1

PART I

THE WATERSHED

3

CHAPTER 1

Background to Military Assistance

The Geographic Setting—The People—Vietnam’s Recent History—Post-Geneva

South Vietnam—The American Response

The Geographic Setting

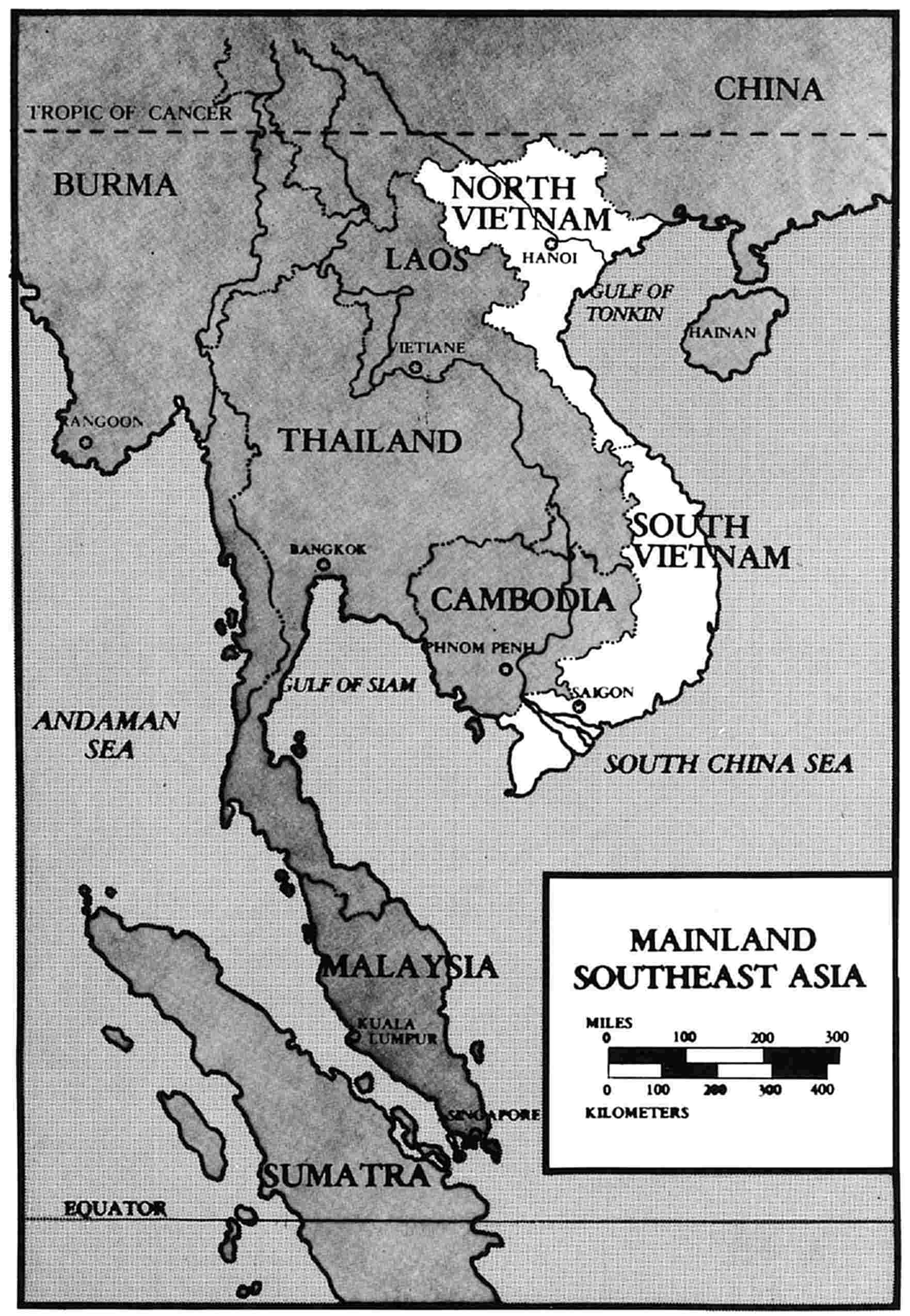

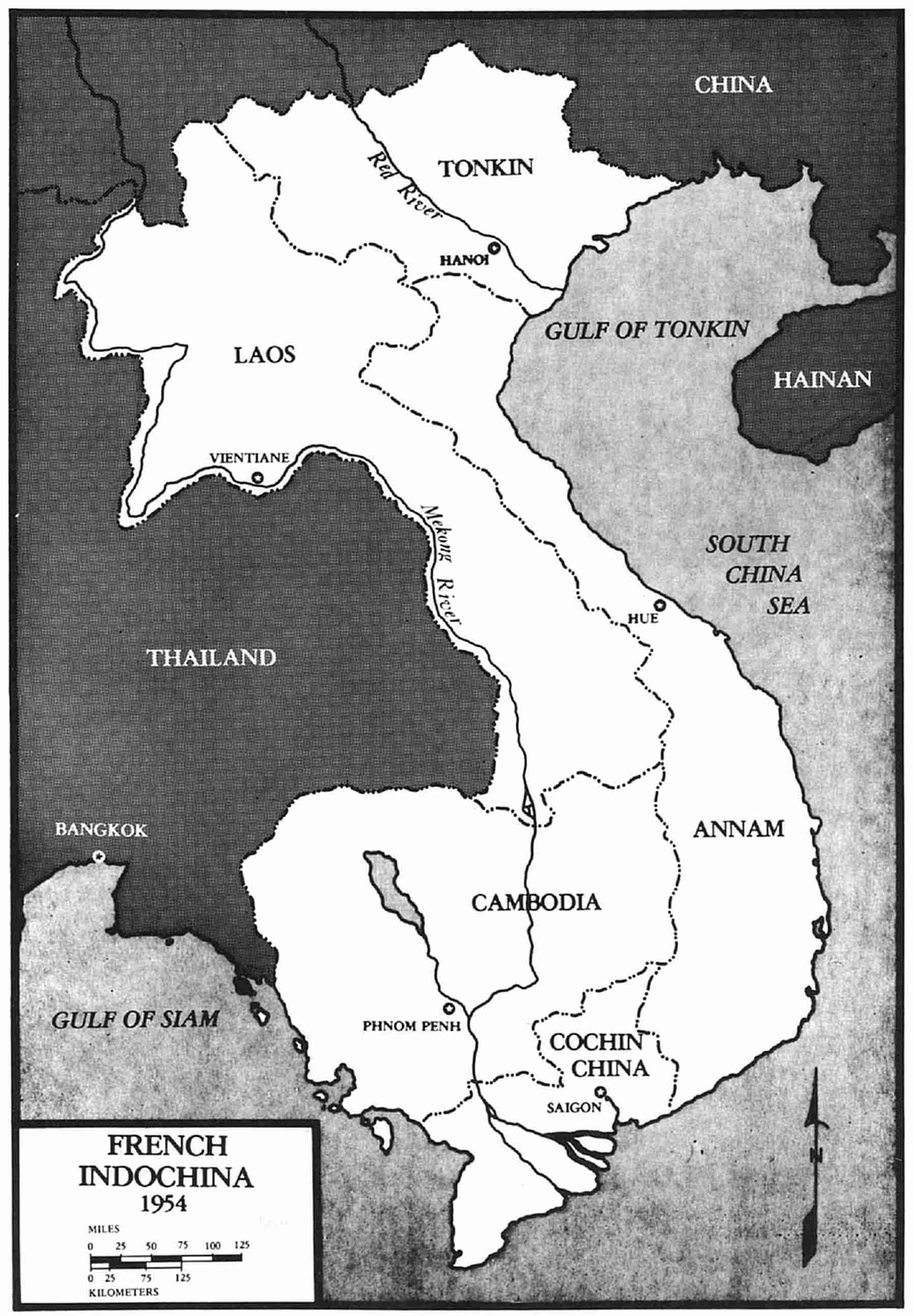

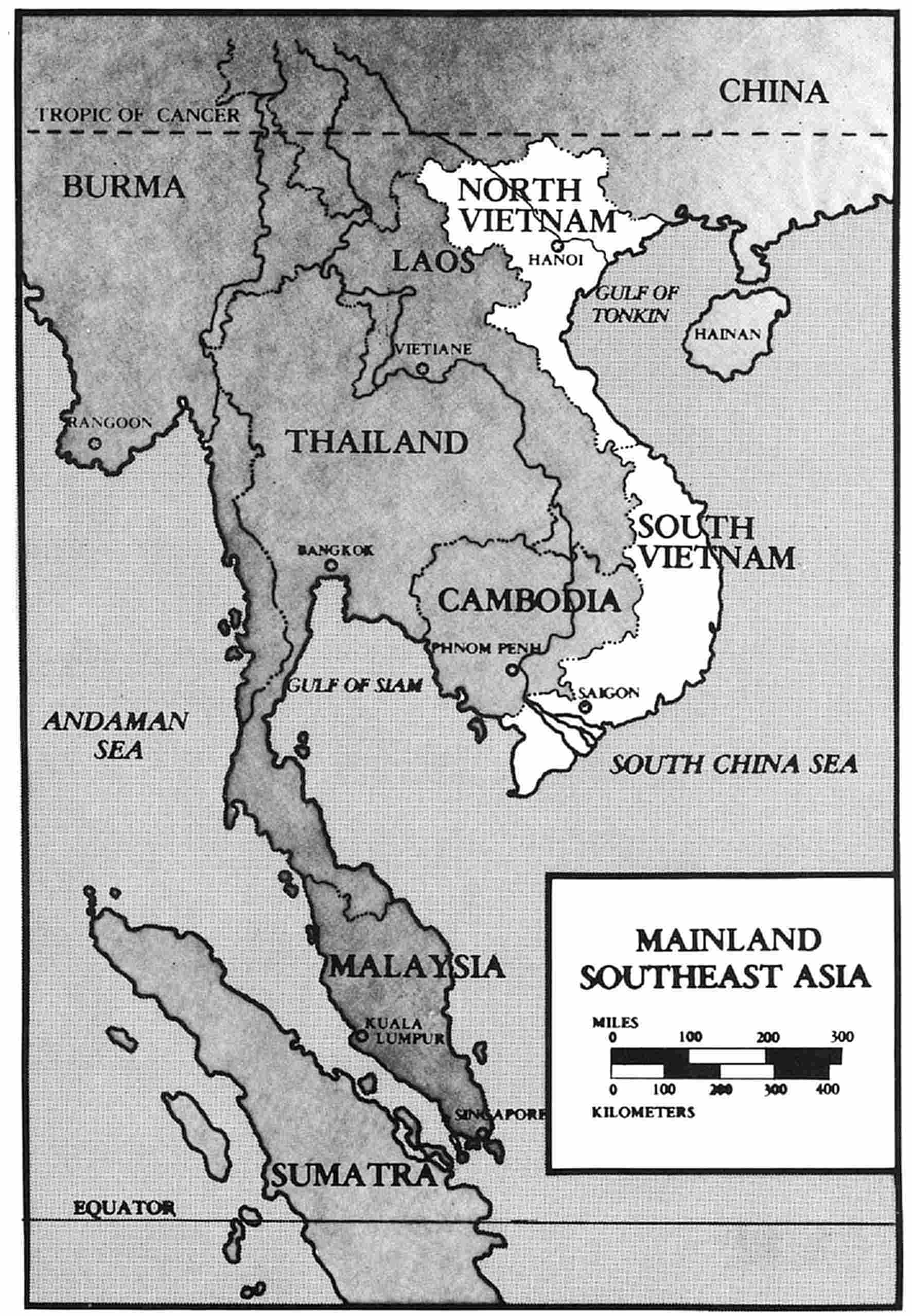

Hanging like a bulbous pendant from China’s southern border, the Southeast Asian land mass projects itself southward to within 100 miles of the equator. Often referred to as the Indochinese Peninsula, this land mass is contained by the Andaman Sea on the west, the Gulf of Siam on the south, and the South China Sea and the Tonkin Gulf on the east. Along with the extensive Indonesian island chain which lies to the immediate south, mainland Southeast Asia dominates the key water routes between the Pacific and the Indian Oceans. So positioned, the Indochinese Peninsula and the offshore islands resemble the Middle East in that they traditionally have been recognized as a “crossroads of commerce and history.”[1-1]

Seven sovereign states currently make up the Indochinese Peninsula. Burma and Thailand occupy what is roughly the western two-thirds of the entire peninsula. To the south, the Moslem state of Malaysia occupies the southern third of the rugged, southward-reaching Malaysian Peninsula. East of Thailand lies Cambodia, which possesses a relatively abbreviated coastline on the Gulf of Siam, and Laos, a landlocked country. The Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam), which borders to the north on China, and the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) form the eastern rim of the Indochinese Peninsula.

Vietnamese have often described the area currently administered by the two separate Vietnamese states as resembling “two rice baskets at the ends of their carrying poles.”[1-2] This description is derived from the position of extensive rice producing river deltas at the northern and southern extremities of the long, narrow expanse of coastline and adjacent mountains. Vietnamese civilization originated in the northernmost of these so-called “rice baskets,” the Red River Delta, centuries before the birth of Christ. Pressured at various stages in their history by the vastly more powerful Chinese and by increasingly crowded conditions in the Red River Delta, the Vietnamese gradually pushed southward down the narrow coastal plain in search of new rice lands. Eventually their migration displaced several rival cultures and carried them into every arable corner of the Mekong Delta, the more extensive river delta located at the southern end of the proverbial “carrying pole.” Although unified since the eighteenth century under the Vietnamese, the area between the Chinese border and the Gulf of Siam came to be divided into three more or less different regions: Tonkin, centered on the Red River Delta; Cochinchina, centered on the Mekong Delta; and Annam, the intervening coastal region.

MAINLAND

SOUTHEAST ASIA

FRENCH

INDOCHINA

1954

Since mid-1954 the area known collectively as Vietnam has been divided into northern and southern states. South Vietnam (known after 1956 as the Republic of Vietnam), where the earliest U.S. military activities were focused, came to include all of former Cochinchina and the southern half of Annam. The geography of this small state, described in general terms, is rugged and difficult. The lengthy country shares often ill-defined jungle boundaries with Laos and Cambodia in the west and with the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) to the north. Its land borders total almost 1,000 miles—600 with Cambodia, 300 with Laos, and roughly 40 with North Vietnam. Approximately65 1,500 miles of irregular coastline on the Tonkin Gulf and the South China Sea complete the enclosure of its 66,000-square mile area.

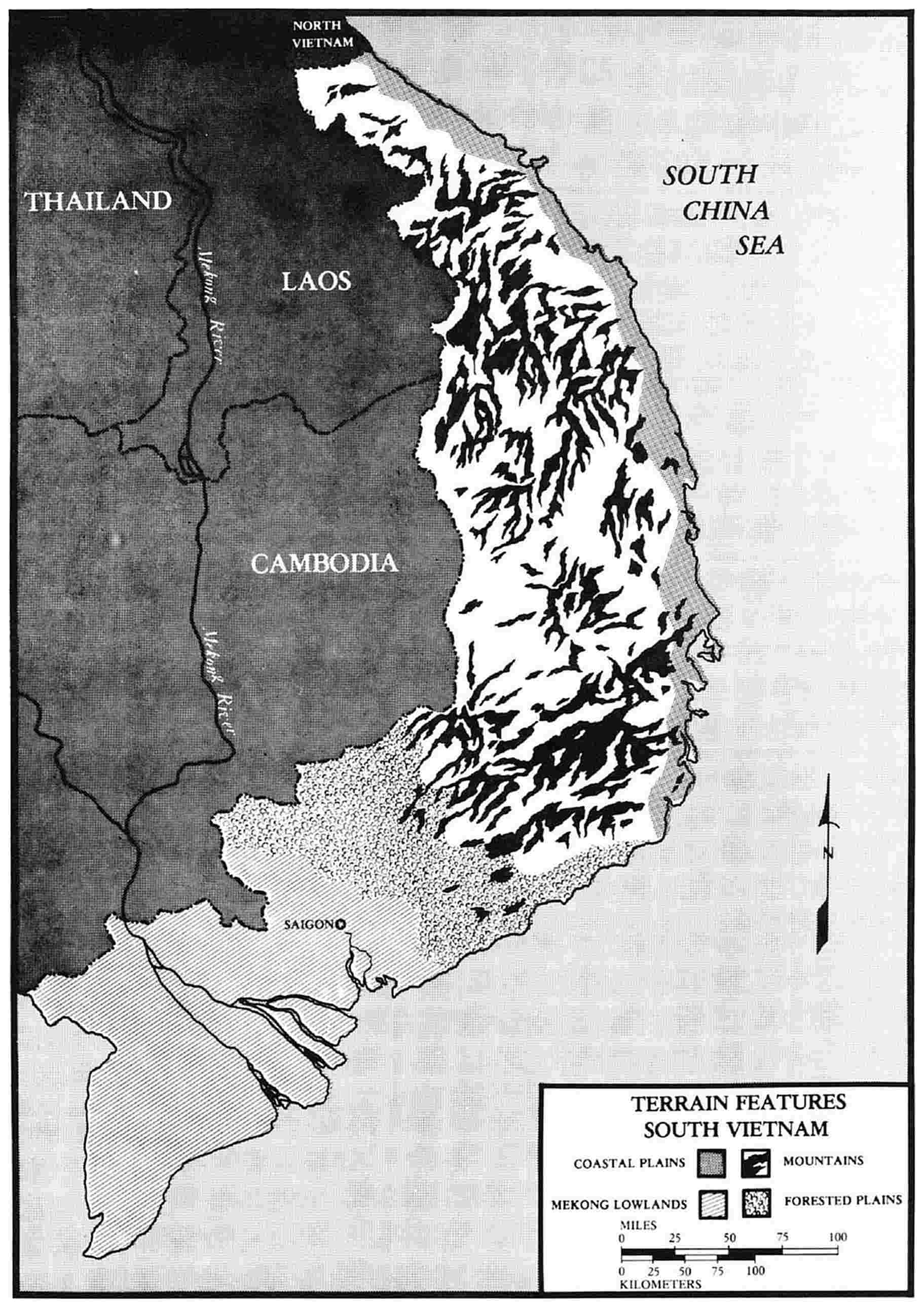

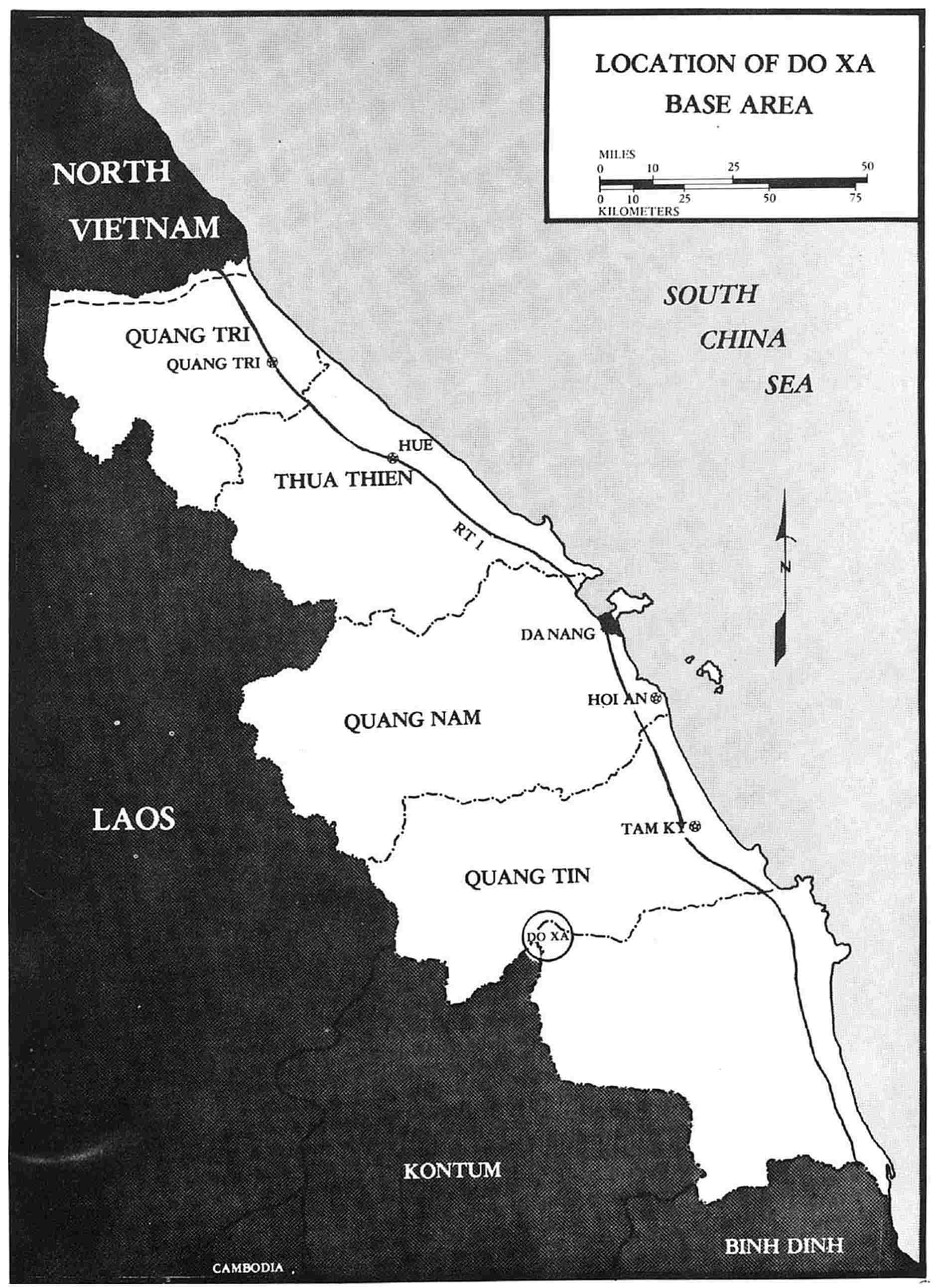

South Vietnam is divided into four relatively distinct physiographic regions—the Mekong Delta, the coastal plain, the Annamite Mountains, and the forested plain. The Mekong Delta, an extensive and fertile lowland centered on the Mekong River, covers roughly the southern quarter of the country. This region is essentially a marshy flat land well suited for rice growing and is recognized as one of Asia’s richest agricultural areas. South Vietnam’s second physiographic region, the coastal plain, is similar to the Mekong Delta in that it is predominantly flat and generally well suited for rice growing. Properly known as the coastal lowland, this region extends from the country’s northern border to the Mekong Delta. Its width is never constant, being defined on the west by the rugged Annamite Mountains—the region which dominates the northern two thirds of South Vietnam. The jungle-covered mountains, whose highest elevations measure over 8,000 feet, stand in sharp contrast to the low and flat coastal plain. The eastern slopes of the mountains normally rise from the lowlands at a distance of five or 10 miles from the sea. At several points along the coast, however, the emerald mountains crowd to the water’s edge, dividing the coastal plain into compartments and creating a seascape breathtaking in its beauty. At other locations the mountain chain recedes from the coast, allowing the lowlands to extend inland as far as 40 miles. An extensive upland plateau sprawls over the central portion of South Vietnam’s mountain region.

This important subregion, known as the Central Highlands, possesses relatively fertile soil and has great potential for agricultural development. The highest elevations in the Annamite chain are recorded south of the Central Highlands. From heights of 6,000 to 7,000 feet, the mountains dissolve southward into the forested plain, a hilly transition zone which forms a strip between the Mekong lowlands and the southernmost mountains.

South Vietnam lies entirely below the Tropic of Cancer. Its climate is best described as hot and humid. Because the country is situated within Southeast Asia’s twin tropical monsoon belt, it experiences two distinct rainy seasons. The southwest (or summer) monsoon settles over the Mekong Delta and the southern part of the country in mid-May and lasts until early October. In the northern reaches, the northeast (or winter) monsoon season begins in November and continues through most of March. Unlike the rainy season in the south, fog, wind, and noticeably lower temperatures characterize the wet season in the north. While the reversed monsoon seasons provide an abundance of water for rice growing throughout the Mekong Delta and most of the long coastal plain, rainfall is not distributed uniformly. Parts of the central coast record only about 28 inches of annual precipitation. In contrast, other areas along the northern coast receive as much as 126 inches of rain during the course of a year. Even worse, a percentage of this rainfall can be expected to occur as a result of typhoons. The tropical storms usually lash the Annamese coast between July and November. Almost always they cause extensive flooding along normally sluggish rivers which dissect the coastal plain.

The People

Slightly over 16 million people currently inhabit South Vietnam. Of these, over 13 million are ethnic Vietnamese. Primarily rice farmers and fishermen, the Vietnamese have tended to compress themselves into the country’s most productive agricultural areas—the Mekong Delta and the coastal plain. Chinese, numbering around one million, form South Vietnam’s largest ethnic minority. Concentrated for the most part in the major cities, the Chinese traditionally have played a leading role in Vietnam’s commerce. About 700,000 Montagnard tribesmen, scattered across the upland plateau and the rugged northern mountains, constitute South Vietnam’s second largest minority. Some 400,000 Khmers, closely akin to the dominant population of Cambodia, inhabit the lowlands along the Cambodian border. Roughly 35,000 Chams, remnants of a once powerful kingdom that blocked the southern migration of the Vietnamese until the late 1400s, form the country’s smallest and least influential ethnic minority. The Chams, whose ancestors once controlled most of the central and southern Annamese coast, are confined to a few small villages on the central coast near Phan Rang.

7

TERRAIN FEATURES

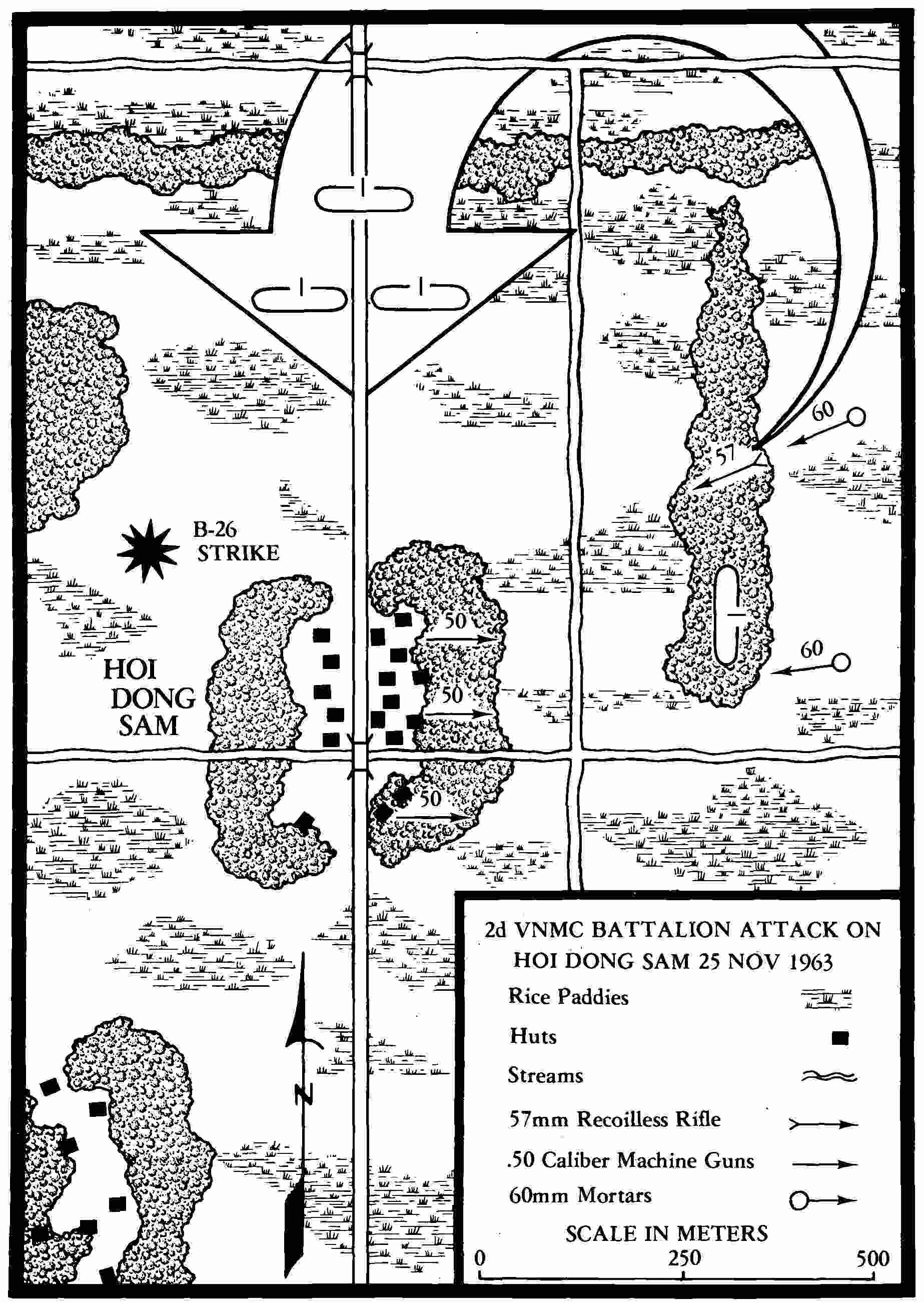

SOUTH VIETNAM

8

South Vietnamese adhere to a broad range of religions. Between 70 and 80 percent of the country’s 16 million people are classified as Buddhist. It is estimated, however, that a much smaller percentage are actually practitioners. Roman Catholics comprise roughly 10 percent of the total population. Usually found in and around the country’s urban centers, the Catholics are products of Vietnam’s contacts with Europeans. Two so-called politico-religious sects, the Cao Dai and the Hoa Hao, have attracted large segments of the rural population, particularly in the Mekong Delta.[1-A] For the most part, the scattered Montagnard tribes worship animal forms and have no organized religion, although many have been converted to Christianity.

[1-A] Founded just after World War I, the Cao Dai claims more than one and a half million faithful in South Vietnam. The religion incorporates elements of Taoism, Buddhism, Christianity, Confucianism, and large doses of spiritualism. Its clergy, headed by a “pope,” is organized in a hierarchy modelled on that of the Roman Catholic Church. The extent of its borrowing is suggested by the fact that adherents count the French author Victor Hugo as one of their saints. Politically, the Cao Dai moved sharply in the direction of nationalism during the 1940s, organized its own army, and fought sporadic actions against the French and the subsequent French-controlled government of Emperor Bao Dai until suppressed by the Diem government in 1954.

Like the Cao Dai, the Hoa Hao is peculiarly Vietnamese. In the late 1930s, a Buddhist monk named Huynh Pho So began a “protestant” movement within the worldly, easy-going Buddhist faith then prevalent. His followers, whose ranks grew rapidly, called themselves Hoa Hao after the village where Phu So began his crusade. Like the Cao Dai faithful and Catholics, they tended to live apart in their own villages and hamlets concentrated in the very south and west of Vietnam, primarily along the Cambodian border. Intensely nationalistic and xenophobic, they were under constant attack from the French, Japanese, and Viet Minh, and by the late 1940s had recruited a large militia which was subsequently disbanded. Today their overall membership stands at about one million.

Fundamentally, South Vietnamese society is rural and agrarian. Over the centuries the Vietnamese have tended to cluster in tiny hamlets strewn down the coastal plain and across the Mekong Delta. Usually composed of a handful of closely knit families whose ancestors settled the surrounding land generations earlier, the hamlet is South Vietnam’s basic community unit. Next larger is the village which resembles the American township in function in that it encompasses a number of adjacent hamlets. The Vietnamese people have naturally developed strong emotional ties with their native villages. “To the Vietnamese,” it has been said without exaggeration, “the village is his land’s heart, mind, and soul.”[1-3] Given the rural nature of the country it is understandable that the inhabitants of the villages and hamlets have retained a large degree of self-government. “The laws of the emperor,” states an ancient Vietnamese proverb, “are less than the customs of the village.”[1-4]

Overlaying this rural mosaic are two intermediate governmental echelons—the districts and the provinces, The district, the smaller of these political and geographic subdivisions, first appeared in Vietnamese history following the earliest annexation of Tonkin by the Chinese in 111 B.C. It remained in use and was extended down the Annamese coast and into Cochinchina by the successive Vietnamese dynasties which came to power in the ensuing centuries. Provinces, larger geographic subdivisions, eventually were superimposed over groups of contiguous districts, thus adding another echelon between the reigning central government and the villages. This structure remained in existence under the French after they took control of all Vietnam in the late 19th century. In order to make their administration more efficient French colonial authorities modernized the cumbersome administrative machinery and adjusted provincial boundaries. It is essentially this French-influenced structure that exists in South Vietnam today. Still, after years of use and modification, the system seems somewhat superficial as traditional self-rule of the villages tends to nullify the efforts of provinces and districts to govern rural areas. Often the central government’s influence is unable to seep lower than the district headquarters, particularly in more remote areas.

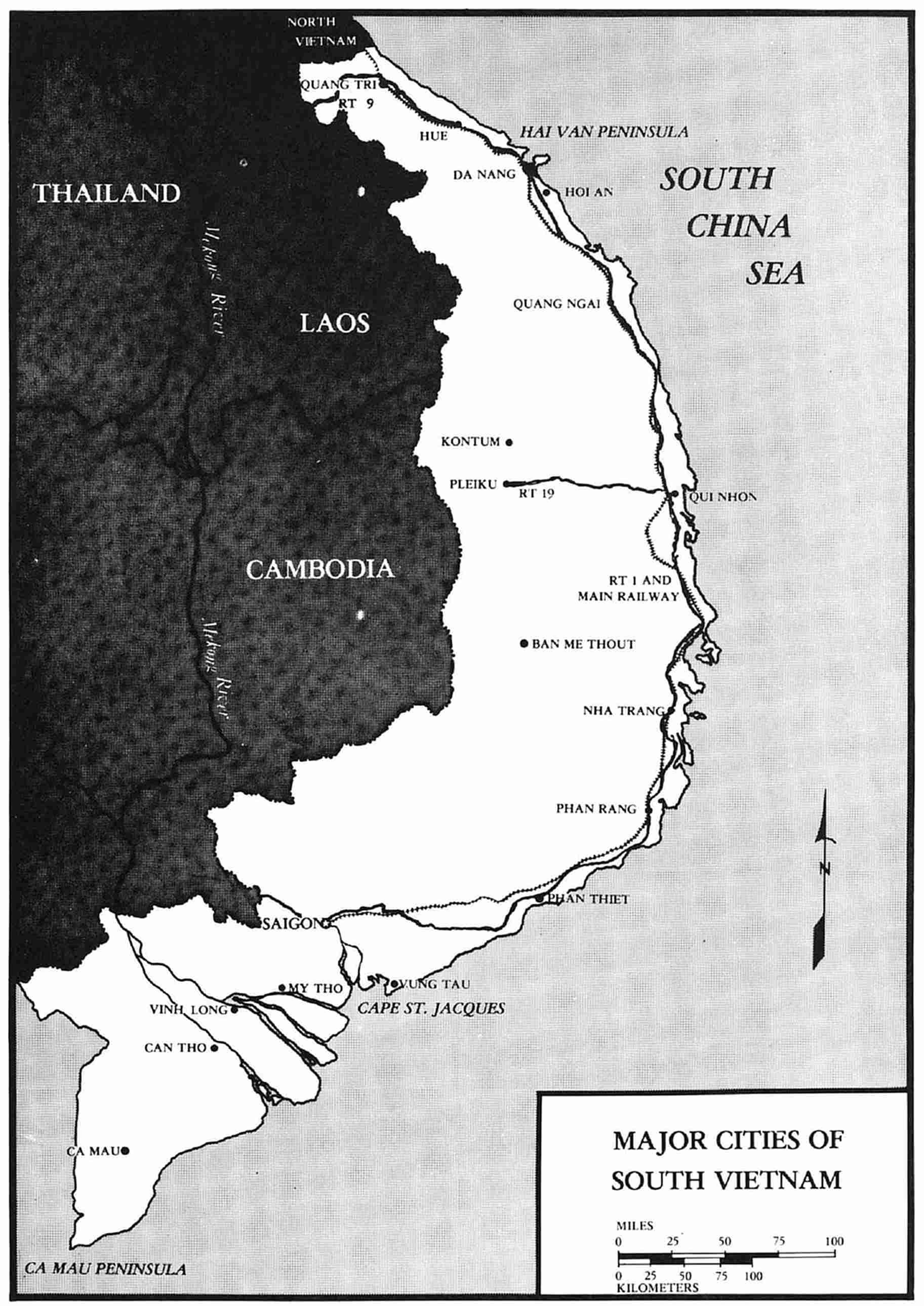

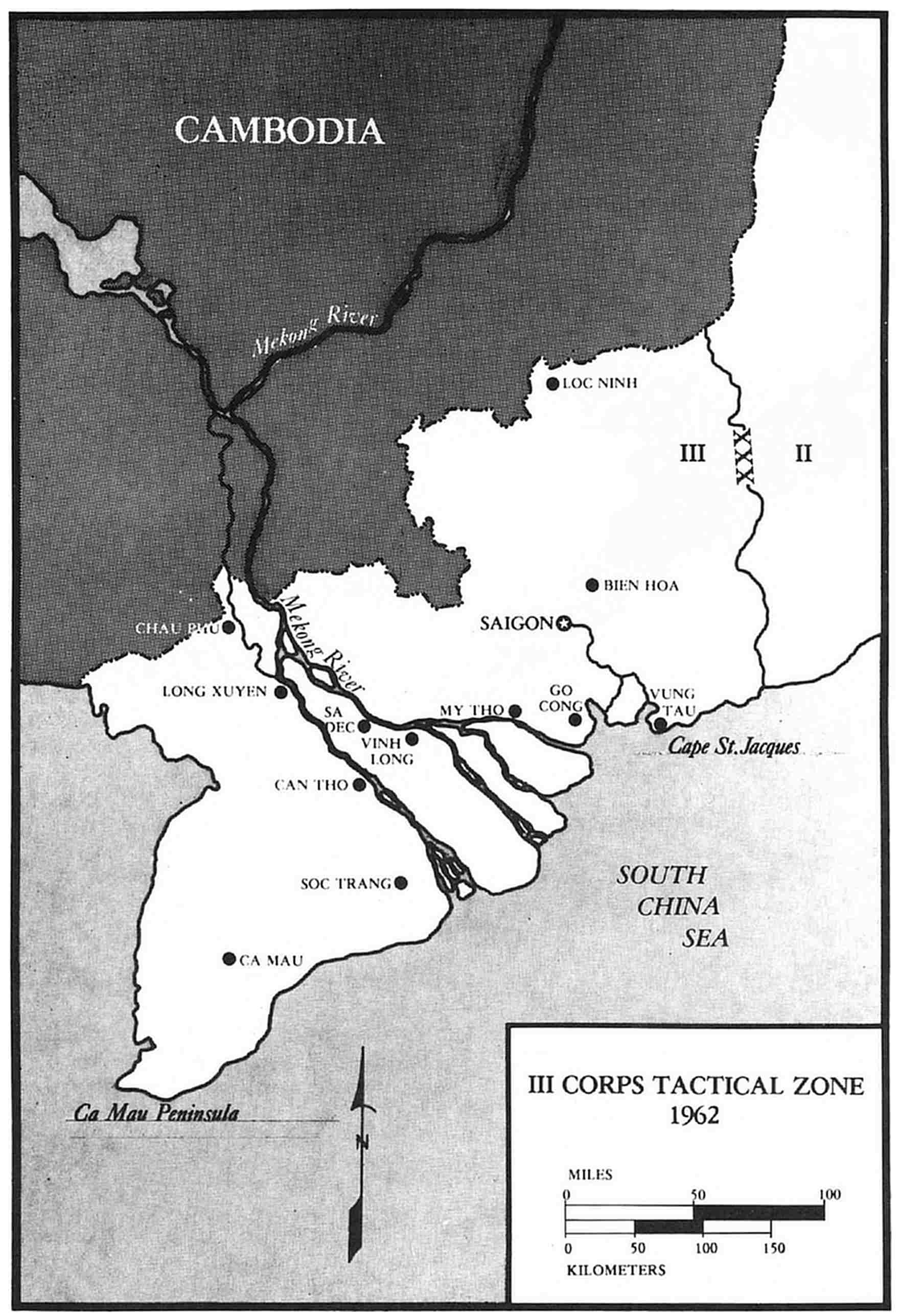

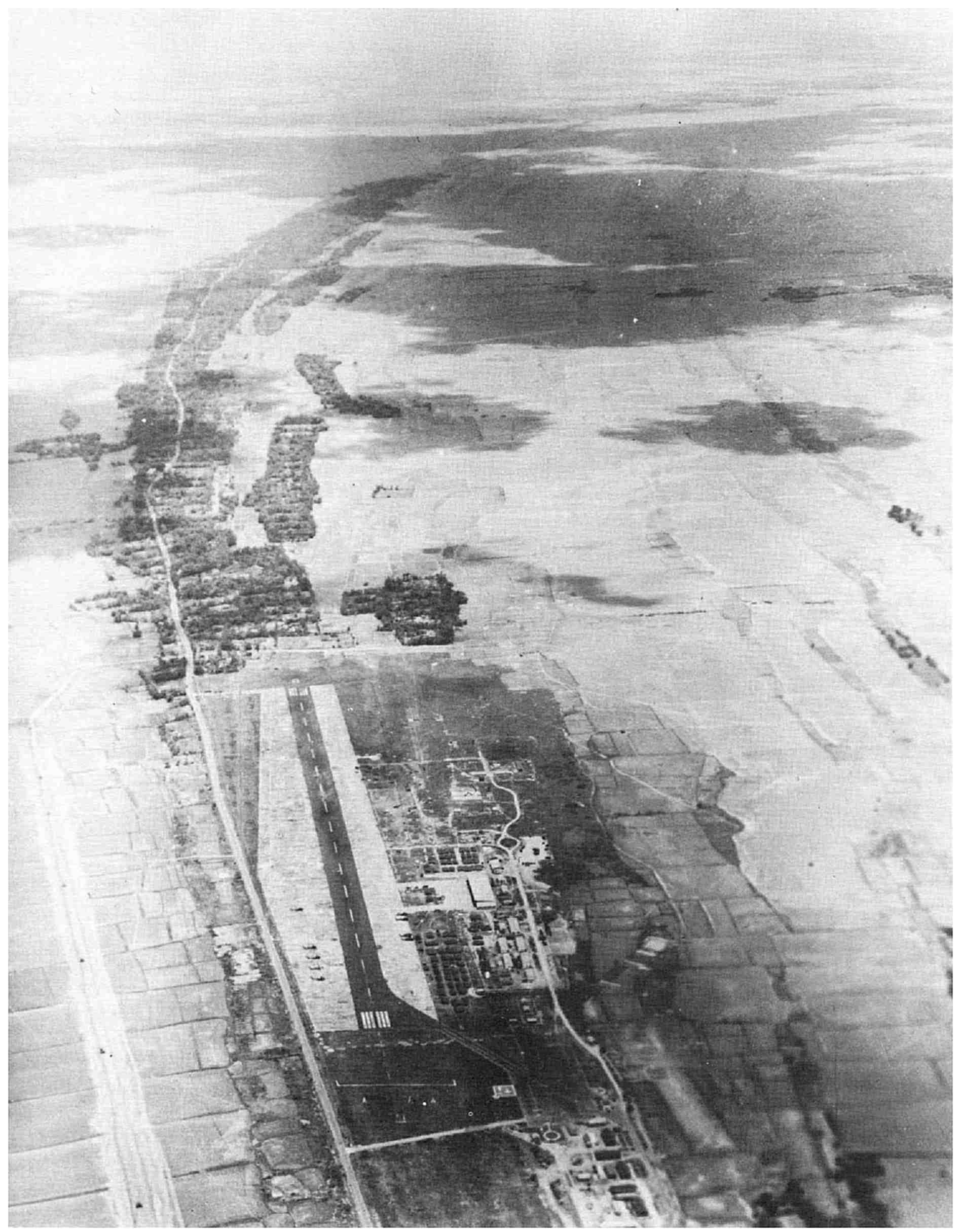

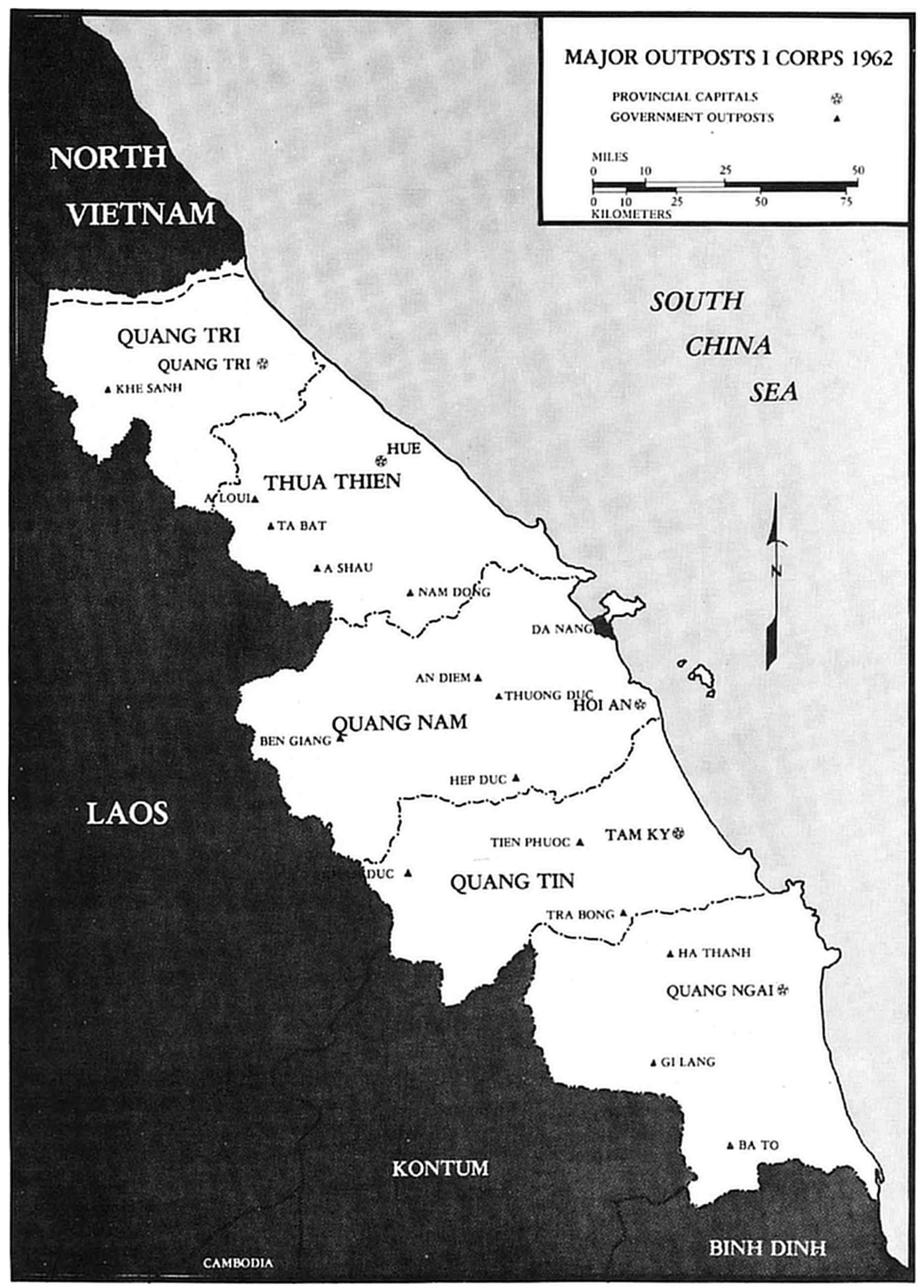

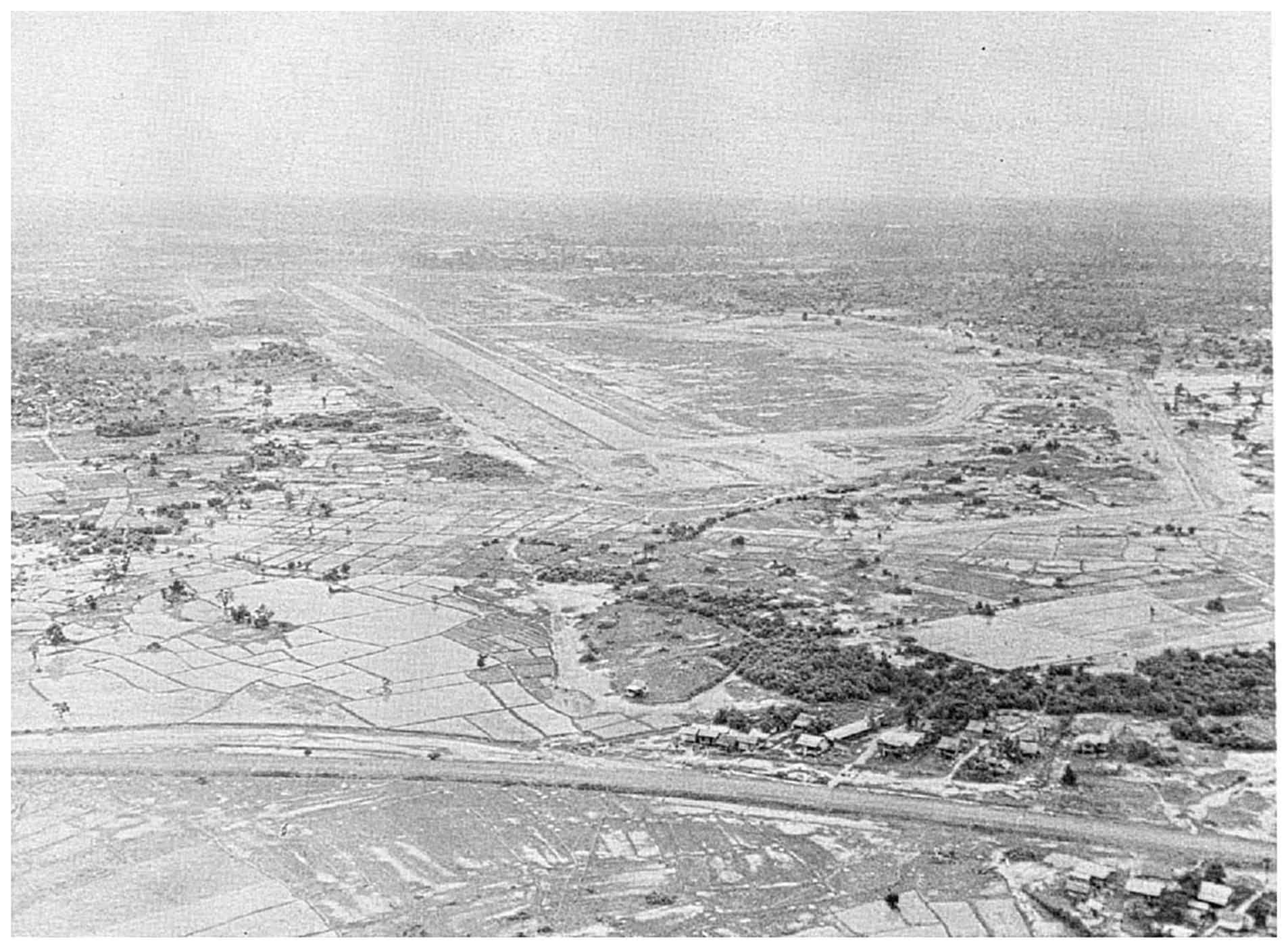

While South Vietnam is predominantly rural, it does possess several important urban centers. As might be expected, these are found primarily in the densely populated Mekong Delta and along the coastal lowland. Saigon, the nation’s capital and largest city, presently has a population estimated at 3.5 million. Located slightly north of the Mekong River complex and inland from the coast, the city dominates the country in both an economic and political sense. Saigon has excellent port facilities for ocean-going ships, although such traffic must first negotiate the tangled Saigon River which leads inland from the South China Sea. Da Nang, located on the Annamese coast 84 miles below the northern border, is the country’s second largest9 city. With a population of roughly 500,000 and a protected harbor, Da Nang constitutes the principal economic center in northern South Vietnam. The old imperial capital of Hue (population of roughly 200,000), situated about 50 miles north of Da Nang, historically has exerted a strong cultural influence over the Annamese coast.[1-B] Scores of large towns, such as Quang Tri, Hoi An, Quang Ngai, Can Tho, and Vinh Long, extend down the coast and across the Mekong Delta. Often these serve as provincial capitals. A few lesser population centers, notably Pleiku, Kontum, and Ban Me Thuot, are situated in the Central Highlands.

[1-B] The population of most of South Vietnam’s cities and towns has been swollen by the influx of refugees which occurred as the Vietnam War intensified in the middle 1960s. In 1965, for example, refugee population estimates for the three major cities were as follows: Saigon—1.5 million; Da Nang—144,000; Hue—105,000.

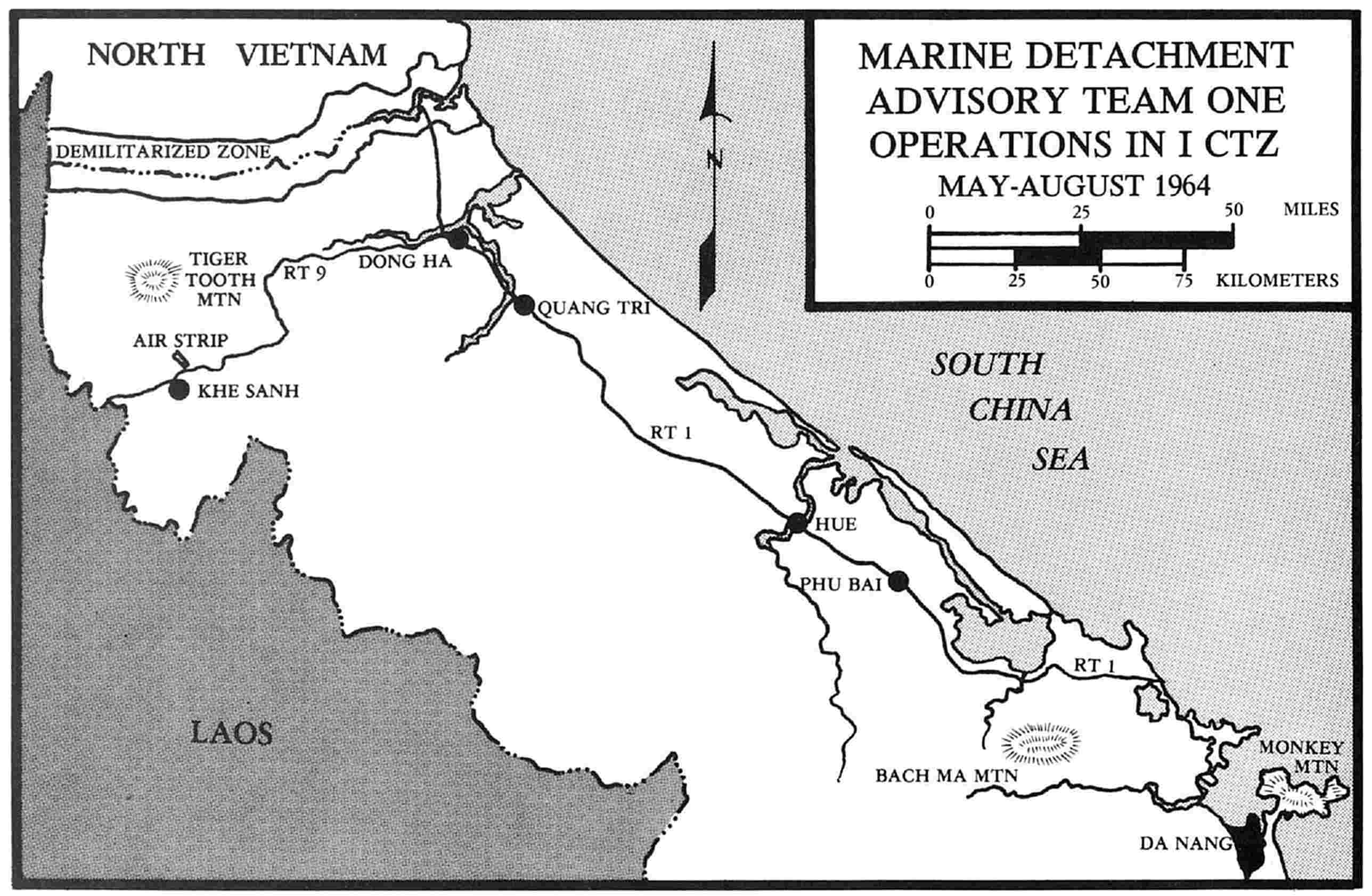

Most of South Vietnam’s major towns and cities are connected by one highway—Route 1. Constructed by the French during the early 20th century, Route 1 originally extended from Hanoi, the principal city of Tonkin in northern Vietnam, down the coast and inland to Saigon. While Route 1 and a French-built railroad which parallels it helped unify South Vietnam’s most densely populated areas, the country’s road network is otherwise underdeveloped. A few tortuous roads do twist westward from Route 1 into the mountains to reach the remote towns there. Of these the most noteworthy are Route 19, built to serve Pleiku in the Central Highlands, and Route 9, which extends westward into Laos from Dong Ha, South Vietnam’s northernmost town. A number of roads radiate outward from Saigon to the population centers of the Mekong Delta. For the most part, however, the Vietnamese people traditionally have depended on trail networks, inland waterways, and the sea to satisfy their transportation needs. The location of the bulk of the population in the watery Mekong Delta and along the seacoast has encouraged their reliance on waterborne transportation.

Vietnam’s Recent History

Prior to July 1954 the expanse of mainland Southeast Asia now occupied by South Vietnam, North Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia belonged to France. Together these possessions constituted French-Indochina over which the French had exercised political control in one form or another, with one exception, since the last quarter of the 19th century. The only interruption occurred following the capitulation of France in June 1940. Exploiting the disrupted power balance in Europe, and attracted by the natural resources and strategic value of the area, Japan moved into northern French-Indochina less than four months after France had fallen. In 1941 the Vichy French government agreed to Japanese occupation of southern French-Indochina. Soon Japanese forces controlled every airfield and major port in Indochina. Under this arrangement the Japanese permitted French colonial authorities to maintain their administrative responsibilities. But as the tide of war began to turn against the Japanese, the French became increasingly defiant. The Japanese terminated this relationship on 9 March 1945 when, without warning, they arrested colonial officials throughout Indochina and brutally seized control of all governmental functions.

Six months after the dissolution of the French colonial apparatus in Indochina, World War II ended. The grip which Japan had held on most of Southeast Asia for nearly half a decade was broken on 2 September 1945 when her foreign minister signed the instrument of unconditional surrender on board the battleship USS Missouri. Shortly thereafter, in accordance with a previously reached Allied agreement, Chinese Nationalist forces moved into Tonkin and northern Annam to accept the surrender of Japanese forces. South of the 16th parallel, British units arrived from India to disarm the defeated Japanese. A detachment of 150 men from a small French Expeditionary Corps arrived by air in Saigon on the 12th to assist the British, who had included them only as a courtesy since France was not among the powers slated to receive the surrender of the Japanese in Indochina.

But the end of World War II and the arrival of Allied forces did not end the struggle for control of French-Indochina. Instead, it signalled the beginning of a new conflict in which the contestants were, in many respects, more formidable. One of these, the French, moved quickly to restore their former presence in Cochinchina and Annam. Reinforced with additional units, they occupied most major towns between the Mekong Delta and the11 16th parallel by the end of 1945. Two months later French negotiators secured an agreement with the Chinese Nationalists whereby French units would replace the Chinese occupation forces north of the 16th parallel.

MAJOR CITIES OF

SOUTH VIETNAM

Wartime developments in French-Indochina, however, had brought about profound political changes which eventually would doom the French effort to re-establish political and economic influence in the region. During World War II, Ho Chi Minh, an avowed Communist, had transformed a relatively feeble political party into a sizable guerrilla organization. Known as the Viet Minh, the Communist guerrillas had been organized, trained, and led by Vo Nguyen Giap, a former history teacher from Annam. During the latter stages of the war, the United States had supplied the Viet Minh with limited quantities of military supplies. In return, Ho’s guerrillas had assisted downed American pilots and occasionally had clashed with small Japanese units. But the Viet Minh had wasted few men on costly major actions against the Japanese. Conserving their forces, Ho and Giap had concentrated on organization and had managed to extend their strength into the densely populated Red River Delta and along the Annamese coast. In Cochinchina, where their numbers were considerably smaller, the Communists had limited their activities almost entirely to organization and recruitment. Thus, by the end of the war Ho’s organization was able to emerge as a definite military-political force in northern French-Indochina.

Following the Japanese surrender and before the arrival of the Chinese Nationalist occupation forces, the Viet Minh seized control of Hanoi, the capital of Tonkin, and proclaimed the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. At Ho’s direction the Viet Minh promptly shifted from their anti-Japanese posture and prepared to contest the French return.

Confronted with this situation in northern Indochina, the French were forced to bargain with the Communists. A preliminary agreement was reached on 6 March 1946 whereby the French agreed to recognize the newly founded but relatively weak Democratic Republic of Vietnam as a “free state within the French Union.” In return, Ho’s government declared itself “ready to welcome in friendly fashion the French Army, when in conformance with international agreement, it would relieve the Chinese forces” which had accepted the Japanese surrender in Tonkin.[1-5] Shortly after the conclusion of this agreement, French forces began reoccupying Tonkin and northern Annam. Within six months they controlled every major strategic position from the Chinese border to the Ca Mau Peninsula, Cochinchina’s southern tip.

The uneasy peace was broken in December 1946 after Viet Minh and French negotiators failed to reach a final agreement on actual political control of Tonkin and Annam. When open warfare erupted, Ho withdrew the bulk of his military forces into mountainous sanctuaries along the Chinese border, but left small groups of guerrillas scattered throughout the heavily populated Red River Delta. Reinforced with contingents from Europe and Africa, the French Expeditionary Corps initially managed to hold its own and, in some cases, even extend its control. But, drawing strength from its natural appeal to Vietnamese nationalism, the Communist movement began gaining momentum in the late 1940s. Gradually the war intensified and spread into central Annam and Cochinchina.

In January 1950, the French moved to undercut the Viet Minh’s appeal to non-Communist nationalists by granting nominal independence to its Indochina possessions. Under the terms of a formal treaty, all of Vietnam (Tonkin, Annam, and Cochinchina) was brought together under a Saigon-based government headed by Emperor Bao Dai. Laos and Cambodia likewise formed their own governments, whereupon all three countries became known as the Associated States of Indochina.

This new arrangement, however, had little effect on the ongoing war with the Viet Minh. In accordance with the treaties, the Associated States became members of the French Union and agreed to prosecute the war under French direction. Moreover, French political dominance in the region continued, virtually undiluted by the existence of the Associated States.

In related developments, Mao Tse-tung’s Chinese Communist armies seized control of mainland China in 1949 and Communist North Korean forces invaded the pro-Western Republic of Korea in 1950. These events added new meaning to the French struggle in Indochina as American policy makers came to view the war on the Southeast Asian mainland within the context of a larger12 design to bring Asia entirely under Communist domination. Following the invasion of South Korea, President Truman immediately announced his intention to step up U.S. military aid to the French in Indochina. Congress responded quickly by adding four billion dollars to existing military assistance funds. Of this, $303 million was earmarked for Korea, the Philippines, and “the general area of China.”[1-6][1-C] Thus, the Truman Administration, now confronted by the possibility that Communism might engulf all of mainland Asia, extended its containment policy to Indochina.

[1-C] The following year would see a half billion U.S. dollars allocated to support French operations in Indochina. By 1954 that figure would climb to an even one billion dollars.

Even with rapidly increasing amounts of U.S. material assistance, the French proved unable to wrest the initiative from Giap’s growing armies. Although national armies drawn from Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam were now fighting alongside the French, the Expeditionary Corps was over-extended. Moreover, the French cause was extremely vulnerable to Communist propaganda. On the home front, public support for the so-called sale guerre (dirty war) eroded steadily during the early 1950s as the Expeditionary Corps’ failures and casualties mounted. Finally, on 7 May 1954, the besieged 13,000-man French garrison at Dien Bien Phu surrendered to the Viet Minh, thus shattering what remained of French determination to prosecute the war in Indochina. In Geneva, where Communist and Free World diplomats had gathered to consider a formal peace in Korea along with the Indochina problem, French and Viet Minh representatives signed a cease-fire agreement on 20 July which ended the eight-year conflict.

The bilateral cease-fire agreement substantially altered the map of the Indochinese Peninsula. France agreed to relinquish political control throughout the area. Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam all gained full independence. The most controversial provision of the 20 July agreement divided Vietnam at the Ben Hai River and superimposed a demilitarized zone over the partition line. This division, intended to facilitate the disengagement of the opposing forces, was to be temporary pending a reunification election scheduled for mid-1956. In accordance with the agreement, France immediately turned over political control of the northern zone (Tonkin and the northern half of Annam) to the Communist Viet Minh. Ho promptly re-established the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) with its capital in Hanoi.

Other provisions of the Geneva Agreement called for the opposing armies to regroup in their respective zones within 300 days. Following their regroupment, the French military forces were to be completely withdrawn from the North within 300 days and from the South by mid-1956. Civilians living both north and south of the partition line were to be allowed to emigrate to the opposite zone in accordance with their political convictions. It was anticipated that thousands of Catholics living in Tonkin would seek refuge in the non-Communist South. Other articles of the agreement dealt with the creation and responsibilities of an International Control Commission (ICC) to supervise the cease-fire. Canadian, Indian, and Polish delegations were to comprise this commission.

On 21 July, the day following the bilateral agreement, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, the Peoples Republic of China, Cambodia, and Laos joined France and the Viet Minh in endorsing a “Final Declaration” which sanctioned the previously reached cease-fire agreement. The United States refused to endorse this declaration, but issued a statement to the effect that it would not use force to disturb the cease-fire.

Post-Geneva South Vietnam

The execution of the Geneva Agreement thrust that area of Vietnam south of the partition line into a period of profound confusion and instability. Even worse, the colonial period had done little to prepare the Cochinchinese and Annamese for the tremendous problems at hand. No real apparatus for central government existed. Likewise, the long colonial period left the area with few experienced political leaders capable of establishing and managing the required governmental machinery. Political control passed nominally to the French-sponsored emperor, Bao Dai, who was living in France at the time. For all practical purposes, leadership in the South devolved upon Bao Dai’s recently appointed pro-Western premier, Ngo Dinh Diem. The product of a prosperous and well-educated Catholic family from Hue, Diem had served the French briefly as a province chief13 prior to World War II. Always a strong nationalist but staunchly anti-Communist, he had been unable to reconcile his anti-French attitudes with the Viet Minh movement during the Indochina War. As a result Diem had left his homeland in the early 1950s to live at a Catholic seminary in the United States. There he remained until his appointment as premier in mid-June of 1954.

The months immediately following the Geneva agreement found Ngo Dinh Diem struggling to create the necessary governmental machinery in Saigon, the capital of the southern zone. At best, however, his hold on the feeble institutions was tenuous. A serious confrontation was developing between the premier and the absent Bao Dai, still residing in France. Further complicating the political scene was the presence of Hoa Hao and Cao Dai armies in the provinces surrounding the capital, and the existence in Saigon of an underworld organization named the Binh Xuyen.[1-D] As 1955 opened the leaders of these three politically oriented factions were pressing demands for concessions from the new central government. Among these were permission to maintain their private armies, and the authority to exercise political control over large, heavily populated areas.

[1-D] The Binh Xuyen originally operated from the swamps south of the Chinese-dominated Cholon district of Saigon. Controlling the vice and crime of the city, by 1954 they had gained control of the police under circumstances that reeked of bribery. A year later the organization was brutally crushed by Ngo Dinh Diem.

The outcome of the embryonic power struggle in Saigon hinged largely on control of the Vietnamese National Army (VNA). Although not considered an efficient military organization by even the most liberal estimates, the 210,000-man National Army was the principal source of organized power available to the quarreling leaders of southern Vietnam. Originally created by the French in 1950 to supplement their Expeditionary Corps, the VNA had since suffered from structural deficiencies. It actually had no organizational echelon between the French-controlled General Staff and the 160 separate battalions. Tied to no regiments or divisions, the Vietnamese battalions naturally were dependent on the French Expeditionary Corps for operational instructions and logistical support.[1-E]

[1-E] Selected VNA battalions were sometimes task organized into groupes mobiles (mobile groups) by the French for specific offensive operations. But these groups, which were roughly equivalent to a regimental combat team, were never composed entirely of VNA battalions under a Vietnamese command group.

The danger that the pro-Western zone might become the victim of a sudden Communist attack from the north, as had been the case on the Korean Peninsula, injected another element of uncertainty into the overall situation in southern Vietnam. The conditions which settled over the area in the immediate aftermath of the Geneva settlement suggested this possibility since they were alarmingly similar to the conditions which had prevailed in Korea prior to the North Korean invasion of 1950. Like Korea, Vietnam was divided both geographically and ideologically: the North clearly within the orbit of the Soviet Union and Communist China, and the South under the influence of the Western powers. As in Korea in 1950, there also existed a very real armed threat to the weaker pro-Western southern state. Immediately after the Geneva cease-fire, the Viet Minh army regrouped north of the 17th parallel and was redesignated the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN). American intelligence reported that the PAVN, which numbered roughly 240,000 disciplined veterans, was being reorganized and re-equipped with Soviet and Chinese weapons in violation of the Geneva Agreement. At the same time Western intelligence sources estimated that the Viet Minh had intentionally left between 5,000 and 10,000 men south of the partition line following their withdrawal. Also done in violation of the cease-fire agreement, this meant that Communist guerrillas could be expected to surface throughout the South in the event of an outright invasion.

A related condition heightened fears that a Korea-type invasion might occur in Vietnam. In South Korea a military vacuum had been allowed to form in 1949 when American units withdrew from the area. Apparently that vacuum, coupled with a statement by the American Secretary of14 State to the effect that the U.S. defensive perimeter in the Pacific did not include South Korea, had encouraged Communist aggression. Now, with the scheduled evacuation of French armies from Indochina by mid-1956, there emerged the distinct possibility that such a military vacuum would recur, this time in southern Vietnam. “Vietnam,” warned one American scholar familiar with the region, “may very soon become either a dam against aggression from the north or a bridge serving the communist block to transform the countries of the Indochinese peninsula into satellites of China.”[1-7]

The American Response

It was in the face of this uncertain situation on the Southeast Asian mainland that the Eisenhower administration moved to discourage renewed Communist military activity. First, the United States sought to create a regional international organization to promote collective military action under the threat of aggression. This was obtained on 8 September 1954 when eight nations—the United States, Great Britain, France, New Zealand, Australia, the Philippines, Pakistan, and Thailand—signed the Manila Pact. The treaty area encompassed by the pact included Southeast Asia, the Southwest Pacific below 21°31′ north latitude, and Pakistan. Two weeks later the pact was transformed into the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO). In a separate protocol, the member nations agreed that Cambodia, Laos, and the “Free Territory under the jurisdiction of the State of Vietnam” all resided within their defense sphere.[1-8]

Next, after several months of hesitation, the United States settled on a policy of comprehensive assistance to South Vietnam, as the area south of the 1954 partition line was already being called. As conceived, the immediate objective of the new American policy was to bring political stability to South Vietnam. The longer range goal was the creation of a bulwark to discourage renewed Communist expansion down the Indochinese Peninsula. In this scheme, military assistance was to play a key role. “One of the most efficient means of enabling the Vietnamese Government to become strong,” explained Eisenhower’s Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, “is to assist it in reorganizing the National Army and in training that Army.”[1-9] In short, the State Department’s position was that a stronger, more responsive Vietnamese National Army would help Premier Diem consolidate his political power. Later that same force would serve as a shield behind which South Vietnam would attempt to recover from the ravages of the French-Indochina War and the after effects of the Geneva Agreement.

So by early 1955 a combination of circumstances—South Vietnam’s position adjacent to a Communist state, the unsavory memories of the Korean invasion, and the impending withdrawal of the French Expeditionary Corps—had influenced the United States to adopt a policy of military support for Premier Diem’s struggling government.

15

CHAPTER 2

The Formative Years

Military Assistance Advisory Group, Vietnam—Origins of U.S. Marine

Assistance—Political Stabilization and Its Effects—Reorganization and

Progress—Summing Up Developments

Military Assistance Advisory Group, Vietnam

When the Geneva cease-fire went into effect in the late summer of 1954, the machinery for implementing the military phase of the American assistance program for South Vietnam already existed. President Truman had ordered the establishment of a U.S. Military Assistance Advisory Group (USMAAG or MAAG) in French Indochina in mid-1950 as one of several reactions to the North Korean invasion of the Republic of Korea. Established to provide materiel support to the French Expeditionary Corps, the MAAG constituted little more than a logistical funnel through which U.S. military aid had been poured.

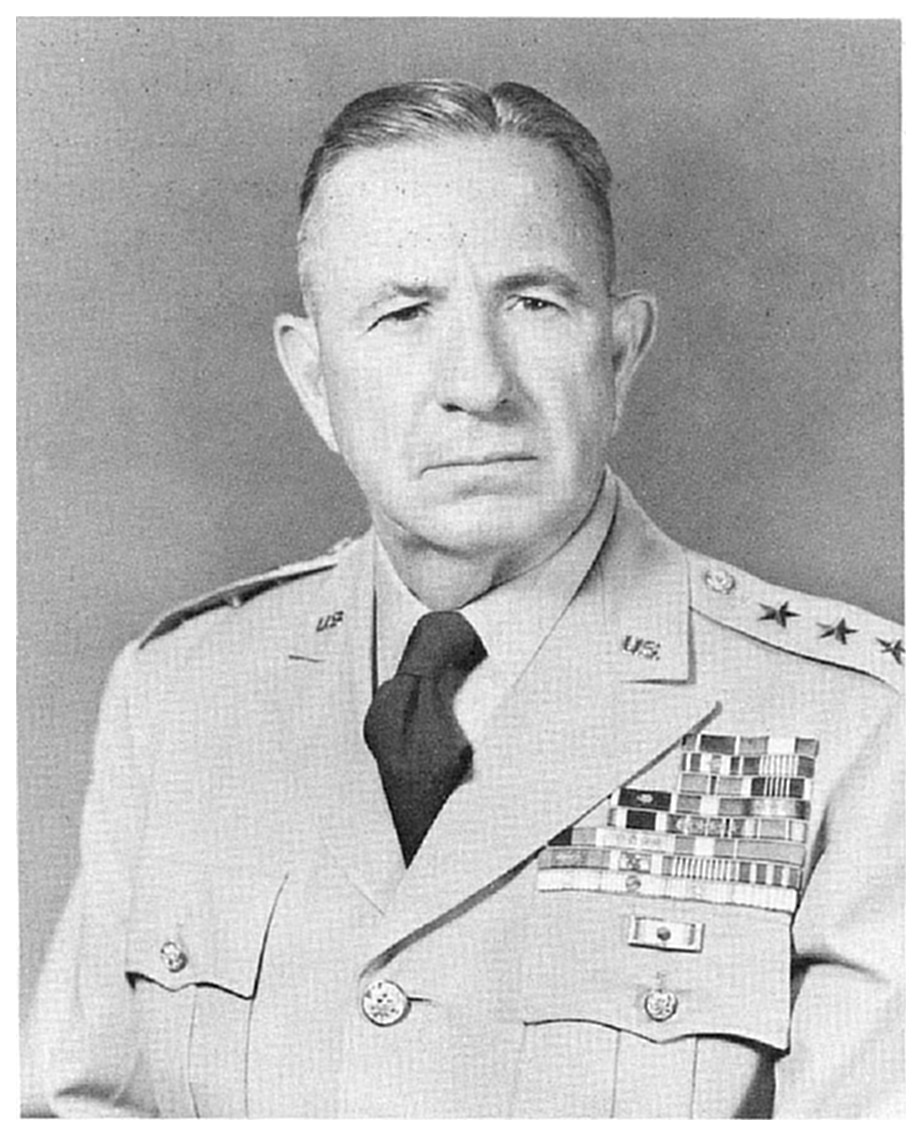

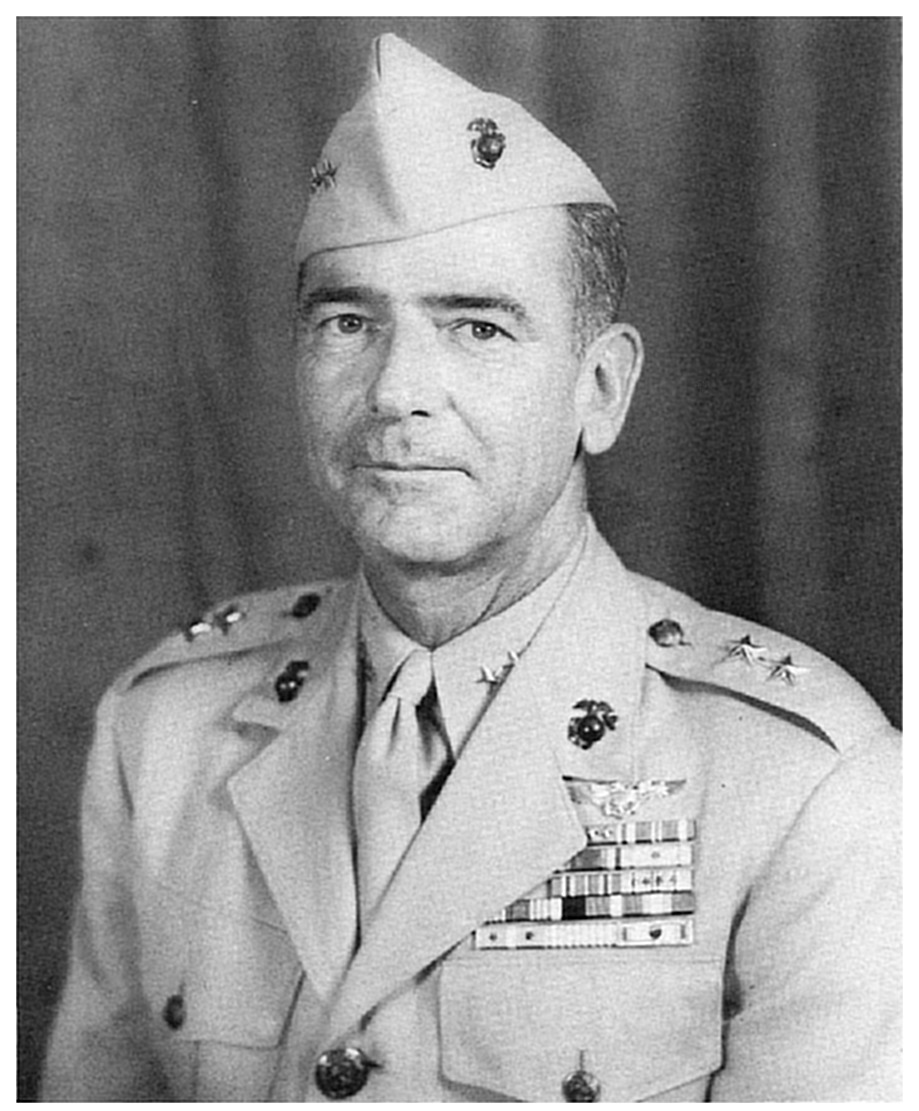

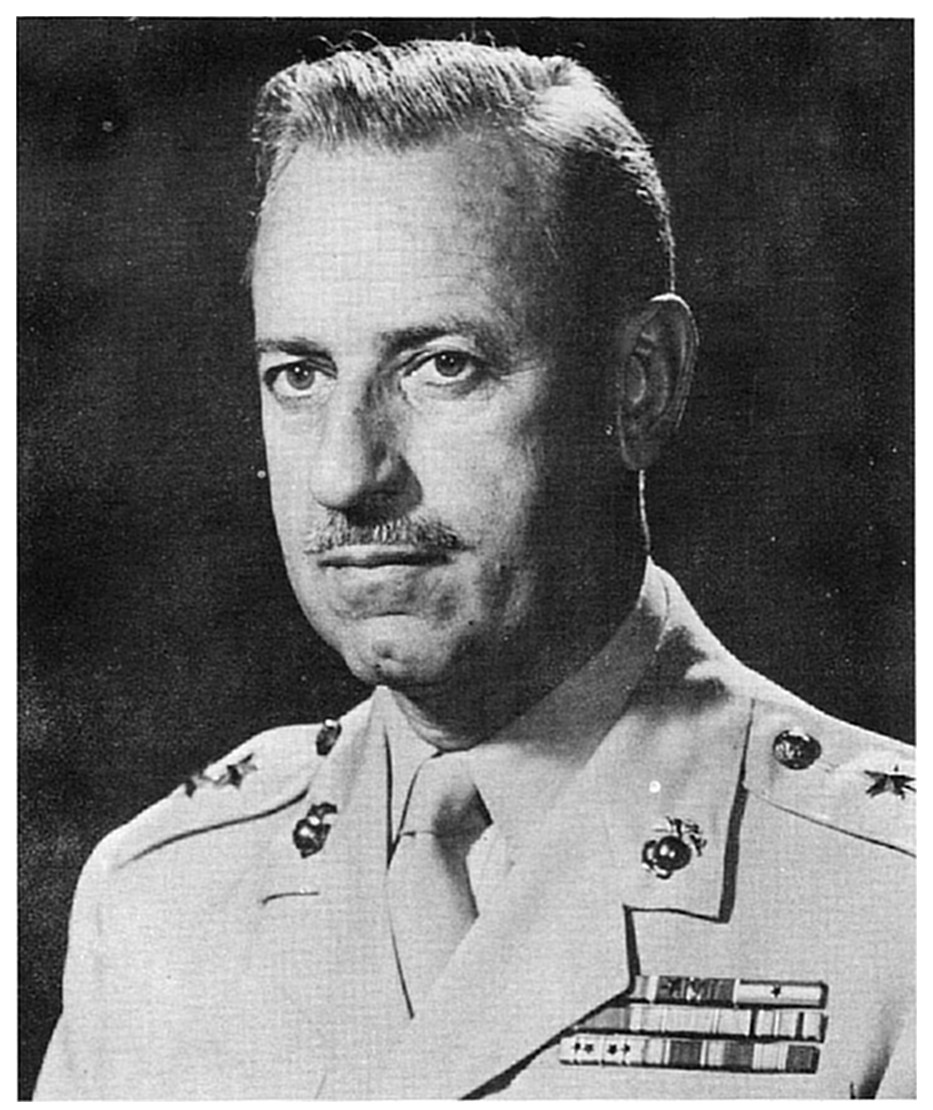

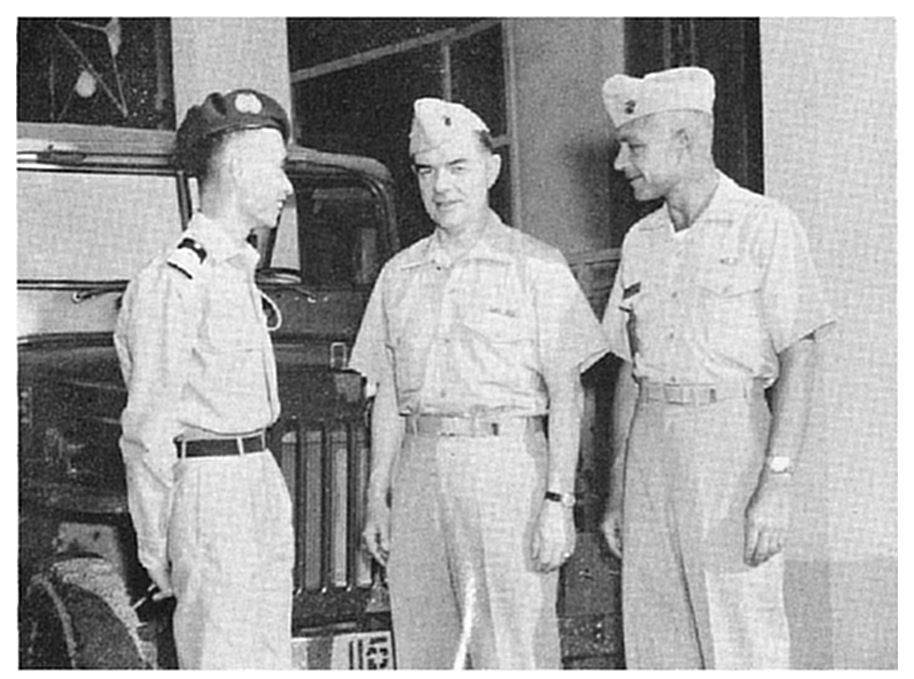

Lieutenant General John M. (“Iron Mike”) O’Daniel, U.S. Army, had been assigned to command the MAAG in the spring of 1954. O’Daniel’s selection for the Saigon post anticipated a more active U.S. role in training of the Vietnamese National Army. He had been chosen for the assignment largely on the basis of his successful role in creating and supervising the training programs which had transformed the South Korean Army into an effective fighting force during the Korean War. Now, in the aftermath of the Geneva settlement, he and his 342-man group began preparing for the immense task of rebuilding South Vietnam’s armed forces.

The entire American project to assist the South Vietnamese in the construction of a viable state was delayed during the fall of 1954 while the necessary diplomatic agreements were negotiated among American, French, and South Vietnamese officials. President Eisenhower dispatched General J. Lawton Collins, U.S. Army (Retired), to Saigon in November to complete the details of the triangular arrangements. Collins carried with him the broad powers which would be required to expedite the negotiations.

By mid-January 1955, the president’s special envoy had paved the way for the transfer of responsibility for training, equipping, and advising the Vietnamese National Army from the French to the USMAAG. He and General Paul Ely, the officer appointed by the Paris government to oversee the French withdrawal from Indochina, had initialed a “Minute of Understanding.” In accordance with this document, the United States agreed to provide financial assistance to the French military in Vietnam in exchange for two important concessions. First, the French pledged to conduct a gradual military withdrawal from South Vietnam in order to prevent the development of a military vacuum which might precipitate a North Vietnamese invasion. Secondly, they accepted an American plan to assist in a transition stage during which the responsibility for rebuilding the Vietnamese military could be transferred to the MAAG in an orderly fashion. General Collins, in addition to engineering the understanding with General Ely, had advised Premier Diem to reduce his 210,000-man military and naval forces to a level of 100,000, a figure which the U.S. State Department felt the United States could realistically support and train.

The American plan to begin assisting South Vietnam encountered further delay even after the Ely-Collins understanding had been reached. Ely’s government, arguing that the United States had agreed to provide only one-third of the amount France had requested to finance its Indochina forces, refused to ratify the agreement. The deadlock was finally resolved on 11 February 1955 when French16 officials accepted the terms of the Ely-Collins arrangement in a revised form.

A combined Franco-American training command, designated the Training Relations Instruction Mission (TRIM), became operational in Saigon the day following the French ratification of the Ely-Collins understanding.[2-A] Headed by Lieutenant General O’Daniel but under the “overall authority” of General Ely, TRIM was structured to prevent domination by either French or Americans. The training mission was composed of four divisions, Army, Navy, Air Force, and National Security, each of which was headed alternately by either an American or a French officer. The chief of each division had as his deputy an officer of the opposite nationality. U.S. officers, however, headed the divisions considered by MAAG officials as the most important—Army and National Security. Operating through TRIM and assisted by the French military, the USMAAG was tasked with implementing the U.S. Military Assistance Program in a manner that would help shape the Vietnamese national forces into a cohesive defense establishment prior to the withdrawal of French forces.

[2-A] The combined training mission originally was designated the Allied Training Operations Mission. This designation was changed prior to the time the mission became operational.

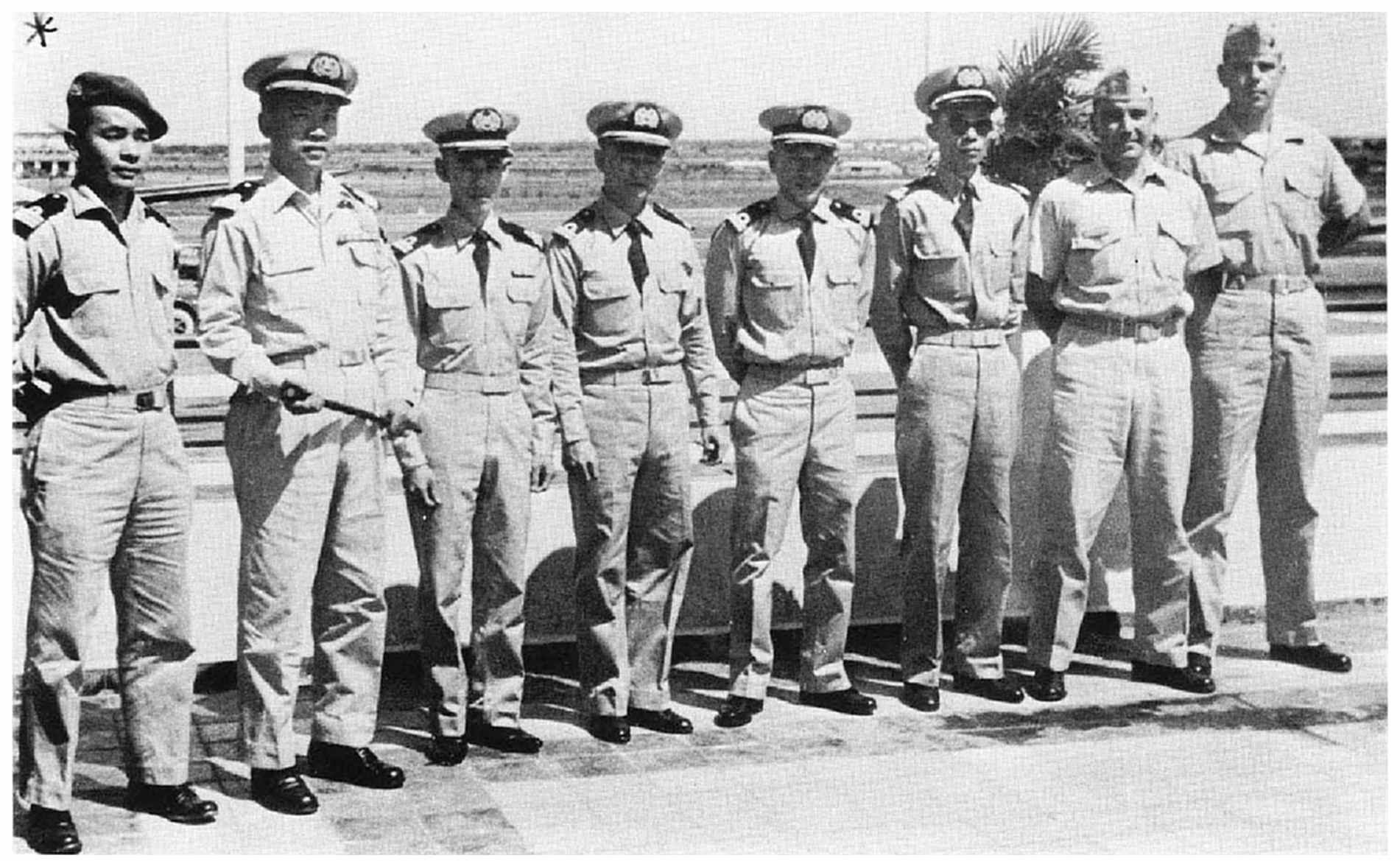

Origins of U.S. Marine Assistance

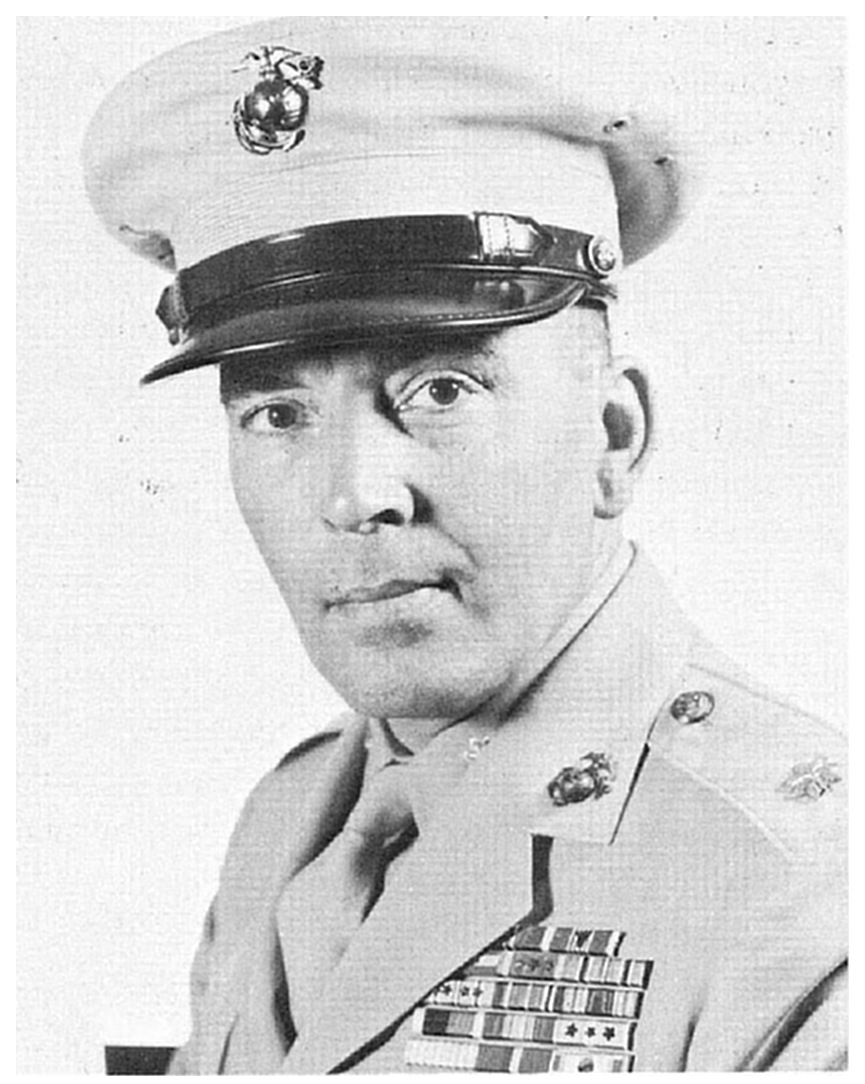

Only one U.S. Marine was serving with the USMAAG in Saigon when TRIM became operational—Lieutenant Colonel Victor J. Croizat.[2-B] Croizat’s assignment to the U.S. advisory group had resulted when General Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr., Commandant of the Marine Corps, nominated him to fill a newly created billet as liaison officer between the MAAG and the French High Command during the latter stages of the Indochina War. Largely because of his French language fluency and his former association with many French officers while attending their war college in 1949, Croizat was chosen for the assignment.

[2-B] Other Marines, however, were present in Saigon at the time. They were those assigned to the American Embassy. One officer was serving as Assistant Naval Attache/Assistant Naval Attache for Air, and 12 other Marines were serving as security guards.

Lieutenant Colonel Croizat, however, did not arrive in Vietnam until 2 August 1954. By then the cease-fire agreement had been signed at Geneva and the need for a liaison officer with the French High Command no longer existed. General O’Daniel, therefore, assigned the newly arrived Marine officer to serve on the General Commission for Refugees which had been created by the South Vietnamese Government immediately after the cease-fire. In this capacity Croizat became directly involved in the construction of refugee reception centers and the selection and development of resettlement areas in the South. When U.S. naval forces began assisting in the evacuation of North Vietnam, Lieutenant Colonel Croizat was sent to Haiphong, the principal seaport of Tonkin. There he headed the MAAG detachment and was responsible for coordinating U.S. operations in the area with those of the French and Vietnamese. When the so-called “Passage to Freedom” concluded in May 1955, 807,000 people, 469,000 tons of equipment and supplies, and 23,000 vehicles had been evacuated from Communist North Vietnam.[2-C] It was not until February 1955 that the Marine returned to Saigon.

[2-C] The French moved 497,000 people, 400,000 tons of equipment and supplies, and 15,000 vehicles. The U.S. Navy moved the balance.

During Lieutenant Colonel Croizat’s absence, Premier Diem had acted on a long-standing proposal to create a small Vietnamese Marine Corps. The issue of a separate Marine force composed of Vietnamese national troops had surfaced frequently since the birth of the Vietnamese Navy in the early 1950s. Although the proposal had been heartily endorsed by a number of senior French Navy officers, the downward spiral of the French war effort had intervened to prevent the subject from being advanced beyond a conceptual stage. Largely as a result of earlier discussions with Croizat, Premier Diem acted on the matter on 13 October when he signed a decree which included the following articles:

ARTICLE 1. Effective 1 October 1954 there is created within the Naval Establishment a corps of infantry specializing in the surveillance of waterways and amphibious operations on the coast and rivers, to be designated as:

17

‘THE MARINE CORPS’

ARTICLE 3. The Marine Corps shall consist of various type units suited to their functions and either already existing in the Army or Naval forces or to be created in accordance with the development plan for the armed forces.[2-1]

In accordance with this decree a miscellaneous collection of commando-type units was transferred from the Vietnamese National Army and Navy to the Marine Corps. Except for a naval commando unit, which had conducted amphibious raids along the coastal plains, these forces had operated in the Red River Delta with the French and Vietnamese Navy dinassauts (river assault divisions). First employed in 1946, the dinassauts had evolved into relatively effective naval commands capable of landing light infantry companies along Indochina’s tangled riverbanks. Normally the dinassaut was composed of about a dozen armored and armed landing craft, patrol boats, and command vessels. An Army commando unit, consisting of approximately 100 men, would be attached to such naval commands for specific operations. Thus organized, the dinassauts could transport light infantry units into otherwise inaccessible areas and support landings with heavy caliber automatic weapons and mortar fire. Such operations had been particularly successful in the sprawling Red River Delta of Tonkin where navigable estuaries and Viet Minh abounded.[2-D] Later in the war, as the concept was refined, the French created a number of Vietnamese National Army commando units for specific service with the dinassauts. Still attached to the Navy commands these units were sometimes responsible for security around the dinassaut bases when not involved in preplanned operations. A number of these rather elite Vietnamese units, variously designated light support companies, river boat companies, and commandos, were now transferred to the newly decreed Vietnamese Marine Corps (VNMC).

[2-D] Of the dinassaut Bernard Fall wrote: “[It] may well have been one of the few worthwhile contributions of the Indochina war to military knowledge.” (Fall, Street Without Joy, p. 39) A more thorough analysis of dinassaut operations is included in Croizat, A Translation From The French Lessons of the War, pp. 348–351.

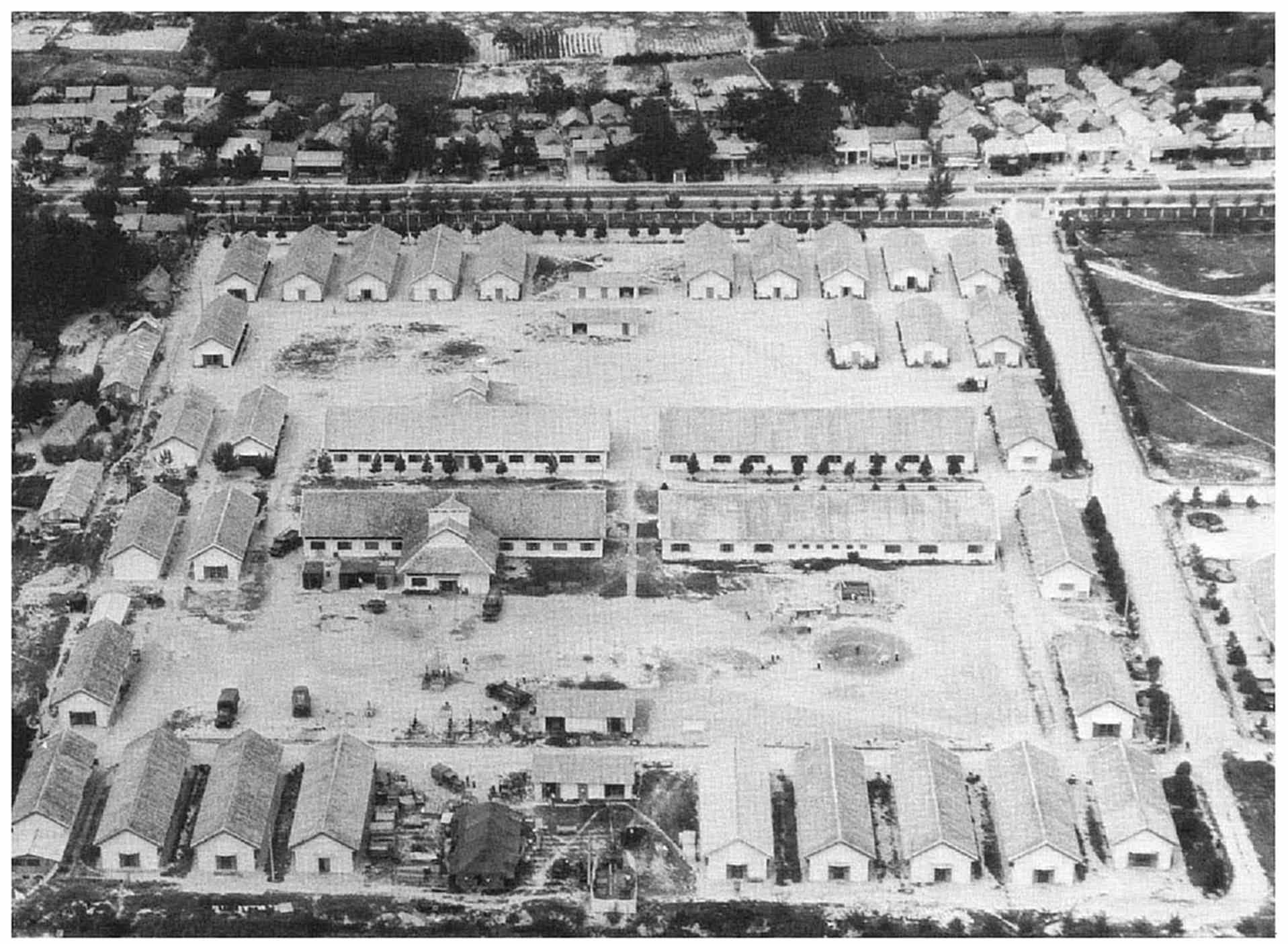

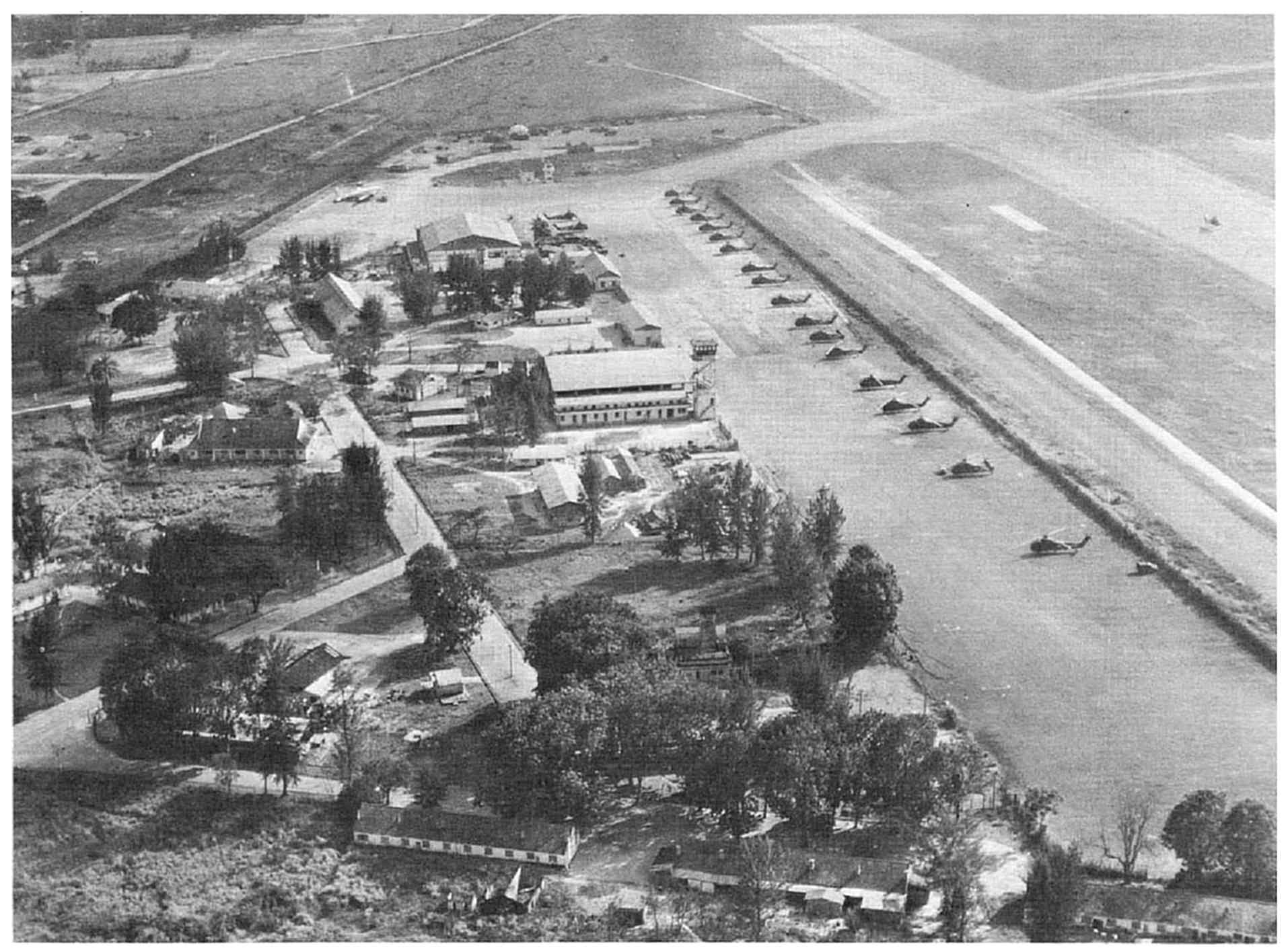

By the time Lieutenant Colonel Croizat returned to Saigon in early 1955 these units, which totalled approximately 2,400 officers and men, had been evacuated from North Vietnam. Several of the commandos had been assembled at Nha Trang on South Vietnam’s central coast where the French still maintained an extensive naval training facility. There, under the supervision of a junior French commando officer, several former commandos had been organized into the 1st Marine Landing Battalion (or 1st Landing Battalion). The balance of the newly designated Marine units, however, were scattered in small, widely separated garrisons from Hue to the Mekong Delta. These units included six river boat companies, five combat support light companies, and a small training flotilla. Diem had appointed a former Vietnamese National Army officer, Major Le Quang Trong, as Senior Marine Officer. But because no formal headquarters had been created and because no real command structure existed, Major Trong remained relatively isolated from his far-flung Marine infantry units.

Upon returning to Saigon, Croizat was assigned to the MAAG’s Naval Section and subsequently to TRIM’S Naval Division as the senior U.S. advisor to the newly created Vietnamese Marine Corps. In this capacity the Marine officer quickly determined that the small Vietnamese amphibious force was faced with several serious problems. First, and perhaps its most critical, was that despite Premier Diem’s decree, the Marine Corps continued to exist essentially on an informal basis. “The Marine Corps itself had no real identity,” its U.S. advisor later explained. “It was a scattering of dissimilar units extending from Hue to the Mekong Delta area.”[2-2] The fact that its widespread units were still dependent on the French Expeditionary Corps for logistical support underscored the weakness inherent in the VNMC’s initial status.

Other problems arose from the continuation of French officers in command billets throughout the Vietnamese naval forces. Under the Franco-American agreement which had created TRIM, a French Navy captain doubled as chief of the combined training missions’ Naval Division and as commanding officer of the Vietnamese naval forces. This placed the French in a position to review any proposals advanced by the U.S. Marine advisor. Complicating the situation even further, a French Army captain, Jean Louis Delayen, actually18 commanded the 1st Landing Battalion at Nha Trang.[2-E]

[2-E] Delayen, described by Croizat as “an exceptionally qualified French Commando officer,” later attended the U.S. Marine Corps Amphibious Warfare School at Quantico. (Croizat, “Notes on The Organization,” p. 3.)

Demobilization presented another potential difficulty for the Vietnamese Marine Corps in early 1955. Under the U.S.-Vietnamese force level agreements, the Vietnamese naval forces were limited to 3,000 men. The Marine Corps, which alone totalled a disproportionate 2,400 men, had been instructed to reduce its strength to 1,137 men and officers. With no effective centralized command structure and so many widely separated units, even the relatively simple task of mustering out troops assumed the dimensions of a complex administrative undertaking.

In short, the very existence of the Vietnamese Marine Corps was threatened in a number of inter-related situations. The continuation of a separate and distinct Marine Corps hinged ultimately, of course, on the overall reorganization of the Vietnamese armed forces and their support structure. Essentially it would be necessary to establish a requirement for such an organization within South Vietnam’s future military-naval structure. Croizat personally sensed that this would be the pivotal issue in determining the VNMC’s future. “There were numerous representatives of the three military services from each of the three countries concerned with the fate of the Vietnamese Army, Navy, and Air Force,” he pointed out. “But, there was no champion from within the Vietnamese Marine Corps since no Corps existed except on paper.”[2-3] Thus, it was left initially to a French captain, a Vietnamese major, and a U.S. Marine lieutenant colonel to keep alive the idea that South Vietnam’s defense establishment needed a separate Marine Corps.

Political Stabilization and Its Effects

During early 1955 the entire South Vietnamese government was engulfed by a crisis which threatened to disrupt the American plans to help build a viable anti-Communist country. The crisis occurred not in the form of an overt North Vietnamese attack but rather as a result of the South’s political instability. In February the leaders of the Hoa Hao, the Cao Dai, and the Binh Xuyen, dissatisfied with Premier Diem’s refusal to accede to their various demands, formed the United Front of National Forces.

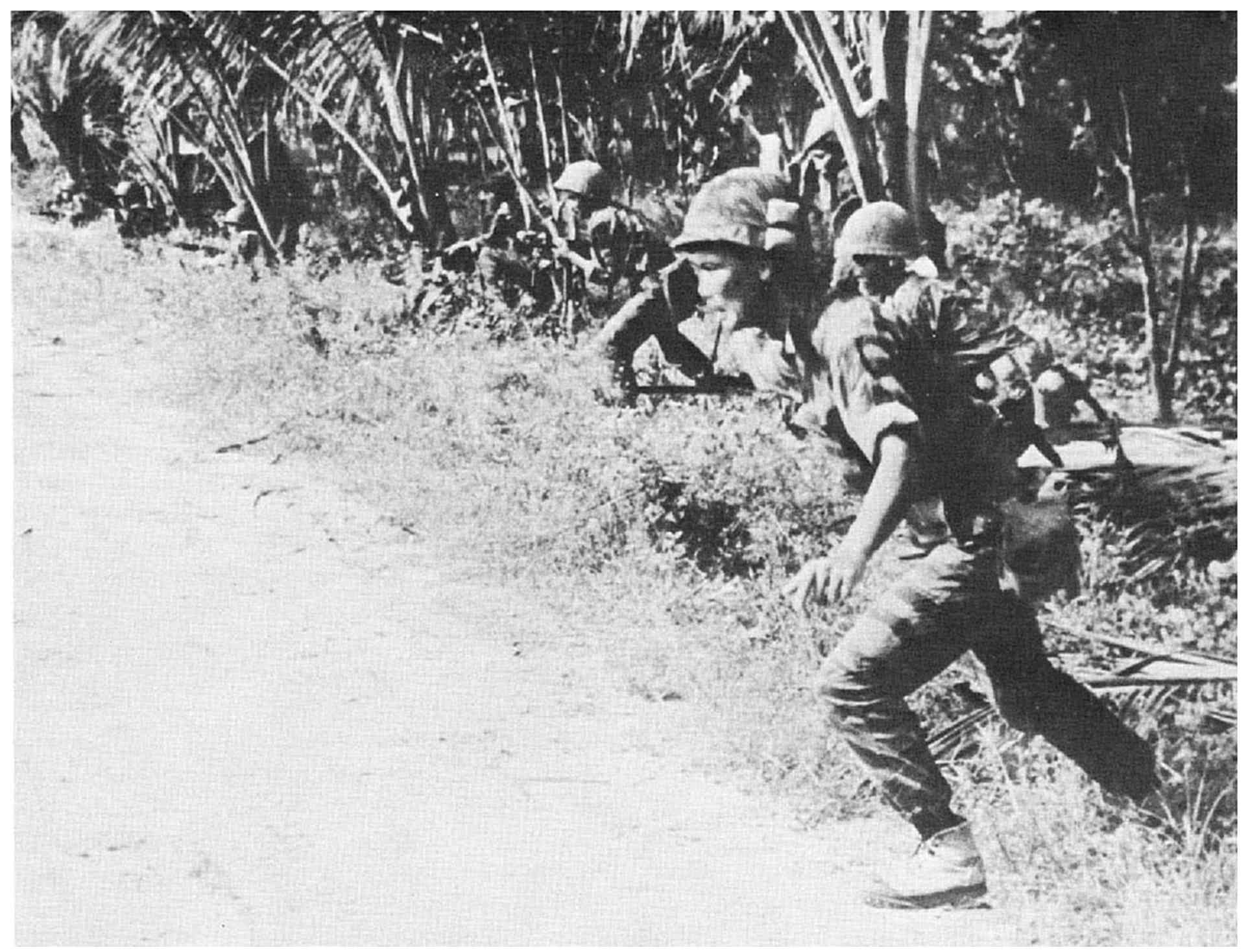

By mid-March the disaffected leaders of these organizations felt strong enough to test the premier’s strength. Trouble began late that month when the Hoa Hao began undertaking guerrilla-type activities against Diem’s National Army units in the sect’s stronghold southwest of Saigon. On 28 March Diem ordered a company of paratroops to seize the Saigon Central Police Headquarters which the French had allowed the Binh Xuyen to control. Fighting erupted throughout the capital the next day as Binh Xuyen units clashed with loyal government forces. A truce was arranged finally in the city on 31 March after three days of intermittent but fierce fighting. That same day the Cao Dai broke with the United Front and accepted a government offer to integrate some of its troops into the National Army.

An uneasy peace prevailed over South Vietnam until 28 April when new fighting broke out. By the middle of May, government forces had driven the Binh Xuyen forces from Saigon, fracturing their organization. Remnants of the bandit group, however, escaped into the extensive Rung Sat swamps south of the capital where they continued fighting individually and in small groups. In the countryside south of Saigon, 30 of Diem’s battalions, including the 1st Landing Battalion, took the offensive against the Hoa Hao regular and guerrilla forces.

The national crisis, for all practical purposes, ended in the last week of June when a Hoa Hao leader surrendered 8,000 regulars and ordered his followers to cease all anti-government activities. Sporadic fighting continued, however, as Diem’s forces sought to mop-up Hoa Hao splinter groups fighting in the western Mekong Delta and Binh Xuyen elements still resisting in the rugged mangrove swamps south of the capital. In August the Marine Landing Battalion fought a decisive action against the remaining Hoa Hao in Kien Giang Province about 120 miles southwest of Saigon, destroying the rebel headquarters. Later in the year the 1st Landing Battalion, joined by several river boat companies, reduced one of the last19 pockets of Binh Xuyen resistance in the Rung Sat. As a result of these and similar actions being fought simultaneously by loyal Army units, organized resistance to Premier Diem gradually collapsed.[2-F]

[2-F] Some sources contend that remnants of the Hoa Hao and Cao Dai armies survived to operate alongside the Viet Cong guerrillas who began threatening the Diem government in the late 1950s. (Kahin and Lewis, The U.S. in Vietnam, p. 111.)

The sect crisis of 1955 proved to be the turning point in Diem’s political fortunes. At the height of the crisis, Emperor Bao Dai attempted to remove Diem as premier by ordering him to France for “consultations.” Electing to remain in Saigon and direct his government efforts to quell the rebellion, the premier declined Bao Dai’s summons. The Vietnamese military forces proved loyal to the premier, having faithfully executed Diem’s commands throughout the emergency. Having successfully met the armed challenge of the sects and the Binh Xuyen and having openly repudiated Bao Dai’s authority, Premier Diem had imposed at least a measure of political stability on South Vietnam.

An epilogue to the sect crisis was written on 23 October when a nationwide referendum was held in South Vietnam to settle the issue of national leadership. In the balloting, since criticized as having been rigged, Premier Diem received 98.2 percent of the total vote against Bao Dai. Three days later, on 26 October, South Vietnam’s new president proclaimed the Republic of Vietnam (RVN).

The Vietnamese Marine Corps benefited greatly from Premier Diem’s successful confrontation with his political rivals. On 1 May, in preparation for the 1st Landing Battalion’s deployment to combat, Major Trong had established a small Marine Corps headquarters in Saigon. Shortly thereafter, Diem had appointed a Vietnamese officer, Captain Bui Pho Chi, to replace Captain Delayen as commander of the landing battalion. The French commando officer, who was a member of TRIM, remained at Nha Trang as an advisor to the VNMC. Then, on the last day of June, Diem removed the remaining French officers from command positions throughout South Vietnam’s naval forces. The combined effect of these actions was to reduce French influence throughout the nation’s naval establishment while making the Vietnamese Marine Corps more responsive to the central government.

The burdens of demobilization also were lightened somewhat as a result of the sect crisis when a new force level was approved by the United States in mid-summer of 1955. The new agreement, dictated in part by the requirement to integrate portions of the sects’ armies into the national forces, raised the force level to 150,000 men and placed the personnel ceiling of the Vietnamese naval forces at 4,000 men. This revision enhanced the prospects for a corresponding increase in the authorized strength of the VNMC.

The 1st Landing Battalion’s performance against the sect forces in the Mekong Delta and the Rung Sat, moreover, tempered much of the previous opposition to a separate VNMC. Heretofore, U.S. and Vietnamese Army officers had opposed the existence of a Vietnamese amphibious force apart from the National Army. Until the sect uprising, Lieutenant Colonel Croizat had used the influence afforded by his position as naval advisor to the general staff to advocate the continuation of the VNMC. But during the sect battles the Vietnamese Marines had firmly established their value to the new government. By displaying loyalty, discipline, and efficiency in combat, they had spoken out in their own behalf at a critical juncture in their corp’s existence.

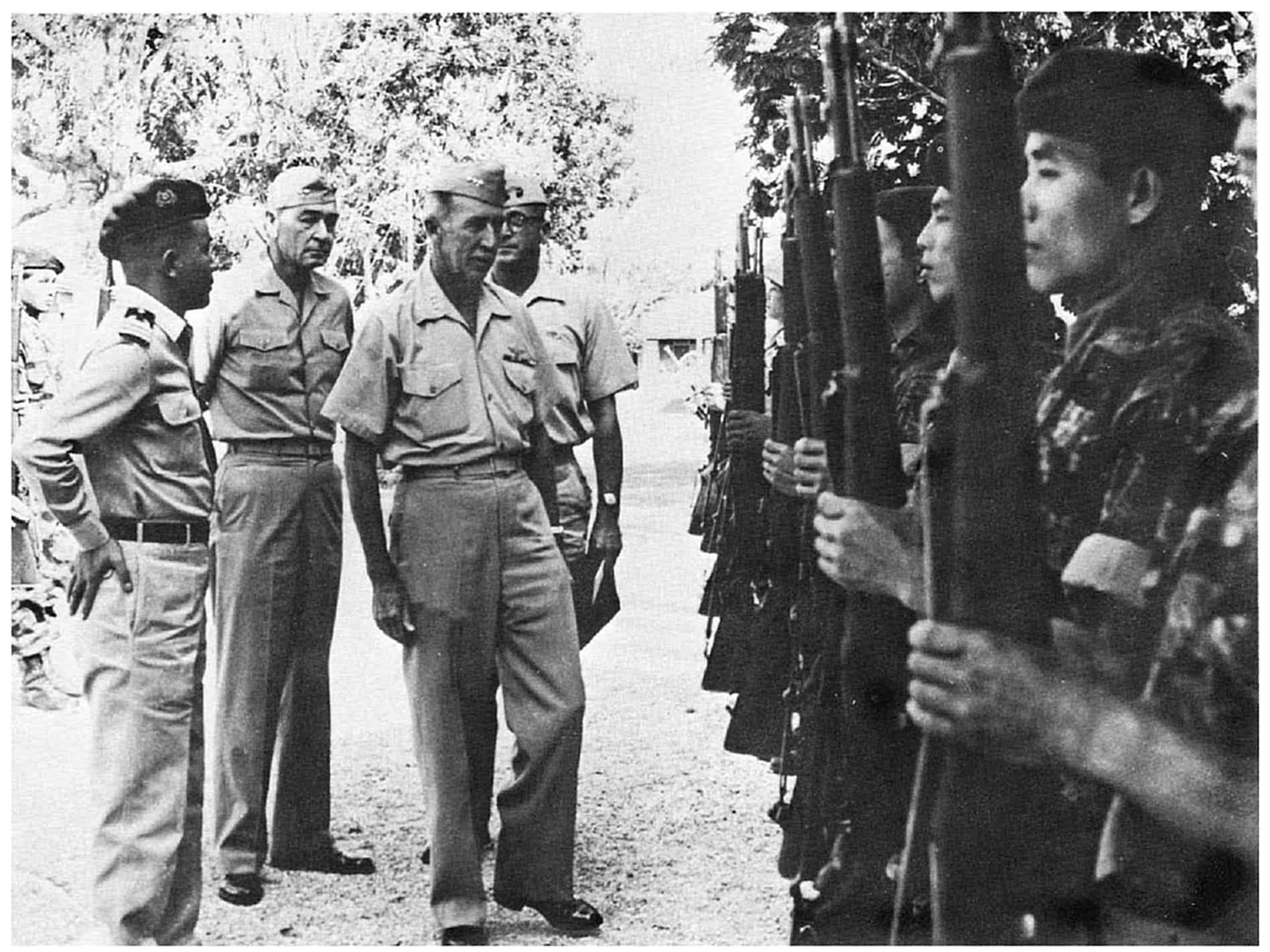

Shortly before the 1st Landing Battalion deployed to fight the rebellious sect forces, two additional U.S. Marine advisors—an officer and a noncommissioned officer—arrived in South Vietnam for duty with the MAAG. Both Marines were assigned to TRIM. Croizat dispatched the officer, Captain James T. Breckinridge, to Nha Trang where he soon replaced Captain Delayen as advisor to the 1st Landing Battalion. As State Department policy prohibited U.S. military personnel from participating in combat activities with indigenous forces, Breckinridge was forced to await the battalion’s return from the field. During its absence he divided his time between Nha Trang and Saigon where he assisted Colonel Croizat with planning and logistics matters. The noncommissioned officer, Technical Sergeant Jackson E. Tracy, initially remained in Saigon but later moved to Nha Trang. There, serving principally as a small unit tactics instructor to the Vietnamese Marines, Tracy impressed Breckinridge as a “first-rate20 Marine ‘NCO’—one who could carry out the most complex assignment with little or no supervision.”[2-4]

Soon after 1956 opened, President Diem appointed a new officer to head the Vietnamese Marine Corps. On 18 January Major Phan Van Lieu assumed command of the VNMC, and thereby became the second Senior Marine Officer.

Reorganization and Progress

The 1st Landing Battalion remained in action against the Binh Xuyen remnants until February 1956. During this period Lieutenant Colonel Croizat reviewed the entire organizational structure of the Vietnamese Marine Corps. By now the size of the service had been reduced to roughly 1,800 officers and men although it retained its original organization of six river boat companies, five light support companies, a landing battalion, a training flotilla, and a small headquarters.

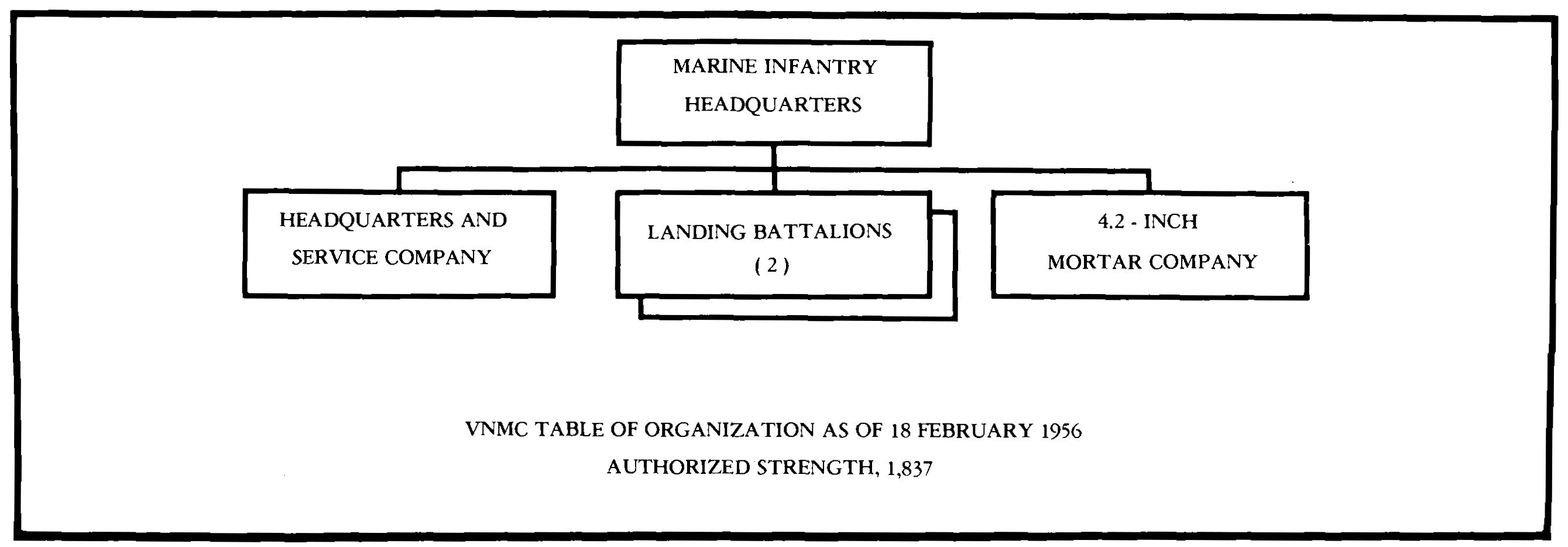

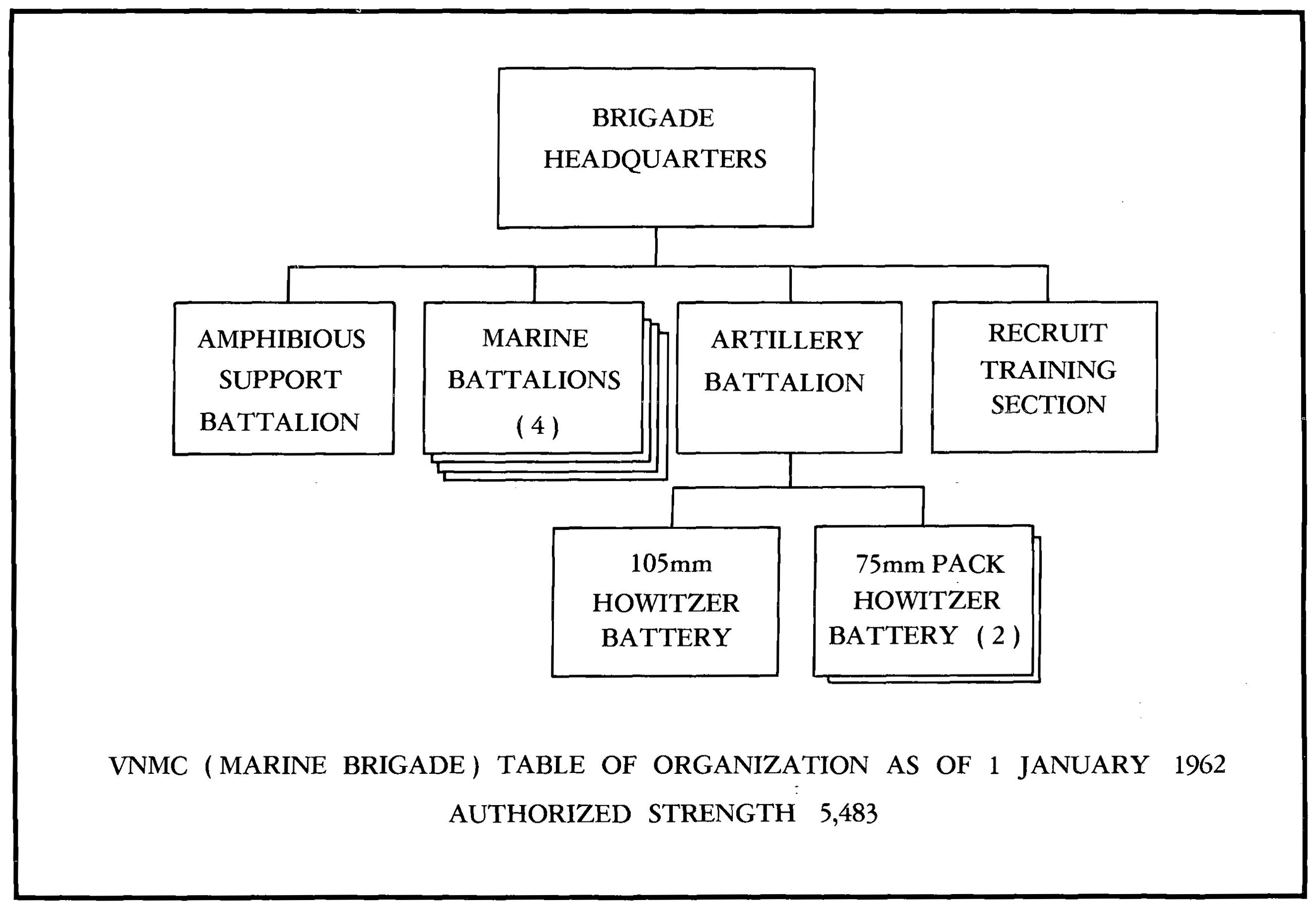

This organization, with so many dissimilar units existing on one echelon, influenced Croizat to suggest that Major Lieu restructure the service. Assisted by Croizat, Captain Breckinridge, and Technical Sergeant Tracy, Lieu and his small staff spent several months developing and refining plans for the comprehensive reorganization of the Marine Corps. Lieu submitted this package to the Vietnamese Joint General Staff (JGS) on 21 December 1955. The salient feature of the plan was to create an additional landing battalion without increasing the 1,837-man ceiling which then governed the size of the VNMC. Significantly, the plan contained a clause proposing that the Vietnamese Marine Corps be expanded to regimental size in the future.[2-5]

VNMC TABLE OF ORGANIZATION AS OF 18 FEBRUARY 1956

AUTHORIZED STRENGTH, 1,837

LANDING BATTALION TABLE OF ORGANIZATION AS OF 18 FEBRUARY 1956

AUTHORIZED STRENGTH 728

The Vietnamese Joint General Staff approved the new structure, and reorganization of the22 VNMC was begun when the 1st Landing Battalion finally returned to Nha Trang in February. The old river boat and light support companies were disbanded and three new units—a 4.2-inch mortar company, a headquarters and service company, and a new landing battalion—were formed. Designated the 2d Landing Battalion, this new unit formed about 25 miles south of Nha Trang at Cam Ranh Bay where the French had trained amphibious forces during the latter stages of the Indochina War.

As a result of the 1956 reorganization effort, the tables of organization and tables of equipment for the Vietnamese Marine battalions were completely revised. Three infantry companies, a heavy weapons company, and a headquarters and service company now comprised a landing battalion.[2-G] Each infantry company was organized into three rifle platoons and a weapons platoon. In turn, the rifle platoons each consisted of three 10-man squads (three 3-man fire teams and a squad leader). The individual Vietnamese Marine rifleman was armed with the .30 caliber M-1 carbine, a weapon formerly carried by many French and Vietnamese commandos. It had been retained for use within the VNMC because it was substantially shorter and lighter than the standard U.S. infantry weapon, the M-1 rifle, and was therefore better suited to the small Vietnamese fighting man. The automatic rifleman in each Vietnamese Marine fire team carried the Browning automatic rifle (BAR), a heavier .30 caliber automatic weapon. The weapons platoon of the rifle company was built around six .30 caliber light machine guns. Within the heavy weapons company of the landing battalions was a mortar platoon, equipped with four 81mm mortars, and a recoilless rifle platoon.

[2-G] Whereas U.S. Marine infantry companies were designated by letters (A, B, C, D, etc.), the Vietnamese Marine infantry companies were given number designations.

While this reorganization was underway, Lieutenant Colonel Croizat initiated a search for acceptable means of expanding the Vietnamese Marine Corps to regimental size. A staff study produced by the Senior Marine Advisor a month before the first phase of the reorganization effort had begun included several important recommendations. Croizat proposed to General O’Daniel that authorization be granted to raise the ceiling on the VNMC from 1,837 to 2,435 officers and men. This, the Marine advisor pointed out, could be accomplished without affecting the overall ceiling on all South Vietnamese military and naval forces. By reassigning to the Vietnamese Marine Corps an amphibious battalion still organized within the National Army, the 150,000-man force level would not be altered. This would transform the Vietnamese Marine Corps into a three battalion regiment and would unify all South Vietnamese amphibious forces under a single command. Croizat’s study further recommended that the Vietnamese Marine Corps be designated part of the general reserve of the nation’s armed forces and that it be controlled directly by the Vietnamese Joint General Staff. Although no immediate action was taken on these recommendations, they were to serve as a blueprint for the future expansion of the VNMC. Equally important, they bore the seed that would eventually make the Vietnamese Marine Corps a fully integrated component of South Vietnam’s defense establishment.

During the ensuing three years, several apparently unrelated occurrences impacted either directly or indirectly on the U.S. Marine advisory effort in South Vietnam. The French completed their military withdrawal from South Vietnam and dissolved their High Command in April 1956, slightly ahead of schedule.[2-H] In conjunction with this final phase of the French withdrawal, the Training Relations Instructions Mission was abolished. Thus, it was no longer necessary for the MAAG programs to be executed through the combined training mission.

[2-H] A few French naval officers and noncommissioned officers remained at Nha Trang as instructors until late May 1957.

Shortly after the departure of the last French troops, Lieutenant Colonel Croizat ended his assignment as Senior Marine Advisor. He was replaced by Lieutenant Colonel William N. Wilkes, Jr., in June 1956. A veteran of the Guadalcanal campaign, Wilkes came to Vietnam from Washington, D.C. where he had recently completed a French language course. Like his predecessor, the new Senior Marine Advisor was scheduled to serve in Vietnam for two years.

In August, less than two months after Lieutenant Colonel Wilkes’ arrival, President Diem appointed23 a new officer to head his Marine Corps. This time Bui Pho Chi, the captain who had commanded the 1st Landing Battalion during the sect uprising, was selected for the assignment. Chi’s appointment was only temporary, however, for in October Diem ordered Major Le Nhu Hung to assume command of the Marine Corps. Major Hung, who became the VNMC’s fourth Senior Officer, was to hold the position for four years.

An attempt to abolish the Vietnamese Marine Corps coincided with the series of changes in its leadership and the departure of Lieutenant Colonel Croizat. During the summer months, the Vietnamese Minister of Defense proposed that the VNMC be made a branch of South Vietnam’s Army. Fortunately, the recent combat record of the 1st Landing Battalion outweighed the minister’s influence and the effort to disestablish the Vietnamese Marine Corps was thwarted.

Another noteworthy incident in the record of the early relations between the U.S. and Vietnamese Marines occurred when the Marine noncommissioned officer billet within the MAAG was upgraded to an officer position. This adjustment, which anticipated the creation of the 2d Landing Battalion, had the effect of making a U.S. Marine officer available to advise individual VNMC battalions on a permanent basis. Thus originated a plan whereby a U.S. Marine officer would advise each Vietnamese Marine battalion—a concept abandoned only temporarily between 1959 and 1962.

The Vietnamese Marine Corps continued as a two-battalion regiment under the command of Major Le Nhu Hung from mid-1956 through 1959. During this period Lieutenant Colonel Wilkes and his successor, Lieutenant Colonel Frank R. Wilkinson, Jr., a Marine who had served as an aide to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, instituted a variety of programs intended to provide the Vietnamese Marines with a common base of experience and training.[2-I] Perhaps the most important of these was one implemented in 1958 whereby Vietnamese Marine officers began attending basic and intermediate level schools at Marine Corps Schools, Quantico. Other formal schools for noncommissioned officers were established by the Vietnamese Marine Corps in South Vietnam. In an effort to build esprit de corps among the lower ranking Vietnamese Marines, the U.S. advisors encouraged voluntary enlistments. They also persuaded their Vietnamese counterparts to adopt a corps-wide marksmanship training program similar to the one then in use by the U.S. Marine Corps.

[2-I] See Appendix A for complete listings of VNMC Commandants and Senior Marine Advisors to the VNMC during the 1954–1964 period.

In conjunction with the reorganization of the VNMC and the stress being placed upon small unit and individual training, much of the U.S. advisory effort during this period was devoted to logistics. The Marine advisors soon discovered that the Vietnamese officers, who had not been directly concerned with supply matters under the French, tended to ignore this important area. “The real problem,” explained Captain Breckinridge, “was the newness of it all. The Vietnamese officers simply possessed no base of experience or training in logistic matters.”[2-6] This shortcoming dictated that the American advisors not only design a workable logistics system but closely supervise its operation as well. Wilkes and Wilkinson instituted intensive schooling of supply and maintenance personnel and emphasized the value of command supervision to the Vietnamese leaders. The Marine advisors, for example, taught their counterparts that equipment shortages could often be prevented if command attention were given to requisitions. Still, even with constant supervision and formal schooling, the Vietnamese Marine Corps continued to experience problems in this area throughout the 1950s and well into the next decade. Breckinridge, who returned to serve with the Vietnamese Marines again as a lieutenant colonel in the late 1960s, recalled shortages of such vital and common items as small arms ammunition even then.

The years between 1955 and 1959 also saw the Marine advisors working to overcome a potentially more serious problem, one that also dated from the French-Indochina War. From the outset of their experience with the Vietnamese Marine Corps, the Marine advisors perceived that a strong defensive orientation seemed to pervade every echelon of the small service. Most Americans, including U.S. Army advisors who were encountering similar difficulties with the Vietnamese Army, agreed that this “defensive psychology” was a by-product of the long subordination of the24 Vietnamese National forces to the French High Command. Indeed, a criticism frequently voiced by USMAAG officials during the Indochina War had been that the French tended to frustrate the development of the Vietnamese military forces by assigning them static security tasks rather than offensive missions. Even though the forerunners of the Vietnamese Marine battalions had operated as commando units, they too had seen extensive duty protecting dinassaut bases and other French installations. Now this defensive thinking was affecting the attitude of the Vietnamese Marine toward training. Moreover, it was threatening the American effort to transform the service into an aggressive amphibious strike force.

By nature this particular problem defied quick, simple solutions. The Marine advisors, therefore, undertook to adjust the orientation of the entire Vietnamese Marine Corps over a prolonged period through continuous emphasis on offensive training. The advisors consistently encouraged their Vietnamese counterparts to develop training schedules which stressed patrolling, ambushing, fire and maneuver, and night movement. In this same connection the Marine advisors translated U.S. Marine small unit tactics manuals into French, whereupon the same manuals were further translated by Vietnamese Marines into Vietnamese. This process assured that adequate training literature was made available to the individual Marine and his small unit leaders. The offensively oriented training programs and the translation project complemented one another, and combined with continuous supervision by the U.S. advisors and the return of young Vietnamese officers from Quantico, gradually helped impart a more aggressive25 offensive spirit to the entire Marine Corps.

Summing Up Developments

The years between 1955 and 1959 constitute perhaps the most critical and challenging span in the chronicle of the Vietnamese Marine Corps. Born out of the confusion which dominated South Vietnam in the aftermath of the Geneva Agreement, the embryonic Marine Corps had survived against heavy odds. Even before its scattered components could be drawn together under a centralized command, the Corps had been hurled into combat against the rebellious sects. Over the course of their commitment the Vietnamese Marines had strengthened their own cause through demonstrations of their fighting capability and loyalty. In terms of the VNMC’s continued existence, equally critical battles were being waged in Saigon where the Senior U.S. Marine Advisor and the Vietnamese Senior Marine Officer struggled to gain support for the infant service. It was there, ironically, that the destiny of the Vietnamese Marine Corps ultimately had been decided.

On balance, the interval between 1955 and 1959 was characterized by uncertainty, transition, and problem solving. Never sure of the Marine Corps’ future, the Senior Vietnamese Marine Officer and a handful of U.S. Marine advisors had carried forward their efforts to transform scattered French-inspired river commando units into a coherent and responsive American-style amphibious force. While this transformation was only partially realized, definite progress was apparent. Vietnamese officers had replaced French commanders, and with American guidance, had given their service a strong interim structure. Many of the more serious problems which had plagued the struggling organization since its inception had been identified. With American assistance, solutions to those problems were being developed and tested. So, despite a stormy beginning and a threatened early childhood, the Vietnamese Marine Corps lived.

26

CHAPTER 3

Vietnamese Marines

and the Communist Insurgency

Origins and Early Stages of Insurgency—Insurgency and the Vietnamese

Marine Corps—Ancillary Effects on Marine Pacific Commands—American

Decisions at the Close of 1961

Origins and Early Stages of Insurgency

South Vietnam gave every outward indication that it had achieved a measure of overall stability in the two-year period following President Diem’s election in the fall of 1955. In early 1956 Diem felt strong enough politically to announce his government’s refusal to participate in the reunification elections scheduled for midyear. He based this position upon the argument that free elections were impossible in Communist North Vietnam. The proposed July election deadline passed without a serious reaction by North Vietnam. Equally encouraging was the fact that there had been no noticeable resurgence in the armed power of either the politico-religious sects or the Binh Xuyen. At the same time the American-backed South Vietnamese economy appeared to be gaining considerable strength.

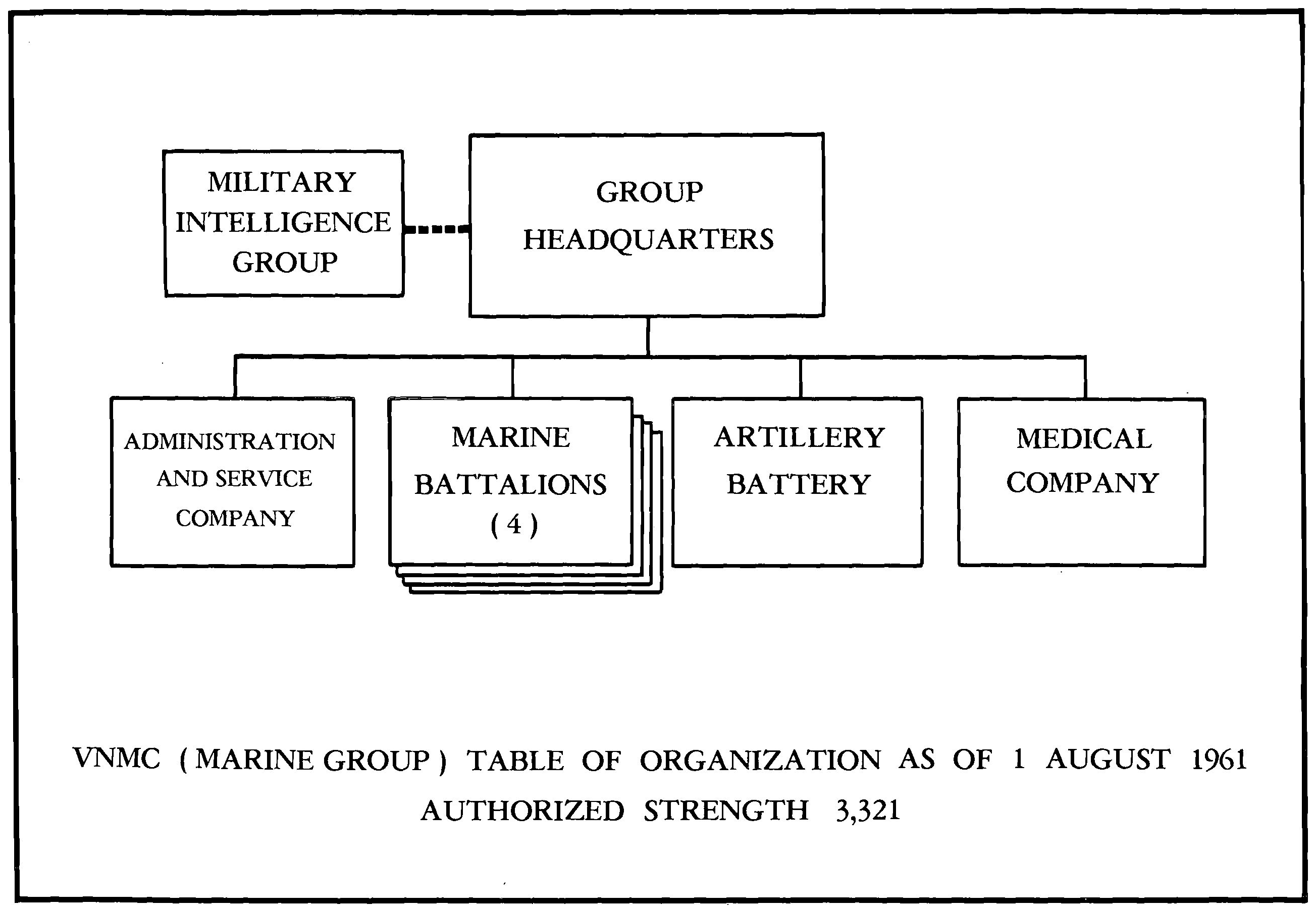

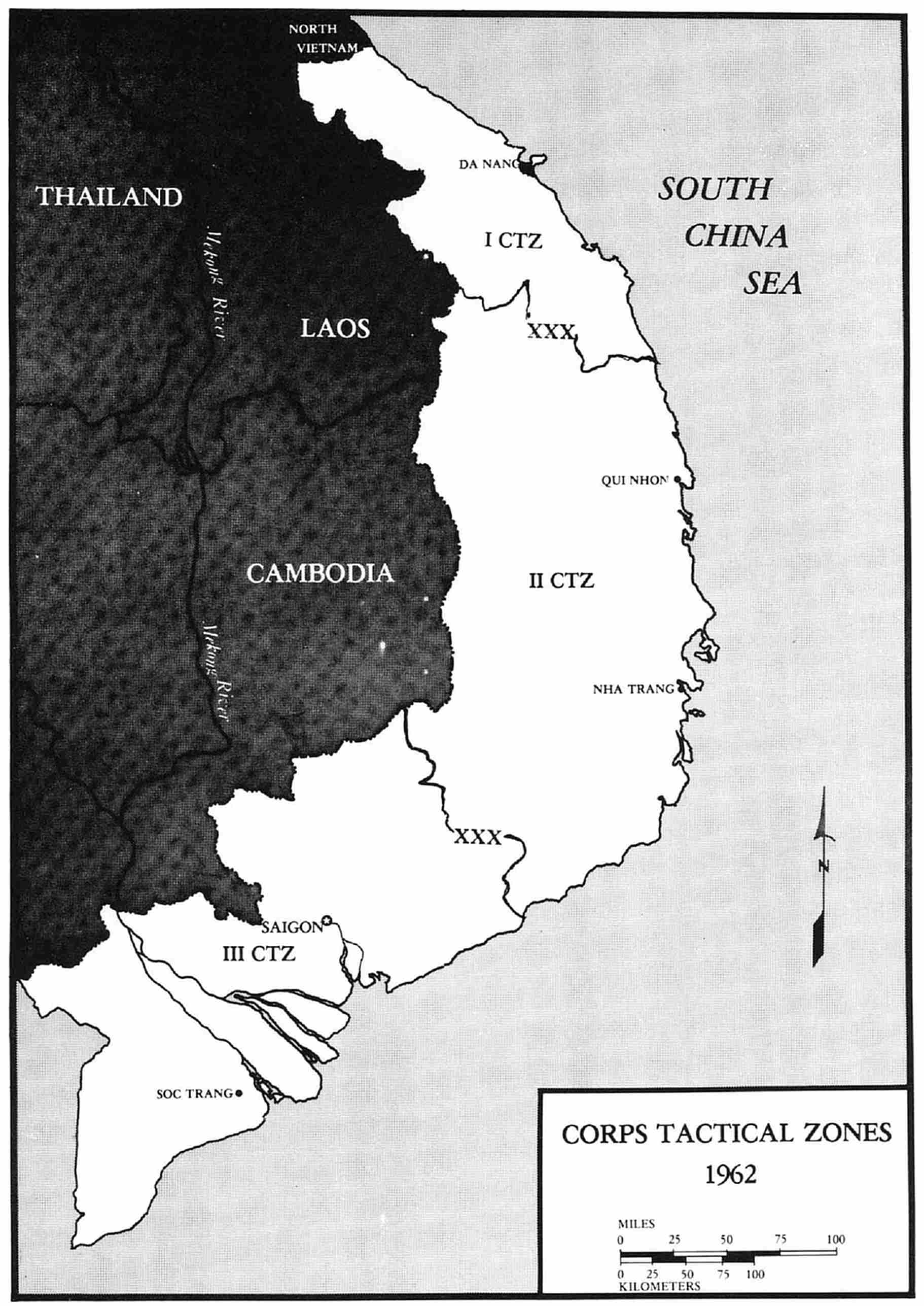

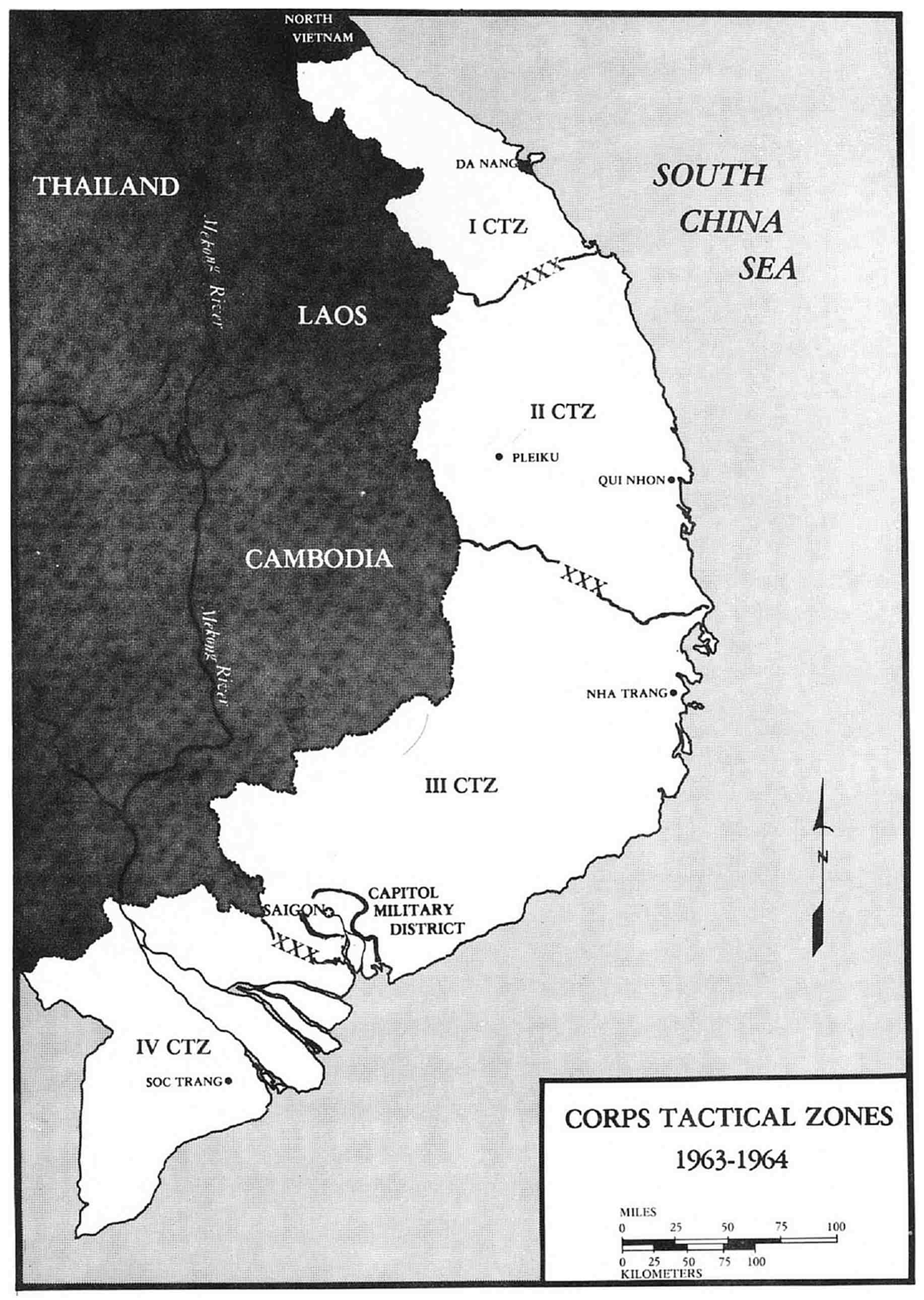

The threat of invasion from the North had also been tempered somewhat by 1958. The MAAG, now headed by Lieutenant General Samuel T. Williams, U.S. Army, a commander respected as a tough disciplinarian, was beginning to reshape the former Vietnamese national forces.[3-A] Renamed the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), the army now consisted of four field divisions (8,500 men each), six light divisions (5,000 men each), 13 territorial regiments (whose strength varied), and a parachute regiment. Although General Williams viewed this as merely an interim organization, it had provided the South Vietnamese army with a unified command structure based on sound organizational principles. The arrival of a 350-man U.S. Temporary Equipment Recovery Mission (TERM) in 1956, moreover, had freed U.S. Army advisors for assignment to each ARVN regiment. American officers were likewise reorganizing and helping train the small27 Vietnamese Navy (2,160 officers and men) and Air Force (4,000 officers and men). The Vietnamese Marine Corps continued to exist as a two-battalion amphibious force within the nation’s naval establishment. General Williams felt confident that by 1958 South Vietnam’s regular military establishment had been strengthened enough to discourage North Vietnamese leaders from seriously considering an outright invasion.[3-1]

[3-A] General Williams would head the MAAG until his retirement in 1960.

Backing these developing regular forces, at least on paper, were two generally feeble paramilitary organizations—the Civil Guard (CG) and the Village Self Defense Corps (SDC). The larger of these, the Civil Guard, existed within the Ministry of Interior and was funded and advised by the U.S. Operations Mission (USOM). Its 48,000 men, therefore, were not charged against the 150,000-man force level ceiling that regulated the size of Diem’s regular forces. Nor were the 47,000 members of the Self Defense Corps, even though this organization received limited amounts of U.S. military assistance funds for payroll purposes. In any case, serious shortcomings were evident in both the CG and the SDC. Organized into provincial companies directly responsible to the various province chiefs, the Civil Guard was entirely separate from the ARVN chain of command. Furthermore, American civilians under government contract had armed and trained the CG for police-type as opposed to military missions. The SDC, essentially a scattering of local militia units, was even weaker, having been organized at the village level into squads and an occasional platoon. Although the SDC units were subordinate to the respective village chief, the ARVN bore the responsibility for providing them with arms and training. More often than not the Vietnamese Army units gave their obsolete weapons to the SDC and showed little genuine interest in training the small units.[3-2]

Although a measure of stability was obviously returning to South Vietnam by 1958, one of the country’s more serious problems remained unsolved—the threat of subversion by Communist Viet Minh agents who had remained south of the 17th parallel following the Geneva cease-fire. Following the resolution of the sect crisis in 1955, Diem turned to neutralize this potential threat. Initially his army experienced some success with pacification operations conducted in former Viet Minh strongholds. While they did help extend government control into the rural areas of several provinces, such operations were discontinued in 1956.

Another policy initiated that same year seems to have nullified the moderate gains produced by the pacification campaigns. Acting both to eliminate Viet Minh sympathizers from positions of leadership at the local level and to extend his own grip downward to the rural population, Diem replaced elected village officials with appointed chiefs. The new policy, which threatened the traditional autonomy of the individual Vietnamese village, was immediately unpopular.

So was another government program which Diem implemented to undercut Communist strength throughout the country—the Anti-Communist Denunciation Campaign. Initiated in mid-1955 to discredit former Viet Minh, the denunciation campaign evolved into something of a witch hunt. By the late 1950s large numbers of Vietnamese with only minimal Communist connections were allegedly being confined in political re-education camps. Like the appointment of village leaders, the denunciation campaign served to alienate Vietnamese who might otherwise have supported the central government in its struggle for control of the rural regions.

Forced underground by the Anti-Communist Denunciation Campaign, Viet Minh agents concentrated on strengthening their political posture for the proposed general election in the period immediately following the Geneva Agreement. When the hope of reunification by plebiscite passed in mid-1956, the so-called “stay behinds” began rebuilding clandestine political cells in their former strongholds. Having retained their aptitude for the adroit manipulation of local grievances, the Communists gradually won support from rural Vietnamese who saw themselves threatened by the new government policies. In mid-1957, the Communists, who were now being labelled “Viet Cong” by the Diem government (a derogatory but accurate term which, literally translated, meant “Vietnamese Communist”) began assassinating government officials in several of the country’s rural provinces. Aimed at unpopular village chiefs, rural police, district officials, and school teachers, the Viet Cong’s assassination campaign was undertaken to erode the government’s contacts with the28 local populace and thereby enhance their own organizational efforts.

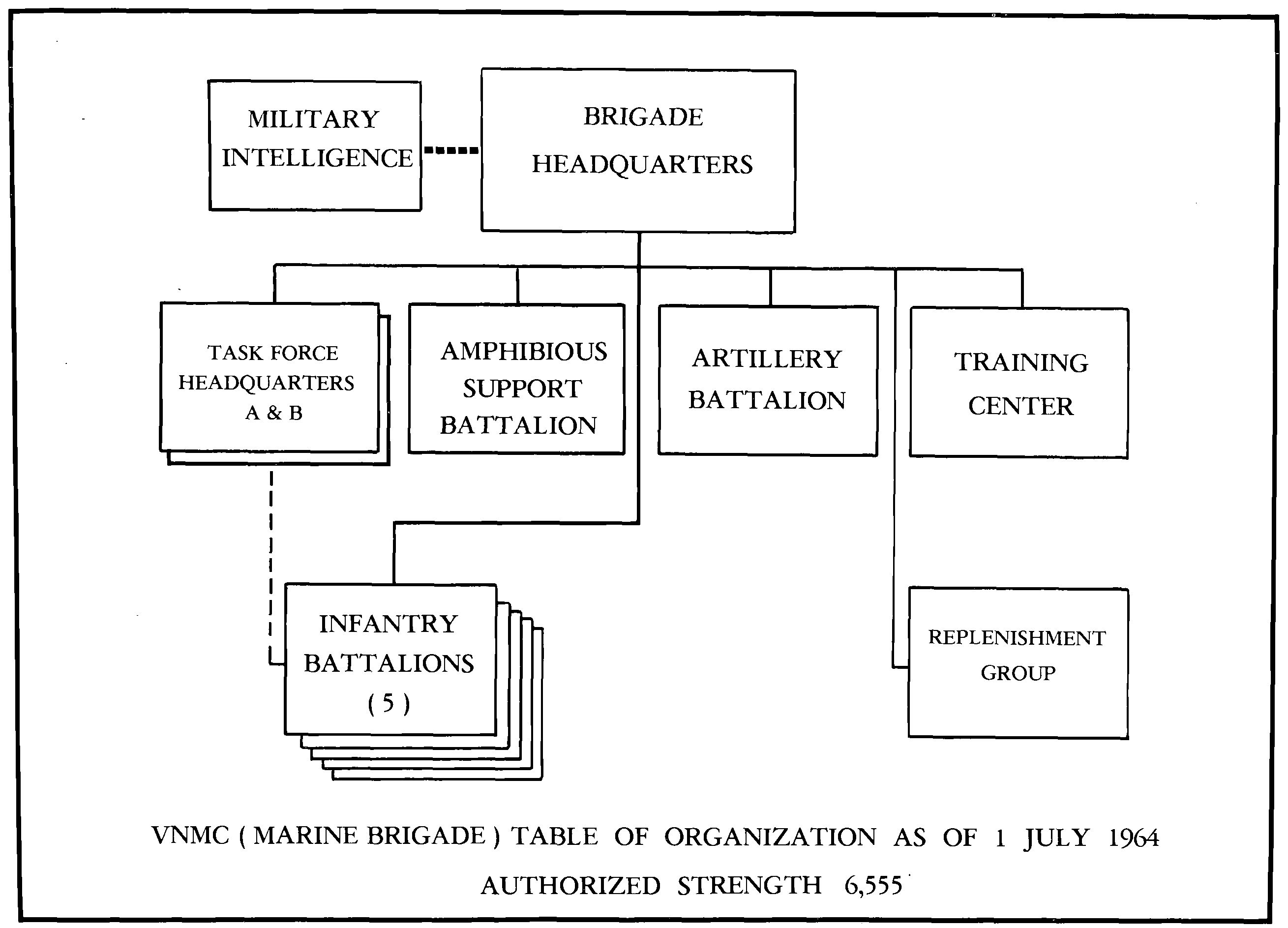

Still faced with the possibility of a conventional attack across the demilitarized zone, President Diem was reluctant to commit his regular military units to a problem which seemed to demand police-type operations. Seeing no clear-cut threat, he relied on the Village Self Defense Corps and the Civil Guard to maintain order in the provinces. Poorly led and equipped, and trained primarily in urban police methods, the paramilitary forces proved unable to prevent the diffuse terrorist attacks. In the 12-month period between July 1957 and July 1958, for example, some 700 more South Vietnamese officials reportedly died at the hands of Communist terrorists.[3-3]