Project Gutenberg's The Temptation of St. Antony, by Gustave Flaubert

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Temptation of St. Antony

or A Revelation of the Soul

Author: Gustave Flaubert

Release Date: April 12, 2008 [EBook #25053]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE TEMPTATION OF ST. ANTONY ***

Produced by Thierry Alberto, Henry Craig and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

SIMON P. MAGEE

PUBLISHER

CHICAGO, ILL.

Copyright, 1904, by

M. WALTER DUNNE

Entered at Stationers' Hall, London

| CHAPTER I. | PAGE |

| A HOLY SAINT | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| THE TEMPTATION OF LOVE AND POWER | 16 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| THE DISCIPLE, HILARION | 40 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| THE FIERY TRIAL | 48 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| ALL GODS, ALL RELIGIONS | 99 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| THE MYSTERY OF SPACE | 143 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| THE CHIMERA AND THE SPHINX | 151 |

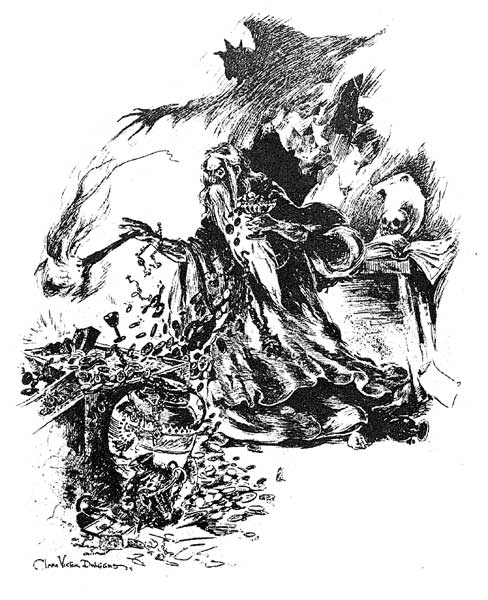

| "DO NOT RESIST, I AM OMNIPOTENT!" (See page 157) | Frontispiece |

| HE LETS GO THE TORCH IN ORDER TO EMBRACE THE HEAP | 26 |

T is in the Thebaïd, on the heights of a mountain, where a platform, shaped like a crescent, is surrounded by huge stones.

The Hermit's cell occupies the background. It is built of mud and reeds, flat-roofed and doorless. Inside are seen a pitcher and a loaf of black bread; in the centre, on a wooden support, a large book; on the ground, here and there, bits of rush-work, a mat or two, a basket and a knife.

Some ten paces or so from the cell a tall cross is planted in the ground; and, at the other end of the platform, a gnarled old palm-tree leans over the abyss, for the side of the mountain is scarped; and at the bottom of the cliff the Nile swells, as it were, into a lake.[Pg 2]

To right and left, the view is bounded by the enclosing rocks; but, on the side of the desert, immense undulations of a yellowish ash-colour rise, one above and one beyond the other, like the lines of a sea-coast; while, far off, beyond the sands, the mountains of the Libyan range form a wall of chalk-like whiteness faintly shaded with violet haze. In front, the sun is going down. Towards the north, the sky has a pearl-grey tint; while, at the zenith, purple clouds, like the tufts of a gigantic mane, stretch over the blue vault. These purple streaks grow browner; the patches of blue assume the paleness of mother-of-pearl. The bushes, the pebbles, the earth, now wear the hard colour of bronze, and through space floats a golden dust so fine that it is scarcely distinguishable from the vibrations of light.

Saint Antony, who has a long beard, unshorn locks, and a tunic of goatskin, is seated, cross-legged, engaged in making mats. No sooner has the sun disappeared than he heaves a deep sigh, and gazing towards the horizon:

"Another day! Another day gone! I was not so miserable in former times as I am now! Before the night was over, I used to begin my prayers; then I would go down to the river to fetch water, and would reascend the rough mountain pathway, singing a hymn, with the water-bottle on my shoulder. After that, I used to amuse myself by arranging everything in my cell. I used to take up my tools, and examine the mats, to see whether they were evenly cut, and the baskets, to see whether they were light; for it seemed to me then that even my most trifling acts were duties which I performed with ease. At regulated hours I left off my work and[Pg 3] prayed, with my two arms extended. I felt as if a fountain of mercy were flowing from Heaven above into my heart. But now it is dried up. Why is this? ..."

He proceeds slowly into the rocky enclosure.

"When I left home, everyone found fault with me. My mother sank into a dying state; my sister, from a distance, made signs to me to come back; and the other one wept, Ammonaria, that child whom I used to meet every evening, beside the cistern, as she was leading away her cattle. She ran after me. The rings on her feet glittered in the dust, and her tunic, open at the hips, fluttered in the wind. The old ascetic who hurried me from the spot addressed her, as we fled, in loud and menacing tones. Then our two camels kept galloping continuously, till at length every familiar object had vanished from my sight.

"At first, I selected for my abode the tomb of one of the Pharaohs. But some enchantment surrounds those subterranean palaces, amid whose gloom the air is stifled with the decayed odour of aromatics. From the depths of the sarcophagi I heard a mournful voice arise, that called me by name—or rather, as it seemed to me, all the fearful pictures on the walls started into hideous life. Then I fled to the borders of the Red Sea into a citadel in ruins. There I had for companions the scorpions that crawled amongst the stones, and, overhead, the eagles who were continually whirling across the azure sky. At night, I was torn by talons, bitten by beaks, or brushed with light wings; and horrible demons, yelling in my ears, hurled me to the earth. At last, the drivers of a caravan, which was journeying towards Alexandria, rescued me, and carried me along with them.[Pg 4]

"After this, I became a pupil of the venerable Didymus. Though he was blind, no one equalled him in knowledge of the Scriptures. When our lesson was ended, he used to take my arm, and, with my aid, ascend the Panium, from whose summit could be seen the Pharos and the open sea. Then we would return home, passing along the quays, where we brushed against men of every nation, including the Cimmerians, clad in bearskin, and the Gymnosophists of the Ganges, who smear their bodies with cow-dung. There were continual conflicts in the streets, some of which were caused by the Jews' refusal to pay taxes, and others by the attempts of the seditious to drive out the Romans. Besides, the city is filled with heretics, the followers of Manes, of Valentinus, of Basilides, and of Arius, all of them eagerly striving to discuss with you points of doctrine and to convert you to their views.

"Their discourses sometimes come back to my memory; and, though I try not to dwell upon them, they haunt my thoughts.

"I next took refuge in Colzin, and, when I had undergone a severe penance, I no longer feared the wrath of God. Many persons gathered around me, offering to become anchorites. I imposed on them a rule of life in antagonism to the vagaries of Gnosticism and the sophistries of the philosophers. Communications now reached me from every quarter, and people came a great distance to see me.

"Meanwhile, the populace continued to torture the confessors; and I was led back to Alexandria by an ardent thirst for martyrdom. I found on my arrival that the persecution had ceased three days before. Just as I was returning, my path was blocked by a great crowd in front of the Temple of Serapis. I was[Pg 5] told that the Governor was about to make one final example. In the centre of the portico, in the broad light of day, a naked woman was fastened to a pillar, while two soldiers were scourging her. At each stroke her entire frame writhed. Suddenly, she cast a wild look around, her trembling lips parted; and, above the heads of the multitude, her figure wrapped, as it were, in her flowing hair, methought I recognised Ammonaria. ... Yet this one was taller—and beautiful, exceedingly!"

He draws his hand across his brow.

"No! no! I must not think upon it!

"On another occasion, Athanasius asked me to assist him against the Arians. At that time, they had confined themselves to attacking him with invectives and ridicule. Since then, however, he has been calumniated, deprived of his see, and banished. Where is he now? I know not! People concern themselves so little about bringing me any news! All my disciples have abandoned me, Hilarion like the rest.

"He was, perhaps, fifteen years of age when he came to me, and his mind was so much filled with curiosity that every moment he was asking me questions. Then he would listen with a pensive air; and, without a murmur, he would run to fetch whatever I wanted—more nimble than a kid, and gay enough, moreover, to make even a patriarch laugh. He was a son to me!"

The sky is red; the earth completely dark. Agitated by the wind, clouds of sand rise, like winding-sheets, and then fall again. All at once, in a clear space in the heavens, a flock of birds flits by, forming a kind of triangular battalion, resembling a piece of metal with its edges alone vibrating.[Pg 6]

Antony glances at them.

"Ah! how I should like to follow them! How often, too, have I not wistfully gazed at the long boats with their sails resembling wings, especially when they bore away those who had been my guests! What happy times I used to have with them! What outpourings! None of them interested me more than Ammon. He described to me his journey to Rome, the Catacombs, the Coliseum, the piety of illustrious women, and a thousand other things. And yet I was unwilling to go away with him! How came I to be so obstinate in clinging to this solitary life? It might have been better for me had I stayed with the monks of Nitria when they besought me to do so. They occupy separate cells, and yet communicate with one another. On Sunday the trumpet calls them to the church, where you may see three whips hung up, which are reserved for the punishment of thieves and intruders, for they maintain very severe discipline.

"Nevertheless, they do not stand in need of gifts, for the faithful bring them eggs, fruit, and even instruments for removing thorns from their feet. There are vineyards around Pisperi, and those of Pabenum have a raft, in which they go forth to seek provisions.

"But I should have served my brethren more effectually by being a simple priest. I might succour the poor, administer the sacraments, and guard the purity of domestic life. Besides, all the laity are not lost, and there was nothing to prevent me from being, for example, a grammarian or a philosopher. I should have had in my room a sphere made of reeds, tablets always in my hand, young people around me, and a crown of laurel suspended as an emblem over my door.[Pg 7]

"But there is too much pride in such triumphs! Better be a soldier. I was strong and courageous enough to manage engines of war, to traverse gloomy forests, or, with helmet on head, to enter smoking cities. More than this, there would be nothing to hinder me from purchasing with my earnings the office of toll-keeper of some bridge, and travellers would relate to me their histories, pointing out to me heaps of curious objects which they had stowed away in their baggage.

"On festival days the merchants of Alexandria sail along the Canopic branch of the Nile and drink wine from cups of lotus, to the sound of tambourines, which make all the taverns near the river shake. Beyond, trees, cut cone-fashion, protect the peaceful farmsteads against the south wind. The roof of each house rests on slender columns running close to one another, like the framework of a lattice, and, through these spaces, the owner, stretched on a long seat, can gaze out upon his grounds and watch his servants thrashing corn or gathering in the vintage, and the cattle trampling on the straw. His children play along the grass; his wife bends forward to kiss him."

Through the deepening shadows of the night pointed snouts reveal themselves here and there with ears erect and glittering eyes. Antony advances towards them. Scattering the wind in their wild rush, the animals take flight. It was a troop of jackals.

One of them remains behind, and, resting on two paws, with his body bent and his head on one side, he places himself in an attitude of defiance.

"How pretty he looks! I should like to pass my hand softly over his back."[Pg 8]

Antony whistles to make him come near. The jackal disappears.

"Ah! he is gone to join his fellows. Oh! this solitude! this weariness!"

Laughing bitterly:

"This is such a delightful life—to twist palm branches in the fire to make shepherds' crooks, to turn out baskets and fasten mats together, and then to exchange all this handiwork with the Nomads for bread that breaks your teeth! Ah! wretched me! will there never be an end of this? But, indeed, death would be better! I can bear it no longer! Enough! Enough!"

He stamps his foot, and makes his way through the rocks with rapid step, then stops, out of breath, bursts into sobs, and flings himself upon the ground.

The night is calm; millions of stars are trembling in the sky. No sound is heard save the chattering of the tarantula.

The two arms of the cross cast a shadow on the sand. Antony, who is weeping, perceives it.

"Am I so weak, my God? Courage! Let us arise!"

He enters his cell, finds there the embers of a fire, lights a torch, and places it on the wooden stand, so as to illumine the big book.

"Suppose I take—the 'Acts of the Apostles'—yes, no matter where!

"'He saw the sky opened with a great linen sheet which was let down by its four corners, wherein were all kinds of terrestrial animals and wild beasts, reptiles and birds. And a voice said to him: Arise, Peter! Kill and eat!'

"So, then, the Lord wished that His apostle should eat every kind of food? ... whilst I ..."[Pg 9]

Antony lets his chin sink on his breast. The rustling of the pages, which the wind scatters, causes him to lift his head, and he reads:

"'The Jews slew all their enemies with swords, and made a great carnage of them, so that they disposed at will of those whom they hated.'

"There follows the enumeration of the people slain by them—seventy-five thousand. They had endured so much! Besides, their enemies were the enemies of the true God. And how they must have enjoyed their vengeance, completely slaughtering the idolaters! No doubt the city was gorged with the dead! They must have been at the garden gates, on the staircases, and packed so closely together in the various rooms that the doors could not be closed! But here am I plunging into thoughts of murder and bloodshed!"

He opens the book at another passage.

"'Nebuchadnezzar prostrated himself with his face on the ground and adored Daniel.'

"Ah! that is good! The Most High exalts His prophets above kings. This monarch spent his life in feasting, always intoxicated with sensuality and pride. But God, to punish him, changed him into a beast, and he walked on four paws!"

Antony begins to laugh; and, while stretching out his arms, disarranges the leaves of the book with the tips of his fingers. Then his eyes fall on these words:

"'Ezechias felt great joy in coming to them. He showed them his perfumes, his gold and silver, all his aromatics, his sweet-smelling oils, all his precious vases, and the things that were in his treasures.'

"I can imagine how they beheld, heaped up to the very ceiling, gems, diamonds, darics. A man[Pg 10] who possesses such an accumulation of these things is not the same as others. While handling them, he assumes that he holds the result of innumerable exertions, and that he has absorbed, and can again diffuse, the very life of the people. This is a useful precaution for kings. The wisest of them all was not wanting in it. His fleets brought him ivory—and apes. Where is this? It is——"

He rapidly turns over the leaves.

"Ah! this is the place:

"'The Queen of Sheba, being aware of the glory of Solomon, came to tempt him, propounding enigmas.'

"How did she hope to tempt him? The Devil was very desirous to tempt Jesus. But Jesus triumphed because He was God, and Solomon owing, perhaps, to his magical science. It is sublime, this science; for—as a philosopher has explained to me—the world forms a whole, all whose parts have an influence on one another, like the different organs of a single body. It is interesting to understand the affinities and antipathies implanted in everything by Nature, and then to put them into play. In this way one might be able to modify laws that appear to be unchangeable."

At this point the two shadows traced behind him by the arms of the cross project themselves in front of him. They form, as it were, two great horns. Antony exclaims:

"Help, my God!"

The shadows resume their former position.

"Ah! it was an illusion—nothing more. It is useless for me to torment my soul, I have no need to do so—absolutely no need!"

He sits down and crosses his arms.[Pg 11]

"And yet methought I felt the approach ... But why should he come? Besides, do I not know his artifices? I have repelled the monstrous anchorite who, with a laugh, offered me little hot loaves; the centaur who tried to take me on his back; and that vision of a beautiful dusky maid amid the sands, which revealed itself to me as the spirit of voluptuousness."

Antony walks up and down rapidly.

"It is by my direction that all these holy retreats have been built, full of monks wearing hair-cloths beneath their goatskins, and numerous enough to furnish forth an army. I have healed diseases at a distance. I have banished demons. I have waded through the river in the midst of crocodiles. The Emperor Constantine has written me three letters; and Balacius, who treated with contempt the letter I sent him, has been torn by his own horses. The people of Alexandria, whenever I reappeared amongst them, fought to get a glimpse of me; and Athanasius was my guide when I took my departure. But what toils, too, I have had to undergo! Here, for more than thirty years, have I been constantly groaning in the desert! I have carried on my loins eighty pounds of bronze, like Eusebius; I have exposed my body to the stings of insects, like Macarius; I have remained fifty-three nights without closing an eye, like Pachomius; and those who are decapitated, torn with pincers, or burnt, possess less virtue, perhaps, inasmuch as my life is a continual martyrdom!"

Antony slackens his pace.

"Certainly there is no one who undergoes so much mortification. Charitable hearts are growing fewer, and people never give me anything now. My[Pg 12] cloak is worn out, and I have no sandals, nor even a porringer; for I gave all my goods and chattels to the poor and my own family, without keeping a single obolus for myself. Should I not need a little money to get the tools that are indispensable for my work? Oh! not much—a little sum! ... I would husband it.

"The Fathers of Nicæa were ranged in purple robes on thrones along the wall, like the Magi; and they were entertained at a banquet, while honours were heaped upon them, especially on Paphnutius, merely because he has lost an eye and is lame since Dioclesian's persecution! Many a time the Emperor has kissed his injured eye. What folly! Moreover, the Council had such worthless members! Theophilus, a bishop of Scythia; John, another, in Persia; Spiridion, a cattle-drover. Alexander was too old. Athanasius ought to have made himself more agreeable to the Arians in order to get concessions from them!

"How is it they dealt with me? They would not even give me a hearing! He who spoke against me—a tall young man with a curling beard—coolly launched out captious objections; and while I was trying to find words to reply to him, they kept looking at me with malignant glances, barking at me like hyenas. Ah! if I could only get them all sent into exile by the Emperor, or rather smite them, crush them, behold them suffering. I have much to suffer myself!"

He sinks swooning against the wall of his cell.

"This is what it is to have fasted overmuch! My strength is going. If I had eaten, only once, a morsel of meat!"

He half-closes his eyes languidly.[Pg 13]

"Ah! for some red flesh ... a bunch of grapes to nibble, some curds that would quiver on a plate!

"But what ails me now? What ails me now? I feel my heart dilating like the sea when it swells before the storm. An overwhelming weakness bows me down, and the warm atmosphere seems to waft towards me the odour of hair. Still, there is no trace of a woman here."

He turns towards the little pathway amid the rocks.

"This is the way they come, poised in their litters on the black arms of eunuchs. They descend, and, joining together their hands, laden with rings, they kneel down. They tell me their troubles. The need of a superhuman voluptuousness tortures them. They would like to die; in their dreams they have seen gods who called them by name; and the edges of their robes fall round my feet. I repel them. 'Oh! no,' they say to me, 'not yet! What must I do?' Any penance will appear easy to them. They ask me for the most severe: to share in my own, to live with me.

"It is a long time now since I have seen any of them! Perhaps, though, this is what is about to happen? And why not? If suddenly I were to hear the mule-bells ringing in the mountains. It seems to me ..."

Antony climbs upon a rock, at the entrance of the path, and bends forward, darting his eyes into the darkness.

"Yes! down there, at the very end, there is a moving mass, like people who are trying to pick their way. Here it is! They are making a mistake."[Pg 14]

Calling out:

"On this side! Come! Come!"

The echo repeats:

"Come! Come!"

He lets his arms fall down, quite dazed.

"What a shame! Ah! poor Antony!"

And immediately he hears a whisper:

"Poor Antony."

"Is that anyone? Answer!"

It is the wind passing through the spaces between the rocks that causes these intonations, and in their confused sonorities he distinguishes voices, as if the air were speaking. They are low and insinuating, a kind of sibilant utterance:

The first—"Do you wish for women?"

The second—"Nay; rather great piles of money."

The third—"A shining sword."

The others—"All the people admire you."

"Go to sleep."

"You will cut their throats. Yes! you will cut their throats."

At the same time, visible objects undergo a transformation. On the edge of the cliff, the old palm-tree, with its cluster of yellow leaves, becomes the torso of a woman leaning over the abyss, and poised by her mass of hair.

Antony re-enters his cell, and the stool which sustains the big book, with its pages filled with black letters, seems to him a bush covered with swallows.

"Without doubt, it is the torch that is making this play of light. Let us put it out!"

He puts it out, and finds himself in profound darkness.[Pg 15]

And, suddenly, through the midst of the air, passes first, a pool of water, then a prostitute, the corner of a temple, a figure of a soldier, and a chariot with two white horses prancing.

These images make their appearance abruptly, in successive shocks, standing out from the darkness like pictures of scarlet above a background of ebony.

Their motion becomes more rapid; they pass in a dizzy fashion. At other times they stop, and, growing pale by degrees, dissolve—or, rather, they fly away, and instantly others arrive in their stead.

Antony droops his eyelids.

They multiply, surround, besiege him. An unspeakable terror seizes hold of him, and he no longer has any sensation but that of a burning contraction in the epigastrium. In spite of the confusion of his brain, he is conscious of a tremendous silence which separates him from all the world. He tries to speak; impossible! It is as if the link that bound him to existence was snapped; and, making no further resistance, Antony falls upon the mat.[Pg 16]

HEN, a great shadow—more subtle than an ordinary shadow, from whose borders other shadows hang in festoons—traces itself upon the ground.

It is the Devil, resting against the roof of the cell and carrying under his wings—like a gigantic bat that is suckling its young—the Seven Deadly Sins, whose grinning heads disclose themselves confusedly.

Antony, his eyes still closed, remains languidly passive, and stretches his limbs upon the mat, which seems to him to grow softer every moment, until it swells out and becomes a bed; then the bed becomes a shallop, with water rippling against its sides.

To right and left rise up two necks of black soil that tower above the cultivated plains, with a sycamore here and there. A noise of bells, drums, and singers resounds at a distance. These are caused by people who are going down from Canopus to sleep at the Temple of Serapis. Antony is aware of this, and he glides, driven by the wind, between the two banks of the canal. The leaves of the papyrus and the red blossoms of the water-lilies, larger than a[Pg 17] man, bend over him. He lies extended at the bottom of the vessel. An oar from behind drags through the water. From time to time rises a hot breath of air that shakes the thin reeds. The murmur of the tiny waves grows fainter. A drowsiness takes possession of him. He dreams that he is an Egyptian Solitary.

Then he starts up all of a sudden.

"Have I been dreaming? It was so pleasant that I doubted its reality. My tongue is burning! I am thirsty!"

He enters his cell and searches about everywhere at random.

"The ground is wet! Has it been raining? Stop! Scraps of food! My pitcher broken! But the water-bottle?"

He finds it.

"Empty, completely empty! In order to get down to the river, I should need three hours at least, and the night is so dark I could not see well enough to find my way there. My entrails are writhing. Where is the bread?"

After searching for some time he picks up a crust smaller than an egg.

"How is this? The jackals must have taken it, curse them!"

And he flings the bread furiously upon the ground.

This movement is scarcely completed when a table presents itself to view, covered with all kinds of dainties. The table-cloth of byssus, striated like the fillets of sphinxes, seems to unfold itself in luminous undulations. Upon it there are enormous quarters of flesh-meat, huge fishes, birds with their feathers, quadrupeds with their hair, fruits with an almost natural colouring; and pieces of white ice and flagons[Pg 18] of violet crystal shed glowing reflections. In the middle of the table Antony observes a wild boar smoking from all its pores, its paws beneath its belly, its eyes half-closed—and the idea of being able to eat this formidable animal rejoices his heart exceedingly. Then, there are things he had never seen before—black hashes, jellies of the colour of gold, ragoûts, in which mushrooms float like water-lilies on the surface of a pool, whipped creams, so light that they resemble clouds.

And the aroma of all this brings to him the odour of the ocean, the coolness of fountains, the mighty perfume of woods. He dilates his nostrils as much as possible; he drivels, saying to himself that there is enough there to last for a year, for ten years, for his whole life!

In proportion as he fixes his wide-opened eyes upon the dishes, others accumulate, forming a pyramid, whose angles turn downwards. The wines begin to flow, the fishes to palpitate; the blood in the dishes bubbles up; the pulp of the fruits draws nearer, like amorous lips; and the table rises to his breast, to his very chin—with only one seat and one cover, which are exactly in front of him.

He is about to seize the loaf of bread. Other loaves make their appearance.

"For me! ... all! but——"

Antony draws back.

"In the place of the one which was there, here are others! It is a miracle, then, exactly like that the Lord performed! ... With what object? Nay, all the rest of it is not less incomprehensible! Ah! demon, begone! begone!"

He gives a kick to the table. It disappears.[Pg 19]

"Nothing more? No!"

He draws a long breath.

"Ah! the temptation was strong. But what an escape I have had!"

He raises up his head, and stumbles against an object which emits a sound.

"What can this be?"

Antony stoops down.

"Hold! A cup! Someone must have lost it while travelling—nothing extraordinary!—--"

He wets his finger and rubs.

"It glitters! Precious metal! However, I cannot distinguish——"

He lights his torch and examines the cup.

"It is made of silver, adorned with ovolos at its rim, with a medal at the bottom."

He makes the medal resound with a touch of his finger-nail.

"It is a piece of money which is worth from seven to eight drachmas—not more. No matter! I can easily with that sum get myself a sheepskin."

The torch's reflection lights up the cup.

"It is not possible! Gold! yes, all gold!"

He finds another piece, larger than the first, at the bottom, and, underneath that many others.

"Why, here's a sum large enough to buy three cows—a little field!"

The cup is now filled with gold pieces.

"Come, then! a hundred slaves, soldiers, a heap wherewith to buy——"

Here the granulations of the cup's rim, detaching themselves, form a pearl necklace.

"With this jewel here, one might even win the Emperor's wife!"[Pg 20]

With a shake Antony makes the necklace slip over his wrist. He holds the cup in his left hand, and with his right arm raises the torch to shed more light upon it. Like water trickling down from a basin, it pours itself out in continuous waves, so as to make a hillock on the sand—diamonds, carbuncles, and sapphires mingled with huge pieces of gold bearing the effigies of kings.

"What? What? Staters, shekels, darics, aryandics! Alexander, Demetrius, the Ptolemies, Cæsar! But each of them had not as much! Nothing impossible in it! More to come! And those rays which dazzle me! Ah! my heart overflows! How good this is! Yes! ... Yes! ... more! Never enough! It did not matter even if I kept flinging it into the sea; more would remain. Why lose any of it? I will keep it all, without telling anyone about it. I will dig myself a chamber in the rock, the interior of which will be lined with strips of bronze; and thither will I come to feel the piles of gold sinking under my heels. I will plunge my arms into it as if into sacks of corn. I would like to anoint my face with it—to sleep on top of it!"

He lets go the torch in order to embrace the heap, and falls to the ground on his breast. He gets up again. The place is perfectly empty!

"What have I done? If I died during that brief space of time, the result would have been Hell—irrevocable Hell!"

A shudder runs through his frame.

"So, then, I am accursed? Ah! no, this is all my own fault! I let myself be caught in every trap. There is no one more idiotic or more infamous. I would like to beat myself, or, rather, to tear myself[Pg 21] out of my body. I have restrained myself too long. I need to avenge myself, to strike, to kill! It is as if I had a troop of wild beasts in my soul. I would like, with a stroke of a hatchet in the midst of a crowd——Ah! a dagger! ..."

He flings himself upon his knife, which he has just seen. The knife slips from his hand, and Antony remains propped against the wall of his cell, his mouth wide open, motionless—like one in a trance.

All the surroundings have disappeared.

He finds himself in Alexandria on the Panium—an artificial mound raised in the centre of the city, with corkscrew stairs on the outside.

In front of it stretches Lake Mareotis, with the sea to the right and the open plain to the left, and, directly under his eyes, an irregular succession of flat roofs, traversed from north to south and from east to west by two streets, which cross each other, and which form, in their entire length, a row of porticoes with Corinthian capitals. The houses overhanging this double colonnade have stained-glass windows. Some have enormous wooden cages outside of them, in which the air from without is swallowed up.

Monuments in various styles of architecture are piled close to one another. Egyptian pylons rise above Greek temples. Obelisks exhibit themselves like spears between battlements of red brick. In the centres of squares there are statues of Hermes with pointed ears, and of Anubis with dogs' heads. Antony notices the mosaics in the court-yards, and the tapestries hung from the cross-beams of the ceiling.

With a single glance he takes in the two ports (the Grand Port and the Eunostus), both round like two circles, and separated by a mole joining Alexan[Pg 22]dria to the rocky island, on which stands the tower of the Pharos, quadrangular, five hundred cubits high and in nine storys, with a heap of black charcoal flaming on its summit.

Small ports nearer to the shore intersect the principal ports. The mole is terminated at each end by a bridge built on marble columns fixed in the sea. Vessels pass beneath, and pleasure-boats inlaid with ivory, gondolas covered with awnings, triremes and biremes, all kinds of shipping, move up and down or remain at anchor along the quays.

Around the Grand Port there is an uninterrupted succession of Royal structures: the palace of the Ptolemies, the Museum, the Posideion, the Cæsarium, the Timonium where Mark Antony took refuge, and the Soma which contains the tomb of Alexander; while at the other extremity of the city, close to the Eunostus, might be seen glass, perfume, and paper factories.

Itinerant vendors, porters, and ass-drivers rush to and fro, jostling against one another. Here and there a priest of Osiris with a panther's skin on his shoulders, a Roman soldier, or a group of negroes, may be observed. Women stop in front of stalls where artisans are at work, and the grinding of chariot-wheels frightens away some birds who are picking up from the ground the sweepings of the shambles and the remnants of fish. Over the uniformity of white houses the plan of the streets casts, as it were, a black network. The markets, filled with herbage, exhibit green bouquets, the drying-sheds of the dyers, plates of colours, and the gold ornaments on the pediments of temples, luminous points—all this contained within the oval enclosure of the greyish walls, under the vault of the blue heavens, hard by the motionless sea.[Pg 23] But the crowd stops and looks towards the eastern side, from which enormous whirlwinds of dust are advancing.

It is the monks of the Thebaïd who are coming, clad in goats' skins, armed with clubs, and howling forth a canticle of war and of religion with this refrain:

"Where are they? Where are they?"

Antony comprehends that they have come to kill the Arians.

All at once, the streets are deserted, and one sees no longer anything but running feet.

And now the Solitaries are in the city. Their formidable cudgels, studded with nails, whirl around like monstrances of steel. One can hear the crash of things being broken in the houses. Intervals of silence follow, and then the loud cries burst forth again. From one end of the streets to the other there is a continuous eddying of people in a state of terror. Several are armed with pikes. Sometimes two groups meet and form into one; and this multitude, after rushing along the pavements, separates, and those composing it proceed to knock one another down. But the men with long hair always reappear.

Thin wreaths of smoke escape from the corners of buildings. The leaves of the doors burst asunder; the skirts of the walls fall in; the architraves topple over.

Antony meets all his enemies one after another. He recognises people whom he had forgotten. Before killing them, he outrages them. He rips them open, cuts their throats, knocks them down, drags the old men by their beards, runs over children, and beats those who are wounded. People revenge themselves on luxury. Those who cannot read, tear the books[Pg 24] to pieces; others smash and destroy the statues, the paintings, the furniture, the cabinets—a thousand dainty objects whose use they are ignorant of, and which, for that very reason, exasperate them. From time to time they stop, out of breath, and then begin again. The inhabitants, taking refuge in the court-yards, utter lamentations. The women lift their eyes to Heaven, weeping, with their arms bare. In order to move the Solitaries they embrace their knees; but the latter only dash them aside, and the blood gushes up to the ceiling, falls back on the linen clothes that line the walls, streams from the trunks of decapitated corpses, fills the aqueducts, and rolls in great red pools along the ground.

Antony is steeped in it up to his middle. He steps into it, sucks it up with his lips, and quivers with joy at feeling it on his limbs and under his hair, which is quite wet with it.

The night falls. The terrible clamour abates.

The Solitaries have disappeared.

Suddenly, on the outer galleries lining the nine stages of the Pharos, Antony perceives thick black lines, as if a flock of crows had alighted there. He hastens thither, and soon finds himself on the summit.

A huge copper mirror turned towards the sea reflects the ships in the offing.

Antony amuses himself by looking at them; and as he continues looking at them, their number increases.

They are gathered in a gulf formed like a crescent. Behind, upon a promontory, stretches a new city built in the Roman style of architecture, with cupolas of stone, conical roofs, marble work in red and blue, and a profusion of bronze attached to the volutes of capi[Pg 25]tals, to the tops of houses, and to the angles of cornices. A wood, formed of cypress-trees, overhangs it. The colour of the sea is greener; the air is colder. On the mountains at the horizon there is snow.

Antony is about to pursue his way when a man accosts him, and says:

"Come! they are waiting for you!"

He traverses a forum, enters a court-yard, stoops under a gate, and he arrives before the front of the palace, adorned with a group in wax representing the Emperor Constantine hurling the dragon to the earth. A porphyry basin supports in its centre a golden conch filled with pistachio-nuts. His guide informs him that he may take some of them. He does so.

Then he loses himself, as it were, in a succession of apartments.

Along the walls may be seen, in mosaic, generals offering conquered cities to the Emperor on the palms of their hands. And on every side are columns of basalt, gratings of silver filigree, seats of ivory, and tapestries embroidered with pearls. The light falls from the vaulted roof, and Antony proceeds on his way. Tepid exhalations spread around; occasionally he hears the modest patter of a sandal. Posted in the ante-chambers, the custodians—who resemble automatons—bear on their shoulders vermilion-coloured truncheons.

At last, he finds himself in the lower part of a hall with hyacinth curtains at its extreme end. They divide, and reveal the Emperor seated upon a throne, attired in a violet tunic and red buskins with black bands.

A diadem of pearls is wreathed around his hair, which is arranged in symmetrical rolls. He has drooping eyelids, a straight nose, and a heavy and cunning expression of countenance. At the corners of the daïs, extended above his head, are placed four golden doves, and, at the foot of the throne, two enamelled lions are squatted. The doves begin to coo, the lions to roar. The Emperor rolls his eyes; Antony steps forward; and directly, without preamble, they proceed with a narrative of events.

"In the cities of Antioch, Ephesus, and Alexandria, the temples have been pillaged, and the statues of the gods converted into pots and porridge-pans."

The Emperor laughs heartily at this. Antony reproaches him for his tolerance towards the Novatians. But the Emperor flies into a passion. "Novatians, Arians, Meletians—he is sick of them all!" However, he admires the episcopacy, for the Christians create bishops, who depend on five or six personages, and it is his interest to gain over the latter in order to have the rest on his side. Moreover, he has not failed to furnish them with considerable sums. But he detests the fathers of the Council of Nicæa. "Come, let us have a look at them."

Antony follows him. And they are found on the same floor under a terrace which commands a view of a hippodrome full of people, and surmounted by porticoes wherein the rest of the crowd are walking to and fro. In the centre of the course there is a narrow platform on which stands a miniature temple of Mercury, a statue of Constantine, and three bronze serpents intertwined with each other; while at one end there are three huge wooden eggs, and at the other seven dolphins with their tails in the air.

Behind the Imperial pavilion, the prefects of the chambers, the lords of the household, and the Patri[Pg 27]cians are placed at intervals as far as the first story of a church, all whose windows are lined with women. At the right is the gallery of the Blue faction, at the left that of the Green, while below there is a picket of soldiers, and, on a level with the arena, a row of Corinthian pillars, forming the entrance to the stalls.

The races are about to begin; the horses fall into line. Tall plumes fixed between their ears sway in the wind like trees; and in their leaps they shake the chariots in the form of shells, driven by coachmen wearing a kind of many-coloured cuirass with sleeves narrow at the wrists and wide in the arms, with legs uncovered, full beard, and hair shaven above the forehead after the fashion of the Huns.

Antony is deafened by the murmuring of voices. Above and below he perceives nothing but painted faces, motley garments, and plates of worked gold; and the sand of the arena, perfectly white, shines like a mirror.

The Emperor converses with him, confides to him some important secrets, informs him of the assassination of his own son Crispus, and goes so far as to consult Antony about his health.

Meanwhile, Antony perceives slaves at the end of the stalls. They are the fathers of the Council of Nicæa, in rags, abject. The martyr Paphnutius is brushing a horse's mane; Theophilus is scrubbing the legs of another; John is painting the hoofs of a third; while Alexander is picking up their droppings in a basket.

Antony passes among them. They salaam to him, beg of him to intercede for them, and kiss his hands. The entire crowd hoots at them; and he rejoices in[Pg 28] their degradation immeasurably. And now he has become one of the great ones of the Court, the Emperor's confidant, first minister! Constantine places the diadem on his forehead, and Antony keeps it, as if this honour were quite natural to him.

And presently is disclosed, beneath the darkness, an immense hall, lighted up by candelabra of gold.

Columns, half lost in shadow so tall are they, run in a row behind the tables, which stretch to the horizon, where appear, in a luminous haze, staircases placed one above another, successions of archways, colossi, towers; and, in the background, an unoccupied wing of the palace, which cedars overtop, making blacker masses above the darkness.

The guests, crowned with violets, lean upon their elbows on low-lying couches. Beside each one are placed amphorae, from which they pour out wine; and, at the very end, by himself, adorned with the tiara and covered with carbuncles, King Nebuchadnezzar is eating and drinking. To right and left of him, two theories of priests, with peaked caps, are swinging censers. Upon the ground are crawling captive kings, without feet or hands, to whom he flings bones to pick. Further down stand his brothers, with shades over their eyes, for they are perfectly blind.

A constant lamentation ascends from the depths of the ergastula. The soft and monotonous sounds of a hydraulic organ alternate with the chorus of voices; and one feels as if all around the hall there was an immense city, an ocean of humanity, whose waves were beating against the walls.

The slaves rush forward carrying plates. Women run about offering drink to the guests. The baskets[Pg 29] groan under the load of bread, and a dromedary, laden with leathern bottles, passes to and fro, letting vervain trickle over the floor in order to cool it.

Belluarii lead forth lions; dancing-girls, with their hair in ringlets, turn somersaults, while squirting fire through their nostrils; negro-jugglers perform tricks; naked children fling snowballs, which, in falling, crash against the shining silver plate. The clamour is so dreadful that it might be described as a tempest, and the steam of the viands, as well as the respirations of the guests, spreads, as it were, a cloud over the feast. Now and then, flakes from the huge torches, snatched away by the wind, traverse the night like flying stars.

The King wipes off the perfumes from his visage with his hand. He eats from the sacred vessels, and then breaks them, and he enumerates, mentally, his fleets, his armies, his peoples. Presently, through a whim, he will burn his palace, along with his guests. He calculates on rebuilding the Tower of Babel, and dethroning God.

Antony reads, at a distance, on his forehead, all his thoughts. They take possession of himself—and he becomes Nebuchadnezzar.

Immediately, he is satiated with conquests and exterminations; and a longing seizes him to plunge into every kind of vileness. Moreover, the degradation wherewith men are terrified is an outrage done to their souls, a means still more of stupefying them; and, as nothing is lower than a brute beast, Antony falls upon four paws on the table, and bellows like a bull.

He feels a pain in his hand—a pebble, as it happened, has hurt him—and he again finds himself in his cell.[Pg 30]

The rocky enclosure is empty. The stars are shining. All is silence.

"Once more I have been deceived. Why these things? They arise from the revolts of the flesh! Ah! miserable man that I am!"

He dashes into his cell, takes out of it a bundle of cords, with iron nails at the ends of them, strips himself to the waist, and raising his eyes towards Heaven:

"Accept my penance, O my God! Do not despise it on account of its insufficiency. Make it sharp, prolonged, excessive. It is time! To work!"

He proceeds to lash himself vigorously.

"Ah! no! no! No pity!"

He begins again.

"Oh! Oh! Oh! Each stroke tears my skin, cuts my limbs. This smarts horribly! Ah! it is not so terrible! One gets used to it. It seems to me even ..."

Antony stops.

"Come on, then, coward! Come on, then! Good! good! On the arms, on the back, on the breast, against the belly, everywhere! Hiss, thongs! bite me! tear me! I would like the drops of my blood to gush forth to the stars, to break my back, to strip my nerves bare! Pincers! wooden horses! molten lead! The martyrs bore more than that! Is that not so, Ammonaria?"

The shadows of the Devil's horns reappear.

"I might have been fastened to the pillar next to yours, face to face with you, under your very eyes, responding to your shrieks with my sighs, and our griefs would blend into one, and our souls would commingle."[Pg 31]

He flogs himself furiously.

"Hold! hold! for your sake! once more! ... But this is a mere tickling that passes through my frame. What torture! What delight! Those are like kisses. My marrow is melting! I am dying!"

And in front of him he sees three cavaliers, mounted on wild asses, clad in green garments, holding lilies in their hands, and all resembling one another in figure.

Antony turns back, and sees three other cavaliers of the same kind, mounted on similar wild asses, in the same attitude.

He draws back. Then the wild asses, all at the same time, step forward a pace or two, and rub their snouts against him, trying to bite his garment. Voices exclaim, "This way! this way! Here is the place!" And banners appear between the clefts of the mountain, with camels' heads in halters of red silk, mules laden with baggage, and women covered with yellow veils, mounted astride on piebald horses.

The panting animals lie down; the slaves fling themselves on the bales of goods, roll out the variegated carpets, and strew the ground with glittering objects.

A white elephant, caparisoned with a fillet of gold, runs along, shaking the bouquet of ostrich feathers attached to his head-band.

On his back, lying on cushions of blue wool, cross-legged, with eyelids half-closed and well-poised head, is a woman so magnificently attired that she emits rays around her. The attendants prostrate themselves, the elephant bends his knees, and the Queen of Sheba, gliding down by his shoulder, steps lightly on the carpet and advances towards Antony.[Pg 32] Her robe of gold brocade, regularly divided by furbelows of pearls, jet and sapphires, is drawn tightly round her waist by a close-fitting corsage, set off with a variety of colours representing the twelve signs of the Zodiac. She wears high-heeled pattens, one of which is black and strewn with silver stars and a crescent, whilst the other is white and is covered with drops of gold, with a sun in their midst.

Her loose sleeves, garnished with emeralds and birds' plumes, exposes to view her little, rounded arms, adorned at the wrists with bracelets of ebony; and her hands, covered with rings, are terminated by nails so pointed that the ends of her fingers are almost like needles.

A chain of plate gold, passing under her chin, runs along her cheeks till it twists itself in spiral fashion around her head, over which blue powder is scattered; then, descending, it slips over her shoulders and is fastened above her bosom by a diamond scorpion, which stretches out its tongue between her breasts. From her ears hang two great white pearls. The edges of her eyelids are painted black. On her left cheek-bone she has a natural brown spot, and when she opens her mouth she breathes with difficulty, as if her bodice distressed her.

As she comes forward, she swings a green parasol with an ivory handle surrounded by vermilion bells; and twelve curly negro boys carry the long train of her robe, the end of which is held by an ape, who raises it every now and then.

She says:

"Ah! handsome hermit! handsome hermit! My heart is faint! By dint of stamping with impatience my heels have grown hard, and I have split one of[Pg 33] my toe-nails. I sent out shepherds, who posted themselves on the mountains, with their bands stretched over their eyes, and searchers, who cried out your name in the woods, and scouts, who ran along the different roads, saying to each passer-by: 'Have you seen him?'

"At night I shed tears with my face turned to the wall. My tears, in the long run, made two little holes in the mosaic-work—like pools of water in rocks—for I love you! Oh! yes; very much!"

She catches his beard.

"Smile on me, then, handsome hermit! Smile on me, then! You will find I am very gay! I play on the lyre, I dance like a bee, and I can tell many stories, each one more diverting than the last.

"You cannot imagine what a long journey we have made. Look at the wild asses of the green-clad couriers—dead through fatigue!"

The wild asses are stretched motionless on the ground.

"For three great moons they have journeyed at an even pace, with pebbles in their teeth to cut the wind, their tails always erect, their hams always bent, and always in full gallop. You will not find their equals. They came to me from my maternal grandfather, the Emperor Saharil, son of Jakhschab, son of Jaarab, son of Kastan. Ah! if they were still living, we would put them under a litter in order to get home quickly. But ... how now? ... What are you thinking of?"

She inspects him.

"Ah! when you are my husband, I will clothe you, I will fling perfumes over you, I will pick out your hairs."[Pg 34]

Antony remains motionless, stiffer than a stake, pale as a corpse.

"You have a melancholy air: is it at quitting your cell? Why, I have given up everything for your sake—even King Solomon, who has, no doubt, much wisdom, twenty thousand war-chariots, and a lovely beard! I have brought you my wedding presents. Choose."

She walks up and down between the row of slaves and the merchandise.

"Here is balsam of Genesareth, incense from Cape Gardefan, ladanum, cinnamon and silphium, a good thing to put into sauces. There are within Assyrian embroideries, ivories from the Ganges, and the purple cloth of Elissa; and this case of snow contains a bottle of Chalybon, a wine reserved for the Kings of Assyria, which is drunk pure out of the horn of a unicorn. Here are collars, clasps, fillets, parasols, gold dust from Baasa, tin from Tartessus, blue wood from Pandion, white furs from Issidonia, carbuncles from the island of Palæsimundum, and tooth-picks made with the hair of the tachas—an extinct animal found under the earth. These cushions are from Emathia, and these mantle-fringes from Palmyra. Under this Babylonian carpet there are ... but come, then! Come, then!"

She pulls Saint Antony along by the beard. He resists. She goes on:

"This light tissue, which crackles under the fingers with the noise of sparks, is the famous yellow linen brought by the merchants from Bactriana. They required no less than forty-three interpreters during their voyage. I will make garments of it for you, which you will put on at home.[Pg 35]

"Press the fastenings of that sycamore box, and give me the ivory casket in my elephant's packing-case!"

They draw out of a box some round objects covered with a veil, and bring her a little case covered with carvings.

"Would you like the buckler of Dgian-ben-Dgian, the builder of the Pyramids? Here it is! It is composed of seven dragons' skins placed one above another, joined by diamond screws, and tanned in the bile of a parricide. It represents, on one side, all the wars which have taken place since the invention of arms, and, on the other, all the wars that will take place till the end of the world. Above, the thunderbolt rebounds like a ball of cork. I am going to put it on your arm, and you will carry it to the chase.

"But if you knew what I have in my little case! Try to open it! Nobody has succeeded in doing that. Embrace me, and I will tell you."

She takes Saint Antony by the two cheeks. He repels her with outstretched arms.

"It was one night when King Solomon had lost his head. At length, we had concluded a bargain. He arose, and, going out with the stride of a wolf ..."

She dances a pirouette.

"Ah! ah! handsome hermit! you shall not know it! you shall not know it!"

She shakes her parasol, and all the little bells begin to ring.

"I have many other things besides—there, now! I have treasures shut up in galleries, where they are lost as in a wood. I have summer palaces of lattice-[Pg 36]reeds, and winter palaces of black marble. In the midst of great lakes, like seas, I have islands round as pieces of silver all covered with mother-of-pearl, whose shores make music with the beating of the liquid waves that roll over the sand. The slaves of my kitchen catch birds in my aviaries, and angle for fish in my ponds. I have engravers continually sitting to stamp my likeness on hard stones, panting workers in bronze who cast my statues, and perfumers who mix the juice of plants with vinegar and beat up pastes. I have dressmakers who cut out stuffs for me, goldsmiths who make jewels for me, women whose duty it is to select head-dresses for me, and attentive house-painters pouring over my panellings boiling resin, which they cool with fans. I have attendants for my harem, eunuchs enough to make an army. And then I have armies, subjects! I have in my vestibule a guard of dwarfs, carrying on their backs ivory trumpets."

Antony sighs.

"I have teams of gazelles, quadrigæ of elephants, hundreds of camels, and mares with such long manes that their feet get entangled with them when they are galloping, and flocks with such huge horns that the woods are torn down in front of them when they are pasturing. I have giraffes who walk in my gardens, and who raise their heads over the edge of my roof when I am taking the air after dinner. Seated in a shell, and drawn by dolphins, I go up and down the grottoes, listening to the water flowing from the stalactites. I journey to the diamond country, where my friends the magicians allow me to choose the most beautiful; then I ascend to earth once more, and return home."[Pg 37]

She gives a piercing whistle, and a large bird, descending from the sky, alights on the top of her head-dress, from which he scatters the blue powder. His plumage, of orange colour, seems composed of metallic scales. His dainty head, adorned with a silver tuft, exhibits a human visage. He has four wings, a vulture's claws, and an immense peacock's tail, which he displays in a ring behind him. He seizes in his beak the Queen's parasol, staggers a little before he finds his equilibrium, then erects all his feathers, and remains motionless.

"Thanks, fair Simorg-anka! You who have brought me to the place where the lover is concealed! Thanks! thanks! messenger of my heart! He flies like desire. He travels all over the world. In the evening he returns; he lies down at the foot of my couch; he tells me what he has seen, the seas he has flown over, with their fishes and their ships, the great empty deserts which he has looked down upon from his airy height in the skies, all the harvests bending in the fields, and the plants that shoot up on the walls of abandoned cities."

She twists her arms with a languishing air.

"Oh! if you were willing! if you were only willing! ... I have a pavilion on a promontory, in the midst of an isthmus between two oceans. It is wainscotted with plates of glass, floored with tortoise-shells, and is open to the four winds of Heaven. From above, I watch the return of my fleets and the people who ascend the hill with loads on their shoulders. We should sleep on down softer than clouds; we should drink cool draughts out of the rinds of fruit, and we gaze at the sun through a canopy of emeralds. Come!"[Pg 38]

Antony recoils. She draws close to him, and, in a tone of irritation:

"How so? Rich, coquettish, and in love?—is not that enough for you, eh? But must she be lascivious, gross, with a hoarse voice, a head of hair like fire, and rebounding flesh? Do you prefer a body cold as a serpent's skin, or, perchance, great black eyes more sombre than mysterious caverns? Look at these eyes of mine, then!"

Antony gazes at them, in spite of himself.

"All the women you ever have met, from the daughter of the cross-roads singing beneath her lantern to the fair patrician scattering leaves from the top of her litter, all the forms you have caught a glimpse of, all the imaginings of your desire, ask for them! I am not a woman—I am a world. My garments have but to fall, and you shall discover upon my person a succession of mysteries."

Antony's teeth chattered.

"If you placed your finger on my shoulder, it would be like a stream of fire in your veins. The possession of the least part of my body will fill you with a joy more vehement than the conquest of an empire. Bring your lips near! My kisses have the taste of fruit which would melt in your heart. Ah! how you will lose yourself in my tresses, caress my breasts, marvel at my limbs, and be scorched by my eyes, between my arms, in a whirlwind——"

Antony makes the sign of the Cross.

"So, then, you disdain me! Farewell!"

She turns away weeping; then she returns.

"Are you quite sure? So lovely a woman?"

She laughs, and the ape who holds the end of her robe lifts it up.[Pg 39]

"You will repent, my fine hermit! you will groan; you will be sick of life! but I will mock at you! la! la! la! oh! oh! oh!"

She goes off with her hands on her waist, skipping on one foot.

The slaves file off before Saint Antony's face, together with the horses, the dromedaries, the elephant, the attendants, the mules, once more covered with their loads, the negro boys, the ape, and the green-clad couriers holding their broken lilies in their hands—and the Queen of Sheba departs, with a spasmodic utterance which might be either a sob or a chuckle.

HEN she has disappeared, Antony perceives a child on the threshold of his cell.

"It is one of the Queen's servants," he thinks.

This child is small, like a dwarf, and yet thickset, like one of the Cabiri, distorted, and with a miserable aspect. White hair covers his prodigiously large head, and he shivers under a sorry tunic, while he grasps in his hand a roll of papyrus. The light of the moon, across which a cloud is passing, falls upon him.

Antony observes him from a distance, and is afraid of him.

"Who are you?"

The child replies:

"Your former disciple, Hilarion."

Antony—"You lie! Hilarion has been living for many years in Palestine."

Hilarion—"I have returned from it! It is I, in good sooth!"

Antony, draws closer and inspects him—"Why, his figure was bright as the dawn, open, joyous. This one is quite sombre, and has an aged look."[Pg 41]

Hilarion—"I am worn out with constant toiling."

Antony—"The voice, too, is different. It has a tone that chills you."

Hilarion—"That is because I nourish myself on bitter fare."

Antony—"And those white locks?"

Hilarion—"I have had so many griefs."

Antony, aside—"Can it be possible? ..."

Hilarion—"I was not so far away as you imagined. The hermit, Paul, paid you a visit this year during the month of Schebar. It is just twenty days since the nomads brought you bread. You told a sailor the day before yesterday to send you three bodkins."

Antony—"He knows everything!"

Hilarion—"Learn, too, that I have never left you. But you spend long intervals without perceiving me."

Antony—"How is that? No doubt my head is troubled! To-night especially ..."

Hilarion—"All the deadly sins have arrived. But their miserable snares are of no avail against a saint like you!"

Antony—"Oh! no! no! Every minute I give way! Would that I were one of those whose souls are always intrepid and their minds firm—like the great Athanasius, for example!"

Hilarion—"He was unlawfully ordained by seven bishops!"

Antony—"What does it matter? If his virtue ..."

Hilarion—"Come, now! A haughty, cruel man, always mixed up in intrigues, and finally exiled for being a monopolist."

Antony—"Calumny!"[Pg 42]

Hilarion—"You will not deny that he tried to corrupt Eustatius, the treasurer of the bounties?"

Antony—"So it is stated, and I admit it."

Hilarion—"He burned, for revenge, the house of Arsenius."

Antony—"Alas!"

Hilarion—"At the Council of Nicæa, he said, speaking of Jesus, 'The man of the Lord.'"

Antony—"Ah! that is a blasphemy!"

Hilarion—"So limited is he, too, that he acknowledges he knows nothing as to the nature of the Word."

Antony, smiling with pleasure—"In fact, he has not a very lofty intellect."

Hilarion—"If they had put you in his place, it would have been a great satisfaction for your brethren, as well as yourself. This life, apart from others, is a bad thing."

Antony—"On the contrary! Man, being a spirit, should withdraw himself from perishable things. All action degrades him. I would like not to cling to the earth—even with the soles of my feet."

Hilarion—"Hypocrite! who plunges himself into solitude to free himself the better from the outbreaks of his lusts! You deprive yourself of meat, of wine, of stoves, of slaves, and of honours; but how you let your imagination offer you banquets, perfumes, naked women, and applauding crowds! Your chastity is but a more subtle kind of corruption, and your contempt for the world is but the impotence of your hatred against it! This is the reason that persons like you are so lugubrious, or perhaps it is because they lack faith. The possession of the truth gives joy. Was Jesus sad? He used to go about surrounded by[Pg 43] friends; He rested under the shade of the olive, entered the house of the publican, multiplied the cups, pardoned the fallen woman, healing all sorrows. As for you, you have no pity, save for your own wretchedness. You are so much swayed by a kind of remorse, and by a ferocious insanity, that you would repel the caress of a dog or the smile of a child."

Antony, bursts out sobbing—"Enough! Enough! You move my heart too much."

Hilarion—"Shake off the vermin from your rags! Get rid of your filth! Your God is not a Moloch who requires flesh as a sacrifice!"

Antony—"Still, suffering is blessed. The cherubim bend down to receive the blood of confessors."

Hilarion—"Then admire the Montanists! They surpass all the rest."

Antony—"But it is the truth of the doctrine that makes the martyr."

Hilarion—"How can he prove its excellence, seeing that he testifies equally on behalf of error?"

Antony—"Be silent, viper!"

Hilarion—"It is not perhaps so difficult. The exhortations of friends, the pleasure of outraging popular feeling, the oath they take, a certain giddy excitement—a thousand things, in fact, go to help them."

Antony draws away from Hilarion. Hilarion follows him—"Besides, this style of dying introduces great disorders. Dionysius, Cyprian, and Gregory avoided it. Peter of Alexandria has disapproved of it; and the Council of Elvira ..."

Antony, stops his ears—"I will listen to no more!"

Hilarion, raising his voice—"Here you are again falling into your habitual sin—laziness. Ignorance is[Pg 44] the froth of pride. You say, 'My conviction is formed; why discuss the matter?' and you despise the doctors, the philosophers, tradition, and even the text of the law, of which you know nothing. Do you think you hold wisdom in your hand?"

Antony—"I am always hearing him! His noisy words fill my head."

Hilarion—"The endeavours to comprehend God are better than your mortifications for the purpose of moving him. We have no merit save our thirst for truth. Religion alone does not explain everything; and the solution of the problems which you have ignored might render it more unassailable and more sublime. Therefore, it is essential for each man's salvation that he should hold intercourse with his brethren—otherwise the Church, the assembly of the faithful, would be only a word—and that he should listen to every argument, and not disdain anything, or anyone. Balaam the soothsayer, Æschylus the poet, and the sybil of Cumæ, announced the Saviour. Dionysius the Alexandrian received from Heaven a command to read every book. Saint Clement enjoins us to study Greek literature. Hermas was converted by the illusion of a woman that he loved!"

Antony—"What an air of authority! It appears to me that you are growing taller ..."

In fact, Hilarion's height has progressively increased; and, in order not to see him, Antony closes his eyes.

Hilarion—"Make your mind easy, good hermit. Let us sit down here, on this big stone, as of yore, when, at the break of day, I used to salute you, addressing you as 'Bright morning star'; and you at once began to give me instruction. It is not fin[Pg 45]ished yet. The moon affords us sufficient light. I am all attention."

He has drawn forth a calamus from his girdle, and, cross-legged on the ground, with his roll of papyrus in his hand, he raises his head towards Antony, who, seated beside him, keeps his forehead bent.

"Is not the word of God confirmed for us by the miracles? And yet the sorcerers of Pharaoh worked miracles. Other impostors could do the same; so here we may be deceived. What, then, is a miracle? An occurrence which seems to us outside the limits of Nature. But do we know all Nature's powers? And, from the mere fact that a thing ordinarily does not astonish us, does it follow that we comprehend it?"

Antony—"It matters little; we must believe in the Scripture."

Hilarion—"Saint Paul, Origen, and some others did not interpret it literally; but, if we explain it allegorically, it becomes the heritage of a limited number of people, and the evidence of its truth vanishes. What are we to do, then?"

Antony—"Leave it to the Church."

Hilarion—"Then the Scripture is useless?"

Antony—"Not at all. Although the Old Testament, I admit, has—well, obscurities ... But the New shines forth with a pure light."

Hilarion—"And yet the Angel of the Annunciation, in Matthew, appears to Joseph, whilst in Luke it is to Mary. The anointing of Jesus by a woman comes to pass, according to the First Gospel, at the beginning of his public life, but according to the three others, a few days before his death. The drink which they offer him on the Cross is, in Matthew, vinegar[Pg 46] and gall, in Mark, wine and myrrh. If we follow Luke and Matthew, the Apostles ought to take neither money nor bag—in fact, not even sandals or a staff; while in Mark, on the contrary, Jesus forbids them to carry with them anything except sandals and a staff. Here is where I get lost ..."

Antony, in amazement—"In fact ... in fact ..."

Hilarion—"At the contact of the woman with the issue of blood, Jesus turned round, and said, 'Who has touched me?' So, then, He did not know who touched Him? That is opposed to the omniscience of Jesus. If the tomb was watched by guards, the women had not to worry themselves about an assistant to lift up the stone from the tomb. Therefore, there were no guards there—or rather, the holy women were not there at all. At Emmaüs, He eats with His disciples, and makes them feel His wounds. It is a human body, a material object, which can be weighed, and which, nevertheless, passes through stone walls. Is this possible?"

Antony—"It would take a good deal of time to answer you."

Hilarion—"Why did He receive the Holy Ghost, although He was the Son? What need had He of baptism, if He were the Word? How could the Devil tempt Him—God?

"Have these thoughts never occurred to you?"

Antony—"Yes! often! Torpid or frantic, they dwell in my conscience. I crush them out; they spring up again, they stifle me; and sometimes I believe that I am accursed."

Hilarion—"Then you have nothing to do but to serve God?"[Pg 47]

Antony—"I have always need to adore Him."

After a prolonged silence, Hilarion resumes:

"But apart from dogma, entire liberty of research is permitted us. Do you wish to become acquainted with the hierarchy of Angels, the virtue of Numbers, the explanation of germs and metamorphoses?"

Antony—"Yes! yes! My mind is struggling to escape from its prison. It seems to me that, by gathering my forces, I shall be able to effect this. Sometimes—even for an interval brief as a lightning-flash—I feel myself, as it were, suspended in mid-air; then I fall back again!"

Hilarion—"The secret which you are anxious to possess is guarded by sages. They live in a distant country, sitting under gigantic trees, robed in white, and calm as gods. A warm atmosphere nourishes them. All around leopards stride through the plains. The murmuring of fountains mingles with the neighing of unicorns. You shall hear them; and the face of the Unknown shall be unveiled!"

Antony, sighing—"The road is long and I am old!"

Hilarion—"Oh! oh! men of learning are not rare! There are some of them even very close to you here! Let us enter!"[Pg 48]

ND Antony sees in front of him an immense basilica. The light projects itself from the lower end with the magical effect of a many-coloured sun. It lights up the innumerable heads of the multitude which fills the nave and surges between the columns towards the side-aisles, where one can distinguish in the wooden compartments altars, beds, chainlets of little blue stones, and constellations painted on the walls.

In the midst of the crowd groups are stationed here and there; men standing on stools are discoursing with lifted fingers; others are praying with arms crossed, or lying down on the ground, or singing hymns, or drinking wine. Around a table the faithful are carrying on the love-feasts; martyrs are unswathing their limbs to show their wounds; old men, leaning on their staffs, are relating their travels.

Amongst them are people from the country of the Germans, from Thrace, Gaul, Scythia and the Indies—with snow on their beards, feathers in their hair, thorns in the fringes of their garments, sandals cov[Pg 49]ered with dust, and skins burnt by the sun. All costumes are mingled—mantles of purple and robes of linen, embroidered dalmatics, woollen jackets, sailors' caps and bishops' mitres. Their eyes gleam strangely. They have the appearance of executioners or of eunuchs.

Hilarion advances among them. Antony, pressing against his shoulder, observes them. He notices a great many women. Several of them are dressed like men, with their hair cut short. He is afraid of them.

Hilarion—"These are the Christian women who have converted their husbands. Besides, the women are always for Jesus—even the idolaters—as witness Procula, the wife of Pilate, and Poppæa, the concubine of Nero. Don't tremble any more! Come on!"

There are fresh arrivals every moment.

They multiply; they separate, swift as shadows, all the time making a great uproar, or intermingling yells of rage, exclamations of love, canticles, and upbraidings.

Antony, in a low tone—"What do they want?"

Hilarion—"The Lord said, 'I may still have to speak to you about many things.' They possess those things."

And he pushes him towards a throne of gold, five paces off, where, surrounded by ninety-five disciples, all anointed with oil, pale and emaciated, sits the prophet Manes—beautiful as an archangel, motionless as a statue—wearing an Indian robe, with carbuncles in his plaited hair, a book of coloured pictures in his left hand, and a globe under his right. The pictures represent the creatures who are slumbering in chaos. Antony bends forward to see him. Then[Pg 50] Manes makes his globe revolve, and, attuning his words to the music of a lyre, from which bursts forth crystalline sounds, he says:

"The celestial earth is at the upper extremity, the mortal earth at the lower. It is supported by two angels, the Splenditenens and the Omophorus, with six faces.

"At the summit of Heaven, the Impassible Divinity occupies the highest seat; underneath, face to face, are the Son of God and the Prince of Darkness.

"The darkness having made its way into His kingdom, God extracted from His essence a virtue which produced the first man; and He surrounded him with five elements. But the demons of darkness deprived him of one part, and that part is the soul.

"There is but one soul, spread through the universe, like the water of a stream divided into many channels. This it is that sighs in the wind, grinds in the marble which is sawn, howls in the voice of the sea; and it sheds milky tears when the leaves are torn off the fig-tree.

"The souls that leave this world emigrate towards the stars, which are animated beings."

Antony begins to laugh:

"Ah! ah! what an absurd hallucination!"

A man, beardless, and of austere aspect—"Why?"

Antony is about to reply. But Hilarion tells him in an undertone, that this man is the mighty Origen; and Manes resumes:

"At first, they stay in the moon, where they are purified. After that, they ascend to the sun."

Antony, slowly—"I know nothing to prevent us from believing it."[Pg 51]

Manes—"The end of every creature is the liberation of the celestial ray shut up in matter. It makes its escape more easily through perfumes, spices, the aroma of old wine, the light substances that resemble thought. But the actions of daily life withhold it. The murderer will be born again in the body of a eunuch; he who slays an animal will become that animal. If you plant a vine-tree, you will be fastened in its branches. Food absorbs those who use it. Therefore, mortify yourselves! fast!"

Hilarion—"They are temperate, as you see!"

Manes—"There is a great deal of it in flesh-meats, less in herbs. Besides, the Pure, by the force of their merits, despoil vegetables of that luminous spark, and it flies towards its source. The animals, by generation, imprison it in the flesh. Therefore, avoid women!"

Hilarion—"Admire their countenance!"

Manes—"Or, rather, act so well that they may not be prolific. It is better for the soul to sink on the earth than to languish in carnal fetters."

Antony—"Ah! abomination!"

Hilarion—"What matters the hierarchy of iniquities? The Church has done well to make marriage a sacrament!"

Saturninus, in Syrian costume—"He propagates a dismal order of things! The Father, in order to punish the rebel angels, commanded them to create the world. Christ came in order that the God of the Jews, who was one of those angels——"

Antony—"An angel? He! the Creator?"

Gerdon—"Did He not desire to kill Moses and deceive the prophets? and did He not lead the people astray, spreading lying and idolatry?"[Pg 52]

Marcion—"Certainly, the Creator is not the true God!"

Saint Clement of Alexandria—"Matter is eternal!"

Bardesanes, as one of the Babylonian Magi—"It was formed by the seven planetary spirits."

The Hernians—"The angels have made the souls!"

The Priscillianists—"The world was made by the Devil."

Antony, falls backward—"Horror!"

Hilarion, holding him up—"You drive yourself to despair too quickly! You don't rightly comprehend their doctrine. Here is one who has received his from Theodas, the friend of Saint Paul. Hearken to him!"

And, at a signal from Hilarion, Valentinus, in a tunic of silver cloth, with a hissing voice and a pointed skull, cries:

"The world is the work of a delirious God!"

Antony, hangs down his head—"The work of a delirious God!"

After a long silence:

"How is that?"

Valentinus—"The most perfect of the Æons, the Abysm, reposed on the bosom of Profundity together with Thought. From their union sprang Intelligence, who had for his consort Truth.

"Intelligence and Truth engendered the Word and Life, which in their turn engendered Man and the Church; and this makes eight Æons."

He reckons on his fingers:

"The Word and Truth produced ten other Æons, that is to say, five couples. Man and the Church produced twelve others, amongst whom were the Paraclete and Faith, Hope and Charity, Perfection and Wisdom, Sophia.[Pg 53]

"The entire of those thirty Æons constitutes the Pleroma, or Universality of God. Thus, like the echoes of a voice that is dying away, like the exhalations of a perfume that is evaporating, like the fires of a sun that is setting, the Powers that have emanated from the Highest Powers are always growing feeble.