Erica Folger sat cross-legged on the flat, railed platform known to Nantucketers as “the walk,” which perched astride the sloping roof of her aunt’s shabby, well-weathered gray house on Orange Street, overlooking the blue waters of the harbor. The water was very blue on that late October day, and the sunshine very clear and golden on the distant commons of the unromantically named “Pest-house Shore” across the harbor, where the brilliant coloring of autumn was already flaming in a riot of orange sedge, and the red and gold and rose of turning huckleberry.

The air was full of the clean tang of sea salt and of sweet-fern and bayberry, mixed in a most aromatic fragrance. Erica, busy as she was about a highly reprehensible matter of vast importance to herself, sniffed it appreciatively. Vaguely, half her attention otherwise occupied, she decided, as she always decided each year at this time, that October was the best month of the whole twelve. She loved the snap and vigor of the crisp, sweet air, and the alive, ambitious feeling it put into fingers and toes. October smelled of so many interesting things on Nantucket.

Thinking of interesting things, Erica reflected that her present occupation, though undoubtedly interesting to herself, would not in the least interest Aunt Charity. She was sorry that Aunt Charity’s point of view so often ran counter to her niece’s, but Erica, turning to stare critically at her own reflection in the small, square mirror she had propped up on a box before her, felt no regrets as to her recent act of vandalism—which is what Aunt Charity would term it the minute she knew.

Though Erica Folger sat on the high walk above her home and stared at her reflection in the mirror more than eighty years ago—at that time even the Civil War would not be fought for a matter of nearly twenty years yet—she had just achieved, with no known precedent to guide her, a thoroughly modern “bob.” On the floor of the walk, beside her, lay Aunt Charity’s biggest cutting shears, and two thick braids of curly dark red hair, tied at the ends with demure black bows.

Following the shearing process, Erica had shampooed her shorn locks in a pail of warm water she had carried up the ladder when Aunt Charity was otherwise occupied, and now she sat there letting the bright October sunshine dry the new bob. (But Erica, years ahead of her generation though she was, did not know that it would one day be called a bob. She called it giving herself a sensible hair-cut, that should not require the half hour of tiresome brushing Aunt Charity insisted on each evening.)

The hair was almost dry now, and the mirror showed Erica a tumble of short red curls against either rosy cheek on a line with the just-hidden ears. Above the curls and the flushed cheeks were two widely opened eyes of the exact shade of the blue harbor-water below, a straight little nose well supplied with a powdering of faint golden freckles, and below that, again, a rather wide mouth that was made for courage and light-hearted laughter even in the face of discouragement.

Erica shook her head experimentally, and sighed with delight at the free, untrammeled feeling that had replaced the drag of her heavy braids.

“Aunt Charity’ll hate it,” she murmured, but without regret. “And Lis and Tommy’ll laugh. Oh, well, let’s get it over with.”

She rose to her feet, picked up her discarded braids, the mirror, and the pail of water, and carefully negotiated the ladder down to the floor below. It was unfortunate that Miss Charity Folger should have come out into the upper hall just then, and, discovering her always-unaccountable niece halfway down the ladder with a heavy pail of water, stopped aghast.

”Erica!” she said. “For the land’s sake! What were you doing up on the walk with that pail?”

It was too dark in the hall for her to notice Erica’s guilty little head, but at the sound of the unexpected voice below her the girl jumped, and one of the heavy red braids slipped through her clutching fingers. Miss Charity gave a stifled shriek as the long, sinuous object fell limply at her feet. Perhaps she thought it was a snake; but of a certainty her wildest imaginings never reached within a far cry of the truth. She gathered her full skirts higher about her ankles and, after a perceptible hesitation, bent over the puzzling object on the floor. Then, though she was not at all the kind of woman who screams easily, she uttered something that was very much like another little shriek.

“Erica,” she asked, in a much severer voice, “just what have you been doing this time?”

Erica, having by now arrived at the foot of the ladder, plunged eagerly to her own defense.

“I don’t see why only boys should be comfortable, Aunt Charity. I really don’t,” she said, vehemently. “My hair was heavy and hot. I got so I simply couldn’t bear it any longer. And all that brushing and brushing every night of my life! It’s such a waste of time. And—and so I cut it off. It’ll grow again, of course—probably thicker than——”

She stopped, her voice, for all its eager conviction, trailing off limply into silence at the expression on her aunt’s face.

“I—I’m sorry if you really feel badly about it, Aunt Charity,” she offered at last.

“I never know what you’ll do next, Erica Folger,” Miss Charity complained, despairingly. “You had nice hair, and I’ve always tried to see that you kept it in good condition. Her hair’s a woman’s crowning glory, so the Bible says. But of course, if you want to make yourself look a fright. Well, it’s done now and there’s no more to be said about it. I hope you’ll enjoy it.”

Erica put her hands up protestingly to her head. She had thought it looked rather—rather pretty, even if she had never seen a girl wear her hair short before. But now, under Miss Charity’s scathing words, her own enthusiasm fell suddenly flat, like a pricked toy balloon. Perhaps she had just been silly and impulsive again.

“Take that pail of water downstairs, and be careful you don’t spill it all over everything,” Miss Folger ordered, shortly. She had said her say on the other subject, and Erica knew by experience that she would not be apt to refer to it again. That was one of the nice things about Aunt Charity—she never nagged. Perhaps, though, Erica further reflected, uncomfortably, that made it all the worse when she did these unconsidered, impetuous things Aunt Charity worried over.

She went downstairs very soberly. The day had lost some of its early glamour already, but within another hour it was destined to become for Erica a very gray day indeed. Shortly before noon she heard a familiar whistling of an old sea tune from the garden that adjoined the house of her Folger cousins, next door. She went quickly through the dining-room door, out onto the sunny side porch, and whistled vigorously in response.

A tall, long-legged boy of fifteen swung himself easily over the low dividing fence, and was followed by a second long-legged boy, so exactly like him that a stranger might well have been excused for believing his own eyesight was playing him tricks. The only difference between them, which even a keen observer would have noticed at first glance, was that the fair hair of the boy first over the fence had an unruly kink in it that made it stand wildly on end at the slightest provocation, while the equally fair hair of his twin—for they could have been nothing else—was as straight and smooth and tractable as hair could be.

They came up the bricked path side by side, and then, at sight of Erica on the steps, stopped, stared incredulously, and went off into wild whoops of uproarious laughter.

Erica, one hand consciously touching her short locks, waited with obvious impatience until the two saw fit to come to order.

“Yes, I cut it off,” she said, hotly. “You would, too, long ago, if you’d had to drag those everlasting braids about everywhere. It’s comfortable, anyway.”

“Well, it looks queer,” the straight-haired twin said, bluntly. “But I guess it likely does feel more comfortable.”

“And there’s no good talking, as long as it’s cut,” the curly-haired twin added, good-naturedly. “Besides, Rick, we came over to talk about something much more important.”

Both boys’ faces sobered instantly, making them look, somehow, a good deal older. They sat down on the lowest step of the porch and looked up at the girl standing above them.

“We’ve settled the big question at last, Rick,” the one who had spoken last announced. “We spun a coin for it, and Lis stays home with mother and I go to sea as cabin boy in the Flying Spray, sailing out of Boston next week, bound for Macao, Canton, and Cochin-China. Hurrah! Aren’t you going to congratulate me?”

Some of the bright color faded from Erica’s face. She glanced at the straight-haired boy in swift interrogation. He nodded, his own face clouded.

“Yes, Rick, Tommy gets all the luck and adventure, this trip,” he said, ruefully. “Mother can’t be left alone while she’s so poorly, so we agreed to let the toss of a coin settle which was to go and which to stay. No sense in both of us being tied on Nantucket; and this chance came up unexpectedly through Captain Bartlet of the Spray being here for a few days with his sister—Mrs. Macy, you know, over on Pearl Street. He wants a boy for his next trip.”

“It was only decided last night,” Tommy added. “Mother and Captain Bartlet talked it over and agreed one of us should have the chance. They left it to us to say which one.”

“I don’t think an important thing like that ought to be decided by tossing a coin,” Erica objected, weakly. “It’s—well, it’s too much like gambling.”

“Oh, there’s Bible authority for casting lots—same thing exactly,” Tommy retorted. “Anyhow, it’s like your hair, too late to do anything about it now but groan.”

He grinned, and Erica bit her lip, flushing angrily. But the flush died as quickly as it had arisen. With the near prospect of losing one of the cousins who had been her inseparable companions from babyhood, she could not find it in her heart to resent anything teasing Tommy might say.

“I wish I were a boy,” she sighed a moment later. “Then I’d be on father’s ship right now bound home from China.” Her expression became less woe-begone. “La! I do envy you, Tommy! But why didn’t you wait for the Sea Gull? Father always promised one of you two a berth when the time came.”

“Yes, I know, but he won’t be back for months yet, probably,” Tommy replied. “And here was the chance to go right off, next week. Besides, I think it’s better not to sail with your family. Going with Captain Bartlet, I’ll stand on my own merits.” He couldn’t help an unconscious strut of importance, and both Erica and Lister laughed.

“You needn’t be so proud,” the former teased, “I came home from Canton on a clipper myself, before I was a year old; and had a Chinese nurse, too, that Sun Li sent home with me.”

For Erica Folger’s young mother had insisted on sailing with her captain on his voyages after their marriage, and on their second trip to China Erica had been born at sea, and her mother had died just two days from Canton.

“Maybe I’ll meet that mysterious godfather of yours, Rick,” Tommy suggested, out of the little silence that had fallen suddenly over the three. “Funny Uncle Eric won’t ever tell you anything definite about him.”

“Oh, but I do know lots,” Erica said, quickly. “He’s a very rich and powerful merchant in Canton—or at least, I think he’s a merchant,” she added, less certainly. “I know father met him years ago through carrying a cargo for him. And Sun Li had a little son born the same day I was, only his baby died and he’s never had any other children. So as he and father were friends, anyhow, that made him take a very special interest in me. He sent his little dead son’s nurse to take care of me on the voyage home, and every time the Sea Gull touches at Canton he sends me back a lovely present by father.”

The twins nodded, impressed as always by the story and the hint of mystery surrounding it. Also they had seen the “presents” in question, beautifully carved jade of deep, clear green, lengths of rich silks, ivory fans, and cunning teakwood boxes with trick drawers and detachable bottoms; things, as Aunt Charity pointed out disapprovingly, that were far too fine for a simple little Nantucket girl in her early ‘teens.

“Tommy, listen to me,” Erica cried, suddenly, her sea-blue eyes very bright with the new, exciting idea that had come to her. “It’s just possible that you will meet Sun Li if the Spray goes to Canton. Anyway, I’m going to give you something that will introduce you to him as my cousin if you do.” It was Erica whose voice held an important note now, but both her listeners were too absorbed to smile. “Wait here for me,” she added, eagerly. “I’ll be right back.”

She ran into the house, slamming the porch door behind her in the headlong tomboy fashion nothing that Miss Charity could say had succeeded in moderating. The twins heard her flying feet on the steep, carpeted stairs, and a moment later heard her come racing down them again.

She held a small ebony box very carefully in one hand, and, opening it, drew out a heavy gold ring set with a green jade seal. There were strange Chinese characters cut in the stone, and the ring itself formed a conventional dragon’s head, which held the seal in its wide-open mouth.

“Remember this?” she asked, breathlessly, holding it out to Tommy. “He sent it to me two years ago. Father said I was always to take great care of it, because it was Sun Li’s private seal, and the ring would have belonged to his son if he had lived. I’m going to give it to you, Tommy. When you’re in Canton, you can try to find out whose seal it is, and go to see Sun Li.”

“But he may not like that, Rick,” Lister interposed, his tone troubled. “If Uncle Eric hasn’t told us much about him, perhaps its because he’s been asked not to. Sun Li may not care to have visitors from across the ocean.”

“I don’t see why not,” Erica objected. “Anyhow, Tommy can use his judgment. He can inquire round a bit first, if you think he’d better——”

“Tommy’s judgment is just about as much to be relied on as your own,” Lister said. But his smile was gentle for her, as always. Lister felt himself years older, most of the time, than his twin and Erica.

Tommy took the ring and tried to slip it on his fourth finger. But it proved too small for that one, and too large for his little finger. He stared at it, frowningly, his face full of ingenuous disappointment.

“Never mind. You can wear it round your neck, like a sort of talisman,” Erica giggled. “I’ve got just the very cord for that—it’s Chinese, too. It came round the last box Sun Li sent me.”

She dashed upstairs a second time, and returned carrying a dark-blue cotton cord of a curious weave, knotted at intervals. Taking the ring from Tommy, she slipped it over one end of the cord, adding still another knot to the collection, which secured both ends firmly together. Then, with the air of a queen bestowing the accolade of knighthood on a subject, she flung the cord itself over Tommy’s fair, ruffled head, and tucked the ring down inside his collar.

“It’s safer to wear it out of sight, anyhow,” she advised him. “There are always rough men in those clipper crews, and you might have the ring stolen, if they knew you had it.”

She sat down, still breathless after her run upstairs, on the step between her two cousins and slipped an arm through an arm of each of them. Another little silence fell. In the midst of their banter and laughing plans the realization seemed to have seized on all three at once, that there were only a few more days left of the old, happy companionship.

Characteristically enough, it was Tommy who spoke first.

“Oh, well,” he observed, philosophically. “I won’t be gone more than a year. Probably not so much. The Spray’s one of the fast clippers, you know. Rick’ll just have time to let that silly hair-cut grow out long enough to wear the ivory comb I’ll bring her back from Canton or Cochin-China, in exchange for Sun Li’s ring.”

“All right,” Erica flashed back, her eyes bubbling over with fun again. “I’ll put it with all the rest of the Chinese presents Aunt Charity won’t let me use yet. But I’m not going to let my hair grow,” she added with firmness. “It’s much too comfortable this way.” Which again, had Erica only known it, was a remark that a good many other girls were destined to repeat, in the same tone of conviction, eighty years later.

The cobblestones of Main Street—until recently known as State—were slippery after a heavy shower, and Erica, picking a careful way across them that she might not bespatter her white stockings with mud, spied a plump and dignified figure in sober Quaker garb wending its way up the street ahead of her, and called after it, anxiously: “Mrs. Macy! Oh, Mrs. Macy, please!”

[Illustration]

The plump little lady turned at the sound of her name, smiling. “Good morning, Erica,” she said. “Was thee trying to overtake me, my dear?”

“Yes, ma’am.” Erica was panting with her own hurry. “But you walk twice as fast as Aunt Charity. I was just going to your house with a message. Aunt Charity wants that you and Captain Bartlet should come to supper tomorrow night at six o’clock. You know Tommy is going to sea in the Spray and—” A sudden twinkle in the little old lady’s blue eyes was answered by a twinkle in Erica’s. “Yes’m, I guess Aunt Charity thinks it’s her bounden duty to talk to Captain Bartlet about Tommy.”

“Walk home with me, my dear, and we’ll ask the captain,” Mrs. Macy invited. “For my part, I shall be pleased to accept. How does thee feel about Tommy’s going? Won’t thee and Lister both miss him very much?”

Quick tears blurred Erica’s eyes, but she pretended to be looking at something across Main Street, and wiped them away fiercely with the back of her hand—having, as usual, mislaid her neat white pocket handkerchief.

“Yes, ma’am, we will,” she said, dully.

The more she had thought about Tommy’s departure during the past three days since she had heard the news, the more utterly calamitous it seemed to her. But Erica’s code was the code drilled into her by Lis and Tommy, which insisted that tears, particularly in public, were shameful even for a girl; also that whining over what was fixed and settled was something only spoiled children did. Besides, Tommy was in the seventh heaven of delight at the prospect of his first voyage. Even delicate Aunt Callie, his mother, tightened her lips and tried to smile at his raptures, instead of dwelling on her own sense of loss.

“Yes’m,” Erica repeated, “we’re going to miss him, I expect.”

They turned into Center Street, and walked two blocks along it to Pearl—the latter name, changed a few years before, unfortunately, from India Street. Mrs. Macy’s house was small and neat and white, set back from the street behind a prim garden blazing with late fall dahlias, Spanish Browns, and small, hardy chrysanthemums.

A tall man with iron-gray hair and a gray beard stood in the open doorway, glancing up at the clouds breaking overhead after the rain.

“Judson,” Mrs. Macy greeted her brother, “thee needn’t study the sky for an hour. I can tell thee that it’s going to clear, unless the fog comes in again. Here’s Erica Folger bringing us an invitation from Miss Charity to supper tomorrow night—” She broke off with a little gasp. “La, Erica! what has come of thy nice thick braids?”

For without thinking what she was about, Erica had snatched off her bonnet, which had heretofore hidden her revolutionary hair-cut, and was fanning herself vigorously, swinging it by its strings. Erica hated bonnets among the many other restraining things of life that seemed to her young impatience so needless.

Now, startled, her hand flew self-consciously to her head, and her smile was sheepish.

“I forgot, or I wouldn’t have taken my bonnet off,” she admitted. “I cut my hair off day before yesterday. I’ve wanted to for a long while. My braids were so heavy and troublesome, and I’ve always envied Tommy and Lis being so—so free. At last I just chopped them off. Aunt Charity was like to have fainted when she saw me.”

“I don’t wonder,” Mrs. Macy said, decidedly. “My dear, who ever heard tell of a girl with short hair? If it had been Mollie, I don’t know what I would have done.”

Here Captain Bartlet interposed, seeing Erica’s cheeks crimsoning a deeper hue of combined anger and mortification.

“Belay there, Mary,” he said in his deep, kindly voice. “Thee is making the lass unhappy. And there’s no more use crying over a shorn head than over spilled milk, as I see it.” He looked at the red bob shrewdly. “Never having been a lass, I can’t say how they’re supposed to feel,” he added, a slow smile showing above the neatly trimmed gray beard, “but I guess that crop of red curls ought to be a sight easier to carry about than full sail. Hey?”

Erica flashed him a grateful smile. “Yes, oh, it is! Ever so much lighter and easier, Captain Bartlet!”

“Kind o’ pretty, too,” he said, gallantly. “An’ grows prettier the longer I look at it. Seems to me I used to know thee as a baby, or not much more’n one. Isn’t thee a sister of my new cabin boy, missy?”

“No, I’m his cousin,” Erica said, approving of this big, bluff, friendly Quaker captain more and more. She was so thankful he was like this, for Tommy’s sake. She felt suddenly emboldened to put her muscular, tanned young hand on his arm pleadingly. “He’s a nice boy—Tommy,” she said, breathlessly. “He—he really is. He’ll learn quickly. And—and I’d rather be going to sea, too, than anything in this world.”

“Ho!” said the captain, with a great shout of laughter. “So that’s why thee cut off the pigtails, missy?” He shook a huge forefinger at her playfully. “Some day thee’ll be adopting boy’s clothes, as well as a hair-cut, and running off to sea in my ship.” At sea, Captain Bartlet usually fell into the more usual “you” and “your,” but ashore in Nantucket he was always scrupulous about the Friends’ mode of speech.

“I’d like to,” Erica laughed back. “Only, if I did run, it would be in my father’s ship. He’s got a clipper, too, in the China trade.”

“Not Captain Eric Folger of the Sea Gull?” the other demanded in surprise. “Somehow, I’d forgotten to associate him with Nantucket, though I’ve known thy Aunt Charity and Tommy’s mother for years. Last voyage but one, the Spray and the Sea Gull lay side by side in the harbor at Canton, waiting for a fog to lift and let us up to the city.”

“I’ve been there, too,” Erica said, impulsively. “Only I don’t remember it. I was born at sea, two days before we put in at Canton. My mother died there, and a great friend of father’s—a Chinese merchant named Sun Li—sent his little son’s nurse on board to take care of me on the way home. Ever since then, every voyage father makes to China he brings me home a present from my Chinese godfather. That’s what he calls himself. Aunt Charity won’t let me wear the things yet, because she says they’re too gorgeous. But some of the jade has his seal on it—maybe you’d know him from it—like this.” With her finger nail she traced an intricate pattern of characters in the smooth dirt of a flower pot on the porch railing, looking up eagerly at the captain when it was done.

He bent over it, smiling at her enthusiasm, but when he lifted his head his expression was faintly astonished and puzzled.

“I don’t know of any merchant named Sun Li,” he said, but he bent once more and studied the crude little drawing in the dirt. “Thee is sure thee has it right, my dear?”

“I have every line by heart,” Erica said, proudly. “I’m sorry you don’t know him. Father does some trading with him, I think.”

“I don’t know him,” the captain repeated, but his thoughts were suddenly busy. Captain Folger of the Sea Gull was a name synonymous with fast voyages, also with better cargoes, more quickly loaded, than most of the clippers could boast. There had been rumors of special high protection—of favors and concessions shown the Nantucket man. Of course, it may all have been idle gossip of the water front and the bazaars. But Captain Bartlet had certainly seen a seal once before like these few scratched marks in the dirt of his sister’s flower pot. Only he knew of no one named Sun Li.

Erica hurried down the brick walk, anxious to find Tommy and report the captain’s genial mood. “I’ll tell Aunt Charity you will both come tomorrow,” she called over her shoulder to Mrs. Macy.

The boys and Erica were not permitted to be present at the supper party on the morrow. Aunt Callie was there, of course, and Mr. Presbyn, the Congregational minister, besides Mrs. Macy and the guest of honor, and the table groaned under a load of the good things Aunt Charity’s kitchen was famed for producing—home-cured sugar-baked ham; flaky soda biscuits still smoking from the oven; steaming, fragrant coffee in the old Folger silver pot; thick cream for the coffee and for the deep-apple pie that came afterward; unsalted butter, churned at home; and ginger preserve made from real ginger roots that had been brought across the Pacific in a tea clipper.

Erica, invited to keep the twins company at supper in Aunt Callie’s cheerful brick-floored kitchen, made their mouths water cruelly with a vivid account of the feast spread for their elders and betters on Aunt Charity’s side of the fence, meanwhile munching with zest fresh gingerbread and baked apples, washed down with glasses of cold, creamy milk.

“You’re awfully glad to be going to sea, Tommy, aren’t you?” she asked, wistfully, later, when the meal was over and the three had washed the supper dishes gayly, and now sat at ease before the huge fireplace, with its swinging crane, and the old Dutch oven at the side. (Aunt Callie still clung, as so many island housewives did, to the custom of cooking over the open fire.)

“‘Course I’m glad,” Tommy said, lolling back in his big chair with lazy content. And he added, teasingly: “Don’t you wish you were a boy? Poor Rick!”

“Yes, I do,” Erica declared, “but I’m not going to sit here all evening moaning about it. There’s the most gorgeous full moon outside—the ‘Hunter’s Moon,’ don’t they call it? Let’s all go down to the wharf and take a last look at Captain Joy’s Narwhal. She’s sailing tomorrow morning at high tide. A ship out in that harbor with the full moon on her is somehow awfully exciting. They always make me think of pirates, the sails look so black and mysterious against the moon.”

The Narwhal was a whaler, bound for the South Seas on what would probably be a three-year cruise, and Erica and the twins had known her captain and crew (most of them Nantucket men) as long as they could remember.

“Do you think Aunt Charity will like you to go down there so late?” Lister asked, doubtfully. Girls were supposed to sit at home in those days, when even the mildest of adventures were afoot.

“Oh, Tommy and you can protect me,” Erica retorted, flippantly. “Anyhow, I’m in disgrace with Aunt Charity already, on account of my hair, so a bit more or less won’t matter.” She was bundling on her wraps as she spoke, for the evening was cold outside with the chill of the strong northeaster blowing in from the sea.

Knowing Erica’s stubbornness of old, the twins pulled on caps and overcoats and followed her to the back door. Lis offered one final protest, but half-heartedly. “And mother won’t like it if we leave the house alone, with the fire burning and the lamp lit.”

“Bank the fire with ashes,” Erica said, resourcefully. “And we can blow out the lamp. Hurry up, you two, or I go without you.”

Five minutes later they were out in the cold, moon-flooded quiet of Orange Street. They walked in the middle of the deserted road, arms linked, whistling softly under their breaths. Erica’s spirits had soared suddenly and unaccountably as high as Tommy’s for this night at least, and Lis was always willing enough to share their moods, in his own contained, level-headed fashion.

Then, arms still linked, they fell to dancing in long, gliding skating steps, weaving from side to side of the road, spirits mounting hilariously with the exercise and the heady autumn air, that tonight smelled again of sea salt and the spicy scent of sweet-fern and bayberry. Finally, breathless with laughter, they swung about the corner into Main Street, and sobered to a more decorous gait.

“Aunt Charity will never,” Erica panted, “make a perfect lady of me. I love to move about, and run and shout and do things too much. Oh-h-h! there’s the Narwhal now! Doesn’t she look like a pirate ship, just as I said?”

They had reached the wharf, and stood gazing out at the dark harbor water, across which a broad golden pathway stretched from the Coatue shore almost to their feet. The moon itself, a huge round disk of orange, like a Chinese lantern, hung low in the sky, and it seemed to the three rapt children that the whole atmosphere about them was shot through with a fine golden mist that rose partly from the path of gold on the water, and partly dropped, curtain-like, from the moon above it.

“Oh, Tommy, think of how that moon’ll look at sea!” Erica cried, softly, clutching his sleeve with a new big lump in her throat. “If only I’d been a boy, you and Lis and I could have shipped together, and gone adventuring like those friends in that book in your mother’s library—The Three Musketeers.”

“Better not let Aunt Charity know you’ve read that book,” Tommy adjured her, wisely ignoring the little traitorous break in Erica’s voice. Of course Erica wasn’t the kind of girl who spilled tears all over the place, but then, as Tommy philosophised to himself, you never could be sure about a girl—even the most sensible of them surprised you once in a while.

“I hate this being always told ‘Don’t do this,’ ‘Don’t read that,’ or ‘Don’t say the other thing,’” Erica burst out, rebelliously. It was an old grievance. “There’s so little that’s really ladylike for a girl to do.”

“Listen,” Lis broke in, lifting an emphatic hand for silence. “It sounded like somebody calling ‘Help.’ Didn’t either of you hear it?”

Straining their ears, Tommy and Erica listened, and faintly but very distinctly there came to all three the sound repeated. There was no doubt this time about its being a cry of distress, and it appeared to come, alarmingly, from the water somewhere off the wharf’s end.

“Some one’s fallen overboard,” Tommy shouted, excitedly. And tearing off cap and coat with a single jerk, tossed these cumbering articles of apparel aside and raced down the dock in the direction of the cry. Lister and Erica were only a step or two behind him, but not near enough to hold him back from the reckless project he so obviously had in mind. Reaching the edge of the wharf, he mounted in one agile leap to the heavy timbering at the side and, lifting both arms above his head, dove into the blackness below.

Erica’s cry of frightened protest rang out simultaneously with Tommy’s dive, and the next moment both Lister and she were standing on the edge of the wharf, staring anxiously down at the choppy little waves raised by the wind’s violence.

The side of the wharf Tommy had dived from was that away from the moon, and until the eyes of the two up above grew accustomed to the darkness, they could make out nothing. Then, gradually, they could see the white outline of the little wave-crests and the blacker hollows between, and last of all a moving, dark object that looked like a head swimming very slowly back toward the dock.

“Tommy!” Erica called, urgently. “Tommy, is that you? Can you make the ladder—it’s right beside you—or do you want us to find a rope?”

“I’ve got a man here,” came Tommy’s voice, slightly muffled by a too inquisitive wave that hit him squarely on the mouth as he opened it to answer. “He’s either dead or unconscious. There—I’ve hold of the ladder now. I can keep us both afloat till you get help. He’s too heavy for Rick and you, and I can’t do much toward lifting him. Hit something when I dived, and hurt my knee.”

“Here comes some one now,” Lister cried in relief. “Hang on a minute longer, Tommy, and we’ll have you out.” Both Erica and he raised their voices in vociferous shouts to attract the attention of the two figures he had noticed farther up the wharf.

“Aye, aye, there! Coming!” a hearty bass voice responded, and the still night echoed to the clumping of heavy boots hurrying along the wharf planking. The events of the next few minutes moved so fast for Erica that afterward she never could quite fill in, by the aid of memory, what actually happened between the time Lis and she called and that when they stood on the wharf, looking down at the inert, drenched figure of a strange sailor stretched out on the ground, and at Tommy slumped back, curiously white and limp, but conscious, in the arms of a burly man whom she now recognized as Captain Joy himself, master of the Narwhal.

“Is—is he dead?” she asked, fearfully, pointing a shaking hand at the stranger.

The man with Captain Joy, who had been bending over the sailor, glanced up, shaking a disgusted head. He was Mr. Stebbins, Captain Joy’s mate, Erica saw. How very, very lucky for Tommy, and for all of them, that the captain and Mr. Stebbins had decided to stroll down to the wharf also, for a good-night look at their ship.

“He—looks so awfully dead,” Erica insisted.

“Not he. No thanks to himself, though, that he ain’t,” the mate growled. “He’s been celebratin’ our last night ashore, and likely enough just walked plumb off the end of the wharf here, without knowin’ he was headed for Davy Jones’s locker.” He added, apologetically: “He ain’t one of our Nantucket lads. He’s a new hand—a furriner we shipped on the Cape, last voyage. You jus’ leave him to me, missy, an’ don’t worry. I’ll see he gits out to the Narwhal an’ into his bunk; an’ in the mornin’ I surely aim to give him a talkin’ to that’ll turn his hair plumb gray—leastways, if he’s any sense of the danger he’s been in this night.”

“And Tommy’s hurt his knee,” Erica went on, anxiously, reassured as to the stranger’s fate. “Captain Joy, you have to doctor men on your cruises. Can’t you look at it and see how bad it is, please?”

The boy winced once or twice, in spite of his most herculean attempts at stoicism, as the captain’s big hands gently prodded his leg here and there.

“It—it feels like it was broken,” Tommy hazarded, his hands clenched into tense fists at his side.

Captain Joy nodded. “Not much doubt about that, my lad,” he said, cheerfully. “But a broken bone’s nothing at your age. Splints an’ rest’ll set that all shipshape again in a matter of a couple o’ months at most.”

”Months!” Tommy gasped, and his head collapsed weakly against Lis’s shoulder, which happened to be nearest. “But, Captain, I’m shipping on the Flying Spray, bound out for Canton, come Saturday.”

Tommy was carried home from the wharf, a decidedly white-faced and subdued Tommy, and laid on the big four-poster in the room Lis and he shared at the back of the house, while his mother was summoned from Miss Charity’s party and the doctor routed out of a peaceful, before-bedtime nap in his study farther up Orange Street.

Captain Bartlet escorted Mrs. Folger across the garden, and went upstairs with her to see his cabin boy. He was full of a bluff, kindly sympathy, and sat on the edge of the bed, letting poor Tommy grip hard at his big, muscular arm, while Dr. Spencer set the broken leg.

The first thing Tommy said, when that operation was over and he was lying back on the stiff white bolster, with his right leg swollen to an unrecognizable size by splints and bandages, was: “I guess this discharges me from sea duty, sir—for this voyage, anyhow. Will you take Lis in my place, please? He was just as anxious to ship as I was, you know.”

The captain looked keenly at the boy, and then at Lis, who had flushed suddenly scarlet.

“Want to take thy brother’s place, son?” he asked the latter. “I’m sorry about Tom’s accident, but I do need a cabin boy.” He added, smiling, “And, after all, I don’t know as I could tell thee from him in any case, so I won’t realize there’s been an exchange.”

Lis gulped, stared rather piteously at Tommy, and then at his mother. His heart had leaped at the unlooked-for opportunity that had come to him, but he plainly hated to accept it at the price of Tommy’s disappointment.

“You’ll be able to ship with Uncle Eric, Tom, when the Sea Gull comes in,” he suggested.

But Tommy shook his fair head decidedly. “Too far off. We don’t know just when the Sea Gull will return. No, this is your chance, Lis; better take it. And we can’t disappoint Captain Bartlet, either. He needs a boy, and this won’t be giving him fair notice to find another. He’ll go, sir,” he told the captain. “And he’s a lot steadier than I am, sir, so you’re getting a better man.”

“Tommy is right—you had better go, dear,” Mrs. Folger said, unexpectedly. “I know you have wanted to, all the time, and I was pleased by the way you kept your disappointment to yourself and did not spoil your brother’s pleasure by grumbling.”

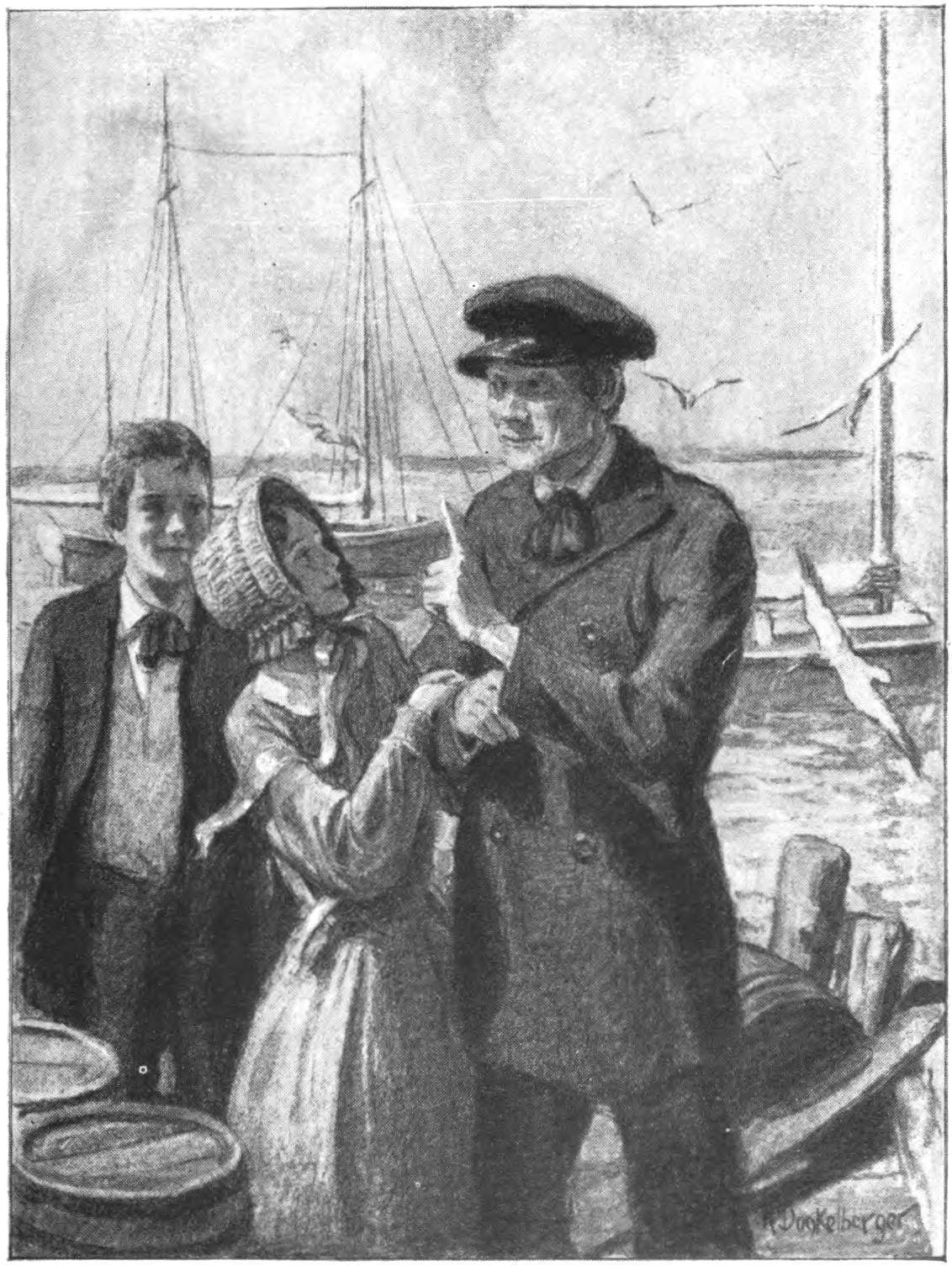

So Captain Bartlet signed on another cabin boy, and arrangements were made for Lis to join the ship in Boston, the night before her sailing. He was to leave Nantucket on a fishing-boat belonging to a neighbor of theirs, another Captain Joy—brother to the Narwhal’s master—which was bound for Boston at the end of the week, with a cargo of fish for the city markets. Captain Bartlet himself, was going on the morrow, but Lis would need a few days to get his sea-going outfit together, before starting out in his new life.

The next four days before his departure were busy ones in the two Folger households. Miss Charity brought her sewing basket over to her sister-in-law’s, and helped in the work of altering such things as had been already purchased for Tommy, to Lister’s use. Though the two boys were so alike that strangers were constantly taking one for the other, Tommy was slightly broader in the shoulders than his twin—just enough difference to make certain takings-in necessary in fitting the clothes of one to the other.

Erica would have been pressed into service also, but her clumsiness with her needle was too well known to both aunts to make her help desirable. As Miss Charity phrased it in exasperation, she only “made double work when she put on a thimble. It took one person to rip out her stitches, and a second to replace them properly.”

Miss Charity had labored long and hard with this hoydenish young niece who was so mortifyingly unlike the other girls of her age and community. She even felt dimly that in some way it reflected unfavorably upon herself, that she could not, no matter how diligently she tried, teach her charge to be a “little lady” like the daughters of her island neighbors.

But in another way Erica managed to be of very real help, by constituting herself nurse and general entertainer for Tommy, and thus setting his mother free for more immediate duties. Tommy was finding it pretty hard to lie there in bed, day after day, unable to move his trussed-up leg or even to turn over without assistance. He had never been fond of reading, and now books seemed a rather contemptible substitute to offer an energetic, lively boy, for the glorious adventure of that lost voyage to China, in the Spray. Still, he graciously allowed Erica to read aloud to him on occasions, when her inventive faculty at devising other amusements ran temporarily dry. But the books of that period intended for boys, which could be found in either of the Folger houses, were such very mild, unexciting narratives, that the readings usually ended in both Erica’s and Tommy’s yawning desperately together and flinging the disappointing volume aside.

The only subjects that really interested the latter at this period dealt with nautical matters, and when Erica realized this she ransacked the libraries of all Miss Charity’s friends, to find old ships’ logs and journals of exploration which she could borrow. As Nantucketers have always been great travelers, almost every house in town proved to have some tale or other to offer, often containing the adventures of a seafaring ancestor, and the quaint language they were told in sent the young Folgers into peals of hilarious laughter.

Lis joined these reading sessions whenever he could, but his mother and aunt kept him busy undergoing tedious fittings, aiding them in checking and rechecking lists of his various needs for the voyage, and performing the usual household duties such as wood-chopping, fire-making, and the carrying of heavy pails, which formerly Tommy and he had divided between them. Mrs. Folger had arranged with young Martin Joy, two doors away, to do these chores until Tommy’s broken bones had mended, but he was not to enter on his duties until Lis had departed.

Instinctively, Erica tried to keep herself so busy that she should have no time left for remembering the change that was to break up the familiar threefold companionship shortly. But hard as it was on her, she guessed that it was going to be harder still for Tommy. The twins had never been separated for more than a few hours at a time, and Lis had always been the steady, self-reliant one on whom both Tommy and Erica herself unconsciously leaned. The latter two were more alike, bubbling over with high spirits, impetuous, apt to act on the moment’s enthusiasm, and they had come to feel it was Lister’s natural province to extricate them from the scrapes their own heedlessness led them into, and to provide a sort of moral balance wheel generally.

It was going to be queer, Erica reflected, sadly, going on with the old, everyday life, in the old, everyday surroundings, with no Lis. In fact, it was going to be worse than queer—it was going to be a pretty heart-breaking business.

The night before Lister’s sailing, Tommy took the jade seal ring from where it still hung about his own neck on the knotted Chinese cord and put it around his brother’s. “Be sure you look old Sun Li up for Rick and me,” he said. “Then remember every last thing about him—who he is, where he lives (better see the inside of his house if you can, so you’ll be able to describe it), and tell us all about it when the Spray comes home.”

Erica and both her aunts went down to the wharf the next afternoon, and saw Lis aboard Captain Joy’s sloop, which was to take him to Boston. They all kissed him good-by, and Aunt Callie cried a little because, just at the end, she simply couldn’t help it, and Lis’s own voice was more than a bit husky in the final exchange of last words, and promises to write if there should be a chance to send a letter back by another ship.

His mother and Miss Charity stayed on the wharf, continuing to wave their handkerchiefs until the sloop was so far out that she looked like a toy ship on the smooth, blue water. But Erica slipped away from them as soon as she was sure Lis could not see them any longer, and walked very fast up the beach to a point where she would be out of sight of houses and people, and there she sat herself disconsolately down on the warm, yellow sand, and told herself she wasn’t going to cry, not for anything in the world—and promptly contradicted her brave assertion by doing it.

However, being Erica, the tears didn’t last long, and at the end of the little fit of crying she sat up and wiped them away briskly, feeling better for the outburst, yet rather ashamed of herself, too.

“Now I’ll go back to Tommy,” she said aloud, addressing an inquisitive tern which had hovered a second or two overhead, on quickly-beating slim white wings, cocking its bright eyes down at this strange human in a brown plaid dress who sat huddled on the sand, and made funny, choking sounds that, even to a tern’s ears seemed to hold a note of distress. “Tommy’ll be feeling pretty bad, too,” Erica continued to address the tern, and then, as it darted away with a farewell flirt of its wings, she added with a little burst of admiration: “Oh, you beautiful, beautiful thing! If I can’t be a boy and go to sea, the next choice would be a tern or a great gray gull, so I could swoop about over the water all day long, fishing and enjoying myself, just as you do.”

She walked home slowly, close to the water’s edge, where the sand was wet and firm. There was usually a surf on the island’s south shore, but here on the north beach there were scarcely ever more than ripples coming in, and on that day the clear green water beat in softly against the dark sand like the pattering of fairy hand-clapping. Looking down into it, Erica could make out scores of small hermit crabs moving clumsily about in search of their midday dinners, dragging their big shell houses on their backs; and the more agile spider crabs crawling along the bottom among them, likewise intent on the serious question of food.

Erica loved all the quaint little sea creatures she had come to know on her beach walks, as well as the terns and the big gray herring gulls which arrived about this time each year, after the smaller, laughing-gulls of the summer had migrated farther south. The autumn was a wonderful season for seeing strange birds, that stopped a day or two on Nantucket to break their long, migratory flights to warmer climes.

The wild ducks had been passing over the island for more than ten days, now, and sometimes, in their tramps over the sweet-scented commons, the twins and Erica would come upon a small, jewel-like pond set down in a rosy sedge of reeds, and on its blue surface there would be stragglers from one of the big flocks, swimming up and down placidly, and perhaps wondering, in whatever thoughts a duck knows, whether this pleasant, fertile island might not be as happy hunting-grounds as any they would be likely to find farther south.

A little later, the long V-shaped wedges of the wild geese’s flight would be seen, usually late at night or very early in the morning, high up against the blue Nantucket sky. Erica, when she saw them, always waved to them enviously, and wished she were a wild goose, too—just as she often wished she were a boy, or a gull, or anything that was untrammeled and free, and the opposite of what proper little girls of her day and generation were supposed to be.

It was almost dark when she reached home and slipped through the side garden to Tommy’s house and up the broad, white-painted front stairs. Aunt Callie called to her, in a rather woe-begone voice, and bade her go in and talk to her cousin, who had had a lonely day and had been suffering a good deal, besides, with his leg.

The door to the back room which was Lis’s and Tommy’s stood ajar, but the lamp inside had not been lighted yet. Standing on the sill, Erica spoke Tommy’s name, but softly, in case he were asleep.

“Come in,” a muffled voice answered her, not too graciously.

Erica went in, and crossed the dim room to the big mahogany four-poster. Tommy had slid down uncomfortably in bed, the pillows bunched askew under his yellow head, which looked more wildly disheveled and moplike than usual. The covers were drawn up so that they half covered his face, and even in the dusk Erica could see that his cheeks were hot and flushed and that his forehead was puckered with a forlorn, childlike scowl of utter misery.

“Here, let me plump your pillows up nice and comfy,” she said, capably, and proceeded to lift his head with one strong, gentle arm and turn the hot and crumpled pillows with her free hand. For Erica had at least one womanly accomplishment—she was a good nurse in a sick-room, and was never more contented than when one of her family or neighbors borrowed her services.

Tommy neither demurred nor accepted her help, but as she turned the top pillow Erica’s fingers encountered a big, round wet spot just where the boy’s flushed face had been pressed when she entered. She made no comment, but she was suddenly conscious of that uncomfortable lump in her own throat once more. Tommy never knew she had discovered that he had been shedding a few bitter tears alone in the dark. It was probably partly homesickness for his twin, rebellion against lying there like a log, helpless and in pain, and a sudden break-down of the barriers he had built so pluckily about his disappointment.

Remembering her own crying-spell down on the beach that afternoon, Erica shrewdly suspected that Tommy would feel the better for giving way—as long as he never discovered that anyone knew of it. She finished beating his pillows, pulled up more smoothly the soft, hand-woven woolen blankets on the bed, and, going over to the table, lighted the lamp.

Aunt Callie appeared in the doorway just as she finished the last of her tasks. Mrs. Folger’s thin face was paler than usual, and her eyes, blinking a little in the yellow lamplight, had pink rims about them as if she too, had been crying; but her lips were smiling.

“I told Aunt Charity that I meant to keep you for supper, Erica,” she observed. “Tommy and I need you tonight. And I thought,” she went on, still determinedly cheerful, “that if you’d help me, my dear, we might all have our suppers up here on this table by Tommy’s bed. I’ve got fresh gingerbread, and I’m going to fry a chicken. I had Mart Joy kill one of the young roosters this morning. Will you children have chocolate to drink, instead of milk? It’s no trouble at all to make a pot.”

At fifteen the prospect of a good supper has a magically cheering effect. Both the girl’s and boy’s faces brightened perceptibly.

“Chocolate, please, ma’am,” Tommy elected.

The weeks it took for Tommy’s broken bones to mend were a trying period, not only for Tommy himself, but for his mother and Erica as well. The boy tried valiantly to be patient, but he had never stayed in bed a day in his active young life before, and as the days grew into weeks it seemed to him that he could not bear the terrible inaction and monotony another hour. Then, in spite of his best efforts, he would snap at everyone about him, refuse to be pleased with Erica’s hard-working efforts to entertain him, and behave--as he would admit shamefacedly when the grumpy fit had passed--like a spoiled baby generally.

Even Erica grew a little pale and peaked toward the end of Tommy’s convalescence, missing the outdoor life she was used to, but steadily refusing to desert her patient, who came to depend more and more on her as the days passed. Mrs. Folger could not be in the sickroom always, as she had a dozen household duties which must be seen to every hour of the day, and Miss Charity, though she came over when she could, was likewise engaged with her own housekeeping.

The latter insisted that Erica should take at least one brisk walk each day, and of course there was school in the mornings, which could not be given up even for the duties of a nurse. Formerly, Erica had often gone home for early dinner with one of the girls in her class, when the morning session was over—Molly Macy, over on Pearl Street, or perhaps pretty Sara Anne Gardener, who fulfilled all Aunt Charity’s requirements for being a “genteel little lady,” yet managed to be a pleasant enough companion for a few hours “when nothing more exciting offered”—as naughty Erica used to explain to the twins.

But since Tommy’s accident Erica had refused all these invitations, and hurried home to retail a carefully-remembered account of the morning’s events to his envious ears. Tommy felt that, as he had been so unfairly deprived of his exciting sea adventure, it was decidedly hard that he must fall behind his class in school, as well. Erica offered to ask the teacher to assign him some home work, which she could bring back with her each day, but Tommy was not the student Lis had been, and the idea of studying alone, without anyone to explain problems and help him over hard places, did not appeal to him, and the idea was abandoned.

Another factor which served to make both the boy and girl more rebellious against the indoor confinement was that that fall was a particularly fine and sunshiny one on Nantucket. The autumn colors blazed splendidly on the commons; seas and skies were a thrilling and cloudless blue, and the crisp air caused the blood to race faster, and stored up a daily-renewed fund of unspent energy that made a shut-in existence torture to the two active young people.

After the first three weeks, Tommy was allowed to be up and dressed and to go about the house, and even for a few stumping blocks along Orange Street on his new crutches. But that seemed, somehow, only an aggravation to a boy who wanted to run, play ball, tramp the commons, and take up his familiar every-day life along its usual lines. At length, however, what Tommy called bitterly his “term in prison” drew to an end, as most things, both pleasant and unpleasant, have a way of doing. And his final release from the hated crutches coincided with the near approach of Christmas, always a specially festive time on Nantucket.

To be sure, this year Christmas could not be quite like all the other happy Christmases in the two Folger households without Lis—Lis who would be having his Christmas at sea, more than two-thirds of the distance to Canton.

On the road to Surfside on the south shore of Nantucket there was a stretch of low pine woods where the twins and Erica had been in the habit of foraging each year for their Christmas trees. The wind swept over the island with such constant violence that it stunted even the pines growing on the commons. They looked like trees in Japanese prints, little and twisted, with writhing branches stretching out away from the blast. Where the pines were massed closely together, however, as in these woody patches, they were straighter, less tortured by sea winds, though even there they were dwarf trees.

Erica had always loved the clean, pungent fragrance of that pine woods, and she delighted in the gray-feathered, short-eared owls, with their wise little cat faces and stealthy mothlike flight, who lived in the green dimness of its piny aisles. Sometimes on a walk she had started up more than a dozen of the creatures in a single afternoon. And in spite of Lis’s and Tommy’s loud-voiced amusement, she had named that particular stretch of woods on the Surfside road, the “Owls’ Country.”

She used to wonder, whimsically, whether the owls ever guessed that the twins and she robbed their country of two of the biggest and branchiest trees each December, to hang their Christmas packages and candles on. And whether that would serve as an excuse for breaking into the quiet of the grove, and putting the owls to the trouble of removing their stately selves from one tree to another. Sometimes the owls scolded noisily when they were disturbed, and always they stared down their curved, horny beaks superciliously at the intruders, from a safe distance.

Lis was not here to go tree-hunting this year, and partly because Erica felt instinctively that Tommy and she would miss him more if there were only two of them, partly because Tommy’s reknit leg was not yet quite up to all the demands such an expedition would put upon it, she suggested making a party of the occasion and including half a dozen or more young folks. So Mollie Macy and her brothers, Jud and Alex, were invited to join them, with Martin and Lilla Joy, the two fat Covington boys, and Sara Anne Gardener.

The day before Christmas, Tommy harnessed his mother’s sedate brown mare, Polly, to the ancient springless cart that was used for hauling barrels of flour and apples from market, and for bringing in loads of potatoes, garden truck, and fragrant summer hay from the Folger farm out Madaket way. This farm belonged to Miss Charity, Mrs. Callie Folger and Captain Eric jointly, and was managed for them by a capable farmer named Amos Brett.

Tommy drove, since his leg was not strong enough for long walks, and the girls bundled into the cart behind him, sitting on a pile of hay spread out on the bare floor-boards. The other boys tramped alongside, finding no difficulty in keeping up with old Polly’s sober pace.

Miss Charity put a generously filled lunch basket in the cart just as it started, containing cold fried chicken, thick slices of homemade brown bread, still warm from the oven, red apples, crisp brown doughnuts, and a stone jug of sweet cider. Miss Charity was justly proud of her fame as a good cook and provider, and, knowing that Tommy and Erica had had very little pleasure that fall, she had taken particular pains to make the present party one to be remembered.

The cavalcade of young people started out of town in high spirits, and headed for Surfside and Erica’s “Owls’ Country” by one of the sandy rut roads that wound across the commons. It is usually fairly mild on Nantucket until January, and on a sunny day the commons will be almost warm in the hollows around noon. That day was no exception to the general rule. The sun shone down in a hot blaze of gold, and though the wind, when it came, left a nip and tingle in its passing, down in a certain deep depression Erica and Tommy selected for their picnic site near the pine woods the party was quite protected from the blasts.

The ground was carpeted to the depth of a foot or more with dried but still faintly colorful huckleberry vines, with here and there patches of sweet-fern, mealy plum, and soft clumps of the gray Iceland moss. An old blanket was spread out to serve as table and tablecloth in one, and the basket and stone jug were set in the place of honor in the center.

The eight hungry girls and boys sat about the edge of the blanket, and Erica unpacked the basket. Everybody’s appetite had been sharpened to extra keenness by their morning in the crisp December air, and they speedily made ravenous inroads on the tempting fare Miss Charity had provided. But since the business of tree-choosing and chopping was still ahead of them, no one lingered longer than necessary over the meal.

When everything had been neatly replaced in the basket, four shining, newly whetted axes were brought out of the hay on the floor of the cart, and, leaving old Polly to follow at her leisure, the boys and girls hurried on to the woods.

Choosing just the right size and shape always took time; and this year there were not two Christmas trees to be selected, but three, since the young Joys also wanted one for their holiday celebration. The rest of the children were willing enough to lend a hand in the work of cutting down the trees and to offer unsought advice as to the relative merits and failures of the pines finally chosen.

So it was not surprising that the business in hand took most of the short afternoon, and that the expedition should be overtaken by sunset and the soft, smoky purple twilight of early winter, before they had covered half the distance back to town.

They hurried a little faster then, prodding the indignant Polly to greater exertions—not because any of them was afraid of darkness on the familiar commons, but because this was Christmas Eve and there was much to do at home. Later, bands of carol-singers would go from house to house through the town, singing under their neighbors’ windows, and in each window lighted candles would blaze an answering greeting to them across the friendly dark of Christmas Eve.

Lilla Joy pointed toward the northwest, where a low, heavy-looking cloud had risen over the horizon soon after sunset.

“That’s a real snow cloud,” she insisted. “We’ll have a white Christmas, after all.”

“I’m glad,” Erica sighed happily, leaning back in the hay and drawing her woolly red cape about her more tightly, for the wind was decidedly sharp now. Her cheeks burned red from the cold and the day’s exertions, and her eyes, which were the exact shade of the harbor water when the sky was cloudless, shone starrily. She loved Christmas—loved it; every sweet old custom from choosing and bringing home the tree to trimming it with tinsel balls, gilt paper cornucopias, and bunches of gay red holly; and later still, the hanging up of the long, limp stockings over the mantel in the parlor. Last of all, there was the little ceremony of lighting the Christmas candles in all the front windows, upstairs and down.

Snuggled down cozily in the warm hay, Erica shivered excitedly and began to sing, very softly at first, that most beautiful of all the sweet old Christmas songs:

Her voice lifted a little, joyously, with the second line, and one by one the other children took it up and sang with her, the fresh, happy voices ringing out clearly in the dusk. And so, still singing, they walked and drove into town just as lights began to be lighted in the houses along Orange Street, and a few hardy stars came out overhead through the gathering snow clouds and twinkled down in benediction, as they must have twinkled over a far-away land across the seas, twenty centuries ago, on a group of young shepherds who also came, singing, to celebrate that first Christmas of all.

“Father’s boat was to get in today,” Lilla Joy declared as they dropped Mart and herself at their door. “He promised he’d be home for Christmas. I wonder what he’s brought from Boston.”

“Passengers, for one thing,” Mart laughed. “He was going to bring some cousins of the Gardeners’ over to spend the holidays—off-islanders, you know. I wish’t it was Lis who was coming,” he added, awkwardly. “Doesn’t seem just right to have Christmas without him, does it, Erica?”

Erica put out her hand impulsively and clasped his strong, calloused palm with sudden gratitude. “Thank you, Mart,” she said, softly. “No, it—it seems sort of—all wrong.”

When the others had been left at their several homes, Tommy helped Erica drag her tree into the house and set it up in the usual place between the hearth and the north window. Then, without waiting to trim it, the cousins went across the garden, dragging the last tree between them.

A sound of voices in the sitting room made them stop in the hall of the other house and peep in at the open door. Aunt Callie was seated in her big rocker by the hearth, with Aunt Charity opposite her, and between them, in chairs drawn comfortably up to the red glow of the coals, sat a fair, ruddy-cheeked young man with an unmistakably seafaring air about him, and a slender girl about Erica’s own age, dressed in black.

The girl’s face was pale in the firelight, and so thin the features looked oddly pinched and sharp. Her forehead was puckered in three fine, vertical lines that gave her a fretful, unhappy expression.

At Mrs. Folger’s feet—where the two at the door had not seen her in this first glance—a pretty little girl of three or four sat on a low hassock, one plump, rosy cheek pressed confidingly against Aunt Callie’s knee. The child’s hair, which clustered in tight, bronze-colored curls over her charming little head, reflected the firelight in warm splashes of reddish gold with each move she made, and now, at some sound from the hall, she turned a blue-eyed, baby smile that way.

Mrs. Folger called: “Tommy! Erica! Is that you, dears?”

They came in then, dragging the bushy pine tree, and the curly-haired baby uttered a little shriek of delight at sight of it.

“Clistmus t’ee!” she shouted, gleefully. “Barbee’s Clistmus t’ee. All for Barbee!”

Mrs. Folger addressed the young man with the seafaring look about him, who had risen politely at Erica’s entrance.

“Bernard, this is my niece, Erica Folger—you remember Captain Eric, of course. And my son Tom. Children, this is a cousin of mine, Mr. Bernard Gatchel, whom I have not laid eyes on since my marriage. He came to Nantucket today on Captain Joy’s sloop, on a sad errand.” She hesitated, and laid a gentle hand on the thin, fretful girl’s dark hair.

“These are his sister’s children—Mildred and Barbara Thorne. Their mother and I went to school together in Boston.” Mrs. Folger had not been a Nantucket girl. “Besides being second cousins, we were very close friends and loved one another dearly. Tommy has certainly heard me talk of Cousin Jane Thorne.”

The boy nodded bewilderedly, and then smiled in answer to a flash of small white teeth between Barbee’s parted lips.

“Cousin Jane died a month ago,” Mrs. Folger said. “So this is not a happy Christmas for my poor Milly.” Again that motherly touch on the dark hair; but there was no lighting or softening of the fretful face below it, and Erica, looking on, was conscious of a resentful sense of vicarious rebuff.

“Their father died more than two years ago,” Mrs. Folger wound up her explanation and introduction in one, “and Cousin Bernard here, being mate on a packet that sails out of New York next week, cannot, of course, take charge of Mildred and little Barbee. And Cousin Jane had asked him, before she died, to bring them to me. She knew her babies would be as welcome as my own.”

“You mean,” Tommy asked, startled into unconsidered speech, “that they’re going to—to live here, mother?”

Even as the words escaped him he realized their inhospitable import, and bit his lip, coloring miserably. But—a strange girl in the house—that cunning baby, Barbee, didn’t count, of course—eternally underfoot, making a fellow stay constantly on his company behavior!

The object of his uncomplimentary thoughts turned to stare at him around the back of her chair, her eyes looking enormously big and black in her white, sulky face, and the boy thought he saw in them a malicious enjoyment of his confusion.

“Thank you, sir,” she said, clearly and too sweetly. “Yes, I believe Barbee and I are going to live here. Your mother has very kindly asked us to stay.”

The black eyes passed on to Erica, and stared at her with a keenness that seemed to miss no smallest detail of her appearance.

“Do you live here, too?” the dark girl asked then, fretfully, tapping the toe of her black shoe on the brass andiron nearest her.

“No, I live next door, with Aunt Charity,” Erica said, politely, feeling inwardly guilty because she was so glad she was not to live in the same house with this sulky, unattractive stranger. Feeling, too, tremendously sorry for poor Tommy, who had exchanged the daily companionship of Lis for Milly Thorne.

She had a swift, dismayed vision of the change from the old, happy existence Lis, Tommy, and she had known, which the coming of Mildred and Barbee Thorne would mean. Then the sight of Milly’s black dress softened her to shamed remorse.

“And here I was thinking about Tommy’s and my Christmas being spoiled,” she scolded herself, silently. “Erica Folger, you deserve just no Christmas at all!”

It was a white Christmas day, after all. During the night it had snowed hard and steadily, but the snow ceased just before dawn, and Nantucketers woke to a Christmas morning of blue skies and golden sunshine over a white-carpeted island.

The two windows of Erica’s room faced toward the harbor below, and with the first slim fingers of sunlight poked in at all the small panes she was awake in her big mahogany bed with the pineapple posts. She lay there blinking drowsily at the light, until she noticed the thin rim of snow on the sill of her opened window. Then she sprang out of bed, shivering, for the room was bitterly cold, and pattered on bare feet across the wide, painted boards of the floor.

Shutting the window energetically, she stood there a moment looking out on a new and shining white world.

“It’s cold enough for skating, too,” she told herself, drawing her high-necked flannel night dress closer about her. The boys would clear some of the snow on Long Pond, or Hummock, as they did each year with the first snowfall, and that afternoon—She stopped, her breath quickening.

“Why—why, it’s Christmas morning!” she exclaimed, astonished that she could have forgotten even for that brief, half-waking interval. “A white Christmas, just like Lilla Joy said it would be.”

Her thoughts flew, by a natural kinship of ideas, from Christmas snow to Christmas trees and stockings. Every Christmas, as far back as she could remember, Erica had gathered up her unexplored and bulging stocking and an armful of packages, and gone across the garden to her cousins’ house, to have the added fun of sharing surprises with Tommy and Lis.

This year there would be only Tommy to open bundles with, but—— She stopped abruptly for the second time since waking that morning, as memory gave her another little reminding nudge. The bright face clouded. There wouldn’t be only Tommy this morning. She had completely forgotten Milly and Barbee Thorne.

“But I’m not going to start Christmas by taking silly dislikes and judging folks unkindly,” Erica decided, sturdily. “As Aunt Callie said last night, it’s not going to be a happy Christmas for Milly this year, without her mother.”

She began to pull on her clothes rapidly, still shivering a little, for she was in far too much of a hurry to stop and light the fire which was laid on the broad hearth, ready at the touch of a match to send a comforting golden flame chimneyward.

When she was dressed, she took her woolly red cape from the deep wardrobe and wrapped herself in it, drawing the gathered hood over her tumbled red curls. She looked, with her eager young head cocked alertly on one side, her bright eyes, and the red of her cloak, not unlike an energetic robin redbreast defying snow and cold, in search of an early breakfast worm.

Downstairs she paused in the parlor long enough to admire anew the glistening tree she and Aunt Charity had dressed late last night, and then snatching the fat white stocking hanging from the blackened oak mantel, she tucked it under her cape, with one arm, and with her other retrieved an exciting pile of various sized packages laid out on the end of the sofa, where her particular share of Christmas was always put. The next moment she was out the side door, the sharp wind stinging fresh roses into her already glowing cheeks, and turning the tip of her straight little nose a matching pink.

The snow had not been swept from the porch yet, as the elderly Portuguese, who did the numerous outdoor chores about the place, had not made his appearance at this hour. Fortunately the snow was powdery and dry, for Erica was far too excited to remember such practical things as rubber boots, and dashed across the white garden, arriving, bright-eyed and panting, at her aunt’s side door, just as Tommy, who had watched her approach, opened it to admit her.

The boy put a finger to his lips, grinning, and jerked his head stairward. “Nobody else is awake yet, I guess,” he explained. “Come on in where the tree is, and I’ll light the fire.”

“We picked two good trees yesterday,” Erica observed judicially, watching him light the paper under the kindling, and blow gently to keep the slender flame going. Then her eyes filled suddenly and quite unexpectedly, so that she turned to inspect the tree with great attention, until she had managed to wipe the tell-tale drops away with the back of her hand.

It had come upon her with a force that brought a choking lump into her throat, how much they missed Lis at this familiar Christmas-morning ceremony. It had always been Lis who waked early enough to have the fire roaring hotly before Erica and her stocking appeared. Tommy, struggling with cold and awkward fingers to repair his forgetfulness, was all at once a pathetic figure.

He fumbled so long about getting the fire burning that she wondered, unhappily, if perhaps he, too, were not trying to avoid her glance. She was sure of it a moment later, when he sat back on his heels, muttering under his breath something about smoke getting in his eyes.

But neither of them spoke of what both were feeling, and a moment later they were seated on the carpeted floor before the hearth, their filled stockings on their laps, and opened and unopened packages strewn about them.

But as swiftly as their fingers flew in unwrapping the presents, their unwonted mood of gravity slipped into the normal, joyous excitement of Christmas morning. At last, having examined everything and found it eminently satisfactory, they bundled the wrapping paper into the blaze, and sat contentedly silent for a while, munching sweets from the now empty stockings.

“Christmas must be sort of—funny at sea,” Erica declared, finally, out of that unusual silence.

“Yea-ah,” Tommy’s mouth was uncomfortably full for articulate speech. “Guess Lis’ll be thinking ‘bout us, right this minute.” He sighed. “Wish I could have gone, too, Rick.”

Erica made a face. “And left me here high and dry by myself. No thank you.”

Tommy grinned. “Oh, you’d have had Milly Thorne,” he consoled her wickedly.

Erica ignored this flippancy, and returned to her contemplation of the fire. “I think Christmas at sea might be—rather beautiful, too,” she said, slowly, not looking around. “I love the ocean, Tom. I guess maybe it’s because I was born at sea that I’ve always sort of felt I belong to it. You know,” she added more briskly, “how Sun Li always addresses the presents he sends me home by father, ‘To my Honorable God-daughter, the little Sea Girl’—I love that for a name.”

Tommy grunted. He privately thought it rather flowery and Oriental, but both Lis and he had been carefully respectful on the subject of Sun Li with Erica, ever since one memorable occasion when she had flashed into a towering rage at the age of five, over a bit of teasing on Tommy’s part, and, after flying at the twins like a small wild cat, scratching, biting, and kicking, had wound up with a burst of utterly heart-broken and most unwonted tears. It was the tears that had done more to prevent a repetition of the remarks she objected to, than the temper that had preceded them.

About fifteen minutes later, Aunt Callie and the two visitors arrived downstairs, and Barbee Thorne went into such ecstasies over the trimmed tree and her stuffed stocking, that the moment’s attention was centered entirely about her. Aunt Callie, with her sister-in-law’s help, had hurriedly gotten together some additional gifts for her two new charges at the last minute, so there was a doll for Barbee—a discarded one of Erica’s childish days, redressed by Aunt Charity before she went to bed on Christmas Eve.

The pair of new skates which were to have been Aunt Callie’s present to Erica she had given to Milly instead, and a little note, tucked into Erica’s stocking, explained the exchange, and substituted a string of rose coral beads which Milly Thorne could not have used with the sad little black dresses she was wearing.

Erica was delighted with the corals, though she could not help a small pang of regret for the loss of those beautiful, shining ice skates. Her old pair were almost past sharpening, after years of hard use.

It would have been easier if Milly had only appreciated the skates. She had thanked Mrs. Folger politely, but evinced no enthusiasm at the news, delivered eagerly by Tommy, that Erica and he would take her skating that afternoon on Long Pond.

“I can’t do much skating myself, on account of my leg not being strong enough yet,” he explained. “But we’ll all go out there, and Rick and the Joys will look after you.”

“I don’t know how to skate,” Milly said, in that fretful manner they had resented last evening. “You know, I’ve always lived in the city till now.”

“Oh, we’ll teach you in no time,” Tommy offered, confidentially, though some of that first sparkle of friendly generosity had gone out of his tone under the dampening effect of her lack of responsiveness.

“Mother always said I took cold so easily, she didn’t like me to go out in the snow,” Milly objected, shivering a little. “I think I’d rather stay in here by the fire, with Cousin Callie, if you please. Maybe some other time I’ll feel more like going.”

The words were civil enough, but Tommy and Erica looked at each other blankly. Afraid of taking cold in that brief, infrequent snow so eagerly waited for by the Nantucket children!

But they were too polite—and also too honestly amazed—to voice a further protest, and soon after the long-drawn-out, bountiful Christmas dinner was finished, they took up their skates, harnessed old Polly to the sleigh, and departed for Long Pond, stopping to pile in the young Joys and the Macys on the way.

“I should think,” Tommy observed to his cousin, as he saw her struggling with the worn straps of the old skates at the pond’s edge, “that Milly might have lent her new skates to you, as she won’t use them herself. You know, mother really bought them for you in the first place.”

Erica bit back a sigh, and answered with a heroic effort at absolute fairness: “Well, I was sort of hoping she’d say something about it. But, of course, she doesn’t know they were meant for me, or that my old ones are in such a state.” She surveyed her feet with a rueful air. “I can make these do another year,” she admitted. “It’s only the thought of her not using the others that makes me a little mad.”

“Mother wouldn’t like me to talk about a guest,” Tommy observed, grimly, “but it does seem to me it’s bad enough to have to miss Lis about the house, without——” He didn’t finish his sentence, but Erica put a swift hand on his arm understandingly.

“I know,” she agreed. “It’s going to be harder on you than on me, Tommy. I guess Lis’ll be in Canton in another month now, don’t you? D’you suppose he’ll really meet Sun Li?”

In the interest of the discussion that followed, Milly Thorne and her irritating qualities were forgotten for the time being. It was, therefore, almost as much of a shock to come home that afternoon, flushed with the cold and exercise, and find her sitting by the fire in her black frock, with her fretful young face and sharp, unfriendly black eyes, as it had been the night before when they had first seen her there.

And in the days that followed, neither Tommy nor Erica ever quite lost that first instinctive sense of her being a stranger. It was not that she often did or said anything actively quarrelsome; it was just that she failed utterly to fit into their little circle; so obviously preferring to sit aloof with a book on her lap, but with those strange, unchildlike eyes of hers fixed on the fire instead of the open page before her, that the young Folgers’ efforts to include her in their plans grew more and more half-hearted and perfunctory as time wore on.

Being kind-hearted youngsters, they were honestly sorry for her in her evident unhappiness, and a glance at her black dress was always sufficient to check a too-sharp retort whenever she proved unusually apathetic and aggravating. But friendly relations could not be said to advance appreciably in the household, and Mrs. Folger and Miss Charity, looking on, grew seriously troubled by the situation.