Title: Moral Emblems

Author: Robert Louis Stevenson

Release date: January 1, 1997 [eBook #772]

Most recently updated: August 16, 2019

Language: English

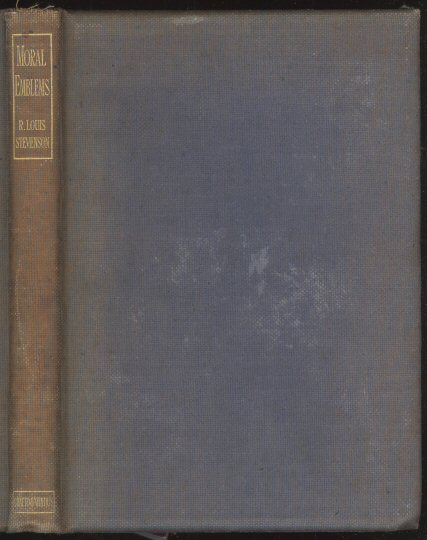

Credits: Transcribed from the 1921 Chatto and Windus edition by David Price

Transcribed from the 1921 Chatto and Windus edition by David Price, email ccx074@pglaf.org

& OTHER POEMS WRITTEN AND

ILLUSTRATED WITH WOODCUTS

BY ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON

FIRST PRINTED AT THE DAVOS

PRESS BY LLOYD OSBOURNE

AND WITH A PREFACE

BY THE SAME

LONDON

CHATTO & WINDUS

1921

All rights reserved

It is with some diffidence that I sit down at an age so mature that I cannot bring myself to name it, to write a preface to works I printed and published at twelve.

I would have the reader see a little boy living in a châlet on a Swiss mountain-side, overlooking a straggling village named Davos-Platz, where consumptives coming to get well more often died. It was winter; the sky-line was broken by frosty peaks; the hamlet—it was scarcely more then—lay huddled in the universal snow. Morning came late, and the sun set early. A still, silent and icy night had an undue share of the round of hours, which at least it had the grace to mitigate by a myriad of shining stars.

The little boy thought it was a very jolly place. He loved the tobogganing, the skating, the snow-balling; loved the crisp, p. vitingling air, and the woods full of Christmas trees, glittering with icicles. Nor with his toy theatre and printing-press was the indoor confinement ever irksome. He but dimly appreciated that his stepfather and mother were less happy in so favoured a spot. His mother’s face was often anxious; sometimes he would find her crying. His stepfather, whom he idolised, was terribly thin, and even to childish eyes looked frail and spectral. The stepfather was an unsuccessful author named Robert Louis Stevenson, who would never have got along at all had it not been for his rich parents in Edinburgh. The little boy at his lessons in the room which they all shared grew used to hearing a sentence that struck at his heart. Perhaps it was the tone it was uttered in; perhaps the looks of discouragement and depression that went with it.

‘Fanny, I shall have to write to my father.’

It served to make the little boy very p. viiprecocious about money. In a family perennially short of it he learned its essentialness early. He knew too, that he was a dreadfully expensive child. His stepfather paid forty pounds for his winter’s tutoring, not to speak of an additional outlay on a dying Prussian officer who taught him German with the aid of a pocket-knife stuck down his throat to give him the right accent. It was with consternation that he once heard his stepfather say in a voice of tragedy: ‘Good Heavens, Fanny, we are spending ten pounds a week on food alone!’

The little boy, under the stress of this financial urgency, decided to go into business, finding a capital opening in the Hotel Belvidere, where a hundred programmes were required weekly for the Saturday night concerts. A gentleman with a black beard, who was in charge of these arrangements, willingly offered to pay two francs fifty centimes for each set of programmes. The little boy was afraid of the gentleman p. viiiwith the black beard; he was a formidable gentleman, with a formidable manner, and he was very exacting about spelling. The gentleman with the black beard attached an inordinate importance to spelling. The gentleman with the black beard was wholly unable to make allowances for the trifling mistakes that will occur in even the best-managed of printing-offices. If the little boy printed: ‘’Twas in Trofolgar’s Bay . . . sung by Mr. Edwin Smith,’ the black-bearded gentleman had no mercy in sending that poor little boy back to do it all over again. But he paid promptly—a severe man, but extremely honourable. There were charity-bazaars too, public invitations, announcements, letter-heads, all bringing grist to the mill. The ‘Elegy for Some Lead Soldiers’ was brought out, and sold for a penny. Once there was a colossal order for a thousand lottery tickets.

The little boy’s ambitions soared. He wrote and printed a tiny book of eight p. ixpages, entitled ‘Black Canyon, or Life in the Far West,’ in which he used all the ‘cuts’ he had somehow accumulated with his type—the story conforming to the illustrations instead of the more common-place way of the illustrations conforming to the text. This work can occasionally be picked up at one of Sotheby’s auctions, and if you can get it for less than twenty-five pounds you are lucky—that is if you are a collector and prize such things. It has risen to the dignity of ‘Davos Booklets; Stevensoniana; excessively rare.’ But its original price was sixpence, and its sale was immediate and gratifying. The little boy discovered that there was much more money to be made from one book than a dozen sets of programmes, and that without any black-bearded gentleman either to tweak his nose when errors crept in.

Louis, as the little boy always called his stepfather, with a familiarity that was p. xmuch criticised by strangers, followed this publishing venture with absorbing interest. Then his own ambitions awakened, and one day, with an affected humility that was most embarrassing, he called at the office, and submitted a manuscript called, ‘Not I, and Other Poems,’ which the firm of Osbourne and Co. gladly accepted on the spot. It was an instantaneous hit, selling out an entire edition of fifty copies.

The publisher was thrilled, and the author was equally jubilant, saying it was the only successful book he had ever written, and jingling his three francs of royalties with an air that made the little boy burst out laughing with delighted pride. In the ensuing enthusiasm another book was planned, and the first poem for it written.

‘If only we could have illustrations,’ said the publisher longingly. But his ‘cuts’ had all been used in ‘Black Canyon, or Life in the Far West.’ Illustrations had to be p. xiput by as a dream impossible of fulfilment. No, not impossible! Louis, who was a man of infinite resourcefulness (he could paint better theatre-scenes than any one could buy), said that he would try to carve some pictures on squares of fretwood. The word fretwood seems as unknown nowadays as the thing itself; it was an extremely thin piece of board with which one was supposed to make works of art with the help of pasted-on patterns, an aggravating little saw, and the patience of Job. . . . Well, Louis cut out a small square of fretwood, and in a deeply-thoughtful manner applied himself to the task. He had only a pocket-knife; real tools came later; but he was impelled by a will to win that carried all before it. After an afternoon of almost suffocating excitement—for the publisher—he completed the engraving that accompanies the poem: ‘Reader, your soul upraise to see.’ But it had yet to be mounted on a wooden block in order to p. xiiraise it to the exact level of the type. At last this was done. A proof was run off. But the impression was unequal. Oh, the disappointment! Author and publisher gazed at each other in misery. But woman’s wit came to the rescue. Why not build it up with cigarette papers? ‘Bravo, Fanny!’ The author set to work, deftly and skilfully. Then more proofs, more cigarette-papers, more running up and down stairs to the little boy’s room, which in temperature hovered about zero. But what was temperature? The thing was a success. The little boy, entranced beyond measure, printed copy after copy from the sheer pleasure of seeing the wet ink magically reproducing the block.

The next day the little boy was sent to a dying Swiss—half the population of Davos were coughing away the remnants of life—who lived with his poverty-stricken family in one room, earning their bread by carving bears. A model block was shown him. p. xiiiCould he reproduce a dozen exactly like it, but in a wood without any grain? The dying Swiss said he could, leaving his bear forthwith, and applying himself to the task. The pinched-face children looked on amazed; the little print of ‘Reader, your soul upraise to see’ was passed from hand to hand with exclamations of astonishment. The dying Swiss gave the little boy the blocks, beautifully and faultlessly finished. Would the little boy care to buy a bear? No, the little boy didn’t. He scurried home through the snow with the precious blocks.

Thus ‘Moral Emblems’ came out; ninety copies, price sixpence. Its reception might almost be called sensational. Wealthy people in the Hotel Belvidere bought as many as three copies apiece. Friends in England wrote back for more. Meanwhile the splendid artist was assiduously busy. He worked like a beaver, saying that it was the best relaxation he had ever found. The little boy once overheard him confiding p. xivto a visitor: ‘I cannot tell you what a Godsend these silly blocks have been to me. When I can write no more, and read no more, and think no more, I can pass whole hours engraving these blocks in blissful contentment.’ These may not have been the actual words, but such at least was their sense.

Thus the second ‘Moral Emblems’ came out; ninety copies, price ninepence. The public welcomed it as heartily as the first, the little boy becoming so prosperous that he accumulated upwards of five pounds. But let it never be said that he spurned the humble mainstay of his beginnings. He printed the weekly programmes as usual, and bore the exactions of the black-bearded gentleman with fortitude. When he made such a trifling mistake, for instance, as ‘The Harp that Once Through Tara’s Hells,’ he dutifully climbed the hill to his freezing room, and ran off a whole fresh set. Two francs fifty was two francs fifty. p. xvEvery business man appreciates the comfort of a small regular order which can be counted on like the clock.

But one day there was no black-bearded gentleman. ‘Oh, he was dead. Had had a hemorrhage three days before and had died.’ I don’t know whether the little boy mourned for him particularly, but it was a shock to lose that two francs fifty centimes. The little boy was worried until he found a lady who had substituted herself for the gentleman with the black beard. She was a very kind lady; you could print anything for that lady, and ‘get away with it’ as Americans say. But she was frolicsome and lacked poise; she was vague about appointments, and had a disheartening way of saying: ‘Oh, bother,’ when the little boy appeared; she would insist on kissing him amid circumstances of the most odious publicity; was so abased a creature besides, that she often marred the programmes by making pen-and-ink corrections. In p. xvicontrast, the little boy looked back on the black-bearded gentleman almost with regret.

Two winters were thus occupied, with incidental education that seemed far less important. The Prussian officer had fortunately died, releasing the little boy from any further study of German. All that he retains of it to-day is the taste of that pocket-knife, and of the Prussian officer’s thumb. Then he was sent to boarding-school in England, or to be precise to a tutor who had half a dozen resident pupils. Time passed; publishing became a memory. Then a long summer holiday found the little boy, now much grown and matured, reunited with his family in Kingussie. The printing-press was there, and business was resumed with enthusiasm. The stepfather, who had made much more progress with engraving than the boy had with Latin, had the blocks and poems all ready for ‘The Graver and the Pen.’

But the printing-press broke down; and p. xviiafter an interval of despair and unavailing attempts to repair it, an amiable old man was found who had a press of his own behind a microscopic general shop. Here ‘The Graver and the Pen’ was printed with what now seems an almost regrettable perfection. The amiable old man was altogether too amiable. He would insist on doing far too much himself, though he had been merely paid a trifling rent for the use of the press. An edition of a hundred copies was printed, of which almost none were sold. The little boy had grown such a big boy that he was ashamed of tradesmanship. He had passed the age when he could take sixpences and ninepences with ease from strangers. New standards were imperceptibly forming, and it pleased him better to see his stepfather give away ‘The Graver and the Pen’ to those worthy of so signal an honour.

In fact ‘The Graver and the Pen’ was the last enterprise of Osbourne and Co. ‘The p. xviiiPirate and the Apothecary’ was projected; three superb illustrations were engraved for it; yet it never saw more light than the typewriter afforded. ‘The Builder’s Doom’ has remained in manuscript until the present time. No illustrations were either drawn or engraved for it. It marked the final decline of a once flourishing business, which in its day had given so much laughter to many people sadly in need of it.

LLOYD OSBOURNE.

|

PAGE |

|

PREFACE |

||

NOT I, AND OTHER POEMS— |

||

I. |

Some like drink |

|

II. |

Here, perfect to a wish |

|

III. |

As seamen on the seas |

|

IV. |

The pamphlet here presented |

|

MORAL EMBLEMS: A COLLECTION OF CUTS AND VERSES— |

||

I. |

See how the children in the print |

|

II. |

Reader, your soul upraise to see |

|

III. |

A PEAK IN DARIEN—Broad-gazing on untrodden lands |

|

IV. |

See in the print how, moved by whim |

|

V. |

Mark, printed on the opposing page |

|

I. |

With storms a-weather, rocks-a-lee |

|

II. |

The careful angler chose his nook |

|

III. |

The Abbot for a walk went out |

|

IV. |

The frozen peaks he once explored |

|

V. |

Industrious pirate! see him sweep |

|

A MARTIAL ELEGY FOR SOME LEAD SOLDIERS— |

||

|

For certain soldiers lately dead |

|

THE GRAVER AND THE PEN: OR, SCENES FROM NATURE, WITH APPROPRIATE VERSES |

||

I. |

PROEM—Unlike the common run of men |

|

II. |

THE PRECARIOUS MILL—Alone above the stream it stands |

|

III. |

THE DISPUTATIOUS PINES—The first pine to the second said |

|

THE TRAMPS—Now long enough had day endured |

||

V. |

THE FOOLHARDY GEOGRAPHER—The howling desert miles around |

|

VI. |

THE ANGLER AND THE CLOWN—The echoing bridge you here may see |

|

MORAL TALES— |

||

I. |

ROBIN AND BEN: OR, THE PIRATE AND THE APOTHECARY—Come, lend me an attentive ear |

|

II. |

THE BUILDER’S DOOM—In eighteen-twenty Deacon Thin |

|

Some like drink

In a pint pot,

Some like to think;

Some not.

Strong Dutch cheese,

Old Kentucky rye,

Some like these;

Not I.

Some like Poe,

And others like Scott,

Some like Mrs. Stowe;

Some not.

Some like to laugh,

Some like to cry,

Some like chaff;

Not I.

Here, perfect to a wish,

We offer, not a dish,

But just the platter:

A book that’s not a book,

A pamphlet in the look

But not the matter.

I own in disarray:

As to the flowers of May

The frosts of Winter;

To my poetic rage,

The smallness of the page

And of the printer.

As seamen on the seas

With song and dance descry

Adown the morning breeze

An islet in the sky:

In Araby the dry,

As o’er the sandy plain

The panting camels cry

To smell the coming rain:

So all things over earth

A common law obey,

And rarity and worth

Pass, arm in arm, away;

And even so, to-day,

The printer and the bard,

In pressless Davos, pray

Their sixpenny reward.

The pamphlet here presented

Was planned and printed by

A printer unindented,

A bard whom all decry.

The author and the printer,

With various kinds of skill,

Concocted it in Winter

At Davos on the Hill.

They burned the nightly taper;

But now the work is ripe—

Observe the costly paper,

Remark the perfect type!

See how the children in the print

Bound on the book to see what’s in ’t!

O, like these pretty babes, may you

Seize and apply this volume too!

And while your eye upon the cuts

With harmless ardour opes and shuts,

Reader, may your immortal mind

To their sage lessons not be blind.

Reader, your soul upraise to see,

In yon fair cut designed by me,

The pauper by the highwayside

Vainly soliciting from pride.

Mark how the Beau with easy air

Contemns the anxious rustic’s prayer,

And, casting a disdainful eye,

Goes gaily gallivanting by.

He from the poor averts his head . . .

He will regret it when he’s dead.

Broad-gazing on untrodden lands,

See where adventurous Cortez stands;

While in the heavens above his head

The Eagle seeks its daily bread.

How aptly fact to fact replies:

Heroes and eagles, hills and skies.

Ye who contemn the fatted slave

Look on this emblem, and be brave.

See in the print how, moved by whim,

Trumpeting Jumbo, great and grim,

Adjusts his trunk, like a cravat,

To noose that individual’s hat.

The sacred Ibis in the distance

Joys to observe his bold resistance.

Mark, printed on the opposing page,

The unfortunate effects of rage.

A man (who might be you or me)

Hurls another into the sea.

Poor soul, his unreflecting act

His future joys will much contract,

And he will spoil his evening toddy

By dwelling on that mangled body.

With storms a-weather, rocks a-lee,

The dancing skiff puts forth to sea.

The lone dissenter in the blast

Recoils before the sight aghast.

But she, although the heavens be black,

Holds on upon the starboard tack,

For why? although to-day she sink,

Still safe she sails in printer’s ink,

And though to-day the seamen drown,

My cut shall hand their memory down.

The careful angler chose his nook

At morning by the lilied brook,

And all the noon his rod he plied

By that romantic riverside.

Soon as the evening hours decline

Tranquilly he’ll return to dine,

And, breathing forth a pious wish,

Will cram his belly full of fish.

The Abbot for a walk went out,

A wealthy cleric, very stout,

And Robin has that Abbot stuck

As the red hunter spears the buck.

The djavel or the javelin

Has, you observe, gone bravely in,

And you may hear that weapon whack

Bang through the middle of his back.

Hence we may learn that Abbots should

Never go walking in a wood.

The frozen peaks he once explored,

But now he’s dead and by the board.

How better far at home to have stayed

Attended by the parlour maid,

And warmed his knees before the fire

Until the hour when folks retire!

So, if you would be spared to friends,

Do nothing but for business ends.

Industrious pirate! see him sweep

The lonely bosom of the deep,

And daily the horizon scan

From Hatteras or Matapan.

Be sure, before that pirate’s old,

He will have made a pot of gold,

And will retire from all his labours

And be respected by his neighbours.

You also scan your life’s horizon

For all that you can clap your eyes on.

For certain soldiers lately dead

Our reverent dirge shall here be said.

Them, when their martial leader called,

No dread preparative appalled;

But leaden-hearted, leaden-heeled,

I marked them steadfast in the field.

Death grimly sided with the foe,

And smote each leaden hero low.

Proudly they perished one by one:

The dread Pea-cannon’s work was done!

O not for them the tears we shed,

Consigned to their congenial lead;

But while unmoved their sleep they take,

We mourn for their dear Captain’s sake,

For their dear Captain, who shall smart

Both in his pocket and his heart,

Who saw his heroes shed their gore,

And lacked a shilling to buy more!

Unlike the common run of men,

I wield a double power to please,

And use the GRAVER and the PEN

With equal aptitude and ease.

I move with that illustrious crew,

The ambidextrous Kings of Art;

And every mortal thing I do

Brings ringing money in the mart.

Hence, in the morning hour, the mead,

The forest and the stream perceive

Me wandering as the muses lead—

Or back returning in the eve.

Two muses like two maiden aunts,

The engraving and the singing muse,

Follow, through all my favourite haunts,

My devious traces in the dews.

p.

38To guide and cheer me, each attends;

Each speeds my rapid task along;

One to my cuts her ardour lends,

One breathes her magic in my song.

Alone above the stream it stands,

Above the iron hill,

The topsy-turvy, tumble-down,

Yet habitable mill.

Still as the ringing saws advance

To slice the humming deal,

All day the pallid miller hears

The thunder of the wheel.

He hears the river plunge and roar

As roars the angry mob;

He feels the solid building quake,

The trusty timbers throb.

All night beside the fire he cowers:

He hears the rafters jar:

O why is he not in a proper house

As decent people are!

p.

42The floors are all aslant, he sees,

The doors are all a-jam;

And from the hook above his head

All crooked swings the ham.

‘Alas,’ he cries and shakes his

head,

‘I see by every sign,

There soon all be the deuce to pay,

With this estate of mine.’

The first pine to the second said:

‘My leaves are black, my branches red;

I stand upon this moor of mine,

A hoar, unconquerable pine.’

The second sniffed and answered:

‘Pooh!

I am as good a pine as you.’

‘Discourteous tree,’ the first

replied,

‘The tempest in my boughs had cried,

The hunter slumbered in my shade,

A hundred years ere you were made.’

The second smiled as he returned:

‘I shall be here when you are burned.’

So far dissension ruled the pair,

Each turned on each a frowning air,

p. 46When

flickering from the bank anigh,

A flight of martens met their eye.

Sometime their course they watched; and then—

They nodded off to sleep again.

Now long enough had day endured,

Or King Apollo Palinured,

Seaward he steers his panting team,

And casts on earth his latest gleam.

But see! the Tramps with jaded eye

Their destined provinces espy.

Long through the hills their way they took,

Long camped beside the mountain brook;

’Tis over; now with rising hope

They pause upon the downward slope,

And as their aching bones they rest,

Their anxious captain scans the west.

So paused Alaric on the Alps

And ciphered up the Roman scalps.

The howling desert miles around,

The tinkling brook the only sound—

Wearied with all his toils and feats,

The traveller dines on potted meats;

On potted meats and princely wines,

Not wisely but too well he dines.

The brindled Tiger loud may roar,

High may the hovering Vulture soar;

Alas! regardless of them all,

Soon shall the empurpled glutton sprawl—

Soon, in the desert’s hushed repose,

Shall trumpet tidings through his nose!

Alack, unwise! that nasal song

Shall be the Ounce’s dinner-gong!

p.

52A blemish in the cut appears;

Alas! it cost both blood and tears.

The glancing graver swerved aside,

Fast flowed the artist’s vital tide!

And now the apologetic bard

Demands indulgence for his pard!

The echoing bridge you here may see,

The pouring lynn, the waving tree,

The eager angler fresh from town—

Above, the contumelious clown.

The angler plies his line and rod,

The clodpole stands with many a nod,—

With many a nod and many a grin,

He sees him cast his engine in.

‘What have you caught?’ the peasant cries.

‘Nothing as yet,’ the Fool replies.

Come, lend me an attentive ear

A startling moral tale to hear,

Of Pirate Rob and Chemist Ben,

And different destinies of men.

Deep in the greenest of the vales

That nestle near the coast of Wales,

The heaving main but just in view,

Robin and Ben together grew,

Together worked and played the fool,

Together shunned the Sunday school,

And pulled each other’s youthful noses

Around the cots, among the roses.

Together but unlike they grew;

Robin was rough, and through and through

Bold, inconsiderate, and manly,

Like some historic Bruce or Stanley.

p. 60Ben had a

mean and servile soul,

He robbed not, though he often stole.

He sang on Sunday in the choir,

And tamely capped the passing Squire.

At length, intolerant of trammels—

Wild as the wild Bithynian camels,

Wild as the wild sea-eagles—Bob

His widowed dam contrives to rob,

And thus with great originality

Effectuates his personality.

Thenceforth his terror-haunted flight

He follows through the starry night;

And with the early morning breeze,

Behold him on the azure seas.

The master of a trading dandy

Hires Robin for a go of brandy;

And all the happy hills of home

Vanish beyond the fields of foam.

Ben, meanwhile, like a tin reflector,

Attended on the worthy rector;

p. 61Opened his

eyes and held his breath,

And flattered to the point of death;

And was at last, by that good fairy,

Apprenticed to the Apothecary.

So Ben, while Robin chose to roam,

A rising chemist was at home,

Tended his shop with learnèd air,

Watered his drugs and oiled his hair,

And gave advice to the unwary,

Like any sleek apothecary.

Meanwhile upon the deep afar

Robin the brave was waging war,

With other tarry desperadoes

About the latitude of Barbadoes.

He knew no touch of craven fear;

His voice was thunder in the cheer;

First, from the main-to’-gallan’ high,

The skulking merchantmen to spy—

p. 62The first

to bound upon the deck,

The last to leave the sinking wreck.

His hand was steel, his word was law,

His mates regarded him with awe.

No pirate in the whole profession

Held a more honourable position.

At length, from years of anxious toil,

Bold Robin seeks his native soil;

Wisely arranges his affairs,

And to his native dale repairs.

The Bristol Swallow sets him down

Beside the well-remembered town.

He sighs, he spits, he marks the scene,

Proudly he treads the village green;

And, free from pettiness and rancour,

Takes lodgings at the ‘Crown and Anchor.’

Strange, when a man so great and good

Once more in his home-country stood,

Strange that the sordid clowns should show

A dull desire to have him go.

His clinging breeks, his tarry hat,

p. 65The way he

swore, the way he spat,

A certain quality of manner,

Alarming like the pirate’s banner—

Something that did not seem to suit all—

Something, O call it bluff, not brutal—

Something at least, howe’er it’s called,

Made Robin generally black-balled.

His soul was wounded; proud and glum,

Alone he sat and swigged his rum,

And took a great distaste to men

Till he encountered Chemist Ben.

Bright was the hour and bright the day

That threw them in each other’s way;

Glad were their mutual salutations,

Long their respective revelations.

Before the inn in sultry weather

They talked of this and that together;

Ben told the tale of his indentures,

And Rob narrated his adventures.

p.

66Last, as the point of greatest weight,

The pair contrasted their estate,

And Robin, like a boastful sailor,

Despised the other for a tailor.

‘See,’ he remarked, ‘with

envy, see

A man with such a fist as me!

Bearded and ringed, and big, and brown,

I sit and toss the stingo down.

Hear the gold jingle in my bag—

All won beneath the Jolly Flag!’

Ben moralised and shook his head:

‘You wanderers earn and eat your bread.

The foe is found, beats or is beaten,

And, either how, the wage is eaten.

And after all your pully-hauly

Your proceeds look uncommon small-ly.

You had done better here to tarry

Apprentice to the Apothecary.

The silent pirates of the shore

Eat and sleep soft, and pocket more

p.

67Than any red, robustious ranger

Who picks his farthings hot from danger.

You clank your guineas on the board;

Mine are with several bankers stored.

You reckon riches on your digits,

You dash in chase of Sals and Bridgets,

You drink and risk delirium tremens,

Your whole estate a common seaman’s!

Regard your friend and school companion,

Soon to be wed to Miss Trevanion

(Smooth, honourable, fat and flowery,

With Heaven knows how much land in dowry),

Look at me—Am I in good case?

Look at my hands, look at my face;

Look at the cloth of my apparel;

Try me and test me, lock and barrel;

And own, to give the devil his due,

I have made more of life than you.

Yet I nor sought nor risked a life;

I shudder at an open knife;

p. 68The

perilous seas I still avoided

And stuck to land whate’er betided.

I had no gold, no marble quarry,

I was a poor apothecary,

Yet here I stand, at thirty-eight,

A man of an assured estate.’

‘Well,’ answered Robin—‘well, and how?’

The smiling chemist tapped his brow.

‘Rob,’ he replied, ‘this throbbing brain

Still worked and hankered after gain.

By day and night, to work my will,

It pounded like a powder mill;

And marking how the world went round

A theory of theft it found.

Here is the key to right and wrong:

Steal little, but steal all day long;

And this invaluable plan

Marks what is called the Honest Man.

When first I served with Doctor Pill,

My hand was ever in the till.

p.

71Now that I am myself a master,

My gains come softer still and faster.

As thus: on Wednesday, a maid

Came to me in the way of trade.

Her mother, an old farmer’s wife,

Required a drug to save her life.

‘At once, my dear, at once,’ I said,

Patted the child upon the head,

Bade her be still a loving daughter,

And filled the bottle up with water.’

‘Well, and the mother?’ Robin cried.

‘O she!’ said Ben—‘I think she died.’

‘Battle and blood, death and disease,

Upon the tainted Tropic seas—

The attendant sharks that chew the cud—

The abhorred scuppers spouting blood—

The untended dead, the Tropic sun—

The thunder of the murderous gun—

p. 72The

cut-throat crew—the Captain’s curse—

The tempest blustering worse and worse—

These have I known and these can stand,

But you—I settle out of hand!’

Out flashed the cutlass, down went Ben

Dead and rotten, there and then.

In eighteen-twenty Deacon Thin

Feu’d the land and fenced it in,

And laid his broad foundations down

About a furlong out of town.

Early and late the work went on.

The carts were toiling ere the dawn;

The mason whistled, the hodman sang;

Early and late the trowels rang;

And Thin himself came day by day

To push the work in every way.

An artful builder, patent king

Of all the local building ring,

Who was there like him in the quarter

For mortifying brick and mortar,

Or pocketing the odd piastre

By substituting lath and plaster?

With plan and two-foot rule in hand,

He by the foreman took his stand,

p. 74With

boisterous voice, with eagle glance

To stamp upon extravagance.

For thrift of bricks and greed of guilders,

He was the Buonaparte of Builders.

The foreman, a desponding creature,

Demurred to here and there a feature:

‘For surely, sir—with your permeession—

Bricks here, sir, in the main parteetion. . . . ’

The builder goggled, gulped, and stared,

The foreman’s services were spared.

Thin would not count among his minions

A man of Wesleyan opinions.

‘Money is money,’ so he said.

‘Crescents are crescents, trade is trade.

Pharaohs and emperors in their seasons

Built, I believe, for different reasons—

Charity, glory, piety, pride—

To pay the men, to please a bride,

To use their stone, to spite their neighbours,

Not for a profit on their labours.

p.

75They built to edify or bewilder;

I build because I am a builder.

Crescent and street and square I build,

Plaster and paint and carve and gild.

Around the city see them stand,

These triumphs of my shaping hand,

With bulging walls, with sinking floors,

With shut, impracticable doors,

Fickle and frail in every part,

And rotten to their inmost heart.

There shall the simple tenant find

Death in the falling window-blind,

Death in the pipe, death in the faucet,

Death in the deadly water-closet!

A day is set for all to die:

Caveat emptor! what care I?’

As to Amphion’s tuneful kit

Thebes rose, with towers encircling it;

As to the Mage’s brandished wand

A spiry palace clove the sand;

p. 76To

Thin’s indomitable financing,

That phantom crescent kept advancing.

When first the brazen bells of churches

Called clerk and parson to their perches,

The worshippers of every sect

Already viewed it with respect;

A second Sunday had not gone

Before the roof was rattled on:

And when the fourth was there, behold

The crescent finished, painted, sold!

The stars proceeded in their courses,

Nature with her subversive forces,

Time, too, the iron-toothed and sinewed,

And the edacious years continued.

Thrones rose and fell; and still the crescent,

Unsanative and now senescent,

A plastered skeleton of lath,

Looked forward to a day of wrath.

In the dead night, the groaning timber

Would jar upon the ear of slumber,

p. 77And, like

Dodona’s talking oak,

Of oracles and judgments spoke.

When to the music fingered well

The feet of children lightly fell,

The sire, who dozed by the decanters,

Started, and dreamed of misadventures.

The rotten brick decayed to dust;

The iron was consumed by rust;

Each tabid and perverted mansion

Hung in the article of declension.

So forty, fifty, sixty passed;

Until, when seventy came at last,

The occupant of number three

Called friends to hold a jubilee.

Wild was the night; the charging rack

Had forced the moon upon her back;

The wind piped up a naval ditty;

And the lamps winked through all the city.

Before that house, where lights were shining,

Corpulent feeders, grossly dining,

p. 78And jolly

clamour, hum and rattle,

Fairly outvoiced the tempest’s battle.

As still his moistened lip he fingered,

The envious policeman lingered;

While far the infernal tempest sped,

And shook the country folks in bed,

And tore the trees and tossed the ships,

He lingered and he licked his lips.

Lo, from within, a hush! the host

Briefly expressed the evening’s toast;

And lo, before the lips were dry,

The Deacon rising to reply!

‘Here in this house which once I built,

Papered and painted, carved and gilt,

And out of which, to my content,

I netted seventy-five per cent.;

Here at this board of jolly neighbours,

I reap the credit of my labours.

These were the days—I will say more—

These were the grand old days of yore!

The builder laboured day and night;

He watched that every brick was right:

p.

79The decent men their utmost did;

And the house rose—a pyramid!

These were the days, our provost knows,

When forty streets and crescents rose,

The fruits of my creative noddle,

All more or less upon a model,

Neat and commodious, cheap and dry,

A perfect pleasure to the eye!

I found this quite a country quarter;

I leave it solid lath and mortar.

In all, I was the single actor—

And am this city’s benefactor!

Since then, alas! both thing and name,

Shoddy across the ocean came—

Shoddy that can the eye bewilder

And makes me blush to meet a builder!

Had this good house, in frame or fixture,

Been tempered by the least admixture

Of that discreditable shoddy,

Should we to-day compound our toddy,

p. 80Or gaily

marry song and laughter

Below its sempiternal rafter?

Not so!’ the Deacon cried.

The mansion

Had marked his fatuous expansion.

The years were full, the house was fated,

The rotten structure crepitated!

A moment, and the silent guests

Sat pallid as their dinner vests.

A moment more and, root and branch,

That mansion fell in avalanche,

Story on story, floor on floor,

Roof, wall and window, joist and door,

Dead weight of damnable disaster,

A cataclysm of lath and plaster.

Siloam did not choose a sinner—

All were not builders at the dinner.

Edinburgh: Printed by T. and A. Constable Ltd.