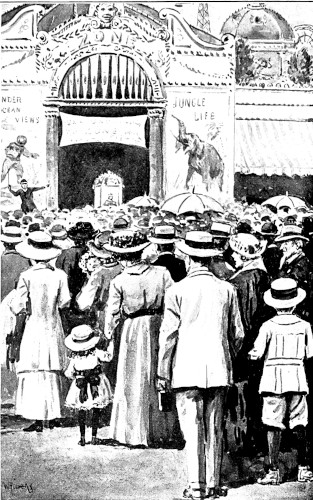

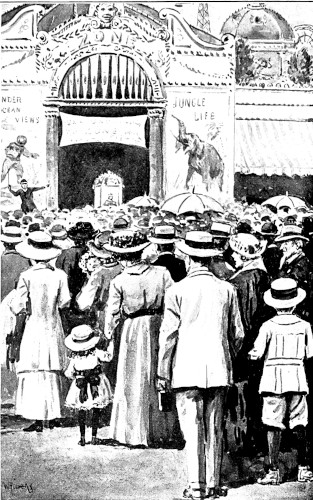

THE ZONE THEATRE WAS A GREAT SUCCESS.

Title: The motion picture chums at the fair

or, The greatest film ever exhibited

Author: Victor Appleton

Release date: June 17, 2025 [eBook #76331]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1915

Credits: Aaron Adrignola, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

Or

BY VICTOR APPLETON

AUTHOR OF "THE MOTION PICTURE CHUMS' FIRST VENTURE,"

"THE MOVING PICTURE BOYS," "TOM SWIFT SERIES," ETC.

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS

NEW YORK

Copyright, 1915, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP

The Motion Picture Chums at the Fair

THE ZONE THEATRE WAS A GREAT SUCCESS.

| I. | A Collision |

| II. | The Rescue |

| III. | Making Plans |

| IV. | A Hurried Departure |

| V. | The Chance Encounter |

| VI. | A Warning |

| VII. | At the Fair |

| VIII. | A Great Disappointment |

| IX. | Talking It Over |

| X. | At the Cliff House |

| XI. | The Lonely Lad |

| XII. | Queer Actions |

| XIII. | A Queer Story |

| XIV. | The Wonderful Films |

| XV. | A Disclosure |

| XVI. | Investigation |

| XVII. | "Wild Life" |

| XVIII. | Suspicions |

| XIX. | Hot Words |

| XX. | At the Asylum |

| XXI. | The Concession |

| XXII. | The Theatre |

| XXIII. | The Theft |

| XXIV. | Recovery |

| XXV. | Success |

"Hard times don't seem to bother us much."

"No, the crowds still keep on coming. If it only lasts."

The speakers were two young men, part of a little company gathered in the office of a moving picture theatre on upper Broadway, New York City. On a table in front of the party was a pile of bills and silver.

"Yes, we certainly are taking in the coin," observed Randolph Powell, the first speaker, with a glance at the money.

"All I'm afraid of is that there's likely to be a drop, sooner or later," responded the other, a youth with a slightly freckled face who answered to the name of Pepperill Smith—or, more often, Pep.

"Now, don't talk that way!" objected Randolph, whose name had been shortened by his friends to Randy. "Why shouldn't we enjoy our good luck while it's coming?"

"Oh, of course, I didn't mean anything," spoke Pep, quickly. "But what's the matter with you, Frank? You haven't said a word for the last five minutes."

"Frank's up to some scheme; aren't you, old man?" asked Randy. "Come on, let's have the benefit of your ideas. Doesn't this satisfy you?" and he waved his hand toward the pile of money on the table.

"Well, I should say it ought!" exclaimed a man sitting in one corner of the office. "I call it high-falutin' good, that's what I call it, and let me tell you Hank Strapp of Butte, Montana, isn't an easy person to suit when it comes to cold coin. I like mine plenty and with lots of gravy and white meat!" and he laughed in a hearty way at his own joke.

"Well, if you're satisfied, Mr. Strapp, after all the money you've put into this motion picture business, I'm sure Frank Durham ought to be!" declared Pep, with the quickness for which he was noted. His voice had in it just a tinge of sharpness, though perhaps he did not mean it that way. Frank looked up quickly.

"I'm not finding a bit of fault!" declared the lad, whose face showed that he was perhaps a shade deeper thinker than either of his young chums. "We're doing splendidly; we all agree on that."

"Well, then, what ails you?" demanded Pep.

"Nothing. I'm all right," and Frank smiled at his impetuous friend.

"I don't call it all right for a fellow to sit there, with all that money staring him in the face, and not feel good over it," objected Pep. "You might at least offer to treat us to ice-cream sodas after the best day's business in a year."

"Oh, if it's a matter of soda, of course—come on out and have some," replied Frank, with a smile. "But first we'd better put this away," and he waved at the money which had been neatly arranged in piles on the table, the bills of various denominations stacked by themselves, and the silver arranged in dollar lots, for easy counting.

Outside the office of the motion picture theatre could be heard a jumble of sounds. Above the distant hum and roar of the streets came the sound of women cleaning the rows of theatre seats, and there also came the peculiar hissing sound of the hand-disinfectors which porters were carrying about, spraying the air of the recently emptied playhouse, to make it clean and sweet for the coming performance.

It was about nine o'clock in the morning, and the Empire motion picture place opened at eleven, remaining in continuous operation until that same hour at night. Soon it would be ready for the crowds of patrons which would throng to it to view the wonderful motion pictures on the screen.

The money on the table represented what had been taken in the day and evening before, and, as Pep had remarked, it was the largest day's receipts the motion picture chums had ever received from this particular house—one of several they controlled.

"Hurray! Frank's going to treat!" exclaimed Pep, getting up from the table in such a hurry that he nearly upset it.

"Careful!" cried Randy. "Money doesn't come in so easily, these European war times, that we can afford to scatter it."

"That's right!" chimed in Hank Strapp. "I'd sure hate to see this stuff spilled."

"Huh! Don't worry. I'm not going to spill it," declared Pep. "And now would you look at him," and he pointed to Frank. "There he goes again—mooning!"

And indeed Frank did seem to be in a brown study, from which he had roused himself long enough to offer the soda treat, only to again fall into a reverie.

"Frank, look at me straight!" demanded Hank Strapp, in his breezy, Western way, which, while it was light enough, yet had in it a deal of earnestness. "As between man and man, is anything worrying you? Answer me straight now!"

If anyone could answer Hank Strapp other than "straight" with those clear blue eyes of his looking so fearlessly at one, it would have been an occasion out of the ordinary. Certainly Frank Durham had no such intention.

"Are you worried?" asked Mr. Strapp. "Have any of our old enemies been making trouble for you, unbeknownst to us? Is the business going badly? Has the trust tried to gobble up the supply of some of our films? If they have——" and Hank paused to prepare a sufficiently strong, yet proper expression.

"Nothing at all like that," declared Frank. "I don't see why you are making all this fuss."

"Fuss! As if anyone wouldn't make a fuss when you sit here as glum as an oyster, while we count our hard-earned wealth," broke in Pep. "Think of it! We never before had such crowds coming to our New York house, and they never kept it up so! Why, when other motion picture places, not many blocks away from us, are reeling off their stuff to half-empty seats, we're packed to the doors, and straining the fire department regulations to accommodate our crowds. And you——"

"Hold on, Pep," spoke Frank quietly, but determinedly. "I am not at all dissatisfied. In fact, I'm immensely pleased, and I've just been thinking of a way by which we can make more money, I hope."

"You have? Say, old man, I beg your pardon. Forget all I said!" burst out the impulsive Pep. "Let's hear it!"

"More money! That's me!" cried Hank Strapp. "What's the latest scheme, Frank?"

"And don't leave me out!" begged Randy, pushing some of the piles of money to one side that he might sit on the office table, and hear what his chum had to say.

"It's just this," began Frank. "I've got a new idea, and yet it isn't so very new, for I've been mulling over it for some time. What do you say to opening a motion picture theatre at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco?"

Frank's question produced a momentary silence. Then Pep, as usual, was the first to burst out:

"Great! Immense! That's the best ever! How'd you come to think of that?"

"Well, as I said, I've been figuring on it for some time," answered Frank, "and when I saw how we were coining money here, it occurred to me that we couldn't invest it in any better way than by taking a flier out there. But there are several points to be considered."

"Considered!" cried Pep. "I say it's all settled, if you've thought it over, Frank. We'll do it; eh, Randy?"

"Sure, I'll go into it if the rest of you do," and Randy looked at the bluff Westerner, who had proved himself such a friend to the motion picture chums.

"The Panama Exposition! Just the thing, I say!" was Mr. Strapp's exclamation. "I'm for the West, first, last and always! Anybody who knows Hank Strapp knows that. I don't know all the details, but I'm with Frank in anything he sets out to do."

"Thanks," murmured the proposer of the idea. "Better not be too rash. It will take a lot of money, I'm afraid."

"Well, we've got it," declared Pep, impulsively. "Look at it!" and he waved his hand toward the bills on the table.

"This is my idea," went on Frank, when there suddenly came an interruption, in the shape of a pleasant-faced man, who poked his head through the doorway of the office long enough to ask:

"Anything special in the way of music or effects needed for to-day's reels?"

"Oh, hello, Ben Jolly!" cried out Frank. "Come on in! This concerns you as much as any of us."

"Do you mean this—money?" asked Ben with a smile, as he entered the office.

"Well, partly," admitted Frank. "Some of it's yours. But I was just speaking about opening a motion picture theatre at the Panama Exposition. What do you think of it?"

"Great!" cried Ben, who played the music, and managed the "effects," or various simulating sounds that, nowadays, accompany motion pictures. "You'll want to arrange for an extra big pipe organ, though."

"An organ?" questioned Hank. "What's the matter with a piano out there?"

"An organ is the latest," declared Ben. "We've proved that here at the Empire. You can get better effects, especially in the 'sob reels.' I mean the ones that cause the 'weeps.' They're always effective, especially for the ladies, and when they see something sad, and hear me making slow, tremulous music on a deep-toned organ, with the lights turned low, and all the handkerchiefs in the place wet with tears—say, they'll come in droves! You couldn't keep 'em away if you said there were mice in the place, and women are more afraid of them than an elephant is. Get an organ for that new place, and I'll guarantee you'll be turning 'em away in droves! An organ there will draw better than it has here."

"Well, that's something that can be talked of later," decided Frank. "I'm rather inclined to a new and bigger organ myself. It certainly was a success here—a big success. If we can get a suitable place, in the 'Zone,' as the amusement concession space is called, we can probably have a pipe organ put in before we open. Now as to details——"

Frank suddenly interrupted himself to look at his watch.

"Whew!" he whistled. "Eleven o'clock, and the bank closes at noon on Saturday. I'll just about have time to make it, and I want to get this deposit in to-day, to strengthen our account. We have a lot of bills to meet Monday. I'll have to be off!"

He began to sweep the money into a satchel he used on his trips to and from the bank, for Frank acted as treasurer and cashier at times.

"Have you made out the pay roll?" asked Randy.

"Yes, I've left enough out of our receipts for that. I'll deposit the rest."

"But what about that new plan?" demanded Pep. "If we're going out to San Francisco I want to know it!"

"We can't decide in a hurry," answered Frank. "We'll talk more about it when I come back. But I'm glad to see that you all think well of it; so far at least."

"It's a dandy scheme!" exclaimed Mr. Strapp. "I'll be on my own stamping ground once more, if we get out West. You boys won't be sorry you came; take Hank Strapp's word for that."

"Well, if I can have an organ out there, as I have here, to play sad music on, I'll be satisfied," declared Ben Jolly, with a bright smile.

"We'll talk it all over when I come back from the bank," Frank announced, as he put on his hat and set out with the satchel of money. The others remained behind in the office.

"Films come in all right?" Frank called to one of the young operators, who was up in the sheet-iron "cage" getting ready for the day's performance, which would soon begin.

"All here, and some good ones, too," was the answer. "But say, come to think of it, has Ben Jolly any chain-rattling effect in his box?"

"I think so; but you'd better ask him to make sure," advised Frank. In the Empire, as in all first-class motion picture theatres, the musician, in addition to what effects he can produce on the piano, or organ, has a "box," or mechanical device—several of them, in fact—by which he can produce the sound of almost anything, from a thunder storm to the tinkling of a doorbell, or the puffing of an automobile.

Leaving his operator to arrange for the chain-rattling device, which was called for in one of the pictures, Frank hastened on to the bank, for it was nearly closing time.

As he entered the swinging doors, carrying his satchel of money to deposit, the young man ran full tilt into a portly, red-faced man who was coming out with every appearance of haste.

"Ha! Why don't you look where you're going?" demanded the man, rather breathlessly; for Frank's coin-filled satchel had come in violent contact with his stomach.

"I beg your pardon," Frank said, instinctively. "It was an accident. And, as a matter of fact, you ran into me as much as I ran into you."

"Nonsense! Nothing of the sort. You did it deliberately, and if I had time——"

A violent fit of coughing interrupted the man's hoarse voice.

Frank stood aside in the bank vestibule, to give the excitable stranger room to pass, but the man did not seem to want to take advantage of the courtesy extended by the young motion picture operator.

"I—I don't see what's gotten into you young puppies nowadays," the man blurted out, when he had recovered his voice. "The idea of ramming into me that way! I—I——" But words failed him. His red face grew redder, and his neck swelled up until Frank could think of nothing but a strutting turkey gobbler.

"Out of my way!" the man exclaimed. "You have no business obstructing the door like that."

"Why, I—you——" began Frank, intending to say that the man himself had been at fault, for going to the left instead of the right.

But the fellow gave him no chance. Roughly thrusting Frank to one side the man rushed past him, and out into Broadway, leaving Frank gasping against the marble sides of the bank vestibule.

"Well, of all the nerve!" the lad exclaimed, as he recovered himself, and went on into the institution to make his deposit.

While Frank is doing this I will take just a few lines to tell my new readers something about the characters who are to figure in this story, and also mention the previous books in which are set forth their exploits.

Some two years before the opening of the present story Frank Durham, Pepperill Smith and Randolph Powell had lived in the Pennsylvania town of Fairlands. As might be guessed from the little glimpse I have given you of Frank's character, it was he who first suggested motion pictures, and found a way of employing the savings of himself and his friends. They brought a motion picture theatre outfit to Fairlands, and at once became known as the "motion picture chums." So, most appropriately, I hope, I named the first book of this series "The Motion Picture Chums' First Venture." It was indeed a venturesome beginning for them, and they had many trials and tribulations, but, eventually they succeeded, and made money.

In the second book, "The Motion Picture Chums at Seaside Park," I had the pleasure of telling you how again Frank found a means of making more money for himself and friends. When the winter season in Fairlands had passed, and local trade became dull with the arrival of hot weather, Frank discovered an opening for a Wonderland No. 2, named after their first venture. In a seaside resort, about fifty miles from New York, they presented a series of films that made good.

Of course that was only a summer resort, and when visitors and cottagers departed the boys found their business gone, too. But they had been getting experience in these months, and this they put to good advantage when they founded their Empire playhouse on upper Broadway, New York City. In the volume named "The Motion Picture Chums on Broadway; Or, The Mystery of the Missing Cash Box," I related their metropolitan successes and troubles, for they had not a few of the latter.

"The Motion Picture Chums' Outdoor Exhibition" told of the film that saved a fortune, and I will leave you to find out for yourselves just how this came about.

Then Frank and his chums had a new idea. They went to Boston, opened a playhouse there, and had the distinction of showing the first real educational films; an idea that originated with Professor Achilles Barrington, a most lovable but odd character.

In Boston, no less than in other places, the chums found rivalry, but they managed to get the best of their enemies, and had a most successful season.

It was now October, and they had come on to New York to make arrangements for showing some imported film dramas, consisting of many reels, which ran the cost up very high. But even with that, they had made money. The motion picture chums had so prospered, thanks to Hank Strapp's aid, that they could afford to hire managers for their various places of amusement, which enabled them to travel about supervising matters, looking for new attractions, and providing for their patrons. They were getting the name of being among the most enterprising of the New York moving picture operators, and of being the first to adopt innovations.

I have mentioned Hank Strapp of Montana, and those of you who have read the other books of the series know what a fine character he was. I need not dwell on him.

As for Ben Jolly, he asked nothing better than to sit down in front of a piano, or pipe organ, and an "effects box," and produce music that went well with the various motion scenes shown, bringing out, meanwhile, the different sounds that added to the effectiveness of the film. Ben had perfected a little arrangement of his own which, he claimed, so perfectly imitated the barking of a dog that he had a standing offer among the employees of the Empire, to scare with his device any cat they might bring in. And he did it, too!

Sometimes Ben would have so many "effects" to produce that he took this task for himself alone, leaving his helper to play the piano or organ.

Hal Vincent, a ventriloquist and cornet player, was also an efficient and faithful helper to the boys. He was sometimes at one, and sometimes at another, of the various enterprises the chums owned, for they had, in addition to those I have mentioned, the Model at Belleview, up the Hudson.

The motion picture chums had aided and befriended many young fellows since their first venture, and some of these lads they hired to look after their interests in the various theatres. But it was to Hank Strapp and Ben Jolly that they clung most closely, and on whom they depended most for help. Ever since Frank had saved the Westerner from losing a large sum of money through a swindler, Strapp had remained with his new friends, and had invested goodly sums in their various enterprises.

Of late matters had been going excellently at the Empire, the best-paying theatre in the chain the chums controlled, and it was at a gathering of his friends to talk over matters that Frank had made the proposal about the Panama Exposition.

Then had come the interruption when he went to the bank, and the collision with the choleric man.

"Well, I like his nerve—not!" exclaimed Frank with boyish earnestness as he watched the red-faced individual make his way through the throng of pedestrians on the street. "There he goes again!" the lad cried, as he saw his late antagonist encounter a man in the street, colliding with, and nearly knocking him down. "He must have the habit," Frank went on, grimly, as he adjusted his hat, which had been knocked askew, and proceeded on to the brass-grated window of the receiving teller. "I don't like that man at all—not for a cent, and if I meet him again I'll give him a clear path.

"I'd know him again, sure!" Frank declared to himself. "I never saw a man with such a red face, and it wasn't all from anger, either. He'll have apoplexy if he isn't careful."

"Hello, Frank!" called the receiving teller, as our hero, or, rather, one of them, approached the window. "What was that chap in the vestibule trying to do; get your cash away from you?"

"Hardly!" laughed Frank. "He didn't seem very steady on his feet. Did you see what he did?"

"Yes. He was on the wrong side. He must be an Englishman; going to the left that way."

"He has an English name anyhow," remarked the paying teller, at the next window, for business was slack just at that moment.

"Did he cash a check?" inquired his fellow-employee from his "cage."

"He tried to. Signed his name—Royston—with a big flourish and said he wanted it in big bills."

"Did you give it to him?" asked Frank, as he shoved his satchel full of money in through the brass wicket, which the receiving teller opened for him.

"I did not. The check was good enough, I knew that, but I said he'd have to be identified, as he was a stranger to me. Whew! But he got as mad as a wet hen; said it was a shame and all that! Said he'd done business with this bank before. But he couldn't prove it, and I wouldn't give him the money until he made himself better known than by just endorsing a check with enough ink to make half a dozen ordinary signatures."

"Maybe that's what made him mad, so he tried to bowl me over," suggested Frank, stepping down to speak to the paying teller, while the receiving clerk was counting the cash the motion picture lad had handed in.

"Shouldn't wonder," the teller agreed. "Funny how some people get mad when you simply ask them to comply with ordinary banking rules. And I've always noticed that it's the cheap chaps; the tin-horn sports, or the man with very little money, who makes the most fuss.

"Why, I've had millionaires, strangers to me, come in here to cash checks, and when I said they'd have to be identified, they wouldn't make the least fuss about it. They'd make themselves known in a way that was satisfactory. But let some fellow come in here with a big idea of his own importance, and he gets a flea in his ear right away if I question him. That's Royston's sort, I guess."

"Royston, eh?" murmured Frank. "So that was his name?"

"Yes, and it ought to be Roysterer or Roasterer from the way he acted. Nearly knocked you down, I understand."

"Yes," answered Frank.

"Here you are—all correct," spoke the receiving teller, as he entered the amount Frank had deposited on the pass-book, and tendered that and the now empty satchel to the youth. "You're putting in big money these days, Frank."

"Yes, we're doing pretty well, thank you. Better prospects ahead, too."

"You don't say. Something new?"

"Yes, if I can make it work. Going out to the Panama Exposition."

"You don't say! Well, I'm glad to hear that, but we'll be sorry to lose you."

"Oh, I'll still bank our New York receipts here," Frank said.

"Thanks. We like to do business with you," and with a nod the teller took the deposit of the next in line, Frank making his way out of the bank.

"Whew! That Royston chap certainly gave me a bang!" remarked Frank, as he walked along. His shoulder was beginning to feel lame where the man had collided with him, and afterward whirled him so unceremoniously against the marble wainscoting of the vestibule. "I'll be stiff," Frank went on, swinging his arm about so vigorously that he nearly struck the hat of a girl walking just ahead of him.

"Oh, I beg your pardon!" he exclaimed, impulsively. "I wasn't thinking of what I was doing."

"That's all right," she assured him, with a smile and a glance from a pair of bright eyes. "No harm done."

"Guess I'll have to stop using the street as a gym," murmured Frank, as he passed on, after raising his hat.

His arm was really paining him, though he knew it was nothing serious. He was considering whether he had time to attend to some business matters in the vicinity of the bank before going back to the Empire office.

"No, I think I'd better go back," he decided to himself. "I want to see how those 'Pickwick' films are running."

For he and his chums had recently contracted for the exclusive right, in their vicinity, of showing a series of motion pictures, depicting the life of that most famous of Dickens's characters.

"And the boys will want to talk more about that Panama scheme," Frank decided. "I'll let the business stand until Monday and go back now to the theatre."

Frank was crossing Broadway at a point where traffic was unusually congested at that moment, when he noticed a rather oddly-dressed man rushing forward without any regard to the danger of passing wagons and automobiles.

"Hi there! Look out!" Frank cried in warning.

The man turned his face toward him, showing to the lad a much excited countenance. There was a wild look in the man's eyes, as though his thoughts were either far away, or as if he were reckless enough not to care what he did.

"Wait a minute," advised Frank, coming up behind the man. "The traffic policeman will hold up the machines in a little while, and you can go on."

"No time to wait! No time to wait!" was the sharp retort. "I must go on now!"

He made a dash forward just as a swiftly-moving auto swung around a corner. It was coming straight for the wild-eyed man.

"Look out!" Frank yelled, springing to the rescue with a hand extended to pull the man out of danger.

Frank managed to grasp the coat of the wild-eyed man who seemed so bent on rushing into danger. The slightly bruised arm of the young motion picture owner gave a twinge as he exerted his strength, but he did not desist.

"Hold on! What do you want to do? Get yourself killed?" demanded Frank, as he pulled the man toward him.

"I—I—oh, I don't know!" was the surprising answer. The man fairly stumbled against Frank, so great was the force of the pull exerted by the lad. And, as the stranger thus came in closer proximity to him, the youth had a chance to look at him more intently, though it was but a fleeting moment ere the automobile rushed past, its mud-guards grazing the man Frank had saved.

The youth had undoubtedly saved the man from severe injury, if not death. The automobile, a big limousine, was going at a pace that would have precluded the chauffeur from stopping it, and as it was rounding a curve, and there were other vehicles on the outside, there was no chance to turn out of the way.

"You should watch where you are going," was Frank's warning. He looked at the man, and, among other things, saw that he was without a collar or necktie. This might not have been so remarkable had it not been for the fact that the man was otherwise well dressed, though his garments showed the need of brushing and pressing.

One other thing impressed Frank: the man had on one black shoe and one tan-colored one, forming a strange contrast. But Frank, after the first quick glance, which took in these oddities in the man's attire, was most attracted and surprised by the look on his face.

"If ever there was wild-eyed despair and anguish written on a man's face I saw it there," Frank said afterward in telling of the occurrence. "The man seemed to have lost all hope."

Frank was used to dramatic episodes. He saw enough of them in the motion pictures thrown daily on the screen in the theatres, but he was not so hardened but what this scene affected him.

"Didn't you see that auto?" he asked of the man, as he released his grip on the coat sleeve, and picked up the satchel he himself had dropped.

"No, I didn't see it, and I—I don't much care! I might just as well be dead as in the fix I'm in. Oh, why didn't you let me go?" he begged, piteously.

"Don't talk that way!" said Frank, sharply.

"Oh, I'm thankful to you, of course," the man went on. "But I——"

A policeman strolled up, drawn by the little crowd.

"What's wrong?" the officer asked, curiously.

"Oh, it's all right now," Frank said, with a smile. "This gentleman was in too much of a hurry, and tried to get in the way of an automobile. This is a busy corner!"

"Indeed it is, young man," agreed the officer. "Not hurt; are you, sir?" and he looked at the man Frank had saved. Then the oddity of the stranger's attire impressed the policeman, and he winked his left eye at Frank, as though to say that the individual might be "a little off in the upper story," as Hank Strapp expressed it later, on hearing the tale.

"Oh, no, I'm not hurt, thanks to this young man," responded the stranger. Then he mumbled something to himself, and put his hand to his head in a dazed sort of way. A moment later he pulled away from the light grasp Frank had, almost unconsciously, held on his arm, and darted across the street.

Before he went he suddenly exclaimed:

"Maybe there's a chance yet! I must save it before they get it all, or I shall be ruined. I never will dare go back and face him! Oh, what a loss! What a loss!"

He darted across the street, under the very noses of cab horses, and right in front of several autos, one of which drew up with such a sharp application of brakes that the big rubber tires slid on the pavement.

The officer and Frank looked at one another knowingly.

"Something queer, there," remarked Frank.

"I should say so," agreed the policeman. "Did you take note of his shoes—one black and the other tan?"

"Yes; and without a collar or tie," added Frank. "He surely is wrong somewhere."

Then the youth passed on, the officer went back to his post, and Frank almost forgot the incident, though it was destined to have a strange effect on his future.

"Well, what about your exposition plans?" asked Randy, when Frank returned to the Empire office.

"Yes, let us hear something," added Pep. "If we're going to do business out there we'd better get started."

"Well, of course I haven't it all worked out yet," replied Frank, "and, as was the case with all the plans we have made, this one is also subject to the approval of you three," and he looked at his friends. In times past they had done nothing without acting in perfect harmony, and though often one of the boys would be set on doing something, he gave it up if there was not an unanimous vote in its favor. Perhaps this explained the success of the motion picture chums.

"Oh, we'll be in favor of it, if there's any money to be made at it—provided, of course, that it's all right," said Randy.

"Sure thing!" agreed Pep. "What's the matter with your arm?" he asked, as he noticed Frank wince a little. "Strain it carrying so much money to the bank?"

"Not exactly," answered his chum, "though it was in the bank it happened," and he told of the Royston incident, and also of having saved the apparently demented man from injury.

"Say, you're getting as exciting as a moving picture reel yourself," spoke Hank. "First you bang into an angry man, and then into a lunatic. But sit down and tell us what's what."

"It's simple enough to tell," replied Frank, as he looked over some mail that had come in. "I thought if we could get a concession in the amusement Zone at the exposition, we could open a motion picture theatre there and make some good cash during the months the big fair is under way."

"Would you have that extra big organ I spoke of?" asked Ben Jolly, for he had come into the office during an intermission. "I've gotten so used to this one here that I wouldn't know how to get along without one."

"Oh, yes, I guess we'll have to get you the new organ," agreed Frank, smiling.

"But look here," said Pep. "We'll have to show some pretty classy reels to the kind of audiences we'd cater to out at the fair. We couldn't run that Snakeville stuff, and the 'Dangers of Desdemona' never-ending episodes. The people out there will want more solid meat."

"I agree with you," said Frank. "We'll have to go in for real dramas, played by Broadway stars. With that, and with some foreign things I am negotiating for, I think we could make up a bill that would bring the crowds. Of course we'll have to have humorous stuff, too, and short light comedy reels to fill in with. Now I've done all the talking, and it's up to you fellows. What do you say?"

"I say it's dandy, if I can have a specially made organ and a good effect box," said Ben Jolly.

"I'm willing to invest my share in the plan," agreed Randy.

"It's great! That's what I say!" cried Pep, with his usual impetuosity. "Let's start right off!"

"We haven't heard from Mr. Strapp yet," said Frank, with a smile at the big ranchman.

Strapp slowly uncoiled one leg where it had been crossed over the other. He took from his pocket a newspaper he had been reading, and said impressively:

"Well, boys, I'd like to go in with you, but I don't believe it can be done. You're too late!"

The motion picture chums looked wonderingly at one another. What did the Westerner mean?

"Mr. Strapp, you'll have to explain," spoke Frank, slowly, as he looked at the former ranchman. "It isn't like you to say something like that, and then let us guess at your meaning."

"And I'm not going to this time, either," declared the Westerner. "That isn't Hank Strapp's way. I'm going to explain."

But he seemed in no hurry to do this. He carefully unfolded the newspaper he had taken from his pocket, and began leisurely to look over the printed pages as if in search of some item. He was so deliberate about it that Pep, with his usual impetuosity, exclaimed:

"Say, we couldn't get up a motion picture of you making an explanation, no matter how we tried!"

"Is that so, son? Why not?" asked the man from Montana, drawlingly.

"Because you don't move fast enough, that's the reason," said Pep, quickly. "Come on, let's hear why we can't go to the Panama Exposition, and open a motion picture place in the Zone, as Frank plans."

"Because it's too late," declared Strapp. "Here's a piece in the paper that tells about it. I thought I should find it. It says that the Zone has proved so popular as an amusement place that all the concessions have been snapped up. There's everything out there from an old time Forty-niner's gold camp, to an upside down pendulum that lifts you up nearly 270 feet, and from toy towns to a giants' cave. But every concession is gone, this article says, and that's why it's too late for us to think of opening a motion picture theatre there."

For a moment there was silence in the office of the Empire. Then Frank said:

"Let's see that article, Mr. Strapp. Maybe it isn't as bad as you make out."

"Oh, I'm not trying to make it out bad," was the answer. "I'm as anxious to go out West as you fellows are; more so, in fact, for I sure would like to get astride of a pony once more, and feel the wind in my face. But I don't want you to go out there and be plumb disappointed. That's why I'm speaking against it."

Frank was busy reading the article in question. As he perused it his face brightened, and finally he exclaimed:

"Say, this may be all right, after all! It doesn't say with any official authority that all the concessions are taken up."

"What do you mean—any authority?" asked Randy.

"I mean this doesn't come from anyone in authority at the fair. It's just written by some reporter, who probably guessed at his facts. I'm not going to be hindered by this."

"You're not?" cried Strapp. "Do you mean to say you're going to move this outfit—and all of us—out to the Panama Fair, when it says in the paper we can't get space?"

"Well, I'll make some inquiries first, of course," answered Frank, with a smile, "but I'm not going to back out because of this," and he tapped the folded paper.

"Well, you've got me beat!" Hank Strapp had a great respect for printed matter. For a long time he had accepted as true everything he saw in the papers, until the boys had laughed it out of him, to a great extent. But he still had some of his faith.

"If this came as a statement from the fair managers I'd take more stock in it," said Frank. "As it is—it's only a rumor."

"Well, maybe you're right," agreed Hank slowly. "But if I were you I wouldn't lose any time. There must be a good call for space in the Zone, or such articles as this wouldn't be printed."

"I agree with you," spoke Frank. "And we've got to hurry out there and clinch matters. I really didn't think there was such need for haste; but I believe it now. We'll get out to San Francisco as soon as we can, and see about fitting up a theatre there. I'm sure it will be a money-maker."

"But can we draw the crowds with so many other things going on?" asked Randy, who was inclined to be cautious.

"Of course we can!" declared Pep. "Didn't we draw 'em in the hot summer, when there was bathing and other attractions along the board-walk? Of course we did. And that Zone will be open day and night, and for a long time. Of course we'll make money!"

"It will draw better if we have the right kind of an organ," put in Ben Jolly, who had another "resting spell." Then he went on: "There's a new kind, with special stops, and——"

"Oh, we'll have the organ, all right," declared Frank; "that is, if we have anything at all. And now I'll tell you what I'm going to do, if you all agree with me," he went on. "I'll just telegraph out to the Zone management, and see what space they have left, telling them what we want. Then we can decide what to do."

"Good idea!" cried Pep. "And prepay the reply, so we won't be held-up, waiting."

"I'll do that," agreed Frank. "And now we have a lot to do if we are to go to the big fair."

Indeed there was plenty of work ahead, if they could carry out their latest plans, and, in order that the chances might be good for doing this, Frank's first care was to send off the telegram.

Then, while waiting for an answer, he had to look after some details connected with the various other motion picture playhouses they operated. The chums were also busy with several matters.

Each day there came, by mail, to the Empire office, a statement of the previous day's business at each of the resorts. The receipts and expenditures were given in detail, and Frank also insisted on a report as to how the various reels were enjoyed by the patrons.

In this way he learned what "took," and what was not acceptable, and this governed him and his friends in their selections. Most of the reports had been gone over that morning before Frank broached his new plan, and before the various encounters in going to the bank. Now it remained to consider them.

So, after the telegram had been sent, and while the afternoon performance was well under way in the Empire, the three chums and Strapp considered matters connected with the two Wonderlands, the Boston place and the Airdrome, which had not yet closed for the season.

"The Boston place is doing better than I expected," said Frank, as he glanced at the report. "The crowds are taking better to strictly amusement films than we hoped. We can't always be running educational reels, you know."

"I should say not!" cried Hank. "Why don't you try them on a few Western dramas—cow-punching and the like?"

"It's a little too soon for that," remarked Frank. "I'll go a bit slow. But we've got to do something for the Airdrome. The attendance there is falling off."

"Send Hal Vincent up," suggested Randy. "He can put on that new ventriloquist act of his. That's always popular."

"I think we'll do that," agreed Frank.

"And try the scheme of giving a box of candy to the lucky ticket holder," advised Pep. "That's always a drawing card. All the admission tickets are numbered, you know. We can get them in duplicate just as well, the person to hold one end, and the other to go in a hat. At the end of the performance someone draws out one of the duplicate stubs, and whoever has the same numbered ticket gets the box of candy."

"Good idea!" decided Frank. "It's been done before, but it's always good. Write and tell 'em to do that up there, Randy," he went on, for Randy had been acting as secretary of late.

Then other matters connected with the business were considered, letters were written, new films were ordered, advertising schemes were talked over until, finally, it was six o'clock, and the chums left the Empire to go to dinner.

"No answer yet?" asked Pep of Frank, when they had come back to the theatre, for they made it a point on Saturday nights, when in New York, to see, personally, to the putting away of the day's receipts, which were generally heavy.

"Nothing from San Francisco yet," answered Frank. "But give 'em time. They're probably pretty busy out there."

It was nearly closing time for the Empire when a messenger came shuffling up to the office with the looked-for telegram. Frank, Pep and Randy were together, Ben Jolly being engaged at the organ, and Hank Strapp reckoning up accounts with the ticket seller.

"I hope it's good news," murmured Randy.

"It's got to be!" declared Pep, impulsively.

Frank tore open the envelope.

"'Some space left,'" he read. "'Would advise haste in making a selection.'"

"Humph!" murmured Frank, as he passed the yellow slip over to Pep. "He didn't waste any words. Well, it's encouraging, to say the least. Now, fellows, it's up to you. What shall we do?"

"Go, of course!" was Pep's quick answer.

"I think we could make a success of it," spoke Randy, more quietly.

"It will mean that we'll have to go out there right away," said Frank. "We've got to act quickly."

"The quicker, the better!" was Pep's comment. "Things are in shape here so we can leave; aren't they?"

"Oh, yes," Frank answered. When, a little later, the Empire had closed until Monday morning, there was a gathering of the chums and their two friends, Ben Jolly and Hank Strapp, and the decision was reached that they should at once start for San Francisco.

"Monday night will see us on our way," declared Frank, at the conclusion of the conference. "We can close up all matters here by that time."

"Can't we reserve space in the Zone by wire?" asked Pep.

"I suppose we might," said Frank, "but it would be rather risky. I'd rather see what we're getting. Sometimes being on the wrong side of a street will spoil the success of a motion picture place. And if we reserved a place by telegraph we'd have to accept it. No, I think we'll have time enough after we get out there. It will only take five days if we have good luck."

Monday was a busy time for the motion picture chums. They had to turn over the management of the New York theatre to others, though this was comparatively easy, as it had been done before. Then financial matters had to be arranged, for they would need to take a considerable sum to San Francisco with them.

Frank went to the bank to transact some business.

"Well, you didn't meet your friend; did you?" asked the teller to whom he stopped to speak before leaving.

"What friend?" asked Frank, his mind busy with other matters.

"I mean the one who collided with you Saturday."

"No, he doesn't seem to be on hand to-day," was the reply. "And say, he wasn't the only freak I ran into that day."

"No?" asked the teller, with interest.

"I pulled a man from in front of an auto out in front of the bank shortly afterward," said the youth, as he narrated his experience with the oddly-dressed man.

"Well, you sure had your hands full," observed the teller.

Finally matters were in such shape that the motion picture chums could prepare to leave for San Francisco on the midnight train. That there was need of haste in picking out a place in the Zone was borne out by articles in that day's papers, telling how near the Panama Exposition was to opening, and what a wonderful place the amusement section would be.

Trunks and valises had been hurriedly packed, tickets purchased and Ben Jolly had played his last improvisation on the Empire piano—at least his last in some time, he hoped.

"I'll be fingering that big organ next, I hope," he said.

Frank had made tentative plans for reserving options on some exclusive films he expected to show at the fair, if he could get space. The other chums had done their share in arranging for the hurried departure, and Hank Strapp as usual gave valuable assistance.

"And now we're off!" cried Pep, as they went toward the sleeping-car which was to be their home for several days in the rush across the country.

"Yes, we're off," said Frank.

It was almost time for the train to leave, when looking out of his window Frank saw a portly, red-faced man hurrying along, two porters carrying his valises.

"If I don't get the best berth in the car you fellows won't get a cent out of me!" the man exclaimed in surly tones. "Why don't you get a move on! You walk as though you were stepping in molasses!"

"Yais, sah!" murmured one of the men, deferentially.

At that moment the train started to pull out, and one porter, giving his valises to his companion, seized the passenger by the shoulders and began pushing him forward on the run.

"Here! What do you mean? How dare you!" cried the portly passenger. "Let go of me at once!" he ordered.

"No, sah, boss! I dassn't do it!" was the reply of the grinning porter who had him by the shoulders. "Keep movin', 'cause I'se suah gwine t' keep shovin'."

"But I say! Look out! I won't have it! I won't have it, I tell you!" objected the stout, red-faced man. The motion picture boys, attracted by the commotion, had looked from their windows, for their sleeping-car was close, and the sashes had been lifted before the train started.

"Can't let yo' all miss yo' berth, boss!" explained the porter who was shoving the man along. "Come along wif dem bags, George. I'll git him abo'd somehow, ef I has t' carry him. Cain't affo'd t' lose no tips dese yeah hard times! Now, den, sah!"

With a mighty heave the porter, with the help of a brakeman, lifted the portly man up on the steps of a sleeping-car. The car-porter, willing to oblige his fellow-employees, had kept the vestibule door open, and the platform that covered the steps was up, or otherwise the feat could not have been performed.

But, as it was, the belated passenger was fairly forced aboard the train, and not a moment too soon.

"Why—why——" he panted. "If you fellows——"

"Chuck up dem valises, George!" ordered the panting black man who had so hurried his charge. "Dere yo' are, sah. You didn't miss yo' train, an' Henry will see dat yo' gits a good berth; won't yo', Henry?"

"Dat's what I will, sah!" laughed the car-porter.

Frank and his chums, by leaning out of their windows, had witnessed the conclusion of the little comedy. And yet it was not wholly over. For the two platform porters stood expectant.

The portly man, breathing hard, stood in a dazed manner on the platform, hardly knowing whether or not he had "arrived." But he was safely on board the moving train, and his baggage was at his feet. The two platform porters held out their hands significantly.

"No, you don't get anything from me!" stormed the stout man. "I won't be handled like a dog, and then give up good tips for it. No, sir!"

"'Scuse me, sah, but yo' all had better go inside," broke in the car porter, and, as he stooped over to pick up the satchels he, accidentally, or otherwise, hit against the closed hand of the man. From the fist there flew out a bright half dollar, that fell, with a ringing sound, on the concrete platform alongside the train.

"Thank you, sah!" chorused the two grinning colored men, as one of them picked up the rolling coin.

"Well!" exclaimed the man. "Of all the——"

But the rest of what he said was not heard by Frank and his chums, for the car-porter hurried his charge inside and closed the vestibule door.

"Well, if that wasn't the same man——" began Frank, as he drew his head in from the window.

"What's that?" interrupted Pep.

"I thought I knew that man," said Frank, more slowly. "But I guess I was mistaken. He surely was fussed up, though."

"But the porters got what they wanted—their tips," remarked Randy. "Well, now we're settled down for a long ride."

"With success at the end of it, I hope," remarked Frank. "My, but we have done some hustling this day!"

Indeed they all had, including Ben Jolly and Hank Strapp. But as Strapp himself said, he was used to it, for he liked nothing better than to have to do something in a hurry. It reminded him, he said, of when he was actively engaged on the ranch, or in some of his mining ventures.

"And in those days you had to be up pretty early to get ahead of Hank Strapp!" exclaimed the breezy Westerner.

"I guess anyone would have to, even yet," said Pep, with a laugh.

As he went to bed a little later, the porter having made up the various berths, Frank could not help recalling the scene of the portly man who had been so hurriedly helped aboard by the colored men.

"If it's the same one. I'm just as glad he isn't in our car," he murmured, as he dozed off.

"Well, this is some different from the time we had in Boston," observed Randy the next morning, as his chums, with Strapp and Ben, were sitting together, planning to go to the dining-car for breakfast.

"I should say so!" agreed Frank, looking out of the window at the swiftly-moving scenery. They had been carried along all night, and were now well on their way West. "Well, I hope we don't get mixed up with any fires, or lost camels, or anything like that," he went on. "There are some busy times ahead of us, to my way of thinking, if we can get the concession we want, and start our motion picture place."

"Yes—if we can get a concession," agreed Mr. Strapp. "But I'm thinking you'll have trouble there."

"Might as well be cheerful while you're about it," suggested Ben, drumming with his fingers on the window sill, as though strumming a piano at a performance, or producing some of his wonderful pipe organ effects.

"I don't want you boys to be too disappointed," was Strapp's answer. "I'd rather look on the dark side, and be agreeably surprised by a silver lining to the cloud, than think we'd found a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow and, later on, have it turn into lead."

"I think things will be all right," spoke Randy. He was of a hopeful disposition.

"Well, I hope we have ham and eggs for breakfast," broke in Pep. "And I'm going to find out right away. Who's with me?"

"I am!" cried Ben Jolly, and the party of five started for the dining-car ahead, where, as a white-aproned porter had announced, a short time before, breakfast was being served.

As Frank was leading the way to two tables, where he and his friends could be accommodated, there came out of the farther end of the car a burly, red-faced man.

At the sight of him Frank stopped, and stared rather boldly, at the same time murmuring in a low voice:

"It is he! It's the same one. I wasn't mistaken!"

At that moment the train rounded a curve, and Frank, making a grab for the edge of a table to steady himself, missed his hold. He was thrown rather violently against the stout man, who gasped as the breath was jarred from him.

"I beg your pardon," said Frank, recovering his balance.

For a moment the man did not speak—he could not, in fact. Then, as his breath came back to him he gasped:

"You—you'd better! The idea—careening into me that way. What do you mean? You ought to look where you're going!"

"He couldn't help it, sah," interposed a waiter. "Pow'ful bad curve right yeah, sah. Passengers done has t' look out fo' derese'ves. Pow'ful bad curve!"

"That's no excuse for walking all over a man," growled the portly individual, scowling at Frank. At the same time Pep nudged Randy, and whispered:

"That's the same one who had the fuss with the porters last night."

"So I see," responded Randy. "He seems to have a perpetual grouch on."

"That's what," agreed Pep.

By this time the portly man had straightened up. He was about to pass on when he looked at Frank more closely.

"Hello!" he half growled. "I've seen you before!"

"Possibly," admitted Frank.

"Indeed I have," went on the man. "You ran into me once before, a few days back. I haven't forgotten it, either. It was in a bank. You seem to have a bad habit, young man," he sneered.

"That was an accident, just as this was," responded Frank, and his voice was decidedly formal. "In fact, on the other occasion it was you who ran into me. This time it was not my fault. The train threw me."

"Bah! You're careless!" declared the man. "Keep out of my way!" and he lurched on to his seat at a table.

"Yes, that's the same man," said Frank to himself, though not so low but that Pep heard him.

"What man do you mean?" he asked.

"The same one I ran into at the bank on Saturday," Frank explained. "His name is Royston, so the teller told me."

Frank's voice was louder now, and as he mentioned that name a gentleman seated at an adjoining table turned quickly and looked at our hero. There was something in his look that made Frank glance at him a second time. The man seemed to convey a warning.

Frank was so impressed by the look on the stranger's face that, for a moment, he almost made up his mind to speak to him, though he had never seen him before. The man who had thus given Frank the glance of warning was a quiet-looking person, as soberly dressed as his manner was restrained. Yet his clothing was expensive and he seemed to be a cultured gentleman.

Evidently something in Frank's manner must have conveyed to him that the young man had it in mind to speak, for once again catching Frank's eye, the man slowly shook his head, as though to discourage any opening to an introduction, at least just then.

"I wonder what he means?" thought Frank to himself. "He heard me mention the name Royston, and he looked interested. Well, I guess I'll go a bit slow."

The unpleasant incident of the chance encounter with the man Frank had collided with in the bank, gradually passed away. The chums and their friends busied themselves about ordering a substantial breakfast, Pep getting the ham and eggs he had specified.

"And that's the fellow you had the row with?" questioned Randy, as there came a pause in the clatter of knives and forks.

"Not so loud," cautioned Frank, for the train had come to a stop, and there was silence in the dining-car. "He'll hear you."

Indeed the portly man was looking, at that moment, around at the tables where sat our friends. But if he heard what Randy said he gave no sign, and went on eating.

He was a most particular person, for he ordered several dishes and after inspecting them through his nose glasses, sent them back, to the no small annoyance of the waiter. Finally the manager of the car himself came up, and there ensued some rather warm talk.

"Well, I know what I want, and I'm going to have it if I pay for it!" stormed the portly man. "You fellows can't bluff me! You're a set of legalized robbers, anyhow, in this Pullman service!"

The manager and the waiters were probably used to such unfair treatment, for they did not reply. Frank looked at the quiet man at the table just beyond him, and again was aware of an unexpressed signal of warning in the steelly blue eyes that looked into his.

"I wonder what it means?" thought Frank. "I'm going to find out before I'm much older, though. There is something queer about this man Royston, of that I'm certain."

Breakfast was almost over, and yet the friends lingered at the table, for they had much to talk about. Their start for the big fair had been very sudden.

Pep wanted Frank to send another telegram, en route, telling the manager of the Zone concessions that they were on their way to pick out a place, and to urge him to save one for them.

But Frank, and the older members of the party also, decided that too much risk was involved in this, and agreed that it was better to wait until arriving on the ground.

"Well, there's nothing we can do except look at the scenery," remarked Randy, as he prepared to rise from the table.

"Look out!" suddenly exclaimed Frank, for, at that moment, Royston was coming down the aisle, on the way back to his coach. Frank had felt the train about to take another curve, and he did not want his chum to have an encounter with the crusty man.

As it was, Royston swayed as he came near Randy, and, only for the fact that Frank pulled his chum to one side, there might have been a collision.

"Humph! You young fellows always seem to be getting in the way," grumbled the red-faced man. "But maybe it was my fault this time." He made a pretense at smiling, and it was evident that he was in better humor since his breakfast.

"Yes, there seems to be a lot of bad curves around here," observed Strapp, always ready to be friendly with everyone. "Are you going far, sir?"

"All the way to 'Frisco," replied the man. "How about you folks?"

He seemed decidedly friendly now.

"Oh, we're going there, too—to the Fair," replied the Westerner.

At that moment Frank caught sight of the face of the quiet man, still seated at his breakfast, and Frank was sure he saw the man shake his head in negation, as though he wanted to convey the idea that it was best not to get acquainted with the portly man.

So sure was Frank of this that he decided to make use of his impression, so, accordingly, he interrupted with:

"Oh, Mr. Strapp! There's something I want to ask you about. I almost forgot it. Come back to our car. I may have to write back to New York and we can mail the letter at the next stop."

"Oh, all right," said the unsuspicious Westerner. "I thought we attended to everything back East."

Hank Strapp was already speaking of the East as though he was well out West.

"It's just a little matter," said Frank. "It won't take long."

The man Royston looked at Frank a bit suspiciously, as though he suspected the conversation was manufactured on the spur of the moment, but he said nothing. Instead he closed his lips over the utterance he had half formed, and went on his way out of the dining-car.

As Frank walked past the quiet man he saw the latter carefully extend a slip of paper, in the shadow of the cut-glass water carafe on the table. Without looking at the slip Frank managed to pick it up as he passed, none of his companions being aware of his action.

Back in their own coach Frank did consult with Hank about a certain matter concerning some films they had leased. And when this was over, and Randy was writing a letter, to be dropped off at the next station, Frank found time to look at the note the quiet man had passed him. It was brief. He read:

"Make a chance to see me alone, if possible. I want to warn you."

The note was signed "Richard Bullard, United States Secret Service."

"Whew!" whistled Frank. "I wonder what's in the wind now? United States Secret Service, eh? That sure is going some, as Mr. Strapp would say. I wonder what I'd better do?"

In a moment Frank had made up his mind that there was but one thing to do—to obey the instructions given in the note. At first the young man was in two minds about taking some of his friends into his confidence. Then he decided against that course.

"If it amounts to anything at all, I can tell them later," he said. "And, on the other hand, if it isn't anything, I can slide out of it all the easier if I haven't made a fuss over it and told them all. Yes, I'll just keep quiet about it, and see Mr. Bullard alone."

It was not easy to make this opportunity, for Randy and Pep wanted to talk with him on many subjects, and they would not leave him alone for any length of time. It was easier in regard to Hank and Ben Jolly, for they were content to sit by the window, now and then gazing out at the scenery, or dozing off. The farther West the train proceeded the more Strapp became interested. He was continually seeing some point of interest that connected itself with his past life in the land of the plains.

Finally, however, Frank found an opportunity to stroll out of his car. He had seen Mr. Bullard nod toward the coach in front of the dining-car, and Frank believed the Secret Service man had his seat in there. The coach of the chums was in the rear of the dining-car.

Frank made his way forward, and as he passed through the dining-coach he encountered, in the buffet, or lunch-room end of the vehicle, the portly, red-faced Royston, who was eating a sandwich.

"Hello!" he exclaimed, on sight of Frank. "I'm eating again, you see!"

"Yes," responded Frank, but his voice was not at all cordial.

"I always eat between breakfast and lunch," Royston went on. "It keeps me from getting run down."

A look at his portly frame did not disclose any evidences of the "running down" to which he referred. Frank passed on, taking good care to keep far enough away from the unpleasant passenger so there could be no excuse for the claim of another collision.

"What part of the fair are you making for?" asked Royston, pausing with a sandwich half way to his mouth, as Frank passed on.

"We haven't decided yet," was the answer, and Frank heard the stout man grunt. Whether this was because of the shortness of the answer, or because a lurch of the train threw the heavy man against the side of the buffet, Frank did not stop to determine.

The youth passed on into the next coach, and looked about. Almost at once his eyes rested on the face of the quiet man, who seemed to be on the watch for him.

"I am glad you came in," said Mr. Bullard. "First I must apologize for the manner in which I forced myself upon you, but I am trying to do you a service."

"That's all right," said Frank, easily. "I appreciate your efforts. Am I right in thinking your warning has to do with Royston?"

"Ah, I see you know his name then, or, rather, one of them," replied Mr. Bullard. "Yes, it has to do with him. Now I don't know you, or your friends, but I do know this man. And I don't know your plans or business, and I can't say I know all of his. But I do know enough about him to warn you against having anything to do with him. I can see that, in spite of his grouchiness, he is aiming to get better acquainted with you, for his own objects, doubtless. Are you annoyed that I should speak this way?" he asked.

"Not at all," replied Frank, cordially. "In fact, I want to thank you. I haven't liked that man since I first met him."

"Do you mind telling me how you did meet him?" asked the Secret Service man. "Not that it's any of my business," he added, quickly. "But I am on that man's trail, and——"

"Is he an escaping criminal?" asked Frank, quickly, all his suspicions coming to the fore.

"Not exactly, as yet, though he may be," was the reply. "I am keeping him shadowed, as we call it. He doesn't know me, and I don't want him to suspect. That is why I asked you to come to me secretly. I know this man to be unprincipled. One of the names he goes by is Bradley Royston. It is sufficiently aristocratic for his purposes at times. But you haven't told me how you came to meet him."

"It was in our bank," Frank explained, and then he went into details of the encounter with Royston, speaking of the refusal of the man to properly identify himself to the paying teller.

"That would be just like him," said Mr. Bullard. "Now I want to warn you and your friends to have nothing to do with him."

"What sort of a man is he?" asked Frank.

"He poses as a promoter of theatrical and other amusement enterprises," replied Mr. Bullard, "but nearly all of them have been of questionable character. The government is after him now on suspicions of using the United States mails to defraud—selling stock in fake amusement places is one of his specialties.

"I have been assigned to work up a case against him, but, so far, I have not succeeded very well. But I am not giving up.

"As I said, I don't know your affairs, nor what your business is, but I do know about Royston."

"We're in motion picture enterprises," volunteered Frank.

"Ah, that accounts for it!" exclaimed Mr. Bullard. "He had——"

At that moment, around the curved passage that led to the smoking compartment, came Royston himself. He glanced sharply at Frank and the Secret Service man.

"No good, eh?" exclaimed the suspected man in a voice that made Frank fear at least part of the conversation had been overheard. "No good!" and the man looked fiercely from his little blood-shot eyes.

"We—er—that is, my friend and I were discussing——" began Mr. Bullard, and Frank was wondering whether his new friend would dare to admit the truth.

"I know what you are discussing!" exclaimed Royston, with an air of fierceness. "You don't need to tell me!"

"We certainly are in for a row!" thought Frank. "And if I'm any judge of this man, by past performances, he'll come to a personal encounter."

Frank glanced at the government agent, and was glad to note that, in spite of his rather small size, and notwithstanding that he was of a quiet nature, he looked fully capable of taking care of himself. As for Royston, while big and burly, he seemed to be "short-winded," an almost fatal defect when it comes to athletic matters.

"Yes, indeed, I know what you were talking about!" exclaimed the suspect, and his voice was harsh. "It's the dining service on this train! It's the worst I ever struck, and I've gone back and forth across the continent a number of times. But this is the worst ever! I don't blame you for saying he's no good—the man in charge. I've told him so myself, and I'll tell him so again! I'm glad you agree with me!"

Both Frank and Mr. Bullard could not refrain from giving each other glances of relief. It was so different from what they feared. Royston had heard part of their talk, but he had assumed it to be in line with his own thoughts, and it was just as well. It had been a lucky escape for Frank and his new friend.

"Bah! Never saw such meals! Never!" went on Royston, making a wry face. "It's a shame and disgrace to the railway interests of the United States. If I wasn't in such a hurry I'd take another line, though that might be as bad. I'm anxious to get to 'Frisco. I understand you are interested in motion pictures," he went on to Frank, and all trace of annoyance seemed to have vanished from his manner. In fact, he was friendly, or he had the appearance of so being. If he held any hard feelings against Frank for the encounter in the bank, they were forgotten, or laid aside, for the time being.

"Yes, I am interested in motion pictures," admitted the young man.

"I'm in somewhat the same line, only on a bigger scale," boasted the red-faced man, and Frank could not help thinking how much he looked like an important turkey gobbler, from the manner in which he puffed himself out.

"I hear you have a number of theatres," went on Royston, "and it may be that I can throw some business in your way—trade that is too small for me to bother with," he added with an important air.

Frank was wondering where the man had heard about him and his business affairs. The young man rather resented the manner in which the other behaved toward him.

"However, we'll discuss that later," went on Royston, as though the whole matter was in his hands. "I'm going to think of other affairs now. Perhaps you gentlemen will join me in a cigar," he added, holding out a case filled with dark Havanas, and waving his hand toward the smoking compartment.

"I don't use them," said Frank, with as friendly a smile as he could muster, "but don't let me keep you," he added to Mr. Bullard.

"Yes, I don't mind having a smoke," agreed the government man, with a look at Frank which the latter well understood.

"I'll go and join my friends," Frank said, and he started back to his coach, leaving the two men together.

"That was a lucky escape," murmured the young man to himself as he passed out of sight. "I thought sure he had heard us talking about him. Well, this may give Mr. Bullard the very chance he wants to get a line on this fellow. I don't like his being so friendly, though. I wonder who has been talking about our business?"

Frank learned, a little later, when he went back to his friends.

"That red-faced, colliding man of yours was here a while ago," volunteered Pep.

"Oh, you mean Royston?" said Frank.

"Yes, and say, I guess I put a flea in his ear all right," and the quick-tempered youth chuckled.

"A flea in his ear?" questioned Frank.

"Yes. He was doing a lot of talking about motion pictures, saying what a back number they were becoming, and how other amusement things were crowding them off the boards. I guess he didn't know we were in that line, but he soon found out."

"Then you told him?" asked Frank, now guessing where Royston had received his information.

"Of course I told him!" exclaimed Pep. "I let him know what a business we had built up in motion pictures, and that it wasn't a back number by any means. I said you were one of the best-informed fellows in the country on the subject, and when I let him know how many places we had in operation he rather opened his eyes."

"Oh, so you told him all that?" asked Frank, quietly.

"Sure!" exclaimed Pep. "Why, wasn't it all right?" he asked, for something in Frank's voice made his chum glance up quickly.

"Oh, well, yes, I suppose so," was the reply. "He'd have found out, sooner or later, anyhow."

"Say now! Look here!" cried Pep. "I haven't gone and put my foot in it; have I?"

"Oh, no, indeed," Frank hastened to assure him. "It's all right. Only I was wondering where Royston got his information."

"Didn't you want him to have it?" Pep's voice was anxious now, for he and Randy depended a great deal on their older chum.

"Really it doesn't make a bit of difference," Frank said, earnestly, and he realized that he must convince Pep of this, or there might ensue complications he could not foresee. He did not want his chums to know too much, just yet, about the character of Royston. It might spoil Mr. Bullard's chances.

"Oh, I was afraid I had done something wrong," said Pep, with an air of relief. "But this fellow—Royston, you say his name is—he was quite interested. He's going out to the Zone, too."

"I hope you didn't tell him we were looking for a concession there!" exclaimed Frank, and this time there was genuine alarm in his tones.

"No, indeed, I didn't; did I, Randy?" appealed Pep.

"No, we fought shy of that, though I think he tried to get information out of us," spoke the other chum.

"Oh, I'm foxy enough for that," went on Pep, with a laugh. "I haven't forgotten the airdrome business."

He referred to an incident that occurred some time previous, when they had planned to open a certain moving picture place, and Pep, in his inexperience, had boasted of their proposed plans. The result was that some rivals heard of it, and, as they had not clinched the bargain, the place was rented to their rivals over their heads, causing them considerable trouble. Pep was to blame for that, and it taught him a lesson.

"Don't talk of our plans," cautioned Frank. "What Royston doesn't know about us won't harm him, or us. He knows we are interested in motion pictures, and that we are going to San Francisco. He may guess that we want to open at the fair, but let it be only a guess. Steer clear of him if he tries to get any more information out of you."

"Do you think he will?" asked Randy.

"There's no telling," Frank replied.

During the remainder of the railroad trip the boys saw comparatively little of Royston. Between him and Mr. Bullard there seemed to have sprung up a sort of friendship, which, Frank assumed, was, on the part of the government man, at least, maintained for purposes of his own. But Frank was only too glad that Royston did not try to get information from himself and his chums.

The trip across the continent was without incident worth chronicling save that they were somewhat delayed by a freight wreck. But finally their train pulled into Oakland which is just across the bay from the wonderful city of San Francisco. To reach the latter place it is necessary to take a ferry, and this our friends proceeded to do.

"Look me up, boys. I'll be at this hotel," and Royston with his blustering manner, intended for hearty good-nature, thrust into Frank's hand a card with the name of a certain "sporty" hotel on it. "I'll see you later," Royston called to Mr. Bullard, who had walked with the boys, leaving the suspected man to look after his baggage.

"Yes, I think you will see me later," murmured the Secret Service agent.

It was early morning when the train arrived in Oakland, and waiting only to get a light breakfast and to see that their baggage would be safely transported after them, the boys, saying goodbye to Mr. Bullard, and promising to look him up later, went down to the ferry. They looked with interest at the various sights, new to them, glancing at Goat Island, as they passed it and headed for the ferry slip, near the dock of the Southern Pacific Railway.

A little later they were out on busy Market Street, with the hum and roar of a great city all about them. But they were used to New York, and it did not seem at all strange to them. Only the climate was different.

"Well, what's the game, Frank?" asked Pep, as they stood looking about.

"Get to a hotel, and then start for the fair grounds," was the answer. "We can't arrange about space any too soon."

"That's what I say!" exclaimed Hank. "We don't want to get left."

"And you won't forget about the organ; will you?" asked Ben Jolly.

"No, indeed," promised Frank. "You shall have that, Ben."

The boys had the address of a small hotel hear Lafayette Square which they thought would suit their needs. And it would not be far from the exposition grounds. There was a street car line which went down Fillmore Street, directly into the Zone concessions, where they hoped to establish themselves.

And soon after registering at the hotel and sending for their luggage, the boys took a car for the fair grounds. They were filled with wonder when they reached them, even though the place was not yet open, nor finished. And as they saw so many objects of interest, and as their sensations were so varied, I think I can do no better than to begin a new chapter with them.

Probably many of you will go, or have already gone, to the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, which is the official name for what is commonly called the Panama Fair, and I shall often refer to it that way myself. Those of you who have seen the fair will, therefore, recognize much of what is described in this book.

"Say, this certainly is great!" cried Pep, with sparkling eyes, as he glanced about, once they were inside the exposition grounds. They had to obtain a pass, as the place was not yet open to the public, but as possible concessionnaires in the Zone they found no trouble in being admitted. "It's great—immense—stupendous—wonderful! It's—it's——"

"Hold on, Pep!" cried Frank. "Save a few of those big words."

"Yes," agreed Randy with a smile. "You haven't begun to see it yet, Pep."

"That's right!" chimed in Hank Strapp. "This is the biggest thing of its kind that ever happened. It's like the West—it's big—we have to have room to spread ourselves out here, boys. It sure is great!"

To hear him talk, and look at his honest, enthusiastic face, you would have thought that Strapp himself had had a great deal to do with the success of the venture. But that was only his way.

The boys, with Strapp and Ben, had gone in through the Fillmore Street entrance. Directly to their left began that part of the grounds given over to amusement enterprises, with the broad highway, called the Zone, which gave its name to the active division, running through it. The structure for the great scenic railway was the first object that met the eyes of the boys, but they were not greatly interested in that, having seen a number, though this was destined to excel most of them. But it was not yet finished.

On the left was Festival Hall, with its beautiful grounds, on which men were still working, and then before the boys and their friends stretched out the Avenue of Progress, with the Machinery Palace on the right, and the group of buildings about the Court of the Universe as a center, on their left. Those latter buildings would, later, house the exhibits of varied industries, mines and metallurgy, transportation, manufactures, liberal arts, agriculture, food products and education and economy.

"I wonder if they'll have any motion picture machines on exhibition?" spoke Randy, for he was much interested in the mechanical end of their business.

"Oh, there'll be sure to be plenty of those," Frank said. "Now what shall we do?"

"Look about a bit," proposed Pep. "This is the greatest place I ever struck!"

"But don't linger too long," advised Hank. "If we're going to get a concession we'd better look lively. A whole lot depends on getting a good place, especially for motion pictures. We don't want to get left."

"No, indeed," agreed Frank, "not after the way we hustled out here."

"But we can look about a little," suggested Ben Jolly. "I want to see if they have any small pipe organs we can arrange to install. A pipe organ is what we want to bring out the full effect of our pictures."

"A pipe organ it shall be!" promised Frank, laughing.