Title: The Minute Boys of South Carolina

A story of "How we boys aided Marion the Swamp Fox"

Author: James Otis

Illustrator: J. W. Kennedy

Release date: July 15, 2025 [eBook #76504]

Language: English

Original publication: Boston: Dana Estes & Company, 1907

Credits: Aaron Adrignola, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

AMERICAN HISTORY

STORIES FOR BOYS

THE MINUTE BOYS SERIES

The Minute Boys of Lexington

The Minute Boys of Bunker Hill

By Edward Stratemeyer

The Minute Boys of the Green Mountains

The Minute Boys of the Mohawk Valley

The Minute Boys of the Wyoming Valley

The Minute Boys of South Carolina

The Minute Boys of Long Island

By James Otis

THE MEXICAN WAR SERIES

By Capt. Ralph Bonehill

For the Liberty of Texas

With Taylor on the Rio Grande

Under Scott in Mexico

DANA ESTES & COMPANY

Publishers

Estes Press, Summer St., Boston

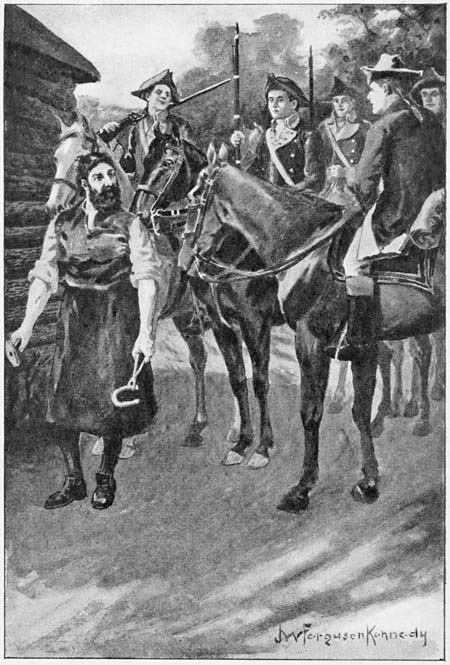

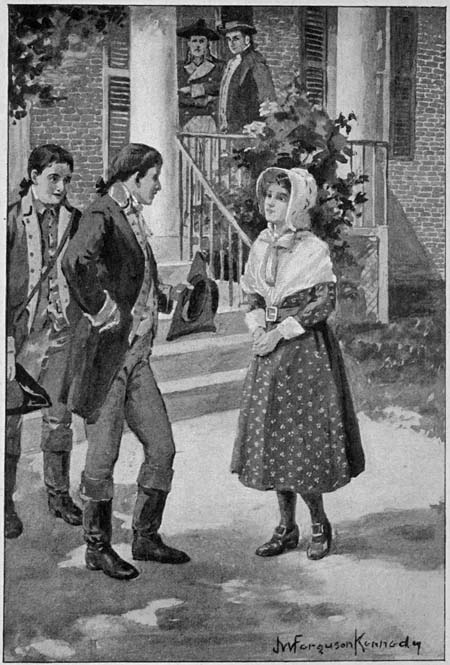

“‘I WILL TAKE YOUR LIFE AS FORFEIT FOR TREACHERY!’”

(See page 281.)

THE

MINUTE BOYS

OF SOUTH CAROLINA

A STORY OF “HOW WE BOYS AIDED

MARION THE SWAMP FOX”

AS TOLD BY

RUFUS RANDOLPH

JAMES OTIS

Illustrated by

J. W. F. KENNEDY

BOSTON

DANA ESTES & COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1907

By Dana Estes & Company

All rights reserved

COLONIAL PRESS

Electrotyped and Printed by C. H. Simonds & Co.

Boston, U. S. A.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| Foreword | v | |

| I. | Gabriel and Rufus | 11 |

| II. | The Pursuit | 28 |

| III. | Recruits | 47 |

| IV. | Disappointment | 67 |

| V. | Barfield’s Camp | 87 |

| VI. | The Rescue | 103 |

| VII. | Nelson’s Ferry | 121 |

| VIII. | The Prisoners | 140 |

| IX. | A Trap | 159 |

| X. | An Odd Battle | 179 |

| XI. | Our Retreat | 198 |

| XII. | A Mysterious Escape | 217 |

| XIII. | The Search for the Traitor | 236 |

| XIV. | A Queer Message | 254 |

| XV. | Rowe’s Smithy | 273 |

| XVI. | A Skirmish in the Dark | 292 |

| XVII. | Seth Hastings Once More | 310 |

| XVIII. | Manœuvring for Position | 326 |

| XIX. | A Dastardly Blow | 344 |

| PAGE | |

| “‘I will take your life as forfeit for treachery!’” (See page 281) | Frontispiece |

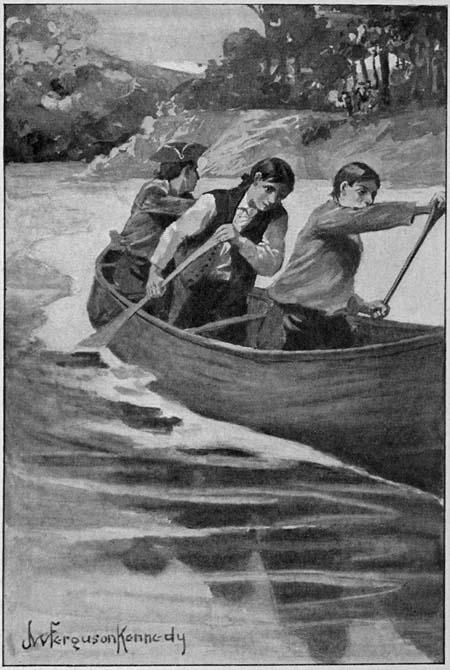

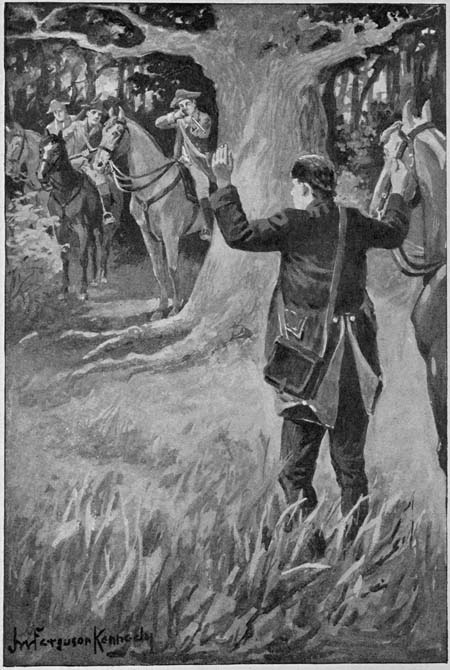

| “‘Five minutes longer and we shall be out of range!’” | 32 |

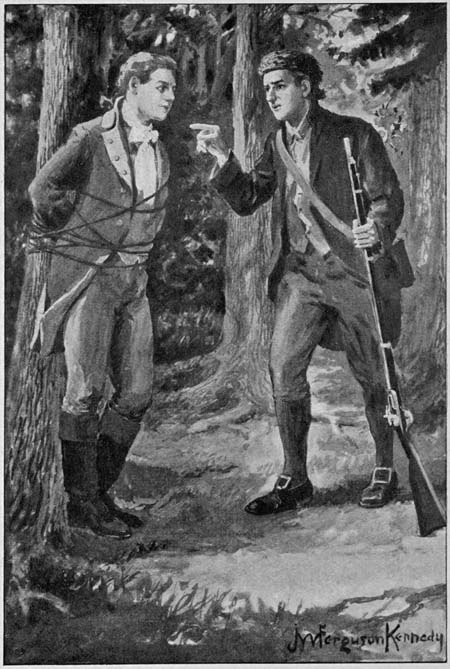

| “‘Dismount and throw down your weapons!’” | 80 |

| “If it had not been for Seth Hastings, I should have considered myself exceedingly fortunate” | 112 |

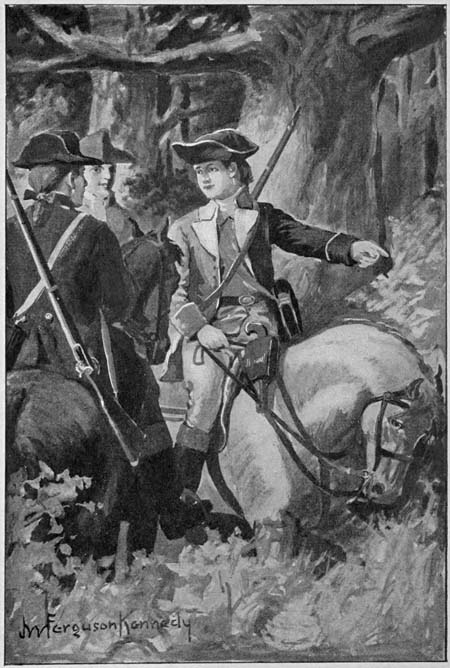

| “‘I propose that we halt here’” | 123 |

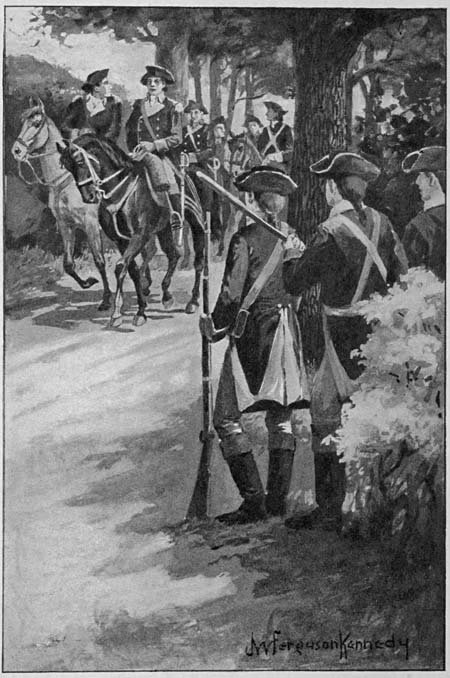

| “Then we saw coming through the avenue of trees our ‘Swamp Fox’” | 196 |

| “‘Are you master davis’s daughter?’” | 265 |

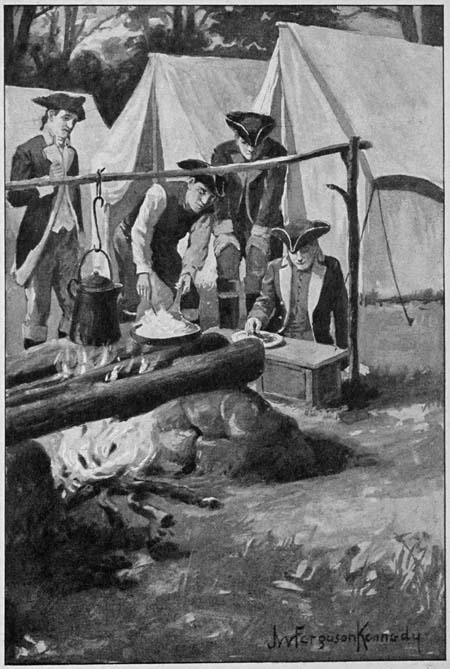

| “‘And we are to leave all these camp equipments?’” | 314 |

[v]

It has always seemed proper to me that he who writes a story should explain to the readers how it came about that he was prompted to tell the tale, for surely there must be a good and sufficient reason for the making of a book, and it also comes to my mind that however dry and uninteresting such an explanation may be, he who reads the story owes it to himself, as well as the author, to learn all he can regarding the facts, however remote, which may pertain to the characters presented, and yet be of such a nature that the author cannot well, without sacrificing his own plans, deviate sufficiently to relate them in the book itself.

Therefore it is that I shall be grateful to the reader if he will set down in his own mind certain passages from history which are quoted below, to the end that he may the better understand why two lads born and bred in Charleston, in the State of South Carolina, left their homes at a time when the cause of liberty appeared to be crushed to earth, and why they followed the desperate ventures of[vi] Francis Marion during his unequal but wondrously successful struggle against an enemy which was bent on trampling into the mire the patriots who strove to rear a country for themselves in the New World.

Shortly after the publication of the story entitled “The Minute Boys of the Mohawk Valley,” a gentleman residing at Charleston sent to me a packet of closely written pages, stained by time, and with the ink so faded that only with difficulty certain portions could be read. I was richly rewarded, however, for the labor spent in reading that which was set down, for I found that the manuscript was neither more nor less than a series of letters connected, evidently at a later date, by memoranda, and all written by one Rufus Randolph, a distant relative of Francis and Gabriel Marion.

To make of the whole a story, such as entertained myself at least, was a trifling task compared with the labor which had been performed by the young writer, and verily it was a labor of love, for while working over the faded pages I came to learn many things concerning that heroic struggle which the “Swamp Fox” made against overwhelming forces bent on devastating the fair colony of South Carolina, and I have done little more in the pages which follow than transcribe his own story.

So much for the reason why “The Minute Boys of South Carolina” has been put into print, and now, because Rufus Randolph failed to set down anything concerning those terrible days after Sir[vii] Henry Clinton captured the city of Charleston, I ask that the following extracts from the historian Lossing’s “Field Book of the Revolution,” a goodly portion of which I have condensed lest one weary with the reading, be studied with some care.

“The fall of Charleston, and loss of Lincoln’s army, paralyzed the Republican strength at the South, and the British commanders confidently believed that the finishing-stroke of the war had been given.”

“Clinton sailed for New York on the fifth of June, leaving Cornwallis in chief command of the British troops at the South. Before his departure, Clinton issued a proclamation, declaring all persons not in military service, who were prisoners at Charleston, released from their paroles, provided they returned to their allegiance as subjects of Great Britain. So far, well; but not the sequel. All persons refusing to comply with this requisition were declared to be enemies and rebels, and were to be treated accordingly. And more; they were required to enroll themselves as militia under the king’s standard. This flagrant violation of the terms of capitulation aroused a spirit of indignant defiance, which proved a powerful lever in overturning the royal power in the South. Many considered themselves released from all the obligations of their paroles, and immediately armed themselves in defence of their homes and country, while others refused to exchange their paroles for any new conditions. The silent influence of eminent citizens who took this course was now perceived by Cornwallis,[viii] and, in further violation of the conditions of capitulation, he sent many leading men of Charleston as close prisoners to St. Augustine, while a large number of the Continental soldiers were cast into the loathsome prison-ships, and other vessels in the harbor.”

“But when the trumpet-blasts of the conqueror of Burgoyne were heard upon the Roanoke, and the brave hearts of Virginia and North Carolina were gathering around the standard of Gates, the patriots of the South lifted up their heads, and many of them, like Samson rising in strength, broke the feeble cords of ‘paroles’ and ‘protections,’ and smote the Philistines of the crown with mighty energy. Sumter sounded the bugle among the hills on the Catawba and Broad Rivers; Marion’s shrill whistle rang amid the swamps on the Pedee; and Pickens and Clarke called forth the brave sons of liberty upon the banks of the Saluda, the Savannah, the Ogeechee, and the Alatamaha.

“Fortunately for the Republican cause, an accident prevented Marion being among the prisoners when Charleston fell, and he was yet at liberty, having no parole to violate, to arouse his countrymen to make further efforts against the invaders. While yet unable to be active, he took refuge in the swamps upon the Black River, while Governor Rutledge, Colonel Horry, and others, who had escaped the disasters at Charleston, were in North Carolina arousing the people of that State to meet the danger which stood menacing upon its southern border. Marion’s military genius and great bravery[ix] were known to friends and foes, and while the latter sought to entrap him, the former held over him the shield of their vigilance. ‘In the moment of alarm he was sped from house to house, from tree to thicket, from the thicket to the swamp.’”

“It was while in the camp of Gates that Governor Rutledge, who also was there, commissioned Marion a brigadier, and he sped to the district of Williamsburg, between the Santee and Pedee, to lead its rising patriots to the field of active military duties. They had accepted the protection of British power after Charleston was surrendered, in common with their subdued brethren of the low country; but when Clinton’s proclamation was promulgated, making active service for the crown or the penalty of rebellion an alternative, they eagerly chose the latter, and lifted the strong arm-resistance to tyranny. They called Marion to be their leader, and of these men he formed his efficient brigade, the terror of British scouts and outposts. Near the mouth of Lynch’s Creek he assumed the command, and among the interminable swamps upon Snow’s Island, near the junction of that stream with the Great Pedee, he made his chief rendezvous during the greater portion of his independent partisan warfare.”

Having thus refreshed your memory with the facts just given, remember that that which follows is the work of Rufus Randolph, and not of your friend,

James Otis.

[x]

THE MINUTE BOYS OF

SOUTH CAROLINA

The king’s forces laid siege to Charleston, in the State of South Carolina, on the very day that Gabriel Marion was sixteen years old, and when I was come to the same age the Continental forces made their first sortie, as I remember full well because of the fact that General Moultre’s brother was then killed. Thus it will be seen that Gabriel was my senior only by fifteen days, for it must be fresh in the minds of every one that Sir Henry Clinton opened fire on Charleston the fifth day of April, in the year of grace 1780; that the Americans made their first sortie on the twentieth; that on the sixth day of May the besiegers completed their third parallel, and on the twelfth the city was in the possession of the king’s troops.

There is no good reason why I should go into details concerning the siege and capture of Charleston, because they are well known to everybody;[12] but I have used the facts as a starting-point of what may prove to be a story such as can be told to lads who shall live after I have gone out of this world. It seems no more than proper to do so, for it was while the British shot and shell were screaming over our heads as we aided in the defence as boys might, that Gabriel Marion, brother of that General Marion whom the minions of the king dubbed “Swamp Fox,” determined to profit by the example which the lads in the eastern States had set us, and once the time should be ripe, band the lads of South Carolina together under the name of Minute Boys.

Many a time, as Gabriel and I staggered here and there under the burden of ammunition for our elders, who had permitted that we take part in the defence to the extent of supplying the different guns with powder and ball,—and so small was our store that we were forced now and again to carry it an exceeding long distance,—many a time, as I have said, while we were thus engaged Gabriel and I turned the matter over in our minds, vowing that as soon as the king’s hirelings had been beaten back, as we had no doubt soon would be the case, the Minute Boys of South Carolina should come into existence as an organization distinct from the regular army.

Warm friends were Gabriel and I, with never a difference between us save when, owing to the fact that my name was Rufus and my hair all too vividly red for my own pleasure, he would persist in calling me William Rufus, giving me the name[13] of that king who was known as “The Red,” and it vexed me sorely at times, because, although not responsible for my personal appearance, the shock of red hair with which nature had endowed me was so conspicuous as to call forth comment from all who saw it for the first time.

It was as if he called me “carrot-top,” when he tacked on to my name Rufus, that of William, because the youngest schoolboy knows that William Rufus’s hair showed out so conspicuous that his soldiers were as prone to follow it into battle, when perchance a lock was exposed beneath his helmet, as they were to rally around his flag.

However, the color of my hair, and what Gabriel Marion might say in sport regarding it, has nothing to do with that which I propose to set down, save that it will serve to show now and again why I lost control of my temper on being greeted by the name of a king.

Gabriel Marion lived with his brother, Francis, who was made lieutenant-colonel at Savannah the year previous to the siege, in St. John’s Parish, but at the time when Clinton appeared off Edisto Inlet, the colonel was ordered to Charleston, and with him came Gabriel who took up his abode in my home, for it was in that fair city I had been born.

As you know, Charleston was surrendered on terms which to some seemed honorable, while others declared them to be humiliating, and then came that proclamation from Sir Henry Clinton which aroused the ire of every person, young or[14] old, male or female, in South Carolina. Following closely upon it, as if it were but the natural sequel, came the arrest of Lieutenant-Governor Gadsen and seventy-seven of the most influential men, thus giving all our people to understand how little of faith we could put in any declaration of those who had invaded our land. After that August morning, when we saw the chief men of the city marched away to the loathsome prison-ships in the harbor, there was but one desire in the hearts of those who hoped to see their State rid of the oppressive yoke which the king had put upon it, and that was to flee to some place where they might act the part they had sworn to act, and each do his full share toward making reprisals, for the victory of the king’s forces had well-nigh crushed out from our breasts the belief that we might make of the States so lately declared free and independent, a nation of freemen.

I am not minded to go into detail concerning the flight of this family or that from the stricken city, as there is in the story so much of sorrow, or pain, ay, of shame, that it is not well to let the mind rest upon it. Rather should we think of what has been accomplished since, of how we wiped out the disgrace, if disgrace it can be called when our people were whipped through sheer strength of numbers rather than superior bravery or better knowledge of warfare.

Suffice it to say that among those who did steal secretly out of the city, or tried to do so, vowing to avenge the wrongs that had been perpetrated,[15] were Gabriel Marion and I. My mother and invalid father had set off for General Marion’s home on the very day after the capitulation, and I was left to follow my own inclinations so that they had the bent of my father’s advice, which was that, although not a man in years, it was my duty to do a man’s full work in striking off the shackles which the king’s misrule had fastened upon us.

It was not as easy for two stout lads like Gabriel and myself to leave the city as it was for the women, the sick, or the helpless, and before we found an opportunity to give the redcoats the slip, word was brought by a negro, who had contrived to make his way through the British lines with a message of mouth, that General Marion, his broken leg having been healed and he made brigadier-general, had fled to Snow’s Island, where he awaited the coming of those who were eager to continue in arms against the victorious foe.

And now, just a word in regard to the rendezvous, lest some there be who may not understand how an island can be situated inland, or where this particular place is located. In Williamsburg district, where the Great Pedee is joined by Lynch’s Creek, the united streams are divided for a certain distance by a swampy piece of land with here and there solid ground upon it. The rivers come together again at the mouth, thus forming what we call Snow’s Island. Desperate indeed must be the fortune of those who would seek such a refuge, for a guide was necessary in order to lead one safely across the swamp-lands on either side of the river[16] to the few places where a man might lie down without fear of being drowned. The only advantage it could possess was that the enemy might not come upon it readily, and never gain the solid portion of the surrounding country without being piloted by those who knew well the devious passages.

Now you can understand why Gabriel’s brother was dubbed the “Swamp Fox” by those who sought so vainly to entrap him, and you may also have some faint idea of the hardships which we two lads knew must be encountered before we could gain the rendezvous, for more than two-thirds of the journey must be made over morass and swamp not unlike that which I have just been describing.

However, we had little care, time, or thought for the dangers to be encountered, because we were fleeing from that peril which seemed greater than any we could meet, and it was by no means imaginary. We had already seen the chief men of Charleston marched under heavy guard to the prison-ships, where were horrors so great that it would chill the blood of one to describe them, and if Sir Henry Clinton’s forces dared lay hands upon the leading citizens of South Carolina, we knew full well that two lads like ourselves would have but short shrift if peradventure they had cause to suspect us of what they were pleased to call treason.

Our plan, if indeed we had a plan at that time, was to take a boat up Cooper River, thence into the West River to that portion of St. John’s Parish where was located Gabriel’s home, and trust to the[17] chance of getting horses there; strike straight across the country to Gardine’s Ferry, and thence to Snow’s Island as the disposition of the British forces would allow.

Since we could not form a company of Minute Boys very well with but two members, before setting out we cast about for such of our acquaintances as were sufficiently strong in the backbone to permit of their sharing the dangers with us, and the first to whom we unfolded our plan was Archie Gordon.

But few words were necessary to enlist him in this scheme. Although a full year younger than Gabriel and I, he was possessed with the same fever to exact reprisals from the foe as were we, and without waiting until all our half-formed plans should have been detailed, he announced his purpose of joining us, declaring that he was not only ready to set out immediately, but happened to know where we might find a skiff which would be suited to our purpose.

While we were talking with him, Seth Hastings, a lad of seventeen years or thereabouts, came up, and I would have held my peace while he lingered near by, because of ever having distrusted the lad. His shifty eyes, which refused to look squarely upon one; his love of telling a lie when the truth would have served him better; the fact that he would betray one playmate, if opportunity arose, to another in the hope of provoking some small quarrel—all these things combined to make me suspicious of the lad even when he spoke most fairly, and I would[18] almost as soon have gone to the red-coated soldiers with the plan as to have confided it to Seth Hastings.

But Gabriel Marion, who could never see aught of evil in any person save those who wore the king’s livery, welcomed him heartily as he came up, and without waiting to learn if Archie and I were of the mind to enlist this possible recruit, at once acquainted him with the plan, urging that he enroll himself with us as Minute Boys of South Carolina.

It may have been that I was overly suspicious, for perhaps at that moment Seth had no idea of playing the traitor to those whom he called comrades; but I fancied there was in his eyes a gleam of—I know not what to call it, yet the look which was in those shifty orbs disquieted me, and I would have given much had it been possible to recall Gabriel’s incautious words.

They had been spoken, however; Seth Hastings was in possession of our secret, which, if known to the British commander or any of his staff, would have consigned us instantly to the reeking, filthy prison-ships where so many brave hearts were languishing nigh unto death. He knew all our plan, and it was too late to draw back.

While Gabriel argued with him as to why he should join us, I cast about in my mind as to how we might hold him true—how it would be possible to prevent him from betraying us before we had set off on the journey, and therefore it was that by the time Seth had agreed to make one of what we[19] hoped would soon be a company of Minute Boys, I proposed that we start immediately, not waiting for more recruits lest opportunity for leaving the city be lost.

“But we have neither arms nor provisions,” Archie Gordon objected, and it must be remembered that immediately after the surrender of Charleston squads of red-coated soldiers had marched up this street and down that searching every house for weapons and ammunition, seizing upon everything of such nature as could be found.

“We had better go off unarmed and hungry, than not go at all,” I replied quickly, at the same time glancing toward Gabriel in the hope that he might read in my face somewhat of the distrust which was in my heart; but, honest even to a fault as he was, he failed to take the hint, and on the instant began arguing with me as to why we should delay our departure for at least eight and forty hours.

All the reasons for delay which Gabriel and Archie brought up were good, and not to be combated by me justly, for it seemed little less than folly for four lads to set off empty-handed, with no plausible pretext for such a journey, and take every risk of being arrested by the first of the king’s troops whom they might come across.

Gabriel claimed that by delaying no more than four and twenty hours we could enlist a full dozen lads, and in the meanwhile, perhaps, gain possession of arms, all of which I knew to be true.

Archie insisted that even though we were able to[20] join General Marion as we counted on, it would be a sorry reception we should receive, for, without weapons and lacking food, we might be an incumbrance rather than assistance to the cause.

I fancied that Seth, after listening to these well-founded arguments, and as it seemed to me turning them over fully in his mind, was unduly eager for delay, all of which I attributed to his desire to play us some trick which would prove our undoing.

Therefore did I insist all the more strongly that we set off without the delay of a single minute, urging the matter so vehemently that it was as if they grew weary with trying to convince me of my own folly, and agreed to start whenever I should say the word.

Then it was that I showed myself a fool beyond question, for, having gained the point, I should have carried out the plan fully even as I had shown myself eager to do; but at the last moment, when there was no refusal on the part of my comrades, and even Seth Hastings seemed willing to abide by the decision, I played the simple.

Having suddenly grown timid at the thought of setting off without so much as would serve to sustain life during four and twenty hours, I proposed that we separate to gather up such food as might be got at immediately, meeting an hour later at the place where Archie said the skiff was hidden.

I, who had been so suspicious, and the only one to distrust Seth, had in the very moment of persuading my comrades to do as I desired, given him every opportunity to play the traitor, for surely an[21] hour was as good as four and twenty if he was disposed to work us harm.

However, in my thick-headedness I failed to take heed of this fact, even though to this day it puzzles me to understand how I should have been such a blunderer, and believed that he, like the other members of the party, would spend all his time collecting so much in the way of provisions as might serve to save us from actual suffering.

Strange though it may seem, when I left that traitorous hound who agreed to be at the rendezvous sixty minutes later, there was no thought in my mind as to the possibility which I had allowed for treason, nor did the idea occur to me while I was hurrying here and there gathering such few articles as might be come at handily, for we were not overly well provided with provisions in those days after the occupation of the city by the British, when the red-coated soldiers had taken everything they could lay their hands on.

Left in charge of my home, not with any idea that he could protect it or prevent the king’s hirelings from working their will with the property, was an old slave, a negro who had been born on my grandfather’s plantation, and in whom I could trust as in my own people. To him I explained what it was my purpose to do, and after we two had gathered up such store of cooked food as I might carry conveniently, he thrust into my hands a pistol, explaining that my father had unintentionally left it behind when he set off so hurriedly for St. John’s Parish. The weapon was charged; but,[22] so old Simon assured me, there was neither powder nor ball in the house save so much as the steel barrel contained.

My home was at the corner of Elizabeth and Charlotte Streets facing Wragg Square, and when I set off with old Simon’s prayers that no harm might befall me ringing in my ears, my intention was to go down Chapel Street to Concord, and thence to Reid Street, where I could gain the water-front at the wharf which jutted out near Fort Washington.

It was only at the latter portion of the journey that danger to my plans might be anticipated, for there would I meet a strong British guard, who would or would not, as their fancy dictated, detain me, and the fancy of those royal troops at times was something to be greatly feared.

Only two persons did I meet during this distance, which was traversed by me as rapidly as possible, and I was by no means surprised because our people failed to be abroad, for in those dark days we who struggled against the king hid like rats in their holes, while our city was in possession of the enemy.

It was when I arrived within sight of the fort that my heart came into my throat, knowing that now was the critical moment, yet had I spent many days pondering over a plan, I could not have laid the time for departure more happily, for when I came near the fortification the noonday meal had just been portioned out to the soldiers, and they were so busily employed in ministering to their[23] swine-like appetites as to give no heed to a boy like me.

“It is a good omen,” I said to myself as I gained the water’s edge without having been challenged, and then again did I prove myself a simple, for he who trades upon the future, claiming that the past is any proof of that which is to come, has indeed lost his wits.

I arrived at the rendezvous triumphant and serene in mind, a good five minutes before the time appointed, but found Gabriel Marion already awaiting me. He looked dejected, as if matters had gone awry, and I asked laughingly, for at the moment my spirits were high:

“Have you failed to find anything that can be eaten, lad?” and he replied with a mournful shake of the head:

“I am too much of a stranger in the city to be able to burst into a house uninvited and demand provisions. It was useless for me to go to your home, which I have called mine since coming to Charleston, for I knew you would bring away from there everything which might be of benefit to us, and where could I have gone in the hope of getting that which we need? Therefore have I come empty-handed, save for so much of powder and lead as you see in this bag.”

He held toward me a small sack which might have contained a quart at the most, and was now more than one-third filled.

“That is a richer find than you believed, Gabriel,” I said cheerily, at the same time producing[24] the pistol old Simon had given me, “for we should be able to cut the bullets to fit these barrels, and although only a toy like this may not count for much against the king’s weapons, it is better than being empty-handed.”

Then I showed him my store of provisions, which, small though it was, might suffice not very hungry boys for two meals, and he seemed to think we were fairly well supplied.

“I cannot but believe, Rufus, that it is unwise thus to start off so suddenly and so unprepared,” he said, pulling aside the bushes which grew near a small creek making up from the river, disclosing to view the skiff of which Archie had spoken. “It would have been different if we knew that some important movement was near at hand, but thus to set off as if our friends needed us most urgently, giving no heed to what we might carry which would advantage them as well as ourselves, appears to me much like folly.”

Then it was I explained why I had argued for a hurried departure, repeating that the desire to get away was great owing to the distrust in my mind regarding Seth Hastings, and when I was come to an end, he, opening his eyes full upon me, exclaimed:

“And with all that in your heart you have given him an opportunity to play the traitor, if so be he is inclined that way!”

Again I repeat that not until this moment did I realize the fact, and then like a flood came upon me all the suspicions which had been mine a short[25] hour previous. Like the simple that I was, I would have given way to words of self-reproach and anger, but that he hushed me by laying his hand on my arm as he said:

“There is no good reason why you add to your folly, if folly it was, for such mischief as Seth may be willing to do has already been brought about. Yet, Rufus, I cannot agree with you that the lad would do such a thing. Why should he betray us who never did him any wrong? Why should he be willing to deliver into prison-ships boys like us, when it cannot benefit him one jot? It is no crime that, because of some weakness, he is unable to look a fellow squarely in the face. There are many of us who have mannerisms disagreeable to others, and yet we would feel aggrieved if they were set down, as you account Seth’s, like actual crimes.”

I began to grow ashamed of myself under Gabriel’s quiet and convincing reasoning, and just then Archie Gordon joined us, bearing on his shoulder a well-filled sack which told how successful he had been in his search for provisions.

“Huzza for Archie!” I cried, forgetting for the moment all that which had caused me uneasiness of mind. “How does it chance that you were allowed to come through the streets with such a burden?”

“It is neither more nor less than good fortune, William Rufus,” the lad replied laughingly, and then, as if it was necessary I prove myself a simple in every possible way on that day, I took offence at the name he had put upon me, spending many[26] a precious moment trying to convince him it might be dangerous sport to thus jest at what I had almost come to believe was my misfortune.

In this senseless manner I must have spent ten minutes or more, heeding not the fact that it was Archie who had brought us the provisions of which we stood sorely in need. No one can say how long my foolish tongue might have argued on the subject, had not Gabriel Marion, cool-headed lad that he was, insisted we could settle all disputes while paddling up the river, but Archie cried, as I ran toward the skiff with the intention of leaping in:

“We have yet to wait for Seth! It may be he is having better fortune than either of us, and we will set out on our journey as well equipped as if having spent a week in preparation.”

“There he comes now,” Gabriel said, pointing up Reid Street, and as he spoke he stepped aboard the skiff in readiness to push off.

I was so deeply occupied with the offence committed by Archie in calling me William Rufus, that I did not follow with my eyes the direction indicated by Gabriel’s outstretched finger, but leaped aboard the craft, having no more than cleared the gunwale when Archie cried in an accent of terror:

“He is coming; but pursued by four redcoats!”

Then it was that all the fear which had possessed me a short time previous returned with greater force, for instead of believing the boy was chased by the soldiers, I understood as clearly as if he himself had shouted to apprise us of the fact, that[27] his delay had been caused solely in order he might give information of that which we would do.

“The cowardly traitor!” I cried in a frenzy of rage. “He has played us false, and is bringing the bloody-backs down to take us prisoners!”

I was conscious, without raising my eyes to look, that Archie gave a quick glance over his shoulder, and then, dropping the precious sack of provisions, he leaped into the skiff, pushing it off at the same moment I gathered sufficient of wit to pick up a paddle in order to shove the light craft farther out into the current.

I question if either of us three lads realized that we were proving to the redcoats that our purpose was such as would not stand before the scrutiny of their officers—that we were really outlawing ourselves with but little hope of escape, when it would seem wiser if we stood boldly before them, for there was nothing in the bag nor on our persons which could give color to any story Seth Hastings might have told.

However, we had begun the flight, and neither questioned the wisdom of so doing, although we knew that before sixty seconds had passed the redcoats would fire upon us.

As has already been said, I seized one of the paddles immediately upon jumping aboard the skiff, and when Archie Gordon shoved off the frail craft he possessed himself of the blade which lay in the bow of the boat.

It is hardly necessary to say that neither of us needed urging, but began to send the light craft ahead at the fastest possible pace, and Gabriel Marion was not one whit behind us in making ready for the flight. When he would have joined his efforts to ours, however, thus making it necessary for us to work two paddles on one side with only one opposite them, I said in a tone no wise like a command, but rather as a suggestion:

“You had best give all your mind to steering, Gabriel, for we shall make better speed, Archie and I, if it is not necessary for us to look to the course.”

And he, mindful of others, as the dear lad ever was, whispered warningly:

“Bend as low to your work as possible, for we are like to have a shower of lead when the bloody-backs shall have come up from behind the bushes.”

[29]Desperate as our strait was, and knowing full well our very lives depended upon the efforts we made at that time, I ventured to look back over my shoulder in order to learn what that traitorous Seth Hastings might be doing, and at the same time to register a vow that if God spared my life I would some day repay him in full for this piece of wanton treachery.

The cur was hanging back behind the soldiers whom he had piloted, as if fearing we might make some attack and his precious skin thereby receive injury, while the redcoats were pushing on as eagerly as dogs do after a fox, unslinging their muskets as they came, and I whispered, to give greater emphasis to Gabriel’s warning:

“We are like to catch it hot precious soon now, for the bloody-backs are making ready to fire.”

“Save your breath, lad, save your breath! Whatsoever we may say now will not change the situation by a hair’s breadth, and verily are we needing both strength and wind if, peradventure, they fail to hit all three of us at the first volley.”

Never before, even while engaged in a friendly contest of skill, had I worked so desperately at the paddle. It was a stout ashen blade, yet it bent like a bow betwixt the resistance of the water and the pressure of my hands; at another time, when the stakes were less than life itself, I could not have hoped to curve the wood however slightly. I dare venture to say that Archie Gordon was putting forth every ounce of his strength even as I was of mine, for the lad had good pluck and a strong[30] arm, together with sufficient of temper to lend fictitious vigor at such a moment.

Save as I have already set down, our flight was made in silence, except for the music of the water as it rippled against the sides of the skiff, telling of the speed we were making, and although less than a minute had really elapsed since we pushed out into the current, it seemed to me that a full quarter of an hour must have sped before we heard the rattle of musketry and the singing of the bullets as they passed above our heads.

The king’s men overshot their mark, otherwise the aim was good, for had the weapons been depressed ever so little some of the missiles must have found their billets in our bodies.

Once the muskets had been discharged I felt a sense of wondrous relief, for now must we have a respite during such time as would be required for the enemy to recharge the weapons, and I laughed aloud even while expending every ounce of strength upon the paddle, whereat Gabriel said in a tone of irritation:

“The situation may not be so comical when next they fire,” and Archie replied in a tone that warmed my heart:

“They won’t shoot until after having reloaded, and we will crow while we have the opportunity.” Then, half-turning, he shouted over his shoulder to that miserable cur of a Seth Hastings, “If it so be we give your hounds the slip this time, Seth, my boy, I’ll undertake to come back to Charleston as soon as may be—surely before any other can take[31] your precious life, and repay the score which you have set for us to wipe out.”

No fellow could have resisted the temptation, however great the need of his laboring at the paddle, to look back in order to note what effect these words had upon the traitor, and, glancing at him an instant, I fancied I saw, even at such a distance, the gray pallor of fear come over his face. Certain it is he slackened pace, while the soldiers, instead of recharging their weapons, were making their way along the shore at full speed in chase of us, as if forgetting that it was upon their muskets and not their legs they must rely.

“Keep to your work, lads,” Gabriel whispered warningly. “The cost of bantering words may be too great, and we cannot afford to receive even the slightest wound if peradventure it can be avoided.”

He had the right to take command at that moment, for I question if he had turned his eyes ever so slightly, however great was the provocation; but kept his gaze straight up-stream that we might not deviate from the direct course by so much as a single inch. However, he knew full well that we could not fail of being eager to know whether our pursuers were gaining on us, and said after a brief pause:

“Work the paddles as you have begun, and we may give them the slip, even though the odds seem so great against us. I will tell you what they are about.”

Then, as we forced the light skiff ahead, literally[32] lifting her on the water, he called out whenever there was any change in the situation, thus picturing to us what we had no time to gaze at.

“The soldiers are still running, and have not stopped to reload their weapons—Seth Hastings has turned about as if afraid to join in the chase—I can see no craft along the shore, and yet it must be the redcoats know of one, else why do they continue on foot instead of recharging their muskets? When one of you fellows gets winded, change places with me, for this speed must not be slackened! Now the bloody-backs have halted and are reloading—one has taken aim! Crouch low, boys! Crouch low!”

Even as he spoke came the crackling of a weapon. A bullet struck the gunwale of the skiff within two inches of Archie’s hand, and I was dismayed because only a single gun had been fired. If they shot at us in a volley, the agony of anticipation would soon be over, whereas if each fired when he was ready we must be in continual apprehension of being hit.

“Look out now, another man is making ready!” Gabriel continued, and a second later came the report of his weapon, followed almost immediately by a third and a fourth, whereat our helmsman shouted as if victory was assured:

“Every bullet went wild! They are getting too much excited to be able to take aim! Keep the pace five minutes longer, and I dare venture to say we shall be out of range! Let me spell one of you now!”

“‘FIVE MINUTES LONGER AND WE SHALL BE OUT OF RANGE!’”

[33]“Stay where you are!” I shouted hoarsely. “We cannot afford to change places at such a time as this!”

I might go on telling of this chase until whosoever may read would be wearied with the repetition of words, and at the same time fail in attempting to portray all the feverish excitement which was ours during the short race, for it was as if I lived an hour in every moment. Although perhaps no more than ten minutes elapsed from the time we swung the skiff out into the current until the soldiers turned back, understanding it was folly to pursue us further, it seemed to me as if the day was already spent when Gabriel cried:

“Take it easy, lads; we are free from that squad at least, and if it so be the king has not in South Carolina men who can shoot with truer aim, then are we likely to live to a ripe old age, so far as danger from leaden missiles is concerned.”

It was high time the race had come to an end, for I was so nearly spent with the frantic efforts that it is a question whether I could have swung the paddle a dozen times more, even though knowing that my life depended upon the effort, and Archie Gordon was in no better physical condition than I, seeing which, Gabriel came amidships with his steering paddle, continuing to force the light craft ahead as he said cheerily:

“Lie back and take it easy, lads, for I can well do considerably more than stem this current,” and he made his words good, paddling with rare skill; it is no easy matter to keep a craft in the true direction[34] with but one blade, for the best of boatmen will send her yawing from side to side however much they may struggle to prevent it.

Archie and I sat in the bottom of the skiff limp as rags, now the excitement was over, breathing like broken-winded horses, but with a hymn of thanksgiving in our hearts that we had escaped from those who would have sent us to that which was worse than death itself—the prison-ships; and when it was possible for me to speak so that the words could be understood by those who heard, I said, as if believing myself the son of a prophet:

“Who shall say now that we lads may not be able to work benefit to the Cause, if at the very outset of our attempt we have been able to thwart the plan of a traitor while we ourselves were the same as unarmed and caught in a trap? Surely after arriving where we may be put on the footing of soldiers, it will be possible for us to do men’s work.”

Well was it for me that we mortals are denied the privilege of looking into the future, for if I had known that one of us three lads was to meet a treacherous death before we were well started in our work as “Minute Boys,” then might I have turned my back in dismay upon the task, and the aid which we were enabled to give the Cause would have been lacking at the very time when it was of greatest avail.

However, it is not for me to look forward while setting down these poor accounts of what we lads of South Carolina did, and although the grief is[35] as fresh in my heart now as on that terrible day, I must strive to repress it in order that that which I am trying to tell shall run on in proper sequence of events.

“We had best not crow too soon or too loudly,” Archie Gordon said grimly. “Although we may travel from here to Snow’s Island without further difficulty, and then be able to accomplish all we propose to do, there will be no good reason for congratulations until we have served out that cowardly traitor, who, without provocation, would have compassed our death.”

“If we are able to labor for the Cause it must be with a singleness of purpose,” Gabriel Marion said gravely, and one might have thought it was his elder brother who spoke, for the tone and words were not such as one would expect from a lad like him. “I grant you that Seth Hastings must receive due reward for what he has done; but so long as the king’s soldiers remain in South Carolina, so long must we put aside every thought save that of driving them from the soil! And now, since we have hardly but begun the long journey, and have our faces turned toward many a danger, instead of talking of revenge and boasting of our escape, let us do all we may toward carrying out this first portion of the plan Rufus has formed, as a first step toward which, one of you had better take a swing at the paddle, thus giving me a better show of sending the craft ahead at proper pace.”

“We will do better than that,” I cried, springing to my feet, ashamed of having remained idle[36] so long. “Neither Archie nor I need any more coddling,” and even as I spoke our brave little comrade dipped his paddle into the water once more, causing the skiff to dash swiftly forward again, heading as directly for our destination—Gabriel’s home—as the winding of the channel would permit.

And now, lest I set down too many words in the telling of what should be a short tale, I will make no attempt at recording that which we said or did while sailing up Cooper River, but content myself with putting down the fact that shortly after daybreak next morning we were come to the landing which led to the house where my parents, as I have already said, had found a refuge. Neither is it necessary for me to describe the greetings which were ours, nor how my heart swelled with pride and joy as I heard my father say, even while mother was pressing me to her bosom, as if I had but lately come from the very jaws of death:

“You and your companions have done well, Rufus, to take upon yourselves the work of men. In these times children must grow old rapidly that they may fill the place and do the work of those whom the king’s hirelings kill and maim.”

It was as if I felt my mother shudder when father spoke these words which told that he was in full accord with our purpose to become soldiers, but never a word of remonstrance did she utter. Looking back now, I can understand that she resolutely put far away the motherly love which would shelter and protect her child, allowing us three[37] lads to think she was only concerned in our welfare as she busied herself either in giving orders, or in performing the bitter work herself of preparing an outfit for us who were to depart as soon as might be.

Father told us what we already knew, that General Marion had gone to Snow’s Island, there to await the gathering of such as were ready to join him in the forlorn hope that we could beat back the invader even while his hands were upon our throat; and he advised that we remain where we were during four and twenty hours, saying in explanation of this advice, which might seem strange when one knew all the exigencies of the situation:

“It is hardly probable you can make all the necessary arrangements in a shorter time, and, besides, if you start from here fresh, the journey will be made in better time than if you set out already weary. I envy you, lads, the privilege of striking a blow in defence of the Carolinas. Would to God I might be able to play a man’s part, instead of remaining here like some helpless child!”

Then it was that Gabriel Marion deftly turned the conversation, noting that my father was sorely troubled because of his helplessness at a time when men were so sadly needed, and asked whether it was known if many had joined his brother, whereupon my father replied:

“I question if that be probable. Only Captain Horry and half a dozen of the neighbors set off with him. It may be that their numbers have been doubled by this time, but I doubt if their force is[38] much increased, for many there be in South Carolina, I am ashamed to say, who deem it wiser at this time to serve the king rather than their own country.”

Then we discussed as to which road it would be wisest to follow, and father held consultation with some of the older negroes who were familiar with the swamp and the country near about, until by nightfall we had not only mapped out a course, but were provided with an outfit such as was not to be despised in those days.

Old Peter, one of General Marion’s house-servants, had volunteered to act as our guide across the swamp, and we accepted the service readily, knowing that his master would be pleased at our bringing him, while at the same time he could save us many a needless mile in the journey.

It was his advice that we strike across the country to what was known as Charleston road, following that boldly up until we came to the highway leading to Indian Village, after which we would take to the woods for a short cut to Snow’s Island. By such a course we would come upon the different ferries, and thus have no trouble in crossing the streams unless, perchance, enemies were between us and our destination.

When one has fought and aided in the whipping of a king backed by a great nation, when one has stood a tiny atom in a ragged line of battle facing the on-coming of well-drilled, well-equipped European soldiers, and taken part in the crushing of that great machine into a panic-stricken mob, filling[39] the brain with the heat of that fever which comes in the excitement of battle, it is dull telling simply of the march and of the bivouac. Perhaps because I cannot yet be called a man I linger in the setting down of that which we did where renown was won, than as to how we made our peaceful way from one part of the country to another. Therefore, if I err in describing with too little detail such part of my life while I was numbered among the “Minute Boys of South Carolina,” as were dull or uneventful, the fault must be set down to my great desire to hurry forward into those scenes of moment.

It seems to me it should suffice if I say that on the morning after our arrival at Gabriel Marion’s home we departed. I need not say aught concerning that last embrace of my mother’s, or repeat father’s blessing, which he bestowed on us all.

Old Peter, carrying even more of our stores upon his aged back than was right, yet insisting upon bearing the greater portion of the burden, went on in advance as a guide, mounted on as good a horse as either of us lads rode. We had taken from General Marion’s plantation whatever might advantage us in the work, for anything he owned was at the service of his country. Thus it was we journeyed like soldiers, in the saddle, although we followed old Peter’s advice and carried all our belongings upon our backs, the negro arguing that at any moment we might come upon the enemy, and in case of being forced to take to the woods, where we could not use the horses, we[40] would not go empty-handed if preparations for flight had been made in advance.

It chafed me not a little that at the very outset we should be preparing for defeat, but my father had backed up old Peter, and Gabriel Marion stoutly insisted that as we proposed to be good soldiers, so should we obey the first commands given by those who had the right to dictate—meaning in this case my father, not old Peter.

We rode on merrily, our only care being the possible danger which might be in advance of us, never dreaming of anything to be feared in the rear; making the journey across country to the Charleston road before the day was more than half-spent, and halting at night less than a mile south of Gardine’s Ferry.

We spent no time in making camp, for none was needed. The horses were picketed in a small grove of cottonwood-trees, and we made a meal from the cooked provisions which we brought with us, after which every member of the party, even including the guide, lay down upon the ground wherever he pleased, giving no heed to keeping guard, because in our ignorance we lost sight of the possibility that the enemy might even at that moment be near at hand.

I question if it be not more wearying to spend a day in the saddle, to one who had not ridden for many months, than to walk during that length of time. For my part, I was thoroughly tired out when I threw myself upon the ground with no more care as to a bed than to use my saddle for a[41] pillow, and it was as if I had just composed myself to rest when I drifted off into slumber-land.

It seemed as if I had no more than closed my eyes in rest when I was awakened by being shaken violently, and on first returning to consciousness I heard old Peter whispering in my ear:

“Rouse up, Marse Randolph, I’se allowin’ dem British sojers am near by.”

I was awake on the instant, and then understood, from the absence of the moon, which had been shining when I fell asleep, that the night was more than half-gone. My comrades were already awake and on their feet, and Gabriel was saying in an anxious whisper as I joined them:

“It’s certain that a party of horsemen have gone on up the road, for I heard the trample of hoofs even as old Peter awakened me. It stands us in hand to know whether they be friend or foe.”

“Why should it concern us, if so be they travel rapidly enough to keep out of our way?” I asked like a simple, and Gabriel, true lad that he was, replied gently when he would have been warranted in speaking sharply:

“We must know what lies ahead of us, else are we like to ride into danger as do those who are blindfolded.”

“And how do you count on finding out?” I asked irritably, for it vexed me to thus be deprived of the rest I needed.

“One of us must follow until it is certain the strangers have not gone into camp, and at daybreak the others may bring up the horses. I am[42] ready to act as scout, and you fellows may lie down again with the understanding that one or the other stand guard during the remainder of the night. Instead of showing ourselves worthy to become soldiers, we have acted like children in making camp as we did, for the first duty should have been to station a sentinel.”

“You shall not go on alone,” I said, now ashamed because of having given heed only to my own desires, and Archie stoutly claimed the right to go with us.

We might have argued on this question until another day had come, had not Gabriel said hurriedly:

“Since neither of you will take advantage of the opportunity to sleep, we’ll all go, and if by daylight old Peter has heard nothing concerning us, he shall come up the road with the horses.”

As Gabriel said, so we did, and with our weapons charged, for we had left General Marion’s plantation fully equipped, we advanced swiftly, yet with due heed lest we overrun the quarry, leaving behind old Peter in a very disagreeable frame of mind, for his last words were a complaint that he was to be left in the rear when it was his duty to lead the way.

Not until we had travelled twenty minutes or more did I ask myself what was to be done in case we learned that the horsemen who had passed our camping-place were soldiers, and then I put the question to Gabriel.

“That shall be decided later,” he replied quietly,[43] and one would have fancied he had been bred to the trade of a soldier, so calm and collected was he at this time when we might be running our necks into a noose. “If the party is made up of bloody-backs we may be certain they have learned of General Marion’s whereabouts, and are hoping to entrap him, in which event we must make a détour in order to gain the advance, that we may warn those who are at Snow’s Island. In case it should be so that we might, without too much risk, make a capture, why, then, I say, let us take such prisoners as is in our power, and, on arriving at the rendezvous, have something to prove our ability to act the part of soldiers.”

It seemed to me that our business was to arrive at Snow’s Island as quickly as might be, without any regard for prisoners or picking up information; but plainly Gabriel was fitted to be the commander of our little party, and I held my peace, although stoutly rebelling at the idea of undertaking the trade of a soldier before having made other preparations than that of arming ourselves.

After this brief conversation we continued on in silence, but at a rapid pace, and soon came to know that those in advance were in no great haste to arrive at their destination, for we heard the hoof-beats of horses in the distance, and once more Gabriel said:

“We will follow without making any attempt to overtake them, during an hour or more, and then if there is no change we must close up, for[44] I am not minded to walk at their heels like a dog until daybreak.”

He had no more than ceased speaking when the sounds in the distance increased, and I came to a halt without waiting for orders; but Archie Gordon forced me on as he whispered:

“They are making camp, most likely, and now will we have the opportunity of finding out who they are, if so be we press on before they lie down.”

Gabriel spoke no word, but, taking each of us by the arm, plunged straight into the bushes for twenty yards or more, and then advanced cautiously until it was possible for us to hear the sound of voices.

Now we wormed our way amid the foliage like Indians, taking care lest the breaking of a dry twig beneath our feet should betray us, and before ten minutes had passed were where we could see a portion of the party we had been pursuing.

A small fire was already built, and around it were gathered four or five men clad in the uniform of the king’s soldiers, while here and there amid the bushes which grew close down to the side of the road, flitted dark figures not to be distinguished in the gloom, but which we knew were others of the enemy.

“What are they doing here?” Archie asked, as if he had forgotten we were on the road leading from Charleston, and Gabriel replied in a hoarse whisper:

“The chances are they have been sent to Snow’s Island, or else are in pursuit of us.”

“That last can hardly be true,” I said, again[45] showing how simple I was. “The British commander would not think it necessary to send out so large a party for three unarmed boys.”

“Ay, but suspecting, as they must if Seth Hastings told them my name, that we are bound for General Marion’s rendezvous, it would be only wise to send a sufficient force to capture all the rebels that might be found at the end of the journey.”

With this Gabriel crept yet nearer the camp-fire, and we followed him, moving ever so slowly, but halting not until having come within twenty feet or less, when it was possible to distinguish some of the words which were spoken.

As we lay there, hardly daring to breathe lest our presence should be betrayed, many of those who had been caring for the horses joined their comrades, and all appeared to be in the best of humor, but to our disappointment nothing was said regarding the purpose of their journey. Therefore we remained as much in the dark as before until suddenly there came between us and the glare of the camp-fire a figure which caused me to grip Gabriel’s arm fiercely even as Archie Gordon’s hand was pressing upon my shoulder as if he would bury his nails in my flesh.

Little wonder was it that we were filled with both surprise and alarm at the sight of this newcomer, for he was none other than that villainous renegade, Seth Hastings! It needed now no word from the men to tell us why they were here. That Seth had explained who Gabriel was, there could be no question, and because the cur was ignorant of the[46] fact that my mother and father had fled to General Marion’s plantation, he had supposed we were making directly for Snow’s Island.

That the whelp had offered his services as guide there was not the slightest doubt in my mind, and yet even at that time, when my anger and surprise were so great as to be nearly overwhelming, I asked myself again and again why it was that he, who had professed friendship for all three of us lads, should be doing what was in his power to compass our death. He was pursuing us like an avenger, and yet, rack my brain as I might, I could think of no act, however trifling, which he might have construed as against himself.

It was while I lay thus in a maze of perplexity, and perhaps fear, that Gabriel Marion pressed my hand significantly as he began to retrace his way through the bushes, and, as a matter of course, Archie and I followed, although it seemed to both of us at the time as if it were wiser to remain within sight of that villainous cur in the hope of putting a speedy end to his evil-doing.

Not until we were so far from the redcoats’ camp that there could be no danger our words might be overheard, however hot the discussion which was to ensue should become, did Gabriel halt, and I was eager to take advantage of this first opportunity of showing disapproval at our thus beating a retreat, as it were.

“It’s not for me to say what you and Archie shall do,” Gabriel began immediately he halted, and before I could so much as give words to the petulant thoughts in my mind. “As for myself, I see no good reason why we should linger near that encampment, and much cause for leaving as soon as possible.”

“Now you are answering a protest which has come into your own mind,” I cried, not a little irritated because he had taken the words out of my mouth, and he replied quietly:

“Ay, William Rufus, that is exactly what I am doing, for even though the night is none too light, I can see that you are disgruntled because I led you away from a place of danger. It needs not that you shall at all times proclaim your dissatisfaction[48] by words, for I can read much of what is in your mind by the movement of your body.”

“And you would not have read my thought so easily but for the fact that you yourself must have questioned whether it was fitting for lads who count on becoming soldiers, to turn tail at the first show of danger,” I replied hotly, and he irritated me yet further by saying, in what sounded to me like a tone of superiority:

“How would it have advantaged us in any way to lie hidden in front of yonder camp-fire watching the redcoats and that miserable cur, Seth Hastings? Was the picture so inviting that you would linger in order to gaze upon it? And when it was come daylight, if so be you loitered till then, what about the chance of your being discovered when old Peter brings up the horses, for I dare venture to say the negro will start at the first crack of dawn if we have not then returned?”

“How would it advantage us?” I cried hotly, allowing myself to be angered because in that time of danger he remembered to call me “William Rufus.” “By remaining there we might perchance have learned the destination of the troop, which seems necessary, since the force is travelling in the same direction we desire to go.”

“But we know as much as is needed,” Archie Gordon broke in, and I understood on the instant that he approved of Gabriel’s plan, whatever it might be. “That Seth Hastings is with the men tells beyond a doubt, at least so it seems to me, that they are heading for the rendezvous selected by[49] General Marion, in the hope of capturing not only him, but us lads as well.”

“Ay, Archie Gordon, there you have hit the nail squarely as I would have struck it,” Gabriel chimed in. “There was no reason for us to linger longer after having seen that traitorous cur, and good cause, as the matter presents itself to my mind, for us to make all speed with our backs turned toward the enemy.”

“To what end?” I asked impatiently, and he replied, clapping me on the shoulder in a friendly way such as made me ashamed of my petulance.

“To the end that we may push on while there is opportunity to make the détour, if so be old Peter agrees that it may be done between now and daylight. If we can arrive at Snow’s Island a few hours in advance of the British troops, and surely we should be able to do so with such horses as we have, then do we make doubly sure of receiving a hearty welcome, because the information we bring will be valuable to my brother.”

Even before he had finished the somewhat lengthy explanation I understood he was in the right, as indeed I ever found him to be, for Gabriel Marion was one of those rare lads who argues out a matter with himself before giving an opinion.

From that moment, until we were arrived at the place where old Peter was awaiting us patiently, no further arguments were indulged in, and I left to Gabriel the duty of acquainting the negro with all we had learned. It was evident that Peter had a far better idea of the situation than I had shown[50] to be mine when finding fault with Gabriel because of beating a retreat, for he appeared to recognize without discussion the necessity of circling around the enemy to gain an advance, and in order to accomplish such purpose was most particular in his inquiries regarding the location of the halting-place.

Gabriel felt positive the enemy was a full quarter of a mile to the southward of the ferry, and Peter, after taking ample time to consider the matter, but in the meanwhile saddling the horses that no precious moments might be lost, announced that it was possible to do the trick if we should leave the highway we were then on, striking across the country until having arrived at the Santee road, and then go down to the ferry; but he admitted that by so doing there was a grave possibility of our coming upon the enemy, if peradventure we had made any mistake as to the location of the encampment.

“To my mind, we are in duty bound to take the chances, however opposed we may personally be to such a plan,” Gabriel said, as he mounted his horse. “The information which we may be able to carry to Snow’s Island is so important that we are warranted in running any risk, for the life of one or of all of us, as compared with the advantage which can be gained for the Cause, is as nothing. Is it your mind that we shall push on without delay?”

He turned to me while asking this question, and there was no longer the slightest tinge of impatience in my tone as I replied:

[51]“It is for you to act the leader, Gabriel Marion, for surely there be none other in this party so well able to take command.”

Having said this, I also mounted, to show my readiness to set off without further delay, and old Peter needed no words to tell him that the moment had come when he was to act the part of guide in good truth. Therefore he set off in advance, striking directly into the undergrowth, where our horses, although finding some difficulty in making their way, managed to maintain a fairly good rate of speed during two hours, when we came upon the Santee road, much to my surprise, for I had fancied the distance to be greater.

Once upon the highway, Gabriel leaped from the saddle and began tearing the one blanket which he carried into strips, as if he had suddenly lost his senses.

“We must do what we may toward muffling the sound of the horses’ hoofs on the beaten road,” he said hurriedly, and in a twinkling all three of us began the same task, for there was no need of further explanation.

Within ten minutes, for we worked to disadvantage in the night, having no cord with which to tie the muffling on the horses’ feet, and then as fast as the steeds could be urged forward, for the woollen foot-covering crippled them to a certain extent, we rode toward the ferry, breathing quick with the excitement of the moment, because each step was bringing us nearer to a possible encounter, when the odds would be heavily against us.

[52]As nearly as I could judge, there were yet two hours of the night remaining, and it seemed to me as if we were in a fair way of accomplishing our purpose, when suddenly, and at the very moment while I was congratulating myself upon Gabriel’s foresight in hastening matters as he had, there came from the bushes on the side of the road fifty paces or more in advance of us, the thrilling cry:

“Halt, or we shall fire!”

Following this could be heard sounds of command, as if the unseen speaker was stationing a heavy force on either side of the road to enforce his demands.

On the instant my heart sank like lead, for I had no doubt but that we had come upon a considerable body of the enemy. It was reasonable to suppose that he who had spoken was the leader of the same party we had spied upon, and a similar thought must have been in Gabriel Marion’s mind, for I heard him cry half to himself:

“What stupids we were to so miscalculate the location of the halting-place!”

As a matter of course we obeyed the command on the instant, there being nothing else left to do, for our party of four would have shown themselves little less than idiots to have made any attempt at riding down so formidable a body as was apparently directly in advance of us, and flight seemed equally fruitless. As I pulled my horse to a standstill there came to my eyes a picture of the prison-ships as I had seen them lying at anchor in Charleston harbor, and I could have cried aloud[53] in grief because of this sudden end which was put to our undertaking.

When we were come to a halt, remaining in the saddles without making any show of unslinging the muskets which were strapped across our backs, the same voice we had first heard, cried out, and I fancied that there was a difference in the tone, as if the speaker was inclined to be friendly:

“Who are you, and what is your purpose here?”

Had I considered myself in command of our little force, I should have been such a simple to have made some effort toward concealing our identity, but not so with Gabriel Marion. He realized that the truth of whatsoever we might say could speedily be proven or disproven, and he replied readily:

“We are three lads escaped from the British at Charleston, who hope to arrive at a rendezvous appointed by an officer in the Continental Army. We have with us as guide an old negro, and are striving to gain the ferry before a force of the enemy encamped on the Charleston road near at hand shall arrive there.”

I thought of a verity that if there had been any possibility of our escaping the prison-ships, this answer had destroyed it, and friend though he was, I could have dealt Gabriel such a blow as would have sent him headlong from the saddle, because of what I believed was stupidity. Therefore it is that my astonishment may at least be faintly imagined, when I saw in the gloom of the night two small figures come hurriedly from out the screen[54] of bushes, advancing toward us as if overjoyed at the meeting, and I heard Archie Gordon cry half in delight, half in fear:

“Are you lads of South Carolina?”

“Ay, that we are,” the foremost of the strangers replied, hastening forward until he stood where he could look up into Gabriel Marion’s face. “We are making for the same rendezvous, if so be you have told us the truth.”

It did not require many seconds for me to gather my scattered senses, and when this was done I realized how crafty these two had been to thus halt us, giving the impression that they were strong in numbers, for I could now understand, from seeing none others, that they alone had made such a show of force.

Gabriel, bending over until he could see clearly the face of the lad who stood near him, said quietly, even as though he had been expecting such a meeting:

“This, if I mistake not, is one of the Marshall lads, whose home is near about Eutaw Springs?”

“And you are General Marion’s brother!” the boy cried in joyful surprise.

Then it was that we dismounted, and but a short time was needed in which to make each acquainted with the purpose of the other. These brave lads, having heard of the call sent out by General Marion, were hastening thus alone to obey the summons, so much of courage and a desire to aid the Cause was in their hearts. They had counted on taking with them four prisoners when they[55] heard us approach. It was a gallant deed, and I took somewhat of the credit to myself because they were South Carolinians.

When the Marshall boys—Edward and Joseph—had learned what it was our purpose to do, they proposed to join us as Minute Boys rather than enlist directly under General Marion’s command, and thus we lads, who had but a few seconds previous believed we were doomed to imprisonment, gained two recruits of such metal as was needed in the organization.

It can well be understood that we did not waste much time after the explanations had been made, but pressed forward toward the ferry once more, as soon as the new recruits had muffled the feet of their horses, and I said to Archie Gordon as we rode along side by side:

“If it were possible to come across four or five more like these lads who have just joined us, we might be in shape to gather in those who are guided by that traitorous cur,” and he replied, as if the idea gave him great pleasure:

“Ay, and it would be an adventure worth thinking about were we alone in this section of the country; but as it is, with our friends at Snow’s Island ignorant of what is going on near about, I am of the opinion that however strong we might grow by reason of additional recruits, there could be no fair excuse for making any such attempt.”

Now we had guides in plenty, for the Marshall boys were better acquainted with this section of the country than was Peter, and instead of making for[56] the ferry, where there was even chance we might find some of the troopers posted on guard, they proposed that we make a short cut to a point on the river fully half a mile above Gardine’s Ferry, where they believed we could swim the horses across.

The only danger in such a crossing was that we would be obliged to travel over a considerable extent of swamp, but this both they and old Peter believed would be more advisable than taking the chances of meeting the enemy at the ferry.

As had been agreed upon, so we did, and although more than once after gaining the opposite bank of the stream did it seem possible the horses would be mired, we were so far successful that when the first glimpse of the coming day appeared in the eastern sky we were on the highway, riding swiftly toward that crossing of the Black River known as Potato Ferry.

From this moment it was as if all the difficulties had been removed from our path. When the sun set we were at Britain’s Ferry, on the bank of the Great Pedee River, and Snow’s Island was barely four miles away; but, owing to the darkness, Gabriel believed we were warranted in remaining where we were rather than in attempting to go down the stream, for daylight was needed in crossing to the rendezvous.

This time when we made camp we took hourly turns of standing watch, and when another day was come, after partaking of a hurried meal, we set out, arriving at our destination not without considerable[57] difficulty, owing to the fact that none of us knew the exact trail which would give us good footing, but yet suffering no more of hardships than might have been expected, and certainly none worth setting down here.

The day was yet young when finally we stood before General Marion to receive from him the heartiest greeting lads could ask for, and even old Peter came in for his full share.

The general had at this time no more than twenty men, well armed, but, as we afterward learned, with only a scanty store of provisions, and all this company gathered around us to learn the latest news from Charleston. Little did they dream that our arrival would be a signal for the first attack on the enemy since the fall of the city.

They were plunged in deepest grief when told of the wholesale arrests made by the British commander, Sir Henry Clinton, and each had some question to ask regarding the bearing of this or of that citizen while being marched through the streets of Charleston to where boats were taken for the prison-ships.

Gabriel, acting as our spokesman, as was indeed his right, since we two tacitly agreed to recognize him as leader, gave all the information possible, and not until this little band of patriots had finished with their questioning did he speak of our adventure on the Charleston road. Then, as may be fancied, every member of the company was wrought up to the highest pitch of excitement, for if the word which we brought was true, then could[58] they see in the near future an opportunity for striking a blow in retaliation.

General Marion questioned us particularly concerning the number of the men, and as to whether the company was made up of Tories or British soldiers, and to this question we could give no satisfactory reply. True it is that we had seen by the light of the camp-fire none save those who wore the red uniform, but we knew full well there were others hidden from our view by the bushes, therefore it was well within the range of possibility that the soldiers had in their company many Tories.

That which puzzled our friends was the same question as we had asked ourselves many times: Why Seth Hastings had thus suddenly and openly shown himself an enemy to the Cause, and why was he so eager that we lads be made prisoners?

It was a question which no one could answer satisfactorily, and General Marion put an end to our speculations by saying in a tone of pleasure:

“Before to-morrow morning, if indeed you are not mistaken as to the destination of the company, we will have in our keeping this Seth Hastings who has shown himself such a violent friend of the king’s, and I doubt not that you lads may be able to get the desired information from him.”

“Will you make an attack upon the company?” Gabriel asked quickly and eagerly.

“I think we shall, lad, and regardless of their numbers, else why have we gathered here?”

“But they are in reasonably large force,” I ventured[59] to say, and the young general answered stoutly: