Large-size versions of illustrations are available by clicking on them.

PEOPLE OF THE VEIL

![[Decoration]](images/logo.png)

MACMILLAN AND CO.,

Limited

LONDON . BOMBAY . CALCUTTA . MADRAS

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK . BOSTON . CHICAGO

DALLAS . SAN FRANCISCO

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd.

TORONTO

PEOPLE OF THE VEIL

Being an Account of the Habits,

Organisation

and History of the Wandering Tuareg Tribes

which inhabit the Mountains of Air or Asben

in the Central Sahara

BY

FRANCIS RENNELL RODD

ⵍⵆⵔⵗⵙ

“NAUGHT BUT GOOD”

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED

ST. MARTIN’S STREET, LONDON

1926

COPYRIGHT

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN

[v]PREFACE

This book was originally intended to be an account of the people and mountains of Air in the Central Sahara, where I made a journey during most of 1922 with Angus Buchanan and T. A. Glover. The former had visited the area on a previous occasion and had described the people and places he had seen in his book, Out of the World—North of Nigeria. It therefore seemed more profitable to inquire into some of the problems surrounding the inhabitants of the Sahara whom we encountered, and thus deal with Air and its Tuareg population rather less objectively than had my fellow-traveller. In the course of the succeeding years, as I became more and more immersed in considering various scientific aspects of the Sahara, I came to the conclusion that neither had the Tuareg people nor had this vast area of the earth’s surface been at all adequately examined. Most studies had been objective and, as is unhappily the case with this book, confined to one area. A comprehensive account of the history and ethnology of the Sahara still requires to be written.

As a consequence of these investigations, the present work assumed a form for which one journey of nine months in the countries concerned scarcely seems enough justification. That the book was not completed sooner has been due to the impossibility of spending any time continuously either in research or on writing during the three years which have elapsed since I returned. The fact that this book has been the occupation only of such spare time as I have had available accounts for its many conscious deficiencies, which are unfortunately not the more excusable[vi] in a volume of the type which it purports to be. If I can feel that it will have served to stimulate the curiosity of students or have assisted them to find their way about the literature on the subject, I shall consider that as a reward calculated to enhance the pleasure which I have derived from writing and reading about this—to me—fascinating topic.

It will be one of my lasting regrets that I was unable to complete with Angus Buchanan his journey across the Sahara from Nigeria to Algiers. The delays which we encountered in Air obliged me to return to resume my duties in that branch of H.M.’s Service in which I was then serving. This is not the place to mention the many things which I owe to Angus Buchanan; perhaps the greatest advantage I derived was the promise we gave one another to travel again together if an occasion should come to him and leisure from another profession to me, whereby we might be enabled to renew our companionship of the road. I am grateful to him for permission to use several of his photographs in the present volume as well as certain information which he collected when we were separately engaged on our different work.

To T. A. Glover, the Cinematographer, whose services Angus Buchanan secured to accompany him, I owe many pleasant memories of days spent together and his excellent advice in taking most of the photographs which are included in this book.

The French officers whom I encountered in the course of my wanderings were as charming and as friendly as perhaps, of all foreign nations, only Frenchmen know how to be. Were the relations between our respective countries always even remotely similar to those which subsisted between us, there would be no room for the suspicion and pettiness which so often mar diplomatic and political intercourse. The mutual confidence in which we lived is illustrated by two events.

On a certain occasion in Air when news was received[vii] of a raid being about to fall on the country, I was honoured by receiving a communication from the French officer commanding the Fort at Agades, indicating the locality in his general scheme of defence whither I might lead on a reconnaissance an armed band of local Tuareg from the village in which I was then living by myself. On another occasion, after travelling for some hundreds of miles with a French Camel Corps patrol, the men were paraded and in their presence I was nominated an honorary serjeant of the “Peloton Méhariste de Guré,” a type of compliment which those associated with the French Army will best realise. It is to the officer commanding this unit, Henri Gramain of the French Colonial Army, that I owe the most perfect companionship I have ever had the fortune to experience. I know that when we meet again we shall resume conversation where we left off at Teshkar in the bushland of Elakkos, one evening in the summer of 1922. He and my other friends, Tuareg, British, French, Arab and Fulani contributed to make that year the happiest I have ever spent.

No reader of the works of that great traveller, Dr. Heinrich Barth, will need to be told how much of the data collected in the succeeding pages has been culled from the monumental account of his Travels in Central Africa. This German, who most loyally served the British Crown in those far countries, is perhaps the greatest traveller there has ever been in Africa. His exploits were never advertised, so his fame has not been suffered to compete with the more sensational and journalistic enterprises accomplished since his day down to modern times. But no student will require to have his praises sung by any disciple.

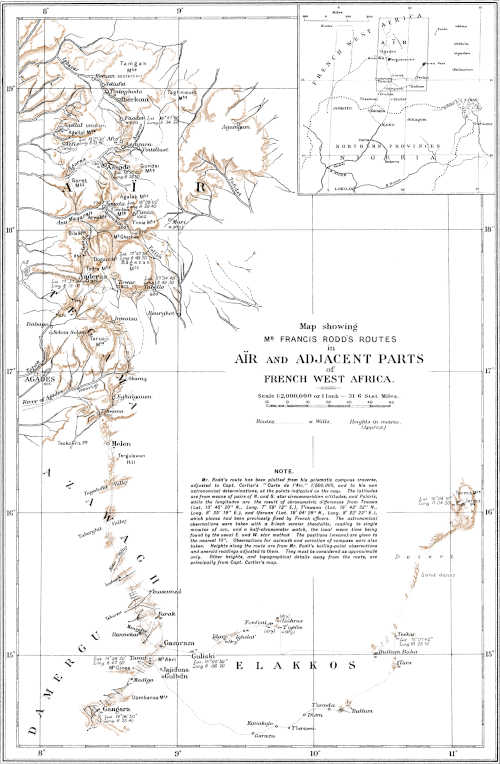

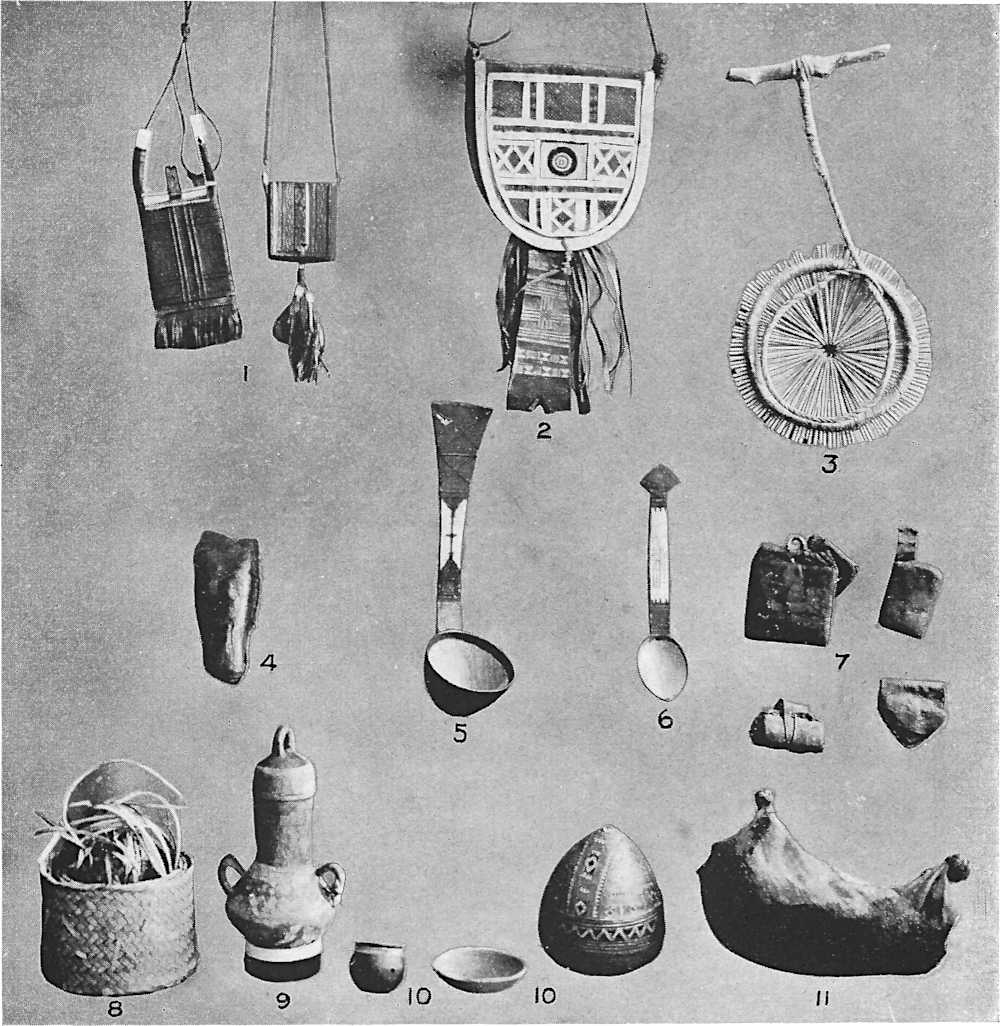

I have to thank the Royal Geographical Society for permission to use the map which was prepared for a paper I had the honour to read in 1923 before a meeting of the Fellows. More especially do I wish to thank E. A. Reeves, their Keeper of Maps, both for the instruction in surveying[viii] which he gave me before my journey and for the assistance afforded after my return in checking and working up my results. My cartographic material in the form of road traverses, sketch maps based on astronomical positions, and theodolite computations are all in the Society’s library and available to students. A small collection of ethnographic material which I brought back is at Oxford in the Pitt Rivers Museum, to whose Curator, Henry Balfour, I am indebted both for advice and for plates Nos. 24-26, 37 and 42.

H. R. Palmer, now H.M. Lieutenant-Governor of Northern Nigeria, and Messrs. Macmillan & Co. have given me permission to use a table of the Kings of Agades incorporated as Appendix VI. The list originally appeared in extenso, with the names somewhat differently spelled, in an article which he published in the Journal of the African Society in July 1910. The great learning and sympathetic help which he was good enough to put at my disposal have made me, in common with many others in Nigeria, in whose friendship my journey so richly rewarded me, hope that he may be induced to render more accessible to the public the immense fund of historical and other material which he has accumulated during his long career as a distinguished Colonial servant.

The then Governor of Nigeria, Sir H. Clifford, and the French Ministry of Colonies earned the gratitude of Angus Buchanan and myself by their assistance on the road and in facilitating our journey.

My brother-in-law, T. A. Emmet, was good enough to execute several drawings from rough sketches I had made on the spot. Two of these drawings are reproduced as plates Nos. 38 and 39.

To three persons it is difficult for me to express my gratitude at all suitably. D. G. Hogarth read my manuscript and offered his invaluable advice regarding the final form of the book as it now appears. Many years’ association with him has led others beside myself to regard him in his wisdom as our spiritual godfather in things[ix] appertaining to the world of Islam. My father devoted many days and nights to correcting the final draft and proofs of this book. My brother Peter, when his versatile mind perceived certain improvements, rewrote Chapter XII after I had become so tired of the sight of my manuscript that I was on the verge of destroying the offensive object. I owe more to both these two than I can explain.

F. R. R.

New York,

31st December, 1925.

[xi]CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Introductory | 1 |

| II. | The Southlands | 36 |

| III. | The City of Agades | 80 |

| IV. | The Organisation of the Air Tuareg | 119 |

| V. | Social Conditions | 154 |

| VI. | The Mode of Life of the Nomads | 183 |

| VII. | Trade and Occupations | 213 |

| VIII. | Architecture and Art | 238 |

| IX. | Religion and Beliefs | 273 |

| X. | Northern Air and the Kel Owi | 298 |

| XI. | The Ancestry of the Tuareg of Air | 330 |

| XII. | The History of Air. Part I. The Migrations of the Tuareg to Air | 360 |

| XIII. | The History of Air. Part II. The Vicissitudes of the Tuareg in Air | 401 |

| XIV. | Valedictory | 417 |

| APPENDIX | PAGE | |

| I. | A List of the Astronomically Determined Points in Air | 422 |

| II. | The Tribal Organisation of the Tuareg of Air | 426 |

| III. | Elakkos and Termit | 442 |

| IV. | Ibn Batutah’s Journey | 452 |

| V. | On the Root “MZGh” in Various Libyan Names | 457 |

| VI. | The Kings of the Tuareg of Air | 463 |

| VII. | Some Bibliographical Material used in this Book | 466 |

| Index | 469 |

[xiii]PLATES

| PLATE | Facing page | ||||

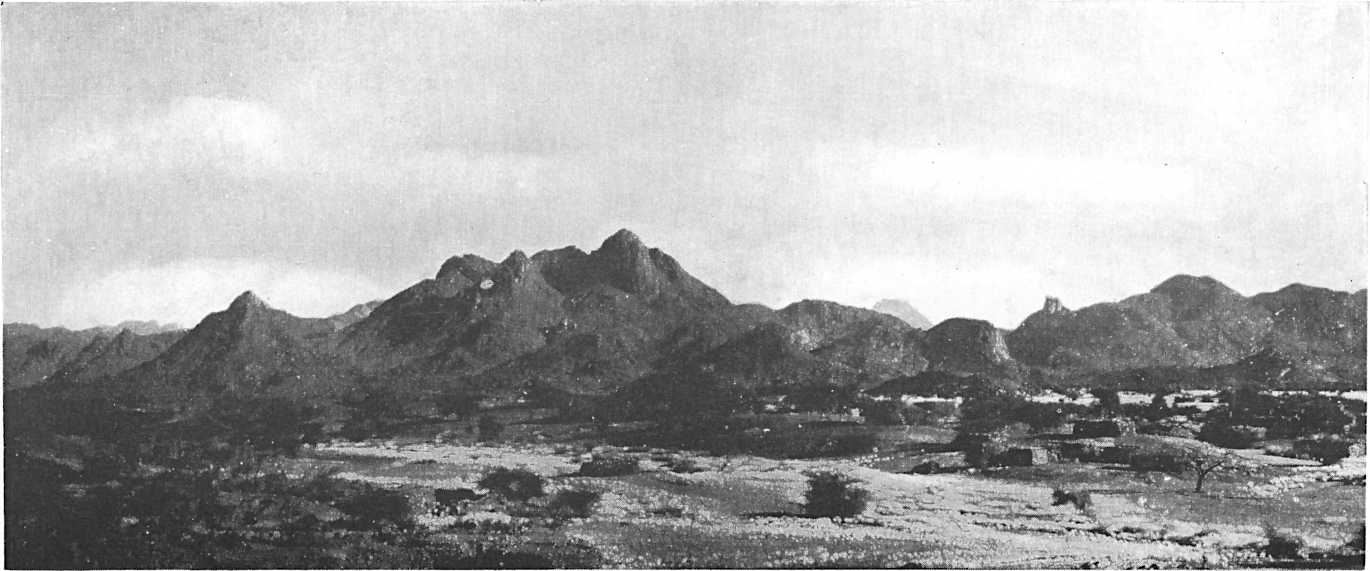

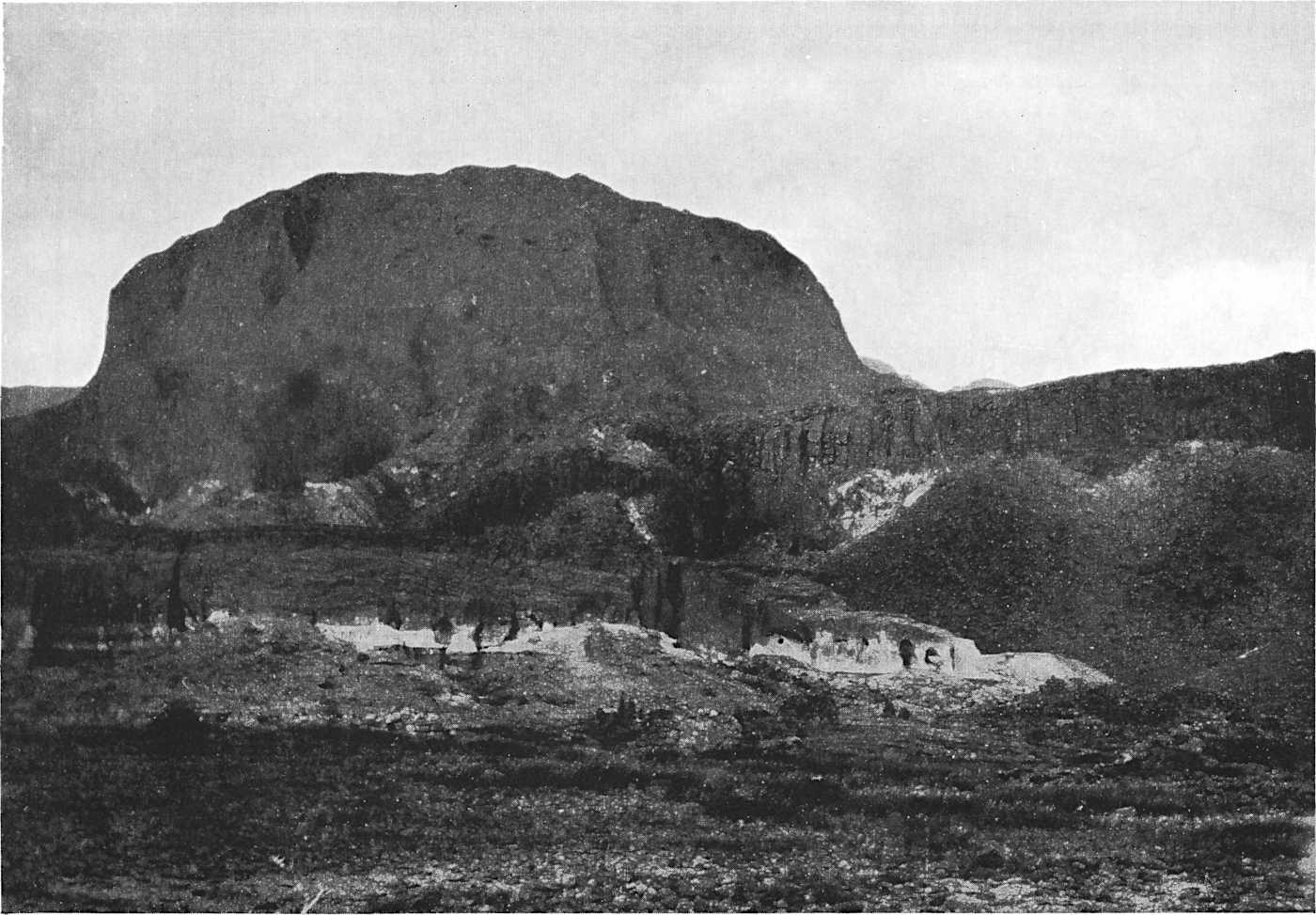

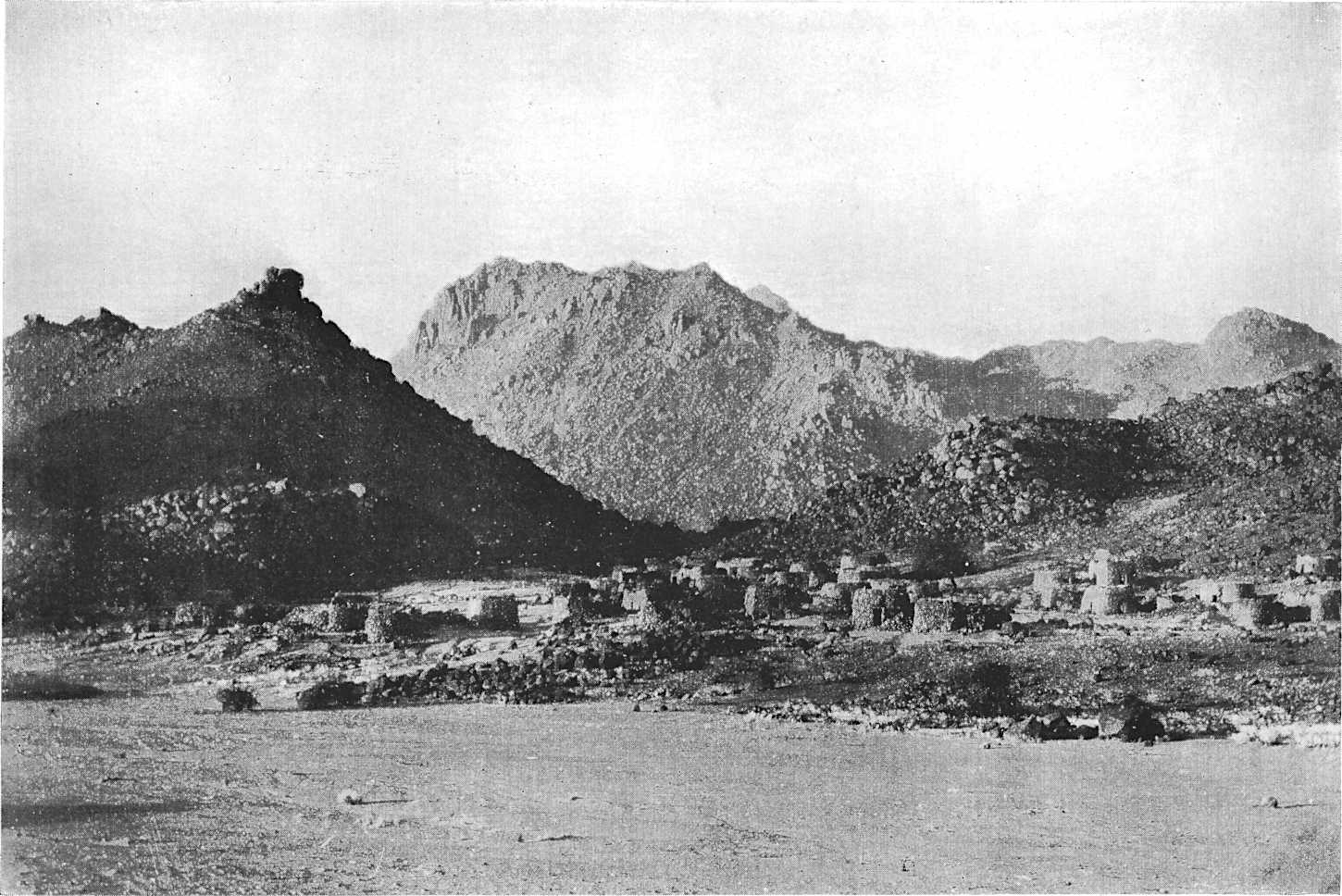

| 1. | Agellal Village and Mountains | Frontispiece | |||

| 2. | Elattu | 14 | |||

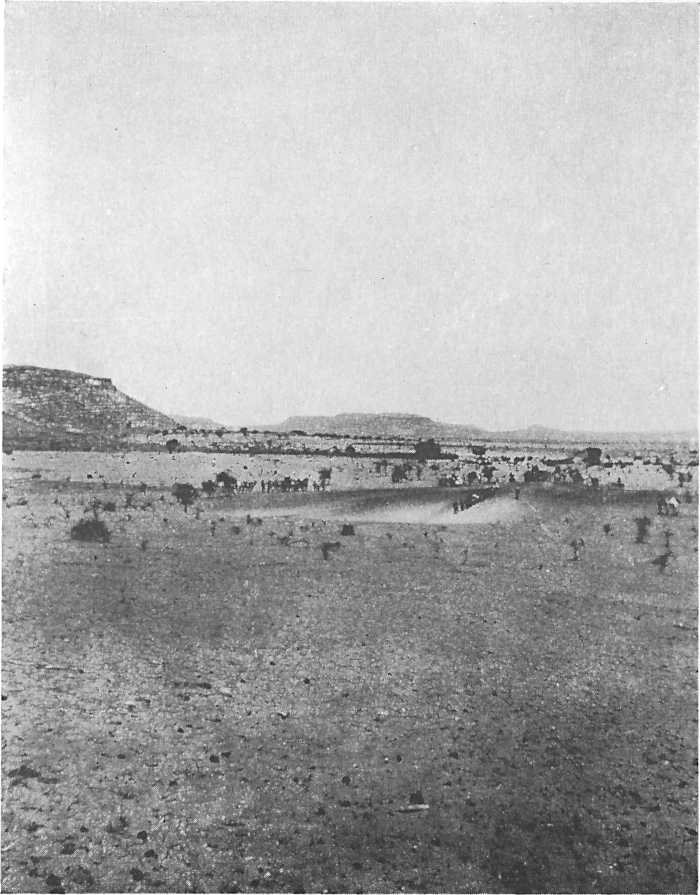

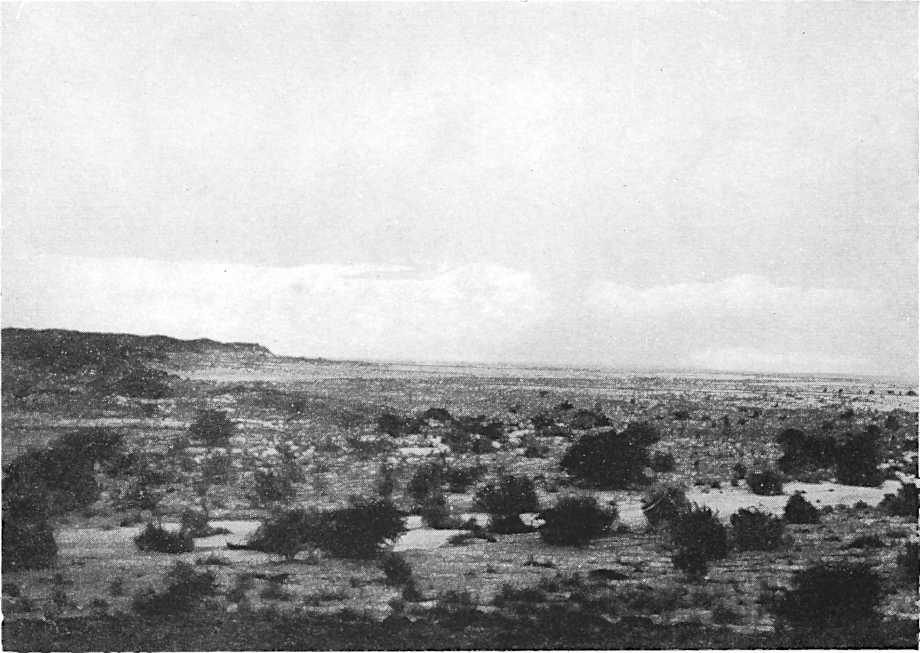

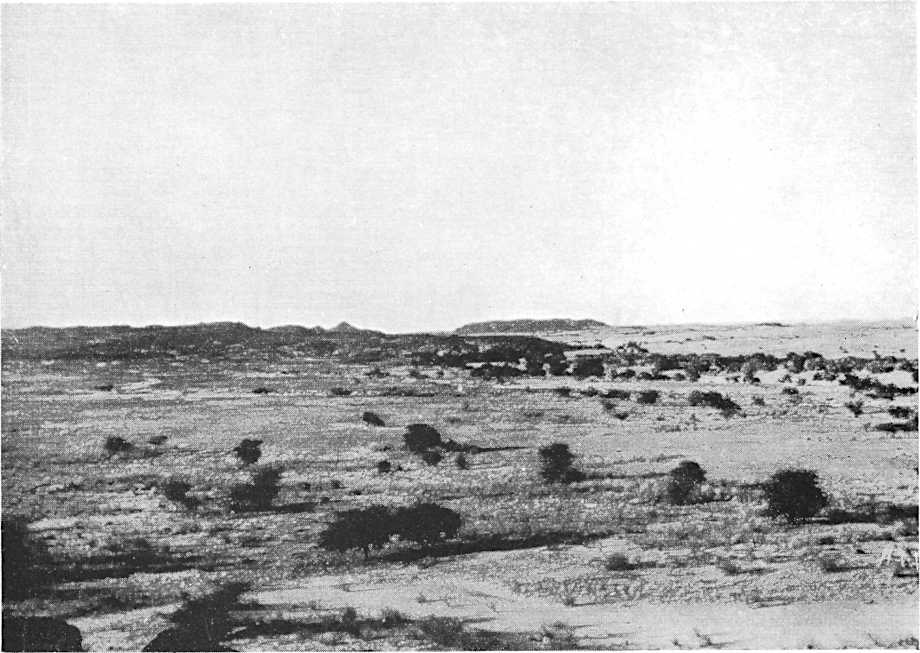

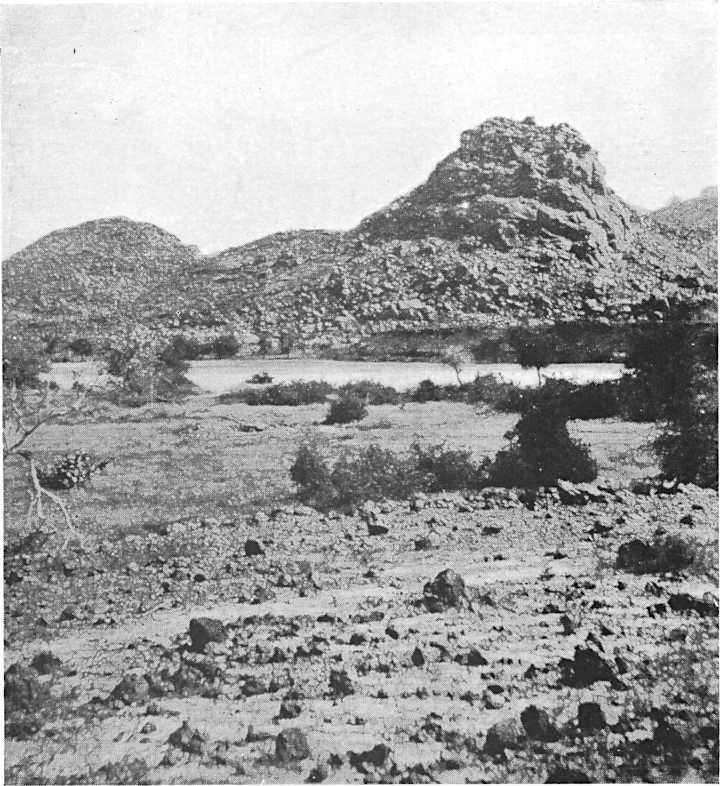

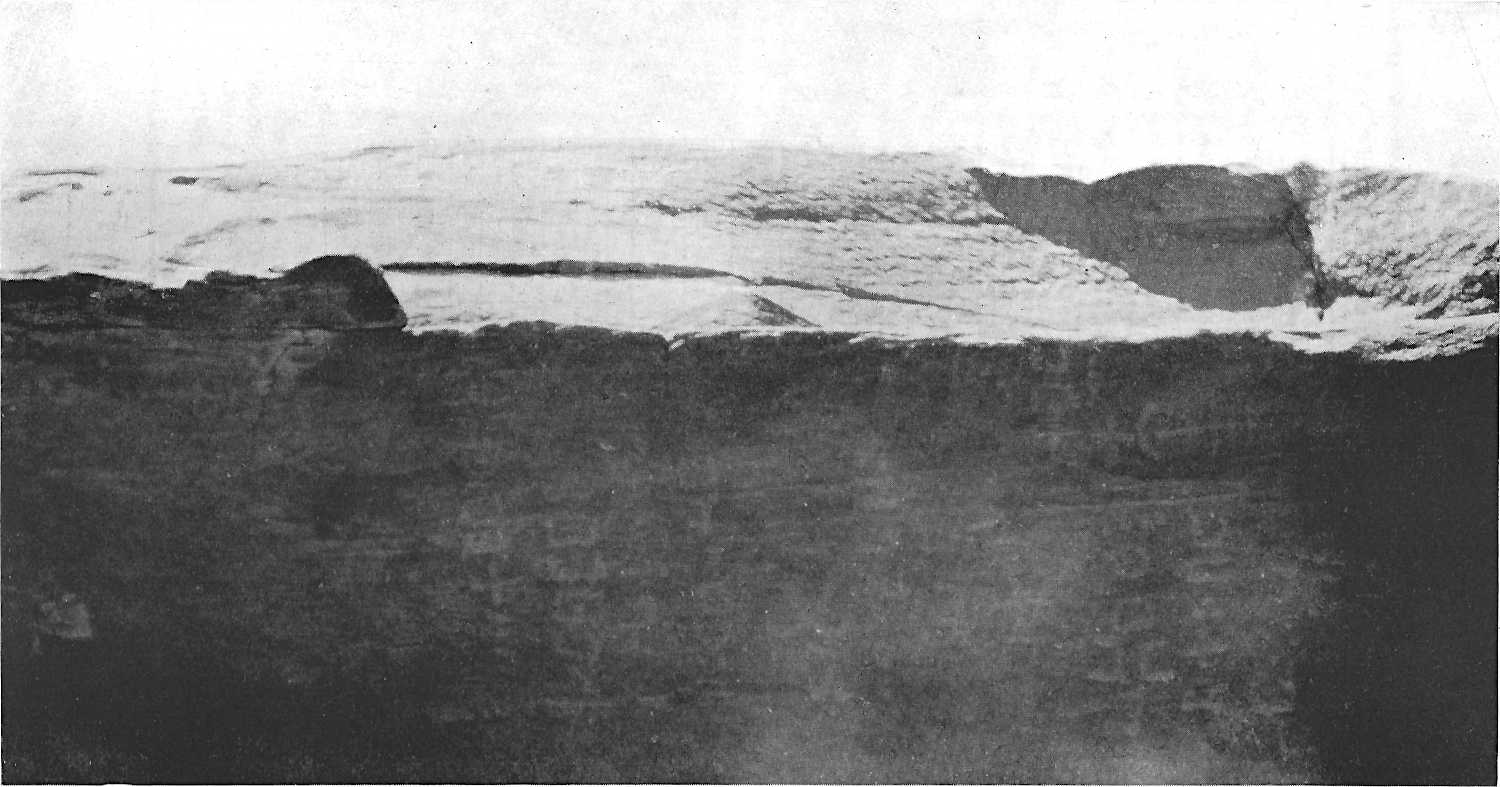

| 3. | Desert and Hills from Termit Peak | 32 | |||

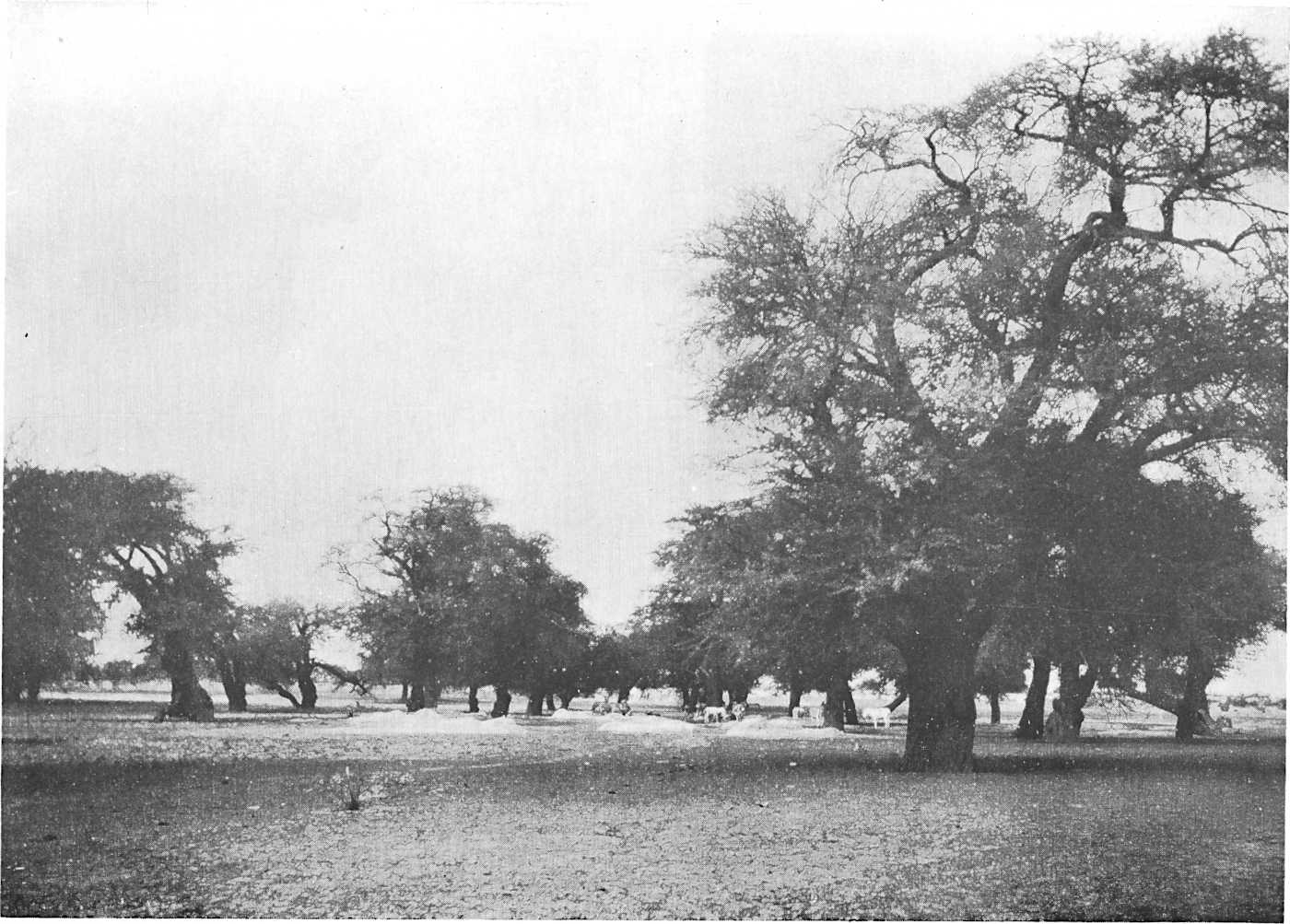

| 4. | Diom in Elakkos | 42 | |||

| Punch and Judy Show | 42 | ||||

| 5. | Gamram | 49 | |||

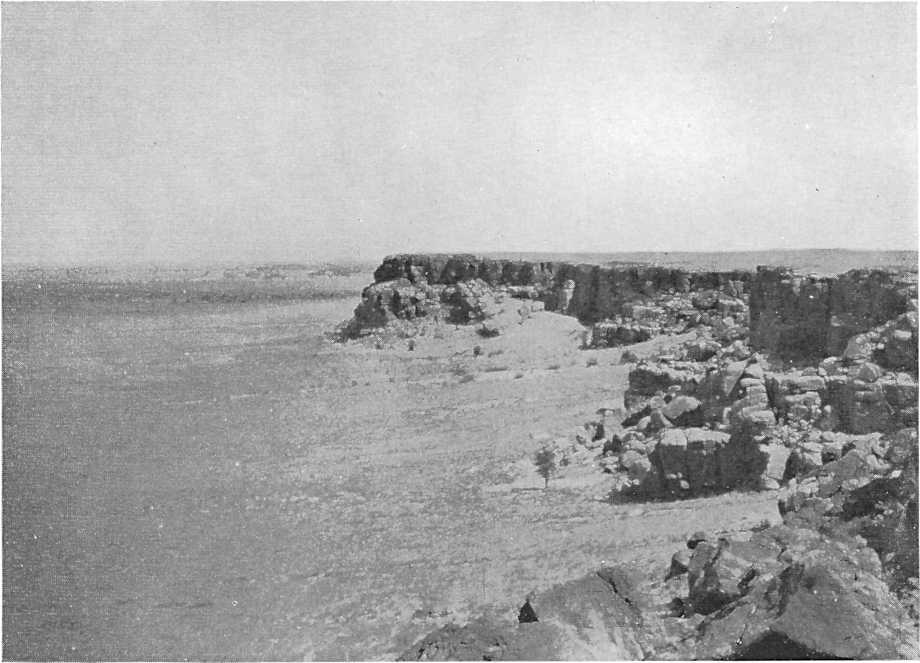

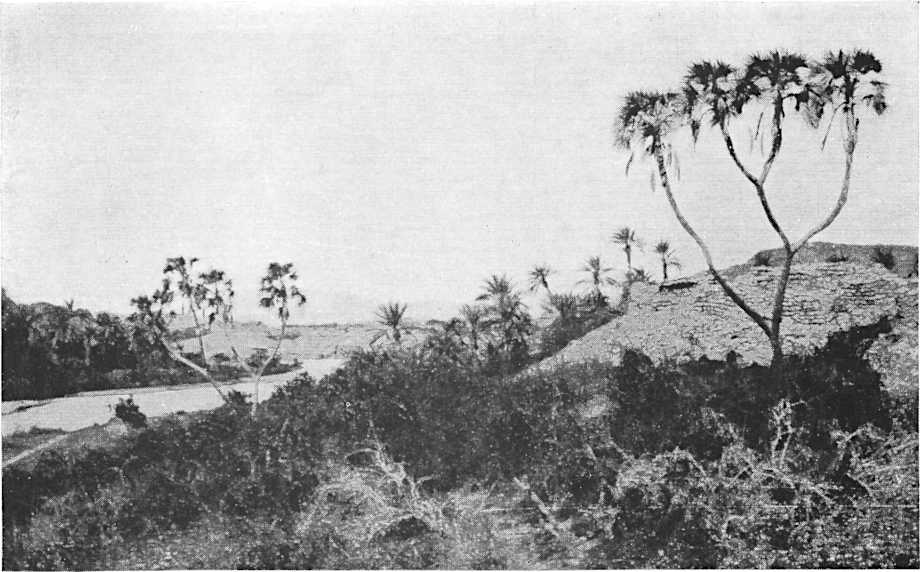

| 6. | River of Agades: Cliffs at Akaraq | 76 | |||

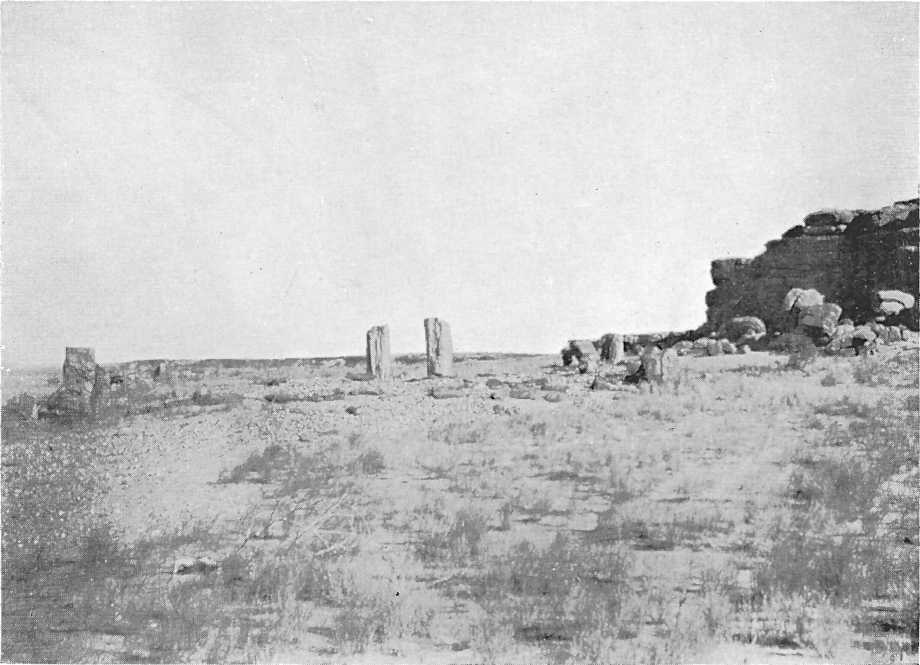

| Shrine at Akaraq | 76 | ||||

| 7. | River of Agades looking South from Tebehic in the Eghalgawen Massif | 79 | |||

| Eghalgawen Massif from Azawagh | 79 | ||||

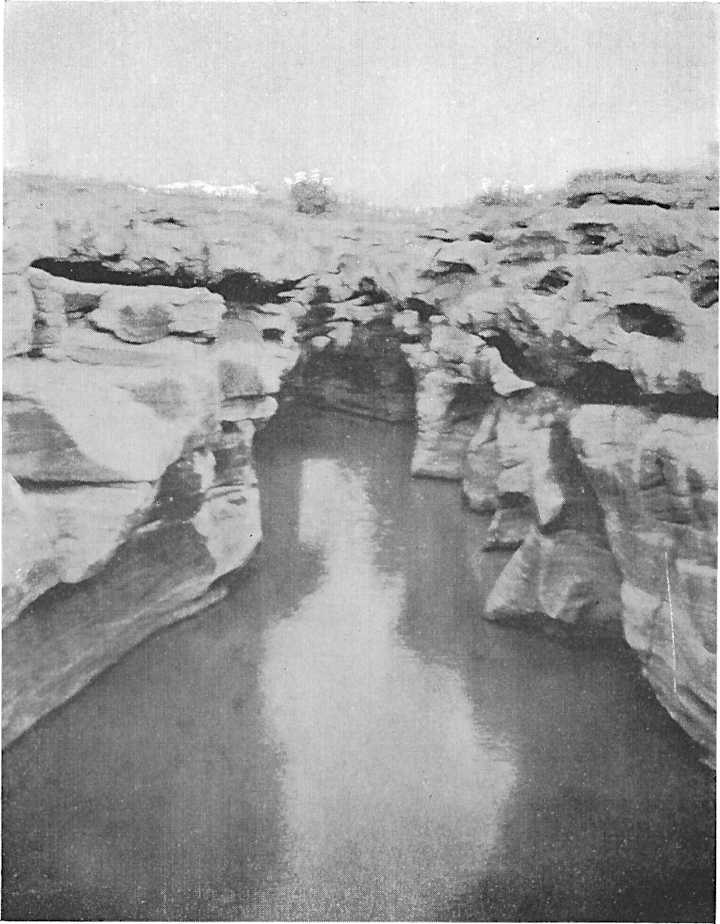

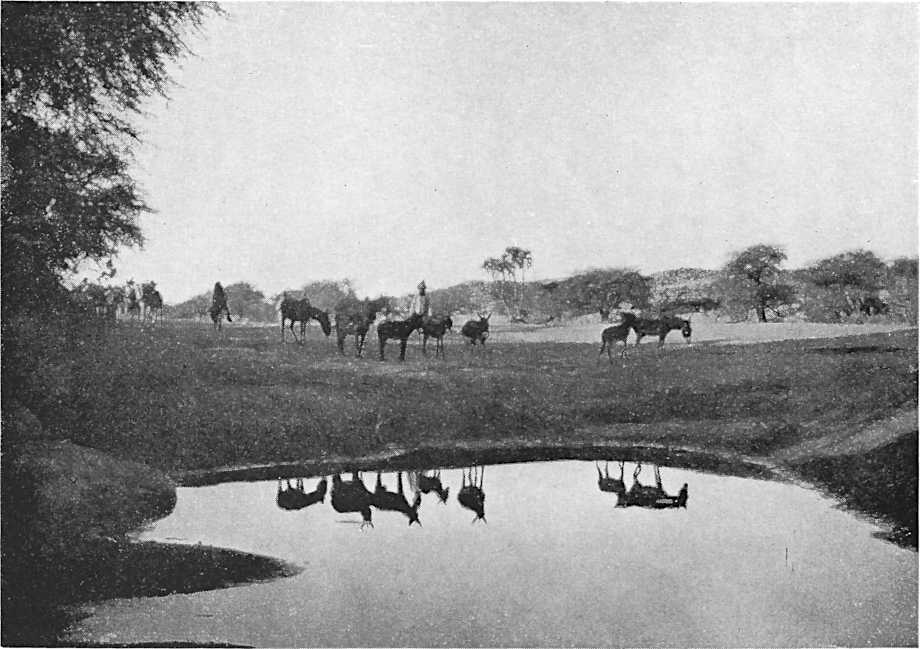

| 8. | Tin Wana Pool | 83 | |||

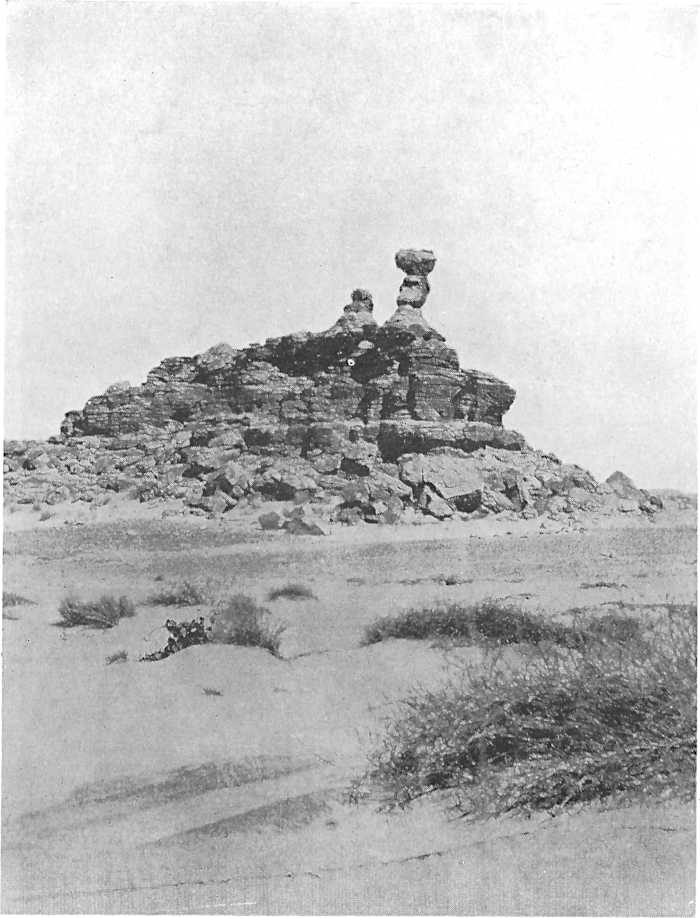

| Rock of the Two Slaves, at the Junction of the Tin Wana and Eghalgawen Valleys | 83 | ||||

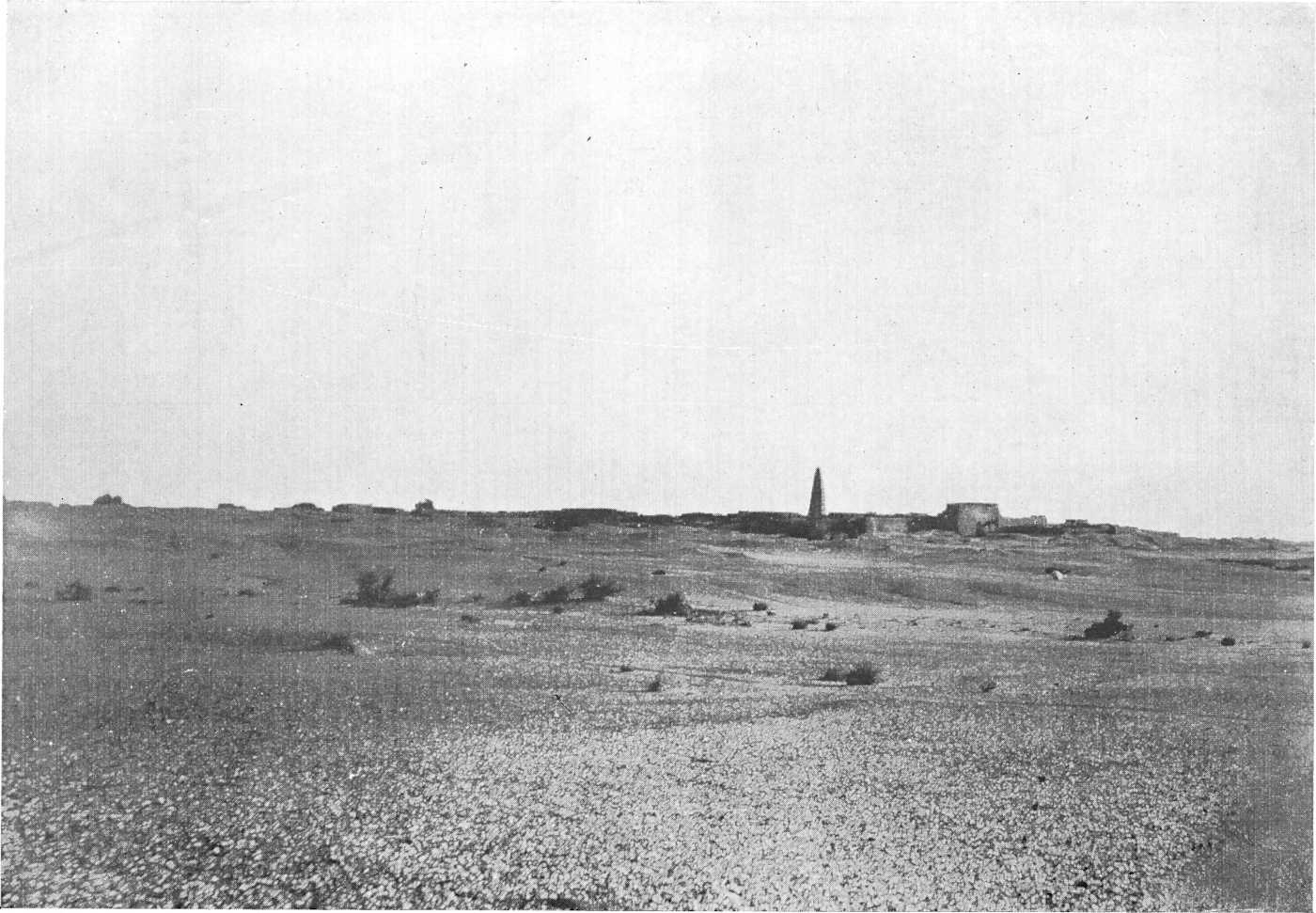

| 9. | Agades | 86 | |||

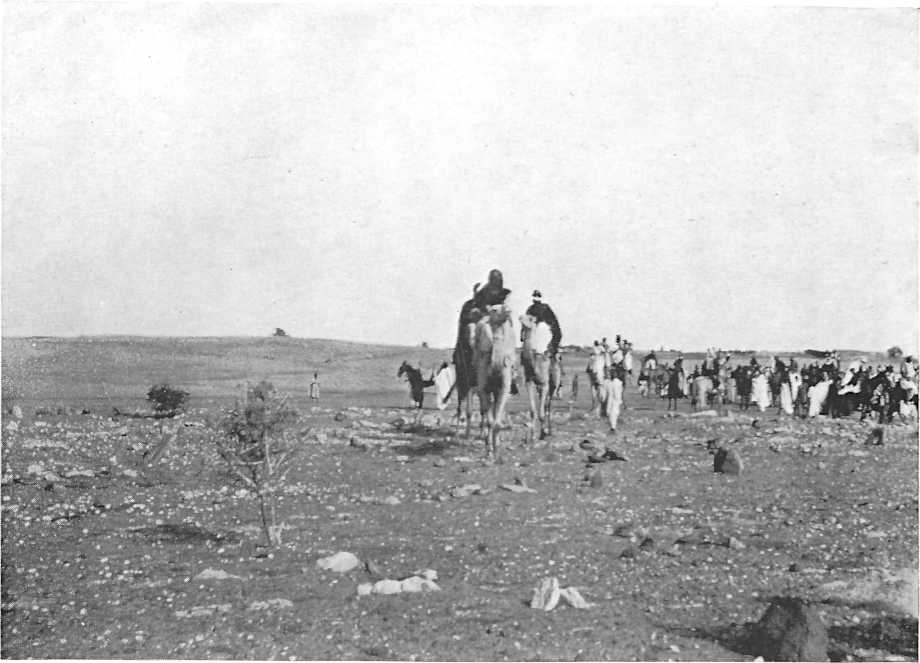

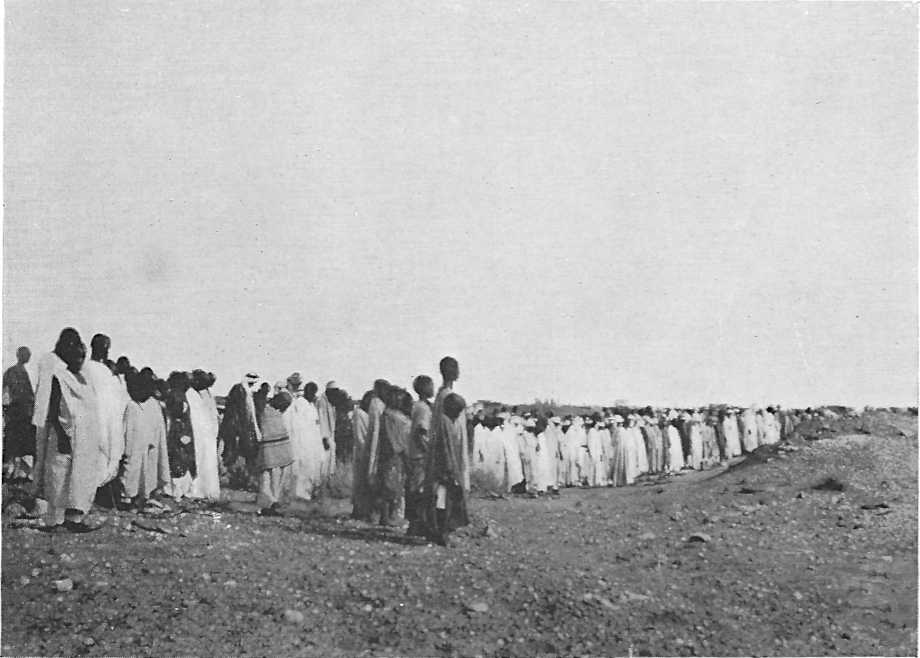

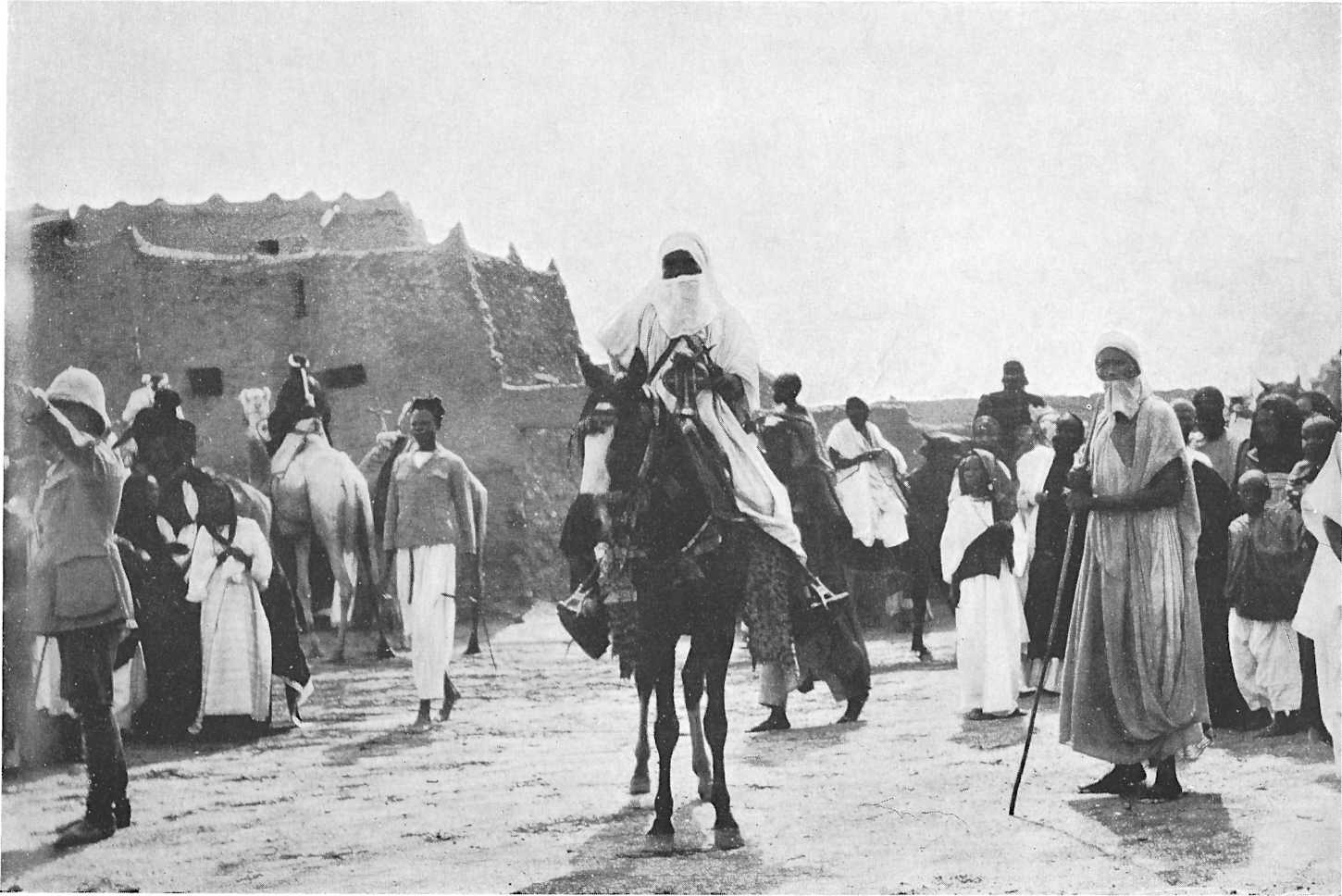

| 10. | Gathering at Sidi Hamada | 95 | |||

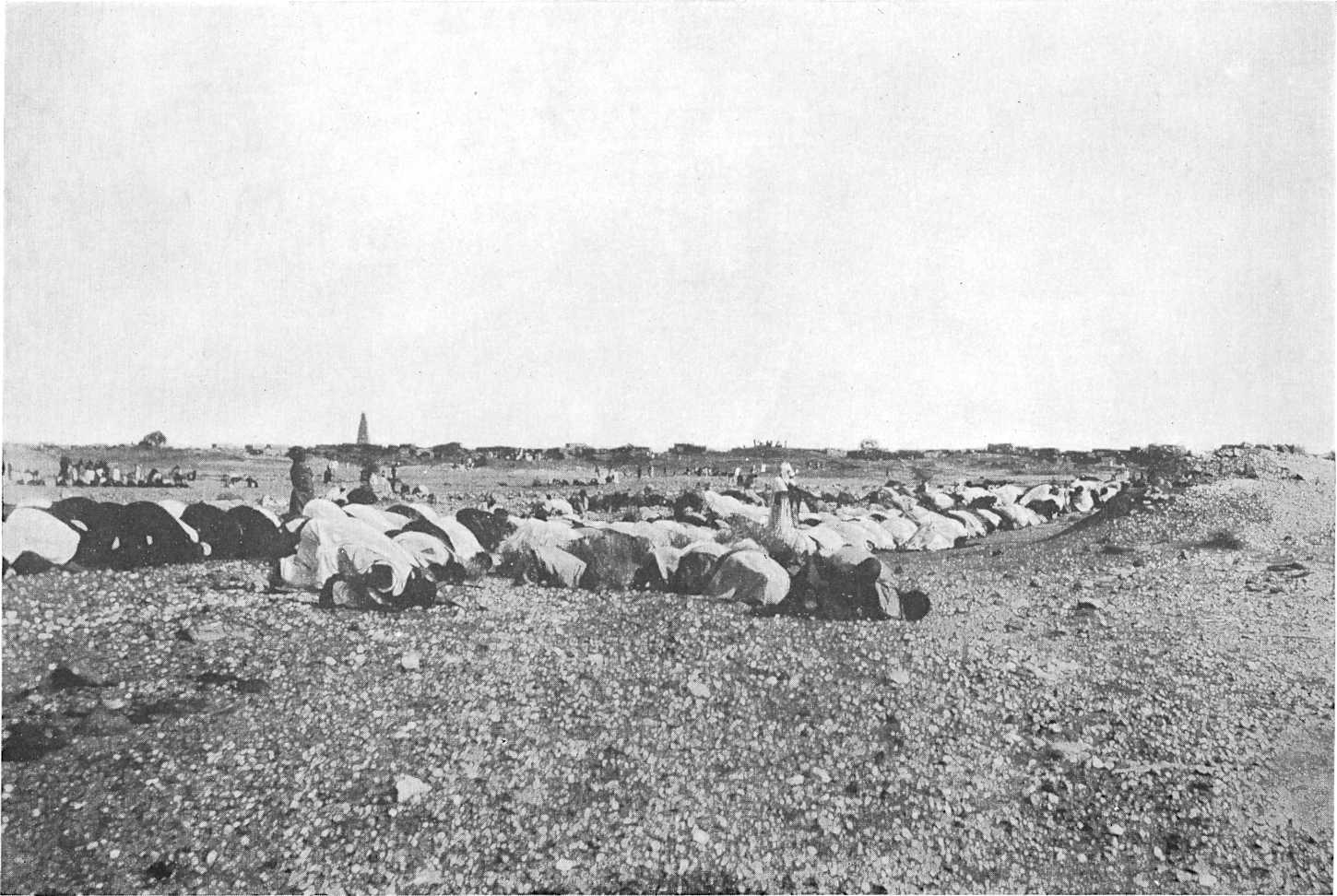

| Prayers at Sidi Hamada | 95 | ||||

| 11. | Prayers at Sidi Hamada | 97 | |||

| 12. | Omar: Amenokal of Air | 108 | |||

| 13. | Auderas Valley looking West | 120 | |||

| Auderas Valley: Aerwan Tidrak | 120 | ||||

| 14. | Mt. Todra from Auderas | 126 | |||

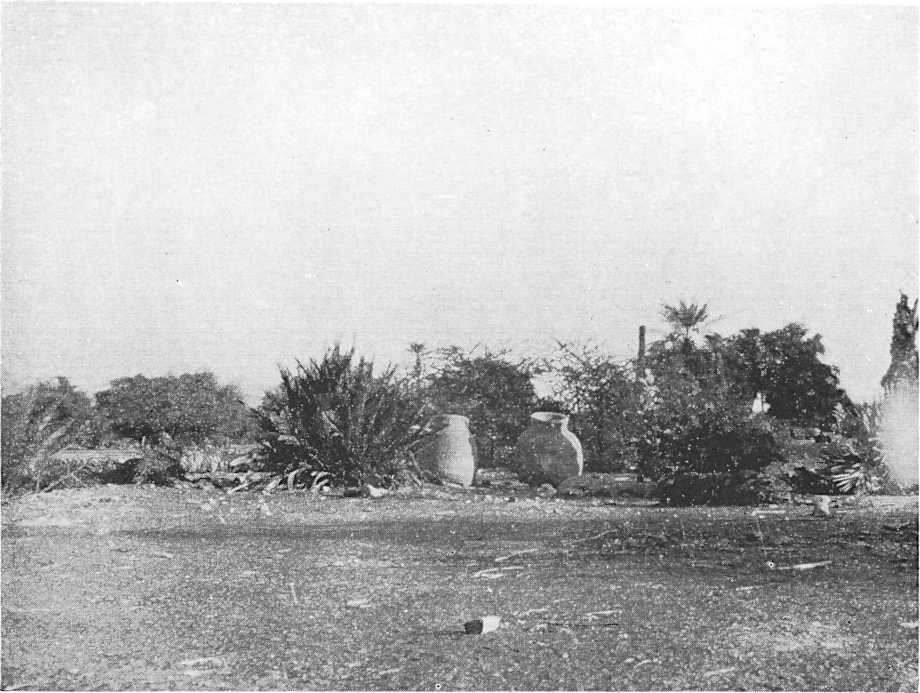

| 15. | Grain Pots, Iferuan | 133 | |||

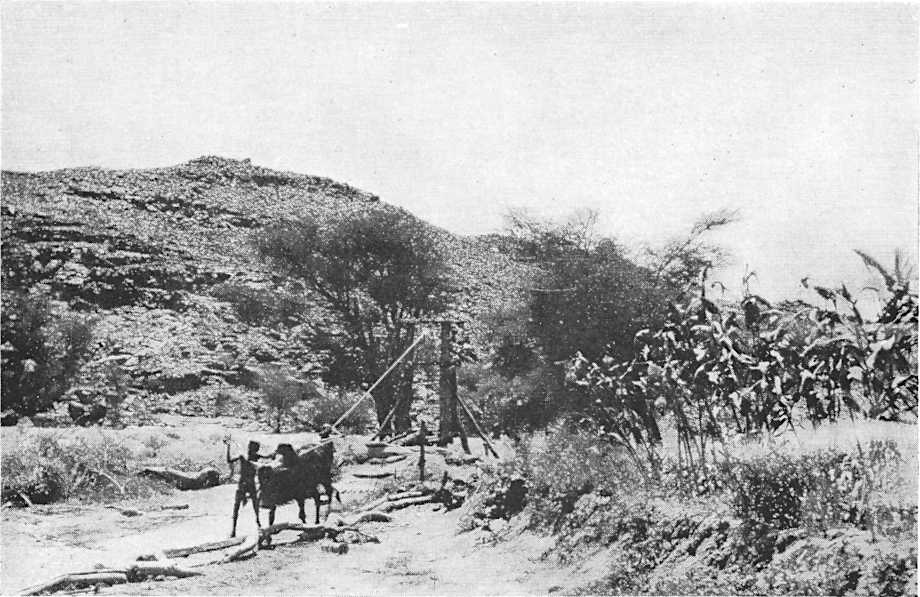

| Garden Wells | 133 | ||||

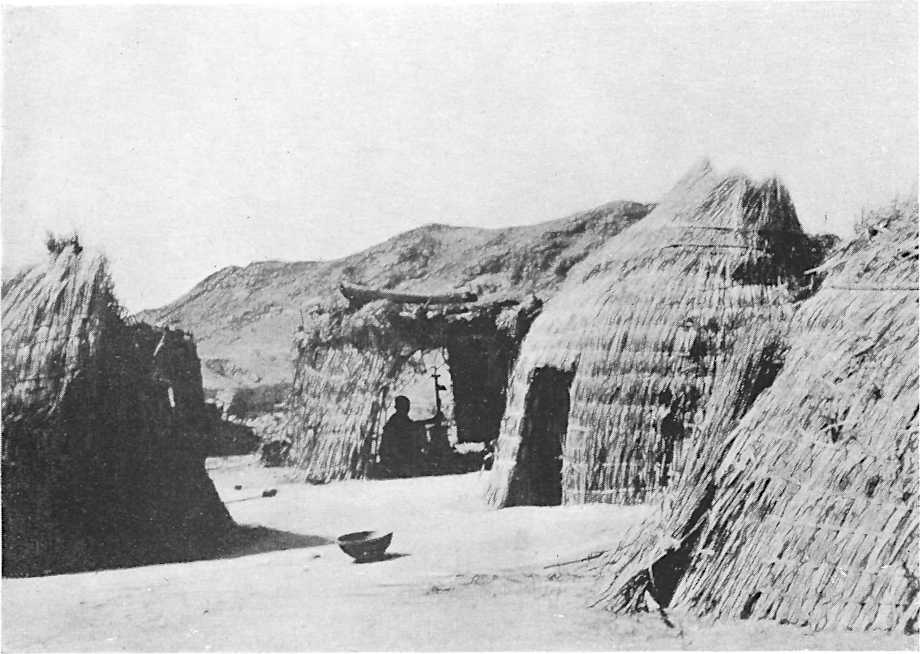

| 16. | Auderas: Huts | 154 | |||

| Auderas: Tent-hut and Shelter | 154 | ||||

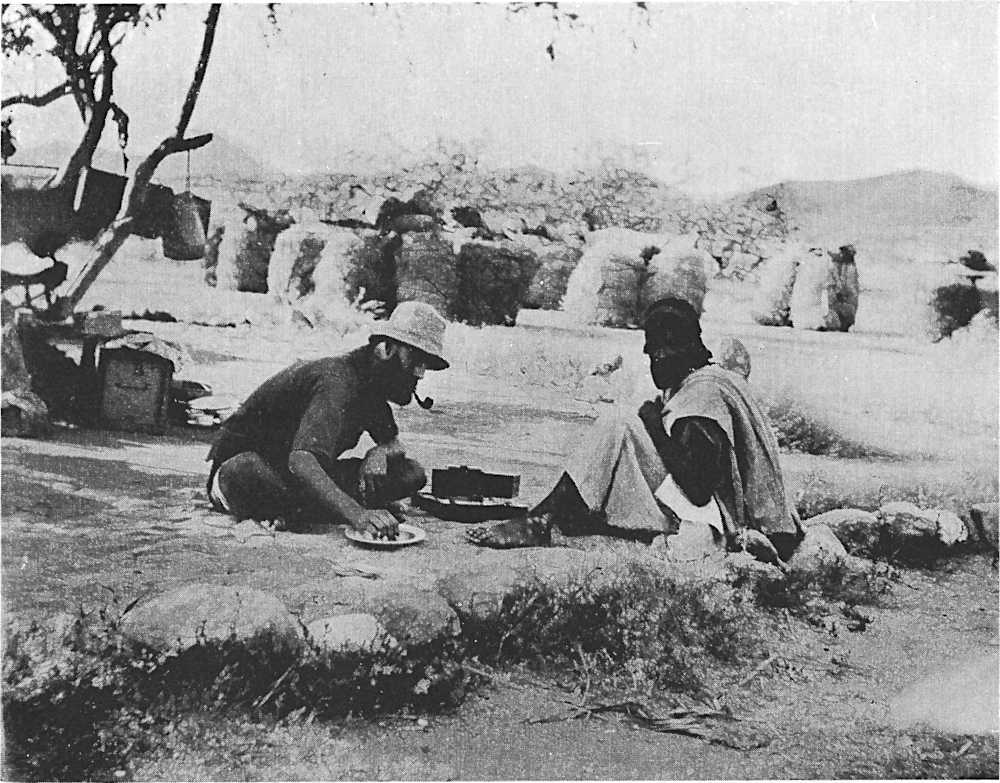

| 17. | The Author dressing a Wound at Auderas | 163 | |||

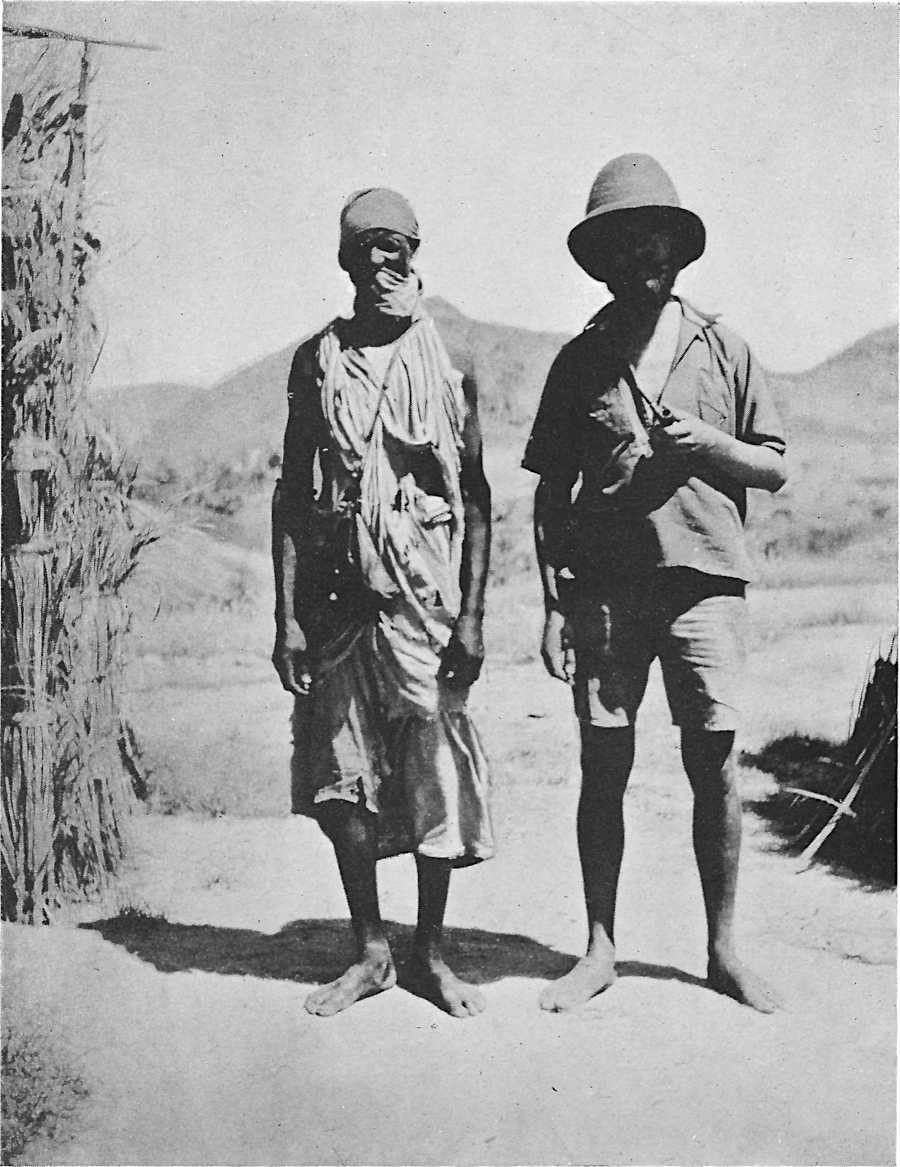

| 18. | Tekhmedin and the Author | 178 | |||

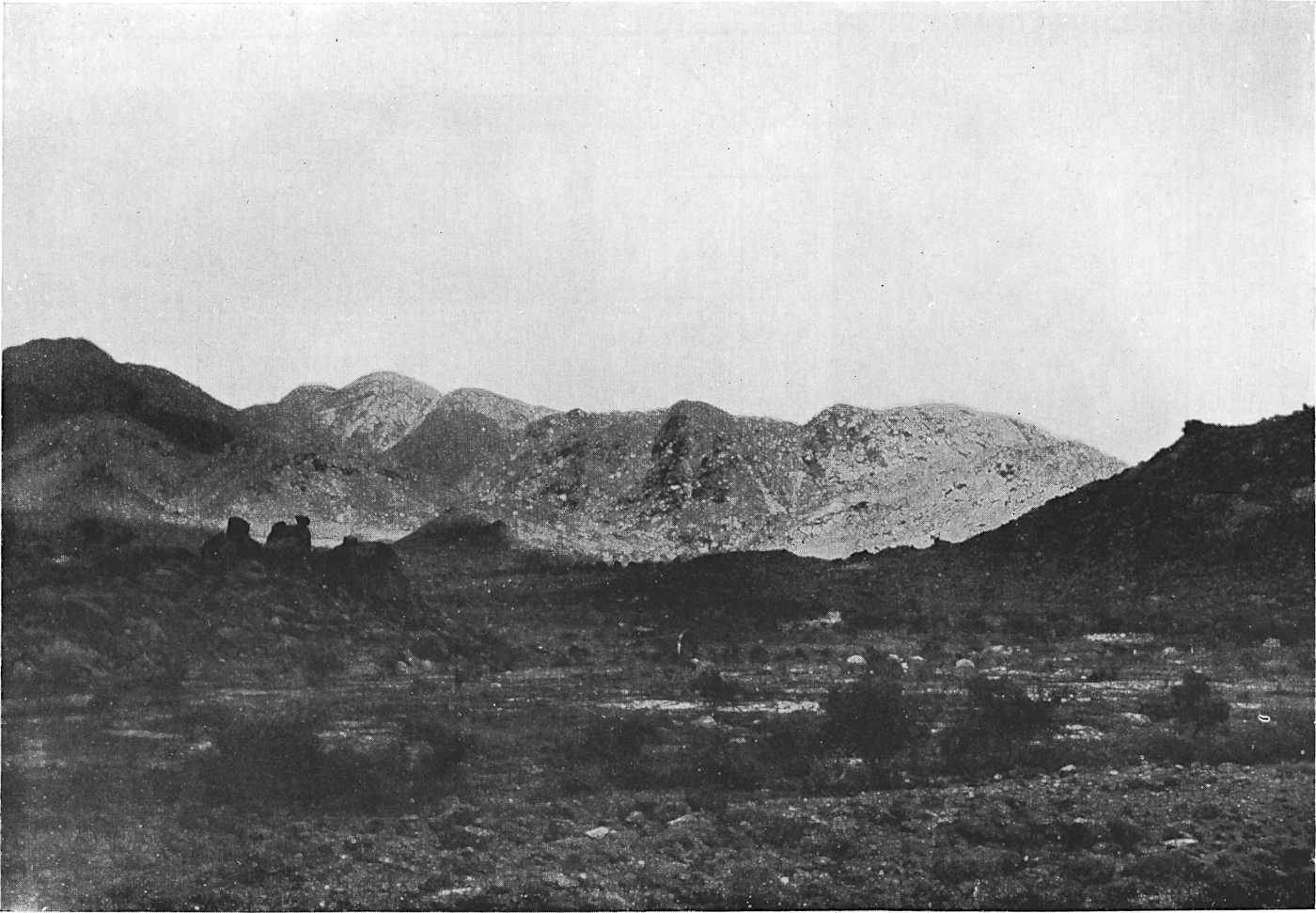

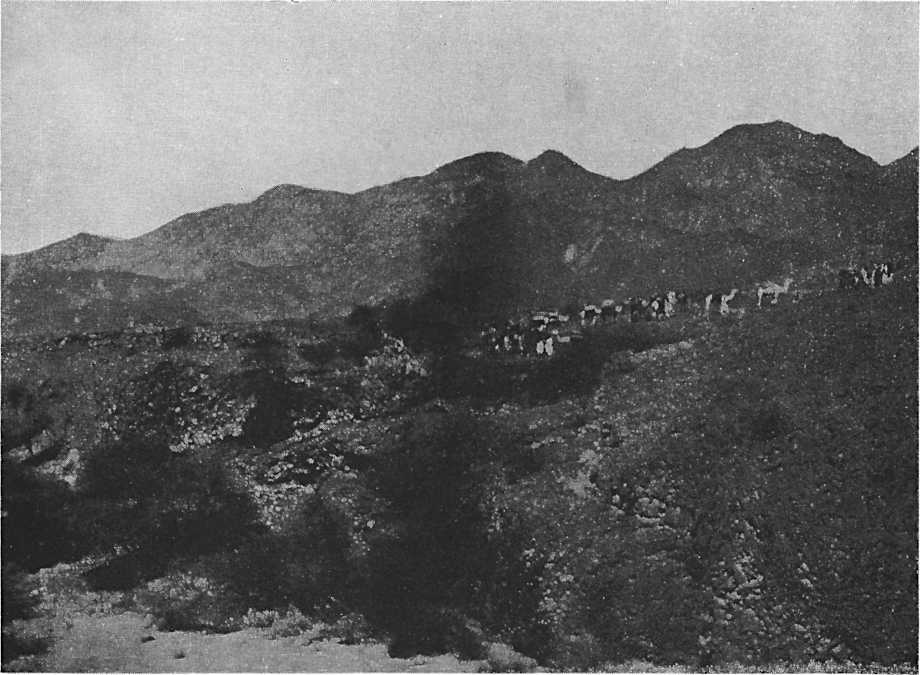

| 19. | Bagezan Mountains and Towar Village | 182 | |||

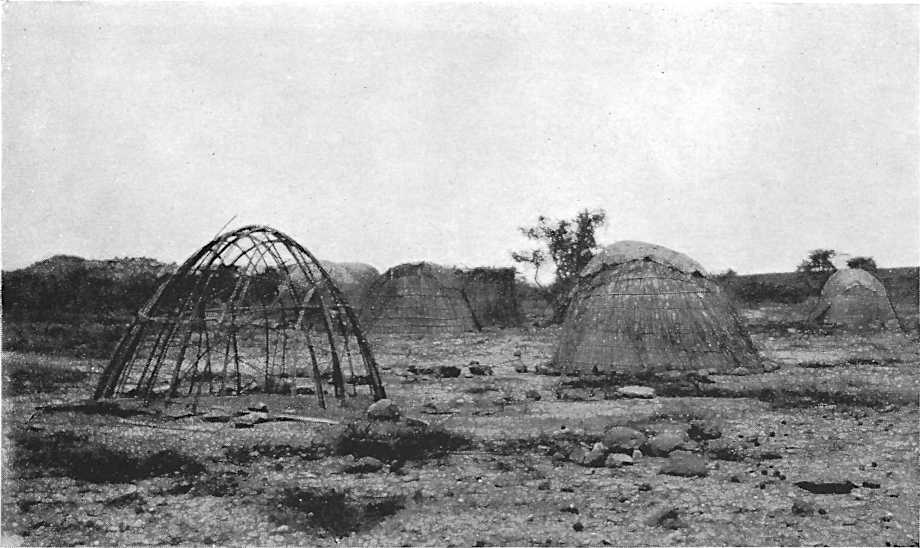

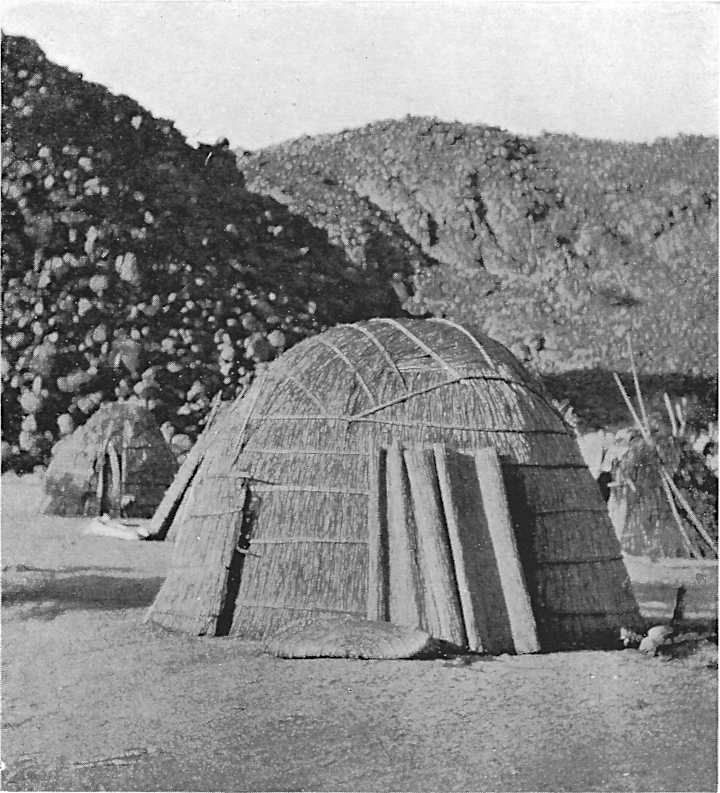

| [xiv]20. | Huts at Towar showing Method of Construction | 184 | |||

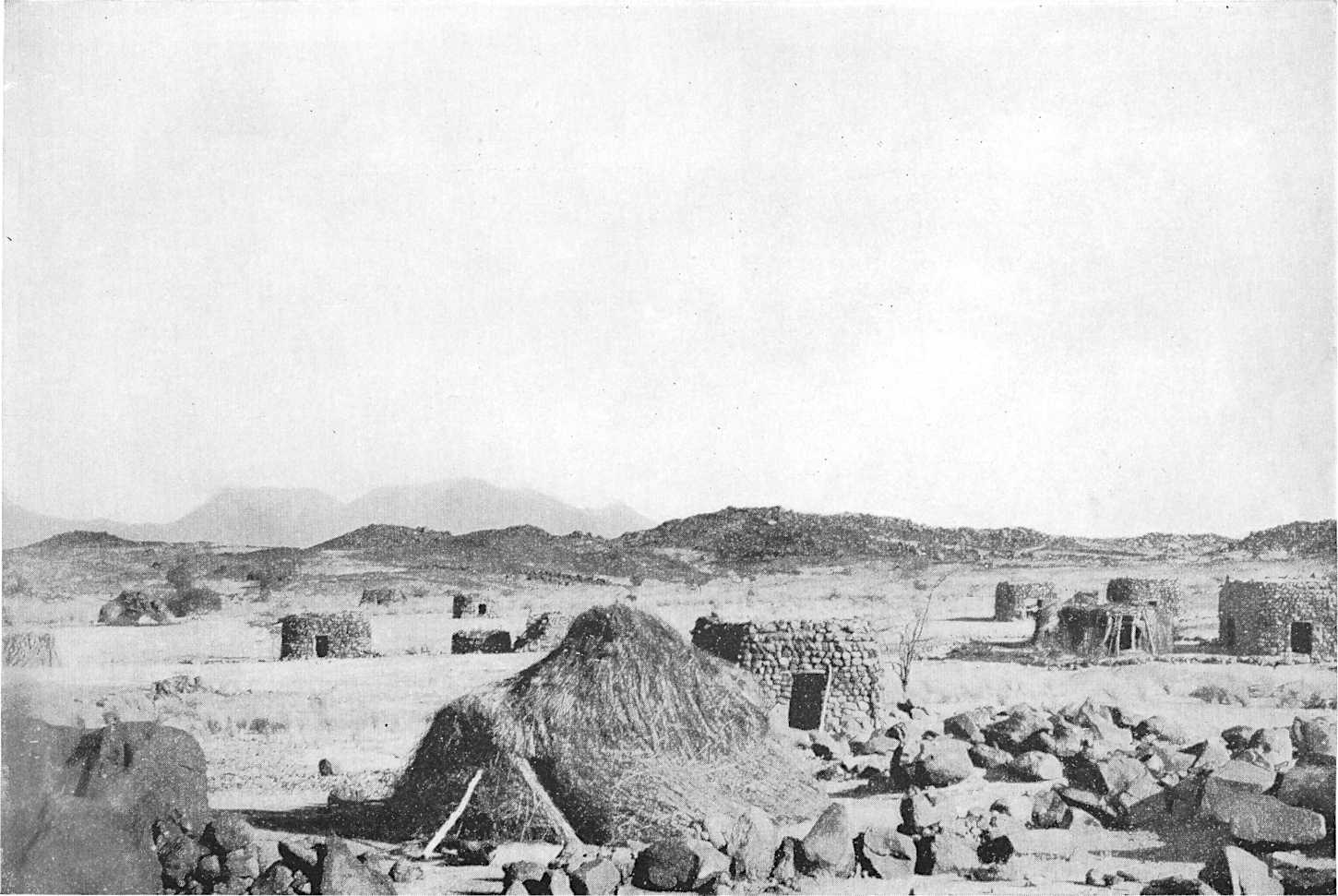

| Timia Huts | 184 | ||||

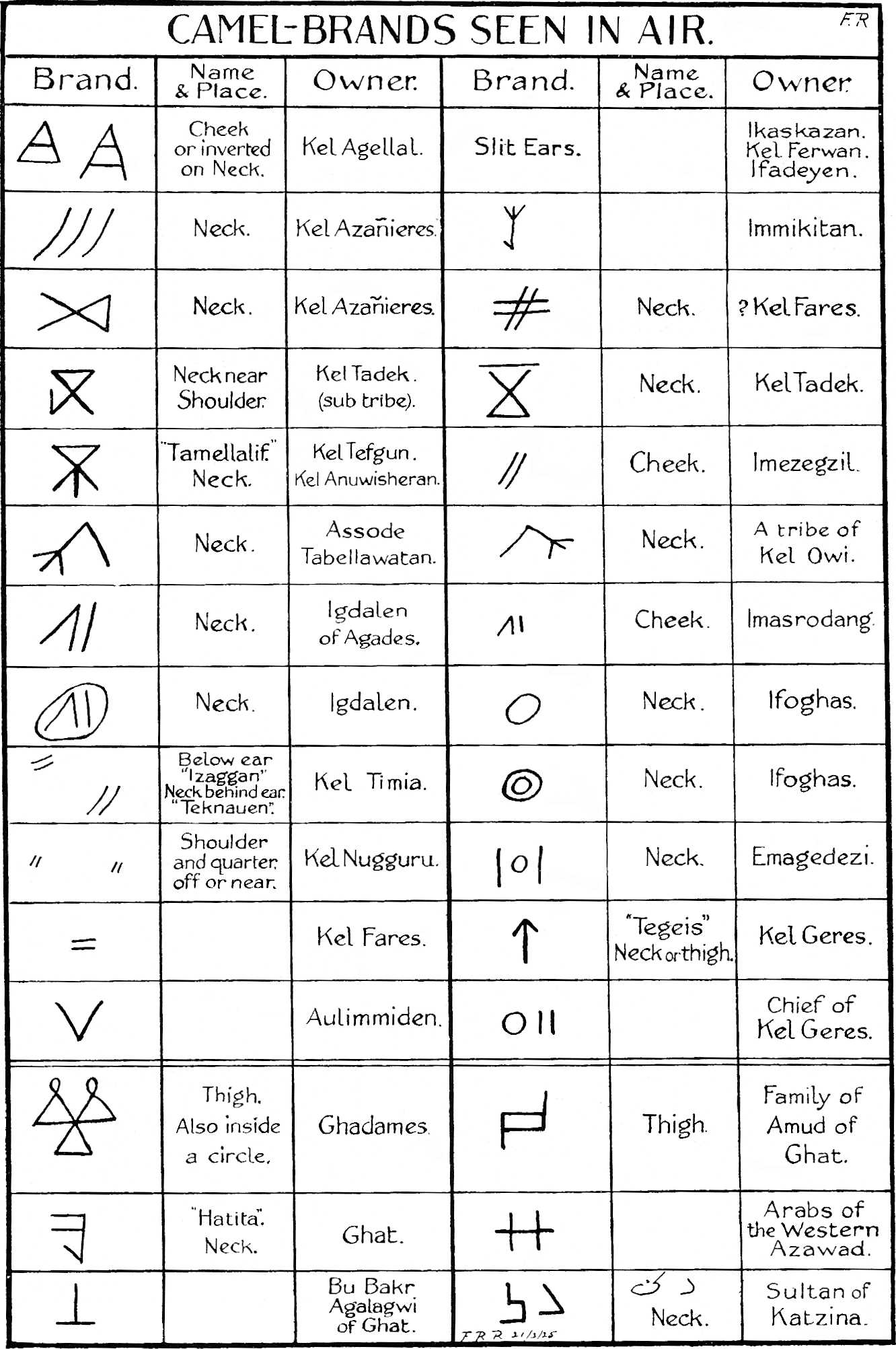

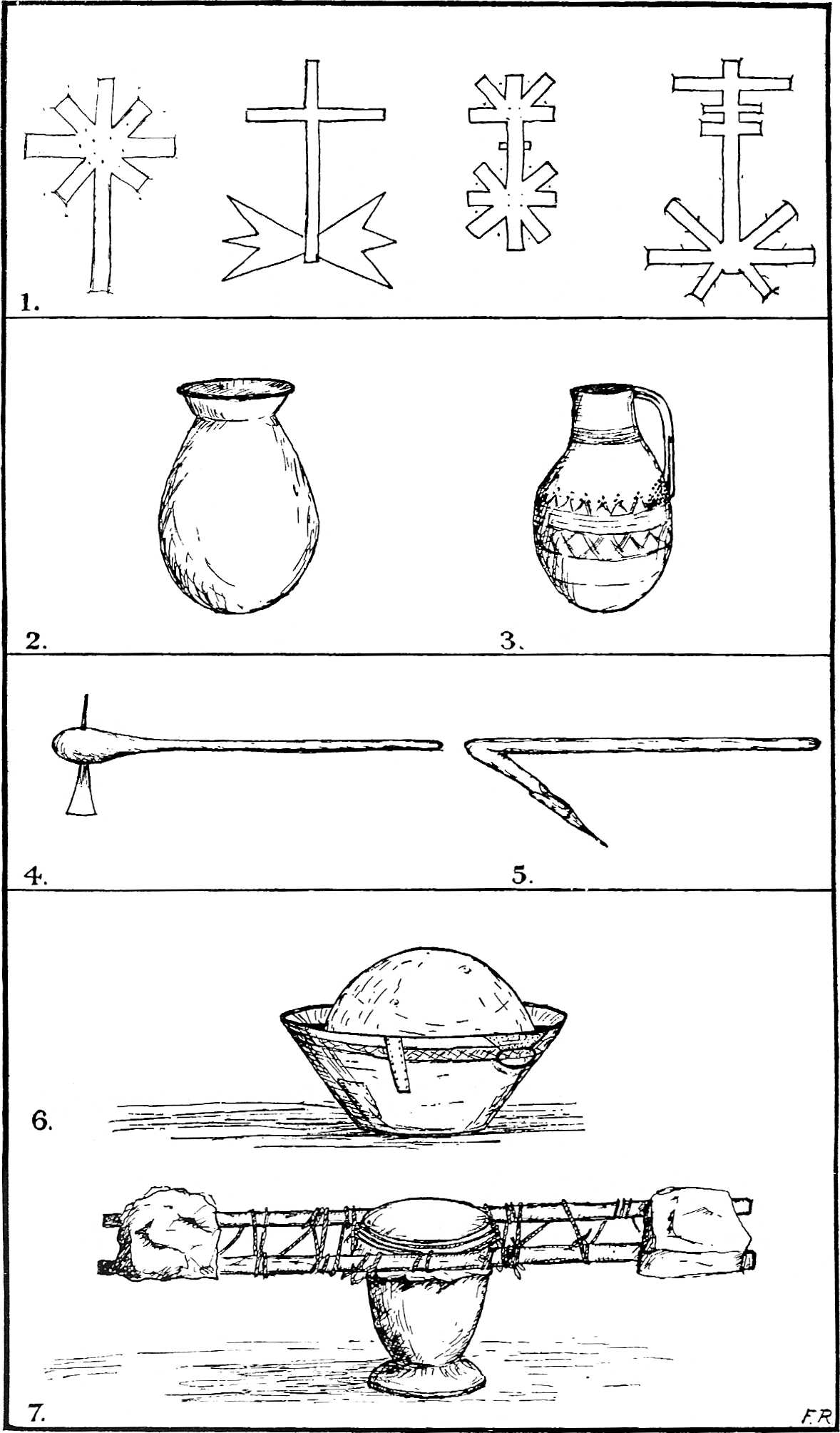

| 21. | Camel Brands | 195 | |||

| 22. | Shield Ornamentation and Utensils | 209 | |||

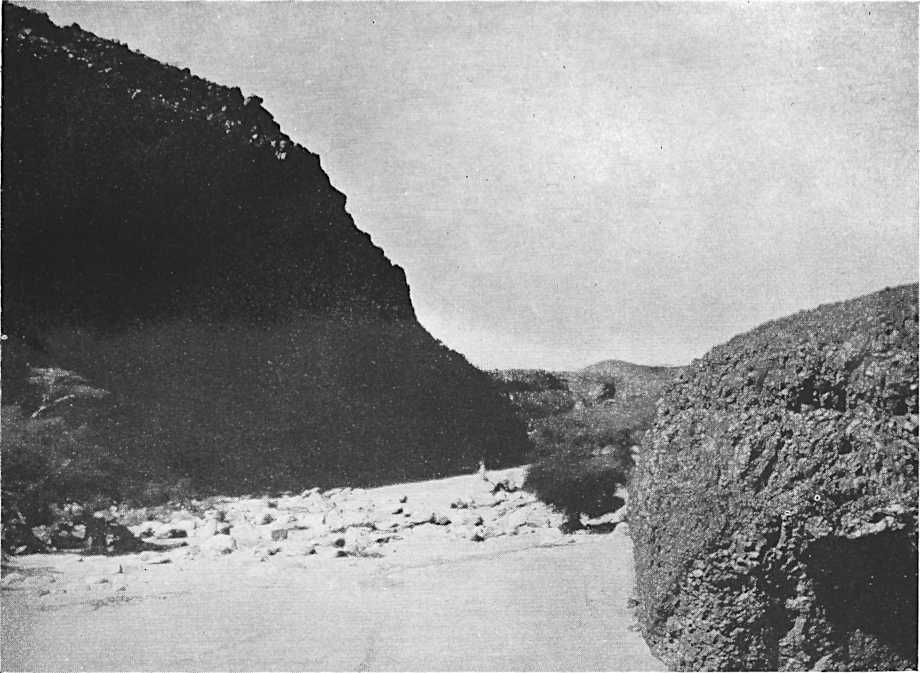

| 23. | Timia Gorge | 216 | |||

| Timia Gorge: Basalt and Granite Formations | 216 | ||||

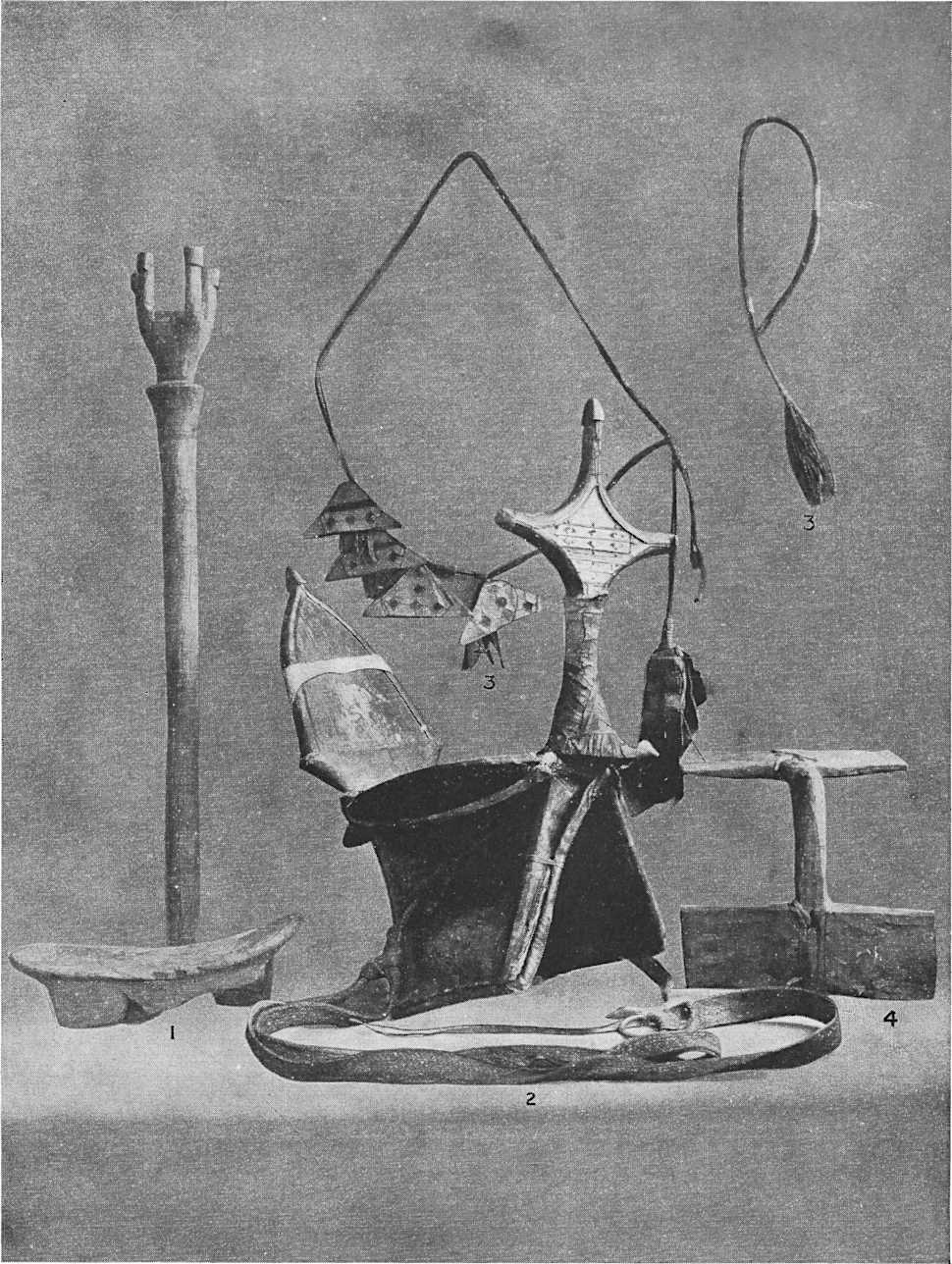

| 24. | Tuareg Personal Equipment | 227 | |||

| 25. | Tuareg Camel Equipment | 230 | |||

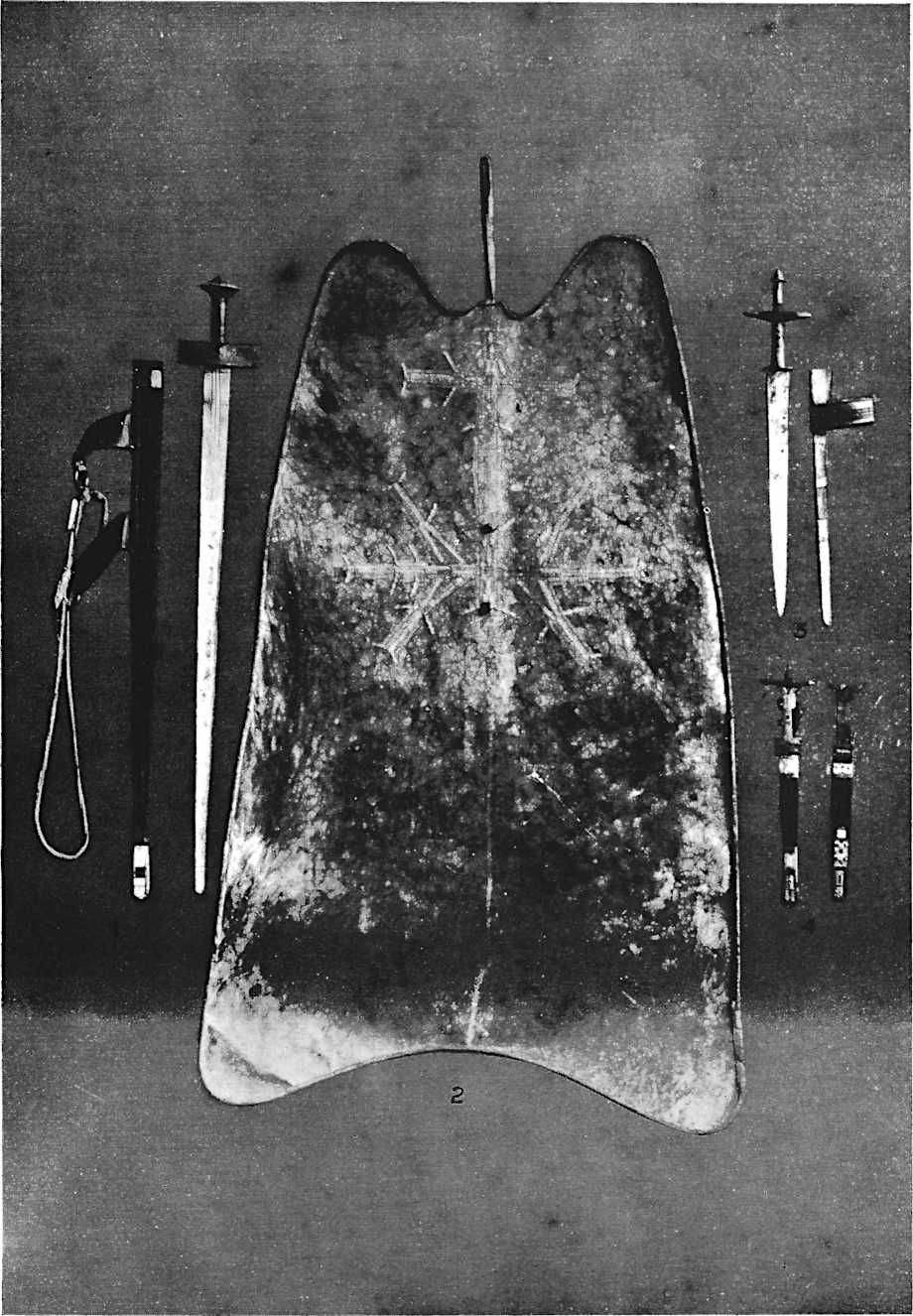

| 26. | Tuareg Weapons | 236 | |||

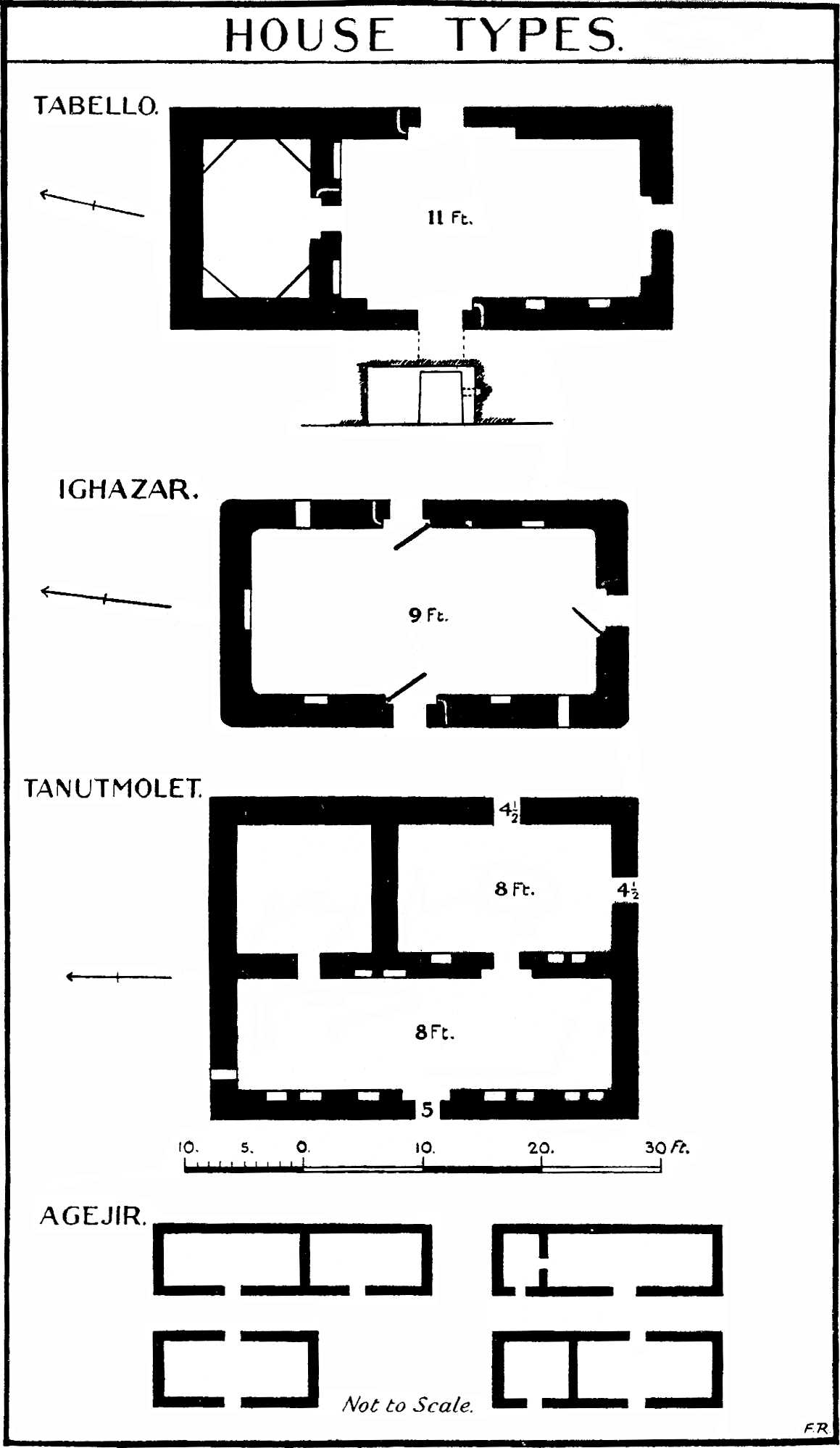

| 27. | House Types | 240 | |||

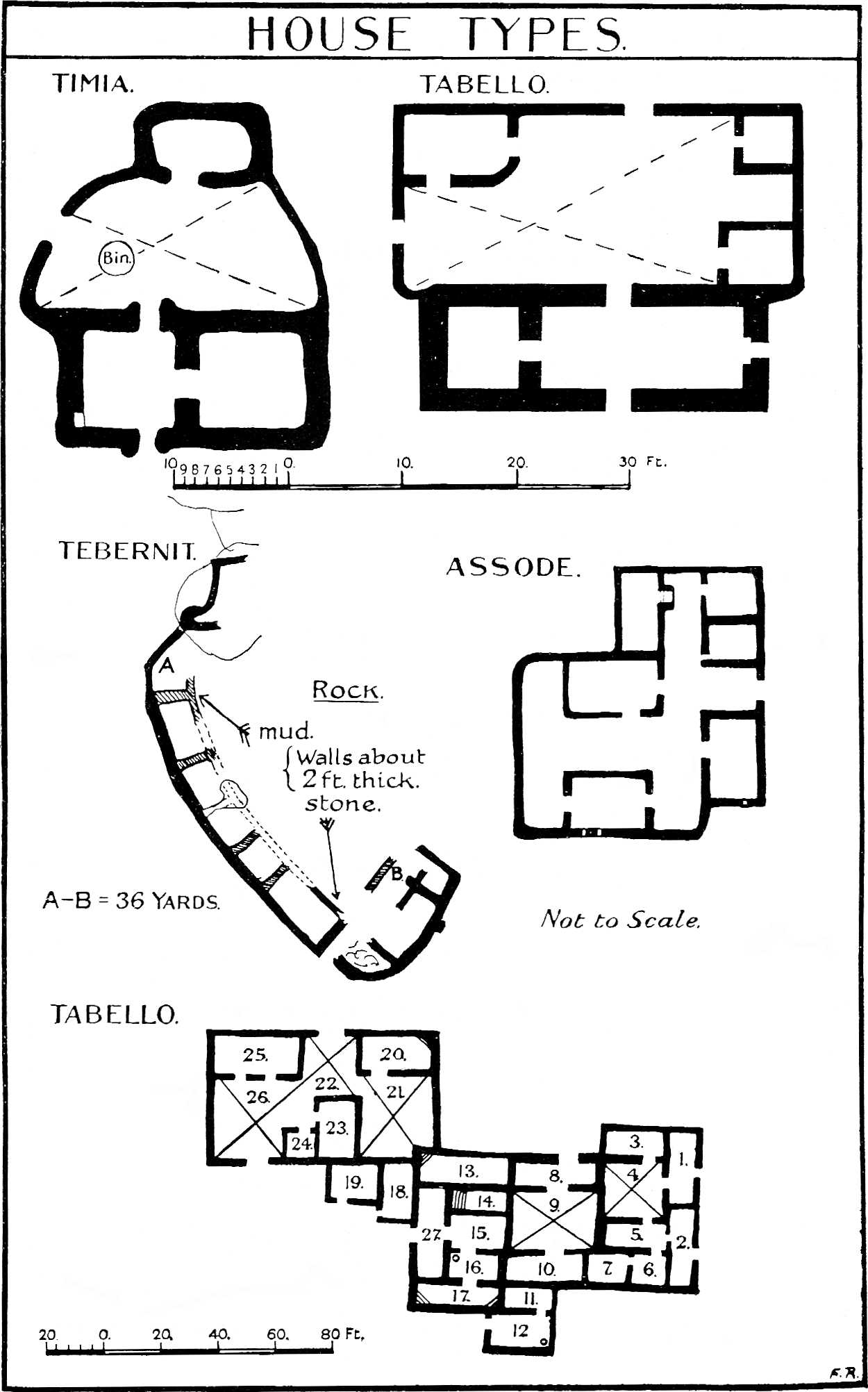

| 28. | House Types | 241 | |||

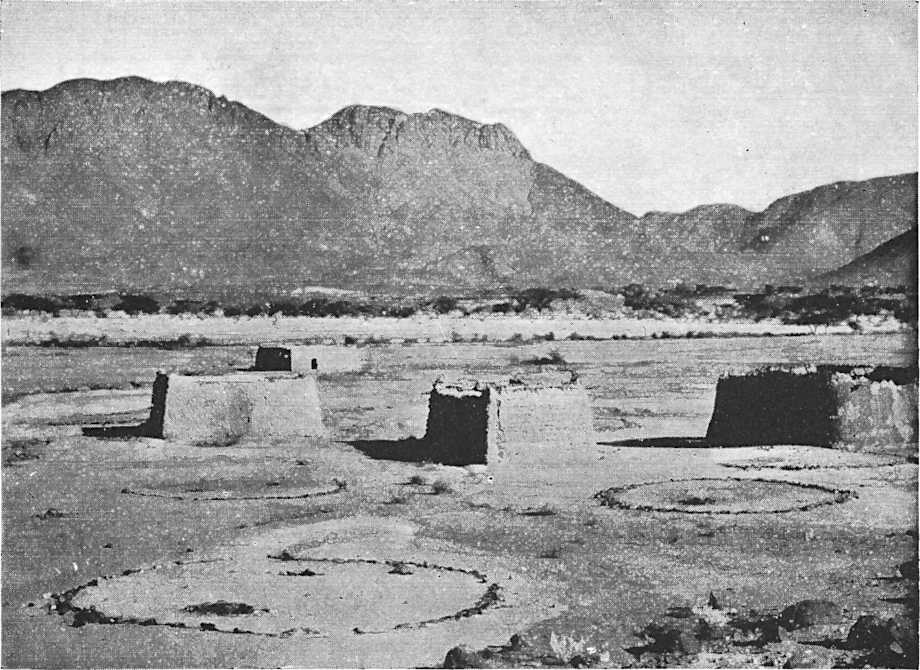

| 29. | Timia: “A” and “B” Type Houses and Hut Circles | 244 | |||

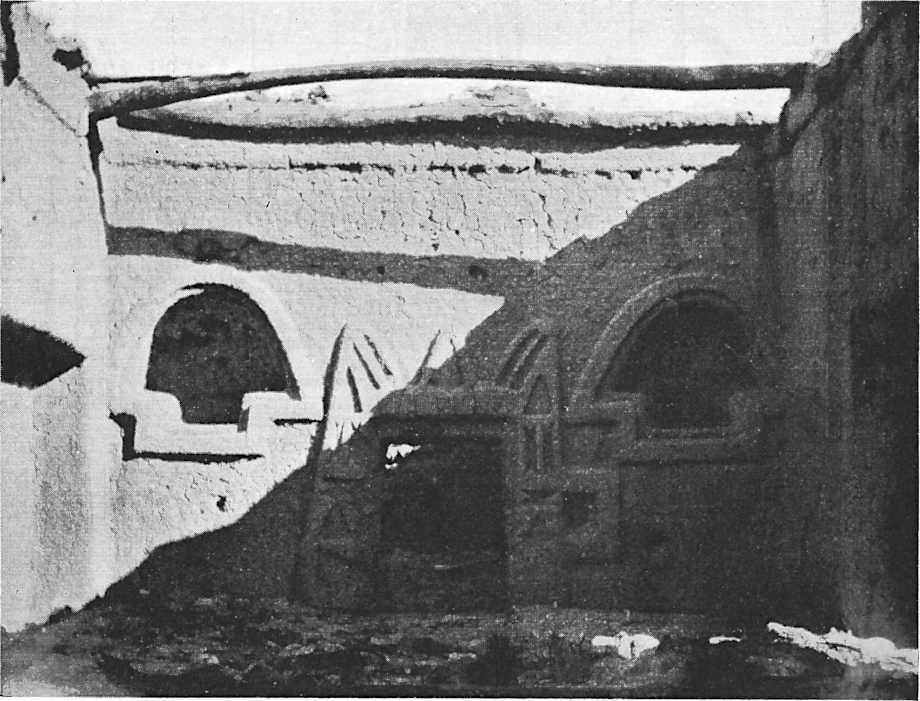

| Tabello: Interior of “A” Type House | 244 | ||||

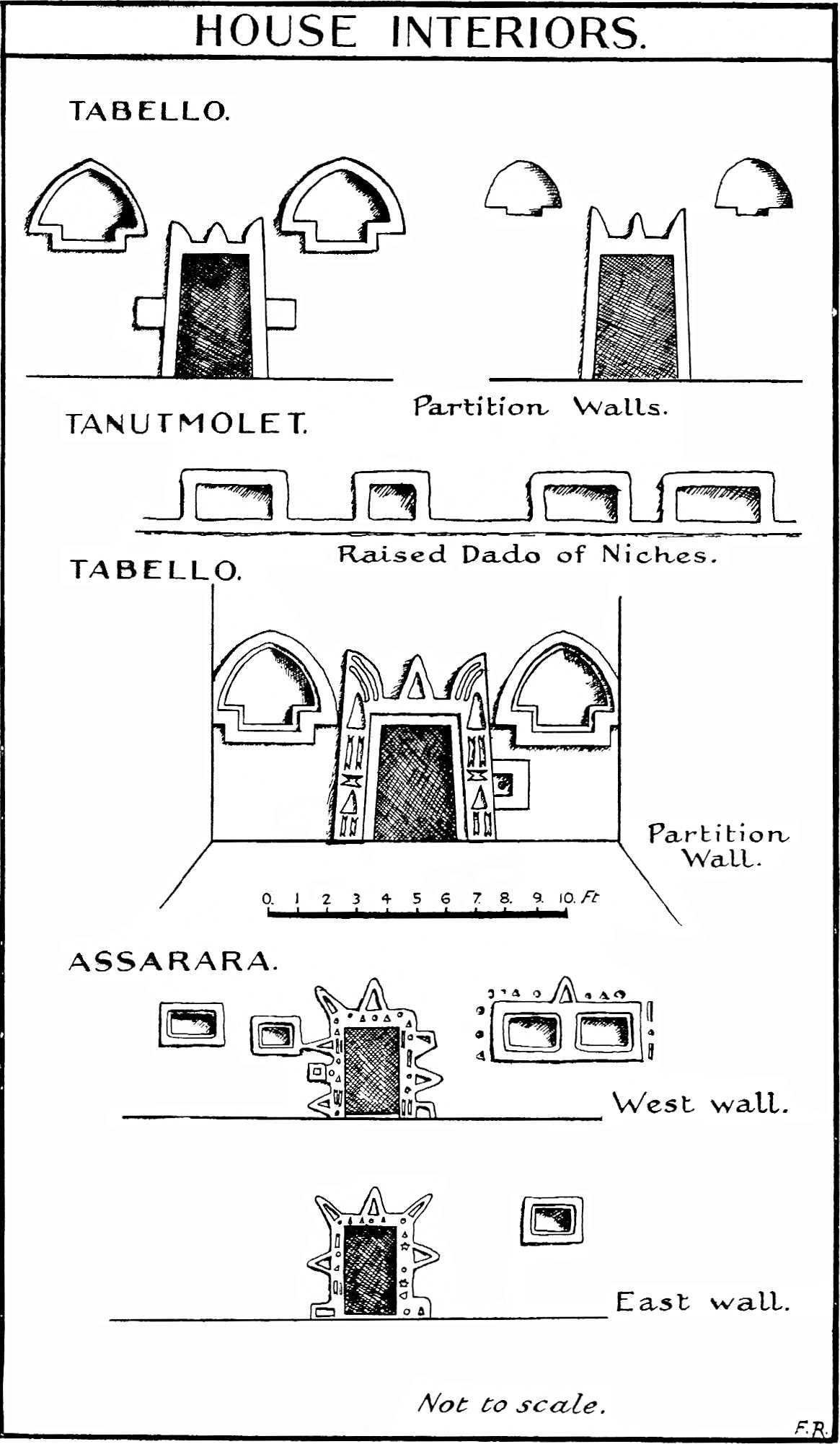

| 30. | House Interiors | 248 | |||

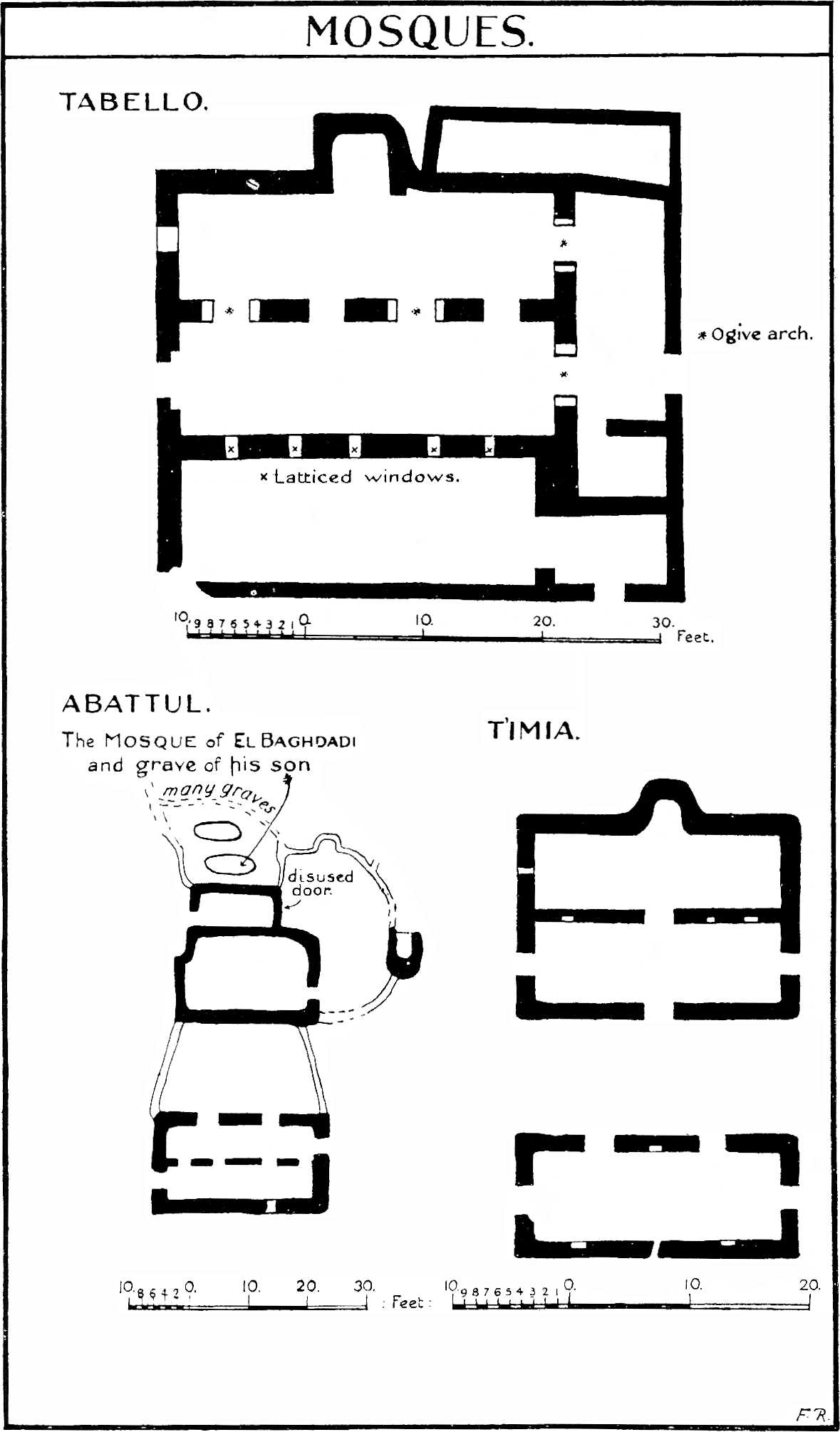

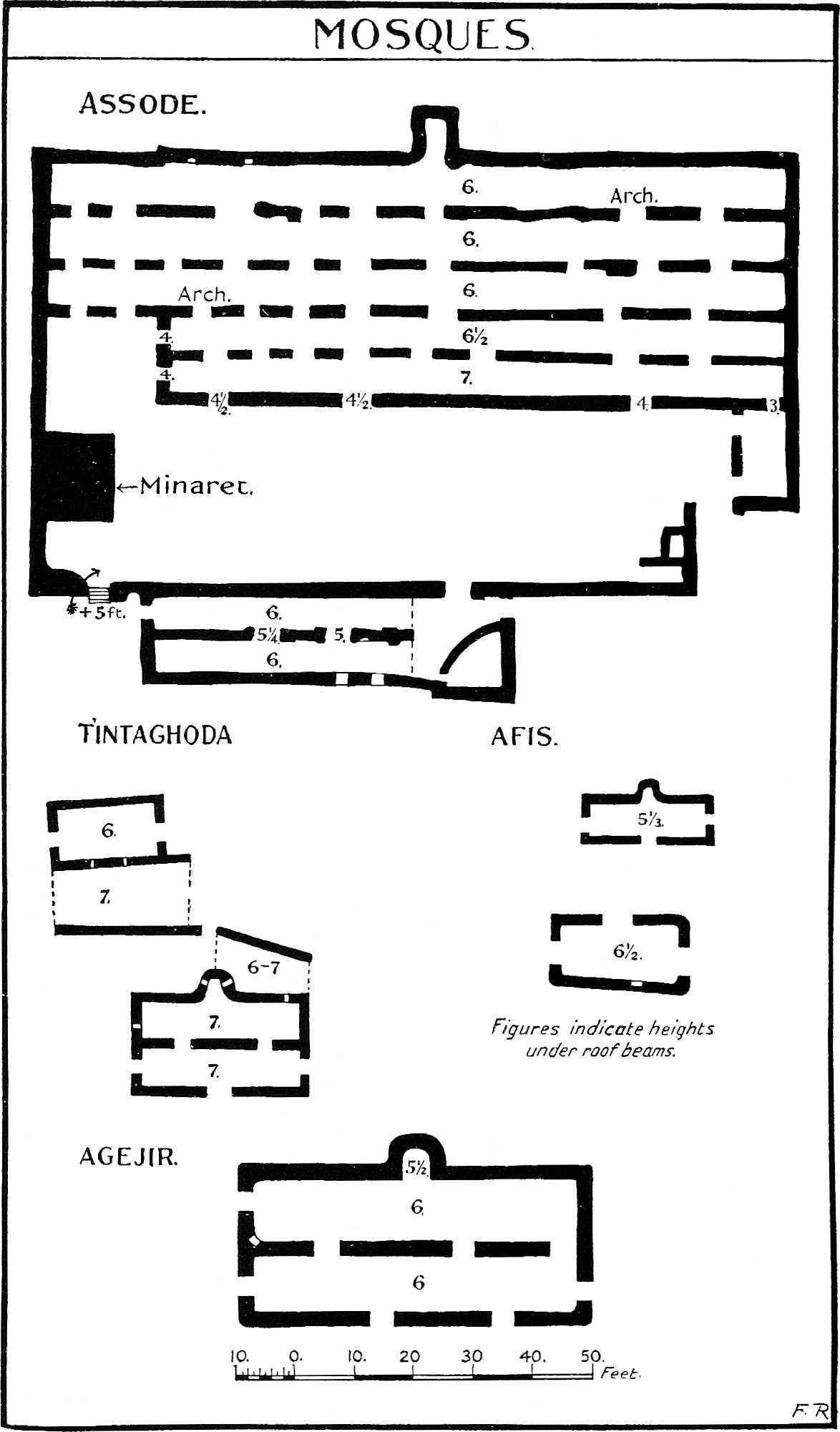

| 31. | Mosques | 256 | |||

| 32. | Mosques | 257 | |||

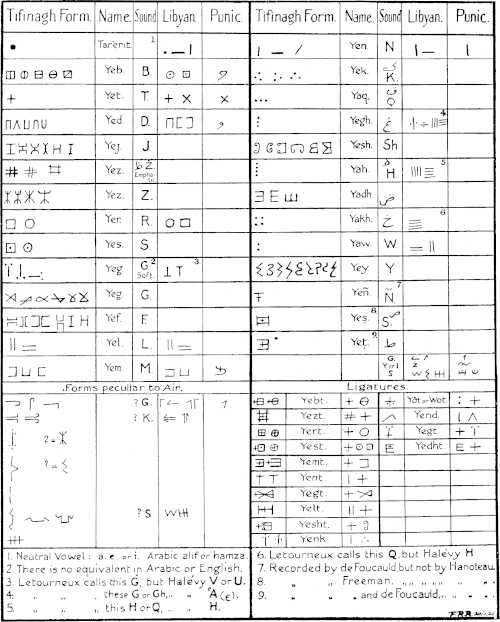

| 33. | Tifinagh Alphabet | 267 | |||

| 34. | Rock Inscriptions in Tifinagh | 269 | |||

| 35. | Mt. Abattul and Village | 275 | |||

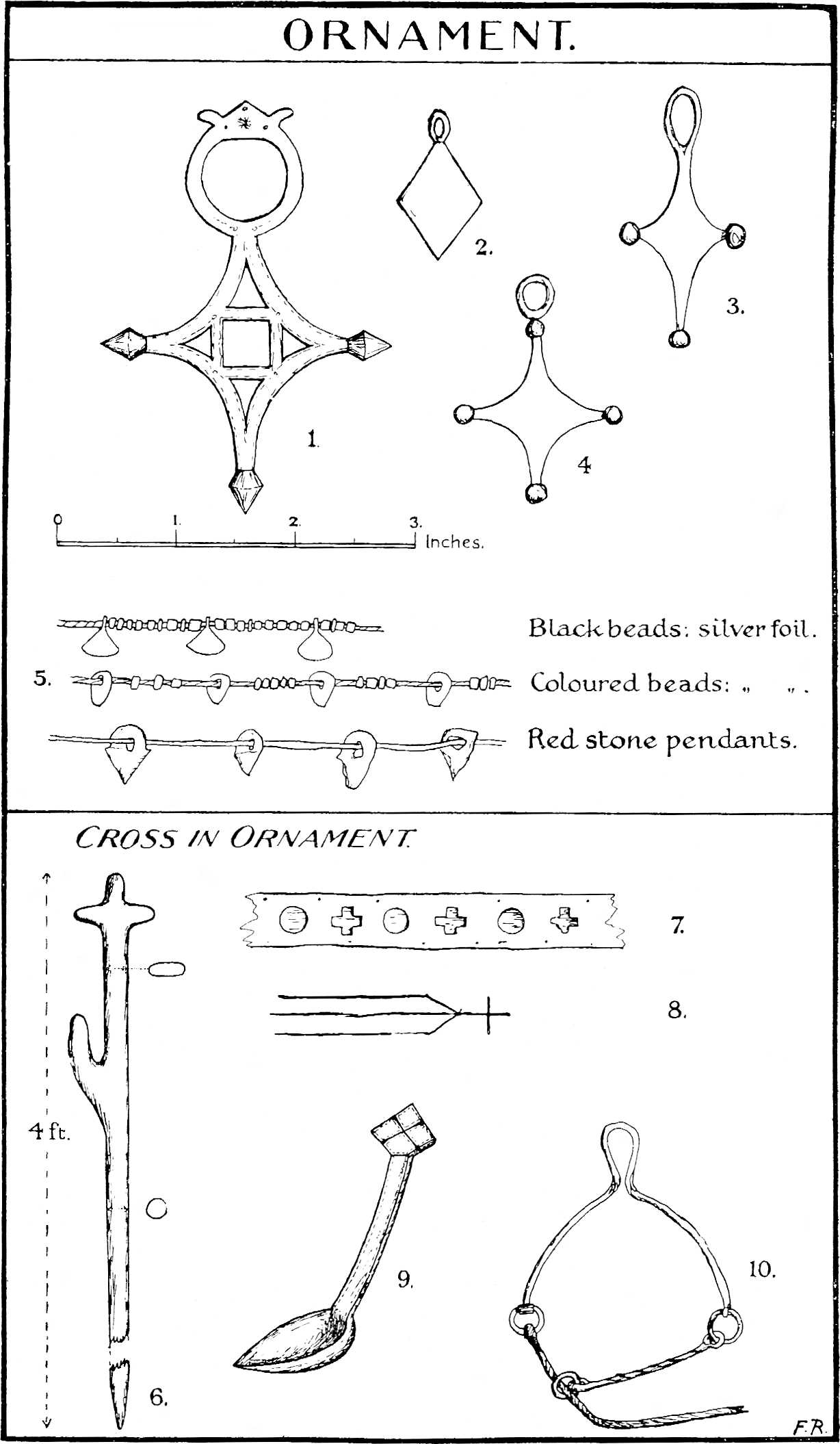

| 36. | The Cross in Ornament | 277 | |||

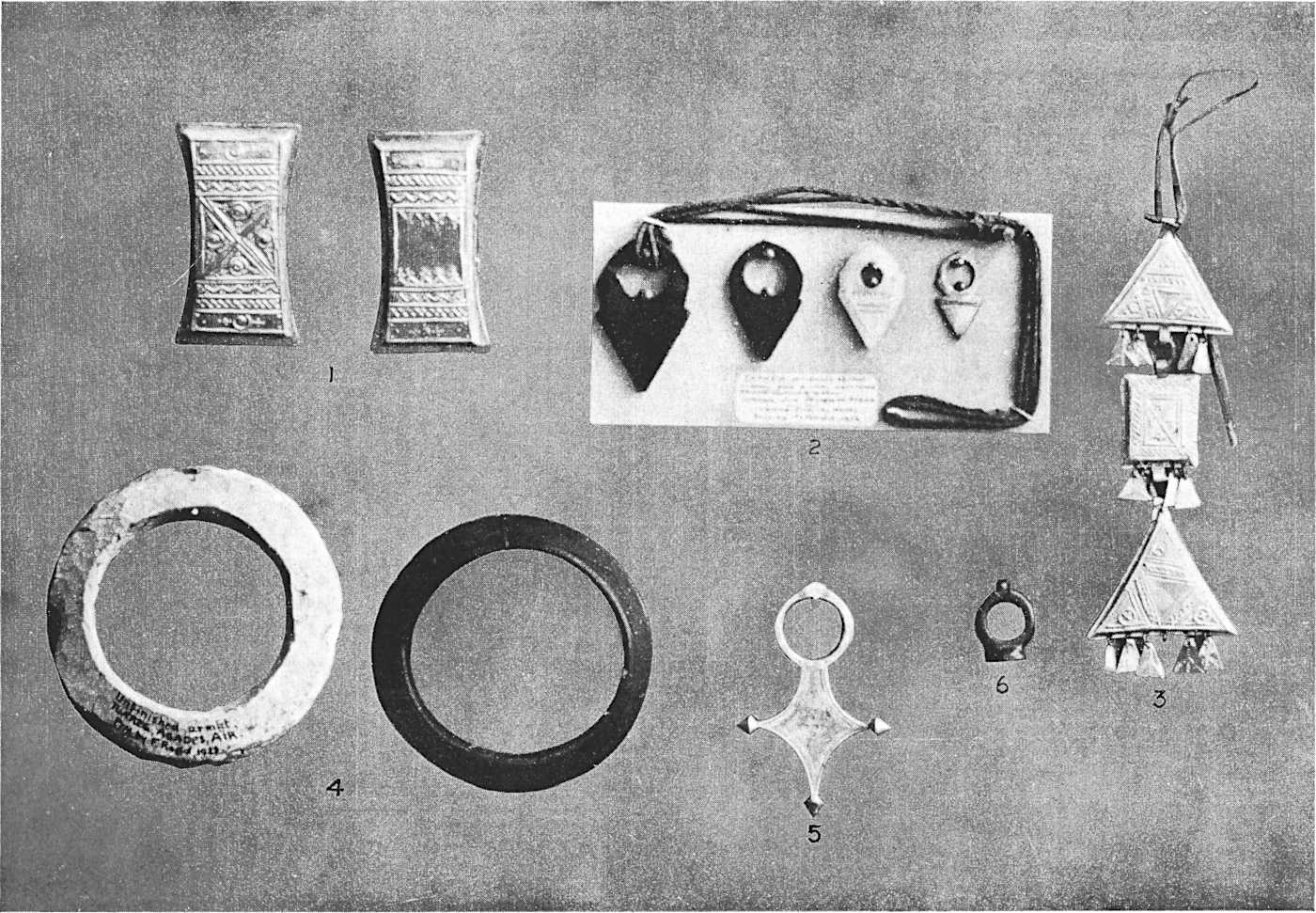

| 37. | Tuareg Personal Ornaments | 285 | |||

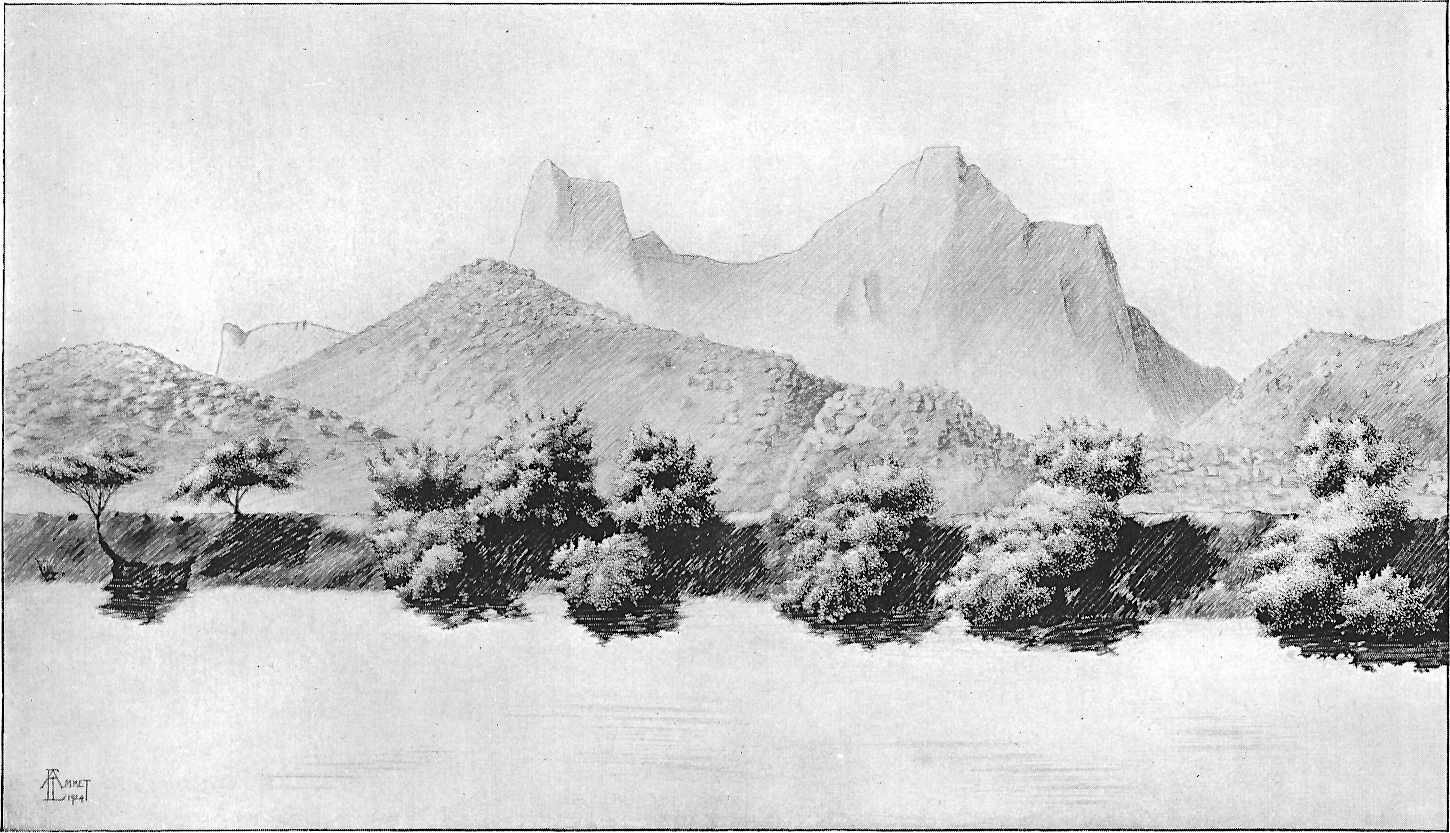

| 38. | Mt. Arwa | 295 | |||

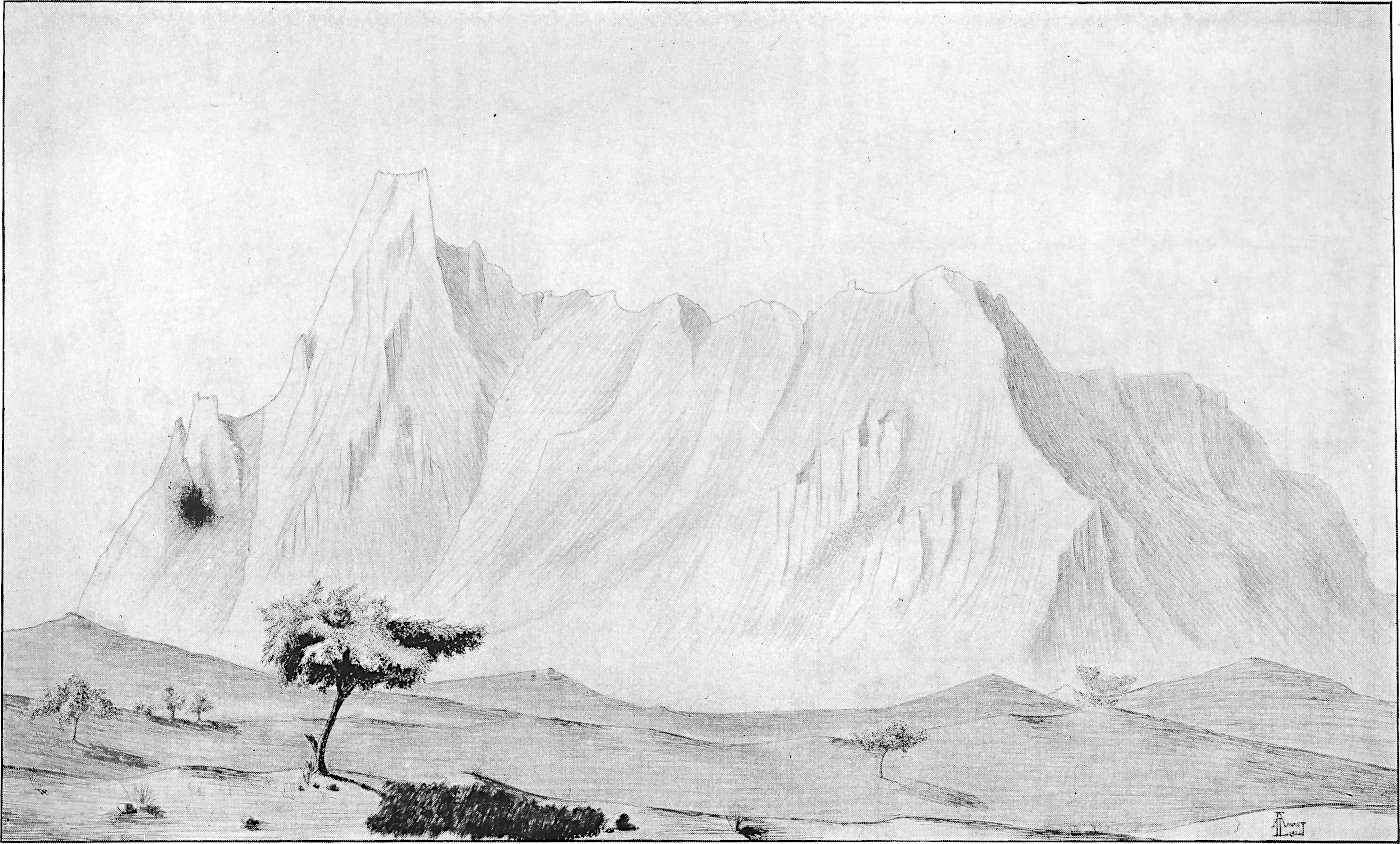

| 39. | Mt. Aggata | 300 | |||

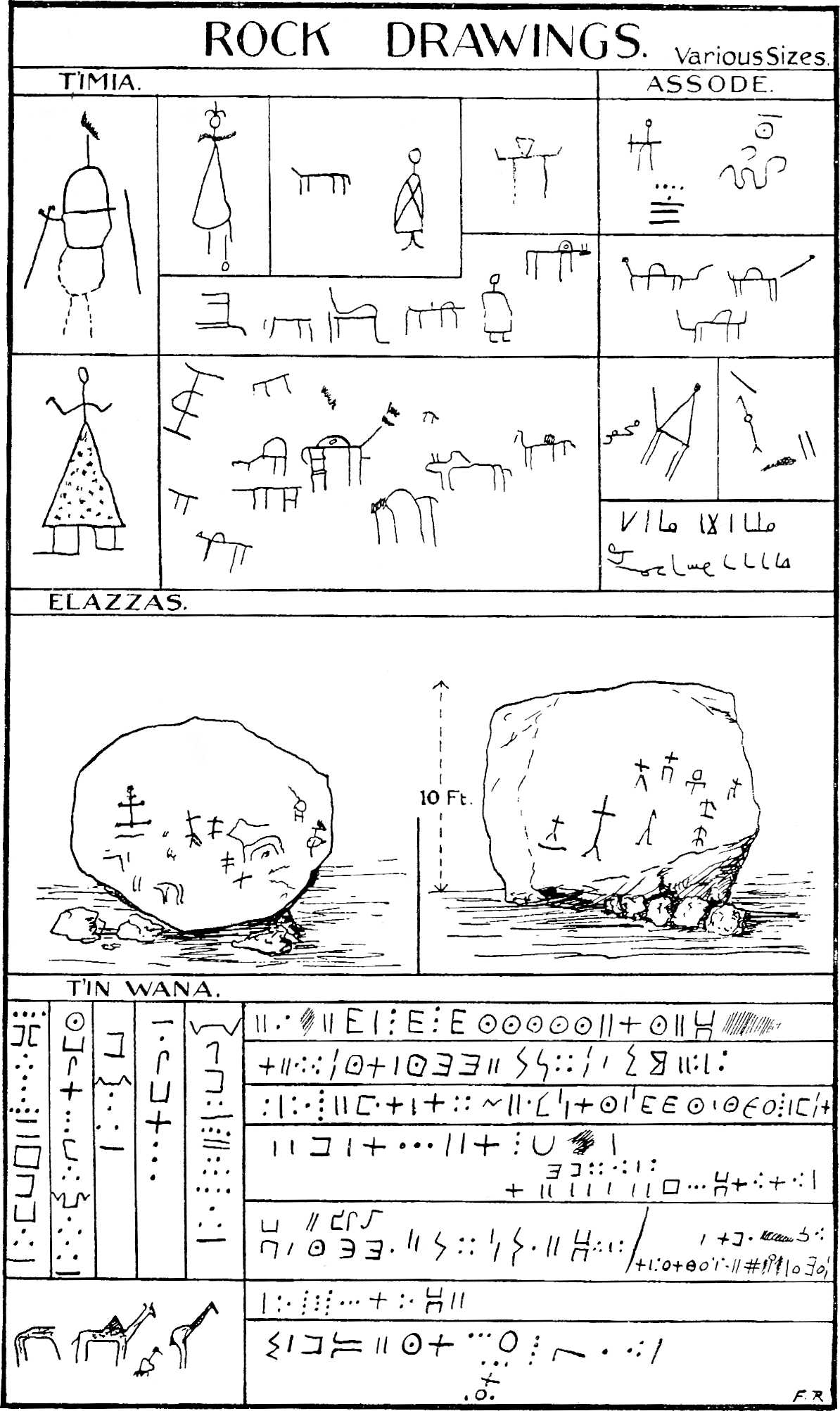

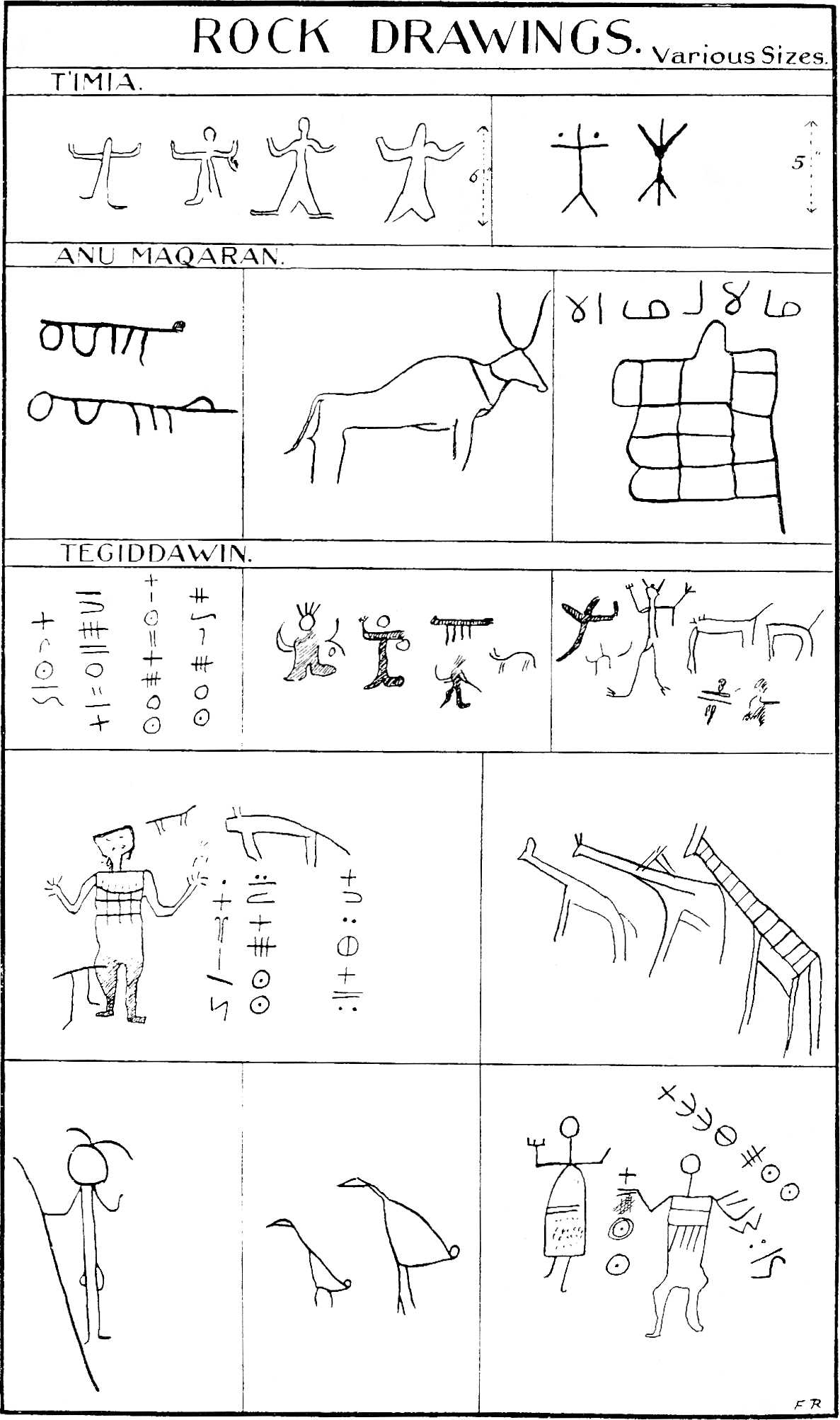

| 40. | Rock Drawings | 305 | |||

| 41. | Rock Drawings | 306 | |||

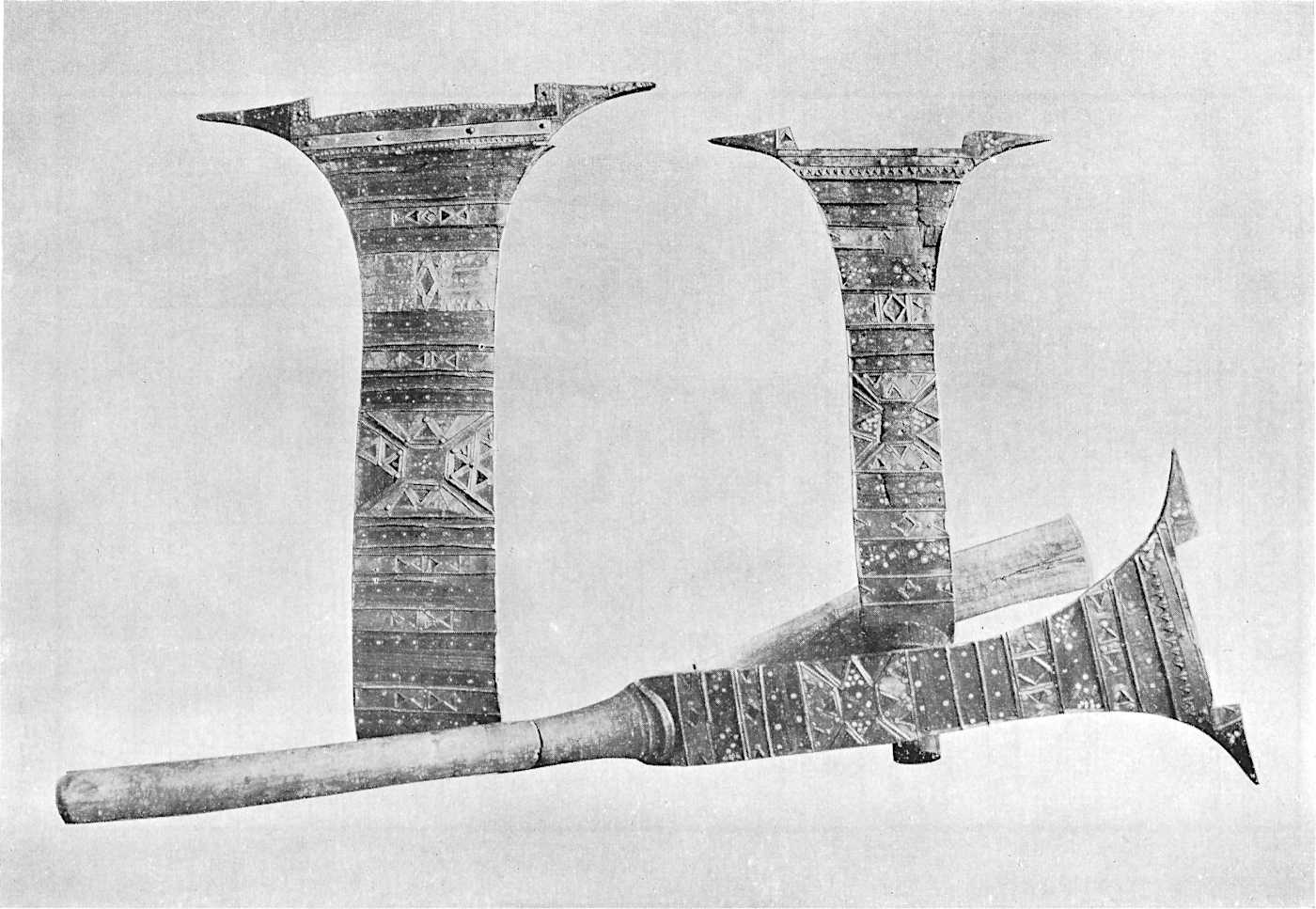

| 42. | Ornamented Baggage Rests | 310 | |||

| 43. | T’intellust | 312 | |||

| 44. | Barth’s Camp at T’intellust | 313 | |||

| Barth’s Camp at T’intellust (another view) | 313 | ||||

| 45. | Assarara | 326 | |||

| 46. | Fugda, Chief of Timia, and His Wakil | 352 | |||

| Atagoom | 352 | ||||

| 47. | Sidi | 366 | |||

| 48. | Eghalgawen Pool | 400 | |||

| Tizraet Pool | 400 | ||||

| [xv]49. | Eghalgawen Valley and the Last Hills of Air | 414 | |||

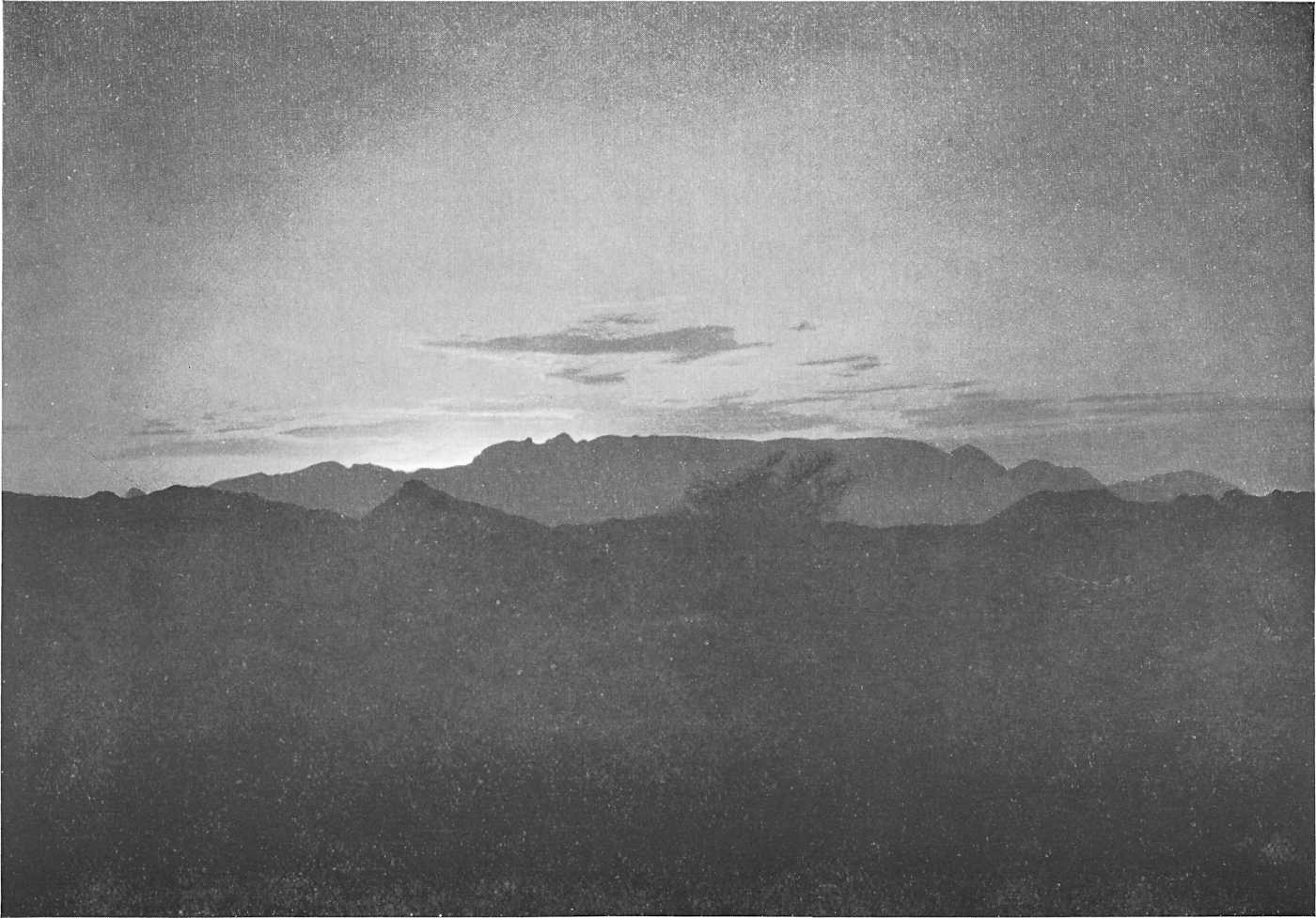

| 50. | Mt. Bila at Sunset | 419 | |||

| Additional Plate |

⎰ ⎱ |

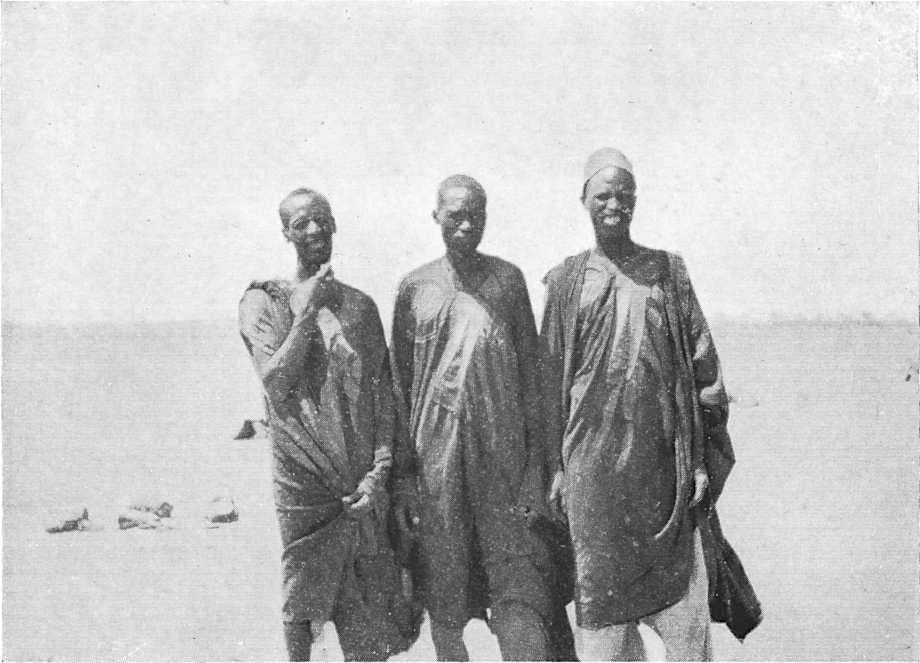

Typical Tebu | 442 | ||

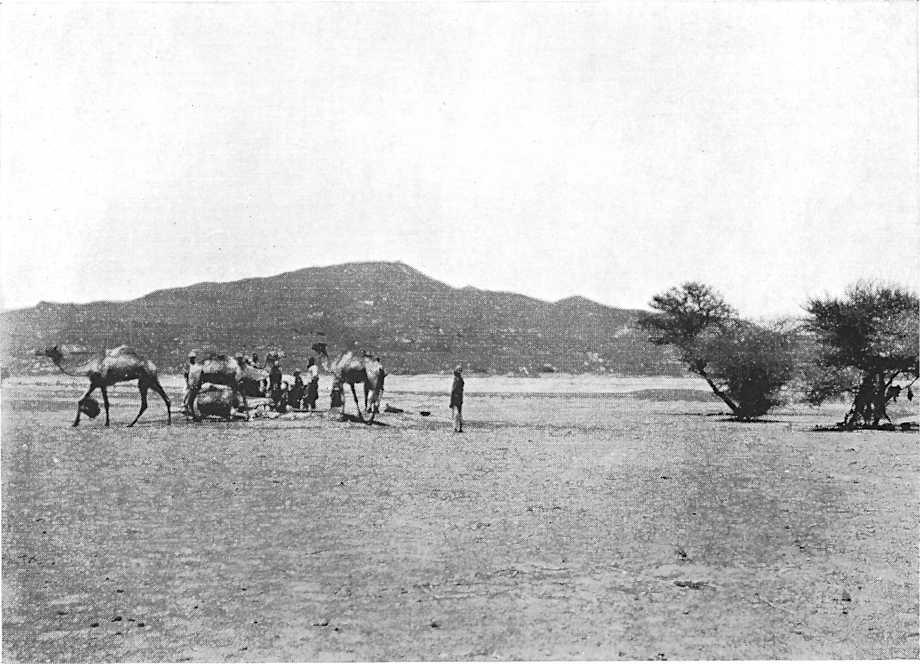

| Termit Peak and Well | 442 | ||||

| MAPS AND DIAGRAMS | |||||

| PAGE | |||||

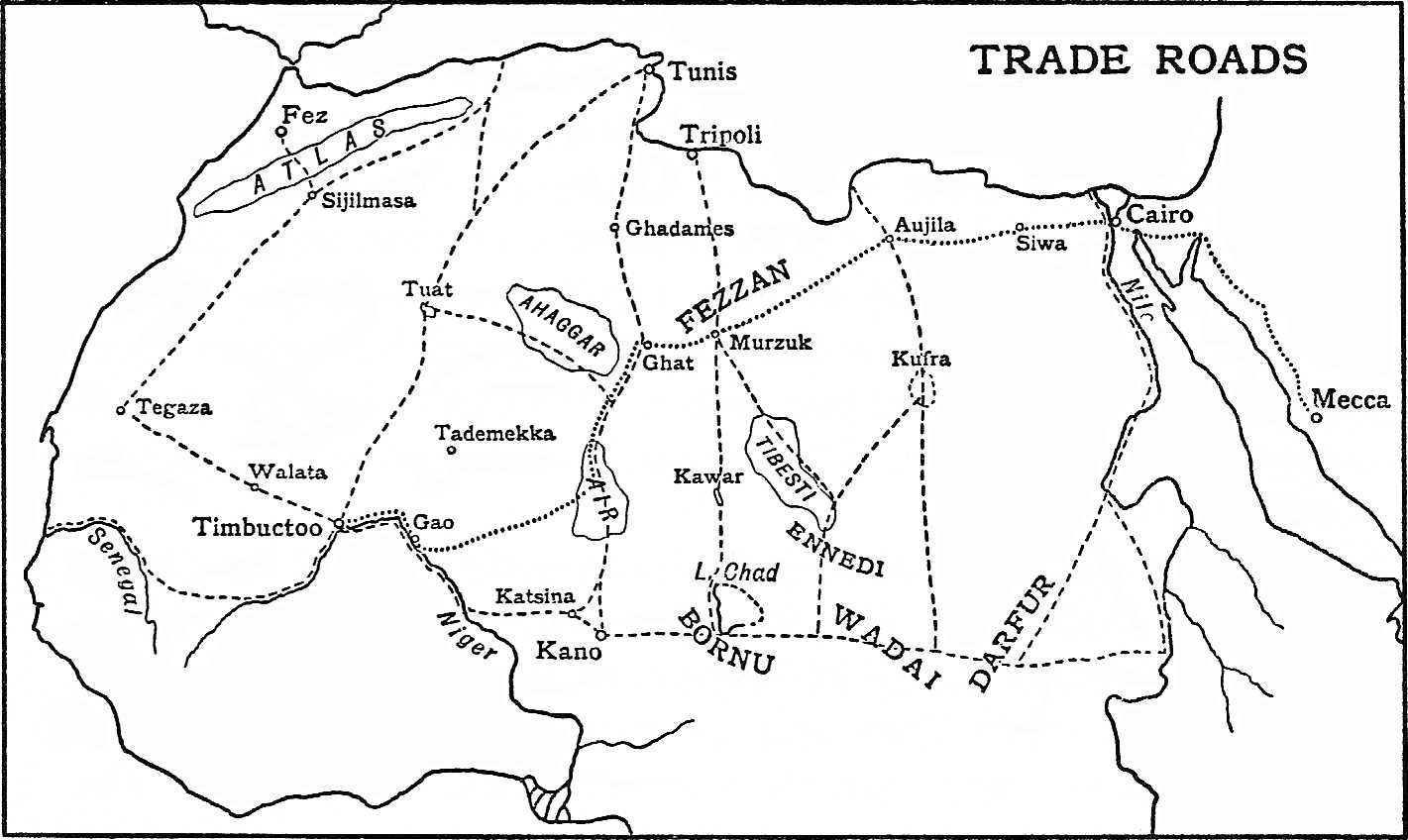

| Map showing the Trade Roads of North Africa | 5 | ||||

| Diagrammatic Map showing the Drainage of the Central Sahara | 29 | ||||

| Map of Damergu and Neighbouring Parts: 1/2,000,000 | facing p. | 36 | |||

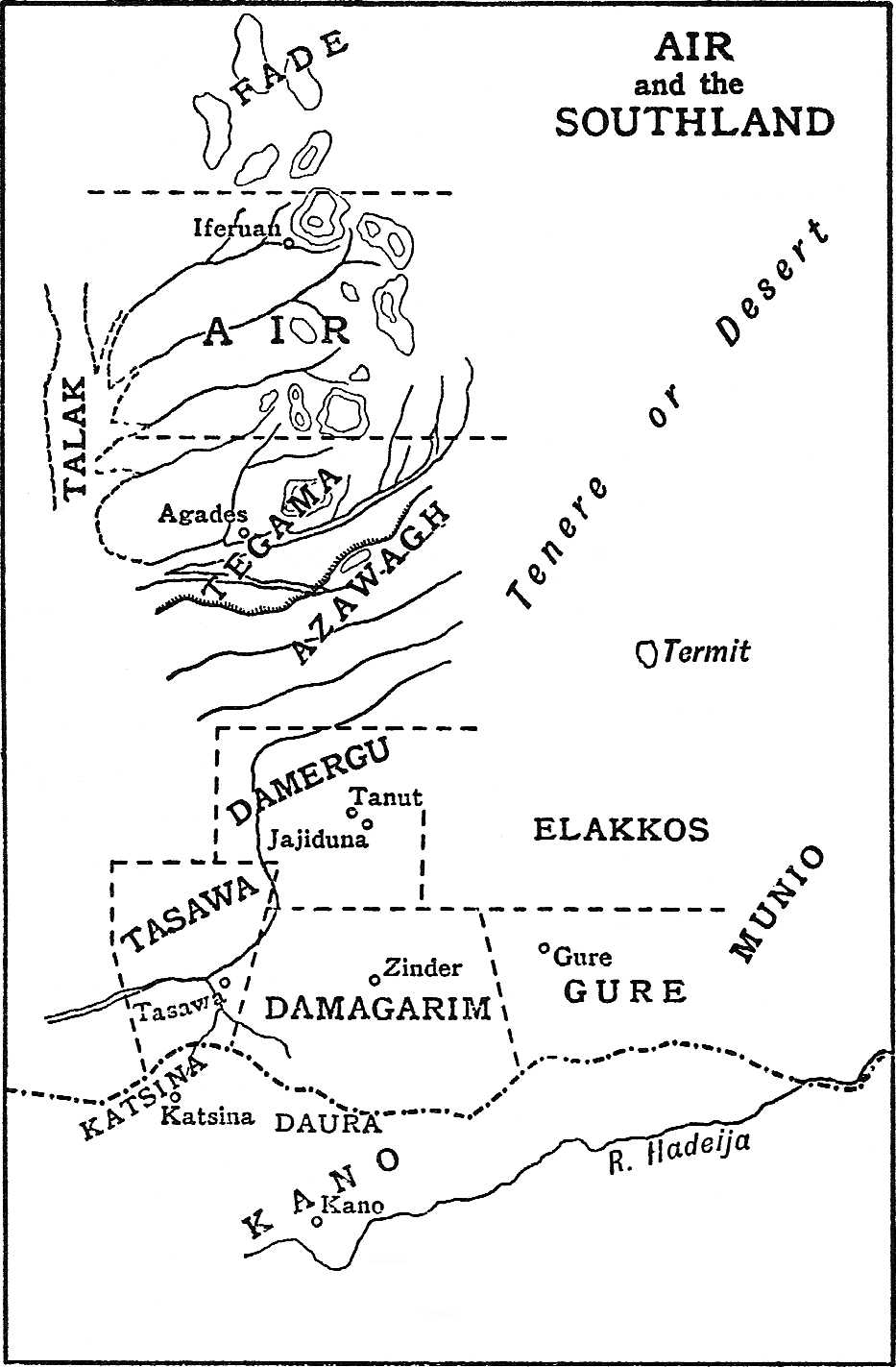

| Sketch Map of Air and the Divisions of the Southland | 40 | ||||

| Diagram showing Tribal Descent among the Tuareg | 130 | ||||

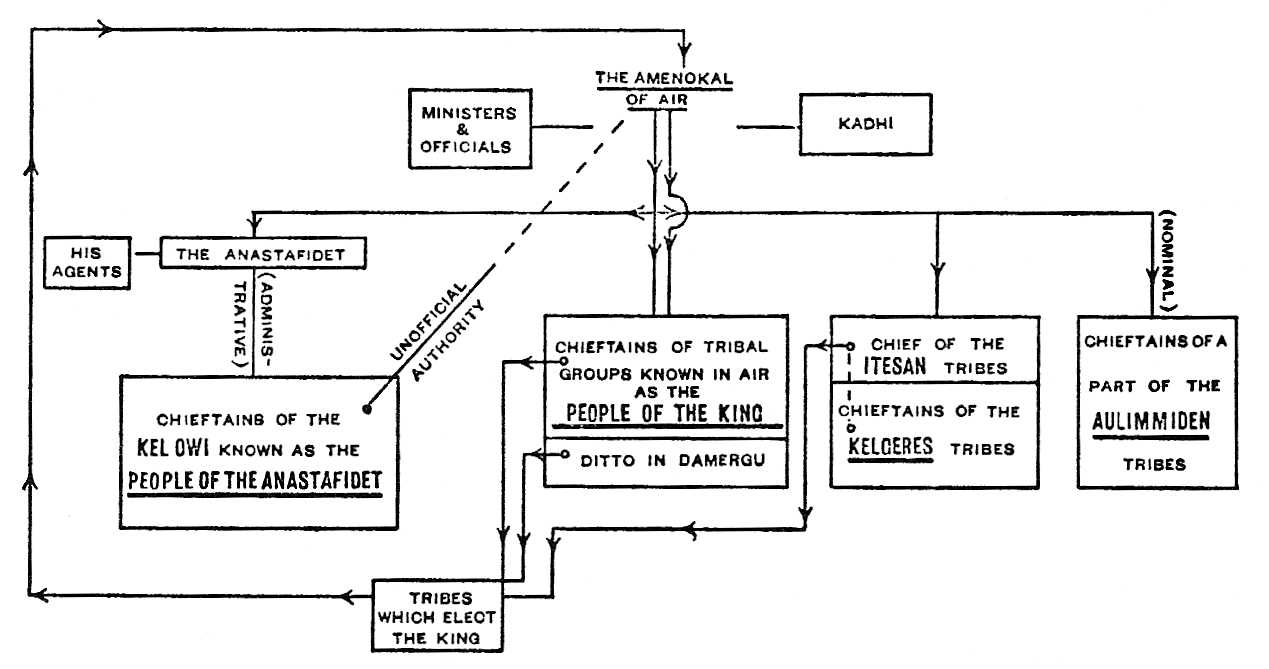

| Diagram showing the Government of the Air Tuareg | 144 | ||||

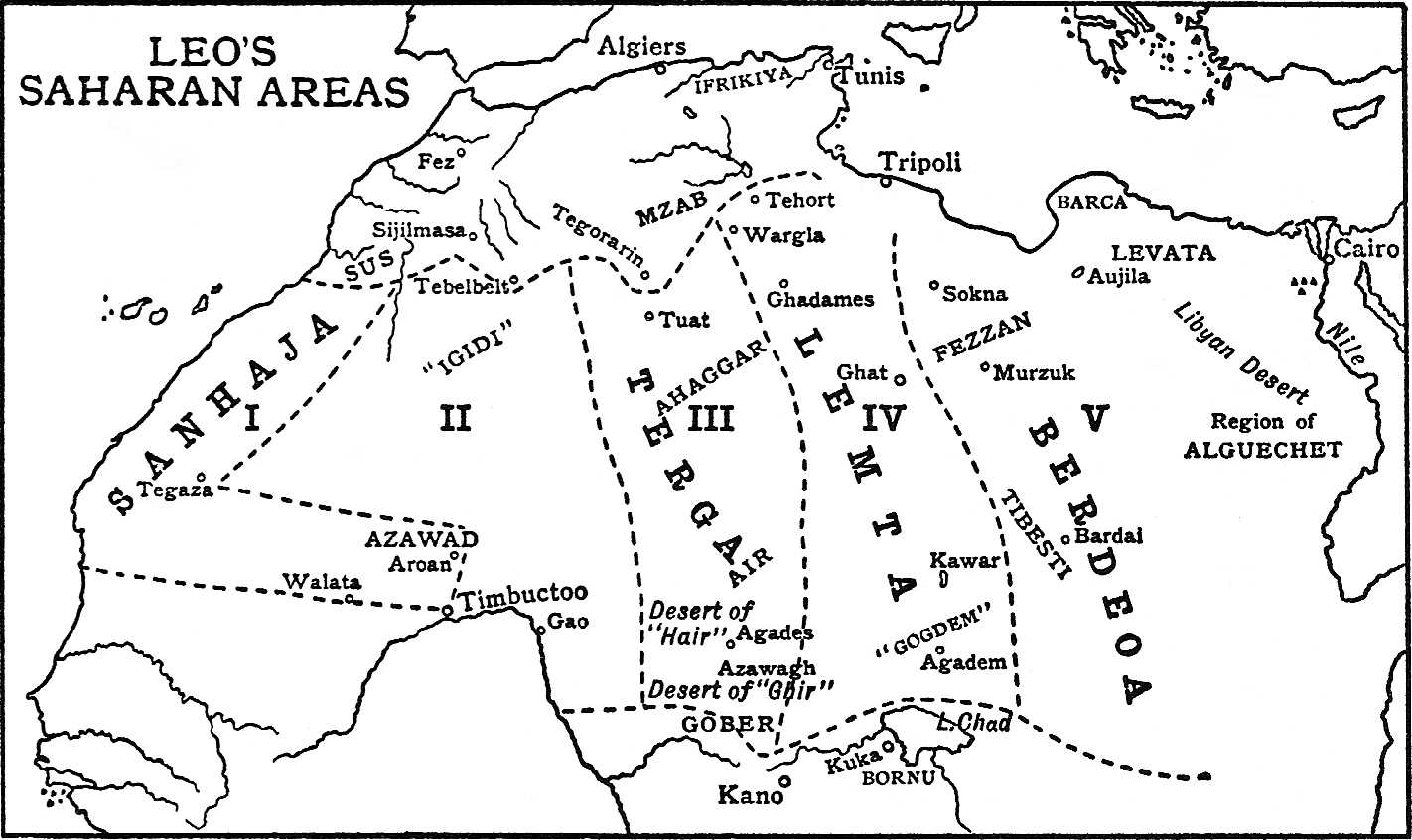

| Map showing Leo’s Saharan Areas | 331 | ||||

| Diagram showing Ibn Khaldun’s Berber Tribes | 341 | ||||

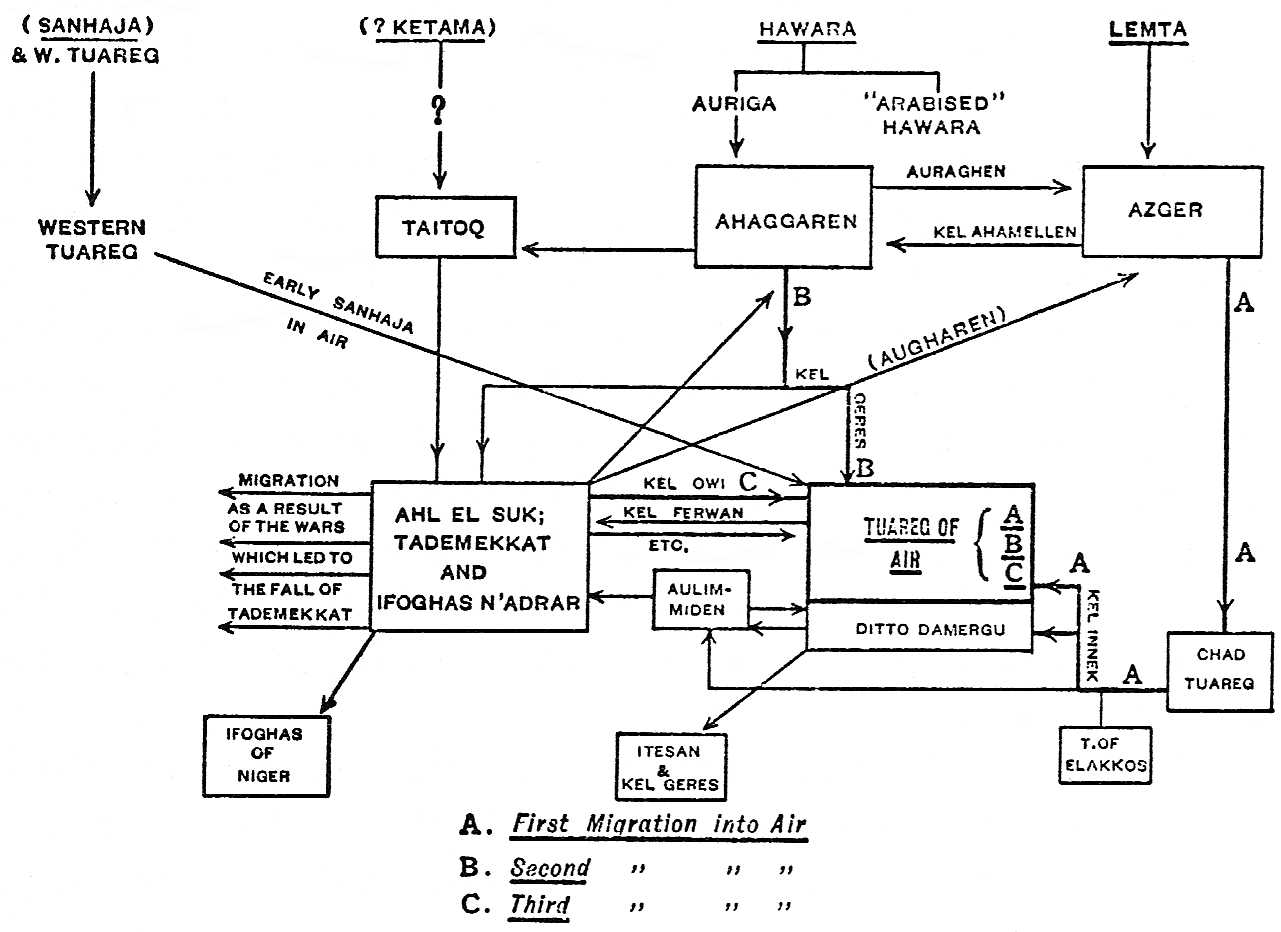

| Diagram showing the Migrations of the Air Tuareg | 388 | ||||

| Genealogy of Certain Kings of Air | 465 | ||||

| Map of Air and Adjacent Parts: 1/2,000,000 | At end | ||||

NOTE

The general map at the end of the volume was prepared by the Royal Geographical Society from data collected by the author supplementing existing maps published in France and described in the text of the book. The two drawings (Plates 38 and 39) were executed in England by T. A. Emmet from sketches made in Air. Plates Nos. 2, 15 (lower), 34 are from photographs taken by Angus Buchanan. All the other maps, diagrams, pictures, and photographs were prepared by the author from material collected in 1922.

[xvi]NOTE

The name “Air” is a dissyllable word: the vowels are pronounced as in Italian according to the general system of transliteration, which follows, wherever possible, the rules laid down by the Committee of the Royal Geographical Society on the Spelling of Proper Names. In the Tuareg form of Berber, t before i or similar vowel, especially in the feminine possessive particle “tin,” very often assumes a sound varying between a hard explosive tch and a soft liquid dental, such as is found in the English word “tune.” This modification of the sound t is written t’, wherever it is by usage sufficiently pronounced to be noticeable. The pronunciation of Tuareg words follows the Air dialect, which often differs from the northern speech. Letters are only accented where it is important to avoid mispronunciation, as in Fadé and Emilía: a final e, as in Assode, which is a trisyllable, should always be pronounced even if not accented.

The nasal n occurring in such words as Añastafidet is written ñ.

The gh (or Arabic غ, ghen) sound is, as in other Berber languages, very common in the speech of the Tuareg. The letter is so strongly grasseyé as to be indistinguishable, in many cases, from r. The French with greater logic write this sound r or r’. Doubtless many names which have been spelled with r in the succeeding pages should more correctly have been spelled with gh: such mistakes are due to the difficulties both of distinguishing the sound in speech, and of transcribing French transliterations.

No attempt has been made to indicate the occurrence of the third g which exists in the Tuareg alphabet, in addition to the hard g and the soft g (written j).

The Arabic letter ع (’ain) does not exist in the speech of the Tuareg; where they use an Arabic word containing this letter, they substitute for it the sound gh.

No signs have been used to distinguish between the hard and soft varieties of the letters d, t and z. The “kef” (Iek) and “qaf” (Iaq) sounds are written k and q.

[1]PEOPLE OF THE VEIL

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTORY

Sahara is the name given in modern geography to the whole of the interior of North Africa between the Nile Valley and the Atlantic littoral, south of the Mediterranean coastlands and north of the Equatorial belt. The word “Sahara” is derived from the Arabic, and its meaning refers to a certain type of stony desert in one particular area. There is no native name for the whole of this vast land surface: it is far too large to fall wholly within the cognisance of any one group of its diverse inhabitants. The fact that it is a Moslem area and sharply distinguished from the rest of Africa has made it desirable to find a better name than “Sahara” to include both the interior and the littoral, for even “Sahara,” unsatisfactory as it is, can only be used of the former. “Africa Minor” has been proposed, but the reception accorded to this name has not been so cordial as to warrant its use. The clumsy term “North Africa” must therefore serve in the following pages to describe all the northern part of the continent; specifically it refers to the parts west of the Nile Valley and north of the Sudan.[1] It is an area which is now no longer permanently inhabited[2] by negro races, and which is not covered by the dense vegetation of Equatoria.

To the general public the name Sahara denotes “Desert,” and the latter connotes sand and thirst and camels and picturesque men and veiled women. The Sahara in reality is very different. Its surface and races are varied. Almost every type of physical feature, except permanent glaciation, can be found. The greater part is capable of supporting animal and vegetable life in some degree. Absolute desert where no living thing can exist does not on the whole form a very large proportion of the surface. It has become usual nowadays to differentiate between the cultivated or cultivable areas, the steppe desert and the true desert. The latter alone is devoid of organic life, and is the exception rather than the rule. The mountain groups of the Sahara fall, as an intermediate category, between the cultivated and the desert lands. Generally speaking, animal and vegetable life exist in the valleys, where some tillage is often possible. The density of population, however, is never comparable with that of the cultivated districts, which, except where they fringe the coast, are usually included in the term “oases.”

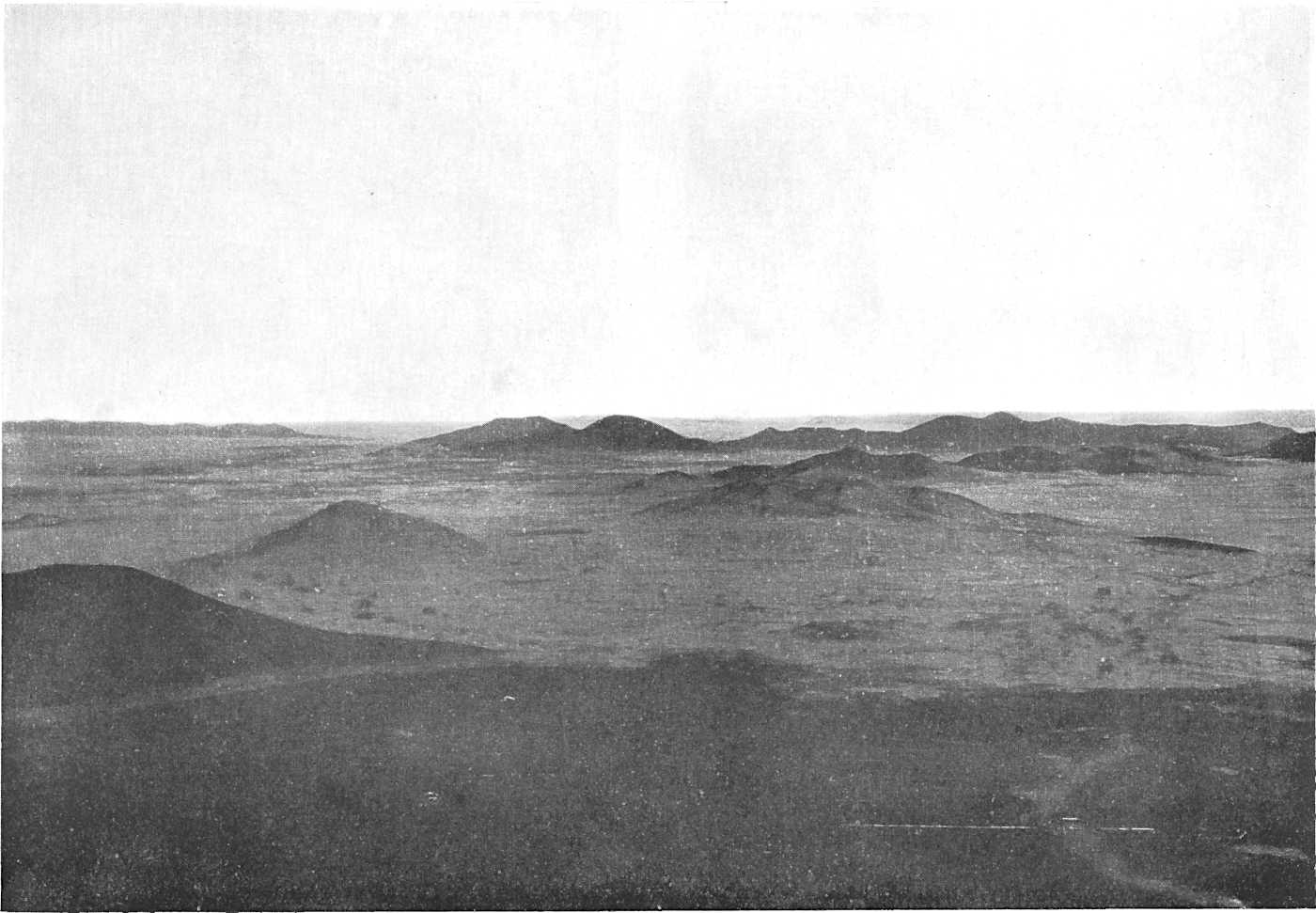

The mountain groups of the Sahara are numerous and comparatively high. There are summits in the more important massifs exceeding 10,000 feet above the sea. The three most important groups in the Central Sahara are the Tibesti, Air and Ahaggar mountains. In such a generalisation, reference to the Atlas and other mountain masses in Algeria and Morocco may be omitted, since they do not properly speaking belong to the Sahara. The three Saharan massifs are probably of volcanic origin. They have only become known in recent years, and even now have not been fully explored. This is especially the case in regard to Tibesti, an area believed to be orographically connected with Air by the almost unknown plateau of the Southern Fezzan.

The Central Sahara with these three groups of mountains differs materially from the Eastern Sahara. Although our[3] data for the latter are more limited by lack of knowledge, the structure of the surface immediately west of the Nile Valley appears characteristically to be a series of closed basins. The area is covered with depressions into which insignificant channels flow, and from which there appear to be no outlets. Compared with the river systems of the west, the stream beds are small and ill-defined. One valley of some magnitude, the Bahr Bela Ma which Rohlfs tried to find on his famous journeys in the Libyan desert, has been identified either as a dry channel of the Nile running roughly parallel to it, or alternatively as a valley which starts from N.E. Tibesti and terminates near or in the Wadi Natrun depression just west of the Nile and level with the apex of the Delta. The upper part which drains Tibesti has been called the W. Fardi; elsewhere it is the W. Fareg; the shallow depression crossed by Hassanein Bey on his journey from Jalo to Kufra seems to be part of this system. Examples of closed basins separated from one another by steppe or desert are the oases of Kufra, the Jaghbub-Siwa, Jalo and Lake Chad depressions. In these areas cultivation is frequently intense; salt and fresh water are abundant; and the vegetation sometimes develops luxuriantly into veritable forests of date palms such as exist at Kufra. Between these hollows the intervening Libyan desert is probably the largest and most sterile area of its sort in the world.

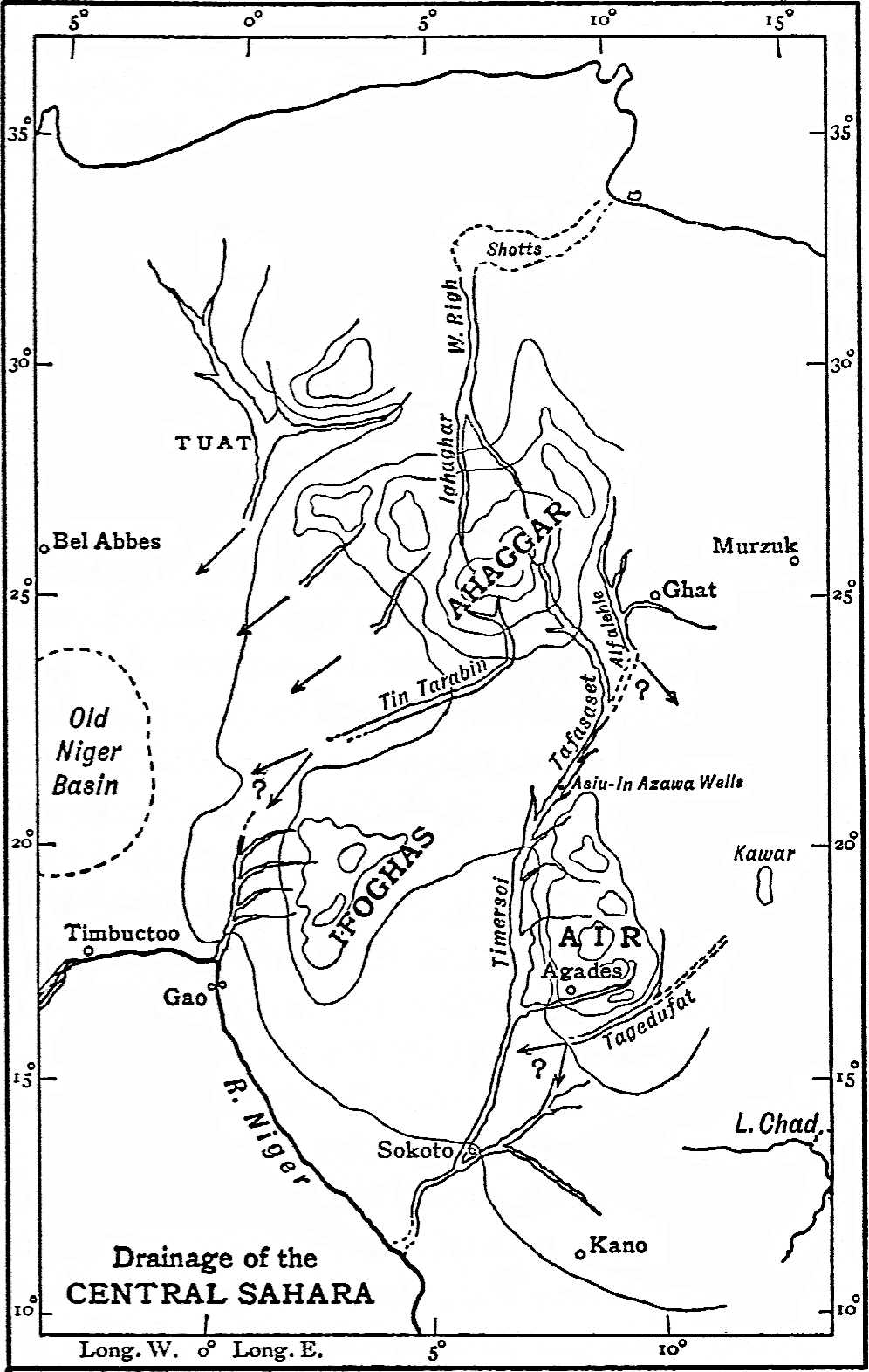

The Western Sahara, on the other hand, is essentially an area of well-defined river systems with watersheds and dry beds fashioned on a vast scale. The valleys which extend from the mountains of Ahaggar and the Fezzan to the present River Niger have corresponding channels on the other side of the water-parting running through Southern Algeria or Tunisia towards the Mediterranean. There are good reasons for believing that the original course of the Niger terminated in a swamp or marsh north of Timbuctoo, probably the same collecting basin as that west of Ahaggar into which certain rivers from the Atlas also used to flow. The lower Niger from the eastern side of[4] the great bend where the river now turns south-east and south drained the Central Sahara by a great channel which had its head-waters in Ahaggar and the Fezzan, and ran west of Air.

These Saharan rivers have not contained perennial surface water for long ages. In places they have been covered by more recent sand-dune formations of great extension, but they date from the present geological period. Associated with the desiccation of these valleys is the characteristic of extreme dryness which is one of the few features more or less in accord with popular conceptions of the Sahara. The barrenness of the Sahara is less due to the inherent sterility of the ground than to climatic conditions; desiccation has been intensified in the course of centuries by the purely mechanical processes attendant upon an extremely continental climate and excessively high day temperatures. The latter combined with the extraordinary dryness of the air have contributed to the decay of vegetable, and consequently of animal, life wherever man has not been sufficiently powerful, in numbers or energy, to stay the process. Sterility and desiccation are interacting causes and effects. There is no reason to believe that any sudden change of climate has taken place in the Sahara since the neolithic period, or that it is very much drier now than two thousand years ago. Maximum and minimum temperatures, both average and absolute, have a very wide range seasonally and within the period of twenty-four hours. Temperatures of over 100° F. in the shade are common at all seasons of the year during the day: the thermometer frequently falls to freezing point at night during the winter. Ice is not unknown in the mountains of Tibesti, Air and Ahaggar. The rainfall is irregular except within the belt of summer rains which are so characteristic of Equatorial Africa. In Tibesti the cycle of good rains seems to recur once in thirteen years: in many years both here and elsewhere in the Sahara no rain falls at all. But with these adverse climatic conditions the surprising fact remains, not that the Sahara is so barren, but that it is[5] so relatively well-favoured and capable of supporting different races of people in such comparatively large numbers.[2]

The Air mountains, like the Desert steppes, are only sparsely inhabited. The hill-sides are too wind-swept and rocky to support forests or pastures of any value. Many of the valleys are capable of being cultivated, but in practice are only gardened here and there. In certain districts there are groves of date palms which have been imported from the north. Air is in reality a great Saharan oasis divided from the Equatorial belt by a zone of desert and steppe. It differs from the south in its flora and general conditions, though by its position within the belt of tropical summer rains it belongs climatically to the Sudan.

The oases of the desert, like the Sahara generally, have been the subject of much popular misconception. The[6] origin of the word “oasis,” which has reached us in its present form through the classics, may perhaps be found in ancient Egyptian. It seems to be connected with the name of the Wawat People of the West referred to in the Harris Papyrus,[3] and occurs in the names of Wau el Kebir and Wau el Seghir or el Namus, which are oases in the Eastern Fezzan.[4] The term El Wahat,[5] given to one or several of the oases west of the Nile Valley, contains the same root. An oasis is not necessarily a patch of ground with two or three palm trees and a well in the desert. It is simply an indefinite area of fertility in a barren land; it may or may not happen to have a well. There are oases in Southern Algeria and the Fezzan with hundreds of thousands of palm trees, containing many villages and a permanent population. There are others where the pasture is good but where there is neither population nor water. “Oasis” is a term with no strict denotation, it connotes attributes which render animal life possible.

In this sense Air, as a whole, is an oasis situated on a great caravan road from the Mediterranean to Central Africa. The mountains so lie in respect of the desert to the north and to the south that caravan journeys may be broken in their valleys, and camels can stay to recuperate. The mountains mark a stage on the road, the importance of which it is difficult to over-estimate. In the history of North Africa, the principal routes across the Sahara from the Mediterranean to the Sudan have seemingly not changed at all. Since the earliest times they have followed the shortest tracks from north to south whenever there was sufficient water. If the Nile Valley and the routes in the desert adjacent thereto are left out of account as being suorum generum, there are four main caravan roads across North Africa from north to south. The easternmost runs from Cyrenaica by Kufra[7] to Wadai and Tibesti; only within the last century has it been rendered practicable for caravans by the provision of wells along the southern part, which was opened to heavy traffic by the Senussiya sect. The two central routes run respectively from Tripolitania by the Fezzan, Murzuk and Kawar to Lake Chad, and by Ghadames, Ghat and Air to the Central Sudan. The western route runs from Algeria and Morocco across the desert to Timbuctoo. In addition there is the Moroccan road, which roughly follows the curve of the coast to the Western Sudan and Senegal. Of all these the best known in modern times,[6] and culturally perhaps the most important, has been the Air road. It is noteworthy that all three central routes have been or are within the control of the Tuareg race. As the Tuareg were the caravan drivers of the Central Sahara, so were they also responsible for bringing a certain degree of civilisation from the Mediterranean to Equatorial Africa. That has been their greatest rôle in history.

The object of this book is to describe a part of the Tuareg race, namely, those tribes which live in Air and in the country immediately to the south. It will not be possible to examine in any detail the theories surrounding the origin of the race, but certain definitions are necessary if the succeeding chapters are to be understood. The Berbers of North Africa, among whom are usually included the Tuareg, have very disputed origins; for many reasons it is perhaps best to follow the example of Herodotus and use the geographical term Libyans for them. Less controversy surrounds this name than “Berber,” which implies a number of wholly imaginary anthropological connections. Moreover, it is even open to doubt whether the Tuareg are Berbers at all, like the other people so called in Algeria and Morocco. In all this confusion it will be enough to grasp that the Tuareg are a Libyan people with marked individual peculiarities and that they were in North Africa long before the Arabs came. They have been there ever since the earliest times of which we[8] have any historical record, though in more northern areas than those which they now occupy. The population of the Sahara is very diverse and the affinities of the various elements afford many interesting problems for study; but in the present work we shall be concerned with the one race alone.

The Tuareg country may roughly be described as extending from the eastern edge of the Central Sahara, which is bounded by the Fezzan-Murzuk-Kawar-Lake Chad caravan road, to the far edge of the western deserts of North Africa before the Atlantic zone begins, and from Southern Algeria in the north to the Niger and the Equatorial belt between the river and Lake Chad in the south. The Tuareg are so little known even to-day that their very existence is almost legendary. It is with something of a thrill that the tourist in Tunis or Algiers learns from a mendacious guide that a poor Arab half-caste sitting muffled in a cloak is one of the fabled People of the Veil. It is long, in fact, since any of them have visited the Mediterranean coast, for they do not care for Europeans very much. Before the Italo-Turkish War, occasional Tuareg used to reach the coast at Tripoli at the end of the long caravan road from Central Africa; even then they more usually stopped at Ghadames or Murzuk. With the Italian occupation of Tripolitania in 1913 they became apprehensive of intrusion on their last unconquered area; but despite the Italian failure to occupy and administer the interior they have only lately ventured a certain way north once more on raids or for commerce.

Though the Hornemann, Lyons and the Denham, Oudney and Clapperton expeditions in the first half of the last century touched the fringe of the Tuareg country, the first Europeans in modern times to come into contact with the Azger group in the Fezzan were Richardson in 1847 and Barth with Richardson in 1849 and subsequent years. Barth, more particularly mentioned in the story of the penetration of Air, is in some respects even now the most valuable authority for all the Tuareg except the Ahaggaren. The first detailed work of value dedicated to the latter was that of Duveyrier,[9] Les Touareg du Nord, published in 1864 after a journey through the Ahaggar and Azger country and the Fezzan. His systematic study of the ethnology of the Tuareg, his geographical work and his researches into the fauna, flora and ancient history of the lands he visited, were presented to the world in a form which has since been taken in France as the model of what a scientific book should be. Ill health was the tragedy of his life, for it prevented his return, and rendered him, as he remarked in later years, “an arm-chair explorer of the Sahara.” After visiting the Wad Righ and Shott countries in Southern Tunisia, he went to El Golea on the road to Tuat and thence turned towards Ghadames and Tripolitania. He eventually reached Ghat, and returned to the Mediterranean coast by Murzuk and Sokna, taking a more easterly road than Barth’s in 1850. Beurmann in 1862, and Dickson ten years previously, had reached the edge of the same Tuareg country, but what Barth had done for the Tuareg of Air and the south, Duveyrier did for the Ahaggaren and Azger.

In 1881, twenty years after the expedition of Burin to Tuat, the French determined to penetrate the countries of this fabled race. A column under Colonel Flatters, who had already gained a certain reputation in France as a Saharan explorer, marched almost due south from Wargla and Tuggurt in the eastern part of Southern Algeria up the Ighaghar basin and so reached the north-eastern corner of the Ahaggar country. This valley is the drainage system of the north central Sahara towards the Mediterranean; it virtually divides the old Azger country from that of the Ahaggaren. Near the Aghelashem Wells at the intersection of the valley with the Ghat-Insalah road, Flatters turned S.E., intending apparently to follow the Ghat-Air caravan road to the Sudan. This track he proposed joining at or near the wells of Issala, and then to proceed by much the same route as that which Barth and his companions had selected in 1850. But at Bir Gharama in the Tin Tarabin valley, a few days before it was due to reach Issala, disaster overtook[10] the column. The European officers, who assumed that their penetration of the Tuareg country was welcome to the inhabitants, had taken none of the military precautions necessary in hostile country. The vital part of the expedition, the officer commanding and his staff, left camp to reconnoitre a well and became separated from their troops, consisting of about eighty Algerian tirailleurs. The officers were attacked by the Tuareg and killed. After the death of Colonel Flatters and Captain Masson, the remainder of the column under Captain Dianous made an attempt to escape north. After an unsuccessful effort by the Tuareg to destroy the party by selling the men dates poisoned with the Alfalehle plant (Hyoscyamus Falezlez),[7] the column reached the Ighaghar once more at the wells of Amjid. But they found the wells occupied by the enemy, and in the ensuing fight Captain Dianous and nearly all his men were killed.

The circumstances of the disaster, so vividly recounted by Duveyrier to the Paris Geographical Society on 22nd April, 1881, had followed the publication of his account of a people whom he had described picturesquely, but with some exaggeration, as the “Knights of the Desert.” The massacre created a profound impression in France. The Tuareg came to be regarded as an insurmountable obstacle to the French penetration of North Africa, and expeditions into their country were discontinued. The disaster of Bir Gharama remained unavenged until 1902, when a detachment of Camel Corps under Lieut. Cottonest met the pick of the Ahaggar Tuareg in battle at Tit within their own mountains and killed 93 men out of 299 present, the French patrol losing only 4 killed and 2 wounded out of 120 native soldiers and Arab scouts. Despite the small numbers involved, the fight at Tit broke the resistance of Ahaggar, for it proved the vanity of matching a few old flintlocks and spears and swords against magazine rifles.[8] But if it demonstrated[11] the futility of overt resistance, it also established for all time the courage of the camel riders of the desert, who hurled themselves against a barrier of rifle fire, unprotected by primeval forest or sheltering jungle, in order to maintain their age-long defiance of the mastery of foreign people.

Considering the magnitude of the results they achieve, Saharan, like Arabian, battles involve surprisingly small numbers. The size of armed bodies moving over the desert is limited by the capacity of the wells; the output of water not only regulates the mass of raiding bands, but also determines their strategy, as well as the routes of trading caravans, which are compelled to move in large bodies in order to ensure even a small measure of protection. Only the realisation of this rather self-evident fact enabled the French in the course of years to deal with raiders in Southern Algeria by organising Camel Corps patrols of relatively small size and great mobility. The privations which these raiders are willing to endure made it impossible to fight them with a European establishment.

The necessity of imitating the nomad in his mode of life and warfare became obvious to Laperrine from his first sojourn in Southern Algeria, where he made his career as the greatest European desert leader in history with one solitary exception. The encounter of Tit was followed by a number of “Tournées d’Apprivoisement,” patrols to “tame” the desert folk, initiated by Laperrine, and culminating in 1904 in a protracted reconnaissance through Ahaggar, which brought about a final pacification. Charles de Foucauld, soldier, traveller and monk, had accompanied the patrol. He remained on after it was over as a hermit and student among the Ahaggaren until his death in 1916. He had been Laperrine’s brother officer at St. Cyr. Extravagant, reckless and endowed with all the good things of the world, a member of the old French aristocracy in a smart cavalry regiment, the Marquis de Foucauld is one of the most picturesque figures of modern times. After a memorable reconnaissance of Morocco in 1883-4, disguised as a Jew,[12] he became a Trappist monk, and eventually entered a retreat at Beni Abbes, in the desert that he loved too well to leave in all his life. During his years in Ahaggar as a teacher of the Word of God he made no converts to Christianity, but sought by his example alone to lead the people along the way of Truth. It is to be hoped that, in spite of a modesty which precluded it during his lifetime, the knowledge and lore of the Tuareg which he collected in the form of notes will eventually be given to the world in order to supplement his dictionary of the Ahaggar dialect, to-day the standard work on their language, which is called Temajegh.[9]

To implement the Laperrine policy of long reconnaissances, a post was built near Tamanghasset in Ahaggar called Fort Motylinski, after an officer interpreter who was one of the first practical students of Temajegh. Lately the post has been moved to Tamanghasset itself, where Father de Foucauld had built his hermitage, and it is now called Fort Laperrine, in memory of the great soldier who was killed flying across the desert to Timbuctoo in 1919.

Another post was built at Janet not far from Ghat, to watch the Azger Tuareg. Its capture during the late war by the Arabs and Tuareg of Ghat, and the killing of Father de Foucauld by a raiding party from the Fezzan, are incidents in that same series of intrigues which were instigated in North Africa by the Central Empires and carried on with such success in the Western Desert of Egypt, Cyrenaica, Tripolitania, Southern Algeria and as far afield as Air. If the Senussi leaders have not been responsible for as many intrigues as it has been the fashion to ascribe to this puritanical and perhaps fanatical sect, the Germans at least discovered what others are still learning, that the latent force of nationalism in North Africa among the ancient Libyan and Arab-Libyan peoples is powerful still to-day. The spirit of the Circumcelliones and of the opponents of Islam in the eighth[13] century was exploited by the Turks and Germans through the Senussiya, which provided the only organisation available during the Great War, though in fact only few Tuareg and Arabs at Ghat or in the Fezzan were members of, or even friendly to, the sect. These people used the opportunity afforded by the war to procure arms and material through the Senussiya for the consummation of their own ambitions. The new spirit which is abroad in Islam, in Africa as well as in Asia, is an interesting subject of study for the practical politician. There is no occasion to enlarge upon it here.

In consequence of these agitations, a raid came out of the east and fell upon Father de Foucauld’s hermitage on the 1st December, 1916. The hermit was killed, but the raiders were not of the Ahaggaren among whom he had lived, and to whom he had devoted his life; they came from Ghat and the Fezzan. They probably started without intent to murder, but because Charles de Foucauld was the greatest European influence in the desert at that time, they desired to remove him and perhaps to hold him as a hostage. In justice it must be admitted that no one had any illusions regarding the political views of the people of the Fezzan; they were in a state of open warfare with the French posts in Southern Algeria. De Foucauld had played a very great part against them in preventing the Ahaggaren rising en masse against the French; he was an important intelligence centre for the neighbouring Fort Motilynski; he was apparently, well provided with rifles in his hermitage. When surprised by the raid, he disdained to fight, preferring to fall a martyr to his religion and his country. My excuse, if any is needed, for touching on a subject tending to be controversial is the appearance of a number of mis-statements concerning the barbarity of his murder and the treachery of the people to whom Father de Foucauld had devoted the latter part of his life. It is well to remember, in the first place, that the circumstances of his life and his prestige made the attack a justifiable act of war, for he played a definitely political rôle; secondly, that there was[14] no treachery or betrayal; and lastly, that his aggressors were a mixed band of Arabs and of Tuareg from another part of the Sahara which had, for generations past, been on terms of raid and counter-raid with the people of Ahaggar.

When all has been said of the European penetration of the Tuareg country, it is not very much. The world outside the society of those white men who, during the last fifty years, have spent their lives in the Sahara, can know but little of this race or of their country. The modern literature on the subject is small, even in French; in English it is almost non-existent. On the Tuareg of Air there are only two works of any value: the one by a French officer is recent in date and sadly superficial;[10] the other is incorporated in H. Barth’s account of the British expedition of 1849 and subsequent years to Central Africa.[11] There are a few other works in French about the Tuareg of the north and south-west, but I am not aware that anyone has attempted a general study of the whole people, who have been rather neglected by science. The principal object of this volume will have been achieved if it in any measure fills a want in English records or if it arouses sufficient controversy to induce others to undertake a thorough investigation of the race.

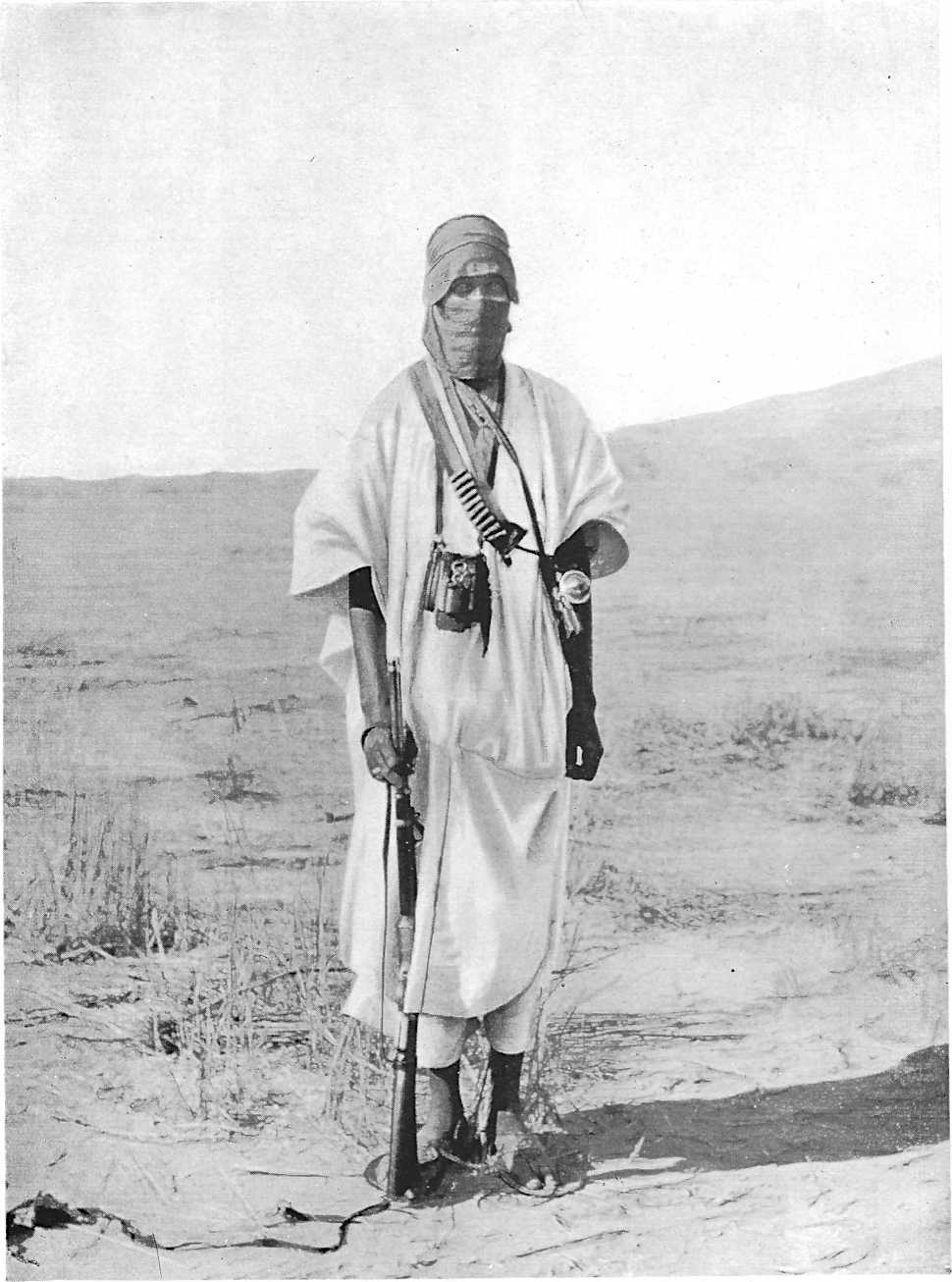

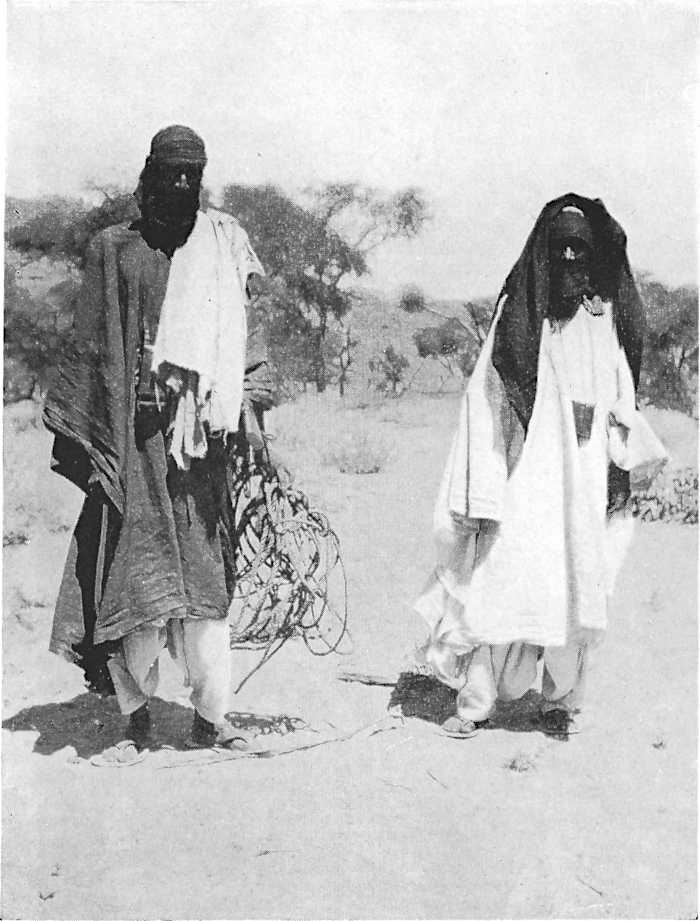

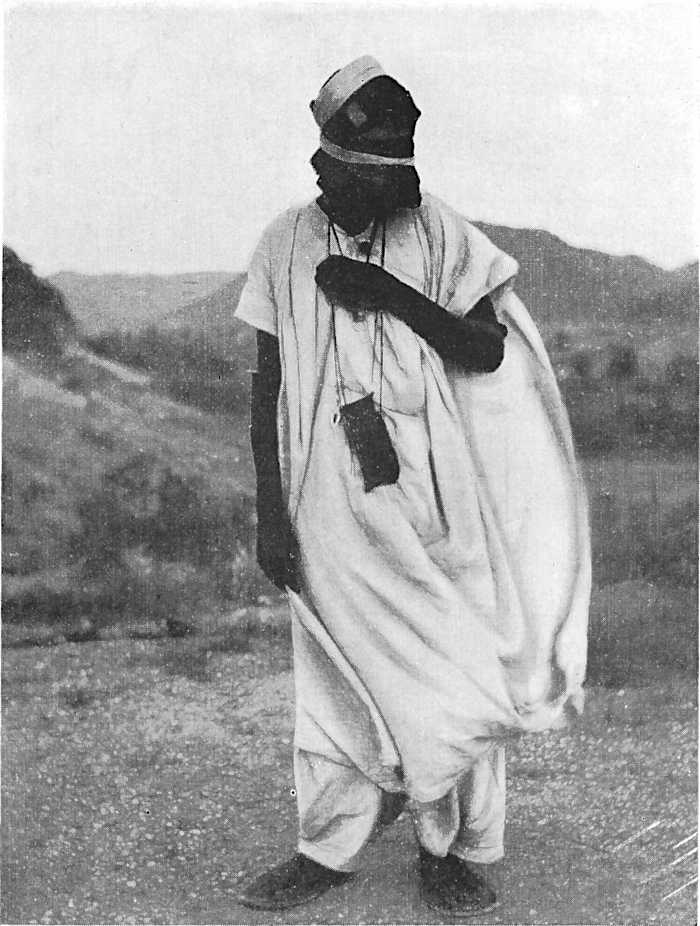

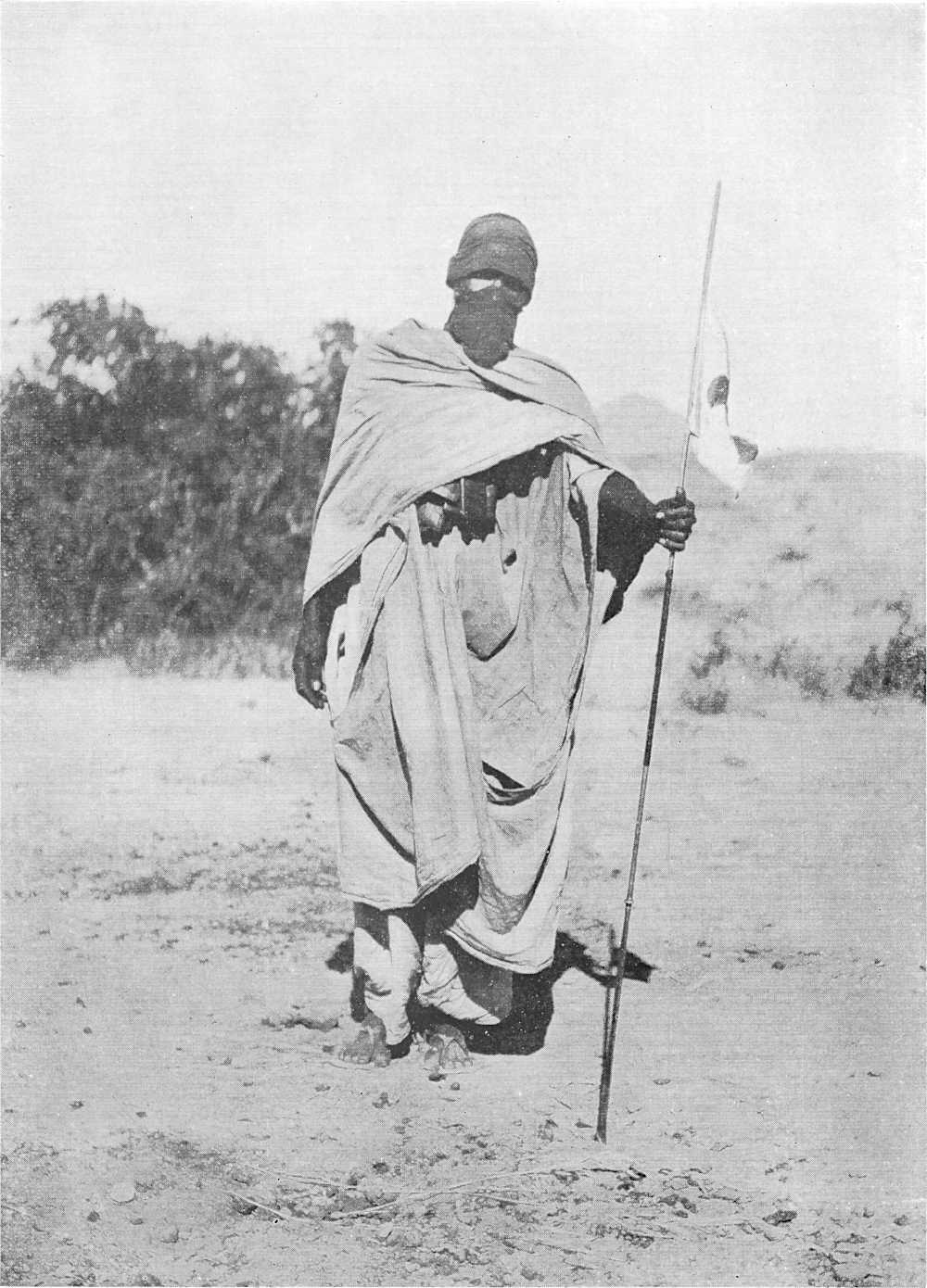

The Tuareg are not a tribe but a people. The name “Tuareg” is not their own: it is a term of opprobrium applied to them by their enemies, and connotes certain peculiarities possessed by a number of tribal confederations which have no common name for themselves as a race. The men of this people, after reaching a certain age, wear a strip of thin cloth wound around their heads in such a manner as to form a hood over the eyes and a covering over the mouth and nostrils. Only a narrow slit is left open for the eyes, and no other part of the face is visible. From this practice they became known to the Arabs as the “Muleththemin”[15] or “Veiled People,”[12] while they themselves, in default of a national name, are in the habit of using the same locution in their own tongue to describe the whole society of different castes which compose their community. Whatever the social position of the men, the Veil is invariably worn by day and by night,[13] while the women go unveiled. Few races are more rigidly observant of social distinction between noble and servile tribes; none holds to a tradition of dress with more ritual conservatism.

The larger divisions of Tuareg have names by which they are known to themselves and to their neighbours: these names designate the historical or geographical groupings of tribes. In each group of tribes the existence of nobles and serfs is recognised; there are appropriate terms to describe these social distinctions. The nobles are called Imajeghan;[14] the servile people, Imghad. But no name other than Kel Tagilmus,[15] the “People of the Veil,” exists to describe the society of nobles and serfs alike, irrespective of group or caste. These details will require fuller examination in due course, but it is important to realise immediately that the name Tuareg[16] is unknown in their own language and is only used of them by Arabs and other foreigners. It has, however, been so universally adopted by everyone who has had to do with them or who has written of them that, although not strictly accurate, it would be pedantic not to continue using it. The Tuareg all speak the same language, called Temajegh, which varies only dialectically from group to group. They have a peculiar form of script, known as T’ifinagh, which also is practically identical in all the[16] divisions of the Tuareg, but is apparently not used by other peoples. Lastly, the Tuareg are nomads by instinct and, save where much intermarriage has taken place, of the same racial type. The conquest of foreign elements in war and their assimilation into servile tribes have, in the course of time, led to some modification of physique and a growth of sedentarism in certain areas. As a whole, however, the nation has survived in a fairly pure state which is readily distinguishable. There is, I think, no justification for considering the People of the Veil a large tribal group of Berbers in North Africa; they are a separate race with marked peculiarities, distinct from other sections of the latter, and, as I believe, of a different origin.

They formerly extended further west almost to the sea-board of the Atlantic; their northern and eastern extension can also be deduced from what is known of their migrations. Their neighbours to the south are the negroid Kanuri, Hausa-speaking peoples,[17] and the Fulani; to the east are the Tebu, and in the west the Arab and Moorish tribes; finally, in the north the nomadic and sedentary Arabs and sedentary Libyans of Algeria, Tunisia and Tripolitania. The N.E. corner of Tuareg territory, the Fezzan, is ethnically of such mixed population as to admit of no summary classification; Arab, Libyan, Tebu and negroid peoples are all inextricably mingled together. The Tuareg wander as nomads over the country generally, the negroes and sedentary Libyans till the ground, and, in addition to a proportion of all those already enumerated, the towns are inhabited by yet another people of noble origin, whose connection with the ancient Garamantes of classical authors may be assumed if it cannot be proved. With the exception of the Fezzan the Tuareg are now predominant within their own country. It includes two great groups of mountains, Air and Ahaggar, together with certain smaller adjacent massifs.

[17]It is unfortunately not possible to deal with Air in history nor with the Tuareg of Air, by considering the mountains and their inhabitants alone. The migrations of the Tuareg of Air have been so intimately connected with that part of the Sudan which we now call Nigeria that the northern fringe of the area and the country intervening between it and Air must receive attention. This intervening steppe and desert, largely overrun by Tuareg, lie on the way which I followed to reach the mountains. The neglect to which these areas have been subjected justifies me in devoting a chapter to them before coming to Air itself. Again, the concluding chapters of this volume will deal as much with the Southland as they do with Air, for the history of the latter cannot be divorced from that of the former.

Since mention will be continually made of the various Tuareg groups as they exist to-day, and of the tribes which they contain, it will be as well to explain that there are to-day four principal divisions of the people, all of whom possess characteristics common and peculiar to the whole race.

The main groups are:—

| 1. | The People of Ahaggar, called Ahaggaren, or Kel Ahaggar. |

| 2. | The Azjer, or Azger Tuareg; this name is also spelt Askar, Adjeur, etc. |

| 3. | The People of Air called the Kel Air, or, in the Hausa language which is current in that country, Asbenawa or Absenawa, from Asben, Azbin or Absen, the Sudanese name for Air. |

| 4. | The Tuareg of the south-west. |

The first group is held for convenience to include the Tuareg in the Ahnet mountains, the Taitoq, and those north-west of the Ahaggar mountains. The second group is comparatively compact. The third group is the one with which this volume deals in detail, and includes the Kel Geres and other Tuareg generally of the Southland, in and[18] on the fringes of Nigeria. The fourth group should more properly be divided, as it comprises the distinct aggregations of the Aulimmiden, the Ifoghas of the Mountain (Ifoghas n’Adghar),[18] and the Tuareg of Timbuctoo and the Niger.

The country of the Ahaggaren proper is confined to the Ahaggar massif, but there are certain outlying districts to the north and north-west. The confused mass of hills east of Ahaggar towards the Fezzan was, at the beginning of the century, essentially the country of the Azger. In recent years they have tended to move eastwards towards their original homes and away from the influence of the French military posts. The majority of this group now ranges over the country between Ghat and Murzuk. They are the Tuareg who have come least into contact with Europeans. Although there is considerable affinity between them and the Ahaggaren, the Tuareg generally recognise that the Azger do not belong to, or are under the rule of, the Ahaggar chieftains despite the fact that they are all collectively known in Air as Ahaggaren. Those travellers who have known them are at one in considering them to-day an independent division. From the historical point of view the Azger are the most important of all the Tuareg, since from this group, reduced in numbers as it now is, most of the migrations of the race to the Southlands seem to have taken place. They are also probably to-day the purest of the Tuareg stock in existence.

The first description of Air and its people in any detail was brought back to Europe by Barth after his memorable journey from the Mediterranean to the Sudan, on which he set out in 1849 with Richardson and Overweg, but from which he alone returned alive more than five years later. Prior to this journey there are certain references in Ibn Batutah and Leo Africanus, but they do not give us much[19] information either of the country or of the people. From Ibn Batutah’s description, the country he traversed is recognisable, but the information is meagre. The account of Leo Africanus written in the sixteenth century is little better. His principal contribution, in the English and original Italian versions, is a bad pun: “Likewise Hair (Air), albeit a desert, yet so called for the goodness and temperature of the aire. . . .”[19] It is an observation, in fact, of great truth, but hardly more useful than his other statement, which records that the “soyle aboundeth with all kinds of herbes,” in apparent contradiction with the previous remark. He adds that “a great store of manna” is found not far from Agades which the people “gather in certaine little vessels, carrying it, when it is new, into the market of the town to be mingled with water as a refreshing drink”—an allusion probably to the “pura” or “ghussub” water made of millet meal, water and milk or cheese. He states that the country is inhabited by the “Targa” people, and as he mentions Agades, it had evidently by then been founded, but beyond these facts his description is wholly inadequate. He unfortunately even forgets to mention that Air is mountainous.

Although the European penetration of the Western Sahara may date from the Middle Ages, the same cannot be said of Air. Caillé in 1828 was, in fact, not the first European to visit and describe Timbuctoo, nor was Rohlfs in 1864 the first European in Tuat. There are some very interesting earlier accounts which are gradually being unearthed[20] dealing with these countries. It is regrettable that there are apparently no similar accounts of Air.[21] The first information of any value is found only in comparatively recent times. Hornemann[22] in 1798 travelled from Egypt along[20] the Haj Road which runs from Timbuctoo to Cairo. He turned back at Murzuk, but had he continued he would have come to Ghat and eventually to Air. He nevertheless brought back the first modern account of the Tuareg of this country, or rather of a section of them, the Kel Owi, whom he calls the Kolouvey. His information about the Ahaggaren and about the divisions of the Tebu, who lived east and north-east beyond the limits of the country which they now occupy, is worth examining in connection with their ethnological history. After Hornemann’s journey Denham, Oudney and Clapperton[23] collected some further details about Air and its people in the course of an expedition to Chad and Nigeria at the beginning of the last century, and in 1845 Richardson began a systematic study of the Azger and Air Tuareg during a preliminary journey to the Fezzan. But none of these travellers had the first-hand personal experience which, five years afterwards, Barth, Richardson and Overweg obtained on their expedition.

The part played by Great Britain in the exploration of the Central Sahara, testified to by the graves of many Englishmen or foreigners in the service of the British Crown, is little known in this country. Our efforts to abolish the slave trade in Africa and our paramount position in Tripolitania early in the last century led to that initiative being taken, to which the world even to-day owes most of its knowledge of the Fezzan, and which opened the Sudan to commerce and colonisation. While Richardson was apparently the first and only Englishman to visit Air until my travelling companion, Angus Buchanan, went there from Nigeria in 1919, the graves of explorers in neighbouring lands show that we stand second to none in geographical work in the Central Sahara. It was only when, in the partition of North Africa, this vast area fell to the French, that there was any falling off in the numbers of Englishmen who in each successive decade travelled and died there. Their work deserves to be better[21] known: Henry Warrington died of dysentery at the desert well of Dibbela, south of Bilma in Kawar, on his way to Lake Chad with a German, Dr. Vogel. Dr. Oudney died on 5th January, 1824, at Murmur near Hadeija (Northern Nigeria), after accompanying Clapperton and Denham from Tripoli by way of Bilma and Chad to explore Bornu. Tyrwhit, who went out to join them, died at Kuka on Lake Chad, on 22nd October, 1824. Barth’s companion Richardson died in the early part of 1851 at N’Gurutawa in Manga, S. of Zinder, and their companion Overweg succumbed near Lake Chad. Both Barth and Overweg were Germans who had volunteered and were appointed to serve on an expedition sent by Her Majesty’s Government to explore Central Africa and to report on the abolition of the slave trade. Dr. Vogel, another German, who had been sent by Her Majesty’s Government to join Barth and complete his work, died near Lake Chad after his return, while an assistant, Corporal MacGuire, was killed on his way home at Beduaram, N. of Bilma, in the same year. Of those who had opened the way for the Clapperton expeditions, Ritchie had died of disease in 1819 at Murzuk and Lyon had been obliged to turn back before reaching Bornu. Clapperton himself on a second journey lost his life at Sokoto on 13th April, 1827. North Africa has claimed her British victims no less than the swamps and jungles of Equatoria, only they are not so well known, for they never sought to advertise their achievements.

Few people in this country or abroad realise how great was the influence of Great Britain in the Sahara during the lifetime and after the death of that remarkable man, Colonel Hamer Warrington, H.M. Consul at Tripoli from 1814 to 1846. Apart from the fact that he virtually governed Tripoli, our influence and interests may be gauged by the existence of Vice-Consulates and Consulates, not only along the coast at Khoms and Misurata, but far in the interior at Ghadames and Murzuk. The peregrinations of numerous travellers and efforts to suppress the African slave trade had[22] obliged Her Majesty’s Government to play a part in local tribal politics, for it had early become clear that if this abominable traffic was to be abolished the sources of supply would have to be controlled, since it proved useless only to make representations on the coast where caravans discharged their human cargo. At one moment it even seemed as if Tripolitania would be added to the British Empire, and as lately as 1870 travellers were still talking of the French and British factions among the Fezzanian tribes. But Free Trade and other political controversies in England half-way through the century brought about a pause, and the arrest was enough to withdraw public interest from North Africa and to give France her chance. The controversies were the object of much bitter criticism by the idealist Richardson, who saw political dialectics obscuring a crusade on behalf of humanity for which he was destined to give his life. He seems to have been profoundly affected and to have suffered himself to become warped, as Barth on more than one occasion discovered.[24] The inevitable consequence of a British occupation of Tripolitania would have been the active penetration of the Air and Chad roads and a junction with the explorers and merchants who were working north from the Bight of Benin. But French interest in North Africa as a consequence of their occupation of Algeria grew progressively stronger as it declined in this country, while to the same waning appetite must be ascribed the fact that for seventy years no Englishman visited Air. Regrettable as this may appear to geographers, it is even more tragic to realise how few have heard of the German, Dr. Heinrich Barth, than whom it may be said there never has been a more courageous or meticulously accurate explorer. After several notable journeys further north he accompanied Richardson as a volunteer, and on the latter’s death continued the exploration of Africa for another four years on behalf of Her Majesty’s Government, which he most loyally served.[23] If in this volume he is repeatedly mentioned, it is without misgiving or apology; it may help in some little measure to rescue his name from unmerited oblivion in these days of sensational and superficial books of travel. The account of his journey and of the lore and history of the countries of Central Africa which he visited from Timbuctoo to Lake Chad is still a standard work.

Barth and his companions entered Air in August 1850, and left the country for the south in the closing days of the same year. Reaching Asiu from Ghat, they traversed the northern mountains of Air, which are known to the Tuareg as Fadé.[25] After passing by the wells in the T’iyut valley and the “agilman” (pool) of Taghazit, they camped eight days later on the northern outskirts of Air proper. During this period their caravan was subjected to constant threats of brigandage from parties of northern Tuareg, and on the day before reaching the first permanent habitations of Air in the Ighazar near Seliufet village, they again narrowly escaped aggression from the local inhabitants. An attack was eventually made on them at T’intaghoda, a little further on, and they only just escaped with their lives after losing a good deal of property. The same experience was repeated near T’intellust, where the expedition had established its head-quarters in the great valley which drains the N.E. side of the Air mountains. When, however, they had once made friends with that remarkable personality, Annur, chief of the Kel Owi tribal confederation, and paramount chief of Air, they were free from further molestation, and thanks to him eventually they reached the Sudan in safety. From T’intellust Barth made a journey alone to Agades by a road running west of the central Bagezan mountains. After his return the whole party moved to the Southland along the great Tripoli-Sudan trade route which passes east of the Central massifs. Crossing the southern part of Air known as Tegama they entered Damergu, which geographically belongs to the Sudan, about New Year’s Day, 1851. In the course of[24] his stay in Air Barth made the first sketch map of the country, catalogued the principal tribes and compiled a summary of their history which is still the most valuable contribution which we possess on the subject.

Some twenty-seven years later, another German, Erwin von Bary, reached Air from the north by much the same road as that which Barth and his companions had followed. He left Ghat in January 1897 and reached the villages of Northern Air a month later. Thence he journeyed to the village of Ajiru, a village on the eastern slopes of the central mountains, and awaited the return from a raid of Belkho, the chieftain who had succeeded Barth’s friend Annur as paramount lord of the country. The unfortunate von Bary was subjected to every form of extortion, and though Belkho, when he returned, compelled his people to restore what they had stolen, the chief himself made life unpleasant for the traveller by taking all his presents and doing nothing for him in return so long as he showed any desire to proceed on his journey southwards. Belkho pleaded such poverty that the explorer nearly died of starvation, but von Bary admittedly had laid himself open to every form of abuse. He had arrived almost penniless, did not understand the courtesies of desert travelling, and seems to have placed undue reliance on his skill as a doctor to achieve his objects. But when he eventually gave up the idea of going on to the Sudan, Belkho treated him well. Although von Bary’s opinion of the Tuareg of Air is not favourable, in reality he owed them a great debt of gratitude. No other people who dislike foreigners so much as they do would have protected him and helped him as they finally did. His quarrels with Belkho seem to have been in part due to his own tactlessness and discourtesy, and in part to his inability to realise that the chief, for political reasons, did not desire him to go to the Sudan. Von Bary returned to Ghat, meaning to try once more to reach Nigeria as soon as he had picked up his stores and some more money, but his diary ends abruptly with the remark that he would be ready to start south again[25] from there in fifteen to twenty days. He died within twenty-four hours of reaching Ghat, on 3rd October, 1877. He had spent a cheerful evening with Kaimakam,[26] and had gone to bed; at 6 a.m. he was breathing peacefully asleep; by ten o’clock he was dead. His death does not seem to have been quite natural. It remains one of the mysteries of the Sahara. Von Bary’s account of Air[27] is very incomplete and his observations are coloured by the hardships which he suffered. With the exception of certain botanical information and notes on one or two ethnological points, his descriptions contain little that had not already been made known by Barth.

Then began that competition among European Powers for African colonies which was soon to reach a critical stage. The Anglo-German Convention of 1890 had proposed to divide Africa finally, but before that date the French had seen one desirable part after the other fall to our lot. They determined before it was too late to take as much as possible of what still remained unallocated. Central Africa, east of Lake Chad, certain tracts of indifferent country on the western coast and the greater part of the Sahara were still unclaimed by any European Power. And so it was that in France the magnificent scheme was conceived of sending three columns from north, west and south to converge on Lake Chad, and formally to take possession of the lands through which they passed in accordance with the stipulations of the Congress of Berlin, where it had been laid down that territorial claims were only valid if substantiated by effective occupation. It was not till 1899, however, that the French plans reached maturity. Three expeditions duly set out from the Congo, the Western Sudan and Algeria to cross Africa and meet on Lake Chad. Their adventures constitute one of the most romantic chapters in Colonial history. The western column, at first under Captain Voulet,[26] who was accompanied by Lieut. Chanoine and others, marched from the Niger along the northern edge of the Nigerian Emirates. Mutiny and murder among the European personnel were experienced. French politics at home, where the Jewish question had become acute, were responsible for all manner of delays; the command changed hands repeatedly. But the northern column and the Congo party were equally delayed; not until a year after the date fixed for the rendezvous on the lake did the three expeditions meet. The military escorts were united under Commandant Lamy, and gave battle to the forces of Rabah, one of the Khalif’s generals, who had crossed half Africa to carve out for himself a kingdom in Bornu and Bagirmi after the débâcle of the Mahdia on the Upper Nile. Lamy defeated him and annexed French Equatorial Africa.

Of these three expeditions, the northern column, known as the Foureau-Lamy Mission, had passed through Air on its way south. The Europeans who accompanied it were in 1899 the first Frenchmen to enter the country and to carry out the plan originally contemplated by Flatters in 1881. The annexation of Air by France may be counted from this date.

The Foureau-Lamy Mission[28] entered the borders of Air from Algeria at the wells of In Azawa; their heavy losses in camels obliged them to abandon large quantities of material, but they eventually reached Iferuan in the Ighazar, not far from T’intaghoda. Here the camp of the expedition was attacked in force by the Tuareg, who were only driven off with great difficulty. The situation was critical. The whole country was hostile to the French; they were so short of camels that on the stage south of Iferuan to Agellal they had to move their baggage in small lots, marching their transport forwards and backwards. Their destiny hung in the balance when friendly overtures were made to them near Auderas by a Tuareg of considerable note, Ahodu of the Kel Tadek tribe, whose fathers and forefathers for five generations had[27] been keepers of the mosque of Tefgun near Iferuan. Ahodu’s political sense has rarely been at fault, either then or since; he saw that the only end possible for his people from protracted hostilities with the Europeans was disaster. He promised the French peace while the column remained in Air. It reached Agades in safety, and the Sultan was obliged to hoist the French flag and provide transport animals and guides. No attack was made near the town, thanks to the efficacy of Ahodu’s presence, but his powers of persuasion were insufficient when the column marched out into the barren area further south. The guide purposely misled the expedition and it nearly perished of thirst, succeeding only with great difficulty in returning to Agades. It eventually started once more and reached the south, where its story ceases to concern the exploration of Air.

Since 1899, then, the fate of Air has been settled in so far as Europe was concerned, for it was recognised as lying within the French sphere; but the country was not effectually occupied until 1904, when a camel patrol under Lieut. C. Jean established a post at Agades. The post was evacuated for a short time and then reoccupied. The exploration of the mountains has proceeded slowly since that date. Sketch maps were gradually compiled in the course of camel corps patrols, and in 1910 the Cortier geographical mission published a very creditable map of the mountains,[29] other than the northern Fadé group, based on thirty-three astronomically determined co-ordinates supplementing the five secured by the Foureau-Lamy Mission. Chudeau in 1905 made a brief geological survey and published some notes on the flora, which remain uncatalogued to this day;[30] very complete collections of the fauna have been made by Buchanan[31] and examined in England by the British Museum (South Kensington) and by Lord Rothschild’s museum at[28] Tring. The ethnology of the country is very superficially discussed in a book published by Jean; Barth’s account remains the one of value. The complete exploration of the mountains and detailed mapping still remain to be done as well as other scientific work of every description.

“Air” as a geographical term for the mountainous plateau does not signify exactly the same thing to the inhabitants of the country themselves as it does to us; properly speaking, it is applied by them only to one part of the plateau, for the whole of which the more usual name of Asben or Absen is used. The latter is probably the original name given to the area by the people of the Sudan before the advent of the Tuareg. It is now very generally used even by them: it is universal further south. Barth has speculated at some length upon the origin of the name Air or Ahir, to take its Arabic form, and concluded that the letter “h” had been deliberately added out of modesty to guard against the word acquiring a copronymous signification. But early Arabic geographers give the form as Akir and not as Ahir, so the laborious explanation of the learned traveller is probably unnecessary.

The boundaries of Air may be defined either as running along the line where the rocks of the area dip below the sands of the desert, or as following certain well-marked basins and watercourses of material size, where disintegrated rock or alluvium has covered the lower slopes of the hills. The mountainous area is some 300 miles long by 200 miles broad. It lies wholly within the tropics and is surrounded by desert or by arid steppe. Owing to the general elevation of the country the climate is quite pleasant.

In remote ages the rainfall of the Central Sahara was sufficient to create the deep and important river beds which compose the hydrographic system of this part of North Africa. Among these watercourses is one of great size, flowing from the Ahaggar massif towards Algeria, called the Ighaghar. Duveyrier has tried to prove that it was the Niger of Pliny, largely on the grounds that the root “Ig”[29] or “Igh” occurs in both words and in Temajegh means “to run.” The effect of this identification, which is hard to accept, would be to make the classical ethnology of the Sahara less easy to follow, but it has little significance in considering Air, except in so far as it would tend to show that the geographical knowledge of the Romans did not extend as far south as the plateau. Complementary to the Ighaghar[30] but flowing south from the Ahaggar massif is another equally great river,[32] which early in its course is joined by a large tributary from the Western Fezzan. At a certain point this valley is crossed by the roads from Air to Ahaggar and Ghat, branching respectively at the wells of In Azawa or Asiu. The eastern branch is the caravan road to Ghat from the Sudan, the western one finds its way to In Salah in Tuat and to Algeria. This bed runs south and south-west towards the Niger, which it must have reached at some point between Gao and Timbuctoo in the neighbourhood of the N.E. corner of the Great Bend which the French call “La Boucle du Niger.” This river of remote times must have been one of the great watercourses of Africa, extending from the head-waters in 26° N. Lat. to its mouth in the Bight of Benin on the Equator. It is not possible to say whether the interesting terrestrial changes which diverted the Upper Niger at the lagoons above Timbuctoo into the present Lower Niger, and which brought about the desiccation of the upper reaches, took place suddenly or gradually, but the latter is more probable, for a similar diversion seems to be going on in the Chad area. The lake, in reality an immense marsh and lagoon, is much smaller than when it perhaps included the depression noted by Tilho as extending most of the way to Tibesti; some of the waters of the Chad feeders are already believed to be finding their way in flood-time into the Benue, and it is possible that in the course of time a similar process to that manifested in the Niger area will take place; then Lake Chad will dry up into salt-pans like those at Taodenit. The Saharan river, which flows southward to the west of Air, bears various names. Its course has never been accurately determined, but its general direction is known. From Ahaggar to a point level with the northernmost parts of Air it is called Tafassasset. The T’in Tarabin channel from Ahaggar more probably drained into the Belly of the Desert than into this system, but the Alfalehle (Wadi[31] Falezlez) from the Western Fezzan most certainly seems to be a tributary; there are various reasons why it ought not to flow towards Kawar, as used at one time to be thought. West of Air the main bed spreads out into a vast plain-like basin under the name of T’immersoi; further south it is called Azawak. In general I prefer to use the name T’immersoi for the whole until a better one is suggested.[33]

The T’immersoi forms a collector in the west of Air for nearly all the water from this group of mountains. Nowadays only a comparatively small amount ever reaches the basin, as much is absorbed by the intervening plain land of Talak[34] and the Assawas swamp west of Agades. The latter are local basins or sumps covered with dense vegetation where some of the most nomadic tribes in Air pasture their herds. Talak is visited by Tuareg from Ahaggar and from the west for the same purpose. It plays an important part in the economy of the country, for water is always to be found in the alluvial soil however dry the season in the mountains has been. Many of the wells have now fallen into disuse, but the output of those which remain is still plentiful. The last rocks of Air on the west disappear below the alluvium of T’immersoi and in the subsidiary basins of Talak and Assawas. The T’immersoi system therefore forms the western boundary of Air.

The upper part of the T’immersoi, where it is called the Tafassasset, is also the northern boundary of Air. The wells of In Azawa[35] and Asiu in this valley may be regarded as the point where the main roads from the north enter the extreme limits of the country. Further east on another road between Air and Ghat, von Bary fixed the boundary at the Wadi Immidir, which is in the same latitude as In Azawa.[36]

[32]The eastern boundary of Air runs along the line where the last rocks of the group disappear below the sand of the steppe and desert, which extends from north to south between the mountains of the Fezzan and the fringe of Equatorial Africa, and from west to east between the mountains of Air and those of Tibesti with its adjacent massifs. This vast area is crossed by a few roads only, the most important ones being (a) the road from Murzuk along the Kawar depression to Agadem and Lake Chad, (b) and (c), the two principal tracks from Air eastwards to Bilma by Ashegur and Fashi respectively, and (d) the road from Zinder by Termit to Fashi and Kawar. Watering-points are very few, and the habitable oases can be numbered on the fingers of two hands; pasturage is everywhere scarce. This great waste is one of the most unknown parts of North Africa; its eastern portion along the Tibesti mountains as far north as the Fezzan may be said to be absolutely unknown except for two tracks to the mountains whither occasional camel patrols have passed.

Kawar and the other oases along the Chad road appear to be closed basins of the Eastern Saharan type. They seem to have no outlet towards the south either into the Chad or into the Niger systems. The desert east of Air, therefore, contains the eastern watershed of the T’immersoi basin, for the valleys of Eastern Air do not run into the desert as Chudeau has suggested,[37] but turn southwards on leaving the hills, in ill-defined depressions or folds which join the Tagedufat valley or one of the other channels flowing westwards in Tegama or Damergu. One valley to the south of Air, probably the Tagedufat itself, is stated to run all the way from Fashi across the desert.

The southern limits of Air may be placed along the Tagedufat basin, where the rocks of Air disappear below the sand dunes and downs of Tegama and Azawagh steppe[33] desert. The valley is of some size and flows roughly N.E. and S.W. towards T’immersoi, but whether it actually joins this system or the Gulbi n’Kaba, which finds its way into Sokoto Emirate under the name of the Gulbi n’Maradi and thence into the Niger, is not certain. The former hypothesis seems more probable, but I was unable to follow the Tagedufat sufficiently far west to verify it, nor could I discover any data on the French maps;[38] local reports substantiate my supposition. Both systems in any case are in the Niger basin. Air is not on the watershed between Niger and Chad. The choice of the Tagedufat valley as the southern boundary of Air is made on geographical grounds. What may be termed the political boundary is rather further north along the line of the River of Agades.