“Are you an express?” demanded one of them.

“Yes,” replied Revere and with a smile added: “Gentlemen, you have missed your aim. I left Boston after your troops had landed at Lechemere Point, and if I had not been certain that the people, to the distance of fifty miles into the country, had been notified of your movements I would have risked one shot before you should have taken me.”

For a moment no one spoke; it was clear that the Redcoats were taken aback. Then followed more questions, all of which Revere answered truthfully and without hesitating. Finally they ordered their prisoner to mount, and all rode slowly toward Lexington. They were not far from the meeting-house when the crash of musketry shook the night air.

For an instant the major who was in command of the party thought they had been fired on. Then he remarked to the officer beside him, “It’s the militia.”

[67]The officer laughed shortly and glanced at their prisoner. Then the party halted, and the British took Revere’s horse. The major asked him how far it was to Cambridge and, on being told, left the prisoner standing in the field and with the rest of the party rode toward the meeting-house.

A few minutes later Revere crossed the old burying-ground and entered the town. He soon found Hancock and Adams again and told them what had happened, and they concluded to take refuge in the town of Woburn. Revere went with them. He had done his duty.

Perhaps it was a vague feeling of impending danger, perhaps it was the mere twitter of a bird outside his window—at any rate Don awoke with a start. All was darkness in the room. A light, cool wind stirred the branches of the great elm at the side of the house; he could hear the twigs rubbing gently against the rough shingles. He had no idea what time it was; it must be after midnight, he thought; but somehow he was not sleepy. He raised his head a trifle. Down-stairs a door slammed; that seemed strange. Now someone was talking. “I wonder——” he said to himself and then sat bolt upright in bed.

[68]The church bell had begun to ring at a furious rate. Clang, clang! Clang—clang! Don thought he had never before heard a bell ring so harshly or so unevenly. He jumped out of bed and began to dress. Clang! Clang! What in the world could be the matter? He could hear shouts now and the sound of hastening footsteps. In his excitement he got the wrong arm into his shirt. Clang! Clang—clang! He found his shoes at last and with trembling fingers got them on his feet. He unlatched the door and started carefully down the winding stairs. It seemed as if there were a hundred steps to those creaking old stairs. Twice he almost missed his footing—and all the while the bell continued to clash and ring and tremble.

In the sitting-room a single candle was burning. Don got a glimpse of his cousin Deborah, hastily dressed and still wearing her nightcap; she was standing at the door, and his Cousin Eben, with a musket in his hand and a powder horn over his shoulder, was saying good-bye. Don saw him kiss his wife. Then the door opened, the candle flickered, and he was gone.

“Cousin Deborah, what’s wrong?” cried Don.

[69]“The regulars are coming!” And then Cousin Deborah burst into tears.

Don bit his lips; he had never thought of his cousin as being capable of tears.

They did not last long. A few movements of her handkerchief and Cousin Deborah seemed like herself again. “Donald,” she said, “they have begun it, and the good Lord is always on the side of the right. Now I want you to go back to bed and get your rest.”

“Are you going back to bed, Cousin Deborah?”

“No; there will be no sleep for me this night.”

“Then I shall remain up also,” replied Don.

Cousin Deborah made no protest but went to the stove and poked the fire.

The bell had ceased ringing now. The town of Concord was wide awake.

While Don and his cousin were eating a hastily prepared breakfast the Minute-Men and the militia assembled on the parade ground near the meeting-house. Meanwhile other patriots were hard at work transporting the military stores to a place of safety.

Dawn was breaking, and the mist was rising from the river when Don and his cousin finally[70] got up from the table. “Now, Donald,” said Cousin Deborah, “I’ve been thinking all along of your Aunt Martha and blaming myself for my selfishness in having you stay here with me for so long. I’d give most anything if you were back there with her. And yet——” She paused frowning.

“Oh, I can get back all right,” said Don confidently.

“How?”

“Why, by keeping off the roads as much as possible. I know the country pretty well.”

“You’re a bright lad, Donald,” said Cousin Deborah. “You’re a bright lad; and I don’t know but what you’d better start. Your aunt needs you more than I do. But oh, Donald, you’ll be cautious!”

“I don’t think I ought to leave you here alone.”

“Drat the boy!” exclaimed his cousin and then smiled. “Bless you, Donald,” she added, “I’ll be safe enough. I shall go to Mrs. Barton’s until things are quiet again. Now go and get yourself ready.”

Don needed only a few moments in which to get his things together. Then he walked with[71] his cousin as far as Mrs. Barton’s house, which was situated some distance beyond the North Bridge, bade her good-bye and started back. It was growing lighter every minute now, and the birds were singing in all the trees. On the road he met a Minute-Man who was hurrying in the opposite direction, and asked him the news.

“Regulars fired on our boys at Lexin’ton,” replied the fellow as he hurried past. Over his shoulder he shouted, “Killed six of ’em—war’s begun!”

Don said not a word in reply, but stood stock still in the road. For some reason a great lump had come into his throat, and he thought of his Aunt Martha. He must get to her as quickly as possible.

As he came near the North Bridge he saw the Provincial troops—the Minute-Men and the militia of the town and detachments of Minute-Men from some of the outlying towns; and all the while fresh soldiers were hurrying to swell the numbers. The British, he soon learned, were on their way to Concord, and several companies of Provincials had gone out to meet them.

Don left the town and struck off into the open country several hundred yards from the Lexington[72] road. After a few minutes of rapid walking he saw the detachment of Americans coming back. He quickened his pace and finally broke into a run.

He had gone something more than a mile and a half when he suddenly stopped and threw himself on the ground. There on the road, marching steadily in the direction of Concord, was a large force of regulars. He could see the flash of metal and the bright red of their coats. For a while he lay there, panting. Then at last, spying a great rock with a hollow just behind it, he crept toward it and waited.

The long column advanced slowly. Now Don could hear the crunch of their feet on the hard road. He lifted his head cautiously and began to count; there must easily be a thousand Redcoats. The crunching grew louder as the head of the column came almost opposite to him. Now he could hear the rattle of equipment and the occasional jangling of a sword.

He Lifted His Head Cautiously and Began to Count.

It was some time before the rear of the column had passed. He waited until it was perhaps a quarter of a mile up the road and then got to his feet. He ought not to have much trouble in reaching Boston if he started at once. He[73] was about to resume his journey when a fresh thought came to him. Ought he to go without knowing what was to happen to the town of Concord—and to his Cousin Deborah? For at least five minutes he struggled with the question. “No, I oughtn’t!” he declared at last and, turning suddenly, began to retrace his steps.

It was close to seven o’clock when the regulars, in two columns, marched into Concord and sent a party over the North Bridge into the country. Don found a clump of spruces growing on a hillside and climbed into the lower branches of one of them. From that position he could see the scattered houses and the two bridges, though the distance was too great for him to be able to distinguish features or even the outlines of anybody in the town.

Part of the King’s force seemed to have disbanded, and later when Don heard the ring of axes he suspected that they were destroying the stores that had not been carried away. “Well,” he thought, “they won’t be able to destroy much.”

But when he distinguished blue smoke curling upward from several places near the centre of the town he almost lost his grip on the branch to[74] which he was clinging. One of them was the court-house! Where was the militia? Where were the Minute-Men? He made out the peaked roof of his cousin’s house and the great elm standing beside it, and observed with some satisfaction that no Redcoats were close to it. Then a while later he saw the thread of smoke above the court-house grow thinner, and at last it disappeared altogether.

Don held his position in the tree for more than an hour. He ground his teeth as he saw a detachment of soldiers leave the town and cut down the liberty pole on the side of the hill. Where were the Minute-Men and the militia?

The main body of the regulars was well inside the town. At the South Bridge there was a small party on guard, and at the North Bridge was another party of about one hundred. Don was so much occupied with watching the Redcoats that he had failed to observe a long double column of Provincials coming down the hill beyond the North Bridge; they were moving at a fast walk and carried their guns at the trail.

At first glance he thought there were no more than a hundred of them, but as he watched he was forced to conclude that there were at least three[75] hundred. He pulled himself farther out on the limb and waited.

The detachment of regulars, who were on the far side of the bridge, hastily retired across it and prepared for an attack. When the Provincials were a few rods distant the Redcoats opened fire, then waited and fired again, and Don saw two men fall. Then he saw a succession of bright flashes and heard the crash of arms as the Provincials returned the fire. Several of the enemy fell. Then there was more firing, and in a few minutes the British left the bridge and ran in great haste toward the main body, a detachment from which was on the way to meet them. The Provincials pursued the regulars over the bridge and then divided; one party climbed the hill to the east, and the other returned to the high grounds.

Don found himself trembling all over; he felt sick and dizzy. With much difficulty he reached the ground, where he lay for a few minutes. On getting to his feet, he saw the Redcoats who had first crossed the North Bridge returning. In the town there seemed to be much confusion; the sun glanced on red coats and polished trimmings as men hurried here and there.

[76]Don would not trust himself to climb the tree again, but threw himself on the ground at the foot of it. He would rest for a while and then set out on his long journey back to Boston, fairly confident that his cousin had not been harmed. He had not slept a wink since some time between one and two o’clock in the morning; now it was after ten o’clock. So when his head began to nod he did not try very hard to fight off sleep.

Don was wakened by the sound of firing. He sat up and rubbed his eyes; then, looking at the sun, he guessed that twelve o’clock had passed. He could see nothing of the Redcoats; nor could he see smoke anywhere inside the town. From the east came the sound of firing that had wakened him, and men with muskets were hurrying across fields in that direction. For a moment he thought of returning to his Cousin Deborah’s; then he decided to push for Boston as fast as he could.

Half running, half walking, he made his way in a southeasterly direction in order to avoid the main road. Once he wondered whether the Redcoat Harry Hawkins was with this expedition of British troops, but somehow the thought was painful, and he turned his mind to other things.

For some time he had been climbing a rocky hillside; now, on reaching the crest, he got his last glimpse of the skirmish. The British were in the road just outside of Lexington, and, far[78] off as Don was, he could see plainly that they were having a hard time of it. He could see the flash of sabres as if the officers were urging their men to advance. One officer was prancing here and there on a spirited black horse, as if he had lost control of the animal. Then Don saw part of the King’s troops open fire and saw a dozen or more muskets flash in reply along an old stone wall on the opposite side of the road. Before he heard the reports of them he saw the black horse fall. Another glance and he saw a company of Minute-Men crossing a distant field at a rapid pace. The sight of a battle going on almost under his nose, the sound of guns, the smell of powder, all seemed to hold him spell-bound, and only the thought of his Aunt Martha alone in the little house in Pudding Lane caused him to turn and hurry on his way.

Soon he was out of hearing of the firing, but from time to time he saw detachments of Minute-Men and militia marching to the east. Once he stopped at a solitary farmhouse and asked for something to eat. A woman who was alone except for a little girl of nine or ten years gave him bread and cheese and then prepared a small bundle of the food for him to take along.

[79]Don told her what he had seen at Concord and at Lexington, and her lips quivered; but she smiled at him. “Such a day!” she exclaimed. “My husband and my three brothers have gone. It seems that all the men from the village have gone. I have heard that the town of Dedham is almost empty; even the company of gray-haired old veterans of the French Wars has gone. Such a day! Be careful, my boy, and return to your aunt as soon as possible.”

Don thanked her for her kindness as he was leaving the house, and soon he was hurrying on his way toward Boston. From Glen Drake he had learned many of the secrets of woodcraft and had little trouble in making his way through the thickets in the vicinity of Fresh Pond. But mishaps will sometimes overtake the best of woodsmen. As Don was descending a slope on the western side of the pond he stepped on a loose stone, which turned under his weight and sent him crashing headlong to the bottom. He lay there with teeth set and both hands clenched; a sharp pain was throbbing and pounding in his right ankle. Little drops of perspiration stood out like beads on his forehead.

For several minutes he lay there; then as the[80] pain decreased in violence he sat up. But later when he rose he found that he dared not put any weight at all on his right foot. Here was a predicament! There was not a house in sight; he was a long way from the nearest road; and night was coming on.

He tried to climb the slope down which he had slid, but the effort only sent sharp pains shooting up his leg. Even when he crawled for only a dozen yards or so on his hands and knees the pain would force him to stop; it seemed that he could not move without giving the ankle a painful wrench. Several times he shouted for help, but he had little hope that anybody would be in that vicinity to hear him. So at last he dragged himself to a little cove that was overgrown with birches and willows; there he loosened his shoe and rubbed his swollen ankle.

“Well,” he said to himself, “I’ve got to stay here all night, and I haven’t a thing except my knife and——” He interrupted himself with an exclamation; his knife was not in his pocket. Then he remembered that he had left it at his Cousin Deborah’s.

The missing knife made his situation even more desperate than he had supposed it was. With[81] a knife he might have fashioned a bow such as he had once seen Glen Drake use for lighting a fire; as it was, he should have to keep warm as best he could.