Footnotes have all been renumbered from 1 to 20.

Page 76—bougeoises changed to bourgeoises.

Page 332—biassed changed to biased.

The Advertisements “By Same Author”, have been placed at the back of the project.

From a portrait by A. Burt

Taken in 1836.

MARY RUSSELL MITFORD AND HER SURROUNDINGS

BY

CONSTANCE HILL

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY ELLEN G. HILL AND REPRODUCTIONS OF PORTRAITS

“There are few names which fall with a pleasanter sound upon the ears of those who adopt authors as friends than the name of Mary Russell Mitford.”

LONDON: JOHN LANE, THE BODLEY HEAD NEW YORK: JOHN LANE COMPANY. MCMXX

[iv]

The centre design in the binding represents a French gold enamelled watch which belonged to Mrs. Mitford and was inherited by her daughter. The original is in the possession of the Misses Lovejoy.

WILLIAM BRENDON AND SON, LTD.,

PRINTERS, PLYMOUTH, ENGLAND

[v]

PREFACE

The more we study the life and character of Mary Russell Mitford the more we become attached to her, for we come under the influence of a nature that seems to radiate peace and good-will upon all who surround her.

“The pleasant compelled enjoyment of her tales,” writes Harriet Martineau, “is ascribable no doubt to the flow of good spirits and kindliness that lighted up and warmed everything that her mind produced.” And if we seek for a further reason, surely it is to be found, as another writer observes, “in their strong rural flavour. They breathe the air of the hay-fields and the scent of the hawthorn boughs. There is nothing artificial about them, nothing of the conventional pastoral. They are native and to the manner born.”

Here is an example that occurs in a letter to a friend, written long before her printed works appeared. Speaking of a walk in the Berkshire meadows on a spring morning, she says: “Oh,[vi] how beautiful they were to-day, with all their train of callow goslings, and frisking lambs, and laughing children chasing the butterflies that floated like animated flowers in the air!... How full of fragrance and of melody! It is when walking in such scenes, listening to the mingled notes of a thousand birds and inhaling the mingled perfume of a thousand flowers that I feel the real joy of existence.”

Many writers have imitated Miss Mitford’s style since the “tales” of Our Village first took the reading world by surprise nearly a hundred years ago; but none of those writers, in my opinion, possess her potent charm, nor do they possess her wonderful power of making her readers see nature, as it were, through her eyes and grasp the beauty and poetry of rural life.

Mary as a child was shy and silent before strangers, but withal very observant. Writing of the impressions made upon her mind by some of the French émigré coteries with which she had come in contact, she says: “In truth they formed a motley group [whose] contrasts and combinations were too ludicrous not to strike irresistibly the fancy of an acute observing girl whose perception of the ludicrous was rendered[vii] keener by the invincible shyness which confined the enjoyment entirely to her own breast.”

But is it not to the experiences gained by such quiet, shy children as herself and Charlotte Brontë that we owe much of our knowledge of life and its surroundings? It is the listeners not the talkers that can hand down this knowledge to us.

Miss Mitford’s talents were varied, and we owe to her pen some stirring dramas which were performed with much éclat on the London stage, and in which John Kemble and Macready took the leading parts. The public were astonished to learn that it was a gentle lady living in a remote Berkshire village who was thus moving the great London audiences.

A shrewd American critic of the day remarks: “In all these plays there is strong, vigorous writing—masculine in the free unhashed use of language—but wholly womanly in its purity from coarseness or licence and in the inter-mixture of those incidental touches of softest feeling and finest observation which are peculiar to the gentler sex.”

It has been said of Miss Mitford by one who knew her that “as a letter-writer she has[viii] rarely been surpassed, and that her correspondence, so full as it is of point in allusions, so full of anecdote and of recollections, will be considered among her finest writings.” Even her hasty notes, we are told, “had a relish about them quite their own.” It is interesting to find the views she herself entertained on the subject of letter-writing as given in her Recollections of a Literary Life. It runs as follows: “Such is the reality and identity belonging to letters written at the moment and intended only for the eye of a favourite friend, that probably any genuine series of epistles were the writer ever so little distinguished would ... possess the invaluable quality of individuality which so often causes us to linger before an old portrait of which we know no more than that it is a Burgomaster by Rembrandt or a Venetian Senator by Titian. The least skilful pen when flowing from the fulness of the heart ... shall often paint with as faithful and life-like a touch as either of those great masters.”

Mary Russell Mitford’s friends were numerous, both here in England and on the other side of the Atlantic, and her sympathies were as wide as the great ocean that lies between us. She writes in later life: “I love poetry and people[ix] as well at sixty as I did at sixteen, and can never be sufficiently grateful to God for having permitted me to retain the two joy-giving faculties of admiration and sympathy by which we are enabled to escape from the consciousness of our own infirmities into the great works of all ages and the joys and sorrows of our immediate friends.”

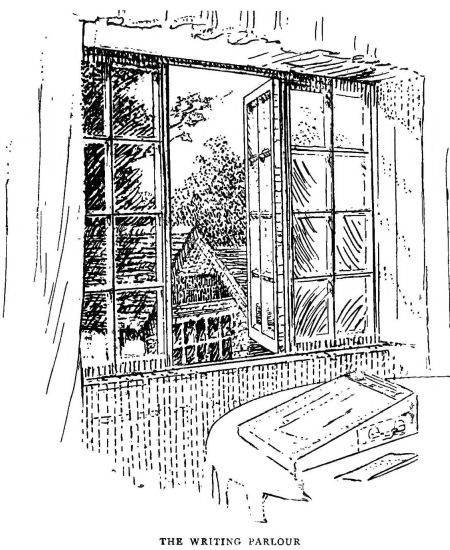

This sunny nature which was unembittered by severe trials speaks to us in all the stories of Our Village, and it spread such a halo about the scenes therein described that little Three Mile Cross—the prototype of Our Village—became in time a resort of pilgrims from far and near, among whom were some of the finest spirits of the age. All longed to gaze upon the cottage in which Mary Russell Mitford had dwelt, and to sit in the small parlour whose window looks down upon the village street, where she had written the stories so dear to her readers.

Happily the cottage itself, with the little general shop on one side and the village inn on the other, are still so much what they were in her day that the long space of time that has rolled by since her room was left vacant seems to vanish, and as we enter the front door we[x] almost expect to see the small figure of the “lady of Our Village” coming down the narrow stairs to welcome us.

Before closing this Preface I would express my gratitude to Lord Treowen, Mr. and Mrs. Alfred Palmer, Mr. F. Cowslade, Mr. W. May, the Misses Lovejoy, and Mr. J. J. Cooper, for permission to reproduce valuable portraits and relics, and for other kind help.

CONSTANCE HILL.

Grove Cottage,

Frognal, Hampstead,

August, 1919.

[xi]

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | AN AUTHOR’S BIRTHPLACE | 1 |

| II . | HAPPY MEMORIES | 9 |

| III . | VILLAGE NEIGHBOURS | 15 |

| IV . | EARLY LIFE IN READING | 22 |

| V . | LYME REGIS | 29 |

| VI . | A STORMY COAST | 40 |

| VII . | A FLIGHT | 52 |

| VIII . | RETURN TO READING | 56 |

| IX . | THE SCHOOL IN HANS PLACE | 66 |

| X . | A GLIMPSE OF OLD FRENCH SOCIETY | 74 |

| XI . | THE GAY REALITIES OF MOLIÈRE | 82 |

| XII . | RECOLLECTIONS OF OLD READING | 92 |

| XIII . | A NORTHERN TOUR | 101 |

| XIV . | A ROYAL VISIT | 110 |

| XV . | PLAYS AND POETRY | 119 |

| XVI . | A CHOSEN CORRESPONDENT | 126 |

| XVII . | THE MARCH OF MIND | 134 |

| XVIII . | VERSATILITY AND PLAYFULNESS | 144 |

| XIX . | FROM MANSION TO COTTAGE | 156 |

| XX . | THREE MILE CROSS | 161 |

| XXI . | THE NEW HOME | 179 |

| XXII . | A LOQUACIOUS VISITOR | 190 |

| XXIII . | THE PUBLICATION OF “OUR VILLAGE” | 203 |

| XXIV . | A COUNTRY-SIDE ROMANCE | 212[xii] |

| XXV . | A NEW PLAYWRIGHT | 221 |

| XXVI . | “RIENZI” | 230 |

| XXVII . | FOREIGN NEIGHBOURS | 241 |

| XXVIII . | AGREEABLE JAUNTS | 250 |

| XXIX . | UFTON COURT | 260 |

| XXX . | A FURTHER GLANCE AT OUR VILLAGE | 271 |

| XXXI . | ECCENTRIC NEIGHBOURS | 283 |

| XXXII . | THE MAY-HOUSES | 292 |

| XXXIII . | WALKS IN THE COUNTRY | 302 |

| XXXIV . | A CENTRE OF INTEREST | 315 |

| XXXV . | A LONDON WELCOME | 328 |

| XXXVI . | A BRAVE HEART | 339 |

| XXXVII . | FAREWELL TO THREE MILE CROSS | 350 |

| XXXVIII . | SWALLOWFIELD | 360 |

| XXXIX . | PEACEFUL CLOSING YEARS | 372 |

| PAGE | |

| Portrait of Mary Russell Mitford. (By A. Burt, taken in 1836) | Frontispiece |

| Grove Cottage, Frognal, Hampstead | Preface x |

| The Mitfords’ house in Broad Street, Alresford | 3 |

| Antique girandole | 8 |

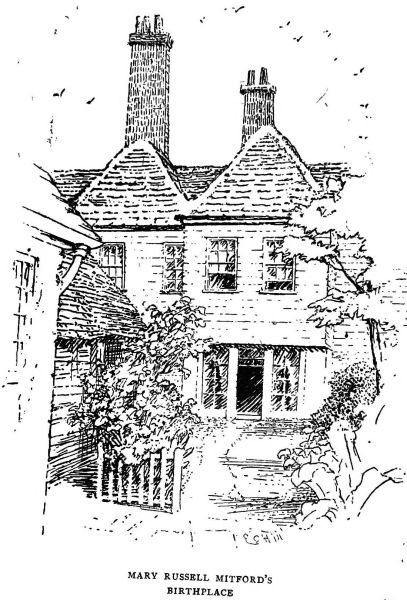

| Mary Russell Mitford’s birthplace | 11 |

| Mary Russell Mitford at the age of four years. (After a miniature) | To face 16 |

| The Cross-house | 21 |

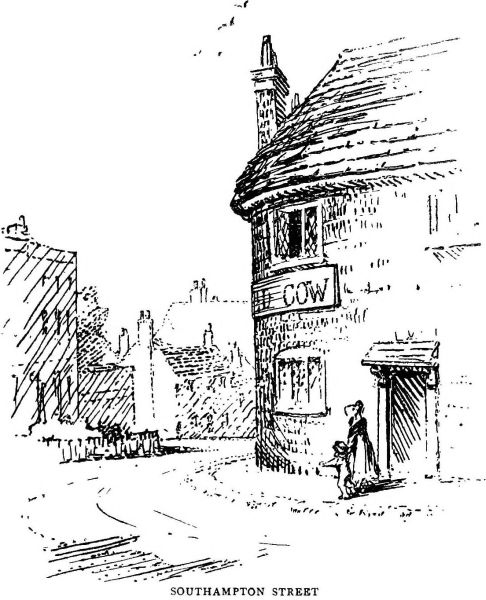

| Southampton Street, Reading | 24 |

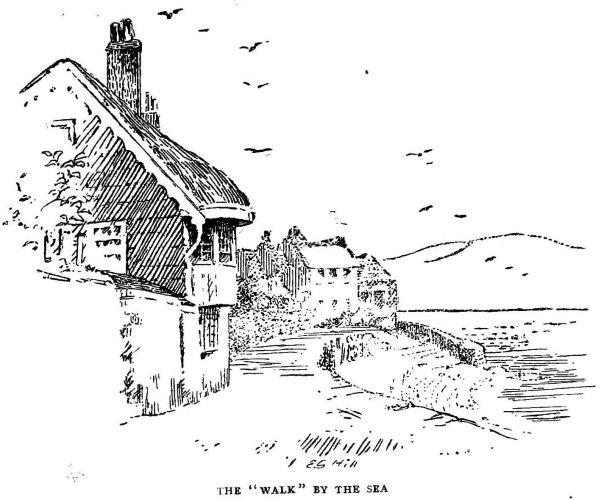

| The “Walk” by the sea, Lyme Regis | 31 |

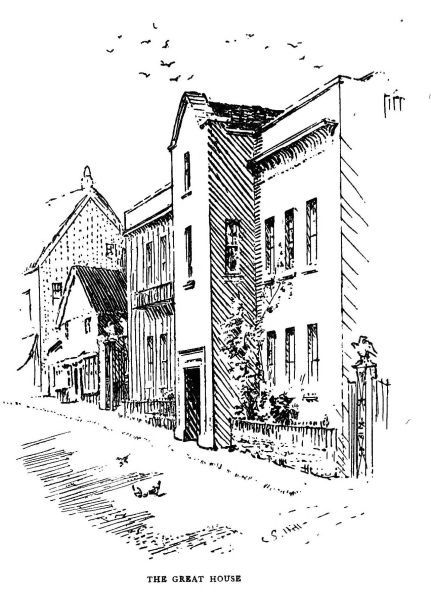

| The Great House, Lyme Regis | 35 |

| Old ironwork | 39 |

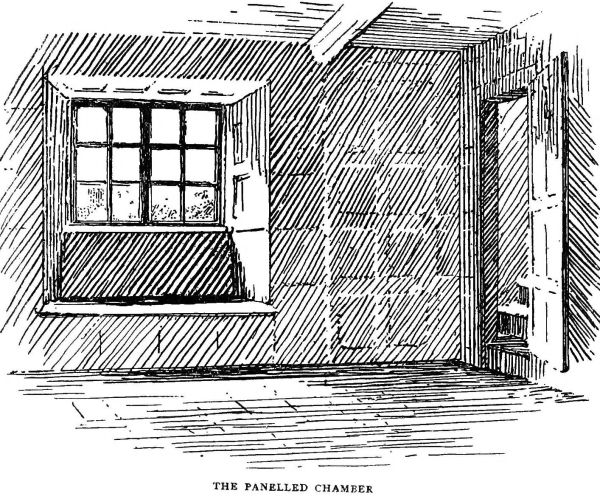

| The panelled chamber | 41 |

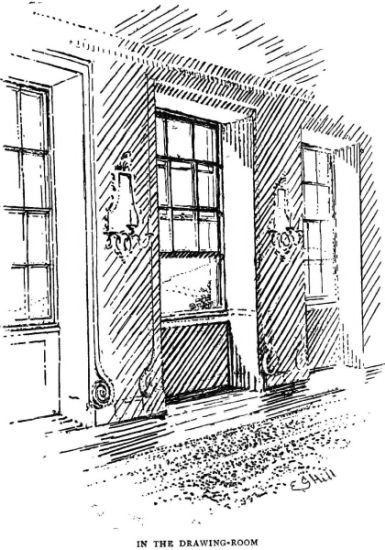

| The drawing-room | 47 |

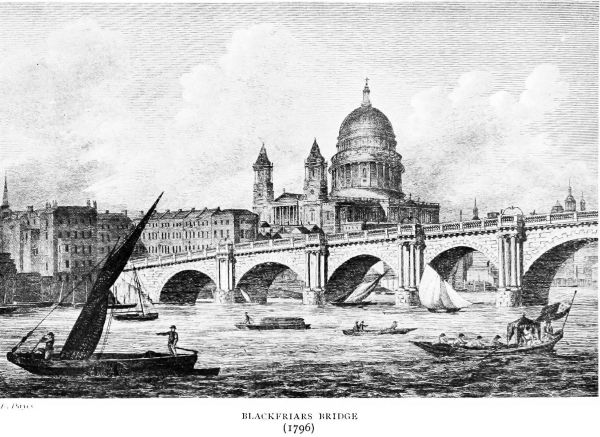

| Blackfriars Bridge in 1796 | 52 |

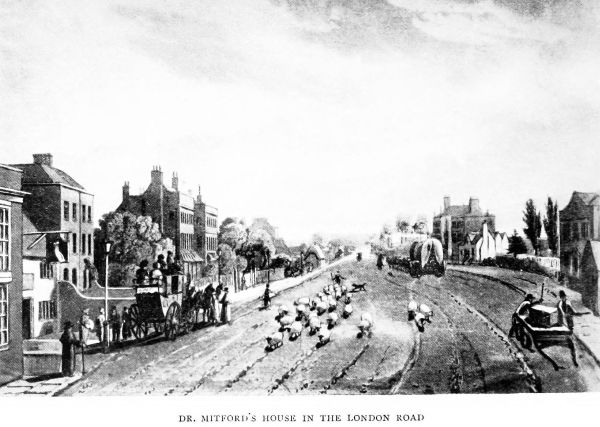

| Dr. Mitford’s house in the London Road, Reading | To face 58 |

| Antique ironwork | 65 |

| Hans Place in 1798 | 69 |

| Ceiling decoration (1714) | 81 |

| A purse-bag | 91 |

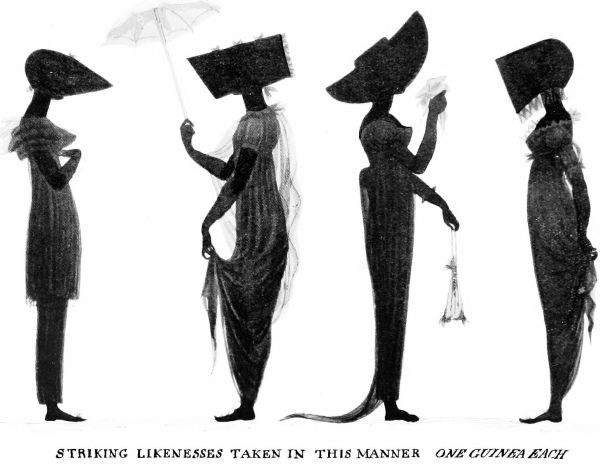

| A skit on the “Pink of the mode” | To face 92 |

| A quaint tea-set | 100 |

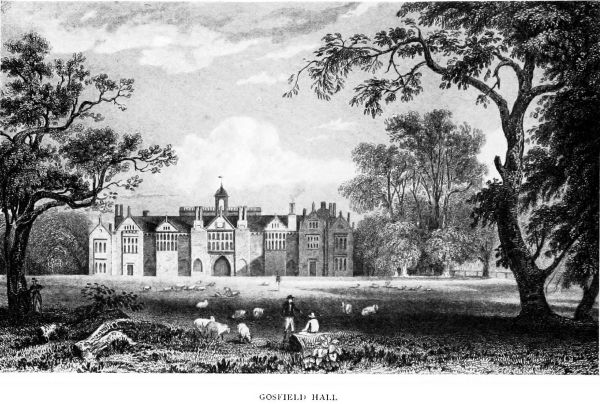

| Gosfield Hall | To face 110 |

| Le Comte d’Artois (afterwards Charles X ) | To face 112 |

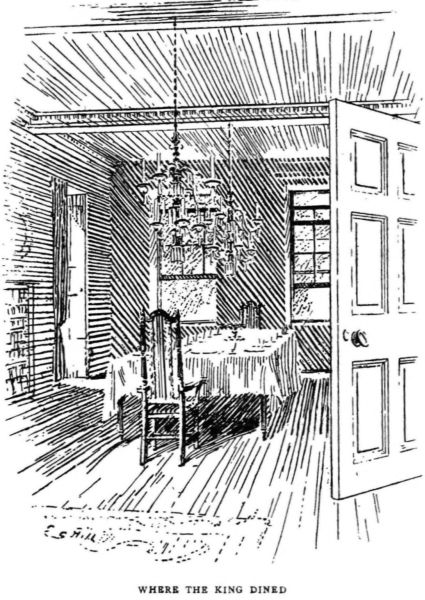

| The Dining-room in the Deanery, Bocking | 115 |

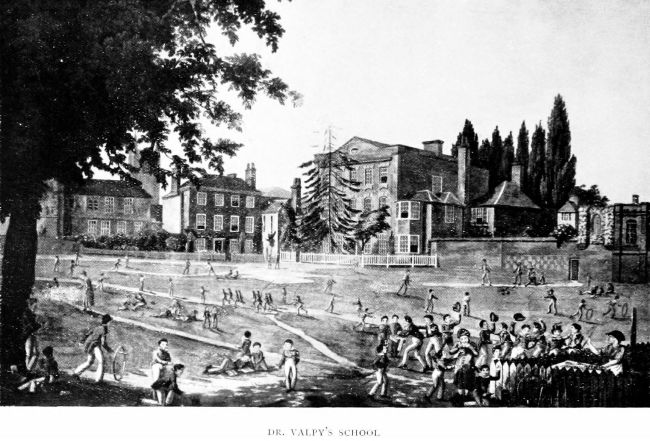

| Dr. Valpy’s school | To face 122 |

| Country cottages | 143 |

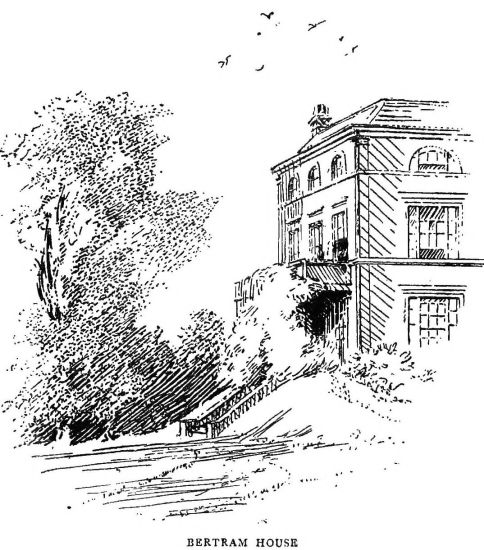

| Bertram House | 147 |

| Inlaid tea-caddy | 160 |

| The Mitfords’ cottage in Three Mile Cross | 163[xiv] |

| The village shop | 169 |

| The Swan Inn | 173 |

| A country wheelbarrow | 178 |

| Miss Mitford’s writing-parlour | 181 |

| The wheelwright’s workshop | 185 |

| Fragment of the Silchester Roman wall | 189 |

| Where the curate lodged | 193 |

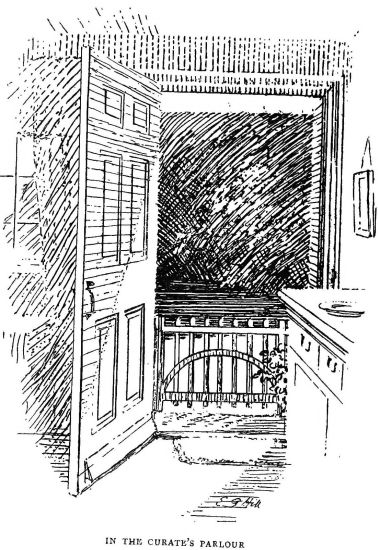

| The curate’s parlour | 197 |

| An old Berkshire farm | 213 |

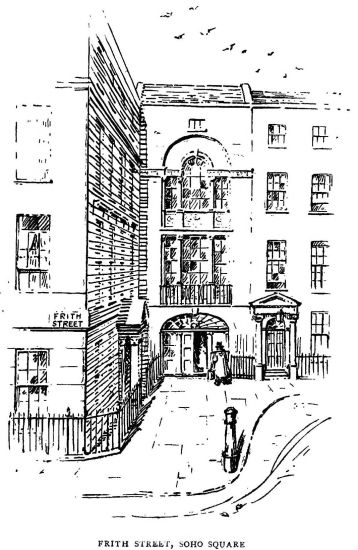

| Frith Street, Soho Square | 225 |

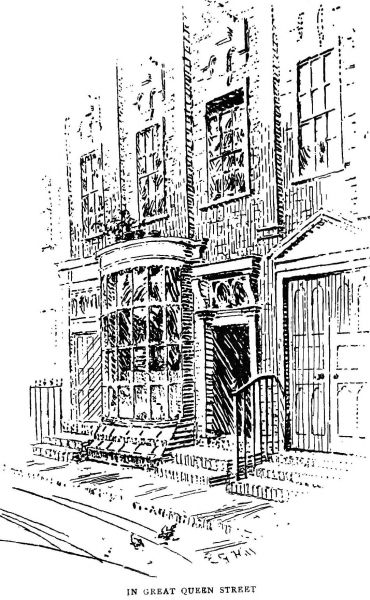

| Old houses in Great Queen Street | 233 |

| A French bonbonnière | 249 |

| The West Gate, Southampton | 251 |

| Pulteney Bridge, Bath | 254 |

| Arabella Fermor as a child. (After a picture in the possession of Frederick Cowslade, Esq.) | 259 |

| The Porch, Ufton Court | 261 |

| Arabella Fermor, the “Belinda” of the “Rape of the Lock,” afterwards Mrs. Perkins. (From a painting by W. Sykes in the possession of Lord Treowen) | To face 262 |

| Francis Perkins. (By W. Sykes, from a painting also in the possession of Lord Treowen) | To face 262 |

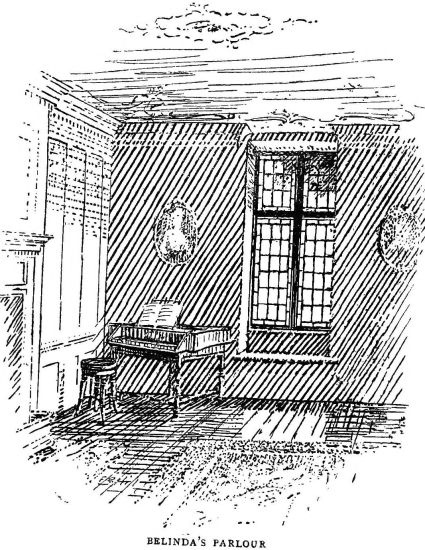

| Belinda’s parlour | 265 |

| The garden steps | 267 |

| A dandy of the period | 291 |

| An old shoeing forge | 297 |

| A bridge on the Loddon | 303 |

| In Aberleigh (Arborfield) Park | 307 |

| Dr. Mitford. (From a painting by John Lucas in the possession of W. May, Esq.) | To face 330 |

| Ironwork in the balcony of Sergeant Talfourd’s house | 338 |

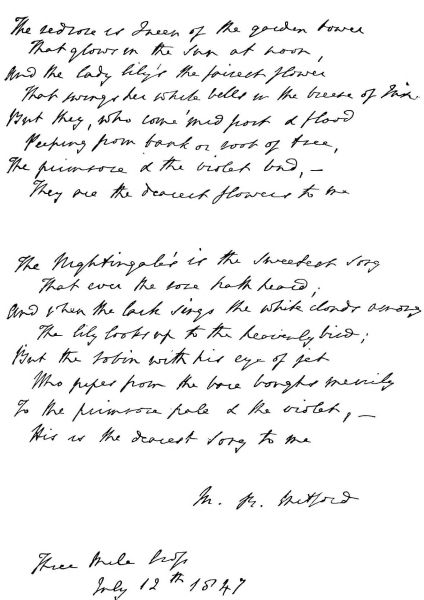

| Verses by M. R. Mitford written in a friend’s album (facsimile) | To face 344 |

| Old house near Swallowfield | 355 |

| A teapot which belonged to M. R. Mitford | 359 |

| M. R. Mitford’s last home at Swallowfield | 363 |

| Swallowfield Church | 380 |

AN AUTHOR’S BIRTHPLACE

In a sunny corner of Hampshire there lies the tiny historic town of Alresford on the gentle slopes of a hill, at whose feet flows the little river Arle which gives its name to the place. “A town so small that but for an ancient market very slenderly attended, nobody would have dreamt of calling it anything but a village.” And yet, oddly enough, in this same place great dignity was united with rustic simplicity, for the living of “Old” Alresford was one of the richest in England, and was held by the Bishop of Exeter in conjunction with his very poor see. The Post Office was formerly installed in a very small room with nothing but a letter-box in the window; still, it had its importance, being at the head of many others scattered over the country-side.

Alresford was the birthplace of one who loved nature as few have loved her, and whose writings “breathe the air of the hay-fields and the scent of the hawthorn boughs,” and seem to[2] waft to us “the sweet breezes that blow over ripened, cornfields or daisied meadows.”

The name of Mary Russell Mitford—the author of Our Village—is dear to thousands of readers, both English and American, for she has enabled them to see nature with her eyes and to enter into the very spirit of rural life.

Alresford is built on the plan of the letter T, at the top of which stands the old church; Broad Street being the perpendicular stem, traversed by East Street and West Street, which form the cross-bar.

Supposing that we are coming up from the valley below where we have left behind us the winding river with its old mill, we enter the lower end of Broad Street—that picturesque street with its raised footpaths on either side bordered by trees, and its low, irregular houses, dominated at the upper end by the grey tower of the old church. That dignified looking house on the right-hand side, with its hooded doorway and its tall windows, belonged to Dr. Mitford.

Here it was that the doctor started a practice soon after his marriage with Miss Russell, the only child and heiress of the late Dr. Russell, Rector of Ashe, and here, on the 16th December, 1787, Mary, also an only child, was born.

[3]

THE HOUSE IN BROAD STREET

[4]

[5]

“A pleasant house in truth it was,” she writes. “The breakfast-room ... was a lofty and spacious apartment literally lined with books, which, with its Turkey carpet, its glowing fire, its sofas and its easy-chairs, seemed, what indeed it was, a very nest of English comfort. The windows opened on a large old-fashioned garden, full of old-fashioned flowers—stocks, roses, honeysuckles and pinks; and that again led into a grassy orchard, abounding with fruit trees....

“What a playground was that orchard! and what playfellows were mine! My maid Nancy with her trim prettiness, my own dear father, handsomest and cheerfullest of men, and the great Newfoundland dog Coe, who used to lie down at my feet as if to invite me to mount him, and then to prance off with his burthen, as if he enjoyed the fun as much as we did!... How well I remember my father’s carrying me round the orchard on his shoulder, holding fast my little three-year-old feet, whilst the little hands hung on to his pig-tail, which I called my bridle; hung so fast, and tugged so heartily, that sometimes the ribbon would come off between my fingers and send his hair floating and the powder flying down his back!... Happy, happy days! It is good to have the memory of such a childhood!”

[6]

Miss Mitford writes on another occasion:—

“In common with many only children, I learnt to read at a very early age. My father would perch me on the breakfast-table to exhibit my only accomplishment to some admiring guest, who admired all the more [from my being] a small puny child, gifted with an affluence of curls [who] might have passed for the twin sister of my own great doll. On the table was I perched to read some Foxite newspaper, Courier or Morning Chronicle, the Whiggish oracles of the day.... I read leading articles to please the company; and my dear mother recited ‘The Children in the Wood’ to please me. This was my reward, and I looked for my favourite ballad after every performance, just as the piping bull-finch that hung in the window looked for his lump of sugar after going through ‘God save the King.’ The two cases were exactly parallel.”

We have sat in the very room where this scene took place. Little is changed there, and we stepped from its windows “opening down to the ground” into the garden. A narrow footpath, bordered by greensward, led to a small flagged courtyard, flanked on one side by a quaint old brew-house, with its red-tiled roof and peaked windowed centre. Then, passing through a wicket-gate, we found ourselves in[7] the “large old-fashioned garden,” itself gay with flowers as of yore.

An adjoining house has arisen, since the Mitfords lived in their house more than a hundred years ago, but this building has in its turn grown old, so that it does not mar the character of the place.

Beyond the garden lay the orchard, now used as a tennis lawn, but still happily surrounded by trees, through whose boughs peeps of the sweet surrounding country can be seen. Indeed Alresford is entirely encircled by the country, and its three only streets—Broad Street, East Street, and West Street—lead straight into it. Miss Mitford, describing the views on either side of their grounds, says that to the south rose the “picturesque church with its yews and lindens, and beyond it a down as smooth as velvet, dotted with rich islands of coppice, hazel, woodbine and hawthorn”; while down in the valley “gleamed a bright, clear lakelet radiant with swans and water-lilies, which the simple townsfolk were content to call the ‘Great Pond.’”

Dr. Mitford’s house must indeed have been a “pleasant home” for a child, with its garden and orchard for a playground behind the house, and, in front, its cheerful view of the village street with its ever-changing scenes of passing[8] horsemen and carts, or of herds of sheep and cattle driven to market.

Here Mary first learnt, though unconsciously, to enjoy the beauties of nature and to enter into the simple pleasures of village life.

[9]

HAPPY MEMORIES

The market of old days used to be held in an open space where East Street and West Street meet, near to the Bell Inn, whose gilded sign, in the form of a bas-relief, is displayed over its entrance.

Here we can fancy the little Mary being taken to see the gay booths with their display of toys or of ginger-bread, and the sheep or pigs in pens.

Miss Mitford was warmly attached to the place of her birth, and often alludes to it, but usually under the pseudonym of “Cranley.”

“One of the noisiest inhabitants,” she writes, “of the small, irregular town of Cranley, in which I had the honour to be born, was a certain cobbler by name Jacob Giles. He lived exactly over-right our house in a little appendage to the baker’s shop.... At his half-hatch might he be seen stitching and stitching, with the peculiar, regular two-handed jerk proper to the art of cobbling, from six in the morning to six at[10] night.... There he sat with a dirty red night-cap over his grizzled hair, a dingy waistcoat and old blue coat, darned, patched and ragged, and a greasy leathern apron....

“The face belonging to this costume was rough and weather-beaten, deeply lined and deeply tinted of a right copper colour, with a nose that would have done honour to Bardolph, and a certain indescribable half-tipsy look, even when sober. Nevertheless the face, ugly and tipsy as it was, had its merits.... There was good humour in the half-shut eye, the pursed-up mouth and the whole jolly visage.... There he sat in that small den, looking something like a thrush in a goldfinch’s cage, and singing with as much power and far wider range—albeit his notes were hardly as melodious—Jobson’s songs in the ‘Devil to Pay’ and ‘A cobbler there was, and he lived in a stall, which served him for parlour, for kitchen and hall’ being his favourites.

“... Poor as he was Jacob Giles had always something for those poorer than himself; would share his scanty dinner with a starving beggar, and his last quid of tobacco with a crippled sailor. The children came to him for nuts and apples, for comical stories and droll songs; the very curs of the street knew that they had a friend in the poor cobbler.

[11]

MARY RUSSELL MITFORD’S BIRTHPLACE.

[12]

[13]

“For my own part I can recollect Jacob Giles as long as I can recollect anything. He made the shoes for my first doll (pink I remember they were)—a doll called Sophie, who had the misfortune to break her neck by a fall from the nursery window. Jacob Giles mended all the shoes of the family, with whom he was a universal favourite.... He used to mimic Punch for my amusement, and I once greatly offended the real Punch by preferring the cobbler’s performance of the closing scene.”

Writing in after years, Miss Mitford remarks: “Where my passion for plays began it is difficult to say. Perhaps at the little town of Alresford, when I was somewhat short of four years old, and was taken by my dear father to see one of the greatest tragedies of the world set forth in a barn. Even now I have a dim recollection of a glimmering row of candles dividing the end which was called the stage from the part which did duty as pit and boxes, of the black face and the spangled turban, of my wondering admiration, and the breathless interest of the rustic audience.”

Among some of her happiest recollections of early childhood were her rides on horseback with her father. “This dear papa of mine,” she writes, “whose gay and careless temper all the professional etiquette of the world could[14] never tame into the staid gravity proper to a doctor of medicine, happened to be a capital horseman, and abandoning the close carriage almost wholly to my mother used to pay his country visits on a favourite blood mare, whose extreme docility and gentleness tempted him into having a pad constructed, perched upon which I might occasionally accompany him, when the weather was favourable and the distance not too great.

“A groom, who had been bred up in my grandfather’s family, always attended us, and I do think that both Brown Bess and George liked to have me with them almost as well as my father did. The old servant, proud, as grooms always are, of a fleet and beautiful horse, was almost as proud of my horsemanship, for I, cowardly enough, Heaven knows, in after years, was then too young and too ignorant for fear—if it could have been possible to have any sense of danger when strapped so tightly to my father’s saddle, and enclosed so fondly by his strong and loving arm. Very delightful were those rides across the breezy Hampshire downs on a sunny summer morning!”

[15]

VILLAGE NEIGHBOURS

In one of Miss Mitford’s tales entitled A Country Barber she describes a humble neighbour whose tiny shop adjoined their own “handsome and commodious dwelling.” This tiny shop has long since disappeared, having given place to the “adjoining house” already mentioned.

“The barber’s shop,” we are told, “consisted of a low-browed cottage with a pole before it, and a half-hatch always open, through which was visible a little dusty hole where a few wigs, on battered wooden blocks, were ranged round a comfortable shaving chair. There was a legend, over the door in which ‘William Skinner, wig-maker, hairdresser, and barber’ was set forth in yellow letters on a blue ground.”

After speaking of her happy early recollections of “Will Skinner,” Miss Mitford remarks: “So agreeable indeed is the impression which he has left in my memory that I cannot help regretting the decline and extinction of a race[16] which, besides figuring so notably in the old novels and comedies, formed so genial a link between the higher orders of society, supplying to the rich the most familiar of followers and most harmless of gossips.”

How vividly these words recall to our mind Sir Walter Scott’s old Caxon the barber and familiar follower of Mr. Oldbuck, “who was accustomed to bring to his patron each morning along with the powder and pomatum his version of the politics or the gossip of the neighbourhood.

“‘Heeh, sirs!’ he exclaims, ‘nae wonder the commons will be discontent, when they see magistrates, and bailies, and deacons, and the provost himsell wi’ heads as bald and as bare as one o’ my blocks!’

“It certainly was not Will Skinner’s beauty,” writes Mary Mitford, “that caught my fancy. His person was hardly of the kind to win a lady’s favour, even although that lady were only four years of age.... Good old man! I see him in my mind’s eye at this moment: lean, wrinkled, shabby, poor, slow of speech, and ungainly of aspect, yet pleasant to look at and delightful to recollect. It was the overflowing kindness of his temper that rendered Will Skinner so general a favourite. Poor he was certainly and lonely, for he had been crossed[17] in love in his youth, and lived alone in his little tenement, with no other companions than his wig blocks and a tame starling. ‘Pretty company’ he used to call them.

MARY RUSSELL MITFORD

From a miniature

“His fortunes had at one time assumed a more flourishing aspect when the Bishop of Exeter and Rector of Alresford had employed him to superintend the ‘posting’ of his wig, and had also promoted him to the posts of sexton and of deputy parish clerk. But on the death of the Bishop, and on the advent of the French Revolution, when cropped heads came into fashion and powder and hairdressing went out, poor Will found himself nearly at his wit’s end. In this dilemma he resolved to turn his hand to other employments, and, living in the neighbourhood of a famous trout stream, he applied himself to the construction of artificial flies.

“This occupation he usually followed in his territory the churchyard, a place ... occupying a gentle eminence by the side of Cranley Down—a down on which the cricketers of that cricketing country used to muster two elevens for practice, almost every fine evening, from Easter to Michaelmas. Thither Will, who had been a cricketer himself in his youth, and still loved the wind of a ball, used to resort on summer afternoons, perching himself on a large[18] square raised monument, a spreading lime tree above his head, Izaak Walton before him, and his implements of trade at his side. There he sat, now manufacturing a cannon-fly, and now watching Tom Taylor’s unparagoned bowling.

“On this spot our intimacy commenced. A spoilt child and an only child, it was my delight to escape from nurse and nursery and to follow everywhere the dear papa, [even] to the cricket ground, in spite of all remonstrance, causing him no small perplexity as to how to bestow me in safety during the game. Will and the monument seemed to offer exactly the desired refuge, and our good neighbour readily consented to fill the post of deputy nursery-maid for the time, assisted in his superintendence by our very beautiful and sagacious black Newfoundland dog called Coe....

“Poor dear old man, what a life I led him!—now playing at bo-peep on one side of the great monument and now on the other; now crawling away amongst the green graves; now gliding round before him, and laughing up in his face as he sat.... How he would catch me away from the very shadow of danger if a ball came near; and how often did he interrupt his own labours to forward my amusement, sliding from his perch to gather lime branches to stick in Coe’s collar, or to collect daisies,[19] buttercups, or ragged-robins to make what I used to call daisy-beds for my doll.”

Here is another pretty incident of the Alresford life recorded by Miss Mitford.

“Before we left Hampshire,” she writes, “my maid Nancy married a young farmer, and nothing would serve her but I must be bridesmaid. And so it was settled.

“I remember the whole scene as if it were yesterday! How my father took me himself to the churchyard gate, where the procession was formed, and how I walked next to the young couple hand-in-hand with the bridegroom’s man, no other than the village blacksmith, a giant of six feet three, who might have served as a model for Hercules. Much trouble had he to stoop low enough to reach down to my hand, and many were the rustic jokes passed upon the disproportioned pair....

“In this order, followed by the parents on both sides, and a due number of uncles, aunts and cousins, we entered the church, where I held the glove with all the gravity and importance proper to my office; and so contagious is emotion that when the bride cried, I could not help crying for company. But it was a love-match, and between smiles and blushes Nancy’s tears soon disappeared, and so did mine. The happy husband helped his pretty wife into her[20] own chaise-cart, my friend the blacksmith lifted me in after her, and we drove gaily to the large, comfortable farm-house where her future life was to be spent.

“The bride was [soon] taken to survey her new dominions by her proud bridegroom, and the blacksmith, finding me, I suppose, easier to carry than to lead, followed close upon their steps with me in his arms.

“Nothing could exceed the good nature of my country beau; he pointed out bantams and pea-fowls, and took me to see a tame lamb and a tall, staggering calf, born that morning; but for all that I do not think I should have submitted to the indignity of being carried if it had not been for the chastening influence of a little touch of fear. Entering the poultry yard I had caught sight of a certain turkey-cock, who erected that circular tail of his, and swelled out his deep red comb and gills after a fashion familiar to that truculent bird, but which up to the present hour I am far from admiring....

“[At last] we drew back to the hall, a large square bricked apartment, with a beam across the ceiling and a wide yawning chimney, where many young people being assembled, and one of them producing a fiddle, it was agreed to have a country dance until dinner should be ready, the bride and bridegroom leading off, and I following with the bridegroom’s man.

[21]

“Oh! the blunders, the confusion, the merriment of that country dance! No two people attempted the same figure; few aimed at any figure at all; each went his own way; many stumbled, some fell, and everybody capered, laughed and shouted at once!”

[22]

EARLY LIFE IN READING

Towards the end of the year 1791, before the little Mary had become quite four years old, a change came over the fortunes of the family.

Dr. Mitford, in spite of some really good qualities, was of a careless and thoughtless disposition as regards money matters, and was, unhappily, addicted to games of chance. “He had the misfortune,” writes his daughter, “to be the best whist player in England,” and like the celebrated Mr. Micawber and so many of his class, he had an unchanging faith in his own “good luck,” and felt confident that however dark the horizon might be something would turn up to his advantage. “Dr. Mitford,” remarks a shrewd writer, “belonged to that class of impecunious individuals who seem to have been born insolvent.”

He had come into possession of a large fortune on his marriage, for his bride-elect had refused to have any settlement made concerning[23] property under her own control, and this fortune had already nearly melted away.

In spite, however, of all his thoughtless extravagance, from which both wife and child suffered severely, they remained at all times devoted to him. As she grew older Mary could not shut her eyes to her father’s faults; but she loved him in spite of them, dwelling constantly in her writings upon his invariable kindness to her as a child, which claimed, she considered, her lasting gratitude. “He possessed indeed,” she remarks, “every manly and generous quality, excepting that which is so necessary in this workaday world—the homely quality called prudence.”

On leaving Alresford, where many of their valued possessions had to be sold, the little family removed to a house in Southampton Street, Reading, where the doctor hoped to establish a practice. This street, which crosses the river Kennet by a stone bridge, has still an old-world appearance, with its modest-looking dwelling-houses and its old-fashioned inns; while high above its roofs rises the spire of the old church of St. Giles.

SOUTHAMPTON STREET

It is in connection with this very church that we have a pleasant glimpse of the little Mary from the pen of Mrs. Sherwood, then a young girl living in Reading. “I remember,” she[24] writes, “once going to a church in the town, which we did not usually attend, and being taken into Mrs. Mitford’s pew, where I saw the young authoress, Miss Mitford, then about four[25] years old. Miss Mitford was standing on the seat, and so full of play that she set me on to laugh in a way which made me thoroughly ashamed.”

Writing of this same period in after life, Mary Mitford says: “It is now about forty years since I, a damsel scarcely so high as the table on which I am writing, and somewhere about four years old, first became an inhabitant of Belford Regis” (her name for Reading), “and really I remember a great deal not worth remembering concerning the place, especially our own garden and a certain dell on the Bristol road to which I used to resort for primroses.”

It was during this first residence in Reading, when she was still a small child, that she saw London for the first time.

“Business called my father thither in the middle of July,” she writes, “and he suddenly announced his intention of driving me up in his gig (a high open carriage holding two persons), unencumbered by any other companion, male or female. George only, the old groom, was sent forward with a spare horse over-night to Maidenhead Bridge, and, the dear papa conforming to my nursery hours, we dined at Crauford Bridge ... and reached Hatchett’s Hotel, Piccadilly (the New White Horse Cellar of the old stage-coaches), early in the afternoon....

“I had enjoyed the drive past all expression,[26] chattering all the way, and falling into no other mistakes than those common to larger people than myself of thinking that London began at Brentford, and wondering in Piccadilly when the crowd would go by; and I was so little tired when we arrived that, to lose no time, we betook ourselves that night to the Haymarket Theatre, the only one then open. I had been at plays in the country, in a barn in Hampshire ... but the country play was nothing to the London play—a lively comedy with the rich caste of those days—one of the comedies that George III enjoyed so heartily. I enjoyed it as much as he, and laughed and clapped my hands and danced on my father’s knee, and almost screamed with delight, so that a party in the same box, who had begun by being half angry at my restlessness, finished by being amused with my amusement.

“The next day, my father, having an appointment at the Bank, took the opportunity of showing me St. Paul’s and the Tower.

“At St. Paul’s I saw all the wonders of the place, whispered in the whispering gallery, and walked up the tottering wooden stairs, not into the ball itself but to the circular balustrade of the highest gallery beneath it. I have never been there since, but I can still recall most vividly that wonderful panorama: the strange[27] diminution produced by the distance, the toy-like carriages and horses, and men and women moving noiselessly through the toy-like streets.... Looking back to that [scene] what strikes me most is the small dimensions to which the capital of England was then confined. When I stood on the topmost gallery of St. Paul’s I saw a compact city spreading along the river, it is true, from Billingsgate to Westminster, but clearly defined to the north and to the south, the West-End beginning at Hyde Park on the one side and the Green Park on the other. Then Belgravia was a series of pastures and Paddington a village.

“We proceeded to the Tower, that place so striking by force of contrast ... the jewels and the armoury glittering ... amidst the gloom of the old fortress and the stories of great personages imprisoned, beheaded, buried within its walls;—a dreary thing it seemed to be a queen! But at night I went to Astley’s, and I forgot the sorrows of Lady Jane Grey and Anne Boleyn in the wonders of the horsemanship and the tricks of the clown.”

Into the last day were crowded visits to the Houses of Lords and Commons, to Westminster Abbey, to Cox’s Museum in Spring Gardens, to the Leverian Museum in the Blackfriars Road, and finally at night to the theatre once more,[28] returning home on the morrow “without a moment’s weariness of mind or body.”

About this time Lord Charles Murray-Aynsley, a younger son of the Duke of Athol, became engaged to be married to a cousin of the Mitfords.

“Lord Charles, as fine a young man as one should see in a summer’s day, tall, well-made, with handsome features ... and charming temper, had an infirmity which went nigh to render all [his] good gifts of no avail; a shyness, a bashfulness, a timidity most painful to himself and distressing to all about him.... That a man with such a temperament, who could hardly summon courage to say ‘How d’ye do?’ should ever have wrought himself up to the point of putting the great question was wonderful.... I myself, a child not five years old, one day threw him into an agony of blushing by running up to his chair in mistake for my papa. Now I was a shy child, a very shy child, and as soon as I arrived in front of his lordship and found that I had been misled by a resemblance of dress, by the blue coat and buff waistcoat, I first of all crept under the table, and then flew to hide my face in my mother’s lap; my poor fellow-sufferer, too big for one place of refuge, too old for the other, had nothing for it but to run away, which, the door being luckily open, he happily accomplished.”

[29]

LYME REGIS

Dr. Mitford had been gradually establishing a practice in Reading, where a remarkable cure he had effected was already making his name known, when, as his daughter tells us, he resolved to remove to Lyme, “feeling with characteristic sanguineness that in a fresh place success would be certain.”

Some of our readers will no doubt have visited Lyme Regis—that quaint little seaport situated on the steep slope of a hill, whose main street seems, as Jane Austen has remarked, “to be almost hurrying into the water.” They will remember its harbour formed by the curved stone piers of the old Cobb, from which can be seen the pretty bay with its sandy beach bordered by the Parade, or “Walk” as it used to be called, which runs at the foot of a grassy hillside. At the town end of this “Walk” are to be seen some thatched cottages nestling under the shelter of the hill, and beyond them on a small promontory, jutting out into the sea,[30] the old Assembly Rooms. A few miles east-ward lies the sunny little bay of Charmouth, with a grand chain of hills beyond it, rising from the water’s edge and terminating in the far distance in the Bill of Portland.

Lyme Regis lies in the borderland of Dorset and Devonshire, “but the character of the scenery,” writes Miss Mitford, “the boldness of the coast, and the rich woodiness of the inland views belong entirely to Devonshire—beautiful Devonshire.

“Our habitation,” she continues, “although situated not merely in the town but in the principal street, had nothing in common with the small and undistinguished houses on either side. It was a very large, long-fronted stone mansion, terminated at either end by massive iron gates, the pillars of which were surmounted by spread eagles. An old stone porch, with benches on either side, projected from the centre, covered, as was the whole front of the house, with tall, spreading, wide-leafed myrtle, abounding in blossom, with moss-roses, jessamine and passion-flowers.”[31]

THE “WALK” BY THE SEA

This old porch had its special historical association, for here William Pitt as a child used to play at marbles when his father the great Lord Chatham rented the Great House. Unhappily the porch has been altered and injured [33]since we visited Lyme some years ago. Other changes have also been made at various periods, notably a storey added in the northern or upper end of the building; but in spite of these changes the Great House, as it is always called, still dominates the little town like a feudal castle of old amongst its vassals, its massive walls manfully resisting modern innovations.

The illustration represents the house as it appeared in Miss Mitford’s day.

The southern portion of the building is of the most ancient date. Its walls are of great thickness. The Great House is full of traditions of past history, and its gloomy vaults and passages below ground must have witnessed many a tragic scene at the time of the Monmouth Rebellion. Here it was that Judge Jeffreys took up his quarters for a time when he came to stamp out the Rebellion and to wreak the vengeance of James II upon the unhappy followers of his rival. The owner of the house in those days was a man named Jones—the squire of Lyme—who aided and abetted Jeffreys in all his awful tyranny, spying upon the inhabitants and reporting every idle word that might serve to incriminate them. The memory of Jones is loathed to this day, and tradition declares the house to be haunted by his ghost.

[34]

Happily the little girl, who came to live in this weird old mansion, knew nothing of its tragic history, and could laugh and play with childish mirth above its sombre vaults. In her Recollections, Mary Mitford speaks of the “large, lofty rooms of the building, of its noble oaken staircases, its marble hall, and its long galleries,” and mentions “the book room,” where her grandfather Dr. Russell’s fine library was arranged. “Behind the building,” she says, “which extended round a paved quadrangle, was the drawing-room, a splendid apartment looking upon a little lawn surrounded by choice evergreens,” beyond which lay the spacious gardens.

The drawing-room still bears traces of its former dignity in its lofty ceiling and handsome dentil cornice, and also in its three tall recessed windows, whose side panels end in fine curled scrolls.[35]

THE GREAT HOUSE

“My own nurseries,” she says, “were spacious and airy, but the place which I most affected was a dark panelled chamber on the first floor, to which I descended through a private door by half a dozen stairs, so steep that, still a very small and puny child between eight and a half and nine and a half, and unable to run down them in the common way, I used to jump from one step to the other.”

[37]

We have entered this small panelled room, which is lighted by a narrow leaded window, and as we looked upon the steps leading down from the upper room we fancied we saw the tiny figure jumping from step to step.

“This chamber,” continues Miss Mitford, “was filled with such fossils as were then known ... some the cherished products of my own discoveries, and some broken for me by my father’s little hammer from portions of the rocks that lay beneath the cliffs, under which almost every day we used to wander hand-in-hand.”

Beyond “the little lawn, surrounded by choice evergreens,” there was “an old-fashioned greenhouse and a filbert-tree walk, from which again three detached gardens sloped abruptly down to one of the clear, dancing rivulets of that western country.” These three gardens are still to be seen. A part of them is well cultivated, and abounds in smooth lawns, majestic trees and flowers of all kinds; but that part which belongs to the older portion of the mansion, deserted for many years, is left wild and untended. It is, however, pathetically beautiful in its mixture of garden flowers and showy weeds. The high box-edgings to the borders prove that great care was once taken of the place, and the tall rose bushes which still[38] abound stretch out their long branches of pink and white blossoms as if to hide what is mean and unsightly.

“In the steep declivity of the central garden,” writes Mary, “which I was permitted to call mine, was a grotto overarching a cool, sparkling spring, never overflowing its small sandy basin, which yet was always full.” “Years many and long,” she adds, “have passed since I sat beside that tiny fountain, and yet never have I forgotten the pleasure which I derived from watching its clear crystal wave.”

“The slopes on either side of the grotto,” she says, “were carpeted with strawberries and dotted with fruit trees. One drooping medlar, beneath whose pendent branches I have often hidden, I remember well.”

This spring is known in that country-side by the name of the “Lepers’ Well.” It is reached by a steep flight of rugged stone steps from the terrace above, and is still surrounded by old gnarled fruit trees, though the medlar seems to have disappeared. Beyond a low hedge at the foot of the grounds flows the little river Lym, clear and sparkling as ever.

Lyme is full of traditions, and this little river, at one spot, bears the name of “Jordan,” so called by a colony of Baptists who took refuge in the neighbourhood during the seventeenth[39] century. It was in “Jordan” that they immersed their converts, and the old Biblical names given by them to the adjoining fields of Jericho and Paradise still linger in that district.

“I used to disdain the [Devonshire] streamlets,” writes Mary, “with such scorn as a small damsel fresh from the Thames and the Kennett thinks herself privileged to display. ‘They call that a river here, papa! Can’t you jump me over it?’ quoth I in my sauciness. About a month ago I heard a young lady from New York talking in some such strain of Father Thames. ‘It’s a pretty little stream,’ said she, ‘but to call it a river!’ And I half expected to hear a complete reproduction of my own impertinence, and a request to be jumped from one end to the other of Caversham Bridge!”

[40]

A STORMY COAST

Writing of her sojourn at Lyme Regis Miss Mitford says:—

“That was my only opportunity of making acquaintance with the mighty ocean in its winter sublimity of tempest and storm; and partly perhaps from the striking and awful nature of the impression [upon the mind of] a lonely, musing, visionary child, the recollection remains indelibly fixed in my memory, fresh and vivid as if of yesterday....

“Once my father took me from my bed at midnight that I might see, from the highest storey of our house, the grandeur and the glory of the tempest; the spray rising to the very tops of the cliffs, pale and ghastly in the lightning, and hear the roar of the sea, the moaning of the wind, the roll of the thunder, and amongst them all the fearful sound of the minute guns, telling of death and danger on that iron-bound coast. Then in the morning I have seen the cold bright wintry sun shining gaily on the dancing sea, [41]still stirred by the last breath of the tempest, and on the floating spars and parted timbers of the wreck....

THE PANELLED CHAMBER

“My walks,” she writes, “were confined to[43] rambles on the shore with my maid, or still more to my delight with my dear father, the recollection of whose fond indulgence is connected with every pleasure of my childhood.... Sometimes we would go towards Charmouth, with its sweeping bay, passing below church and churchyard, perched high above us, and already undermined by the tide. Another time we bent our steps to the Pinny cliffs [that stretch away] on the western side of the harbour; the beautiful Pinny cliffs, where an old landslip had deposited a farm-house, with its outbuildings, its garden and its orchard, tossed half-way down amongst the rocks, its look of home and of comfort contrasting so strangely with the dark rugged masses above, below and around.

“My father, a dabbler in science, with his hammer and basket was engaged in breaking off fragments of rock, to search for curious spars and fossil remains; I in picking up shells and sea-weed.... What enjoyment it was to feel the pleasant sea-breeze, and see the sun dancing on the waters, and wander as free as the sea-bird over my head beneath those beetling cliffs![44] Now for a moment losing sight of the dear papa, and now rejoining him with some delicate shell, or brightly coloured sea-weed, or imperfect coruna ammoris, enquiring into the success of his graver labours, and comparing our discoveries and treasures.

“What pleasure too to rest at the well-known cottage, the general termination of our walk, where old Simon the curiosity-monger picked up a mongrel sort of livelihood by selling fossils and petrifactions to one class of visitors, and cakes and fruit and cream to another. His scientific bargains were not without suspicion of a little cheatery, as my companion used laughingly to tell him ... but the fruit and curds were honest, as I can well avouch; and the legends of petrified sea-monsters, with which they were seasoned, bones of the mammoth, and skeletons of the sea-serpent have always been amongst the pleasantest of my seaside recollections.”

Perhaps these “legends” had a tinge of prophecy in them, as it was only fifteen years later that Mary Anning, then a child of eleven years old, discovered in the rocks of Lyme Regis the gigantic fossil bones of the ichthyosaurus—a creature whose very jaw it seems exceeded six feet in length, and whose existence had hitherto been unknown. She also discovered[45] later on the remains of the plesiosaurus.[1]

[1] The entire skeletons of these actual creatures are now to be seen in the Natural History Museum at South Kensington.

Miss Anning kept a curiosity shop in a tiny house which is still to be seen facing the upper gates of the Great House. The King of Saxony, who visited Lyme in 1844, thus describes the place:—

“We had alighted from the carriage,” he writes, “and were proceeding along on foot when we fell in with a shop in which the most remarkable petrifactions and fossil remains—the head of an ichthyosaurus, beautiful ammonites, etc.—were exhibited in the window. We entered and found a little shop and adjoining chamber completely filled with fossil productions of the coast.... I was anxious [before leaving] to write down the address of the place, and the woman who kept the shop with a firm hand wrote her name ‘Mary Anning’ in my pocket-book, and added as she returned the book into my hands: ‘I am well known throughout the whole of Europe.’”

It is said that the King of Saxony paid a second visit to the fossil shop, when he invited Miss Anning to accompany him in his travelling coach and four to the scene of the great landslip at Pinny. On reaching a small farm-house on[46] the hillside they quitted the coach to roam about the fallen rocks. On their return they found an old country woman seated in the stately vehicle. She explained, with some confusion, that she wanted to be able to boast hereafter that she had sat for once in her life in a royal coach! The kindly monarch assured her that he was in no way displeased, and he handed her out of the coach with courtly politeness.

Miss Mitford in one of her letters remarks: “It is singular that the name of Mary Anning crosses me often. One of my friend Mr. Kenyon’s graceful poems is addressed to her, and Charmouth and Lyme are dear to me as being full of my first recollections of the sea. I should like of all things to go there again and make acquaintance with Mary Anning.”

Here are a few stanzas of the poem alluded to:—

[47]

IN THE DRAWING-ROOM

Writing of their residence in Lyme Mary says:—[49]

“My dear mother had three or four young relations, misses in their teens, staying with her and was sufficiently occupied in playing the chaperone to the dull gaieties of the place.... Of course I was too young to be admitted to the society, such as it was; but I had even then a dim glimmering perception of its being anything but exhilarating.”

Sometimes the company assembled in the Great House. “One incident that occurred there,” writes Miss Mitford—“a frightful danger—a providential escape—I shall never forget.

“There was to be a ball at the rooms, and a party of sixteen or eighteen persons, dressed for the assembly, were sitting in the dining-room at dessert. The ceiling was ornamented with a rich running pattern of flowers in high relief, the shape of the wreath corresponding pretty exactly with the company arranged round the oval table. Suddenly, without the slightest warning, all that part of the ceiling became detached and fell down in large masses upon the table and the floor. It seems even now all but miraculous how such a catastrophe could occur without danger to life or limb; but the only things damaged were the flowers and feathers of the ladies and the fruits and wines of the[50] dessert. I myself, caught instantly in my father’s arms, by whose side I was standing, had scarcely even time to be frightened, although after the danger was over our fair visitors of course began to scream.”

Towards the end of their year’s residence in Lyme Regis the fortunes of the Mitford family were once more clouded over.

“Nobody told me,” writes Mary, “but I felt, I knew, I had an interior conviction for which I could not have accounted ... that in spite of the company, in spite of the gaiety, something was wrong. It was such a foreshowing as makes the quicksilver in the barometer sink whilst the weather is still bright and clear.

“And at last the change came. My father went again to London and lost—I think, I have always thought so—more money.... Then one by one our visitors departed; and my father, who had returned in haste again, in equal haste left home, after short interviews with landlords, and lawyers, and auctioneers; and I knew—I can’t tell how, but I did know—that everything was to be parted with and everybody paid.

“That same night two or three large chests were carried away through the garden by George and another old servant, and a day or two after my mother and myself, with Mrs.[51] Mosse, the good housekeeper who lived with my grandfather, and the other maid-servant, left Lyme in a hack-chaise.”

After various delays, due partly to the breaking up of a camp between Bridport and Dorchester, the party pursued their journey in “a sort of tilted cart without springs.” “Doubtless,” remarks Mary, “many a fine lady would laugh at such a shift. But it was not as a temporary discomfort that it came upon my poor mother. It was her first touch of poverty. It seemed like the final parting from all the elegances and all the accommodations to which she had been used. I shall never forget her heart-broken look when she took her little girl upon her lap in that jolting caravan, nor how the tears stood in her eyes when we turned into our miserable bedroom when we reached the roadside alehouse where we were to pass the night. The next day we resumed our journey, and reached a dingy, comfortless lodging in one of the suburbs beyond Westminster Bridge.”

[52]

A FLIGHT

The “comfortless lodging” mentioned by Miss Mitford was on the Surrey side of Blackfriars Bridge, where Dr. Mitford, it seems, was able to find a refuge from his creditors within the rules of the King’s Bench.

“What my father’s plans were,” writes his daughter in later years, “I do not exactly know; probably to gather together what disposable money still remained after paying all debts from the sale of books, plate and furniture at Lyme and thence to proceed ... to practise in some distant town. At all events London was the best starting-place, and he could consult his old fellow-pupil and life-long friend, Dr. Babington, then one of the physicians to Guy’s Hospital, and refresh his medical studies with experiments and lectures. In the meanwhile his spirits returned as buoyant as ever, and so, now that fear had changed into certainty, did mine.”

BLACKFRIARS BRIDGE (1796)

But at this time, when the prospects of the family seemed to be irretrievably overclouded [53]and when dire poverty stared them in the face, an extraordinary event occurred to raise them suddenly into affluence!

“In the intervals of his professional pursuits,” writes Mary, “my father walked about London with his little girl in his hand; and one day (it was my birthday, and I was ten years old) he took me into a not very tempting-looking place which was, as I speedily found, a lottery office. An Irish lottery was upon the point of being drawn, and he desired me to choose one out of several bits of printed paper (I did not then know their significance) that lay upon the counter.

“‘Choose which number you like best,’ said the dear papa, ‘and that shall be your birthday present.’

“I immediately selected one, and put it into his hand: No. 2224.

“‘Ah,’ said my father, examining it, ‘you must choose again. I want to buy a whole ticket, and this is only a quarter. Choose again, my pet.’

“‘No, dear papa, I like this one best.’

“‘Here is the next number,’ interposed the lottery office keeper, ‘No. 2223.’

“‘Ay,’ said my father, ‘that will do just as well. Will it not, Mary? We’ll take that.’

“‘No,’ returned I obstinately, ‘that won’t[54] do. This is my birthday you know, papa, and I am ten years old. Cast up my number and you’ll find that makes ten. The other is only nine.”

“My father, superstitious like all speculators, struck with my pertinacity and with the reason I gave, resisted the attempt of the office keeper to tempt me by different tickets, and we had nearly left the shop without a purchase when the clerk who had been examining different desks and drawers, said to his principal:

“‘I think, sir, the matter may be managed if the gentleman does not mind paying a few shillings more. That ticket 2224 only came yesterday, and we have still all the shares: one-half, one-quarter, one-eighth, two-sixteenths. It will be just the same if the young lady is set upon it.’

“The young lady was set upon it, and the shares were purchased.

“The whole affair was a secret between us, and my father, whenever he got me to himself, talked over our future twenty thousand pounds—just like Alnaschar over his basket of eggs.

“Meanwhile time passed on, and one Sunday morning we were all preparing to go to church when a face that I had forgotten, but my father had not, made its appearance. It was the clerk of the lottery office. An express had just arrived from Dublin announcing that No. 2224 had been[55] drawn a prize of twenty thousand pounds, and he had hastened to communicate the good news.”

“Ah, me!” writes Miss Mitford in later life. “In less than twenty years what was left of the produce of the ticket so strangely chosen? What? except a Wedgwood dinner-service that my father had had made to commemorate the event, with the Irish harp within the border on one side and his family crest on the other! That fragile and perishable ware outlasted the more perishable money.”

The writer of a graceful article entitled, “In Miss Mitford’s Country,” which appeared in a magazine several years ago, saw at a friend’s house in Reading some odd pieces of this very dinner-service. These consisted of “a tureen of beautiful shape, two or three soup-plates and a couple of butter-boats and stands in one, in Wedgwood fashion.” When handling the china she observed “that the Mitford crest was stamped on one side of the pieces while on the opposite side appeared a harp bearing between the strings the mystic number 2224.”

She supposed this to be the Wedgwoods’ private number, and it was not until she came upon the passage just quoted in Miss Mitford’s Recollections of a Literary Life that the mystery was solved.

[56]

RETURN TO READING

After the extraordinary event of the lottery ticket the Mitfords were suddenly placed in a position of opulence, and they joyfully quitted their dingy London lodgings and returned once more to Reading. The doctor had taken a new red brick house in the London Road, a road which in those days bordered the open country.

The house is still standing, and is probably much as it was in the Mitfords’ day. It has a deep verandah in front, and behind stretches a long piece of garden. A small room at the back of the house is pointed out to visitors as Dr. Mitford’s dispensary.

Mary Russell Mitford loved the old town of Reading—Belford Regis, as she always calls it in her stories—and the various descriptions of the place, scattered throughout her writings, make the Reading of her day to live again.

On one occasion she describes the view of the town as seen from the jutting corner of Friar Street, where she had taken shelter from a[57] shower of rain. She speaks of “the fine church tower of St. Nicholas,[2] with its picturesque piazza underneath” and its “old vicarage house hard by, embowered in evergreens”; of “the old irregular shops in the market-place, with the trees of the Forbury beyond just peeping between them, with all their varieties of light and shadow.”

[2] St. Lawrence.

Another day, after mentioning “the huge monastic ruins of the Abbey;” with all its monuments of ancient times, she goes on to say “or for a modern scene what can surpass the High Bridge on a sunshiny day? The bright river crowded with barges and small craft; the streets and wharfs and quays, all alive with the busy and stirring population of the country and the town—a combination of light and motion.”

Miss Mitford has described this same scene as it appeared on a cold winter’s evening in a book written late in life entitled, Atherton and other Stories, which we should like to quote here.

“From ... the High Bridge the Kennet now showed like a mirror reflecting on its icy surface into a peculiar broad and bluish shine, the arch of lamps surmounting the graceful airy bridge and the twinkling lights that glanced here and there, from boat or barge or wharf, or from[58] some uncurtained window that overhung the river.”

But the chief beauty of the old town was to be seen in summer time on a Saturday (market-day) at noon. “The old market-place, always picturesque from the irregular architecture of the houses, and the beautiful Gothic church by which it is terminated, is then all alive with the busy hum of traffic.... Noise of every sort is to be heard, from the heavy rumbling of so many loaded waggons over the paved market-place to the crash of crockery ware in the narrow passage of Princes Street. One of the noisiest and prettiest places is the Piazza at the end of St. Nicholas Church appropriated by long usage to the female vendors of fruit and vegetables.” The butter market was at the back of the market proper, “where respectable farmers’ wives and daughters sold eggs, butter and poultry.” Here too “straw-hats, caps and ribbons were sold, also pet rabbits and guinea-pigs, together with owls and linnets in cages.”

DR. MITFORD’S HOUSE IN THE LONDON ROAD

Among the odd characters who turned up on the occasion of markets or fairs Miss Mitford mentions a certain rat-catcher by name Sam Page “whose own appearance was as venomous as that of his retinue,” and “told his calling almost as plainly as the sharp heads of the [59]ferrets which protruded from the pockets of his dirty jean jacket, or the bunch of dead rats with which he was wont to parade the streets of B. on a market-day.” But before he had taken to this business, she says, he had tried many other callings, amongst them those of “a barrel-organ grinder, the manager of a celebrated company of dancing dogs, and the leader of a bear and a very accomplished monkey. Suddenly he reappeared one day at B. fair as showman of the Living Skeleton, and also a performer [himself] in the Tragedy of the Edinburgh Murders, as exhibited every half-hour at the price of a penny to each person.” Sam confessed that he liked acting of all things, especially tragedy; “it was such fun.”

Of the period with which we are dealing Mary writes: “I was a girl at the time—a very young girl, and, what is more to the purpose, a very shy one, so that I mixed in none of the gaieties of the place; but speaking from observation and recollection I can fairly say that I never saw any society more innocently cheerful.” She tells us of “the old ladies and their tea visits, the gentlemen and their whist club, and the merry Christmas parties with their round games and their social suppers, their mirth and their jests.”

And now for Mary herself: how did she strike[60] the new acquaintances that her parents were making? One who knew her well tells us that “she showed in her countenance, and in her mild self-possession, that she was no ordinary child; and with her sweet smile, her gentle temper, her animated conversation, her keen enjoyment of life, and her incomparable voice—“that excellent thing in woman—there were few of the prettiest children of her age who won so much love and admiration from their friends young and old as little Mary Mitford.”

In one of Miss Mitford’s tales entitled My Godmothers there is an amusing account of a stiff maiden lady of the old school by name Mrs. Patience Wither (the “Mrs.” being given her by brevet rank). “In point of fact,” writes Mary, “she was not my godmother, having stood only as proxy for her younger sister, Mrs. Mary, my mother’s intimate friend, then falling into a lingering decline.

“Mrs. Patience was very masculine in person, tall, square, large-boned and remarkably upright. Her features were sufficiently regular, and would not have been unpleasing but for the keen, angry look of her light blue eye ... and her fiery, wiry red hair, to which age did no good,—it would not turn grey.... She lived in a large, tall, upright, stately house in the[61] largest street of a large town. It was a grave looking mansion, defended from the pavement by iron palisades, a flight of steps before the sober brown door, and every window curtained and blinded by chintz and silk and muslin, crossing and jostling each other. None of the rooms could be seen from the street, nor the street from any of the rooms—so complete was the obscurity.

“On the death of her sister Mrs. Patience ... was pleased to lay claim to me in right of inheritance, and succeeded to the title of my godmother pretty much in the same way that she succeeded to the possession of Flora, her poor sister’s favourite spaniel. I am afraid that Flora proved the more grateful subject of the two. I never saw Mrs. Patience but she took possession of me for the purpose of lecturing and documenting me on some subject or other,—holding up my head, shutting the door, working a sampler, making a shirt, learning the pence table, or taking physic....

“She was assiduous in presents to me at home and at school; sent me cakes with cautions against over-eating, and needle-cases with admonitions to use them; she made over to me her own juvenile library, consisting of a large collection of unreadable books ... nay, she even rummaged out for me a pair of old[62] battledores, curiously constructed of netted pack-thread—the toys of her youth! But bribery is generally thrown away upon children, especially on spoilt ones; the godmother whom I loved never gave me anything, and every fresh present from Mrs. Patience seemed to me a fresh grievance. I was obliged to make a call and a curtsy, and to stammer out something which passed for a speech, or, which was still worse, to write a letter of thanks—a stiff, formal, precise letter! I would rather have gone without cakes or needle-cases, books or battledores to my dying day. Such was my ingratitude from five to fifteen.”

One of the most prominent figures in the Reading of those days was Dr. Valpy, headmaster of the Reading Grammar School. The school consisted of a group of buildings “standing,” writes Miss Mitford, “in a nook of the pleasant green called the Forbury, and parted from the churchyard of St. Nicholas by a row of tall old houses. It was in itself a pretty object—at least I, who loved it almost as much as if I had been of the sex that learns Greek and Latin, thought so.... There was a little court before the door of the doctor’s house with four fir trees, and at one end a projecting bay window belonging to a very long room [the doctor’s study] lined with a noble collection of[63] books.” The Forbury was used as the boys’ playground.

Dr. Valpy was much reverenced by his fellow-townsmen and greatly loved by his pupils, in spite of the stern discipline of those days which he considered it his duty to administer to culprits. Among his pupils was Sergeant Talfourd, who thus describes his character: “Envy, hatred and malice were to him mere names—like the figures of speech in a schoolboy’s theme, or the giants in a fairy-tale, phantoms which never touched him with a sense of reality.... His system of education was animated by a portion of his own spirit: it was framed to enkindle and to quicken the best affections.”

Another contemporary who happened to be of a cynical turn of mind remarks of Dr. Valpy: “Had he been more supple in his principles or less open in their avowal he might have risen to the highest position in his sacred profession. A mitre might have been the reward of subserviency and the revenues of a diocese the bribe of tergiversation and hypocrisy, [but] he left to others such paths to preferment ... and lived in the enjoyment of an unblemished reputation and a clear conscience.”

On the further side of the Forbury stood a large old-fashioned building adjoining the Abbey Gateway and bearing the name of the Abbey[64] School. It was a school for “young ladies” of the ordinary type belonging to the eighteenth century, but which, at the time we are writing of, was gradually taking a higher position in general estimation. Three authoresses of very different degrees of fame were pupils in this establishment, namely: Jane Austen for a short time as a very young child, in about the year 1782, Miss Butt (afterwards Mrs. Sherwood) in 1790, and Mary Russell Mitford when the school was removed to London in 1798.

The school had formerly been carried on under the management of a Mrs. Latournelle, a good-natured person but, as Mrs. Sherwood tells us, “only fit for giving out clothes for the wash, mending them, making tea and ordering dinners.” But after a time she took as a partner a young lady of talent and of excellent education who at once made her mark felt.

What, however, caused the permanent success of the school was the arrival in Reading of a certain Monsieur St. Quintin, the son of a nobleman in Alsace—a man of very superior intellect—who had been secretary to the Comte de Moustier, one of the last ambassadors from Louis XVI to the Court of St. James. Having lost all his property in the French Revolution, he was thankful to accept the post of French teacher in Dr. Valpy’s school, and was soon[65] afterwards recommended by the doctor as a teacher of French in the Abbey School. In course of time he married Mrs. Latournelle’s young partner, and they “soon so entirely raised the credit of the seminary,” writes Mrs. Sherwood, “that when I went there, there were above sixty girls under their charge. The style of M. St. Quintin’s teaching,” she says, “was lively and interesting in the extreme.”

Dr. Mitford had been a warm friend to M. St. Quintin ever since his arrival in Reading, and there was much pleasant intercourse between the Mitfords and the St. Quintins. In the summer of 1798 the school was transferred to London, and Dr. and Mrs. Mitford, who had then decided to send their little daughter to school, were glad to place her under the friendly care of M. and Madame St. Quintin.

[66]

THE SCHOOL IN HANS PLACE

Monsieur and Madame St. Quintin, on removing the Abbey School from Reading to London, established it in Hans Place, a small oblong square of pleasant-looking houses with a garden in the centre. It was almost surrounded by fields, for London proper terminated in those days with the double toll-gates at Hyde Park Corner.

The school-house (No. 22) was one of the largest in the place, and possessed a spacious garden abounding in fine trees, smooth lawns and gay flower-beds. Thither the little Mary was sent on the reopening of the school after the midsummer holidays of the year 1798. Writing in later years she thus describes the event:—

“It is now more than twenty years since I, a petted child of ten years old, born and bred in the country, and as shy as a hare, was sent to that scene of bustle and confusion, a London school. Oh, what a change it was![67] What a terrible change!... To leave my own dear home for this strange new place and these strange new people ... and so many of them!... I shall never forget the misery of the first two days, blushing to be looked at, dreading to be spoken to, shrinking like a sensitive plant from the touch, ashamed to cry, and feeling as if I could never laugh again.

“These disconsolate feelings are not astonishing ... the wonder is that they so soon passed away. But everybody was good and kind. In less than a week the poor wild bird was tamed. I could look without fear on the bright, happy faces; listen without starting to the clear, high voices, even though they talked in French; began to watch the ball and the battledore; and felt something like an inclination to join in the sports. In short, I soon became an efficient member of the commonwealth; made a friend, provided myself with a school-mother, a fine, tall, blooming girl ... under whose protection I began to learn and unlearn, to acquire the habits and enter into the views of my companions, as well disposed to be idle as the best of them.”

M. St. Quintin taught the pupils French, history and geography, also as much science as he was master of or as he thought it requisite[68] for a young lady to know. Madame St. Quintin did but little teaching at this period, but used to sit in the drawing-room with a book in her hand to receive visitors. After M. St. Quintin the mainstay of the school was the English teacher, Miss Rowden, an accomplished young lady of good birth, who was assisted by finishing masters for Italian, music, dancing and drawing. She was admired and loved by the whole school, and especially by Mary Mitford, over whom she exercised an excellent influence.

“To fill up any nook of time,” writes Mary, “which the common demands of the school might leave vacant, we used to read together, chiefly poetry. With her I first became acquainted with Pope’s Homer, Dryden’s Virgil and the Paradise Lost. She read capitally, and was a most indulgent hearer of my remarks and exclamations;—suffered me to admire Satan and detest Ulysses, and rail at the pious Æneas as long as I chose.”

HANS PLACE

The French teacher was a very different type of womanhood. “She was a tall, majestic woman,” writes Mary, “between sixty and seventy, made taller by yellow slippers with long slender heels.... Her face was almost invisible, being concealed between a mannish kind of neck-cloth and an enormous cap, whose wide, flaunting strip hung over her cheeks and eyes;—to[69] say nothing of a huge pair of spectacles. Madame, all Parisian though she was, had the fidgety neatness of a Dutch woman, and was scandalized at our untidy habits. Four days passed in distant murmurs ... but this was[70] only the gathering of the wind before the storm. It was dancing day; we were all dressed and assembled when Madame, provoked by some indications of latent disorder, instituted, much to our consternation, a general rummage through the house for all things out of their places. The collected mass was thrown together in one stupendous pile in the middle of the schoolroom—a pile that defies description or analysis. The whole was to be apportioned amongst the different owners and then affixed to their persons!... Poor Madame! Article after article was held up to be owned in vain: not a soul would claim such dangerous property. Nevertheless, she did succeed by dint of lucky guesses, [and soon] dictionaries were suspended from the necks of the pupils en médaillon, shawls tied round the waist en ceinture, and unbound music pinned to the frock en queue ... not one of us but had three or four of these appendages; many had five or six. These preparations were intended to meet the eye of Madame’s countryman, the French dancing master, who would doubtless assist in supporting her authority.... She did not know that before his arrival we were to pass an hour in an exercise of another kind, under the command of a drill-sergeant. The man of scarlet was ushered in. It is impossible to say whether the professor of marching[71] or the poor Frenchwoman looked most disconcerted. Madame began a very voluble explanatory harangue; but she was again unfortunate—the sergeant did not understand French. She attempted to translate: ‘It is, Sare, que ces dames, dat dese miss be des traineuses.’ This clear and intelligible sentence producing no other visible effect than a shake of the head, Madame desired the nearest culprit to tell ‘ce soldat là’ what she had said, which caused him of the red coat to declare that ‘it made his blood boil to see so many free-born English girls dominated over by their natural enemy.’ Finally he insisted that we could not march with such incumbrances, which declaration being done into French all at once by half a dozen eager tongues, the trappings were removed and the experiment was ended.”

In spite of this comical exception, the general system of education followed in Hans Place was greatly superior to that of the ordinary boarding schools of the day, where all that could be said of a young lady when her education was finished was that she “played a little, sang a little, talked a little indifferent French, painted shells and roses, not particularly like nature, danced admirably, and was the best player at battledore and shuttle-cock, hunt-the-slipper and blindman’s-buff in her county.”

[72]

Dr. and Mrs. Mitford visited their little daughter frequently during the period of her school life—often taking lodgings in the neighbourhood to be within easy reach. Mrs. Mitford writes on one of these occasions to her husband: “Mezza” (a pet name for Mary), “who has got her little desk here, and her great dictionary, is hard at her studies beside me.... Her little spirits are all abroad to obtain the prize, sometimes hoping, sometimes desponding. It is as well perhaps you are not here at present, as you would be in as great a fidget on the occasion as she herself is.”

Whether Mary won this particular prize we do not know, but that she did win prizes is proved by the fact that two of them are carefully treasured by the descendants of some of her friends. One of these is in our temporary possession. It is a large volume entitled, Adam’s Geography, bound in calf, and ornamented with elegant patterns in gilding. On the upper side of the binding are the words:—

Prix

de

Bonne Conduite

qu’a obtenu

Mlle. Midford

[73]

while on the reverse side we read:—

Mrs. St. Quintin’s

School

Hans Place

June 17th

1801.