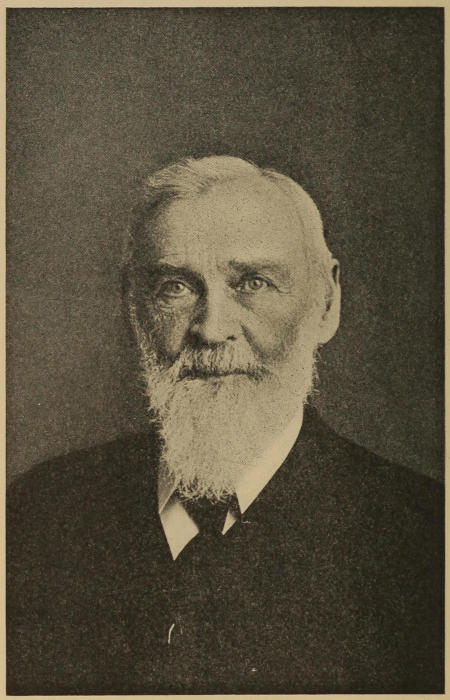

C. W. MATEER

Title: Calvin Wilson Mateer, forty-five years a missionary in Shantung, China

a biography

Author: D. W. Fisher

Release date: September 20, 2023 [eBook #71695]

Most recently updated: October 14, 2023

Language: English

Credits: Brian Wilson and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

C. W. MATEER

Calvin Wilson Mateer

FORTY-FIVE YEARS A MISSIONARY

IN SHANTUNG, CHINA

A BIOGRAPHY

BY DANIEL W. FISHER

PHILADELPHIA

THE WESTMINSTER PRESS

1911

Copyright, 1911, by

The Trustees of the Presbyterian Board of

Publication and Sabbath School Work

Published September, 1911

| PAGE | |

| Introduction | 9 |

| CHAPTER I | |

| The Old Home | 15 |

| Birth—The Cumberland Valley—Parentage—Brothers and Sisters, Father, Mother, Grandfather—Removal to the “Hermitage”—Life on the Farm—In the Home—Stories of Childhood and Youth. | |

| CHAPTER II | |

| The Making of the Man | 27 |

| Native Endowments—Influence of the Old Home—A Country Schoolmaster—Hunterstown Academy—Teaching School—Dunlap’s Creek Academy—Profession of Religion—Jefferson College—Recollections of a Classmate—The Faculty—The Class of 1857—A Semi-Centennial Letter. | |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Finding His Life Work | 40 |

| Mother and Foreign Missions—Beaver Academy—Decision to be a Minister—Western Theological Seminary—The Faculty—Revival—Interest in Missions—Licentiate—Considering Duty as to Missions—Decision—Delaware, Ohio—Delay in Going—Ordination—Marriage—Going at Last. | |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Gone to the Front | 57 |

| Bound to Shantung, China—The Voyage—Hardships and Trials on the Way—At Shanghai—Bound for Chefoo—Vessel on the Rocks—Wanderings on Shore—Deliverance and Arrival at Chefoo—By Shentza to Tengchow. | [vi] |

| CHAPTER V | |

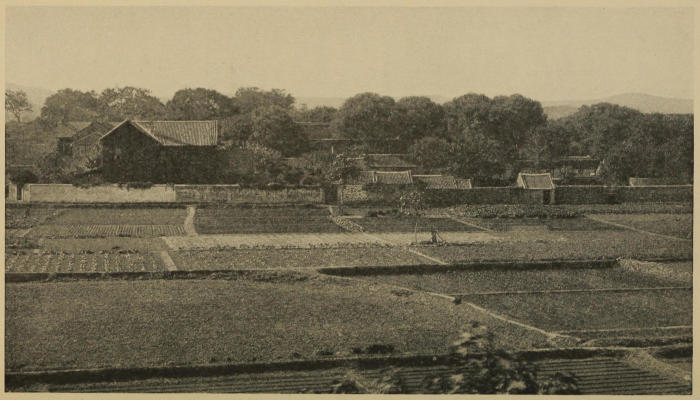

| The New Home | 70 |

| The Mateer Dwelling—Tengchow as It Was—The Beginning of Missions There—The Kwan Yin Temple—Making a Stove and Coal-press—Left Alone in the Temple—Its Defects—Building a New House—Home Life. | |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| His Inner Life | 88 |

| Not a Dreamer—Tenderness of Heart—Regeneration—Religious Reserve—Record of Religious Experiences—Depression and Relief—Unreserved Consecration—Maturity of Religious Life—Loyalty to Convictions. | |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Doing the Work of an Evangelist | 105 |

| Acquiring the Language—Hindrances—Beginning to Speak Chinese—Chapel at Tengchow—Province of Shantung—Modes of Travel—Some Experiences in Travel—First Country Trip—Chinese Inns—A Four Weeks’ Itineration—To Wei Hsien—Hatred of Foreigners—Disturbance—Itinerating with Julia—Chinese Converts—To the Provincial Capital and Tai An—Curtailing His Itinerations—Later Trips. | |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| The Tengchow School | 128 |

| The School Begun—Education and Missions—First Pupils—Means of Support—English Excluded—Growth of School—A Day’s Programme—Care of Pupils—Discipline—An Attempted Suicide—Conversion of a Pupil—First Graduates—Reception After Furlough—An Advance—Two Decades of the School. | [vii] |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| The Press and Literary Labors | 150 |

| Contributions to the Periodicals—English Books—The Shanghai Mission Press—Temporary Superintendency—John Mateer—Committee on School Books—Earlier Chinese Books—School Books—Mandarin Dictionary—Mandarin Lessons—Care as to Publications—Pecuniary Returns. | |

| CHAPTER X | |

| The Care of the Native Christians | 173 |

| Reasons for Such Work—The Church at Tengchow—Discipline—Conversion of School Boys—Stated Supply at Tengchow—Pastor—As a Preacher—The Scattered Sheep—Miao of Chow Yuen—Ingatherings—Latest Country Visitations—“Methods of Missions”—Presbytery of Shantung—Presbytery in the Country—Synod of China—Moderator of Synod—In the General Assembly. | |

| CHAPTER XI | |

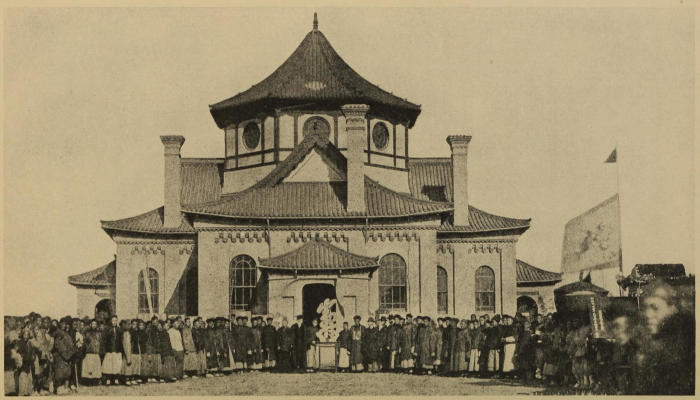

| The Shantung College | 207 |

| “The College of Shantung”—The Equipment—Physical and Chemical Apparatus—Gathering the Apparatus—The Headship Laid Down—The Anglo-Chinese College—Problem of Location and Endowment—Transfer of College to Wei Hsien—A New President—“The Shantung Christian University”—Personal Removal to Wei Hsien—Temporary President—Official Separation—The College of To-day. | |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| With Apparatus and Machinery | 236 |

| Achievements—Early Indications—Self-Development—Shop—Early Necessities—As a Help in Mission Work—Visitors—Help to Employment for Natives—Filling Orders—A Mathematical Problem—Exhibitions. | [viii] |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| The Mandarin Version | 252 |

| First Missionary Conference—The Chinese Language—Second Missionary Conference—Consultation as to New Version of Scriptures—The Plan—Selection of Translators—Translators at Work—Difficulties—Style—Sessions—Final Meeting—New Testament Finished—Lessons Learned—Conference of 1907—Translators of the Old Testament. | |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| Incidents by the Way | 275 |

| Trials—Deaths—The “Rebels”—Tientsin Massacre—Japanese War with China—Boxer Uprising—Famine—Controversies—English in the College—Pleasures—Distinctions and Honors—Journeys—Furloughs—Marriage—The Siberian Trip—Scenes of Early Life. | |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| Facing the New China | 305 |

| The Great Break-Up—Past Anticipations—A Maker of the New China—Influence of Missionaries—Present Indications—Dangers—Duties—Future of Christianity. | |

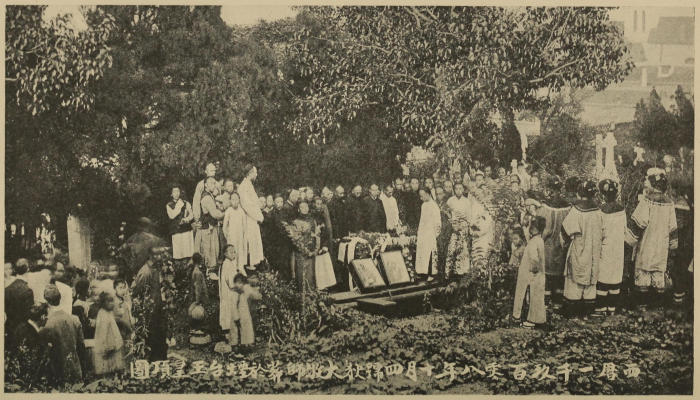

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| Called Up Higher | 319 |

| The Last Summer—Increasing Illness—Taken to Tsingtao—The End—A Prayer—Service at Tsingtao—Funeral at Chefoo—Tributes of Dr. Corbett, Dr. Hayes, Dr. Goodrich, Mr. Baller, Mrs. A. H. Mateer—West Shantung Mission—English Baptist Mission—Presbyterian Board—Secretary Brown—Biographer—“Valiant for the Truth.” | |

It is a privilege to comply with the request of Dr. Fisher to write a brief introduction to his biography of the late Calvin W. Mateer, D.D., LL.D. I knew Dr. Mateer intimately, corresponded with him for thirteen years and visited him in China. He was one of the makers of the new China, and his life forms a part of the history of Christian missions which no student of that subject can afford to overlook. He sailed from New York in 1863, at the age of twenty-eight, with his young wife and Rev. and Mrs. Hunter Corbett, the journey to China occupying six months in a slow and wretchedly uncomfortable sailing vessel. It is difficult now to realize that so recently as 1863 a voyage to the far East was so formidable an undertaking. Indeed, the hardships of that voyage were so great that the health of some members of the party was seriously impaired.

Difficulties did not end when the young missionaries arrived at their destination. The people were not friendly; the conveniences of life were few; the loneliness and isolation were exceedingly trying; but the young missionaries were undaunted and pushed their work with splendid courage and faith. Mr. Corbett soon became a leader in evangelistic[10] work, but Dr. Mateer, while deeply interested in evangelistic work and helping greatly in it, felt chiefly drawn toward educational work. In 1864, one year after his arrival, he and his equally gifted and devoted wife managed to gather six students. There were neither text-books, buildings, nor assistants; but with a faith as strong as it was sagacious Dr. and Mrs. Mateer set themselves to the task of building up a college. One by one buildings were secured, poor and humble indeed, but sufficing for a start. The missionary made his own text-books and manufactured much of the apparatus with his own hands. He speedily proved himself an educator and administrator of exceptional ability. Increasing numbers of young Chinese gathered about him. The college grew. From the beginning, Mr. Mateer insisted that it should give its training in the Chinese language, that the instruction should be of the most thorough kind, and that it should be pervaded throughout by the Christian spirit. When, after thirty-five years of unremitting toil, advancing years compelled him to lay down the burden of the presidency, he had the satisfaction of seeing the college recognized as one of the very best colleges in all Asia. It continues under his successors in larger form at Wei Hsien, where it now forms the Arts College of the Shantung Christian University.

Dr. Mateer was famous not only as an educator, but as an author and translator. After his retirement from the college he devoted himself almost[11] wholly to literary work, save for one year, when a vacancy in the presidency of the college again devolved its cares temporarily upon him. His knowledge of the Chinese language was extraordinary. He prepared many text-books and other volumes in Chinese, writing some himself and translating others. The last years of his life were spent as chairman of a committee for the revision of the translation of the Bible into Chinese, a labor to which he gave himself with loving zeal.

Dr. Mateer was a man of unusual force of character; an educator, a scholar and an executive of high capacity. Hanover College, of which Dr. D. W. Fisher was then president, early recognized his ability and success by bestowing upon him the honorary degree of Doctor of Divinity, and in 1903 his alma mater added the degree of Doctor of Laws. We mourn that the work no longer has the benefit of his counsel; but he builded so well that the results of his labors will long endure, and his name will always have a prominent place in the history of missionary work in the Chinese empire.

Dr. Fisher has done a great service to the cause of missions and to the whole church in writing the biography of such a man. A college classmate and lifelong friend of Dr. Mateer, and himself a scholar and educator of high rank, he has written with keen insight, with full comprehension of his subject, and with admirable clearness and power. I bespeak for this volume and for the great work in[12] China to which Dr. Mateer consecrated his life the deep and sympathetic interest of all who may read this book.

Arthur Judson Brown

156 Fifth Avenue, New York City, April 13th, 1911

When I was asked to become the biographer of Dr. Mateer, I had planned to do other literary work, and had made some preparation for it; but I at once put that aside and entered on the writing of this book. I did this for several reasons. Though Dr. Mateer and I had never been very intimate friends, yet, beginning with our college and seminary days, and on to the close of his life, we had always been very good friends. I had occasionally corresponded with him, and, being in hearty sympathy with the cause of foreign missions, I had kept myself so well informed as to his achievements that I had unusual pleasure in officially conferring on him the first of the distinctions by which his name came to be so well adorned. As his college classmate, I had joined with the other survivors in recognizing him as the one of our number whom we most delighted to honor. When I laid down my office of college president, he promptly wrote me, and suggested that I occupy my leisure by a visit to China, and that I use my tongue and pen to aid the cause of the evangelization of that great people. Only a few months before his death he sent me extended directions for such a visit. When—wholly unexpectedly—the invitation came to me to prepare his biography, what could I do but respond favorably?

It has been my sole object in this book to reveal[14] to the reader Dr. Mateer, the man, the Christian, the missionary, both his inner and his outer life, just as it was. In doing this I have very often availed myself of his own words. Going beyond these, I have striven neither to keep back nor to exaggerate anything that deserves a place in this record. All the while the preparation of this book has been going forward in my hands my appreciation of the magnitude of the man and of his work has been increasing. Great is the story of his career. If this does not appear so to any reader who has the mind and the heart to appreciate it, then the fault is mine. It, in that case, is in the telling, and not in the matter of the book, that the defect lies.

So many relatives and acquaintances of Dr. Mateer have contributed valuable material, on which I have drawn freely, that I dare not try to mention them here by name. It is due, however, to Mrs. J. M. Kirkwood to acknowledge that much of the chapter on “The Old Home” is based on a monograph she prepared in advance of the writing of this biography. It is due also to Mrs. Ada H. Mateer to acknowledge the very extensive and varied assistance which she has rendered in the writing of this book: first, by putting the material already on hand into such shape that the biographer’s labors have been immensely lightened, and later, by furnishing with her own pen much additional information, and by her wise, practical suggestions.

D. W. F.

Washington, 1911

“There are all the fond recollections and associations of my youth.”—JOURNAL, March 4, 1857.

Calvin Wilson Mateer, of whose life and work this book is to tell, was born in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, near Shiremanstown, a few miles west of Harrisburg, on January 9, 1836.

This Cumberland valley, in which he first saw the light, is one of the fairest regions in all our country. Beginning at the great, broad Susquehanna, almost in sight of his birthplace, it stretches far away, a little to the southwest, on past Chambersburg, and across the state line, and by way of Hagerstown, to its other boundary, drawn by a second and equally majestic stream, the historic Potomac. Physically considered, the splendid Shenandoah valley, still beyond in Virginia, is a further extension of the same depression. It is throughout a most attractive panorama of gently rolling slopes and vales, of fertile and highly cultivated farms, of great springs of purest water and of purling brooks, of little parks of trees[16] spared by the woodman’s ax, of comfortable and tasteful rural homes, of prosperous towns and villages where church spires and school buildings and the conveniences of modern civilization bear witness to the high character of the people,—all of this usually set like a picture in a framework of the blue and not very rugged, or very high, wooded mountains between which, in their more or less broken ranges, the entire valley lies.

True, it was winter when this infant first looked out on that world about him, but it was only waiting for spring to take off its swaddling of white, and to clothe it with many-hued garments. Twenty-eight years afterward, almost to the very day, he, cast ashore on the coast of China, was struggling over the roadless and snow covered and, to him, wholly unknown ground toward the place near which he was to do the work of his life, and where his body rests in the grave. When he died, in his seventy-third year, the spiritual spring for which he had prayed and longed and labored had not yet fully come, but there were many indications of its not distant approach.

John Mateer, the father of Calvin, was born in this beautiful Cumberland valley, on a farm which was a part of a large tract of land entered by the Mateers as first settlers, out of whose hands, however, it had almost entirely passed at the date when this biography begins. The mother of Calvin was born in the neighboring county of York. Her maiden name was[17] Mary Nelson Diven. Both father and mother were of that Scotch-Irish descent to which especially Pennsylvania and Virginia are indebted for so many of their best people; and they both had behind them a long line of sturdy, honorable and God-fearing ancestors.

At the time of Calvin’s birth his parents were living in a frame house which is still standing; and though, with the passing of years, it has much deteriorated, it gives evidence that it was a comfortable though modest home for the little family.

One of the employments of his father while resident there was the running of a water mill for hulling clover seed; and Calvin tells somewhere of a recollection that he used to wish when a very little boy that he were tall enough to reach a lever by which he could turn on more water to make the mill go faster,—a childish anticipation of his remarkable mechanical ability and versatility in maturer years.

Calvin was the oldest of seven children—five brothers and two sisters; in the order of age, Calvin Wilson, Jennie, William Diven, John Lowrie, Robert McCheyne, Horace Nelson and Lillian, of whom Jennie, William, Robert and Horace are still living. Of these seven children, Calvin and Robert became ministers of the gospel in the Presbyterian Church, and missionaries in Shantung, China; John for five years had charge of the Presbyterian Mission Press at Shanghai, and later of the Congregational Press at Peking, where he died; Lillian taught in the Girls’[18] School at Tengchow, and, after her marriage to Rev. William S. Walker, of the Southern Baptist Mission, in the school at Shanghai, until the failing health of her husband compelled her to return to the United States; William for a good while was strongly disposed to offer himself for the foreign missionary service, and reluctantly acting on advice, turned from it to business. Jennie married an exceptionally promising young Presbyterian minister, and both offered themselves to the foreign work and were under appointment to go to China when health considerations compelled them to remain in their homeland. Some years after his death she married a college professor of fine ability. Horace is a professor in the University of Wooster, and a practicing physician.

In view of this very condensed account of the remarkable life and work of the children in this household, one may well crave to know more about the parents, and about the home life in the atmosphere of which they were nurtured. Their father and mother both had the elementary education which could be furnished in their youth by the rural schools during the brief terms for which they were held each year. In addition, the mother attended a select school in Harrisburg for a time. Both father and mother built well on this early foundation, forming the habit of wise, careful reading. Both were professing Christians when they were married, and in infancy Calvin was baptized in the old Silver Spring Church, near which they resided. Later the father[19] became a ruling elder in the Presbyterian church to which they had removed their membership. In this capacity he was highly esteemed, his pastor relying especially on his just, discerning judgment. He had a beautiful tenor voice and a line musical sense, and he led the choir for a number of years. Few laymen in the church at large were better informed as to its doctrines and history, and few were more familiar with the Bible. There was in the church a library from which books were regularly brought home; religious papers were taken and read by the whole family, and thus all were acquainted with the current news of the churches, and with the progress of the gospel in the world.

In the conduct of his farm Mr. Mateer was thrifty, industrious and economical. His land did not yield very bountifully, but all of its products were so well husbanded that notwithstanding the size of his family he yet accumulated considerable property. Though somewhat reluctant at first to have his boys one after another leave him, thus depriving him of their help on the farm, he aided each to the extent of his ability, and as they successively fitted themselves for larger lives he rejoiced in their achievements.

Mr. Mateer died at Monmouth, Illinois, in 1875. When the tidings reached Calvin out in China, he wrote home to his mother a beautiful letter, in which among other things he said: “Father’s death was eminently characteristic of his life—modest, quiet and self-suppressed. He died the death of the[20] righteous and has gone to a righteous man’s reward. The message he sent John and me was not necessary; that he should ‘die trusting in Jesus’ was not news to us, for we knew how he had lived.”

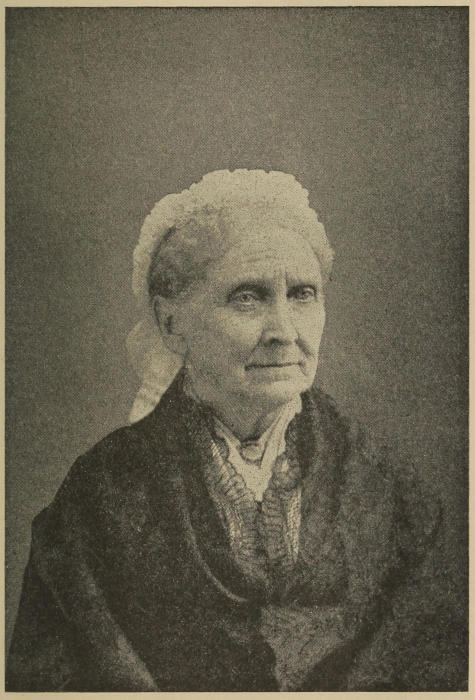

DR. MATEER’S MOTHER

By reading the records that have been at my command I have gotten the conviction that the mother was the stronger character, or at least that she more deeply impressed herself on the children. When Calvin made his last visit to this country, he was asked whose influence had been most potent in his life, and he at once replied, “Mother’s.” In his personal appearance he strongly resembled her. If one could have wished for any change in his character, it might have been that he should have had in it just a little bit more of the ideality of his father, and just a little bit less of the intense realism of his mother. Some of his mother’s most evident characteristics were in a measure traceable as an inheritance from her father, William Diven; for example, the place to which she assigned education among the values of life. He was a man of considerable literary attainments, for his day, and for one residing out in the country; so that when in later years he came to make his home with the Mateers he brought with him a collection of standard books, thus furnishing additional and substantial reading for the family. Even Shakspere and Burns were among the authors, though they were not placed where the children could have access to them, and were made familiar to them only by the grandfather’s quotation of choice passages.[21] When his daughter was a little girl, so intense was his desire that she should have as good an education as practicable, that if the weather was too inclement for her to walk to the schoolhouse he used to carry her on his back. It was her lifelong regret that her education was so defective; and it is said that after she was seventy years of age, once she dreamed that she was sent to school at Mount Holyoke, and she awoke in tears to find that she was white-haired, and that it was only a dream. Although it involved the sacrifice of her own strength and ease, she never faltered in her determination that her children should have the educational advantages to which she had aspired, but never attained; and in what they reached in this direction she had a rich satisfaction. Toward every other object which she conceived to be good and true, and to be within the scope of her life, she set herself with like persistence, and strength, and willingness for self-sacrifice. Her piety was deep, thorough and all-controlling; but with her it was a principle rather than a sentiment. Its chief aim was the promotion of the glory of the infinitely holy God, though as she neared the visible presence of her Saviour, this softened somewhat into a conscious love and faith toward him. She survived her husband twenty-one years, and died at the advanced age of seventy-nine. When the tidings of this came to her children in China, their chief lament was, “How we shall miss her prayers!”

When Calvin was about five years old, his parents[22] bought a farm twelve miles north of Gettysburg, near what is now York Springs, in Adams County. It is some twenty miles from the place of his birth, and beyond the limits of the Cumberland valley. Even now it is a comparatively out-of-the-way spot, reached only by a long drive from the nearest railway station; then it was so secluded that the Mateers called the house into which they removed the “Hermitage.” Here the family continued to reside until about the time of Calvin’s graduation from college. Then a second and much longer move was made, to Mercer County, in western Pennsylvania. Still later, a third migration brought them to Illinois. It is to the home in Adams County that Calvin refers in the line quoted at the head of this chapter, as the place where “were all the fond recollections and associations” of his youth.

The farm was not very large, and the soil was only moderately productive, notwithstanding the labor and skill that the Mateers put upon it. In picking off the broken slate stones which were turned up thick by the plow, the children by hard experience were trained in patient industry as to small details. At least the two elder frequently beguiled the tedium of this task “by reciting portions of the Westminster Catechism and long passages of Scripture.” Another really tedious occupation, which, however, was converted into a sort of late autumn feast of ingathering, was shared by the whole family, but was especially appreciated by the children. This was the nut[23] harvest of the “shellbark” hickory trees of the forest. As many as fifty or more bushels were gathered in a season; the sale of these afforded a handsome supplement to the income of the household. Along the side of the farm flows a beautiful stream, still bearing its Indian name of Bermudgeon, and in front of the house is a smaller creek; and in these Calvin fished and set traps for the muskrats, and experimented with little waterwheels, and learned to swim. Up on an elevation still stand the old house and barn, both constructed of the red brick once so largely used in the eastern section of Pennsylvania. Both of these are still in use. Though showing signs of age and lack of care, they are witnesses that for those days the Mateers were quite up to the better standard of living customary among their neighbors. “This growing family,” says Mrs. Kirkwood (Jennie), “was a hive of industry, making most of the implements used both indoors and out, and accomplishing many tasks long since relegated to the factory and the shop. Necessity was with them the mother not only of invention, but of execution as well. All were up early in the morning eating breakfast by candlelight even in summer, and ready before the sun had risen for a day’s work that continued long after twilight had fallen.” In the barn they not only housed their horses and cattle and the field products, but also manufactured most of the implements for their agricultural work. Here Calvin first had his mechanical gifts called into exercise, sometimes on sleds and wagons and farm[24] tools, and sometimes on traps and other articles of youthful sport.

In this home family worship was held twice each day,—in the morning often before the day had fully dawned, and in the evening when the twilight was vanishing into night. In this service usually there were not only the reading of Scripture and the offering of prayer, but also the singing of praise, the fine musical voice of the father and his ability to lead in the tunes making this all the more effective. Of course, on the Sabbath the entire family, young and old, so far as practicable, attended services when held in the Presbyterian church not far away. But that was not all of the religious observances. The Sabbath was sacredly kept, after the old-fashioned manner of putting away the avoidable work of the week, and of giving exceptional attention to sacred things. Mrs. Kirkwood, who was near enough in age to be the “chum” of Calvin, writes: “Among the many living pictures which memory holds of those years, there is one of a large, airy, farmhouse kitchen, on a Sabbath afternoon. The table, with one leaf raised to afford space for ‘Scott’ and ‘Henry’ stands between two doors that look out upon tree-shaded, flower-filled yards. There sits the mother, with open books spread all about her, studying the Bible lesson for herself and for her children. Both parents and children attended a pastor’s class in which the old Sunday School Union Question Book was used. In this many references were given which the children were required to commit.[25] Older people read them from their Bibles, but these children memorized them. Some of the longer ones could never be repeated in after times without awakening associations of the muscularizing mental tussles of those early days.” It was a part of the religious training of each child in that household, just as soon as able to read, to commit to memory the Westminster Shorter Catechism,—not so as to blunder through the answers in some sort of fashion, but so as to recite them all, no matter how long or difficult, without mistaking so much as an article or a preposition.

Stories are handed down concerning the boy Calvin at home, some of which foreshadow characteristics of his later years. One of these must suffice here. The “Hermitage,” when the Mateers came into it, was popularly believed to be haunted by a former occupant whose grave was in an old deserted Episcopal churchyard about a mile away. The grave was sunken, and it was asserted that it would not remain filled. It was also rumored that in the gloomy woods by which the place was surrounded a headless man had been seen wandering at night. Nevertheless the Mateer children often went up there on a Sabbath afternoon, and entered the never-closed door, to view the Bible and books and desk, which were left just as they had been when services long before had ceased to be held; or wandered about the graves, picking the moss from the inscriptions on the headstones, in order to see who could find the oldest. It was a[26] place that, of course, was much avoided at night; for had not restless white forms been seen moving about among these burial places of the dead? The boy Calvin had been in the habit of running by it in the late evening with fast-beating heart. One dark night he went and climbed up on the graveyard fence, resolved to sit in that supremely desolate and uncanny spot till he had mastered the superstitious fear associated with it. The owls hooted, and other night sounds were intensified by the loneliness, but he successfully passed his chosen ordeal, and won a victory worth the effort. In a youthful way he was disciplining himself for more difficult ordeals in China.

“It has been said, and with truth, that when one has finished his course in an ordinary college, he knows just enough to be sensible of his own ignorance.”—LETTER TO HIS MOTHER, January 15, 1857.

The letter from which the sentence at the head of this chapter is taken was written a week after Mateer had reached his twenty-first year and when he was almost half advanced in his senior year in college. Later in the letter he says: “Improvement and advancement need not, and should not, stop with a college life. We should be advancing in knowledge so long as we live.” With this understanding we may somewhat arbitrarily set his graduation from college as terminating the period of his life covered by what I have designated as “the making of the man.”

Back of all else lay his native endowments of body and of mind. Physically he was exceptionally free from both inherited and acquired weaknesses. In a letter which he wrote to his near relatives in this country on the occasion of his seventieth birthday, he said, “I have not only lived, but I have enjoyed an exceptional measure of health.” At no period was he laid aside by protracted sickness. At the same[28] time, this must not be understood to signify that he had one of those iron constitutions that seem to be capable of enduring without harm every sort of exposure except such as in its nature must be mortal. In that part of his Journal covering portions of his college and seminary work he often tells of a lassitude for which he blames himself as morally at fault, but in which a physician would have seen symptoms of a low bodily tone. Bad food, lack of exercise and ill treatment on the voyage which first brought him to China left him with a temporary attack of dyspepsia. Occasionally he had dysentery, and once he had erysipelas. At no time did he regard himself as so rugged in constitution that he did not need to provide himself with proper clothing and shelter, so far as practicable. Nevertheless it was because of the sound physique inherited from his parents, and fostered by his country life during early youth, that without any serious breaking down of health or strength he was able to endure the privations and the toils and cares of his forty-five years in China.

As to his native mental endowments, no one would have been more ready than he to deny that he was a “genius,” if by this is meant that he had an ability offhand to do important things for the accomplishment of which others require study and effort. If, as to this, any exception ought to be made in his favor, it would be concerning some of the applied sciences and machinery, and possibly mathematics. He certainly had an extraordinary aptitude especially as to the[29] former of these. While he himself regarded his work in the Mandarin as perhaps the greatest of his achievements, he had no such talent for the mastery of foreign languages that he did not need time and toil and patience to learn them. In college his best standing was not in Latin or Greek. In China other missionaries have been able to preach in the native tongue after as short a period of preparation; and the perfect command of the language which he attained came only after years of ceaseless toil.

Such were his native physical and mental endowments: a good, sound, though not unusually rugged, bodily constitution; and an intellect vigorous in all of its faculties, which was in degree not so superior as to set him on a pedestal by himself, yet was very considerably above the average even of college students.

Concerning the qualities of his heart and of his will it is best to wait and speak later in this volume.

In the making of a man native endowments are only the material out of which and on which to build. Beyond these, what we become depends on our opportunities and the use to which we put them. The atmosphere of the old home had much to do with the unfolding of the subsequent life and character of Mateer. Some of his leading qualities were there grown into his being.

Other powerful influences also had a large share in his development. About three quarters of a mile from the “Hermitage” stood a township schoolhouse,[30] a small brick building, “guiltless alike of paint or comfort,” most primitive in its furnishing, and open for instruction only five or six months each year, and this in the winter. The pressure of work in the house and on the farm never was allowed to interrupt the attendance of the Mateer children at this little center of learning for the neighborhood. Of course, the teachers usually were qualified only to conduct the pupils over the elementary branches, and no provision was made in the curriculum for anything beyond these. But it so happened that for two winters Calvin had as his schoolmaster there James Duffield, who is described by one of his pupils still living as “a genius in his profession, much in advance of his times, and quite superior to those who preceded and to those who came after him. In appearance Duffield was awkward and shy. His large hands and feet were ever in his way, except when before a class; then he was suddenly at ease, absorbed in the work of teaching, alert, full of vitality, with an enthusiasm for mastery, and an intellectual power that made every subject alive with interest, leaving his impress upon each one of his pupils.” Algebra was not recognized as falling within the legitimate instruction, and no suspicion that any boy or girl was studying it entered the minds of the plain farmers who constituted the official visitors. One day a friend of the teacher, a scholarly man, came in at the time when the examinations were proceeding, and the teacher sprang a surprise by asking this friend whether he would like[31] to see one of his pupils solve a problem in algebra. He had discerned the mathematical bent of the lad, Calvin Mateer, and out of school hours and just for the satisfaction of it he had privately been giving the boy lessons in that study. When an affirmative response was made by the stranger, Calvin went to the blackboard and soon covered half of it with a solution of an algebraic problem. Surprised and delighted, the stranger tested the lad with problem after problem, some of them the hardest in the text-book in use, only to find him able to solve them. It would have been difficult to discover which of the three principal parties to the examination, the visitor, the teacher, or the pupil, was most gratified by the outcome. There can be no question that this country school-teacher had much to do with awakening the mathematical capabilities and perhaps others of the intellectual gifts which characterized that lad in manhood and throughout life.

When Calvin was in his seventeenth year, he started in his pursuit of higher education, entering a small academy at Hunterstown, eight miles from the “Hermitage.” In this step he had the stimulating encouragement of his mother, whose quenchless passion for education has already been described. His father probably would at that time have preferred that he should remain at home and help on the farm; and occasionally, for some years, the question whether he ought not to have fallen in with the paternal wish caused him serious thought. As it was, he came home[32] from the academy in the spring, and in the autumn and also at harvest, to assist in the work.

The first term he began Latin, and the second term Greek, and he kept his mathematics well in hand, thus distinctly setting his face toward college. But his pecuniary means were narrow, and in the winter of 1853-54 he had to turn aside to teach a country school some three miles from his home. In a brief biographical sketch which, by request of his college classmates, he furnished for the fortieth anniversary of their graduation he says: “This was a hard experience. I was not yet eighteen and looked much younger. Many of the scholars were young men and women, older than I, and there was a deal of rowdyism in the district. I held my own, however, and finished with credit, and grew in experience more than in any other period of my life.”

When the school closed he returned to the academy, which by that time had passed into the hands of S. B. Mercer, in whom he found a teacher of exceptional ability, both as to scholarship and as to the stimulation of his students to do and to be the best that was possible to them. In the spring of 1855 Mr. Mercer left the Hunterstown Academy, and went to Merrittstown, Fayette County, Pennsylvania, where he took charge of the Dunlaps Creek Academy. Calvin, influenced by his attachment to his teacher, and also by his intention to enter Jefferson College, situated in a neighboring county, went with him. Here he made his home, with other students, in the[33] house occupied by the Mercers. For teaching two classes, one in geometry and one in Greek, he received his tuition. For the ostensible reason that he had come so far to enter the academy he was charged a reduced price for his board. All the way down to the completion of his course in the theological seminary he managed to live upon the means furnished in part from home, and substantially supplemented by his own labors; but he had to practice rigid economy. It was while at Merrittstown that he made a public profession of religion. This was only a few months before he entered college. He found in Dr. Samuel Wilson, the pastor of the Presbyterian church, a preacher and a man who won his admiration and esteem, and who so encouraged and directed him that he took this step.

In the autumn of 1855 he entered the junior class of Jefferson College, at Canonsburg, Pennsylvania. In those days it was customary for students to be admitted further advanced as to enrollment than at present. I had myself preceded Mateer one year, entering as a sophomore in the same class into which he first came as a junior. One reason for this state of things was that the requirements were considerably lower than they now are; and they were often laxly enforced. Then, because the range of studies required was very limited in kind, consisting until the junior year almost exclusively of Latin, Greek and mathematics, it was possible for the preparatory schools to carry the work of their students well up into the[34] curriculum of the college. Mateer had the advantage, besides, of such an excellent instructor as Professor Mercer, and of experience in teaching. He says: “I was poorly prepared for this class, but managed to squeeze in. The professor of Latin wanted me to make up some work which I had not done; but I demurred, and I recollect saying to him, ‘If after a term you still think I ought to make it up, I will do it, or fall back to the sophomore class.’ I never heard of it afterwards. I was very green and bashful when I went to college, an unsophisticated farmer’s boy from a little country academy. I knew little or nothing of the ways of the world.”

As his classmate in college, and otherwise closely associated with him as a fellow-student, I knew him well. I remember still with a good deal of distinctness his appearance; he was rather tall, light-haired, with a clear and intelligent countenance, and a general physique that indicated thorough soundness of body, though not excessively developed in any member. When I last saw him at Los Angeles a few years ago, I could perceive no great change in his looks, except such as is inevitable from the flight of years, and from his large and varied experience of life. It seems to me that it ought to be easy for any of his acquaintances of later years to form for themselves a picture of him in his young manhood at the college and at the theological seminary. So far as I can now recall, he came to college unheralded as to what might be expected of him there. He did not thrust himself[35] forward; but it was not long until by his work and his thorough manliness, it became evident that in him the class had received an addition that was sure to count heavily in all that was of importance to a student. I do not think that he joined any of the Greek letter secret societies, though these were at the height of their prosperity there at that time. In the literary societies he discharged well and faithfully his duties, but he did not stand out very conspicuously in the exercises required of the members. In those days there was plenty of “college politics,” sometimes very petty, and sometimes not very creditable, though not wholly without profit as a preparation for the “rough-and-tumble” of life in after years, but in this Mateer did not take much part. Most of us were still immature enough to indulge in pranks that afforded us fun, but which were more an expression of our immaturity than we then imagined; and Mateer participated in one of these in connection with the Frémont-Buchanan campaign in 1856. A great Republican meeting was held at Canonsburg, and some of us students appeared in the procession as a burlesque company of Kansas “border ruffians.” We were a sadly disgraceful-looking set. Of one thing I am sure, that while Mateer gave himself constantly to his duties and refrained from most of the silly things of college life, he was not by any of us looked upon as a “stick.” He commanded our respect.

The faculty was small and the equipment of the college meager. The attendance was nearly three[36] hundred. As to attainments, we were a mixed multitude. To instruct all of these there were—for both regular and required work—only six men, including one for the preparatory department. What could these few do to meet the needs of this miscellaneous crowd? They did their best, and it was possible for any of us, especially for the brighter student, to get a great deal of valuable education even under these conditions. Mateer in later years acknowledges his indebtedness to all of the faculty, but particularly to Dr. A. B. Brown, who was our president up to the latter part of our senior year; to Dr. Alden, who succeeded him; and to Professor Fraser, who held the chair of mathematics. Dr. Brown was much admired by the students for his rhetorical ability in the pulpit and out of it. Dr. Alden was quite in contrast to his predecessor as to many things. He had long been a teacher, and was clear and concise in his intellectual efforts. Mateer said, late in life, that from his drill in moral science he “got more good than from any other one branch in the course.” Professor Fraser was a brilliant, all-round scholar of the best type then prevalent, and had the enthusiastic admiration even of those students who were little able to appreciate his teaching. In the physical sciences the course was necessarily still limited and somewhat elementary. His classmates remember the evident mastery which Mateer had of all that was attempted by instruction or by experimentation in that department. It was not possible to get much of what is called “culture”[37] out of the curriculum, and that through no fault of the faculty; yet for the stimulation of the intellectual powers and the unfolding of character there was an opportunity such as may be seriously lacking in the conditions of college instruction in recent years.

These were the palmy days of Jefferson College. She drew to herself students not only from Pennsylvania and the contiguous states, but also from the more distant regions of the west and the south. We were dumped down there, a heterogeneous lot of young fellows, and outside of the classroom we were left for the most part to care for ourselves. We had no luxuries and we were short of comforts. We got enough to eat, of a very plain sort, and we got it cheap. We were wholly unacquainted with athletics and other intercollegiate goings and comings which now loom up so conspicuously in college life; but we had, with rare exceptions, come from the country and the small towns, intent on obtaining an education which would help us to make the most of ourselves in after years. As to this, Mateer was a thoroughly representative student. He could not then foresee his future career, but he was sure that in it he dared not hope for success unless he made thoroughly good use of his present, passing opportunities. He was evidently a man who was there for a purpose.

The class of 1857 has always been proud of itself, and not without reason. Fifty-eight of us received our diplomas on commencement. Among them were such leaders in the church as George P. Hays, David[38] C. Marquis and Samuel J. Niccolls, all of whom have been Moderators of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church. In the law, S. C. T. Dodd, for many years the principal solicitor of the Standard Oil Company, stands out most conspicuously. Three of our number have served for longer or shorter periods as college presidents. Of Doctors of Divinity we have a long list, and also a goodly number of Doctors of Law; and others, though they have received less recognition for their work, have in our judgment escaped only because the world does not always know the worth of quiet lives. To spend years in the associations of such a class in college is itself an efficient means of education. It is a high tribute to the ability and the diligence of Mateer that, although he was with us only two years, he divided the first honor. The sharer with him in this distinction was the youngest member of the class, but a man who, in addition to unusual capacity, also had enjoyed the best preparation for college then available. On the part of Mateer, it was not what is known as genius that won the honor; it was a combination of solid intellectual capacity, with hard, constant work. The faculty assigned him the valedictory, the highest distinction at graduation, but on his own solicitation, this was given to the other first honor man.

In a letter sent by him from Wei Hsien, China, September 4, 1907, in answer to a message addressed to him by the little remnant of his classmates who assembled at Canonsburg a couple of months earlier,[39] to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of their graduation, he said:

It was with very peculiar feelings of pleasure mingled with sadness that I read what was done by you at your meeting. The distance that separated me from you all adds a peculiar emphasis to my feelings, suggestive of loneliness. I have never been homesick in China. I would not be elsewhere than where I am, nor doing any other work than what I am doing. Yet when I read over the account of that meeting in Canonsburg my feelings were such as I have rarely had before. Separated by half the circumference of the globe for full forty-four years, yet in the retrospect the friendship formed in these years of fellowship in study seems to grow fresher and stronger as our numbers grow less. A busy life gives little time for retrospection, yet I often think of college days and college friends. Very few things in my early life have preserved their impression so well. I can still repeat the roll of our class, and I remember well how we sat in that old recitation room of Professor Jones [physics and chemistry]. I am in the second half of my seventy-second year, strong and well. China has agreed with me. I have spent my life itinerating, teaching and translating, with chief strength on teaching. But with us all who are left, the meridian of life is past, and the evening draws on. Yet a few of us have still some work to do. Let us strive to do it well, and add what we can to the aggregate achievement of the class’s life work—a record of which I trust none of us may be ashamed.

In the unanticipated privilege of writing this book I am trying to fulfill that wish of our revered classmate.

“From my youth I had the missionary work before me as a dim vision. A half-formed resolution was all the while in my mind, though I spoke of it to no one. But for this it is questionable whether I would have given up teaching to go to the Seminary. After long consideration and many prayers I offered myself to the Board, and was accepted.”—AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH for college class anniversary, 1897.

In the four sentences at the head of this chapter we have a condensed outline of the process by which Calvin Mateer came to be a foreign missionary. In his case it did not, as in the antecedent experience of most other clergymen who have given themselves to this work, start with an attraction first toward the ministry, and then toward the missionary service; but just the reverse. In order to understand this we need to go back again to “the old home,” and especially to his mother. We are fortunate here in having the veil of the past lifted by Mrs. Kirkwood, as one outside of the family could not do, or, even if he could, would hesitate to do.

Long before her marriage, when indeed but a young girl, Mary Nelson Diven [Calvin’s mother] heard an appeal for the Sandwich Islands made by the elder Dr. Forbes, one of the early missionaries of the American Board, to those islands. He asked for a box of supplies. There was not much missionary[41] interest in the little church of Dillsburg, York County, Pennsylvania, of which she was a member; for the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions had not been organized, and the American Board had not attained its majority. Her pastor sympathized with the newly awakened zeal and interest of his young parishioner, when she proposed to canvass the congregation in response to Dr. Forbes’s appeal. The box was secured and sent. This was the seed that germinated in her heart so early and bore fruit through the whole of her long life.

When in her nineteenth year she was married to John Mateer, hers was a marriage in the Lord; and together she and her husband consecrated their children in their infancy to his service. This consecration was not a form; they were laid upon the altar and never taken back. Through all the self-denying struggles to secure their education, one aim was steadily kept in view, that of fitting them either to carry the gospel to some heathen land, or to do the Lord’s work in their own land.

In addition to the foreign missionary periodicals, a number of biographies of foreign missionaries were secured and were read by all the family. Not only did this mother try to awaken in her children an interest in missions through missionary literature, but she devised means to strengthen and make permanent this interest, to furnish channels through which these feelings and impulses might flow toward practical results. One of these was a missionary mite box which she fashioned with her own hands, away back in the early forties, before the mite boxes had been scattered broadcast in the land. Quaint indeed it was, this plain little wooden box, covered with small-figured wall paper. Placed upon the[42] parlor mantel, it soon became the shrine of the children’s devotion. No labor or self-denial on their part was considered too great to secure pennies for “the missionary box.” Few pennies were spent for self-indulgence after that box was put in place, and overflowing was the delight when some unwonted good fortune made it possible to drop in silver coins—“six-and-a-fourth bits,” or “eleven-penny bits.” Most of the offerings were secured by such self-denials as foregoing coffee, sugar, or butter. There was not at that time much opportunity for country children to earn even pennies. The “red-letter” day of all the year was when the box was opened and the pennies were counted.

This earnest-hearted mother had counted the cost of what she was doing in thus educating her children into the missionary spirit. When her first-born turned his face toward the heathen world, there was no drawing back—freely she gave him to the work. As one after another of her children offered themselves to the Foreign Board, she rejoiced in the honor God had put upon her, never shrinking from the heart strain the separation from her children must bring. She only made them more special objects of prayer, thus transmuting her personal care-taking to faith. She lived to see four of her children in China.

This explains how it came about that this elder son, from youth, had before him the missionary work as “a dim vision,” and that “a half-formed resolution” to take it up was all the while in his mind.

When he graduated from college, he had made no decision as to his life work. During the years preceding he at no time put aside the claims of missions,[43] and consequently of the ministry, upon him, and in various ways he showed his interest in that line of Christian service. As he saw the situation the choice seemed mainly to lie between this on the one hand, and teaching on the other. Before he graduated he had the offer of a place in the corps of instructors for the Lawrenceville (New Jersey) school, since grown into such magnitude and esteem as a boys’ preparatory institution; but the conditions were not such that he felt justified in accepting. Unfortunately, there is a blank in his Journal for the period between March 4, 1857, some six months before he received his diploma at Jefferson, and October 24, 1859, when he had already been a good while in the theological seminary; and to supply it scarcely any of his letters are available. In the autobiographical sketch already noticed he says:

From college I went to take charge of the academy at Beaver, Pennsylvania. I found it run down almost to nothing, so that the first term (half year) it hardly paid me my board. I was on my mettle, however, and determined not to fail. I taught and lectured and advertised, making friends as fast as I could. I found the school with about twenty boys, all day scholars; I left it at the end of the third term with ninety, of whom thirty were boarders. I could easily have gone on and made money, but I felt that I was called to preach the gospel, and so, I sold out my school and went to Allegheny [Western Theological Seminary], entering when the first year was half over.

One of his pupils at Beaver was J. R. Miller, D.D., a distinguished minister of the gospel in Philadelphia; and very widely known especially as the author of solid but popular religious books. Writing of his experience at the Beaver Academy, he says:

When I first entered, the principal was Mr. Mateer. The first night I was there, my room was not ready, and I slept with him in his room. I can never forget the words of encouragement and cheer he spoke that night, to a homesick boy, away for almost the first time from his father and mother.... My contact with him came just at the time when my whole life was in such plastic form that influence of whatever character became permanent. He was an excellent teacher. His personal influence over me was very great. I suppose that when the records are all known, it will be seen that no other man did so much for the shaping of my life as he did.

While at Beaver he at last decided that he was called of God to study for the ministry, but called not by any extraordinary external sign or inward experience. It was a sense of duty that determined him, and although he obeyed willingly, yet it was not without a struggle. He had a consciousness of ability to succeed as a teacher or in other vocations; and he was by no means without ambition to make his mark in the world. Because he was convinced by long and careful and prayerful consideration that he ought to become a minister he put aside all the other pursuits that might have opened to him. Not long after he entered the seminary he wrote to his mother:[45] “You truly characterize the work for which I am now preparing as a great and glorious one. I have long looked forward to it, though scarcely daring to think it my duty to engage in it. After much pondering in my own mind, and prayer for direction I have thought it my duty to preach.”

On account of teaching, as already related, he did not enter the theological seminary until more than a year after I did, so that I was not his classmate there. He came some months late in the school year, and had at first much back work to make up; but he soon showed that he ranked among the very best students. His classmate, Rev. John H. Sherrard, of Pittsburg, writes:

One thing I do well remember about Mateer: his mental superiority impressed everyone, as also his deep spirituality. In some respects, indeed most, he stood head and shoulders above his fellows around him.

Another classmate, Rev. Dr. William Gaston, of Cleveland, says:

We regarded him as one of our most level-headed men; our peer in all points; not good merely in one point, but most thorough in all branches of study. He was cheerful and yet not flippant, and with a tinge of the most serious. He was optimistic, dwelling much on God’s great love.... He was not only a year in advance of most of us in graduating from college, but I think that we, as students, felt that though we were classmates in the seminary, he was in advance of us in other things. Life seemed[46] more serious to him. I doubt if any one of us felt the responsibility of life as much as he did. I doubt if anyone worked as hard as he.

The Western Theological Seminary, during the period of Mateer’s attendance, was at the high-water mark of prosperity. The general catalogue shows an enrollment of sixty-one men in his class; the total in all classes hovered about one hundred and fifty. In the faculty there were only four members, and, estimated by the specializations common in our theological schools to-day, they could not adequately do all their work; and this was the more true of them, because all save one of them eked out his scanty salary by taking charge of a city church. But they did better than might now be thought possible; and especially was this practicable because of the limited curriculum then prescribed, and followed by all students. Dr. David Elliott was still at work, though beyond the age when he was at his best. Samuel J. Wilson was just starting in his brilliant though brief career, and commanded a peculiar attachment from his pupils. Dr. Jacobus was widely known and appreciated for his popular commentaries. However, the member of the faculty who left the deepest impress on Mateer was Dr. William S. Plumer. Nor in this was his case exceptional. We all knew that Dr. Plumer was not in the very first rank of theologians. We often missed in his lectures the marks of very broad and deep scholarship. But as a teacher he nevertheless made upon[47] our minds an impression that was so great and lasting that in all our subsequent lives we have continued to rejoice in having been under his training. Best of all was his general influence on the students. We doubt whether in the theological seminaries of the Presbyterian Church of the United States it has ever been equaled, except by Archibald Alexander of Princeton. The dominant element of that influence was a magnificent personality saturated with the warmest and most tender piety, having its source in love for the living, personal Saviour. For Dr. Plumer, Mateer had then a very high degree of reverent affection, and he never lost it.

Spiritually, the condition of the seminary while Mateer was there was away above the ordinary. In the winter of 1857-58 a great revival had swept over the United States, and across the Atlantic. In no place was it more in evidence than in the theological schools; it quickened immensely the spiritual life of the majority of the students. One of its fruits there was the awakening of a far more intense interest in foreign missions. I can still recall the satisfaction which some of us who in the seminary were turning our faces toward the unevangelized nations had in the information that this strong man who stood in the very first rank as to character and scholarship had decided to offer himself to the Board of Foreign Missions for such service as they might select for him. It was a fitting consummation of his college and seminary life.

Yet it was only slowly, even in the seminary, and after much searching of his own heart and much wrestling in prayer, that he came to this decision. Outside of himself there was a good deal that tended to impel him toward it. The faculty, and especially Dr. Plumer, did all they could wisely to press on the students the call of the unevangelized nations for the gospel. Representatives of this cause—missionaries and secretaries—visited the seminary, where there were, at that time, more than an ordinary number of young men who had caught the missionary spirit. In college, Mateer, without seeking to isolate himself from others, had come into real intimacy with scarcely any of his fellow-students. He says in the autobiographical sketch, “I minded my own business, making comparatively few friends outside of my own class, largely because I was too bashful to push my way.” In the seminary he, while still rather reserved, came nearer to some of his fellow-theologues; and especially to one, Dwight B. Hervey, who shared with him the struggle over duty as to a field of service. They seem to have been much in conference on that subject.

On the 21st of January, 1860, he presented himself before the Presbytery of Ohio, to which the churches of Pittsburg belonged, passed examination in his college studies, and was received under the care of that body; but he had not then made up his mind to be a missionary. On the 12th of April of the same year he went before the Presbytery of Butler, at[49] Butler, Pennsylvania (having at his own request been transferred to the care of that organization, because his parents’ home was now within its bounds), and was licensed to preach. Yet still he had not decided to be a missionary. He was powerfully drawn toward that work, and vacillation at no time in his life was a characteristic; there simply was as yet no need that he should finally make up his mind, and he wished to avoid any premature committal of himself, which later he might regret, or which he might feel bound to recall.

The summer of 1860 he spent in preaching here and there about Pittsburg, several months being given to the Plains and Fairmount churches; followed by a visit home, and another in Illinois.

When the seminary opened in the autumn, he was back in his place. One of the duties which fell to him was to preach a missionary sermon before the Society of Inquiry. He did this so well that the students by vote expressed a desire that the sermon should be published. In his Journal he notes that the preparation of this discourse “strengthened his determination to give himself to this work.” Before the Christmas recess Dr. J. Leighton Wilson, one of the secretaries of the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions, visited the seminary, and in conference did much to stimulate the missionary spirit. He found in Mateer an eager and responsive listener. On the 12th of December Mateer wrote a long letter to his mother, in which he expresses feeling, because without warrant[50] some one had told her that he had offered himself to the Foreign Board. He says, “I am not going to take such an important step without informing you of it directly and explicitly.” Then he proceeds to tell her just what was his attitude at that time:

I have thought of the missionary work this long time, but not very seriously until within the last couple of years. Ever since I came to the seminary I have had a conviction to some degree that I ought to go as a missionary. That conviction has been constantly growing and deepening, and more especially of late. I have about concluded that so far as I am myself concerned it is my duty to be a missionary. I have thought a great deal on this subject and I think that I have not come to such a conclusion hastily. It has cost me very considerable effort to give up the prospects which I might have had at home. The matter in almost every view you can take of it involves trial and self-denial. I need great grace,—for this I pray. But even if I have prospects of usefulness at home, surely nothing can be lost in this respect by doing what I am convinced is my duty. Indeed, one of the encouraging features, in fact the great encouragement, is a prospect of more extended usefulness than at home. This may seem not to be so at the first view, but a more careful consideration of all the aspects of the case will, I think, bring a different conclusion.

The letter is very full, and lays bare his whole mind and heart as he would be willing to do only to his mother. It is a revelation of this strong, self-reliant, mature but filial-spirited and tenderly thoughtful[51] young Christian man and prospective minister, to a mother whom he recognized as deserving an affectionate consideration such as he owed to no other created being.

On the 7th of January, 1861, he received a letter from his mother, in which she gave her consent that he should be a foreign missionary, naming only one or two conditions which involved no insuperable difficulty. In a student prayer meeting about three weeks later he took occasion in some remarks to tell them that he had decided to offer himself for this work. Still, it was not until the 5th of April, and when within two weeks of graduation, that he, in a full and formal letter, such as is expected and is appropriate, offered himself to the Board. In his Journal of that date, after recording the character of his letter, he says: “This is a solemn and important step which I have now taken. During this week, while writing this letter, I have, I trust, looked again at the whole matter, and asked help and guidance from God. I fully believe it is my duty to go. My greatest fear has been that I was not as willing to go as I should be, but I cast myself on Christ and go forward.” On the 13th of April he received word from the Board that he had been accepted, the time of his going out and his field of labor being yet undetermined.

So the problem of his life work was at length solved, as surely as it could be by human agency. It had been his mother’s wish that he should wait a year before going to his field, and to this he had no serious objection; but as matters turned out, more than two[52] years elapsed before he was able to leave this country. This long delay was caused by the outbreak of the Civil War, and the financial stringency which made it impossible for the Foreign Board to assume any additional obligations. Much of the time the outlook was so dark that he almost abandoned hope of entering on his chosen work, though the thought of this filled his heart with grief. He was intensely loyal to the cause of the Union, and if he had not been a licentiate for the ministry he almost certainly would have enlisted in the army. He records his determination to go if drafted. Once, indeed, during this period of waiting he was a sort of candidate for a chaplaincy to a regiment, which fortunately he did not secure. For several months he preached here and there in the churches of the general region about Pittsburg, and also made a visit to towns in central Ohio, one of these being Delaware, the seat of the Ohio Wesleyan University. Not long afterward he received an urgent request from the Old School Presbyterian Church in that town to come and supply them. About the same time the churches of Fairmount and Plains in Pennsylvania gave him a formal call to become their pastor, but this he declined. He accepted the invitation to Delaware, I suppose partly because it left him free still to go as a missionary whenever the way might open. At Delaware he remained eighteen months, until at last, in the good providence of God, he was ordered “to the front” out in China.

The story of his service of the church in that place need not be told here except in brief. It must, however, be clearly stated that it was in the highest degree creditable to him. In fact, the conditions were such that one may see in it a providential training in the courage and patience and faithfulness which in later years he needed to exercise on the mission field. The church was weak, and was overshadowed somewhat even among the Presbyterian element by a larger and less handicapped New School organization; and was sorely distressed by internal troubles. For a while after Mateer came, it was a question whether it could be resuscitated from its apparently dying stale. At the end of his period of service it was once more alive, comparatively united, and anxious to have him remain as pastor.

On November 12, 1862, while in charge of the church at Delaware, he was ordained to the full work of the ministry, as an evangelist, by the Presbytery of Marion, in session at Delaware.

On December 27, 1862, he was married in Delaware, at the home of her uncle, to Miss Julia A. Brown, of Mt. Gilead, Ohio. Two years before they were already sufficiently well acquainted to interchange friendly letters; later their friendship ripened into mutual love; and now, after an eight months’ engagement, they were united for life. Mateer says in his Journal, “The wedding was very small and quiet; though it was not wanting in merriment,” and naïvely adds, “Found marrying not half so hard as[54] proposing.” Julia, as he ever afterward calls her, was a superbly good wife for him. In her own home, in the schoolroom, in the oversight of the Chinese boys and girls who were their pupils, in the preparation of her “Music Book,” in her labors for the evangelization of the women, in her journeyings,—hindered as she was most of the time by broken health,—she effectively toiled on, until at last, after thirty-five years of missionary service, her husband laid away all of her that was mortal in the little cemetery east of the city of Tengchow, by the side of her sister, Maggie (Mrs. Capp), who had died in the same service, and of other missionary friends who had gone on before her.

When they were married they were still left in great uncertainty as to the time when the Board could send them out, or, indeed, whether the Board could send them out at all. They went on their bridal trip to his parents’ home in western Pennsylvania, reaching there on Wednesday, December 31. Just a week afterward he received a letter from the Board announcing their readiness to send them to China. The record of his Journal deserves to be given here in full.

Scarcely anything in my life ever came so unexpectedly. A peal of thunder in the clear winter sky would not have surprised us more. The letter was handed me in the morning when I came downstairs at grandfather’s. After reading it, I took it upstairs and read it to “my Jewel.” In less than three minutes I think our minds were made up. Her first exclamation[55] after hearing the letter I shall not forget: “Oh, I am glad!” That was the right ring for a missionary: no long-drawn, sorrowful sigh, but the straight-out, noble, self-sacrificing, “Oh, I am glad!” I shall remember that time, that look, that expression. If I did not say, I felt, the same. I think I can truly say I was and am glad. My lifelong aspiration is yet to be realized. I shall yet spend my life and lay my bones in a heathen land. I had fully made up my mind to labor in this country, and most likely for some time in Delaware; but how suddenly everything is changed! The only regret I feel is that I am not five years younger. What a great advantage it would give me in acquiring the language! But so it is, and Providence made it so. I had despaired of going, and despairing I was greatly perplexed to understand the leadings of Providence in directing my mind so strongly to the work, and bringing me so near to the point of going before. Now I understand the matter better. Now I see that my strong persuasion that I would yet go was right. God did not deceive me. He only led me by a way that I knew not. Just when the darkness seemed to be greatest, then the sun shone suddenly out. How strange it all seems! The way was all closed; no funds to send out men to China; and I could not go. Suddenly two missionaries die, and the health of another fails; and the Board feels constrained to send out one man at least, to supply their place; and so the door opens to me. And I will enter it, for Providence has surely opened it. As I have given myself to this work, and hold myself in readiness to go, I will not retrace my steps now. Having put my hand to the plow, I will not look back. I do not wish to. It is true, however, that preaching a year and a half has bound strong[56] cords around me to keep me here. I cannot go so easily now as I might have done when I first left the seminary. It will be a sore trial to tear myself away from the folks at Delaware. They will try hard, I know, to retain me; but I think my mind is set, and I must go. I must go; I am glad to go; I will go. The Lord will provide for Delaware. I commit the work there to his hands. I trust and believe that he will carry it on, and that it will yet appear that my labor there has not been in vain. Yesterday I was twenty-seven years old. I hope to chronicle my next birthday in China. The Lord has spared me twenty-seven years in my native land. Will he give me as many in China! Grant it, O Lord, and strengthen me mightily to spend them all for thee!

This strong, persistent, conscientious, self-controlled, consecrated man had found his life work at last.

“If there had been no other way to get back to America, than through such another experience, it is doubtful whether I should ever have seen my native land again.”—AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH, 1897.

The choice of the country to which he should go as a missionary had been with him a subject of earnest consideration and prayer. He says in his Journal, under date of September 12, 1862:

The Board wished me to go to Canton, China, at first. This was altogether against my inclinations and previous plans; but the Board would not send me anywhere else, until in the last letter they offered to send me to Japan; I have long had thoughts of northern India or of Africa; and especially have I wished to go to some new mission where the ground is unoccupied, and where I would not be entrammeled by rules and rigid instructions. The languages of eastern Asia are also exceedingly difficult and the missionary work is peculiarly discouraging among that people.

Two days later, however, he sent the Board a letter saying that he would go to Japan. When his field finally was specifically designated, it was north China. He was to be stationed at Tengchow, a port[58] that had been opened to foreign commerce in the province of Shantung.

The Mateers remained at Delaware until late in April. Until that time he continued in charge of his church. In a touching farewell service they took leave of their people, and traveled by slow stages toward New York.

Going to live in China was then so much more serious a matter than it is now that we can scarcely appreciate the leave-takings that fell to the lot of these two young missionaries. The hardest trial of all was to say good-by to mother and to father, and to brothers and sisters, some of whom were yet small children, and for whom he felt that he might do so much if not separated from them by half the distance round the world.

At length on July 3, 1863, they embarked at New York on the ship that was to carry them far to the south of the Cape of Good Hope, then eastward almost in sight of the northern shores of Australia, and finally, by the long outside route, up north again to Shanghai. They were one hundred and sixty-five days, or only about two weeks short of half a year, in making the voyage. During that long period they never touched land. It needs to be borne in mind that in 1863 the Suez Canal had only been begun; that the railroads across our continent had not been built; and that no lines of passenger steamers were running from our western coast over to Asia. No blame, therefore, is chargeable to the Board of Missions for[59] sending out their appointees on a sailing vessel. The ship selected was a merchantman, though not a clipper built for quick transit, was of moderate size, in sound condition, and capable of traveling at fairly good speed. Accompanying the Mateers were Hunter Corbett and his wife, who also had been appointed by the Board, for Tengchow. There were six other passengers, none of whom were missionaries, and, besides the officers, there was a crew of sixteen men.

At best the voyage could not be otherwise than tedious and trying. The accommodations for passengers were necessarily scant, the staterooms, being mere closets with poor ventilation, and this cut off in rough weather. The only place available for exercise was the poop deck, about thirty feet long; thus walking involved so much turning as greatly to lessen the pleasure, and many forms of amusement common on larger vessels were entirely shut out. Food on such a long voyage had to be limited in variety, and must become more or less stale. Of course, it was hot in the tropics, and it was cold away south of the equator, and again up north in November and December. Seasickness is a malady from which exemption could not be expected. When a company of passengers and officers with so little in common as to character and aims were cooped together, for so long a time, in narrow quarters, where they must constantly come into close contact, a serious lack of congeniality and some friction might be expected to develop among them.