Project Gutenberg's South America and the War, by F. A. Kirkpatrick This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: South America and the War Author: F. A. Kirkpatrick Release Date: February 9, 2012 [EBook #38793] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SOUTH AMERICA AND THE WAR *** Produced by Adrian Mastronardi, JoAnn Greenwood and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

This little book contains the substance, revised and adapted for publication, of lectures given in the Lent Term, 1918, at King's College, London, under the Tooke Trust for providing lectures on economic subjects. The course of lectures was in the first instance an endeavour to perform a war-service by drawing attention to the activity of the Germans in Latin America, and particularly to the ingenuity and tenacity of their efforts to hold their economic ground during the war, with a view to extending it after the conclusion of peace. A second object was to examine more generally the bearings of the war on those countries, and the influence of the present crisis on their development and status in the world.

These two topics, though closely connected, are distinct. The first has an immediate and present importance, the second has a wider historic significance. The logical connexion between them may not seem obvious. Yet the first enquiry, concerning German war-efforts in Latin America, naturally and inevitably led to the second, concerning the larger issues involved. The former topic is treated in Chapters I, II and III, the latter in Chapters IV, V and VI. The term "South America" is used in the title of this book as a matter of customary convenience; but it is not meant to exclude the Antillean Republics or the Latin-American States stretching to the North-west of the Isthmus of Panamá.

Clearly, an essay of this kind, if it was to be of any use, had to be produced quickly. It was impossible to wait in hopes of achieving some kind of completeness. The immediate and urgent importance of the subject has been signally emphasised by the despatch of a special British Diplomatic Mission to the Latin-American Republics, and by the King's message addressed to British subjects in Latin America, in order to inculcate the spirit of collective effort.

In the course of this essay frequent mention is made of the struggle for emancipation, of the part which Englishmen took in that struggle and of the great services rendered to the cause of independence by the action of British statesmen, notably Canning. In a book which aims mainly at a review of present conditions, it is impossible to enlarge upon these topics, since their adequate treatment would involve some consideration of political action on the European Continent and in the United States. But since this passage of past history bears closely on the present topic, it may be here mentioned that a brief account of these matters is given in the Cambridge Modern History, vol. X, chap. IX.

The subject of German "peaceful penetration," which is incidentally illustrated but not expounded in these chapters, may be studied in M. Hauser's book entitled (in its English version) Germany's Economic Grip upon the World; also in The Bloodless War, translated from the Italian of Signor Ezio Gray. The character of that penetration, with its admirable as well as its odious features, is briefly and clearly set forth in a recent Report (Cd 9059) presented to the Board of Trade on enemy interests in British trade.

I desire to express my indebtedness to Le Brésil, a weekly review of Latin-American affairs published in Paris; to The Times newspaper, particularly the monthly Trade Supplement and the South American number (Part 183) of The Times History of the War; to the weekly South American Journal; and to the monthly British and Latin-American Trade Gazette. The quotation on pages 40-41 is taken from The Times; and various other passages, not always verbally reproduced, are derived from the same source.

It is impossible to thank by name all those who have placed at my disposal their knowledge of Latin-American countries. But I owe an especial debt of gratitude to the Master of Peterhouse for his aid and advice in the production of this book.

The original matter has been considerably rearranged for purposes of publication. But wherever convenience permitted, the lecture form has been retained in order to indicate that the book owes its inception to King's College, London.

August 15, 1918.

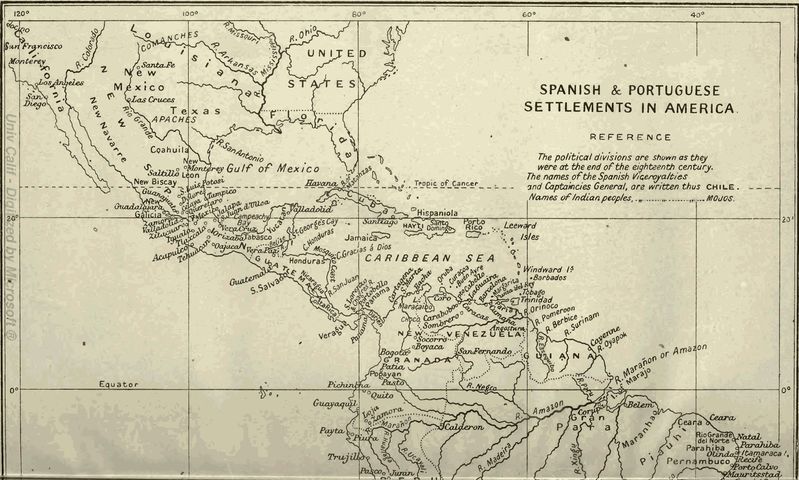

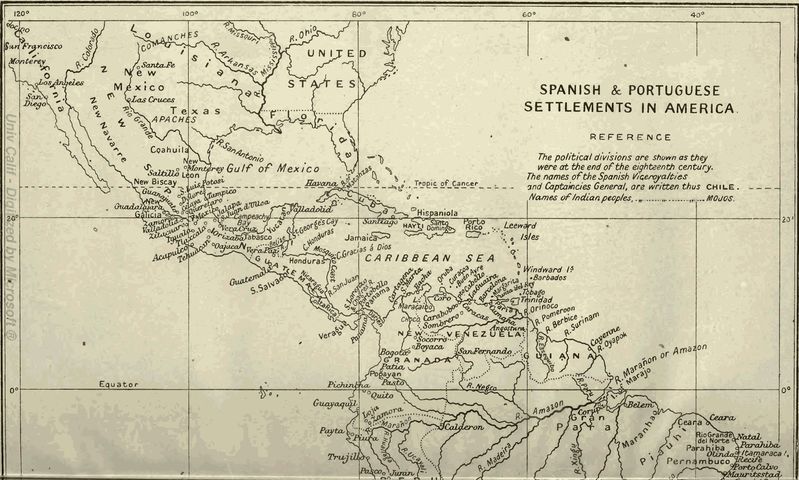

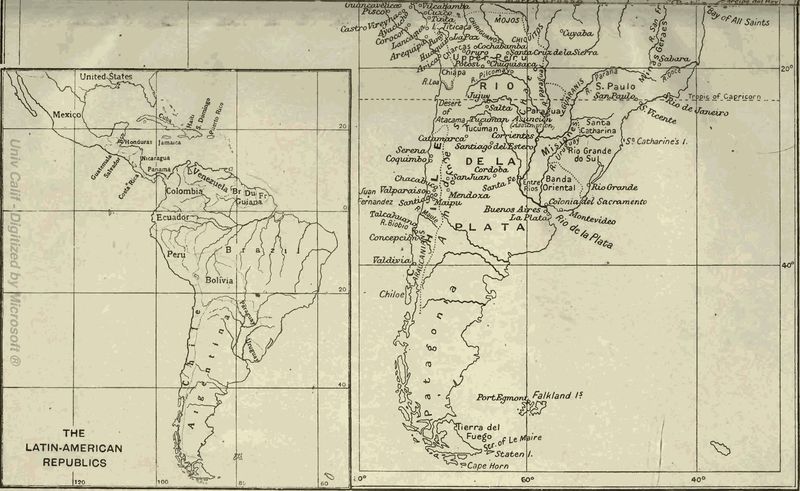

The map at the end of the book shows the former Spanish and Portuguese possessions in America, and also the existing Latin-American Republics.

The New World or Western Hemisphere consists of two continents. The greater part of the northern continent is occupied by two great Powers, which may be described as mainly Anglo-Saxon in origin and character. One of them, the Canadian Federation, is a monarchy, covering the northern part of the continent. The other, a republic, the United States, occupies the middle part. To the south and south-east of these two extensive and powerful countries stretch the twenty republics, mainly Iberian in origin and character, which constitute Latin America. These lands cover an area which is about twice the size of Europe or three times the size of the United States. Their population approaches eighty millions. Latin America, extending as it does through every habitable latitude from the north temperate zone to the Antarctic seas, possesses every climate and every variety of soil, and accordingly yields, or can be made to yield, all the vegetable and animal products of the whole world. Moreover, most of the republics also severally contain territory of every habitable altitude, so that a man can change his climate from torrid to temperate and from temperate to frigid simply by walking up-hill. Thus, equatorial lands can produce within the range of a few miles all the products of every zone. Most of the republics also furnish an abundance and variety of mineral products. The name Costa Rica, or Coast of Riches, which was given by the early discoverers to a small strip of the mainland, was prophetic of all its shores. And the fable of El Dorado, concerning its interior wealth, has proved to be not fabulous but only allegorical.

The geographical distribution of these republics should be indicated. Three of them are island states of the Caribbean Sea. Cuba is the largest of the Antilles; Santo Domingo and Haiti divide between them the next largest. The rich tropical fertility of these West Indian isles has been a proverb for centuries and need not here be emphasised. Upon the mainland, the vast territory of Mexico and the five Central-American republics may be grouped together, forming as they do a kind of sub-continent, a narrowed continuation of North America. Through this region a broad mountain-mass curves from north-west to south-east. This configuration provides the characteristics and the varied products of every zone upon the same parallel of latitude: the torrid coastal strips, bordering both oceans; the beautiful, wholesome and productive region of the central plateau and long upland valleys; and finally the chilly inhospitable regions of the mountain heights. The long sweep of the country south-eastwards through the tropics also provides a wide range of character, from the cattle-rearing plains of Northern Mexico to the coffee and banana plantations of Costa Rica. Nowhere are lands of richer possibilities to be found.

The small newly-created Republic of Panamá completes this northern system of Latin-American countries. Thus, before coming to South America at all, we count ten Latin-American states, three in the Antilles, seven upon the mainland.

The other ten republics lie within the continent of South America. That continent is shaped by nature in lines of a vast and imposing simplicity, so that it is possible to sketch its main features in a few words. It is divided broadly into mountain, forest and plain—the immense chain of the Andes, the vast Amazonian forests, the wide-stretching plains of the Pampa, and the colossal water system of the three rivers, Orinoco, Amazon, La Plata. The dominating element is the great backbone, the cordillera of the Andes. From the southern islands of Tierra del Fuego this cordillera stretches for 4000 miles along the Pacific coast to the northern peninsulas of the Spanish Main, and thence throws out a great eastward curve along the southern shore of the Caribbean Sea. This continuous mountain-wall, clinging closely to the Pacific coast, determines the whole character of the continent. In the tropical zone, the trade winds, blowing continually from the Atlantic, sweep across South America until they strike this towering mountain barrier. Then they shed their moisture on its eastern slopes, which give birth to the multitudinous upper waters of the Orinoco, the Amazon and the western affluents of the River Plate. The Amazon rather resembles a slowly moving inland sea, its twelve principal tributaries all surpassing the measure of European rivers. The River Plate pours into the ocean more water than all the rivers of Europe put together. The Orinoco, shorter but not less voluminous, drains a vast area with its 400 tributaries.

But the Andes, whose forest-clad eastern slopes pour these immeasurable water-floods across the whole continent to the Atlantic, oppose to the Pacific, in the southern tropics, a bare dry wall of rock and yellow sand. In the north, the garrua, the winter mist of equatorial Peru, supplies moisture for cultivation. South of this region, the rainless desert stretches, a ribbon-like strip, between the mountains and the sea. Here, except in some transverse river-valleys, not a blade of grass can grow for over a thousand miles. Yet it is this very barrenness which has produced the materials of fertility for other lands in the form of guano and nitrate deposits. Far to the south, in the "roaring forties," these conditions are reversed. Here, moisture-laden winds blow continually and stormily from the Pacific, feeding the dense and soaking forests of southern Chile. In the same latitudes, to the east of the Andes the terraced plains of Patagonia supply sheep pasture, thinly nourished by slight rainfall, although, over so vast an extent, these flocks amount to many millions. In the more temperate regions, between these zones of climatic extremes, more normal conditions prevail. On one side of the Andes are the rich valleys of Central Chile, on the other side the wide plains of the Argentine Pampa, formerly given over to pasture, now producing wheat, maize, flax, barley and oats as well as meat, hides and wool.

South America has been called the fertile continent. Considering that most of the land lies within the tropics, it might be called the habitable continent—habitable in comfort and health by white men. In form, the continent may be roughly compared with Africa, but the comparison is in favour of South America. The traveller who has sailed along the east or west coast of tropical Africa meets a contrast on crossing the Atlantic. Along the Brazilian coast, he finds a succession of busy ports, crowded with the shipping of all nations—flourishing and growing cities, inhabited largely by Europeans living the normal life of Europe. The perennial trade winds, blowing from the sea, bring coolness and health; and, almost everywhere, the worker in the ports may make his home upon neighbouring hills. On the west coast, tropical conditions are even more striking. Here, a soft south wind blows continually from cooler airs, and the Antarctic current flowing northwards refreshes all the coast. At Lima, twelve degrees from the Line, one may wear European dress at midsummer and, descending a few miles to the coast, may plunge into a sea which is almost too cold. Moreover, in these regions the Andine valleys offer every climate, and a short journey from the coast leads one to uplands resembling southern Europe. Higher yet, beyond the first or western chain of the Andes stretches the vast and lofty plateau enclosed between the double or triple ranges of volcanic mountains. The western part of Bolivia, though tropical in situation, is a temperate land, lying as it does at a height of above 12,000 feet. This broad Bolivian plateau narrows northwards through Peru and finally contracts into the Ecuadorian "avenue of volcanoes." Here, in the very central torrid zone, a double line of towering peaks shoot their fires far above plains and slopes of perpetual snow. Thence the cordillera opens out northwards into the broad triple range of Colombia, which encloses wide river valleys of extraordinary richness and fertile savannahs, enjoying perpetual spring.

Lastly, it should be noted that some of the best part of South America begins where Africa ends. Buenos Aires, Montevideo, Capetown and Sydney lie approximately in the same latitude, about 34° or 35° south. But some of the best parts of Chile and Argentina stretch far to the south of this latitude. Alone of the southern continents, South America thrusts itself far through the cool regions of the temperate zone.

Hitherto, white settlement in South America has, in the main, followed the easiest lines, along the coast, upon the southern plains and up the river courses. Of the three great rivers, the Orinoco is the least developed, partly owing to natural difficulties—namely, an uneven shifting bed and great differences of water level—partly owing to artificial and political conditions; but in the wet season its waters admit navigation up the main stream and its principal western affluent, the Apure, almost to the foothills of the Colombian Andes; and the trade winds, blowing upstream, carry sailing craft half across the continent. Upon the Amazon system, Manaos, one of the great ports of Brazil, is 900 miles from the sea: Iquitos, 2300 miles from salt water, is accessible to the smaller class of ocean steamers. Upon the Paraná, 1000 miles from the ocean, stands the port of Asunción, capital of Paraguay, accessible to ocean ships of shallow draught and to large river steamers: stern-wheel steamers can mount the Paraguay River 1000 miles farther to the remote Brazilian port of Cuyabá.

The navigation of both these river systems, the Amazon and the River Plate, is limited or rather interrupted by the fourth great feature of the continent, the Brazilian plateau. The Paraná and its affluents plunge from this plateau to the southern plain in tremendous waterfalls. The southern tributaries of the Amazon pierce their way down into the Amazonian valley along defiles, cataracts and rapids sometimes extending scores of miles. The Amazonian affluents are mostly navigable from the main river to the foot of these cascades. Above the cascades, there stretch fresh reaches of navigable water, providing many paths into the far interior. Similar conditions are found on the two branches of the River Tocantins and on other Brazilian rivers, such as the São Francisco and the Paranahyba. With the future growth of population, the construction of lateral railways and, later, perhaps the partial canalisation of rivers, there is no limit to the possibilities of internal water communication. The wealth of water power which awaits application is obvious. As to possibilities of water storage and irrigation, it suffices to say that on the Lower Orinoco and also on the Lower Amazon the difference of water level between wet and dry seasons is at least fifty feet, and most of the affluents rise and fall proportionately.

The great Brazilian plateau, which has just been mentioned, further justifies the description of South America as the fertile continent—the region of habitable tropics. The vast scale of this plateau and its relation to the River Plate system justify its description here as a continental feature rather than a purely national feature, although it is mainly a national possession of Brazil. From the north-east shoulder of the Brazilian coast, this varied plateau, seamed by many clefts, stretches southwards and south-westward in a vast semi-circular sweep dividing the two river-systems. The Paraná and its affluents plunge from this plateau towards the south and west. Northwards and eastwards it sends a multitude of streams to the Amazon and the Atlantic. These Brazilian uplands naturally vary in character and productiveness, but they are in great part suitable for white habitation and especially for the grazing of cattle. There is no winter; there is little of excessive or torrid heat; the grass grows all the year round; and in the neighbourhood of some rivers, the grasslands are annually renovated by seasonable and shallow floods.

Among the republics, the United States of Brazil stand in a class apart, by virtue of the Portuguese origin and character of that country, its very distinct history and its immense size, occupying, as it does, more than half the continent. As to the republics of Spanish origin, no single classification suffices. The most obvious division is that which groups them into tropical and temperate countries. The five republics of Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia, which lie wholly within the tropics, form a group of states which were closely connected in the early history of emancipation and which are still marked by a general though not very close similarity in respect of geography and ethnological conditions. Chile and Argentina lie mainly in the temperate zone; Uruguay wholly so; and these, with the southern parts of Brazil, are the regions most obviously suitable for white settlement. These three southern republics may also be described as the most European part of the continent, whereas the five tropical republics have a large admixture of indigenous, and, in parts, also of negro, blood.

The small sub-tropical republic of Paraguay, secluded in the interior of the continent, does not quite fall into either group, but belongs to the system of River Plate countries. For the three Atlantic republics of the southern hemisphere, Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, form a distinct group or sub-continent known as the "River Plate" and thus suggest a second classification into the Rio-Platense and the Andine states. Lastly, a glance at the map shows that Colombia and Venezuela differ from all their southern neighbours in that they border upon the Caribbean Sea, that Mediterranean Sea of the New World which stretches between the two continents. Thus these two republics complete the circle of that Mediterranean system of lands—the Antilles, Mexico, Central America, Panamá—in which the United States are the dominant Power and in which Great Britain, France and Holland are also members—one may perhaps say subsidiary members. Thus each of these republics of the Spanish Main has a dual character. They are on the one hand South American continental states; but their coasts also face the coasts of the United States, and their borders, to east and west, touch lands which are not purely Latin-American in character. Venezuela, both historically and actually, faces both ways. On the one hand she is the country of the Orinoco, of a vast continental interior: on the other hand she belongs also to the Antillean system: her eastern neighbour is British Guiana, and her territory almost locks fingers with the British island of Trinidad, which is in some sort the distributing commercial centre for all the Spanish Main. Thus Venezuela completes that long Antillean chain which curves from Florida to the Spanish Main, a chain whereof several links are in the possession of the United States. This dual character stands out in the early history of the country. For, during most of the colonial period, Venezuela was the only part of South America not attached to the Viceroyalty of Lima. Eastern Venezuela depended on the Audiencia of Santo Domingo and was thus connected with the Antilles and with the Viceroyalty of Mexico, that is to say with North America. Then followed a period of dependence on the Viceroyalty of Santa Fé de Bogotá, until finally Venezuela was erected into a separate Captaincy-general.

In the Republic of Colombia the dual position has been forced into prominence by recent events. On the one hand Colombia is a Pacific state, an Andine and continental country; yet her chief ports and arteries of communication lead northwards; and, until fifteen years ago, she bestrode the Isthmus of Panamá. In 1903 that Isthmus passed under the control of the United States; and Colombia, which formerly included the province of Panamá, now practically has the United States for her nearest neighbour.

The connexion of these states with Europe dates from the first voyage of Columbus across the Atlantic and from Cabral's voyage to Brazil. The fabric of South America, as it stands today, was constructed in the main during the marvellous half-century from 1492 to 1542. During that time almost all the existing states took shape, and most of the present capitals were founded. That work is chiefly connected with five great names, Columbus, Balboa, Cortes, Magellan, Pizarro. Columbus and his companions or immediate successors founded the Spanish empire on the Antilles and the Spanish Main. Balboa sighted the South Sea, crossed the Isthmus, and claimed that ocean and all its shores for the Crown of Castile. Cortes established the empire of New Spain in North America. Pizarro, starting southwards from Panamá, discovered the empire of the Incas, shattered their power and set in its place a Spanish Viceroyalty.

The political divisions marked out at the conquest, which still subsist in the main, were determined by the course of exploration and conquest. When a separate condottiere hit upon a convenient site for a port and founded a city either upon the sea-board or in some inland situation accessible from the port, his work usually came to be recognised by the creation of a separate government. These conquistadores showed judgment and capacity in their choice of sites and in their marches inland, which naturally followed the most convenient lines of communication. In this way it came about that the political divisions in the Spanish empire were mainly determined by natural economic causes, acting through the rather haphazard experiments of practical men rather than through any deliberate theory. These natural economic conditions are permanent in character: they still persist, and they account in great part for the continuance of the chief political divisions after the achievement of independence and for the failure of ambitious schemes and aspirations after union or federation. Thus the separate "kingdoms" and "captaincies-general" of imperial Spain grew into states and are now growing into nations. An illustration may be found in the Australian colonies. In Australia, separate existence was at first an economic necessity, demanded by the early colonists, owing to the distinct paths of settlement and the distance between ports. Union, achieved later by means of federation, was the work of artificial efforts of statesmanship acting patiently through many difficulties.

The "Indies" were dependencies or possessions of Spain down to the nineteenth century. Viceroys, captains-general and governors were sent out from the Peninsula to rule in the capitals: corregidores held office in the smaller towns[1]: audiencias, at once tribunals and councils, were established in important centres. The course of trade was regulated and was directed solely to the Peninsula. But the strength and the basis of the fabric lay in the municipalities, which, although the councillors' seats were purchased from the Crown or inherited from the original purchasers, nevertheless offered some kind of public career to the inhabitants and afforded the means of local public vitality.

When Napoleon stretched out his hand upon the Spanish royal family and upon the Spanish kingdom, these municipalities everywhere became the channels of patriotic protest and resistance to French pretensions. Owing to the collapse of the monarchy, the unsympathetic and even hostile attitude of successive popular authorities in Spain, and the action of certain resolute leaders guiding the natural development of local activities, these movements in America soon shaped towards separation. In every capital the municipality formed the nucleus of a junta or convention, which first assumed autonomy and then was forced by the logic of events, and particularly by Spanish attempts at repression, to claim republican independence. The resultant struggle was shared in common by all. Buenos Aires, having worked out for herself a fairly tranquil and facile revolution, sent troops under San Martín to aid Chile and to invade the royalist strongholds of Peru. Bolívar, the Caraqueño, liberator of the Spanish Main and of Quito, sent his soldiers southwards through Peru. Finally, Venezuelans and Argentines, from opposite ends of the continent, stood side by side in that battle on the Andine heights of Ayacucho which ended the Spanish Viceroyalty of Peru and the Spanish dominion on the continent. The peoples of South America, through all subsequent divisions, have never quite forgotten that in those days they made common cause and united in a combined effort to lay the foundations of what might be a common destiny.

The emancipation of Mexico was a separate movement, which followed a rather different course owing to the Indian origin of most of the population. The issue was confused and hindered by early outbreaks, which were in great part Indian insurrections and class conflicts not directed to any clear aim and tainted by brigandage. An attempt was made to cut the tangle of conflicting interests by the establishment of an independent Mexican monarchy. In 1823 this was overthrown by a military revolt, which started the Mexican republic on its stormy career. The movement of separation from Spain inevitably embraced also the Captaincy-general of Guatemala, which chose separation from Mexico, and assumed the name of Central America—an artificial political term rather than a geographical description. Its five provinces eventually separated into the five republics of Central America.

Events in Brazil shaped themselves differently. Upon the French invasion of Portugal in 1807-8, the Portuguese royal family migrated to Brazil and made Rio for a time the capital of the Portuguese dominions. When King John VI returned to Lisbon in 1821, he left as Regent of Brazil his son Dom Pedro, who, a few months later, supported by Brazilian opinion, threw off allegiance to his father and declared himself an independent sovereign. Thus was established, or rather continued, that Brazilian monarchy which subsisted down to 1889 and which secured to that country tranquillity and a continuous though rather sleepy progress during the stormy period through which Spanish America passed after the achievement of independence.

For the long struggle had been mainly destructive. It had not only swept away Spanish authority, but had blurred and in some parts had erased all authority, all stability and order, had confused or obliterated whatever had existed of political experience or tradition, and had left the ignorant masses a prey to theorists and adventurers. The result was that, for at least a generation after the achievement of independence, most of the Spanish-American states were agitated by a turmoil of multitudinous constitutional experiments, confused conflict and destructive civil war, alternating with periods of rigorous and often tyrannical personal despotism. These movements have been perhaps unfairly judged in Europe. The young communities of Latin America, wanting in political experience and torn by a long and unavoidable struggle, were engaged in sweeping up the débris of their great revolution.

The Republic of Chile in great part escaped that turmoil through the establishment, after a brief period of conflict, of a fairly stable aristocratic oligarchy of landed proprietors. Her three "revolutions" have been landmarks rather than interruptions in her historical development; for they were brief, decisive and conducive to a clearer constitutional definition. Argentina, after the fall of the Dictator Rosas in 1852, began to feel her way towards union and order, and may be said to have achieved that end with the general acceptance of her completed Federal Constitution in 1880. In the tropical republics constitutional agreement was rendered more difficult by the mixture of races, by geographical and climatic obstacles and by a comparative remoteness from European influences. And in the Caribbean lands our own generation has seen Presidential seats occupied by despots of the old type, usually men of imperious and resolute character, dauntless courage and unscrupulous indifference respecting means and methods, men sometimes risen from the lowest station through ruthless force and cunning. Indeed, Mexico, after a period of remarkable economic development under the long autocracy of Porfirio Diaz, relapsed, upon his fall in 1910-11, into the condition of a century ago.

Yet it may be generally said that the decade following 1870 was the beginning of a new era for the Latin-American republics. The extension of steam navigation, the building of railways, machinery applied to agriculture, the influx of immigrants from Southern Europe and of capital from Northern Europe, the growing demand in Europe for foodstuffs and raw materials—all these things favoured, particularly in the south temperate zone, a rapid and very remarkable economic development which accompanied and aided a consolidation and closer cohesion of the social and political fabric.

The outstanding fact in the recent history of Latin America and in her present relations to the war is this economic development, this great creation of new wealth during the past generation. It has been described in many modern books upon the various republics, and can be studied in Consular Reports, which read like romances. The Pampa has become one of the chief granaries of the world; and Buenos Aires, the greatest city of the southern hemisphere, is the centre of a railway system almost equal in extent to that of the United Kingdom. Chile has been enriched by nitrate and copper, Brazil by coffee and rubber. The High Andes have become once more a treasure-house of mineral wealth: tropical hills, valleys and coastal plains yield the riches of their vegetable products.

The date assigned above as the beginning of this great economic increase is the date when the modern German Empire came into complete being. The recent growth of Latin America coincides with the birth and growth of the German industrial system. The organised energy, the patient assiduity, the expanding productiveness of Germany found a great opportunity in meeting the new needs of these rapidly growing countries. Germans won a remarkable position in those lands and had marked out for themselves a yet more ambitious future.

During the same period the United States, having decisively consolidated the Union, has taken its place among the great Powers of the world. That republic has also altered its economic character: for whereas previously the inhabitants had been principally engaged in the internal development of a vast territory and had been exporters mainly of foodstuffs and raw materials, the growth of population has turned them into a commercial people exporting manufactured goods. This dual development, political and economic, has profoundly affected the relations of the United States with Latin America.

Meantime the long-standing and intimate connexion between these lands and the maritime countries of Western Europe has followed a natural and uninterrupted course suffering no signal change except that, quickened by a newly-awakened and more active interest on the part of Europe, it has become closer, more sympathetic and more firmly based upon mutual respect and understanding.

It is the object of the following pages to examine these matters with reference to the Great War, and also to consider generally the bearings of the war upon the development of the Latin-American countries.

In estimating the bearings of the great war upon these countries, it is necessary to review certain political forces and currents of public thought, which the Germans have attempted to divert to diplomatic or bellicose ends. Since these influences date in part from the era of independence or even from an earlier date, clearness of vision demands some historical retrospect. When, upon the achievement of independence, schemes of Latin-American or of South American union were found impracticable, it was inevitable that frontier disputes and national rivalries should lead to tension and sometimes to wars between states. When it is remembered that every one of the ten South American republics was divided from several neighbours by frontiers partly traversing half-explored and imperfectly mapped regions, it is perhaps surprising that such questions have been on the whole so amicably settled, and that those which are still pending do not appear to be menacing or dangerous. Owing to the paucity of population on the ill-defined and remote interior frontiers, many of these questions did not become urgent until the latter part of the nineteenth century, when the increasing seriousness of political interests, the steadying influences of material growth, and the pressure of outside opinion favoured peaceful settlement, usually by means of arbitration. It would be possible to compile a formidable list of such disputes. Most of them are questions concerning historical and geographical delimitation, of great local interest, but hardly of world-wide significance, although for a time the world was alarmed lest the frontier dispute of Argentina and Chile should excite a conflict between the two peoples engaged in the development of the south temperate zone, the natural seat of an important trans-Atlantic European civilisation.

A good example of the character of such frontier questions, of their mode of settlement and of their possible exploitation for Teutonic purposes is to be found in the long-protracted dispute concerning the boundary between Venezuela and British Guiana—a dispute which only became acute when gold was discovered in the region under debate. In deference to external influence, the whole question was submitted to arbitration, and was decided according to historical evidence concerning the early course of settlement. This example is of further interest as illustrating the German method of seizing opportunities. For, today, German propaganda seeks to revive the bitterness of this episode, and cultivates the favour of Venezuela by holding out the prospect of the enlargement and enrichment of that republic through the absorption of British Guiana and Northern Brazil; just as the neighbouring Republic of Colombia is assured that German victory and the humiliation of the United States will mean the return of Panamá to Colombia. It would be unwise to dismiss such persuasive lures as too fantastic even for the tropical atmosphere of the Spanish Main. Wherever opportunities occur, similar efforts are made to turn to account national jealousies, resentments and ambitions, and particularly to exacerbate the relations between Brazil and Argentina, between Peru and Chile, between Mexico and the United States.

The rivalry between the Portuguese and Spanish elements in South America dates from early colonial times; and, as often happens in disputes between members of the same family, has been perhaps more warmly felt than the historic rivalry between Anglo-Saxon and Latin in America. The feeling was kept alive after emancipation by a dispute concerning the possession of the Banda Oriental (now the Uruguayan Republic), which geographically belonged rather to the Portuguese or Brazilian system, historically to the Spanish or Argentine system. During the eighteenth century Spaniards and Portuguese had disputed its dominion in a series of rival settlements, of wars and treaties, which finally left Spain in possession. The struggle for emancipation reopened the question. For three years (1825-28) Argentina and Brazil fought for possession. The quarrel was adjusted, through the mediation of British diplomacy, by the recognition of the Banda Oriental as a sovereign republic. Twenty years later, Rosas, dictator of Buenos Aires, attempted to reverse this decision by force of arms. His fall, partly brought about by Brazilian intervention, settled the question. But it has left traces upon the vivacious local sentiment of those young countries.

Again, the war which Chile waged in 1879-83 against Bolivia and Peru ended in the occupation by Chile of Western Bolivia and also of the two southern provinces of Peru. The ultimate possession of these two provinces is still under discussion. Meantime, they remain in Chilian hands; and, although a friendlier atmosphere now prevails, diplomatic relations have never been resumed between Peru and Chile.

In these inter-state questions Germany seeks her opportunity for fishing in troubled waters. German diplomacy and propaganda have striven to reopen these old sores and to impede Latin-American consolidation by setting state against state, and by fomenting or reviving latent ambitions of hegemony or aggrandisement. Those who favour Germany are to win great territorial rewards, at the expense of their misguided neighbours, upon the achievement of that German victory which is represented as certain. Particular efforts have been made to embroil Argentina with her neighbours; a prominent feature of this programme is the dismemberment of Brazil.

But the most important of these political movements and the one which seemed to offer most promise to German schemes, is the long dispute between Mexico and her northern neighbour. This is a part of that process which since the beginning of the nineteenth century has radically altered the map of the Caribbean lands and has shifted the whole weight of political influence in that region. The chief effort of Germany is to exploit the historic rivalry between Anglo-Saxon America and Latin America, and to separate north from south by reviving the smart of past incidents and by stirring up apprehensions as to the future.

Here, again, it is necessary to glance back and summarise the chief actual events of that history[2]. When Latin-American independence was achieved, between 1820 and 1824, the United States had already become the dominant power on the Mexican Gulf by the acquisition of Louisiana and Florida, and in 1826 she exercised the privileges of that position by prohibiting Mexican and Colombian designs for the emancipation of Cuba. In 1845 Texas, which nine years before had seceded from Mexico, was admitted to the Union, and in 1846-48 half the territory of the Mexican Republic was transferred to the United States by a process of conquest confirmed by purchase.

A pause in advance followed, until events showed that Isthmian control was a national necessity to the United States. It suffices here to note the conclusion of a long diplomatic history. In 1903 the United States, having failed to obtain concessions of the desired kind from Colombia, supported the province of Panamá in her secession from Colombia, and speedily obtained from the newly formed republic a perpetual lease of the canal zone, together with a practical protectorate over the Republic of Panamá. The United States then proceeded to construct and fortify the canal. She also procured from Nicaragua exclusive rights concerning the construction of any canal through Nicaraguan territory, and erected in fact a kind of protectorate over that republic.

Meanwhile, in the Antilles events were shaping towards control from the north. A long-standing trouble concerning Cuba culminated in the Spanish-American War of 1898, which brought about the annexation of Porto Rico and the Philippines to the United States, while Cuba became a republic under the tutelage of that Power. Five years later the United States, in order to save the Dominican Republic from European pressure, undertook the administration of the revenues of that state. In 1915 she interposed to suppress a revolution in Haiti. Finally last year (1917) she purchased from Denmark the islands of St Thomas and Santa Cruz. Recent rumours as to a proposed further purchase—that of Dutch Guiana—have been officially denied.

These advances have not gone beyond the Caribbean area, where geographical conditions place the United States in a dominant position. Her relations with the more distant southern countries, not touching the Mediterranean Sea of the New World, fall into a different category and do not directly concern the immediate topic.

But in the Caribbean area the United States has established a Sphere of Influence, not indeed explicitly defined as such, but recognised in effect by other governments and accepted by some at least of the republics occupying that region. The events of the last twenty years further indicate that the United States is undertaking the obligation, usual in such cases, of imposing a "Pax Americana." As in similar instances elsewhere, this Pax Americana has not quite clearly marked its geographical limit, nor is it guided by any theoretical consistency, but rather by the merits of the case and the test of immediate expediency in each instance. Thus, whereas the United States enforces peace in Haiti and definitely undertakes to maintain internal tranquillity in Cuba, she has on the other hand withdrawn from interposition in Mexico. The outside world has, on the whole, treated these matters as the concern of the United States and respected the working of the Pax Americana.

Meanwhile, geographical proximity has favoured North American commerce, and in recent years more than half the trade of Central America was carried on with the United States.

It has been necessary to define the situation, because it is accepted by the Allies, while it is at the same time jealously assailed by Germany.

For Germany, too, has won a remarkable position in the same region by her economic efforts, which have also their political side. On the one hand Central America is in a kind of dependence upon the United States: on the other hand, it has been said, with obvious exaggeration, but with some epigrammatic truth, that Guatemala before the war had become a dependency of Germany in everything but the flag. German intelligence and industry had seized the opportunity offered in the recent development of a comparatively backward region. Peaceful penetration was a work of methodical effort, of organised combination. German firms, mostly of recent origin and sprung from small beginnings, always preferred to import from Germany in order to favour German trade. Indeed they were bound to do so by the terms of the credit granted to them by German banks or Hamburg export firms for starting their business. Young men came out from Germany—serious, plodding youths, working for small pay, taking few pleasures and immersed in business. German retail houses, either newly established or formed by the insinuation of Germans into native families or native firms, worked in close contact with the importing houses. The shipping companies worked with these latter and with the Hamburg firms. The chief German achievement in this region was the control of the coffee industry, which was acquired by the usual German combination of admirable industry, patience and intelligence with unscrupulous greed and cunning. Germans advanced money to the grateful owners of coffee estates on such terms that the native owner in course of time found himself bound hand and foot by ever-increasing debt; and the properties usually passed into the hands of the exacting foreign creditor, the former owner being often kept on as paid manager. In this way, besides doing a good stroke of business for himself, the German served Germany by increasing German interests in the country, providing cargo for German ships and helping to secure for Hamburg the coffee market of Europe. Every little advantage gained by an individual German was reckoned as a national gain, as the starting-point for another German step forwards. Nor was German advance confined to Guatemala: it penetrated all Central America as well as Mexico and the Antillean Republics, especially Haiti.

But the maritime war, the British blockade and Black List and, finally, the participation of the United States have shaken the fabric thus laboriously raised. German ingenuity had overreached itself. For it was the insidious and cruel method of German land-grabbing in Guatemala which more than anything determined that republic to declare war, in order to escape from this ignominious economic dependence, this foreign control of a national industry. For it would be difficult to define a clear casus belli. But in the peculiar form of her declaration of war she told the world under which system she chose to live. For in April 1918 Guatemala announced that thenceforth she occupied the same position as the United States towards the European belligerents.

The iniquity of North American intervention in Nicaragua and the implied menace to other states were insistently preached by Germany throughout Central America; yet, a month later, Nicaragua also declared war, proclaiming at the same time her solidarity with the United States and with the other belligerent American Republics.

In Costa Rica the Germans represented the non-recognition by the United States of President Tinoco, who owed his position to a coup d'état, as a menacing insult to that Republic. Then, the same Germans intrigued to overthrow Tinoco on account of a Government proposal to tax coffee stored for future export. The upshot was that, in May 1918, Costa Rica declared war. Two months later Haiti took the same decisive step, and also Honduras.

The significance of these additions to the belligerent ranks is perhaps hardly realised in Europe. Every one of them is a serious reverse in the economic war which Germany is waging, and every one makes it more difficult for Germans in America to keep up communication with Hamburg.

Indeed, the tale of recent events reads like a mere series of German reverses, snatching away advantages already gained. In 1912, the treaty for the American purchase of the Danish Antilles was all but complete, when German influence in the Upper House of the Danish Parliament prevented ratification and thwarted, for the time, the plans of the United States. During the present war, the purchase was completed, Germany being impotent. Again, Germany, having acquired a strong position in Haiti, designed that the Haitian Republic should become a Teutonised base of activity, repudiating the Pax Americana and threatening the security of American sea-paths. The United States put out a hand, and this highly-coloured vision faded away. Cuba, Panamá, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Haiti, Honduras—all of these in turn struck at Germany through the declaration of war[3].

Yet Germany, beaten from point to point, still holds her ground in Mexico. One of the curious side-scenes of the great war was the attempt of the German Foreign Office to contrive an offensive alliance of Japan and Mexico against the United States. Mexico was to be rewarded by the recovery of Texas. This underhand plot against a neutral nation at peace with Germany collapsed at its inception. Yet the present German menace in Mexico is not to be despised. The rulers in the Mexican capital exhibit an ostentatious cordiality towards Potsdam and sometimes an almost petulant impatience towards the Allies. The German is the favoured one among foreigners in the republic. Supported by the German Legation, the German banks, and the countenance of the Mexican authorities, Germans are strengthening their economic hold, particularly through the acquisition of oil and mining properties. This advance has its political side: for hopes seem to be entertained that a militant power, inspired by Germany, may press upon the long southern frontier of the United States, disturb her pacific influence in the Antilles, threaten the security of her maritime routes, and interpose a barrier between her and her scientific frontier on the Isthmus of Panamá. Such schemes may sound fanciful, and no doubt in their entirety they are impracticable. But it would be a mistake to regard Germany as powerless or to undervalue her tenacious and intelligent opportunism. And, in any case, the economic position demands attention.

A word may here be said about the German effort to hold up before the eyes of all South America the spectre of the "Yankee peril." These German efforts have not succeeded, as will be shown later. Yet it would be rash optimism to assume that they have won no temporary success. Correspondence published by the Washington authorities shows that the German Minister at Buenos Aires succeeded in inducing the Argentine Government to approach Chile and Bolivia with a view to a combination against the United States—a scheme which, if carried through, might have produced a split in the political system of the South American Republics. A similar tendency appeared in President Irigoyen's attempt to convoke a conference of neutral American states, an attempt which has had no result except the dispatch of Mexican missions to Buenos Aires. Such incidents cannot be ignored: they illustrate a movement which is not quite effete.

From what has been said above it is obvious that German designs in Central America and the Antilles are not quite recent in their inception. The same is true of another field which for a generation past has attracted German ambitions. The flourishing self-contained German-speaking communities in Southern Brazil offered an attractive goal to an empire which was feverishly building ships, pursuing a maritime future and hunting for colonies. Here was a German colony in existence and almost constituting already an imperium in imperio. German emigrants, brought out by the Brazilian Emperors between 1825 and 1860, had by thrifty and intelligent industry done much to develop the south; and their descendants—now estimated to number 400,000—inhabited German towns, with German schools, newspapers and churches, where even proclamations of the Brazilian Government were published in German. Although not a product of the modern German Empire, this Deutschtum im Ausland has been studiously cultivated by that empire through every possible agency, and especially by imperial grants to German schools, whose pupils were taught that they were Germans owing a prior allegiance to Germany. Some hope was entertained of carving a Teutonic state out of Brazil, perhaps to form nominally, at all events for a time, an independent republic. The disturbances in the south which followed the establishment of the Brazilian Republic appeared to favour this chance, which depended however on one condition, the countenance of Great Britain in order to cope with the opposition of the United States. But in any case the vigour and increase of the German element was to dominate Southern Brazil and help to bring that region into moral dependence upon Germany. That these designs were not viewed in South America as wholly imaginative, is proved by a recent incident. The Uruguayan Government, after revoking neutrality and seizing the interned German ships, asked and obtained an assurance of Argentine support, in case Uruguayan soil should be invaded by Germans from Southern Brazil. It may be added that recent German commercial penetration has been particularly active in Brazil.

Owing to their remoteness and lesser numbers, the German communities in Southern Chile—whose first founders emigrated from Germany after the troubles of 1848—did not invite such large political designs, although there is reason to think that in the earlier part of the war, when a German war fleet still kept the sea, the manifold activities of Germany included some notion of obtaining a permanent footing in the Pacific. These German-speaking settlements have been carefully cultivated, by the same methods as those used in Brazil, to become a Germanising force in Chile and a German outpost on the west coast. In 1916 a Chilian-German League was established, to include all persons in Chile of German origin and language, with the intention that the members should use their influence as Chilian citizens, especially at election time, on behalf of German interests.

Another influence which Germany strives to turn to account is the recent movement represented by the Unión Ibero-Americana, which seeks to draw together Spain and the Spanish-American republics. The German efforts to give a Teutonic tinge to the present Spanish movement of national revival look also towards Latin America, in the hope that friendship with Spain may tell against French and North American influence; and attempts are being made to exploit for that purpose the Ibero-American celebration which is to be held in Madrid in October, 1918.

Lastly, in estimating political forces which have to be reckoned as factors in the conflict, some mention should be made of the very warm sentiment towards France which has prevailed for generations among educated South Americans—a sentiment which passes the bounds of mere private or even semi-official relations. This feeling is not universal, and would hardly be admitted in clerical and military circles. But it is sufficiently strong and general to be remotely compared to the sentiment which a Greek ἀποικία usually entertained towards the mother-city. French thought permeates the work of Latin-American historians and political writers. French example and theory mould the form and the action of governments. Paris is felt to be the capital and the centre of inspiration for Latin civilisation. The debt of South America to France has been generously, and indeed affectionately, avowed by a succession of Argentine writers. A recent German semi-official utterance openly admits and deplores the historic attachment of South America to France. This attitude towards France can hardly fail to have some public weight; and there is no doubt that the course pursued by Brazil has been partly inspired by love of France.

"South America is the special theatre and object of German commercial industry." This emphatic declaration—reiterated in various forms by other German authorities—is the theme treated by Professor Gast, Director of the German South American Institute at Aix-la-Chapelle, in a pamphlet entitled Deutschland und Süd-Amerika, which may be regarded as a semi-official exposition of German objects and opportunities. The pamphlet appeared in the latter part of 1915. The events which have since occurred, however damaging they may be to German hopes, do not affect the views expressed. Since this advice from a German authority to Germans is a frank revelation of German views, it seems worth giving a very brief abstract of the main points, which the writer elaborates at great length, though he does not enter upon details of business method.

"The German Press," says Professor Gast, "has never published so much about Latin America as during this war. This proves the importance of German relations there and the need of clear ideas concerning them. An economic competition, intense beyond all example, has sprung up concerning Latin America. The chief feature is the 'Financial Offensive' of the United States. The present grouping of competitors is accidental and false. The natural conflict is between the United States on the one side, and on the other side all industrial and exporting peoples, including Japan. The United States, the most dangerous competitor, is handicapped by the higher cost of production in North America and by the want of that facility of adaptation to customers' needs in which Germany excels. Yet the war has revealed the weakness of German reputation. Everywhere the prevailing strain is antipathy to Germany. It is the duty of Germans to put aside resentment and to strengthen their economic position. For trade with the two Americas is the chief source of prosperity for modern German commerce, particularly that of Hamburg. And after the war this trans-Oceanic trade will be a matter of yet more urgent national importance."

This general survey is followed by an examination of special opportunities open to Germans. "Germany has not the many-sided relations with Latin America possessed by the Latin peoples of Europe, nor the politico-geographical advantages of the United States, nor the strong capitalist position of Great Britain. She must make the most of what she does possess. Her main asset is the German in South America. Every German abroad means the investment of interest-bearing capital for German cultural expansion. Two things are required of him, to win esteem by good work and to place his personal influence at the disposal of German national ends. The compact German communities in Brazil and in Southern Chile should be supported and organised from home, but not obtrusively, lest local feeling be aroused. They may perhaps serve Germany best by a partial mingling with the native population, so as to spread German culture and the taste for German goods. But, everywhere, all individual Germans are Germanising agents. The German merchant particularly is the missionary of cultural and political influence. So also the German soldier, particularly the German officers employed as instructors in Chile and Argentina. Most South American officers feel a professional sympathy for Germany. Hence spring useful personal friendships: to foster and enlarge these is an urgent duty. Germans exercise other professions which facilitate the patriotic diffusion of German culture. Such are physicians, who find peculiar opportunities in their intimate relations with families in their homes; the clergy, both Protestant and Roman Catholic; teachers, whose proved idealism is an admirable equipment for the spread of German culture; scientific men, journalists, surveyors, geologists, professors in training colleges. If possible they should work in combination, as they do in the German Scientific Club of Buenos Aires. Every one of them must use every professional opportunity and every item of personal influence and private friendship for the advantage of Germany.

"A knowledge of German culture must be spread by a systematic educational movement. But this must be done tactfully. The German's propensity to foreign studies will aid him. He must equip himself by assimilating Latin culture, must use his knowledge of French culture, must oppose French influence by encouraging Spanish culture. His object is to catch souls; and, next to financial strength, the first necessity is tact."

Two points stand out in this very candid statement. First, every German abroad is an item in the national balance-sheet; he must earn interest. The intimacy between the pastor and his flock, the physician's intercourse with his patient, are set down on the credit side of the national profit-and-loss account. Secondly, the most profitable method is a liberal education. There is something whimsical in the combination of inhuman material calculation with humanising influences, and one may smile at the heavy solemnity of the suggestion that the German will find it pay to acquire tact and to Latinise himself for outside intercourse. But the suggestion should not be dismissed as absurd. Whatever can be done by effort, study, and will-power the German will do. He is training himself to be a more formidable competitor than ever in the economic arena.

Indeed, the pamphlet is valuable, not only as a hint for the future, but also as an avowal of methods which are already at work. One of these is a deliberate system of politic and profitable marriages. German clerks receive promotion only on condition that they marry native girls and establish homes in the country. This policy has been so steadily pursued that everywhere German business men have entered Latin-American families and exercise a Teutonising influence. Through marriage also, accompanied by skilled and profitable management, Germans acquire control of property and of trading concerns. Again, owing to their reputation for expert efficiency and scientific competence, Germans fill many posts of influence and trust in universities, scientific institutions and government departments. Argentina is an example. In the National University Germans control the engineering and chemical sections, where their pupils are trained to use German apparatus and methods. German curators in the Geological Museum receive early information as to any discoveries of minerals or oil. Germans employed as experts in the public service learn details of any public works proposed by the government or the municipalities. Reports on such schemes pass through their hands and, since estimates are not carefully checked, they are thus able to favour German trade at the expense of the Argentine tax-payer.

In every city the German Verein unites the German community, so that Germans may avoid competition and may co-operate with one another and with Germans in the Fatherland. The bank and the merchant work in close combination and have at their disposal all the information gathered by German employees in other banks and in business firms. The German has been quick to anticipate others in occupying new ground: for example, in the remote but vast and productive region of Eastern Bolivia, watered by the three great navigable affluents of the Madeira, a region which is just beginning to awake to the promise of a great future, the German trader hitherto has scarcely had a competitor. Again, the German has won predominance in the electrical and chemical industries by applying his practical scientific aptitude to the supply of new wants. Lastly, the German is distinguished by close attention to detail and adaptation to local needs.

Yet Germans note and deplore "a constant strain of antipathy to Germany, a wave of anti-German hate." The remedies suggested are: first, a more efficient German service of news, and secondly, "a systematic cultural activity, conducted with push and comprehensive inspiration."

What is being done in Germany to realise these methods? First may be mentioned the various associations for extending German influence abroad and binding to the Fatherland all Germans living abroad, whether in South America or elsewhere. Such are the Pan-German League, the German Navy League, the League for Germanism abroad, the League for German Art abroad, the School League which gives support to German schools outside Germany, the German rifle club, with its headquarters in Nuremberg, to which rifle clubs abroad are affiliated, and, lastly, the Foreign Museum, recently founded under the highest official patronage, which arranges economic exhibitions in various German cities. Although these associations were not founded particularly for Latin-American objects, their present efforts are particularly bent in that direction, as the Pan-German League lately declared. But, besides these comprehensive agencies, Germany possesses three institutions specially devoted to Latin-American purposes. One of these existed before the war, namely the German South American Institute at Aix-la-Chapelle, to which the Imperial and Prussian authorities have entrusted "the cultivation of scientific and artistic relations with South and Central America on the lines of a general cultural policy." Its objects are to draw together German and South American students, to maintain a South American library and information bureau, to encourage in Germany the study of South American matters by prize essays, travelling scholarships and similar methods, and to use every means of making German intellectual work known to South Americans. The Institute publishes a Spanish monthly illustrated periodical, El Mensajero de Ultramar, and also a Portuguese version, O Transatlántico. These papers are well calculated to uphold German culture across the Atlantic: they are admirably got up and aim at presenting an attractive picture of German life and institutions, dwelling particularly on the steady continuance of German industry, artistic production and even sport during the war. The Institute also publishes a German periodical, strictly business-like and containing only technical illustrations, for the purpose of keeping Germans informed on Latin-American affairs.

The Institute at Aix, although its ultimate object is mainly economic, leaves business methods and matters of immediate economic concern to other agencies. Before the war there flourished already in Germany a League for Argentina and one for Brazil. In 1915 these two Associations combined in order to form a German Economic League for South and Central America. A prospectus was issued and a meeting was held in Berlin under the presidency of Herr Dernburg, who spoke of the coming economic struggle and pointed out that German trade, except in the electrical industry, was not supported by large capital investments such as their rivals possessed. The dependence of South America on other industrial nations, owing to want of coal and iron, would facilitate German investment, to supply this defect. Germans had failed to make friends through not understanding the psychology of South Americans. German strength and practical energy must avoid arrogant pedagogic ways and must make their way through a tactful and sympathetic propaganda.

At this meeting the league was inaugurated with 120 members. Very soon it numbered 1000. Among the associations which figure as members are the German Industrialist League, the German Mercantile League, the Berlin Chamber of Commerce, the South German Export League, the League for Germanism abroad, the Society for German Art abroad. The three great banks, known in Germany as the three D.'s, are members, so also the great Shipping Companies; also newspaper and publishing firms; also many of the great industrial syndicates. A notable feature in the work of the league is the maintenance of a club in Berlin where business men and other travellers from South America are welcomed. A great point is made of this work of personal cultivation. The object is to make by hospitable attentions a Germanophil convert of every Latin-American visitor to Berlin and send him back across the Atlantic a missionary for German culture and German business. But the principal aim of the league is to unite all Germans who have any business interests in any part of Latin America, so as to pool together their knowledge, their resources, and their efforts. In this economic war the Germans move, as it were, in mass formation. Branches of the league were speedily established in every one of the twenty-one American republics, and these branches co-operate actively with the parent society at home in the furtherance of German influence and economic advantage.

A third institution, the Hamburg Ibero-American League, has been formed in the metropolis of German Latin-American trade. Already before the war, besides the usual trading organisations of a great port, Hamburg possessed a Technical High School which is practically a university of trade and industry; a Seminary for Romance languages and culture, which maintains a South American library; and a singularly complete bureau of information concerning all over-sea countries, which is known as the Hamburg Colonial Institute.

But Hamburg still felt a want, which was supplied by the formation of the Hamburg Ibero-American League. Its objects are: (1) in Spain and Spanish America: to spread a knowledge of Germany's resources and to cultivate friendly relations in government departments, semi-official institutions and social, literary and scientific circles. To circulate the illustrated weekly El Heraldo de Hamburgo, also pamphlets in Spanish and Portuguese; to station confidential emissaries in appropriate posts; to encourage interchange of visits and to inculcate the advantages which Germany offers as a training-ground for every calling. (2) In Hamburg: to prepare for intercourse after the war by arranging lectures and by organising language courses in German, Spanish and Portuguese, and particularly to establish a Centro Ibero-Americano with club, reading room, and information bureau, a house fully equipped for the hospitable reception of travellers from the Peninsula and from South America. The league is to consist of twenty-two sections, one for Spain, one for Portugal, one for each of the twenty Latin-American republics, in order that all who have interests in any part of the Ibero-American world may support one another.

A fourth association, the Germanic League for South America, has been formed more recently for the purpose of uniting together persons of German speech and origin in Latin America and preserving their Germanic character, particularly by means of German schools. This institution has a special significance just at the time when the Brazilian Government has determined that all its citizens shall be Brazilians and nothing else.

The three leagues which have their headquarters in Berlin, Hamburg and Aix-la-Chapelle have been in active movement for some time, and there is evidence from South America that they do their work in a thorough and effective fashion and have won considerable success, particularly through cultivating the friendship of South American visitors to Germany.

But in estimating German designs, we must look beyond these German leagues, which are merely an incidental part of German economic organisation. That subject far transcends the present topic, but embraces it so closely that the main outlines may be indicated. Most of the German industries are consolidated into cartels or syndicates in such a way as to eliminate competition, regulate prices and output, distribute risks or losses, facilitate the export of surplus products, and apportion business between the members of the cartel. The whole body of industrialists is united in league; merchants or exporters are similarly united; a small group of great banks, practically constituting one power, manages the financial side of the national industry and commerce with a singular mixture of daring and judgment, guided by a wonderfully complete enquiry system, a veritable international secret service; the great shipping companies, which coalesce more and more into a single huge national concern, work in close co-operation with organised industry and organised trade; railway transport is managed by the state so as to dovetail into the same machine: and the whole forms altogether a carefully constructed system of co-operation, cohesion and united action. That organisation has not fallen into abeyance during the present war. On the contrary, month by month it is being perfected, rounded off. Lastly, Germany has appointed, as it were, an economic headquarters staff, a small group of expert business men who for two years past have been devoting themselves to the working out of means for transferring Germany from a war basis to a peace basis with the least possible disturbance and delay. This higher command has its hand upon the levers of the whole machine, which, upon the conclusion of peace, is at once to resume with redoubled energy its interrupted task, industrial and commercial recovery, and particularly the economic conquest of Latin America.

In order that we may know what Germany is doing, these German organisations have been noted here. It would be impertinent, in both senses of the word, to compare or to criticise British methods. The problem of British reorganisation is being studied by experts and worked out by those in authority, and it is constantly expounded in official publications. But, without attempting to give individual opinions, one may quote some of authority.

"Great nations do not imitate." We may learn much in detail from the Germans; but Englishmen could not adopt the German system unless by first turning themselves into Prussians. Our people would never submit to Prussian methods of state control. Moreover all British experience shows that in this country such control would be disastrous. Yet competent authorities agree that immediate organisation is a necessity. It cannot be beyond the wit of Englishmen to devise means whereby British individual enterprise, common sense and self-reliance may work through methods of systematic organisation, combination, united action. From the friends of Britain everywhere comes the same warning. It is most appropriate to conclude with one uttered by a South American of unimpeachable authority, Don Pedro Cosio, former Uruguayan Finance Minister, who recently represented the Republic of Uruguay in this country. In a report to his government on the organisation of labour in the United Kingdom he writes, "The nation which is the first to organise its industry for the commercial campaign will be the one which will occupy the forefront in foreign markets."

"Economic War":—This reiterated German phrase is not mere metaphor. The Germans pursued in peace the operations of war. To them commerce meant not merely the pursuit of trade in peaceful rivalry with others, but a sustained effort to defeat and oust rivals and reduce to economic subjugation the lands penetrated. By plunging into open war, which was meant to continue and to confirm that process, the Germans have risked their previous gains. Their own weapons are turned against them. The economic character of the actual war and the efficacy of the economic weapon in the hands of the Allies become more and more evident. In the early months of the war this weapon was not wielded with thorough decision, and Germans beyond the Atlantic were able to carry on considerable European trade. But today the German merchant is striving to defend, against an overwhelming weight of maritime pressure, the ground which he had won through a generation of laborious and patient effort.

This economic struggle covers all the shores of all the Oceans. Its Latin-American phase has a special interest owing to the remarkable position attained in those lands by the Germans, the high value which they attach to that position, and their special efforts to maintain it under present difficulties. The most varied ingenuity is called into play to circumvent the barrier which now cuts off those countries from Germany. Present risks and losses are viewed as part of the inevitable waste of war, as an outlay deliberately incurred in the all-important task of holding open the gate through which, upon the conclusion of peace, the fruits of German industry are at once to pour in an irresistible stream, in exchange for those raw materials which are urgently needed to feed the industrial life of Germany after the war. This is the constant preoccupation of German business circles—the need of raw materials. And this is the reason why Latin America, the great source of raw materials, is courted with eager hope and anxious apprehension.

It is noticeable that a very large part of the cargoes condemned by the British Prize Court, as actually intended for the enemy though consigned to other pretended destinations, consists of goods from Latin America. For example, in August 1917 the Court condemned quantities of coffee, seized on a score of neutral steamers and ostensibly consigned to Scandinavian and Dutch merchants, but in fact shipped by a German firm at Santos for the parent house in Hamburg. Two months later, it was stated in court that nearly £400,000 worth of wool, shipped from Buenos Aires to the Swedish Army Administration at Gothenburg, had been seized by the British as being in fact destined for Leipzig. At the same time the Court condemned a number of manufactured rubber articles which had been found concealed in a passenger's clothing. On a later occasion, coffee and cocoa valued at nearly £200,000 were condemned, being part cargo of a Swedish ship bound from California to Gothenburg. They were consigned by a new and insignificant firm in San Francisco to various persons in Scandinavia, but were in fact on their way from Guatemala to Hamburg through Sweden.

The elaborate webs spun by German traders and revealed by intercepted correspondence were exposed in the Prize Court. Their methods were to find persons in neutral countries as nominal consignees, to act as intermediaries for getting the goods to Germany; to set up bogus companies for the same purpose; to use false names, or names of persons having no genuine interest in the consignment, and to manufacture false documents in order to give the appearance of neutral business. This was done to evade capture by deceiving the belligerent searchers. In some instances these methods succeeded. Quantities of coffee, consigned to Scandinavia, managed to elude the allied warships and reach Hamburg.

These are cases of import into Germany. The reverse process, export from Germany through neutrals, follows similar lines. German goods, falsely labelled and described as Swiss or Dutch or Scandinavian manufactures, have found their way across the Atlantic in neutral ships.

The Post Office has also served as a channel of secret trade. Pictures in the Press have exhibited the odd ingenuity of these devices: how coffee from Brazil to Germany was found concealed in rolls of newspapers, and how thin slabs of rubber were sent by post as photographs, also how quantities of jewellery have been despatched from Germany for South America in letters and in bundles of samples or journals. Goods so sent from Germany through the Post Office are mostly such as combine small bulk with high value—especially drugs and jewellery.