Title: Old English colour prints

Author: Malcolm C. Salaman

Editor: Charles Holme

Release date: October 1, 2023 [eBook #71768]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Offices of 'The Studio', 1909

Credits: Fiona Holmes, Fay Dunn and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive.

Page 30—Chilaren changed to Children

It is noted that some of the plates are only showing part fractions - these have been left as printed.

[i]

TEXT BY

MALCOLM C. SALAMAN

(AUTHOR OF ‘THE OLD ENGRAVERS OF ENGLAND’)

EDITED BY

CHARLES HOLME

MCMIX

OFFICES OF ‘THE STUDIO’

LONDON, PARIS AND NEW YORK

| PREFATORY NOTE. |

| LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. |

| OLD ENGLISH COLOUR-PRINTS. |

| II. |

| III. |

| NOTES ON THE ILLUSTRATIONS. |

The Editor desires to express his thanks to the following Collectors who have kindly lent their prints for reproduction in this volume:—Mrs. Julia Frankau, Mr. Frederick Behrens, Major E. F. Coates, M.P., Mr. Basil Dighton, Mr. J. H. Edwards, and Sir Spencer Ponsonby-Fane, P.C., G.C.B. Also to Mr. Malcolm C. Salaman, who, in addition to contributing the letterpress, has rendered valuable assistance in the preparation of the work.

[iv]

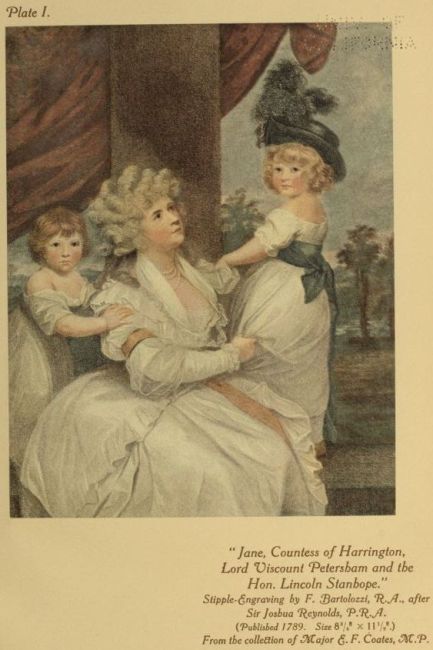

| Plate | I. | “Jane, Countess of Harrington, Lord Viscount Petersham and the Hon. Lincoln Stanhope.” Stipple-Engraving by F. Bartolozzi, R.A., after Sir Joshua Reynolds, P.R.A. |

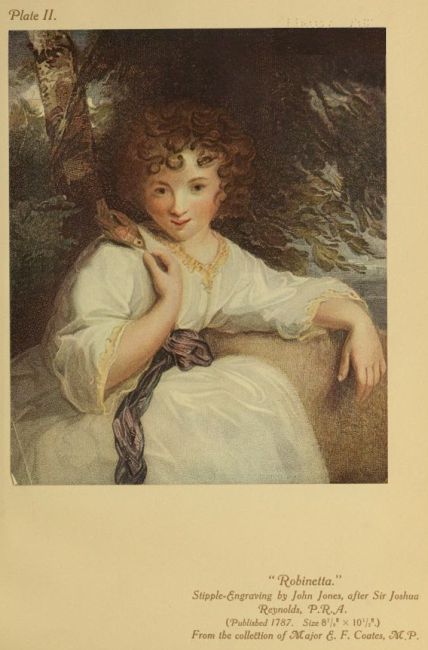

| ” | II. | “Robinetta.” Stipple-Engraving by John Jones, after Sir Joshua Reynolds, P.R.A. |

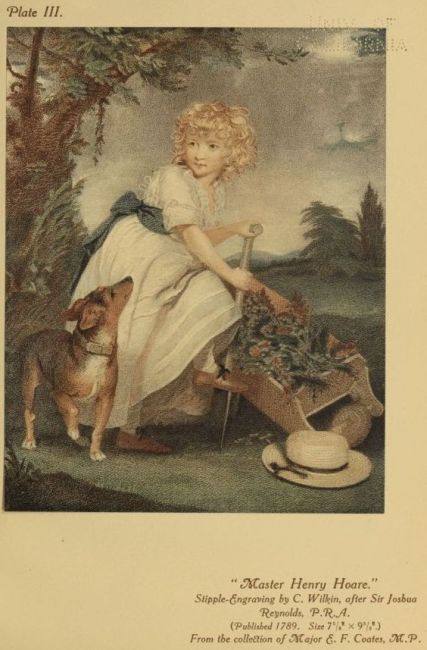

| ” | III. | “Master Henry Hoare.” Stipple-Engraving by C. Wilkin, after Sir Joshua Reynolds, P.R.A. |

| ” | IV. | “The Duchess of Devonshire and Lady Georgiana Cavendish.” Mezzotint-Engraving by Geo. Keating, after Sir Joshua Reynolds, P.R.A. |

| ” | V. | “The Mask.” Stipple-Engraving by L. Schiavonetti, after Sir Joshua Reynolds, P.R.A. |

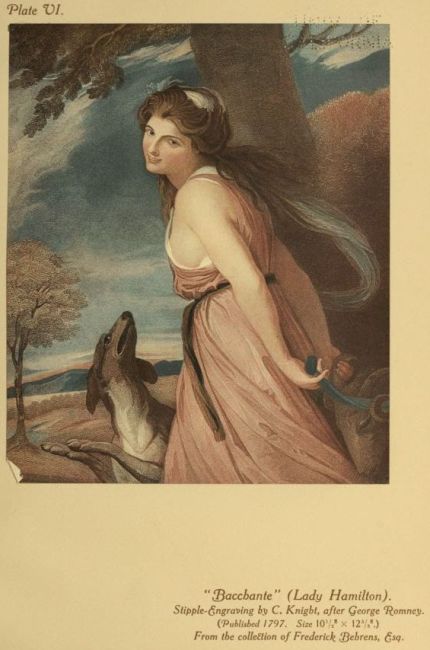

| ” | VI. | “Bacchante” (Lady Hamilton). Stipple-Engraving by C. Knight, after George Romney. |

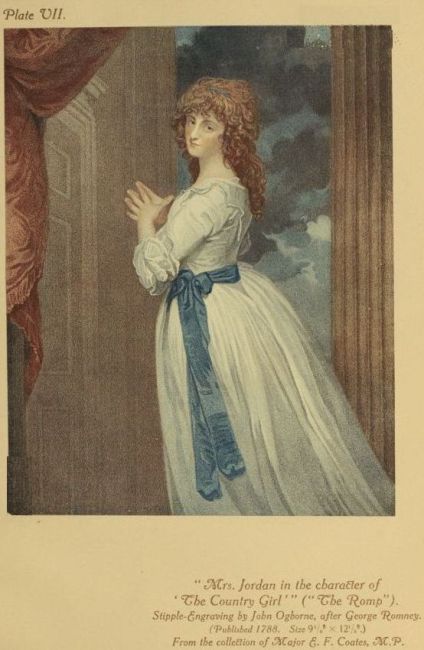

| ” | VII. | “Mrs. Jordan in the character of ‘The Country Girl’” (“The Romp”). Stipple-Engraving by John Ogborne, after George Romney. |

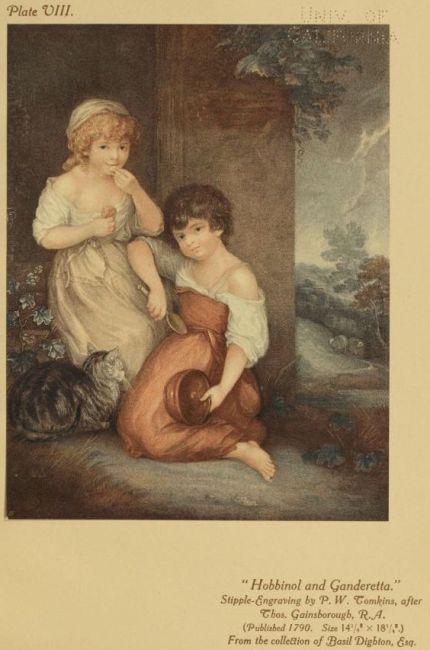

| ” | VIII. | “Hobbinol and Ganderetta.” Stipple-Engraving by P. W. Tomkins, after Thomas Gainsborough, R.A. |

| ” | IX. | “Countess of Oxford.” Mezzotint-Engraving by S. W. Reynolds, after J. Hoppner, R.A. |

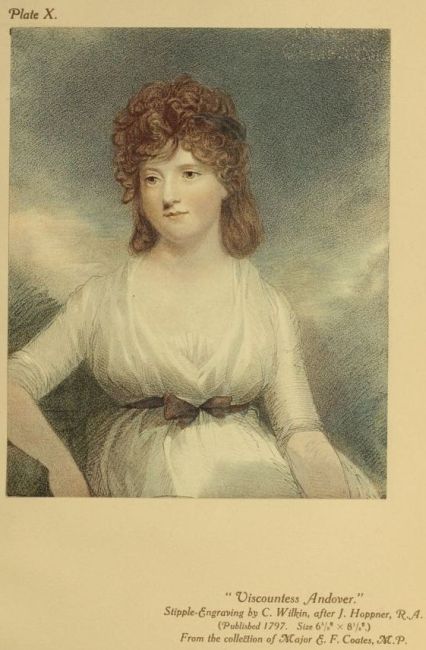

| ” | X. | “Viscountess Andover.” Stipple-Engraving by C. Wilkin, after J. Hoppner, R.A. |

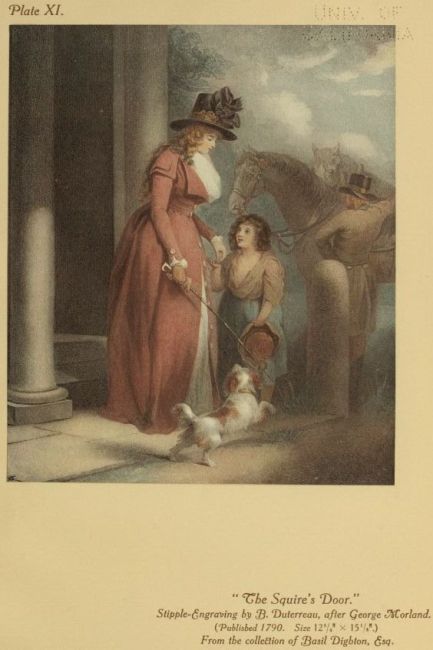

| ” | XI. | “The Squire’s Door.” Stipple-Engraving by B. Duterreau, after George Morland. |

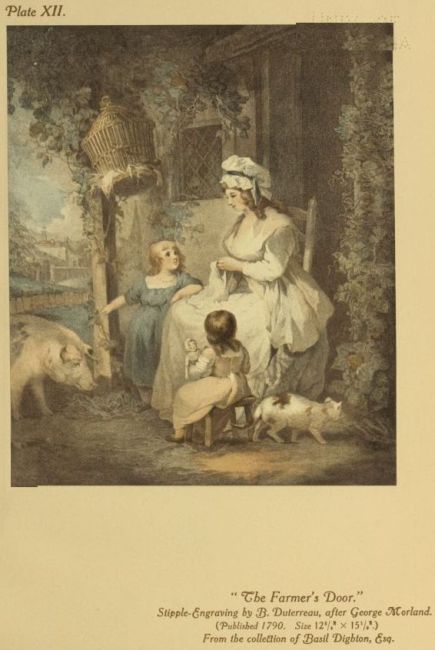

| ” | XII. | “The Farmer’s Door.” Stipple-Engraving by B. Duterreau, after George Morland. |

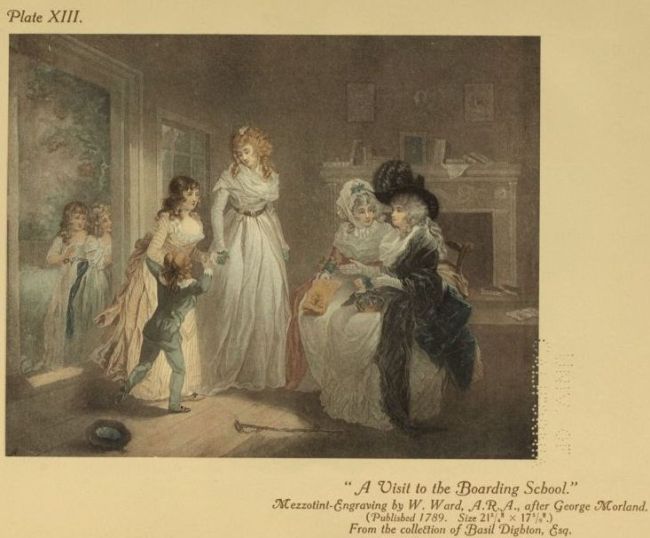

| ” | XIII. | “A Visit to the Boarding School.” Mezzotint-Engraving by W. Ward, A.R.A., after George Morland. |

| ” | XIV. | “St. James’s Park.” Stipple-Engraving by F. D. Soiron, after George Morland. |

| ”[v] | XV. | “A Tea Garden.” Stipple-Engraving by F. D. Soiron, after George Morland. |

| ” | XVI. | “The Lass of Livingstone.” Stipple-Engraving by T. Gaugain, after George Morland. |

| ” | XVII. | “Rustic Employment.” Stipple-Engraving by J. R. Smith, after George Morland. |

| ” | XVIII. | “The Soliloquy.” Stipple-Engraving by and after William Ward, A.R.A. |

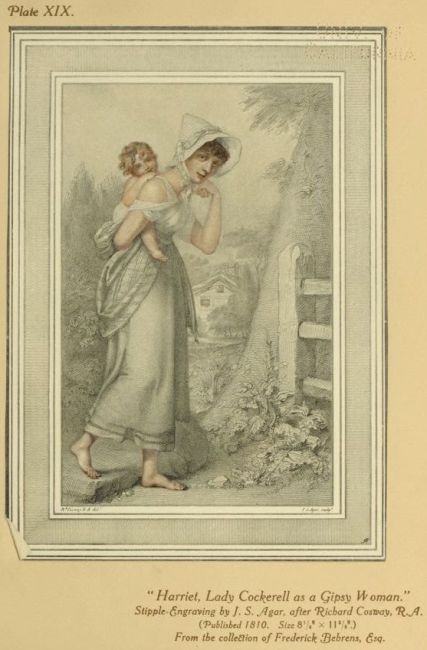

| ” | XIX. | “Harriet, Lady Cockerell as a Gipsy Woman.” Stipple-Engraving by J. S. Agar, after Richard Cosway, R.A. |

| ” | XX. | “Lady Duncannon.” Stipple-Engraving by F. Bartolozzi, R.A., after John Downman, A.R.A. |

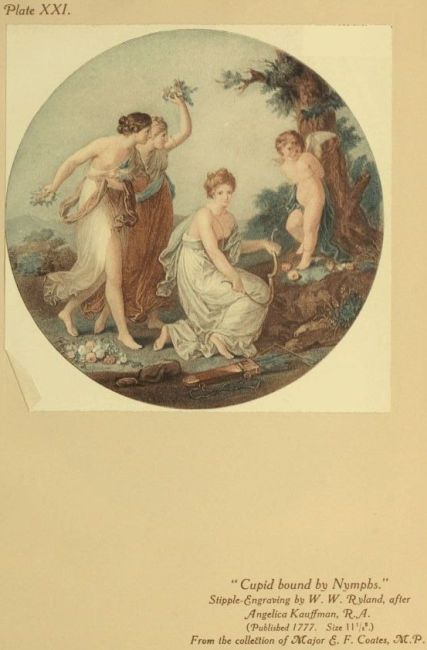

| ” | XXI. | “Cupid bound by Nymphs.” Stipple-Engraving by W. W. Ryland, after Angelica Kauffman, R.A. |

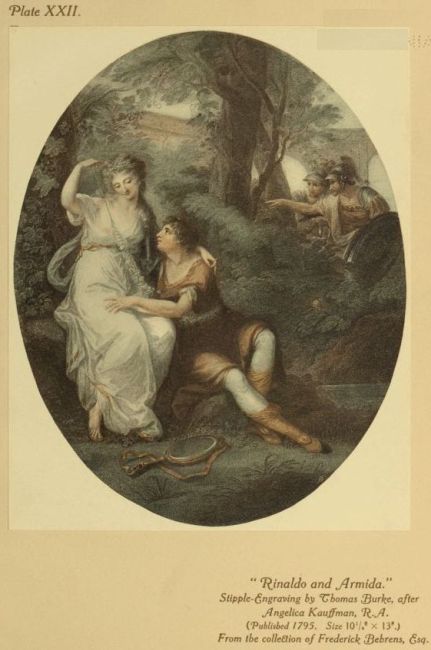

| ” | XXII. | “Rinaldo and Armida.” Stipple-Engraving by Thos. Burke, after Angelica Kauffman, R.A. |

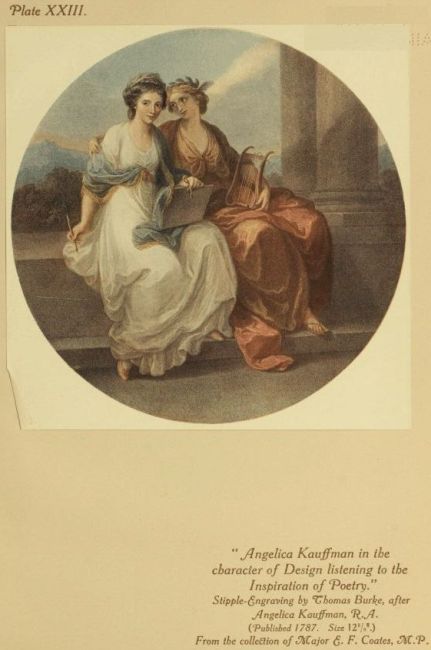

| ” | XXIII. | “Angelica Kauffman in the character of Design listening to the Inspiration of Poetry.” Stipple-Engraving by Thos. Burke, after Angelica Kauffman, R.A. |

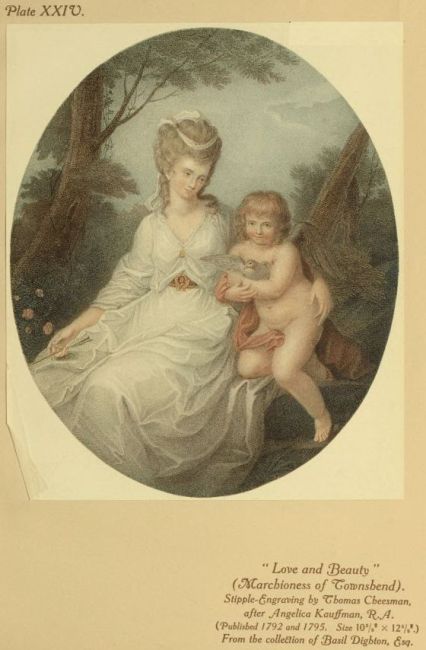

| ” | XXIV. | “Love and Beauty” (Marchioness of Townshend). Stipple-Engraving by Thos. Cheesman, after Angelica Kauffman, R.A. |

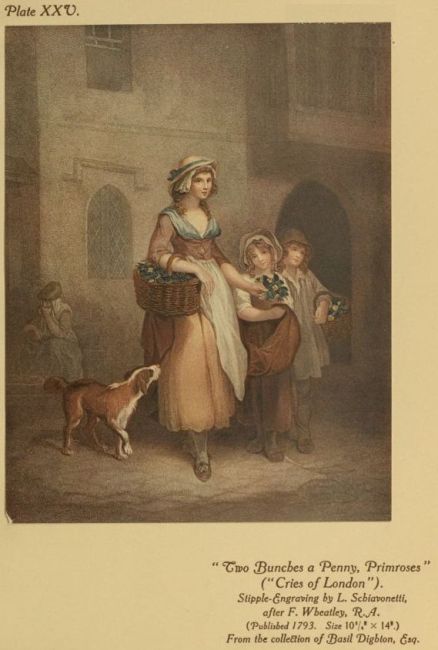

| ” | XXV. | “Two Bunches a Penny, Primroses” (“Cries of London”). Stipple-Engraving by L. Schiavonetti, after F. Wheatley, R.A. |

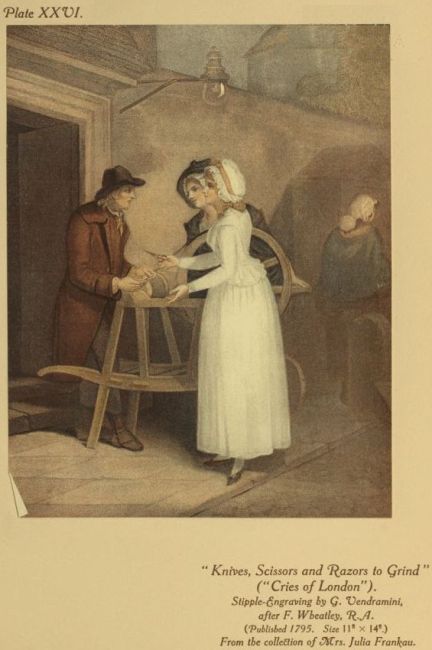

| ” | XXVI. | “Knives, Scissors and Razors to Grind” (“Cries of London”). Stipple-Engraving by G. Vendramini, after F. Wheatley, R.A. |

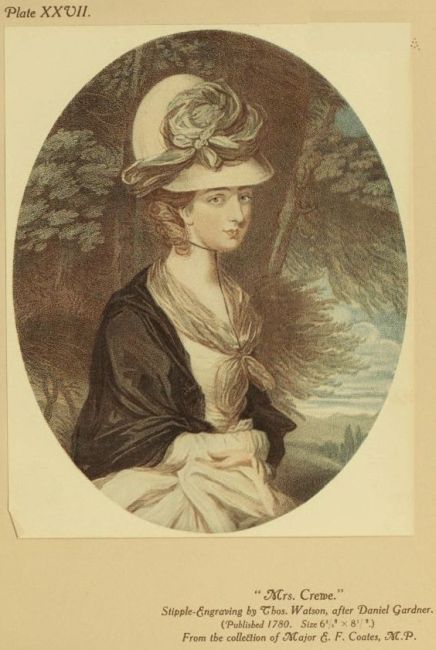

| ” | XXVII. | “Mrs. Crewe.” Stipple-Engraving by Thos. Watson, after Daniel Gardner. |

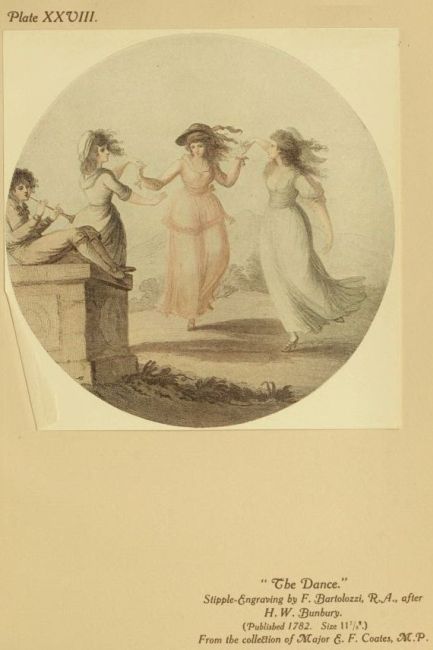

| ” | XXVIII. | “The Dance.” Stipple-Engraving by F. Bartolozzi, R.A., after H. W. Bunbury. |

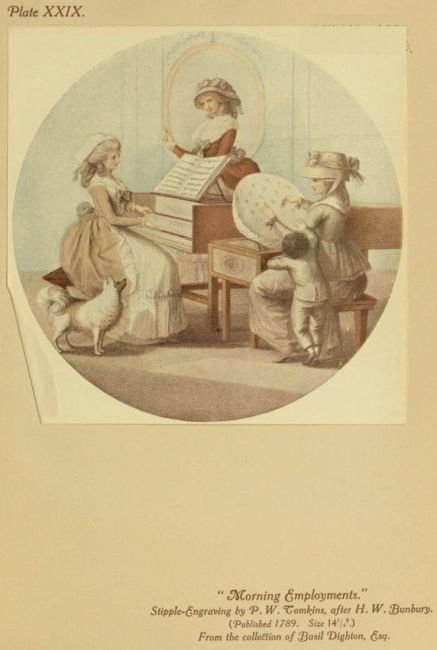

| ”[vi] | XXIX. | “Morning Employments.” Stipple-Engraving by P. W. Tomkins, after H. W. Bunbury. |

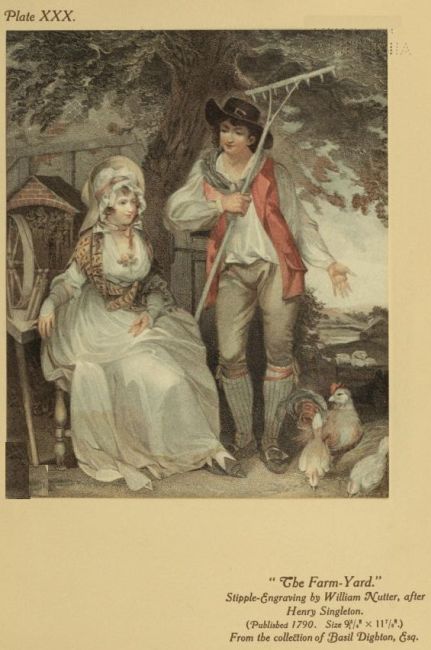

| ” | XXX. | “The Farm-Yard.” Stipple-Engraving by William Nutter, after Henry Singleton. |

| ” | XXXI. | “The Vicar of the Parish receiving his Tithes.” Stipple-Engraving by Thos. Burke, after Henry Singleton. |

| ” | XXXII. | “The English Dressing-Room.” Stipple-Engraving by P. W. Tomkins, after Chas. Ansell. |

| ” | XXXIII. | “The French Dressing-Room.” Stipple-Engraving by P. W. Tomkins, after Chas. Ansell. |

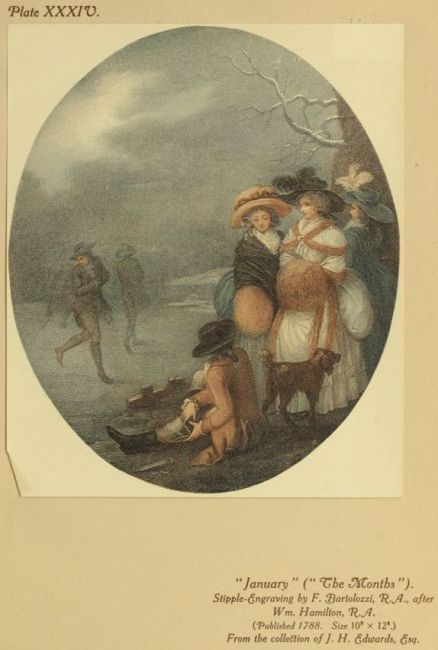

| ” | XXXIV. | “January” (“The Months”). Stipple-Engraving by F. Bartolozzi, R.A., after Wm. Hamilton, R.A. |

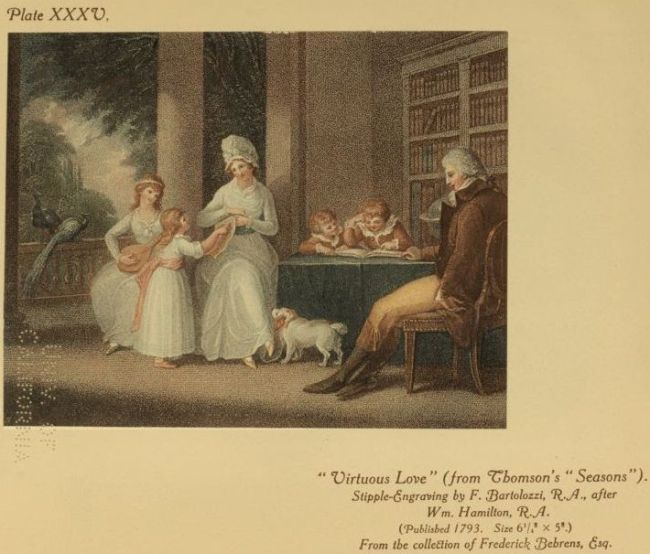

| ” | XXXV. | “Virtuous Love” (from Thomson’s “Seasons”). Stipple-Engraving by F. Bartolozzi, R.A., after Wm. Hamilton, R.A. |

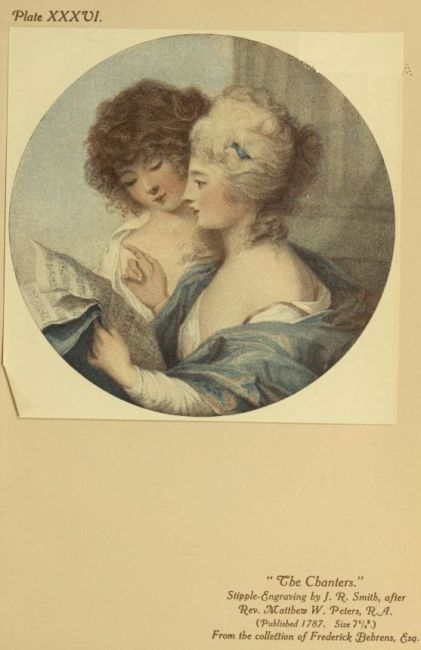

| ” | XXXVI. | “The Chanters.” Stipple-Engraving by J. R. Smith, after Rev. Matthew W. Peters, R.A. |

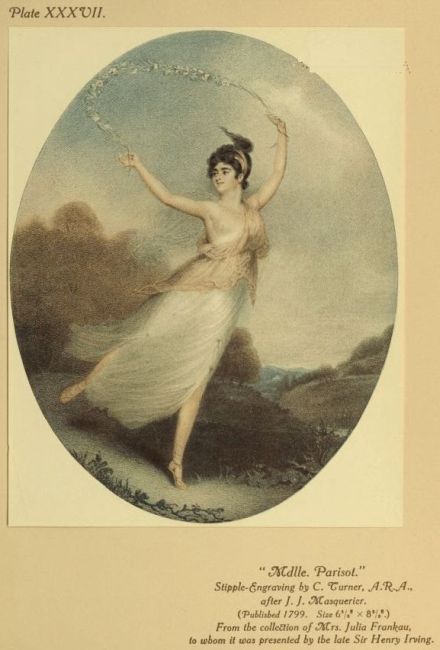

| ” | XXXVII. | “Mdlle. Parisot.” Stipple-Engraving by C. Turner, A.R.A., after J. J. Masquerier. |

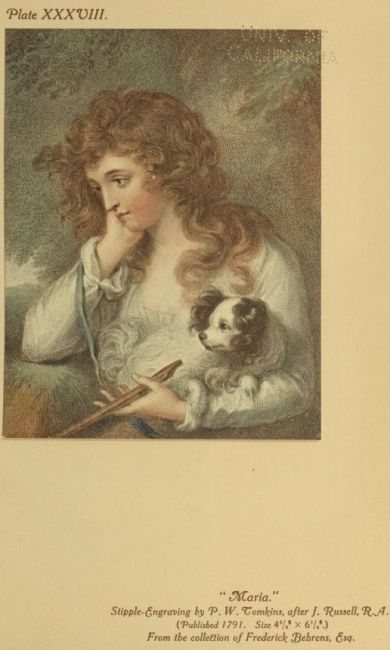

| ” | XXXVIII. | “Maria.” Stipple-Engraving by P. W. Tomkins, after J. Russell, R.A. |

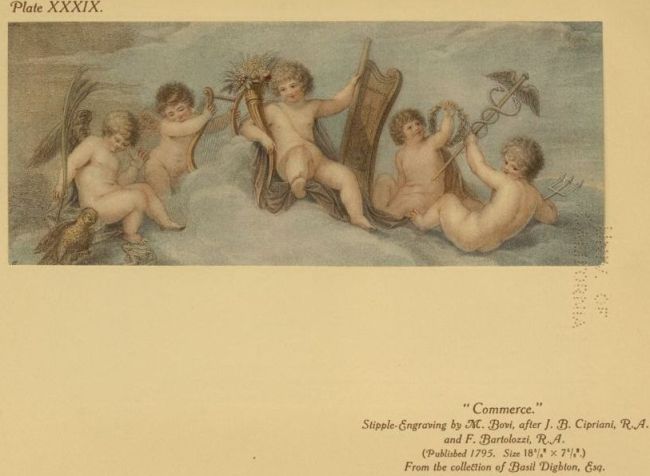

| ” | XXXIX. | “Commerce.” Stipple-Engraving by M. Bovi, after J. B. Cipriani, R.A., and F. Bartolozzi, R.A. |

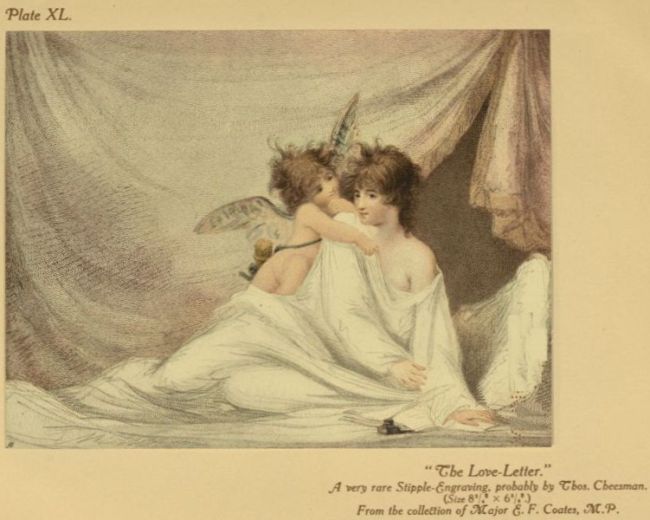

| ” | XL. | “The Love-Letter.” Stipple-Engraving, probably by Thos. Cheesman. |

[1]

“Other pictures we look at—his prints we read,” said Charles Lamb, speaking with affectionate reverence of Hogarth. Now, after “reading” those wonderful Progresses of the Rake and the Harlot, which had for him all the effect of books, intellectually vivid with human interest, let us suppose our beloved essayist looking at those “other pictures,” Morland’s “Story of Letitia” series, in John Raphael Smith’s charming stipple-plates, colour-printed for choice, first issued while Lamb was hardly in his teens. Though they might not be, as in Hogarth’s prints, “intense thinking faces,” expressive of “permanent abiding ideas” in which he would read Letitia’s world-old story, Lamb would doubtless look at these Morland prints with a difference. He would look at them with an interest awakened less by their not too poignant intention of dramatic pathos than by the charm of their simple pictorial appeal, heightened by the dainty persuasion of colour.

There is a fascination about eighteenth-century prints which tempts me in fancy to picture the gentle Elia stopping at every printseller’s window that lay on his daily route to the East India House in Leadenhall Street. How many these were might “admit a wide solution,” since he arrived invariably late at the office; but Alderman Boydell’s in Cheapside, where the engraving art could be seen in its dignified variety and beauty, and Mr. Carington Bowles’s in St. Paul’s Churchyard, with the humorous mezzotints, plain and coloured, must have stayed him long. Then, surely among the old colour-prints which charm us to-day there were some that would make their contemporary appeal to Elia’s fancy, as he would linger among the curious crowd outside the windows of Mr. J. R. Smith in King Street, Covent Garden, or Mr. Macklin’s Poet’s Gallery in Fleet Street, Mr. Tomkins in Bond Street, or Mr. Colnaghi—Bartolozzi’s “much-beloved Signor Colnaghi”—in Pall Mall. Not arcadian scenes, perhaps, with “flocks of silly sheep,” nor “boys as infant Bacchuses or Jupiters,” nor even the beautiful ladies of rank and fashion; but the Cries of London at Colnaghi’s must have arrided so true a Londoner, and may we not imagine the relish with which Lamb would stop to look at the prints of the players? The Downman Mrs. Siddons, say, or the Miss Farren, or that most joyous of Romney prints, Mrs. Jordan as “The Romp”, which would seem to give pictorial justification for Lamb’s own vivid reminiscence of the actress, as his words lend almost the breath of life to the picture. Yet these had not then come to the dignity of “old prints,” with a mellow lure of antique tone.[2] Their beautiful soft paper—hand-made as a matter of course, since there was no other—which we handle and hold up to the light with such sensitive reverence, was not yet grown venerable from the touch of long-vanished hands. They were as fresh as a busy industry of engravers, printers, and paper-makers could turn them out, and of a contemporary popularity that died early of a plethora.

What, then, is their peculiar charm for us to-day, those colour-prints of stipple or mezzotint engravings which pervaded the later years of the eighteenth century, and the earliest of the nineteenth? No serious student, perhaps, would accord them a very high or important place in the history of art. Yet a pleasant little corner of their own they certainly merit, representing, as they do, a characteristic contemporary phase of popular taste, and of artistic activity, essentially English. Whatever may be thought of their intrinsic value as works of art, there is no denying their special appeal of pictorial prettiness and sentiment and of dainty decorative charm. Nor, to judge from the recent records of the sale-rooms, would this appeal seem to be of any uncertain kind. It has lately been eloquent enough to compete with the claims of artistic works of indisputable worth, and those collectors who have heard it for the first time only during the last ten years or so have had to pay highly for their belated responsiveness. Those, on the other hand, who listened long ago to the gentle appeal of the old English colour-prints, who listened before the market had heard it, and, loving them for their own pretty sakes, or their old-time illustrative interest, or their decorative accompaniment to Sheraton and Chippendale, would pick them up in the printsellers’ shops for equitable sums that would now be regarded as “mere songs,” can to-day look round their walls at the rare and brilliant impressions of prints which first charmed them twenty or thirty years ago, and smile contentedly at the inflated prices clamorous from Christie’s. For nowadays the decorative legacy of the eighteenth century—a legacy of dignity, elegance, beauty, charm—seems to involve ever-increasing legacy duties, which must be paid ungrudgingly.

A collector, whose house is permeated with the charm and beauty of eighteenth-century arts and crafts, asked recently my advice as to what he should next begin to collect. I suggested the original pictures of the more accomplished and promising of our younger living painters, a comparatively inexpensive luxury. He shook his head, and, before the evening, a choice William Ward, exceptional in colour, had proved irresistible. Yes, it is a curious and noteworthy fact that the collector of old English colour-prints has rarely, if ever, any sympathy with modern art, however fine, however beautiful. He will frankly admit this, and, while he tells[3] you that he loves colour, you discover that it is only colour which has acquired the mellowing charm of time and old associations. So your colour-print collector will gladly buy a dainty drawing by Downman, delicately tinted on the back, or a pastel by J. R. Smith, somewhat purple, maybe, in the flesh-tints, while the sumptuous colouring of a Brangwyn will rouse in him no desire for possession, a Lavery’s harmonies will stir him not at all, and the mystic beauty of tones in any Late Moonrise that a Clausen may paint will say to him little or nothing. But then, one may ask, why is he content with the simple colour-schemes of these dainty and engaging prints, when the old Japanese, and still older Chinese, colour-prints offer wonderful and beautiful harmonies that no English colour-printer ever dreamt of? And why, if we chance to meet this lover of colour at the National Gallery, do we find him, not revelling joyously in the marvellously rich, luminous tones of a Filippino Lippi, for example, or the glorious hues of a Titian, but quietly happy in front of, say, Morland’s Inside of a Stable, or Reynolds’s Snake in the Grass?

Well, we have only to pass a little while in his rooms, looking at his prints in their appropriate environment of beautiful old furniture, giving ourselves up to the pervading old-time atmosphere, and we shall begin to understand him and sympathise with his consistency. And, as the spell works, we shall find ourselves growing convinced that even a Venice set of Whistler etchings would seem decoratively incongruous amid those particular surroundings. For it is the spell, not of intrinsic artistic beauty, but of the eighteenth century that is upon us. It is the spell of a graceful period, compact of charm, elegance and sensibility, that these pretty old colour-prints, so typically English in subject and design, cast over us as we look at them. Thus they present themselves to us, not as so many mere engravings printed in varied hues, but rather as so many pictorial messages—whispered smilingly, some of them—from those years of ever-fascinating memory, when the newly-born Royal Academy was focussing the artistic taste and accomplishment of the English people, and Reynolds, Gainsborough, Romney, were translating the typical transient beauty in terms of enduring art, while the great engravers were extending the painters’ fame, and the furniture-makers and all the craftsmen were supporting them with a new and a classic grace; when Johnson was talking stately, inspiring common-sense, Goldsmith was “writing like an angel,” and Sheridan was “catching the manners living as they rose”; when Fanny Burney was keeping her vivid diaries, and Walpole and Mrs. Delany were—we thank Providence—writing letters; when the doings of the players at Drury Lane and Covent Garden, or the fashionable revellers at Ranelagh, Vauxhall, and the Pantheon, were as momentous to “the[4] town” as the debates at Westminster, and a lovely duchess could immortalise a parliamentary election with a democratic kiss. These prints, hinting of Fielding and Richardson, Goldsmith and Sterne, tell us that sentiment, romantic, rustic and domestic, had become as fashionable as wit and elegance, and far more popular; while a spreading feeling for nature, awakened by the poetry of Thomson, Gray and Collins, and nurtured later by Cowper, Crabbe and Burns, was forming a popular taste quite out of sympathy with the cold academic formalism and trammelled feeling of the age of Pope.

These literary influences are important to consider for any true appreciation of these old colour-prints, which, being a reflex in every respect of the popular spirit and character of the period in which they were produced, no other period could have bequeathed to us exactly as they are. And it is especially interesting to remember this, for, from the widespread popularity of these very prints, we may trace, in the pictures their great vogue called for, the origin of that abiding despot of popular English art which Whistler has, in his whimsical way, defined as the “British Subject.”

That the evolution of the colour-print, from its beginnings in chiaroscuro, can boast a long and fascinating history has been proved to admiration in the romantic and informing pages of Mrs. Frankau’s “Eighteenth-Century Colour-Prints”—a pioneer volume; but my present purpose is to tell the story only in so far as it concerns English art and taste.

Now, although during the seventeenth century we had in England a number of admirable and industrious engravers, we hear of no attempts among them to print engravings in anything but monochrome; so that, if they heard of the colour-experiments of Hercules Seghers, the Dutch etcher, whom Rembrandt admired, as doubtless they did hear, considering how constant and friendly was their intercourse with the Dutch and Flemish painters and engravers, none apparently thought it worth while to pursue the idea. But, after all, Seghers merely printed his etchings in one colour on a tinted paper, which can hardly be described as real colour-printing; and, if there had been any artistic value in the notion, would not the enterprising Hollar have attempted some use of it? Nor were our English line-engravers moved by any rumours they may have heard, or specimens they may have seen, of the experiments in colour-printing, made somewhere about 1680, by Johannes Teyler, of Nymegen in Holland, a painter, engraver, mathematical professor and military engineer. His were unquestionably the first true colour-prints, being impressions taken from one plate, the engraved lines of which were carefully painted with inks of different hues; and these prints may be seen in the British Museum, collected in all[5] their numerous variety in the interesting and absolutely unique volume which Teyler evidently, to judge from the ornately engraved title-page, designed to publish as “Opus Typochromaticum.”

The experiment was of considerable interest, but one has only to look at these colour-printed line-engravings, with their crude juxtaposition of tints, to feel thankful that our English line-engravers were not lured from their allegiance to the black and white proper to their art. Doubtless they recognised that colour was opposed to the very spirit of the line-engraver’s art, just as, a hundred years later, the stipple-engravers realised that it could often enhance the charm of their own. In the black and white of a fine engraving there is a quality in the balancing of relative tones which in itself answers to the need of colour, which, in fact, suggests colour to the imagination; so the beauty and dignity of the graven line in a master’s hands must repel any adventitious chromatic aid. A Faithorne print, for instance, with its lines and cross-hatchings in colours is inconceivable; although one might complacently imagine Francis Place and Gaywood having, not inappropriately, experimented with Barlow’s birds and beasts after the manner of those in Teyler’s book. If, however, there were any English engravings of that period on which Teyler’s method of colour-printing might have been tried with any possibility of, at least, a popular success, they were surely Pierce Tempest’s curious Cryes of the City of London, after “Old” Laroon’s designs, which antedated by just over a hundred years the charming Wheatley “Cries,” so familiar, so desirable, in coloured stipple. But this was not to be, and not until the new and facile mezzotint method had gradually over-shadowed in popularity the older and more laborious line-engraving was the first essay in colour-printing made in England. In the year 1719 came Jacob Christopher Le Blon with his new invention, which he called “Printing Paintings.”

This invention was in effect a process of taking separate impressions, one over the other, from three plates of a desired picture, engraved in mezzotint, strengthened with line and etching, and severally inked each with the proportion of red, yellow, or blue, which, theorising according to Newton, Le Blon considered would go to make, when blended, the true colour-tones of any picture required. In fact, Le Blon practically anticipated the three-colour process of the present day; but in 1719 all the circumstances were against his success, bravely and indefatigably as he fought for it, influentially as he was supported.

Jacob Christopher Le Blon was a remarkable man, whose ingenious mind and restless, enthusiastic temperament led him through an artistic career of much adventure and many vicissitudes.[6] Born in Frankfort in 1667—when Chinese artists were producing those marvels of colour-printing lately discovered by Mr. Lawrence Binyon in the British Museum—he studied painting and engraving for a while with Conrad Meyer, of Zurich, and subsequently in the studio of the famous Carlo Maratti at Rome, whither he had gone in 1696, in the suite of Count Martinetz, the French Ambassador. His studies seem to have been as desultory as his way of living. His friend Overbeck, however, recognising that Le Blon had talents which might develop with concentrated purpose, induced him in 1702 to settle down in Amsterdam and commence miniature-painter. The pictures in little which he did for snuff-boxes, bracelets, and rings, won him reputation and profit; but the minute work affected his eyesight, and instead he turned to portrait-painting in oils. Then the idea came to him of imitating oil-paintings by the colour-printing process, based on Newton’s theory of the three-colour composition of light, as I have described. Experimenting with promising results on paintings of his own, he next attempted to reproduce the pictures of the Italian masters, from which, under Maratti’s influence, he had learnt the secrets of colour. Without revealing his process, he showed his first “printed paintings” to several puzzled admirers, among them Prince Eugène of Savoy and, it is said, the famous Earl of Halifax, Newton’s friend, who invented the National Debt and the Bank of England. But, sanguine as Le Blon was that there was a fortune in his invention, he could obtain for it neither a patent nor financial support, though he tried for these at Amsterdam, the Hague, and Paris.

His opportunity came, however, when he met with Colonel Sir John Guise. An enthusiastic connoisseur of art, a collector of pictures (he left his collection to Christchurch College, Oxford), an heroic soldier, with a turn for fantastic exaggeration and romancing, which moved even Horace Walpole to protest, and call him “madder than ever,” Guise was just the man to be interested in the personality and the inventive schemes of Le Blon. Easily he persuaded the artist to come to London, and, through his introduction to many influential persons, he enlisted for Le Blon the personal interest of the King, who granted a royal patent, and permitted his own portrait to be done by the new process, of which this presentment of George I. is certainly one of the most successful examples, happiest in tone-harmony. Then, in 1721, a company was formed to work under the patent, with an establishment known as the “Picture Office,” and Le Blon himself to direct operations. Everything promised well, the public credit had just been restored after the South Sea Bubble, the shares were taken up to a substantial extent, and for a time all went well. An interesting prospectus[7] was issued, with a list of colour-prints after pictures, chiefly sacred and mythological, by Maratti, Annibale Carracci, Titian, Correggio, Vandyck, some of them being identical in size with the original paintings, at such moderate prices as ten, twelve, and fifteen shillings. Lord Percival, Pope’s friend, who, like Colonel Guise, had entered practically into the scheme, was enthusiastic about the results. Sending some of the prints, with the bill for them, to his brother, he wrote: “Our modern painters can’t come near it with their colours, and if they attempt a copy make us pay as many guineas as now we pay shillings.” Certainly, if we compare Le Blon’s Madonna after Baroccio—priced fifteen shillings in the prospectus—for instance, with such an example of contemporary painting as that by Sir James Thornhill and his assistants, taken from a house in Leadenhall Street, and now at South Kensington, we may find some justification for Lord Percival’s enthusiasm. For colour quality there is, perhaps, little to choose between them, but as a specimen of true colour-printing, and the first of its kind, that Madonna is wonderful, and I question whether, in the later years, there was any colour-printing of mezzotint to approach it in brilliance of tone. Then, however, accuracy of harmonies was assured by adopting Robert Laurie’s method, approved in 1776, of printing from a single plate, warmed and lightly wiped after application of the coloured inks.

Discouragement soon fell upon the Picture Office. In March 1722 Lord Percival wrote:—“The picture project has suffered under a great deal of mismanagement, but yet improves much.” In spite of that improvement, however, a meeting of shareholders was held under the chairmanship of Colonel Guise, and Le Blon’s management was severely questioned. The shareholders appear to have heckled him quite in the modern manner, and he replied excitedly to every hostile statement that it was false. But there was no getting away from figures. At a cost of £5,000 Le Blon had produced 4,000 copies of his prints—these were from twenty-five plates—which, if all had been sold at the prices fixed, would have produced a net loss of £2,000. Even Colonel Guise could hardly consider these as satisfactory business methods, and the company had already been reorganised, with a new manager named Guine, who had introduced a cheaper and more profitable way of producing the prints. It was all to no purpose. Prints to the value of only £600 were sold at an expenditure of £9,000, while the tapestry-weaving branch of the business—also Le Blon’s scheme—showed an even more disproportionate result. Bankruptcy followed as a matter of course, and Le Blon narrowly escaped imprisonment.

The colour-printing of engravings, though artistically promising,[8] while still experimental, had certainly proved a financial failure, but Le Blon, nothing daunted, sought to explain and justify his principles and his practice in a little book, called “Coloritto, or the Harmony of Colouring in Painting, reduced to mechanical practice, under easy precepts, and infallible rules.” This he dedicated to Sir Robert Walpole, hoping, perhaps, that the First Lord of the Treasury, who had just restored the nation’s credit, might do something for an inventive artist’s. Next he was privileged to submit his inventions to the august notice of the Royal Society. Le Blon had always his opportunities, an well a his rebuff from fortune, but his faith in himself and his ideas was unswerving; moreover, he had the gift of transmitting this faith to others. At last a scheme for imitating Raphael’s cartoons in tapestry, carried on at works in Chelsea, led to further financial disaster and discredit, and Le Blon was obliged to fly from England.

In Paris he resumed his colour-printing, inspiring and influencing many disciples and imitators, among them Jacques Fabian Gautier D’Agoty, who afterwards claimed to have invented Le Blon’s process, and transmitted it to his sons. In Paris, in 1741, Le Blon died, very, very poor, but still working upon his copper-plates. It was doubtless during Le Blon’s last years in Paris that Horace Walpole met him. “He was a Fleming (sic), and very far from young when I knew him, but of surprising vivacity and volubility, and with a head admirably mechanic; but an universal projector, and with, at least, one of the qualities that attend that vocation, either a dupe or a cheat: I think the former, though, as most of his projects ended in the air, the sufferers believed the latter. As he was much an enthusiast, perhaps like most enthusiasts he was both one and t’other.” As a matter of fact, Le Blon was neither a dupe nor a cheat; he was simply a pioneer with all the courage of his imagination and invention; and no less an authority than Herr Hans W. Singer, of Vienna, has considered him, with all his failures and shortcomings, of sufficient artistic importance to be worthy of a monograph.

If, by a more judicious selection of pictures for copying, Le Blon had been able to create a popular demand, and to ensure general encouragement for his venture, how different might have been the story of colour-printing, how much fuller its annals. For Le Blon’s ultimate failure was not owing to the comparative impossibility or getting infallibly the required harmonics of his tones with only the three cardinal colours, and the necessity to add a fourth plate with a qualifying black, or to the difficulty in achieving the exactness of register essential to the perfect fusing of the tones of several plates. Those were serious obstacles, certainly, hindering complete artistic success; but, judging from the surprising excellence of the best of[9] Le Blon’s actual achievements, they would doubtless have been surmounted for all practical purposes. The real cause of the failure was, I suggest, that the pictures actually reproduced made no appeal to the people of England, consequently there was no public demand for the prints. It was a close time for the fine arts in this country. The day of the public picture-exhibition was nearing, but it had not yet arrived. The aristocratic collector and the fashionable connoisseur represented the taste of the country, for popular taste there was none. Romance and sentiment were quite out of fashion, and the literature of the day was entirely opposed to them. Nor were there any living painters with even one touch of nature. The reign of George I. was indeed a depressing time for the graphic arts. Society, heavily bewigged and monstrously behooped, was too much concerned with its pastimes and intrigues, its affectations, caprices and extravagances, to cultivate any taste or care for beauty. Kent, the absurdly fashionable architect, was ruling in place of the immortal Wren, and Kneller was so long and so assuredly the pictorial idol of the country that Pope, its poet-in-chief, could actually write of him that “great Nature fear’d he might outvie her works.” Then, all else of pictorial art meant either Thornhill’s wearisome ceilings and stair-cases, or the stiff and tasteless portraiture, with stereotyped posture, of the lesser Knellers, such as Jonathan Richardson, Highmore, and Jervas, whom Pope made even more ridiculous by his praises.

With only such painters as these to interpret, what chance had even such admirable engravers as John Smith, George White, John Simon, Faber, Peter Pelham, whose mezzotints even were beginning to wane in favour for lack of pictorial interest? It is no great wonder then that, seeing Le Blon’s failure, in spite of all his influence and achievement, the engravers in mezzotint were not eager to try the principles of his “Coloritto” in their own practice, and so colour-printing suffered a set-back in this country. But Le Blon’s prints are of great value to-day. What, then, has become of those 9,000 copies printed by the Picture Office? The £600 worth sold before the bankruptcy must have represented about a thousand, yet these impressions from Le Blon’s fifty-plates are of extreme rarity even in the museums of the world, and it has been suggested by Herr Singer, and also by Mr. A. M. Hind, in his valuable “History of Engraving and Etching,” that many copies of the large prints, varnished over, may be hanging in old houses under the guise of oil paintings, thus fulfilling their original purpose. It is an interesting conjecture, and how plausible one may judge from the varnished copies in the British Museum.

Le Blon’s really important venture inspired no imitators in England, but it was followed by a few experimental attempts to[10] embellish engravings with colour. These were chiefly adaptations of the old chiaroscuro method, surface-colour being obtained by using several wood-blocks in combination with engraved copper-plates. Arthur Pond and Charles Knapton, painters both, imitated a number of drawings in this manner, the designs being etched; while, some years earlier, Elisha Kirkall (“bounteous Kirkall” of the “Dunciad”) had successfully used the coloured wood-blocks with mezzotint plates, strengthened with etched and graven lines. His pupil, J. B. Jackson, however, engraved only wood for his remarkable prints. But these experiments were merely sporadic; they led to nothing important and continuous in the way of colour-printing.

Meanwhile, the prints of Hogarth, with their marvellous pictorial invention, mordant satire, and moral illumination, took the fancy of the town without the lure of colour, and cultivated in the popular mind a new sense of picture, concerned with the live human interest of the passing hour. Other line-engravers, too,—Vivares, Woollett, Ravenet, Major, Strange,—with more masterly handling of the graver, were, through the new appeal of landscape, or the beauties of Rembrandt and the Italian masters, or the homely humours of Dutch genre, winning back the popular favour for their art.

Though the call for the colour-print had not yet arrived, the way was preparing for it. With this widening public interest in pictorial art, a dainty sense of tone was awakened by the porcelain now efflorescing all aver the country. Then, when Reynolds was bringing all the graces to his easel, the urbane influence for beauty spread from the master’s painting-room at 47, Leicester Fields—as the Square was then called—to all the print-shops in town. And the year—1764—that saw the death of Hogarth was the year in which Francesco Bartolozzi came to England, bringing with him into the engraving-world fresh influences of grace and delicacy which gradually ripened for colour.

The sentimental mood for the storied picture was now being fostered by the universal reading of the novel, which in its mid-eighteenth-century form gave its readers new experiences in the presentation of actual contemporary life, with analysis of their feelings and cultivation of there sensibilities. Pamela and Clarissa Harlowe, Sophia Western and Amelia, Olivia, Maria, were as living in interest as any of the beautiful high-born ladies whose portraits in mezzotint, translated from the canvasses of the great painters, appealed from the printsellers’ windows in all the monochrome beauty of their medium. The public, steeped now in sentiment, wanted to see their imaginary heroines in picture: nor had they[11] long to wait. The Royal Academy had become a vital factor in forming public taste, and the printsellers’ shops were its mirrors. But not all its members and exhibitors were Gainsboroughs and Reynoldses. There were, for instance, Angelica Kauffman and Cipriani, with their seductive Italian graces of design; there was Bartolozzi, with his beautiful draughtsmanship, and his brilliant facile craft on the copper-plate, but the medium that should bring these into familiar touch with popular taste was still to seek. However, it was at hand, and the man who found this medium, and brought it to the service of popular art, was William Wynne Ryland, “engraver to the King.”

Whether the so-called crayon method of engraving, in imitation of soft chalk drawings, was invented by Jean Charles François, or Gilles Demarteau, or Louis Bonnet—all three claimed the credit of it—it was, at all events, from François, whose claim had obtained official recognition, that Ryland, the pupil of Ravenet and Le Bas, and, in a measure, of Boucher, learned the method while he was still a student in Paris. Only later in his career, however, long after he had left behind him his student days in Paris and Rome, and achieved prosperity in London as a line-engraver and printseller, with royal patronage, and with social success as a man of fashion and pleasure, did he remember the process that François had imparted to him. Then, in his necessity, when his extravagances had brought him to bankruptcy, he called the dotted crayon manner to memory, and saw in stipple-engraving, if suitably employed, a possible asset of importance. Compared with line and even with mezzotint it was a very easy and rapid way of engraving, and though, of course, it could not compare with either in nobility, richness and brilliance of effect, Ryland realised that its soft rendering of tones by artistically balanced masses of dots might be adapted to dainty and delicate drawings. The most fortunate opportunity for proving this was at hand. He had some personal acquaintance with Angelica Kauffman, whom Lady Wentworth had brought to London some ten years before, and whose beauty, talents and personal charm had meanwhile made her a fashionable artistic idol, with Society and its beauties flocking to her studio to be painted or to buy her pictures. Having first tested his stippling with his own designs, gracefully French in manner, which he published soon afterwards as “Domestic Employments,” Ryland suggested the idea of stipple-engraving to the sympathetic young painter. When he had experimented with one or two of her drawings, she gladly recognised that stipple was the very medium for the interpretation of her work to the public. The first prints sold “like wildfire,” and so satisfied was Ryland of the profitable[12] prospect, that, on the strength of it, he promptly re-established himself in a printselling business at 159, Strand. His confidence was amply justified, the public being quick to show their appreciation of the new method, introduced as it was with all the persuasion of the fair Angelica’s graceful, fanciful designs of classic story and allegory. This was in 1775, and within a very short time Ryland found that, rapidly as she designed and he engraved, he could scarcely keep pace with the demand for these prints, which, the more readily to crave the popular fancy, he printed in red ink, to imitate red chalk, later to be known as the “Bartolozzi red.”

Ryland had called Bartolozzi into consultation, and the gifted Italian engraver, with his greater mastery of technique, his delicate sense of beauty, and his finer artistic perceptions, had seen all that might be done with the new way of stipple; he saw also its limitations. With enthusiasm Bartolozzi and Ryland had worked together till they had evolved from the crayon manner of François a process of engraving which proved so happily suited to the classes of fanciful and sentimental prints now fast becoming the vogue, that it simply jumped into a popularity which no other medium of the engraver’s art had ever attained.

The stipple method may be thus described. The copper-plate was covered with an etching-ground, on to which the outlined picture was transferred from paper. Then the contours of the design were lightly etched in a series of dots, all the dark and middle shadows being rendered by larger or more closely etched dots, the later engravers using even minute groups of dots. This accomplished, the acid was next applied with very great care, and all the etched dots bitten in. The waxen ground was then removed from the plate, and the work with the dry-point and the curved stipple-graver was commenced. With these tools the lighter shadows were accomplished, and the bitten portions of the picture were deepened and strengthened wherever required, to attain greater fulness or brilliance of effect.

Engraving in dots was, of course, no new thing; as an accessory to line-engraving it had often been called into service by the earlier artists. Giulio Campagnola, Albert Dürer, Agostino Veneziano, Ottavio Leoni, for example, had used it; we frequently find it employed by our own seventeenth-century line-men the better to suggest flesh-tones, and Ludwig von Siegen, in describing his invention of mezzotint in 1642, includes the “dotted manner” among the known forms of engraving. Then there was the opus mallei, or method of punching dots in the plate with a mallet and awl, which was successfully practised by Jan Lutma, of Amsterdam, late in the seventeenth century. This may be considered the true[13] precursor of stipple, just as the harpsichord, with the same keyboard, but a different manner of producing the notes, was the precursor of the pianoforte; but it must have been a very laborious process, and Lutma found few imitators.

Under the ægis of Ryland and Bartolozzi, however, and with the inspiration of Angelica Kauffman’s “harmonious but shackled fancy,” as a contemporary critic put it, for its initial impetus, stipple was developed as a separate and distinctive branch of the engraver’s art. Its popularity was now to be further enhanced by the gentle and persuasive aid of colour. Ryland had seen many specimens of colour-printing in Paris, when he was with François and with Boucher; he now bethought him that, just as the public fancy had been captured by red-chalk imitations, so might it be enchanted by engraved representations of water-colour drawings actually printed in colours. Angelica Kauffman and Bartolozzi eagerly encouraged the idea, and the two engravers, after many experiments, determined the best process of colouring and printing from the plates. Apparently they rejected the multi-plate method tried six years previously by that interesting artist Captain William Baillie; and Ryland’s earliest colour-prints were partially tinted only with red and blue. Mrs. Frankau tells us, on the authority of a tradition handed down in his old age from James Minasi, one of Bartolozzi’s most trusted pupils, that an Alsatian named Seigneuer was responsible for all the earlier colour-printed impressions of Ryland’s and Bartolozzi’s stipples after Angelica Kauffman and Cipriani, that then he set up on his own account as a colour-printer, much recommended by Bartolozzi, and largely employed by the publishers, and that his printing may be traced, though unsigned, by a transparency of tone due to the use of a certain vitreous white which he imported in a dry state from Paris. Minasi must, of course, have been a perfect mine of Bartolozzi traditions, but when my father in his boyhood knew him and his musical son, the distinguished engraver would talk of nothing but music, for in 1829, with steel plates superseding the copper, and lithography triumphant, there seemed no prospect that the coloured stipples, already some time out of fashion, would eighty years later be inspiring curiosity as to how they were done. One sees, of course, many feeble colour-prints of the period, which of old the undiscriminating public accepted as readily as to-day they buy, for “old prints,” modern cheap foreign reproductions which would disgrace a sixpenny “summer number.” On the other hand, the really fine examples of the old-time colour-printing, combined with brilliant engraving—and, of course, only fine things are the true collector’s desiderata, irrespective of margins and “state” letterings, and other[14] foolish fads—are certainly works of art, though a very delicate art of limited compass.

These colour-prints were done with a single printing, and the plate had to be freshly inked for each impression. The printer would have a water-colour drawing to work from, and having decided upon the dominant tint, with this he would ink over the whole engraved surface of the plate. Then he would wipe it almost entirely out of the incisions and punctures on the copper which had retained it, leaving just a sufficient harmonising ground-tint for the various coloured inks, carefully selected as to tints, which were next applied in the exact order and degree to ensure the right harmonies. All this required the nicest care directed by a very subtle sense of colour. Most difficult of all, and reserved for the last stage of the inking, was adding the flesh-tints, an operation of extreme delicacy. Then, before putting the plate in the printing-press, it had to be warmed to the exact degree of sensitiveness which should help the colours to fuse with tenderness and softness, without losing any brilliant quality of tone. This was not the least anxious part of the work, needing highly-trained artistic sensibility on the part of the printer. How artistically important this matter of warming the plates must have been in printing a combination of coloured inks may be judged when I say that I have been privileged to watch Whistler warming his etched plates ready for the printing-press, and seen him actually quivering with excited sensibility as the plate seemed to respond sensitively to the exigence of his own exquisite sense of tone. But, of course, no eighteenth-century colour-prints, however charming in tone, suggest that there were any Whistlers engaged in the printing of them. Perhaps that is why our modern master of the copper-plate never cared for these dainty things, as he did greatly care for Japanese colour-prints. The old printers, however, had their own definite manner of work, and their own tricks of experience for producing pleasing and brilliant effects. By the dusting of a little dry colour on to the moist, here and there, during the printing process, they could heighten tones, or by very, very lightly dragging a piece of muslin over the surface of the plate they could persuade the tints to a more tender and harmonious intimacy. Of course, when the plate was printed, the colour was taken only by the dots and lines of the engraving, the white paper peeping between. If would-be buyers of colour-prints would only remember this simple fact, and examine the stippling closely to see whether it really shows the colour, they would not so constantly be deceived into buying entirely hand-coloured prints. Whether the old printers and engravers authorised and sponsored the touching-up of the prints with water-colour which one almost invariably finds,[15] at least to some slight extent, even in the best examples, with rare exceptions, it is impossible to determine. At all events, it is presumable that the eyes and lips were touched up before the prints left the publishers’ shops.

It must not be supposed, however, that colour had ousted from public favour the print in monochrome. As a matter of fact, it was usually only after the proofs and earlier brilliant impressions in monochrome had been worked off, and the plate was beginning to look a little worn, that the aid of colour was called in to give the print a fresh lease of popularity. Indeed, with mezzotint a slightly worn plate generally took the colours most effectively. This is why one sees so very seldom an engraver’s proof in colours, the extreme rarity of its appearance making always a red-letter moment at Christie’s. Therefore, in spite of the ever-widening vogue of the colour-print, it was always the artist and engraver that counted, while the printer in colours was scarcely ever named. And the new industry of stipple-engraving may be said to have been, in its first days of popularity, monopolised almost by Ryland and Bartolozzi, in association with Angelica Kauffman and John Baptist Cipriani.

Cipriani had, by his elegant and tasteful designs, won immediate favour on his arrival in England, and even the Lord Mayor’s coach was decorated with panels of his painting. His style prepared the way for Angelica Kauffman, and together they soon brought a new pictorial element to the service of home-decoration. Their graceful rhythmic treatment of classic fables was just what the brothers Adam wanted for their decorative schemes, and the two Italian artists were extensively employed to paint panels for walls and ceilings. In time the fair Angelica outdistanced Cipriani in popularity, and, painting panels for cabinets, commodes, pier-table tops, and other pieces of decorative furniture, her taste was soon dominating that of the fashionable world. No wonder then that, when Ryland and Bartolozzi, through the medium of their facile and adaptable engravings, made her charming, if not flawlessly drawn, compositions readily accessible, the public eagerly bought them, and, framing them, generally without any margin, according to their own oval and circular forms, found them the very mural adornments that the prevailing Adam taste seemed to suggest. In monochrome or in colours, the prints, with their refined and fluent fancies, pictured from Horace, Ovid, Virgil, Homer, and Angelica’s beautiful face and figure vivid in several, had an extraordinarily wide appeal. They flattered the fashionable culture of the day, when to quote Horace familiarly in ordinary conversation was almost a patent of gentility. On the continent they were even copied for the decoration of porcelain.

[16]

For Ryland this meant another spell of prosperity: it also meant disaster. His constant thirst for pleasure, and his ambition to shine as a fine gentleman, stimulated by such easy and seemingly inexhaustible means of money-making, led him into fatal extravagances. Accused of forging a bill, instead of facing the charge, of which he protested his innocence, he stupidly hid himself and tried ineffectually to cut his own throat. After that, some flimsy evidence procured his condemnation, and, as William Blake, looking in Ryland’s face, had predicted years before, he was hanged at Tyburn in 1783.

They could have done no worse to a highwayman; and, after all, by the introduction of stipple-engraving Ryland had certainly increased the people’s stock of harmless pleasure. In his own stippling there was a delicacy of touch, a smoothness of effect, equal to Bartolozzi’s, but with less tenderness and suppleness of tone. Evidently he formed his style to suit the designs of Angelica Kauffman, which it rendered with appreciation of their refinement. This will be seen in the charming Cupid bound to a Tree by Nymphs, among our illustrations, and many other pleasing plates, such as Venus presenting Helen to Paris, Beauty crowned by Love, The Judgment of Paris, Ludit Amabiliter, O Venus Regina, Olim Truncus, Dormio Innocuus, Juno Cestum, Maria, from Sterne’s “Sentimental Journey,” for which Miss Benwell, the painter, is said to have sat; Patience and Perseverance; Morning Amusement, a fanciful portrait of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, embroidering at a tambour-frame, and wearing the Turkish costume which she so graphically describes in one of her letters, and in which Kneller had painted her at the instigation of Pope; fancy portraits, too, of the adventurous Lady Hester Stanhope, and Mary, Duchess of Richmond.

Although Angelica Kauffman had Bartolozzi and his numerous disciple—which meant, of course, most of the best stipple-engravers of the day—at the service of her prolific pencil, her favourite of all was Thomas Burke. In this she proved her sound judgment, for certainly no other stipple-engraver, not Bartolozzi himself, could equal Burke’s poetic feeling upon the copper, or surpass him in his artistic mastery of the medium. After studying, it is believed, at the art school of the Royal Dublin Society, he came to London to learn mezzotint-engraving under his talented countryman, John Dixon, who was winning reputation as one of Reynolds’s ablest “immortalisers,” to borrow the master’s own word. Burke soon showed that he could scrape a mezzotint with the best of them, but the pupil’s manner developed on his own lines, differing from the master’s in a more tender and luminous touch, a greater suavity of tone. These qualities are patent in his beautiful rendering of Angelica Kauffman’s Telemachus at the Court of Sparta, and it was only[17] natural that they should suggest his adopting the stipple method. The technique he learnt from Ryland, and unquestionably he “bettered the instruction.” The painter’s sense of effect, which Dixon had taught him to translate into mezzotint, was of incalculable value to him in his use of the new medium, for, by an individual manner of infinitely close stippling suggestive of the rich broad tone-surfaces of mezzotint, he achieved, perhaps, the most brilliant and beautiful effects that stipple-engraving has ever produced. Burke, in fact, was an artist, who, seeing a picture, realised how to interpret it on the copper-plate with the just expression of all its tone-beauties. There is a glow about his engraving which shows the art of stipple at the very summit of its possibilities, and, happily, brilliant impressions of several of his plates were printed in colours. Thus, in such beautiful prints as Lady Rushout and Daughter, Rinaldo and Armida, A Flower painted by Varelst, Angelica Kauffman as Design listening to the Inspiration of Poetry, Cupid and Ganymede, Jupiter and Calisto, Cupid binding Aglaia, Una and Abra, to name, perhaps, the gems among Burke’s Kauffman prints, is shown what artistic results could be compassed when stipple-engraving and colour-printing met at their best. If, however, Angelica’s engaging fantasies inspired Burke to his masterpieces, not less exquisite was his rendering of Plimer’s miniatures of the Rushout daughters, while his art could interpret with equal charm the homely idyllic picture, as may be seen in the pretty Favourite Chickens—Saturday Morning—Going to Market, after the popular W. R. Bigg, and The Vicar of the Parish receiving his Tithes, after Singleton. But there are pictures by the masters one would like Burke to have engraved. The strange thing is that he did not do them.

Most of the engravers were now wooing the facile and profitable popularity of the stipple method and the colour-print and all the favourite painters of the day, from the President of the Royal Academy to the lady amateur, were taking advantage of the fashion. The constancy and infinitude of the demand were so alluring, and the popular taste, never artistically very exacting, had been flattered and coaxed into a mood which seemed very easy to please. It asked only for the pretty thing.

Sir Joshua Reynolds, seeing, doubtless, what delicious and popular things Bartolozzi had made of Cipriani’s Cupids and Graces, was readily induced to lend himself, in the lighter phases of his art, to the copper-plates of the stipple-engravers, pleasantly assisted by the colour-printer. Still leaving the more dignified and pictorially elaborate examples of his brush, the beautiful, elegant, full-length portraits of lovely and distinguished women and notable men, to the gracious interpretation of mezzotint, which had served him[18] so nobly and faithfully, he found that, in the hands of such artists on copper as Bartolozzi, John Jones, Caroline Watson, Wilkin, Cheesman, Dickinson, Nutter, Schiavonetti, Marcuard, Thomas Watson, John Peter Simon, Grozer, Collyer, J. R. Smith, the delicate art of stipple could express all the sweetness, tenderness, and grace he intended in the pictures he enjoyed to paint of children and of girlish beauty. So we have such delightful prints, both in monochrome and in colour, as the Hon. Anne Bingham and Lavinia, Countess Spencer, Lady Betty Foster, The Countess of Harrington and Children, Lady Smyth and her Children, Lord Burghersh, Hon. Leicester Stanhope, Simplicity (Miss Gwatkin), The Peniston Lamb Children, all of Bartolozzi’s best; Lady Cockburn and her Children, and Master Henry Hoare, the Hon. Mrs. Stanhope as “Contemplation,” Lady Beauchamp (afterwards Countess of Hertford), A Bacchante (Mrs. Hartley, the actress, and her child), the Spencer children in The Mask, and The Fortune Tellers, Miss Elizabeth Beauclerc (Lady Diana’s daughter and Topham Beauclerc’s) as “Una,” Muscipula, Robinetta, Felina, Collina, The Sleeping Girl, Infancy, Lady Catherine Manners, The Reverie, Lord Grantham and his Brothers, Mrs. Sheridan as “St. Cecilia,” Maternal Affection (Lady Melbourne and child), Perdita (Mrs. Robinson), Mrs. Abington as “Roxalana,” The Age of Innocence, The Infant Academy, The Snake in the Grass—but the list is endless. All collectors of colour-prints know how desirable these Reynolds’ stipples are to charm their walls withal, but almost unique must be the collector who can also hang among them Keating’s joyous mezzotint of Reynolds’s famous portrait of the Duchess of Devonshire and her baby daughter, printed in colours. This is one of those rare examples which, with J. R. Smith’s Bacchante and Nature (Lady Hamilton), Henry Meyer’s Nature too, some of the Morland prints by the Wards, Smith, and Keating; S. W. Reynolds’s Countess of Oxford, J. R. Smith’s Mrs. Bouverie, and a few other important Hoppner prints, C. Turner’s Penn Family, after Reynolds, Smith’s Synnot Children, after Wright of Derby, and Mrs. Robinson, after Romney, prove that, in the hands of an engraver with a painter’s eye, mezzotint could respond to the coloured inks as harmoniously and charmingly as stipple.

Gainsborough—at least, the Gainsborough of unapproachable mastery and inimitable beauty, the greatest glory of our eighteenth century art—seems to have been beyond the colour-printer’s ambition. With the exception of the Hobbinol and Ganderetta (Tomkins), reproduced here, and the Lavinia (Bartolozzi), both of which were painted for Macklin’s “British Poets,” I doubt if anything important of Gainsborough’s was reproduced in coloured stipple, and, of course, these things cannot be said adequately to represent[19] the master; while, as to mezzotint, W. Whiston Barney’s version of Gainsborough’s Duchess of Devonshire was, I understand, printed in colours, though impressions are extremely rare. Romney’s exquisite art, on the other hand, with its gracious simplicity of beauty, lent itself more readily to the colour-printed copper-plate. Among the numberless tinted engravings with which the small-paned windows of the eighteenth-century print-shops were crowded, none ingratiated themselves more with the connoisseurs than the Romneys. So, in any representative collections of colour-prints to-day, among the finest and most greatly prized examples must be the lovely Emma and Serena (Miss Sneyd) of John Jones, Mrs. Jordan as “The Romp” of Ogborne, Miss Lucy Vernon as “The Seamstress,” and Lady Hamilton as “The Spinster” of Cheesman, the beautiful Emma also as a “Bacchante” by Knight, as “Sensibility” by Earlom, and as “Nature” in the two mezzotint versions, just mentioned, by J. R. Smith and Henry Meyer.

Of course the pictorial miniatures of the fashionable Richard Cosway, with their light, bright scheme of draughtsmanship, their dainty tints, their soft and sinuous graces, their delicate decision of character, were exceedingly happy in the stipple-engraver’s hands. In colour the prints had a charm of reticence which was peculiarly persuasive. Several of the most engaging were done by the artistic Condé, such at Mrs. Bouverie, Mrs. Tickell, Mrs. Jackson, Mrs. Fitzherbert, Mrs. Robinson as “Melania”, and the beautiful youth Horace Beckford; J. S. Agar did delicately Harriet, Lady Cockerell, as a Gipsy Woman, Lady Heathcote, and Mrs. Duff; Cardon, with his distinguished touch, engraved the charming Madame Récamier, Schiavonetti the Mrs. Maria Cosway and Michel and Isabella Oginesy, Bartolozzi the Mrs. Harding, Mariano Bovi the Lady Diana Sinclair, and Charles White the pretty Infancy (Lord Radnor’s children). Only less fashionable than Cosway’s were the miniatures of Samuel Shelley. In portrait-manner, and in fanciful composition, Reynolds was his model and inspiration, but the result, in spite of high finish and a certain charm of elegance, was a very little Reynolds, for Shelley’s drawing generally left something for criticism. Naturally, miniature-painting found happy interpretation in coloured stipple, and Shelley was fortunate in his engravers, especially Caroline Watson, with her exquisite delicacy and brilliantly minute finish, and William Nutter, who was equally at home with the styles of many painters.

An artist whose dainty and original manner of portraiture, enjoying a great vogue in its day, was also particularly well suited to the tinted stipple was John Downman. A man of interesting personality and individual talent, he began, as a pupil and favourite[20] of Benjamin West, to take himself seriously and ambitiously as an “historical painter,” to borrow a definition of the period. Indeed, after he had won a fashionable reputation for the singular charm and style of his portraits, and become an A.R.A., we find a contemporary critic of the Royal Academy exhibition of 1796 confessing surprise at seeing a scriptural subject painted with such exceptional care and simplicity of expression by “a hand accustomed to delineate the polished and artificial beauties of a great metropolis.” But it was to these portrait-drawings that the artist owed his popularity, and these and the engravings of them, neglected for three-quarters of a century, are the things that to-day make Downman a name to conjure with among collectors. His portraits, exceptionally happy in their suggestion of spontaneous impression and genial intuition of character, were drawn with pencil, or with finely-pointed black chalk or charcoal. The light tinting of hair, cheeks, lips and eyes, with the more definite colouring, in the case of the female portraits, of an invariable sash and ribbon on a white dress, was effected in a manner peculiar to himself. Instead of the usual way, the colour was put on the back of the drawing, and showed through the specially thin paper he used with softened effect. How he happened upon this method of tinting his drawings is rather a romantic story. Seized by the press-gang and taken to sea, about the beginning of the American War of Independence, he was kept abroad for nearly two years, and when, at last, he managed to return to England he found his wife and children in a state of destitution at Cambridge. There his happy gift of portraiture brought him a livelihood. One day he left by chance a drawing face downward upon the table, and one of his children began daubing some pink paint on what was seemingly a blank piece of paper. Downman, finding his drawing with daubs upon the back, perceived delicate tints upon the face, and so he looked with a discoverer’s eye, and thought the thing out; and the novel way he had accidentally found of transparently tinting his drawings proved his way to prosperity. It introduced him into the houses of the socially great to the royal palace even, and the fashionable beauties of the day, as well as those who would have liked to be fashionable beauties, and the favourite actresses, all readily offered their countenances to Downman’s charming pencil, knowing it would lend them the air of happy young girls. Of course there was a willing market for prints from these gladsome and novel presentations of faces which the people seemed never to tire of; so among the collector’s prizes to-day are the Mrs. Siddons by Tomkins, the Duchess of Devonshire and the Viscountess Duncannon by Bartolozzi, Lady Elizabeth Foster by Caroline Watson, Miss Farren (Countess of Derby) by Collyer, and Frances Kemble by John Jones.

[21]

The social reign of the Court beauties lasted over a long period, and survived many changes of fashion, from the macaroni absurdities and monstrous headdresses to the simple muslin gown and the straw “picture” hat. The days of “those goddesses the Gunnings” seemed to have come again when the three rival Duchesses, Devonshire, Rutland, and Gordon, were the autocrats of “the ton,” ruling the modish world not only with the sovereignty of their beauty, elegance, wit and charm, but with the fascinating audacity of their innovations and the outvieing heights of their feathers.

So sang the enthusiastic poet; though the “satirical rogues” who wrote squibs and drew caricatures were not quite so kind, and a writer in the “Morning Post,” with a whimsical turn for statistics, actually drew up a “Scale of Bon Ton,” showing, in a round dozen of the leading beauties of the day the relative proportions in which they possessed beauty, figure, elegance, wit, sense, grace, expression, sensibility, and principles. It is an amusing list, in which we find the lovely Mrs. Crewe, for instance, credited with almost the maximum for beauty, but no grace at all; the Countess of Jersey with plenty of beauty, grace and expression, but neither sense nor principles; the Duchess of Devonshire with more principles than beauty, and more figure than either; her Grace of Gordon with her elegance at zero, and the Countess of Barrymore supreme in all the feminine attractions.

When personal gossip about these fashionable beauties was rampant upon every tongue; when the first appearance of one of them in a new mode was enough to ensure her being enviously or admiringly mobbed in the Mall, naturally the portrait-prints in colour responded to the general curiosity. But there was a public which, having other pictorial fancies than portraiture, even pretty faces could not satisfy without the association of sentiment and story. So there were painters who, recognising this, furnished the engravers with the popular subject-picture. It was well for their link with posterity that they did so, for how many of them would be remembered to-day were it not for these prints? One of the most prominent was William Redmore Bigg, who won a great[22] popularity by painting, with the imagination of a country parson, simple incidents of rustic and domestic life, charged with the most obvious sentiment. The people took these pictures to their hearts, and they were a gold-mine to the engravers. As to their artistic qualities we have little opportunity of judging to-day except through the familiar prints. These are innumerable, and they all have a conventional prettiness. In colours the most pleasing, perhaps, are the Saturday Morning of Burke, the Saturday Evening and Sunday Morning of Nutter; Dulce Domum and Black Monday of John Jones; Romps and Truants of William Ward; Shelling Peas and The Hop Picker of Tomkins; College Breakfast, College Supper, and Rural Misfortunes of Ogborne, The Sailor Boy’s Return and The Shipwrecked Sailor Boy of Gaugain.

Then there was William Hamilton, a prolific and prevalent artist. Sent to Italy in his youth by Robert Adam, the architect, he returned with a sort of Italianate style of storied design, classical, historical, allegorical, conventional; but, happily, he developed a light, pretty and decorative manner of treating simple familiar subjects, which was pleasing alike to engravers and public. The charming plates from Thomson’s Seasons, engraved by Tomkins and Bartolozzi; the graceful set of The Months by Bartolozzi and Gardiner; the idyllic Morning and Evening by Tomkins, with Noon and Night by Delattre, the numerous designs of children at play, such as Summer’s Amusement, Winter’s Amusement, How Smooth, Brother! feel again, The Castle in Danger, by Gaugain; Breaking-up and The Masquerade by Nutter; Blind Man’s Buff and Sea-Saw, Children feeding Fowls, Children playing with a Bird, by Knight; Playing at Hot Cockles, and others by Bartolozzi: these are among the prettiest colour-prints of the period and the most valued to-day—especially The Months. Hamilton’s work just synchronised with the popular vogue for the coloured stipple, and without these prints how much should we know of an artist so esteemed in his day, and so industrious? One might almost ask the same of Francis Wheatley, whose popularity also survives but through the engraver’s medium. It was only after his return from Dublin, where he might have continued to the end as a prosperous portrait-painter had not Dublin society discovered that the lady it had welcomed as Mrs. Wheatley was somebody else’s wife, that Wheatley began painting those idealised urban, rustic, and domestic subjects, which gave him such contemporary vogue and led to his prompt admission among the Royal Academicians. Had he never painted anything else he would always be remembered by his thirteen Cries of London, published by Colnaghi at intervals between 1793 and 1797, and so familiar to us through the accomplished copper-plates of the Schiavonetti brothers, Vendramini, Gaugain[23] and Cardon, though, alas! so wretchedly hackneyed through the innumerable paltry reproductions. But what a fascinating, interesting set of prints it is! How redolent of old lavender! How clean, serene, and country-town-like the London streets appear; how sweet and fragrant they seem to smell; how idyllic the life in them! As one looks at these prints one can almost fancy one hears the old cries echoing through those quiet Georgian streets. Perhaps the London streets of 1795 were not quite so dainty as Wheatley’s sympathetic pencil makes them look to have been. But, remember, that in those days lovely ladies in muslin frocks and printed calicoes of the new fashion, who had sat to Reynolds, and whose portraits were in the print-shop windows, were still being carried in the leisurely sedan-chair, and there were many pretty airs and graces to be seen; while in those streets, too, the youthful Turner was seeing atmosphere and feeling his graphic way to immortality, and young Charles Lamb was walking about, “lending his heart with usury” to all the humanity he saw in those very streets which these Wheatley prints keep so fragrant. Of the numberless other colour-prints after Wheatley perhaps the most valued to-day are, in mezzotint, The Disaster, The Soldier’s Return and The Sailor’s Return, by William Ward, The Smitten Clown, by S. W. Reynolds; in stipple, the Summer and Winter of the Bartolozzi “Season” set, of which Westall did the Spring and Autumn; The Cottage Door and The School Door, by Keating; Setting out to the Fair and The Fairings, by J. Eginton, and the pretty Little Turkey Cock by Delattre, all admirable examples of the kind of art that made Wheatley’s reputation.

The pleasant uninspired rusticities and sentimentalities of Henry Singleton were to popular as to engage the abilities of some of the leading engravers, who must certainly have made the best of them for the colour-printer, since Singleton’s colouring was accounted poor even in his own day. Among the most taking examples we have Nutter’s pretty pair The Farmyard and The Ale-house Door, Burke’s Vicar of the Parish, Eginton’s Ballad-Singer, Knight’s British Plenty and Scarcity in India, some children subjects by Meadows and Benedetti, and E. Scott’s Lingo and Cowslip, which shows that genuinely comic actor, John Edwin, and that audaciously eccentric and adventurous actress, Mrs. Wells, in O’Keefe’s notorious Haymarket farce, “The Agreeable Surprise,” a group which Downman also pictured, though with infinitely more spirit and character.

Subjects dealing with childhood were still greatly in demand, but the public now wanted the children to be more grown-up, and more mundane than the cupids and cherubim of Cipriani, or the Baby Loves and Bacchanals of Lady Diana Beauclerc, so admired by Horace Walpole, and so much flattered by the engravings of Bartolozzi,[24] Tomkins and Bovi. The prolific Richard Westall was not behind his brother Academicians in adapting his inspiration to the market, so, combining rural fancy, as required, with the sentiment of child-life, he made many a parlour look homelier with his pleasant, plausible picturings. When the charm of the engraving glossed over the weaknesses, and colour-printing added its enticing advocacy under Westall’s personal direction, we can find some justification for their popularity in such prints as Nutter’s The Rosebud, The Sensitive Plant, and Cupid Sleeping; Josi’s Innocent Mischief, Innocent Revenge, and Schiavonetti’s The Ghost, a pretty but unequal companion to The Mask of Reynolds.

Although at this productive period of the colour-print William Blake’s “Songs of Innocence” were issued, with their sweetly pictured pages of uniquely printed colour, and their magic simplicity of poetry, every page having “the smell of April” as Swinburne said, it does not appear that they exercised any imaginative influence on the artists who were producing children subjects for the popular prints. Yet certainly poetic sentiment informed the grace and charm which were the characteristics of Thomas Stothard, whose prodigiously industrious and productive pencil dominated in a great measure the book-illustration of the day. Five thousand designs are credited to him, and Blake himself engraved some of these in stipple; but our present concern with Stothard is in such engaging colour-prints as Knight’s Fifth of November, Feeding Chickens, The Dunce Disgraced, The Scholar Rewarded, Coming from School, and Buffet the Bear, Runaway Love, Rosina, Flora, and the popular Sweet Poll of Plymouth, Nutter’s First Bite, and Just Breeched; Strutt’s Nurs’d at Home and Nurs’d Abroad, and others of more adult interest too numerous to mention.

Another popular favourite with the buyers of colour-prints was the Rev. Matthew. William Peters, the only clergyman who ever wore the dignities of the Royal Academy, though, as a matter of fact, it was only after he had attained full academic honours that he took holy orders. Eventually, after some successful years with portraiture and fancy subjects, he resigned his R.A.’ship; but it must be said that while he was painting for popularity there was a good deal of the “world and the flesh” about his pictures, albeit his was a very winsome view of both, to wit, the seductively pretty Sylvia and Lydia, by Dickinson; White’s Love and The Enraptured Youth; John Peter Simon’s Much Ado about Nothing; Hogg’s Sophia, and J. R, Smith’s The Chanters. The Three Holy Children in Simon’s print, however, shows Peters more as we may imagine him in the light of a “converted” Royal Academician—converted to be chaplain to George “Florizel,” Prince of Wales.

[25]

John Russell, whose gracious portraits in pastel appealed to fashion with the special charm of their uncommon medium, also found happy interpretation on the copper-plate, especially from the delicate graver of P. W. Tomkins. The most attractive examples in colours are the charming Maria, Maternal Love (Mrs. Morgan and child), and Children Feeding Chickens. Collyer’s Mrs. Fitzherbert is also one of the most desirable among the numerous Russell colour-prints. When the engravings of Charles Ansell’s Death of a Racehorse in 1784 had an immense sale, none presumably would have believed that, a hundred and twenty-five years later, collectors would hold him in high regard, not for the horses that made him famous, but for four dainty little drawings of domestic “interiors,” thoroughly representative of their period, preserved in P. W. Tomkins’s stipple prints, especially charming and rare in colours. Tomkins engraved other things of Ansell’s, Knight also; but the set of The English Fireside and The French Fireside, The English Dressing-Room and The French Dressing-Room (the two latter reproduced here), if really fine in colour, must be a prize in the choicest collection. As these prints give us intimate glimpses into the home-life of the “smart set” of the period, so, thanks to the pictorial sense of that vivacious artist Edward Dayes, we are able to see just how the fashionable world comported itself in the parks. An Airing in Hyde Park and The Promenade in St. James’s Park, the one engraved by Gaugain, the other by Soiron, are alive with contemporary social and pictorial interest, and in colours they are rare to seek. Social interest, too, flavours chiefly the name of Henry William Bunbury. Classed generally with the caricaturists, among whom, even in that period of forcible and unrestricted caricature, he was certainly one of the most spontaneously humorous as he was the most refined, he had, like his brother caricaturist Thomas Rowlandson, his days of grace. In those days he did, not with flawless drawing perhaps, but with a vivid feeling for beauty, some charming things, which the engravers turned to good account in colour. Among these are Morning Employments by Tomkins, The Song and The Dance by Bartolozzi, The Modern Graces by Scott, and Black-eyed Susan by Dickinson.

From his popular task of whipping with genial graphic satire the social follies and foibles of the day. Bunbury’s pencil would on occasion “lightly turn to thoughts of love,” as in A Tale of Love, so artistically engraved by J. K. Sherwin; and it was in this mood that his discourse on love and romance would somewhat shock Fanny Burney. She did not think it quite nice in a Court equerry, who was also a husband and a father, to dilate so rhapsodically on such topics; but he adored “The Sorrows of Werther,” which she told him she could not read; and, after all, was he not the devoted husband of[26] Catherine Horneck, Goldsmiths “Little Comedy”? Rowlandson had not, of course, Bunbury’s culture and refinement, but with all his rollicking Rabelaisian humour, he had faultless draughtsmanship with, when he chose, a daintiness of touch and a magic grace of curve. Among his countless coloured plates, however, those that can be accepted as true colour-prints can be numbered almost on one hand. Opera Boxes and the interesting and vivid Vauxhall, spiritedly engraved by Pollard, and capitally aquatinted by Francis Jukes, were not, as generally supposed, actually printed in colours; but The Syrens and Narcissa, both things of voluptuous charm, are etched and stippled and veritably colour-printed in part. With very few exceptions, Rowlandson’s prints were only etched by him, then aquatinted and coloured by other hands, he supplying a tinted drawing.

When the mantle of the fashionable portrait-painter had slipped naturally from the shoulders of Reynolds to those of John Hoppner, and the older beauties were not as young as they used to be, and a new set of beautiful young women had meanwhile grown up, the curious public called for the new faces. So Hoppner, already finely interpreted by the best mezzotint men, now readily allied himself with Charles Wilkin, a portrait-painter in oil and miniature of some repute, who, as a very talented and individual stipple-engraver, had won his spurs with Sir Joshua, notably in his rich engraving of the famous Lady Cockburn and her Children. The new venture was A Select Series of Portraits of Ladies of Rank and Fashion. These, charming and desirable in monochrome, are delightful, but very rare, in colour. Seven of the portraits were done by Hoppner, and show him in most gracious vein: these are Viscountesses St. Asaph and Andover, Countess of Euston, the new Duchess of Rutland, Lady Charlotte Campbell, Lady Langham, and Lady Charlotte Duncombe. The other three are from the spirited pencil of the engraver himself—Ladies Gertrude Villiers, Catherine Howard and Gertrude Fitzpatrick, who as a child had sat to Reynolds for his Collina. Hoppner’s Hon. Mrs. Paget as Psyche is also a charming coloured stipple, engraved by Henry Meyer. The colour-printed mezzotint seems to have found exceptional favour with Hoppner, for in that medium we have the lovely Countess of Oxford—a choice example—and Mrs. Whitbread, by S. W. Reynolds; J. R. Smith’s Sophia Western and Mrs. Bouverie, with an engaging suggestion of pastel; Charles Turner’s Lady Cholmondeley and Child; John Jones’s Mrs. Jordan as “Hippolyta”; John Young’s Lady Charlotte Greville, Mrs. Hoppner as “Eliza,” Mrs. Orby Hunter, the Godsall children (The Setting Sun), and Lady Lambton and Children (one of them Lawrence’s Master Lambton); William Ward’s pretty Salad Girl, Mrs. Benwell, and The Daughters[27] of Sir Thomas Franklana, so well known in monochrome, but so exceedingly rare in colour; James Ward’s Juvenile Retirement (the Douglas children); Children Bathing (Hoppner’s own); Mrs. Hibbert, and the graceful Miranda (Mrs. Michael Angelo Taylor), of which only one impression is known in colours, exquisite in quality, that in the very choice collection of Mr. Frederick Behrens.