| Vol. 12. No. 335.] | SATURDAY, OCTOBER 11, 1828. | [PRICE 2d. |

Lavenham, or Lanham, a small town north of Sudbury, was once eminent for its manufactures, when there were eight or nine cloth-halls in the place, inhabited by rich clothiers. The De Veres, Earls of Oxford, whose names are blazoned in our history, held the manor from the reign of Henry I. till that of Elizabeth, and one of the noble family obtained a charter from Edward III. authorizing his tenants at this place to pass toll-free throughout all England, which grant was confirmed by Elizabeth. But the manufacturing celebrity of Lavenham has dwindled to spinning woollen yarn, and making calimancoes and hempen cloth; the opulent clothiers have shuffled off their mortal coil, and proved that “the web of our life is of a mingled yarn, good and ill together.”

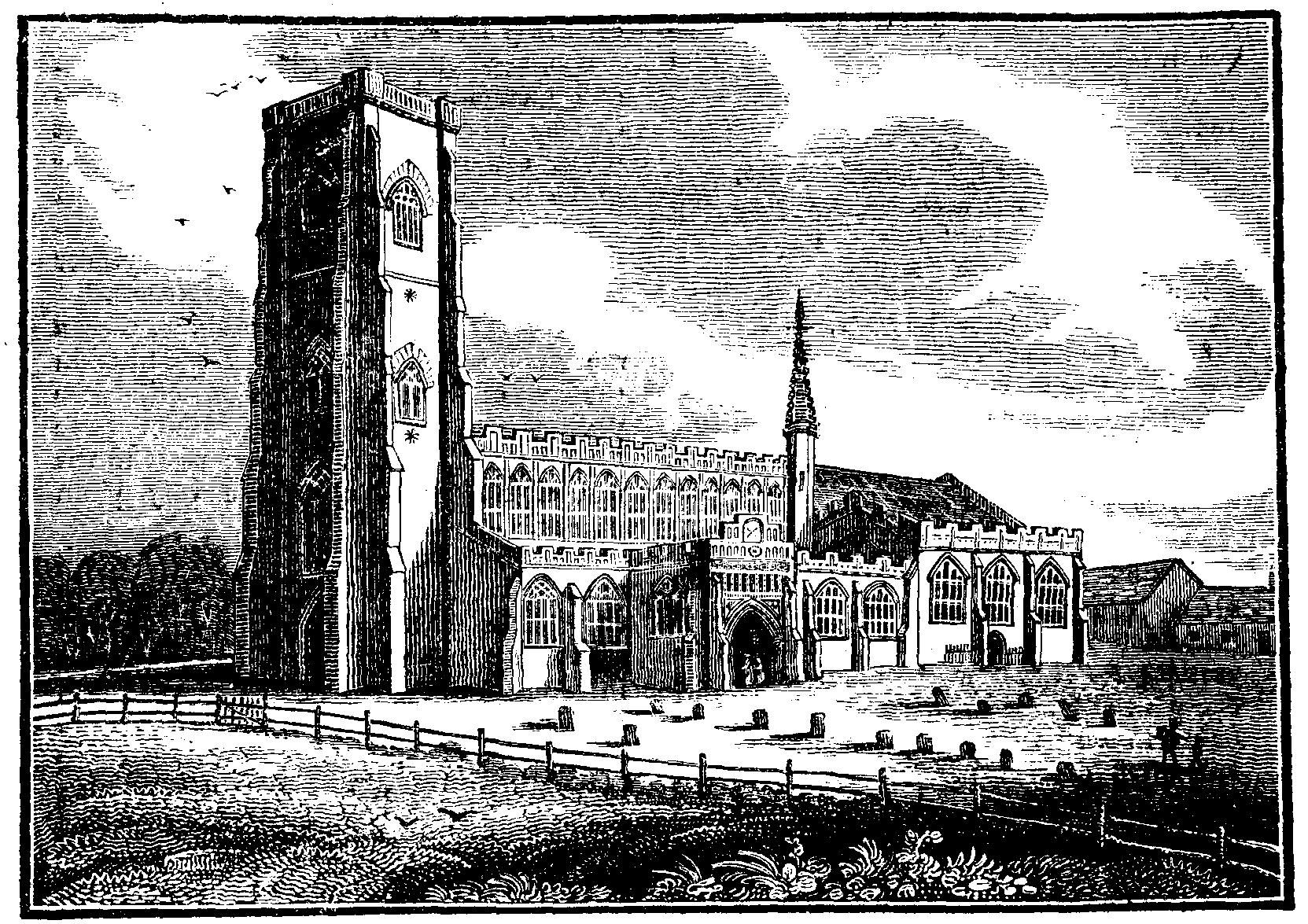

The church of Lavenham is, however, a venerable wreck of antiquity, and is accounted the most beautiful fabric of the kind in Suffolk. It is chiefly built of freestone, the rest being of curious flintwork; its total length is 150 feet, and its breadth 68. From concurrent antiquarian authorities we learn that the church was built by the De Veres, in conjunction with the Springs, wealthy clothiers at Lavenham. This is attested by the different quarterings of their respective arms on the building. The porch is an elegant piece of architecture, very highly enriched with the shields, garters, &c. of many of the most noble families in the kingdom, among which are the letters I.O., probably intended for the initials of John, the 14th Earl of Oxford, who married the daughter of Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk. He is conjectured to have erected this porch.

In the interior, the roof is admirably carved, and the pews belonging to the Earls of Oxford and the Springs, though now much decayed, were highly-finished pieces of Gothic work in wood. Some of the windows are still embellished with painted glass, representing the arms of the De Veres and others. Here also is a costly monument of alabaster and gold, erected to the memory of the Rev. Henry Copinger,1 rector of Lavenham, with alto-relievo [pg 226]figures of the reverend divine and his wife.

In the north aisle is a small mural monument, upon which are represented a man and woman, engraved on brass, kneeling before a table, and three sons and daughters behind them. From the mouth of the man proceeds a label, on which are these words:—In manus tuas dne commendo spiritum meum. Underneath is this inscription, which, like that of the label, is in the old English character:—

Contynuall prayse these lynes in brasse,

Of Allaine Dister here,

A clothier, vertuous while he was

In Lavenham many a yeare.

For as in lyefe he loved best

The poore to clothe and feede,

So with the rich and all the rest

He neighbourlie agreed;

And did appoynte before he dyed,

A special yearlie rent,

Which should be every Whitsontide

Among the poorest spent.

Et obiit Anno Dni 1534.

Although this benefaction is written in brass, the good man’s successors have found enough of the same metal to pervert it; for it is now lost, and no person can give any account of it. It needs not brass to outlive honesty; a mere breath will often destroy her. There are, however, several substantial charities belonging to Lavenham, the disposal of which has fallen into better hands.

In the churchyard is a very old gravestone, which formerly had a Saxon inscription. Kirby, in his account of the monasteries of Suffolk, says that here, on the tomb of one John Wiles, a bachelor, who died in 1694, is this odd jingling epitaph:—

Quod fuit esse quod est, quod non fuit esse quod esse

Esse quod est non esse, quod est non erit esse.

But as the point and oddity may not be directly evident to all, perhaps some of our readers will furnish us with a pithy translation for our next.

F.R. of Lavenham, to whom we are indebted for the drawing of Lavenham Church, informs us that this fine building will shortly undergo a thorough repair.

In No. 333 of the MIRROR, there is an article on the ancient round towers in Scotland and Ireland, in which it is stated that the said towers “have puzzled all antiquarians,” that they are now generally called fire towers and that “they certainly were not belfries.”

I have often thought that antiquarians, and particularly our modern Irish antiquarians, have affected to be puzzled about what, to the rest of mankind, must appear to be evident enough; and this for the purpose of making a parade of their learning, and of astonishing the common reader by the ingenuity of their speculations.

I think I shall be able to show, that a motive of this kind must have operated in the case of these round towers, otherwise “all the antiquarians” could not have been so sadly puzzled about what to the rest of the world appears a very plain matter.

The fact is, that when St. Patrick planted the Christian faith in Ireland, in the middle of the fifth century, (he died A.D. 492,) the practice of hanging bells in church steeples had not begun; and we know from history, that they were first used to summon the people to worship in A.D. 551, by a bishop of Campania; the churches, therefore, that were erected by St. Patrick, (and he built many,) were originally without belfries; and when the use of bells became common, it was judged more expedient to erect a belfry detached from the church, than by sticking it up against the side or end walls, to mar the proportions of the original building.

This is the account of the matter given by the old Irish historians, not one of whom appears to have been aware what “puzzlers” these round towers were to become in after ages; and in a life of St. Kevin, of Glendaloch, (co. Wicklow,) who died A.D. 628, we are told that “the holy bishop did,” a short time before his death, “erect a bell-house (cloig-theach) contiguous to the church formerly erected by him, in which he placed a bell, to the glory of God, and for the good of his own soul.”

I am not unaware, in giving you the above quotation, that “all the antiquarians,” and particularly those of Scotland, have long since decided, that in every matter connected with the ancient history of Ireland, her native historians (many of whom were eye-witnesses of the facts they relate) are on no account to be credited; and that the safest way of dealing with those chroniclers is, in every thing, to take for granted exactly the reverse of [pg 227]what they may at any time assert. In deference, therefore, to such high authorities, I shall waive any advantage which I might claim on account of a quotation from the works of a native historian, and proceed to show, from the reasonableness of the thing itself, that those towers which you state “were certainly never belfries,” were in fact belfries, and were never any thing else.

First.—They are all situated within a few yards of some ancient church, and which church is invariably without a steeple.

Secondly.—It is impossible to conceive, from their slender shape, their great height, and their contiguity to the church, for what other purpose they could have been intended, having, to a spectator inside, who looks up to the top, exactly the appearance of an enormous gun-barrel.

Thirdly.—That in all of them now entire, the holes, for the purpose of receiving the beam to support the bell, remain; and that in one at least, that upon Tory Island, co. Donegal, the beam itself may be seen at this day.

Fourthly, and which appears to me more conclusive than all the rest, that these towers, in every part of Ireland, are, to this day, called in Irish by the name of clogach, (cloig-theach,) that is, bell-house, and that they are never called (in Irish at least) by any other name whatever.

H.S.

P.S. We have heard a good deal of late of a chimney or high tower erected at Bow, by the East London Water Company, on account of its having been erected without any outside scaffolding. It is remarkable, that the traditions of all the people in the neighbourhood of the round towers in Ireland, agree in stating that they were built in the same manner.

Observing in the daily papers an extract from the MIRROR respecting the Belle Savage Inn, I copy you an advertisement out of the London Gazette for February, 1676, respecting that place, which appears to have been called “ancient” so long back as that period.

LEONARD WILSON.

“An antient inn, called the Bell Savage Inn, situate on Ludgate Hill, London, consisting of about 40 rooms, with good cellarage, stabling for 100 horses, and other good accommodations, is to be lett at a yearly rent, or the lease sold, with or without the goods in the house. Enquire at the said inn, or of Mr. Francis Griffith, a scrivener, in Newgate-street, near Newgate, and you may be fully informed.”

A flower beheld a lofty oak,

And thus in mournful accents spoke;

“The verdure of that tree will last,

Till Autumn’s loveliest days are past,

Whilst I with brightest colours crown’d,

Shall soon lie withering on the ground.”

The lofty oak this answer made:

“The fairest flowers the soonest fade.”

Cries Phillis to her shepherd swain,

“Why is Love painted without eyes?”

The youth from flattery can’t refrain,

And to the fair one quick replies:

“Those lovely eyes which now are thine,

In young Love’s face were wont to shine.”

ANNA.

In No. 328 you have given an account of a cromleh in Anglesea. Perhaps it may not be amiss to inform you that the word cromlech, or cromleh, is derived from the Welsh words crom, feminine of crwm, crooked, and lech, a flat stone. There are some cromlehs in Carmarthenshire and Pembrokeshire, which are supposed to have been altars for sacrifices before the Christian era.

W.H.

The Alpine Horn is an instrument made of the bark of the cherry-tree, and like a speaking-trumpet, is used to convey sounds to a great distance. When the last rays of the sun gild the summit of the Alps, the shepherd who inhabits the highest peak of those mountains, takes his horn, and cries with a loud voice, “Praised be the Lord.” As soon as the neighbouring shepherds hear him they leave their huts and repeat these words. The sounds are prolonged many minutes, while the echoes of the mountains, and grottoes of the rocks, repeat the name of God. Imagination cannot picture any thing more solemn, or sublime, than this scene. During the silence that succeeds, the shepherds bend their knees, and pray in the open air, and then retire to their huts to rest. The sun-light gilding the tops of those stupendous mountains, upon which the blue vault of heaven seems to rest, the magnificent scenery around, and the voices of the shepherds sounding from [pg 228]rock to rock the praise of the Almighty, must fill the mind of every traveller with enthusiasm and awe.

INA.

Mr. Corbett has just published a useful little volume, entitled the English Gardener, which is, perhaps, one of the most practical books ever printed. At present we must confine our extracts to a few useful passages; but we purpose a more extended notice of this very interesting volume.

In the work of laying-out, great care ought to be taken with regard to straightness and distances, and particularly as to the squareness of every part. To make lines perpendicular, and perfectly so, is, indeed, no difficult matter when one knows how to do it; but one must know how to do it, before one can do it at all. If the gardener understand this much of geometry, he will do it without any difficulty; but if he only pretend to understand the matter, and begin to walk backward and forward, stretching out lines and cocking his eye, make no bones with him; send for a bricklayer, and see the stumps driven into the ground yourself. The four outside lines being laid down with perfect truth, it must be a bungling fellow indeed that cannot do the rest; but if they be only a little askew, you have a botch in your eye for the rest of your life, and a botch of your own making too. Gardeners seldom want for confidence in their own abilities; but this affair of raising perpendiculars upon a given line is a thing settled in a moment: you have nothing to do but to say to the gardener, “Come, let us see how you do it.” He has but one way in which he can do it; and, if he do not immediately begin to work in that way, pack him off to get a bricklayer, even a botch in which trade will perform the work to the truth of a hair.

I incline to the opinion, that we should try seeds as our ancestors tried witches; not by fire, but by water; and that, following up their practice, we should reprobate and destroy all that do not readily sink.

It is a received opinion, a thing taken for granted, an axiom in horticulture, that melon seed is the better for being old. Mr. Marshall says, that it ought to be “about four years old, though some prefer it much older.” And he afterwards observes, that “if new seed only can be had, it should be carried a week or two in the breeches-pocket, to dry away some of the more watery particles!” If age be a recommendation in rules as well as in melon-seed, this rule has it; for English authors published it, and French authors laughed at it, more than a century past!

Those who can afford to have melons raised in their gardens, can afford to keep a conjuror to raise them; and a conjuror will hardly condescend to follow common sense in his practice. This would be lowering the profession in the eyes of the vulgar, and, which would be very dangerous, in the eyes of his employer. However, a great deal of this stuff is traditionary; and how are we to find the conscience to blame a gardener for errors inculcated by gentlemen of erudition!

I do hope that it is unnecessary for me to say, that sowing according to the moon is wholly absurd and ridiculous; and that it arose solely out of the circumstance, that our forefathers, who could not read, had neither almanack nor calendar to guide them, and who counted by moons and festivals, instead of by months, and days of months.

It is, most likely, owing to negligence that we hardly ever see such a thing as real Brussels sprouts in England; and it is said that it is pretty nearly the same in France, the proper care being taken nowhere, apparently, but in the neighbourhood of Brussels.

After horse-radish has borne seed once or twice, its root becomes hard, brown on the outside, not juicy when it is scraped, and eats more like little chips than like a garden vegetable; so that, at taverns and eating-houses, there frequently seems to be a rivalship on the point of toughness between the horse-radish and the beef-steak; and it would be well if this inconvenient rivalship never discovered itself any where else.

I once ate about three spoonsful at table at Mr. Timothy Brown’s, at Peckham, which had been cooked, I suppose, in the usual way; but I had not long eaten them before my whole body, face, hands, and all, was covered with red spots or pimples, and to such a degree, and coming on so fast, that the doctor who attended the family was sent for. He thought nothing of it, gave me a little draught [pg 229]of some sort, and the pimples went away; but I attributed it then to the mushrooms. The next year, I had mushrooms in my own garden at Botley, and I determined to try the experiment whether they would have the same effect again; but, not liking to run any risk, I took only a teaspoonful, or, rather, a French coffee-spoonful, which is larger than a common teaspoon. They had just the same effect, both as to sensation and outward appearance! From that day to this, I have never touched mushrooms, for I conclude that there must be something poisonous in that which will so quickly produce the effects that I have described, and on a healthy and hale body like mine; and, therefore, I do not advise any one to cultivate these things.

The late king, George the Third, reigned so long, that his birthday formed a sort of season with gardeners; and, ever since I became a man, I can recollect that it was always deemed rather a sign of bad gardening if there were not green peas in the garden fit to gather on the fourth of June. It is curious that green peas are to be had as early in Long Island, and in the seaboard part of the state of New Jersey, as in England, though not sowed there, observe, until very late in April, while ours, to be very early, must be sowed in the month of December or January. It is still more curious, that, such is the effect of habit and tradition, that, even when I was last in America (1819), people talked just as familiarly as in England about having green peas on the king’s birth-day, and were just as ambitious for accomplishing the object; and I remember a gentleman who had been a republican officer during the revolutionary war, who told me that he always got in his garden green peas fit to eat on old Uncle George’s birth-day.

Mr. Platt had a curious mode of making strong cider in America. In the month of January or February, he placed a number of hogsheads of cider upon stands out of doors. The frost turned to ice the upper part of the contents of the hogshead, and a tap drew off from the bottom the part which was not frozen. This was the spirituous part, and was as strong as the very strongest of beer that can be made. The frost had no power over this part; but the lighter part which was at the top it froze into ice. This, when thawed, was weak cider. This method of getting strong cider would not do in a country like this, where the frosts are never sufficiently severe.

When there is frost, all that you have to do, is to keep the apples in a state of total darkness until some days after a complete thaw has come. In America they are frequently frozen as hard as stones; if they thaw in the light, they rot; but if they thaw in darkness, they not only do not rot, but lose very little of their original flavour. This may be new to the English reader; but he may depend upon it that the statement is correct.

To preserve chestnuts, so as to have them to sow in the spring, or to eat through the winter, you must make them perfectly dry after they come out of their green husk; then put them into a box or a barrel mixed with, and covered over by, fine and dry sand, three gallons of sand to one gallon of chestnuts. If there be maggots in any of the chestnuts, they will come out of the chestnuts and work up through the sand to get to the air; and thus you have your chestnuts sweet and sound and fresh.

The Magnum Bonums are fit for nothing but tarts and sweetmeats. Magnum is right enough; but as to bonum, the word has seldom been so completely misapplied.

That which we call currant wine, is neither more nor less than red-looking, weak rum, the strength coming from the sugar; and gooseberry wine is a thing of the same character, and, if the fruit were of no other use than this, one might wish them to be extirpated. People deceive themselves. The thing is called wine, but it is rum; that is to say, an extract from sugar.

The wild pigeons in America live, for about a month, entirely upon the buds of the sugar-maple, and are killed by hundreds of thousands, by persons who erect bough-houses, and remain in a maple wood with guns and powder and shot for that purpose. If we open the craw of one of these little birds, we find in it green stuff of various descriptions, and, generally, more or less of grass, and, therefore, it is a little too much to believe, that, in taking away our buds, they merely relieve us from the insects that would, in time, eat us up. Birds are exceedingly cunning in their generation; but, luckily for us gardeners, they do not know how to distinguish between the report of a gun loaded with powder and shot, and one that is only loaded with powder. Very frequent [pg 230]firing with powder will alarm them so that they will quit the spot, or, at least, be so timid as to become comparatively little mischievous.

There is a class of travelling oddities—the dandy voyageurs of Britain, who, teeming with the proud consciousness of their excellence in comparison with the rest of human kind, swoln with self-sufficiency, float like empty bubbles on the water’s surface, and who seem as if they would break and be dissolved by contact with a vulgar touch. They contrive to swim by means of their air-blown vanity until they come into concussion with some material object, and are at once reduced to their proper level, and for ever annihilated. Their country is London; their domicile Regent-street; thence they would never travel, had they their wills,—not but they would like to see Paris, and move at Longschamps, or admire its beauties in an equipage à D’Aumont; but the horrors attendant upon such an enterprise are too formidable gratuitously to be encountered. It is only when a dip at the Fishmonger’s has been rather too often tried, or Stultz’s billets-doux have been repeated with increasing ardour on the part of the Tailor-lover until he delegates the maintenance of his baronial purse to some dandy-detesting attorney, that they feel it expedient to brave the dangers of sea and land, and, unscrewing their brass spurs, folding up their mustachios in a port-feuille, they hasten them from life and love, and London, and set them down at Meurice’s, the creatures of another element; not less new to all things around them, than all things there are new to them. It was not long since I met one at the table-d’hote of Mr. Money, the hospitable but expensive owner of Les Trois Couronnes, at Vevay, in Switzerland. A large party had assembled, composed of almost every European nation; and we had just commenced our dinner, when we were intruded upon by an Exquisite—a creature something between the human species and a man-milliner—a seven months’ child of fashion—one who had been left an orphan by manliness and taste, and no longer remembered his lost parents. Never can I forget the stare of Baron Pougens, (a Swiss by birth, but a Russian noble) as this specimen of elegance, with mincing step and gait, moved onward, something like a new member tripping it to the table to take his oaths. How he had got so far from Grange’s, I really cannot say; but he had the policy of assurance in his favour; and in his own idea, at the least, was what I heard a poor devil of a candle-snuffer once denominate George Frederic Cooke, the tragedian,—“a rare specimen of exalted humanity;” and the actor was certainly in a rare spirit of exaltation at the moment. His delicate frame was enveloped by a dandy harness, so admirably ordered and adjusted, that he moved in fear of involving his Stultz in the danger of a plait; his kid-clad fingers scarcely supported the weight of his yellow-lined Leghorn; all that was man about him, was in his spurs and mustachios; and, even with them, he seemed there a moth exposed to an Alpine blast,—some mamma’s darling, injudiciously and cruelly abandoned to the risk of cold, in a land where Savory and Moore were yet unheard of, “Beppo in London” wholly unknown, Hoby unesteemed, Gunter misprized, and where George Brummell had never, never trod. After having bestowed a wild inexpressive stare at the cannibals assembled, male and female,—depositing his Vyse, running his digits through his perfumed hair, raising his shirt-collar so as to form an angle of forty-five with his purple Gros de Naples cravat, and applying his gold-turned snuff-box to his nose, Money (who has lived long in England, and speaks its language well) ventured to address him, by demanding if he should place a cover for him. “Sar!—your—appellation—if—you please?” the drawling and affected response of the fop. “Money, Sir.” “the sign of the place—the thing—the auberge?” “The Three Crowns, Sir.” “Money of the country, I presume!—Good—stop—put that down—Mem:” and he took his tablets from his pocket. “Money—Three Crowns—Capital that—will do for Dibdin,—if not, give it Theodore Hook. And the name of your—your town, my man?” “Vevay, Sir!” “And that liquid concern I see from the windar?” “The Lake, Sir—the Lake of Geneva.” “Good gracious! all Geneva?” “Otherwise termed the Leman, Sir.” “Lemon! ha! a sort of gin-punch, I presume—acidulated blue-ruin—Vastly vulgar, by Petersham—only fit for the Cider-cellar, Three Crowns—And that—that—white thing there on the other side of the punch-bowl, Money?” “That is Gin-goulph, Sir.” “Gin-gulp! appropriate certainly, but de-ci-ded-ly—low.” “Will you please, Sir, to dine? dinner is on the table.” “Dinnar! Crockford, be good [pg 231]to us!—Why—why—it is scarcely more than noon, Crowns.—What would Lady Diana say?—But true! I rose at eight—so, I think, I will patronize you, my good fellar—Long journey that from Lowsan—queer name for a place so high;—Vastly bad country this of yours, Crowns.—What are all those stunted poles, like cerceau sticks, placed in the ground? What do you cultivate, Crowns?” “The vine, Sir.” “Wine! wine! dear me! never knew wine grew before. In England it is a manufactory. One moment—pardon—Mem:—Wine grows in—in—” “The Canton de Vaud, Sir.” “In the Canton de Vo,—Tell that to Carbonel and Charles Wright when I go back. Is it Port, pray?” “No, Sir, a thin white wine.” “Thin—white —wine—runs up sticks in said Vo.” “Will you permit me to help you, Sir?” demanded Money, rather impatiently. “What have you, may I ask?” “Bouilli, Sir.” “Bull, what? have you no other beef?—Mem: people living near punch-bowl eat bull beef,” “There is a very nice culotte, Sir, if you prefer it.” “Cu—what, Three Crowns? Culotte!—why, in France, that is—is—inexpressibles—Mem: eat inexpressibles roasted—Breaches of taste, by Reay—the savages!—that will do for the Bedford—mention it to Joy—the brutes!—Neither bull nor breeches, thank you inexpressibly, Money.” “A Blanquette de Veau, then, if you like, Sir.” “Blanket de Vo! a cover to lay, indeed, Crowns. Mem: inhabitants of Gin stew blankets of the country, and then eat them—the Alsatians!” “Poultry, Sir, if you desire it.” “Ah! some hopes there, Money—What is that you hold?” “A Poularde, Sir.” “Obliged, Crowns—no Pull-hard thank you, devilish tough I doubt—Mem: fowl called Pull-hard at Gin—Try again, my man.” “A Dindon and dans son jus, Sir.” “Ding dong and a dancing Jew!—sort of stewed Rothschild, I suppose—Well! if I don’t mean exactly to starve, I fear I must even venture on the Jew.—Not bad, by Long—Mem: Dancing Jews in sauce capital—mention that to young G——, of the Tenth.” The business of mastication arrested for a moment the sapient remarks of the Impayable, until our notice was again attracted by his leaping from his chair, and cutting divers capers around the room, which, if they did honour to his agility, harmonized but ill with the precisian starchness of his habiliments, the order whereof was grievously derangé by his antics.—“Water! water! Crowns.—I have emptied the vinegar cruet by mistake—Oh Lud! can scarcely breathe—Water! Crowns, water! in mercy.” “It was the Vin du Pays, I assure you, Sir,—nothing else upon my word.” “Water! water! oh—here—here I have it.” “No, Sir; I beg—that is Eau de Cerises—Kirschen-wasser—Cherry water.”—“Any—any water will do,”—and, ere Money could arrest his hand, the water-sembling but fiery fluid, the ardent spirit of the cherry, had been swallowed at a draught. He gaped and gasped for breath—he groaned and writhed in torment—and, borne out in the arms of Crowns and his men, the spirit-stirring Dandy was removed to bed, whence he arose to return, without delay, to London by the shortest possible road, even with the fear of another fieri facias before his eyes, to descant on vinous acidities, Gin Lakes, and the liver-consuming Spa of Vo.—New Monthly Mag.

If from our purse all coin we spurn

But gold, we may from mart return.

Nor purchase what we’re seeking;

And if in parties we must talk

Nothing but sterling wit, we balk

All interchange of speaking.

Small talk is like small change; it flows

A thousand different ways, and throws

Thoughts into circulation,

Of trivial value each, but which

Combin’d, make social converse rich

In cheerful animation.

As bows unbent recruit their force.

Our minds by frivolous discourse

We strengthen and embellish,

“Let us be wise,” said Plato once,

When talking nonsense—“yonder dunce

For folly has no relish.”

The solemn bore, who holds that speech

Was given us to prose and preach,

And not for lighter usance,

Straight should be sent to Coventry;

Or omnium concensu, be

Indicted as a nuisance.

Though dull the joke, ‘tis wise to laugh,

Parch’d be the tongue that cannot quaff

Save from a golden chalice;

Let jesters seek no other plea,

Than that their merriment be free

From bitterness and malice.

Silence at once the ribald clown.

And check with an indignant frown

The scurrilous backbiter;

But speed good-humour as it runs,

Be even tolerant of puns,

And every mirth-exciter.

The wag who even fails may claim

Indulgence for his cheerful aim;

We should applaud, not hiss him;

This is a pardon which we grant,

(The Latin gives the rhime I want,)

“Et petimus vicissim.”

Ibid.

Your love is like the gnats, John,

That hum at close of day:

That sting, and leave a scar behind,

Then sing and fly away.

Weekly Review.

The Portuguese mills have a very extraordinary appearance, owing chiefly to the shape of their arms or sails, the construction of which differs from that of all other mills in Europe.

Villanova de Milfontès is a little town, situated at the mouth of a little river which flows from the Sierra de Monchique. Formerly there was a port here, formed by a little bay, and defended by a castle, which might have been of some importance at a period when the Moors made such frequent incursions upon the coasts of the kingdom of the Algarves; at present a dangerous bar and banks of quicksands hinder any vessels larger than small fishing-boats from entering the port.

Fig trees from 20 to 30 feet high overshadow the moat of the castle, and aloes plants as luxuriant as those of Andalusia, shoot up their stems crowned with flowers along the shores of the bay, and by the sides of the roads, whose windings are lost amongst the gardens that surround Milfontès.

We have seen Mr. HAYDON’S PICTURE of the Chairing of the Members; but must defer our description till the next number of the MIRROR. In the meantime we recommend our readers to visit the exhibition, so that they may compare notes with us. “The Chairing” is even superior to the “Election.”

In the year 1437, an obscure man, Nicola di Rienzi, conceived the project of restoring Rome, then in degradation and wretchedness, not only to good order, but even to her ancient greatness. He had received an education beyond his birth, and nourished his mind with the study of the best writers. After many harangues to the people, which the nobility, blinded by their self-confidence, did not attempt to repress, Rienzi suddenly excited an insurrection, and obtained complete success. He was placed at the head of a new government, with the title of Tribune, and with almost unlimited power. The first effects of this revolution were wonderful. All the nobles submitted, though with great reluctance; the roads were cleared of robbers; tranquillity was restored at home; some severe examples of justice intimidated offenders; and the tribune was regarded by all the people as the destined restorer of Rome and Italy. Most of the Italian republics, and some of the princes, sent embassadors, and seemed to recognise pretensions which were tolerably ostentatious. The King of Hungary and Queen [pg 233]of Naples submitted their quarrel to the arbitration of Rienzi, who did not, however, undertake to decide it. But this sudden exaltation intoxicated his understanding, and exhibited feelings entirely incompatible with his elevated condition. If Rienzi had lived in our own age, his talents, which were really great, would have found their proper orbit, for his character was one not unusual among literary politicians; a combination of knowledge, eloquence, and enthusiasm for ideal excellence, with vanity, inexperience of mankind, unsteadiness, and physical timidity. As these latter qualities became conspicuous, they eclipsed his virtues, and caused his benefits to be forgotten: he was compelled to abdicate his government, and retire into exile. After several years, some of which he passed in the prison of Avignon, Rienzi was brought back to Rome, with the title of senator, and under the command of the legate. It was supposed that the Romans, who had returned to their habits of insubordination, would gladly submit to their favourite tribune. And this proved the case for a few months; but after that time they ceased altogether to respect a man who so little respected himself in accepting a station where he could no longer be free, and Rienzi was killed in a sedition.

“The doors of the capitol,” says Gibbon, “were destroyed with axes and with fire; and while the senator attempted to escape in a plebeian garb, he was dragged to the platform of his palace, the fatal scene of his judgments and executions;” and after enduring the protracted tortures of suspense and insult, he was pierced with a thousand daggers, amidst the execrations of the people.

At Rome is still shown a curious old brick dwelling, distinguished by the appellation of “The House of Pilate,” but known to be the house of Rienzi. It is exactly such as would please the known taste of the Roman tribune, being composed of heterogeneous scraps of ancient marble, patched up with barbarous brick pilasters of his own age; affording an apt exemplification of his own character, in which piecemeal fragments of Roman virtue, and attachment to feudal state—abstract love of liberty, and practice of tyranny—formed as incongruous a compound.

A pamphlet, entitled, A Call upon the People of Great Britain and Ireland, has lately reached us; but as its contents are purely political, we must content ourselves with a few historical data. Thus, of the 127 years from the Revolution to 1815, 65 have passed in war, during which “high trials of right,” 2,023½ millions have been expended in seven wars. Of these we give a synopsis:

| Lasted Years. |

Cost in Millions. |

|

| War of the Revolution, 1688-1697 | 9 | 36 |

| War of Spanish Succession, 1702-1713 | 11 | 62½ |

| Spanish War, 1739-1748 | 9 | 54 |

| Seven Years’ War, 1756-1763 | 7 | 112 |

| American War, 1775-1783 | 8 | 136 |

| War of the French Revolution, 1793-1802 | 9 | 464 |

| War against Napoleon, 1803-1815 | 12 | 1159 |

Of this expenditure we borrowed 834½ millions, and raised by taxes 1,189 millions. During the 127 years, the annual poor-rates rose from ¾ of a million to 5½ millions, and the price of wheat from 44s. to 92s. 8d. per quarter.

But it is time to clear the table, for it “strikes us more dead than a great reckoning in a little room.”

Our thanks are due to Mr. Dillon for a copy of the second edition of his Popular Premises Examined, which we have read with considerable interest. The “opinions” are as popularly examined as is consistent with philosophical inquiry; but they are still not just calculated for the majority of the readers of the MIRROR. We, nevertheless, make one short extract, which will be acceptable to every well-regulated mind; and characteristic of the tone of good-feeling throughout Mr. Dillon’s important little treatise.

“The spheres which we behold may each have their variety of intelligent ‘being,’ as links in nature’s beautiful chain, connecting the smallest insect with the incomprehensible and immutable God. The beautiful variety we see in his works portrays His will, and we are justified in following this variety up to His throne. His attributes of love and joy beam forth from the heavens, and are reflected from every species of sensitive being. All have different capacities for enjoyment, all have pleasure and delight, from the lark warbling above her nest, to man walking in the resplendent gardens of heaven, and enjoying, under the smiling approbation of Providence, the flowers and fruits that surround him.”

No man without the support and encouragement of friends, and having proper opportunities thrown in his way, is able to rise at once from obscurity, by the force of his own unassisted genius.—Pliny’s Letters.

Constitute a sort of nobility of the Jews, and it is the first object of each parent that his sons shall, if possible, attain it. When, therefore, a boy displays a peculiarly acute mind and studious habits, he is placed before the twelve folio volumes of the Talmud, and its legion of commentaries and epitomes, which he is made to pore over with an intenseness which engrosses his faculties entirely, and often leaves him in mind, and occasionally in body, fit for nothing else; and so vigilant and jealous a discipline is exercised so to fence him round as to secure his being exclusively Talmudical, and destitute of every other learning and knowledge whatever, that one individual has lately met with three young men, educated as rabbis, who were born and lived to manhood in the middle of Poland, and yet knew not one word of its language. To speak Polish on the Sabbath is to profane it—so say the orthodox Polish Jews. If at the age of fourteen or fifteen years, or still earlier, (for the Jew ceases to be a minor when thirteen years old,) this Talmudical student realizes the hopes of his childhood, he becomes an object of research among the wealthy Jews, who are anxious that their daughters shall attain the honour of becoming the brides of these embryo santons; and often, when he is thus young, and his bride still younger, the marriage is completed.

Jacob de Castro was one of the first members of the Corporation of Surgeons, after their separation from the barbers in the year 1745. On which occasion Bonnel Thornton suggested “Tollite Barberum” for their motto.

The barber-surgeons had a by-law, by which they levied ten pounds on any person who should dissect a body out of their hall without leave. The separation did away this and other impediments to the improvement of surgery in England, which previously had been chiefly cultivated in France. The barber-surgeon in those days was known by his pole, the reason of which is sought for by a querist in “The British Apollo,” fol. Lond. 1708, No. 3:—

“I’de know why he that selleth ale

Hangs out a chequer’d part per pale;

And why a barber at port-hole

Puts forth a party-colour’d pole?”

ANSWER.

“In ancient Rome, when men lov’d fighting,

And wounds and scars took much delight in,

Man-menders then had noble pay,

Which we call surgeons to this day.

‘Twas order’d that a huge long pole,

With basen deck’d, should grace the hole.

To guide the wounded, who unlopt

Could walk, on stumps the others hopt;

But, when they ended all their wars,

And men grew out of love with scars,

Their trade decaying, to keep swimming,

They join’d the other trade of trimming;

And to their poles, to publish either,

Thus twisted both their trades together.”

From Brand’s “History of Newcastle,” we find that there was a branch of the fraternity in that place; as at a meeting, 1742, of the barber-chirurgeons, it was ordered, that they should not shave on a Sunday, and “that no brother shave John Robinson, till he pay what he owes to Robert Shafto.” Speaking of the “grosse ignorance of the barbers,” a facetious author says, “This puts me in minde of a barber who, after he had cupped me, (as the physitian had prescribed,) to turn a catarrhe, asked me if I would be sacrificed. Scarified? said I; did the physitian tell you any such thing? No, (quoth he,) but I have sacrificed many, who have been the better for it. Then musing a little with myselfe, I told him, Surely, sir, you mistake yourself—you meane scarified. O, sir, by your favour, (quoth he,) I have ever heard it called sacrificing; and as for scarifying, I never heard of it before. In a word, I could by no means perswade him but that it was the barber’s office to sacrifice men. Since which time I never saw any man in a barber’s hands, but that sacrificing barber came to my mind.”—Wadd’s Nugæ.

Sir Theodore Mayerne may be considered one of the earliest reformers of the practice of physic. He left some papers written in elegant Latin, in the Ashmolean Collection, which contain many curious particulars relative to the first invention of several medicines, and the state of physic at that period. Petitot, the celebrated enameller, owed his success in colouring to some chemical secrets communicated to him by Sir Theodore.

He was a voluminous writer, and, among others, wrote a book of receipts in cookery. Many were the good and savoury things invented by Sir Theodore; his maxims, and those of Sir John Hill, under the cloak of Mrs. Glasse, might have directed our stew-pans to this hour, but for the more scientific instructions of the renowned Mrs. Rundall, or of the still more scientific Dr. Kitchiner, who has verified the old adage, that the “Kitchen is the handmaid to Physic;” and if it be true that we are to regard a “good cook as in the nature of a good physician,” then is Dr. Kitchiner the best physician that ever condescended to treat “de re culinaria.”

Sir Theodore may, in a degree, be said [pg 235]to have fallen a victim to bad cookery; for he is reported to have died of the effects of bad wine, which he drank at a tavern in the Strand. He foretold it would be fatal, and died, as it were, out of compliment to his own prediction.—Ibid.

We would say of coffee-making in England, as Hamlet did of acting, “Oh, reform it altogether.” Accordingly, the publication of a pleasant trifle, under the above name, is not ill-timed. Like all our modern farces, it is from the French, and as the translator informs us, the editor of the original is “of the Café de Foi, at Paris.”

It opens with the History of Coffee, from its discovery by a monk in the 17th century, to the establishment of cafés in Paris, of which we have a brief notice, with additions by the translator.

Next is “the French method of making coffee, with the roasting, grinding, and infusion processes”; and an interesting chapter on “coffee in the East.” Under the “medicinal effects” we have the following, which is full of the gaiete de coeur of French writing:—

Influence of Coffee upon the Spirits. If coffee had been known among the Greeks and Romans, Homer would have taken his lyre to celebrate its virtues; Horace and Juvenal would have immortalized it in their verses; Diogenes would not have concealed his ill-humour in a tub, but would have drunk of this divine liquid, and have directly found the honest man he sought for; it would have made Heraclitus merry; and with what odes would it have inspired the muse of Anacreon!

In short, who can enumerate the wonderful effects of coffee!

Seest thou that morose figure, that pale complexion, those deadened eyes, and faded lips? It is a lamentable fit of spleen. The whole faculty have been sent for, but their art is unavailing. She is given over. Happily one of her friends counsels her against despair, prescribes a few cups of Moka, and the dying patient, being restored to health, concludes with anathematizing the faculty, who would thus have sacrificed her life.

The complexion of this young girl was, as the poets would say, of lilies and roses; never was there a form more celestial, or one more gifted with life and vigour.

Arrived at this stage, so fatal to the existence of females, the young girl sickened, lost her colour, and those cheeks, but yesterday so brilliant, were dull and heavy. “Travelling,” said one; “a husband,” said another; “coffee, coffee,” replied a doctor. Coffee flowed in abundance, and then the drooping flower revived, and flourished again.

O! all ye who have essayed at rhyme, say if you have not often derived your happiest thoughts from this inspiring beverage. Delille has some beautiful lines, and Berchoux, in his poem of Gastronomie, has a pompous eulogium on its virtues.

Coffee occupies a grand place in the life and pursuits of the gastronomer. Oft-times on leaving table his head aches and becomes heavy; he rises with pain; the savoury smells of viands, the flame of wax-lights, and the imperceptible gases which escape from innumerable wines and liqueurs, have produced around him a kind of mist or shade, equal to what the poet calls darkness visible. Coffee is quickly brought; our gastronomer inhales the aroma, sips drop by drop this ambrosian beverage, and his head already lightened, he walks with his accustomed vigour. What gaiety smiles in his countenance! the liveliest sallies of wit flow unnumbered from his lips; he is another being—a new man; but coffee alone has produced this regeneration. The late Doctor Gastaldi, who was an excellent table companion, used to say that he should have died ten times of indigestion if he had not accustomed himself to take coffee after dinner.

Would you then sleep tranquilly after your meal, and never fear those dreams which are so fatal to gourmands, quaff your coffee; it will fall like dew upon your lips, and sweetly temper with all those juices which oppress your exhausted stomach. If you can, drink your coffee without sugar, for then it preserves its natural flavour, and is much more efficacious than when mixed with other ingredients. Laugh at the doctors who tell you that hot coffee irritates the stomach and injures the nerves; tell them that Voltaire, Fontenelle, Stacey, and Fourcroy, who were great coffee-drinkers, lived to a good old age.

The brochure, for such it is, is wound up with “the natural history of coffee,” and an appendix of “English receipts,” &c.

A work of extraordinary and soul-stirring [pg 236] interest has lately appeared on the Revolutions of South America. It is entitled “Memoirs of General Miller, in the Service of the Republic of Peru,” and is compiled from private letters, journals, and recollections, by the brother of the general. From this portion of the work we gather that William Miller, the companion in arms of San Martin and Bolivar, was born in Kent, in 1795. He served with the British army in Spain and America, from 1811 till the peace of 1815. In 1816 and 1817, he devoted some attention to mercantile affairs; but being of an ardent spirit he finally resolved to engage as a candidate for military honour in the struggle in South America. Colombia was overrun with adventurers; and Miller directed his course to the river La Plata. He left England in August, 1817, when he was under twenty-two years of age, and landed at Buenos Ayres in the September following. In a month after, he received a captain’s commission in the army of the Andes. In the beginning of 1818, captain Miller set out for the army of San Martin, and crossed the Andes by the pass of Uspallata. He soon joined his companions in arms. His first military enterprise was unsuccessful, but a notice of it will give our readers a faint idea of the perils of a campaign in the mountainous regions of South America. Miller, it appears, was on his march towards the capital of Chile; the artillery consisted of ten six-pounders, to this branch of the service his attention was, of course, devoted. The incident occurred in crossing the Maypo, a torrent which rushes from a gorge of the Andes.

The only bridge over it is made of what may be called hide cables. It is about two hundred and fifty feet long, and just wide enough to admit a carriage. It is upon the principle of suspension, and constructed where the banks of the river are so bold as to furnish natural piers. The figure of the bridge is nearly that of an inverted arch. Formed of elastic materials, it rocks a good deal when passengers go over it. The infantry, however, passed upon the present occasion without the smallest difficulty. The cavalry also passed without any accident by going a few at a time, and each man leading his horse. When the artillery came up, doubts were entertained of the possibility of getting it over. The general had placed himself on an eminence, to see his army file to the opposite side of the river. A consultation was held upon the practicability of passing the guns. Captain Miller volunteered to conduct the first gun. The limber was taken off, and drag ropes were fastened to the washers, to prevent the gun from descending too rapidly. The trail, carried foremost, was held up by two gunners, but, notwithstanding every precaution, the bridge swung from side to side, and the carriage acquired so much velocity, that the gunners who held up the trail, assisted by captain Miller, lost their equilibrium, and the gun upset. The carriage, becoming entangled in the thong balustrade, was prevented from falling into the river, but the platform of the bridge acquired an inclination almost perpendicular, and all upon it were obliged to cling to whatever they could catch hold of to save themselves from being precipitated into the torrent, which rolled and foamed sixty feet below. For some little time none dared go to the relief of the party thus suspended, because it was supposed that the bridge would snap asunder, and it was expected that in a few moments all would drop into the abyss beneath. As nothing material gave way, the alarm on shore subsided, and two or three men ventured on the bridge to give assistance. The gun was dismounted with great difficulty, the carriage dismantled, and conveyed piecemeal to the opposite shore. The rest of the artillery then made a detour, and crossed at a ford four or five leagues lower down the river.

Miller soon became advanced to the rank of brevet-major: in November, 1818, he joined Lord Cochrane, who took the command of the naval forces of Chile, and was accompanied by major Miller, as commander of the marines, in nearly all his expeditions. Lord Cochrane failing in his first attack on Callao, resolved to fit out fire-ships, and a laboratory was accordingly formed under the superintendance of major Miller. Here our gallant adventurer was nearly destroyed by an accidental explosion; and in an attack shortly afterwards at Pisco, he was desperately wounded, so that his life was for seventeen days despaired of.

In the capture of Valdivia, one of the bravest exploits of modern warfare, Miller acted a distinguished part, and narrowly escaped destruction, a ball passing through his hat, and grazing the crown of his head. The narrative of this glorious scene is unfortunately too long for transference to our columns, and the omission of any of the details would interfere with its glowing interest.

Miller was again wounded in an unsuccessful attempt, under Lord Cochrane, to capture the Island of Chiloe. In June, 1820, he was made lieutenant-colonel of the eighth battalion of Buenos Ayres, and in the August following, he embarked for Valparaiso, with his battalion, [pg 237] forming a part of the liberating army of Peru. They made the passage to Pisco, a distance of 1,500 miles, in fifteen days; and from this point commenced that series of sanguinary conflicts which terminated, in five years, in the complete liberation of the country of the Incas. During the land operations was Lord Cochrane’s triumphant capture of the Spanish frigate, the Esmeralda, in the fort of Callao, which is briefly but vividly told.

Early in 1821, lieutenant-colonel Miller abandoned Pasco, and re-embarked for the fort of Arica; and after a hair-breadth escape, landed ten leagues north of that point. The colonel now advanced with his little army of 400 men into the country, where he routed the royalist troops, and in a fortnight killed or captured more than 600 Spaniards. In 1822, he was promoted to the rank of colonel, and the civil and military government of an extensive district in Peru; in which year also he was engaged in several important battles. In the beginning of 1823, with only a company of caçadores, he harassed the royalists for several months; and so alarmed the enemy by the rapidity of his movements, that he often passed the hostile division, of a thousand men, without their daring to attack him. Of the country in which these operations were carried on, the general gives a frightful picture.

In 1823, colonel Miller, was promoted to the rank of general of brigade, and in the same year he became chief of the staff of the Peruvian army. In 1824, he was introduced to Bolivar. On the 13th of June he crossed the Andes to take the command of 1,500 montoneros (a body of men very similar to the Guerillas of Spain,) who occupied the country round Pasco. The difficulties of this service, and the perils of a campaign in the Andes, may be well inferred from the following passages:—

It often occurred during the campaign of 1824, that the cavalry being in the rear, were, by a succession of various obstructions, prevented from accomplishing the day’s march before nightfall. It then became necessary for every man to dismount, and to lead the two animals in his charge, to avoid going astray, or tumbling headlong down the most frightful precipices. But the utmost precaution did not always prevent the corps from losing their way. Sometimes men, at the head of a battalion, would continue to follow the windings of a deafening torrent, instead of turning abruptly to the right or left, up some rocky acclivity, over which lay their proper course; whilst others who chanced to be right, would pursue the proper track. The line was so drawn out, that there were unavoidably many intervals, and it was easy for such mistakes to occur, although trumpeters were placed at regular distances expressly to prevent separation. One party was frequently heard hallowing from an apparently fathomless ravine, to their comrades passing over some high projecting summit, to know if they were going right. These would answer with their trumpets; but it often occurred that both parties had lost their road. The frequent sound of trumpets along the broken line—the shouting of officers to their men at a distance—the neighing of horses, and the braying of mules, both men and animals being alike anxious to reach a place of rest, produced a strange and fearful concert, echoed, in the darkness of the night, from the horrid solitude of the Andes. After many fruitless attempts to discover the proper route, a halt until daybreak was usually the last resource. The sufferings of the men and animals on those occasions were extreme. The thermometer was generally below the freezing point, amidst which they were sometimes overtaken by terrific snow-storms. These difficulties and hardships were not so severely felt by the infantry, for, unincumbered with the charge of horses, it was an easy matter for them to turn back, whereas it was often impossible for the cavalry to do so, the path on the mountain-side being generally too narrow to admit of horses turning round. It happened more than once, that the squadron in front, having ascertained that it had taken a wrong direction, was nevertheless compelled to advance until it reached some open spot, where the men were enabled to assemble, and wait for the hindmost of their comrades, and then retrace their steps. After having pursued this plan, the troops have met another squadron following the same track; and, under such circumstances, it has required hours for either to effect a countermarch. In this complicated operation many an animal was hurled down the precipice and dashed to pieces, nor did their riders always escape a similar fate.

In the mountainous regions of the interior, nature presents difficulties which, though of a different description, are equally as appalling as those experienced on the coast. The sheds erected at pascanas (or halting places) in the vast unpeopled tracts of the bleak mountain districts, and on the table lands, were inadequate to afford shelter to more than a small number, so that the greater part of the troops were obliged to bivouac sometimes in places where the thermometer [pg 238] falls every night considerably below the freezing point, and this throughout the year; whereas it often rises at noon, in the same place, to 90 degrees. It may be readily imagined what must have been the sufferings of men, born in, or accustomed to, the sultry temperature of Truxillo, Guayaquil, Panama, or Cartagena. The difficulty of respiration, called in some places la puna, and in others el siroche, experienced in those parts of the Andes which most abound in metals, was so great at times, that, whilst on the march, whole battalions would sink down, as if by magic, and it would have been inflicting death to have attempted to oblige them to proceed until they had rested and recovered themselves. In many cases life was solely preserved by opening the temporal artery. This sudden difficulty of respiration is supposed to be caused by occasional exhalations of metalliferous vapour, which, being inhaled into the lungs, causes a strong feeling of suffocation.

During certain months of the year, tremendous hail-storms occur. They have fallen with such violence that the army has been obliged to halt, and the men being compelled to hold up their knapsacks to protect their faces, have had their hands so severely bruised and cut by large hail-stones as to bleed copiously.

Thunder-storms are also particularly severe in the elevated regions. The electric fluid is seen to fall around, in a manner unknown in other parts of the world, and frequently causes loss of life. Such storms have often burst at some distance below their feet, as the army climbed the lofty ridges of the Andes.

The distressing fatigues of the most difficult marches in Europe cannot perhaps be compared to those which the patriot soldiers underwent in the campaign of 1824. From Caxamarca (memorable for the seizure and death of Atuhualpa) to Cuzco, the whole line of the road (with the exception of the plain between Pasco and the vicinity of Tarma, twenty leagues in extent, and the valley of Xauxa) presents a continuation of rugged and fatiguing ascents and declivities. That these difficulties do not diminish between Cuzco and Potosi may be inferred from the following fact:—

When general Cordova’s division marched from Cuzco to Puno, it halted at Santa Rosa. During the night there was a heavy fall of snow. They continued their march the next morning. The effects of the rays of the sun reflected from the snow upon the eyes, produces a disease, which the Peruvians call surumpi. It occasions blindness, accompanied by excruciating pains. A pimple forms in the eye-ball, and causes an itching, pricking pain, as though needles were continually piercing it. The temporary loss of sight is occasioned by the impossibility of opening the eye-lids for a single moment, the smallest ray of light being absolutely insupportable. The only relief is a poultice of snow, but as that melts away the tortures return. With the exception of twenty men and the guides, who knew how to guard against the calamity, the whole division were struck blind three leagues distant from the nearest human habitation. The guides galloped on to a village in advance, and brought out a hundred Indians to assist in leading the men. Many of the sufferers, maddened by pain, had strayed away from the column, and perished before the return of the guides, who, together with the Indians, took charge of long files of the poor sightless soldiers, clinging to each other with agonized and desperate grasp. During their dreary march by a rugged mountain path, several fell down precipices, and were never heard of more. General Miller suffered only fifteen hours from the surumpi, but the complaint usually continues two days. Out of three thousand men, General Cordova lost above a hundred. The regiment most affected was the voltigeros (formerly Numancia), which had marched by land from Caracas, a distance of upwards of two thousand leagues.

General Miller’s share in the triumph of Junin was witnessed by Bolivar, in August, 1824; and at the victory of Ayacucho, which terminated the war in Peru, general Miller was foremost in the thickest of the fight.

We are now drawing near to the close of our outline of the general’s brilliant career. At the conclusion of the war in 1825, he was appointed prefect of the department of Potosi, with a population of 300,000 souls. He was going on prosperously in his labours of peace, in improving the condition of the natives, who had for three centuries been writhing under the most infamous oppression, when his health required that he should visit Europe. In October, 1825, he resigned his honourable office, and obtained leave of absence to return to his native country, bringing with him an unsolicited testimonial from Bolivar, of his heroism in the campaign of 1824. General Miller is now in England, and in circles where his merit is known, he is received with the highest respect.

In our hasty sketch, we have glanced at only a few of the difficulties with which General Miller was beset in his several enterprises [pg 239] in the cause of South American independence. His career, though extending but to seven years, is one of unparalleled interest, as well to the general reader, as to the more calculating observer of the rise and progress of infant liberty. His exploits have none of the daring or bravado of mere adventures, but they are examples of sterling courage which have few parallels in the annals of modern warfare. On his quitting Potosi for England, it is mentioned that he was overwhelmed with testimonials of popular affection. We live in too advanced a state of refinement to appreciate the ecstasy which his labours in the great and glorious cause must have inspired among the native population of the scene of these exploits; but as a fellow-countryman, we have reason to be proud of his name, and of the high rank it will hereafter occupy in the records of human character. He has laid the foundation of the happiness of thousands, and sincerely do we wish that he may yet live many years to witness the successful progress of the cause to which he has so gloriously contributed.

We recommend such of our readers as take interest in genuine records of glowing patriotism, to turn to general Miller’s “Memoirs”—for such volumes of exhaustless variety and importance are seldom met with in these days of flimsy literature.

[For the following graphic sketch, acknowledgment is due to the last No. (5) of the Foreign Quarterly Review, where it is stated to be copied from Pouqueville’s Travels in Greece. There is too much romance in it for out sober belief, and for the credit of Pouqueville—who by his statements has misled thousands—we ought to state that he gives it as the production of another pen. However, a marvellous story never loses by travelling; but—

Vires acquirit eundo.

Of course, it is easy enough for any enthusiast to put such words as the following into the mouth of a man who has been reviled and attacked by thousands; but we hope, for the credit of the reading world, that such stories as the following, seldom find implicit credence. There may, however, be some foundation for the following romaunt, and probably the incident, however slight, was too tempting to be sent forth to the world unadorned. If Lord Byron ever uttered such words as are here attributed to him—”I am still an Atheist“—it must have been in a fit of the most malignant obstinacy that ever distorted and disgraced the human mind—or perhaps in that spirit of malicious banter with which he was accustomed to torment his best and nearest friends. That such was his genuine sentiment, we can never bring ourselves to believe; and whatever standing is possessed by us in the world, should willingly be staked upon this point. As a romance of the pen, and not as a pure narrative of facts, we trust the following will be received; for, as such alone is it presented to our readers.]

Lord Byron during his stay at Athens, lodged at the Capuchin Convent. The Reverend Father Paul had found favour in the sight of this surprising genius;—his age, his profession, his gentleness, had gained him the affection of that nobleman in such a manner, that he devoted himself to him with all the caprice of his character. Wearied with everything, oppressed by his familiar demon, Byron came one day to find Father Paul, and request his hospitality.

The monk on seeing him reminded him of the words of the last conversation they had had together—”You cannot convince me, I am still an Atheist.” Instead of replying, Byron requested the Father to permit him to inhabit a cell, and relieve him from the ennui which poisoned his life. “While uttering these words,” said Father Paul, “he pressed my hands, and called me his father; the locks of his hair, dripping with perspiration, covered his forehead; his face was pale, his lips trembled: dared I to ask him the cause of his melancholy?”—“My father, all your days are like each other; as for me, I shall always be a traveller.”—“Have you no country? If the feeling of absence causes your sorrow, depart; my prayers and good wishes will accompany you to England.”—“Speak not to me of England; I would rather be dragged in chains on the sands of Libya, than revisit places imprinted with the curse which I have given them. The injustice of men has made England odious to me; it has separated us for ever; after the death of man, however, if it be true that the soul survives, I should be delighted to inhabit it, as a pure spirit. This mystery is only known to God.”—“Well, if you have renounced your country, take care to give your mind occupation, without too great exertion of your fancy. Is it the fault of the Creator if men are misled by false doctrines? God never predestined their perfect knowledge. Think you that peace of mind, and health of body can be the lot of him, whose life is perpetually in contradiction to that of other men? His reason is perverted who doubts the infinite power of God, and the man inscribed on the list of Atheists must be necessarily unhappy.”—“Atheist! Atheist! This is then the end of your consolation to me! It is thus that you call your son! Minister of that God who reads the hearts of men, learn, my reverend father, that it is beyond your power to discover an Atheist, even if his own mouth made you the hypocritical confession. [pg 240]An Atheist it is impossible to find—to admit his existence is to outrage the Sovereign of the World, who, in perfecting his noblest work, did not forget to engrave there the name of its immortal Author. Passions may arouse doubts; but when the Atheist questions himself, the evidence of a God confounds his incredulity, and the truth of the sentiment which fills his thoughts absolves him of the crime of Atheism. It is easy for you, my father, never to murmur against the Author of your being; you, who, in the gentle quiet of a life exempt from storms; have acquired the conviction that the sun of your old age will illumine the same scenes as did that of your youth. As for me—thrown on the earth like a disinherited child, born to feel happiness, and never finding it—I wander from climate to climate, with the sentiment of my everlasting misery. Since reason has unfolded to me the feeling of my wretchedness, nothing has yet tempered the bitterness of my distress. Fed with the hate of men—betrayed by those whose kindness I compared to that of angels—attacked by an incurable disease, which has swept away my ancestors—tell me, man of truth, if murmurs excited by despair can characterize an Atheist, and bring upon him the anger of Heaven. Oh! unhappy Byron!! if after so many mortal trials thy last hope of salvation is taken from thee—well!!”—Here the voice of my lord faltered.

His gloomy silence lasted nearly a quarter of an hour. All on a sudden he rose from his chair with eagerness, and walked round the room, stopping before the holy pictures which adorned it. A moment after he came to me, and said, “Do you remember that you promised a month ago to give me certain things which you possess?”—“I possess very little, and that little has nothing which can tempt you: however, speak!”—“I remember the words of your answer, and you can no longer refuse me anything.” Then he advanced towards a corner of my room, and taking down a beautiful crucifix which I had brought from Rome, he placed it in my hands. I offered it to Byron, saying, “This is the consoler of the unhappy.” He seized it with transport, and kissing it several times, he added, with eyes bathed in tears, “My hands shall not long profane it, and my mother will soon be the guardian of your precious relic!”

To griefs congenial prone,

More wounds than nature gave he knew,

While misery’s form his fancy drew

In dark ideal hues, and horrors not its own.

Goethe—Foreign Review.

A snapper up of unconsidered trifles.

SHAKSPEARE

Our journals, which tell us of ev’ry one’s matters,

From the king on the throne, to the pauper in tatters;

Say his lordship possesses, if rightly I scan ‘em,

Two hundred and seventy-two thousands per annum.

On this statement I’ve latterly ventur’d to ponder,

And deduc’d calculations, with diff’rence as under:

I suppos’d was his income five thousand a week,

(Of the surplus remaining I shall not now speak2)

By close computation I found it came near

To seven hundred and twenty, for each day’s arrear.

Intent on the subject reducing it lower

I found thirty pounds was the draught for each hour.

Pursuing my theme, for amusement was in it,

There were ten shillings sterling for each fleeting minute,

And for ev’ry pulsation of time, called a second,

“According to Cocker,” two-pence must be reckon’d.

PERCY HENDON.

In the churchyard of Carisbrook is the following epitaph on a loving couple:—

Of life he had the better slice,

They lived at once, and died at twice.

Frost is the greatest artist in our clime;

He paints in nature, and describes in rime.

Purchasers of the MIRROR, who may wish to complete their volumes, are informed that the whole of the numbers are now in print, and can be procured by giving an order to any Bookseller or Newsvender.

Complete sets Vol I. to XI. in boards, price £2. 19s. 6d. half bound, £3. 17s.

Footnote 1: (return)Dr. Fuller relates the following anecdote of this divine:—Dr. Reynolds, who held the living of Lavenham, having gone over to the Church of Rome, the Earl of Oxford, the patron, presented Mr. Copinger, but on condition that he should pay no tithes for his park, which comprehended almost half the land in the parish. Mr. Copinger told his lordship, that he would rather return the presentation, than by such a sinful gratitude betray the rights of the church. This answer so affected the earl, that he replied, “I scorn that my estate should swell with church goods.” His heir, however, contested the rector’s right to the tithes, and it cost Mr. Copinger £1,600. to recover that right, and leave the quiet possession of it to his successors.

Footnote 2: (return)There remains the sum of £12,000 which I have not treated on in order to avoid fractional parts.

Printed and Published by J. LIMBIRD, 143, Strand, (near Somerset House,) London; sold by ERNEST FLEISCHER, 626, New Market, Leipsic; and by all Newsmen and Booksellers.