The following account of this ghost-laying is given as related by the old tinner,1 except where his dialect might be unintelligible to general readers. It is curious

that he made the spirit-queller address the ghost by the uncouth word “Nomine domme,”

which he thought a proper name. One cannot doubt that the expression used by the original

story-teller was (In) nomine Domini, which became corrupted, as above, by the usage of more ignorant droll-tellers of

recent times.

On asking my venerable gossip what the term signified, he replied to the effect that

it would take a conjurer to tell. He had heard it was a magical word, very likely

the spirit’s name among spirits, for old folks held that they acquire new ones quite

different from what they bore when in mortal bodies; that persons, knowing and using

these secret names, obtained power over spirits, whether black or white; by this means

conjurers controlled them, and witches summoned fiends to work their wicked will for

a time. According to old belief, the infernal gentry were fond of wandering incog., just like mortals of high rank, that they might not have too many witches to work

for. That strange word was the only one remembered of the parson’s conjuring formulary;

“the others,” said he, “were as long as to-day and to-morrow, not like ours, for none

but a parson, or some such learned body, could utter them.”

When speaking of evil spirits, he called them “Bukkaboos,” which is a recent corruption

of “Bukka-dhu” (black spirit,) as old folks, who knew anything of Cornish, pronounced

it. Within the writer’s remembrance, “Bukka-gwidden” (white spirit) was also in frequent

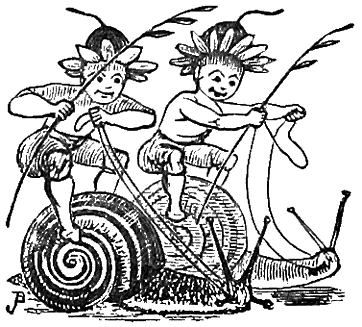

use, though there was great latitude allowed to its signification. All good spirits,

including, “small people” (fairies) were thus termed, except Piskey; he was regarded

as “something between both,” like St. Just Bukka said he was, on seating himself between

a mine-captain and a “venturer,” who asked him if he were a fool or a rogue?

If Piskey threshed poor old people’s corn and did other odd jobs for them by night,

he was just as ready to lead them astray and into bogs, for mere fun; to ride the

life out of colts; dirt on blackberries; and do other mischievous pranks. A precocious child, one “too wise to live long,” who bothered old folks by

asking awkward questions, was called a “Bukka-gwidden,” as well as a poor simple,

innocent, harmlessly insane person, or near to it. [27]My old west-country schoolmaster, of a little more than fifty years ago, often applied

this name to his scholars.

Persons who have been acquainted with our old droll-tellers know that they gave free

rein to fancy, provided they had an audience to their mind; being well aware that,

for the most part,

“A jest’s prosperity lies in the ear

Of him that hears it.”

It is often remarked by strangers that the Cornish don’t understand a joke; but, if

one may judge by the grotesque scenes and adventures of our old stories, that was

not the case in past times, when there was less affectation and Puritanism than at

present.

Some of the incidents related seem absurd enough, yet, as they may dimly shadow forth

some old belief, it was thought best to give them, for better for worse, as consistency

is not expected in very old stories, such as follow:—

The housekeeper was confined to her task, as already stated, long before the family

succeeded in getting “Wild Harris” laid. Many ineffectual attempts were made, which

only resulted in harm, by raising tempests which destroyed crops on land and life

at sea; besides, after these vain trials of parson’s power, the ghost became more

troublesome, for awhile, than he was before their interference with his walks.

Fortunately, however, the Rev. Mr. Polkinghorne, of St. Ives, acquired the virtue

whereby he became the most powerful exorcist and “spirit-queller” west of Hayle.

From the little that is known of this gentleman, one may infer that he wasn’t, by

any means, such as would now be styled a “pious character.” He is said to have been

the boldest fox-hunter of these parts, but he would never chase a hare; any attempt

to kill one would make him swear like a trooper. He kept many of these innocent animals—the

hares—running about his house like cats; foolish people said they were the parson’s

familiar spirits or witches he found wandering in that shape. He was a capital hurler,

and encouraged all kinds of manly games, as he said they produced a cordial “one and

all” sort of feeling between high and low. The parson was mostly accompanied by his

horse and dog, which both followed him. When he stopped to chat, Hector, his horse,

came up and rested his head on his master’s shoulder, as if desirous of hearing the

news too. If he called at a house, both his attendants waited at the door, his horse

never requiring to be held. He made long journeys with his steed walking alongside

or behind him, the bridle-rein passed round its neck and the stirrups thrown across

the saddle. Wonderful stories are also told about the high hedges and rocky ground

that the parson’s horse would take him safely over, when after the hounds; and how

the birds, which [28]nestled undisturbed in his garden, and other dumb creatures seemed to regard him as

one of themselves.

On being requested to do his utmost in order that “Wild Harris’s” ghost might rest

in peace, or be kept away from Kenegie, the reverend gentleman replied that he hoped

to succeed if it were in the power of man to effect it.

Other clergymen, hearing of what was about to be attempted, expressed a wish to be

present at the proceedings. Mr. Polkinghorne replied that he neither required their

assistance nor desired their presence, yet, any of his reverend brethren might please

themselves for what he cared. Moreover, he charged them that, if they came to Kenegie

on the appointed night, not to intermeddle in any way, whatever might happen.

A night in the latter end of harvest was appointed for this arduous undertaking. Several

clergymen being anxious to see how the renowned spirit-queller would act with a ghost

that had baffled so many of them, about an hour before midnight four from the westward

of Penzance, a young curate of St. Hellar (St. Hilary), and another from some parish

over that way, arrived at Kenegie, and waited a long while near the gate, expecting

Mr. Polkinghorne. At the turn of night, a terrific storm came on, and the six parsons,

drenched to their skins, took refuge in the summer-house. Candles had been lit in

the upper room of this building, as it was understood that the spirit-quelling operations

would be performed there. They waited long, but neither Polkinghorne nor Harris’s

ghost appearing, the curate of St. Hellar—impatient of inaction—took from his breast

a book, and read therefrom some conjuring formulas, by way of practice, or for mere

pastime. As he read, a crashing thunder-clap burst over the building, shook it to

its foundations, and broke open the window. The parsons fell on the floor, as if stunned,

and on opening their eyes, after being almost blinded by lightning, they beheld near

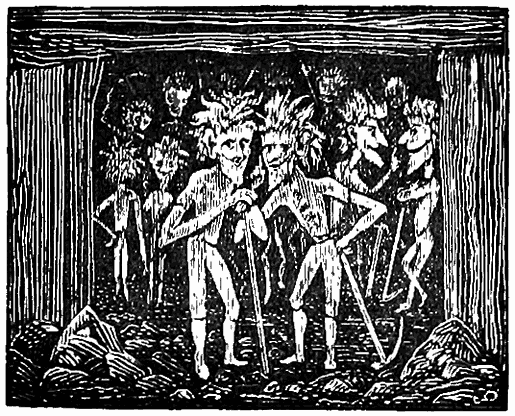

the open door a crowd of “Bukka-dhu” grinning at them, and then partially disappear

in a misty vapour, to be succeeded by others, who all made ugly faces and contemptuous

or threatening gestures. “It was enough to make the parsons swear,” if they hadn’t

been so frightened, to see how these jeering “Bukkas” mocked them.

The reverend gentlemen crawled to the window and looked out, to avoid the sight of

such ugly spectres, and to get fresh air,—that in the room smelt worse than the fumes

of brimstone. Presently, an icy shiver ran through them, and they felt as if something

awful had entered the room. On glancing round, they beheld the apparition of a man

standing with his back to the fireplace, and looking intently towards the opposite

wall. His eyes never winked nor turned away, but seemed to gaze on something beyond

the blank wall. He wore a long black gown or loose coat which [29]reached the floor; his face appeared sad and wan, under a sable cap, garnished with

a plume and lace. He seemed unconscious of either the black spirits’ or parsons’ presence.

Over a while, he turned slowly round, advanced towards the window, with a frowning

countenance, which showed the parsons that he regarded them as intruders; and they,

poor men, trembling in every limb, with hair on end, pressed each other into the open

window, intending to drop themselves to the ground, and risk broken bones and an ugly

“qualk” (concussion), for they were most of them fat and heavy.

Meanwhile, scores of “Bukkas” continued to hover behind the ghost, grimmacing as if

they enjoyed the parsons’ distress. Every minute seemed an hour to the terrified gentlemen;

but, as some of them got their legs out through the casement, the tread of heavy boots

was heard on the stone stairs, and Polkinghorne bounced into the room, when the ghost,

turning quickly round, exclaimed, “Now Polkinghorne, that thou art come, I must be

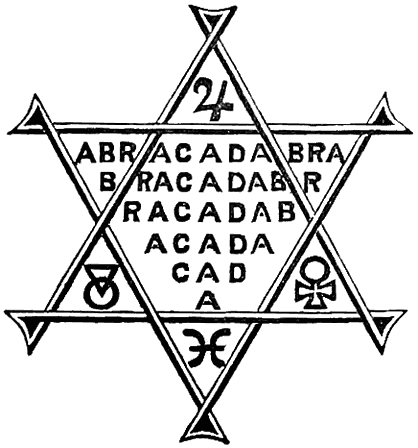

gone!” The conjurer quietly holding out his hand towards the ghost, quietly said “In nomine Domini, I bid thee stay;” then he turned to the black spirits, made a crack with his hunting-whip,

said, “Avaunt, ye Bukkadhu,” and off they went, at his word, howling and shrieking

louder than the tempest. The ghost stood still; Polkinghorne uttered long words in

an unknown tongue whilst he drew around it, on the sanded floor, with his whip-stick,

a circle and magical signs, with a “five-pointed star” (pentagram) “to lock the circle.”

He continued speaking a long while without pausing, and his words sounded deep and

full, as if, at once, near and afar off, like the “calling of cleaves” and surging

of billows on a long stretch of shore, or thunder echoing around the hills.

At length the spirit felt the able conjuror’s power, crouched down at his feet, holding

out his hands, as if praying him to desist.

Mr. Polkinghorne, whilst still saying powerful words, unwound, from around his waist,

a few yards of new hempen “balsh” (cord), leaving much more of it attached. Having

made a loop at the end, he passed it over the ghost’s head and under his arms; then,

addressing him, said, “In nomine Domini, I bid thee stand up and come with me.” On saying this, he lifted from the floor,

with his whip-stick, the spirit’s skirts, and under them nothing was seen but flaming

fire.

When Polkinghorne had the spirit standing beside him, with his eyes fixed and limbs

motionless, like one spell-bound, he exclaimed, “Thank the Powers, it’s all right

so far.”

Casting a glance towards the other parsons, and seeing a book on the floor, he took

it up, opened it, and speaking for the first time to his reverend brethren, said,

“You, too, may thank your lucky stars that I came in the nick of time to save ye from

grievous [30]harm.” Holding it towards the St. Hellar curate, he continued, “This belongs to you,

my weak brother; strange such a book should be in your possession! The penmanship

is beautiful; it must have cost a mint of money, yet it is worse than useless,—nay,

it’s perilous to such as you. By good luck, you read what merely brought hither silly

‘Bukkas’; one can’t properly call them demons, though no others were known here in

old times; they now mostly keep to old ruined castles, ‘crellas,’ and ‘fougoes,’ yet

they are always abroad in such a night as this. But, if you had chanced to have pronounced

a word, that you don’t understand, on the next leaf, you would have called hither

such malignant fiends, flying in the tempest this awful night, as would have torn

ye limb from limb, or have carried ye away bodily. Perhaps, becoming tired, they might

have fixed ye on St. Hellar steeple. For my part, I wish you were there, lest a greater

evil befall ye this night.

“You ought to have known, as any old ‘pellars’ (conjurors) would have told ye, if

you had deigned to talk with such without preaching to them, that the secret of secrets,

the unwritten words which make this book of use, are the names of powerful and benevolent

spirits, by whose aid fiends are expelled. These secret names, by which alone they

may be invoked, are only taught, by word of mouth, to the few who are initiated, after

long probation, mental and bodily, and a more severe examination, by nine sages, than

the likes of you would ever pass. Many, to their sorrow, have been presumptuous to

make the essay. Sages hold that if these sacred names were written they would lose

their magic power.

“The mystic signs, necessary for obtaining mastery over some spirits, are only traced

in sand, or other substance from which they are readily effaced when those deemed

worthy have this knowledge imparted. Not so very long ago, the learned in occult science

met, at stated times, on the lonely downs, and at the same places in which sages were

wont to confer in days of yore for the examination of such as sought admission into

their fraternity, and for the preservation of their mystic lore. Novices were principally

examined as to their proficiency in the science of extension, and in making such reckonings

as are required for constructing a planetary scheme at any given time. Not that these

sciences had much connection with the more mysterious subjects treated of in this

manuscript; but, it was justly considered that the person having a mind capable of

comprehending geometrical problems, and of making abstruse astrological calculations,

was worthy to be admitted into the brotherhood of sages, and, in time, to their higher

mysteries.”

After a pause, in looking sadly at the ghost, who seemed to listen with attention,

he continued, addressing the gentlemen of [31]St. Hellar, “I suppose you have heard the old saying, ‘Women and fools can rise devils,

but it takes wise men to lay them.’ Indeed, tradition says that, in ancient times,

fair young witches first obtained this dread knowledge from their demon lovers, to

summon them whenever they desired; old hags soon pried into the secret—as they will

into all kinds of deviltry,—and quickly communicated from one to another, until witches

became numerous in all Christian lands; thousands of them were burnt as a warning,

but their burning didn’t deter others from the like evil practices.

“The demons became disgusted of witches continually crying after them, to wreck their

vengeance on innocent man and beast, and did their best to evade them. Much more may

be said on the subject, but time presses. I have still arduous work to perform, so

only another word, my over-curious brother,—burn this book of magic in the first convenient

fire.”

Saying that, he cast down the book; spoke a few words, which the others didn’t understand;

drew his foot over a mystic sign that “locked” the charmed circle; and, turning towards

the spirit, said, “In nomine Domini, come thou with me,” and “Wild Harris’s” ghost was led away, quiet as a lamb.

Mr. Polkinghorne, having reached the outer gate, took his horse, which he had left

there. The poor beast trembled, though this ghost was not the first, by many, that

had been near it. Having mounted, he gave the ghost more rope, and bade him keep farther

from Hector. A minute afterwards the four west-country parsons, without as much as

saying, “I wish’e well, till we meet again,” took down hill as fast as their horses

could “lay feet to ground;” it was “the devil take the hindmost” with them.

In passing up Kenegie lane, the parson’s horse was very “fractious;” it jumped from

side to side, tried to leap over hedges, and screeched like a child; yet it became

pretty quiet at last, when the spirit kept off to the end of his tether. Few bleaker

places are to be found than the old road to St. Ives, passing over Kenegie downs.

When they got there, the wind seemed to beat on them from all points at once; rain

and thunder never ceased; the Castle-hill seemed all ablaze with lightning; at times,

too, when a more violent blast than usual whirled around them, clouds of fiends hovered

over them like foul birds of prey; the sky was pitch black, and demons were only seen

by the forked lightning that burst from their midst. The ghost, as if seeking protection,

came nearer the parson; then his horse’s terror became painful to witness, until a

few magical words and a crack of his whip sent the devils howling away, and the ghost

to the end of his rope. At last they came within a stone’s cast of a few dwellings

called Castle-gate, and leaving the highway took a path on the left that wound up

the hill to Castle-an-dinas.

[32]

We leave them for awhile to look after St. Hellar curate and his friend.

One might think that the two parsons from eastward would have taken their nearest

way home, over Market-jew-green; but no, St. Hellar curate thought he would rather

go many miles out of his way than miss this opportunity of seeing a spirit put to

rest, and his friend was afraid to go home alone; so they both started after the ghost-layer,

keeping sufficiently near to see him on horse-back, leading the spirit, as they ascended

the hill. The lightning was almost continuous, otherwise the night was very dark.

On reaching the open downs, however, they found it impossible to keep their saddles,

even by holding on with both hands to their horses’ manes. Their hats were blown away,

and their cloaks flying from their necks like sails in a hurricane rent from the yards.

They alighted and trudged along, in single file, dragging their unwilling steeds behind

them, for the horses wanted to take their accustomed road home, and didn’t like the ghostly company ahead.

When Mr. Polkinghorne reached the hamlet, called Castle-gate, and entered a narrow

lane leading up to Castle-an-dinas, they were so far behind as not to see his departure

from the highroad; and, on coming near the lonely cottages, decided to stay there,

if they could find shelter; but, on a closer view, the dwellings appeared to be deserted;

the thatch was stripped from their roofs, leaving bare rafters on all but one of them.

On approaching that dwelling, they heard Mr. Polkinghorne’s Hector neigh from the

downs; their horses replied, and there was more whinnying from Hector, which showed

the direction taken, and set St. Hellar parson all agog, to follow the ghost-layer.

As they crossed the road and paused a moment, a whirlwind passed over the house, where

they thought of seeking shelter, and took up a bundle of spars (small rods, pointed

at both ends, and used for securing the thatch) which a thatcher, who had been repairing

the roof, had left there, pinned to the work with a broach, that he might find them

to hand when he continued his thatching. The bundle being taken high up and whirled

about, its bind broke, and one of the devil-directed spars pierced St. Hellar curate’s

side, just above his pin-bone, (hip-joint) like an arrow shot from a bow. He fell

on the ground like as if killed, and his companion, in drawing the spar out of his

friend’s side, had his hand burnt, just as if he had grasped red-hot iron.

Presently, the black clouds rolled away westward, and the wind lulled. Then the spar-wounded

man was raised by his companion; lifted on to his horse; and laid across the saddle,

like a sack of corn. They went slowly on and reached Nancledery about daybreak. Having

rested a few hours at the Mill, it was found that [33]the St. Hellar curate was still unable to sit on horseback, and he was taken home

in a cart.

The reverend gentleman was, ever after, lame; and bore to his grave marks of his spar-shot

wound; that’s the last we heard of him.

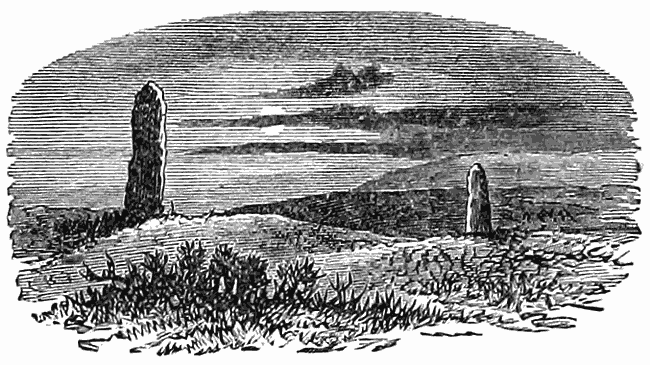

We now return to Mr. Polkinghorne. At the time of this ghost-laying there were, around

the Castle-hill, extensive tracts of open heath, which are now enclosed; and the highway

is skirted by hedges, where it was then open downs, there being several more small

dwellings built at Castle-gate.

The parson’s Hector was well acquainted with the lay of the country all around, as

he had often crossed it following the hounds; and, after scrambling through the narrow

lane, tried his utmost to take away down over the moorland to a smith’s shop in Halangove,

where he had often been shod. By a firm hand on the bridle-rein his master kept him

up-hill for a furlong or so, when they came to an old gurgie (ruined hedge) that once

enclosed a fold. On one side there was a bowjey (cattle or sheep-house). A dwelling

and outhouses have since been built, and a few quillets (small fields) enclosed near

this spot. Mr. Polkinghorne alighted, turned his horse into the old “shelter,” and

bade the ghost approach.

They walked on in silence until they came to the Castle’s outer enclosure, which screened

them from the blast. Then the reverend gentleman said, “Now that we are alone, and

not likely to suffer any more intrusion, tell me, my unhappy brother, what it is that

disturbs thy rest? Be assured, my desire is to procure thee peace.”

The spirit replied to the effect that, at the time of his decease, he was much troubled,

because he owed several sums to work-people and others, fearing they wouldn’t be paid by his successor. Moreover, he related how he had walked about for years,

hoping some honest body would speak to him; how the longer he was left unspoken to

the more uneasy and troublesome he became; and when his relations brought the parsons

to lay him, who were unqualified for that office, he was much exasperated, and he

determined never to leave Kenegie.

“Yet, it gave me some pleasure,” said the ghost, “to make those who came and read

long curses, as if exorcising an evil spirit to “cut and run” and nevermore return,

by only advancing a step towards them. Though spirits seldom speak until first addressed,

I couldn’t help exclaiming, as I did, and wished to escape when you surprised me by

entering the summer-house; but I am now satisfied to be in your power, trusting you

will procure me rest.”

“Be assured, my son,” replied the parson, “that I will see all thy debts paid.”

“That will relieve me of much,” said the spirit, “yet there are other subjects that

trouble me; but you must promise me never to divulge them, ere I make a clean breast

of them.”

[34]

“My profession obliges secrecy in such cases,” replied his adviser, “therefore speak

on without reserve.”

The poor ghost having unburthened himself, Mr. Polkinghorne gave him words of comfort,

and concluded by saying, “think no more about your little faults and failings, for

if, when in mortal life, you had more of what we call the devil in ye, you would have

overcome your opponents, and much grief would have been spared to yourself and others.

“Besides, my son,” continued he, “from your simple, honest, and confiding disposition,

you were unable to cope with sly, mercenary hirelings.”

Then the parson took the cord off, saying, “This is no longer required to protect

ye from evil spirits, for they have all departed with the tempest they raised, and

the sky is now serene.”

As they ascended the hill the moon shone bright on the old fort’s inner enclosing

wall, which was then almost intact. The upper enclosure is nearly oval in outline,

and they entered it at its south-eastern end. Stopping a minute on the hill-top, Mr.

Polkinghorne said to the ghost, “There is no cure for a troubled spirit equal to constant

employment, and I shall allot you an easy task, which, with time and patience, will

procure ye repose; but I must first make the whole of this enclosure secure against

infernal spirits.”

Mr. Polkinghorne then used a form of exorcism, which, as far as it could be understood

by the old story-teller’s account, was something like the following:

Having placed the ghost on his right hand side, he passed with him three times around

the enclosed hill-top, going from east to west, or with the sun, and keeping close

to the wall. At the first round, he merely counted the number of paces; at the next,

he uttered, in some ancient eastern tongue, such exorcisms and adjurations as serve

to expel infernal spirits; at the last circuit, he made, near the bounding wall, twelve

mystic signs, at equal distances. He then passed through the middle of the ground

to its north-western end, “cutting the air” with his whip, and tracing on the earth

more magical figures. Being arrived at the end opposite the entrance, he drew a line

with his whip stick, from a large stone in the wall, on one side, to another opposite,

and told the spirit to remember them as bound-stones. The space thus marked off might

be three or four “laces” of pretty even grass-covered ground, with a few furze bushes

and large stones scattered over it.

The reverend gentleman rested a while on the ruined wall, which rose some ten feet

above a surrounding foss, and three or four from the inner ground.

“Now, my son,” said he, turning towards the ghost, who stood near, “all within the

Castle’s upper walls is as safe for ye as consecrated ground; and here is your task,

which is merely to count [35]the blades of grass on this small space, bounded by the wall and a straight line from

stone to stone, that you can always renew or find.

“You must reckon them nine times, to be sure that you have counted right; you needn’t

set about it till I leave, there’s plenty of time before ye.

“Whilst at your work, banish from your thoughts all remembrance of past griefs, as

far as possible, by thinking of pleasant subjects. There is nothing better for this

purpose than the recollection of such old world stories as delighted our innocent

childhood, and please us in mature age.”

The spirit looked disconcerted and said something—the old tinner didn’t know his words

exactly,—to intimate that he thought the assigned task a vain one, as it produced

nothing of lasting use. He would rather be employed in repairing the Castle walls,

or some such job.

“No, my dear son,” replied the parson, “it would never do for ye to be employed on

anything that would be visible to human eyes; the unusual occurrence would draw hither

such crowds of gazers as would greatly incommode ye. No more need ye trouble yourself

on the score of its mere use, in your sense; for if restless mortals employed themselves

solely in such works of utility as you mean, the greater part of them would find nothing

to do, and be more miserable than ghosts unlaid.”

The poor ghost assented to the greater part of what the parson said, and the reverend

gentleman resumed his discourse, which was enough of itself to “put spirits to rest”

one might think.

“Believe me, gentle spirit,” said he, “the world is just as much a show as our old

Christmas ‘guise-dance’ of St. George; for a great number pass their lives in doing

battle with imaginary dragons; others in racing about on their hobby-horses, to the

great annoyance of quiet folks. There are numerous doctors, too, both spiritual and

physical, for ever vaunting of their ‘little bottles of elecampane,’ as sovereign cures for all ills but their own; whilst the motley crowd is bedizened

in fantastic rags and tinsel, just like ‘guiseards.’ Indeed, except honest husbandmen,

simple artisans, and a few others, the rest might just as well pass their time in

spinning ropes of sand, counting blades of grass, or in any other ghostly employment,

for all the good they do, unless it be to tranquilize their restless minds.”

The ghost made no reply, but seemed “all down in the mouth,” which expression of sadness

the parson remarked, and said, “Don’t ye be out of heart, brother, but have patience,

and you will find that, with constant work, years will pass away like a summer’s day.

Then you will wonder how your mortal crosses ever had the power to trouble ye. All

remembrance of them will fade like a dream, and you will rest in peace.

[36]

“When you have a mind to pause awhile—say after each time of counting,—you can go

around the hill-top and enjoy the extensive prospect, as all within this higher rampart

is a charmed circle for ye, where fiends dare not enter. There are other pleasant

sights which you will often behold; for the small-people (fairies) still keep to the Castle-hill and hold their dances and fairs, of summer

nights, within these ramparts. On May-day, in the morning, they are frequently seen

around the spring, just below, or going up and down the steps which lead to it, by

young men and maidens who come at early dawn to clean out the Castle-well, and to

deck it with green boughs and blossoming May, as is their wont. These gay beings are

the spirits of old inhabitants who dwelt—it may be thousands of years ago—in the ‘Crellas,’

at Chysauster.

“There is something more which will serve to divert ye; people from far and near often

come here to enjoy the charming prospect; you may learn by their talk what is going

on in the country round, if you care to hear anything about it. Perhaps some of the

neighbours may speak of you and your family, and say things neither pleasant nor true;

but let me beg of ye, however much you may be vexed to hear their slander, for goodness

sake, don’t ye contradict them, nor show yourself; for your apparition, in its rich

but antiquated garb, would frighten poor weak-minded mortals into fits.”

The poor ghost seemed “dumbfoundered,” and said not a word: so the parson went on

as if in his pulpit. At length he stood up and said, hastily, “One might mention more

of what will make your abode pleasant, but it’s high time for you to become invisible

and for me to leave ye. The cocks will soon be crowing; see how fast the light increases

on Carn Marth, Carn Brea, and other noble hills that were giants’ dwelling places

in days of yore, and stand out against the grey sky like sentinels over this favoured

Western Land.”

The parson, pointing to the eastern sky, told the spirit to put off his form. In a

minute or so the apparition became indistinct, and faded gradually away, like a thin

wreath of smoke dissolving in air.

Mr. Polkinghorne said farewell, and, as he turned to leave the spirit to his task,

he heard a hollow voice say, “Good friend, do thou remember me, and visit me again.”

When the reverend gentleman entered the old “bowjey,” the joy that his horse showed

at his approach was like recalling him from death to life.

As Mr. Polkinghorne slowly wended his way homeward, he was grieved to see the wreck

made by the preceding night’s tempest. In Nancledry, low-lying as it is, dwellings

were unroofed, and trees, which had withstood the storms of centuries were all [37]uprooted. On higher ground “stones were blown out of hedges,” arish mows laid low,

and the corn whirled around fields.

About sunrise, St. Ives folks, standing at their doors, were surprised to see their

beloved parson, coming down the Stennack, looking so sad and weary, and that he didn’t give them “the time of day” (a greeting

suitable to the time, as good morning, &c.,) with his accustomed cheerful tone and

pleasant smile. Neither Mr. Polkinghorne nor his steed were again seen in the street

for several days after their ghostly night’s work.