KING ALFRED’S JEWEL

Title: Alfred the Great

containing chapters on his life and times

Editor: Alfred Bowker

Contributor: Walter Besant

Frederic Harrison

Sir Clements R. Markham

Charles Oman

Release date: July 22, 2025 [eBook #76551]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Adam & Charles Black, 1899

Credits: MWS and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

[i]

[ii]

KING ALFRED’S JEWEL

BRITAIN IN TIME OF ALFRED

[iii]

Alfred the Great

CONTAINING

Chapters on his Life and Times

BY

MR. FREDERIC HARRISON, THE LORD BISHOP OF BRISTOL

PROFESSOR CHARLES OMAN, SIR CLEMENTS MARKHAM

THE REV. PROFESSOR EARLE, SIR FREDERICK POLLOCK

AND THE REV. W. J. LOFTIE; ALSO CONTAINING

AN INTRODUCTION BY SIR WALTER BESANT

AND A POEM BY THE POET LAUREATE

EDITED, WITH PREFACE, BY

ALFRED BOWKER

MAYOR OF WINCHESTER

1897-98

‘This will I say—that I have sought to live worthily the while I lived,

and after my life to leave to the men that come after me

a remembering of me in good works.’

LONDON

ADAM & CHARLES BLACK

1899

[iv]

[v]

TO

Her Majesty the Queen

BY GRACIOUS PERMISSION

THIS VOLUME

IS

DEDICATED

[vi]

[vii]

[viii]

[ix]

Now that we are fast approaching the one thousandth anniversary of the death of our greatest sovereign of the past—“King Alfred,” whom it is the laudable desire of many of Her Majesty’s subjects and others to commemorate fittingly—this book, which bears the king’s name, and is written in honour of the king, and is intended to present what is known of the king’s achievements and his claim on the gratitude and love of the English-speaking race, would hardly seem to demand a preface.

To some minds, however, this small book, if it appeared without a word of preface, might seem insufficiently comprehensive; it may be well, therefore, to explain shortly the motive for its production. The International Committee organising this Commemoration have considered it very advisable that a publication should be issued with a view to diffusing, as widely as possible, public knowledge of the king’s life and work. This being the sole object, it became essential that the [x]book should not be costly, but within the reach of all. Therefore it was also necessary to restrict its scope; numerous subjects and possible illustrations of interest have been left for a full and complete biography of the great king.

At the same time, it is hoped that the chapters which follow will enable the general reader to create in his own mind a figure, a mind, a history, worthy of the king and equal to the occasion. The general introduction is, in substance, the address delivered in the Guildhall of Winchester by Sir Walter Besant at the first public meeting held to lay the foundation stone of this Commemoration. The names of those who have contributed chapters are a guarantee that the reader is in good hands; the subjects of these chapters show a fairly complete division of the various lines in which Alfred achieved greatness.

Whilst taking this opportunity of placing on record my very cordial thanks to the contributors for their gifts, especially to Sir Walter Besant, and to the Lord Bishop of Winchester for kindly advice, I feel that my thanks alone would indeed be a poor requite; but our readers, of whatever station, whether high or low, by assisting to the best of their ability in the forthcoming Commemoration, which is veritably that of one thousand years of many of our institutions, of our government, and our national existence, will be [xi]expressing gratitude and thanks more acceptable than words of mine can convey.

It may seem strange to some readers that by chance no full account is given of Asser’s anecdote of the scene between the king and the herdswoman in the Isle of Athelney, where he took refuge, but as the story is known to all, its omission may perhaps be pardoned; it is certainly not due to any lack of interest in the story, which seems so strikingly to show that at times, maybe when the king was resting or sitting by the fire mending his bows and weapons, he would become absorbed in the one thought foremost in his mind—that of the welfare of his country and people, then sorely harassed and oppressed by the Danes, and so neglected the homely duty that was present.

I have, further, to draw the reader’s attention to the circular at the end of the book, but it is not necessary for me to point out the advisability, or to detail the many praiseworthy reasons, for the erection of memorials to illustrious dead, stimulating and encouraging as they are to succeeding generations, engendering patriotic sentiments, and recalling to us the history of the past by which knowledge is weighed and gained, and that from the lesson we learn almost unwittingly to shape and guide our future steps.

In conclusion, I would express a hope that the following chapters will be read far and wide with [xii]as much pleasure and profit as they have been by myself, and that through their agency, and out of public subscription, we may soon see rising in the heart of the capital of Wessex, worthy not of England alone, but of the English-speaking race, a memorial to one who may rightly be regarded as one of the principal founders of the English nation and its language, a pioneer of improvement, liberty, learning and education, and who, though a thousand years have sped, still forms a mighty beacon of all the highest aims and the noblest aspirations that may dominate the hearts of men.

A. B.

1st May 1899.

| PAGE | |

| Introduction, by Sir Walter Besant, F.S.A. | 1 |

| Alfred as King, by Frederic Harrison, Hon. Fellow of Wadham College, Oxford | 39 |

| Alfred as a Religious Man and an Educationalist, by the Right Rev. the Lord Bishop of Bristol | 69 |

| Alfred as a Warrior, by Charles Oman, M.A., F.S.A., Fellow of All Souls, Oxford | 115 |

| Alfred as a Geographer, by Sir Clements Markham, K.C.B., President of the Royal Geographical Society | 149 |

| Alfred as a Writer, by Rev. John Earle, Professor of Anglo-Saxon, Oxford | 169 |

| English Law before the Norman Conquest, by Sir Frederick Pollock, Bart., Corpus Professor of Jurisprudence | 207 |

| Alfred and the Arts, by Rev. W. J. Loftie, F.S.A. | 241 |

| INDEX | 259 |

[1]

In writing an Introduction to the chapters which follow, I shall not be expected to contribute any new facts to the life of the great king. As for any new facts, the time has long gone by when anything new could be discovered concerning the great king of whom I have to speak. The tale of Alfred is a twice-told tale: but it is a tale that should be always fresh and new, because at every point it concerns every successive generation of English-speaking people. Happily it is not the whole life of Alfred that we have to consider in this place: it is the example of that life: the things that Alfred invented and achieved during that short life for his own generation; things which have lasted to our own day, and still bear fruit and golden sheaves. I should like to proceed at once to those achievements, but it is absolutely necessary first that we should understand some of the conditions of the time: the troubles and the struggles: the overthrow and ruin with which Alfred’s reign began: [2]the apparent hopelessness of the situation changed by the unexpected uprising of one man: and the rapid development of this man as Captain, Conqueror, Administrator, and Teacher. This done, we shall be in a position to receive the King as an example that should abide with the people still, and should still continue to shape the lives and inspire the minds of his race.

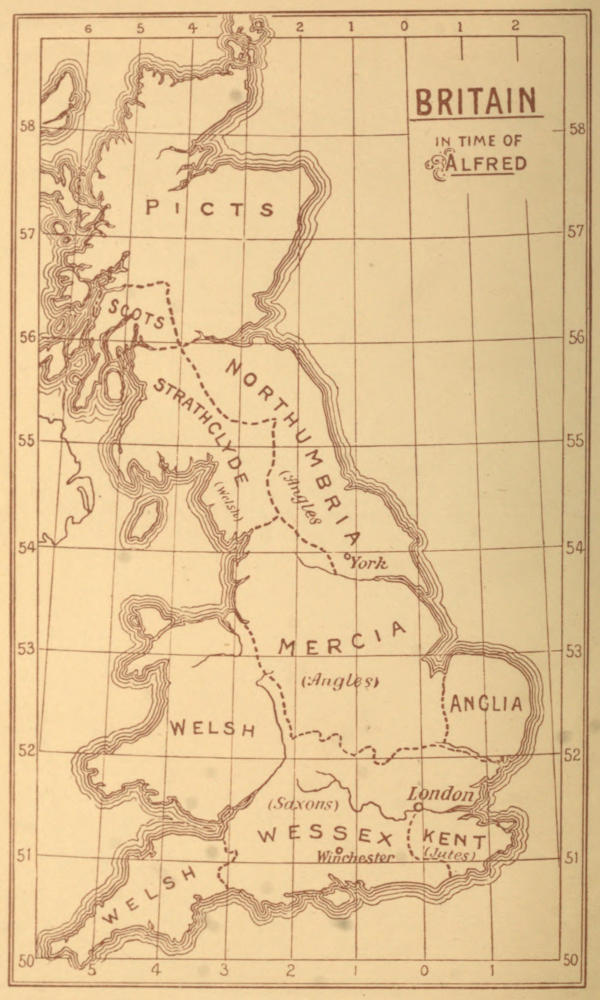

In order to prevent long explanations, and to illustrate at the outset some of the conditions of England when Alfred was born into the world, I have caused a small map to be drawn. You will see that the island is divided up into many nations. There is first the Kingdom of Kent, founded by the Jutes, who never extended themselves: then the Kingdom of Wessex or of the West Saxons, who by this time had absorbed the Kingdom of Essex or East Saxons, and of Sussex or South Saxons. The modern counties of Norfolk and Suffolk form the Kingdom of East Anglia—founded by Angles, a people closely allied to Jutes and Saxons: the middle of England is Mercia, the Kingdom of the March or boundary—the Mercians were also Angles. On the north is the Kingdom of Northumbria, also founded by Angles. The West of England is wholly occupied by Strathclyde, Wales, and Cornwall, all kingdoms of the Britons or Welsh who remained still unconquered. In Scotland the Highlands were occupied by the [3]Picts, and a part of the west was peopled by the Scots who crossed over from Ireland. The Angles therefore occupied the middle, the north, and the east; they gave their own name to the whole country—Angle-land or England: the Saxons occupied the south, with the exception of Kent: the Welsh still held nearly the whole of the west: but their territories were separated and cut into three parts. If we look backwards and forwards in history during these centuries we shall find the map of our island constantly changing. But still we may take this map fairly to represent the country as it was in the time of Alfred—eight distinct nations in it: three of them composed of Angles, who were not on that account allies: one containing Jutes: one of Saxons: three of Welsh. These so-called nations shifted their borders continually: they fought their neighbours: they split up and fought each other: there was no coherence or stability among them: some of them adopted Christianity and then relapsed: some of them remained pagans.

These were the tribes or nations in the land.

Let us next consider what manner of men it was over whom Alfred was called upon to rule. In order to get at this knowledge we must inquire of their religion, their laws, and their customs. As for their religion, before they became Christians, it was a fierce and cruel religion, although it was full [4]of imagination, as was to be expected of a people in whose minds the noblest poetry was slumbering. There were Gods who created and invented: Gods who gave life and inspired love: Gods who sent the thunder and the storm: Gods who brought the spring and the sunshine, the fruit, and the harvest. There were evil Gods—the Gods of Death, who killed men: the Gods of Disease, who tortured men: the Gods of the Sea and the River, who drowned men: the Gods of Battle, who struck men with cowardice, and weighed down their hands so that they could not strike. There were humbler deities—spirits of the stream, the woods, and the hills—for the most part hostile to men and malignant, because in certain stages of civilisation the unknown forces of Nature present themselves as personal deities who are always hostile to man—according to the Greek legend, for instance, he who met the great God Pan face to face fell down dead. They believed in raising spirits and in spectres, much as some of us do now: they believed in witches and in witchcraft: in magic and in charms: in love philtres: in divination: in lucky days. In a word, the Anglo-Saxon was full of the superstitions which belonged to his age.

There was, however—I venture to read between the lines—one saving clause. The Anglo-Saxon was not only afraid of the unknown, which caused him to invent malignant deities, but in his mind [5]the God of Creation was stronger than the God of Destruction. There is hope for a people while that belief survives. Long after he became a Christian the Saxon continued to retain his old beliefs under other names: he saw and conversed in imagination with the old deities whom he had forsaken: they spoke to him in the thunder: he saw their forms in the flying cloud, in the splendour of the sunset: he heard their whispers in the woods: they came to him in dreams. Religion, to the Anglo-Saxon, was a thing more real, more present, than it has ever been to any people except the Russian and the Jew. This is perhaps the most important point to be observed in the character of Alfred’s people. They were profoundly influenced by their religion. In the eighth century, when Christianity was spread over the south and the middle of the country, all classes began to long after the religious life as they understood it. Kings and Queens—there were ten Kings and eleven Queens—Princes and Princesses, nobles and freemen—all who could be received, crowded into the monasteries: they were eager for the life of meditation and of prayer: they made the cloisters rich: they filled the monastic houses with gold and silver plate and rich treasure. When the Danish invasion began, the Danes very soon found out that it was the monastery, and not the town, which they should sack: and at the same [6]time the people found out that the full monastery meant the shrunken army. It has been said that the Anglo-Saxon never changes. In this respect at least he has never changed. Through all the changes and chances of a thousand years, wherever he has penetrated, wherever he has settled, he has carried with him the same earnestness and the same reality of religion.

We must also note, next to the earnestness of his religious belief, the freedom of his institutions. The liberties of our race, which have become to us like the very air we breathe, so that we are not even conscious of them, were not wrested by the people from reluctant kings. These liberties had always been with them from the prehistoric times when the family was the unit, and when custom was the only kind of law. Among their primitive customs were the first rude forms of their free institutions. From the Forests of North Germany, from the mouth of the Elbe, not from any king, came the right of free meeting: the right of free speech: the right of free thought: the right of free work.

Next, as a people the Saxons were also fond of music, singing, poetry: the quicker witted Norman despised the Saxon as slow of understanding. Perhaps: but the Saxon proved himself in the long-run far more capable of enthusiasm, of loyalty, of patriotism, of sacrifice, of all those [7]actions and emotions which spring from the imagination and produce forces united and irresistible. Remember that the whole of our literature is Anglo-Saxon; none of it is Norman. There is not one great Norman poet. No Norman literature was produced on this our Anglo-Saxon soil.

The next characteristic of this people is less picturesque. They were obstinate. Now obstinacy, if we think of it, is one of the most useful and valuable qualities that can be planted in the breast of man. It has many names: it is called by its friends firmness: under any name it is the tenacious man who wins in the long-run.

They were essentially an outdoor people: they loved all manner of outdoor sports: all classes were hunters, hawkers, fishers, trappers: the country was full of creatures to hunt: there were in the forests wolves, bears, wild bulls, and stags: they loved the free air of the open hillside: and they hated towns. It was many years after their settlement in this country before they ceased to feel the old terror of the magic which, they thought, could be practised within the walls of a city.

As regards the Anglo-Saxon women, it is pleasant to learn that the very same virtues which are now conspicuous in our own women of the present day were conspicuous in them. She was, as Thomas Wright says, “An attentive housewife: a tender [8]companion: the comforter and consoler of her husband and her family: the virtuous and noble matron.” In all ranks, from the queen to the farmer’s wife, we find the lady of the household attending to her household duties. They were more learned than the men: they could recite and sing the poetry of their native bards: they were skilful in playing the harp: and in embroidery and needlework of all kinds the work of the Anglo-Saxon ladies was in demand all over Western Europe.

The Anglo-Saxon, therefore, had many virtues. He had also, we must confess, his faults, which were conspicuous as well as numerous. He was slothful of mind: he was always ready to sink back to the ancient seclusion of the village and the forest: he was conservative, and thought the old ways would last for ever: he was a great drinker—in drinking, except among the Danes, he had no equal: he would drink for days together almost without stopping: even the priests did not escape the universal vice: they were admonished by the bishops not to say mass unless they were sober: his hospitality consisted chiefly in making the guests drunk. The Saxons, again, have been charged with cruelty—certainly very terrible things were done, but we cannot expect a people to be before their age: it was a cruel age. Frenchman, Norman, Dane, Saxon: all [9]alike were cruel in their punishments: but these things belong to the time. Let us acquit the people of Wessex of more than their share of the average cruelty. The stories told of the Danes, for example, are almost incredible, whether for the cruelty of the torture, or for the endurance of the victim.

When we say that the Anglo-Saxon was a free man, and governed by free laws, we must not imagine him to be a Republican of the nineteenth century. Nor must we conclude that the Anglo-Saxon was a democrat, as we understand democracy. He had his king over him, to begin with: and the king was not elected by the people from among themselves, as the President of a Republic; he succeeded because he belonged to the Royal blood. He was even allowed, long after they were Christians, to be descended from the Gods: the people consented to his succession, but they did not elect him. As king he had very large powers, and these were undefined: men had not yet begun to question the Royal Prerogative: above all, he was their captain: he led the army: he fought with the army.

In a word, the Anglo-Saxon of the ninth century was in essentials very much like his descendant of the present day. He was religious: he was a lover of order: he was a good fighting man: he was fond of outdoor sports and occupations: he was [10]tenacious of his freedom: he was imaginative, poetical, and dreamy: he was fond of music: he was still full of the old traditions and superstitions which ruled his life, long after he had become a Christian. This is a general summary of his character. In one virtue he was as yet wanting. We must not expect in him what we call the national and patriotic sentiment. The man of Wessex was the enemy of the man of Mercia: the north stood aloof from the south: there was no England or Britain: there was only a large island divided among eight nations, or ten nations, or five nations, according to the year of the Lord: some of them spoke the same tongue: all the Angles, Jutes, and Saxons had similar institutions: nevertheless they were enemies. You remember, two hundred years later on, how London accepted the rule, first, of Cnut the Dane: and, next, of William the Norman. Both of them were what we should call foreigners. There was no such feeling then. To the Londoner it mattered little whether his king was Mercian, Northumbrian, Saxon, Jute, Dane, or Norman. London received kings from all these people. There was not yet any feeling existing for the country as a whole. It was part of the work of Alfred, unseen and unsuspected, to make it possible to weld the different nations into one: to create little by little the love of country in place of the old loyalty to the tribe.

[11]

Let us concede that Alfred fought, not for England, but for Wessex. In doing so, it is true, he fought for all England, but perhaps without his knowledge. In the same way David fought first for his own little country—for Judea—and made it possible for his successor to create one great country, of which Judea was the centre.

I have lingered a long time over the character of the people whom Alfred was called upon to rule. Without this knowledge it is impossible to understand what the king did and why he did it, and in what respects his work is so truly remarkable and wonderful. Let us now pass on to the history itself, and first, naturally, to the invasions of the Danes.

It was in the year 832—seventeen years before the birth of Alfred—that the Danes first made their appearance on these shores. Their incursions began and continued exactly in the same way as those of the Saxons themselves 400 years before. They came over in their ships: they found the north seas without defence: they found no fleets guarding the island from the pirates, as of old: the people, ready to believe that things would go on for ever unaltered, had actually abandoned their ships; had lost the art of ship-building; and were no longer accustomed to the sea. The Danish fleet swooped down upon the coast: harried the country: murdered the people: sacked the [12]monasteries and the churches, and went away again. They found the coast, like the seas, defenceless: the monastic houses had drained the country of the fighting nobles: the warlike spirit of the people was wasting itself in petty tribal wars. The Danes, until the old spirit returned, were far more than a match for the Saxons. They appeared suddenly, without warning, now on the coast of Kent: now on that of Dorsetshire: now at the mouth of the Parret, in Somerset: now up the Thames: now at Southampton: they came in fleets of a hundred and fifty ships, carrying each sixty or seventy warriors: an army greater than anything that could be hastily got together against them: by the time that an army was collected the Danes had gone, leaving ruined churches: villages destroyed by fire: monasteries pillaged of their treasures: and murdered monks lying beside the scattered relics, which could not protect them. The Danes, their foray over, had gone off, bearing their treasures with them, to their own country. Next year they landed again: but on another part of the island.

This yearly invasion of the Danes lasted for twenty years. They always made straight for the nearest monasteries, which they sacked: there were not many towns in Saxon England; but there were some—Canterbury, London, Southampton, York—they attacked these, seized, plundered, and [13]left them in ruins. For twenty years they came every year: sometimes we hear of a victory over them: but still they came again: there was never a victory so decisive as to keep them from returning in ever-increasing numbers. Then they began to stay in the country: they left off going home in the autumn: they established themselves in winter quarters, first on Sheppey Island, then on the Isle of Thanet: then in Norfolk. Then they went farther afield. In a word, they overran and conquered East Anglia: then the Kingdom of Northumbria: then that of Mercia: then the united Kingdoms of Wessex and Kent. It was at this crisis, when all the power of the Danes was brought to bear against Wessex and Kent, Alfred succeeded to the throne. His father and his four brothers, kings one after the other, had spent their lives in vainly beating back hordes of the Danes, who returned year after year. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle makes the best of occasional victories, but the fact remains that every year the invaders became stronger and the defenders became weaker. The King of Mercia at last gave up the struggle and went to Rome, to adopt the religious life, leaving his wife behind. Alfred might have done the same thing, and it would not have been imputed unto him for cowardice, but for godliness.

Happily for England he did not. The Danes [14]had seized Chippenham, in Wiltshire, and made that place their stronghold and headquarters. From Chippenham they sent out their light troops, moving rapidly here and there, devastating and murdering. For nine long years, growing every year weaker, Alfred fought them: in one year he fought nine battles. At the end of that time he found himself deserted, save for a few faithful followers: his country prostrate: everything in the hands of the enemy: his cause lost, and apparently no loop-hole or glimmer of hope left of recovery. No darker or more gloomy time ever fell upon this country. Everywhere the churches and the monasteries were pillaged and destroyed. All those—bishops, priests, monks, and nuns—who could get away had fled, carrying with them such of their treasures as they could convey. The towns were in ruins: the farms were deserted: the people had lost hope and heart: they bowed their heads and entered into slavery: their religion was destroyed with the flight or the murder of their priests. Their arts, their learning, their civilisation, all that they had once possessed, were destroyed in those nine years’ warfare: destroyed and gone—it seemed for ever. And the king, with his wife and her sister, and his children, and the few who still remained with him, had taken refuge on a little hill rising out of a broad marsh, whither the enemy could not follow him.

[15]

In the after years Alfred was fond of talking over this time of desolation: he would recall the visions that came to him, and not only to him but to his wife as well: they both saw visions of consolation and of promise. Saint Cuthbert himself stood beside his bed and comforted him with promise of victory and honour. We can very well believe the vision. To Alfred: to his wife: the aid of the Saints was a thing to be invoked and to be looked for. Did they not pray daily for the help of the Saints? And who should aid the Saxons in their trouble but their greatest Saint—Cuthbert himself? In the sleep or the waking of night, what more natural than that Alfred should imagine that he saw and spoke with the Saint himself? To those who drive or walk across the dreary level of Sedgemoor, now drained by its deep dykes, and dotted with its village churches, there rises on the right hand the low hill of Athelney. One can realise, looking upon this hill across the flat land, which was once covered with bogs and quagmires, and reeds bending before the wind, how complete was the defeat of the king: how complete the victory of the Danes; which should drive Alfred to seek such a refuge. The Danish Conquest, like the Norman Conquest two hundred years later, seemed an achievement accomplished. No further opposition: no one asked what had become of Alfred—he had run away to Rome: [16]he had gone into a monastery, perhaps: everywhere the Danes all over the country reported submission and the acceptance of their rule. And the old gods had come back again, Woden, and Thor, and Friga, and the rest: and again the fires flamed upon the high places, and the children were passed through them, and all the Christian saints had fled.

Alfred remained inactive during the whole long winter. It was the rule of the old Kriegs Spiel, the war game of that time, that the armies should not go forth to fight in winter. The men would have refused to go out in the cold season. In fact, they could not. The country was covered with uncleared forests: the roads in winter were deep tracks of mud: it was impossible for the men to sleep on the cold, wet ground. The delay suited Alfred: he wanted time to organise a rising in force: he sent messengers to the Somersetshire people, among whom, in winter quarters, were lying few or none of the Danish conquerors: he bade them make ready for the spring: he ordered those of the thanes who were still left to come to him at Athelney: and in May, when the spring arrived, Alfred appeared once more as one risen from the dead: once more he raised the Wessex standard of the Golden Dragon: once more the people, taking renewed courage, flocked together: as he marched along [17]they joined him, the fugitives from the woods and those who had been made slaves in their own farms, and swelled his force.

What follows is like a dream. Or it is like the uprising of the French under Joan of Arc. There had been nine years of continuous defeat. The people had lost heart: they had apparently given in. Yet, on the reappearance of their king, they sprang to arms once more: they followed him with one consent, and on the first encounter with the Danes they inflicted upon them a defeat so crushing that they never rallied again. In one battle, on one field, the country was recovered. In a single fortnight after this battle the Danes were turned out of Wessex. Alfred had recovered the whole of his own country, and acquired in addition a large part of Mercia.

It is significant to read that the Danish chieftain became a Christian, and was baptized. Do you suppose that he weighed the arguments and listened to the history and the doctrines of the new religion? Not at all. He perceived—this logical pagan—that King Alfred’s Gods had shown their superiority over his own in a manner so unexpected, so amazing, and so decisive, that he hesitated no longer. He acknowledged that superiority; he was baptized, and he never afterwards relapsed.

Alfred had got back his kingdom. It remained [18]for him to recover it in a fuller and a larger sense: to restore its former prosperity and its ancient strength.

He began by recognising the separate rights of the Mercians. He would not call himself King of Mercia. He placed his son-in-law Ethelred as Earl of Mercia, and because London was at that time considered a Mercian city, Ethelred took up his residence there as soon as the Danes had gone out. The condition of London was as desolate and as ruinous as that of the whole country. The walls were falling down: there was no trade: there were no ships in the river: no merchandise on the wharves: there were no people in the streets, save the Danish soldiers and the slaves who worked for them. Alfred restored the walls: rebuilt the gates: brought back trade and merchants: repaired the Bridge, and made London once more the most important city of his kingdom: its strongest defence: its most valuable possession. This was, in fact, the third foundation of London. If Alfred had failed to understand the importance of London—that great port, happily placed, not on the coast open to attack, but a long way up a tidal river, in the very heart of the country—a place easy of access from every part of the kingdom—a port convenient for every kind of trade, whether from the Baltic or the Mediterranean—the whole of the commercial [19]history of England would have been changed, the island might have remained what it had been for centuries before the Roman Conquest, a place which exported iron, tin, skins, wool, and slaves, and imported for the most part weapons to kill each other with.

Alfred gave us London. The lesson of ten years’ fighting taught Alfred what the Saxons had never before understood, the value of walled cities in the case of invasion. He saw—he was the first to perceive—how superior numbers may be rendered of no avail when they fling themselves against strong walls. The next Danish invaders found themselves stopped on their way up the Thames by a city fortified by a strong wall which the enemy could neither knock down nor climb over: and manned by citizens made doubly courageous by the safety and the strength of their ramparts. Six separate sieges were endured by London during the second invasion of the Danes: six separate times the enemy had to raise the siege and to go elsewhere, leaving London unconquered. Other walled towns were added—Winchester, York, Exeter, and Canterbury—but the first was London, whose fallen Roman wall, of which only the hard core of cement remained, Alfred rebuilt and faced again with stone.

Alfred, I repeat, gave us London. This was a great service which he rendered to the safety of [20]the country. But there was still a greater service. The Saxon had quite forgotten the seamanship in which he had formerly known no master and no equal. Alfred saw that for the sake of safety there must be a first line of defence before the coast could be reached. England could only be invaded in ships, and by those who had the command of the seas. Therefore, he created a navy: he built ships longer, heavier, swifter than those of the Danes, and he sent these ships out to meet the Danes on what they supposed to be their own element. They went out: they met the Danes: they defeated them: and before long the Saxons had afloat a fleet of a hundred ships to hold the mastery of the Channel. The history of the English navy is chequered: there have been periods when its pretensions were low and its achievements humble: but since the days of Alfred the conviction has never been lost that the safety of England lies in her command of the sea. Fortresses and walled cities are useful: it is a very great achievement to have given them to the country: London alone, restored by Alfred, was the nation’s stronghold, the nation’s treasure house, a city full of wealth, filled with valiant citizens, unconquered and defiant: that was a very great gift to the country: but it was a greater achievement still to have given to the country a fleet which was ready to meet the enemy before [21]they had time to land, and to give them most excellent reasons why they should not land: to make the people understand that above all things, and before all, it was necessary for all time to keep the mastery of the seas.

Remember, therefore, that Alfred, thus, gave us the command of the seas.

As Rudyard Kipling, our patriot poet, says:

“Never a wave of all her waves”—and it was Alfred who first sent out the English blood to redden those waves in defence of hearth and home.

Now, there can be no doubt that if he had advanced upon the great defeat of the Danes he might have recovered the whole of the country and become not only its overlord, as his grandfather Egbert had been before him, but its king. No doubt he was tempted: to a successful commander more successes always lie before him waiting to be snatched. This dream of conquest he renounced. He sat down with what he had—the old kingdom of his forefathers, strengthened by his new fleet: by the stronghold of London: and by the restored courage and self-respect of his people. The dream of conquest was a dream of [22]personal ambition: he put it aside. It was part of that renunciation of self which belongs to the whole of his career. The historian Green has pointed out that Alfred “is the only instance in the history of Christendom of a ruler who put aside every personal aim or ambition in order to devote himself wholly to the welfare of those whom he ruled.”

We have considered Alfred as a captain, a conqueror, and the founder of our navy. We will now consider him in the capacity of king, administrator, and law-giver.

I do not claim for Alfred that he was the creator of the English law. His glory consists mainly in his adaptation of the old order to the new: he took all that was left of the shattered past and moulded it anew, with additions to suit the new situation, and for the most part on the same lines. You will ask, perhaps, how much of the honour due to Alfred’s achievements should be given to his ministers and how much to himself? Assign to his officers all the credit possible, all that belongs to the faithful discharge of duty: still the initiative, the design of the whole of the past, is absolutely due to Alfred himself. He must not be considered as a modern king—the modern king reigns while the people rule: he was the king who ruled: his will ruled the land: he had his Parliament: his Meeting of the Wise: but his will ruled [23]them: he appointed his earls or aldermen: his will ruled them: he had his bishops: his will ruled them. From the time when he began to address himself to the organisation of a strong nation—that is to say, from the time when the Dane was baptized, his will ruled supreme. No law existed then to limit the king’s prerogative. The king was imperator, commander of the army, and every man in the country was his soldier.

Among the monuments of his reign there stands out pre-eminent his code of laws. He did not, I say, originate or invent his code. He simply took the old code and rewrote it, with additions and alterations to suit the altered conditions of the time. He understood, in fact, the great truth, which law-makers hardly ever grasp, that successful institutions must be the outcome of national character. Now, the laws and customs of these nations—Saxons, Angles, and Jutes—were similar, but there were differences. They had grown with the people, and were the outcome of the national character. Alfred took over as the foundation of his work for Wessex the code compiled for the West Saxons by his ancestor, King Ina: for Mercia, that compiled by Offa, King of Mercia: for the Jutes, that compiled by Ethelbert, King of Kent. In his work two main principles guided the law-giver: first, that justice should be provided for every one, high and low, rich and poor: next, that [24]the Christian religion should be recognised as containing the Law of God: which must be the basis of all laws. Both these principles were especially necessary to be observed at this time. The devastation of the long wars had caused justice to be neglected: and the destruction of the churches, and the murder or flight of the clergy, had caused the people to relapse into their old superstitions.

King Alfred then boldly began his code by reciting the Laws of God. His opening words were: “Thus saith the Lord, ‘I am the Lord thy God.’” That is his keynote. The laws of a people must conform with the Laws of God. If they are contrary to the spirit of these laws they cannot be righteous laws. In order that every one might himself compare his laws with the Laws of God, he prefaced his laws first by the Ten Commandments; after this he quoted at length certain chapters of the Mosaic Law. These chapters he followed by the short epistle in the Acts of the Apostles concerning what should be expected and demanded of Christians. Finally, Alfred adds the precept from St. Matthew, “Whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them.”

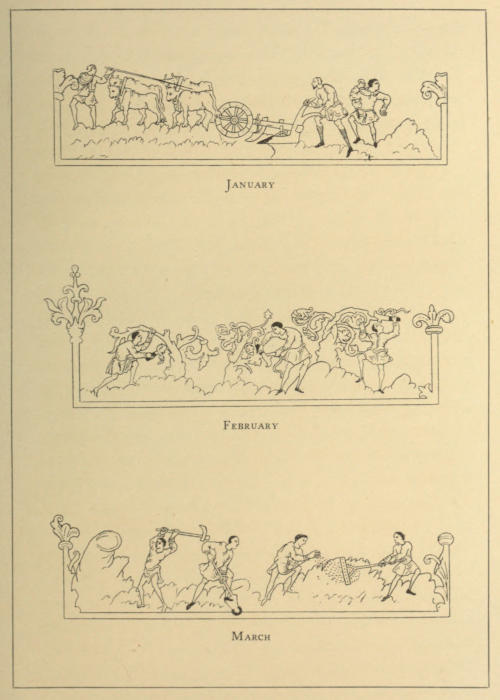

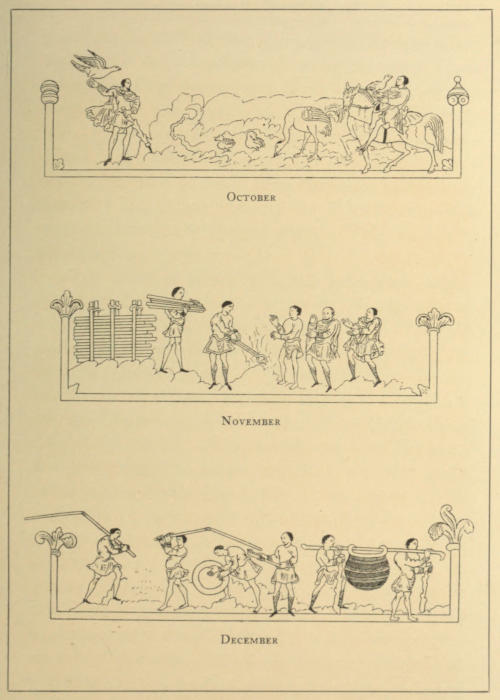

THE SEASONS—JANUARY TO MARCH

(Cottonian Library)

Some writers have assumed that Alfred required of his subjects by this preamble that they should be governed in all the details of life by the Mosaic Law. This view I cannot accept. Alfred set forth, I think, these laws in order that his own might [25]be compared with them where comparison was possible, and in order to challenge comparison and to give the greater weight to his own laws by showing that they were based in spirit and, mutatis mutandis, on the Levitical Law and on the Law of the Gospel.

Moreover, in order to connect the whole system of justice with religion, in order to teach the people in the most efficacious manner possible that the Church desires justice above all things, he added to the sentence of the judge the penance of the Church. This subjection of the law to the Church would seem intolerable to us. At that time it was necessary to make a rude, ignorant, and violent people understand that religion must be more than a creed: that it must have a practical and restraining side; a man who was made to understand that an offence against the law was an offence against the Church which would be punished by the latter as well as by the secular judge, was made for the first time to feel the reality of the Church.

This firm determination to link the Divine Law and the Human Law: this firm reliance on the Divine Law as the foundation of all law: is to me the most characteristic point in the whole of Alfred’s work. The view—the intention—the purpose of King Alfred are summed up, without intention, by the poet whom I have already quoted. The following words of Rudyard Kipling might [26]be the very words of Alfred: they breathe his very spirit—they might be, I say, the very words spoken by Alfred:

Alfred endeavoured to rebuild the monasteries. He then made the discovery that the old passion for the monastic life was gone: he could get no one to go into them. Forty years of a life and death struggle had killed the desire for the cloister: the people had learned to love action better than seclusion—their ideal was now the soldier, not the monk. A great gain for the people, which never afterwards returned to its ancient love of the Rule and the Hood.

His chief design in rebuilding the monasteries was to restore the schools. The country had fallen so low in learning that there was hardly a single priest who could translate the Church Service into Saxon, or could understand the words he sang. Alfred sent abroad for scholars: he made his Religious House not only a place for the retreat of pious men and women, but also the home—the only possible home—of learning, and [27]the seat of schools. It is long since we have regarded a monastery as a seat of learning, or the proper place for a school. Go back to Alfred’s time and consider what a monastery meant in a land still full of violence: in which morals had been lost: justice trampled down: learning destroyed: no schools or teachers left: the monastery stood as an example and a reminder of self-restraint: peace: and order: a life of industry and such works as the most ignorant must acknowledge to be good: where the poor and the sick were received and cared for: the young were taught: and the old sheltered. It was the Life which the monastery Rule professed; the aim rather than any lower standards accepted by the monks: which made a monastery in that age like a beacon steadily and brightly burning, so that the people had always before their eyes a reminder of the self-governed life. Most of us would be very unwilling to see the monastery again become a necessity of the national life: yet we must admit that in the ninth century Alfred had no more powerful weapon for the maintenance of a religious standard than the monastery.

In the cause of education, indeed, Alfred was before his age, and even before our age. He desired universal education. At his Court he provided instructors for his children and the children of the nobles. They learned to read and write, they studied their own language and its poetry: [28]they learned Latin: and they learned what were called the “liberal sciences,” among them the art of music. But he thought also of the poorer class. “My desire,” he says, “is that all the freeborn youths of my people may persevere in learning until they can perfectly read the English Scriptures.” Unhappily he was unable to carry out this wish. Only in our own days has been at last attempted the dream of the Saxon King—the extension of education to the whole people.

One more aspect of Alfred’s foresight. He endeavoured to remove the separation of his island from the rest of the world: he connected his people with the civilisation of Western Europe by encouraging scholars and men of learning, workers in gold, and craftsmen of all kinds, to come over: he created commercial relations with foreign countries: a merchant who made three voyages to the Mediterranean he ennobled: he sent an embassy every year to Rome: he sent an embassy as far as India: he brought to bear upon the somewhat sluggish minds of his people the imagination and the curiosity which would hereafter engender a spirit of enterprise to which no other nation can offer a parallel.

It was partly with this view that he strongly enforced the connection with Rome. One bond of union the nations of the West should have—a common Faith: and that defined and interpreted [29]for them by the same authority. Had it not been for that central authority the nations would have been divided, rather than drawn towards each other, by a Christianity split up into at least as many sects as there were languages. Imagine the evil, in an ignorant time, of fifty nations, each swearing by its own creed, and every creed different. From this danger Alfred kept his country free.

The last, not the least, of his achievements is that to Alfred we owe the foundations of our literature: the most noble literature that the world has ever seen. He collected and preserved the poetry based on the traditions and legends brought from the German Forests. He himself delighted to hear and to repeat these legends and traditions: the deeds of the mighty warriors who fought with monsters, dragons, wild boars, and huge serpents. He made his children learn their songs: he had them sung in his Court. The tradition goes that he could himself sing them to the music of his own harp. This wild and spontaneous poetry which Alfred preserved is the beginning of our own noble choir of poets. In other words, the foundation of that stately Palace of Literature, built up by our poets and writers for the admiration and instruction and consolation of mankind, was laid by Alfred. Well, but he did more than collect the poetry, he began the prose. Before Alfred there was no Anglo-Saxon prose.

[30]

I have already quoted Green’s remark that in everything that Alfred designed or accomplished he put aside every personal aim or ambition in order to devote himself wholly to the welfare of those over whom he ruled. In his capacity as author this remark is specially illustrated. You all know that it is the leading characteristic—or the infirmity—of the poet, author, writer, to consider himself as part of his message. Alfred put himself aside: he presented his works in translations: they were, indeed, translations: but embellished, altered, enriched by his own work thus modestly presented. There is one book, now quite neglected, which for a thousand years profoundly moved the world of Western Europe. It is a book, written in prison by a noble Roman named Boethius, a philosopher, soldier, poet, and mathematician. It is entitled the Consolation of Philosophy. Fortunately the author, who wrote it from a prison, had time to finish it before they executed him. This book Alfred translated or imitated. For he filled his translations with his own thoughts and his own judgments. He gives his own theories of government: of the duties of a king: of maintaining the population, and especially the proper proportion of the different classes required to keep the nation in a state of efficiency. Every man in the country is a weapon which may be—and should be—used for the advancement of the general welfare. It is the [31]king’s duty to select the best instruments, and to use them to the best advantage. We even find brief notes of his own thoughts. “This,” says the king, among these notes, “I can now truly say, that so long as I have lived I have striven to live worthily, and after my death to leave my memory to my descendants in good works.”

It is not the part of this Introduction to dwell upon the whole of Alfred’s literary work. It is enough if we recognise that he introduced education and restored learning. In the course of time, innumerable books were attributed to him: it is said that he translated the Psalms. A book of proverbs and sayings is attributed to him—each one begins with the words “Thus said Alfred.” The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and contemporary record of events is said to have been commenced by him. And since it is certain from the life of the king by one of his own Court that he was regarded by all classes of his people with the utmost reverence and respect, I think it is extremely likely that some of his people listened and took down in writing the sayings of the king, so that the book of Alfred’s sayings may be as authentic as the sayings of Dr. Johnson, recorded by his admirer Boswell.

There is next to be observed the permanence of Alfred’s institutions. They do not perish, but remain. His Witenagemot—Meeting of the Wise—is our Parliament—it has developed into our [32]many Parliaments. His order of King, Thane, and Freeman is our order of King, Lords, and Commons. His theory of education was carried out in some of the towns, and in all the monasteries and cathedrals: there are schools still existing which owe their origin to a period before the Norman Conquest. His foundation of all law upon the Laws of God remains our own: his liberties are our liberties: his navy is the ancestor of our navy: the literature which he planted has grown into a goodly tree—the Monarch of the Forest: the foreign trade that he began is the forerunner of our foreign trade: it would seem as if there was hardly any point in which we have reason to be grateful or proud which was not foreseen by this wise king.

To look for the secret of his wisdom is like looking for the secret of making a great poem or writing a great play: it may be arrived at and described, but it is not therefore the easier of imitation. Alfred’s secret is quite simple. His work was permanent because it was established on the national character. It was in order to make this point clear that I dwelt at length on the character of the people over whom Alfred ruled. He knew their character, and by instinct, which we call genius, he gave his people the laws and the education, and the power of development for which they were fitted. No other laws, no other kind of [33]government, will enable a people to prosper except those laws to which they have grown and are adapted. Only those institutions, I repeat, are permanent which are based on the national character. That was the secret of King Alfred the law-giver.

It may be asked, what manner of man to look at was this great king? His biographer, Asser, who knew him well, has not thought fit to tell us. He only says in words of flattery that Alfred was more comely and gracious of aspect than his brothers. These brothers, four in number, were all kings before him, and all died young. Alfred himself was afflicted by a disease which never left him. It is therefore presumable that there was some congenital weakness in them all. This was not physical weakness: whatever the disease, it did not interfere with Alfred’s courage or his prowess in battle. This is proved by the fact that the Saxon kings actually fought in person in the forefront of the battle, and on foot. Alfred, for instance, fought in a dozen battles at least, and always with the valour that belongs to a strong man. I take him to have been a man of good stature and of strong build: a man whose appearance was kingly: who impressed his followers with the gallant and confident carriage of a brave soldier. But as to his face, or the colour of his hair or eyes, I can tell nothing. Fair hair he had, [34]I think, and blue eyes: or the more common type of brown hair and gray eyes. When a king resigns all personal ambitions and seeks nothing for himself, it seems natural and fitting that, while his works live after him, he himself should vanish without leaving so much as a tradition of his face or figure.

From time to time in history—generally in some time of great doubt and trouble: or in some time when the old ideals are in danger of being forgotten: or in some time when the nation seems losing the sense of duty and of responsibility: there appears one, man or woman, who restores the better spirit of the people by his example: by his preaching: by his self-sacrifice: by his martyrdom. He is the prophet as priest: the prophet as king: the prophet as law-giver. There passes in imagination before us a splendid procession of men and women who have thus restored a nation or raised the fallen ideals. Among them we recognise many faces: there are Savonarola: Francis of Assisi: Joan of Arc: our own Queen Elizabeth, greatest and strongest of all women: the Czar Peter. But the greatest figure of them all—the most noble—the most god-like—is that of the ninth-century Alfred, king of that little country which you have upon your map. There is none like Alfred in the whole page of history: none with a record altogether so blameless: none so wise: [35]none so human. We have allowed the memory of him to be too much forgotten: only here and there a historian—such as Freeman or Green—lifts up his voice and proclaims aloud that he has no words with which to speak adequately of this great Englishman. Perhaps the noble lines of Tennyson, written for another prince whose memory is dear to us all, may be referred to Alfred:

It is the purpose—the wise and patriotic purpose—of certain persons to erect, for these and other reasons, a monument, visible to all, to the memory of King Alfred.

Some of the points which I have recalled in this paper may help to show why such a monument would have been fitting at any time during the last thousand years. There is, however, a special reason which makes the erection of such a monument very necessary—I use the word necessary [36]advisedly—at the present time. In the year 1897—on that memorable day when we were all drunk with the visible glory and the greatness of the Empire—there arose in the minds of many a feeling that we ought to teach the people the meaning of what we saw set forth in that procession—the meaning of our Empire—not only what it is, but how it came—through whose creation—by whose foundation. Now so much is Alfred the Founder that every ship in our Navy might have his name—every school his bust: every Guildhall his statue. He is everywhere. But he is invisible. And the people do not know him. The boys do not learn about him. There is nothing to show him. We want a monument to Alfred, if only to make the people learn and remember the origin of our Empire—if only that his noble example may be kept before us, to stimulate and to inspire and to encourage.

It seems unnecessary to urge that a monument to Alfred must be set up in Winchester, and not in London or in Westminster, or anywhere else. Here lies the dust of the kings his ancestors, and of the kings his successors. Thirty-five of his line made Winchester their capital: twenty were buried in the Cathedral. In this city Alfred received instruction from St. Swithin: the city was already old and venerable when Alfred was a boy. He was buried first in the Cathedral, [37]and afterwards in the Abbey, which he himself founded, hard by. The name of Alfred’s country, well-nigh forgotten, except by scholars, has been revived of late years by a Wessex man—Thomas Hardy. But the name of Alfred’s capital continues in the venerable and historic city of Winchester, which yields to none in England for the monuments and the memories of the past.

I venture, lastly, to express my own personal hope that great as were the achievements of Alfred—the keynote to be struck and to be maintained will be that Alfred is, and will always remain, the typical man of our race—call him Anglo-Saxon, call him American, call him Englishman, call him Australian—the typical man of our race at his best and noblest. I like to think that the face of the Anglo-Saxon at his best and noblest is the face of Alfred. I am quite sure and certain that the mind of the Anglo-Saxon at his best and noblest is the mind of Alfred: that the aspirations, the hopes, the standards of the Anglo-Saxon at his best and noblest are the aspirations, the hopes, the standards of Alfred. He is truly our Leader, our Founder, our King. When our monument takes shape and form let it somehow recognise this great, this cardinal fact. Let it show somehow by the example of Alfred the Anglo-Saxon at his best and noblest—here within the circle of the narrow seas, [38]or across the ocean; wherever King Alfred’s language is spoken; wherever King Alfred’s laws prevail; into whatever fair lands of the wide world King Alfred’s descendants have penetrated.

Walter Besant.

[39]

By Frederic Harrison

[40]

[41]

It is a commonplace with historians—and with the historians of many countries and different schools of opinion—that our English Alfred was the only perfect man of action recorded in history; for Aurelius was occasionally too much of the philosopher; Saint Louis usually too much of the saint; Godfrey too much of the Crusader; the great Emperors were not saints at all; and of all more modern heroes we know too much to pretend that they were perfect. Of all the hyperboles of praise there is but one that we can safely justify with the strictest canons of historic research. Of all the names in history there is only our English Alfred whose record is without stain and without weakness—who is equally amongst the greatest of men in genius, in magnanimity, in valour, in moral purity, in intellectual force, in practical wisdom, and in beauty of soul. In his recorded career from infancy to death, we can find no single trait that is not noble and suggestive, nor a [42]single act or word that can be counted as a flaw.

In the history of modern Europe there is nothing which can compare in duration and in organic continuity with the unbroken evolution of our English nation. And now that the royal house of France has passed from the sphere of political realities into that of historic memories, there is no dynasty in Europe which can be named in the same breath with that which has seen a succession of forty-nine sovereigns since Alfred; nor has any King or Cæsar a record of ancestry which can compare with that of the royal Lady who through thirty-two generations traces her lineal descent to the Hero-King of Wessex.

We have long given up the venerable fables which once gathered round the name of Alfred, as round Romulus, or Theseus, King Arthur, or the Cid. Every schoolboy knows that Alfred was not formally King of all England; nor did he introduce trial by jury, or electoral institutions; he did not found the University of Oxford; nor write all the pieces which are attributed to his pen; he was perhaps too practical a man to let his own supper get burnt on the hearth; and too wary a general to go about masquerading with a harp in the enemy’s camp. But the historic Alfred whom we know to-day is a personage more splendid and lifelike than the legendary Alfred ever was. [43]Though much of what our grandsires believed about Alfred is now known to be poetry and pious fraud, the traditional Alfred was quite just in general effect, and modern research has given us a portrait both nobler and more definite than that drawn by the patriotic imagination of a less critical age. Patriotic imagination itself falls far short of scrupulous scholarship when it seeks to draw the likeness of a real hero.

It is true that the field of Alfred’s achievements was relatively small, and the whole scale of his career was modest indeed when compared with that of his imperial compeers. He inherited a kingdom which covered only a few English counties, and at one time his realm was reduced to a smaller area than that of some private landlords of modern times. Beside the great Emperor Charles, or the German Ottos, Henrys, and Fredericks of the Middle Ages, his dominions, his resources, his armies, his battles, his fleets, his administrative machinery, his contemporary glory—all these were almost in miniature—hardly a tithe of theirs. But, we should remember, it is quality not quantity that weighs in the impartial scales of History. True human greatness needs no vast territories as its stage—nor do multitudes add to its power. That which tells in the end is the living seed of the creative mind, the heroic example, the sovereign gift of leadership, the undying inspiration of genius and faith.

[44]

Turn to the Chronicle and to Asser’s Life, with recent historians and scholars, and mark those miracles of patience, valour, indomitable energy by which the great king rescued from the savage Norsemen the England of our forefathers. Watch him as he returns to the charge after every repulse, rallies his exhausted men, gathers up new armies, plans fresh methods of war, and at last wins for his people prosperity, honour, and peace. The scale of these campaigns was narrow—the armies were small—not indeed weaker than were the Greeks at Thermopylae and Marathon; but the annals of war have nothing grander than the long record of sagacious heroism by which Alfred saved England for the English. Then note the genius with which he saw that the Norsemen must be met on the sea, with which he organised a navy of ships built on a new design of his own. Alfred is not only the forerunner of Marlborough and Wellington, but he was the first to teach the Saxon to be a seaman.

A fine land that had once known prosperity, and even culture, lay utterly ruined and desolate when Alfred undertook the vast task of its restoration—its material, moral, intellectual reform. He said in his Will, “we were all despoiled by the Heathen Folk.” He found the enemy in possession of something like a standing army of disciplined soldiers; and we should note how the [45]Chronicle calls the Norsemen “the army.” He met this by instituting a regular militia with local garrisons and a reserve force capable of systematic war. When Alfred marshals a new campaign we find that the era of wild raids to be met by casual musters of countrymen is a thing of the past. Alfred at last has his “army” too. We are dealing with regular armies capable of sustaining organised campaigns.

A navy needed to be created and not simply reformed. And the safety of the southern shores of England—the first command of the Channel—must be dated from the day when Alfred began the formation of an adequate fleet. It is true that in the absence of competent seamen in Wessex, he had to man his earliest ships with Frisians from over the sea. But in later years he came to have a really English fleet of his own. And it is plain that in a true sense he is the inventor, but not the actual founder, of a national navy: of that sea-power which is the birthright of this island.

When Alfred was chosen king, “almost against his will,” we are told, the prospect was one to appal the stoutest heart. In his boyhood the Northmen had begun to winter in Kent, had taken Canterbury and London by storm, and pushed up the Thames. A few years later they stormed Winchester and ravaged Kent. In the reign of his brother, Ethelred, they stormed York, and [46]invaded Mercia, whose king, Burhred, had married Alfred’s sister. They next laid waste East Anglia, martyred its king, Edmund, and threatened Wessex. The Danes (as they were now known) sailed up the Thames, and formed a camp round Reading. In a fierce battle at Ashdown a victory had been won for the moment by the energy and valour of Alfred; but defeats followed, Surrey was lost, and Ethelred died, it is supposed of his wounds.

The young king of twenty-two came to the throne of his ancestors in a dark hour. The supremacy of Wessex in England, won by his grandfather, Egbert, had vanished. Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, and parts of Wessex had been desolated; the abbeys had been sacked, the monks murdered, the churches, schools, and homesteads ruined. The Danish invaders were masters of all Northern, Eastern, and Central England, and the heart of Wessex was open to assault. The young king met them at Wilton with a small force, but after a stubborn fight was beaten off. He was forced to purchase a precarious truce.

In this year, 871, the Chronicle relates (in its grim, laconic style), the [Danish] army came to Reading, and three nights after, the Alderman Ethelwulf fought them. Four nights after this, Ethelred and Alfred led a large force to Reading, and “there was great slaughter on both sides; [47]the Alderman Ethelwulf was slain, and the Danes held possession of the battle place.” “And four nights after, Ethelred and Alfred fought with all the army at Ashdown”; many thousands were slain; “and they were fighting until night.” And fourteen nights after, King Ethelred and Alfred his brother fought against the army at Basing, and there the Danes gained the victory. “And two months after, King Ethelred and Alfred his brother fought against the army at Merton ... and there was great slaughter on each side, but the Danes held possession of the battle place. And after this fight there came a great summer force [of Danes] to Reading. And the Easter after, King Ethelred died. Then Alfred his brother succeeded to the kingdom of the West Saxons, and one month after, with a small force, he fought against all the army at Wilton, but the Danes held possession of the battle place. And this year nine great battles were fought against the army in the kingdom south of the Thames; besides which Alfred, the king’s brother, and individual aldermen, and king’s thanes, often rode raids on them, which were not reckoned.”

Such were the disasters with which Alfred’s reign began. His fighting-men were exhausted or slaughtered; his kingdom torn from side to side, and its chief towns stormed: the northern, central, and eastern kingdoms had been blotted out. [48]Burhred of Mercia was driven over sea, and Wessex was forced to buy a brief rest with gold. Alfred equipped a few ships and gained some temporary success. But soon after, the Danes with a great fleet swept round the south coast and penetrated into Dorsetshire and Devonshire. Thence passing northwards into Gloucestershire, and reinforced by a new fleet in the Bristol Channel, the Danish host suddenly fell upon Wiltshire. The Saxon defence was broken in pieces. “The [Danish] army harried the West Saxons’ land, and settled there, and drove over sea much of the people, and of the rest the most they harried. And the people submitted to them, save the King Alfred; and he, with a little band, withdrew to the woods and fastnesses in the moors.”

Alfred seemed utterly ruined. He, the grandson of Egbert overlord of England, the successor on the throne of Wessex of his father and his three brothers, had been king just seven years, and in scores of battles he had been fighting the Danes for ten years. He had seen the three northern kingdoms of Angles broken up and the reigning house in each exterminated. Step by step he had seen Kent, Surrey, and Wessex overrun; assailed by sea and land, from the coast, the rivers, and the Bristol Channel. His own people had been driven across sea, or crushed into submission; and he himself, with a small band of followers, was forced [49]to find shelter in woods and swamps. His lot seemed hopeless, but he alone did not despair.

The crisis was indeed the gravest to which our country has ever been exposed. The Danish host was now a large and disciplined army bent on conquering and settling new lands, and already masters of the island from the Severn to the Tees. They were the fiercest and rudest of the tribes which had broken into Europe; Heathens, full of hatred and scorn for the religion, culture, arts, and civilisation of Christendom. With a real genius for war, both by sea and land, fired with the thirst of glory and adventure, they were better armed, more mobile, more martially organised than Saxon, Angle, or Jute. Short of a miracle their ultimate triumph over the whole island seemed certain. Had it been achieved, the civilisation of England would have been retarded for ages. Christianity, learning, arts, and legislation, which had progressed for two centuries, would have been stamped out, and our island would have been the seat of a barbarous and heathen horde. From the nature of their island conquest and their own mastery of the seas, they could not have been absorbed in Christendom so rapidly as were the Normans of France, or the Danubian tribes of Germany. They might have resisted for centuries both conversion and conquest from Europe. Nay more, from the supreme opportunities afforded by our island and all [50]its resources as a basis for an imperial race, it is too probable that the heathen Danes, once firmly seated in the whole of Britain, might have proved the lasting scourge of Europe itself. From this tremendous peril, England and Europe were saved by the genius of our Saxon hero.

In the Easter of that year, 878, the Chronicle relates, “Alfred, with a little band, wrought a fortress at Athelney, and from that work warred on the army, with that portion of the men of Somerset that was nearest.” Athelney was a bit of firm ground in the morasses formed by the Parret and the Tone in Somersetshire. There, for a few months, the king organised a new army, drawn from Somerset and Wilts and such Hants men as were left. In May he suddenly dashed out of the wood of Selwood: “his Wessex men were rejoiced to see him”: he fought a great fight against the whole “army” at Ethandune, near Westbury, put them to flight and drove them to their camp, where, after fourteen days of siege, he forced the Danes to surrender. It was a crushing victory—the turning-point in the life of Alfred—in the life of England.

The importance of it was this. A part of the beaten host sailed away over seas. But the rest, under their king, Guthrum, agreed to accept Christian baptism, to withdraw out of Wessex and the western half of Mercia, and to settle peaceably [51]in East Anglia, north of Thames. Guthrum, with thirty of his chiefs, came to Alfred’s stronghold, received at his baptism the Saxon name of Athelstan from his victor and god-father, remained twelve days with the king and gave large presents. By the Peace of Wedmore, 878, Wessex and West England were saved, and the ultimate incorporation of the Danes with Christendom was secured. At first sight and in strict form, Alfred had surrendered Eastern England to the conqueror. The Treaty was not honestly observed by the Danes, and Guthrum and his warriors again became enemies. But the core of England was saved; the amalgamation of Dane and Saxon was founded in principle and in distant effect. And the Peace of Wedmore was a stroke of genius more daring and more far-reaching in result than the splendid victory of Ethandune by which it had been won.

Leaving the Danes for the present undisturbed in all Eastern England between Thames and Tees, Alfred occupied himself with restoring his shattered and desolated Kingdom of Wessex. His treasury was empty, the towns were in ruins, and civil government paralysed. He built forts, abbeys, and schools; repeopled and stocked waste districts; and set to work to establish something like a standing military force to meet the regular “army” of Danes. Hitherto Alfred had commanded loose [52]levies of half-armed men, who by custom disbanded after two months’ service. This had enabled small but organised bands of Danes to overrun England, and to win practical successes even when beaten by numbers in the fields. Alfred, like William of Normandy in the eleventh, like Cromwell in the seventeenth century, saw, even so early as the ninth century, that victory belonged not to numbers but to regular armies. He organised what was at least a permanent local militia, with definite quotas of levies and an alternate system of reserves, besides the garrisons of fortified places. He rebuilt the broken fortresses, exercised his men in entrenchments, and adapted from the Danes their military arts.

But his eye of genius foresaw that the country was not safe whilst the invaders had command of the seas. Thus he organised a fleet, and assessed the ports and maritime districts to support it. He himself ultimately designed a class of ship, longer and swifter than those in use, though at first he had to man his navy with mercenary Frisians and sea-rovers. Towards the close of his reign, and in that of his son and grandson, a genuine English navy asserted its command of the Channel, which two centuries later his feeble successors lost again.

He then turned to reorganise the system of justice, making the judges the direct ministers of the sovereign, personally responsible to him, and [53]subject in certain cases to his final appeal. His biographer tells us that he keenly revised unjust judgments, and tradition exaggerated this into a preposterous legend. He caused a collection of the old laws to be compiled—carefully resisting any general new legislation, or the fusion of the Wessex, Mercian, and Kentish customs into a symmetrical code. His laws were a compilation, with selection of what was approved best, and rejection of what was condemned as obsolete or mischievous. In the spirit of conservative amendment which marks his whole career, he is careful to tell us that he “durst not venture to set down much of his own.” He was content with partial revision and excision, under the advice of his Witan.

The combination in a code of Saxon, Anglian, and Kentish “dooms” gave a certain stimulus towards national union in a larger aggregate. But a much more powerful cause unexpectedly emerged out of the Danish invasions. By these savage shocks the royal houses that had ruled in Mercia, in East Anglia, in Northumbria, were not only overthrown, but were extinct. Alfred remained the one victorious king of the race of Cerdic, the legitimate sovereign of Wessex and Kent, the natural source of kingly authority wherever Danes were not in possession of rule. Having won back the western half of Mercia by the Peace of Wedmore, Alfred became its king by silent consent of [54]its Anglian people. He did not fuse West Mercia with Wessex; he was not formally installed or crowned. He made Ethelred, the husband of his daughter Ethelfleda, alderman, and himself exercised the functions of king, with a separate Mercian administration and Witan. By this wise and tentative system of dual monarchy, Alfred was firmly seated the undisputed sovereign of Southern England from the mouth of the Thames to the Exe, ruling by his son-in-law all Central England west of Watling Street from the Severn to the Ribble. He thus became, but a few years after his romantic sortie from Athelney, the most powerful ruler holding the widest single realm within our island. This effected a practical supremacy over the main part of England proper, except for the Danes in the east. And he thus made it possible that there should be a true English kingdom, of which his son Edward, and his grandson Athelstan, were formally recognised as sovereigns.

More than once after the settlement effected at Wedmore and the years of peace it brought, Alfred had to meet formidable enemies both by sea and land. But fierce as these campaigns were, they did not imply such incessant warfare, such desperate crises, as had made the first ten years of his early manhood one long battle for life and home. Alfred was now at least as well able to defend his country from the Scandinavian invaders as were the rulers [55]of France and Germany, on whom the storm burst whenever the Northmen had been checked in England.

Six years after the Peace of Wedmore Alfred had to meet again a force of Danes which had pushed up the Thames, and to chastise the East Anglians who had violated the Treaty by a fresh outbreak. A new treaty with Guthrum gave Alfred possession of London and adjacent parts of Middlesex, which were finally rescued from the Danes, and annexed to English Mercia under its alderman, Ethelred, Alfred’s son-in-law. Again, in the twenty-third year of Alfred’s reign a new body of Vikings from Norway descended on to Wessex and were joined by a second rising of the Anglian Danes. For more than two years the war was continued over a large part of England—from the Thames and its affluents across to the Severn; from Exeter northwards to Chester. By a series of vigorous and skilful campaigns, in concerted strategy of armies and fleets, the king, his son and his son-in-law, defeated this formidable combination, captured the entire Danish fleet, overawed the Britons of Wales and Cornwall, forced the East Anglian Danes to keep within their own reserves, and drove the northern freebooters across the Channel. Once again, in the last years of his reign, Alfred had to meet a new invasion of pirates at sea, who were defeated in a [56]series of fierce and bloody encounters. These are the last recorded campaigns of the king, who from his boyhood, for nearly thirty years, had been continually in arms; but, by obstinate wars and sagacious policy, he had tamed the savage Norsemen, and at length transmitted to his descendants a kingdom doubled and trebled in extent and greatly increased in culture and strength.

England had been rescued from barbarism by the heroism of Alfred and his aptitude for war. But it is his genius as a creative statesman which left permanent effects on the history of England and made him one of the principal founders of the greatness of our country. His conversion and settlement of Guthrum’s Danes in East Anglia, his generous forbearance and his repeated treaties with them in spite of their faithless conduct, led to the ultimate amalgamation of Dane, Angle, and Saxon, which created the compound English race. A less sagacious victor would have sought to clear his country of Norsemen, and would undoubtedly have been overwhelmed by successive invasions himself. Alfred’s whole career shows a conscious purpose to break with the tribal and local isolation of the West Saxon, to attach Wessex with Mercia, to civilise Dane and Briton, and to bring England into closer union with the religious and political system of Europe.

[57]

Alfred’s restoration of London was the stroke of a true statesman. The city had been stormed by the Norsemen in 851, and since then had been desolate and almost deserted, save when occupied by the Danes as winter-quarters, as it was in 872. Within the Danish power it remained until 886, the year of Alfred’s second treaty with Guthrum. By that it was ceded to him with the adjacent part of Middlesex. The king rebuilt its walls and repeopled it, and added it to Mercia, from which it was not again separated. The military and political genius of Alfred and his long experience of war with the Danes had seized on the immense importance of a restored London, carved out of Danish East Anglia, with power to block all incursions up the Thames and its various tributary rivers. The restoration of London by the King of Wessex was thus an epoch in the history, not only of the city itself, but of the country of which it was destined by nature to be the capital.

Alfred had been at this date fifteen years on the throne, and the whole aspect of affairs was changed. When he began to reign heathen barbarians were masters of the Eastern, Central, and Northern parts of England, and threatened to break up Wessex. They swept round all coasts, and pushed up the rivers, plundering, burning, raiding, and slaughtering. Now, they were shut up in East Anglia, outwardly christianised, bound [58]by formal treaties of peace, confronted at sea by strong fleets, and gradually submitting to the moral force of superior civilisation. As Goths and Franks were overawed by the Roman empire they conquered, so Vikings and Danes gradually recognised the higher organisation of Wessex. Alfred at last ruled over a compact realm stretching from the Channel up to the Ribble, with fortresses in such places as Rochester, London, Exeter, and Chester. Lastly, in a rebuilt London, he was master of the Thames, with a powerful base on the Danish side of the great river.