Lowry sculp.

Title: Voyage to the East Indies

Author: a S. Bartholomaeo Paulinus

Contributor: Johann Reinhold Forster

Translator: William Johnston

Release date: July 8, 2025 [eBook #76461]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Vernor and Hood, 1800

Credits: Carol Brown, Peter Becker and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Footnotes were renumbered sequentially and were moved to the end of the book. Obvious printing errors, such as backwards, upside down, or partially printed letters and punctuation, were corrected. Final stops missing at the end of sentences and abbreviations were added. Duplicate or missing letters at line endings were removed or added, as appropriate.

Words have inconsistent spelling, hyphenation, and use of diacriticals. These were not changed unless indicated below. Dialect, obsolete and alternative spellings were not changed. Long dashes were converted to elipses in Book 2, chapter 7.

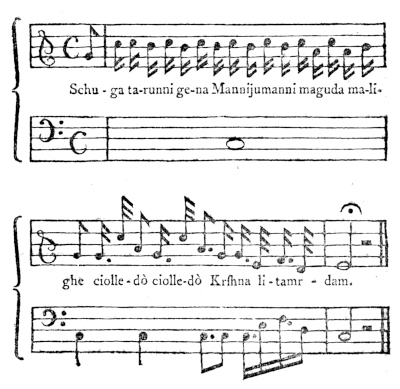

A link to the audio file was added for music. The music file is the music transcriber's interpretation of the printed notation and is placed in the public domain. At the time of this writing, music file links will not work in mobile e-book formats like epub or Kindle/mobi. Users who are reading the e-book in one of these formats can listen to the music or download the music file in the HTML version. Lyrics to the musical score are presented as poetry following the illustration of the music.

The following were changed:

[Pg iii]

CONTAINING

An Account of the Manners, Customs, &c. of the Natives, With a Geographical Description of the Country.

COLLECTED FROM

Observations made during a Residence of Thirteen Years, between 1776 and 1789, in Districts little frequented by the Europeans.

BY

FRA PAOLINO DA SAN BARTOLOMEO,

Member of the Academy of Velitri, and formerly

Professor of the Oriental Languages in the Propaganda at Rome.

WITH NOTES AND ILLUSTRATIONS BY

JOHN REINHOLD FORSTER, LL.D.

Professor of Natural History in the University of Halle.

TRANSLATED FROM THE GERMAN

BY WILLIAM JOHNSTON.

LONDON.

PRINTED BY J. DAVIS, CHANCERY LANE:

AND SOLD BY VERNOR AND HOOD, POULTRY; AND

J. CUTHELL, HOLBORN.

M.DCCC.

[Pg iv]

[Pg v]

The original of this work appeared at Rome in the year 1796[1]. A German edition was published, in 1798, at Berlin, by the well-known Dr. John Reinhold Forster, with copious Notes; and from the latter the English Edition now offered to the Public has been translated. The Notes, a very few excepted, the Translator has retained, and it is hoped they will be found useful to illustrate various parts of the Text.

The author, Fra Paolino da San Bartolomeo, a barefooted Carmelite, resided thirteen years in India, and therefore may be supposed to [Pg vi] have been well acquainted with the subject on which he treats. He was born at Hof, in the Austrian dominions, in 1748; and, before he embraced the monastic life, was known by the name of John Philip Wesdin. He was seven years Professor of the Oriental Languages in the Propaganda at Rome, and since his return from India has published several works relating to that country.

In regard to the present work, Dr. Forster, in his Preface to the German Edition, says:

“It is the more valuable, as the author understood the Tamulic or common Malabar language; and, what is of more importance, was so well acquainted with the Samscred, (a language exceedingly difficult,) as to be able to write a Grammar of it, which was published at Rome in 1790[2]. It appears from some of his quotations, that he understood also the English and French.

[Pg vii] “His knowledge of the Indian languages has enabled him to rectify our orthography, in regard to the names of countries, cities, mountains, and rivers. The first European travellers who visited India were, for the most part, merchants, soldiers, or sailors; very few of whom were men of learning, or had enjoyed the advantage of a liberal education. These people wrote down the names of places merely as they struck their ear, and for that reason different names have been given to the same place in books of travels, maps, and military journals. To this may be added, that the authors were sometimes Dutch, sometimes French, and sometimes English; consequently each followed a different orthography, which has rendered the confusion still greater. The author of the present work thought it of importance to correct these errors; a task for which he seems to have been well qualified by his knowledge of the Indian dialects. Thus, for example, he changes the common, but improper, appellation Coromandel into Ciòlamandala, Pondichery into Puduceri, &c.; but the Reader ought to remember, that, as the author wrote in Italian, his c before e and i must be pronounced tch, &c.

[Pg viii] “As the changed orthography of the names of countries, cities, and rivers, rendered a Geographical Index in some measure necessary, one has been added at the end of the work.—Readers acquainted with the tedious labour required to form such a nomenclature, and who may have occasion to use it, will, no doubt, thank the Translator for his trouble.”

| BOOK I. | |

| Chap. I. | |

| Arrival at Puduceri (Pondichery)—Coast of Coromandel—Going on shore—Capuchins—Jesuits—Description of the City—Its Trade—Fortifications—White Ants—Bitter Drops—Error of the Heathens in regard to Christianity | Page 1 |

| Chap. II. | |

| Virapatnam—Seminary there—Error of Ptolemy the Geographer—Apis—Error of some modern Geographers—Etymological Catalogue of Places in Carnada, Tanjaur, and Madura | 18 |

| Chap. III. | |

| Geographical, statistical, and historical Observations on the Kingdoms of Tanjaur, Marava, Madura, and Carnada | 35 |

| Chap. IV. [Pg x] | |

| Journey from Puduceri to Covalan, Maïlapuri, and Madraspatnam | 67 |

| Chap. V. | |

| Indian Weights, Measures, Coins, and Merchandise | 78 |

| Chap. VI. | |

| Topographical Description of Malabar | 102 |

| Chap. VII. | |

| Population of Malayala—Manners, Customs, and Industry of the Inhabitants—Political State of the Country | 149 |

| Chap. VIII. | |

| Missionary Affairs—Audience of the King of Travancor | 177 |

| Chap. IX. | |

| Quadrupeds, Birds, and Amphibious Animals on the Coast of Malabar | 210 |

| Chap. X. | |

| Seas, Rivers, Vessels used for Navigation, Fish, Shell-fish, and Serpents in India | 229 |

BOOK II. [Pg xi] | |

| Chap. I. | |

| Birth and Education of Children | 253 |

| Chap. II. | |

| State of Marriage among the Indians | 269 |

| Chap. III. | |

| Laws of the Indians | 284 |

| Chap. IV. | |

| Classes or Families of the Indians | 293 |

| Chap. V. | |

| Administration of Justice among the Indians | 309 |

| Chap. VI. | |

| Languages of the Indians | 313 |

| Chap. VII. | |

| Religion and Deities of the Indians | 324 |

| Chap. VIII. | |

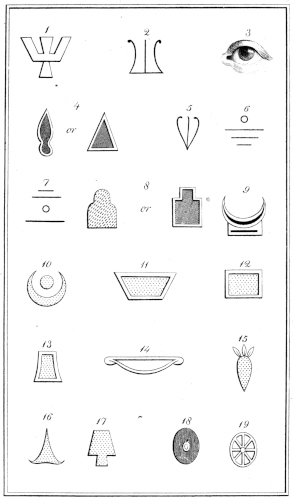

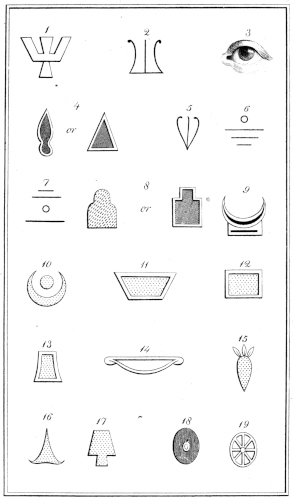

| Hieroglyphical Marks of Distinction among the Indians | 340 |

| Chap. IX. [Pg xii] | |

| Division of Time—Festivals—Calendar of the Indians | 345 |

| Chap. X. | |

| Music, Poetry, Architecture, and other Arts and Sciences of the Indians | 364 |

| Chap. XI. | |

| Medicine and Botany of the Indians | 401 |

| Chap. XII. | |

| Author’s Voyage to Europe—Some Account of the Island of Ceylon | 424 |

| Chap. XIII. | |

| The Author’s Voyage to Europe continued—Short Account of the Isles of France and Bourbon, the Cape of Good Hope, and the Island of Ascension. | 437 |

| Page 28, last line, for Krishavaram, read Krishnavaram. |

| 56, sixth line from the top, for Condur, read Coudur. |

| 64, third line from the bottom, for Tindacalla, read Tindacolla. |

| 125, first line, for Clagnil, read Elagnil. |

[Pg 1]

Arrival at Puduceri (Pondichery)—Coast of Coromandel—Going on shore—Capuchins—Jesuits—Description of the City—Its trade—Fortifications—White ants—Bitter drops—Error of the heathens in regard to Christianity.

THE ship l’Aimable Nannette, commanded by Captain Berteaud, in which I sailed from l’Orient, arrived in the road of Puduceri[3] on the 25th of July 1776, after a tedious passage of six months and as many days. Our patience was, therefore, almost exhausted; and we longed not a little to set our feet once more upon dry ground. We directed our anxious looks towards the shore over the blue waves, and flattered ourselves with the [Pg 2] hopes of reaching it that evening[4]: but, as the duration of the twilight is exceedingly short in India, night suddenly overtook us, disappointed the accomplishment of our wishes, and spread her dusky veil over both sea and land. At sun-rise next morning we saluted the citadel of Puduceri with eleven guns; a compliment which the garrison returned with nine, and at the same time hoisted the French flag.

The coast of Ciòmandala[5], which the Europeans very improperly call Coromandel, has at a distance the appearance of a green theatre. The sea-shore is covered with white sand; and a multitude of beautiful shells are here and there to be seen. The country is intersected by a great many rivers and streams, which flowing down from the high ridge of mountains on the west, called the Gauts, pursue their course towards the east, and discharge themselves into the sea; some with impetuosity and noise, others with gentleness and silence. In the months of October and November, when the rainy season commences, these streams are swelled up in an extraordinary degree, and sweep from the mountains a multitude of serpents, [Pg 3] which, to the no small terror of the unexperienced traveller, they carry a great way out with them into the sea. This, in all probability, has given rise to the fabulous tales of sea monsters, which some pretend to have seen in the Indian ocean. The land here is covered, to a considerable distance, with trees of all kinds, and particularly that called by the Europeans the real Indian palm or the coco-nut tree. The Indians give it the name of tenga, and make much use of it for planting neat gardens, with which not only the coast of Malabar, but a great part of that of Ciòlamandala also is, in a manner, overspread. Various hamlets and villages are interspersed between these gardens, and the whole surrounding country delights the eye with never-fading verdure.

During my travels through India I found the climate every where mild and healthful; and in no place did I hear complaints of bad weather. The Indians generally sleep with their doors and windows open, except when there is any appearance of the Caracatta, which is a certain kind of wind that blows from the quarter of the Gauts. This chain of mountains begins at Cape Comari[6], in the eighth, degree of north latitude, and extends thence towards the north; so that it almost intersects India in the middle. The eastern part is called Ciòlamandala, that is, the land of millet[7]; the western Malayala, or the land of mountains. The latter is called by the Arabians and Europeans Malabar, or the Malabar coast. The Gauts, the highest ridge of mountains [Pg 4] in this country, occasion that difference in the weather, and that remarkable change of seasons which take place on both these coasts. This is one of the most singular phenomena of nature ever yet observed. On the coast of Ciòlamandala the summer begins in June; but on the coast of Malabar it does not commence till October. During the latter month it is winter on the coast of Ciòlamandala, whereas on the coast of Malabar it begins so early as the 15th of June. The one season therefore always commences on the east coast at the time when it ends on the western. When winter prevails on the coast of Malabar; when the mountains and valleys are shaken by tremendous claps of thunder, and awful lightning traverses the heavens in every direction, the sky is pure and serene on the coast of Ciòlamandala: ships pursue their peaceful course; the inhabitants get in their rice harvest, and carry on trade with the various foreigners who in abundance frequent their shores. But when the wet season commences; when these districts are exposed, for three whole months, to storms and continual rains, hurricanes and inundations, the coast of Malabar opens its ports to the navigator; secures to its inhabitants the advantages of trade, labour and enjoyment; and from the end of October to the end of June presents a favourable sky, the serene aspect of which is never deformed by a single cloud. This regulation of nature appeared to Strabo, the geographer, altogether incredible; and he, therefore, abused those travellers who, on their return from India, asserted that in the course of the year, in that country, there were two summers and two winters. In this manner must the writers of travels often suffer [Pg 5] by the ignorance of their readers[8]. “When I called in the aid of commentators to illustrate such passages,” says Chardin, “I every where observed the most palpable errors; for these people grope in the dark, and endeavour to explain every thing by conjecture.”

On the 26th of June I left the ship about noon, and, in company with M. Berteaud the captain, went on board a small Indian vessel of that kind called by the inhabitants shilinga. As it is exceedingly dangerous and difficult to land at Puduceri and Madraspatnam, these shilingas are built with a high deck, to prevent the waves of the sea from entering them. This mode of construction is, however, attended with one inconvenience, which is, that the waves beat with more impetuosity against the sides; raise the shilinga sometimes towards the heavens; again precipitate it into a yawning gulph, and, at length, drive it on shore with the utmost violence[9]. In such cases the vessel would be entirely dashed to pieces, if the Mucoas, or fishermen, who direct it, did not throw themselves into the sea, force it back by exerting their whole strength, and in this manner lessen the impetuosity of the surf. I was greatly alarmed before I reached the shore; and [Pg 6] was so completely drenched by the waves, that the water ran down my back.

When I approached the city, I was exactly in the same state as if I had entered a furnace; for the sun had rendered the sand, with which the shore is covered, almost red hot. The reflection of his rays caused an insufferable smarting in my eyes, and my feet seemed as if on fire. I was met on the road by some Indian Christians, who conducted me to the convent of the Capuchins, in the southern extremity of the city. These good fathers were then employed in building: for the English, in the year 1764, had bombarded Puduceri from their ships lying in the road; and the poor Capuchins, as well as others, felt the effects of their vengeance, their church and convent being converted into a heap of ruins. The English, perhaps, were not acquainted with the maxims of the Pagan Indians, who consider it as an unpardonable crime to destroy the temple and house of God; for they say, Covil kettium tannir pandel kettium nashikarudàae; which may be thus translated: “It is never lawful to destroy a temple, and the halls in which travellers have lodged.” For want of room the Capuchins were not able to admit me into their convent, and therefore I repaired to the French missionaries, belonging to the so called Missions étrangères, who resided in the pagan quarter of the city. Here I found the procurators of this establishment, Messrs. Jallabert and Mouthon, by whom I was received with every mark of kindness and attention. After dinner I took a walk to the Jesuits’ college, where I saw Father Julius Cæsar Polenza, a learned Neapolitan, who was celebrated on account of his political talents, but still more on account of his knowledge of the Tamulic language; also Father le Fabre, Father Anzaldi; and fifteen other missionaries who had not [Pg 7] long before assembled there, for the first time, from Tanjaur and Madura.

The governor of Puduceri, at that time, was M. Law de Lauriston, a man of very moderate principles, who perfectly understood the art of living in a state of peace and friendship, both with the English at Madraspatnam, and the Pagan Indians his neighbours. Few of those who preceded him in the government of Puduceri possessed the same virtue. On the contrary, most of them made it their chief study to endeavour to extend their dominion. This man’s prudence and moderation were not, therefore, approved by some of his hot-headed countrymen; and Sonnerat[10] inveighs bitterly against the friendly reception which Lord Pigot the governor of Madraspatnam experienced when he passed through Puduceri. Cum vitia prosunt, peccat qui recte agit—When vice thrives, those who act right become criminal.—The moderation of M. Law de Lauriston could not then fail to give offence to illiberal minds, subject to the impulse of their passions.

Puduceri, in my time, was a large and very beautiful city. The governor resided in an elegant palace. It was not uncommon to see a hundred covers on this gentleman’s table; and I once had the honour, together with M. Jallabert, of being invited to one of his entertainments. The city, towards the north and south, is defended by excellent fortifications, constructed in the year 1769, under the direction of M. Bourcet, who also formed the plan of them. In the southern part, some of the [Pg 8] houses, inhabited by the Europeans, are exceedingly large and beautiful, and are ornamented with projecting galleries, balustrades, columns and porticoes. The European quarter is entirely separated from that of the Mahomedans and Pagan Indians. The latter live altogether in the western part. When a certain quarter is in this manner assigned to the Indians for their residence, one of their countrymen is always placed over them as a superintendant, who is obliged to preserve peace and good order among them, and to take care that they do not transgress the laws. At Cottate, Padmanaburam, Tiruvandapuram, Cayancollam, and other towns on the Malabar coast, the same establishment is made, that no strife or contention may arise among the various tribes, castes, and religious sects, on account of the difference of their manners and customs. Every one here is allowed to live in his own manner, and to enjoy his own belief; as it is not possible that so many classes and so many thousands of people should ever unite in one common system of religion[11].

The gate of the city towards the west was guarded by the so called sipoys (seapoys) or Indian soldiers, who consist of people of every caste, and of all religions. They were exercised according to the French manner. Hayder Aly Khan, that celebrated and formidable warrior, who reduced under his dominion Maissur, Carnate, Concao, Canara and Calicut, was originally a seapoy who did duty at this gate of Puduceri[12]. In that city he became first acquainted [Pg 9] with the French tactics, which he afterwards employed not only against the Indian kings and princes, but against the Europeans; and it is not improbable that another Indian hero may arise in the course of time, and, in like manner, make use of the military discipline of the English, which that nation still teach to the native Indians. As the English and French in India are in a continual state of enmity, some enterprising Indian generally steps in between them, and attacks either the one or the other of the contending parties. Such was the conduct of Hayder Aly Khan’s son, Tippoo Sultan Bahader, who overran a considerable district in the southern part of India, and defeated the British troops in several engagements.

Puduceri was given up to the French, on the 15th of July 1630, by Rama Rajah a son of Sevagi king of the Marattas. This prince was sovereign of the province of Gingi, and possessed a fortress of the same name, which was situated among the mountains on the south of Puduceri. Rama Rajah had wrested this province, to which Puduceri belonged, from its original and lawful owner; and he resigned the city to the French on condition of their paying two per cent. on all the goods which should be there exported or imported. When Captain Ricaut established the French East India Company in 1642, he entered into partnership with twenty-four other merchants; and the only object of this society, as they then pretended, was to carry on trade in India. These merchants, however, shewed only too soon that their views were directed to things totally different. By little and little they began to extend their boundaries; endeavoured to get into their hands new possessions; from being merchants became warriors, and at last ventured to refuse the two per cent. which they had solemnly contracted to pay. This was done, in particular, after the year 1695, [Pg 10] in which the Moguls took the fortress of Gingi[13]. There is just reason then to be surprised at the singular conduct of the Abbè Raynal, who throws out the bitterest reproaches against the Portuguese, as the first conquerors of India; and yet passes over, in perfect silence, what might be said of the violent proceedings of the other European nations, who certainly trod in the footsteps of the Portuguese. M. Dupleix, who was then governor of Puduceri, caused the Mogul to create him a nabob, that is an Indian chief or prince; and after that period the before-mentioned engagement and duty were, in the course of a few years, buried in oblivion. The haughtiness of the French still increased; the utmost degree of jealousy prevailed between them and the English; and a war was the consequence, in which the French soon lost their trade and their Indian possessions, which they afterwards recovered, and lost and recovered in turns. The Dutch East India Company, more attentive to its interest, and less inclined to war, possessed also several considerable settlements in India; but it excited much less jealousy, because it observed a peaceable conduct, and by these means acquired greater riches. In the year 1693, the Dutch took Puduceri, but restored it at the peace of Ryswick. In the year 1748 it was besieged by the English; and in 1761 it was taken by them, but given up at the peace of 1763. They made themselves masters of it a second time in 1778, when De Bellecombe was governor, but abandoned it afterwards in 1783. On the commencement of the French revolution it came under the dominion of the nabob Mohamed Aly prince of Arcate, a faithful adherent of the English; and ever since it has [Pg 11] remained in his hands, or rather in the hands of the English. To such a state have the affairs of the French in India been reduced by their pride, their ambition and their rage for war! What benefits or advantages could France expect, as an indemnification for the monstrous sums which it was obliged to expend on this Indian colony, during its varied and ever changing fate? When in its most flourishing condition, it was said to contain, including the district belonging to it, about 20,000 inhabitants. Of these from four to five thousand, at least, were employed in collecting cotton; and in carding, spinning, weaving and printing it. By means of this industry the trade might have been so far improved that it would not only have sufficiently indemnified the Company for their expence, but have procured them the greatest advantages. On my arrival at Puduceri, five French ships were lying in the road, and the Aimable Nannette made the sixth. Some days after four others came to anchor. Three of these vessels were more than sufficient to supply the colony with every necessary; for three or four French merchants only resided in it. These ships were laden with wine, iron, cannon, fire-arms and French cloth. Now the Indians drink no wine, and their clothing consists of white cotton stuffs manufactured in their own country. How then did the French dispose of their commodities? They sold their wine, cloth, cannon, fire-arms, and, in a word, their whole cargoes to the English at Madraspatnam and Bengal, who employed these very cannon and arms against the French troops. On the other hand, the greater part of the money which the French received for these goods remained in India, as they purchased with it muslin, cotton stuffs, ginghams, sugar, pepper, cinnamon, cardamums, handkerchiefs, pearls, precious stones, and male and female [Pg 12] slaves. Whether such a trade could be beneficial to France, I shall leave the reader to determine[14].

The garrison of Puduceri consisted of 4000 men. The city is situated on a sandy plain, not far from the shore, which produces nothing but palm trees, millet, and a few herbs; though the surrounding district produces cotton, with a little rice and capers. Neither Puduceri nor Madras atnam can be compared with the cities on the Malabar coast, in regard to abundance in provisions. On the coast of Ciòlamandala, which forms the eastern part of this peninsula, the heat is more intense, and the soil much sandier than any where else; and fewer rivers are found here, because it is too far distant from that ridge of mountains called the Gauts. To these circumstances it is to be ascribed that it produces very little cotton, and much less rice; that a greater trade is carried on here, while agriculture is neglected; and, in short, that its inhabitants are much more active and ingenious, handsomer, blacker, and more superstitious than on the coast of Malabar. The kingdom of Tanjaur forms, however, an exception; for this district is watered by several rivers that flow through it, and supplies with rice the whole coast of Ciòlamandala. The English, therefore, never ceased quarrelling with the Indian princes till they had reduced this kingdom under their subjection, as I shall soon relate in a more particular manner.

I remained at Puduceri till the 8th of September. During that time, which I employed in making myself acquainted with the geography of the country, the manufactures and manners of the Indians, I [Pg 13] met with two incidents, which to me were new, and on that account excited more my astonishment. I had put all my effects into a chest which stood in my apartment, and being one day desirous of taking out a book in order to amuse myself with reading, as soon as I opened the chest I discovered in it an innumerable multitude of those white insects which the Tamulians, that is the inhabitants of the coast of Ciòlamandala, call Carea, and those of Malabar Cedel. They are the white ants which have been already described by naturalists, but which I never before had an opportunity of seeing[15]. When I examined the different articles in the chest, I unfortunately observed that these little animals had perforated my shirts in a thousand places; gnawed to pieces my books, and among others had already half destroyed a copy of Father Gazzaniga’s Theology; my girdle, my amice, and my shoes fell to pieces as soon as I touched them. The ants were moving in columns each behind the other, and each carried away in its mouth a fragment of my effects, As I expressed my astonishment by a loud shout, M. Jallabert ran into the room, and, seeing the swarms of these insects, repeatedly exclaimed, Carea! Carea! He then ordered my chest to be placed in the sun, and as soon as these careas found themselves exposed to his rays, they all speedily left it. My effects, however, were more than half destroyed; but it was very fortunate for me, on this occasion, that cotton goods are sold exceedingly cheap at Puduceri. One of the finest shirts, ready made, costs [Pg 14] no more than five Roman paoli, or a rupee[16], according to the course of exchange in that settlement. I therefore clothed myself anew from head to foot, and with articles made of cotton.

One evening, a few days after, I had entered into a conversation with M. Jallabert on the religious ceremonies of the Heathens, and the properest means of converting them to the Christian faith; while his two servants had thrown themselves down on mats, spread out in the fore hall, in order to sleep. All of a sudden one of them began to scream out dreadfully; to beat his forehead; to stamp on the floor, and to roar and writhe his body like a madman. On asking him what was the matter, he pointed to one of his ears. We found on examination that a centipede had got into it; and the animal not being able to find its way out, kept pushing itself forwards, and gnawed the interior part of the ear. M. Jallabert immediately made the poor fellow lie down, and poured into his ear a spoonful of bitter drops (droga amara). The insect was dead in a moment; the patient’s pain and terror ceased, and, as soon as a little water was poured into his other ear, the centipede dropped out. These bitter drops are prepared in the following manner. You take mastic, resin or colophonium, myrrh, aloes, male incense, and calamba root, and pound them very fine when the weather is dry, that is to say when the north wind blows, which, in other parts of the world, supplies the place of what is here called the Caracatta. If you wish, therefore, to make a quantity of this medicine equal to 24 pints, you must take 24 ounces of resin or colophonium, 12 ounces of incense, 4 ounces of mastic, 4 ounces of aloes, 4 ounces of myrrh, and a like quantity of calamba root. Put [Pg 15] all these ingredients into a jar filled with strong brandy, and keep it for a month in the sun during dry weather. If the brandy is sufficiently impregnated, it assumes a red colour, and the mass is deposited at the bottom. You then draw off the brandy very slowly, and bottle it up for use. One or two spoonfuls is the usual dose administered to sick persons. This medicine is of excellent service in cases of indigestion, colic, cramp in the stomach, and of difficult parturition; also for wounds and ulcers; against worms, and in scorbutic and other diseases which arise from corrupted juices. It is the best and most effectual remedy used by the missionaries during their travels. It is prepared in the apothecary’s shop of the ex-jesuits at Puduceri; at Verapoli by the barefooted Carmelites; and at Surat by the Capuchins. I myself cured with these drops a young man who was almost totally deaf. After pouring two spoonfuls of them into his ear, a cylindric piece of a hard yellow substance came from it, and the patient immediately recovered the perfect use of his hearing.

As I resided in the Pagan quarter of the city, I was visited by several young Indians; some of whom were heathens, and others professors of Christianity. Some of them spoke exceedingly good French; but others, who had received instruction from the Jesuits, spoke Latin. From this I concluded that the Indians are by nature well qualified for study; and that the Indian dialect facilitates, in an eminent degree, their acquiring the European languages. Those who were still heathens, boasted much of their theology; and extolled above all measure their learned language, which they call the Samscred. This confirmed me so much the more in the resolution I had formed of learning it, let it cost me whatever labour it might. I observed, however, at the same time, that these young people, either from ignorance or [Pg 16] perversity, frequently confounded the doctrine and principles of Christianity with the doctrine and principles of Paganism. Thus, for example, they said that their female divinity Lakshmi was our Virgin Mary, and that Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva, represented our Trinity; that we paid to images as much adoration as they did; and that our solemn processions were in nothing different from theirs[17]. I shall hereafter convince the reader of the falsity of this assertion, and shew how highly important it is that the missionaries should make themselves well acquainted with the religious doctrines of the Indians, in order to open the eyes of these people, so worthy of pity, and to convert them to the Christian faith[18]. They deceive not only themselves, but others; for, as they endeavour to lay to the charge of the Christian religion [Pg 17] their own absurd tenets, they do not think it necessary to embrace it; and as they assert that there is no difference between their belief and ours, they mislead other Christians, who then imagine that the religion of the Pagan Indians is nothing else than Manicheism, or corrupted Christianity; and this error arises, like the former, from perverted principles and fables.

As the Pagans, Mahometans, and Christians in India all wear white cotton dresses, and made almost in the same manner, you must look very closely at their forehead, or breast, if you wish to distinguish an Idolater from a Christian. The former have on the forehead certain marks which they consider as sacred, and by which you may know to what sect they belong, and what deity they worship. In the second book I shall explain all these marks[19].

Virapatnam—Seminary there—Error of Ptolemy the geographer—Apis—Error of some modern geographers—Etymological catalogue of places in Carnada, Tanjaur and Madura.

M. Jallabert had given-me a particular account of a seminary at Virapatnam, in which young Indians who embraced the Christian religion were educated. As education is an object which deserves the particular attention of the traveller, we made a little excursion thither from Puduceri. Vira, in the Samscred language, signifies strong or courageous; and Patna, or Patana, a city. Virapatnam, therefore, signifies the strong city. This place, at present, is a small town situated at the distance of six miles from Puduceri, towards the south west, on the banks of a river, which takes its rise in the mountains on the east, and, flowing part Virapatnam, discharges itself into the sea on the south side of Puduceri. Pudu in the Tamulic and Malabar languages, signifies new; Puduna, newness; Ceri, a town: Puduceri therefore signifies the new town. From this etymology it is clear that Puduceri cannot be a place of any antiquity; and it was indeed built by some emigrants from Virapatnam. When the Arabians first came to India, several cities lying on the sea coast arose in the like manner. It is therefore ridiculous when certain geographers, who endeavour to explain Ptolemy’s geography, consider cities first built in modern times to be the same as some of those mentioned in that author, though they must undoubtedly have [Pg 19] been unknown to him, as they were not then in existence. It deserves also to be remarked, that Ptolemy, in giving the distances of places, generally errs from two to three degrees of latitude. The reason is, that the ancient travellers were accustomed to reckon the latitude according to the length or shortness of the day; and, consequently, to determine the distance of one place from another in the same manner. But as the day and night near the equator are almost always of equal length, it may readily be conceived, that the degree of latitude in which a place was situated could not be accurately ascertained in that manner; and that Ptolemy, and all those who depended upon him, must have fallen into errors[20]. The case has been nearly the same with M. D’Anville, as will be shewn hereafter.

The seminary of Virapatnam was situated in a palm-garden; or, to speak more correctly, in a garden planted with coco-nut trees. It was founded by M. Mathon, a celebrated member of the so called Missions étrangères, who, at the time we were there, presided over it as rector. The building resembled a convent, but was much better divided; and so contrived, that these oriental seminarists did not find the least impediment, either in their study, their bodily exercise, or their other labours. Between three side apartments, where the three tutors lodged, was a large hall on the ground floor, in which were constructed two rows of small chambers all adjoining. They were separated from each other by [Pg 20] thin wooden partitions, of only three or four palms in height; so that each of the students had an apartment to himself, and all of them could be observed by their teacher. The teacher sat at a desk, where he read his lessons; and, while employed in teaching, he could with one view see every thing that was doing in the different apartments. The pupils not only studied in these apartments, but also slept in them. A table, on which lay a mattress, supplied the place of a bed; and both above and beneath it another small table was suspended, which could be lowered or raised up at pleasure. If any of these young people wished to write, he had no occasion to leave his chamber, as he had nothing to do but to sit down at the foot of his bed; and when he wished to go out, he had only to remove his table and fold it up. On the other table above the bed were books, paper, pens and ink; his long seminary dress, and several small articles necessary for preserving cleanliness. The doors of the hall, which were exactly opposite to each other, stood always open to afford a free passage to fresh air; but no one could go out unperceived by the tutor, who in his apartment was continually observing every thing that passed. The refectory was situated in another part of the building; and it was customary to read in it during meals. The shops of the taylor, shoemaker, and carpenter, together with the printing-office and ovens for baking bread, were without, and all occupied by seminarists; for each of them was obliged to learn a trade. They all went bare-footed; and one of their employments was to water and look after the young palm-trees which were planted in the garden. Their time was so divided, that they studied daily four hours; devoted one hour to manual labour; and spent the remaining part in prayer, singing and meditation. On two days in the week they conversed in their mother tongue; but on other days they [Pg 21] were obliged always to speak Latin. M. Mathon shewed me a bull of his present holiness Pope Pius VI. issued in favour of this seminary, and in which he bestowed great praises upon it. This institution was destined merely for young persons from China, Cochinchina, Tunquin, and Siam. It is much to be lamented that no establishment of the like kind is to be found here, for the natives of Malabar, and other parts of the peninsula of India, who are all formed to the ecclesiastical state in other countries, and return, for the most part, men of corrupted morals.

On the day of my return to Puduceri, I had an opportunity of seeing a very singular scene; as on that day the god Apis was led in procession through the city. This deity was a beautiful fat red-coloured ox, of a middle size. The Brahmans generally guard him the whole year through in the neighbourhood of his temple; but this was exactly the period at which he is exhibited to the people with a great many solemnities. He was preceded by a band of Indian musicians; that is to say, two drummers, a fifer, and several persons who with pieces of iron beat upon copper basons. Then came a few Brahmans, and behind these was an immense multitude of people. The Pagans had all opened the doors of their houses and shops, and before each stood a small basket with rice, thin cakes, herbs, and other articles in which the proprietors of these houses and shops used to deal. Every one beheld Apis with reverence; and those were considered fortunate of whose provisions he was pleased to taste a mouthful as he passed. Philarchus conjectured, as we are told by Plutarch in his treatise on Isis and Osiris, that Apis was originally brought from India to Egypt by the inhabitants of the latter. Plutarch himself asserts that the Egyptians considered Apis as an emblem of the soul of Osiris; and, perhaps, he here meant to [Pg 22] say, that under this expression they understood that plastic power by which Osiris had produced and given life to every part of the creation. I shall, in another place, endeavour to prove, that Osiris was nothing else than the Sun, and consequently what among the Indians is represented by the idol Shiva, or Mahadèva. Hence it happens, that this Shiva, the emblem of the Sun, rides on an ox; and that in the solemn invocations of the Brahmans he is called Pashupadi, that is, the man of the cow. The cow again is nothing else than a symbol of the goddess Ishami, or the woman, as the Indians are accustomed to call the Isis to whom the cow is dedicated when they speak of her by her sacred name. On the Egyptian monuments Osiris, as the symbol of the Sun, is represented with rays around his head; and his wife Isis bears horns, the symbol of the cow, and also of the new moon, between which and the sun there is the same relation as between wife and husband. On the Indian monuments the idol Shiva has an ox under him; and the goddess Ishami, as she is represented in one of the oldest Indian temples, is leaning with one of her arms on a cow[21]. Pliny in his Natural History, speaking of Apis, makes use of the following remarkable words: “When he eats out of the hand of those who come to consult him, it is considered as an answer. He refused to have any thing from the hand of Germanicus Cæsar, and the latter soon after died[22].” From this it appears that the Egyptians entertained the same opinions respecting Apis as the Indians. In Egypt, as [Pg 23] well as India, people were accustomed to consider him as an oracle; to place food before him, and, according as he accepted or refused it, to form conclusions in regard to their good or bad fortune. Does not this evidently shew an analogy in the religious veneration which both these nations shewed to Apis? As the ox, or Apis, represents the plastic power of the sun, the cow, in the like manner, is a symbol of the plastic power of the moon and the earth. The ox, or Apis, is called in the Samscred Uksha, Bhadra, Urszabha, Gau, and Mahisha; but, in the Malabar and Tamulic languages, Kàla, Muri, and Cruda. The cow in the Samscred is called Mahey, Saurabhei, Gò, Usra, Mahà, Shranguini; when she is red, Argiuni; when she is white, Rohinni: in the Malabar and Tamulic languages she is called Pashu, Gova. All these appellations express some of the properties of oxen and cows. Thus, for example, Bhadra means good; Mahisha, great, magnanimous; Mahà, a large cow, a noble animal; Shranguini, handsome, ornamented, beautiful. The idolaters of Malabar call her Ama or Tala, mother; and the ox Appen, father. May not the name Apis employed by the Egyptians and the Greeks be the corrupted Appen, or Appa of the Indians, which signifies father or creator? The Egyptians were accustomed to give to their Isis the horns of a cow, instead of a head dress. The Indians also worship the cow as a divinity. Most of the houses belonging to the Pagan Indians, not only at Puduceri, but upon the whole of both the coasts of Malabar and Ciòlamandala, are covered on the outside and inside with cow-dung. The Pagans are accustomed to drink cow’s urine, in order to purify them from their sins. When near the point of death, they take in their hand a cow’s tail; and, according to their belief, if they die in this manner, they are immediately [Pg 24] transported to paradise. I have already said, that the cow is a symbol of the moon and the earth. For this reason she is also in India the goddess Parvadi or Isháni, Ishi or Isha; that is, the woman, the hallowed; under which appellation they understood the moon. She is also the goddess Ma or Lakshmi, that is the great, dedicated to the beautiful goddess; and all these sacred names properly signify the earth. The cow has evidently a mystic sense also, which denotes the plastic power of the moon, and the fertility of the earth. For this reason she is held so sacred, and honoured so much, that in Malabar, and every other place where the Pagans have the superiority, any person who kills a cow is hung on a gibbet. The ox which represents Apis, must every three years give place to another. If he dies in the course of these three years of his deification, he is committed to the earth with all that pomp and ceremony observed at the interment of persons of the first rank. Various pagodas, or pagan temples, have on their front the figure of a cow, or perhaps two, of a colossal size[23].

The habitations of the Pagans at Puduceri, as well as on the coasts of Malabar and Ciòlamandala, are in [Pg 25] general very low and dark. In the last-mentioned district they are built of bricks dried in the sun, and are covered with palm leaves. The Pondiyalas, or warehouses, in which the Indians keep their merchandise, are also very dark, especially at Puduceri and Madraspatnam. As a great deal of muslin is sold at both these places, it is not improbable that the merchants employ such a mode of construction, that the faults of their wares may be better concealed.

The Capuchins of the province of Tours in France have the right of sending a missionary priest to Puduceri when the place becomes vacant. The Ex-Jesuits, in virtue of a decree issued by Louis XVI, have united with the society of the Missiòns étrangères, so that they now form only one body. The Europeans are under the care of the Capuchins, and the Indian Christians under that of the Ex-Jesuits. The latter have to attend four thousand Christians: but this number is sometimes greater, sometimes smaller, according as it is peace or war; for, in the time of war, many Indian Christians remove from the place, and either wander about or take refuge in the mountains. Not long before my time, the seminary of Virapatnam had been, transferred to Ariancopan, which is the residence of a bishop, who at Puduceri, in the kingdoms of Tanjaur, Madura, and Carnada, as also in the province of Gingi, is invested with the dignity of apostolical vicar. This man is involved in continual quarrels with the bishop of Mailapuri, or St. Thomas, a Portuguese, who endeavours to dispute with him the right of spiritual judicature.

According to M. de la Tour’s map, which is the correctest, Puduceri lies in 12° N. lat. and 78° E. lon. On the 1st of January the sun rises here at 23 minutes past six, and sets at 37 minutes [Pg 26] past five. On the 28th of August he appears above the horizon at 51 minutes after five, and sinks below it at 9 minutes after six. On the first of December he makes his appearance at 21 minutes past six in the morning, and sets at 38 minutes past five in the evening. From these data the reader may easily calculate the length of the days and the nights.

The river which runs past Virapatnam, and discharges itself into the sea on the west of Puduceri, is called properly Ciovanàru, and not Chonenbar, as it is named by the European geographers. Aru, in the Malabar and Tamulic languages, signifies a river, and Ciovano red: the compound word is Ciovanàru, the red river: and its water, on account of the earth which it washes down in its course, is sometimes indeed of a blood-red colour. But as the Indians shorten the first half of the word, and say Ciona, or Tchona, instead of Ciovana, the Europeans have mutilated it completely, and made of it Chonenbar. A similar mutilation of Indian words and appellations is in general not uncommon, especially when they are introduced into foreign languages. On the map of Coromandel, published by M. De la Tour at Paris, in the year 1770, the above river is distinguished by the improper name of Chonenbar. That the case is the same with the word Coromandel, used instead of Ciòlamandala, has been observed before. M. D’Anville, with equal impropriety, not only in his Geographical Antiquities of India, printed at the king’s printing-house at Paris, in the year 1775, but also in all his maps of India, gives the name of Carnata to a large kingdom lying to the west of Puduceri. Its proper name is Carnàda; that is, the black land; from Car, black, and Nada, land. It is so called in the Tamulic and Malabar languages, in order to distinguish it from Ciòlamandala, the land of millet; for the millet thrives best on the districts [Pg 27] not far from the sea coast. But the former land lies at a distance from the sea; abounds with excellent pastures; and produces large quantities of rice, pepper, cotton, and other things of the like kind, which can neither grow nor be cultivated in a sandy soil impregnated with marine salt. Of a hundred Indian names which belong to towns and villages in those districts, there are scarcely ten which have not been mutilated and corrupted by foreigners. Those who study the history and geography of India in the works of the Europeans, will every moment meet with passages which require to be amended. In order that this may be done in part, I shall here present the reader with an etymological list of the principal places and towns on the coast of Ciòlamandala, or, as the Europeans say, of Coromandel; and shall adhere as much as possible to the orthography of the Indians.

Names of Cities, Towns, &c. in Carnada and Ciòlamandala.

Valiacàda, the great mountain; or Valiacadà, the great passage, or ford, called by the Europeans Pallicate; is a city on the sea coast, at the mouth of a small river. The Dutch have a settlement here.

Ottocutta, or Ottukottei, a solitary city, a solitary castle.

Pondamala, or Pondalamey, a high mountain; from Pondu, high; and Mala or Maley, which, in the Tamulic and Malabar languages, signifies a mountain. It is a fortified mountain, called by the Europeans, Grand Mont.

Madraspatnam; Patnam, the city; Madraspatnam, the city of Madras.

Maïlapuri, or Maïlapuram, the city of peacocks: the Meliapur, or St. Thomas of the Europeans.

[Pg 28] Tirupati, a sacred place, a sacred temple; called by the Europeans Tirupeti. It is situated in Carnada, under 14° N. lat. and 77° 15′ E. lon. It is dedicated to Vishnu, and is much resorted to by people from all parts of India. The pilgrims, who repair thither to perform their devotions, cut off their hair, and bring it as an offering to Vishnu.

Tirunamalà, or Tirunamaley, the sacred mountain; corrupted into Tirnimalet.

Govalam, the circuit of the cow; corrupted Govelan.

Uttamalùr, the good town; corrupted Outremalour.

Arrucati, a city or castle, from which one can see the river Paler; corrupted into Arcate.

Cangipuri, or Congipuram, the golden city; from Puri, or Puram, the city; and Cangi, which in the Samscred signifies gold; corrupted into Cangivaron.

Vencàtighiri, the woody mountain; corrupted into Vincatighiri. It is compounded of Quiri, or Shiri, a mountain; Ven, white; and Cati or Catil, in the forest: a city situated on the mountain where the white forest is.

Ciacrapuri, or Ciacrapuram, the circle city, the round city; corrupted into Sacrapour.

Perumaculam, the large pond, the large bath; corrupted into Permacoul.

Mangalur, the fortunate city, the fortunate town.

Calianatur, the town of joy.

Velur, the town of the lance. At present it is a city.

Villanùr, the town of the arrow. On the maps it is called Villenour.

Puduceri, the next town; on the maps called Pondichery.

Attùr, the town of goats, or the town where the coco-nuts are ground.

Krishavaram, the blessing of the god Krishna: a [Pg 29] town distinguished on the maps by the name of Quichenavaron.

Divycotta, the divine castle; from Divya, divine; and Cotta, a castle or fortress. On the maps it is called Divicoté.

Names of Cities and Towns in the Kingdom of Tanjaur.

Tanjaur, a low situation; or Tanjiaur, a miserable, mean, detestable town. It is the capital of a province of the same name. The former orthography seems to be the properest; for Tanjaur really stands on low ground, which is often exposed to inundations.

Turangaburam, or Turangaburi, the water city, or horse city: by the Europeans called Tranquebar.

Carincala, the black stone, or rock. It is the Carical of the Europeans.

Nàvur, the dogs’ town, or the new town: the Naour of the Europeans.

Tirumaladùvsam, the temple of the God of the Holy Mountain, that is of Shiva. By the Europeans it is called Tiremalevasen.

Nàgapatnam, or Nàgapatana, the city of the snake, or the city of the elephant; for Naga signifies a snake, and likewise an elephant; and Patna, a city. It is the same city as that usually called by the Greeks Nigamos, or Nigama Metropolis.

Tiramannùr the town of the Holy Land: the Tremanour of the Europeans.

Cirangam, or Cirangapatnam, the city of the beautiful limbs: from Cir, beautiful; Anga, a limb; and Patnam, the city. It is the Cheringam of the Europeans[24].

[Pg 30] Celiaolam, the slimy pond; the Chelicolon of the Europeans.

Tricolùr, the town of the three pools, or places of lustration. On the maps it is called Tricoloùr.

Palancotta, the castle of the bridges, for several bridges must be passed before one can arrive at it: from Pàlam, or Pàlan, a bridge; and Cotta, a castle. On the maps it is called Palancottè.

Names of Cities and Towns in the Kingdom of Madura.

Madura, Matura, and Madhura, the lovely, the mild city, or the city of the hero Madhu. It is the capital of the kingdom of Madura, which takes its name from it, but by the Europeans is called Madure. This kingdom is named also Pandi, or [Pg 31] Pandimandala, the land of Pandi, Pando, or Pandava, an ancient Indian king, by whom, according to the opinion of the Brahmans, it was founded. Pliny calls this city Modusa regia Pandionis; but Ptolemy gives it the name of Methora.

Tricinnapalli: from Tri, three; Cinna, small; and Palli, a temple or a school. At present it is the capital of Madura, and on the maps is called Trichenapali.

Manelùr, the town on the sand: a town.

Tindacalla, the dirty stone or rock; on the maps Tinducallu. It is the Tindis of Ptolemy and Arrian.

Tirnaveli, or Tirunnaveli, the place where the tide ends: is at present a considerable city.

Mantòpo, or Mantòpu, the garden on good soil: a city.

Ciangracoil, the temple of Ciangra, or Shiva: on the maps called Sangaravacoil.

Uttamapàleam; from Uttama, the best; and Pàleam, or Pàliyam, the house of government. On the maps it is called Uttamapaleon.

Names of Cities and Towns on the Coast of Pescaria, or, as the ancients called it, Paralia.

Ràmanàthapuram, the city of Rama, of the lord. On the maps it is called Ramanadaburon.

Vayparra, the three large rocks; a town which is situated near these rocks.

Tùtucuri, or Tùducudi, a town or place where linen cloth is washed.

Mannapara, earth and rocks; from Manna, earth; and Pàrra, a rock.

Vadakencolam, a pond or bath towards the north; at present a city.

[Pg 32] Gòvalam, the circuit of the cow; at present a town: the Colis or Colias of the antients, lying not far from Tovala. It is a strong fortress belonging to the king of Travancor, and guards the passage from the kingdom of Madura to Cape Comari. On the maps it is called Covalan.

Names of Cities and Towns in the Kingdom of Maissur.

Maissùr; from Maï, colour; and Ur, a land; Maissùr, the land of colour. It is not improbable that it obtained this name either from the reddish earth found there in abundance, or the dye plants it produces, and with which the cotton cloth is dyed. This kingdom lies between Carnada, Madura, and the coast of Malabar.

Bengalùr, the white land, the white earth. This name is given to the capital where the nabob Hayder Aly Khan formerly resided. It is a considerable city, strongly fortified.

Ciringapatnam, the capital and fortress where the nabob Tippoo Sultan Bahader resides. It lies at the distance of twenty leagues from Bengalur, towards the west. On the maps it is called Chiringapatnam.

Dhermapuri, the city of good works, or the city of virtue; from Dherma, virtue; and Puri, a city. On the maps it is called Darmapuri.

Dharàburam, or Dharàpuram, the city where the rain water runs off; for it lies at the bottom of that ridge of mountains called the Gauts, from which the water pours down in torrents. On the maps it is called Daraburu.

Budhapadi, the town of Budha, an Indian idol. On the maps, Budapari.

Gòculatùr: from Go, a cow; Cula, a herd; and Ur, [Pg 33] the land or town; consequently the land of the herds of cows. On the map, Guclaturu.

Cinnabellapuram, the small city of strength. On the maps called Sinnaba’lambaram.

Ciandrapati, or Tschandrapadi, the spot in the moon. On the maps Sandarupati.

Of such changed and corrupted names a great many more might be produced, but most of them so mutilated, that their real meaning can no longer be guessed, and people would only lose themselves in uncertain conjectures if they endeavoured to discover their etymological origin. It, however, appears by those above mentioned, that some of the Indian cities and towns received their names from Indian deities, others from local circumstances or the nature of their situation; and that such appellations cannot have originated from the Egyptians, Persians, Greeks, or Romans. In the eastern part of India no traces of Sesostris or the Greeks are to be found, as some learned men in Europe have erroneously asserted. That India was already civilised in the time of Sesostris, shall be proved hereafter. In regard to the Grecian language and mythology, these were not known in India before the invasion of Alexander the Great, and even then only in some of the maritime cities of the northern part of the country[25].

After this digression I shall now give a short account of the kingdoms of Madura, Tanjaur, and Carnada, according to the information I received from the missionaries resident in those countries; for, [Pg 34] as I was not able to remain longer on the coast of Ciòlamandala than from the 26th of July till the 20th of October, it was impossible for me in the course of these few months to learn, by my own experience, every thing that regards this remarkable land. The reader, therefore, will not take it amiss, if I here insert what was communicated to me by intelligent missionaries, who had spent the greater part of their lives in those provinces.

Geographical, statistical, and historical Observations on the Kingdoms of Tanjaur, Marava, Madura, and Carnada.

THE principal cities in the northern part of India are the following:

Caschemir, which, according to the map published at Paris in the year 1781, is situated under the 35th degree of north latitude. This city is certainly the Caspira or Caspirus of Herodotus, as D’Anville has already very properly observed[26].

Cabul, a city which, on the side of Persia, is as it were the key of India. It was obliged formerly to pay tria millia nummum talenta to Alexander the Great, as he was returning from the war against Porus. It lies in the latitude of 34°[27].

Tatta, or Tattanagar, occurs in Pliny under the name of Pattala, or Pattalena, and is situated at the mouth of the Indus, or Sindhu. In this city Apollonius of Tyana once resided a month. It contained formerly 30,000 looms employed in weaving cotton cloth.

Hastinapuri, in the Samscred Hastinanagari, called by others very improperly Assanapur, or Hassnapur, and by D’Anville Astanagar. At present it is known by the name of Hassanabad, and is the first and oldest city in all India. It lies in the latitude [Pg 36] of 32° and a few minutes. In the book Bharada the following passage occurs respecting it:

That is: “King Hasti built a city, and therefore it was called Hastinapuri, from king Hasti.” Its inhabitants, and in all probability some of its kings, were once subdued by the Assyrians: afterwards they fell under the dominion of Cyrus, to whom they were obliged to pay tribute. The celebrated Indian kings known by the names of Pandu, Pando, or Pandavi, resided thirteen months in the city of Hastinapuri. They lived 1550, and not 3102, years before the birth of Christ, as Mr. Wilkins erroneously asserts. It appears from my copy of the work called Bharada, written on palm leaves, that Hastinapuri existed a long time before these Pandos or Pandavi, and was built at least 2000 years before Christ, consequently must be of the same antiquity as the Assyrian monarchy. The consort of king Hasti was named Ashodara, and was a daughter of king Trigarta. They had a son called Vikugnen, who married Sumanda a daughter of king Dashahanda[28].

The city Dionysiopolis, mentioned by Ptolemy and Arrian[29], is Nisa, the city of Devanishi, that is of Dionysius, or the Indian Bacchus. In the Samscred language it is called Shrinagari, which signifies the city of the celebrated, the fortunate, or the blessed Bacchus[30]. It is called also Nishadabury or Naishadabur, [Pg 37] that is, the city Nisa. It lies in the latitude of 31°, on the river Allakandara, which discharges itself into the Ganges. According to the assertion of St. Jerome, it was built by Bacchus 550 years after the birth of Abraham. Pallibothra was likewise built by Bacchus. That city, however, is neither the present Patna on the Ganges, as Major Rennel pretends, nor Eleabad, or Allahabad, which lies also on the Ganges, in the latitude of 25 degrees and some minutes; but Pallipatur, now a small town on the river Yamunà, at its influx into the Ganges, in the latitude of 26°. Robertson and D’Anville, who assert that Pallibothra is the present Eleabad, or Allahabad, deserve no credit; because these appellations are of Persian and not of Indian extraction[31].

Benares, Venares, or Kasi, a celebrated temple, together with an academy and an observatory, is situated on the Ganges, in the latitude of 25°, and is the Cassidia of the ancients[32].

Ayodhya, an ancient Indian city, where the first Indian monarchs on the Ganges resided, was situated on the river Deva, in the latitude of 25°, exactly in the spot where Faizabad now stands. It was the birth-place of Shiràna, or Rama, an Indian hero, or the younger Bacchus, whose heroic achievements were celebrated in songs before the times of the Pagan Indians.

Modhura, or Moturapuri, called by Pliny Modura [Pg 38] Deorum, is also a very ancient city, lying between Agra and Delhi, in the latitude of 27°. It is the birth-place of the god Krishna, or the Indian Apollo, who here tended his herds. For this reason it is called likewise Gocula and Ambàdi, that is, the circuit of the cows. It is situated on the river Yamuna, for which the Pagans have the utmost veneration.

Eloura or Illoura, properly Ellur, the city of sesamum, is at present a town called Douletabad. It lies four Indian miles to the north-west of Aurungabad. There is here a very ancient and celebrated temple, a description of which has been given by Thevenot.

Canudi, and not Canouge, as Renaudot writes, is an ancient city, the residence of the first Indian kings. The five brothers Pandu, or Pando, who make so great a figure in the ancient history of India, kept here their court. It lies in the latitude of 27°, on the river Càlini, at the place where it discharges itself into the Ganges.

Patna, a celebrated city on the Ganges, is placed in Father Tiefenthaler’s map under the latitude of 25°. It contains a million and a half of inhabitants, according to the assertion of Father Marcus a Tumba, who has written a description of it. The English have here a council and government, who are, however, subordinate to the supreme council at Calcutta.

A more minute account of Indian cities and places may be found in Tiefenthaler’s description of Hindostan, Anquetil du Perron’s Historical and Geographical Researches, Rennel’s Memoir, and a very important manuscript of Father Marcus a Tumba, preserved in the Borgian museum at Velitri, and entitled Su i luoghi santi dell’ India. My object was merely to mention some places in the southern part of India, which have been passed over in silence by the above writers.

According to the assertion of the before mentioned [Pg 39] Capuchin, Father Marcus a Tumba, who resided a long time as missionary at Patna and Tschandranagar, the Chandernagor of the French, the flux and reflux of the sea extend, by means of the Ganges, more than sixty leagues into the country, so that ships of war can proceed that far up the river. On the Dèva or Sarayuva vessels can go even to Delhi, and on the river Son to Rotasgar. The English possess, on the Ganges, the cities of Calcutta, Monguiri, Patna, Benares, and Allahabad or Eleabad, and have at all these places factories, fortresses, governors, and collectors of the public revenues. The province of Bengal alone brings them an annual income of above three millions sterling. It appears from a letter of Mr. Hastings, formerly governor-general of Bengal, that the English ships which sailed from that settlement between the 1st of December 1782, and the 1st of January 1784, had on board goods to the value of two cores (or codi) and sixty-five lack of rupees[33]. A rupee is equal in value to five Roman paoli; a hundred thousand rupees make one lack; and a hundred lac, a core or codi. This immense sum was exported too at a time when the English were involved in a war with the Indian princes; but to how much will their exports at last amount in times of war?—Their great revenues will and must infallibly decrease hereafter; for, in the first place, the natives are too much oppressed: 2dly, In a state of continual warfare and plundering, agriculture is neglected: 3dly, Trade and manufactures decline: 4thly, The country is ruined by monopolies: 5thly, An immense quantity of specie has been drawn from it of late years; and at present much fewer rupees and pagodas are seen in circulation than formerly[34].

[Pg 40] Those who wish to form a clear idea of the degraded condition of the greater part of the Indian kings and princes in the southern and northern part of India, must recur to the hostile invasions by which foreign conquerors reduced those countries under their dominion. In the year 1202 the Tartar Gingsa Khan, or Gengis Khan, made an incursion into the kingdom of Tangut, and in 1209 into India. He was followed in 1409, two centuries later, by Timur Bec, or Tamerlan, when he had crushed the dynasty of the Moguls, which afterwards was divided into two branches, the eastern and the western. Timur established himself in the neighbourhood of Agra; expelled, as far as his power extended, the legal Indian kings and princes; and committed the care of the provinces he had subdued to nabobs and governors of his own appointment. This was the first time that the Mogul Tartars took possession of India. Some writers assert, that Gengis Khan did not enter India till the year 1218, and that the conquest of that country by Timur falls about the year 1398. However this may be, Mir Shah, called by some Mirzan Pir Mohamed, kept possession of the northern part of India for several years, and composed for his subjects a new code of laws according to the political system of the Moguls. The next conqueror of India was Abu Said Shemor Ami Shah, who reigned [Pg 41] in 1493. During the persecution which Timur permitted against the Indians, the Gypsies, who belonged originally to the caste of the Pareas, a people residing on the Sindhu, or Indus, fled from their native country, wandered through Scythia, and, proceeding thence to Hungary, dispersed themselves over various parts of Europe[35]. In the year 1519, or, according to some, 1526, the celebrated conqueror Bahur, a descendant of Timur, extended the Mogul empire in India; or was rather, as some assert, the real founder of it. He had four sons, Homaon or Omayoun, Sehir Shah, Selim Shah, and Firuz Shah, who reigned after him. In the year 1550, or 1556, Akbar the wise, a son of Homaon, rebuilt the city of Agra, introduced new laws, and appointed new nabobs or viceroys in the provinces. He caused various Indian books to be translated also into the Persian language; and among these were [Pg 42] the work called Mahabhàrada, and another named Ayin Akberi. The latter was a book of Indian laws, which had been collected by his minister Albufazel. Akbar died in 1605, and was succeeded by Gehanguir. The latter had five sons, one of whom swayed the sceptre of the kingdom of Dàkshima or Decan, which he had subdued by force. In 1627 Gehanguir was followed by Shah Gehan, who also left behind him five sons. According to some, however, a prince named Bolasci reigned a considerable time before him. Akbar restored to the Brahmans their observatory at Benares, in order that they might continue their astronomical observations, which had been long interrupted by the war. Gehanguir, on the other hand, had no taste for the sciences, and could not prevail upon himself to tread in the footsteps of his father: both he and Shah Gehan were rather formed for war. These Moguls made an incursion, for the first time, into the kingdom of Carnate, or more properly Carnada, in 1632 or 1633; and they thence over-ran the southern part of India, into which no foreign conqueror had ever before penetrated. Shah Gehan transferred the seat of government from Agra to Delhi. The dominion of the Moguls was still farther extended under the reign of Aurengzeb, one of the sons of Shah Gehan. This prince conquered, in 1686, the kingdoms of Velur, Visapur, and Goloonda; in 1695, subdued Carnada a second time; and, in 1698, made himself master of the provinces of Gingi, Satara, and Panin. Major Rennel says, that the revenue of this monarch amounted annually to thirty-five millions sterling. He died in 1707, and left four sons, one of whom, Shah Alem, assumed the reins of government the same year. The latter had two sons, who reigned till the year 1739. Their successor Shah Mohamed was dethroned by Thamas Kuli Khan, who [Pg 43] plundered the treasury, levied exorbitant contributions from the people, and carried off an immense booty. Thamas Kuli Khan, or Nadir Shah, was followed in 1748 by Achmet Shah, a son of Mohamed Shah. After this the throne of Delhi was possessed from 1756 to 1760 by Azizeddoulah or Alemguirsani, king of the Patans. Under the government of this prince almost all the nabobs refused obedience to his lawful commands. The districts over which they presided as viceroys being of considerable extent, and at a great distance from Delhi, it was therefore much easier for them to render themselves totally independent. His son was deprived of the throne by his own prime minister; and bloody feuds ensued, which continued, without interruption, till the year 1773. As it was far more advantageous, in every case, to have to contend with several weak and petty princes, than so formidable and powerful a monarch, the English, during this state of warfare, considered it as of great importance to support the rebellious nabobs against their supreme lord, in order that they might establish themselves more firmly in the possession of their colonies, and at the same time have allies in case of need. After this period the power of the Great Mogul sunk into nothing. The policy by which the English, as well as the Subadars, or Mogul governors, effected this change, may be found circumstantially described in Pallebot de St. Lubin’s Historical Memoirs, under the head Revolutions of Bengal. The Seiks, whom I consider as a people originally Christians, but who again adopted the Pagan religion, taking up arms, now entered in a hostile manner into Lahor, Multan, Delhi, and other possessions of the Great Mogul; while the English, in another quarter, combining their own private interest with that of the rebellious nabobs or viceroys, made themselves masters of several provinces [Pg 44] also: and thus this mighty empire, notwithstanding its greatness, its monstrous extent, and its riches, sunk back into its former insignificance. After this period nothing but war and contention prevailed in Carnate, Tanjaur, Gingi, Madura, and Maissur, and in all the provinces, of which I shall soon give a more particular account.

The first province on the coast of Ciòlamandala, which begins in the south-west, and extends towards the north-east, is Marava, the capital of which, having the same name, is situated, according to M. De la Tour, in the latitude of 9° 35′ north; as appears by the map which he published at Paris, in 1770, under the title of Theatre de la Guerre dans l’Inde. This map, which was constructed with great accuracy on the coast of Ciòlamandala, exhibits with much clearness and precision the different districts, cities, and rivers in the theatre of the war carried on by the English, French and Indians against each other, as well as the boundaries of these districts, and the principal roads through them. It was constructed by order of the French government for the trial of Count Lally, who had been governor of Puduceri. I consider it as much more correct than the map of the Brahmans, which Anquetil du Perron has inserted under the title of Portion d’une Carte du Sud de la presqu’Isle de l’Inde, faite par des Brahmes, in the first part of his Récherches Historiques et Geographiques sur l’Inde, published at Berlin in 1786. The Brahmans were unprovided with good astronomical instruments, and consequently not in a condition to construct an accurate map.

The province of Marava is bounded on the east and south by the sea, on the north by Tanjaur, and on the west by Madura. It is intersected by the Veyarru, that is, the great river, which flows down from the Gauts, divides the kingdom of Madura or [Pg 45] Pandi into two parts, and, running past the ancient city of Madura, spreads itself through the province of Marava into several branches. By means of this river vessels can be navigated to the sea through both the before-mentioned provinces, in a direction from west to east; but it is exceedingly difficult and laborious to return. While the flood, called by the Indians Velli, continues, there is no impediment, as it each time drives the vessel three or four miles up the country; but when it is over, the troublesome part of the navigation commences, because the sailors must then row against the stream with all their strength. The case is the same, in general, on the coasts of Ciòlamandala and Malabar, with all the rivers which flow down from the Gauts, and which for the most part have their sources in that ridge of mountains. But with whatever difficulties this return may be attended, the advantages procured by these rivers to the inhabitants of the surrounding districts are of the utmost importance. They facilitate inland as well as foreign trade, render the soil fruitful, purify and cool the air; in a word, it is to be ascribed to them alone that the country is habitable by human beings; which certainly would have been impossible, had not Providence placed in this part of the torrid zone that immense ridge, and supplied it so abundantly with water.

The principal cities in the province of Marava are: Elluvancotta, Ciangucotta, Tiruvananganur, Ciòlaburam, Kavaricotta, and Ràmanàthapuram, of which I have already spoken. The country is covered with forests, underwood, and shrubs. The inhabitants are rude and uncultivated. The men, though of low stature, are strongly built and excellent warriors. I saw several of them, who had behaved with great gallantry in the war which Rama Varmer, the king of Travancor, carried on against the nabob Tippoo Sultan [Pg 46] Babader. Each wore around his head a turban of blue cotton cloth; had a white jacket which descended to his thighs, a sabre by his side; in his right hand a lance, and in his left a shield. These people march, however, in bodies without any certain order, and perform their evolutions by the sound of a horn. They let their beards grow; have coarse hands and faces; go bare-footed; and wear a blue girdle around the body. They are much braver than the Tamulians, who can never be accustomed to the fatigues of a military life.

Marava was formerly a province of the kingdom of Madura. The ruler of it was called Nyaquen, that is, the lord; but the Europeans have corrupted this word, and made of it Naik or Naiken. The northern part of Marava is at present under the dominion of the nabob Mohamed Aly and his friends the English; but the western is subject to the king of Travancor, who possesses also a part of Madura and Marava on the east, from Cape Comari, in consequence of a treaty which he entered into with the English and Mohamed Aly. This king of Travancor, however, is obliged to pay the Coppa, that is, a yearly tribute, to Mohamed Aly, who may be called a creature of the English, and whom they generally employ as a state engine when they wish to exercise their oppression against the Indian princes. The Jesuits formerly had a great many Christian congregations in Marava, and this missionary establishment was connected with those in Tanjaur and Madura; but, in my time, these congregations had for the most part dropped off; and the few still remaining were under the direction of priests from Goa, who did not bestow too much attention upon them. The interior parts of Madura and Marava, in matters of spiritual judicature, are subject to the archbishop of Cudnegalur or Craugalor; and places on the sea-coast, which do not extend [Pg 47] farther than ten miles into the country, belong to the diocese of the bishop of Cochin.

Tanjaur lies between the tenth and eleventh degree of latitude, and 25 seconds farther towards the north east. This kingdom is bounded on the south by the sea and the province of Marava, not far from the fortress of Tiruvananganur, which belongs to Marava. On the east it is washed also by the sea, and towards the north by the rivers Cavèri and Colàrru, the latter of which is very improperly written Colram. In the Samscred language it signifies the river of the wild hogs; from Cola a wild hog, and Arru a river; for these animals were formerly found there in great abundance. Both these rivers, the Cavèri and Colàrru, are exceedingly large, and are held in as great veneration by the eastern Indians as the Ganges is by the northern. Those who belong to the sect of the Vishnuvites, address their prayers to Vishnu as the ruler of the waters; and they believe that he created the universe from water: for this reason they perform their lustrations at rivers, and on their return carry with them some bits of yellow earth, which they pick up on the banks. When an individual of this sect dies, his body is burnt, and the ashes are thrown into one of these rivers. From this it appears that the Indians show divine honours to the elements after the manner of the ancient Persians.